Submitted:

08 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

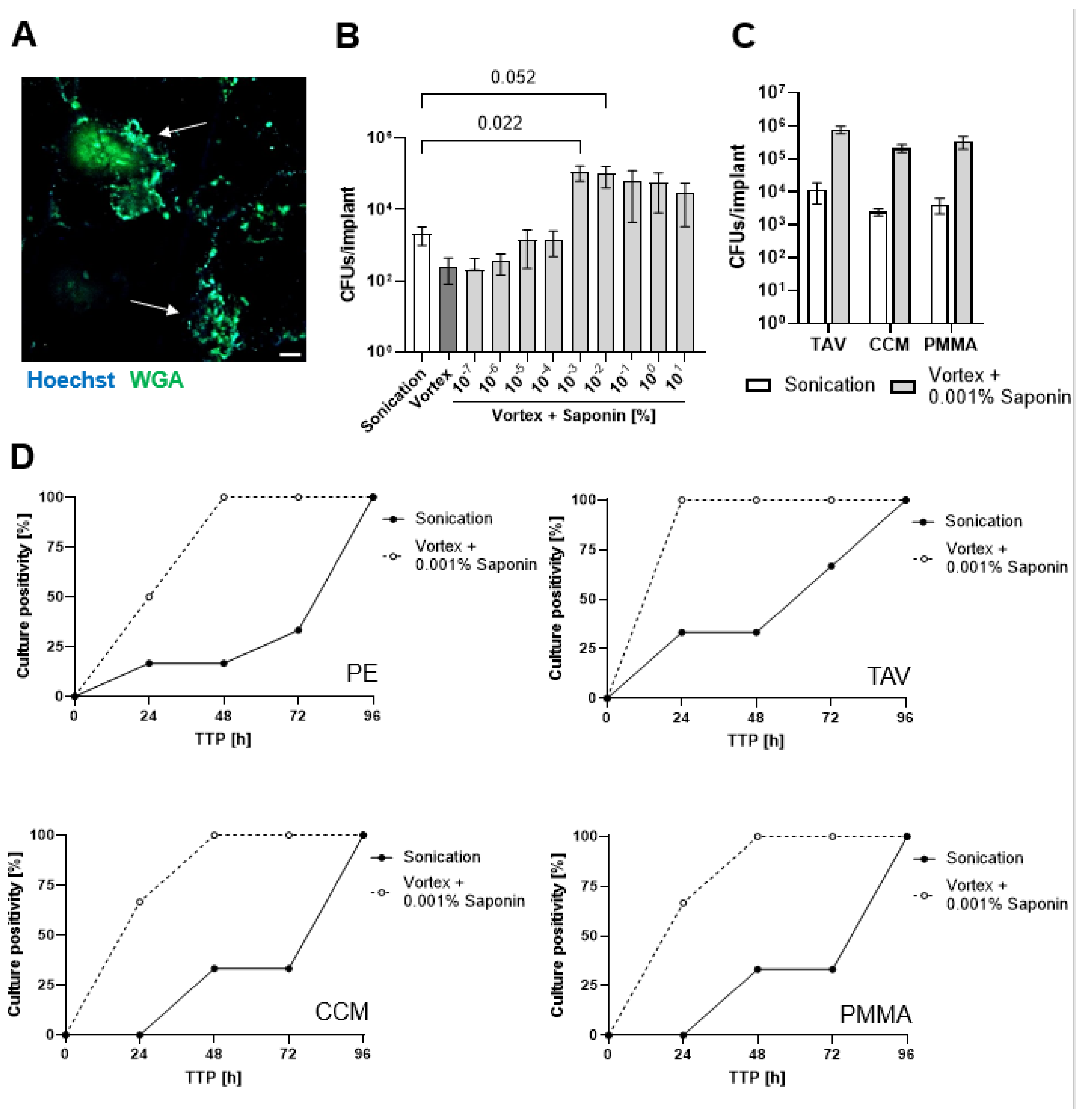

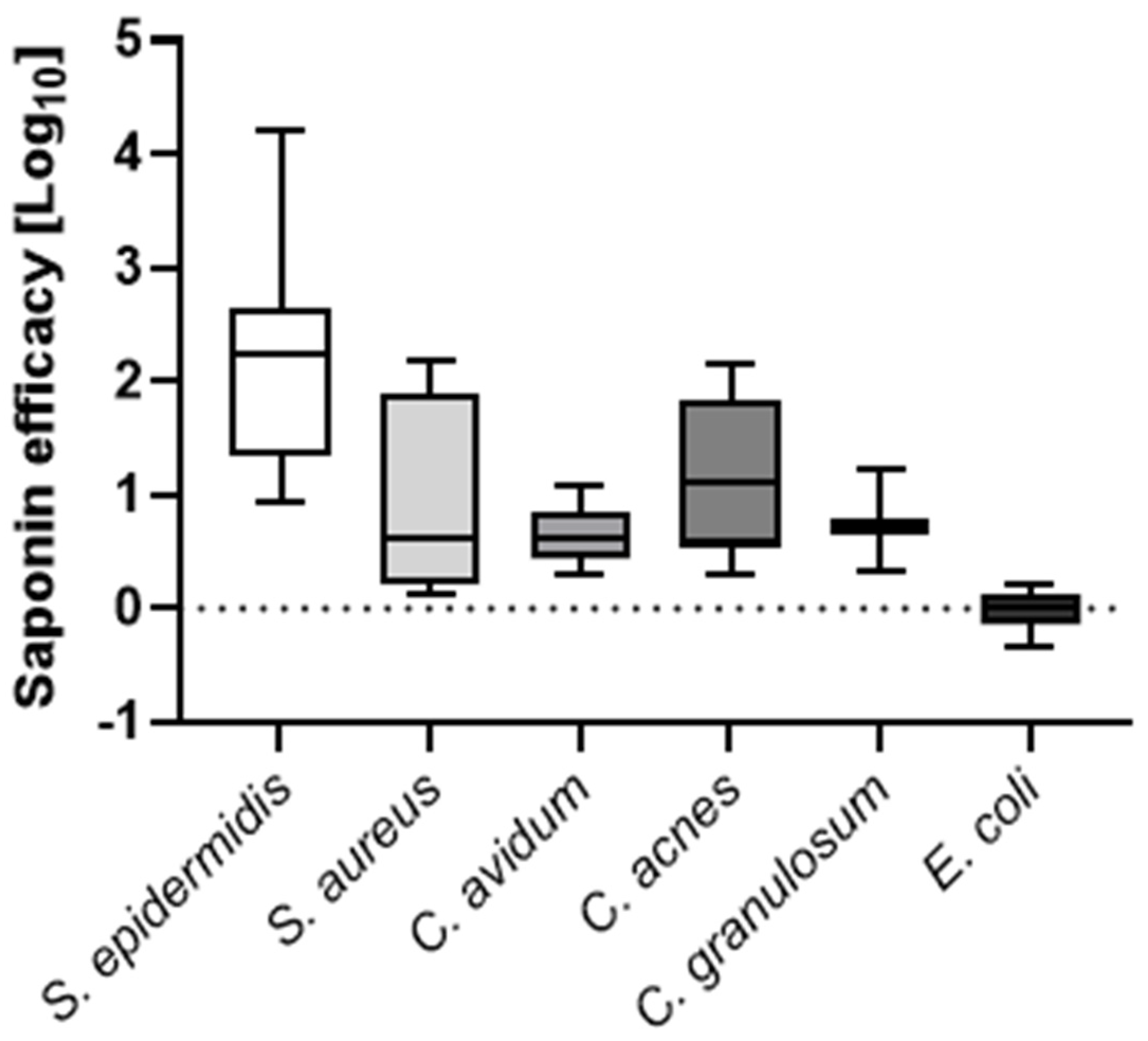

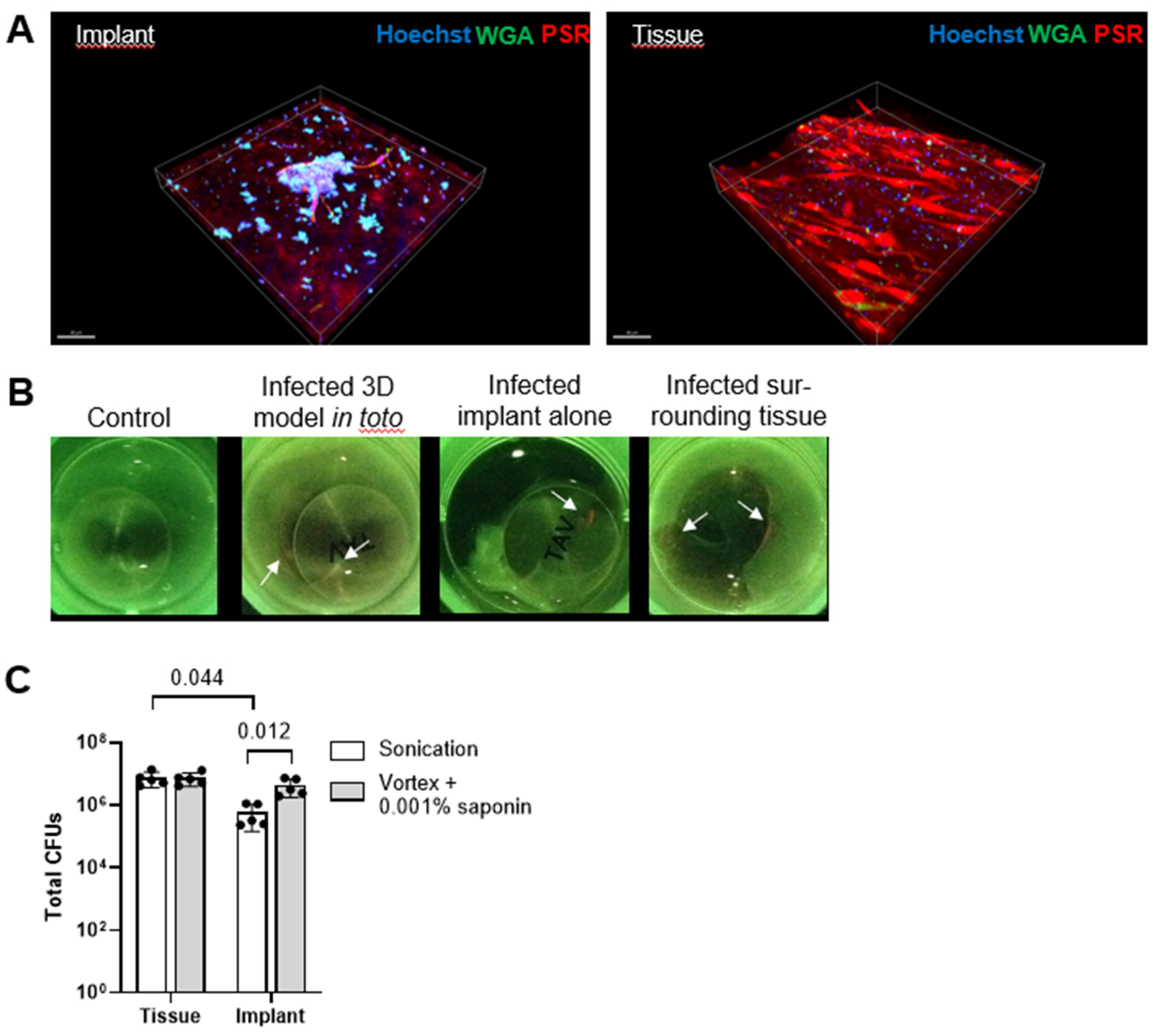

Biofilm formation on orthopedic joint implants complicates treatment and diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections (PJIs). Sonication of explanted orthopedic implants enhances pathogen detection, but it shows limitations in sensitivity and handling. We investigated whether the biosurfactant saponin could improve bacterial recovery from explanted implants. Orthopaedic material discs of 1 cm diameter were contaminated with different clinical bacterial PJI isolates. Biofilms of Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Cutibacterium avidum, Cutibacterium acnes, and Cutibacterium granulosum were grown on the discs, which were then treated with either saline solution or various concentrations of saponin. Next, disks were vortexed or sonicated. prior to vortexing or sonication. Colony forming units (CFUs) enumeration and time-to-positivity of liquid cultures were determined. Additionally, a novel 3D PJI soft-tissue in vitro model was established to validate these findings in a more representative scenario. Median CFU enumeration showed that 0.001% (w/v) saponin as compared to saline solution increased CFUs recovery by 2.2 log10 for S. epidermidis, 0.6 log10 for S. aureus, 0.6 log10 for C. avidum, 1.1 log10 for C. acnes, 0.7 log10 for C. granulosum, and 0.01 