Introduction

A significant challenge to psychosocial well-being is the rising incidence of various forms of violence, particularly bullying, which negatively impacts individuals’ cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social functioning (

Braun et al., 2022;

Chen et al., 2025;

Menken et al., 2022). Bullying is defined as aggressive behavior by one or more individuals targeting a person who cannot defend themselves. Bullying is identified by three main features: repetition, intentionality, and a power imbalance between the bully and the victim. This form of bullying is primarily seen in schools and is often referred to as traditional bullying (

Olweus, 2013).

Over the past few years, the widespread use of the Internet has offered numerous opportunities for personal and professional development. However, it has also introduced significant social issues, one of which is cyberbullying. This form of bullying occurs in virtual spaces and through electronic media, such as mobile phones, emails, online games, websites, chat rooms, and social media platforms (

Kowalski, 2018). Cyberbullying can manifest in various ways, including flaming, exclusion, denigration, impersonation, harassment, outing, trickery, and cyberstalking (

Willard, 2007). For example, cyberbullying victimization involves receiving threatening or offensive messages, being the target of harmful gossip or rumors, having personal information or images exposed (also known as doxing), facing direct threats, or being deliberately excluded from online communities or social media platforms, such as Instagram or Twitter (

Lee et al., 2020).

Definition of Cyberbullying

There is no single, agreed-upon definition of cyberbullying (

Kowalski et al., 2014). According to some researchers, such as

Hinduja and Patchin (

2008), the defining features of traditional bullying also apply to cyberbullying. However, this creates challenges for researchers. For example, the indirect nature of cyberbullying makes it difficult to ascertain whether the harm was intentional or if the victim even recognized the harm (

Menesini & Nocentini, 2009). Additionally,

Menesini and Nocentini (

2009) highlight that even one instance of cyberbullying can be repeatedly shared or viewed by others. Determining power imbalances in cyberbullying is complicated due to the lack of face-to-face interaction and the indirect nature of the attacks (

Menesini & Nocentini, 2009). Moreover, Peter and Peterman (2018) emphasize that anonymity, constant availability, and a wider audience are significant features of cyberbullying that distinguish it from traditional, face-to-face bullying. Although defining cyberbullying presents certain challenges, a meta-analysis study identified four essential elements that characterize cyberbullying: (a) it involves intentional aggressive behavior that (b) is repeated, (c) occurs between parties with an imbalance of power, and (d) is perpetrated through electronic technologies (

Chun et al., 2020).

Prevalence of Cyberbullying

Numerous studies globally indicate a concerning rise in bullying across various age groups and situations. However, the prevalence of CB varies widely across studies due to differences in definitions, measurements, and samples.

Livingstone et al. (

2014) found that cyberbullying rates among adolescents aged 9 to 16 in seven European countries increased from 8% to 12%. A systematic review of 10 studies revealed cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents ranged from 6.5% to 35.4% (

Bottino et al., 2015). However, these studies predated the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent research has shown a significant surge in cyberbullying since the pandemic. For instance, content related to bullying and violence removed from Facebook increased from 2 million pieces in late 2018 to 9.5 million pieces in early 2022 (

Statista Research Department, 2022). Additionally, a study of Saudi adolescents aged 12 to 18 reported a cyberbullying prevalence rate of 42.8% (

Gohal et al., 2023). Another study among Iranian adolescents found that approximately 30% of respondents reported being cyberbullied, around 31% admitted to cyberbullying others, and about 41% had friends who were victims of cyberbullying. Notably, females and those in secondary high school were significantly more likely to engage in or experience cyberbullying (

Shariatpanahi et al., 2021).

Correlates and Predictors of Cyberbullying

In recent decades, studies have extensively explored the factors and predictors of bullying and victimization, often emphasizing socioecological contexts (

Rhee et al., 2017). Certain demographic characteristics, such as gender, are associated with a higher risk of experiencing cyberbullying. However, research findings on the influence of gender in cyberbullying have been inconsistent. Most studies have indicated that males are more likely to engage in cyberbullying perpetration compared to females (

Navarro, 2016;

Zsila et al., 2019). Contrary to these studies, other findings have been varied. For instance, one study revealed that during the pandemic, girls experienced cyberbullying more frequently than boys, whereas boys were more often victims of cyberbullying before the pandemic (

Marinoni et al., 2023). Other findings show no differences between genders (

Hinduja & Patchin, 2014). Socioeconomic status and perceived social class are significant factors in the occurrence of cyberbullying behaviors. Some research indicates that individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more inclined to engage in cyberbullying (

Bevilacqua et al., 2017). Conversely, other studies suggest that individuals with higher perceived socioeconomic status may also be more likely to participate in such behaviors (

Samadieh & Khamesan, 2025). Additionally, family factors, such as family support, conflict, and communication problems (

Rodriguez-Rivas et al., 2022;

Romero-Abrio et al., 2019), psychosocial components including self-esteem, stress, and anxiety (

Shkurina, 2024), and peer group pressure (

Álvarez-Turrado et al., 2024;

Yang et al., 2022), play a crucial role in predicting cyberbullying.

Psychosocial Consequences of Cyberbullying

Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization are linked to a variety of short-term and long-term cognitive, behavioral, social, and emotional impacts across different individuals. Research indicates that cybervictimization is correlated with reduced subjective well-being (

Tao et al., 2024), heightened anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts (

Kee et al., 2024;

Lee, 2021;

Lee et al., 2021), as well as decreased life satisfaction (

Viner et al., 2019) in adolescents and young adults. Moreover, cyberbullying can lead to issues such as feelings of loneliness (

Tong et al., 2024), disrupted sleep, and depression in university students (

Jiang & Jiang, 2024;

Sun et al., 2024), alongside psychotic experiences and suicidal ideation in young adults (

Fekih-Romdhane et al., 2024). However, some studies suggest that the severity of psychological problems tends to be greater among cybervictims and those who are both bullies and victims, compared to cyberbullies alone (

Sun et al., 2024). In summary, some research suggests that the repercussions of cyberbullying may surpass those of traditional bullying (

Li et al., 2024). This is attributed to the fact that cyberbullies can easily reach a larger audience and, crucially, inflict greater harm through the veil of anonymity (

Goebert et al., 2011).

Measuring Cyberbullying

The majority of research on cyberbullying has concentrated on conceptualization (

Englander et al., 2017;

Langos, 2012;

Slonje et al., 2013;

Smith, 2015;

Smith et al., 2008), the prevalence of the phenomenon (

Bottino et al., 2015;

Brochado et al., 2017;

Gohal et al., 2023;

Shariatpanahi et al., 2021), and its associated factors (

Kee et al., 2024;

Jiang & Jiang, 2024;

Sun et al., 2024), particularly during adolescence period (

Álvarez-Turrado et al., 2024;

Bottino et al., 2015;

Chen et al., 2025). However, fewer studies have specifically focused on measuring cyberbullying. Various instruments have been developed for this purpose, but they have significant limitations. First, some instruments use a unidimensional structure to measure cyberbullying (

Akbulut et al., 2010;

Stewart et al., 2014) and often include binary response items (

Hinduja & Patchin, 2007;

Menesini et al., 2011). These instruments typically measure either cyberbullying perpetration or cyberbullying victimization. For example,

Hinduja and Patchin (

2007,

2008) utilized two general scales of cyberbullying with binary-coded items. Similarly, the

Menesini et al. (

2011) instrument included two scales for cyberbullying and cybervictimization, with items scored in a binary manner.

Second limitation is the failure to account for the complexity of the cyberbullying construct. For example, some studies use single-item scales to measure cyberbullying (

Allen, 2012;

Bossler & Holt, 2010). Single-item instruments, while simple and easy to administer, have notable limitations compared to multi-item instruments. They are less reliable and cannot capture the complexity of constructs, making them prone to errors (

Murphy & Davidshofer, 2005). They also struggle with multidimensional constructs, unlike multi-item scales which address various facets (

Diamantopoulos et al., 2012). Furthermore, single-item instruments may lack content validity, as they might not fully represent the theoretical domain of the construct (

Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, 2009). A meta-analysis by

Chun et al. (

2020) also found that many cyberbullying instruments are single-factor and lack subscales (e.g.,

Ang & Goh, 2010;

Badaly et al., 2015;

Dinkes et al., 2009), making it challenging to accurately assess the different types of cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Further, some current cyberbullying instruments fail to encompass all four key components of the cyberbullying definition. For instance, the instrument employed by

Williams and Guerra (

2007) omits the element of repetition.

