Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

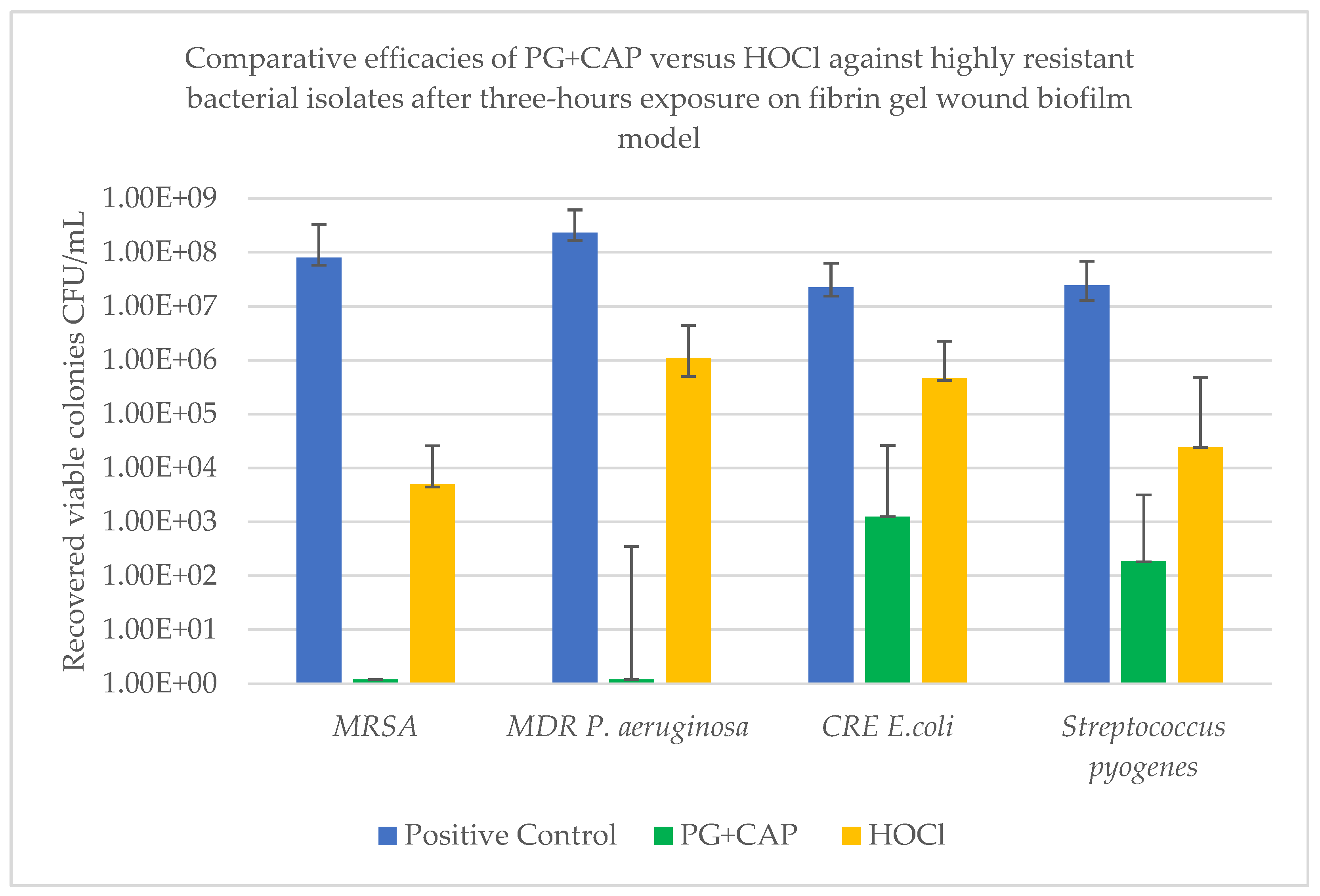

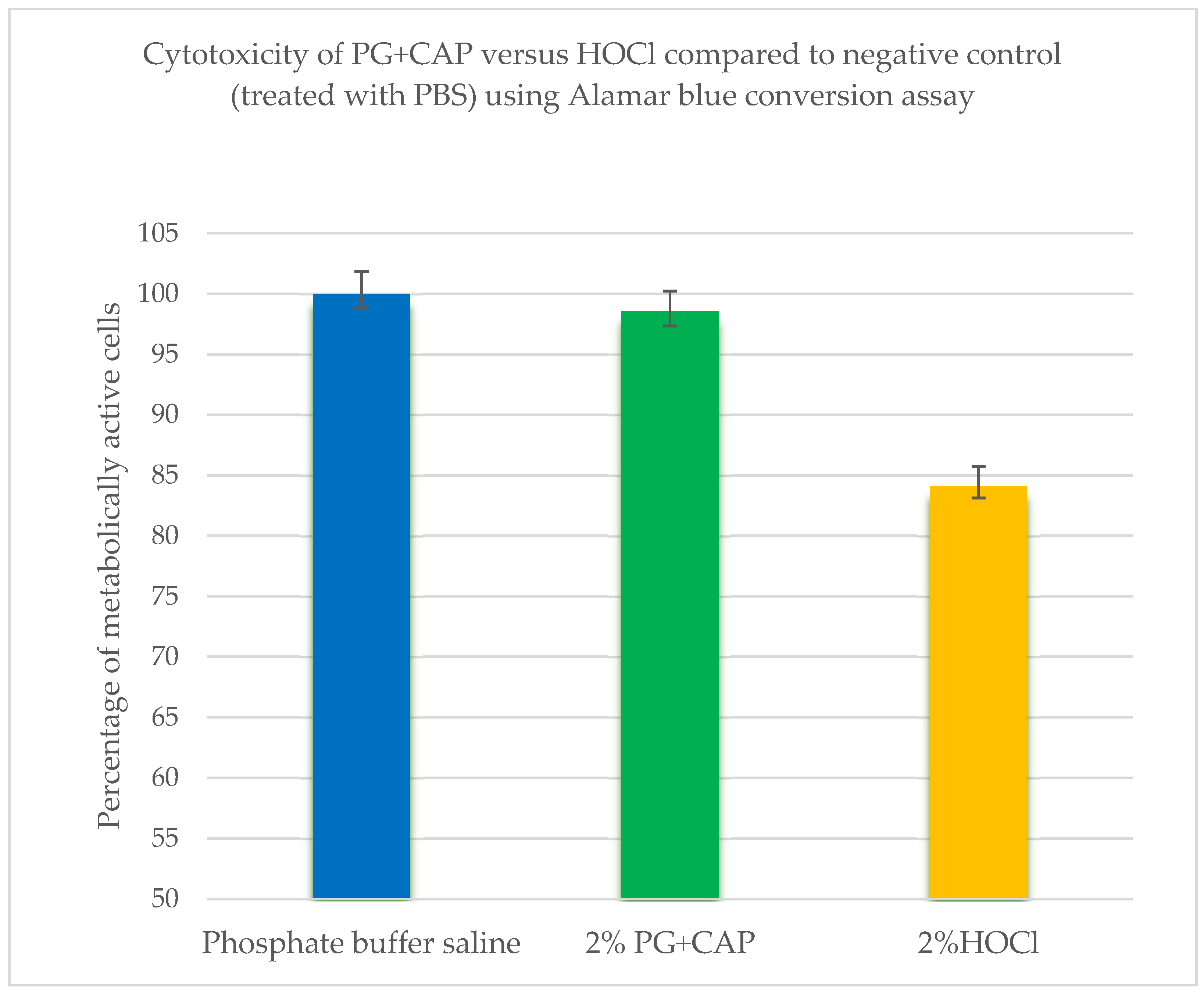

Introduction: Natural, plant-based agents are alternatives to antibiotics and antiseptics in treating bacterially colonized wounds and potentially offer an antimicrobial activity without cytotoxicity. In this study, we used a three-dimensional fibrin-gel wound biofilm (FGWB) model to be more representative of the wound biofilm environment. We compared a common antiseptic wound care agent, hypochlorous acid (HOCl), with a combination of two plant-based agents; polygalacturonic acid (PG) and caprylic acid (CAP) for bacterial biofilm eradication and assessed their cytotoxicities towards fibroblast cells. Material and Methods: The efficacy PG+CAP ointment was compared to HOCl irrigant solution in biofilm eradication using the FGWB against clinical resistant bacterial isolates of MRSA, MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, CRE Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus pyogenes. Trypan blue exclusion and Alamar blue conversion assays were used for cytotoxicity assays. Results: PG+CAP produced a significantly greater reduction of viable organisms than HOCl for all tested bacterial isolates in the FGWB model (P≤ 0.05). Also, cytotoxicity tests showed that, PG+CAP was comparable to the non-antimicrobial negative control and was less cytotoxic than HOCl (P≤0.05). Conclusion: PG+CAP was highly effective against biofilms of highly resistant bacterial isolates in the FGWB model, and less cytotoxic than HOCl. PG+CAP merits further in vivo study.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 1.

- Culturing of Fibroblasts cells:

- 2.

- Subculturing procedure:

- 3.

- Cytotoxicity techniques:

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Disclosure

