The success of quantum mechanics is nothing short of extraordinary since its inception a century ago. It has not only revolutionized science and technology but has also challenged our deepest philosophical assumptions about reality. Yet, it remains one of the most counterintuitive theories ever formulated. Phenomena such as nonlocality, entanglement, and the instantaneous collapse of the wavefunction upon measurement have given rise to a diverse array of interpretations among scientists and philosophers. In 1935, Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen (EPR) proposed a thought experiment, now known as the EPR paradox [

1,

2], involving a pair of entangled particles separated by a space-like distance. According to quantum mechanics, measuring one particle instantaneously alters the quantum state of the other particle, even if they are light-years apart. This led the EPR authors to conclude that the quantum description of physical reality must be incomplete. Einstein argued [

3,

4,

5] that the expectations of measurement value of quantum-mechanical observables should serve as an element of reality and that a measurement on one particle should not instantaneously affect the quantum state of the other. It may need some new theory with extra parameters (hidden variables) in order to make it complete. His argument relied on the principles of locality and realism [

6].

The principles of locality and realism assume that objects are only directly influenced by their immediate surroundings and that their physical properties exist independently of measurement. In 1964, John Bell formulated a theorem [

7] demonstrating that a hidden variable theory consistent with local realism must satisfy a specific mathematical inequality—now known as Bell's inequality [

8,

9]. Using a system similar to the EPR paradox, he showed that quantum mechanics predicts violations of this inequality. Since then, numerous experiments [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] have been conducted, progressively closing loopholes in earlier studies. All experimental results have confirmed violations of Bell's inequality, consisting with the predictions from quantum mechanics and strongly disfavoring local hidden variable theories.

Since the advent of quantum mechanics, physicists have debated the nature of reality [

16]. Einstein and his colleagues argued that quantum observables—such as a particle’s position and momentum—should correspond to "elements of reality," possessing definite values independent of measurement. However, quantum mechanics suggests otherwise: observables lack predetermined values before measurement, a principle encapsulated in the Bell-Kochen-Specker theorem [

17,

18,

19,

20] (also known as the Kochen-Specker theorem). This theorem formalizes quantum contextuality, showing that measurement outcomes depend on the choice of other commutable observables within the same experiment. As Peres noted in ref. [

21]: “……if three operators A, B, and C satisfy [A, B] = [A, C] = 0 and [B, C] ≠ 0, the result of a measurement of A cannot be independent of whether A is measured alone or together with B or C.” This directly challenges Einstein’s concept of local realism.

The issue is further clarified by the Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] (GHZ) theorem, which demonstrates that merely assuming definite values for three commutable spin observables leads to a direct contradiction with quantum predictions [

27]. Likewise, Bell’s inequality, derived under the assumptions of hidden variables, is incompatible with quantum mechanics, which inherently lacks such variables. As a result, quantum mechanics violates Bell's inequality. Consequently, Bell’s theorem—based on the assumption of predefined values for observables within a hidden-variable framework—does not strictly apply to quantum mechanics [

28,

29,

30,

31]. This leaves open the possibility that quantum theory may remain fundamentally local [

32,

33], provided an alternative formulation of "elements of reality" extends beyond expectation values of observables.

The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, often considered the orthodox view, posits that wavefunction collapse is not a physical process but rather a reflection of the observer’s changing knowledge. In this framework, the wavefunction serves as a mathematical representation of information, updating instantaneously upon measurement [

34]. Whether the wavefunction is fundamentally epistemic or ontic—and whether it constitutes an element of physical reality—remains an open question. In 2012, Pusey, Barrett, and Rudolph (PBR) formulated a theorem [

35] challenging purely epistemic interpretations, providing strong evidence in favor of an ontic view of the quantum state.

Although Bell's theorem does not imply that quantum mechanics must be nonlocal, most physicists accept nonlocality primarily due to the instantaneous collapse of the wavefunction during measurement. The ambiguous nature of reality, the lack of a physical mechanism for wavefunction collapse, and the nonlocal characteristics of quantum mechanics remain central controversies in the field. These issues are ultimately tied to the measurement problem and continue to give rise to paradoxes, such as Schrödinger’s cat [

36], Wigner Friend [

37,

38,

39].

