1. Introduction

Turmeric (

Curcuma longa), a resilient perennial herb indigenous to India, is used as a spice, traditional herb, and food additive [

1]. The turmeric rhizome contains major bioactives with anti-inflammatory potential [

2]. These include curcuminoid compounds, which comprise primary polyphenols such as curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin [

3]. Given its anti-inflammatory properties, curcumin offers therapeutic potential for treating inflammatory diseases, thus supporting a holistic health-management strategy [

4]. The curcuminoids in turmeric, and curcumin in particular, are widely reported to have antidiabetic potential, via multiple mechanisms [

31,

32]. In diabetic animals, curcumin supplementation reduces levels of blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin and of the inti-inflammatory markers such as IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in diabetic animals [

33]. The administration of large doses of curcumin or turmeric reduces blood pressure by promoting eNOS production, boosting antioxidant capacity by restoring glutathione levels, and reducing excess reactive oxygen species levels [

34]. Curcumin and turmeric extract enhance nitric oxide bioavailability, promote endothelial vasorelaxation, resulting in the production of antioxidant enzymes [

35].

The selection of effective extraction methods is central in preserving the bioactivity of the extract [

5]. Common extraction techniques such as maceration, microwave-assisted extraction, and Soxhlet extraction exhibit various drawbacks, including low extraction yields, prolonged processing periods, excessive solvent consumption, and the need to use high temperatures; therefore, better extraction technology that is more economical and environmentally sustainable is required [

6]. Enzyme-assisted extraction utilizes catalysts to break down the cellular matrix and release metabolites [

7]. Combining enzymatic extraction and ultrasonication offers synergistic benefits in terms of green extraction technology [

8]. Using this approach, extraction can be accelerated, enhancing the release of bioactives and providing a cost-effective and ecofriendly method for improving extraction efficiency [

9]. Optimization of extraction conditions (such as enzyme concentration and ultrasonication time) based on experimental results would be essential to meet this target.

To address this need, we extracted turmeric bioactives using an enzyme-assisted ultrasonication extraction method. Response surface methodology (RSM) was applied to optimize the conditions with respect to the levels of the bioactives extracted and on their antioxidant capacities. The optimized extract was further analyzed on cytotoxicity, NO production, as well as their anti-inflammatory activity and antidiabetic potential.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Turmeric rhizome was acquired from a local market in Jindo (Republic of Korea). Chemicals including catechin, gallic acid, Griess reagent, α-amylase enzyme (30 U/mg), α-glucosidase, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), Folin–Ciocalteu’s phenol, acetic acid, and aluminum chloride, were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Biological materials such as fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin, and Minimum Essential Medium were sourced from Welgene (Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea).

2.2. Optimization Process

2.2.1. Enzyme-Assisted Ultrasonication

Enzymatic extraction was performed as previously described [

10], with some modification. Turmeric powder (10 g) was mixed with 65 mL of distilled water and 25 mL of 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5). The mixture was treated with different concentrations of α-amylase enzyme (10 U/mL), generated from RSM-CCD design, followed by incubation for 2 h at 35 °C. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 3000 ×

g for 15 min. To facilitate enzyme extraction and deactivation, the resulting supernatant was incubated in a water bath at 65 °C for 2 h, followed by filtration and drying in oven at 80 °C for 16 h. The resulting enzyme-treated powder (5 g) was dissolved in 100 mL of 80% ethanol and subjected to ultrasonic treatment using an ultrasonic cleaner (UC-20, JeioTech, Republic of Korea) for different sonication times, according to the RSM design. The sonicated mixture was then incubated with shaking at 130 rpm for 2 h at 35 °C, then centrifuged at 3000 ×

g for 15 min. After rotary evaporating the solvent under vacuum at 40 °C, the concentrated powder obtained was reconstituted in 10 mL of distilled water for further analysis.

2.2.2. Optimization via RSM

RSM modeling was performed using Design Expert 8.0.6 (Stat-Ease, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Enzyme concentration (X

1: 1.5%, 5%, and 8.5%) and ultrasonication time (X

2: 10, 20, and 100 min) were used as the independent variables to optimize extract bioactivity, in terms of total flavonoid content (TFC) and total phenolic content (TPC) as well as Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity [

11]. The variables were ranged based on prior findings [

12]. The levels of the independent variables were coded −1, 0, or 1 (low, medium, and high, respectively) (

Table 1).

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Bioactive Component Levels and Antioxidant Activity

Total phenolic content (TPC) was accessed using a previously established method [

13]. Briefly, turmeric extract (20 μL), 500 μL of 10% (w/v) Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and 20% sodium carbonate (w/v) were combined together. The solution was thoroughly mixed and incubated under the dark at 25±2°C for 2 h. Subsequently, absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer (EMCLAB Instruments, Duisburg, Germany), using gallic acid as a standard.

