Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Enhanced extraction efficiency through improved mass transfer

- Reduced extraction time and energy consumption

- Environmentally friendly processing conditions

- Improved selectivity and product quality.

Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials:

2.1.1. Plant Material

2.1.2. Equipment

2.2. Analytical Methods:

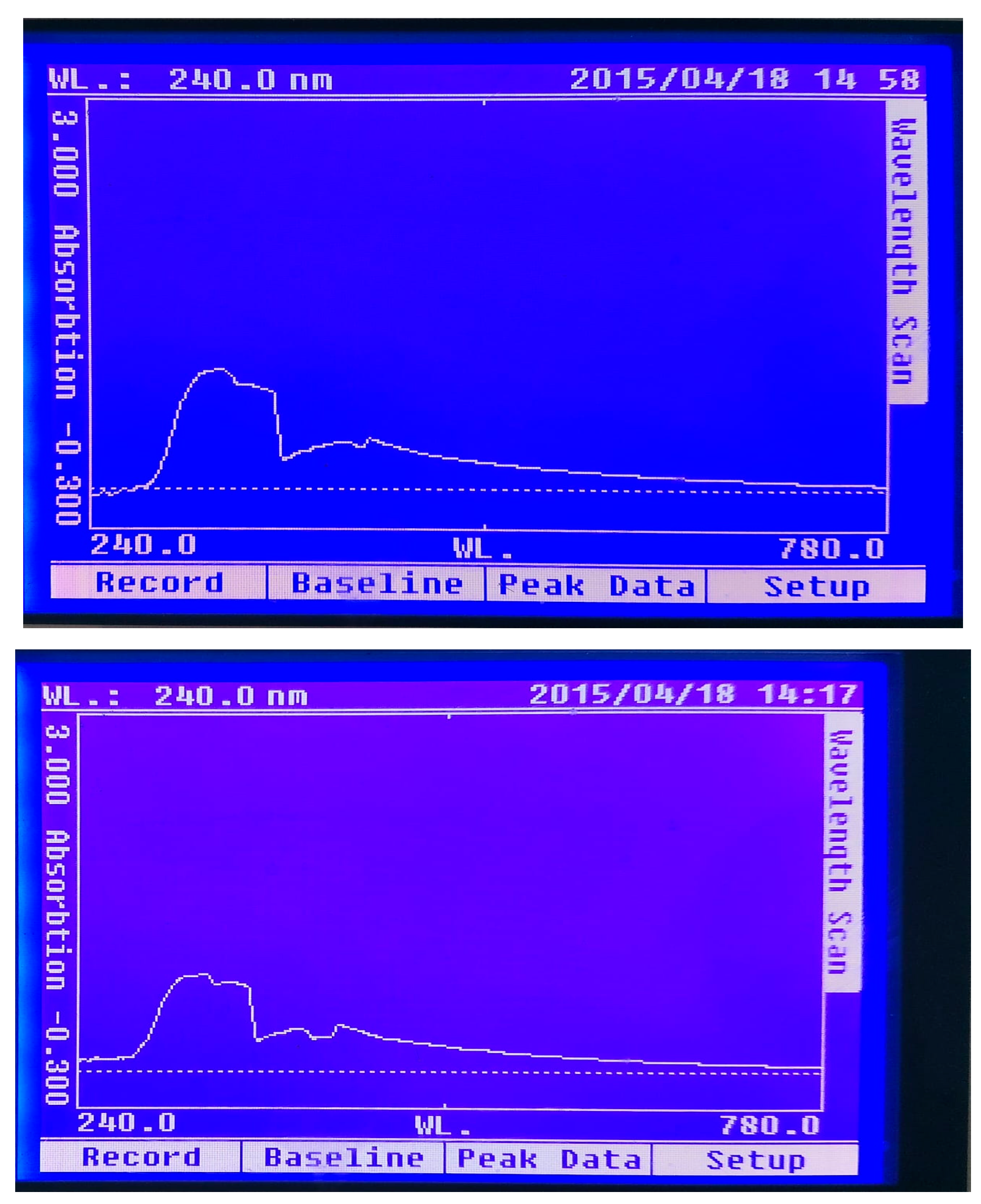

2.2.1. Molar Absorptivity Determination

2.3. Extraction Procedure:

2.3.1. Hydrotropic Solution Preparation

2.3.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Hydrotropic Extraction (UAHE)

2.4. Optimization Studies

2.4.1. Preliminary Studies

2.4.2. Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

- X₁: Hydrotrope concentration

- X₂: Extraction time

- X₃: Solid loading

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results and Discussion

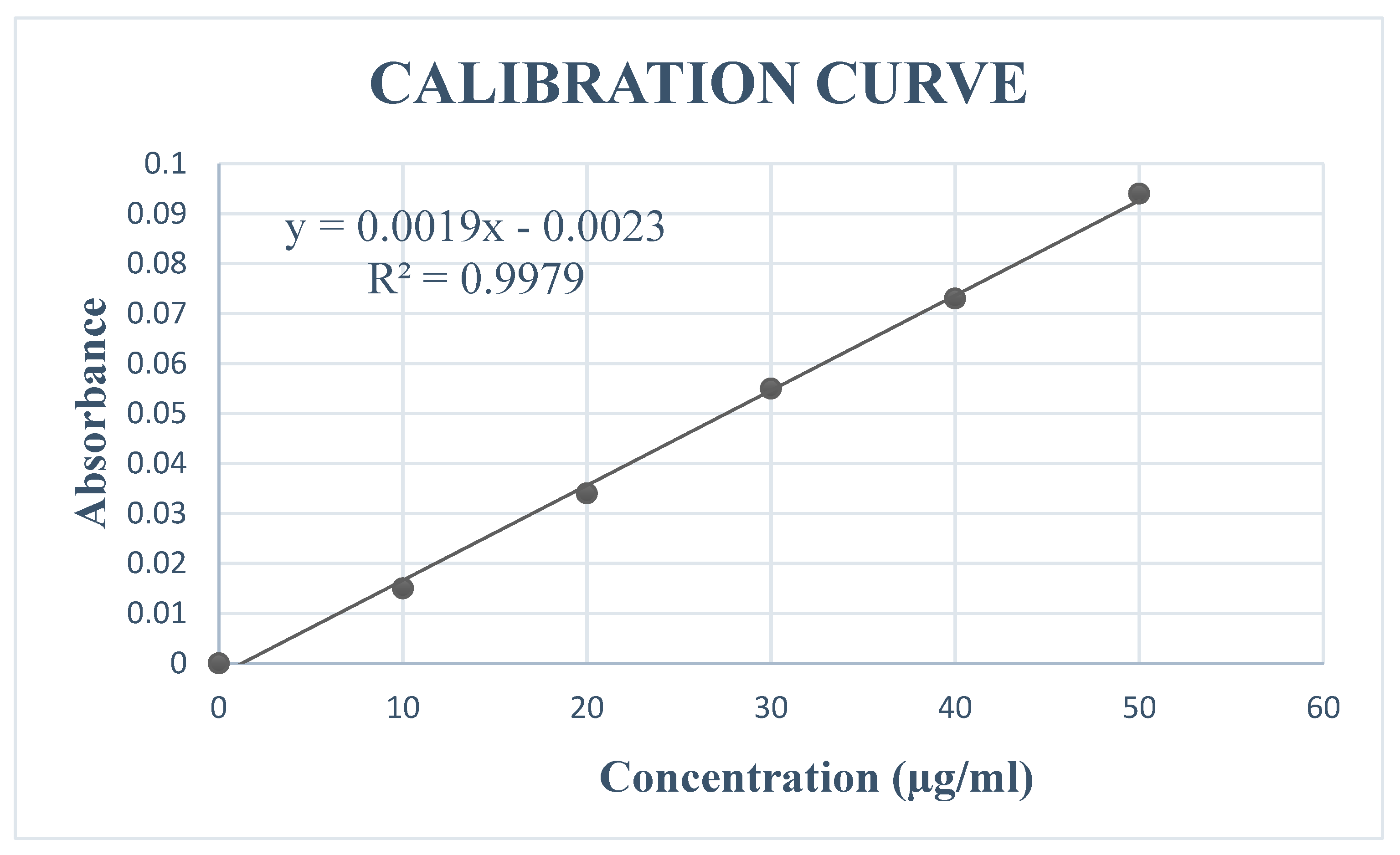

3.1. Molar Absorptivity of Quercetin

| Concentration (µg/ml) | Absorbance |

|---|---|

| 10 | 0.015 |

| 20 | 0.034 |

| 30 | 0.055 |

| 40 | 0.073 |

| 50 | 0.094 |

3.2. Extraction Parameters Range Fixation

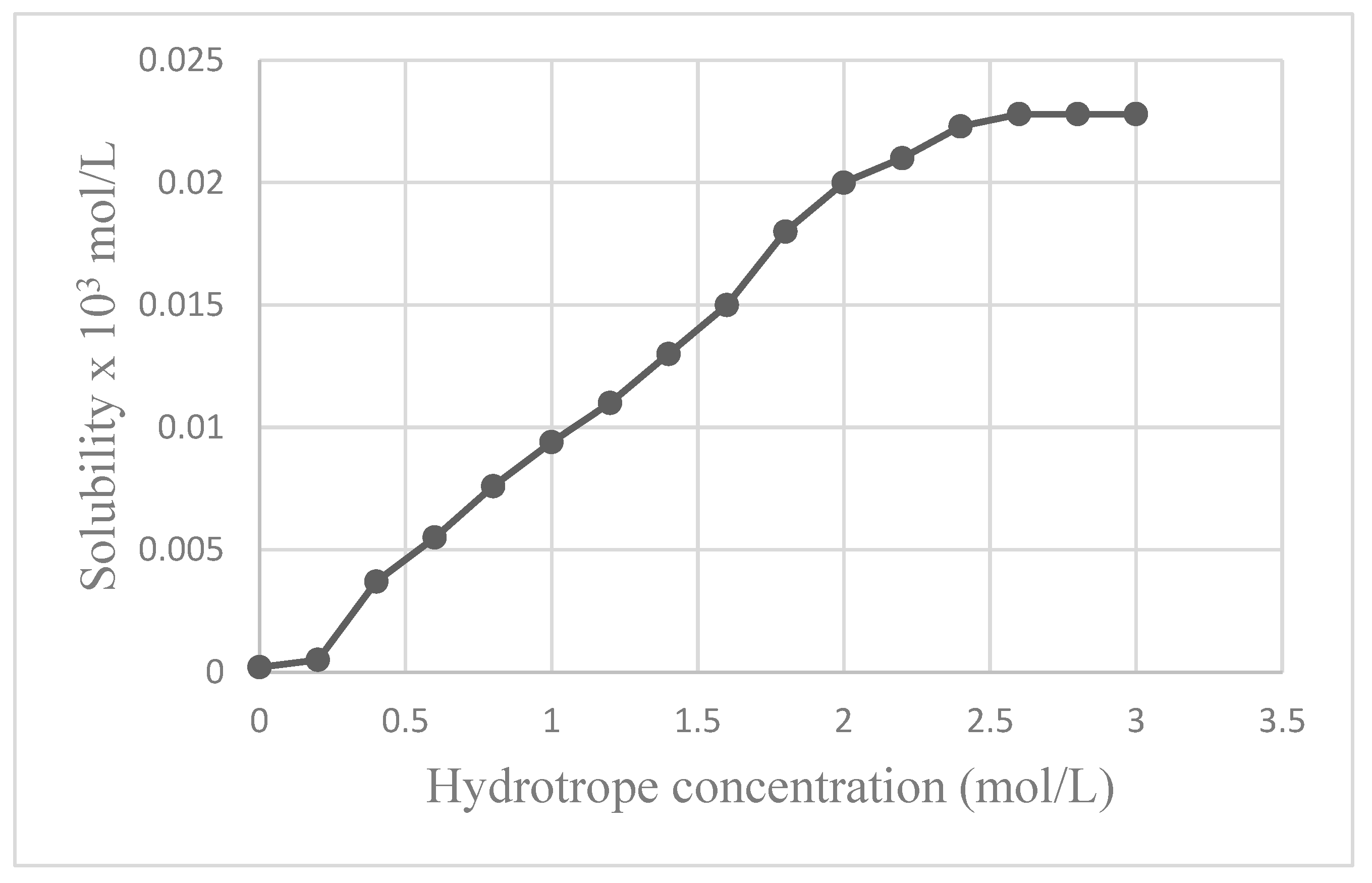

3.2.1. Effect of Hydrotrope on the Solubility of Quercetin

| Hydrotrope Concentration (mol/L) | Solubility x103 mol/L |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0002 |

