1. Introduction

1.1. Cybervictimization as a Predictor of Cyberbullying Perpetration

In recent decades, Western countries have faced the spread of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and of social media applications [

1]. Regardless of the cultural context, Western societies have witnessed an increase in the number of individuals connected to the Internet daily, for work, social, educational, or recreational activities [

2]. Through digital devices, preadolescents engage in both positive and negative behaviors and habits, encountering opportunities and risks previously beyond reach [

3].

Among the risks associated with problematic Internet and social media platforms use in preadolescence, is cyberbullying, a vast social problem progressively studied in recent decades as a digital evolution of traditional bullying [

4]. Cyberbullying perpetration is defined «as the use of digital technologies to harass, intimidate, or embarrass others» [

5], and represents a current global issue among schoolchildren and adolescents [

6]. Cyberbullying perpetration is a prevalent issue in the daily lives of many preadolescents worldwide. Authors reviewed multiple studies and determined that the average annual rate of cybervictimization ranges from 14% to 21% [

7]. On a global scale, between 10% and 72% of youths have reported experiencing cyberbullying [

8]. These alarming rates are associated with severe consequences for victims, including mental health issues, social development difficulties, and diminished self-esteem [

9,

10]. Additionally, cybervictimization refers to being harmed or mistreated via electronic communication technologies such as the Internet, social media platforms, encompassing aggression, harassment, or intimidation perpetrated online [

11], and expresses in multiple forms, including harassment, impersonation, stalking, or spreading malicious rumors or images [

12]. It may cause emotional distress, psychological harm, and general long-term negative consequences for victims’ personality development [

13].

In the European context, the prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization among young individuals have garnered increasing attention progressively, shedding light on the scope of the issue within this diverse setting in which multiple cultures participate. Italy and Spain, as evidenced by the proliferation of studies on the topic [

14], are among the European countries most affected by these social mechanisms. In the 2022 HBSC Italian survey, 94,178 children aged 11, 13, 15 and 17 completed the questionnaire, distributed throughout all regions; 6,388 classes were sampled. In the 11-year age group, 17.2% of males and 21.1% of females have been identified as victims of cyberbullying; 12.9% of boys and 18.4% of girls were victims of cyberbullying perpetration; 9.2% of boys and 11.4% of girls were reported to be victims in the 15-year age group. The survey reports that in families, as age increases, the ease with which boys open to their parents decreases; 13- and 15-year-old girls, compared to boys of the same age, find it more difficult to talk to their father figure. In 2022, 31% of minors were cybervictims at least once, compared to 23 % in 2020. In Spain, a systematic review of the literature including 21 studies revealed that, since 2010, the median perpetration of cyberbullying in Spain was 24.64%, and a median cybervictimization prevalence of 26.65% [

15,

16].

Developmental research dealt with the link between cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization, revealing their bidirectional association [

17]. Globally, most cybervictimized preadolescents subsequently suffer from mental health issues, including increased stress and the adoption of maladaptive coping strategies [

18]. Further research indicates that individuals who experience aggression in the form of cybervictimization are more likely to engage in cyberbullying perpetration themselves [

19]. This phenomenon can be understood through the lens of the “cycle of violence” theory, which suggests that victims of aggression may resort to aggressive behaviors as a coping mechanism or to regain a sense of control and power [

20], suggesting that cybervictimization experiences can be viewed as situational factors triggering negative emotional responses, such as anger or distress [

21]. Relatively few studies have examined the group that encompasses those who are both victims of cyberbullying and perpetrators (i.e., cyberbully-victims) [

22]. In the digital context, the anonymity and perceived detachment provided by online interactions can exacerbate this cycle, making it easier for victims to become perpetrators without immediate social repercussions [

23]. Additionally, factors such as emotional distress, social isolation, and the desire for revenge can drive cybervictimized preadolescents to cyberbully others [

24]. Understanding this link is crucial for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies that address both the needs of victims and the motivations behind perpetration, ultimately aiming to break this detrimental cycle and promote healthier online interactions among preadolescents [

25].

Nowadays, the continued proliferation of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) worldwide has affected numerous aspects of human activities, presenting opportunities and risks [

26], particularly for preadolescents, increasingly absorbed in daily Internet and social media platforms use for multiple purposes [

27]. Among these possible risks, problematic social media and Internet use have progressively emerged as potentially impairing pressing public health concerns across numerous Western countries, due to their impact on preadolescents’ social development processes [

28,

29]. Within this landscape, negative online experiences, such as cybervictimization and cyberbullying, have become common negative forms of online social interactions among peers, posing significant risks to their well-being [

30,

31].

Building upon prior research [

32], the current study posits that cybervictimization in preadolescence might serve as a precursor to cyberbullying perpetration, reflecting the cyclical nature of online aggression [

33]. In the context of cyberbullying experiences, victims are often driven by a personal need to regain control or seek revenge on the bully, retaliate by becoming perpetrators themselves [

34]. Therefore, cybervictimization experiences might significantly increase the likelihood of individuals engaging in subsequent cyberbullying perpetration, thereby perpetuating a potentially vicious cycle of online aggression, intensifying the psychological distress experienced by both victims and perpetrators [

35]. This study aims at uncovering the underlying processes involved in the cybervictimization-cyberbullying perpetration link in preadolescence, introducing the serial mediating action played by problematic social media use and moral disengagement.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

The General Aggression Model (GAM) is a theory describing how personal and situational factors could interact to affect an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, leading to aggression conduct [

36]. According to the model, aggressive behaviors are the result of complex interactions between situational variables (e.g., provocation, exposure to violent media) and individual differences (e.g., personality traits, past experiences), which influence cognitive (e.g., aggressive thoughts), affective (e.g., anger), and arousal states. These internal states, in turn, might affect decision-making processes, which can result in aggressive or non-aggressive behaviors depending on the context and individual’s control over their responses [

37].

The GAM offers a comprehensive framework for understanding cyberbullying among preadolescents, integrating individual-specific and situational factors [

38]. Specifically, the model suggests that experiences of cyberbullying alter an individual’s state, prompting aggressive behaviors. Cybervictimization serves as a situational trigger, catalyzing cyberbullying, and aversive events activate hostile attitudes, leading to aggressive impulses, which are potent situational triggers [

39].

While many studies have examined the relationship between traditional bullying and cyberbullying and the influence of factors like gender, emotional problems, depression, and anxiety [

40], the underlying mechanisms mediating cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration remain still unclear. The GAM, addressing both person-specific and situation-specific factors, provides a valuable lens to explore these mechanisms. Within the GAM, PSMU and MD might be interpreted as serial mediating factors in the cyberbullying perpetration-cybervictimization link, providing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which cybervictimization leads to perpetration of cyberbullying in preadolescence. The proposed pathway suggests that experiencing cybervictimization may elevate PSMU, leading to a maladaptive interaction with social platforms. The study introduces PSMU as a mediator between CV and CB, a behavioral pattern that typically develops over a longer period. This, in turn, can encourage MD processes, by which people distance themselves from feelings of guilt or moral responsibility. These cognitive self-regulatory strategies eventually pave the way for engaging in cyberbullying behaviors, reinforcing the cycle of online aggression [

41].

