3.1. Impact of Different Parameters on Extraction of Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity of the Extracts

The extraction of phenolic compounds and the assessment of antioxidant activity from the leaves of

Capparis spinosa are influenced by various parameters.

Table 1 presents the results obtained under various extraction conditions, including the phenolic content and antioxidant activity associated with each specific extraction condition.

The effect of ethanol concentration on polyphenol extraction showed some interesting results. Using a lower ethanol concentration (30%) with higher ultrasound power (90%) gave the highest TPC and antioxidant activity. For example, at 50°C with 30% ethanol and 90% ultrasound power, the TPC reached 23.14 mg GAE/g, and antioxidant activity was 20.61 mg TE/g in the DPPH test. This suggests that phenolic compounds play a key role in the antioxidant capacity of the extracts. On the other hand, higher ethanol concentrations (like 70%) resulted in lower yields of phenolic compounds and flavonoids, probably because more polar compounds were less soluble and harder to extract. For example, at 80°C with 70% ethanol, the TPC dropped to 18.75 mg GAE/g. With 70% ethanol, 80°C, and 30% ultrasound power, high total flavonoid content (101.38 mg GAE/g) and rutin content (14.74 mg/g) were seen. However, very high or low ethanol concentrations didn’t significantly improve TPC or antioxidant activity, suggesting that a balance in solvent polarity is important for the best polyphenol extraction. Moderate ethanol concentrations (50–70%) were better for getting higher yields of TPC and rutin. The highest rutin content (14.78 mg/g) was achieved at 80°C with 50% ethanol and 60% ultrasound power. DPPH scavenging activity remained fairly consistent across conditions (around 20–21.8 mg TE/g), showing that antioxidant properties remained strong throughout. The highest DPPH activity (21.87 mg TE/g) occurred at 65°C, 50% ethanol, and 60% ultrasound power, which also matched the highest TPC value, indicating a strong link between extracted polyphenols and antioxidant activity.

Higher extraction temperatures, especially around 80°C, generally led to higher TPC yields, with the highest TPC (23.14 mg GAE/g) found at 80°C, 30% ethanol, and 30% ultrasound power. This could be due to better solvent diffusion and cell wall breakdown at higher temperatures, which helps release more phenolics. The results also showed that moderate temperatures (50°C to 65°C) tended to boost both TPC and antioxidant activity. For example, at 65°C with 50% ethanol, the TPC was 22.25 mg GAE/g, indicating that moderate temperatures helped dissolve phenolic compounds without breaking them down, unlike at higher temperatures (80°C), where TPC dropped to 20.08 mg GAE/g. However, the total flavonoid content (TFC) didn’t follow the same pattern. At higher temperatures (80°C), TFC values decreased. Moderate temperatures, especially between 50°C and 65°C, resulted in higher TFC values. The highest TFC (132.14 mg GAE/g) was seen at 65°C, suggesting that certain polyphenolic compounds may be better extracted at lower thermal conditions, possibly because high temperatures can cause thermal degradation or transformation of heat-sensitive compounds. For example, at 50°C with 30% ethanol, the TFC was highest, indicating that this temperature range is ideal for extracting flavonoids without degrading them.

Ultrasound power plays a vital role in enhancing extraction efficiency by breaking down plant cell walls and improving solvent penetration. As shown in

Table 1, increasing ultrasound power leads to higher yields of phenolics and flavonoids. Increasing ultrasound power from 30% to 90% significantly enhances both TPC and TFC. The highest values for both TPC (23.1436 mg GAE/g) and TFC were achieved at 50°C, 30% ethanol, and 90% ultrasound power. Conversely, lower ultrasound power (60%) produced significantly lower phenolic and flavonoid yields. For example, at 80°C with 30% ethanol, TPC decreased to 20.08 mg GAE/g. The data also highlights that ultrasound power, especially at moderate temperatures, significantly increases rutin yield. At 50°C with 30% ethanol, rutin concentration was 10.034 mg/g with 30% ultrasound power, but increased to 14.15 mg/g when ultrasound power was raised to 90%, suggesting that ultrasound-assisted extraction is effective way in maximizing the extraction efficiency of rutin.