| 0.2 | 0.0005 |

| 0.4 | 0.0037 |

| 0.6 | 0.0055 |

| 0.8 | 0.0076 |

| 1 | 0.0094 |

| 1.2 | 0.011 |

| 1.4 | 0.013 |

| 1.6 | 0.015 |

| 1.8 | 0.018 |

| 2 | 0.02 |

| 2.2 | 0.021 |

| 2.4 | 0.0223 |

| 2.6 | 0.0228 |

| 2.8 | 0.0228 |

| 3 | 0.0228 |

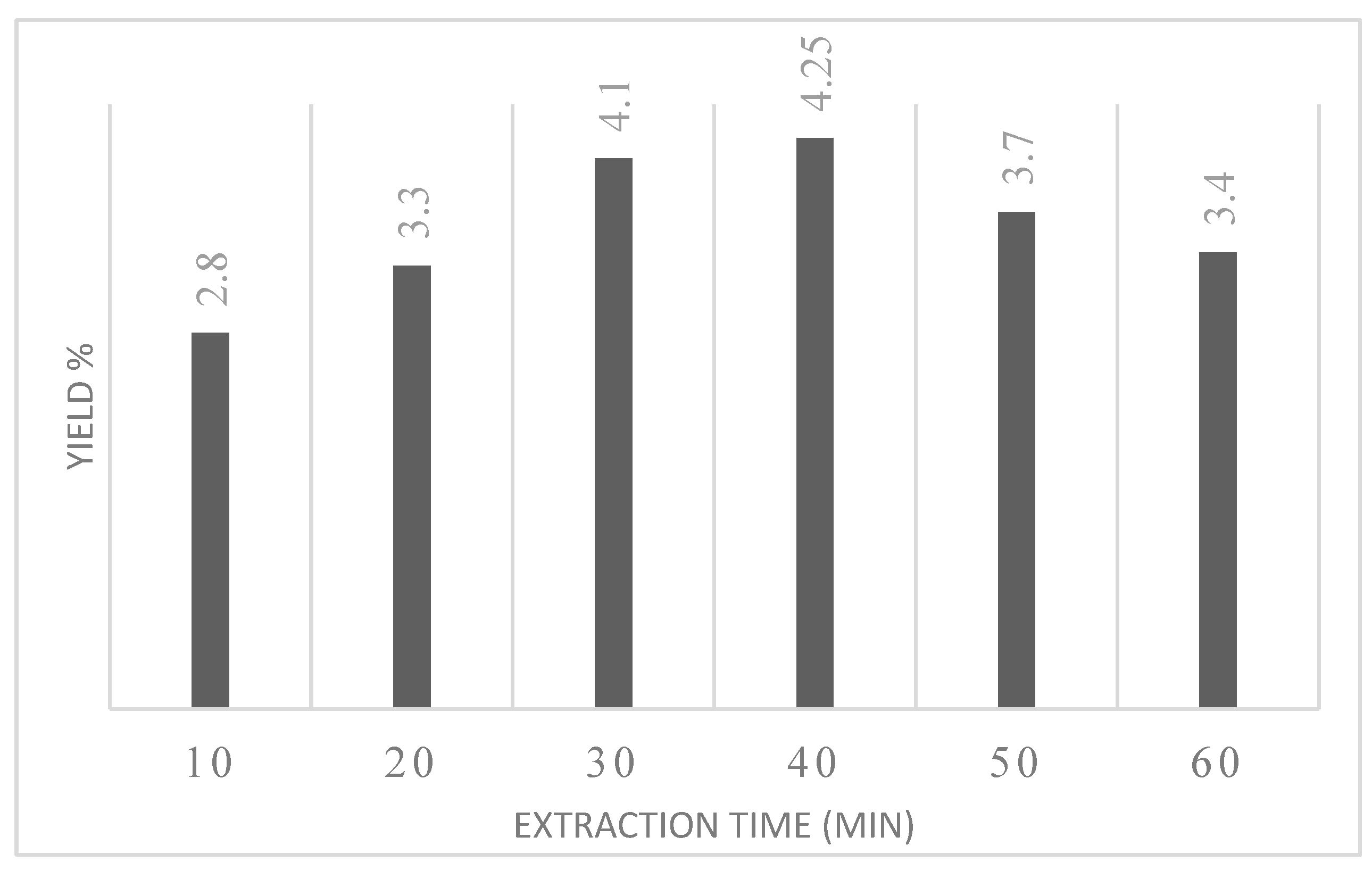

3.2.2. Extraction Time

3.2.3. Raw Material Loading

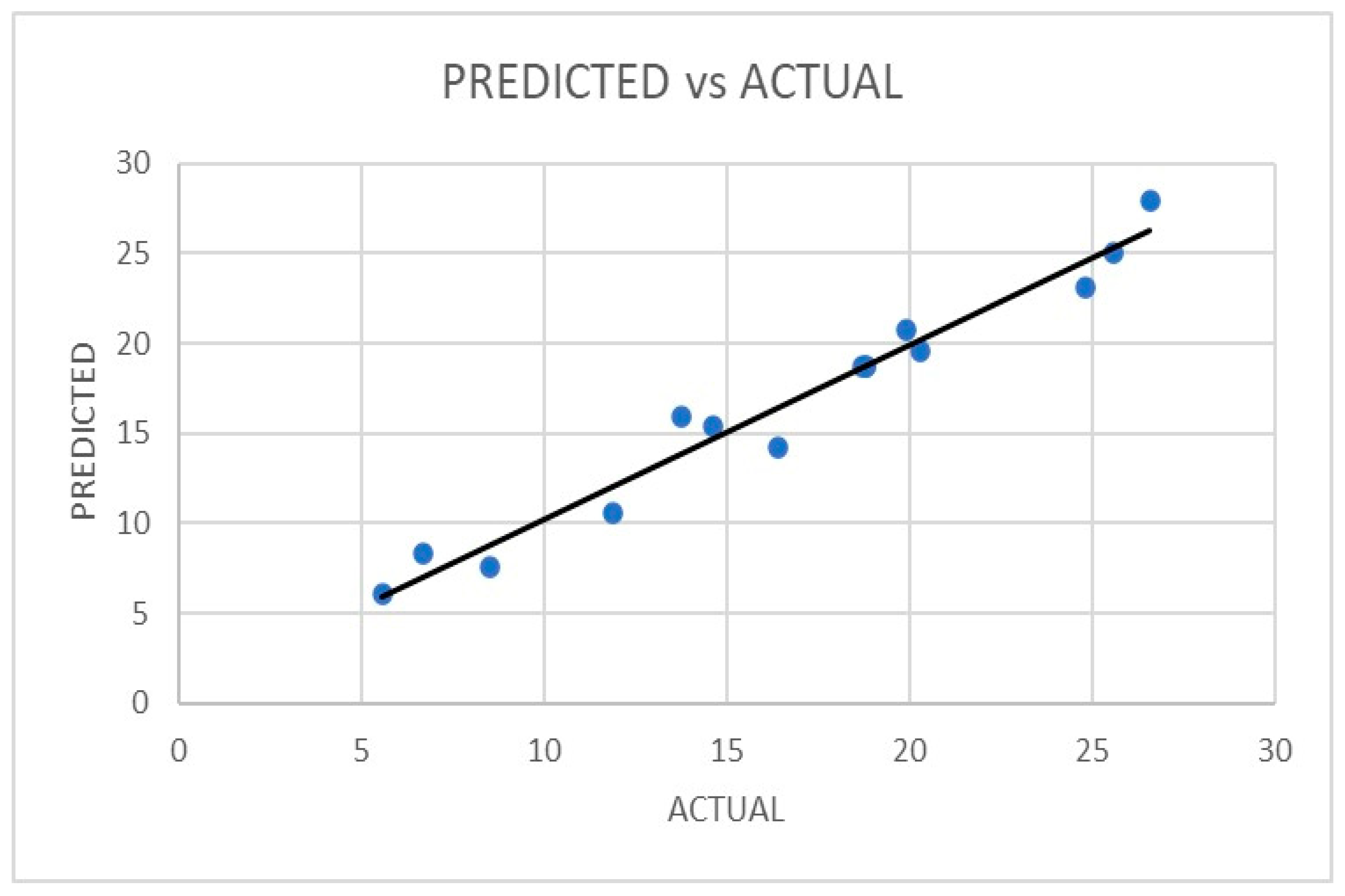

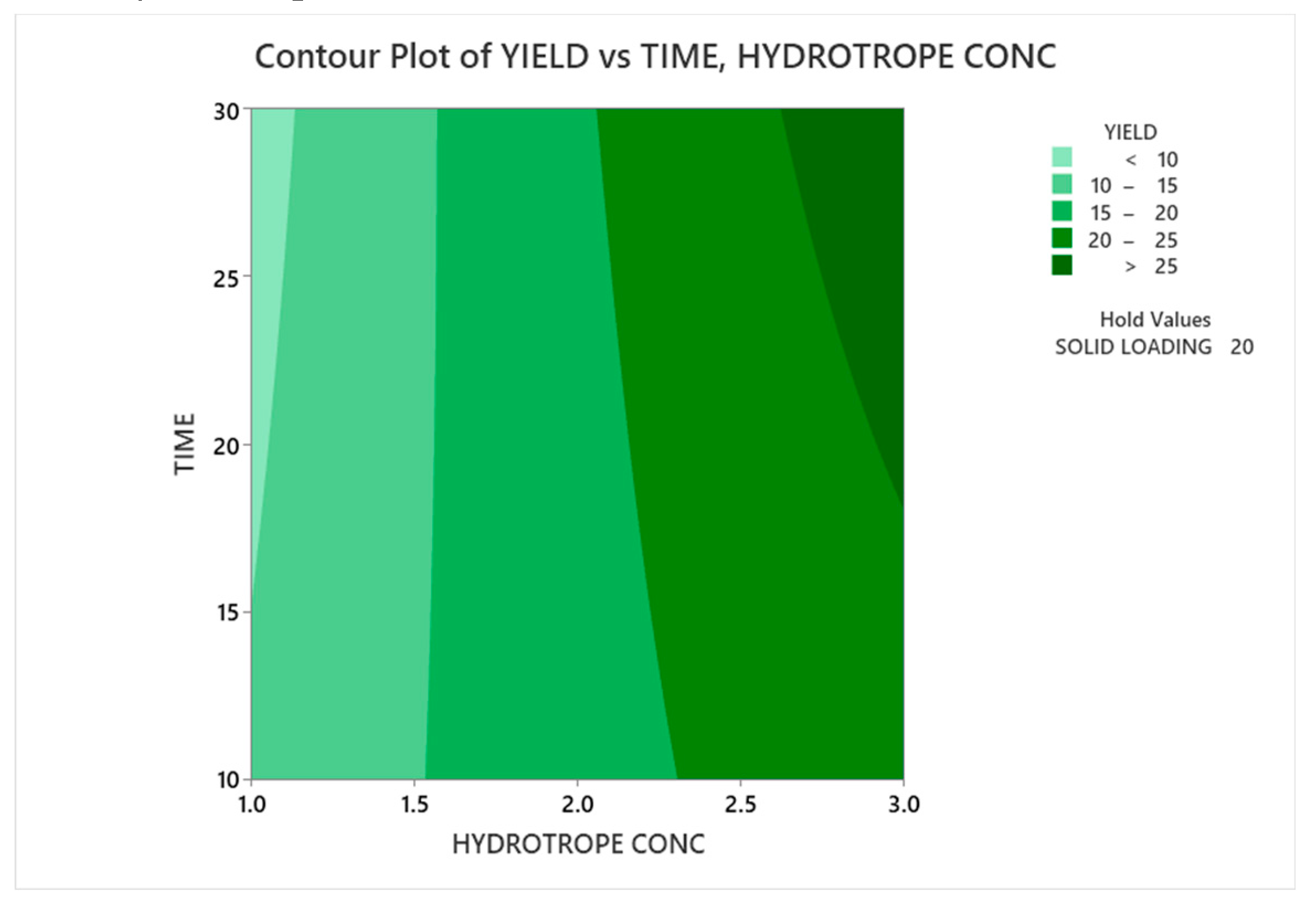

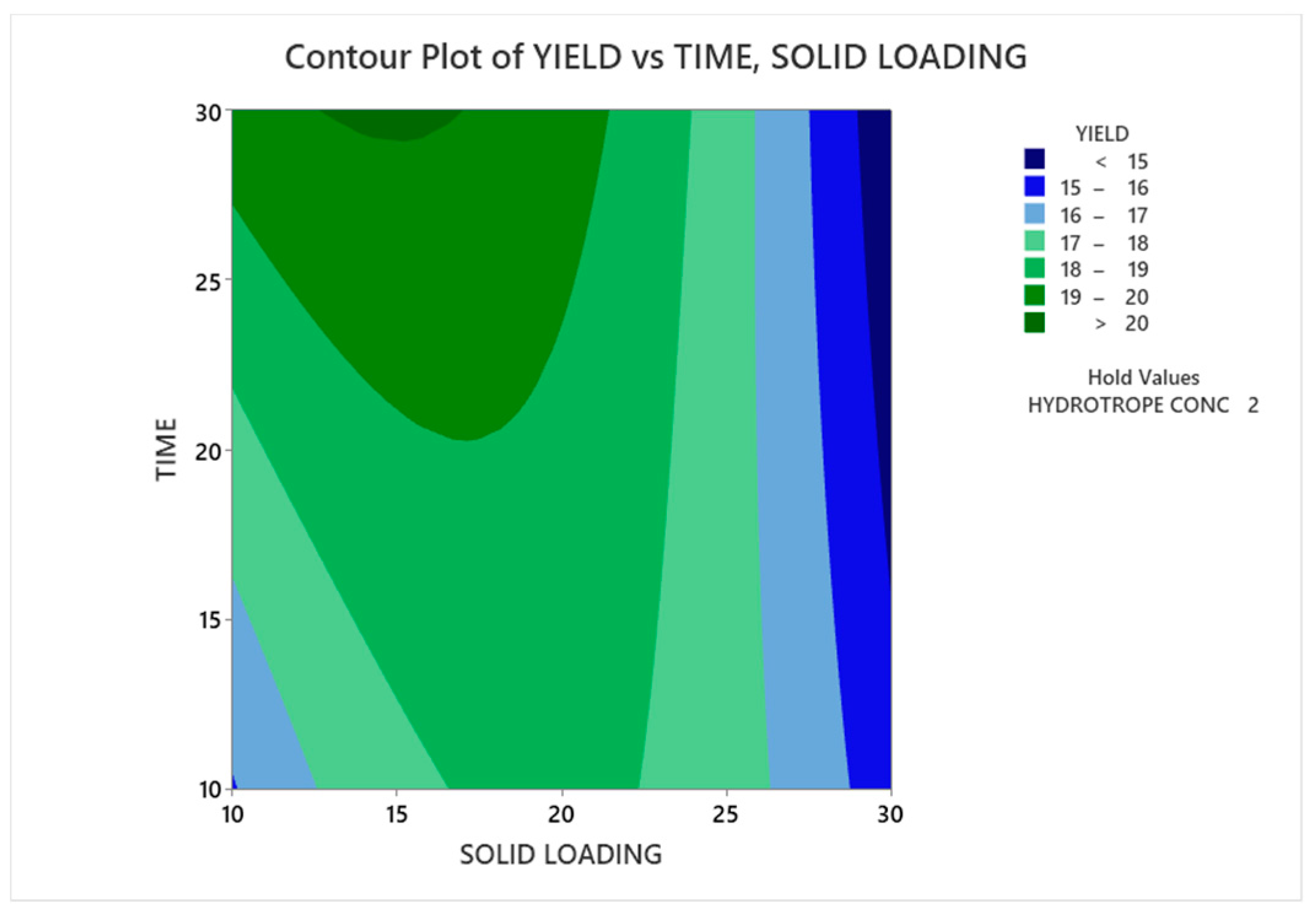

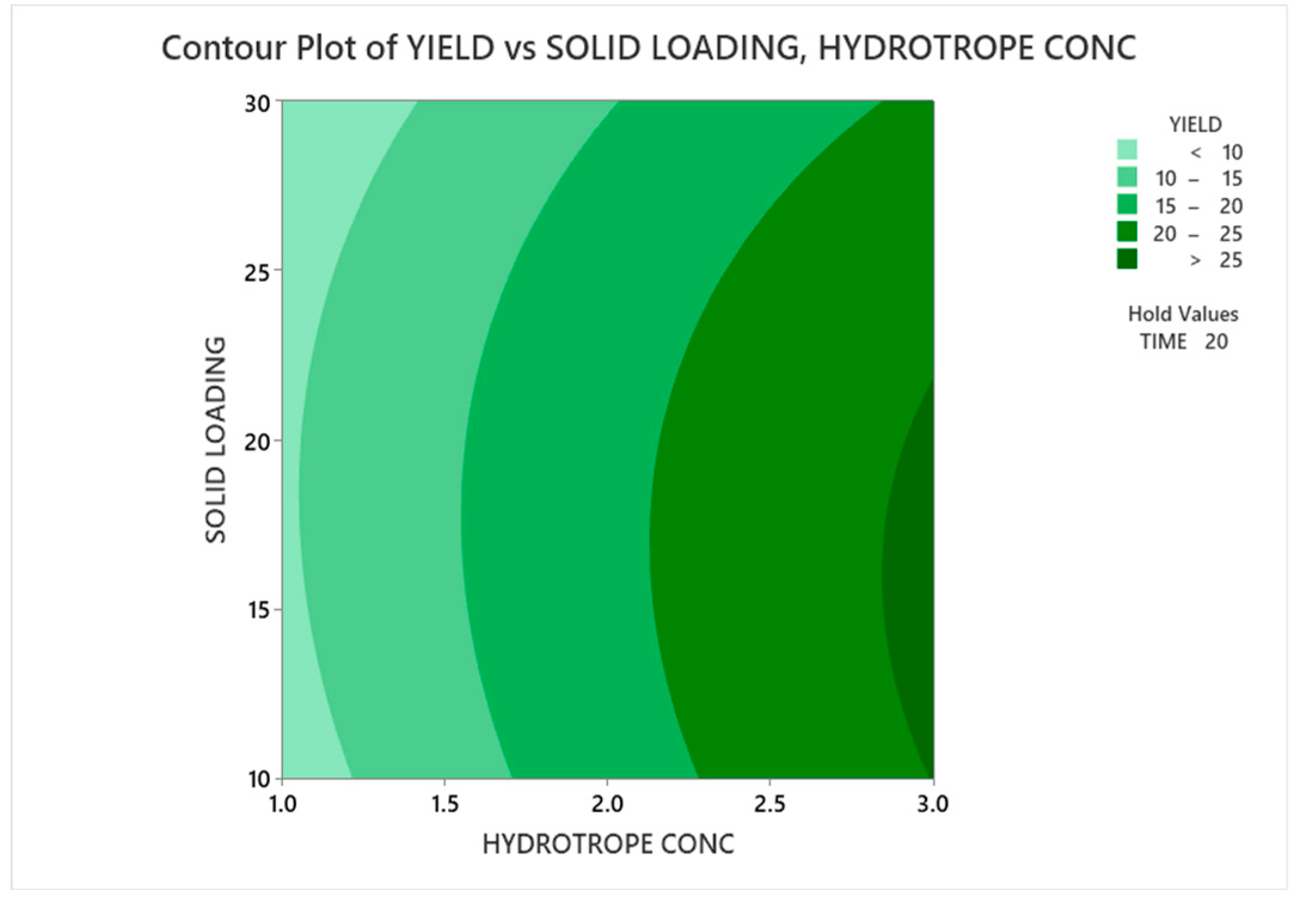

3.3. Response Surface Methodology

3.3.1. Optimization with Sodium Benzoate as Hydrotrope

| Extraction Parameters | Operating Ranges | |

|---|---|---|

| Lowest | Highest | |

| Hydrotrope concentration (mol) | 1 | 3 |

| Extraction Time (min) | 10 | 30 |

| Solid Loading (w/v) | 10 | 30 |

| Run | Hydrotrope Concentration (mol) |

Extraction time (min) |

Solid Loading (% w/v) |

Yield (µg/g) |

| 1 | 3 | 30 | 20 | 26.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 20 | 30 | 19.9 |

| 3 | 1 | 10 | 20 | 11.9 |

| 4 | 3 | 20 | 10 | 25.6 |

| 5 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 18.7 |

| 6 | 2 | 10 | 30 | 14.6 |

| 7 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 18.8 |