log10 for E. coli. Further, saponin treatment resulted in a >1 log10 increase in S. epidermidis CFU recovery from implants in the 3D tissue model compared to standard saline sonication. With that, we propose a novel two-component kit, consisting of a saponin solution and a specialized transportation box, for the efficient collection, transportation, and processing of potentially infected implants. Our data suggests that biosurfactants can enhance bacterial recovery from artificially contaminated orthopedic implants, potentially improving the diagnosis of PJIs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. In Vitro PJI Biofilm

2.3. Biofilm Detachment

2.4. Novel In Vitro 3D PJI Soft Tissue Model

2.5. Infection and Processing of the Novel 3D PJI Soft Tissue Model

2.6. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

2.7. Moleculight i:XTM Imaging

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Finding the Optimum Saponin Concentration for Bacterial Recovery from Biofilms on Implant Discs

3.2. Saponin Effectively Reduces Time-to-Positivity (TTP)

3.3. Saponin Enhances Recovery of the Most Prevalent PJI-Causing Bacteria from Orthopedic Material

3.4. Saponin Enhances Recovery of S. epidermidis from Orthopedic Implant Material in a Novel 3D PJI Soft Tissue Model

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, R. “Periprosthetic joint infection.” N Engl J Med 388 (2023): 251-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36652356. [CrossRef]

