1. Introduction

Bacterial resistance to antibiotic represents one of the most pressing global health challenges of the 21st century (WHO, 2024). The increase in infections caused by resistant pathogens not only limits therapeutic options, but also increase morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs. Among these pathogens, methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has been designated as a critical priority by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) due to its high prevalence and clinical impact [

1,

2,

3].

MRSA is responsible for a wide range of acute and chronic infections, both hospital-acquired (HA-MRSA) and community-acquired (CA-MRSA). While HA-MRSA is a major cause of pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and surgical site infections, CA-MRSA is mainly associated with skin and soft tissue infections, but can also cause serious conditions such as osteomyelitis and toxic shock syndrome [

4,

5,

6]. In addition, MRSA plays a key role in chronic lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, where its ability to form biofilms and acquire antibiotic-tolerant phenotypes makes it difficult to eradicate and worsens patient outcomes [

7,

8]. The pathogenic success of

S. aureus lies in its diverse arsenal of virulence factors that facilitate colonization, immune evasion and tissue invasion. In particular, Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), which is more frequently associated with CA-MRSA strains, induces neutrophil lysis and contributes to tissue necrosis. Enterotoxins and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) are implicated in foodborne illness and systemic toxicity. In addition, adhesin expression and biofilm-forming ability enable persistence in host tissues and medical devices, further enhancing resistance. Protein A, coagulase, and capsular polysaccharides also contribute to immune evasion and virulence [

9,

10,

11,

12].

The global propagation of MRSA strains resistant to multiple antibiotic classes has prompted an urgent search for alternative antimicrobial strategies [

13,

14]. Among these, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have shown promise due to their Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status, natural antimicrobial activity and their health-promoting effects, particularly in maintaining gut health and modulating the immune system [

15,

16]. Recent studies have reported the ability of LAB to inhibit multidrug-resistant pathogens, including MRSA [

17,

18] . Our group recently demonstrated that

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CRL 2244 secretes antimicrobial compound(s) with bactericidal activity against carbapenem-resistant

Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) as well as other clinically relevant pathogens, including MRSA [

19]. Notably, these compounds also act synergistically with β-lactam antibiotics and vancomycin, restoring the susceptibility of

S. aureus strains resistant to these drugs [

19].

Based on these findings, the present study investigates the antimicrobial activity of the extract from

Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 against MRSA strains, with emphasis on its potential clinical application. We employed both phenotypic and transcriptomic approaches to assess the bactericidal effects of the extract on two representative MRSA strains: the epidemic community-associated USA300 clone (characterized by SCCmec type IVc and the PVL gene) [

20,

21] and the hospital-associated strain M86, isolated from a cystic fibrosis patient [

22]. In addition, we evaluated its efficacy in physiologically relevant conditions, such as human serum, collagen matrices and, fibronectin-binding assays—targeting a host protein crucial for

S. aureus colonization. This study provides new insights into the therapeutic potential of LAB-derived antimicrobials against multidrug-resistant pathogens in clinically complex infection scenarios.

3. Discussion

In a context of the growing threat posed by infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens such as MRSA, compounds derived from LAB have been postulated as innovative therapeutic alternatives. Their safety, metabolic diversity and ability to modulate virulence mechanisms without exerting direct selective pressure on bacterial viability make them attractive candidates for antivirulence strategies [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In particular, metabolites produced by LAB have shown inhibitory effects against multidrug-resistant clinical strains by impairing adhesion, interfering with biofilm-forming, and modulating the expression of virulence factor-associated genes, which is especially relevant in clinical settings involving implantable devices, such as heart valves or catheters, which promote colonization and persistent infections [

27,

28,

29].

In this study, we demonstrated that the extract derived from Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 exerts a modulatory effect on MRSA USA300 and M86 strains at both the transcriptional and phenotypic levels, notably reducing staphyloxanthin production and adhesion capacity under host-mimicking conditions. Although the chemical identity of the active compound(s) remains undefined, the findings presented here represent a key step toward functional characterization and support the potential of CRL 2244 extract as an antivirulence agent for preventing or treating MRSA infections in clinical settings.

The extract showed robust antimicrobial activity against both community-associated (USA300) and hospital-associated (M86) MRSA strains, consistent with prior observations in CRAB strains [

19,

30], supporting the hypothesis of a broad-spectrum mechanism of action. The enhanced inhibition observed on blood agar plates suggests that medium components may influence the diffusion or stability of bioactive molecules, as previously reported [

31,

32]. Interestingly, the increased susceptibility of the isogenic USA300 Δ

hla mutant points to a link between virulence factors and extract sensitivity.

hla, which encodes α-hemolysin, plays a central role in

S. aureus cytotoxicity and immune evasion [

33]. Its deletion may reduce the pathogen’s capacity to counteract the stress imposed by the extract, as similarly observed with other antimicrobials targeting virulence factors [

