1. Introduction

Nosocomial infections, also known as healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), are infections that are acquired while receiving healthcare treatment in hospitals, long-term care facilities, or ambulatory care. These infections can affect patients as well as healthcare staff. A variety of pathogens can cause nosocomial infections, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses [

1]. Common among these different groups of pathogens is their resistance to the more potent drugs available in healthcare facilities, providing these pathogens with an infectious niche [

2]. Of these pathogens, bacteria are the most common causative agent of nosocomial infections. ESKAPE is an acronym used to describe six highly antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens that commonly cause nosocomial infections, which include

Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Enterobacter spp [

3].

While this study aims to curb the persistence of all ESKAPE pathogens, we focused on

A. baumannii as our model organism.

Acinetobacter spp. are Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria typically found in environmental microbiomes such as soil and water [

4]. Despite their environmental niches,

A. baumannii has been commonly detected and isolated from medical devices for several decades [

5].

Acinetobacter-associated nosocomial infections manifest in a variety of ways, including meningitis, pneumonia, as well as wound, burn and urinary tract infections [

6]. Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem affecting many different types of bacteria including

A. baumannii, which are highly resistant to antibiotics largely employed in hospital settings, including but not limited to quinolones, penicillins, and aminoglycosides [

7]. Of significance, many strains of

A. baumannii are resistant to carbapenems (i.e., carbapenem resistant

A. baumannii [CRAb]), the antibiotic reserved for multidrug resistant bacteria and considered to be a last resort antibiotic [

8]. Carbapenems function by gaining access through outer membrane proteins (porins) and acylating penicillin-binding proteins, proteins responsible for maintaining the peptidoglycan in the bacterial cell wall [

9]. This high level of resistance has resulted in the CDC placing

A. baumannii on its urgent threats list [

10]. The increase in antibiotic resistant strains and decrease in effectiveness of existing antibiotics raises the need for alternative antimicrobials.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are one such alternative to antibiotics to combat multidrug resistant bacterial infections. AMPs encoded by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), are known as bacteriocins and are used by the producing strain to defend against niche-competing bacteria [

11]. While there have been numerous reports of antimicrobial activity from LAB cell-free cultures (isolated from fermented foods) against Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, the identity of the compound(s) responsible for said activity has been determined in only a handful of examples (e.g., Reuterin, Plantaricin, Helveticin, Lactacin) [

12]. AMPs are also commonly produced by eukaryotic cells and commensal bacteria and can act as a form of antagonist, especially in the gut, by preventing colonization by pathogenic bacteria like

A. baumannii and

P. aeruginosa [

13]. While hundreds of AMPs with antagonistic properties toward

A. baumannii have been discovered, the vast majority of them are not derived from microbial sources [

14]. Recent work has described anti-

A. baumannii activity from various

Lactobacillus spp [

15,

16,

17], but only one identified the molecule responsible for the antimicrobial activity [

16], which was not an AMP. Synergy between LAB conditioned media and antibiotics were effective at inhibiting the growth of MDR

A. baumannii clinical isolates [

15].

Here we aim to investigate the tools employed by commensal bacteria, particularly those within the former Lactobacillus genus, in hopes of discovering novel antimicrobials for inhibition of A. baumannii planktonic growth and biofilms. Other ESKAPE pathogens and skin commensals were tested to determine the range of organisms that LAB cell-free conditioned media has an antimicrobial effect against. Cell-free conditioned media from thirteen human LAB isolates were tested for the ability to prevent biofilm formation on polystyrene cell culture plates. While eleven of these isolates significantly prevented biofilm formation (P ≤ 0.05), five isolates with P ≤ 0.0001 were chosen for further testing, which included disruption of pre-formed A. baumannii biofilms and inhibition of planktonic growth of ESKAPE pathogen isolates. Conditioned media from all five isolates were able to disrupt pre-formed A. baumannii biofilms, and inhibited planktonic growth of all ESKAPE pathogens, with best activity on Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens. Antimicrobials produced by L. hilgardii had the least impact on growth of the Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium commensal isolates tested; therefore, was chosen for further characterization of the antimicrobial activity. The planktonic growth-inhibiting activity was determined to be thermostable up to 100oC and between 3-10 KDa in size, suggesting bacteriocin activity. BLASTP analysis of L. hilgardii predicted proteins against a custom non-redundant comprehensive antimicrobial peptide database, CAMPdb and a novel HMM that recognizes the class II bacteriocin diglycine leader sequence identified four potential AMPs. The four predicted AMPs were chemically synthesized and tested for the ability to inhibit A. baumannii planktonic growth, the ability to disrupt pre-formed biofilms and the ability to form a zone of clearing on a lawn of A. baumannii. Two peptides, when combined, were sufficient to inhibit A. baumannii planktonic growth and form a zone of clearing when spotted on an A. baumannii lawn but had no activity on pre-formed biofilms. Planktonic growth inhibition was observed for the two-peptide cocktail on all ESKAPE pathogens tested except on P. aeruginosa. Synergy between sub-MIC levels of meropenem and the MIC level of the 2-peptide cocktail significantly disrupted mature A. baumannii biofilms. Taken together, this report describes a new platform to discover and characterize new antimicrobial peptides from commensals against AMR bacteria.

3. Discussion

In the search to combat the challenging biofilm formation of antibiotic resistant bacteria such as

A. baumannii, recent research has highlighted the potential of factors derived from commensal species of bacteria to both prevent biofilm formation and disrupt existing biofilms [

16]. Conditioned media from various LAB species, including

L. hilgardii,

L. buchneri,

L. ruminis,

L. fermentum, and

L. antri, demonstrated significant efficacy in both preventing the formation of and disrupting pre-formed

A. baumannii biofilms. Further testing against ESKAPE pathogens and skin commensals revealed that conditioned media from these LAB could inhibit the growth of all ESKAPE pathogens, with variable effects on skin commensals.

L. hilgardii conditioned media was particularly noted for its ability to inhibit

A. baumannii planktonic growth without complete inhibition of skin commensal growth. A cutting edge bioinformatic approach was able to predict several antimicrobial peptides partially responsible for this activity. Synthesized peptides showed significant growth inhibition of

A. baumannii and reduced growth of other ESKAPE pathogens. However, while these peptides were effective against planktonic cultures, alone, they had no impact on pre-formed biofilms. Importantly, when combined with meropenem, the peptides demonstrated synergistic effects in reducing biofilm biomass. Together, our results provide a comprehensive approach to discover and characterize new antimicrobial peptides from commensal bacteria.

Current computational tools for identifying bacterial AMPs combine rich curated databases, motif/physicochemical scanners, and increasingly powerful machine-learning models. Large, actively maintained repositories such as APD3 [

24] and CAMPR4 [

25] provide the foundational datasets and basic search/prediction utilities that many pipelines still rely on. Classical predictors and web servers like AMPA [

26] and AntiBP2 [

27] use residue-level scoring, charge/hydrophobicity filters and handcrafted sequence features to locate short antimicrobial domains in proteins and peptides, but AntiBP2 is now offline . Other bioinformatic resources, such as DBAASP [

28] and AI4AMP [

29], add species-specific activity prediction and improved physicochemical encodings, expanding from binary AMP/non-AMP calls toward estimated potency and target spectra, but either lack the ability to search whole genomes for AMPs or return too many predicted AMPs. Recently, deep-learning approaches such as iAMP-Attenpred [

30], deepAMPNet [

31] and deepAMP [

32] have improved predictive performance and enabled design of novel candidates; however, with dependence on high-quality labeled data and requirement of experimental MIC validation. Taken together, the current approaches focus on identification of candidate bacterial AMPs, yet the best approach should aim to use targeted

in silico methods coupled with wet-lab testing to improve prediction accuracy, species coverage, and reduce false-positive rates [

33].