| 8 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 13.77 |

| 9 | 1 | 30 | 20 | 6.7 |

| 10 | 2 | 30 | 30 | 16.4 |

| 11 | 1 | 20 | 10 | 8.5 |

| 12 | 1 | 20 | 30 | 5.57 |

| 13 | 3 | 10 | 20 | 24.8 |

| 14 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 18.8 |

| 15 | 2 | 30 | 10 | 20.3 |

| Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | |||||

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 9 | 584.774 | 64.975 | 15.25 | 0.004 |

| Linear | 3 | 535.836 | 178.612 | 41.92 | 0.001 |

| Hydrotrope Concentration | 1 | 515.687 | 515.687 | 121.03 | 0 |

| Time | 1 | 3.038 | 3.038 | 0.71 | 0.437 |

| Solid Loading | 1 | 17.111 | 17.111 | 4.02 | 0.101 |

| Square | 3 | 29.177 | 9.726 | 2.28 | 0.197 |

| A2 | 1 | 6.442 | 6.442 | 1.51 | 0.274 |

| B2 | 1 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0 | 0.962 |

| C2 | 1 | 24.072 | 24.072 | 5.65 | 0.063 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 3 | 19.761 | 6.587 | 1.55 | 0.312 |

| AB | 1 | 12.25 | 12.25 | 2.87 | 0.151 |

| AC | 1 | 1.918 | 1.918 | 0.45 | 0.532 |

| BC | 1 | 5.593 | 5.593 | 1.31 | 0.304 |

| Error | 5 | 21.305 | 4.261 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 3 | 21.298 | 7.099 | 2129.79 | 0 |

