Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

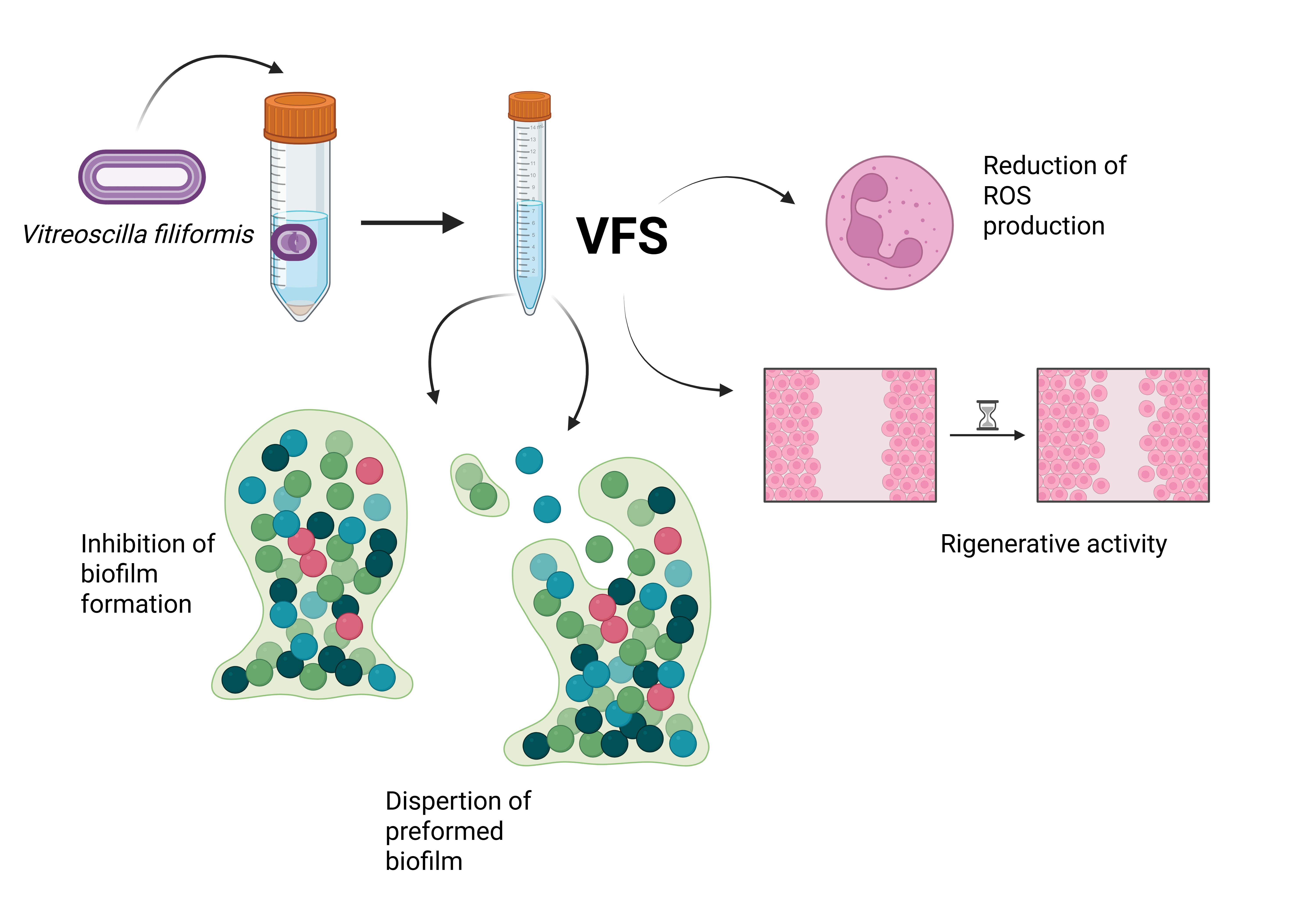

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Vitreoscilla filiformis and Culture Supernatant Preparation

2.3. Microbial Growth Kinetics

2.4. Effect of V. filiformis Supernatant (VFS) on S. aureus, S. epidermidis and MRSA Biofilm Formation and Dispersal

2.5. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6. Polymorphonuclear Cells (PMN) Isolation