Despite the availability of AMP prediction tools, we were unsuccessful using them to identify candidate AMPs for several reasons. As with many boutique online bioinformatic prediction resources, they fail to be maintained and are no longer available; therefore, we could not test all of them. The two that we tested (CAMPR4 and AI4AMP) on the proteome of

L. hilgardii returned too many predicted AMPs to reasonably test. To be able to fine toon peptide search parameters and have unprocessed (i.e., prepeptide or preform) sequences complete with leader sequences, we decided to download as many AMP databases that were still publicly available at the time of this project as well as published AMPs with activity on

A. baumannii, many of which were lacking from the public AMP databases. These peptide sequences were merged into a single BLAST-formatted non-redundant

comprehensive

anti

microbial

peptide

data

base, CAMPdb. We also downloaded 179 AMP HMMs from the CAMPR4 website, which returned 5 matches using HMMSCAN. However, 4 of them were greater than 100 aa and the one that was less than 100 aa had an E-value of 0.025 and did not have a diglycine leader motif. Using our CAMPdb, we extracted and aligned 128 diglycine-containing class IIa, Ib and IId leader peptide sequences to build our new HMM, which outperformed existing HMMs for identifying class II bacteriocin leader peptide sequences from the genomes of LAB. Bagel4 [

34], a web server and standalone set of PERL scripts that identifies ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides and bacteriocins, also contains 51 Pfam HMMs of bacteriocins and associated proteins (

https://github.com/annejong/BAGEL4/tree/main/db_hmm). A search of these HMMs against the

L. hilgardii genome resulted in 2 HMMs (PF10439 and PF03047) with matching only peptides 1, 3 and 5 above the inclusion threshold. Despite having diglycine leader sequences and folding into alpha helices, peptides 2 and 4 were not identified by any of the 51 Pfams used by Bagel4 but JCVIFAM_00001 was able to. Further work will be needed to determine if peptides 2, 4 and 5 have any activity towards Gram-negative or Gram-postitive bacteria.

The AMPs identified, chemically synthetized and tested in this study have characteristics typically found in class II bacteriocins, such as short length (<60 amino acids), heat-stability, net positive charge and the presence of a double or di-glycine leader sequence [

22]. Because none of the peptides tested in this study were active alone and because they lack the signature “YGNGV” motif, they are likely not class IIa bacteriocins. However, since antimicrobial activity was only achieved with a pair of diglycine leader-containing and positively charged small peptides, peptides 1 and 3 match the description of class IIb bacteriocins like PlnE/F and PlnJ/K. Both PlnE/F and PlnJ/K are both two-peptide bacteriocins that consist of equal molar ratios of α (E and J) and β (F and K) amphiphilic alpha-helical peptide subunits that interact via “GxxxG” motifs to form the active bacteriocin that spans the target cell membrane, resulting in increased permeability to small molecules and ultimately cell death [

22,

35,

36].

L. hilgardii mature peptides 1 and 3 have sequence lengths of 25 and 35 aa in length, which corresponds to a size of 3.2 and 4.0 KDa, respectively. They are also thermostable up to 100

oC and have net positive charges of 6 and 5, respectively, all properties found in class II bacteriocins. Additionally, they both have predicted GxxxG-like (i.e., GxxxG/A/S/T) motifs, which promote binding of transmembrane domains of integral membrane proteins [

37] and class IIb bacteriocins [

35]. Peptide 1 has the sequence “GfkkT” near the C-terminus of the mature peptide while peptide 3 has the sequence “GfnkG” also near the C-terminus (

Table 1). Future work is needed to characterize the interactions of these two peptides and the role of these sequence motifs in this interaction.

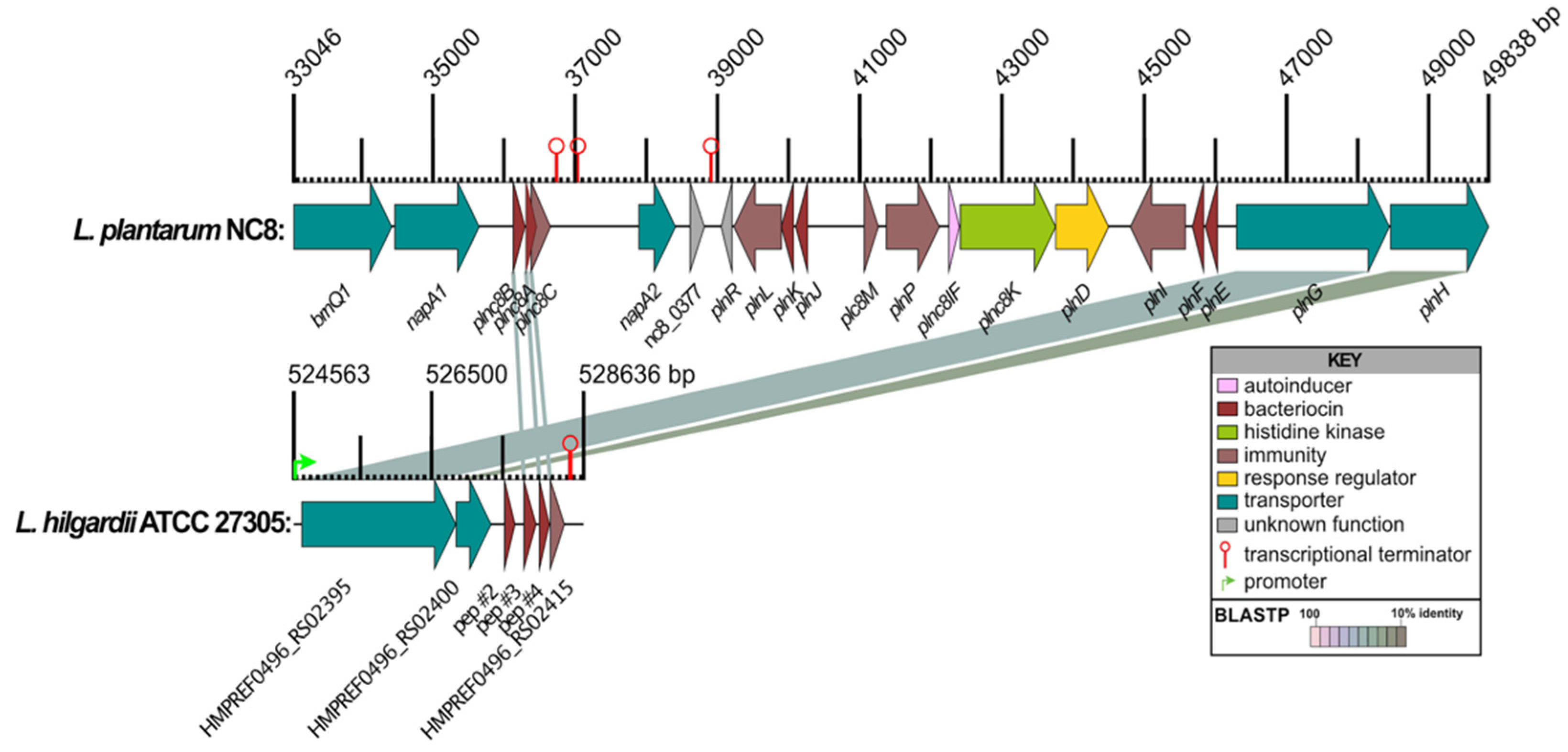

Unlike typical class IIb two-peptide bacteriocins, whose gene encoding the prepeptides are next to each other, the genes coding for the pre-peptides of 1 and 3 are located in different operons ~ 70 Kbp apart [

35]. In

L. hilgardii ATCC 27305, the genes encoding prepeptides of 2, 3 and 4 are next to each other in a single operon along with predicted immunity and transport proteins (

Figure 4). Peptide 4 has BLASTP similarity to Plantaricin NC8α and Peptide 3 has similarity to Plantaricin NC8β while peptides 1 and 2 have no discernable matches to and two-peptide bacteriocins (

Table 1). It could be that α and β subunits from different operons can mix and match as a mechanism to target different bacteria. Understanding the mode of action and the relationship between interchangeability of α and β subunits and host range will require further investigation.

Challenges in disrupting biofilms compared to planktonic cells have been a hallmark of the war on AMR pathogens. The reduced efficacy of AMPs against bacterial biofilms is primarily due to the protective properties of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix and adaptive resistance mechanisms within biofilm communities. The EPS matrix is mainly composed of polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA, and lipids, acts as a physical and chemical barrier that can sequester or neutralize AMPs, reducing their ability to reach target cells [

38,

39]. Positively charged EPS matrix components such as the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) in

S. epidermidis and

S. aureus, can electrostatically repel cationic AMPs such as LL-37, human β-defensin and sequester both cationic and anionic AMPs, thereby restricting their access to bacterial cells under the EPS [

40,

41]. Another way biofilms can reduce AMP activity is the upregulation of countermeasures such as proteases. These can either degrade or modify the surface charge of AMPs reducing their ability to bind to bacteria and lyse them [

42]. We hypothesize that similar mechanisms are employed by

A. baumannii to prevent AMP activity and that disruption of the matrix by their combination with antibiotics may provide an efficient way to counter such mechanisms.