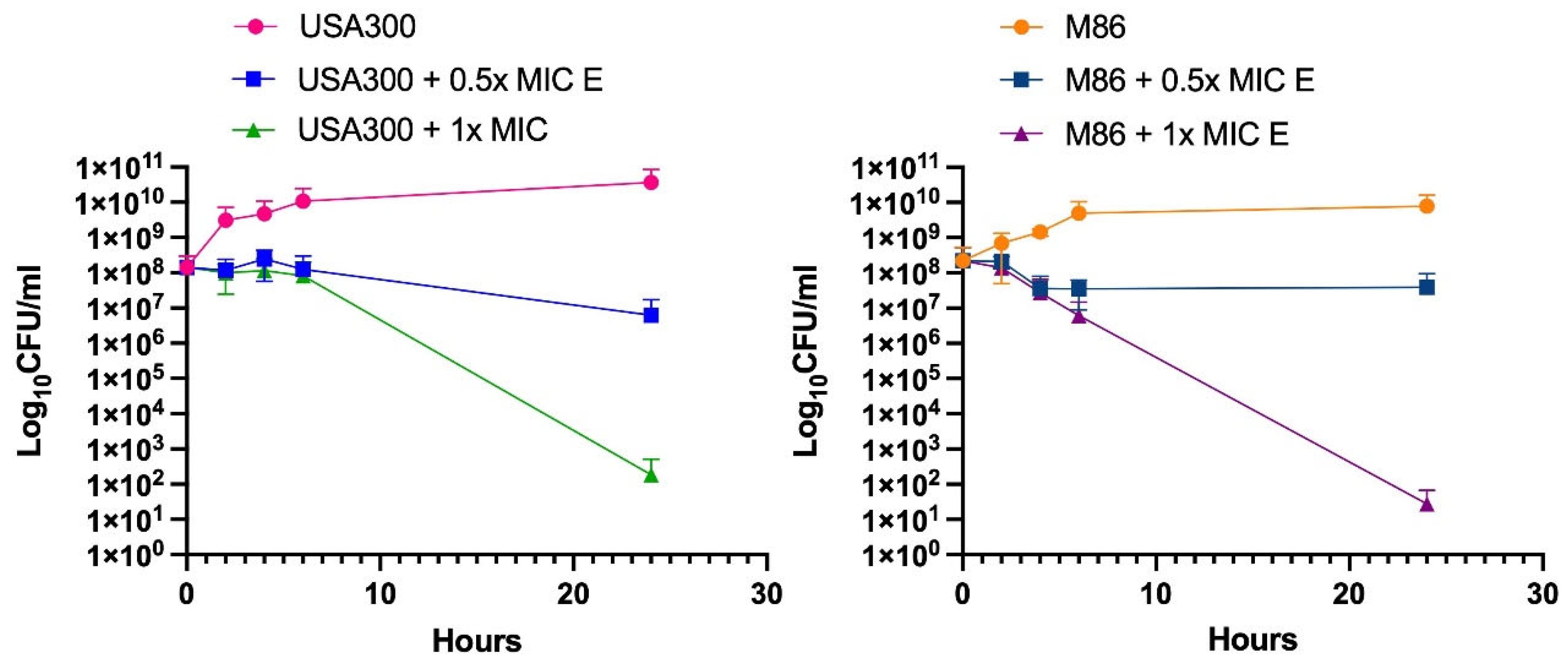

34]. Time-kill assays validated that the extract’s bactericidal activity, with reductions of up to 6 log

10 CFU/mL after 24 h at 1x MIC in both strains, similar to previous results with CRAB strains [

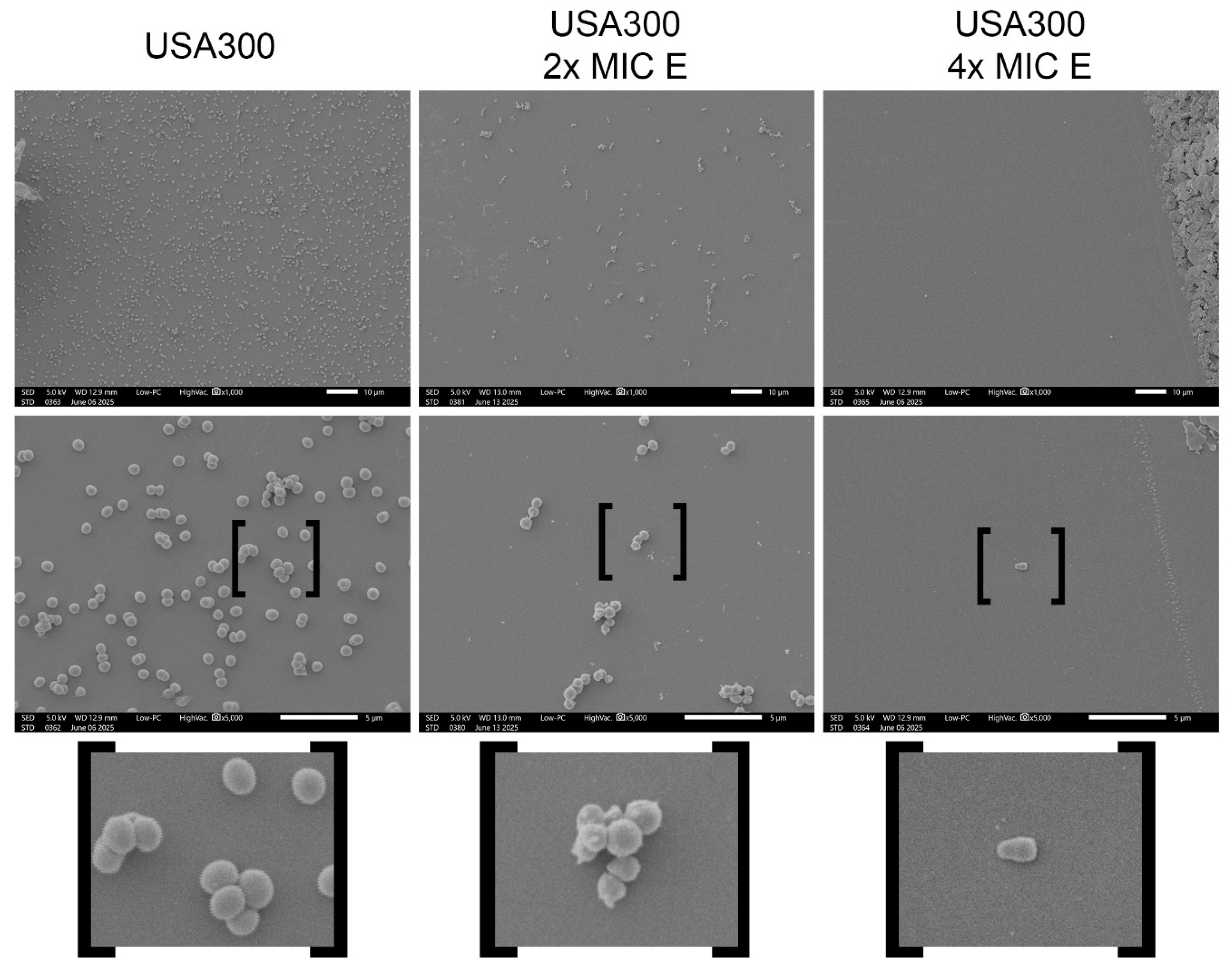

30]. Consistent with this potent bactericidal effect, SEM analysis revealed morphological alterations in

S. aureus cells exposed to the extract, including a reduction in cell density and an increase in cell length, features previously observed in other multidrug-resistant pathogens treated with this extract [

29]. These structural changes suggest a mechanism of action involving alteration of the cell envelope and were found to be dose-dependent, in agreement with the activity of the extract observed in CFU and MIC assays.