2.7. Evaluation of ROS Production by Luminol Assay

2.8. Effect of Vitreoscilla filiformis Supernatant on the Regenerative Capacity of Human Dermal Fibroblasts

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

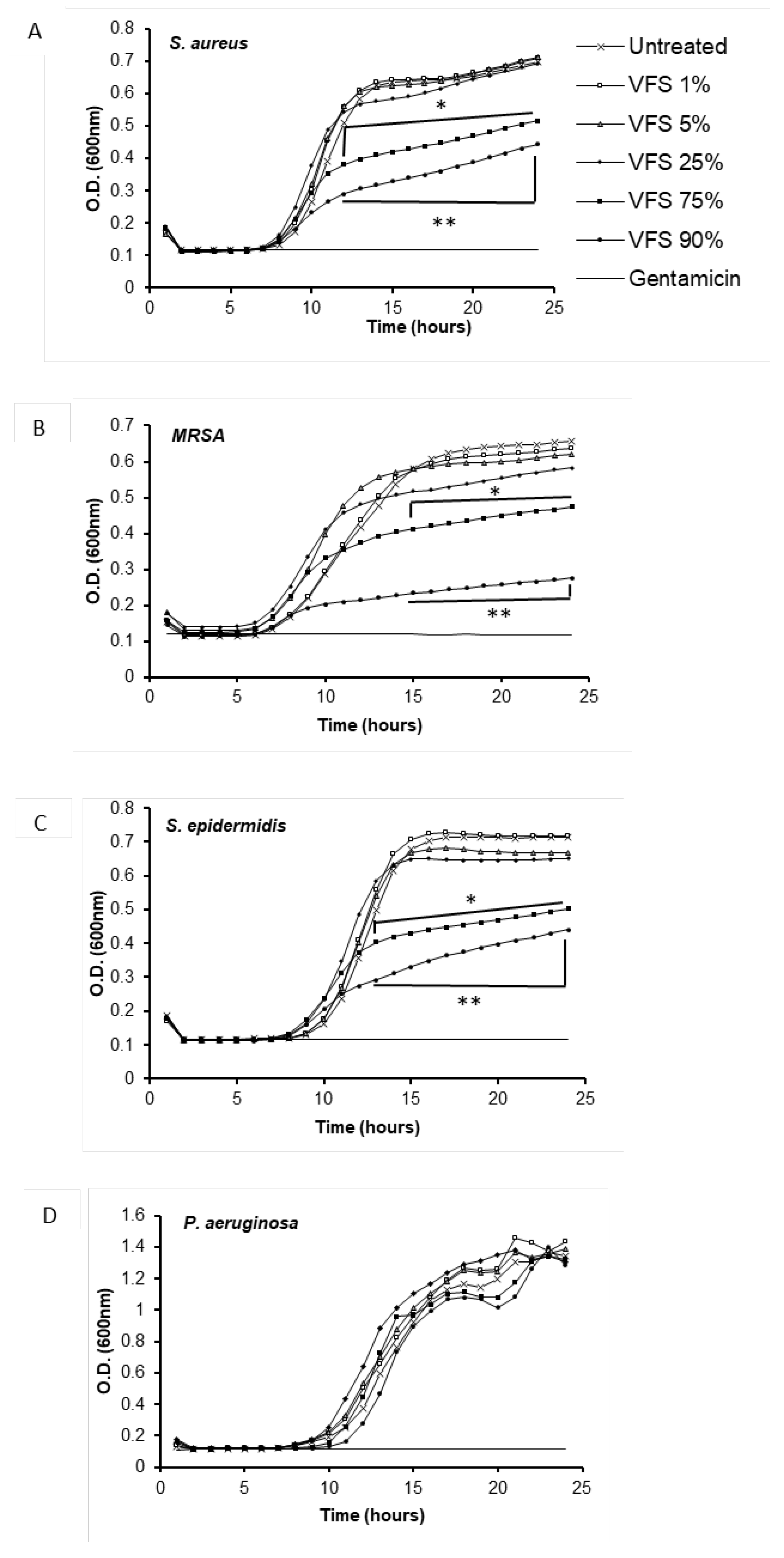

3.1. V. filiformis Supernatant Effect on Growth Kinetics of Bacteria

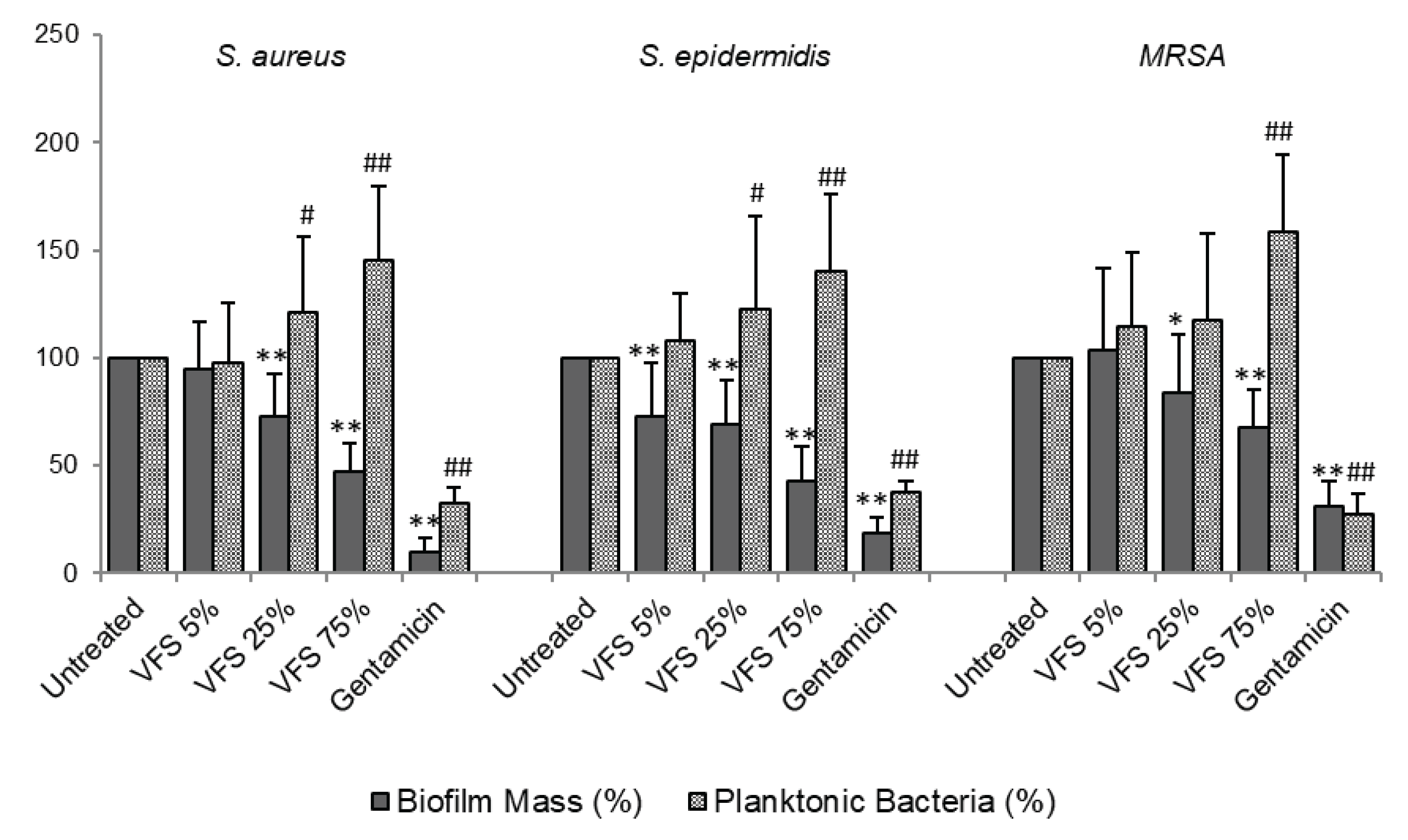

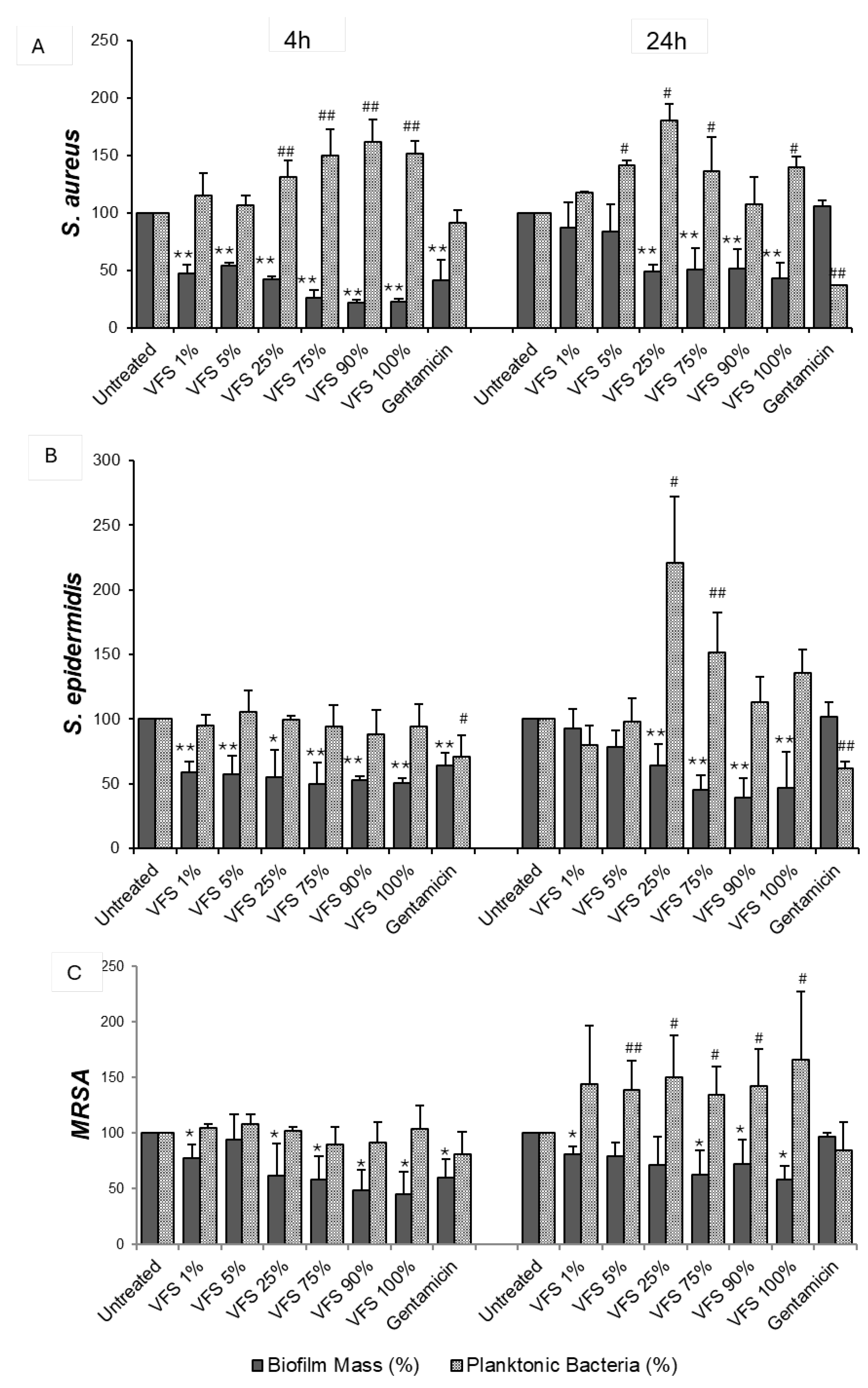