Third, some instruments have methodological flaws concerning psychometric properties and item construction, as they do not fully report the validity and reliability of the instruments (

Salmivalli et al., 2013;

Smith et al., 2008). Furthermore, certain instruments do not specify the contexts and devices (e.g., internet, mobile, etc.) through which cyberbullying occurs (

Del Rey et al., 2015;

Garaigordobil, 2015). Moreover, many scales available in Western countries are designed and validated within those regions, and various studies have shown that cultural factors influence the phenomenon of cyberbullying (

Barlett et al., 2014). Research indicates that very few instruments have been developed in Asian countries (e.g.,

Ang & Goh, 2010;

Lam & Li, 2013). Besides the aforementioned limitations, the focus of the instruments on specific groups further limits their applicability. Reviews of existing instruments reveal that most are specifically designed for adolescents and high school students (

Antoniadou et al., 2016;

Badaly et al., 2015;

Cassidy et al., 2009), while very few instruments have been created to measure cyberbullying and cybervictimization among university students, who are in the sensitive period of emerging adulthood. Moreover, university students appear to interact with the Internet in a manner distinct from teenagers (

Shapka & Maghsoudi, 2017).

Some researchers have endeavored to create more comprehensive tools to address these shortcomings. One such tool is the Cyberbullying Perpetration (CBP) and Cyberbullying Victimization (CBV) scales, developed by

Lee et al. (

2017), which are specifically designed to assess various types of cyberbullying perpetration and cyberbullying victimization behaviors among university students. These scales were independently created by

Lee et al. (

2017) based on methodologies from Hunt et al. (2012) and

Cassidy et al. (

2009). Initially, experts evaluated the content validity of the instrument, which originally contained 90 items, later refined to 79 items, with 36 items revised. Subsequently, 286 undergraduate students, aged 18 to 25, majoring in social sciences at a university in the southeastern United States, participated in the study on a purposive sampling basis. During data analysis, 36 items were eliminated due to excessive skewness or kurtosis, resulting in a final questionnaire comprising 47 items (20 for CBP and 27 for CBV). The instrument demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.93 for CBP and 0.95 for CBV. Reliability coefficients for subscales (verbal/written, visual/sexual, and social exclusion) ranged from 0.73 to 0.95. Confirmatory factor analysis validated the multidimensional structure of the scales, showing a good model fit. Additionally, the positive and significant correlations between the aggression questionnaire and global CBP scores and subscales (ranging from 0.24 to 0.38) and between global CBV scores and the multidimensional peer victimization scale (ranging from 0.21 to 0.31) confirmed the instrument’s convergent validity.

This instrument has been utilized in various research studies. For example, in a study investigating the prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization among nursing students in Jordan, the reliability of these scales was evaluated (

Al-shatnawi et al., 2024). Following translation and alignment with the original language, a preliminary study reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.81 for the CBP scale and 0.92 for the CBV scale. Another study focusing on the predictive factors of cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization among Polish undergraduate students employed the CBP and CBV scales developed by

Lee et al. (

2017). Internal consistency, as determined by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, ranged from 0.53 to 0.77 for the CBP subscales, and from 0.78 to 0.84 for the CBV subscales. A study utilized the CBV scale to explore the association between cyber victimization and psychological distress among Pakistani students. The Cronbach’s alpha for the overall cyber victimization score in this research was reported to be 0.95. Additionally, the positive correlation found between cyber victimization and psychological distress serves as evidence supporting the convergent validity of this scale (

Shaheen et al., 2023). However, a major limitation of these studies is the insufficient examination of the validity of Lee et al.’s (2017) scale, particularly in terms of the factor structure and the replicability of this structure across different cultures. Additionally, a review of bullying instruments used within the Iranian student population revealed significant gaps in this area. In a systematic review study by

Samadieh et al. (

2024), it was observed that some instruments adopt single-factor structures focusing solely on one dimension of cyberbullying (CBP or CBV) (

Sharafi Zadegan et al., 2024). While other instruments may consider both dimensions of cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization, there is a lack of reported information on their psychometric properties (Ghadampour et al., 2017). Furthermore, the item construction process and content validity examination of some instruments are not clearly defined, leading to methodological weaknesses.

The Current Study

The CBP and CBV scales, exhibit strong psychometric properties across student populations in the United States (

Lee et al., 2017), Jordan (

Al-shatnawi et al., 2024), Poland (

Shkurina, 2024), and Pakistan (

Shaheen et al., 2023). These scales have shown high internal consistency. Additionally, there is substantial evidence supporting the convergent validity of these scales. Nevertheless, there remains a significant research gap due to the lack of independent psychometric studies thoroughly assessing the validity and reliability of the CBP and CBV scales. Furthermore, most cyberbullying research has been conducted in Western societies, with fewer studies investigating and measuring various aspects of cyberbullying in Asian countries, particularly the Middle East. It is crucial to note that, as previously mentioned, this tool has not undergone validation in Iran. Furthermore, other utilized tools also exhibit significant methodological limitations. Therefore, the primary objective of the present study is to examine the factor structure and reliability of the CBP and CBV scales among Iranian students. The following sections present the results of multiple independent studies that examined the factor structure. The first study evaluated the content validity of the CBP and CBV scales. The second study presented the findings of the exploratory factor analysis and the associated reliability results of these scales. The third study investigated the confirmatory factor analysis in an independent sample and included results on criterion validity and predictive validity.

Study 1

In this study, the content validity of the CBP and CBV scales was assessed by experts to determine the extent to which their items encompass the content domain. Subsequently, students evaluated the accuracy and precision of the scales’ translation, while the selectivity of the items was also investigated.

Method

Participants

A total of 20 professionals participated in the content validity study. The sample was purposefully selected. The ages of the participants ranged from 36 to 63, with an average age of 52.86 years (SD = 3.15). The majority were male (70%, n = 14), and 90% (n = 18) held a PhD. Among the experts, 60% (n = 12) were involved in teaching and research in the field of psychology, 30% (n = 6) worked in counseling, and 10% (n = 2) were in social sciences. To assess the accuracy and precision of the statements among students, 35 undergraduate students were selected through convenience sampling. Their ages ranged from 18 to 34, with an average age of 20.54 years (SD = 2.59). The majority were female (51.4%, n = 18), and 91.4% (n = 32) were unmarried.

Measure

Participants in the initial sample group completed the Cyberbullying Perpetration (CBP) and Cybervictimization (CBV) scales developed by

Lee et al. (

2017), comprising 20 and 27 items respectively. The CBP scale measures aggressive and harmful behaviors directed at one or more individuals through mobile or internet means and is divided into three subscales: verbal/written cyberbullying (9 items), visual/sexual cyberbullying (5 items), and social exclusion (6 items). Conversely, the CBV scale assesses the experience of being a target of aggression and harassment through technological means, including mobile phones, and consists of three subscales: verbal/written cybervictimization (10 items), visual/sexual cybervictimization (10 items), and social exclusion (7 items). Responses for both the CBP and CBV scales are recorded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = never” to “5 = very often.” The possible scores for the CBV scale range from 27 to 135 points, with higher scores indicating greater levels of victimization. For the CBP scale, the possible scores range from 20 to 100 points, with higher scores signifying higher levels of cyberbullying perpetration.

Procedure

The English version of the CBP and CBV scales was translated into Persian by a faculty member from the Department of Psychology. The translated version was then back-translated into English by a faculty member from the English Language Teaching Department. Subsequently, the authors compared the two versions and made the necessary corrections to the translation. Data collection from experts was conducted using a content validity form. Students were provided with explanations regarding the research objectives, confidentiality of the information, and voluntary participation in the study. Their opinions on the simplicity and comprehensibility of the items were recorded accurately.

Data Analysis

The necessity of the items (

Lawshe, 1975) and their relevance (

Lynn, 1986) were assessed by experts and then the Content Validity Ratio and Content Validity Index were calculated. To evaluate internal consistency, correlation coefficients between items and item-total correlations (ITCs) were also examined. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.