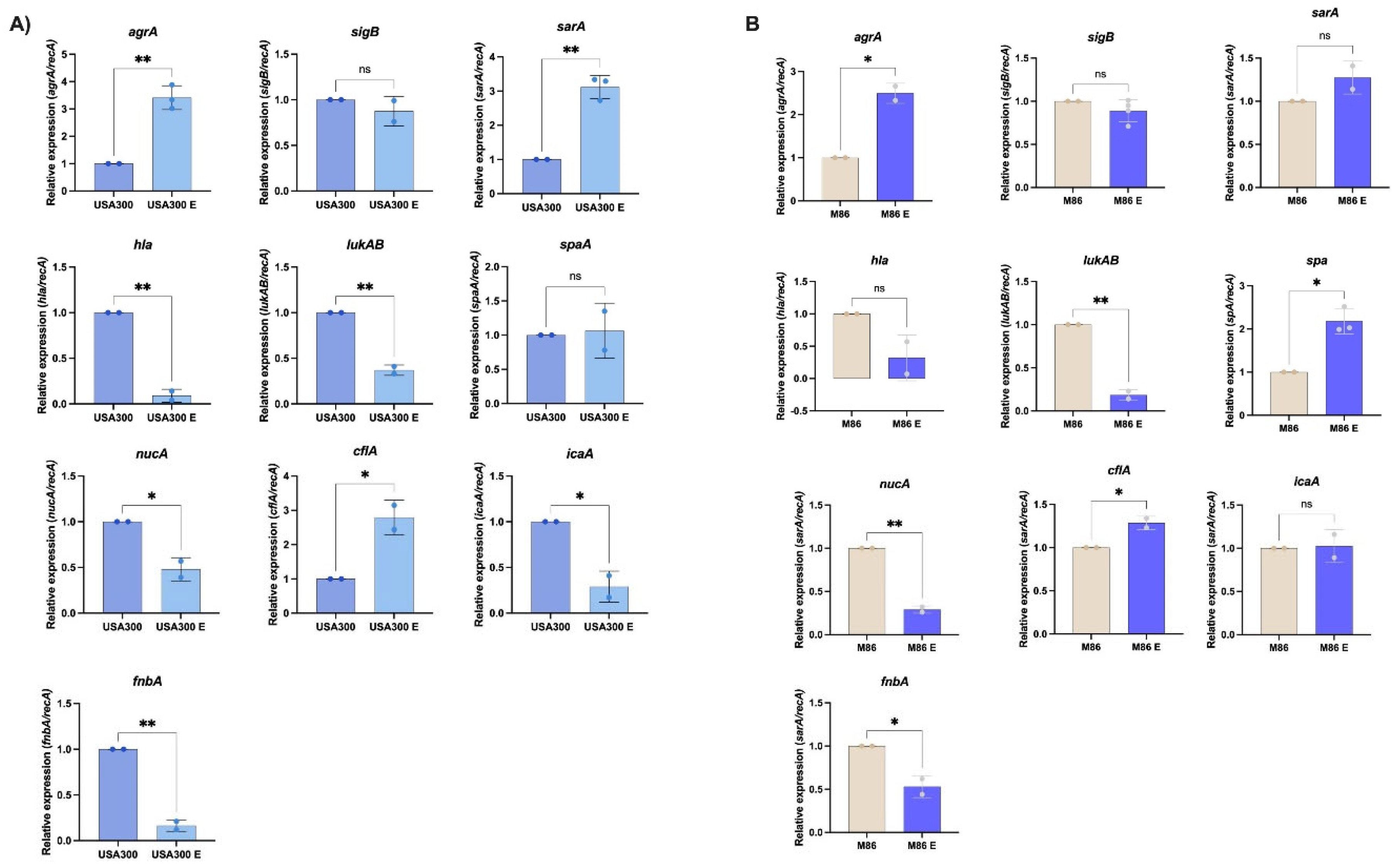

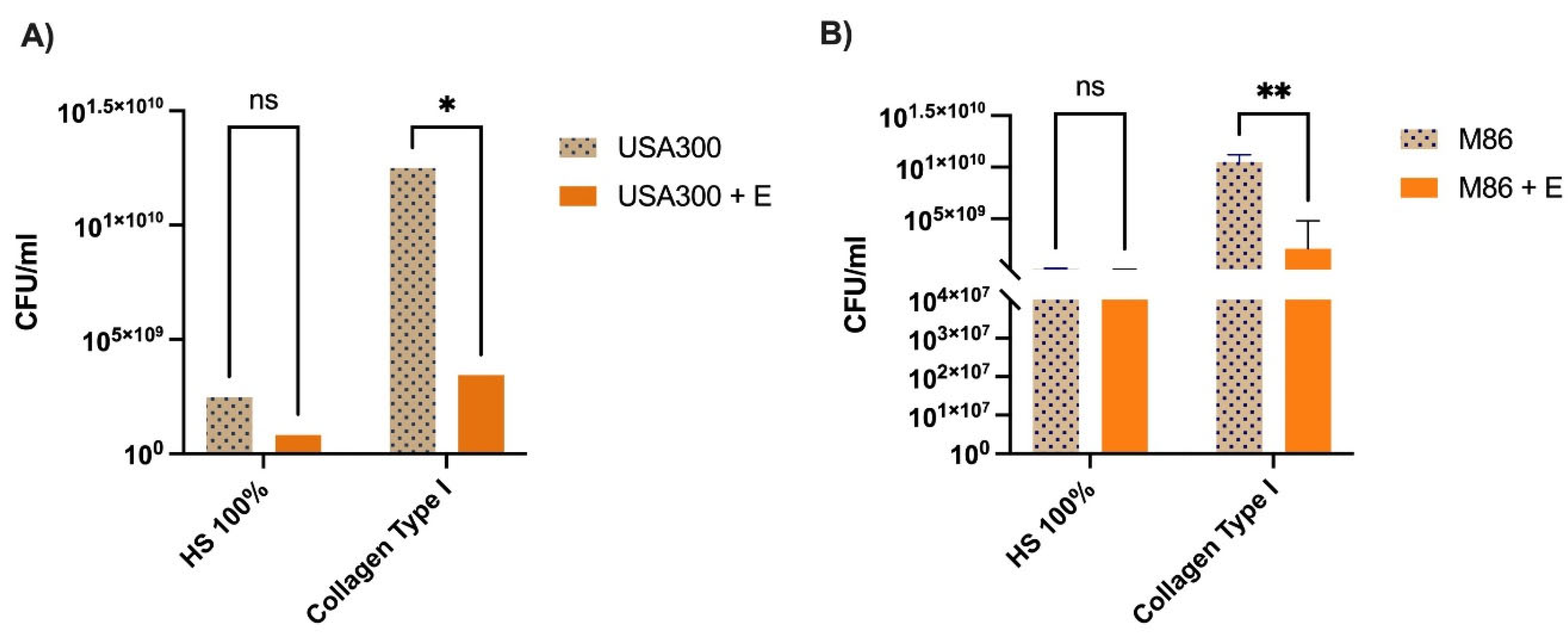

At the molecular level, the extract induced transcriptional changes consistent with virulence modulation. In USA300, we observed a broader transcriptional response than M86. USA300 showed overexpression of

agrA and

sarA, two master regulators of quorum sensing and biofilm formation, respectively. Despite this, expression of critical virulence genes—including

hla,

lukAB,

icaA, and

fnbA—was significantly reduced. This apparent decoupling between regulatory elements and effector genes suggests a reprogramming of the virulence profile rather than a global activation, a phenomenon previously reported in response to environmental or metabolic stimuli [

34]. Wang et al. (2024) demonstrated that

Lcb. rhamnosus P118 can produce tryptophan-derived metabolites (e.g., indole) that modulate host inflammation [