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qian, L.W.; Fourcaudot, A.B.; Yamane, K.; You, T.; Chan, R.K.; Leung, K.P. Exacerbated and prolonged inflammation impairs wound healing and increases scarring. Wound Repair Regen. 2016, 24, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023, 6, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, R.M.; Costerton, J.W. Biofilms: Survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002, 15, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daeschlein, G. Antimicrobial and antiseptic strategies in wound management. Int Wound J. 2013, 10 (s1), 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, V. Classifications for wound bed preparation and stimulation of chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2000, 8, 347–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel, S.; Lagrafeuille, R.; Souweine, B.; Forestier, C. Antibiofilm activity as a health issue. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, J.; Reitzel, R.A.; Vargas-Cruz, N.; Chaftari, A.M.; Hachem, R.; Raad, I. Caprylic and polygalacturonic acid combinations for eradication of microbial organisms embedded in biofilm. Front Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1999–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, G.; Valle, M.F.; Malas, M.; Qazi, U.; Merutha, N.M.; Doggett, D.; Fawole, O.A.; Bass, E.B.; Zenilman, J. Chronic venous leg ulcer treatment: Future research needs. Wound Repair Regen. 2014, 22, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, M.; Järbrink, K.; Divakar, U.; Bajpai, R.; Upton, Z.; Schmidtchen, A.; Car, J. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell Microbiol. 2009, 11, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Sinha, M.; Mathew-Steiner, S.; Das, A.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Chronic wound biofilm model. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015, 4, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J. Biological Performance of Materials: Fundamentals of Biocompatibility. 2006, 4th ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, p520.