Results

In the content validity study, experts provided corrective feedback on certain items, which were subsequently revised based on their input. The Content Validity Ratio for all items and the overall scale exceeded 0.42 (range: 0.58-0.99). Similarly, the Content Validity Index for all items and the entire scale was greater than 0.79 (range: 0.81-0.99). During the initial administration of the scales to students, three items were found to be incomprehensible. These items were rephrased to address cultural considerations, following consultations with experts and the primary authors (

Lee et al., 2017). In the internal consistency study, the correlation of each item’s score with other items and with the total score was examined. The results indicated that the inter-item correlations for the CBP ranged from 0.29 to 0.74, with ITCs ranging from 0.35 to 0.70. The Cronbach’s alpha for the entire CBP scale was 0.91. For the CBV, inter-item correlations ranged from 0.27 to 0.74, with ITCs ranging from 0.34 to 0.86. The Cronbach’s alpha for the entire CBV scale was 0.94.

Brief Discussion

The results of the first study provide strong evidence for the content validity of the CBP and CBV scales within the Iranian student population. The participation of 20 highly qualified professionals, predominantly male and primarily holding PhDs, ensured that the evaluation was thorough and grounded in substantial expertise. The diverse backgrounds of the experts, spanning psychology, counseling, and social sciences, contributed to a comprehensive assessment of the scales’ content.

The Content Validity Ratio and Content Validity Index results were notably high, with all items and the overall scale exceeding the thresholds for validity. Specifically, the Content Validity Ratio values ranged from 0.58 to 0.99, and the Content Validity Index values ranged from 0.81 to 0.99, indicating that the items on the CBP and CBV scales are both necessary and relevant to the construct being measured. In addition to the experts’ evaluations, the feedback from 35 undergraduate students highlighted areas where the translation and wording of the items needed refinement. The process of back-translation and subsequent revision ensured that the scales were culturally appropriate and comprehensible to the Iranian student population. The internal consistency analysis further supported the reliability of the scales. The inter-item correlations (IICs) for the CBP and CBV scales indicated moderate to strong relationships among the items, with ITCs reinforcing the cohesiveness of the scales. The Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.91 for the CBP scale and 0.94 for the CBV scale demonstrate excellent internal consistency, suggesting that the scales are reliable measures of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization.

Overall, the findings from the first study underscore the robust psychometric properties of the CBP and CBV scales in an Iranian context. The high content validity, coupled with strong internal consistency, supports the use of these scales for assessing cyberbullying behaviors among Iranian students. These results lay a solid foundation for further research and application of the CBP and CBV scales in various educational and clinical settings in Iran. Future studies should continue to explore and refine these instruments to ensure their effectiveness and applicability across different populations and cultural contexts.

Study 2

The second study investigated the exploratory factor validity of the CBP and CBV scales. Employing exploratory factor analysis, the study examined the factor structure of both scales. Additionally, the reliability of the scales was assessed.

Method

Participants

A sample of 276 undergraduate students from a public university in Birjand, Iran was selected through convenience sampling. The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 42 years, with a mean age of 22.63 years (SD = 4.14). Over half of the participants were female (51.1%, n = 141), and 90.6% (n = 250) were unmarried.

Measures

In the second study, we administered the CBP and CBV scales (

Lee et al., 2017) to the participants. The CBP scale includes 20 items and comprises three distinct subscales: verbal/written cyberbullying (9 items), visual/sexual cyberbullying (5 items), and social exclusion (6 items). Conversely, the CBV scale, consisting of 27 items, also divided into three subscales: verbal/written cybervictimization (10 items), visual/sexual cybervictimization (10 items), and social exclusion (7 items). Responses for both scales are collected using a five-point Likert scale, with options ranging from “1 = never” to “5 = very often.”

Procedure

Data collection was carried out electronically in compliance with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) and other related guidelines (

Eysenbach, 2012;

Sischka et al., 2022;

Turk et al., 2018). The survey was designed at

https://porsline.ir/, an online survey and form-building platform which allows users to create online surveys, forms, and tests easily and quickly. The platform is user-friendly and cost-effective, making it accessible for individuals, businesses, and educational institutions. Visitors to this website are typically looking for survey creation tools, form building solutions, and data analysis features. The survey link was exclusively accessible to university students who were identified by the survey collectors as students and were provided with the link. The survey was advertised on various social media platforms, including WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram, and several Iranian messaging apps. It was distributed to professors and student group administrators on the social networking apps. The electronic forms provided explanations to participants about the objectives of the project and, while assuring them of the confidentiality of the information, emphasized the voluntary nature of participation in the research.

Participation was entirely voluntary, allowing participants the option to skip any question they preferred not to answer. The students neither received incentives nor faced penalties for their involvement. To reduce biases, the items were presented in a random order. The sample group was provided with the opportunity to review and revise their responses before the final submission of the survey. The questionnaire was configured to prevent multiple entries by the same individual.

Data Analysis

Factor validity was examined using principal component analysis (PCA), considering a minimum factor loading of 0.40 for each item (

Stevens, 2012). The identification of the factor structure was guided by Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalues greater than one) and Cattell’s criterion (the elbow rule), along with factor loadings and the interpretability of factor solutions (Braeken, & Van Assen, 2017). Factor rotation was performed using direct Oblimin. To assess reliability, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and the Spearman-Brown split-half (rkk) methods were employed. Correlations between CBP and CBV were also examined. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.

Results

In the exploratory factor validity study, Keiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were first calculated. The results indicated that with KMO coefficients greater than 0.70 and significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (

p < .001), the conditions for factor analysis were met. PCA of the CBP and CBV scales revealed three factors (eigenvalue > 1.00). The Scree Plot also supported these structures. To ensure the accuracy of the factor identification, a parallel analysis was conducted using the Monte Carlo PCA program. By systematically comparing the eigenvalues derived from SPSS with those obtained from random results generated by the parallel analysis, the three-factor structure for both the CBP and CBV scales was confirmed. However, in the CBP scale, item 3 (“I sent a bad email to someone with the intention of harassing them”) from the Verbal/Written factor and item 15 (“I blocked someone in a chat room to harass them”) from the Social Exclusion factor had factor loadings of less than 0.40. The analysis was repeated after removing these items, resulting in a three-factor structure with a cumulative variance explained rate of 77.65%. The communalities for all remaining items were greater than 0.50. As shown in

Table 1, the items had factor loadings greater than 0.58.

For the CBV scale, items 10 (“They sent me messages on purpose to upset me”), 13 (“Someone posted humiliating pictures or videos of me on social media or in chat rooms to embarrass me”), and 23 (“Someone rejected my request to play online to upset me”) had factor loadings of less than 0.40. The analysis was repeated after removing these items, resulting in a cumulative variance explained rate of 74.33%. The communalities for all remaining items were greater than 0.50. As shown in

Table 1, the items had factor loadings greater than 0.64.

Table 2 shows that there are positive and significant relationships between the CBP and CBV dimensions (

p < 0.05). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for CBP ranged from .88 to .97. Spearman-Brown split-half coefficients also ranged from .75 to .98.

Brief Discussion

In the second study, our goal was to investigate the exploratory factor validity of the CBP and CBV scales. The exploratory factor analysis results indicated a three-factor structure for both scales. Additionally, the reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients showed that both scales are reliable and valid.

The KMO coefficients and Bartlett’s test of sphericity results confirmed that the data were suitable for factor analysis, with KMO values exceeding 0.70 and significant results for Bartlett’s test. These findings suggest that the sample was adequate and the items were sufficiently correlated for PCA. The PCA results identified three factors for each scale. However, in the CBP scale, item 3 (I sent someone a nasty email to hurt them) from the Verbal/Written factor and item 15 (I blocked someone in a chat room to hurt them) from the Social Exclusion factor were removed due to low factor loadings. Similarly, in the CBV scale, items 10 (They sent me messages on purpose to hurt me), 13 (Someone posted degrading pictures or videos of me on social media or in chat rooms to embarrass me), and 23 (Someone rejected my request to play online to hurt me) were removed for having factor loadings below 0.40. After removing these items, the reanalysis showed that the three-factor structures in the CBP and CBV scales explained 77.65% and 74.33% of the cumulative variance, respectively.