3.2. Parameters Optimization

The experimental data presented in

Table 1, coupled with the regression analysis (

Table 2), provides a clear understanding of the relationships between these factors and how they influence extraction efficiency. The regression analysis of bioactive compound extraction from

Capparis spinosa using UAE revealed several significant linear, interaction, and quadratic effects. The response variables analyzed include total phenolics (TP), total flavonoids (TF), antioxidant activity (DPPH test) and rutin content. Regression coefficients and model diagnostics such as the coefficient of determination (R²) and coefficient of variance (CV) are presented in

Table 2, illustrating how extraction conditions impact the yield and quality of these compounds.

For total phenolic content, the model was found to be significant, with temperature (β1) and ethanol concentration (β2) identified as the primary drivers (p=0.0249 and p=0.0078, respectively). The observed significant interaction between temperature and ethanol concentration (β12, p=0.0225) indicates that these two factors work together to enhance phenolic extraction. In contrast, ultrasound power (β3) showed a borderline effect (p = 0.0875), and the lack of significant quadratic terms implies that the relationships in this case are mostly linear.

The analysis of total flavonoid content exhibited some differences. While the overall model was significant (p=0.0060), ethanol concentration emerged as the most influential factor (p=0.0003). The significant quadratic term for ethanol concentration underscores a nonlinear relationship, indicating that precise control is required for optimal extraction. In this case, neither temperature nor ultrasound power displayed significant main effects (p=0.1312 and p=0.4998, respectively), and there were no significant interaction terms. Although the quadratic term for temperature approached significance (p=0.0574), the data suggest that ethanol concentration is the key parameter for flavonoid extraction, emphasizing the need for careful management.

Regarding antioxidant activity assessed by DPPH, although the linear effect of ultrasound power (β3 = 0.26) was not statistically significant, its interactions with other variables were crucial for enhancing antioxidant activity. The positive interaction term (β23=0.44, p<0.05) suggests that specific combinations of extraction parameters can lead to synergistic effects that increase the antioxidant capacity of the extracts. This indicates that the overall extraction process benefits from the interactions among temperature, ethanol concentration, and ultrasound power, even if individual parameters show limited effects.

In terms of rutin content, the model demonstrated robust significance (p=0.0124), with temperature and ethanol concentration again playing dominant roles (p=0.0010 and p=0.0032, respectively). Unlike TPC, ultrasound power did not have a significant impact on rutin extraction (p=0.5929), and the model revealed a linear relationship for rutin recovery, indicating that fine-tuning temperature and ethanol concentration is essential for maximizing the extraction of specific phenolic compounds.

The linear, interaction, and quadratic effects identified in this study provide valuable insights into how various variables affect the extraction process. The reliability of the models is supported by high R² values and low CVs, making them effective tools for predicting extraction outcomes and optimizing protocols for better yields. Across all responses, total phenolic content, rutin, and total flavonoids—the regression models demonstrated statistical significance, with p-values ranging from less than 0.0001 to 0.0319. The adjusted R² values, which range from 0.69 to 0.98, indicate a strong fit and explain a substantial portion of the variance in the results. This strong correlation is further validated by relatively low CVs for most responses, suggesting precise model predictions. Although some lack-of-fit results, such as the p-value of 0.0618 for flavonoids, suggest minor areas for improvement, the overall non-significant lack-of-fit tests indicate that the models remain reliable for making predictions within the tested conditions. This underscores the effectiveness of the regression models in guiding the extraction process and optimizing results.

Taken together, that ethanol concentration showed to be a critical parameter across all responses, especially for flavonoid extraction with only marginal contributions from temperature and ultrasound power. For TPC and rutin, optimizing temperature in tandem with ethanol concentration appears essential due to their strong interaction, while ultrasound power has lower influence.

Based on the experimental results and statistical analysis, numerical optimizations have been conducted in order to establish the optimum level of independent variables with desirable response of goals. For all responses one optimal condition was obtained: 80 °C temperature, 62.23% ethanol, 56.05% of ultrasound power. Determination of optimal conditions and predicted values was based on desirability function, D = 0.778, in order to focus on high rutin content. In order to verify predictive mathematical model of the investigated process experimental confirmation of obtained was performed on estimated optimal conditions. Predicted and the observed values are presented in

Table 3. The predicted results matched well with the experimental results obtained at optimal extraction conditions which were validated by the RSM model with good correlation.