- Kusejko, K., A. Aunon, B. Jost, B. Natividad, C. Strahm, C. Thurnheer, D. Pablo-Marcos, D. Slama, G. Scanferla, I. Uckay, et al. “The impact of surgical strategy and rifampin on treatment outcome in cutibacterium periprosthetic joint infections.” Clin Infect Dis 72 (2021): e1064-e73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33300545. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, S. M., L. Kursawe, S. Rahm, J. Prinz, A. S. Zinkernagel, A. Moter, S. P. Kuster, R. Zbinden, P. O. Zingg and Y. Achermann. “Cutibacterium avidum resists surgical skin antisepsis in the groin-a potential risk factor for periprosthetic joint infection: A quality control study.” Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 10 (2021): 27. [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, R. A., A. Adlan, N. Jenkins, M. Parry, J. D. Stevenson and L. Jeys. “A comparison of the microbiology profile for periprosthetic joint infection of knee arthroplasty and lower-limb endoprostheses in tumour surgery.” J Bone Jt Infect 7 (2022): 177-82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36032799. [CrossRef]

- Karachalios, T. and G. A. Komnos. “Management strategies for prosthetic joint infection: Long-term infection control rates, overall survival rates, functional and quality of life outcomes.” EFORT Open Rev 6 (2021): 727-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34667643. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, B. F., G. Muthukrishnan, E. A. Masters, N. Kaplan, J. L. Daiss and E. M. Schwarz. “New developments and future challenges in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of prosthetic joint infection.” J Orthop Res 38 (2020): 1423-35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31965585. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S. Y., K. E. Greenwood-Quaintance, A. D. Hanssen, J. N. Mandrekar and R. Patel. “Low sensitivity of periprosthetic tissue pcr for prosthetic knee infection diagnosis.” Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 79 (2014): 448-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24972853. [CrossRef]

- Talsma, D. T., J. J. W. Ploegmakers, P. C. Jutte, G. Kampinga and M. Wouthuyzen-Bakker. “Time to positivity of acute and chronic periprosthetic joint infection cultures.” Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 99 (2021): 115178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33017799. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q., M. J. Karau, K. E. Greenwood-Quaintance, J. N. Mandrekar, D. R. Osmon, M. P. Abdel and R. Patel. “Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of periprosthetic tissue culture in blood culture bottles to that of prosthesis sonication fluid culture for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection (pji) by use of bayesian latent class modeling and idsa pji criteria for classification.” J Clin Microbiol 56 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29643202. [CrossRef]