The three-factor structure obtained for the CBP and CBV scales aligns with the research by

Lee et al. (

2017), confirming the multidimensionality of the cyberbullying construct and supporting theoretical foundations and previous studies. For instance,

Smith et al. (

2008) identified two primary forms of cyberbullying: verbal/written bullying and visual bullying. Other studies have empirically validated this classification (

Macaulay et al., 2022;

Palladino et al., 2017). Furthermore, Willard’s classification (2007) for various forms of bullying (i.e., flaming, harassment, denigration, impersonation, outing, trickery, exclusion, cyberstalking) can be conceptually categorized into three general types: verbal/written bullying, visual/sexual bullying, and social exclusion. While treating cyberbullying as a single construct may be suitable for some purposes, different aspects of cyberbullying, such as gender differences and effects, can vary depending on the specific type of cyberbullying experienced (

Slonje et al., 2013). Consequently, the three-factor structure is well-aligned with both theoretical foundations and research evidence. Items were deleted likely because the medium or context in which bullying occurred was not sufficiently representative of individuals’ experiences.

The study also demonstrated the excellent internal consistency of the CBP and CBV scales. Comparing Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the CBP and CBV scales with those in

Lee et al. (

2017) shows higher coefficients in the current study. Additionally, comparing these internal consistency coefficients with similar scales (e.g.,

Antoniadou et al., 2016;

Badaly et al., 2015;

Doane et al., 2013) further supports the higher internal consistency of the CBP and CBV scales. Analyses of item characteristics in this study confirmed the homogeneity of the subscales, showing no extreme low or high mean interitem correlations.

Study 3

The third study had two major objectives: First, by using a larger sample, the three-factor structures of the CBP and CBV scales from the study 2 were assessed using confirmatory factor analysis. Second, the reliability and convergent validity of the constructs were evaluated. The examination of reliability and criterion validity was conducted concerning age and gender. Convergent validity was analyzed in relation to Olweus bullying, and predictive validity was evaluated concerning sense of belonging, subjective vitality, life satisfaction, and psychological distress.

Method

Participants

In this research, a total of 580 students from four universities in Iran were chosen through convenience sampling. The participants’ age ranged from 18 to 45 years, with an average age of 21.94 years (SD=3.53). The majority of the participants were female (60.7%, n=352), and 90.9% (n=527) were single.

Measures

Cyberbullying Perpetration (CBP) and Cyberbullying Victimization (CBV): Participants completed the finalized versions of the CBP and CBV scales from Study Two. The CBP scale comprises 18 items divided into three subscales: verbal/written (8 items), sexual/visual (5 items), and social exclusion (5 items). The CBV scale contains 24 items, also divided into three subscales: verbal/written (9 items), sexual/visual (9 items), and social exclusion (6 items).

Global Key Questions on Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization: Within the questionnaire package, two additional items were incorporated to assess students’ involvement in cyberbullying and cybervictimization (

Olweus, 1996). These items were adapted from the Olweus global key question for bullying and victimization. Students were asked to report the frequency of their involvement in cyberbullying and cybervictimization incidents. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, with options ranging from 0 (not at all), 1 (once or twice), 2 (two or three times a month), 3 (every week), to 4 (several times a week).

State Level Subjective Vitality (SVS-SL): To measure subjective vitality, the State Level Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS-SL) was employed. The original version comprises seven items, each rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (completely true).

Ryan and Frederick (

1997) confirmed the factorial validity, with a one-factor structure accounting for 70% of the variance and reported a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .92. Tanhaye Reshvanloo et al. (2019) validated a six-item version, confirming both exploratory and confirmatory factorial validity, which explained 75.04% of the variance with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .93 and .92, respectively. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was found to be .91.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS): Developed by Diener et al. (1985), this scale comprises five statements rated on a seven-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total score reflects overall life satisfaction, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. In the original study, factor validity and favorable convergent relationships with positive emotions (r=0.50) and negative emotions (r=-0.37) were reported (Diener et al., 1985).

Maroufizadeh et al. (

2016) further confirmed the scale’s convergent validity concerning anxiety (r=-0.41) and depression (r=-0.43). Their study reported the Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Kessler Stress Scale (K6): Developed by

Kessler et al. (

2002), the Kessler Stress Scale (K6) contains six items rated on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Higher scores indicate greater psychological distress. The scale’s validity and reliability have been confirmed in numerous studies (

Kessler et al., 2010). Tanhaye Reshvanloo et al. (2020) also confirmed the scale’s exploratory and confirmatory factor validity, reporting favorable convergent validity in relation to depression (r=0.60), anxiety (r=0.46), and stress (r=0.48). In their study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86, and the split-half coefficient was 0.83. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.82.

Procedure

In this study, akin to the previous phase, data collection was carried out online. The questionnaire was created using the platform

https://porsline.ir/, and the link was disseminated through engagement with professors and student group managers within social network class groups. Four psychology master’s students from universities in various regions of Iran (north, south, east, and west) were trained to conduct the research online. The electronic forms included detailed information about the project objectives and assured participants of the confidentiality of their information, highlighting the voluntary nature of their participation. Completing the questionnaire was voluntary, and no incentives were provided to encourage participation. The data collection period spanned approximately three months, from early April to the end of June 2024. The questionnaire received 1,570 visits, with a response rate of 71 percent, calculated by dividing the number of individuals who submitted responses by those who began answering the questions.

Data Analysis

A second-order confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the Maximum Likelihood method. Traditional fit indices were employed to assess the model fit (

Hu & Bentler, 1999). To evaluate construct reliability and convergent validity, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated for the factors. Construct reliability is considered achieved if CR > .70, AVE > .50, and the relationship CR > AVE is established (

Hair et al., 2017). The Cronbach’s alpha (α) and the Spearman-Brown split-half coefficient (rkk) were used to assess reliability. The correlation between CBP and CBV with age was also examined. Given the non-normal distribution of variables and lack of homogeneity of variances, the Mann-Whitney Test was utilized to assess gender differences. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 and AMOS version 24.