Since the 1970s, quantum decoherence [

40,

41,

42] has been proposed as a way to address the measurement problem. It provides a dynamical mechanism explaining the apparent collapse of the wavefunction due to system-environment interactions (see the recently review papers [

43,

44,

45]). Spin-environment models, introduced by Zurek [

42,

46] focus on the decoherence of a single spin (qubit) interacting with a spin bath. In this paper, I investigate two entangled spin-1/2 particles in the EPR setting using a simple yet exactly solvable quantum decoherence model. The local components of the system wavefunction for the two spins and the environment spin bath are derived from the Schrödinger equation when one of the entangled particles is measured by the environment. From this dynamic solution, I analyze wavefunction collapse, entanglement, decoherence, and their implications for locality.

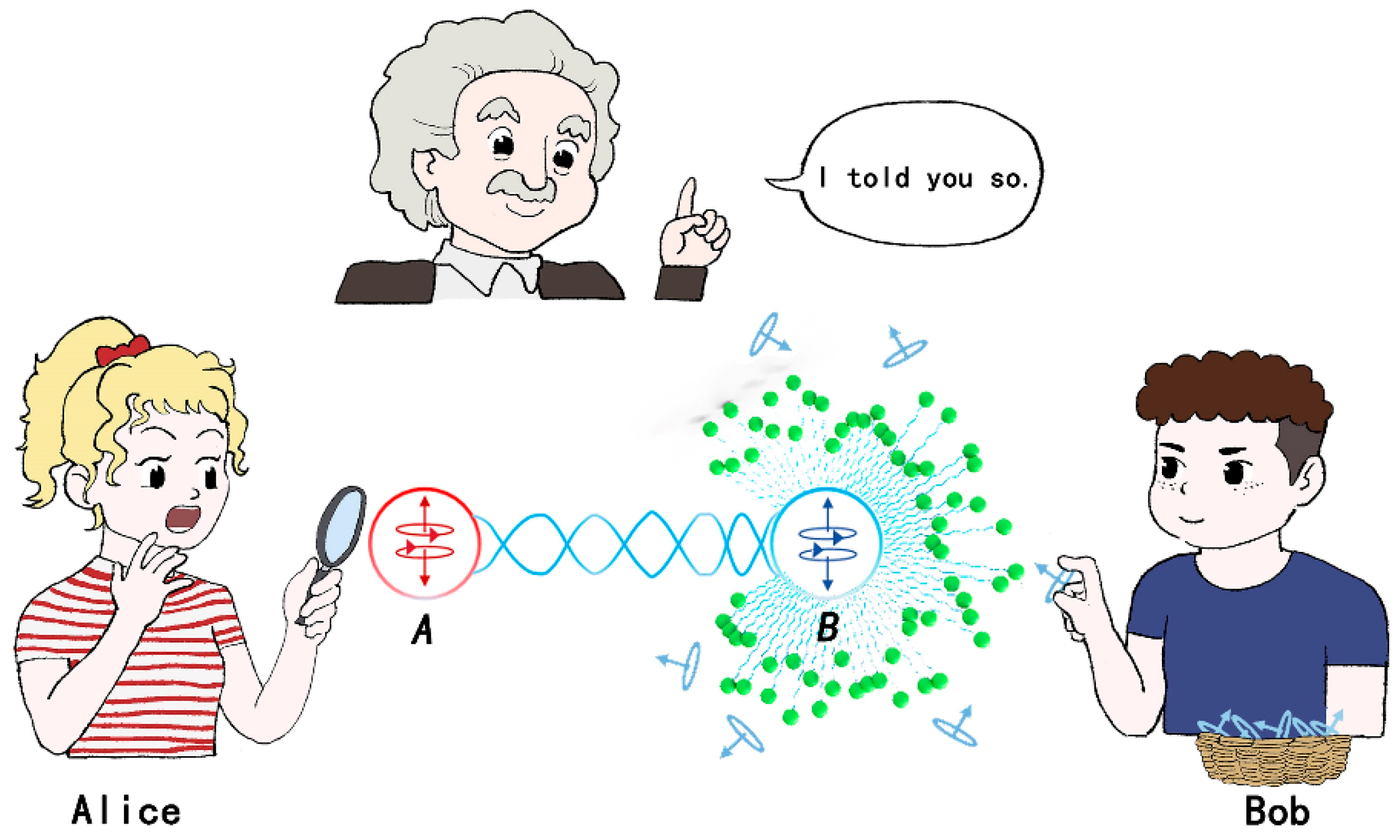

The system under consideration consists of two entangled spin-1/2 particles (

A and

B) that are space-like separated. They are initially prepared in a maximally entangled singlet state and propagate freely in opposite directions toward Alice and Bob, who can choose to perform quantum spin measurements (

Figure 1).

Rather than employing a non-uniform magnetic field and a screen, Bob subjects particle B to an interaction with an environmental bath comprising

spins. This interaction is governed by a linear Hamiltonian [42,46], which effectively emulates a z-direction spin measurement on particle B, commencing at t = 0.

(1)

Where

represent the Pauli matrices of particle B and kth spin in the bath, respectively, while

denotes the interaction strength between particle B and bath spin k. Here we study a general case in which the bath spins are initially entangled. The initial wavefunction of the system plus environment can be written as:

(2)

Where

,

are the state of particle A and B with their spins pointing in z and anti-z directions, respectively,

are complex numbers for bath computational base

,

. They can be expressed in terms of individual spin states analogous to a binary encoding:

……

(

3

)

……

The Schrödinger equation with the Hamiltonian for the system and environment can be solved exactly for arbitrary N and time t:

(4)

Where two environment states at t are

Where

and

if the kth spin in the bath is aligned with z and

if it is anti-aligned. The nth computational basis state corresponds uniquely to its associated spin configuration

, as determined by its binary representation given in Eq. (3).

The solution given in equation (4) can be verified by substituting it to the Schrödinger equation with the Hamiltonian in equation (1). Notably, the expressions for the environment states remain identical to those in

ref.

[46]

, despite the fact that our system comprises two entangled particles—one of which interacts with the environment—whereas the system in ref.