3.2. Effect of V. filiformis Supernatant on Biofilm Formation and Dispersal

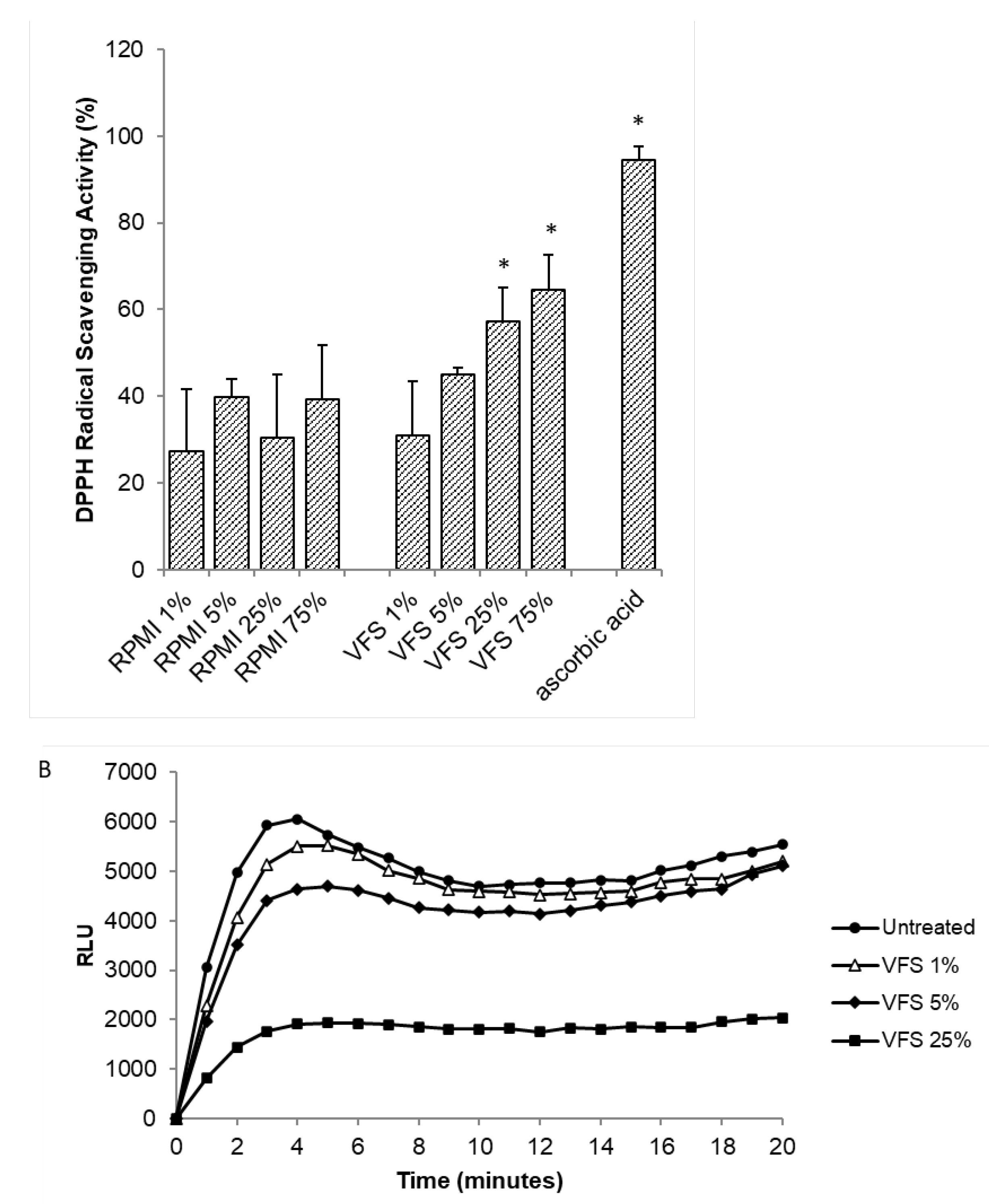

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

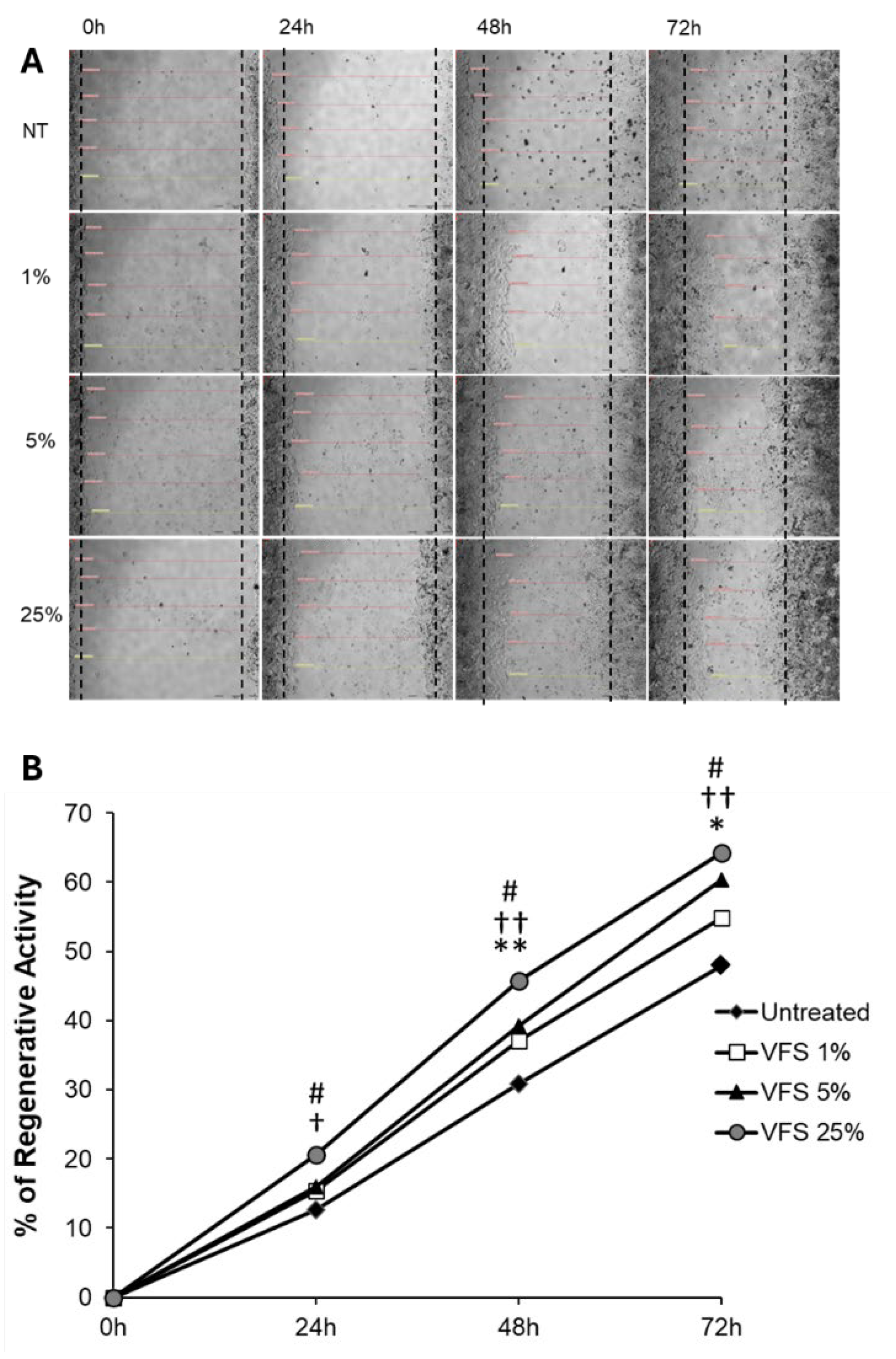

3.4. Regenerative Activity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VFS | V. filiformis supernatant |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| AD | Atopic Dermatitis |