- Peel, T. N., T. Spelman, B. L. Dylla, J. G. Hughes, K. E. Greenwood-Quaintance, A. C. Cheng, J. N. Mandrekar and R. Patel. “Optimal periprosthetic tissue specimen number for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection.” J Clin Microbiol 55 (2017): 234-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27807152. [CrossRef]

- Achermann, Y., M. Vogt, M. Leunig, J. Wust and A. Trampuz. “Improved diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection by multiplex pcr of sonication fluid from removed implants.” J Clin Microbiol 48 (2010): 1208-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20164283. NOT IN FILE. [CrossRef]

- Rieger, U. M., G. Pierer, N. J. Luscher and A. Trampuz. “Sonication of removed breast implants for improved detection of subclinical infection.” Aesthetic Plast Surg 33 (2009): 404-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19322605. [CrossRef]

- Trampuz, A., K. E. Piper, A. D. Hanssen, D. R. Osmon, F. R. Cockerill, J. M. Steckelberg and R. Patel. “Sonication of explanted prosthetic components in bags for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection is associated with risk of contamination.” J Clin Microbiol 44 (2006): 628-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16455930. [CrossRef]

- Trampuz, A., K. E. Piper, M. J. Jacobson, A. D. Hanssen, K. K. Unni, D. R. Osmon, J. N. Mandrekar, F. R. Cockerill, J. M. Steckelberg, J. F. Greenleaf and R. Patel. “Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection.” N Engl J Med 357 (2007): 654-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699815. NOT IN FILE. [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, M., L. Barrett, M. Figtree, M. Scarborough, M. Watanabe, R. Newnham, R. Wallis, S. Oakley, B. Kendrick, D. Stubbs, et al. “Sonication versus tissue sampling for diagnosis of prosthetic joint and other orthopedic device-related infections.” J Clin Microbiol 56 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30209185. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T. C., E. K. Honda, D. Daniachi, R. P. L. Cury, C. B. da Silva, G. B. Klautau and M. J. Salles. “The impact of sonication cultures when the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection is inconclusive.” PLoS One 16 (2021): e0252322. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34255768. [CrossRef]

- Drago, L., V. Signori, E. De Vecchi, C. Vassena, E. Palazzi, L. Cappelletti, D. Romano and C. L. Romano. “Use of dithiothreitol to improve the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections.” J Orthop Res 31 (2013): 1694-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23817975. [CrossRef]

- Sandbakken, E. T., E. Hoyer, E. Witso, C. K. Sogaard, A. Diez-Sanchez, L. Hoang, T. S. Wik and K. Bergh. “Biofilm and the effect of sonication in a chronic staphylococcus epidermidis orthopedic in vivo implant infection model.” J Orthop Surg Res 19 (2024): 820. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39633500. [CrossRef]

- Sandbakken, E. T., E. Witso, B. Sporsheim, K. W. Egeberg, O. A. Foss, L. Hoang, G. Bjerkan, K. Loseth and K. Bergh. “Highly variable effect of sonication to dislodge biofilm-embedded staphylococcus epidermidis directly quantified by epifluorescence microscopy: An in vitro model study.” J Orthop Surg Res 15 (2020): 522. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33176843. [CrossRef]

- Drago, L., A. Fidanza, A. Giannetti, A. Ciuffoletti, G. Logroscino and C. L. Romano. “Bacteria living in biofilms in fluids: Could chemical antibiofilm pretreatment of culture represent a paradigm shift in diagnostics?” Microorganisms 12 (2024). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38399663. [CrossRef]

- Kragh, K. N., T. Tolker-Nielsen and M. Lichtenberg. “The non-attached biofilm aggregate.” Commun Biol 6 (2023): 898. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37658117. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Otero, J., M. J. Karau, K. E. Greenwood-Quaintance, M. P. Abdel, J. Mandrekar and R. Patel. “Evaluation of sonicate fluid culture cutoff points for periprosthetic joint infection diagnosis.” Open Forum Infect Dis 11 (2024): ofae159. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38715572. [CrossRef]