Similar findings were reported by Boudries et al. (2019), who demonstrated that both experimental and modeled data confirmed a significant enhancement in extraction efficiency when ethanol was incorporated into the solvent system. Although temperature also had a positive influence, its effect was comparatively less pronounced in the extraction of phenolic compounds from Capparis spinosa flower buds.

To date, the content of total polyphenols, flavonoids, and flavonols has been extensively investigated in various edible aerial parts of the caper plant. According to Wojdyło et al. (2019), flower buds exhibited notably high levels of total polyphenols (849.4 mg GAE/100 g FW), flavonoids (729.5 mg RE/100 g FW), and flavonols (691.6 mg RE/100 g FW), surpassing the concentrations observed in young caper shoots. In contrast, caper fruits presented considerably lower levels of these compounds, with total polyphenols at 119.2 mg GAE/100 g FW, flavonoids at 81.6 mg RE/100 g FW, and flavonols at 39.9 mg RE/100 g FW [

4].

Although research on caper shoots and leaves are limited, some studies have explored their polyphenol content. Gull et al. (2019) reported a relatively low total polyphenol concentration of approximately 28.7 mg GAE/100 g DW in shoots. Tlili et al. (2017), in a study on methanolic extracts from C. spinosa leaves, reported total phenolics, flavonoids, and condensed tannins of 23.37 mg GAE/g DW, 9.05 mg QE/g DW, and 9.35 mg TAE/g DW, respectively. Further insights were provided by Fattahi & Rahimi (2016), who applied response surface methodology to optimize extraction from C. spinosa leaves. The optimal conditions—49% ethanol, 51.8 °C, and a solvent-to-material ratio of 50 (v/w)—resulted in total polyphenol content of 27.44 mg GAE/g DW, total flavonoid content of 26.07 mg QE/g DW, and DPPH radical scavenging activity of 85.74%. In comparison, the present study optimized ultrasound-assisted extraction conditions at 80 °C, 62.23% ethanol, and 56% ultrasound power. Under these parameters, the obtained values were: total polyphenol content of 19.82 mg GAE/g DW, total flavonoid content of 99.26 mg RE/g DW, antioxidant activity of 21.54 mg TE/g DW (DPPH assay), and rutin content of 15.79 mg/g DW. While the TPC obtained was slightly lower than some values reported in literature, the high flavonoid content and particularly high rutin concentration underscore the efficiency of the extraction method. Moreover, the specific quantification of rutin (15.79 mg/g DW) highlights the successful enrichment of this pharmacologically significant compound, which is not always individually assessed in earlier studies. It is important to note that TFC (as RE) encompasses multiple flavonoid constituents beyond rutin, reflecting the cumulative content of flavonoids in the extract. The optimized conditions employed in this research demonstrate a highly effective and sustainable approach to maximizing the recovery of phenolics and flavonoids from Capparis spinosa.

Differences between the present findings and literature values can be attributed to several factors, including the plant part analyzed, geographical origin, genotype, harvesting stage, and extraction methodology. Additionally, the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds and flavonoids is known to be influenced by abiotic stresses, such as heat, which further contributes to variability in phytochemical content [

18].

3.3. HPLC Analysis

HPLC analysis was conducted on all extracts in order to determine how extraction conditions affect polyphenolic profile. UnderIn all experimental conditions, rutin was a dominant compound, therefore it was included as a main compound in the optimization process. The HPLC profile of the extract obtained at optimal conditions is presented in

Table 4. The HPOLC analysis of optimal extract reviealed several key compounds, including catechin equivalents, caffeine, syringic acid, sinapic acid, rutin, and quercetin-3-glucoside, which are known for their potential health benefits.

The phytochemical composition of Capparis spinosa has been extensively investigated, with several studies highlighting its richness in phenolic and flavonoid compounds. Among these, rutin consistently emerges as the dominant flavonoid. Gull et al. (2019) and Tlili et al. (2017) emphasized C. spinosa as a notable source of rutin and quercetin derivatives, with high pharmacological and nutritional potential. In the present study, HPLC analysis revealed a rutin content of 15.51 mg/g DW, emphasizing the effectiveness of the optimized ultrasound-assisted extraction protocol. This value is notably higher than the 3.96 mg/g DW reported by Tlili et al. (2017), suggesting considerable variability that may be attributed to differences in extraction methods, solvent systems, plant material, and environmental or cultivation conditions. Although ultrasound power did not have a significant impact on rutin extraction (p = 0.5929), the higher rutin yield observed in this study highlights the potential advantages of ultrasound-assisted extraction in enhancing the recovery of specific bioactive compounds.