[46]

involved only a single particle coupled to the same environment. This similarity arises because particle A, although entangled with particle B, has no direct physical interaction with either the bath spins or particle B. As a result, all dynamical evolution occurs exclusively within particle B and the environment.

After an interaction time t, the environment spins become entangled with both particles A and B, forming a three-way entanglement, due to the fact that wavefunctions for system spins and the environment are no longer factorizable in solution (4). The dynamical solution deviates from the quantum measurement axiom: upon interaction with the environment, the wavefunction does not collapse instantaneously. Instead, it undergoes a continuous evolution governed by the Schrödinger equation. The local wavefunction of particle A, which does not interact with the environment, remains unchanged throughout the decoherence process. In contrast, the wavefunction of particle B and the environment evolves continuously from t=0 onward.

To describe the state of the system for particles A and B alone, we need to “ignore” or “average over” the uncontrollable states of the environment. This is achieved by performing a partial trace over the environmental degrees of freedom (DOF), yielding the reduced density matrix for the system:

Where is decoherence factor:

The two expressions for the decoherence factor presented above correspond to the cases where the bath is initially entangled and not entangled, respectively. In the latter case, the initial bath wavefunction is characterized by complex coefficients for the kth spin in the bath.

This decoherence factor

depends on is the interacting strength

between particle

B and

kth spin in the bath, as well as the initial bath states coefficients

or

. At

,

, indicating that the particle

A and

B remain in their original strongly entangled state. However, it has been shown that

rapidly approaches zero [

46] following the approximation for

, where

a and

b are real constants. Furthermore, for large

t and

N, under a general random distribution of

, time average of

remains close to zero [

42] with

.

With approaches 0, the reduced density matrix reveals that environment decoherence of particle B destroys any correlation between two pointer states of the particle A and B, resulting in a density matrix that represents a mixed state:

(5)

In the terminology of Zurek, equation (5) indicates that the environment dynamically selects two states

and

as pointer states—a process known as environment-induced superselection, or einselection [

43] — and effectively suppresses any superposition between them. The system exhibits a 50% probability of being in either of the pointer states, precisely as predicted by the Born’s rule and quantum measurement axiom.