- Piccinini, F.; Tesei, A.; Arienti, C.; Bevilacqua, A. Cell counting and viability assessment of 2D and 3D cell cultures: expected reliability of the trypan blue assay. Biological procedures online. 2017, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2015, 21, A.3B.1–A.3B.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.; Wilson, I.; Orton, T.; Pognan, F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem. 2000, 267, 5421–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nasiry, S.; Geusens, N.; Hanssens, M.; Luyten, C.; Pijnenborg, R. The use of Alamar Blue assay for quantitative analysis of viability, migration, and invasion of choriocarcinoma cells. Human Reproduction. 2007, 22, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longhin, E.M.; El Yamani, N.; Rundén-Pran, E.; Dusinska, M. The Alamar blue assay in the context of safety testing of nanomaterials. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 981701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerges, B.Z.; Rosenblatt, J.; Truong, Y.L.; Reitzel, R.A.; Hachem, R.; Raad, I. Enhanced biofilm eradication and reduced cytotoxicity of a novel polygalacturonic and caprylic acid wound ointment compared with common antiseptic ointments. BioMed Res Int 2710, 2710484. eCollection. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, R.Y.; Hakim, C.; Dagher, H.; Samaha, R.; Hammoudeh, D.; Hamerschlak, N.; Nasr, J.; Rosenblatt, J.; Jiang, Y.; Chaftari, A.M.; Ghanem, O.; Ibrahim, A.; Bizri, A.R.; Raad, I. Novel polygalacturonic and caprylic Acid (PG+CAP) antimicrobial wound ointment is effective in managing microbially contaminated chronic wounds in a pilot prospective randomized clinical study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10, ofad500.434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goemans, C.V.; Collet, J.F. Stress-induced chaperones: a first line of defense against the powerful oxidant hypochlorous acid. F1000Res. 2019, 8, 1678–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau, M.; Muñoz, E.; Lujan, E.; Larrosa, N.; Gomis, X.; Len, E.M.O.; Almirante, B.; Colominas, A.J.S.; Gavald, J. In Vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activity of hypochlorous acid against drug-resistant and biofilm-producing strains. Microbiol Spectr. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bassiri, M.; Najafi, R.; Najafi, K.; Yang, J.; Khosrovi, B.; Hwong, W.; Barati, E.; Belisle, B.; Celeri, C.; Robson, M.C. Hypochlorous acid as a potential wound care agent: part I. Stabilized hypochlorous acid: a component of the inorganic armamentarium of innate immunity. J Burns Wounds 2007, 6, e5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Bohn, G.; Glat, P.; Kavros, S.J.; Kirsner, R.; Snyder, R.; Tettelbach, W. Expert recommendations for the use of hypochlorous solution: science and clinical application. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2015, 61, S2–S19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, C.C.; Ding, S.J. Effectiveness of hypochlorous acid to reduce the biofilms on titanium alloy surfaces in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2016, 17, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Sleiman, J.; Johani, K.; Vickery, K. Hypochlorous acid versus povidone-iodine containing irrigants: which antiseptic is more effective for breast implant pocket irrigation? Aesthet Surg J. 2018, 38, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joachim, D. Wound cleansing: benefits of hypochlorous acid. J of Wound Care. 2020, 29 (Sup10a), S4–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yash, S.R.; Flurin, L.; Abdelrhman, M.; Kerryl, E.G.; Haluk, B.; Robin, P. In vitro antibacterial activity of hydrogen peroxide and hypochlorous acid, including that generated by electrochemical scaffolds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e01966-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, M.; Stuermer, E.K. Efficiency of antiseptics in a novel three-dimensional human plasma biofilm model (hpBIOM). NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes. 2019, 10, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Y.L.; Rosenblatt, J.S.; Raad, I. Nitroglycerin inhibition of thrombin-catalyzed gelation of fibrinogen. J Pharm & Clin Toxicol 2022, 10,1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, Z.G.; Rosenblatt, J.; Truong, Y.L.; Jiang, Y.; Raad, I. The antifungal activity of a polygalacturonic and caprylic acid ointment in an in vitro, three-dimensional wound biofilm model. J Fungi. 