Total flavonoid content (TFC) was determined using the colorimetric assay method [

14]. Each sample extract (100 μL) was mixed with 75 μL of 5% sodium nitrite and 1.25 mL of distilled water. The mixture was stirred and allowed to react for 6 min at 25±2°C. Then, 150 μL of 10% aluminum chloride (w/v) was added and the solution was left to react for an additional 5 min. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of 1 mol/L sodium hydroxide was added to the mixture. Absorbance was determined at 510 nm using a spectrophotometer (EMCLAB Instruments), using quercetin as a standard.

The DPPH free radical scavenging activity of the extracted samples was examined via colorimetric method, as previously described [

15]. Initially, 50 μL of the sample extract (w/v) was mixed with 1950 μL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution. The resulting mixture was vortexed to ensure thorough mixing, then incubated in the dark for 30 min at 25±2°C. After incubation, absorbance was detected at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (EMCLAB Instruments), using Trolox as a standard.

The TEAC assay was conducted as previously described [

13]. Initially, a solution of ABTS (7.4 mM) and potassium persulfate (2.6 mM) was prepared at an equal ratio and placed in the dark at 25±2°C for at least 16 h to enable formation of ABTS radical cations (ABTS

+). After diluting with 100% methanol to achieve an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.01 at 734 nm, 2960 μL of the diluted ABTS

+ solution was mixed with 40 μL of the extract. The reaction was done within 7 min and absorbance was read by a microplate reader (EMCLAB Instruments), using Trolox as a standard.

2.3.2. Bioactivity

2.3.2.1. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

RAW 264.7 cells were grown in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM), supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

To determine the cytotoxicity of the extract and the concentration that maximizes cell viability, an MTT assay was conducted as previously described [

16]. The MTT stock solution was prepared using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide diluted with PBS (5 mg/mL) and was filtered through a 0.2 μm membrane filter. The RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 10

4 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were treated with varying concentrations of the turmeric extract. MTT stock solution (10%, 100 μL) was then added to the cells and was removed by suction after 4 h. The remaining formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μL of dimethylsulfoxide, and absorbance was determined at 595 nm using an EPOCH 2 microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA). Absorbance is presented relative to that of the control group.

For nitric oxide analysis, raw 264.7 cells were cultured in MEM containing 10% FBS at 37 °C in a 48-well plate at 1 × 10

5 cells/well in an incubator with 5% CO

2. The nitric oxide assay was conducted as previously described [

17], with slight modifications. The cell culture medium was then treated with various concentrations of the optimized extract along with 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 24 h. After incubation, 50 μL of the supernatant from each well was mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent and allowed to react for 10 min. Absorbance was examined at 540 nm using a microplate reader (EMCLAB). Sodium nitrate was utilized as a standard to determine the nitric oxide content of each sample.

2.3.2.2. Antidiabetic Effects

The antidiabetic potential of the optimized extract was accessed by comparing those of the ethanol- and water-derived extracts by analyzing their inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity [

18]. First, a mixture of 50 µL of the α-amylase (25U/mL) and 50 µL of each extract were placed in a 96-well plate and were kept at 25 °C for 10 min. Next, 1% starch solution (50 µL) in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9), was combined to the mixture and incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. The reaction was stopped with 100 µL of the dinitrosalicylic acid by steaming the plate for 5 min, and cooling for 20 min. The absorbance was then measured at 540 nm using an EPOCH 2 microplate reader (Biotek) for calculation of inhibition (%) using the following equation:

To analyze α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, a 96-well plate was prepared with 10 µL of α-glucosidase enzyme solution (0.5 U/mL), 20 µL of the sample at various concentrations, and 50 µL of phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.8), followed by incubation for 5 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, 20 µL of a 1 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (PNPG) solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) was added, then the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, 50 µL of 0.1 M sodium carbonate was added, absorbance was recorded at 405 nm, and inhibition was calculated as described in equation (2). The logit method was applied to obtain the IC50 values of both α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory effect.