| Pure Error | 2 | 0.007 | 0.003 | ||

| Total | 14 | 606.079 | |||

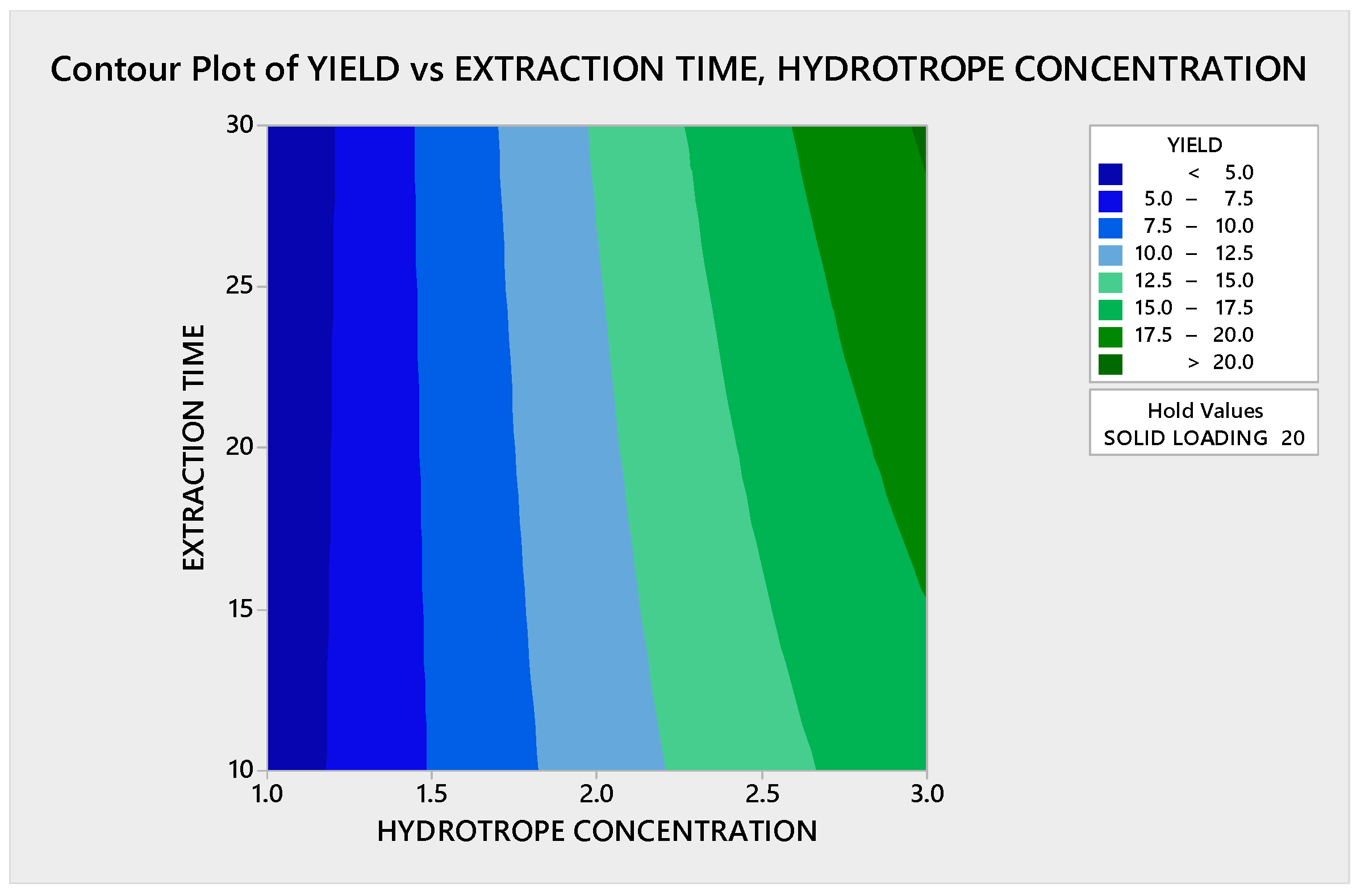

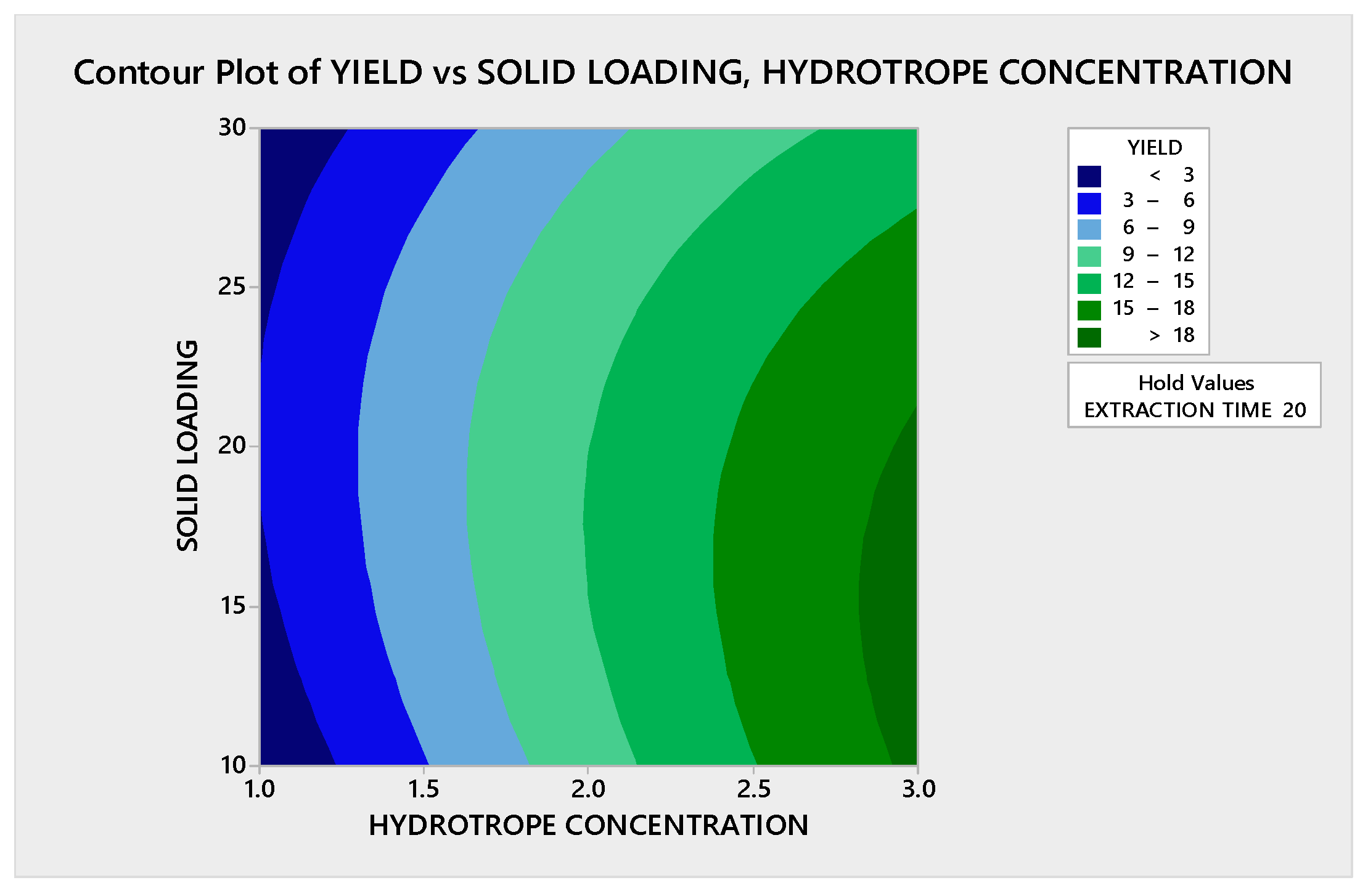

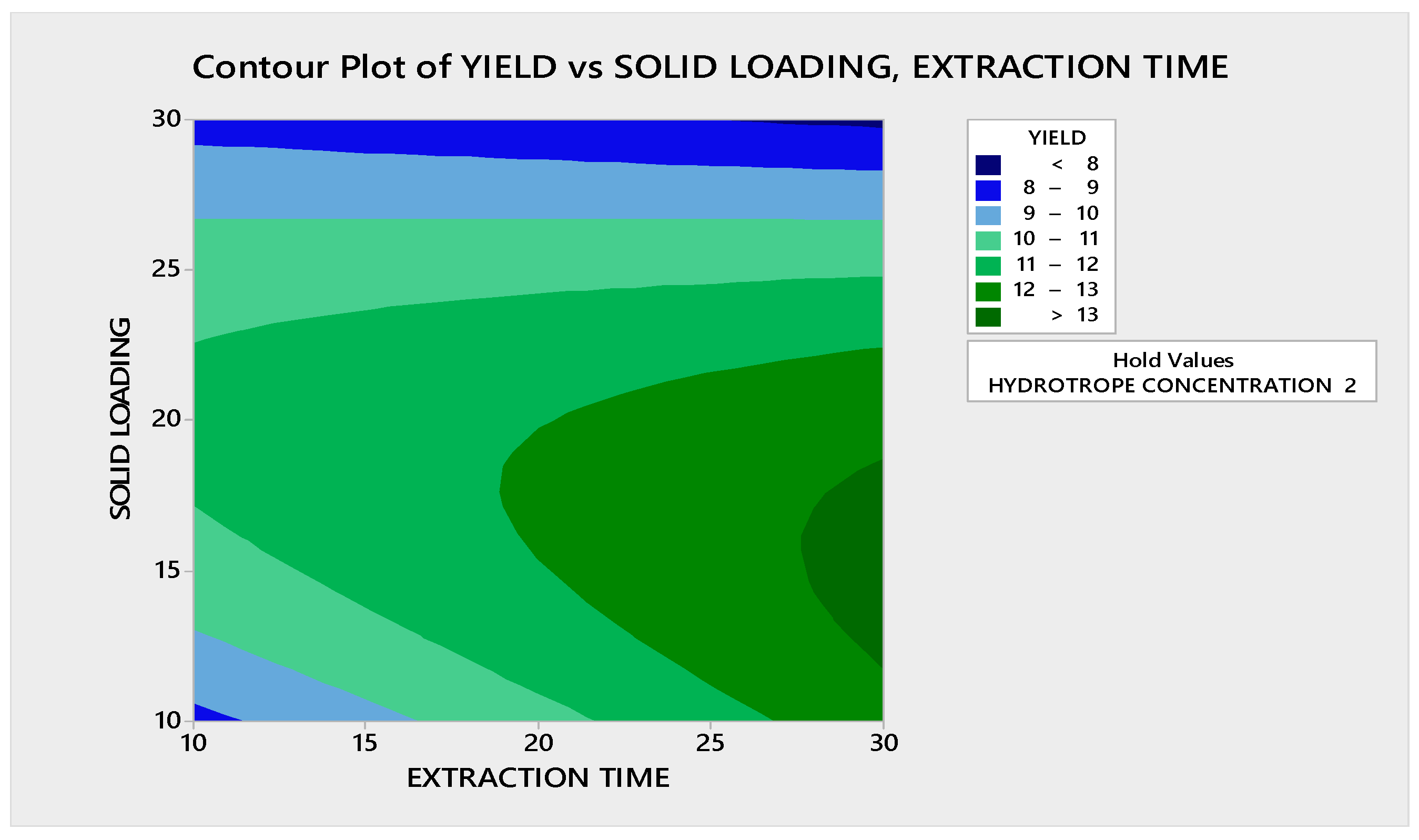

3.3.1.1. Contour Plot Analysis

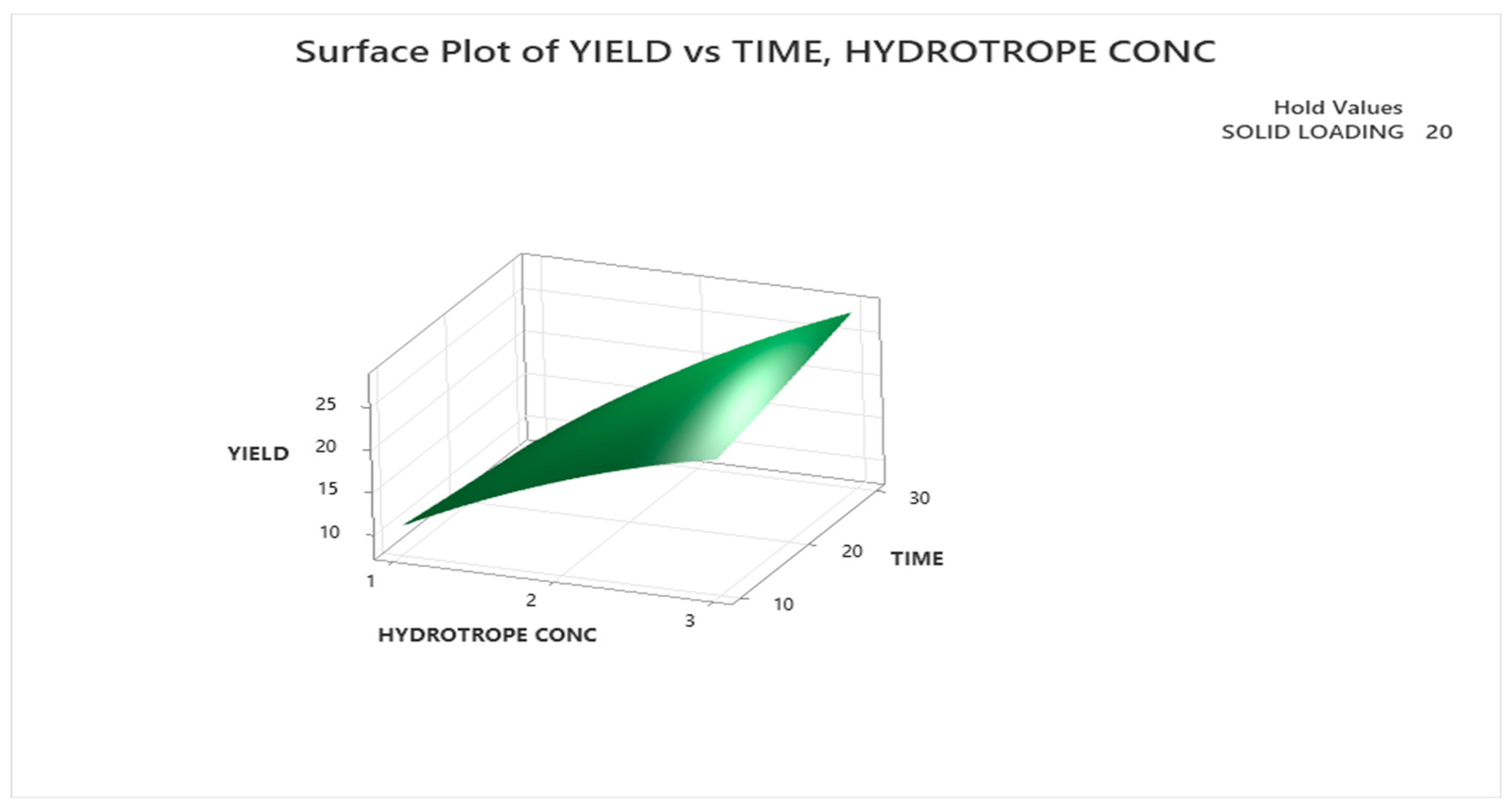

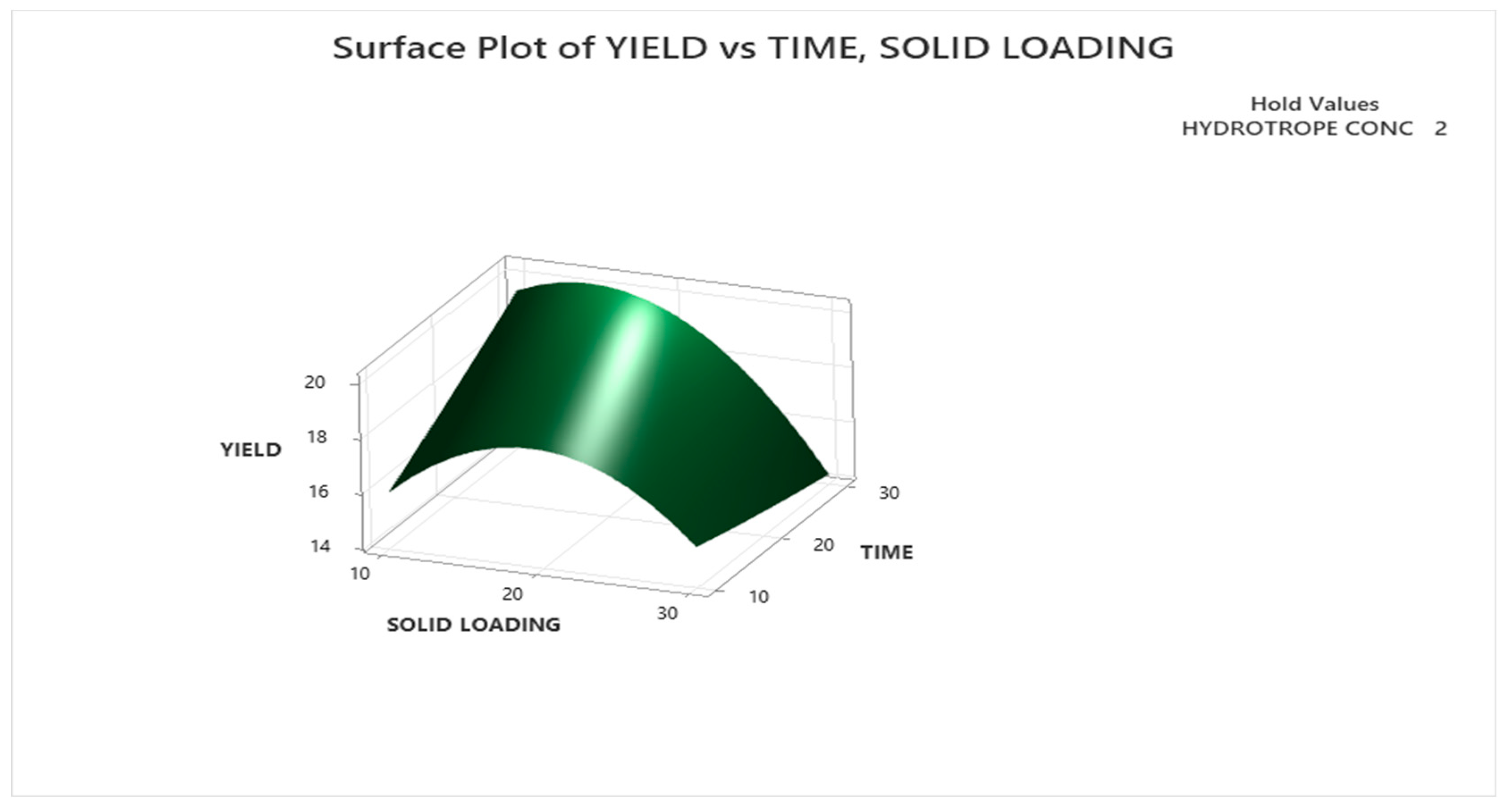

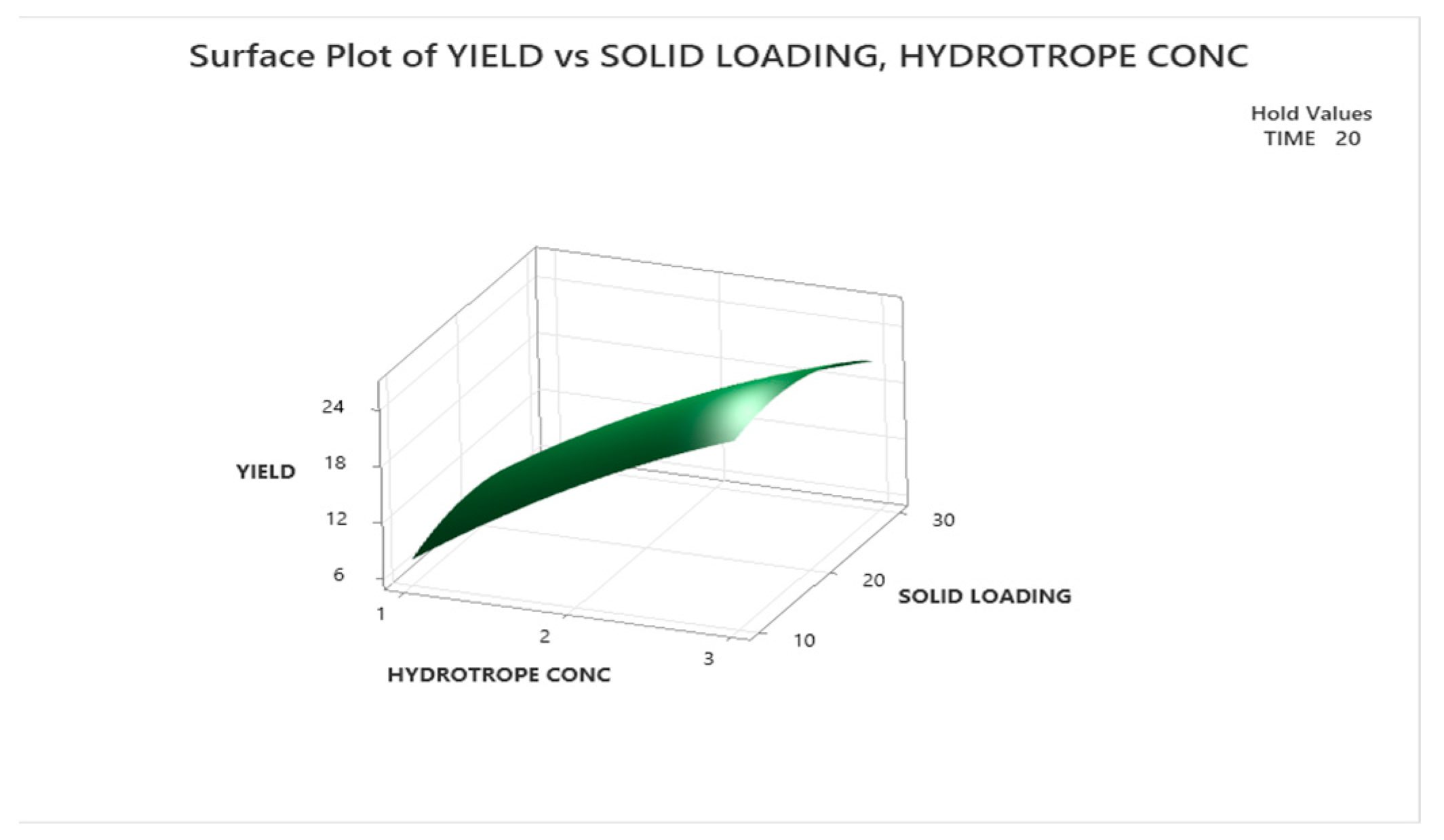