The multifactorial defense mechanisms used by bacteria to diminish the bactericidal potential of AMPs in biofilm contexts compared to planktonic states is of great importance to the field. Future studies should target the identification of new peptides that enhance the activity of decolonizing agents and antibiotic treatment. In addition, current studies targeting the use of bacteriophages (or bacteriophage-derived polysaccharide depolymerases) that can travel across or destroy the EPS matrix may further the synergy of peptides and antibiotics [

43].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Culturing Conditions

Acinetobacter baumannii ABUH773 was employed as the model organism for these experiments.

A. baumannii ABUH773 is a CRAb global clone 2 (GC2) clade F clinical isolate from 2015 [

44,

45].

A. baumannii MRSN 7339 is a MDR CRAb global clone 1 (GC1) clinical isolate from 2004 [

46]

A. baumannii was always grown at 37°, 5% CO2 and was cultivated in Brain Heart Infusion broth for 18 hr. LAB were grown on and in MRS agar and broth. Thirteen human commensal LAB isolates were screened for their antimicrobial properties in the prevention of

A. baumannii biofilm production (

Table S1). All were isolated and sequenced by the human microbiome project (HMP) [

47] and stock cultures were obtained from BEI resources. LAB were grown on MRS media aerobically at 37°C, 5% CO

2 with the exception of

Limosilactobacillus antri DSM 16041 and

Ligilactobacillus ruminus ATCC 25644, which were grown at 37°C in a Coy anaerobic chamber filled with a combination of N

2 and standard mixed gasses (CO

2-H

2-N

2). Non-LAB commensal isolates were grown on BHI at 37°C, 5% CO

2. Supernatants of all commensals were prepared as follows; 10 mL broth cultures were seeded with 100 μL from starter cultures grown for 18 hr at 37°. Liquid cultures were then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was saved and filtered through a 0.22 μm cellulose membrane filters (Corning, New York, NY, USA). Before centrifugation, 200 μL was saved and serially diluted, then plated to determine CFU/mL. ESKAPE pathogen strains included

Enterococcus faecium DO,

Staphylococcus aureus SA113,

Klebsiella pneumoniae VA367 [

48],

Acinetobacter baumannii ABUH773 [

44,

45],

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 [

49] and

Enterobacter hormaechei Eh1 [

50] while human skin commensal bacteria tested included

Staphylococcus epidermidis SK135,

Staphylococcus hominis SK119 and

Corynebacterium jeikeium ATCC 43734 (

Table S1). ESKAPE and commensal bacteria were grown in BHI at 37

oC except that

C. jeikeium was supplemented with 1% (vol/vol) Tween-80 (Fisher).

4.2. Planktonic Growth Assays

24-hour growth rate experiments were conducted in 96 well plates. Overnight broth cultures were diluted 1:100 with BHI or BHI supplemented with 1% Tween-80, providing bacterial cells in early log phase for the growth curve assays. The diluted bacterial cultures were mixed 50:50 and co-incubated with the cell-free LAB supernatants, along with MRS as a control in a total volume of 200 μL. The 96-well plates were incubated at 37°C in a SpectraMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA), with optical density measured at 600 nm every 15 minutes over 24 hours.

4.3. Biofilm Assays

Biofilm disruption and prevention assays were largely conducted in the same manner, with some exceptions. In biofilm prevention assays, A. baumannii overnight cultures were diluted 1:100, and inoculated in well plates with cell-free supernatant (experimental) and MRS broth (negative control) to incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 statically overnight. The next day, contents of wells were removed and A baumannii biofilms were fixed with 100% methanol (incubated at 4°C for 10 min), then stained with filtered 0.1% crystal violet (incubated at 4° for 10 min), and finally washed with PBS. Ethanol was added to the wells and absorbance at 490 nm was measured with a Tecan microplate reader (Tecan, Raleigh, NC, USA). Slightly different, biofilm disruption assays were conducted over the course of three days. A. baumannii overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 and inoculated in well plates with MRS broth to incubate at 37°, 5% CO2 statically overnight. The next day contents were gently removed from wells and fresh BHI and MRS were applied to each well. On the third day contents were removed and supernatants were applied to experimental wells, along with fresh BHI, and MRS was applied to control wells. Plates were incubated overnight, and the next day biofilm biomass were measured as described previously (fixing, staining, Tecan). Additional biofilm assays were performed using a combination of peptides, Polymyxin B, 70% Ethanol and LB media at pH 5.

4.4. Planktonic and Biofilm Viability

Planktonic and biofilm viability tests were completed following biofilm disruption assays. On the final day of the assay, in place of fixing and staining, 200 μL of the contents of the wells were removed and serially diluted. 10 μL were plated on BHI to determine CFU/mL counts of the planktonic cells present in the experimental and control wells. For biofilm viability, a sterile tip was employed to scrap the biofilms, then inoculate 200 μL of sterile PBS. This was then serially diluted and 10 μL were plated on BHI to determine CFU/mL counts. All BHI plates were incubated overnight at 37°, 5% CO2 and isolated colonies were counted the following day.

4.5. Fractionation Assays

Cell-free supernatants were fractionated at four different sizes, including 100 kDa, 30 kDa, 10 kDa, and 3 kDa. Amicon Ultra-centrifugal filters (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) were employed for fractionated supernatants. Cell-free Lactobacillus supernatants, as well as MRS for controls, were loaded into Ultra-Centrifugal filters and spun at 4000 RPM in a swinging bucket centrifuge, 20 minutes for 3 kDa and 10 minutes for 100 kDa, 30 kDa and 10 kDa. Fractionated supernatants were then employed to conduct both 24-hour growth assays and biofilm disruption assays as described above.

4.6. Bioinformatics

Protein-coding sequences (CDSs) from the genome of

Lentilactobacillus hilgardii subsp.

gravesensis ATCC 27305 HMP ID 496 (GenBank: NZ_GG669709, Biosample: SAMN00001468) were searched for matches to a custom comprehensive and non-redundant antimicrobial peptide database using NCBI BLAST 2.11.0+ [

51]. The database was constructed using amino acid sequences from 5 antimicrobial peptide database resources: BACTIBASE [

52,

53], APD3 [

24], DRAMP 3.0 [

54], dbAMP 2.0 [

55], and AMPDB v1 [

19], and 179 peptide sequences manually entered from a review article on

Acinetobacter-targeting AMPs [

14]. A combined total of 86,662 amino acid sequences were made non-redundant into a database of 32,865 by clustering with cd-hit [

56] version 4.8.1 using default settings, which cluster amino acids with a sequence identity threshold of 0.9. Peptide sequences < 100 aa were retained, resulting in a final database of 12,616 antimicrobial peptide reference sequences, which will be referred to as the

comprehensive

anti

microbial

peptide

data

base, CAMPdb. This database was used as the subject in BLASTP searches against 2,892 query CDSs from

L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 with an E-value cut-off of 0.01. The resulting top matches were filtered to remove the strings “lysozome” and “Helix-turn-helix” from the database matches and amino acid sequences > 99 aa.

To identify class II bacteriocin diglycine leader sequences within the genome of

L. hilgardii ATCC 27305, a collection of full-length prototypical class II diglycine leader-containing peptides was obtained from literature [

22] and the above-mentioned AMP databases that labeled the class II bacteriocins and contain full-length peptide sequences [

19,

54]. The leader sequences were extracted from 128 non-redundant class IIa,b,d peptides and aligned with M-COFFEE using the T-COFFEE Multiple Sequence Alignment Server (

https://tcoffee.crg.eu/) [

57]. The FASTA alignment (File S1) was converted to Stockholm format using msaconverter V0.0.3 (

https://github.com/linzhi2013/msaconverter) (command line: msaconverter -i alignment.fasta -o alignment.sto -p fasta -q stockholm -t protein), which uses Biopython [

58]. An HMM profile model was generated (JCVIFAM_00001.hmm, File S2) using the hmmbuild program (command line: hmmbuild --amino -o hmmbuild_summary_JCVIFAM_00001 JCVIFAM_00001.hmm alignment.sto) from HMMER 3.3.2 [