2.3.2.3. Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibition

ACE inhibition assays were conducted as previously described [

19,

20], with modifications. ACE enzyme at 25 mU/mL, from rabbit lung, was incubated with 8.3 mM hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine (HHL) in a buffered solution (50 mM sodium borate containing 0.3 M NaCl, pH 8.3). Subsequently, 50 µL of each extract was mixed with 50 µL ACE solution, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. Thereafter, 150 µL of 8.3 mM HHL substrate solution was added to the mixture, which was again incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The reaction was terminated by adding 250 µL of 1.0 M HCl, followed by addition of 0.5 mL ethyl acetate for extraction. After centrifuging (4000

×g, 15 min at 25 °C), the concentration was carried out using a rotary evaporator 50 °C for 10 min. The resulting dried sample was dissolved in 1 mL of distilled water, and absorbance was determined at 228 nm using an EPOCH 2 microplate reader (Biotek).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was conducted in triplicate. All results are demonstrated as the mean ± SD. ANOVA was performed to determine the significance of the differences between samples. GraphPad Prism 10.3.1 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and XLSTAT 2021.2 (Addinsoft, Paris, France) were applied.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. RSM Design Matrix and Model Fitting

To optimize the extraction conditions, model fitting was performed using the relevant model-response parameters, namely sum of squares, df, mean squares, the

F and

p values, standard deviation,

R2, adjusted

R2, and lack of fit (

Table 2). A robust model is characterized by a significant

F-value,

p < 0.05, and an insignificant lack-of-fit value [

21]. The fitted model was significant, with a high

F-value; all of the response variables exhibited significance (

p < 0.0001).

R2 and adequate precision are key metrics for accessing model fitness. The closer the

R2 value is to 1, the more accurately the model fits. Here,

R2 was greater than 0.98 in all cases, substantially exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.8, thus revealing that the model is reliable and that the independent and response variables are strongly related [

22]. The adequate precision for all variables exceeded the minimum acceptable ratio of 4, ranging from 24.53 to 78.21, depending on the response variable. This suggests a robust signal-to-noise ratio and shows that the adjusted model possesses sufficient signal for navigating the design space [

23].