- Henriquez, L., C. Martin, M. Echeverz, I. Lasa, C. Ezpeleta and M. E. Portillo. “Evaluation of the use of sonication combined with enzymatic treatment for biofilm removal in the microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection.” Microbiol Spectr 12 (2024): e0002024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38916322. [CrossRef]

- Calori, G. M., M. Colombo, P. Navone, M. Nobile, F. Auxilia, M. Toscano and L. Drago. “Comparative evaluation of microdttect device and flocked swabs in the diagnosis of prosthetic and orthopaedic infections.” Injury 47 Suppl 4 (2016): S17-S21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27492065. [CrossRef]

- Kolenda, C., J. Josse, C. Batailler, A. Faure, A. Monteix, S. Lustig, T. Ferry, F. Laurent and C. Dupieux. “Experience with the use of the microdttect device for the diagnosis of low-grade chronic prosthetic joint infections in a routine setting.” Front Med (Lausanne) 8 (2021): 565555. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33796542. [CrossRef]

- Karbysheva, S., S. Cabric, A. Koliszak, M. Bervar, S. Kirschbaum, S. Hardt, C. Perka and A. Trampuz. “Clinical evaluation of dithiothreitol in comparison with sonication for biofilm dislodgement in the microbiological diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection.” Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 103 (2022): 115679. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35395437. [CrossRef]

- Karbysheva, S., M. Di Luca, M. E. Butini, T. Winkler, M. Schutz and A. Trampuz. “Comparison of sonication with chemical biofilm dislodgement methods using chelating and reducing agents: Implications for the microbiological diagnosis of implant associated infection.” PLoS One 15 (2020): e0231389. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32267888. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Q. Yu, H. Ren, J. Geng, K. Xu, Y. Zhang and L. Ding. “Towards physicochemical and biological effects on detachment and activity recovery of aging biofilm by enzyme and surfactant treatments.” Bioresour Technol 247 (2018): 319-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28950141. [CrossRef]

- Percival, S. L., D. Mayer, R. S. Kirsner, G. Schultz, D. Weir, S. Roy, A. Alavi and M. Romanelli. “Surfactants: Role in biofilm management and cellular behaviour.” Int Wound J 16 (2019): 753-60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30883044. [CrossRef]

- Koley, D. and A. J. Bard. “Triton x-100 concentration effects on membrane permeability of a single hela cell by scanning electrochemical microscopy (secm).” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 (2010): 16783-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20837548. [CrossRef]

- Sutormin, O. S., E. M. Kolosova, I. G. Torgashina, V. A. Kratasyuk, N. S. Kudryasheva, J. S. Kinstler and D. I. Stom. “Toxicity of different types of surfactants via cellular and enzymatic assay systems.” Int J Mol Sci 24 (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36613956. [CrossRef]

- George, A. J. “Legal status and toxicity of saponins.” Food Cosmet Toxicol 3 (1965): 85-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14342799. [CrossRef]

- Savarino, P., M. Demeyer, C. Decroo, E. Colson and P. Gerbaux. “Mass spectrometry analysis of saponins.” Mass Spectrom Rev 42 (2023): 954-83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34431118. [CrossRef]

- Prinz, J., M. Wink, S. Neuhaus, M. C. Grob, H. Walt, P. P. Bosshard and Y. Achermann. “Effective biofilm eradication on orthopedic implants with methylene blue based antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in vitro.” Antibiotics (Basel) 12 (2023). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36671319. [CrossRef]

- Wegner, K. A., A. Keikhosravi, K. W. Eliceiri and C. M. Vezina. “Fluorescence of picrosirius red multiplexed with immunohistochemistry for the quantitative assessment of collagen in tissue sections.” J Histochem Cytochem 65 (2017): 479-90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28692327. [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. M., D. Dunham, M. Y. Rennie, J. Kirman, A. J. Lopez, K. C. Keim, W. Little, A. Gomez, J. Bourke, H. Ng, et al. “In vitro detection of porphyrin-producing wound bacteria with real-time fluorescence imaging.” Future Microbiol 15 (2020): 319-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32101035. [CrossRef]