In addition to rutin, quercetin-3-glucoside (4.27 mg/g DW) was identified in the extract. This specific compound was not reported by Tlili et al. (2017), although their analysis revealed other flavonols such as kaempferol (0.40 mg/g DW) and luteolin (0.78 mg/g DW). While quercetin derivatives are evident in both studies, differences in the types and concentrations of flavonoids underscore the influence of extraction techniques and the specific plant material analyzed. Furthermore, catechin was detected at 2.07 mg/g DW in the present study, which is notably higher than the 0.56 mg/g DW reported by Tlili et al. (2017). In contrast, gallic acid content in this extract was 0.04 mg/g DW, which is lower than the 0.14 mg/g DW observed by Tlili et al. Syringic acid (0.19 mg/g DW) and caffeic acid (0.25 mg/g DW) were also identified in the present extract. In contrast, Tlili et al. (2017) did not report caffeic acid in their analysis and instead identified vanillic acid (0.27 mg/g DW) among the minor phenolic acids. These differences in phenolic acid profiles may reflect not only methodological variations such as the use of ultrasound-assisted extraction with ethanol versus maceration with methanol but also differences in phonological stage of leaf collection, plant genotype, or eco-geographical growing conditions. A notable contrast is the presence of resveratrol, which was the second most abundant compound (2.35 mg/g DW) in the extract analyzed by Tlili et al., yet it was not detected in the current study. Similarly, epicatechin (1.28 mg/g DW) and coumarin (1.33 mg/g DW) were reported by Tlili et al. but were not observed in the present analysis. This could suggest a selectivity of ultrasound-assisted extraction toward specific phenolic compounds, or it may indicate differences in compound solubility and extraction efficiency related to solvent polarity, matrix structure, or compound stability under ultrasonic conditions.

These variations may be attributed to differences in extraction methods (e.g., ultrasound-assisted extraction using ethanol vs. conventional maceration with methanol), solvent polarity, temperature, or ultrasound power intensity, all of which significantly affect the recovery and profile of phenolic compounds. Moreover, the

high flavonol content observed in this study may be linked to the plant’s physiological responses to

biotic and abiotic stressors. As noted by

Stefanucci et al. (2018) the accumulation of flavonols such as

rutin, quercetin, and kaempferol often reflects the plant’s adaptive response to environmental pressures, including

UV radiation, drought, temperature extremes, or pathogen attack. In addition, Kianersi

et al. (2020) demonstrated that

exogenous application of salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate can significantly stimulate

rutin biosynthesis in C. spinosa in a growth stage-dependent manner [

19]. These findings suggest that

targeted agronomic interventions, in combination with

optimized extraction protocols, could further enhance the yield of valuable bioactive compounds in