2025, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.; Figueiral, M.H.; Fernandes, M.H.R.; Scully, C. Cytotoxicity of denture adhesives. Clin Oral Investig. 2011, 15, 885–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Leibovich, S.J. Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Cell Biol. 2005, 15, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, T.J.; DiPietro, L.A. Inflammation, and wound healing: The role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2013, 13, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landén, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: a critical step during wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdai, F.; Risaliti, C.; Monici, M. Role of fibroblasts in wound healing and tissue remodeling on Earth and in space. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022, 4, 958381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, N.B.; Ward, K.R.; Witten, T.M.; Bonchev, D.G.; Diegelmann, R.F. Impaired wound healing. Clinics in dermatology. 2007, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velnar, T.; Bailey, T.; Smrkolj, V. The wound healing process: An overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Int Med Res. 2009, 37, 1528–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, I.S. Advances in fibrin-based materials in wound repair: a review. Molecules. 2022, 14, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, K.; Saleha, S.; Zhu, X.; Huo, L.; Basit, A.; Franco, O.L. Bacterial contribution in chronicity of wounds. Microb Ecol. 2017, 73, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, C.; Satyamoorthy, K.; Murali, T.S. Microbial interplay in skin and chronic wounds. Current Clinical Microbiology Reports. 2022, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecker, D.; Zhang, Z.; Breves, R.; Herth, F.; Kramer, A.; Bulitta, C. Antimicrobial efficacy, mode of action and in vivo use of hypochlorous acid (HOCl) for prevention or therapeutic support of infections. GMS Hyg Infect Control 2023, 27, Doc07. eCollection 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, L.K.; Candeias, L.P.; Wardman, P. Kinetics, and mechanisms of hypochlorous acid reactions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995, 20, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembe, J.D.; Huelsboemer, L.; Plattfaut, I.; Besser, M.; Stuermer, E.K. Antimicrobial hypochlorous wound irrigation solutions demonstrate lower anti-biofilm efficacy against bacterial biofilm in a complex in-vitro human plasma biofilm model (hpBIOM) than common wound antimicrobials. Front Microbiol. 2020, 9, 564513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.A.; Rhee, M.S. Marked synergistic bactericidal effects and mode of action of medium-chain fatty acids in combination with organic acids against Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013, 79, 6552–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, T.M.; Kanunfre, C.C.; Pompeia, C.; Verlengia, R.; Curi, R. Ranking the toxicity of fatty acids on Jurkat and Raji cells by flow cytometric analysis. Toxicol In Vitro. 2002, 16, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, B.Z.; Rosenblatt, J.; Truong, Y.L.; Raad, I. Polygalacturonic acid partially inhibits matrix metalloproteinases and dehydration in wounds. Wounds. 2024, 36, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.J.; Northcote, D.H. Apple fruit pectic substances. Biochem J. 1965, 94, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.J.; Tham, P.E.; Khoo, K.S.; Cheng, C.K.; Chew, K.W.; Show, P.L. A comprehensive review on the techniques for coconut oil extraction and its application. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2021, 44, 1807–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervajio, G.C. Fatty acids and derivatives from coconut oil. Bailey’s industrial oil and fat products. 2005, 8, 1-56. [CrossRef]