This result is striking: quantum decoherence continuously transforms the two entangled particles into a mixed state, even though the wavefunction component of particle A remains unchanged. Our findings show that for a pair of entangled particles in space-like separation, measuring one has no effect on the wavefunction component of the other. Consequently, there is no instantaneous collapse of the global wavefunction and no superluminal communication. All interactions in the simulation are strictly local, with no indication of "spooky action at a distance".

It is widely assumed that measuring one of a pair of entangled particles instantaneously reveals the quantum state of its distant counterpart, irrespective of their spatial separation and without any physical interaction. However, our simulations challenge this view, demonstrating that such an understanding is flawed.

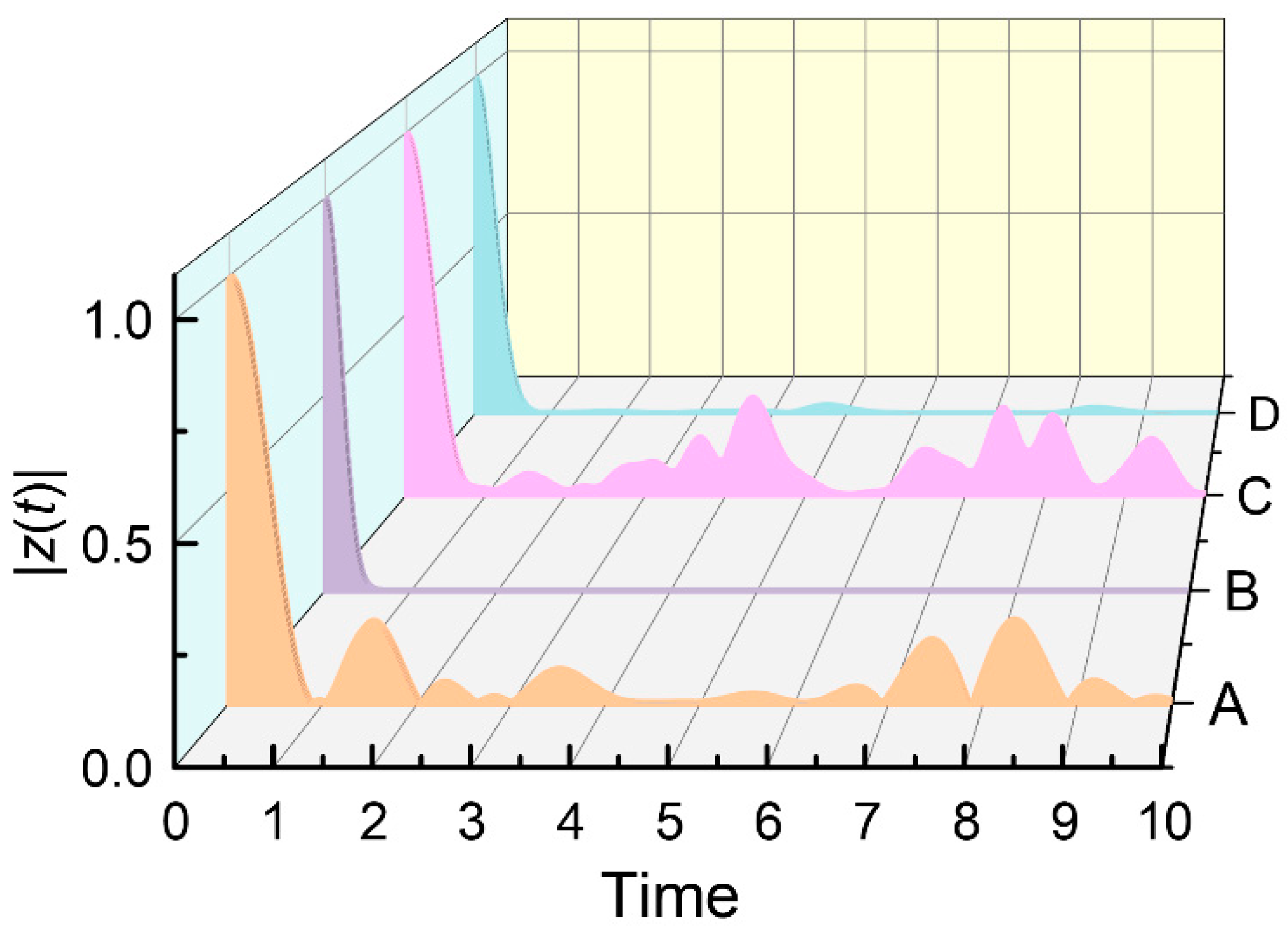

The decoherence factor

can be computed numerically using Monte Carlo simulations. To begin, we consider only the randomness arising from the interaction strength