Results

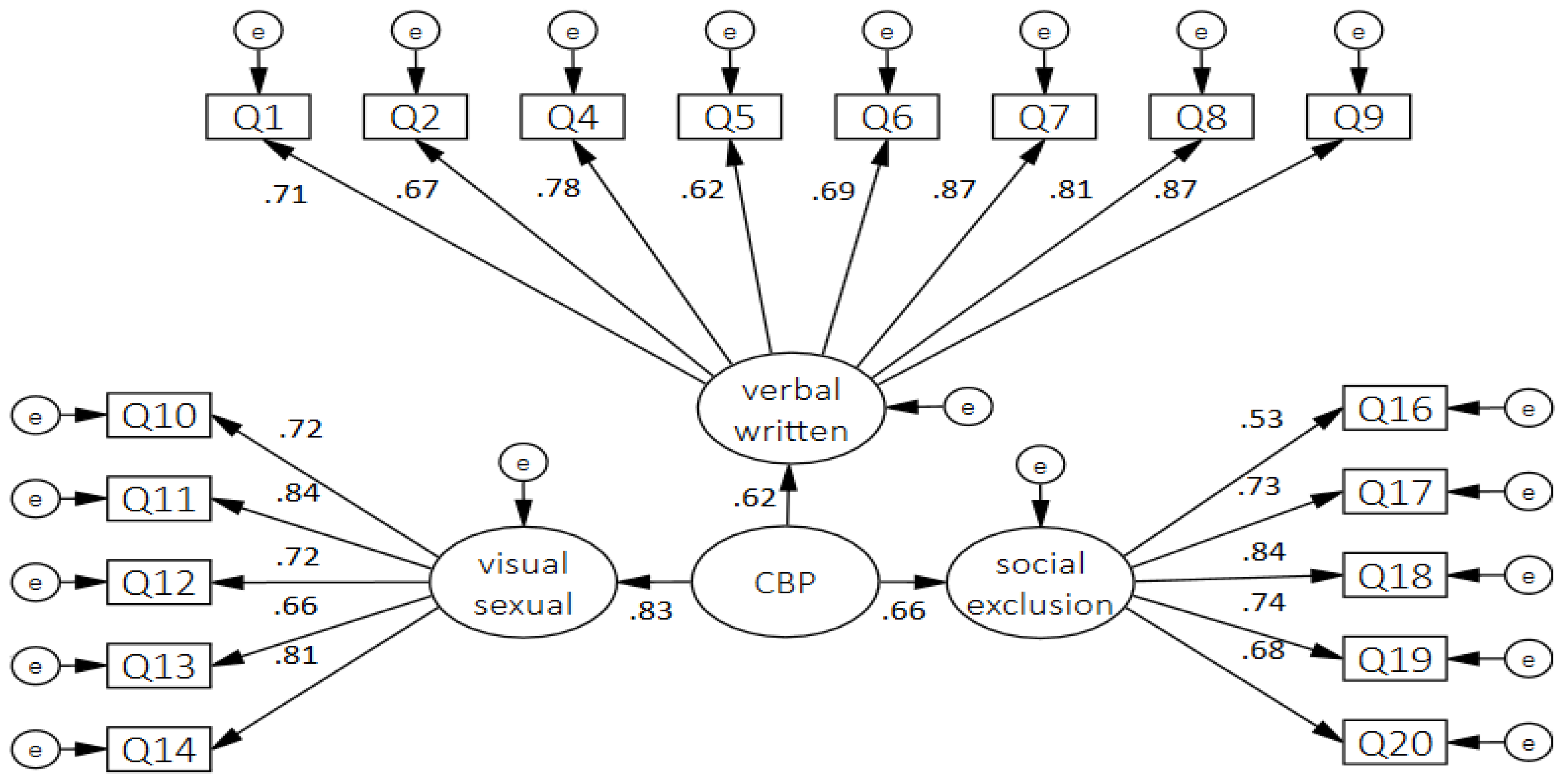

The second-order confirmatory factor analysis (

Figure 1) demonstrated that the first-order factor loadings in the CBP measurement model exceeded 0.50 and were statistically significant (

p < 0.01). The second-order factor loadings ranged from 0.62 to 0.83. The fit indices for the confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the data suitably fit the three-factor models (χ

2/df = 2.92, CFI = .96, NFI = .94, and RMSEA = .058).

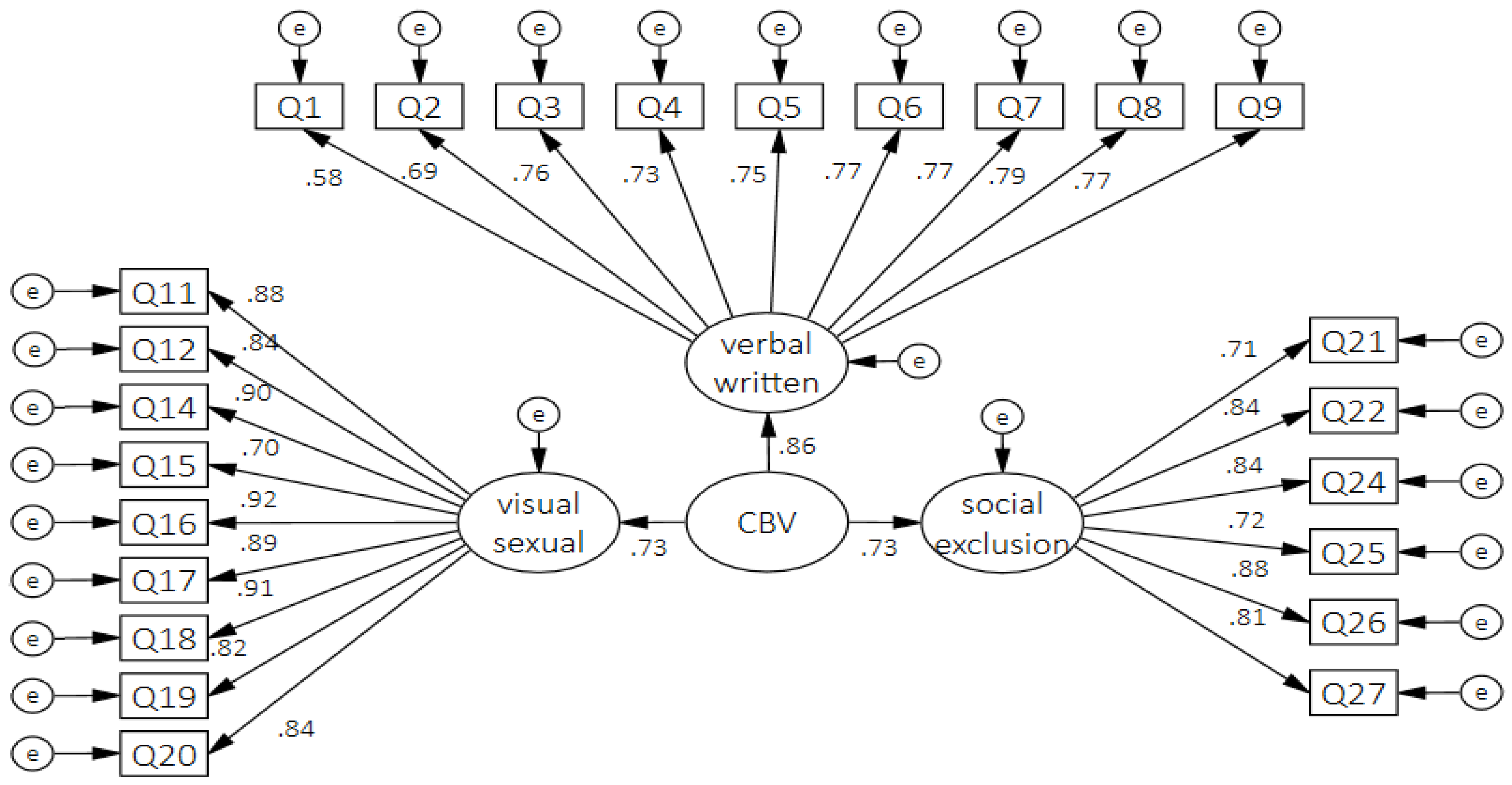

In the construct reliability study, CR coefficients ranged from .51 to .57, while AVE coefficients ranged from .83 to .91. For all factors, the CR>AVE relationship was established, indicating convergent validity. The second-order confirmatory factor analysis for the CBV measurement model revealed that first-order factor loadings were greater than 0.50 and statistically significant (p < 0.01). The second-order factor loadings ranged from 0.73 to 0.86. Fit indices for the confirmatory factor analysis suggested that the data adequately fit the three-factor models (χ2/df = 2.99, CFI = .97, NFI = .95, and RMSEA = .059).

Table 3 demonstrated that in the examination of construct reliability, the CR coefficients ranged from .57 to .96, while the AVE coefficients ranged from .50 to .64. For all factors, the condition CR > AVE was met, indicating convergent validity. The reliability analysis revealed that Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the CBP dimensions varied between .83 and .91, with a total score coefficient of 0.90. In the case of CBV, the coefficients for the dimensions ranged from 0.92 to 0.96, and the total score’s Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95. The Spearman-Brown split-half coefficients for the CBP dimensions varied from .76 to .91, with a total score coefficient of 0.66. For the CBV dimensions, these coefficients ranged from 0.90 to 0.97, and the total score’s coefficient was 0.86.

The findings in

Table 3 indicated a positive and significant relationship between the dimensions and total scores of CBP and CBV with Olvis bullying and psychological distress, while a negative and significant relationship was observed with subjective vitality and life satisfaction (

p < .01). However, age did not show a significant relationship with the dimensions and total scores of CBP and CBV. The Mann-Whitney Test revealed significant differences between women and men only in the subscale CBP-verbal/written (

p < .001, Z = -4.85), CBP-verbal/written (

p < .001, Z = -5.59), CBP total score (

p < .005, Z = -2.81), and CBV-social exclusion (

p < .045, Z = -1.99). Men exhibited higher mean scores in the bullying dimensions.

Brief Discussion

This study further substantiated the three-factor structure of the CBP and CBV scales. The confirmatory factor analysis conducted in the third study validated the presence of three distinct factors for both scales: verbal/written, visual/sexual, and social exclusion. The analysis of the factor structure indicated that the model fit indices were at an acceptable level, with all factor loadings being significant.