1.3. The Mediating Role of Problematic Social Media Use

Preadolescents are a vulnerable age group identified between the years 9 and 14 [

42], in which the brain is still developing, and social relationships are essential for a positive development [

43]. As contemporary preadolescents grow up using digital tools and social media platforms from an early age, they are today faced both with opportunities for socialization, learning, and entertainment [

44], and risks, such as Problematic social media use (PSMU), exposure to inappropriate contents, problematic online gaming, social anxiety, or isolation [

45,

46]. PSMU refers to the excessive or maladaptive individual patterns of engagement with social media platforms, characterized by withdrawal symptoms, mood modification, and conflict [

47]. Thus, ICTs and social media platforms can foster social connections and provide platforms for self-expression and creativity [

48]. They enable young people to access vast amounts of information, collaborate on educational projects, and build supportive online communities [

49].

In this study, we adopted the term PSMU over “social media addiction” to avoid controversies, since the latter is not officially recognized as a disorder in the DSM-5 [

50]. This decision aligns with current literature, which distinguishes between problematic usage patterns and clinically diagnosable addiction [

51]. For some individuals, this problematic habit can become a dominant activity in their lives, causing preoccupation (salience) and using social media to alter mood or induce pleasurable feelings (mood modification). Over time, more engagement is needed to achieve the same effects (tolerance) and discontinuing use can result in negative psychological and sometimes physiological symptoms (withdrawal), often leading to relapse. This problematic use can cause internal conflicts, such as a loss of control, and external conflicts, including relationship and academic or work problems [

52]. In the context of cyberbullying research, PSMU might play a mediating role in the cybervictimization-cyberbullying perpetration link for several reasons. Preadolescents who are frequently online may be more likely to encounter aggressive behaviors or become targets of harassment [

53]. Moreover, PSMU can impair emotional regulation and coping mechanisms, making it more difficult for victims to manage the distress caused by cybervictimization experiences [

54]. This emotional turmoil can lead some victims to engage in retaliatory aggression as a maladaptive coping strategy, thereby perpetuating the cycle of cyberbullying [

55]. Additionally, PSMU involves seeking validation and social approval, which can exacerbate feelings of rejection and isolation when victimized, potentially leading to aggressive behaviors to regain control and social standing [

56]. Thus, the compulsive nature of PSMU can both increase the likelihood of experiencing cybervictimization and heighten the propensity to respond with cyberbullying behaviors [

57]. In the context of the GAM, PSMU might be viewed as a personal maladaptive situational experience triggered both from the environment and individual variables, further leading to social negative online behaviors, such as cyberbullying perpetration. Thus, the role of PSMU in the CV-MD-CB link reflects its capacity to both drive the progression of harmful online behaviors and amplify the impact of underlying moral attitudes, highlighting the importance of addressing PSMU in interventions aimed at reducing cyberbullying among preadolescents.

1.4. The Mediating Role of Moral Disengagement

Moral disengagement (MD) entails the cognitive self-regulatory mechanisms that allow individuals to rationalize or justify harmful behaviors, thereby alleviating feelings of guilt or moral responsibility, through cognitive restructuring, diffusion of responsibility, or euphemistic labeling [

58]. Strategies of moral disengagement can occur in multiple contexts, including cyberbullying episodes among preadolescents, where perpetrators may practice rationalizations, such as advantageous comparison, minimizing the harm caused, or using social comparison to justify their behaviors [

59]. In the context of cyberbullying perpetration, moral disengagement is defined as “an influence on traditional bullying and cyberbullying cognitive process, by which a person justifies his/her harmful or aggressive behavior, by loosening his/her inner self-regulatory mechanisms […] which usually keeps behavior, in line with personal standards” [60, p. 81]. Regarding social online behaviors in preadolescence, moral disengagement mechanisms can contribute to the perpetration of a wide range of antisocial actions [

61]. Cyberspace grants anonymity and reduced accountability, making it easier for individuals to engage in cyberbullying and aggressive online actions without facing any consequence [

62], or to retaliate against perpetrators of online aggressions. Moral disengagement enables individuals to justify actions and disregard ethical implications of behaviors: “the advent of the Internet ushered in a ubiquitous vehicle for disengaging moral self-sanctions from transgressive conduct. The Internet was designed as a highly decentralized system that defies regulation. Anybody can get into the act, and nobody is in charge” [63, p. 68].

Building on previous research, in the current study moral disengagement is proposed as a serial mediating factor between cybervictimization, PSMU and cyberbullying perpetration, offering crucial insights into their interconnectedness [

64]. It may act as a link between PSMU and cyberbullying perpetration, suggesting that heightened PSMU might lead to the adoption of moral disengagement mechanisms, which in turn might more likely be associated with cyberbullying perpetration. MD involves cognitive restructuring and justifications to disengage from moral standards, allowing individuals to rationalize their harmful actions. These strategies, while coping with guilt or self-blame momentarily, might lead to perpetuating negative behaviors on others in cyberspace [

65]. Preadolescents might experience reduced self-awareness and restraints, fueling moral disengagement and, subsequently, influencing cyberbullying and cybervictimization dynamics. Within the GAM, moral disengagement processes might play a role in the individual desensitization that facilitates the perpetration of harmful online actions, in cybervictims and young problematic social media users.

1.5. The Current Study

The current study investigates online social behaviors and psychological characteristics in Italian and Spanish preadolescents, linking cybervictimization, PSMU, MD, and cyberbullying perpetration. Moreover, a serial mediating model testing the serial indirect effect of PSMU and MD on the association between cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration has been examined. The complex relationship is explored in a cross-national sample of Italian and Spanish preadolescents. We were interested in exploring the following research questions:

RQ1: How is cybervictimization associated to cyberbullying perpetration among Italian and Spanish preadolescents?

RQ2: Is this relationship mediated by the serial indirect effect of PSMU and MD in both samples?