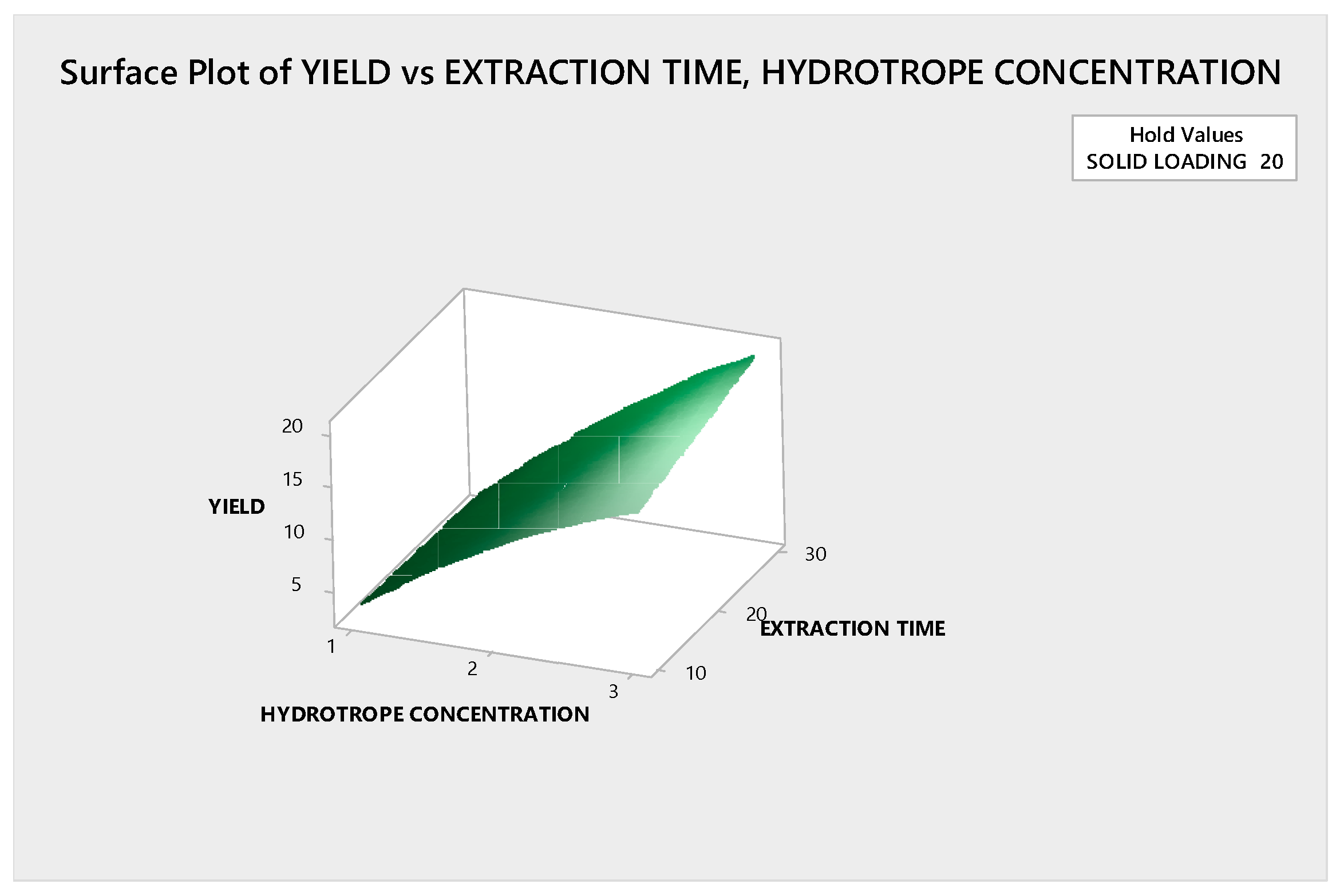

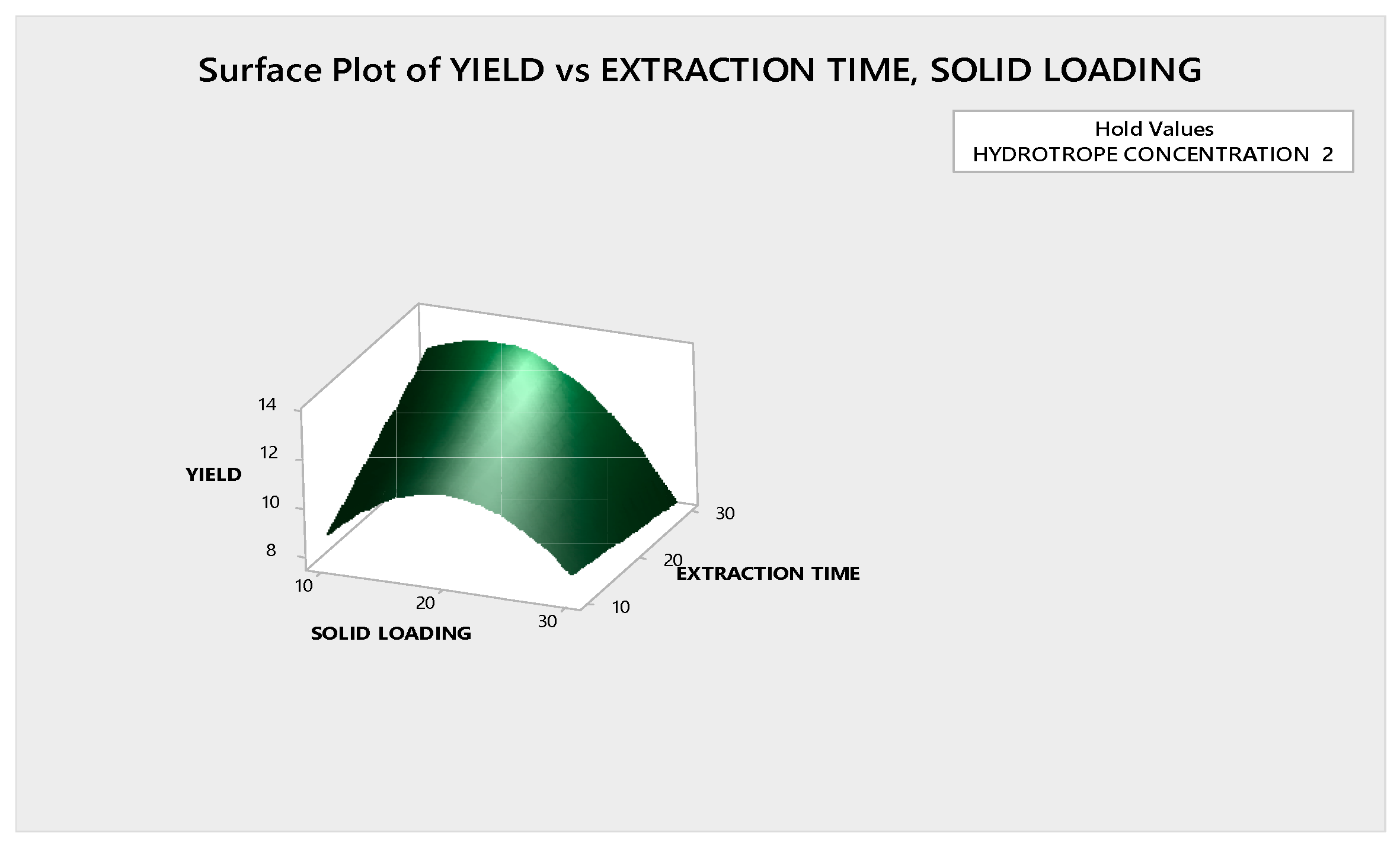

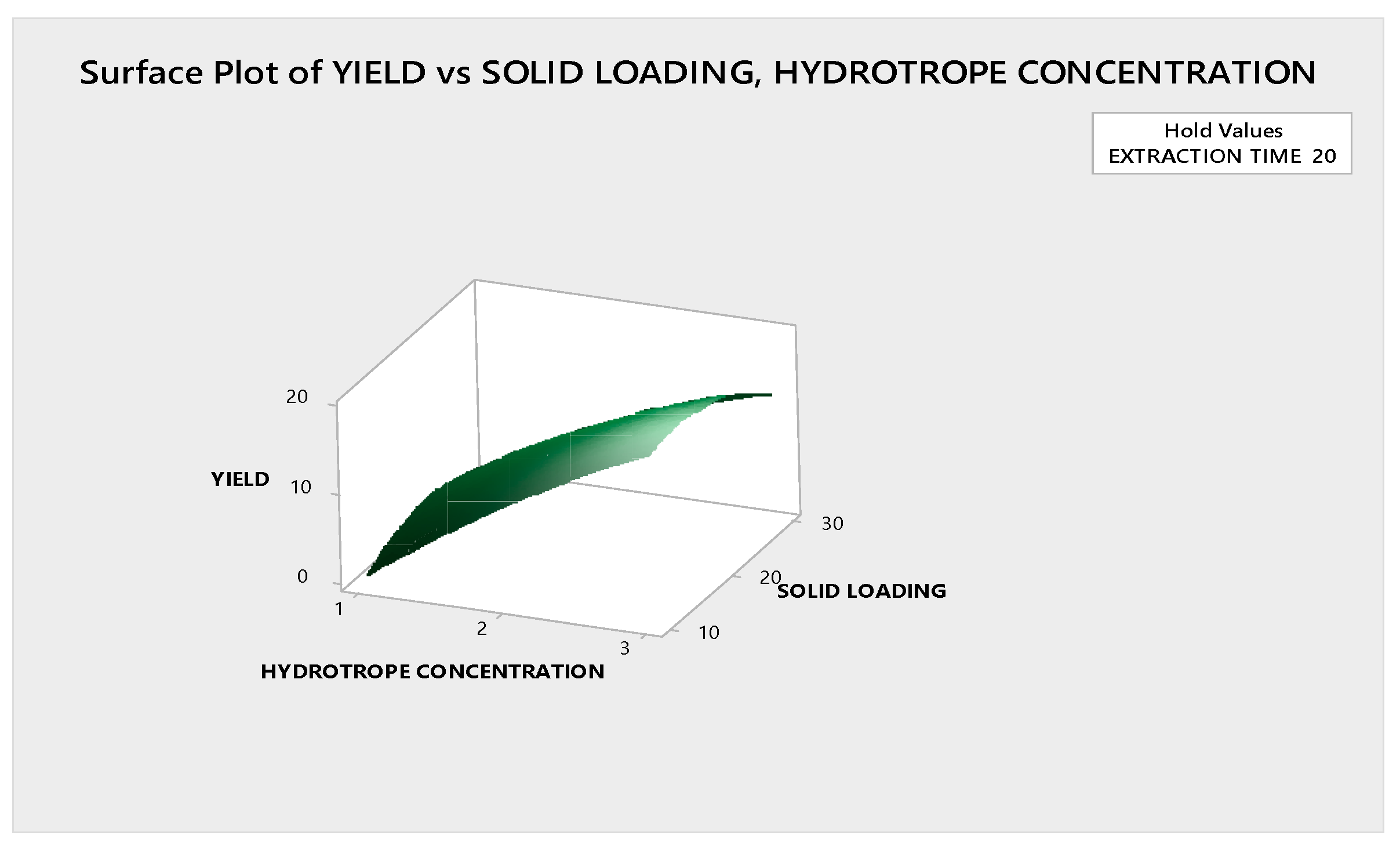

3.3.1.2. Response Surface Plot Analysis

3.3.2. Optimization with Urea as Hydrotrope

| Extraction Parameters | Operating Ranges | |

|---|---|---|

| Lowest | Highest | |

| X1 - Hydrotrope concentration (mol) | 1 | 3 |

| X2 -Extraction Time (min) | 10 | 30 |

| X3 - Solid Loading (w/v) | 10 | 30 |

| Run | Hydrotrope Concentration (mol) |

Extraction time (min) |

Solid Loading (% w/v) |

Yield (µg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 30 | 30 | 9.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 20 | 30 | 12.5 |