35]. While immunomodulatory effects were not assessed in this study, reduced expression of key toxins (

hla,

lukAB) may imply a diminished capacity to trigger host inflammatory responses.

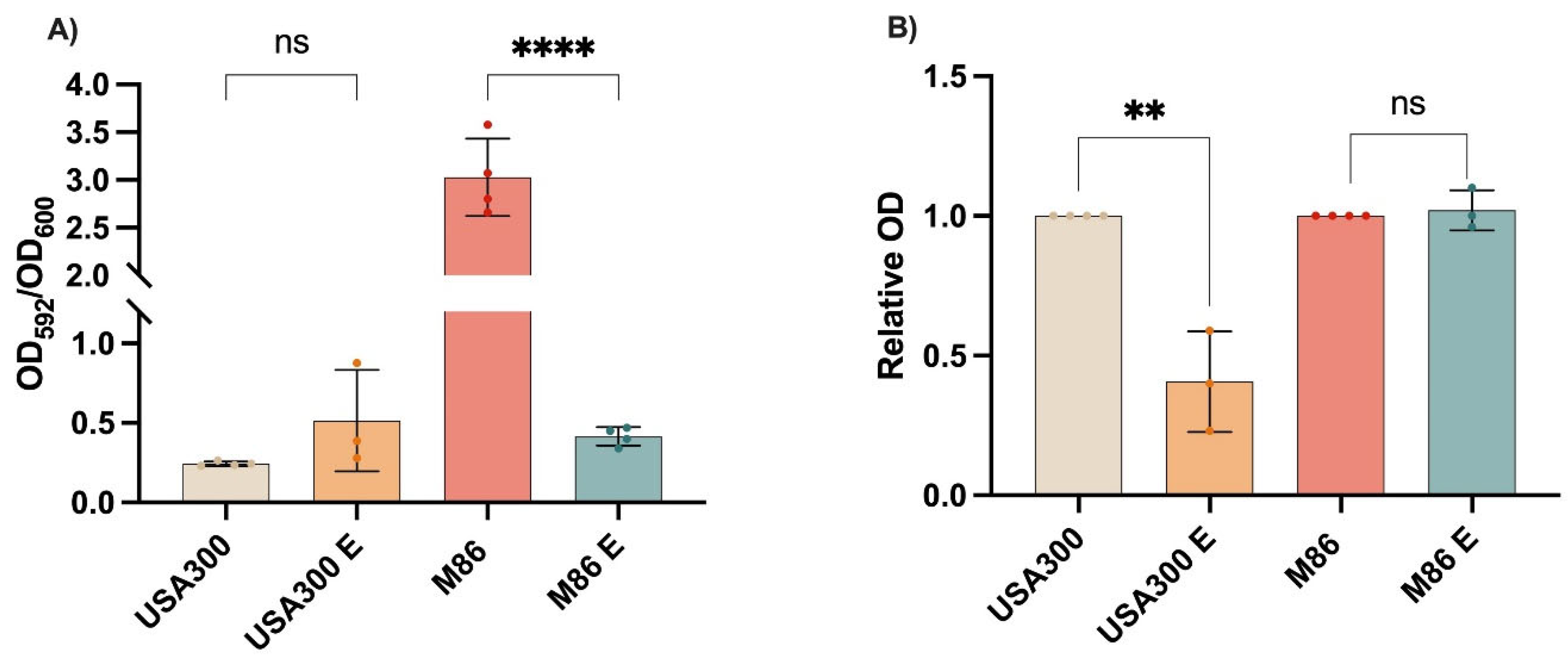

Phenotypically, USA300 did not exhibit significant biofilm changes, likely due to its low basal biofilm formation under tested conditions. In contrast, staphyloxanthin production was markedly reduced, correlating with

hla repression and potentially a less oxidative cellular environment. As a key antioxidant carotenoid, staphyloxanthin protects

S. aureus from host-derived stress [

36,

37]. Reduction of staphyloxanthin, possibly mediated by

sarA repression, could increase the vulnerability of the pathogen, reinforcing its value as an antivirulence target [

38,

39]. In line with this hypothesis, prior studies have shown that natural compounds and anti-inflammatory drugs can disrupt staphyloxanthin biosynthesis [

40].