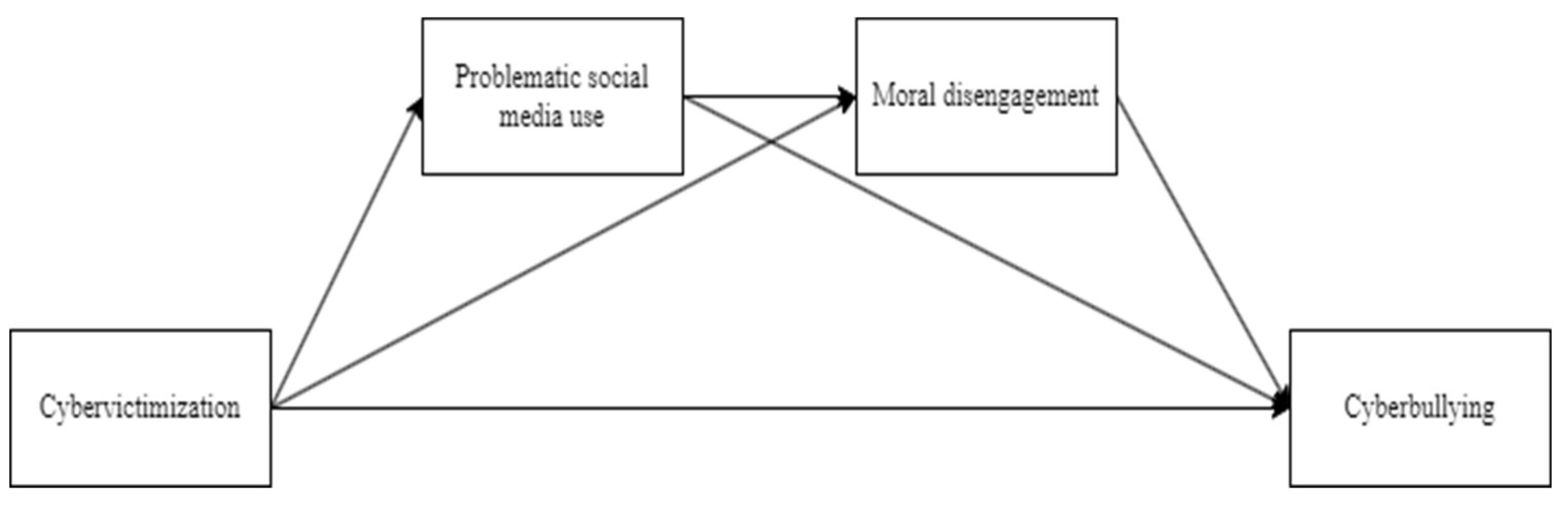

As serial mediating factors, PSMU and MD may contribute to the perpetration of cyberbullying by facilitating negative and aggressive online interactions among peers, providing a platform for anonymity and disinhibition, and amplifying peer influence dynamics (see

Fig. 1). Thus, understanding the serial mediating roles of PSMU and MD is crucial for designing effective preventive interventions aimed at mitigating the negative impact of cyberbullying and cybervictimization among preadolescents.

Among the numerous risk factors associated with cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration in preadolescents, it is worth investigating the intricate interplay of PSMU and MD within the context of negative online interactions among peers, due to their pervasive influence in preadolescents’ social behaviors [

66,

67]. Understanding the dynamics between these variables in the link between cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration is essential for unraveling the processes that might enhance the cycle of negative online interactions among preadolescents [

68]. Previous research conducted in Italy and Spain [

69,

70] highlights both sociocultural similarities and differences between the two countries regarding cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Given these parallels and distinctions, as well as comparable educational contexts [

71], further investigation into the perpetuation of online aggression is crucial.

The hypotheses under investigation in this cross-national study are the following: (i) cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration present a direct association in a cross-national sample of Italian and Spanish preadolescents; (ii) problematic social media use and moral disengagement serially mediate the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration in Italian and Spanish preadolescents.

These hypotheses are grounded in several compelling reasons. Firstly, the literature shows that PSMU has been linked to negative online behaviors among preadolescents, including cyberbullying, suggesting that individuals who engage in PSMU patterns may be more prone to experience cybervictimization or perpetrate cyberbullying [

72,

73]. Moreover, moral disengagement mechanisms, that enable individuals to justify or excuse antisocial actions, may play a crucial role in facilitating the transition from cybervictimization to cyberbullying perpetration by attenuating online moral inhibitions and increasing the likelihood of engaging in aggressive behaviors against peers [

74,

75]. The decision to employ a serial mediation model, wherein problematic social media use precedes moral disengagement in the direct relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration, stems from theoretical considerations and is supported by existing literature, presenting a novel aspect of the current study [

76]. PSMU might lead to a negative engagement with social media platforms, potentially leading to the frequent adoption of dysfunctional social and cognitive attitudes and behaviors in daily life [

77]. Previous research suggests that prolonged and passive use of social media applications may contribute to the development of negative attitudes and behaviors, including moral disengagement mechanisms [

78], exacerbating the scope and negative consequences of the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying. This approach tentatively addresses a gap in the literature concerning the interplay of PSMU and MD within the social dynamics of experiencing and perpetrating cyberbullying during preadolescence.

Lastly, the cross-national analysis involving Italy and Spain is motivated by the scientific urge to comprehend the psychosocial characteristics of online social behaviors among Italian and Spanish preadolescents [

79], given that past studies highlighted similar trends regarding cyberbullying, and related factors levels in these two countries [

80,

81]. By delineating these relationships in the current cross-national study involving Italian and Spanish preadolescents, tailored interventions to target specific risk factors and promote healthier online behaviors within a European policy framework, ultimately fostering a safer and more positive digital environment for young individuals can be proposed [

82].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Through a self-report survey, levels of cybervictimization, PSMU, MD, and cyberbullying perpetration were assessed in a sample of Italian and Spanish preadolescents (N = 895, 54.6% Italian participants), aged 9 – 14 (M = 11.23, SD = 1.064) (see

Table 1).

The study and the procedures were conducted according to the criteria of the Ethics Committee of the University, Prot. no. 0010986 of 02/13/2023. In Spain, the study and procedures were preliminary approved by the research team and by the doctoral committee of the University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. In Italy, the participants were contacted after selecting thirty-one classes in schools in the region of Calabria, willing to participate. Both in Italy and Spain, the schools were selected by a search database, where a list of local school institutions was stored, and persuaded to join in the investigation through a motivation letter to the school-principals, introducing the purposes of the study. After obtaining permission from the corresponding school principals, the participants’ parents were informed by letter about the purpose of the research, the voluntary nature of participation and the anonymity of responses. Parents provided informed consent for their son or daughter’s participation. In addition, participants provided signed assent agreeing to take part in the study. Italian and Spanish research assistants collected the data after providing a general description of the research aims and measures (defining what social medias are, and what cyberbullying is in terms of aggression and victimization). Participants had about 30 minutes to complete a self-report survey during class time and could withdraw at any moment.

2.2. Measures

The participants completed a self-report questionnaire containing a set of different measures. For the purposes of this study, only some of these measures were considered.

Sociodemographic information was collected such as gender, age and Internet and social media platforms frequency of use and habits among the participants.

Problematic Social Media Use was assessed using the Italian [

83] and Spanish version [

84] of the

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS). The BSMAS is a 6-item self-report measure that assesses addictive behaviors related to social media use, such as withdrawal symptoms, mood modification, and conflict (e.g., “You spend a lot of time thinking about social media or planning how to use it.”). Participants rated each item on a Likert scale from 1 (

very rarely) to 5 (

very often), with higher scores indicating higher levels of social media addiction (Italian sample: Cronbach’s α = .719; Spanish sample: Cronbach’s α = .760).

Moral Disengagement was measured using the adolescent Italian [

85] and Spanish version [

86] of the

Moral Disengagement Scale (MDS). The scale is a 24-item self-report measure that assesses cognitive mechanisms that allow individuals to justify or excuse their harmful behaviors (e.g., “It is alright to fight to protect your friends.”). Participants rated each item on a Likert scale from 1 (

not at all) to 5 (

very much), with higher scores indicating higher levels of moral disengagement (Italian sample: Cronbach’s α = .839; Spanish sample: Cronbach’s α = .806). Given confirmation from prior studies of the internal consistency of the single factor structure of the scale [

87], a total mean score was calculated for moral disengagement.

Cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization were measured through the

European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIP-Q) in its Italian [

88] and Spanish version [

89]. The ECIP-Q is a 22-item self-report measure, with the former 11 items measuring victimization and the latter 11 measuring aggressions, that assesses the frequency and severity of cybervictimization and cyberbullying behaviors in the past two or three months, such as spreading rumors, posting mean comments (e.g., “I altered pictures or videos of another person that had been posted online.”), or excluding others from online groups or stealing someone’s identity and personal information (e.g., “Someone created a fake account, pretending to be me.”). Participants rated each item on a Likert scale from 1 (

never) to 5 (

several times a week), with higher scores indicating higher levels of cybervictimization (Italian sample: Cronbach’s α = .846; Spanish sample: Cronbach’s α = .830) and cyberbullying (Italian sample: Cronbach’s α = .853; Spanish sample: Cronbach’s α = .616).

2.3. Analysis Procedure

The statistical analyses were conducted in four steps using IBM SPSS 27.0. First, descriptive analyses (means and standard deviations) were computed, alongside t-tests for independent samples to examine gender differences. Effect sizes were measured adopting Cohen’s d, providing a clearer understanding of gender influences on the variables. Second, Pearson bivariate correlations were analyzed to explore potential relationships between the key variables. Third, a serial mediation analysis (using SPSS Process macro v.27.0, Model 6) [

90] examined whether problematic social media use (PSMU) and moral disengagement (MD) serially mediated the association between cybervictimization (CV) and cyberbullying (CB). This approach utilized bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples, allowing for more accurate confidence intervals and reducing the risk of type I errors. The mediation analysis also assessed the total effect and proportion mediated (P M) to gauge the indirect effect’s contribution.

A significant effect is indicated when the confidence intervals do not encompass zero. Previous studies found that gender was associated with cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization [

91,

92,

93]. Thus, this variable was included as a covariate in all analyses. Gender was dichotomous (

0 = female, 1 = male, 2 = I prefer not to answer, 3 = other). Additionally, age and nationality were also included as covariates to account for their potential influence on the variables’ outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

In

Table 1, descriptive statistics of the variables are reported both for Italian and Spanish preadolescents, showing low levels of cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration. A van der Waerden’s data ranking transformation on the kurtosis and skewness values of cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration was applied, due to their excessively high magnitudes. This transformation aimed to normalize the distribution and mitigate the extreme values observed in these variables.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the independent samples t-test conducted on the investigated variables, categorized by gender.

The results indicate no statistically significant mean differences across the variables when comparing gender groups, with most effect sizes reflected by small to medium Cohen’s d values. This suggests that, in general, gender did not play a significant role in differentiating levels of problematic social media use, cybervictimization, or cyberbullying. However, the analysis revealed that moral disengagement was the only variable to show a medium effect size (Cohen’s d), hinting at some degree of gender-related variance. This finding may imply that males and females slightly differ in how they rationalize or justify aggressive behaviors online, warranting further investigation.

Table 3 summarizes the results from the bivariate correlations among the variables, indicating strong positive correlations between all investigated variables. Notably, PSMU presented strong correlations with MD, CV and CB, and CV presented a strong positive correlation with CB.

3.2. Mediation Model

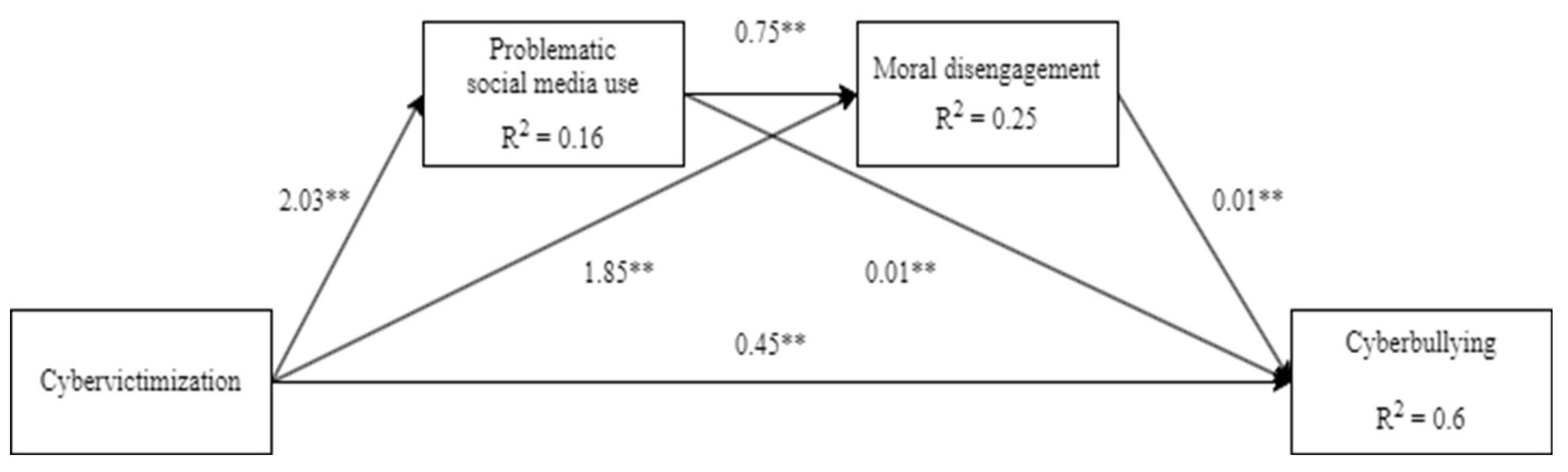

Mediation analysis was performed to explore the serial mediating role of PSMU and MD in the association between cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration. The results (

Table 4) reveal a significant total effect of CV on CB perpetration (β = .071, SE = .013, 95% CI [.045; .098]), indicating that higher levels of CV are associated with increased CB perpetration.

Furthermore, PSMU and MD serially mediate this relationship, showing strong positive associations. Specifically, CV significantly predicts PSMU (β = .35, 95% CI [1.68; 2.38]), which in turn predicts MD (β = .28, 95% CI [.59; .93]). MD subsequently predicts CB perpetration (β = .14, 95% CI [.004; .011]), demonstrating that PSMU and MD play crucial roles in the pathway from CV to CB. The results highlight a significant indirect effect of PSMU and MD on the cybervictimization-cyberbullying perpetration link (H2: Problematic social media use and moral disengagement serially mediates the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying, such that higher levels of cybervictimization lead to higher levels of problematic social media use and moral disengagement, which in turn lead to higher levels of cyberbullying perpetration, both in Italy and Spain).

In the mediation model, cybervictimization positively predicted PSMU, MD, and cyberbullying. Further, both PSMU and MD presented statistically significant indirect serial effects in the cybervictimization-cyberbullying association. The results show that PSMU and MD positively and partially mediated the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration (see

Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

This study aimed (1) to examine the associations between CV, PSMU, MD and CB perpetration in a sample of Italian and Spanish preadolescents, and (2) to examine the serial mediating action of PSMU and MD on the CV-CB link.