3.2. Effects of Extraction Conditions on Bioactive Component Levels and Antioxidant Activity

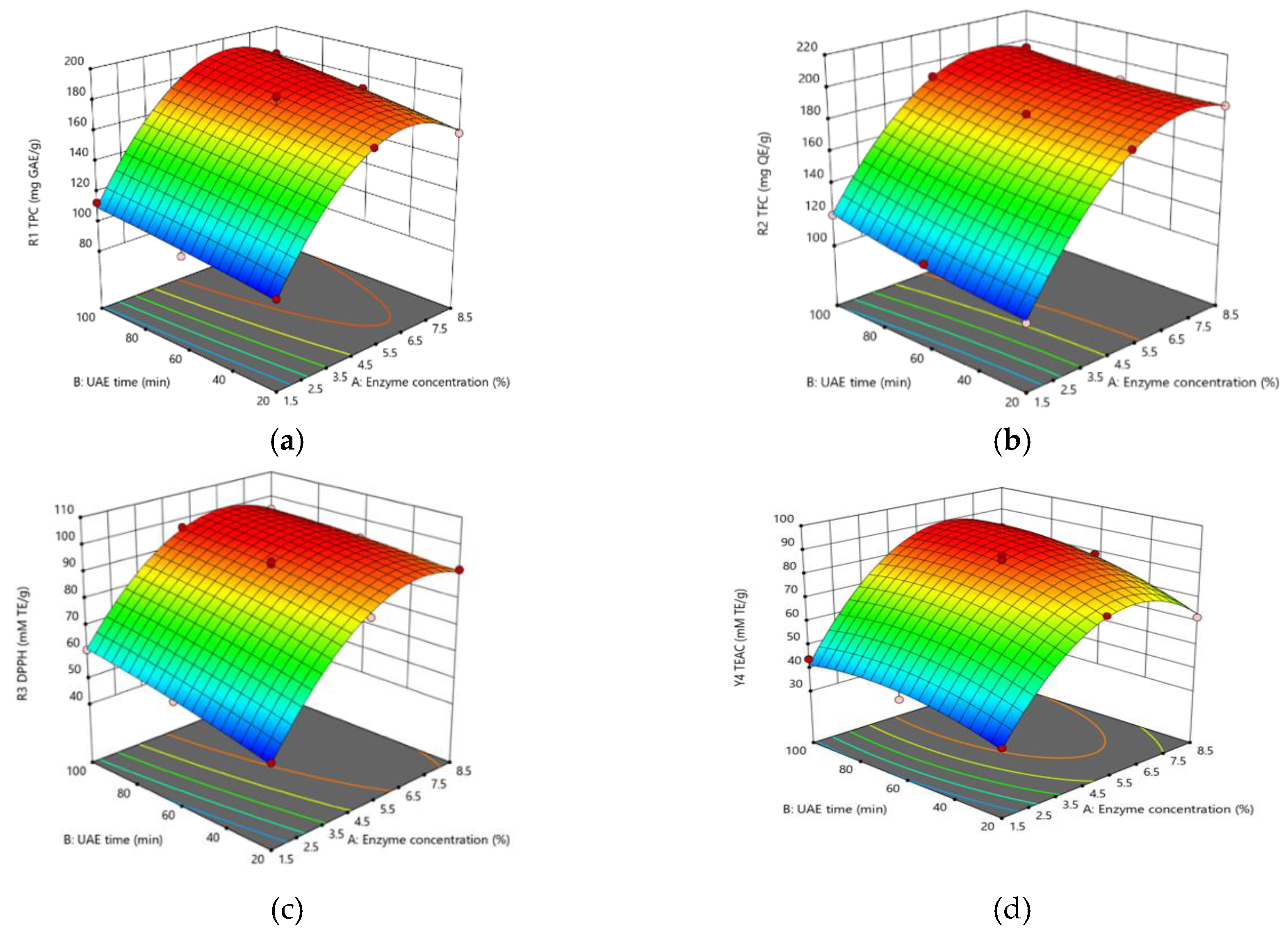

Depending on the enzyme concentration and ultrasonication times used, TPC ranged from 98.1 to 183.6 mg GAE/g, TFC from 102 to 195 mg QE/g, DPPH radical scavenging activity from 48.9 to 97.1 mM TE/g, and TEAC from 35.1 to 88.6 mM TE/g (

Table 3). TPC and TFC increased with increasing enzyme concentrations and longer ultrasonication times (

Figure 1a, b) [

24]. The highest TPC (183.6 mg GAE/g) was achieved at 5% enzyme concentration with 60 min of ultrasonication, and the highest TFC (195.0 mg QE/g) at 8.5%

enzyme concentration with 10 min of extraction time. These findings suggest that enzyme concentration and ultrasonication time substantially affect the extraction of turmeric bioactives, consistent with prior findings [

25]. DPPH radical scavenging activity increased with increasing enzyme concentration and declining ultrasonication time (

Figure 1c), with the greatest activity (97.1 mM TE/g DPPH) obtained at 5% enzyme concentration with 10 min of ultrasonication. The highest TEAC (88.6 mM TE/g) was described in the experimental run of X

1 (5%) and X

2 (60 min).

3.3. Optimization of Extraction Conditions and Process Validation

The optimized extraction conditions, determined using the CCD method, were an 8.14% enzyme concentration with 100 min of ultrasonication. By aiming to maximize the response variables, the optimized conditions were obtained. The optimal extraction conditions were validated experimentally and the results were compared with the values predicted via RSM model (

Table 4). The predicted values for the dependent variables were as follows: TPC at 184.2 mg GAE/g, TFC at 197.1 mg QE/g, DPPH radical scavenging activity at, 97.1 mM TE/g, and TEAC at 84.8 mM TE/g. The experimentally obtained values were 184.6 mg GAE/g for TPC, 198.2 mg QE/g for TFC, 97.1 mM TE/g for DPPH, and 84.7 mM TE/g for TEAC, all of which were consistent with the predicted values. The absolute residual errors for all variables were less than 1%, confirming the accuracy of the predictive model (

Table 4).