References

- Skowron, K.; Bauza-Kaszewska, J.; Kraszewska, Z.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Kwiecińska-Piróg, J.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Radtke, L.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Human Skin Microbiome: Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors on Skin Microbiota. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 543. [CrossRef]

- Cundell, A.M. Microbial Ecology of the Human Skin. Microb Ecol 2018, 76, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Buffie, C.G.; Pamer, E.G. Microbiota-Mediated Colonization Resistance against Intestinal Pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 790–801. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, L.; Grice, E.A. The Skin Microbiota: Balancing Risk and Reward. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 190–200. [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.H.; Oh, J.; Deming, C.; Conlan, S.; Grice, E.A.; Beatson, M.A.; Nomicos, E.; Polley, E.C.; Komarow, H.D.; NISC Comparative Sequence Program; et al. Temporal Shifts in the Skin Microbiome Associated with Disease Flares and Treatment in Children with Atopic Dermatitis. Genome Res 2012, 22, 850–859. [CrossRef]

- Miajlovic, H.; Fallon, P.G.; Irvine, A.D.; Foster, T.J. Effect of Filaggrin Breakdown Products on Growth of and Protein Expression by Staphylococcus Aureus. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010, 126, 1184-1190.e3. [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.L.; Deming, C.; Cassidy, S.K.B.; Harrison, O.J.; Ng, W.-I.; Conlan, S.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A.; Kong, H.H. Staphylococcus Aureus and Staphylococcus Epidermidis Strain Diversity Underlying Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9, eaal4651. [CrossRef]

- Saheb Kashaf, S.; Harkins, C.P.; Deming, C.; Joglekar, P.; Conlan, S.; Holmes, C.J.; Almeida, A.; Finn, R.D.; Segre, J.A.; Kong, H.H. Staphylococcal Diversity in Atopic Dermatitis from an Individual to a Global Scale. Cell Host & Microbe 2023, 31, 578-592.e6. [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, E.G.; Cavallo, I.; Bordignon, V.; Prignano, G.; Sperduti, I.; Gurtner, A.; Trento, E.; Toma, L.; Pimpinelli, F.; Capitanio, B.; et al. Inflammatory Cytokines and Biofilm Production Sustain Staphylococcus Aureus Outgrowth and Persistence: A Pivotal Interplay in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 9573. [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M.; Agnew, K.; Anagnostou, N.; Andrews, M.; Armour, K.; Baker, C.; Foley, P.; Gebauer, K.; Gupta, M.; Marshman, G.; et al. Psoriasis and Infection. A Clinical Practice Narrative. Australas J Dermatol 2019, 60, 91–98. [CrossRef]

- Alekseyenko, A.V.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; De Souza, A.; Strober, B.; Gao, Z.; Bihan, M.; Li, K.; Methé, B.A.; Blaser, M.J. Community Differentiation of the Cutaneous Microbiota in Psoriasis. Microbiome 2013, 1, 31. [CrossRef]

- Weyrich, L.S.; Dixit, S.; Farrer, A.G.; Cooper, A.J.; Cooper, A.J. The Skin Microbiome: Associations between Altered Microbial Communities and Disease. Australas J Dermatol 2015, 56, 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-W.; Yan, D.; Singh, R.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Ucmak, D.; Lee, K.; Afifi, L.; Fadrosh, D.; Leech, J.; et al. Alteration of the Cutaneous Microbiome in Psoriasis and Potential Role in Th17 Polarization. Microbiome 2018, 6, 154. [CrossRef]

- Sorg, H.; Tilkorn, D.J.; Hager, S.; Hauser, J.; Mirastschijski, U. Skin Wound Healing: An Update on the Current Knowledge and Concepts. Eur Surg Res 2017, 58, 81–94. [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, S.; Nunes, J.V.; Grobusch, M.P.; Sesay, M.; Kriegel, M.A.; Varghese, J.; Schaumburg, F. Network Analysis of Polymicrobial Chronic Wound Infections in Masanga, Sierra Leone. BMC Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, 250. [CrossRef]