59]. Protein sequences from the genome of

L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 were searched using this novel HMM with the hmmsearch program (command line: hmmsearch -o JCVIFAM_00001.out --tblout JCVIFAM_00001_table.out --max JCVIFAM_00001.hmm SAMN00001468.pep) also from HMMER 3.3.2. Matches to this HMM that were above the software-determined inclusion threshold cut-off were considered to be positive matches. This HMM was validated by searching against the full-length class IIa,b,d peptide database used in the construction of the HMM and also searching the protein sequences derived from the

L. plantarum pln locus of strains C11 and NC8, GenBank accession numbers X94434 and AF522077, respectively. This HMM was able to match 139 out of 142 peptides from the seed alignment and the known AMPs

plnA,

plnEF,

plnJK and

plnN from

L. plantarum C11 and

plnc8IF,

plnEF,

plnJK and

plnc8AB from

L. plantarum NC8.

A linear genetic map illustration comparing a predicted AMP-containing region from the genome of

L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 with the characterized

pln operon of

L. plantarum NC8 from GenBank accession AGRI01000003 was generated using LinearDisplay.pl (

https://github.com/JCVenterInstitute/LinearDisplay) (command line: LinearDisplay.pl -A frag.file -F gene_att.file -P pairs.file -y -nt > linear.fig) [

60]. The pairs.file was derived from blastp 2.11.0+ all-vs-all searches of the illustrated protein sequences (command line: blastp -query pep.file -db pep.file -out blastp.out -evalue 0.01 -outfmt 6 -num_threads 4).

4.7. Inhibition of Planktonic Growth by Chemically-Synthesized Peptides

The four bioinformatically-predicted peptide sequences were chemically synthesized by LifeTein LLC to a minimum of 85% purity at a quantity of 4 mg each. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) experiments were conducted first, determining the threshold of these peptides and their hypothesized antimicrobial abilities. During MIC assays, all four peptides were used in conjunction, mixed at the same volume and co-incubated with A baumannii in 24-hour assays (exactly as described above). Volume of peptides for MIC assays shown in this paper started at 2 µg and went down to 1 µg, decreasing by 0.25 µg. Initial MIC experiments not shown began at 200 µg and decreased tenfold to 2 µg. After MIC assays, synergy tests were made with single omission, double omission and triple omission experiments (SOE, DOE and TOE respectively).

4.8. Synergy Between Peptides and Meropenem

The 24-hour planktonic growth curve assay was used as described above. An overnight broth culture of A. baumannii MRSN 7339 was diluted 1:100 in 100 μl BHI supplemented with meropenem dilutions in 96-well plates. Five concentrations of meropenem from 100 - 19.75 μg/ml were tested. Water or water containing 2 μg of each peptides #1 and #3 were added to bring the culture up to 200 μl total volume.

4.9. Spot-on-Lawn Zone of Inhibition Assays

Fifty microliters of an overnight culture of A. baumannii ABUH773 was added to 3.5 mL of molten (50oC) and poured onto a warm BHI bottom agar plate and allowed to cool before spotting peptides. A 1:1 cocktail of peptides #1 and #3 was made at a concentration of 5 μg/μL and 1 μg/μL in water. Three different amounts of the peptide cocktail were spotted onto bacterial lawns at amounts of 10 μg and 50 μg in 10 μL and 100 μg in 20 μL, allowed to dry and incubated at 37oC for 5 h.

4.10. Cytotoxicity Assay

The adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cell line A549 was used. A549 cell line was purchased from ATCC. Cell cultures were maintained in sterile filtered Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin at 37ºC with 5% CO2. For the LDH cytotoxicity assay, cells were seeded into half of a 96-well flat bottom tissue culture treated plate at 4 x 104 cells per well in DMEM. After overnight incubation (~18 h) at 37ºC with 5% CO2, the DMEM culturing media was aspirated off and was replaced with RPMI 1640 containing 2% fetal bovine serum. At this time, synthesized peptides #1 and #3 were added to the experimental wells at 3 set concentrations. A peptide master mix was prepared to 1 µg (peptide)/ 1 µl with sterile molecular grade water. This master mix was added to the experimental wells at 10 µg/ml, 20 µg/ml, and 30 µg/ml concentrations. Each well was supplemented with water as needed to reach a final volume of 200 µl. After addition of the peptide mixture, the plate was incubated at 37ºC with 5% CO2 for 24 hours. LDH activity was measured using a CyQUANT LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Invitrogen). Assay was conducted following manufacturer’s protocol with few adjustments. Maximum LDH activity controls wells were treated with 20 µl of Lysis Buffer. Prior to step 7, the plate was centrifuged at 400 x g for 5 minutes at room temperature. Experimental results were obtained by Tecan measurement of the assay plate at 490 nm and 680 nm. Data was analyzed and was standardized using Microsoft Excel and Prism. This experiment was repeated three times.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise noted, all experiments are composed of a minimum of 3 biological replicates, with ≥3 technical replicates each. Statistical comparisons were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8 (La Jolla, CA). Comparisons between two cohorts at a single time point are calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. Comparisons between groups of >2 cohorts or groups given multiple treatments were calculated by ANOVA with Tukey’s (one-way) or Sidak’s (two-way) post-test or by Kruskal-Wallis H test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-test, as determined by the normality of data groups. Repeated measures are accounted for whenever applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; methodology, A.A., K.L., A.M.T., N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; software, D.E.F.; validation, A.A., A.B.A., A.P.D., N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; formal analysis, A.A., L.V., A.B.A., K.L., A.P.D., N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; investigation, A.A., L.V., A.B.A., K.L., A.P.D., N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; resources, A.A., K.L., A.M.T., and D.E.F.; data curation, A.A., L.V., A.B.A., K.L., A.P.D., N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., L.V., N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; writing—review and editing, N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; visualization, A.A., L.V., A.B.A., K.L., A.P.D., N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; supervision, N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; project administration, N.G.-J. and D.E.F.; funding acquisition, D.E.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