3.4. Bioactivity

3.4.1. Anti-Inflammatory Potential

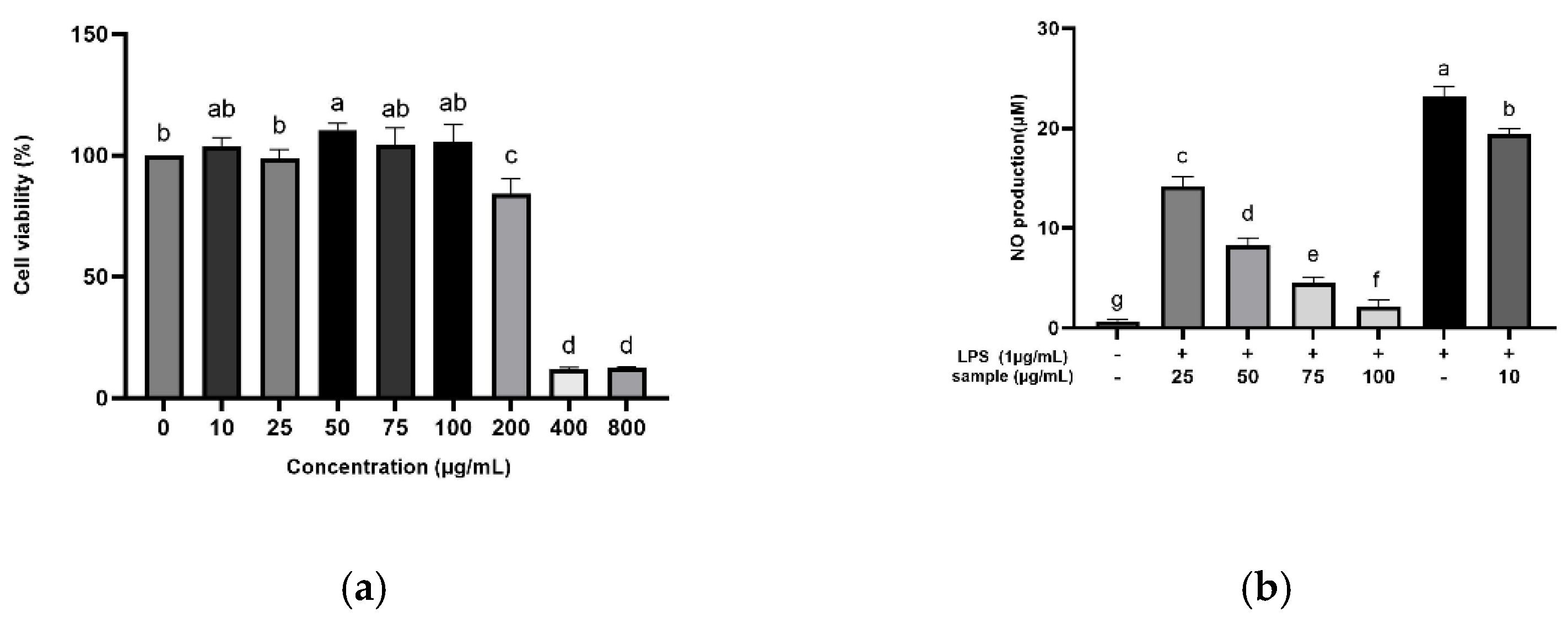

The anti-inflammatory potential of the optimized turmeric extract was investigated via MTT assay (

Figure 2). At levels up to 100 µg/mL, the optimized extract exhibited no cytotoxic effects on RAW 264.7 cell viability (

Figure 2a), consistent with prior findings for curcumin and curcumin diglutaric acid [

26]. These findings indicate that 100 µg/mL is the maximum turmeric extract concentration that can be used without damaging cell viability and integrity. The optimized extract’s inhibitory effect on LPS-induced nitric oxide production by RAW 264.7 cells was examined (

Figure 2b). LPS-treated cells exhibited higher nitric oxide levels, peaking at 23 μM, compared with 0.6 μM in the control. Nitric oxide production was significantly lower at higher concentrations of the optimized extract, declining from 14 μM nitric oxide at 25 μg/mL of the extract to 2 μM at 100 μg/mL, consistent with prior findings [

27].

3.4.2. Antidiabetic Potential

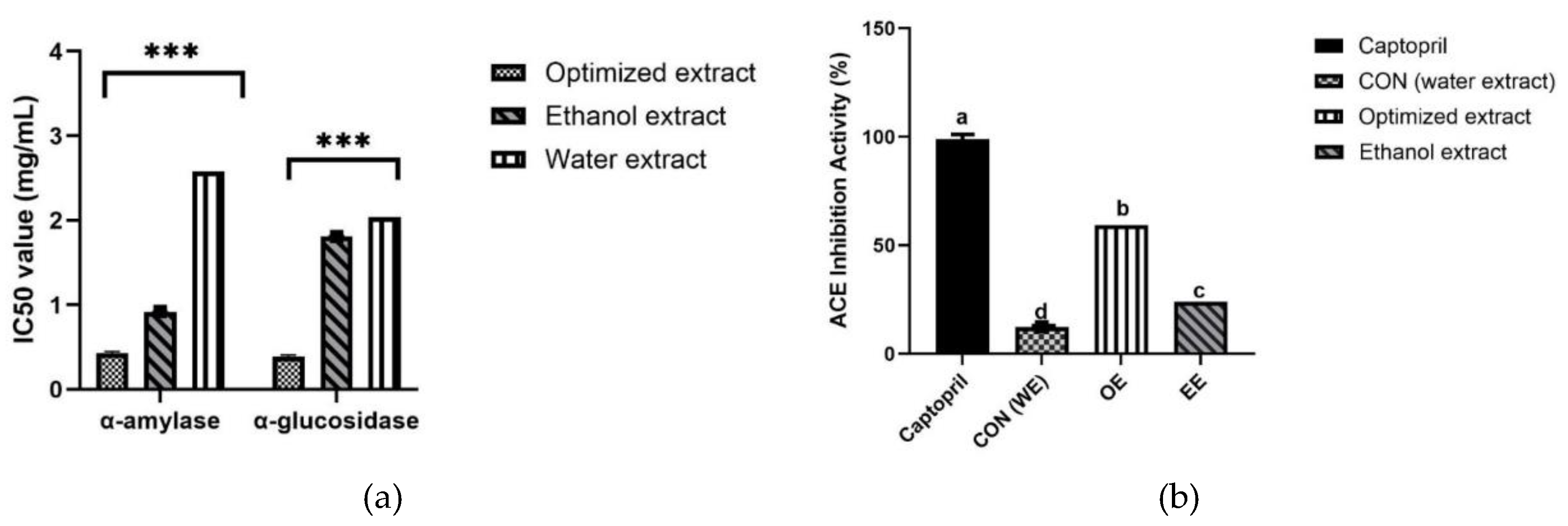

The antidiabetic potential of the turmeric extracts obtained using the optimized approach, using water, or using ethanol, was evaluated in terms of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (

Figure 3a). For α-amylase, the optimized extract achieved 76.3% inhibition (IC

50, 0.43 mg/mL), whereas the standard drug acarbose achieved 98.1% inhibition (IC

50, 0.2 mg/mL). The ethanol-derived extract achieved 58.3% inhibition (IC

50, 0.92 mg/mL), whereas the water-derived extract achieved the lowest inhibition, of 25.2%, with an IC

50 of 2.58 mg/mL.

The α-glucosidase inhibition assay revealed similar results, with the optimized extract achieving the highest inhibition, of 78.9% (IC50, 0.39 mg/mL); the ethanol-derived extract achieved 43.11% inhibition (IC50, 1.81 mg/mL) and the water-derived extract achieved 28.07% inhibition (IC50, 2.04 mg/mL).

3.4.3. ACE-Inhibitory Potential

The ACE-inhibitory activity of the optimized extract, water-derived extract, and ethanol-derived extracts was compared with that of captopril, an ACE inhibitor (

Figure 3b). The optimized extract achieved significantly greater inhibition (59.35%) than the ethanol- and water-derived extracts (24% and 12.41%, respectively). Captopril achieved the highest inhibition (98.81%), followed by the optimized extract (59.34%), the ethanol-derived extract (24.1%), and the water-derived extract (12.42%). The optimized extract achieved better inhibitory activity than the other extracts, indicating its superior antihypertensive potential.

3.5. Discussion

This study targeted to optimize turmeric extraction conditions, revealing that increasing the concentration of the extraction enzymes and the ultrasonication times improved the release of bioactives and the antioxidant capacity of the extract. These findings indicate that enzyme-assisted ultrasonic extraction, which increases the concentration and bioavailability of the active ingredients, and particularly of curcuminoids, may enhance the many benefits offered by curcumin and turmeric. Similarly, prior findings have suggested that extending the ultrasonication time improves the extraction efficiency of bioactives [

28]. Longer ultrasonication times enhance plant cell wall breakdown and facilitate the release of flavonoids and phenolic compounds [

23]. Similarly, higher enzyme concentrations promote cell wall degradation, making the target compounds more accessible and increasing their extraction yields. The combined application of enzymatic and ultrasonic extraction synergistically enhanced extraction efficiency, thus enhancing antioxidant capacity. By optimizing the α-amylase concentration and ultrasonication time, this integrated approach offers a promising green extraction method for turmeric. Process validation revealed the effectiveness of the RSM approach and the optimal extraction conditions for maximizing bioactive component levels in the turmeric extracts. The predicted and experimentally obtained values were similar, indicating the accuracy of the optimized model [

13].

Based on the cytotoxicity assay, this optimized turmeric extract can be used at up to 100 μg/mL without reducing cell viability or integrity. The optimized extract effectively suppressed LPS-induced nitric oxide production, suggesting its anti-inflammatory potential. The presence in the optimized extract of curcumin, which exhibits anti-inflammatory activity, may explain this result. In LPS-induced macrophage cells, curcumin prevented cytotoxicity and reduced nitric oxide production [

29]. Owing to its ability to reduce nitric oxide generation, turmeric extract can potentially reduce inflammation associated with diseases such as arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and neurological disorders.

The potential antidiabetic effects of the optimized turmeric extract were examined by analyzing its inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity. These enzymes, which regulate blood glucose levels, offer potential as therapeutic targets in managing diabetes. In both inhibitory assays, the optimized extract achieved lower IC

50 values than the other types of extracts, suggesting greater inhibitory capacity. The optimized turmeric extract can thus effectively prevent the breakdown of starch and glucose polymers by α-amylase and α-glucosidase. The superior performance of the optimized extract can be attributed to the greater concentrations and bioactivity levels of its active compounds, making it more effective at inhibiting the target enzymes than the ethanol- or water-derived extracts. This is consistent with prior findings that inhibitory activity was lowest for a water-derived extract and highest for an ultrasound-derived extract [

30].

ACE is essential for controlling blood pressure and prevent hypertension [

36]. The antihypertensive potential of turmeric extracts has been revealed both in vitro and in vivo[

36]. Curcuminoids, including curcumin, monodemethoxycurcumin, and bidemethoxycurcumin, are the major bioactive components in turmeric, exhibiting antihyperglycemic, antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects [

36]. Based on our findings, the optimized extract achieved better inhibition of ACE than the other types of extracts, suggesting its greater potential in managing blood pressure.