- Yung, D.B.Y.; Sircombe, K.J.; Pletzer, D. Friends or Enemies? The Complicated Relationship between Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Staphylococcus Aureus. Mol Microbiol 2021, 116, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pastar, I.; Nusbaum, A.G.; Gil, J.; Patel, S.B.; Chen, J.; Valdes, J.; Stojadinovic, O.; Plano, L.R.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Davis, S.C. Interactions of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus USA300 and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Polymicrobial Wound Infection. PLoS One 2013, 8, e56846. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Dielubanza, E.; Maisel, A.; Leung, K.; Mustoe, T.; Hong, S.; Galiano, R. Staphylococcus Aureus Impairs Cutaneous Wound Healing by Activating the Expression of a Gap Junction Protein, Connexin-43 in Keratinocytes. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021, 78, 935–947. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-K.; Cheng, N.-C.; Cheng, C.-M. Biofilms in Chronic Wounds: Pathogenesis and Diagnosis. Trends Biotechnol 2019, 37, 505–517. [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Ceilley, R. Chronic Wound Healing: A Review of Current Management and Treatments. Adv Ther 2017, 34, 599–610. [CrossRef]

- James, G.A.; Swogger, E.; Wolcott, R.; Pulcini, E. deLancey; Secor, P.; Sestrich, J.; Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S. Biofilms in Chronic Wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2008, 16, 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Malone, M.; Bjarnsholt, T.; McBain, A.J.; James, G.A.; Stoodley, P.; Leaper, D.; Tachi, M.; Schultz, G.; Swanson, T.; Wolcott, R.D. The Prevalence of Biofilms in Chronic Wounds: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published Data. J Wound Care 2017, 26, 20–25. [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, D.G.; Bowler, P.G. Biofilm Delays Wound Healing: A Review of the Evidence. Burns Trauma 2015, 1, 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, J. Dynamic Interactions of Neutrophils and Biofilms. J Oral Microbiol 2014, 6, 10.3402/jom.v6.26102. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, T.; Musse, F.; Magnusson, K.-E.; Vikström, E. N-Acylhomoserine Lactones Are Potent Neutrophil Chemoattractants That Act via Calcium Mobilization and Actin Remodeling. J Leukoc Biol 2012, 91, 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Wolcott, R.D.; Rhoads, D.D.; Dowd, S.E. Biofilms and Chronic Wound Inflammation. J Wound Care 2008, 17, 333–341. [CrossRef]

- Prince, L.R.; Bianchi, S.M.; Vaughan, K.M.; Bewley, M.A.; Marriott, H.M.; Walmsley, S.R.; Taylor, G.W.; Buttle, D.J.; Sabroe, I.; Dockrell, D.H.; et al. Subversion of a Lysosomal Pathway Regulating Neutrophil Apoptosis by a Major Bacterial Toxin, Pyocyanin. J Immunol 2008, 180, 3502–3511. [CrossRef]

- Rohde, H.; Burdelski, C.; Bartscht, K.; Hussain, M.; Buck, F.; Horstkotte, M.A.; Knobloch, J.K.-M.; Heilmann, C.; Herrmann, M.; Mack, D. Induction of Staphylococcus Epidermidis Biofilm Formation via Proteolytic Processing of the Accumulation-Associated Protein by Staphylococcal and Host Proteases. Molecular Microbiology 2005, 55, 1883–1895. [CrossRef]

- Méric, G.; Mageiros, L.; Pensar, J.; Laabei, M.; Yahara, K.; Pascoe, B.; Kittiwan, N.; Tadee, P.; Post, V.; Lamble, S.; et al. Disease-Associated Genotypes of the Commensal Skin Bacterium Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5034. [CrossRef]

- Uçkay, I.; Pittet, D.; Vaudaux, P.; Sax, H.; Lew, D.; Waldvogel, F. Foreign Body Infections Due to Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Ann Med 2009, 41, 109–119. [CrossRef]

- Saltoglu, N.; Ergonul, O.; Tulek, N.; Yemisen, M.; Kadanali, A.; Karagoz, G.; Batirel, A.; Ak, O.; Sonmezer, C.; Eraksoy, H.; et al. Influence of Multidrug Resistant Organisms on the Outcome of Diabetic Foot Infection. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018, 70, 10–14. [CrossRef]

- Giurato, L.; Meloni, M.; Izzo, V.; Uccioli, L. Osteomyelitis in Diabetic Foot: A Comprehensive Overview. World J Diabetes 2017, 8, 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Ortines, R.V.; Liu, H.; Cheng, L.I.; Cohen, T.S.; Lawlor, H.; Gami, A.; Wang, Y.; Dillen, C.A.; Archer, N.K.; Miller, R.J.; et al. Neutralizing Alpha-Toxin Accelerates Healing of Staphylococcus Aureus-Infected Wounds in Nondiabetic and Diabetic Mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e02288-17. [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadou, I.; Tentolouris, N.; Argiana, V.; Jude, E.; Boulton, A.J. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Diabetic Foot Infections. Drugs 2010, 70, 1785–1797. [CrossRef]