In line with H1 (the levels of the investigated variables align with the literature), the results reveal that the computed scores for the variables in the sample mirror findings from previous studies [

70]. These findings reinforce the understanding of cyberbullying as a potential global concern for preadolescents, emphasizing the significant roles of cybervictimization and problematic social media use both in Italy and Spain. From the perspective of the General Aggression Model, various situational and individual factors, such as problematic social media use and moral disengagement, intensify negative online behaviors among preadolescents [

94]. These variables contribute to the exacerbation of aggressive tendencies, making them central to understanding the complex interplay between victimization and perpetration in online peer interactions [

95]. By capturing these dynamics in both Italian and Spanish contexts, the study offers a robust cross-national perspective on the cyclical nature of online aggression, highlighting how these factors shape harmful social media interactions among preadolescents. Moreover, the significant positive correlations observed among the variables further underscore the risks associated with negative online engagement and the potential harm to preadolescents’ online social relationships. The increasing integration of social media applications’ use in preadolescents’ daily life worldwide amplifies the likelihood of cybervictimization, especially among those heavily engaged with these platforms [

96]. These findings highlight the need for targeted prevention and intervention strategies to mitigate these risks. Through the General Aggression Model (GAM), these correlations emphasize the importance of situational factors, such as nationality and age, in shaping cyberbullying experiences. Addressing such issues requires early identification and tailored support, particularly in regions with heightened exposure to digital media.

The results from the mediation analysis provide empirical evidence supporting the serial mediation model, confirming H2 (problematic social media use and moral disengagement serially mediate the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying, such that higher levels of cybervictimization lead to higher levels of problematic social media use and moral disengagement, which in turn lead to higher levels of cyberbullying, both in Italy and Spain). PSMU and MD serially mediate the relationship between CV and CB in both Italy and Spain. Specifically, the findings reveal that experiencing cybervictimization might promote a problematic engagement with social media application in Italian and Spanish preadolescents, which in turn could increase moral disengagement tendencies, ultimately leading to higher levels of cyberbullying perpetration. This cyclical pathway underscores the role of PSMU in amplifying MD, illustrating that a broader negative engagement with social media platforms strengthens the risk of adopting morally disengaged behaviors that justify harmful online actions [

97]. The model fitting within the GAM framework demonstrates that cybervictimization might act as a situational factor that might trigger self-regulatory cognitive and emotional changes in preadolescents, making them more likely to engage in maladaptive social media use [

98]. This increased social media platforms’ use might provide fertile ground for developing MD mechanisms, where preadolescents may justify or excuse their own aggressive actions. This, in turn, perpetuates the cycle of cyberbullying, especially for those already victimized online [

99]. The stronger indirect effects at higher levels of PSMU further confirm that frequent and problematic use of social media strengthens aggressive scripts and attitudes, leading to a higher likelihood of cyberbullying [

100]. The cross-national aspect of the study, involving Italian and Spanish preadolescents, highlights the generalizability of these findings across different contexts. Despite similarities between these countries, such as language and cultural values, variations like the policy differences in smartphone use at schools can affect the intensity and frequency of social media platforms engagement, and thus, online behaviors. The serial mediation link identified in both contexts reinforces that national variations do not diminish the robust effect of PSMU and MD on cyberbullying perpetration.

According to the GAM, aggression is the result of a complex interaction between individual and situational variables [

101]. In this study, PSMU and MD might represent situational inputs and person-specific factors that influence the internal state of Italian and Spanish preadolescents, triggering aggressive responses like cyberbullying. The results from the study reinforce the GAM’s premise that while situational factors (e.g., cybervictimization) are critical in initiating aggression, the long-term perpetuation of these behaviors is deeply rooted in personal and cognitive factors (e.g., moral disengagement) amplified by external stimuli (such as problematic engagement with social media) [

102]. These results point to the importance of addressing both environmental (e.g., regulation of social media use) and cognitive (e.g., moral reasoning) factors in intervention strategies, supporting GAM’s multifaceted approach to understanding aggression.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the study contribute to the literature on cyberpsychology, extending the knowledge on the risk factors connected to cyberbullying suffering and perpetration in European preadolescents. Specifically, our investigation of the serial mediating action played by both PSMU and MD in the association between cybervictimization and cyberbullying perpetration contributes to amplifying the scope of the mechanisms involved in this pervasive social problem. Also, the results underscore the need for a common European policy framework promoting guidance on responsible and pro-social digital literacy citizenship, to prevent cyberbullying and negative online social experiences in preadolescence. By providing research insights to inform tailored interventions, the study aims to promote a safer online environment and enhance the well-being of Italian and Spanish preadolescents. This research is cross-nationally significant, contributing to the understanding of cyberbullying within the Italian and Spanish context and guiding evidence-based strategies to address its impacts. The serial mediation model illuminates how PSMU and MD jointly mediate the pathway from cybervictimization to cyberbullying, offering a nuanced understanding of these dynamics. The cross-national nature of the sample strengthens the study’s relevance, demonstrating that despite slight cultural variations, such as smartphone policies in schools, the core relationships between these variables persist across contexts. This research underscores the importance of culturally tailored intervention strategies targeting online behaviors and cognitive distortions early in preadolescence. Its findings can inform the development of preventive measures and policies in schools, both within Europe and internationally, thereby expanding the scope of cross-cultural cyberbullying research.

In sum, this research emphasizes the critical role of PSMU and MD in the cycle of cyberbullying, particularly for those who have experienced cybervictimization, and highlights how interventions targeting social media applications use and cognitive self-regulation could break the escalation of online aggression across different European contexts. This work moves the field of cyberpsychology forward by highlighting the need for comprehensive interventions that address behavioral and cognitive factors contributing to cyberaggression, stressing the critical period of preadolescence for prevention efforts. It also emphasizes the importance of cross-national research, showcasing how country-specific factors, such as school policies, shape online behaviors in distinct yet comparable ways. Through this, the study advocates for European policies to effectively address cyberbullying.

6. Limitations and Further Research

This study’s reliance on self-report data introduces possible biases such as social desirability and recall bias, which could affect the accuracy of participants’ responses. One significant limitation of the present study lies in its reliance on cross-sectional data to test a serial mediation model, which inherently assumes causal relationships between variables. While mediation analysis is a useful statistical technique, it does not allow robust testing of causality when bidirectional and simultaneous influences likely exist among the variables. Specifically, in the relationship between CV and CB, there is strong theoretical justification for conceptualizing cybervictimization as a situational trigger that elicits impulsive aggressive behaviors, a mechanism often observed in aversive situations where hostile attitudes are activated. This view suggests a more immediate, reactive link between CV and CB. The role of PSMU may create tension within the hypothesized temporal sequence, as impulsive aggressive behaviors theoretically contradict the sustained behavioral engagement associated with PSMU. However, the model and relationships tested, and the results obtained confirm similar results obtained from longitudinal studies on these variables [

32]. Despite these challenges, the present study sought to address this complex relationship in a novel way by exploring PSMU as a mediating mechanism in a cross-national sample of Italian and Spanish preadolescents. While causal claims cannot be made, this approach sheds light on potential underlying processes that link victimization and perpetration, emphasizing PSMU’s pervasive role in shaping digital interactions. By comparing two European cultural contexts, the study offers insights into shared and unique dynamics among preadolescents in both countries, providing a foundation for future longitudinal research to better disentangle the temporal and bidirectional relationships between CV, PSMU, and CB.