, which are assuming to be uniformly distributed [

46] in [-2, 2]. In this analysis, we disregard the randomness associated the initial distribution of environment spins by assuming that each spin equal probability in the spin-up and spin-down state. The results show that the decoherence factor rapidly approaches zero and remains near to zero over the time, ever for small number of the environment spins, consistent with [

46] (Curve A and B in

Figure 2). The timescale of decoherence is typically very short. For instance, an electron spin in a GaAs quantum dot rapidly loses coherence due to hyperfine interactions with the nuclear spins of Ga and As. This interaction, with a strength of approximately 50 μeV[

47], induces decoherence on a nanosecond timescale.

The impact of randomness from environment spins are considered in

Figure 2 curve C and D. Instead of fixing the initial state of the spins in the bath, we select the initial states bath spins uniformed distributed on a Bloch sphere. Simulations show that incorporating randomness in initial states of the bath is slightly less effective in suppressing the amplitude of the decoherence factor comparing with A and B.

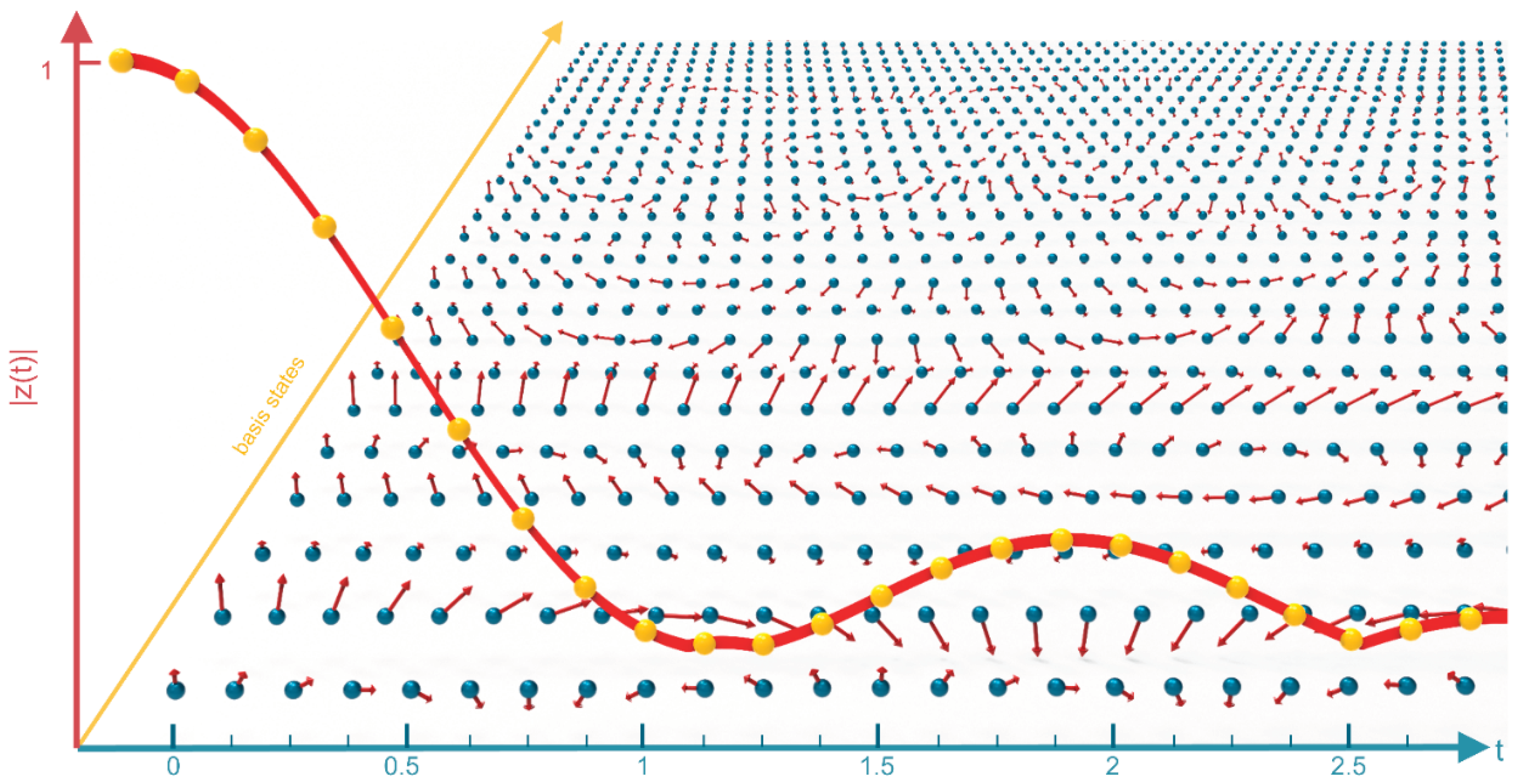

The individual contributions from all

basis states are illustrated in

Figure 3, which corresponds to curve C in

Figure 2. These contributions account for both the inherent stochasticity in the initial spin states of the environment and the variability in their interaction strengths. The results reflect the combined effects of random sampling over environmental spin states and the heterogeneous coupling parameters governing their interactions with the system.

More detailed models have shown that decoherence occurs almost instantaneously. For macroscopic object with mass of 1g and size of 1cm, the decoherence time and thermal relaxation time ratio is about 10

-40, resulting immediate decoherence. In mesoscopic systems, such as dust particles with mass of 10

-15kg and radius of 0.1

μm, even exposure to the 3K cosmic microwave background radiation induces almost immediate decoherence in about 10

-7s. Microscopic systems, including large molecules, also experience rapid decoherence due to interactions with thermal radiation—on timescales far shorter than can be practically observed [

48,

49,

50].