- Redmond, S., C. J. Lewis, S. Rowe, E. Raby and S. Rea. “The use of moleculight for early detection of colonisation in dermal templates.” Burns 45 (2019): 1940-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31672470. [CrossRef]

- Raizman, R., D. Dunham, L. Lindvere-Teene, L. M. Jones, K. Tapang, R. Linden and M. Y. Rennie. “Use of a bacterial fluorescence imaging device: Wound measurement, bacterial detection and targeted debridement.” J Wound Care 28 (2019): 824-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31825778. [CrossRef]

- Shabana, N. S., G. Seeber, A. Soriano, P. C. Jutte, S. Westermann, G. Mithoe, L. Pirii, T. Siebers, B. T. Have, W. Zijlstra, et al. “The clinical outcome of early periprosthetic joint infections caused by staphylococcus epidermidis and managed by surgical debridement in an era of increasing resistance.” Antibiotics (Basel) 12 (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36671241. [CrossRef]

- Widerstrom, M., M. Stegger, A. Johansson, B. K. Gurram, A. R. Larsen, L. Wallinder, H. Edebro and T. Monsen. “Heterogeneity of staphylococcus epidermidis in prosthetic joint infections: Time to reevaluate microbiological criteria?” Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 41 (2022): 87-97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34599708. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Rodriguez, D., C. A. Colin-Castro, M. Hernandez-Duran, L. E. Lopez-Jacome and R. Franco-Cendejas. “Staphylococcus epidermidis small colony variants, clinically significant quiescent threats for patients with prosthetic joint infection.” Microbes Infect 23 (2021): 104854. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34214690. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Z. K., K. S. McQuivey, D. G. Deckey, J. Haglin, M. J. Spangehl and J. S. Bingham. “Acute or chronic periprosthetic joint infection? Using the esr ∕ crp ratio to aid in determining the acuity of periprosthetic joint infections.” J Bone Jt Infect 6 (2021): 229-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34159047. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, Y., E. Roschke, N. Dietze, A. J. Dahse, I. F. Chaberny, D. Ranft, C. Pempe, S. Goralski, M. Ghanem, R. Kluge, et al. “Early-outcome differences between acute and chronic periprosthetic joint infections-a retrospective single-center study.” Antibiotics (Basel) 13 (2024). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38534633. [CrossRef]

- Esteban, J., E. Gomez-Barrena, J. Cordero, N. Z. Martin-de-Hijas, T. J. Kinnari and R. Fernandez-Roblas. “Evaluation of quantitative analysis of cultures from sonicated retrieved orthopedic implants in diagnosis of orthopedic infection.” J Clin Microbiol 46 (2008): 488-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18077647. [CrossRef]

- Tunney, M. M., S. Patrick, S. P. Gorman, J. R. Nixon, N. Anderson, R. I. Davis, D. Hanna and G. Ramage. “Improved detection of infection in hip replacements. A currently underestimated problem.” J Bone Joint Surg Br 80 (1998): 568-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9699813. NOT IN FILE.

- Beloin, C., A. Roux and J. M. Ghigo. “Escherichia coli biofilms.” Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 322 (2008): 249-89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18453280. [CrossRef]

- McCrate, O. A., X. Zhou, C. Reichhardt and L. Cegelski. “Sum of the parts: Composition and architecture of the bacterial extracellular matrix.” J Mol Biol 425 (2013): 4286-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23827139. [CrossRef]

- de Buys, M., K. Moodley, J. N. Cakic and J. R. T. Pietrzak. “Staphylococcus aureus colonization and periprosthetic joint infection in patients undergoing elective total joint arthroplasty: A narrative review.” EFORT Open Rev 8 (2023): 680-89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37655845. [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Gallego, I., M. A. Melendez-Carmona, J. Lora-Tamayo, C. Garrido-Allepuz, F. Chaves, V. Sebastian and E. Viedma. “Microbiological and molecular features associated with persistent and relapsing staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection.” Antibiotics (Basel) 11 (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36009988. [CrossRef]