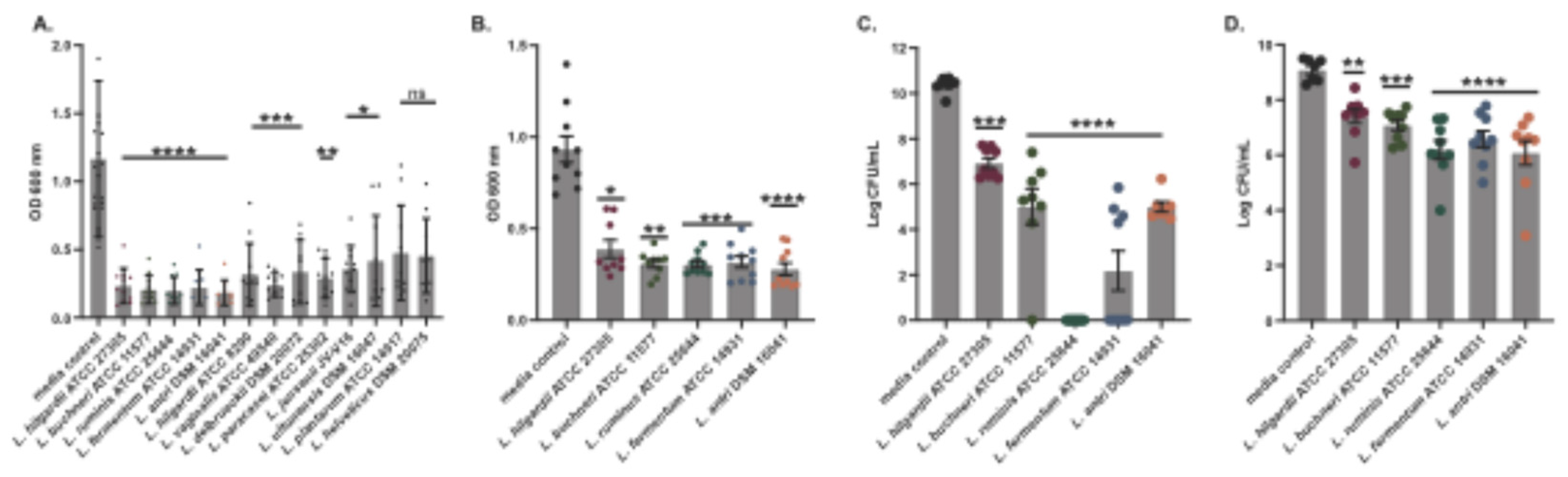

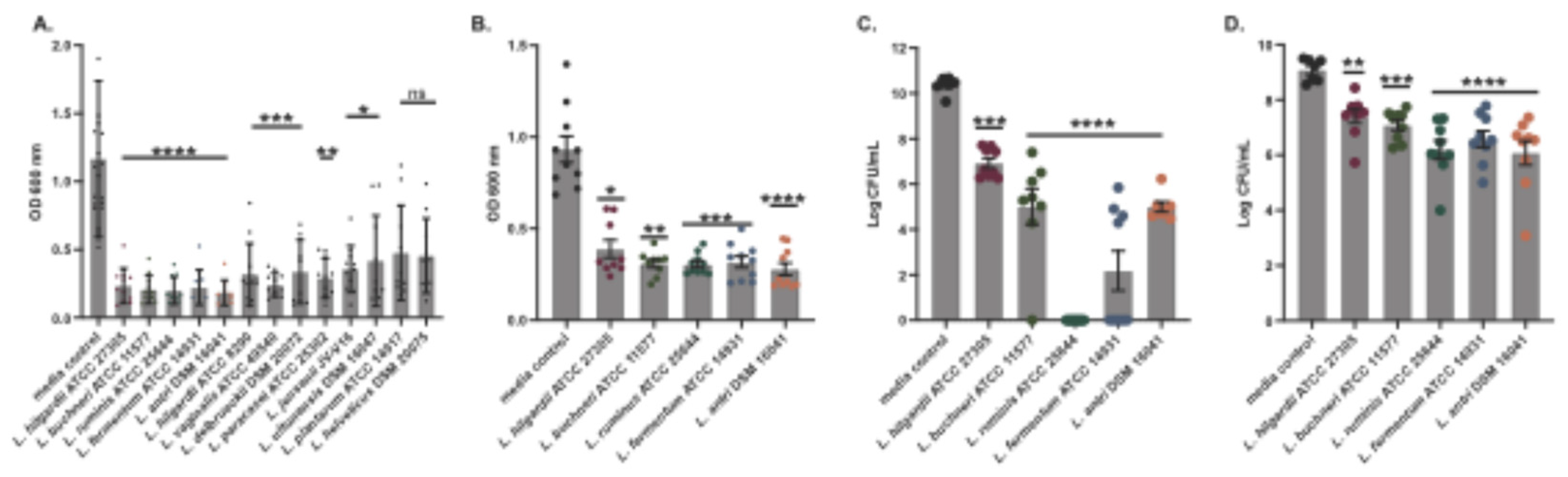

Figure 1.

LAB conditioned media impedes A. baumannii biofilms and viability. Thirteen isolates from 12 different human commensal LAB species were tested against A. baumannii ABUH773 in biofilm assays, where A. baumannii and cell-free LAB conditioned media was co-incubated statically at 37°C. Biofilm integrity was determined after 24 hours of coincubation, and then the staining of biofilms using 0.1% crystal violet stain (A). Assays to measure disruption of pre-formed A. baumannii biofilms by the six most significant biofilm-inhibiting supernatants (boldface, panel A) were conducted over the course of four days, with the original seeding, the refreshing of media the following day, and the introduction of cell-free LAB conditioned media on the third day. The fourth day involved the fixing, staining, and washing of biofilms. Biofilms were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (B). Bacteria in supernatant viability was determined by CFU/mL measurements (C) as well as that bound to the plate (biofilm) viability (D). Viability data are reported as the Log CFU/mL of recovered bacteria. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to determine significance between MRS control and Lactobacillus supernatant experimental conditions in the 24-hour biofilm assay. Experiments were done in triplicate with error bars representing standard deviations. For the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests, asterisks denote the level of significance observed: ns, not significant; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 1.

LAB conditioned media impedes A. baumannii biofilms and viability. Thirteen isolates from 12 different human commensal LAB species were tested against A. baumannii ABUH773 in biofilm assays, where A. baumannii and cell-free LAB conditioned media was co-incubated statically at 37°C. Biofilm integrity was determined after 24 hours of coincubation, and then the staining of biofilms using 0.1% crystal violet stain (A). Assays to measure disruption of pre-formed A. baumannii biofilms by the six most significant biofilm-inhibiting supernatants (boldface, panel A) were conducted over the course of four days, with the original seeding, the refreshing of media the following day, and the introduction of cell-free LAB conditioned media on the third day. The fourth day involved the fixing, staining, and washing of biofilms. Biofilms were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (B). Bacteria in supernatant viability was determined by CFU/mL measurements (C) as well as that bound to the plate (biofilm) viability (D). Viability data are reported as the Log CFU/mL of recovered bacteria. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to determine significance between MRS control and Lactobacillus supernatant experimental conditions in the 24-hour biofilm assay. Experiments were done in triplicate with error bars representing standard deviations. For the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests, asterisks denote the level of significance observed: ns, not significant; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

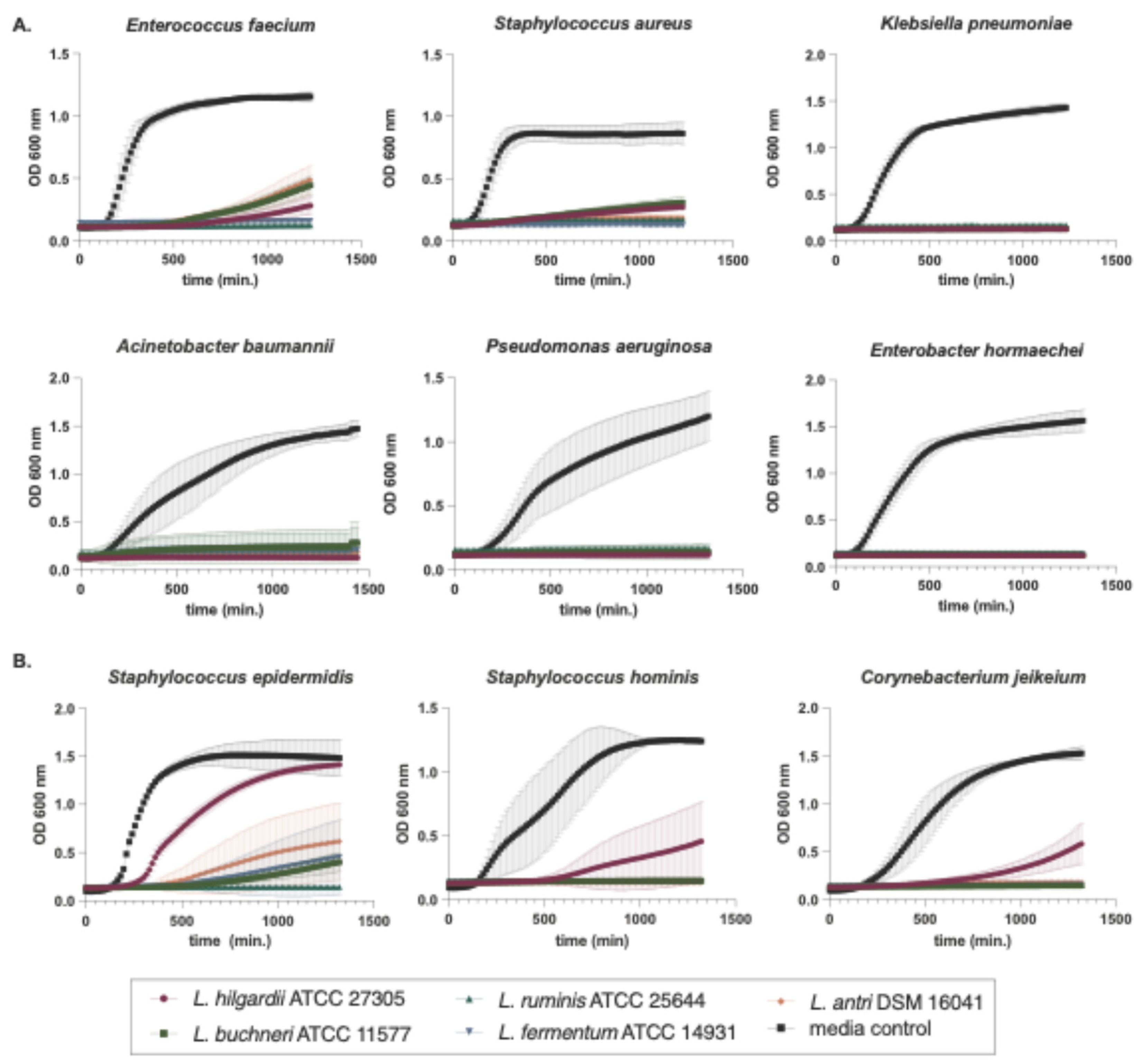

Figure 2.