The M86, by contrast, showed a more restricted transcriptional response. While

sarA,

hla, and

icaA expression remained unchanged, we observed increased expression of

agrA and

spa, and repression of

lukAB,

nucA, and

fnbA. These molecular changes correlated with a pronounced reduction in biofilm formation, suggesting the extract may be particularly effective against high biofilm-forming strains—a trait also observed in CRAB [

29]. The downregulation of

nucA, involved in extracellular DNA degradation and biofilm dispersal [

41], may reflect alterations in biofilm matrix maturation or stability. In contrast to USA300, M86 showed no changes in levels of staphyloxanthin production, likely due to stable expression of biosynthesis-related genes such as

sigB or

crtM, which were not analyzed in this study.

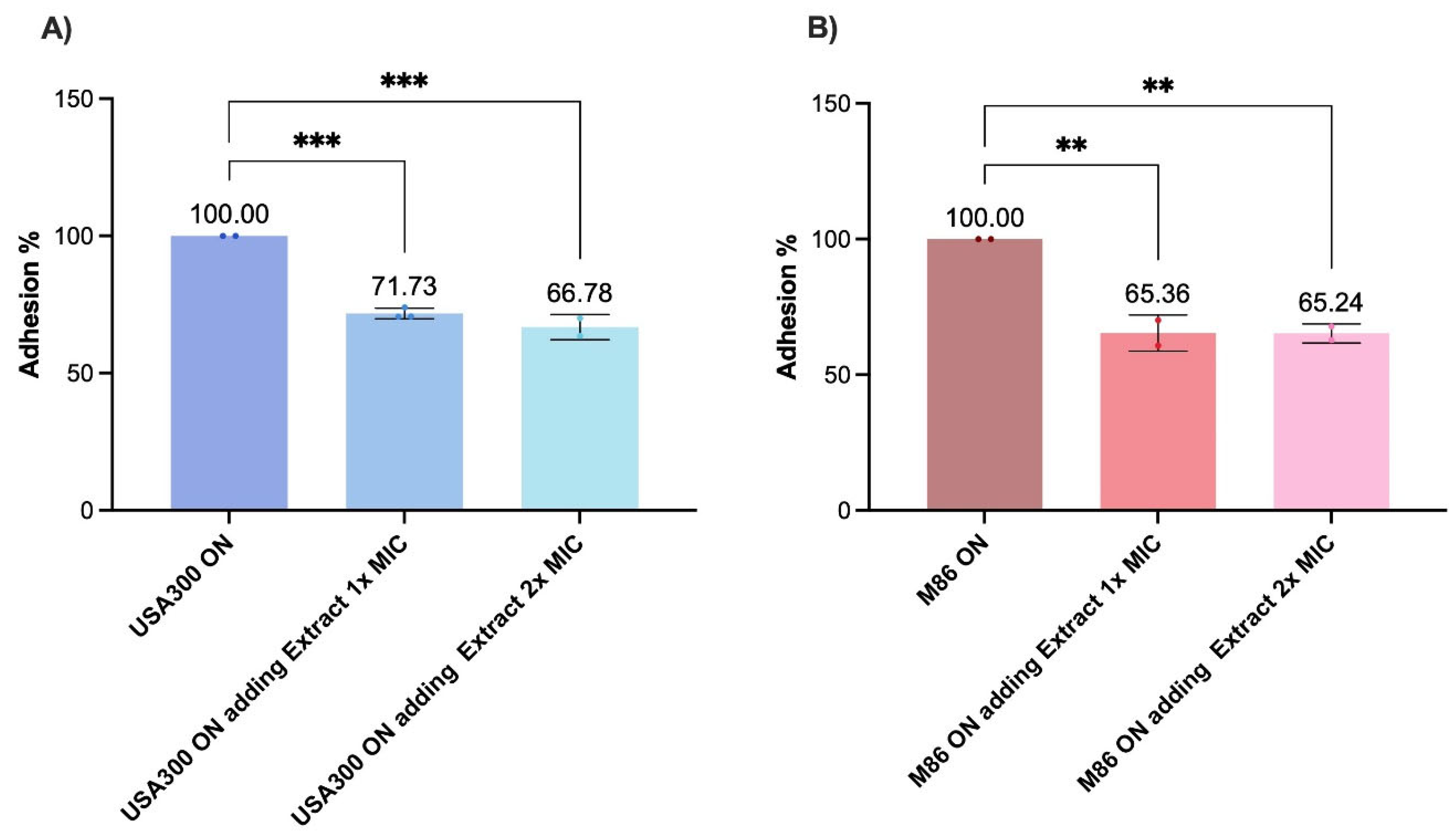

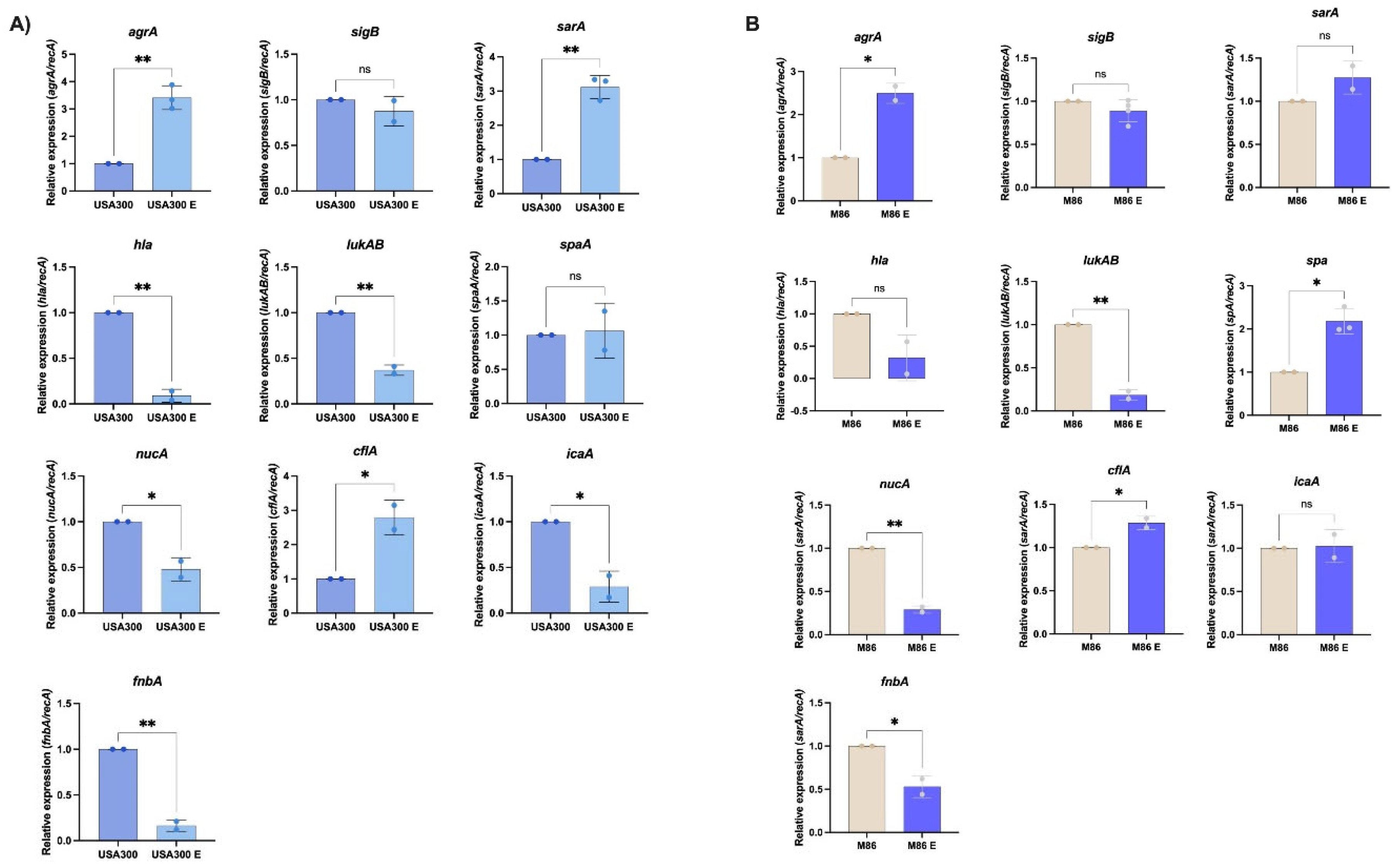

When tested under host-mimicking conditions, the CRL 2244 extract’s activity varied. In human serum, no significant reduction in bacterial viability was detected, suggesting low cytotoxicity in protein-rich environments. However, a significant decrease in cell viability was observed in the presence of type I collagen, particularly for M86. This indicates that certain components of the tissue microenvironment may sensitize MRSA to the effect of the extract, in agreement with studies showing that interaction with extracellular matrix proteins modulates virulence and antimicrobial susceptibility of

S. aureus [

9,

42]. Adhesion assays using fibronectin-coated surfaces showed that the extract impaired MRSA anchoring, even at subinhibitory concentration, showing a strong effect in the highly adherent M86 strain. This phenotype correlates with reduced expression of key adhesion genes such as

fnbA and

icaA, supporting the hypothesis that CRL 2244 extract interferes with early colonization—an essential step in staphylococcal pathogenesis and biofilm-associated infections [

34].

Finally, like transcriptomic studies by Peng et al. (2023) who showed that

Lcb. rhamnosus SCB0119 modulates key genes in

E. coli and

S. aureus, we observed repression of

hla,

lukAB, and

fnbA, along with functional reductions in adhesion and staphyloxanthin production [

43]. These findings support the concept that LAB-derived compounds can reprogram virulence traits in a strain-dependent manner, reinforcing their value as antivirulence rather than bactericidal agents.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

USA300 (CA-MRSA) [

20,

44] and M86 (HA-MRSA) [

22] strains were used in this work. In addition, a total of six

S. aureus (SA) USA 300 mutants were used for spot-on-the-lawn assays to test antimicrobial activity (

Table 1). The mutant in

agrA, sarA, lukS-PV,

cflA,

fnbA (Nebraska Tn Mutant Library), and