- Boisrenoult, P. “Cutibacterium acnes prosthetic joint infection: Diagnosis and treatment.” Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 104 (2018): S19-S24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29203432. [CrossRef]

- Prinz, J., B. Schmid, R. Zbinden, P. O. Zingg, I. Uckay, Y. Achermann and P. P. Bosshard. “Fast and sensitive multiplex real-time quantitative pcr to detect cutibacterium periprosthetic joint infections.” J Mol Diagn 24 (2022): 666-73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35364323. [CrossRef]

- Silva, N. D. S., B. S. T. De Melo, A. Oliva and P. S. R. de Araujo. “Sonication protocols and their contributions to the microbiological diagnosis of implant-associated infections: A review of the current scenario.” Front Cell Infect Microbiol 14 (2024): 1398461. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38803573. [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, A., D. A. Kolin, K. X. Farley, J. M. Wilson, A. S. McLawhorn, M. B. Cross and P. K. Sculco. “Projected economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection of the hip and knee in the united states.” J Arthroplasty 36 (2021): 1484-89 e3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33422392. [CrossRef]

- Szymski, D., N. Walter, K. Hierl, M. Rupp and V. Alt. “Direct hospital costs per case of periprosthetic hip and knee joint infections in europe - a systematic review.” J Arthroplasty 39 (2024): 1876-81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38266688. [CrossRef]

- Bori, G., E. Munoz-Mahamud, S. Garcia, C. Mallofre, X. Gallart, J. Bosch, E. Garcia, J. Riba, J. Mensa and A. Soriano. “Interface membrane is the best sample for histological study to diagnose prosthetic joint infection.” Mod Pathol 24 (2011): 579-84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21131917. [CrossRef]

- Muller, M., L. Morawietz, O. Hasart, P. Strube, C. Perka and S. Tohtz. “[histopathological diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection following total hip arthroplasty : Use of a standardized classification system of the periprosthetic interface membrane].” Orthopade 38 (2009): 1087-96. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19690832. Histopathologische Diagnose der periprothetischen Gelenkinfektion nach Huftgelenkersatz : Verwendung eines standardisierten Klassifikationssystems der periprothetischen Interface-Membranen. [CrossRef]

- Stoodley, P., L. Nistico, S. Johnson, L. A. Lasko, M. Baratz, V. Gahlot, G. D. Ehrlich and S. Kathju. “Direct demonstration of viable staphylococcus aureus biofilms in an infected total joint arthroplasty. A case report.” J Bone Joint Surg Am 90 (2008): 1751-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18676908. [CrossRef]

- de Breij, A., M. Riool, P. H. Kwakman, L. de Boer, R. A. Cordfunke, J. W. Drijfhout, O. Cohen, N. Emanuel, S. A. Zaat, P. H. Nibbering and T. F. Moriarty. “Prevention of staphylococcus aureus biomaterial-associated infections using a polymer-lipid coating containing the antimicrobial peptide op-145.” J Control Release 222 (2016): 1-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26658071. [CrossRef]

- Perez, K. and R. Patel. “Survival of staphylococcus epidermidis in fibroblasts and osteoblasts.” Infect Immun 86 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30061380. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J. R., D. J. Chonko, M. Pigott, A. C. Sullivan, K. Moore and P. Stoodley. “Mapping bacterial biofilm on explanted orthopedic hardware: An analysis of 14 consecutive cases.” APMIS 131 (2023): 170-79. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36656746. [CrossRef]

- Moley, J. P., M. S. McGrath, J. F. Granger, A. C. Sullivan, P. Stoodley and D. H. Dusane. “Mapping bacterial biofilms on recovered orthopaedic implants by a novel agar candle dip method.” APMIS 127 (2019): 123-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30687941. [CrossRef]

- Moore, K., N. Gupta, T. T. Gupta, K. Patel, J. R. Brooks, A. Sullivan, A. S. Litsky and P. Stoodley. “Mapping bacterial biofilm on features of orthopedic implants in vitro.” Microorganisms 10 (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35336161. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).