| 3 | 1 | 10 | 20 | 4.5 |

| 4 | 2 | 10 | 30 | 7.8 |

| 5 | 3 | 20 | 10 | 18.8 |

| 6 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 11.9 |

| 7 | 3 | 10 | 20 | 18 |

| 8 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 12 |

| 9 | 3 | 30 | 20 | 19.2 |

| 10 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 12 |

| 11 | 1 | 30 | 20 | 1.2 |

| 12 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 6.9 |

| 13 | 1 | 20 | 10 | 1.07 |

| 14 | 1 | 20 | 30 | 0.43 |

| 15 | 2 | 30 | 10 | 13.4 |

| Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | |||||

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 9 | 533.169 | 59.241 | 18.60 | 0.002 |

| Linear | 3 | 486.619 | 162.206 | 50.92 | 0.000 |

| Hydrotrope Concentration | 1 | 469.711 | 469.711 | 147.45 | 0.000 |

| Time | 1 | 4.805 | 4.805 | 1.51 | 0.274 |

| Solid Loading | 1 | 12.103 | 12.103 | 3.80 | 0.109 |

| Square | 3 | 27.956 | 9.319 | 2.93 | 0.139 |

| A2 | 1 | 5.616 | 5.616 | 1.76 | 0.242 |

| B2 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.993 |

| C2 | 1 | 23.696 | 23.696 | 7.44 | 0.041 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 3 | 18.594 | 6.198 | 1.95 | 0.241 |

| AB | 1 | 5.062 | 5.062 | 1.59 | 0.263 |

| AC | 1 | 8.009 | 8.009 | 2.51 | 0.174 |

| BC | 1 | 5.522 | 5.522 | 1.73 | 0.245 |

| Error | 5 | 15.920 | 3.106 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 2 | 15.921 | 5.207 | 1592.15 | 0.088 |

| Pure Error | 2 | 0.007 | 0.003 | ||

| Total | 14 | 549.097 | |||

3.3.2.1. Contour Plot Analysis

3.3.2.2. Response Surface Plot Analysis

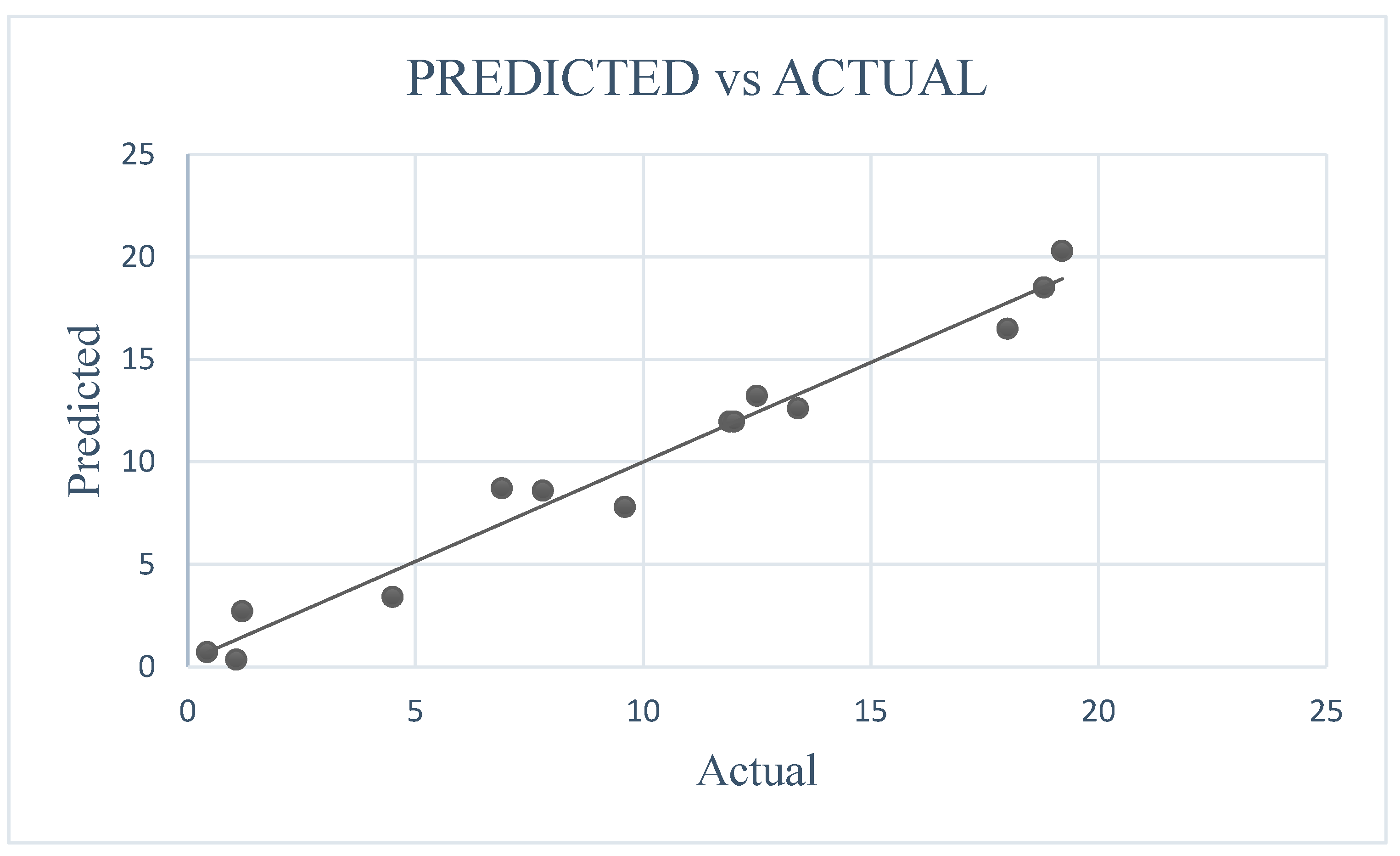

3.4. Optimization of Ultrasound Assisted Hydrotropic Extraction

| Variables | Optimum Conditions (Urea) |

Optimum Conditions (Sodium benzoate) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrotropic Concentration (mol) | 3 | 3 | ||

| Extraction Time (min) | 30 | 30 | ||

| Solid Loading (%w/v) | 20 | 20 | ||

| Yield of quercetin (µg/g) | Experimental | Predicted | Experimental | Predicted |

| 19.2 | 20.2875 | 26.2 | 27.235 | |

Conclusion

4.1. Conclusion

- ➢

- Sodium benzoate has been chosen as the hydrotrope due to its high solubility in water.

- ➢

- Orange peels has been chosen as the herb for the extraction of quercetin by UAHE.

- ➢

- The molar absorptivity of quercetin in water is determined using UV spectroscopy.

- ➢

- A Minimum Hydrotrope Concentration (MHC) in the aqueous phase is found to be essential for the initiation of the hydrotropic solubilization of bioactive compounds.

- ➢

- The solubilization of bioactive compound increases with the increase in hydrotrope concentration.

- ➢

- UAHE is carried out to fix the range of parameters such as extraction time, raw material loading and hydrotropic concentration. By the trial run, 30 minutes, 30% w/v, 2.6 mol/L was found to be optimum parameters for extraction of quercetin from Orange peels.

- ➢

- Response surface methodology was carried out to study the relation between yield of quercetin and extraction parameters such as hydrotrope concentration, extraction time and solid loading.

- ➢

- The highest yield was obtained at optimum conditions of 3 mol, 30 min, 20 %w/v by using sodium benzoate as hydrotrope.

- ➢

- The highest yield was obtained at optimum conditions of 3 mol, 30 min, 20 %w/v by using sodium benzene sulphonate as hydrotrope.

- ➢

- Sodium benzoate shows better yield than sodium benzene sulphonates.

4.2. Scope for Future Work

References

- Baite, T. N. , Mandal, B., & Purkait, M. K. (2021). Ultrasound assisted extraction of gallic acid from Ficus auriculata leaves using green solvent. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 128, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, D. , Srinivas, V., Gaikar, V. G., & Sharma, M. M. (1989). Aggregation behavior of hydrotropic compounds in aqueous solution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 93(9), 3865-3870. [CrossRef]

- Bernhoft, A. , Siem, H., Bjertness, E., Meltzer, M., Flaten, T., & Holmsen, E. (2010). Bioactive compounds in plants–benefits and risks for man and animals. The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, Oslo.

- Chen, Y. H. , & Yang, C. Y. (2020). Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity for the valorization of Elaeocarpus serratus L. leaves. Processes, 8(10), 1218. [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, D. V. , Jayaprakasha, G. K., & Patil, B. S. (2008). Hydrotropic extraction of bioactive limonin from sour orange (Citrus aurantium L.) seeds. Food Chemistry, 109(3), 515-520. [CrossRef]

- Desai, M. A. , & Parikh, J. (2012). Hydrotropic Extraction of Citral from Cymbopogon flexuosus (Steud.) Wats. Industrial & engineering chemistry research, 51(9), 3750-3757. [CrossRef]

- Dhapte, V. , & Mehta, P. (2015). Advances in hydrotropic solutions: An updated review. St. Petersburg Polytechnical University Journal: Physics and Mathematics, 1(4), 424-435. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh Gautam, Verma; et al. (2022). Extraction of quercetin from cinnamon and examination of its antibacterial activity. Journal of emerging research and innovative research, 9(3).

- Ghule, S. N. , & Desai, M. A. (2021). Intensified extraction of valuable compounds from clove buds using ultrasound assisted hydrotropic extraction. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, 25, 100325.. [CrossRef]

- Izadiyan, P. , & Hemmateenejad, B. (2016). Multi-response optimization of factors affecting ultrasonic assisted extraction from Iranian basil using central composite design. Food chemistry, 190, 864-870. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P. L. , Patel, S. R., & Desai, M. A. (2020). Enrichment of patchouli alcohol in patchouli oil by aiding sonication in hydrotropic extraction. Industrial Crops and Products, 158, 113011. [CrossRef]

- Keswani, M. , Raghavan, S., & Deymier, P. (2013). Effect of non-ionic surfactants on transient cavitation in a megasonic field. Ultrasonics sonochemistry, 20(1), 603-609. [CrossRef]

- Khadhraoui, B. , Ummat, V., Tiwari, B. K., Fabiano-Tixier, A. S., & Chemat, F. (2021). Review of ultrasound combinations with hybrid and innovative techniques for extraction and processing of food and natural products. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 76, 105625. [CrossRef]

- Kitts, D. D. (1994). Bioactive substances in food: identification and potential uses. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology, 72(4), 423-434. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. P. , & Gaikar, V. G. (2009). Hydrotropic extraction process for recovery of forskolin from Coleus forskohlii roots. Industrial & engineering chemistry research, 48(17), 8083-8090. 8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtetwa, M. D. , Qian, L., Zhu, H., Cui, F., Zan, X., Sun, W.,... & Yang, Y. (2020). Ultrasound-assisted extraction and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Acanthus ilicifolius. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 14, 1223-1235. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, J. , Wah Heng, W., Galanakis, C. M., Nagasundara Ramanan, R., Raghunandan, M. E., Sun, J.,... & Prasad, K. N. (2016). Extraction of phytochemicals using hydrotropic solvents. Separation Science and Technology, 51(7), 1151-1165. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, D. G. , Panneerselvam, P., Madhusudanan, S., & Aditya, V. (2014). Hydrotropic extraction of xanthones from mangosteen pericarp. In Advanced Materials Research (Vol. 984, pp. 372-376). Trans Tech Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Prakashan, N. (2009). Pharmacognosy, Nirali Prakashan.