hla [

45]. The strains were grown on Cystine-Lactose Electrolyte-Deficient (CLED) medium (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) overnight at 37˚C and used within 24 h.

4.2. Preparation of Extracts from Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244

To obtain the crude cell-free extract, cell free conditioning media (CFCM) of Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 incubated for 96 h under appropriate growth conditions was used. After incubation, the culture was filtered and immediately subjected to lyophilization using a Virtis 4K benchtop lyophilizer. The lyophilized material was resuspended in 250 mL of deionized water and extracted by liquid-liquid partitioning with ethyl acetate (1:1 v/v) in a 2000 mL separatory funnel. The mixture was shaken vigorously and allowed to separate; the organic phase was collected. The aqueous phase was re-extracted twice with decreasing volumes of ethyl acetate (200 mL and 190 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried with ~30 g anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered and concentrated using a rotary evaporator (IKA RV 10 digital V) set at 150 rpm with gradually reduced pressure from 395 mbar to 75 mbar over 20-30 min. The concentrated extract was stored at -20 °C and used without further purification.

4.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assays

The antimicrobial activity of the

Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract was assessed using a modified version of the well diffusion method outlined in a previous study [

19]. Bacterial strains were resuspended in sterile saline solution (0.85% NaCl, w/v) to a concentration of 0.5 McFarland units (1.5 x 10

8 CFU/mL). These suspensions were then inoculated onto CLED and blood agar plates. A volume of 10 μL of the extract (800 μg/μL) was applied to the surface of the plates. After incubating at 37 °C for 24 hours, the inhibition zone diameters (IDH) were measured. The results were categorized as follows: less active (IDH ≤ 10 mm), moderately active (IDH = 11–14 mm), and highly active (IDH ≥ 15 mm) [

46]. All assays were conducted using three independent biological replicates.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the extract was determined against MRSA strains USA300 and M86 by broth microdilution following CLSI guidelines [

47]. Briefly, serial two-fold dilutions of the extract were prepared in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton (CAMH) broth in 96-well microplates. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to approximately 5 x 10⁵ CFU/mL and added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and bacterial growth was assessed visually. The MIC was defined as the lowest extract concentration that completely inhibited visible growth.