C. spinosa.

3.4. Cell Culture Response to Extract Treatment

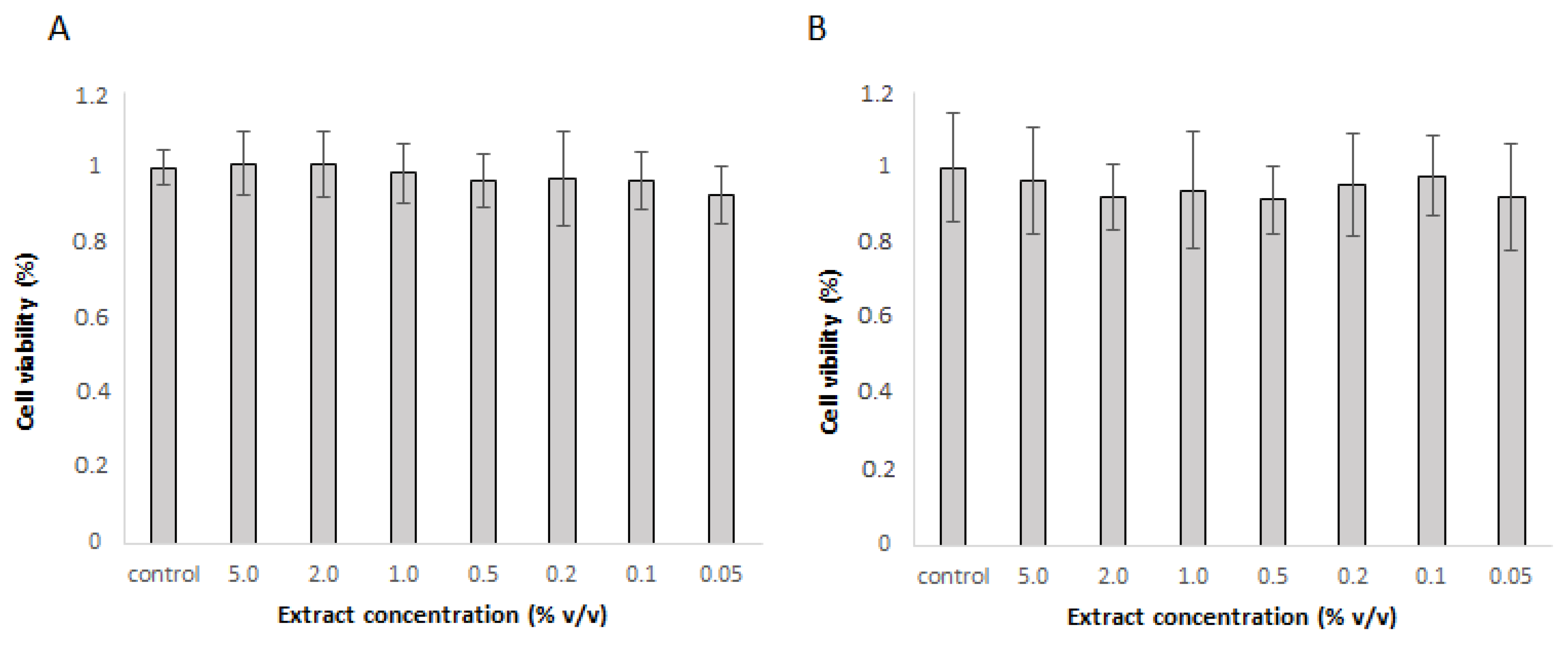

Based on the results in

Table 1, the extract prepared at optimal conditions, with the highest rutin level, was selected to test its properties in cell lines. First, cytotoxicity was tested in Caco-2 and Hep G2 cells. The extract was not toxic in concentrations up to 5% v/v in neither cell line. As none of the concentrations were toxic, the extract was used in 1% and 5% concentration for further experiments.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity of different extract concentrations as determined by PrestoBlue Assay in A) Caco-2 cells and B) Hep G2 cells. The mean ± SD of three separate experiments is presented.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity of different extract concentrations as determined by PrestoBlue Assay in A) Caco-2 cells and B) Hep G2 cells. The mean ± SD of three separate experiments is presented.