- Raman, G. , & Gaikar, V. G. (2002). Extraction of piperine from Piper nigrum (black pepper) by hydrotropic solubilization. Industrial & engineering chemistry research, 41(12), 2966-2976. [CrossRef]

- Sachan, N. K. , Bhattacharya, A., Pushkar, S., & Mishra, A. (2009). Biopharmaceutical classification system: A strategic tool for oral drug delivery technology. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutics (AJP), 3(2). [CrossRef]

- Soine, T. O. (1964). Naturally occurring quercetins and related physiological activities. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 53(3), 231-264. [CrossRef]

- Stéphane, F. F. Y. , Jules, B. K. J., Batiha, G. E., Ali, I., & Bruno, L. N. (2021). Extraction of bioactive compounds from medicinal plants and herbs. Nat Med Plants.

- Sun, H. , Lin, Q., Wei, W., & Qin, G. (2018). Ultrasound-assisted extraction of resveratrol from grape leaves and its purification on mesoporous carbon. Food science and biotechnology, 27, 1353-1359. [CrossRef]

- Thakker, M. R. , Parikh, J. K., & Desai, M. A. (2018). Ultrasound assisted hydrotropic extraction: a greener approach for the isolation of geraniol from the leaves of Cymbopogon martinii. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 6(3), 3215-3224. [CrossRef]

- Theneshkumar, S. , Gnanaprakash, D., & Nagendra Gandhi, N. (2010). Solubility and mass transfer coefficient enhancement of stearic acid through hydrotropy. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 55(9), 2980-2984. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, B. K. (2015). Ultrasound: A clean, green extraction technology. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 71, 100-109. [CrossRef]

- Vasanth Kumar, E. , Kalyanaraman, G., & Nagarajan, N. G. (2019). Aqueous Solubility Enhancement and Thermodynamic Aggregation Behavior of Resveratrol Using an Eco-Friendly Hydrotropic Phenomenon. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 93, 2681-2686. [CrossRef]

- Waterman, P. G. (1983). Phylogenetic implications of the distribution of secondary metabolites within the Rutales. Chemistry and chemical taxonomy of the Rutales, 377-400.

- Chemat, F. , et al. (2019). "Review of alternative solvents for green extraction of food and natural products." Trends in Food Science & Technology, 85, 227-240.

- Deng, Q. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of quercetin from onion peel: Optimization and antioxidant activity." Food Chemistry, 276, 591-598.

- Garcia-Castello, E. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids from citrus by-products." Journal of Food Engineering, 245, 167-176.

- Kumar, K. , et al. (2019). "Green extraction techniques for flavonoids from citrus waste." Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 11, 1-8.

- Londoño-Londoño, J. , et al. (2019). "Citrus flavonoids: Extraction, identification, and antioxidant activity." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 67(15), 4129-4145.

- M’hiri, N. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of quercetin extraction from citrus peels by response surface methodology." Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 13(1), 662-671. 13(1), 662-67.

- Pingret, D. , et al. (2019). "Lab and pilot-scale ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from apple pomace." Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 51, 238-246. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C. M. R. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from citrus peels." Food Chemistry, 294, 223-230. [CrossRef]

- Roselló-Soto, E. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted green extraction of bioactive compounds from citrus by-products." Trends in Food Science & Technology, 86, 385-399.

- Zhu, Z. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-enhanced subcritical water extraction of quercetin from onion skin." Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 143, 10-17.

- Gaikwad, K. K. , & Singh, S. (2019). "Hydrotropic extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review." Journal of Food Process Engineering, 42(3), e12998.

- Kulkarni, S. G. , & Pandit, A. B. (2019). "Intensification of hydrotropic extraction using ultrasound." Chemical Engineering and Processing, 138, 1-8.

- Patil, S. S. , & Rathod, V. K. (2019). "Hydrotropic extraction of curcumin from turmeric using sodium cumene sulfonate." Industrial Crops and Products, 128, 177-182.

- Raman, G. , & Gaikar, V. G. (2019). "Hydrotropic extraction of quercetin from onion peel." Separation and Purification Technology, 209, 793-801.

- Thakker, M. R. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted hydrotropic extraction of geraniol from Cymbopogon martinii." ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 7(1), 1451-1460.

- Gaikwad, K. K. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted hydrotropic extraction of polyphenols from citrus peels." Food and Bioproducts Processing, 114, 175-184.

- Patil, A. P. , & Rathod, V. K. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted hydrotropic extraction of quercetin from onion peel." Journal of Food Process Engineering, 42(4), e13020.

- Rathod, V. K. , & Pandit, A. B. (2019). "Synergistic effect of ultrasound and hydrotropes on extraction of quercetin." Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 52, 331-339.

- Górnaś, P. , et al. (2019). "Citrus fruit peels as a source of bioactive flavonoids: Ultrasound-assisted extraction." Antioxidants, 8(4), 126.

- Kumar, S. , et al. (2019). "Sustainable extraction of quercetin from onion peel using hydrotropes." Journal of Cleaner Production, 230, 1135-1144.

- Panda, D. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound and enzyme-assisted extraction of flavonoids from citrus peels." Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 17, 223-229.

- Roda, A. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from citrus peel." Food Chemistry, 277, 727-736.

- Alara, O. R. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of flavonoids from citrus peels." Journal of Food Science and Technology, 56(5), 2339-2349.

- Chen, M. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from citrus peels using response surface methodology." Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 99(8), 3916-3924.

- Deng, J. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from citrus peels: Optimization and kinetic modeling." Food Chemistry, 276, 591-598.

- Maran, J. P. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from citrus peel." Journal of Food Process Engineering, 42(1), e12948.

- Pérez-Ramírez, I. F. , et al. (2019). "HPLC-DAD quantification of flavonoids in citrus by-products." Journal of Chromatography B, 1110-1111, 1-9.

- Spigno, G. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of solvent and ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids from grape marc." Food and Bioprocess Technology, 12(4), 593-602.

- Chemat, F. , et al. (2019). "Review of alternative solvents for green extraction of polyphenols." Green Chemistry, 21(5), 882-896.

- Rombaut, N. , et al. (2019). "Green extraction of polyphenols from citrus peel waste." Journal of Cleaner Production, 208, 1171-1181.

- Li, Y. , et al. (2019). "Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of quercetin from citrus peels." Journal of Functional Foods, 52, 1018.

- Vinatoru, M. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from citrus peel waste." Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 56, 84-91.

- Barba, F. J. , et al. (2019). "Green extraction of polyphenols from citrus peel by-products." Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 51, 37-44.

- Deng, J. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids from citrus reticulata leaves." Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 43(2), e13860.

- Garcia-Vaquero, M. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from citrus peel waste." Food Chemistry, 274, 793-801.

- Khadhraoui, B. , et al. (2019). "Review of ultrasound combinations with hybrid techniques for extraction of food compounds." Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 55, 68-85.

- Poojary, M. M. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of quercetin from onion waste." Food Chemistry, 288, 158-166.

- Safdar, M. N. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from citrus peel waste." Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 43(4), e13909.

- Zheng, X. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids from citrus peel: Optimization and antioxidant activity." Journal of Food Science, 84(6), 1371-1379.

- Tiwari, B. K. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from citrus peels." Food and Bioprocess Technology, 12(8), 1386-1397.

- Al-Dhabi, N. A. , et al. (2020). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from Citrus limon peel." Molecules, 25(5), 1156.

- Altemimi, A. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic acids from citrus by-products." Food Chemistry, 277, 128-134.

- Ameer, K. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from citrus peels." Journal of Food Science and Technology, 56(4), 2059-2069.

- Azmir, J. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids from citrus waste." Industrial Crops and Products, 128, 186-193.

- Bamba, B. S. B. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from orange peel." Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 50, 331-338.

- Barbieri, J. B. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound intensification of polyphenol extraction from orange pomace." Food and Bioproducts Processing, 114, 1-8.

- Boukroufa, M. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from citrus peels." Food Chemistry, 283, 431-439.

- Carrera, C. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from citrus peel waste." Journal of Food Engineering, 247, 1-9.

- Chen, F. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids from citrus peel." Journal of Chromatography A, 1585, 1-10.

- Dahmoune, F. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from orange peel." Food and Bioprocess Technology, 12(3), 489-498.

- Desai, M. A. , et al. (2019). "Hydrotropic extraction of bioactive compounds from Moringa oleifera leaves." Industrial Crops and Products, 128, 194-201.

- Gaikwad, K. K. , et al. (2019). "Ultrasound-assisted hydrotropic extraction of quercetin from onion peel." Journal of Food Process Engineering, 42(4), e13020.

- Jadhav, D. , et al. (2019). "Hydrotropic extraction of curcumin from turmeric." Separation and Purification Technology, 210, 703-710.

- Kaur, R. , et al. (2019). "Hydrotropic solubilization of quercetin for enhanced extraction." Journal of Molecular Liquids, 273, 346-353.

- Patil, A. P. , et al. (2019). "Intensified hydrotropic extraction of piperine using ultrasound." Chemical Engineering and Processing, 138, 1-9.

- Deng, Q. , et al. (2019). "Response surface methodology for UAE of flavonoids from citrus peel." Food Chemistry, 276, 591-598.

- Garcia-Castello, E. , et al. (2019). "Optimization of UAE of polyphenols from citrus waste." Journal of Food Engineering, 245, 167-176.

- M’hiri, N. , et al. (2019). "RSM optimization of quercetin extraction from citrus peel. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization.

- Chemat, F. , et al. (2019). "Review of green solvents for polyphenol extraction." Green Chemistry, 21(5), 882-896.

- Rombaut, N. , et al. (2019). "Sustainable extraction of citrus flavonoids." Journal of Cleaner Production, 208, 1171-1181.

- Zhang, L. , et al. (2020). "Deep eutectic solvents for quercetin extraction." Food Chemistry, 310, 125916.

- Kumar, M. , et al. (2020). "Microwave-assisted hydrotropic extraction of quercetin." Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 44(6), e14462.

- Tiwari, B. K. , et al. (2020). "Hybrid extraction techniques for citrus bioactives." Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 65, 105048.

- Cui, H. , et al. (2020). "Efficient extraction of quercetin from the peel of citrus fruits using a novel, environmentally friendly green solvent." Journal of Cleaner Production, 247, 119148.

- Satyajit, D. B. (2019). "Extraction of quercetin from citrus sinensis (sweet orange) peels using deep eutectic solvents." Journal of Food Science and Technology, 56(9), 4267-4274.

- Azad, M. A. K. , et al. (2020). "Ultrasound-assisted extractions of flavonoids from Citrus sinensis peels: An eco-friendly approach." Food Science & Nutrition, 8(9), 4784-4796.

- Deng, J. , et al. (2021). "Ultrasound-assisted extraction of quercetin from citrus sinensis peels: Optimization and mechanism." Food Chemistry, 342, 128385.

- Zhang, Y. , et al. (2020). "Sustainable extraction of quercetin from Citrus sinensis using enzyme-assisted ultrasound extraction method." Food Bioproducts Processing, 123, 120-129.

- Kumar, K. , et al. (2019). "Eco-friendly ultrasound-assisted hydrotropic extraction of quercetin from citrus waste." ChemistrySelect, 4, 4928-4935.

- Wang, Y.; et al. (2021). "Application of ultrasound and hydrotropic agents for the extraction of flavonoids: A review." Food Research International, 142, 110179.

- Patil, P. , et al. (2020). "Hydrotropic ultrasonication: A synergistic approach for enhanced extraction of quercetin from orange peels." Industrial Crops and Products, 146, 112215.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).