When considering that all measurement apparatuses are macroscopic systems subject to environmental decoherence, many of quantum mechanics’ paradoxes become less problematic. In Schrödinger’s cat experiment, decoherence ensures that the cat’s state resolves to either alive or dead long before an observer opens the box. Similarly, in Wigner’s friend thought experiment, the friend does not remain in a superposition with the electron and measuring device—decoherence rapidly drives large systems into classical states, regardless of whether Wigner later inquires about the outcome.

Although decoherence does not collapse the global wavefunction of the system and environment, as shown in equation (4), nor fully resolves the measurement problem, the presence of numerous uncontrollable DOF in the environment gives rise to an apparent collapse of the system’s wavefunction. This effect emerges because the reduced density matrix, obtained by tracing over these DOF, loses coherence. As a result, quantum decoherence in measurement provides a natural explanation for observed outcomes, eliminating the need for an unphysical, instantaneous wavefunction collapse.

In conclusion, based on the foundational assumptions underlying the derivation of Bell’s inequality, I argue that Bell’s theorem and the subsequent experimental violations of the inequality rule out only local realistic hidden variable theories. These results, however, do not directly apply to quantum mechanics as formulated. Notably, the assumption of predefined values for observables stands in direct conflict with the principle of quantum contextuality, as established by the Bell–Kochen–Specker theorem and the Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) theorem.

Recent theoretical developments—most notably the Pusey–Barrett–Rudolph (PBR) theorem—further support the interpretation of the wavefunction as an ontic entity, representing a genuine element of physical reality, rather than a merely epistemic construct encoding knowledge or information.

To further substantiate this perspective, I presented a simple yet exactly solvable quantum decoherence model applied to an EPR-like system, where system–environment interactions are treated as intrinsic components of the measurement process. The analysis and Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that measurement on one entangled particle neither instantaneously collapses the total wavefunction nor determines the state of the distant particle. Instead, the local wavefunctions of the measured particle and its surrounding environment evolve dynamically though local interactions, while the remote particle’s wavefunction remains unaffected. Decoherence, induced by local environmental interactions, selects stable pointer states and rapidly suppresses quantum correlations, creating the appearance of wavefunction collapse without invoking nonlocality.