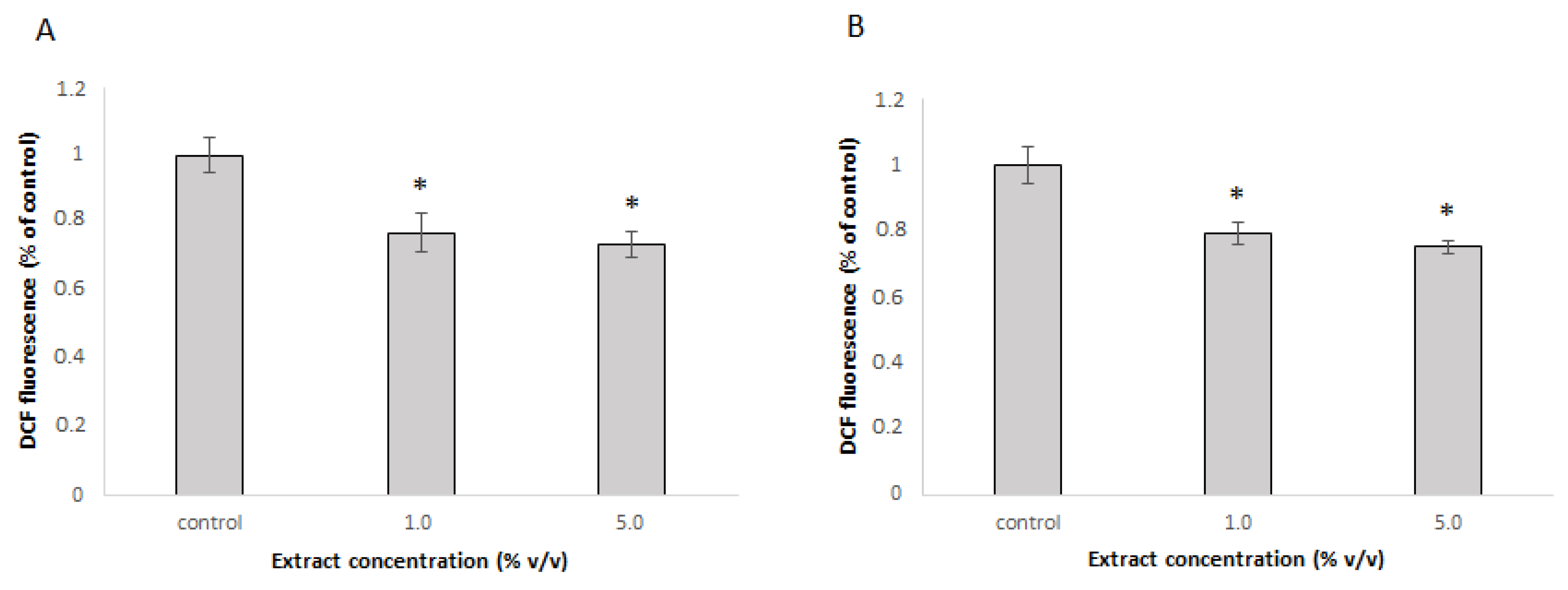

In vitro results showed promising results for the antioxidative potential of the extract. The extract was further tested for its ability to protect cells against t-BOOH-induced oxidative stress. DCHF-DA assay which is based on the use of a fluorescent cell permeable probe that reacts with reactive oxygen species (ROS) to form green fluorescent product was used. Given that antioxidative effects in cell cultures depend on the ability of individual compounds to cross cell membranes and the presence of metabolic enzymes that may convert them, the protective effect of the extract against induced oxidative stress was evaluated in Caco-2 and Hep G2 cells. Caco-2 cells, which represent colon cells, were selected as they are the first to encounter ingested substances. Hep G2 cells, representing liver cells, were chosen for their role in metabolizing bioactive compounds. These two cell types are therefore suitable for assessing the safety and potential beneficial effects of dietary substances. In Caco-2 cells, the extract had a significant protective effect in both tested concentrations and reduced the amount of ROS to 79 % and 75 % in 1.0% and 5.0% concentration, respectively (

Figure 2A). The results were similar in Hep G2 cells, where the amount of ROS was reduced to 77% with 1.0% extract and to 73% with a 5% extract (

Figure 2B).

The protective effect may be exerted through various mechanisms, including the direct action of bioactive compounds, as measured by

in vitro tests, or the increased production of endogenous antioxidants. The protective effect of rutin as a dominant compound in optimized extract of

C. spinosa and other compounds found in the extract may be mediated through various mechanisms, including the direct action of bioactive compounds, as demonstrated by

in vitro tests, or through enhanced production of endogenous antioxidants. Rutin has been shown to modulate several cell signaling pathways involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis, effectively suppressing key features of cancer progression [

20,

21,

22].