For the CBP scale, the CR coefficients ranged from .51 to .57, and the AVE coefficients ranged from .83 to .91. This indicates that while the internal consistency of some factors may be relatively low, the substantial AVE values suggest that the items are well-represented by their respective constructs. The established CR > AVE relationship confirms the convergent validity of the CBP scale, validating its effectiveness in measuring cyberbullying perpetration among students. Similarly, the CBV scale demonstrated a range of CR coefficients from .57 to .96 and AVE coefficients from .50 to .64. These values reflect varying degrees of internal consistency across different factors, with some factors showing higher reliability than others. Nonetheless, the satisfactory AVE values indicate that the latent constructs are adequately captured by the scale items. The CR > AVE relationship further supports the convergent validity of the CBV scale, underscoring its suitability for assessing cyberbullying victimization among students. In conclusion, the psychometric evaluation of the CBP and CBV scales reveals that both scales possess adequate convergent validity and acceptable levels of construct reliability. The CBV scale, in particular, demonstrates higher reliability in certain factors compared to the CBP scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the components in both scales were also satisfactory.

The findings provide several key insights into the relationships between the CBP and CBV scales with various psychological and demographic factors. Firstly, the positive and significant relationships between the dimensions and total scores of CBP and CBV with Olvis bullying and psychological stress suggest that higher levels of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization are associated with increased experiences of bullying and psychological distress. This indicates that individuals who engage in or are victims of cyberbullying are more likely to experience bullying in other forms and suffer from psychological stress.

Conversely, the negative and significant relationships with mental vitality and life satisfaction imply that higher levels of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization are linked to lower mental vitality and decreased life satisfaction. This finding highlights the detrimental impact of cyberbullying on individuals’ overall well-being and quality of life.

Interestingly, age did not show a significant relationship with the dimensions and total scores of CBP and CBV, indicating that the levels of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization do not vary significantly across different age groups within the study population.

The Mann-Whitney Test results revealed significant gender differences in specific subscales and total scores. Women exhibited significantly higher scores in the CBP-verbal/written subscale and the CBP total score, while men had higher mean scores in the dimensions of bullying. In contrast, women had higher mean scores in victimization, as reflected in the CBV-social exclusion subscale. These gender differences suggest that men are more likely to be perpetrators of cyberbullying, whereas women are more likely to be victims, particularly in the context of social exclusion. Overall, these findings underscore the complex interplay between cyberbullying behaviors, psychological factors, and demographic variables. Our findings highlight the need for targeted interventions that address both the perpetration and victimization aspects of cyberbullying to promote mental well-being and life satisfaction among students.

General discussion

The CBP and CBV scales contribute significantly to the understanding of online harassment and victimization, particularly during early adulthood. These scales offer a comprehensive, multidimensional approach to measuring various forms of bullying and victimization in cyberspace, addressing many limitations of earlier tools. Each scale assesses three distinct dimensions of bullying and victimization: verbal/written bullying, visual/sexual bullying, and social exclusion.

The psychometric properties of the CBP and CBV scales were evaluated across three studies. In the first study, experts assessed the content validity of the 20-item CBP and 27-item CBV scales. Students then completed the scales to evaluate the clarity of the items. The second study investigated the exploratory factor validity and reliability of both scales. The analysis supported a three-factor structure for each scale, although two items from the CBP and three items from the CBV were removed due to low factor loadings. The final study used CFA to validate the structure across different samples and examined construct reliability and convergent validity. These results further confirmed the robust three-factor structure and the scales’ validity and reliability, demonstrating their utility for studying cyberbullying behaviors and experiences.

The findings of the current study highlight the notable strengths of the CBP and CBV scales in comparison to previous instruments for assessing cyberbullying experiences. These scales provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating a broad and specific range of cyberbullying behaviors, supported by theoretical and empirical foundations, which is particularly beneficial for understanding bullying during the sensitive period of early adulthood (ages 18–25). This is especially significant in Iran, where no extensive studies have yet assessed the prevalence of various forms of bullying and victimization within this age group. The inclusion of subscales addressing verbal/written, visual/sexual, and social exclusion dimensions represents an important advancement, offering a more nuanced understanding of cyberbullying compared to instruments that focus solely on direct and indirect forms of bullying (e.g.,

Antoniadou et al., 2016) or categorize behaviors into general groups of bullying and victimization (e.g.,

Menesini et al., 2011).

Another strength of the CBP and CBV scales is their design, which incorporates the types of devices and social media platforms commonly used by adolescents and young adults, especially in Iran. This consideration enables a more thorough assessment of diverse cyberbullying behaviors across different contexts. Additionally, the study demonstrated the high reliability for these scales, with reliability coefficients surpassing those of other instruments used to assess early adulthood experiences (e.g.,

Bennett et al., 2011; Spitzberg et al., 2002). The examination of validity through multiple methods—including content, exploratory factor, confirmatory factor, convergent, and predictive validity—further supports the psychometric robustness of the scales. This aligns with findings from meta-analyses that have identified limitations in reporting the validity of existing instruments (

Chun et al., 2020). The use of a large and diverse sample from multiple universities in Iran reinforces the generalizability of the CBP and CBV scales, while also reflecting the country’s rich cultural diversity. These validated tools offer valuable insights for future epidemiological research and practical applications in understanding and addressing cyberbullying behaviors within this demographic.

While this study has notable strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the recruitment of participants relied on convenience sampling, conducted primarily online during different phases of the research (Studies 2 and 3). This approach may introduce sampling bias, as individuals who were more active online or had easier access to the internet were more likely to participate. Second, the sample exclusively comprised university students, limiting the generalizability of findings to non-student populations within the early adulthood age group. This restricted scope may not fully represent the broader experiences of cyberbullying victimization among young adults outside the academic setting.

Additionally, while validating the CBP and CBV scales within an Iranian population adds value for local studies, these scales’ applicability and robustness in diverse cultural contexts remain untested. Future research should examine their reliability and validity in other cultural and demographic settings. Social desirability bias may also have influenced responses, potentially leading participants to underreport their experiences with bullying or victimization due to stigma or discomfort.

Further limitations include the reliance on self-report measures, which are inherently susceptible to subjective interpretation and potential inaccuracies. The cross-sectional design of the study restricts causal inference, preventing conclusions about the directionality of the relationships examined. Lastly, the absence of longitudinal data limits the understanding of how cyberbullying and its psychological impacts evolve over time. Addressing these limitations in future studies could enhance the depth and applicability of the findings.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the Iranian version of the CBP and CBV scales within a university sample, contributing to the body of research on cyberbullying in early adulthood. The findings confirmed the validity and reliability of these scales, offering a robust tool for assessing a multidimensional construct of cyberbullying behaviors, including verbal/written, visual/sexual, and social exclusion dimensions. These validated scales provide researchers with a comprehensive instrument to explore cyberbullying dynamics more effectively in the Iranian context and beyond.

From a theoretical perspective, the study highlights the need to conceptualize cyberbullying as a multifaceted phenomenon that varies across digital platforms and social contexts. Future research should expand upon these findings by applying the scales in diverse populations, such as non-students or individuals from different cultural backgrounds, to further validate the instruments. Additionally, longitudinal studies are encouraged to examine the long-term effects of cyberbullying behaviors and victimization, as well as the psychological mechanisms that mediate or moderate these outcomes. The integration of contextual variables, such as cultural norms and technological advancements, could further refine the theoretical understanding of cyberbullying.

On a practical level, the CBP and CBV scales can be instrumental in identifying at-risk individuals and guiding targeted interventions. Mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers can use these tools to develop prevention and intervention strategies tailored to the unique challenges posed by cyberbullying. For example, educational campaigns could leverage the findings to raise awareness about the impact of specific forms of cyberbullying, while policymakers could formulate digital safety policies to reduce harmful behaviors online. Moreover, institutions of higher education can integrate the use of these scales in mental health assessments to ensure timely support for students exposed to cyberbullying. In summary, the study provides a validated, multidimensional measure of cyberbullying in the Iranian context and underscores its theoretical and practical implications for advancing research and fostering safer digital environments.