Another significant limitation is the cross-national nature of the sample, drawn from Italy and Spain. Despite their geographic proximity, these countries exhibit differences in school policies, notably the use of smartphones. In Spain, smartphones are banned in schools, which may influence the frequency and context of problematic social media use, compared to Italy, where more permissive policies exist. These differences could affect how students interact with social media, potentially shaping their experiences of cybervictimization, moral disengagement, and cyberbullying differently. Cultural factors like norms around technology use and educational practices were not directly measured, limiting the understanding of how contextual factors influence the findings. Furthermore, the use of Likert scales to measure complex constructs such as moral disengagement might not fully capture the depth and variability of this phenomenon, raising concerns about the precision of measurement. Future research should explore longitudinal designs to understand the evolving nature of these relationships over time and include a broader cultural range to enhance the generalizability of the findings. The role of external factors such as family dynamics, peer interactions, and specific national policies surrounding technology use should be further investigated as potential moderators in understanding cyberbullying behavior. Future studies should consider incorporating more situational variables within the GAM framework to better capture the nuances of online aggression and its prevention in various cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Literature review, G.M.C; Writing-original draft preparation, G.M.C.; Conceptualization, R.C.S., A.L.P., M.G.B., and E.R.F..; Methodology, G.M.C., R.C.S., A.L.P., M.G.B., and P.G.C.; Software, G.M.C., and R.C.S.; Collection data, G.M.C., A.L.P., M.G.B., and P.G.C.; Writing-review and editing, G.M.C., A.L.P., M.G.B., P.G.C., R.O.R., and E.R.F.; Formal analysis, G.M.C., R.C.S., and P.G.C.; Supervision, R.O.R., and E.R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Calabria (protocol code Prot. no. 0010986 of 02/13/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, their parents, and school principals.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tsitsika, A. K., Tzavela, E. C., Janikian, M., Ólafsson, K., Iordache, A., Schoenmakers, T. M., ... & Richardson, C. (2014). Online social networking in adolescence: Patterns of use in six European countries and links with psychosocial functioning. Journal of adolescent health, 55(1), 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D. J., Kristensen, A. M., & Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2021). Internet addictions outside of Europe: A systematic literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 106621. [CrossRef]

- Lahti, H., Kulmala, M., Lyyra, N., Mietola, V., & Paakkari, L. (2024). Problematic situations related to social media use and competencies to prevent them: results of a Delphi study. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 5275. [CrossRef]

- Giumetti, G. W., & Kowalski, R. M. (2022). Cyberbullying via social media and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101314. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. K. (2012). Cyberbullying: Challenges and opportunities for a research program—A response to Olweus (2012). European journal of developmental psychology, 9(5), 553-558. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S. (2019). EU kids online. The international encyclopedia of media literacy, 1-17.

- Ansary, N. S. (2020). Cyberbullying: Concepts, theories, and correlates informing evidence-based best practices for prevention. Aggression and violent behavior, 50, 101343. [CrossRef]

- Cosma, A., Walsh, S. D., Chester, K. L., Callaghan, M., Molcho, M., Craig, W., & Pickett, W. (2020). Bullying victimization: Time trends and the overlap between traditional and cyberbullying across countries in Europe and North America. International journal of public health, 65, 75-85. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological bulletin, 140(4), 1073. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0035618.

- Palermiti, A. L., Bartolo, M. G., Musso, P., Servidio, R., & Costabile, A. (2022). Self-esteem and adolescent bullying/cyberbullying and victimization/cybervictimization behaviours: A person-oriented approach. Europe's journal of psychology, 18(3), 249. [CrossRef]

- Yildiz Durak, H., & Saritepeci, M. (2020). Examination of the relationship between cyberbullying and cyber victimization. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 2905-2915. [CrossRef]

- Viau, S. J., Denault, A. S., Dionne, G., Brendgen, M., Geoffroy, M. C., Côté, S., ... & Boivin, M. (2020). Joint trajectories of peer cyber and traditional victimization in adolescence: A look at risk factors. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(7), 936-965. [CrossRef]

- Sidera, F., Serrat, E., & Rostan, C. (2021). Effects of cybervictimization on the mental health of primary school students. Frontiers in public health, 9, 588209. [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A., Obregón-Cuesta, A. I., Di Petrillo, E., Moscato, E. M., Fernández-Solana, J., Caggiano, V., & González-Bernal, J. J. (2023). Intercultural differences between Spain and Italy regarding school bullying, gender, and age. Children, 10(11), 1762. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. M., Fatima, Y., Cleary, A., McDaid, L., Munir, K., Smith, S. S., ... & Mamun, A. (2023). Geographical variations in the prevalence of traditional and cyberbullying and its additive role in psychological and somatic health complaints among adolescents in 38 European countries. Journal of psychosomatic research, 164, 111103. [CrossRef]

- Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Marín-López, I. (2016). Cyberbullying: a systematic review of research, its prevalence and assessment issues in Spanish studies. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Leung, A. N. M., Wong, N., & Farver, J. M. (2018). Cyberbullying in Hong Kong Chinese students: Life satisfaction, and the moderating role of friendship qualities on cyberbullying victimization and perpetration. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 7-12. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Blasco, R., Cortés-Pascual, A., & Latorre-Martínez, M. P. (2020). Being a cybervictim and a cyberbully–The duality of cyberbullying: A meta-analysis. Computers in human behavior, 111, 106444. [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, L. (2024). Cyberbullying: a new dimension to an old problem (Doctoral dissertation, Institute of Art, Design+ Technology).

- Falla, D., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Runions, K., & Romera, E. M. (2022). Why do victims become perpetrators of peer bullying? Moral disengagement in the cycle of violence. Youth & Society, 54(3), 397-418. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M., & Antoniadou, N. (2019). Cyber-bullying and cyber-victimization among undergraduate student teachers through the lens of the General Aggression Model. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 59-68. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Romera, E. M. (2021). Longitudinal associations between cybervictimization, anger rumination, and cyberaggression. Aggressive behavior, 47(3), 332-342. [CrossRef]

- Sechi, C., Cabras, C., & Sideli, L. (2023). Cyber-victimisation and cyber-bullying: the mediation role of the dispositional forgiveness in female and male adolescents. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, B., Buelga, S., Cava, M. J., & Ortega-Barón, J. (2019). Cyberbullying, psychosocial adjustment, and suicidal ideation in adolescence. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(2), 75-81. [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., & Ortega, R. (2016). Impact of the ConRed program on different cyberbulling roles. Aggressive behavior, 42(2), 123-135. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, D., & Awasthi, A. (2020). ICT exposure and the level of wellbeing and progress: a cross country analysis. Social Indicators Research, 147(1), 311-343. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martín, A., Martín-del-Pozo, M., & Iglesias-Rodríguez, A. (2021). Pre-adolescents’ digital competences in the area of safety. Does frequency of social media use mean safer and more knowledgeable digital usage?. Education and Information Technologies, 26(1), 1043-1067. [CrossRef]