4. Conclusions

The conditions for enzyme-assisted ultrasonication extraction were successfully optimized. The response variables, in respect of the levels of bioactives and the antioxidant activity of the extract, varied significantly with enzyme concentration and ultrasonication time. The RSM model performed reliably, and the optimization results were validated experimentally. These findings highlight the improvements in bioactivity that the optimized extract achieves over conventionally derived extracts. Based on these findings, the optimized extract exhibits substantial anti-inflammatory, antihypertensive, and antidiabetic potential. These findings provide valuable insight into the application of turmeric extracts with improved functional properties. These findings reveal the potential of this enhanced extraction approach for improving the bioactivity of turmeric extracts, thus supporting the development of foods with improved functional properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nayab, Thinzar Aung, and Mi Jeong Kim; methodology, Nayab; Software, Nayab, Choon Young Kim, and Thinzar Aung; Validation, Nayab, Thinzar Aung, and Mi Jeong Kim; Formal analysis, Nayab; Investigation, Mi Jeong Kim; Resources, Mi Jeong Kim; Data curation, Nayab, Thinzar Aung, and Choon Young Kim; Writing—original draft preparation, Nayab and Thinzar Aung; Writing—review and editing, Thinzar Aung and Mi Jeong Kim; Visualization, Mi Jeong Kim; Supervision, Mi Jeong Kim; Project administration, Mi Jeong Kim; Funding acquisition, Mi Jeong Kim.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chuysinuan, P.; Pengsuk, C.; Lirdprapamongkol, K.; Thanyacharoen, T.; Techasakul, S.; Svasti, J.; Nooeaid, P. Turmeric herb extract-incorporated biopolymer dressings with beneficial antibacterial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties for wound healing. Polymers (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M.D.; Blázquez, M.A. Curcuma longa L. Rhizome essential oil from extraction to its Agri-food applications. A review. Plants (Basel) 2020, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrar, M.B.; Wallace, H.M.; Brooks, P.; Yule, C.M.; Tahmasbian, I.; Dunn, P.K.; Hosseini Bai, S.H. A performance evaluation of Vis/NIR hyperspectral imaging to predict curcumin concentration in fresh turmeric rhizomes. Remote Sens-Basel 2021, 13, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, K.; Ali, J.; Ansari, M.J.; Raheman, Z. Curcumin: A natural antiinflammatory agent. Indian J Pharmacol 2005, 37, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S.S.; Rao, P.; Rathod, V.K. Enzyme assisted extraction of biomolecules as an approach to novel extraction technology: A review. Food Res Int 2018, 108, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I.; Kabbashi, N.A. Extraction and characterization of bioactive compounds in leaf ethanolic extract comparing Soxhlet and microwave-assisted extraction techniques. J Taibah Univ Sci 2019, 13, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-j.; Gasmalla, M.A.A.; Li, P.; Yang, R. Enzyme-assisted extraction processing from oilseeds: Principle, processing and application. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 2016, 35, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.A.; Kuo, C.H.; Chen, B.Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Chen, J.H.; Shieh, C.J. A novel enzyme-assisted ultrasonic approach for highly efficient extraction of resveratrol from Polygonum cuspidatum. Ultrason Sonochem 2016, 32, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, B.K. Ultrasound: A clean, green extraction technology. TrAC Trends Anal Chem 2015, 71, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahne, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Najafpour, G.D.; Moghadamnia, A.A. Enzyme-assisted ionic liquid extraction of bioactive compound from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.): Isolation, purification and analysis of curcumin. Ind Crops Prod 2017, 95, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Aung, T.; Kim, M.J. Optimization of germination conditions to enhance the antioxidant activity in chickpea (Cicer arietimum L.) using response surface methodology. Korean J Food Preserv 2022, 29, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, G.; Sharangi, A.B.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Al-Keridis, L.A.; Alshammari, N.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Saeed, M. Dynamics of drying turmeric rhizomes (Curcuma longa L.) with respect to its moisture, color, texture and quality. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.; Kim, B.R.; Kim, M.J. Comparative flavor profile of roasted germinated wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) beverages served hot and cold using electronic sensors combined with chemometric statistical analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aadil, R.M.; Zeng, X.A.; Han, Z.; Sun, D.W. Effects of ultrasound treatments on quality of grapefruit juice. Food Chem 2013, 141, 3201–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, T.; Park, S.S.; Cho, S.; Kim, M.J. Elderly-targeted a branched-chain amino acid-enriched snack incorporated with fermented wheat bran: Assessment on physicochemical and sensory characteristics. LWT 2024, 203, 116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, R.; Abraham, A.N.; Shukla, R.; Drummond, C.J.; Greaves, T.L. Cytotoxicity of protic ionic liquids towards the HaCat cell line derived from human skin. J Mol Liq 2020, 314, 113602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Afzal, S.; Wohlmuth, H.; Münch, G.; Leach, D.; Low, M.; Li, C.G. Synergistic anti-inflammatory activity of ginger and turmeric extracts in inhibiting lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ-induced proinflammatory mediators. Molecules 2022, 27, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hester, F.; Verghese, M.; Sunkara, R.; Willis, S.; Walker, L.T. A comparison of the antioxidative and anti-diabetic potential of thermally treated garlic, turmeric, and ginger. Food Nutr Sci 2019, 10, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.K.; De, A.; Bhadra, S.; Mukherjee, P.K. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory potential of standardized Mucuna pruriens seed extract. Pharm Biol 2015, 53, 1614–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Qian, Z.-J.; Kim, S.-K. A novel angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory peptide from tuna frame protein hydrolysate and its antihypertensive effect in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Chem 2010, 118, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciric, A.; Krajnc, B.; Heath, D.; Ogrinc, N. Response surface methodology and artificial neural network approach for the optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from garlic. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 135, 110976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.H.; de Melo, M.M.R.; Portugal, I.; Silva, C.M. Simulation and techno-economic optimization of the supercritical CO extraction of bark at industrial scale. J Supercrit Fluids 2019, 145, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.; Kim, S.J.; Eun, J.B. A hybrid RSM-ANN-GA approach on optimisation of extraction conditions for bioactive component-rich laver (Porphyra dentata) extract. Food Chem 2022, 366, 130689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkani, F.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Dahmoune, F.; Ressaissi, A.; Kadri, N.; Remini, H. Ultrasound assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from a jujube by-product with valuable bioactivities. Processes 2020, 8, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Rathod, V.K. Combined effect of enzyme co-immobilized magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) and ultrasound for effective extraction and purification of curcuminoids from Curcuma longa. Ind Crops Prod 2022, 177, 114385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumsuay, R.; Muangnoi, C.; Dasuni Wasana, P.W.; Hasriadi, O.; Vajragupta, O.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Towiwat, P. Molecular insight into the anti-inflammatory effects of the curcumin ester prodrug curcumin diglutaric acid in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekshmi, P.C.; Arimboor, R.; Nisha, V.M.; Menon, A.N.; Raghu, K.G. In vitro antidiabetic and inhibitory potential of turmeric (Curcuma longa L) rhizome against cellular and LDL oxidation and angiotensin converting enzyme. J Food Sci Technol 2014, 51, 3910–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radziejewska-Kubzdela, E.; Szwengiel, A.; Ratajkiewicz, H.; Nowak, K. Effect of ultrasound, heating and enzymatic pre-treatment on bioactive compounds in juice from Berberis amurensis Rupr. Ultrason Sonochem 2020, 63, 104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, P.; Liu, J.; Lu, C.; Xu, Y.; Xin, Y.; Fu, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Luo, L.; et al. Curcumin promotes degradation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and suppresses its enzyme activity in RAW 264.7 cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2011, 11, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Rathod, V.K. Simultaneous extraction and partial purification of proteins from spent turmeric powder using ultrasound intensified three phase partitioning and its potential as antidiabetic agent. Chem Eng Process Process Intensif 2022, 172, 108788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.-H.; Chen, W.-B.; Shi, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.-X.; Liu, Y.-Q. The underlying mechanisms of curcumin inhibition of hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in rats fed a high-fat diet combined with STZ treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Khatibi Shahidi, F.; Khorsandi, K.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Gul, A.; Balick, V. An update on molecular mechanisms of curcumin effect on diabetes. J Food Biochem 2022, 46, e14358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, S.; Feng, Q.; Xiao, X. Curcumin, a polyphenolic curcuminoid with its protective effects and molecular mechanisms in diabetes and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-F.; Liu, F.; Qiao, M.-M.; Shu, H.-Z.; Li, X.-C.; Peng, C.; Xiong, L. Vasorelaxant effect of curcubisabolanin A isolated from Curcuma longa through the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2022, 294, 115332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, A.; Pourmasoumi, M.; Ghaedi, E.; Sahebkar, A. The effect of curcumin/Turmeric on blood pressure modulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res 2019, 150, 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugraha, R.V.; Ridwansyah, H.; Ghozali, M.; Khairani, A.F.; Atik, N. Traditional herbal medicine candidates as complementary treatments for COVID-19: A review of their mechanisms, pros and cons. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020, 2020, 2560645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).