- Tsige, Y.; Tadesse, S.; G/Eyesus, T.; Tefera, M.M.; Amsalu, A.; Menberu, M.A.; Gelaw, B. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Associated Risk Factors among Patients with Wound Infection at Referral Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. J Pathog 2020, 2020, 3168325. [CrossRef]

- Gueniche, A.; Knaudt, B.; Schuck, E.; Volz, T.; Bastien, P.; Martin, R.; Röcken, M.; Breton, L.; Biedermann, T. Effects of Nonpathogenic Gram-Negative Bacterium Vitreoscilla Filiformis Lysate on Atopic Dermatitis: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study. Br J Dermatol 2008, 159, 1357–1363. [CrossRef]

- Seité, S.; Zelenkova, H.; Martin, R. Clinical Efficacy of Emollients in Atopic Dermatitis Patients – Relationship with the Skin Microbiota Modification. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2017, 10, 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Mahe, Y.F.; Perez, M.-J.; Tacheau, C.; Fanchon, C.; Martin, R.; Rousset, F.; Seite, S. A New Vitreoscilla Filiformis Extract Grown on Spa Water-Enriched Medium Activates Endogenous Cutaneous Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Defenses through a Potential Toll-like Receptor 2/Protein Kinase C, Zeta Transduction Pathway. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2013, 6, 191–196. [CrossRef]

- Mahé, Y.F.; Martin, R.; Aubert, L.; Billoni, N.; Collin, C.; Pruche, F.; Bastien, P.; Drost, S.S.; Lane, A.T.; Meybeck, A. Induction of the Skin Endogenous Protective Mitochondrial MnSOD by Vitreoscilla Filiformis Extract. International Journal of Cosmetic Science 2006, 28, 277–287. [CrossRef]

- Volz, T.; Skabytska, Y.; Guenova, E.; Chen, K.-M.; Frick, J.-S.; Kirschning, C.J.; Kaesler, S.; Röcken, M.; Biedermann, T. Nonpathogenic Bacteria Alleviating Atopic Dermatitis Inflammation Induce IL-10-Producing Dendritic Cells and Regulatory Tr1 Cells. J Invest Dermatol 2014, 134, 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Iwase, T.; Uehara, Y.; Shinji, H.; Tajima, A.; Seo, H.; Takada, K.; Agata, T.; Mizunoe, Y. Staphylococcus Epidermidis Esp Inhibits Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilm Formation and Nasal Colonization. Nature 2010, 465, 346–349. [CrossRef]

- Dutra, R.P.; Abreu, B.V. de B.; Cunha, M.S.; Batista, M.C.A.; Torres, L.M.B.; Nascimento, F.R.F.; Ribeiro, M.N.S.; Guerra, R.N.M. Phenolic Acids, Hydrolyzable Tannins, and Antioxidant Activity of Geopropolis from the Stingless Bee Melipona Fasciculata Smith. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 2549–2557. [CrossRef]

- Branski, L.K.; Al-Mousawi, A.; Rivero, H.; Jeschke, M.G.; Sanford, A.P.; Herndon, D.N. Emerging Infections in Burns. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009, 10, 389–397. [CrossRef]

- Dunnill, C.; Patton, T.; Brennan, J.; Barrett, J.; Dryden, M.; Cooke, J.; Leaper, D.; Georgopoulos, N.T. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Wound Healing: The Functional Role of ROS and Emerging ROS-Modulating Technologies for Augmentation of the Healing Process. Int Wound J 2017, 14, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Zielins, E.R.; Brett, E.A.; Luan, A.; Hu, M.S.; Walmsley, G.G.; Paik, K.; Senarath-Yapa, K.; Atashroo, D.A.; Wearda, T.; Lorenz, H.P.; et al. Emerging Drugs for the Treatment of Wound Healing. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2015, 20, 235–246. [CrossRef]

- Gueniche, A.; Liboutet, M.; Cheilian, S.; Fagot, D.; Juchaux, F.; Breton, L. Vitreoscilla Filiformis Extract for Topical Skin Care: A Review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 747663. [CrossRef]

- Gueniche, A.; Valois, A.; Kerob, D.; Rasmont, V.; Nielsen, M. A Combination of Vitreoscilla Filiformis Extract and Vichy Volcanic Mineralizing Water Strengthens the Skin Defenses and Skin Barrier. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022, 36 Suppl 2, 16–25. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).