- Colella, G. M., Palermiti, A. L., Bartolo, M. G., Servidio, R. C., & Costabile, A. (2024). Problematic Social Media Use, Retaliation, and Moral Disengagement in Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization Among Italian Preadolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Meeus, A., Beullens, K., & Eggermont, S. (2023). Social media, unsocial distraction? Testing the associations between preadolescents’ SNS use and belonging via two pathways. Media Psychology, 26(4), 363-387. [CrossRef]

- Brighi, A., Menin, D., Skrzypiec, G., & Guarini, A. (2019). Young, bullying, and connected. Common pathways to cyberbullying and problematic internet use in adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1467. [CrossRef]

- Romera, E. M., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Runions, K., & Camacho, A. (2021). Bullying perpetration, moral disengagement and need for popularity: Examining reciprocal associations in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(10), 2021-2035. [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L., Schulz, P. J., & Camerini, A. L. (2020). Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in youth: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(2), 163-181. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. L., Mehari, K. R., & Farrell, A. D. (2020). Deviant peer factors during early adolescence: cause or consequence of physical aggression?. Child development, 91(2), e415-e431. [CrossRef]

- Arató, N., Zsidó, A. N., Lenard, K., & Labadi, B. (2020). Cybervictimization and cyberbullying: The role of socio-emotional skills. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 248. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Chen, L., Wang, Y., and Li, Y. (2020). The link between childhood psychological maltreatment and cyberbullying perpetration attitudes among undergraduates: testing the risk and protective factors. PLoS One 15:e0236792. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Cao, Y., & Tian, J. (2021). Effects of violent video games on aggressive cognition and aggressive behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(1), 5-10. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27-51. [CrossRef]

- Graf, D., Yanagida, T., Runions, K., & Spiel, C. (2022). Why did you do that? Differential types of aggression in offline and in cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, 107107. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. S., Yusuf, S., Victor, S. A., & Abidin, M. Z. Z. (2024). Towards Understanding the Personal and Situational Factors of Cyber Aggression: A Theoretical Review. Jurnal Pengajian Media Malaysia, 26(1), 1-15.

- Jiang, H., Liang, H., Zhou, H., & Zhang, B. (2022). Relationships among normative beliefs about aggression, moral disengagement, self-control and bullying in adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Psychology research and behavior management, 183-192.

- Wachs, S., Machimbarrena, J. M., Wright, M. F., Gámez-Guadix, M., Yang, S., Sittichai, R., ... & Krause, N. (2022). Associations between coping strategies and cyberhate involvement: Evidence from adolescents across three world regions. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(11), 6749. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J. S., & Reeve, J. (2021). Developmental pathways of preadolescents' intrinsic and extrinsic values: The role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. European Journal of Personality, 35(2), 151-167. [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Developmental psychology, 43(2), 267. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267.

- Clark, J. L., Algoe, S. B., & Green, M. C. (2018). Social network sites and well-being: The role of social connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(1), 32-37. [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E., Spina, G., Agostiniani, R., Barni, S., Russo, R., Scarpato, E., ... & Staiano, A. (2022). The use of social media in children and adolescents: Scoping review on the potential risks. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(16), 9960. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F., Colella, G. M., & Boursier, V. (2022). Evidence on problematic online gaming and social anxiety over the past ten years: A systematic literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M., Maier, C., Laumer, S., & Weitzel, T. (2020). Explaining the link between technostress and technology addiction for social networking sites: A study of distraction as a coping behavior. Information Systems Journal, 30(1), 96-124. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. A., & David, M. E. (2020). The social media party: Fear of missing out (FoMO), social media intensity, connection, and well-being. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 36(4), 386-392. [CrossRef]

- Best, P., Manktelow, R., & Taylor, B. (2014). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 27-36. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). [CrossRef]

- Chen, I. H., Pakpour, A. H., Leung, H., Potenza, M. N., Su, J. A., Lin, C. Y., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Comparing generalized and specific problematic smartphone/internet use: Longitudinal relationships between smartphone application-based addiction and social media addiction and psychological distress. Journal of behavioral addictions, 9(2), 410-419. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., Xiong, D., Jiang, T., Song, L., & Wang, Q. (2019). Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology: Journal of psychosocial research on cyberspace, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Cebollero-Salinas, A., Orejudo, S., Cano-Escoriaza, J., & Íñiguez-Berrozpe, T. (2022). Cybergossip and Problematic Internet Use in cyberaggression and cybervictimisation among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 131, 107230. [CrossRef]

- Montag, C., Demetrovics, Z., Elhai, J. D., Grant, D., Koning, I., Rumpf, H. J., ... & van den Eijnden, R. (2024). Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addictive behaviors, 107980. [CrossRef]

- Wachs, S., Bilz, L., Wettstein, A., Wright, M. F., Krause, N., Ballaschk, C., & Kansok-Dusche, J. (2022). The online hate speech cycle of violence: Moderating effects of moral disengagement and empathy in the victim-to-perpetrator relationship. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(4), 223-229. [CrossRef]

- Borraccino, A., Marengo, N., Dalmasso, P., Marino, C., Ciardullo, S., Nardone, P., ... & 2018 HBSC-Italia Group. (2022). Problematic social media use and cyber aggression in Italian adolescents: the remarkable role of social support. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(15), 9763. [CrossRef]

- Craig, W., Boniel-Nissim, M., King, N., Walsh, S. D., Boer, M., Donnelly, P. D., ... & Pickett, W. (2020). Social media use and cyber-bullying: A cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S100-S108. [CrossRef]

- Mascia, M. L., Agus, M., Zanetti, M. A., Pedditzi, M. L., Rollo, D., Lasio, M., & Penna, M. P. (2021). Moral disengagement, empathy, and cybervictim’s representation as predictive factors of cyberbullying among Italian adolescents. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(3), 1266. [CrossRef]

- Marín-López, I., Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Hunter, S. C., & Llorent, V. J. (2020). Relations among online emotional content use, social and emotional competencies and cyberbullying. Children and youth services review, 108, 104647. [CrossRef]

- Pornari, C. D., & Wood, J. (2010). Peer and cyber aggression in secondary school students: The role of moral disengagement, hostile attribution bias, and outcome expectancies. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 36(2), 81-94. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., & Ngai, S. S. Y. (2020). The effects of anonymity, invisibility, asynchrony, and moral disengagement on cyberbullying perpetration among school-aged children in China. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105613. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Dong, W., & Qiao, J. (2023). How is childhood psychological maltreatment related to adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration? The roles of moral disengagement and empathy. Current Psychology, 42(19), 16484-16494. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2016). Moral Disengagement: How People Do Harm and Live with Themselves, by Albert Bandura. New York: Macmillan, 2016. 544 pp. ISBN: 978-1.