The effect of LAB conditioned media on planktonic growth of ESKAPE pathogen and skin commensal organisms. Bacterial growth in liquid media was measured by optical density at 600 nm wavelength for 24 h. An equal volume of cell-free supernatants from five LAB or media control were tested for inhibition of growth of six representative ESKAPE pathogen isolates (A) and three representative skin commensal isolates (B). Colors indicate different LAB supernatants or media control (see Key). Error bars denote standard deviation about the mean. Data points were derived from the average of at least six replicate cultures.

Figure 2.

The effect of LAB conditioned media on planktonic growth of ESKAPE pathogen and skin commensal organisms. Bacterial growth in liquid media was measured by optical density at 600 nm wavelength for 24 h. An equal volume of cell-free supernatants from five LAB or media control were tested for inhibition of growth of six representative ESKAPE pathogen isolates (A) and three representative skin commensal isolates (B). Colors indicate different LAB supernatants or media control (see Key). Error bars denote standard deviation about the mean. Data points were derived from the average of at least six replicate cultures.

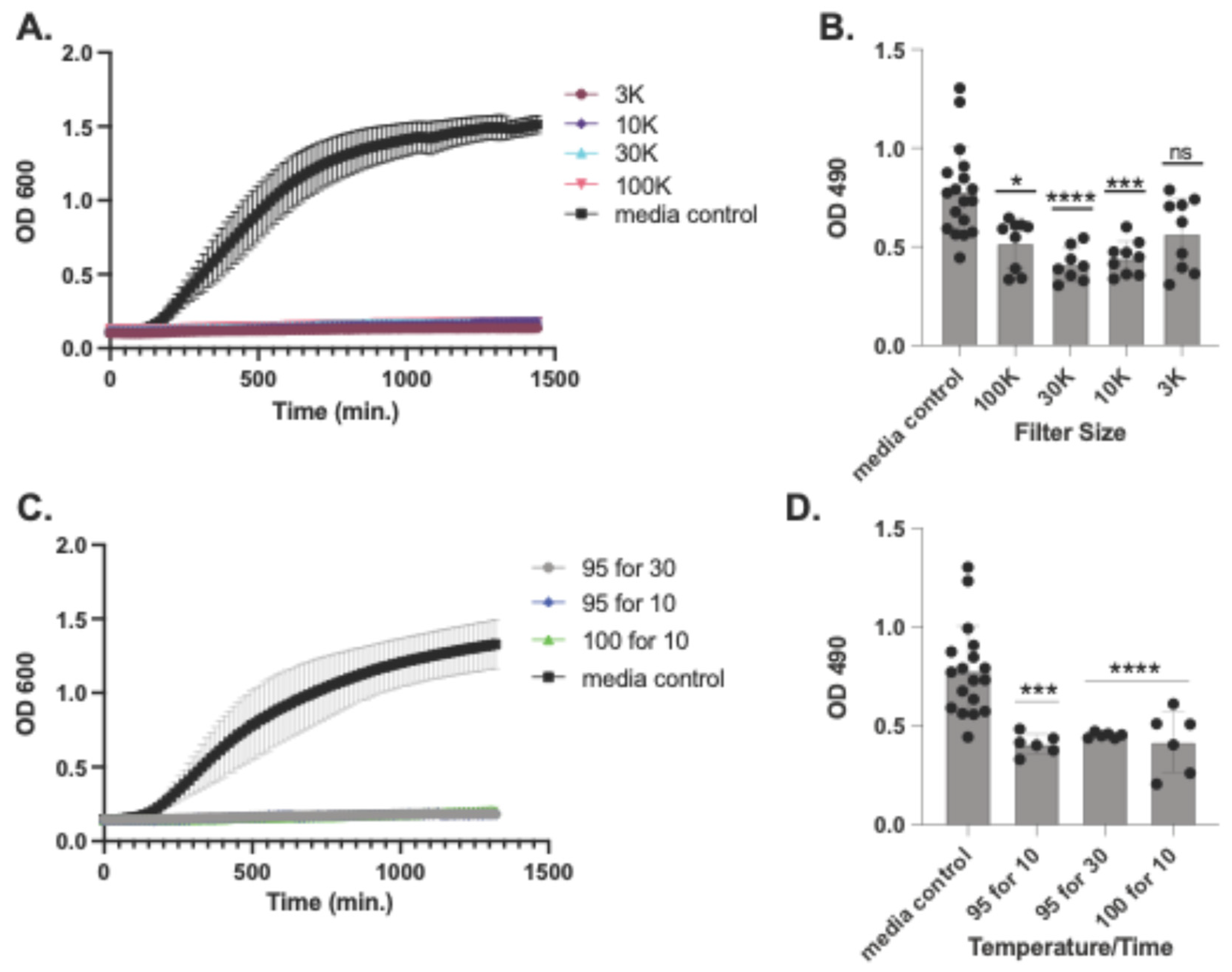

Figure 3.

Inhibition by size-fractionated Lentilactobacillus hilgardii supernatants. L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 conditioned media was fractionated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters with a molecular weight cut-off of 100 kDa, 30 KDa, 10 KDa or 3 KDa. Filtered conditioned media was co-incubated with A. baumannii in liquid BHI media for 24h (A) or disperse pre-form biofilms (B). L hilgardii ATCC 27305 conditioned media was also boiled, at 95°C for 10 and 30 minutes and 100°C for 10 minutes and tested for inhibition of planktonic growth (C) and dispersal of pre-formed biofilms (D). MRS is the media control. Experiments were done in triplicate with error bars representing standard deviations. For the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests, asterisks denote the level of significance observed: ns, not significant; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Inhibition by size-fractionated Lentilactobacillus hilgardii supernatants. L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 conditioned media was fractionated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters with a molecular weight cut-off of 100 kDa, 30 KDa, 10 KDa or 3 KDa. Filtered conditioned media was co-incubated with A. baumannii in liquid BHI media for 24h (A) or disperse pre-form biofilms (B). L hilgardii ATCC 27305 conditioned media was also boiled, at 95°C for 10 and 30 minutes and 100°C for 10 minutes and tested for inhibition of planktonic growth (C) and dispersal of pre-formed biofilms (D). MRS is the media control. Experiments were done in triplicate with error bars representing standard deviations. For the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests, asterisks denote the level of significance observed: ns, not significant; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Comparison of predicted class II bacteriocins and surrounding genes from L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 to the L. plantarum NC8 pln operon. The linear map of protein-coding sequences (CDSs) is based on nucleotide sequences of the L. plantarum NC8 pln region (GenBank: AGRI01000003.1) and predicted CDSs from a region including predicted AMPs #2-4 in the HMP-sequenced genome of L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 (GenBank: NZ_GG669604). CDSs are labeled by gene symbol (L. plantarum) and by locus identifier or peptide designation (L. hilgardii) and colored by functional role categories of L. plantarum CDSs as noted in the boxed key. BLASTP matches between CDSs are colored by protein percent identity (see key). Green arrows and red hairpin structures indicate predicted promoters and transcriptional terminators, respectively. Numbers above major tick marks denote nucleotide coordinates in their respective GenBank accessions. Promoters were only displayed for L. hilgardii.

Figure 4.

Comparison of predicted class II bacteriocins and surrounding genes from L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 to the L. plantarum NC8 pln operon. The linear map of protein-coding sequences (CDSs) is based on nucleotide sequences of the L. plantarum NC8 pln region (GenBank: AGRI01000003.1) and predicted CDSs from a region including predicted AMPs #2-4 in the HMP-sequenced genome of L. hilgardii ATCC 27305 (GenBank: NZ_GG669604). CDSs are labeled by gene symbol (L. plantarum) and by locus identifier or peptide designation (L. hilgardii) and colored by functional role categories of L. plantarum CDSs as noted in the boxed key. BLASTP matches between CDSs are colored by protein percent identity (see key). Green arrows and red hairpin structures indicate predicted promoters and transcriptional terminators, respectively. Numbers above major tick marks denote nucleotide coordinates in their respective GenBank accessions. Promoters were only displayed for L. hilgardii.