4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

To evaluate the reduction in cellular density and morphological changes induced by the extract, SEM was performed on cultures of strain USA300. A standardized inoculum (0.5 McFarland), prepared from colonies grown overnight on LB agar at 37 °C, was used to inoculate 2 mL of LB broth supplemented with the extract at 2x and 4x MIC. As a control, USA300 was cultured under identical conditions in LB broth without the addition of the extract. After incubation for 18-20 h at 37 °C, the cells were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min, washed twice with sterile saline solution and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde solution. Cells were deposited on protamine coated glace slides, dehydrated in an ethanol series and critical point dry for subsequent visualization at the core imaging Lab, Department of Biological Science, CSUF with the JCM-7000 NeoScope™ Benchtop SEM.

Bacterial growth of the samples, prior fixation, was assessed by serial dilution and colony counting.

4.5. Time-Killing Assay

The bactericidal effect of the extract was evaluated against MRSA USA300 and M86 strains for a period of 24 h, following a previously described protocol [

19]. The assays were performed in tubes using a bacterial inoculum prepared by 1:10 diluting a 0.5 McFarland (1.5 x 10

8 CFU/mL) suspension in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Cultures were exposed to the extract at concentrations of 0.5x MIC and 1x MIC, while untreated cultures (no extract) were used as controls.

Samples were incubated at 37 °C with shaking, and bacterial viability was assessed at 0, 2, 4, 6 and 24 h by serial dilutions and cultures on CLDE agar. Colony forming units (CFU) were counted after overnight incubation at 37 °C. Each condition was tested in two independent experiments, performed in duplicates. In addition, a time-killing assay with a 0.5x MIC of ampicillin and 0.5x MIC of ampicillin plus 0.5x MIC of the extract was performed to observed synergy or additive effects.

4.6. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Assays

MRSA strains USA 300 and M86 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 2.5 µg/µL of extract (sub-MIC concentration= 0.5x MIC) for 18 hours at 37 °C. Total RNA was extracted in triplicate for each condition using a commercial kit (Direct-zol RNA Kit, ZymoResearch), following treatment with 10 mg/mL of Lysostaphin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 50 mM EDTA buffer for 1 hour at 37 °C. DNase-treated RNA was then used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis with the iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA concentrations were adjusted to 50 ng/µL, and qPCR was performed using qPCRBIO SyGreen Blue Mix Lo-ROX, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (PCR Biosystems, Wayne, PA, USA). Each qPCR assay included at least three biological replicates of cDNA and was performed in triplicate using the CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The data were presented as NRQs (normalized relative quantities), calculated using the qBASE method [

48,

49], with

recA genes as normalization controls. Experimental data were obtained from technical triplicates of three independent biological replicates. Statistically significant differences were indicated by asterisks and determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (P < 0.05), using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

4.7. Biofilm Formation Assay

Biofilm formation in MRSA strains USA300 and M86 was assessed using Terrific Broth (TB) and Luria-Bertani (LB) media to enhance stress conditions. The assay was adapted from the protocol described by Rodriguez et al 2023 [

30], with modifications to perform it in test tubes. Bacterial cultures were prepared under two conditions: a control group consisting of 1.5 mL of LB medium and 150 µL of bacterial suspension adjusted to 0.5 McFarland, and a treatment group with the same inoculum supplemented with the extract at 0.5x MIC. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h without shaking to promote biofilm development.

After incubation, planktonic cells were removed, and the remaining biofilm was stained with 1% crystal violet solution for 30 minutes. Excess dye was discarded, and tubes were washed twice with 1x PBS. Samples were then air-dried, and the retained stain was solubilized with 30% (v/v) acetic acid for 30 minutes. Optical density was measured at 592 nm. Total biomass was previously determined by OD600 before washing, and results were expressed as the ratio between biofilm biomass and total biomass (OD592/OD600).

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05.

4.8. Staphyloxanthin Production Assay

The production of staphyloxanthin in MRSA strains USA300 and M86 was assessed following the protocol described by Morikawa (2021) [

50]. Briefly, the strains were inoculated in terrific broth and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, with and without exposure to a sub-MIC concentration (2.5 µg/µL) of the extract and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h with agitation. Subsequently, 850 µL of the culture was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 1 minute, washed with distilled water, and resuspended in 200 µl of methanol. The samples were then heated at 55 °C for 5 minutes and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 minute to remove cellular debris. The extraction process was performed twice, and the resulting extracts were pooled into a single tube, adjusting the final volume to 1 mL with methanol. Finally, absorbance was measured at 465 nm.

The relative absorbance (RA) was calculated using the equation RA = A_treated/A_control. The results were interpreted as follows: RA = 1 indicates no effect of the antimicrobial on staphyloxanthin production; RA < 1 suggests a reduction in its production; and RA > 1 may indicate either an unexpected effect or an antimicrobial-induced increase in production.

4.9. Human Fluids Survival Assay

The effect of the extract on bacterial survival in human fluids was evaluated in MRSA strains USA300 and M86. Assays were conducted using two conditions: 100% human serum (Innovative Research, USA, certified vendor approved by ISO, FDA, USDA, and EPA) and LB broth supplemented with type I collagen (8 µg/mL physiological concentration, CalBiochem Inc). In both cases, cultures were prepared in a final volume of 1 mL, containing 100 µL of an overnight bacterial culture (adjusted to 0.5 McFarland), with or without the addition of extract at 1x MIC (5.85 µg/ml final concentration). Samples were incubated overnight at 37 °C with agitation. Bacterial viability was determined by serial dilution and plating on CLDE agar to calculate CFU/mL. Each condition was tested in two independent experiments, performed in duplicate.

4.10. Adhesion Assay

The effect of the extract on bacterial adhesion of MRSA strains USA300 and M86 was evaluated using 96-well microplates coated with Corning® BioCoat® Fibronectin Clear Flat Bottom TC, following the protocol described by Peacock et al. (2000) [