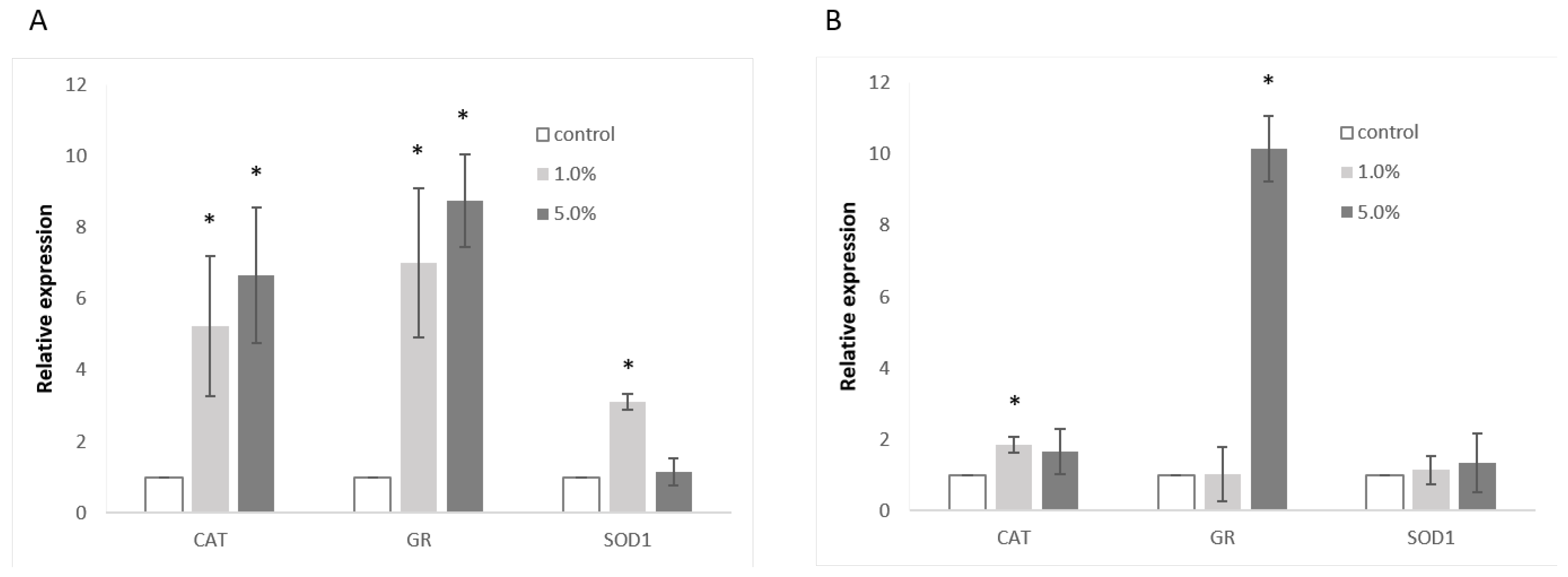

To further investigate these effects, RT-PCR was employed to assess the expression levels of catalase (CAT), glutathione reductase (GR), and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD-1). In Caco-2 cells (

Figure 3A), CAT expression was significantly elevated, showing a 5.3-fold increase with 1.0% extract and a 6.7-fold increase with 5.0% extract compared to control cells. GR expression was also notably up-regulated, with a 7.0-fold increase for the 1.0% extract and an 8.8-fold increase for the 5.0% extract. The effect on SOD-1 was less pronounced, with only a 3.1-fold increase observed at the lower extract concentration. In Hep G2 cells (

Figure 3B), GR expression was markedly increased, showing a 10.2-fold up-regulation in response to the 5% extract, while the lower concentration resulted in a moderate 1.8-fold up-regulation of CAT. Other gene expressions remained unaffected.

The non-toxic nature of the extract at the tested concentrations suggests its safe incorporation into functional food products or use as a dietary supplement. Notably, the extract effectively protected cells from induced oxidative stress, as evidenced by significantly lower levels of reactive oxygen species in both cell types when pretreated with the extract. Since the extract was removed prior to the addition of t-BOOH in this experiment, the protective effect cannot be attributed to direct reactions between the bioactive compounds of the extract and t-BOOH in the cell culture media. However, the components absorbed into the cells may act through such mechanisms. Moreover, results from the RT-PCR experiments indicate that the extract not only provides direct protection but also induces the expression of cellular antioxidative enzymes. This effect was more pronounced in Caco-2 cells, where all three tested gene expressions were significantly up-regulated. Less substantial effect in liver cells may be due to their already strong intrinsic antioxidant system and detoxification mechanisms, which may neutralize the active components. This includes phase I and phase II enzymes, known to be expressed in Hep G2 cells [

23].

The observed protective effect and the induction of antioxidative enzymes can be attributed to the chemical components detected in the extract. Rutin, the main component, was consistently shown to protect cells from oxidative damage [

24,

25,

26], partly by activating CAT and SOD [

27]. Similarly, quercetin demonstrated efficient antioxidant capacity [

28,

29]. Quercetin increased the expression of CAT and decreased the expression of SOD at low concentrations, but this effect was reversed at high concentrations [

27]. Such phenomenon is most commonly observed for complex mixtures of bioactive compounds. According to the principle of hormesis, low concentrations of certain compounds stimulate adaptive cellular responses, but when higher concentrations are used, such compensation is no longer possible [

30]. Therefore, the observed induced expression of SOD1 in Caco-2 cells and CAT in Hep G2 cells only at lower extract concentrations is not surprising.