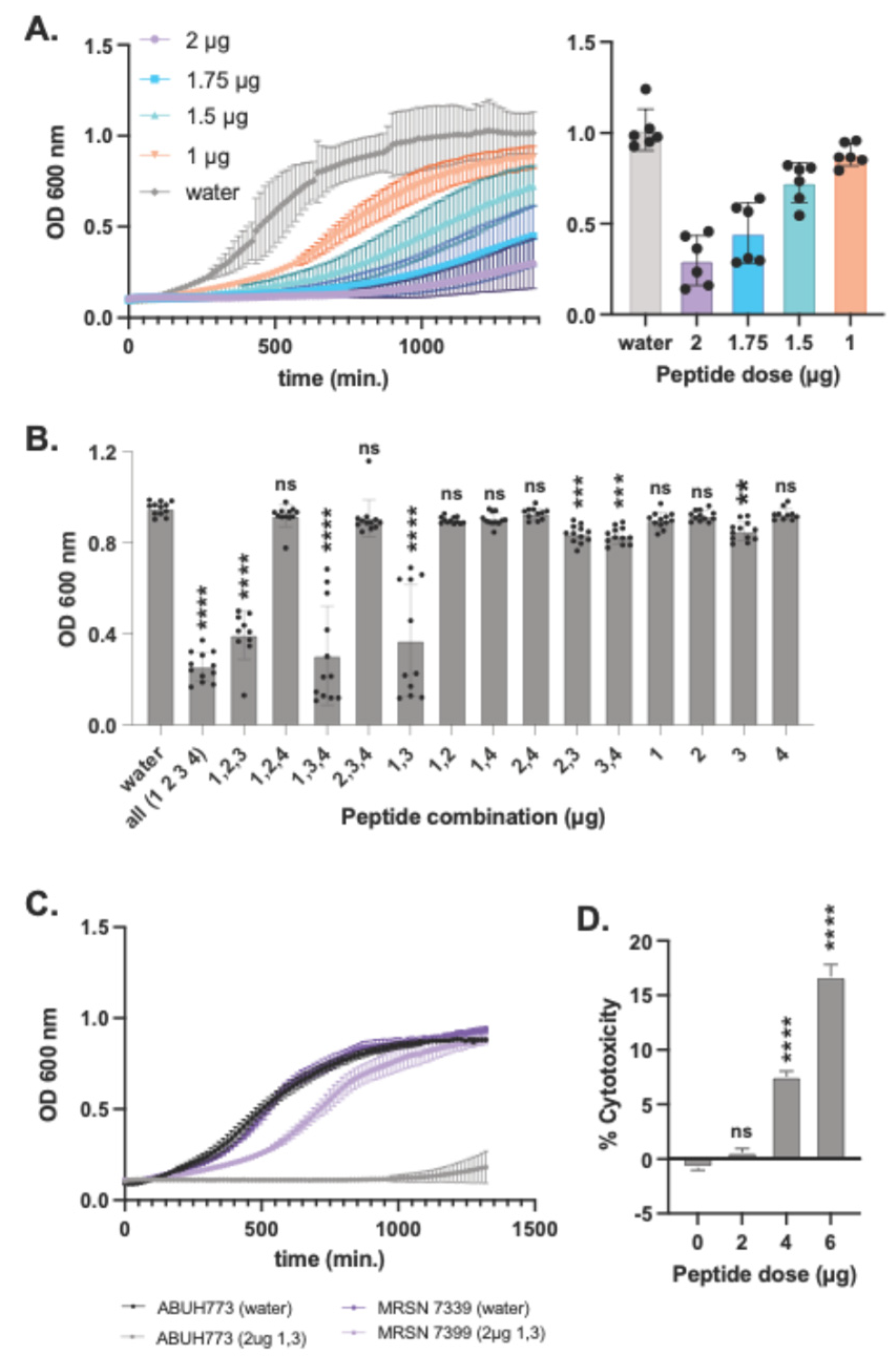

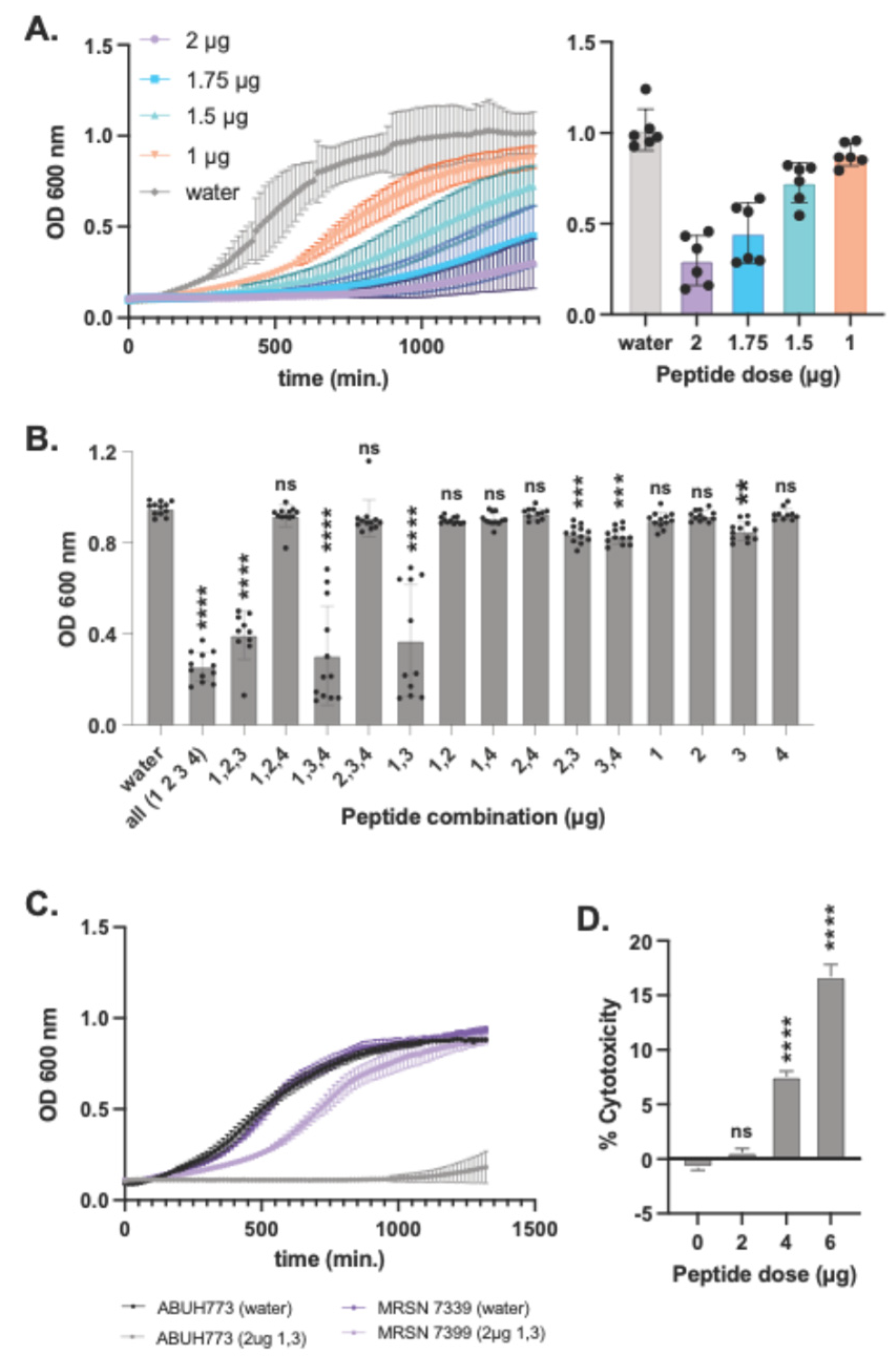

Figure 5.