Funding

This research did not receive financial support from any public, commercial, or nonprofit funding organizations.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines outlined by the Research Ethics Committee in University of Birjand. The research protocol was reviewed and approved under the ethical code IR.BIRJAND.REC.1402.017.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participation was voluntary and dependent on acknowledgment and acceptance of the informed consent agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest, whether financial, personal, or professional, are associated with this research or its publication.

References

- Akbulut, Y., Y. L. Sahin, and B. Eristi. 2010. Development of a scale to investigate cybervictimization among online social utility members. Contemporary Educational Technology 1, 1: 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K. P. 2012. Off the radar and ubiquitous: Text messaging and its relationship to ‘drama’and cyberbullying in an affluent, academically rigorous US high school. Journal of Youth Studies 15, 1: 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-shatnawi, F. A. E., A. M. T. Ababneh, F. M. Elemary, A. Rayan, and M. H. Baqeas. 2024. Prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration and cyberbullying victimization among nursing students in Jordan. SAGE Open Nursing 10: 23779608241256509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Turrado, B., D. Falla, and E. M. Romera. 2024. Peer Pressure and Cyberaggression in Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Moral Disengagement Strategies. Youth & Society, 0044118X241306114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, R. P., and D. H. Goh. 2010. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 41: 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, N., C. M. Kokkinos, and A. Markos. 2016. Development, construct validation and measurement invariance of the Greek cyber-bullying/victimization experiences questionnaire (CBVEQ-G). Computers in Human Behavior 65: 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaly, D., M. T. Duong, A. C. Ross, and D. Schwartz. 2015. A peer-nomination assessment of electronic forms of aggression and victimization. Journal of Adolescence 44: 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C. P., D. A. Gentile, C. A. Anderson, K. Suzuki, A. Sakamoto, A. Yamaoka, and R. Katsura. 2014. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 45, 2: 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D. C., E. L. Guran, M. C. Ramos, and G. Margolin. 2011. College students’ electronic victimization in friendships and dating relationships: Anticipated distress and associations with risky behaviors. Violence and Victims 26, 4: 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, L., N. Shackleton, D. Hale, E. Allen, L. Bond, D. Christie, and R. M. Viner. 2017. The role of family and school-level factors in bullying and cyberbullying: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatrics 17: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossler, A. M., and T. J. Holt. 2010. The effect of self-control on victimization in the cyberworld. Journal of Criminal Justice 38, 3: 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, S. M. B., C. Bottino, C. G. Regina, A. V. L. Correia, and W. S. Ribeiro. 2015. Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Cadernos de Saude Publica 31: 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braeken, J., and M. A. Van Assen. 2017. An empirical Kaiser criterion. Psychological Methods 22, 3: 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A., O. Santesteban-Echarri, K. S. Cadenhead, B. A. Cornblatt, E. Granholm, and J. Addington. 2022. Bullying and social functioning, schemas, and beliefs among youth at clinical high risk for psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 16, 3: 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochado, S., S. Soares, and S. Fraga. 2017. A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 18, 5: 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, W., M. Jackson, and K. N. Brown. 2009. Sticks and stones can break my bones, but how can pixels hurt me? Students’ experiences with cyber-bullying. School Psychology International 30, 4: 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Y. Xiong, L. Yang, Y. Liang, and P. Ren. 2025. Bullying victimization and self-harm in adolescents: The roles of emotion regulation and bullying peer norms. Child Abuse & Neglect 160: 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J., J. Lee, J. Kim, and S. Lee. 2020. An international systematic review of cyberbullying measurements. Computers in Human Behavior 113: 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R., J. A. Casas, R. Ortega-Ruiz, A. Schultze-Krumbholz, H. Scheithauer, P. Smith, and P. Plichta. 2015. Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior 50: 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A., M. Sarstedt, C. Fuchs, P. Wilczynski, and S. Kaiser. 2012. Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40: 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkes, R., J. Kemp, and K. Baum. 2009. Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2009. NCES 2010-012/NCJ 228478. National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Doane, A. N., M. L. Kelley, E. S. Chiang, and M. A. Padilla. 2013. Development of the cyberbullying experiences survey. Emerging Adulthood 1, 3: 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englander, E., E. Donnerstein, R. Kowalski, C. A. Lin, and K. Parti. 2017. Defining cyberbullying. Pediatrics 140 Suppl. 2: S148–S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. 2012. Correction: Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of Medical Internet Research 14, 1: e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih-Romdhane, F., D. Malaeb, N. Farah, M. Stambouli, M. Cheour, S. Obeid, and S. Hallit. 2024. The relationship between cyberbullying perpetration/victimization and suicidal ideation in healthy young adults: The indirect effects of positive and negative psychotic experiences. BMC Psychiatry 24, 1: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C., and A. Diamantopoulos. 2009. Using single-item measures for construct measurement in management research: Conceptual issues and application guidelines. Die Betriebswirtschaft 69, 2: 195. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, M. 2015. Cyberbullying in adolescents and youth in the Basque Country: Prevalence of cybervictims, cyberaggressors, and cyberobservers. Journal of Youth Studies 18, 5: 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadampour, E. 2017. Relationships among cyberbullying, psychological vulnerability and suicidal thoughts in female and male students. Journal of Research in Psychological Health 11, 3: 28–40. http://rph.khu.ac.ir/article-1-3040-en.html. [CrossRef]

- Gohal, G., A. Alqassim, E. Eltyeb, A. Rayyani, B. Hakami, A. Al Faqih, and M. Mahfouz. 2023. Prevalence and related risks of cyberbullying and its effects on adolescent. BMC Psychiatry 23, 1: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebert, D., I. Else, C. Matsu, J. Chung-Do, and J. Y. Chang. 2011. The impact of cyberbullying on substance uses and mental health in a multiethnic sample. Maternal and Child Health Journal 15: 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., L. M. Matthews, R. L. Matthews, and M. Sarstedt. 2017. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 1, 2: 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S., and J. W. Patchin. 2007. Offline consequences of online victimization: School violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence 6, 3: 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S., and J. W. Patchin. 2008. Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior 29, 2: 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S., and J. W. Patchin. 2014. Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Corwin press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6, 1: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., and S. Jiang. 2024. Growing up in adversity: A moderated mediation model of family conflict, cyberbullying perpetration, making sense of adversity and depression. Youth & Society 56, 4: 754–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. M. H., A. Anwar, and I. Vranjes. 2024. Cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation: The mediating role of psychological distress among Malaysian youth. Computers in Human Behavior 150: 108000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., G. Andrews, L. J. Colpe, E. Hiripi, D. K. Mroczek, S. L. Normand, and A. M. Zaslavsky. 2002. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine 32, 6: 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., J. G. Green, M. J. Gruber, N. A. Sampson, E. Bromet, M. Cuitan, and A. M. Zaslavsky. 2010. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 19, S1: 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. 2018. Cyberbullying. In The Routledge international handbook of human aggression. Routledge: pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, R. M., G. W. Giumetti, A. N. Schroeder, and M. R. Lattanner. 2014. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 140, 4: 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. T., and Y. Li. 2013. The validation of the E-Victimisation Scale (E-VS) and the E-Bullying Scale (E-BS) for adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior 29, 1: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langos, C. 2012. Cyberbullying: The challenge to define. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 15, 6: 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawshe, C. H. 1975. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology 28, 4: 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., N. Abell, and J. L. Holmes. 2017. Validation of measures of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in emerging adulthood. Research on Social Work Practice 27, 4: 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. 2021. Pathways from childhood bullying victimization to young adult depressive and anxiety symptoms. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 52, 1: 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., J. Chun, J. Kim, and J. Lee. 2020. Cyberbullying victimization and school dropout intention among South Korean adolescents: The moderating role of peer/teacher support. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development 30, 3: 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., J. Chun, J. Kim, J. Lee, and S. Lee. 2021. A social-ecological approach to understanding the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation in South Korean adolescents: The moderating effect of school connectedness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 20: 10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., P. Wang, M. Martin-Moratinos, M. Bella-Fernández, and H. Blasco-Fontecilla. 2024. Traditional bullying and cyberbullying in the digital age and its associated mental health problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 33, 9: 2895–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S., G. Mascheroni, K. Ólafsson, and L. Haddon. 2014. Children’s online risks and opportunities: Comparative findings from EU Kids Online and Net Children Go Mobile; London: London School of Economics and Political Science. Available at www.eukidsonline.net; http://www.netchildrengomobile.eu/.