51]. Fibronectin-coated wells were inoculated with 100 µL of bacterial suspensions in LB broth incubated overnight under the following conditions: untreated control (overnight cultures in LB), and co-treatment during adhesion, in which overnight cultures were added together with extract at 1x MIC or 2x MIC directly into the wells. After inoculation, all plates were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the wells were washed three times with 1x PBS, fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde for 1 h, stained with 1% crystal violet for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water and air dried. The stain was then solubilized with 30% acetic acid and absorbance was measured at 405 nm to quantify adherent biomass. Adhesion was expressed as relative adhesion ratio (AR = A_treated/A_control) and as percentage adhesion relative to control (% Adhesion = [A_treated/A_control] × 100). All conditions were tested in triplicate in at least two independent experiments.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in technical duplicate or triplicate and repeated in at least three independent biological replicates, unless otherwise indicated. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism, applying one-way or two-way ANOVA depending on the experimental design. Where appropriate, Tukey’s multiple comparison test or unpair two-tailed Student’s t-test was used as post hoc analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significance levels are indicated in the legend of each figure as follows: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns = not significant.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of S. aureus USA300 exposed to the CRL 2244 extract. Representative SEM micrographs of USA300 cells grown under (A) control conditions, (B) treatment with 2x MIC of the extract, and (C) treatment with 4x MIC of the extract. All images were taken at 1,000x, and 5,000x magnification; scale bars represent 10 μm and 5 μm.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of S. aureus USA300 exposed to the CRL 2244 extract. Representative SEM micrographs of USA300 cells grown under (A) control conditions, (B) treatment with 2x MIC of the extract, and (C) treatment with 4x MIC of the extract. All images were taken at 1,000x, and 5,000x magnification; scale bars represent 10 μm and 5 μm.

Figure 2.

Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract killing activity against MRSA. The strains USA300 and M86 were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in presence of extract at 0.5x MIC and 1x MIC. CFU/mL were determined at different incubation times for a period of 24 h. All assays were carried out in technical duplicates.

Figure 2.

Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract killing activity against MRSA. The strains USA300 and M86 were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in presence of extract at 0.5x MIC and 1x MIC. CFU/mL were determined at different incubation times for a period of 24 h. All assays were carried out in technical duplicates.

Figure 3.

Differential gene expression profiles of MRSA strains to Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract. The clinical isolates USA300 (A) and M86 (B) were grown with and without sub-MIC concentration of extract from Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 for 18 h at 37 °C. The differential gene expression was determined by qRT-PCR of genes involved in quorum sensing (agrA), global transcriptional regulation (sarA and sigB), immune evasion (spaA), cytotoxin production (hla and lukAB), biofilm formation (icaA), surface adhesion (fnbA and clfA), and nucleic acid degradation (nucA), all of which are key factors in S. aureus virulence. The data presented are the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of normalized relative to recA transcript levels calculated using the qBASE method. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by T-test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ns, not significant. Experimental data were obtained from technical triplicates of three independent biological replicates. Error bars indicate SD.

Figure 3.

Differential gene expression profiles of MRSA strains to Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract. The clinical isolates USA300 (A) and M86 (B) were grown with and without sub-MIC concentration of extract from Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 for 18 h at 37 °C. The differential gene expression was determined by qRT-PCR of genes involved in quorum sensing (agrA), global transcriptional regulation (sarA and sigB), immune evasion (spaA), cytotoxin production (hla and lukAB), biofilm formation (icaA), surface adhesion (fnbA and clfA), and nucleic acid degradation (nucA), all of which are key factors in S. aureus virulence. The data presented are the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of normalized relative to recA transcript levels calculated using the qBASE method. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by T-test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ns, not significant. Experimental data were obtained from technical triplicates of three independent biological replicates. Error bars indicate SD.

Figure 4.

Effect of Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract on virulence features of MRSA strains USA300 and M86. (A) Biofilm formation (B) Relative staphyloxanthin production. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc test (ns = not significant; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Effect of Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract on virulence features of MRSA strains USA300 and M86. (A) Biofilm formation (B) Relative staphyloxanthin production. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc test (ns = not significant; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

Effect of Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract on MRSA survival in human serum and collagen-supplemented medium. Viability of MRSA strains USA300 (A) and M86 (B) was evaluated after exposure to extract (E) under two physiologically relevant conditions: 100% human serum (HS) and LB broth supplemented with type I collagen (8 µg/mL). Bacterial survival was expressed as log₁₀ CFU/mL. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. *p < 0.01; p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

Figure 5.

Effect of Lcb. rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract on MRSA survival in human serum and collagen-supplemented medium. Viability of MRSA strains USA300 (A) and M86 (B) was evaluated after exposure to extract (E) under two physiologically relevant conditions: 100% human serum (HS) and LB broth supplemented with type I collagen (8 µg/mL). Bacterial survival was expressed as log₁₀ CFU/mL. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. *p < 0.01; p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

Figure 6.

Effect of the extract on adhesion of MRSA (A) USA300 and (B) M86 strains. Fibronectin-coated wells were inoculated with bacterial cultures incubated under different experimental conditions: co-treatment during the 2 h adhesion assay, in which overnight cultures together with extract at 1x MIC or 2x MIC and untreated control (overnight cultures in LB) were added to the wells. Adhesion was quantified by OD405 measurements after 2 h incubation at 37 °C. The results are expressed as absolute adhesion values (% relative to control). Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

Figure 6.

Effect of the extract on adhesion of MRSA (A) USA300 and (B) M86 strains. Fibronectin-coated wells were inoculated with bacterial cultures incubated under different experimental conditions: co-treatment during the 2 h adhesion assay, in which overnight cultures together with extract at 1x MIC or 2x MIC and untreated control (overnight cultures in LB) were added to the wells. Adhesion was quantified by OD405 measurements after 2 h incubation at 37 °C. The results are expressed as absolute adhesion values (% relative to control). Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract against S. aureus strains tested by the spot-on-the-lawn method.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CRL 2244 extract against S. aureus strains tested by the spot-on-the-lawn method.

| Strains |

Special features |

IDH (mm) |

| CLDE agar |

Blood agar |

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

|

|

| M86 |

Linezolid Resistance, PVL+ |

10 |

20 |

|

| USA 300 |

mecA, PVL+ |

12 |

20 |

|

| SAUSA 300 mutants |

|

|

|

|

| 1992 |

ΔagrA (accessory gene regulator protein A) |

16 |

19 |

|

| 0605 |

ΔsarA (accessory regulator A) |

15 |

nd |

|

| 1382 |

ΔlukS-PV (Panton-Valentine leukocidin, LukS-PV |

16 |

nd |

|

| 0772 |

ΔclfA (clumping factor A) |

18 |

nd |

|

| 2441 |

ΔfnbA (fibronectin binding protein A) |

16 |

nd |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| α-toxin |

hla (α-toxin) |

20 |

20 |

|