Testing of synthesized predicted peptides for activity and cytotoxicity. Chemically synthesized (85% purity) predicted antimicrobial peptides derived from bioinformatic analysis of the L. hilgardii genome were tested for MICs of planktonic 24-hr growth of A. baumannii in broth cultures. All four peptides were pooled and added to 200 μl BHI media in the amounts shown in the key (A), it was found that 2 μg is the lowest amount of peptide required to strongly inhibit planktonic growth. The MIC of 2 μg (10 μg/ml) of each peptide was tested for inhibition of A. baumannii planktonic growth in the combinations noted on the X-axis (B). CRAb isolate MRSN 7339 was challenged with peptides 1 and 3 in 24-hr growth curve assays (C). A549 cells were challenged with L. hilgardii antimicrobial peptides at doses of 2, 4, and 6 μg and LDH release was assessed 4 hrs post-challenge (D). Statistical differences relative to no peptide controls were determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post-test. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, ****P≤0.0001. Error bars denote standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Testing of synthesized predicted peptides for activity and cytotoxicity. Chemically synthesized (85% purity) predicted antimicrobial peptides derived from bioinformatic analysis of the L. hilgardii genome were tested for MICs of planktonic 24-hr growth of A. baumannii in broth cultures. All four peptides were pooled and added to 200 μl BHI media in the amounts shown in the key (A), it was found that 2 μg is the lowest amount of peptide required to strongly inhibit planktonic growth. The MIC of 2 μg (10 μg/ml) of each peptide was tested for inhibition of A. baumannii planktonic growth in the combinations noted on the X-axis (B). CRAb isolate MRSN 7339 was challenged with peptides 1 and 3 in 24-hr growth curve assays (C). A549 cells were challenged with L. hilgardii antimicrobial peptides at doses of 2, 4, and 6 μg and LDH release was assessed 4 hrs post-challenge (D). Statistical differences relative to no peptide controls were determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post-test. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, ****P≤0.0001. Error bars denote standard deviation.

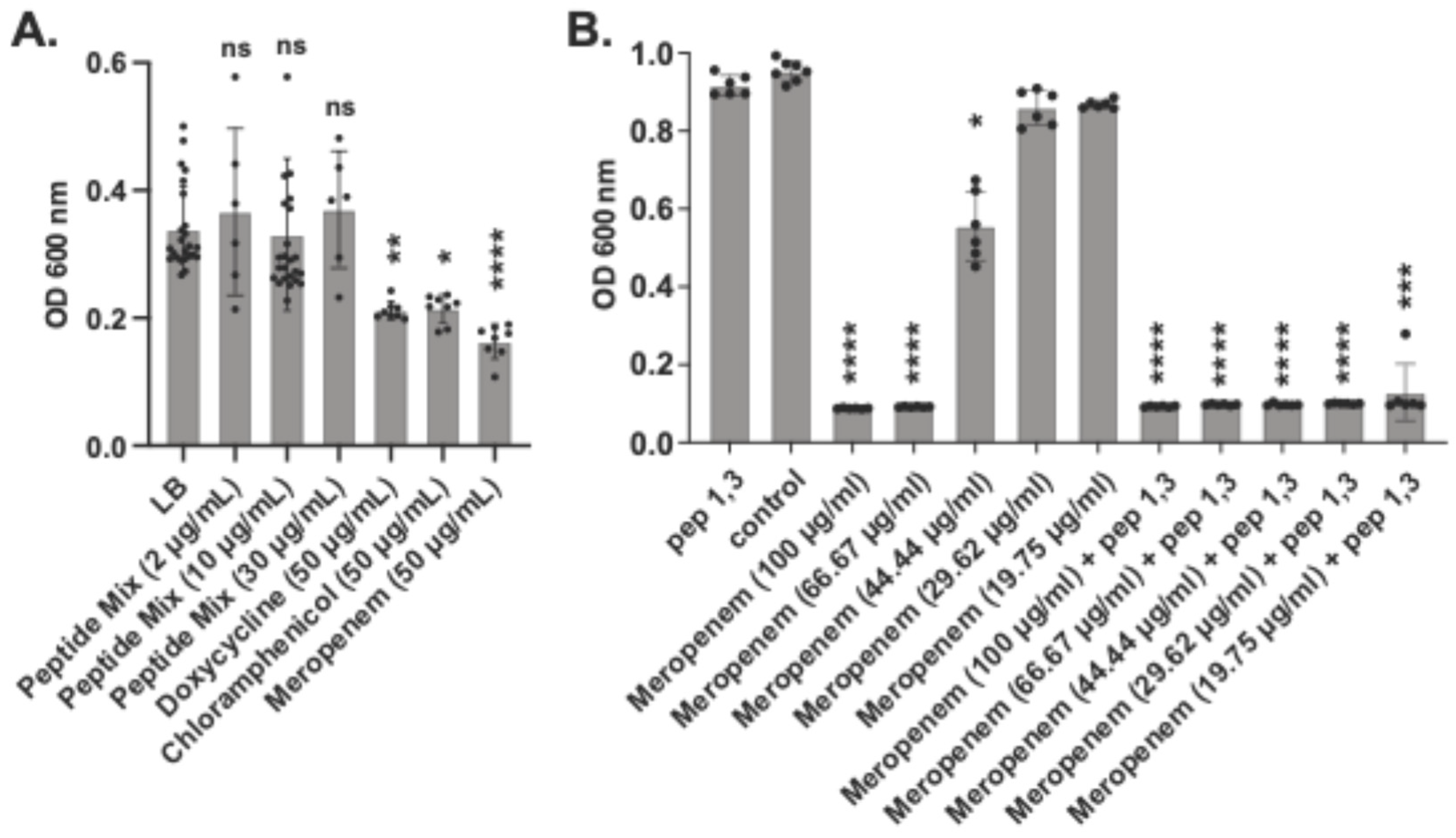

Figure 6.

AMPs synergize with antibiotics against biofilms. A. baumannii biofilm biomass after treatment with 2, 10 or 30 μg/ml of the peptide mix or 50 μg/ml of Doxycycline, Chloramphenicol or Meropenem (A). Biomass changes in biofilms treated with a combination of peptides 1 and 3 and Meropenem (B). Statistical differences relative to no peptide controls were determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post-test. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, ****P≤0.0001. Error bars denote standard deviation.

Figure 6.

AMPs synergize with antibiotics against biofilms. A. baumannii biofilm biomass after treatment with 2, 10 or 30 μg/ml of the peptide mix or 50 μg/ml of Doxycycline, Chloramphenicol or Meropenem (A). Biomass changes in biofilms treated with a combination of peptides 1 and 3 and Meropenem (B). Statistical differences relative to no peptide controls were determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post-test. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, ****P≤0.0001. Error bars denote standard deviation.

Table 1.

Predicted class II peptides containing double-glycine leader sequences.

Table 1.

Predicted class II peptides containing double-glycine leader sequences.

| Locus_id |

Peptide |

Amino acid sequence of prepeptides* |

Size (aa), (KDa), pI of prepeptide |

Size (aa), (Kda), pI of mature peptide |

Charge, hydrophobicity of mature peptide |

Best BLASTP Match |

BLASTP (id, E-val) |

Full seq HMM (E-val, score) |

Domain HMM (E-val, score) |

| |

|

|-----------leader--------|▼

|---------mature peptide--------| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HMPREF0496_RS14880 |

1 |

MFNQEKENMSQRYEELSADELSHISGG VTRYRHHEKKSWIDDFMKGFKKTFC |

52, 6.3, 7.4 |

25, 3.2, 10.2 |

6, 8.7 |

AMPDB_45803 |

100%, 3e-36 |

1.5e-4, 19.6 |

3e-4, 18.6 |

| HMPREF0496_RS15215 |

2 |

MSRNNLTILSTHKLVSVIGG QTFPIPNKPFGDRYPITIQPIIRNAYSF |

48, 5.4, 10.8 |

28, 3.3, 10.1 |

2, 10.1 |

No match |

N.A. |

3.8e-2, 12 |

4.8e-2, 11.7 |

| HMPREF0496_RS02405 |

3 |

MNKLSKFSKVTDKDLSRINGG GVWWTVITTIGKVGYSAYKDRNDIKSGFNKGFKKP |

56, 6.3, 10.6 |

35, 4.0, 10.4 |

5, 8.4 |

BAC103 (Plantaricin NC8β) |

49%, 2e-10 |

2.5e-4, 18.9 |

4.5e-4, 18.1 |

| HMPREF0496_RS02410 |

4 |

MKNIKVVKDLDLKAVTGG DWASPFWNSWGYTQGKKATWNLKHPFVRF |

47, 5.5, 10.5 |

29, 3.6, 10.5 |

4, 10.6 |

BAC089 (Plantaricin NC8α) |

47%, 1e-13 |

1.6e-3, 16.4 |

2.1e-3, 16.0 |

| HMPREF0496_RS15205 |

5 |

MKDNFKNLNSYKKLDVNSLNLIEGG

NSVASQVSDIFSRFKRAFSGSFVYKVSGRNQF |

57, 6.5, 9.4 |

32, 3.6, 11.1 |

4, 7.8 |

No match |

N.A. |

6.3e-4, 17.6 |

1.2e-3, 16.8 |