- Lynn, M. R. 1986. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research 35, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufizadeh, S., A. Ghaheri, R. O. Samani, and Z. Ezabadi. 2016. Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in Iranian infertile women. International Journal of Reproductive Biomedicine 14, 1: 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Macaulay, P. J., L. R. Betts, J. Stiller, and B. Kellezi. 2022. Bystander responses to cyberbullying: The role of perceived severity, publicity, anonymity, type of cyberbullying, and victim response. Computers in Human Behavior 131: 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, C., M. A. Zanetti, and S. C. Caravita. 2023. Sex differences in cyberbullying behavior and victimization and perceived parental control before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 8, 1: 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E., and A. Nocentini. 2009. Cyberbullying definition and measurement: Some critical considerations. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 217, 4: 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E., A. Nocentini, and P. Calussi. 2011. The measurement of cyberbullying: Dimensional structure and relative item severity and discrimination. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14, 5: 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menken, M. S., A. Isaiah, H. Liang, P. R. Rivera, C. C. Cloak, G. Reeves, and L. Chang. 2022. Peer victimization (bullying) on mental health, behavioral problems, cognition, and academic performance in preadolescent children in the ABCD Study. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 925727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. R., and D. O. Davidshofer. 2005. Psychological testing: Principles and applications, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, R. 2016. Gender issues and cyberbullying in children and adolescents: From gender differences to gender identity measures. Cyberbullying Across the Globe: Gender, Family, and Mental Health, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. 1996. The revised olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Bergen: Research Center for Health Promotion, University of Bergen. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, D. 2013. School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 9: 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, B. E., E. Menesini, A. Nocentini, P. Luik, K. Naruskov, Z. Ucanok, and H. Scheithauer. 2017. Perceived severity of cyberbullying: Differences and similarities across four countries. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, I. K., and F. Petermann. 2018. Cyberbullying: A concept analysis of defining attributes and additional influencing factors. Computers in Human Behavior 86: 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S., S. Y. Lee, and S. H. Jung. 2017. Ethnic differences in bullying victimization and psychological distress: A test of an ecological model. Journal of Adolescence 60: 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Rivas, M. E., J. J. Varela, C. González, and M. J. Chuecas. 2022. The role of family support and conflict in cyberbullying and subjective well-being among Chilean adolescents during the Covid-19 period. Heliyon 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Abrio, A., B. Martínez-Ferrer, D. Musitu-Ferrer, C. León-Moreno, M. E. Villarreal-González, and J. E. Callejas-Jerónimo. 2019. Family communication problems, psychosocial adjustment and cyberbullying. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, 13: 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., and C. Frederick. 1997. On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality 65, 3: 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C., M. Sainio, and E. V. Hodges. 2013. Electronic victimization: Correlates, antecedents, and consequences among elementary and middle school students. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 42, 4: 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H., and A. Khamesan. 2025. A Serial Mediation Model of Perceived Social Class and Cyberbullying: The Role of Subjective Vitality in Friendship Relations and Psychological Distress. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry 20, 1: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H., A. Khamesan, and M. Mohammadzadeh. 2024. Bullying scales in educational contexts: A systematic review of two decades of research in Iran. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ) 13, 2: 47–58. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-5016-en.html.

- Shaheen, H., S. Rashid, and N. Aftab. 2023. Dealing with feelings: Moderating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies on the relationship between cyber-bullying victimization and psychological distress among students. Current Psychology 42, 34: 29745–29753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapka, J. D., and R. Maghsoudi. 2017. Examining the validity and reliability of the cyber-aggression and cyber-victimization scale. Computers in Human Behavior 69: 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatpanahi, G., K. Tahouri, M. Asadabadi, A. Moienafshar, M. Nazari, and A. Sayarifard. 2021. Cyberbullying and its contributing factors among Iranian adolescents. International Journal of High-Risk Behaviors and Addiction 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi Zadegan, M., M. Firoozi, A. Fattahi, S. Aleyasin, A. Soltan-Mohammadi, and Z. Naderi. 2024. The Psychometric Properties of the Persian Versions of the Cyberbullying Perpetration Questionnaire. Journal of Applied Psychological Research 15, 2: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkurina, A. 2024. Cyberbullying among Polish university students: Prevalence, factors, and experiences of cyberbullying and social exclusion. Procedia Computer Science 246: 5160–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sischka, P. E., J. P. Décieux, A. Mergener, K. M. Neufang, and A. F. Schmidt. 2022. The impact of forced answering and reactance on answering behavior in online surveys. Social Science Computer Review 40, 2: 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R., P. K. Smith, and A. Frisén. 2013. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior 29, 1: 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. K. 2015. The nature of cyberbullying and what we can do about it. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 15, 3: 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. K., J. Mahdavi, M. Carvalho, S. Fisher, S. Russell, and N. Tippett. 2008. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 49, 4: 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzberg, B. H., and G. Hoobler. 2002. Cyberstalking and the technologies of interpersonal terrorism. New Media & Society 4, 1: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department. 2022. Global number of bullying and harassment-related content taken action on by Facebook from 3rd quarter 2018 to 2nd quarter 2021(in millions). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1013569/facebook-bullying-and-harassment-content-removal-quarter/.

- Stewart, R. W., C. F. Drescher, D. J. Maack, C. Ebesutani, and J. Young. 2014. The development and psychometric investigation of the Cyberbullying Scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 29, 12: 2218–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J. 2012. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum associates, Vol. 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M., Z. Ma, B. Xu, C. Chen, Q. W. Chen, and D. Wang. 2024. Prevalence of cyberbullying involvement and its association with clinical correlates among Chinese college students. Journal of Affective Disorders 367: 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F., H. Kareshki, and M. Torkamani. 2019. Psychometric Properties of State Level Subjective Vitality Scale based on classical test theory and Item-response theory. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ) 8, 10: 79–88. https://frooyesh.ir/article-1-1590-en.html.

- Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F., H. Kareshki, M. Amani, S. Esfandyari, and M. Torkamani. 2020. Psychometric Properties of the Kessler psychological distress scale (K6) based on classical test theory and Item-response theory. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences 26, 11: 20–33. (In Persian). http://rjms.iums.ac.ir/article-1-5208-en.html.

- Tao, S., M. Lan, C. Y. Tan, Q. Liang, Q. Pan, and N. W. Law. 2024. Adolescents’ cyberbullying experience and subjective well-being: Sex difference in the moderating role of cognitive-emotional regulation strategy. Computers in Human Behavior 153: 108122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z., M. X. Zhao, Y. C. Yang, Y. Dong, and L. X. Xia. 2024. Reciprocal relationships between cyberbullying and loneliness among university students: The vital mediator of general trust. Personality and Individual Differences 221: 112567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, T., M. T. Elhady, S. Rashed, M. Abdelkhalek, S. A. Nasef, A. M. Khallaf, and N. T. Huy. 2018. Quality of reporting web-based and non-web-based survey studies: What authors, reviewers and consumers should consider. PLoS ONE 13, 6: e0194239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R. M., A. Gireesh, N. Stiglic, L. D. Hudson, A. L. Goddings, J. L. Ward, and D. E. Nicholls. 2019. Roles of cyberbullying, sleep, and physical activity in mediating the effects of social media use on mental health and wellbeing among young people in England: A secondary analysis of longitudinal data. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 3, 10: 685–696. [Google Scholar]

- Willard, N. E. 2007. Cyberbullying and cyberthreats: Responding to the challenge of online social aggression, threats, and distress. Research press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. R., and N. G. Guerra. 2007. Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 41, 6: S14–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., S. Li, L. Gao, and X. Wang. 2022. Longitudinal associations among peer pressure, moral disengagement and cyberbullying perpetration in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior 137: 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsila, Á., R. Urbán, M. D. Griffiths, and Z. Demetrovics. 2019. Gender differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and perpetration: The role of anger rumination and traditional bullying experiences. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 17: 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).