| Efficacy variable | Tested organism | |||

| MRSA |

MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

CRE Escherichia coli |

Streptococcus pyogenes | |

| Log10 median viable colonies for negative control | 8.00E+07 | 2.31E+08 | 2.25E+07 | 2.43E+07 |

| Log10 reduction of CFU with PG+CAP relative to negative control | 7.9 | 8.28 | 4.26 | 5.12 |

| Log10 reduction of CFU with HOCl relative to negative control | 4.2 | 2.32 | 1.69 | 3.0 |

| P value for PG+CAP versus HOCl | 0.0028 | 0.0043 | 0.005 | 0.019 |

|

Treatment |

Mean ± SD cells |

% Viable |

P value* | P value** | |

| Live cells | Dead cells | ||||

| Negative control | 2.69 × 106 ± 7.59 × 104 | 6.0 × 104 ± 8.16 × 103 | 97.82 | 0.26 | - |

| 2% PG+CAP | 2.65 × 106 ± 3.77 × 104 | 6.5 × 104 ± 5.77 × 103 | 97.61 | - | 0.26 |

| 2% HOCl | 2.46 × 106 ± 4.83 × 104 | 4.43 × 105 ± 1.50 × 104 | 84.76 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | Median reading | Interquartile range | P value* | P value** |

| Negative control | 1.124 | 1.121 - 1.129 | 0.083 | - |

| 2% PG+CAP | 1.111 | 1.108 - 1.131 | - | 0.083 |

| 2% HOCl | 0.942 | 0.848 - 1.00 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).