- Zhou, Y., Zheng, W., & Gao, X. (2019). The relationship between the big five and cyberbullying among college students: The mediating effect of moral disengagement. Current Psychology, 38(5), 1162-1173. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Li, S., Gao, L., & Wang, X. (2022). Longitudinal associations among peer pressure, moral disengagement and cyberbullying perpetration in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107420. [CrossRef]

- Kırcaburun, K., Kokkinos, C. M., Demetrovics, Z., Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., & Çolak, T. S. (2019). Problematic online behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults: Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, and psychosocial factors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 891-908. [CrossRef]

- Lo Cricchio, M. G., García-Poole, C., te Brinke, L. W., Bianchi, D., & Menesini, E. (2021). Moral disengagement and cyberbullying involvement: A systematic review. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 271-311. [CrossRef]

- Chan, T. K., Cheung, C. M., Benbasat, I., Xiao, B., & Lee, Z. W. (2023). Bystanders join in cyberbullying on social networking sites: the deindividuation and moral disengagement perspectives. Information Systems Research, 34(3), 828-846. [CrossRef]

- Baldry, A. C., Sorrentino, A., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Post-traumatic stress symptoms among Italian preadolescents involved in school and cyber bullying and victimization. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2358-2364. [CrossRef]

- Henares-Montiel, J., Benítez-Hidalgo, V., Ruiz-Perez, I., Pastor-Moreno, G., & Rodríguez-Barranco, M. (2022). Cyberbullying and associated factors in member countries of the European Union: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies with representative population samples. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(12), 7364. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, E., Liberska, H. D., Li, J. B., Espada, J. P., Delvecchio, E., Mazzeschi, C., ... & Salcuni, S. (2021). A cross-cultural study on attachment and adjustment difficulties in adolescence: the mediating role of self-control in Italy, Spain, China, and Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8827. [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, S. S., Nickerson, A. B., & Livingston, J. A. (2022). Adolescent social media use: Pitfalls and promises in relation to cybervictimization, friend support, and depressive symptoms. Journal of youth and adolescence, 51(2), 361-376. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A. L., Prosek, E. A., & Watson, J. C. (2021). Understanding adolescent cyberbullies: exploring social media addiction and psychological factors. Journal of child and adolescent counseling, 7(1), 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Falla, D., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Romera, E. M. (2021). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the transition from cybergossip to cyberaggression: A longitudinal study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(3), 1000. [CrossRef]

- Gajda, A., Moroń, M., Królik, M., Małuch, M., & Mraczek, M. (2023). The Dark Tetrad, cybervictimization, and cyberbullying: The role of moral disengagement. Current Psychology, 42(27), 23413-23421. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. S. (2024). All by myself: examining social media’s effect on social withdrawal and the mediating roles of moral disengagement and cyberaggression. European Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 659-684. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Marino, C., Canale, N., Charrier, L., Lazzeri, G., Nardone, P., & Vieno, A. (2022). The effect of problematic social media use on happiness among adolescents: The mediating role of lifestyle habits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2576. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., Khan, A. N., Zaigham, G. H., & Khan, N. A. (2019). The stimulators of social media fatigue among students: Role of moral disengagement. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(5), 1083-1107. [CrossRef]

- Casale, S., & Fioravanti, G. (2011). Psychosocial correlates of internet use among Italian students. International Journal of Psychology, 46(4), 288-298. [CrossRef]

- Bali, D., Pastore, M., Indrio, F., Giardino, I., Vural, M., Pettoello-Mantovani, C., ... & Pettoello-Mantovani, M. (2023). Bullying and cyberbullying increasing in preadolescent children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 261. [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R., Elipe, P., Mora-Merchán, J. A., Genta, M. L., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., ... & Tippett, N. (2012). The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: A European cross-national study. Aggressive behavior, 38(5), 342-356. [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H., Farrington, D. P., Espelage, D. L., & Ttofi, M. M. (2019). Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggression and violent behavior, 45, 134-153. [CrossRef]

- Monacis, L., De Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. Journal of behavioral addictions, 6(2), 178-186. [CrossRef]

- Copez-Lonzoy, A., Vallejos-Flores, M., Capa-Luque, W., Salas-Blas, E., Doig, A. M. M., Dias, P. C., & Bazo-Alvarez, J. C. (2023). Adaptation of the bergen social media addiction scale (BSMAS) in Spanish. Acta Psychologica, 241, 104072. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child development, 67(3), 1206-1222. [CrossRef]

- Romera, E. M., Herrera-López, M., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Camacho, A. (2023). The moral disengagement scale-24: Factorial structure and cross-cultural comparison in Spanish and Colombian adolescents. Psychology of violence, 13(1), 13. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/vio0000428.

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Bussey, K. (2015). The role of individual and collective moral disengagement in peer aggression and bystanding: A multilevel analysis. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 43, 441-452. [CrossRef]

- Brighi, A., Ortega, R., Pyzalski, J., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P. K., Tsormpatzoudis, H., & Tsorbatzoudis, H. (2012). European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior.

- Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J. A. (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicología educativa, 22(1), 71-79. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach, 1(6), 12-20.

- Gori, A., & Topino, E. (2023). The association between alexithymia and social media addiction: Exploring the role of dysmorphic symptoms, symptoms interference, and self-esteem, controlling for age and gender. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(1), 152. [CrossRef]

- Gradinger, P., Yanagida, T., Strohmeier, D., & Spiel, C. (2016). Effectiveness and sustainability of the ViSC Social Competence Program to prevent cyberbullying and cyber-victimization: Class and individual level moderators. Aggressive behavior, 42(2), 181-193. [CrossRef]

- Hormes, J. M., Kearns, B., & Timko, C. A. (2014). Craving Facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction, 109(12), 2079-2088. [CrossRef]

- Güler, H., Öztay, O. H., & Özkoçak, V. (2022). Evaluation of the relationship between social media addiction and aggression. Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences, 21(3), 1350-1366. [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, G. P., Burk, W. J., Stoltz, S. E., van den Berg, Y. H., & Cillessen, A. H. (2021). A longitudinal social network perspective on adolescents' exposure to violent video games and aggression. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(1), 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Digennaro, S. (2023). The use of social media among preadolescents: habits and consequences. J Health Educ Sports Inclus Didactics, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hamm, M. P., Newton, A. S., Chisholm, A., Shulhan, J., Milne, A., Sundar, P., ... & Hartling, L. (2015). Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: A scoping review of social media studies. JAMA pediatrics, 169(8), 770-777. [CrossRef]

- Yao, M., Zhou, Y., Li, J., & Gao, X. (2019). Violent video games exposure and aggression: The role of moral disengagement, anger, hostility, and disinhibition. Aggressive behavior, 45(6), 662-670. [CrossRef]

- Pabian, S., & Vandebosch, H. (2016). (Cyber) bullying perpetration as an impulsive, angry reaction following (cyber) bullying victimisation?. Youth 2.0: Social Media and Adolescence: Connecting, Sharing and Empowering, 193-209. [CrossRef]

- Tanrikulu, I., & Erdur-Baker, Ö. (2021). Motives behind cyberbullying perpetration: a test of uses and gratifications theory. Journal of interpersonal Violence, 36(13-14), NP6699-NP6724. [CrossRef]

- Bushman, B. J., Anderson, C. A., & Allen, J. J. (2020). General aggression model. The international encyclopedia of media psychology, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C. P. (2023). Cyberbullying as a learned behavior: theoretical and applied implications. Children, 10(2), 325. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).