These findings suggest that quantum mechanics can, in principle, be reconciled with local realism if the wavefunction is accepted as an ontic element of reality. This interpretation provides a coherent and physically grounded framework for developing a local and realistic formulation of quantum theory, resonating with the foundational vision articulated by Einstein in the original EPR argument. Moreover, these results not only strengthen the conceptual foundations of quantum mechanics but also carry important implications for quantum information processing and quantum computing, where a clear understanding of measurement, decoherence, and the nature of quantum states is essential.

Author Contributions

The author solely conceived the study, conducted the research, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Beijing Institute of Nanoenergy and Nanosystems, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The author sincerely thanks Professor Wojciech H. Zurek (Los Alamos National Laboratory), Professor Bohua Sun, Professor Morten Willatzen, Professor Kailiang Ren (Beijing Institute of Nanoenergy and Nanosystems, Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Dr. Shudong Zhou (Zscaler, Inc., San Jose, California USA) for their valuable discussions and insightful comments. The author also extends his gratitude to Mr. Yangshi Shao (Beijing Institute of Nanoenergy and Nanosystems, Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Mr. Yi Da from Changsha for their assistance in preparing the figures for this article.

Competing Interests: The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional Information: The MATLAB scripts used to generate Figures 2 and 3 are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Phys. Rev. B 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Physics and reality. J. Frankl. Inst. 1936, 221, 349–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, T. An Einstein manuscript on the EPR paradox for spin observables. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part B: Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 2007, 38, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D. Einstein on locality and separability. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part A 1985, 16, 171–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, N.; Spekkens, R.W. Einstein, Incompleteness, and the Epistemic View of Quantum States. Found. Phys. 2010, 40, 125–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, G. Quantum Objects; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J. S. On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox. Physics 1, 195–200 (1964); reprinted Bell, J. S. Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1987).

- Clauser, J.F.; Horne, M.A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R.A. Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1969, 23, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, I. How the Bell tests changed quantum physics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 674–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, S.J.; Clauser, J.F. Experimental Test of Local Hidden-Variable Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1972, 28, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Grangier, P.; Roger, G. Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-BohmGedankenexperiment: A New Violation of Bell's Inequalities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihs, G.; Jennewein, T.; Simon, C.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. Violation of Bell's Inequality under Strict Einstein Locality Conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 5039–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A. Bell's inequality test: more ideal than ever. Nature 1999, 398, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M.A.; Kielpinski, D.; Meyer, V.; Sackett, C.A.; Itano, W.M.; Monroe, C.; Wineland, D.J. Experimental violation of a Bell's inequality with efficient detection. Nature 2001, 409, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensen, B.; Bernien, H.; Dréau, A.E.; Reiserer, A.; Kalb, N.; Blok, M.S.; Ruitenberg, J.; Vermeulen, R.F.L.; Schouten, R.N.; Abellán, C.; et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 2015, 526, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W. Experimentally Ruling Out Joint Reality Based on Locality with Device-Independent Steering. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. On the Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1966, 38, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochen, S.; Specker, E. The Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 1967, 17, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhead, M. Incompleteness, Nonlocality, and Realism: A Prolegomenon to the Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics (1989, Oxford: Clarendon Press), ISBN: 978-0198249375.

- Mermin, N.D. Hidden variables and the two theorems of John Bell. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1993, 65, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A. Two simple proofs of the Kochen-Specker theorem. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 1991, 24, L175–L178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberger, Daniel M.; Horne, Michael A.; Zeilinger, Anton (1989). Going beyond Bell's Theorem. In Kafatos, M. (ed.). Bell's Theorem, Quantum Theory and Conceptions of the Universe. Dordrecht: Kluwer. p. 69.

- Greenberger, D. M. , Horn, M. A., Shimony, A. and Zeilinger, A., Bell’s theorem without inequalities, Am. J. Phys. 58, 1131-1143(1990).

- Mermin, N.D. Quantum mysteries revisited. Am. J. Phys. 1990, 58, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Mermin, N. Simple unified form for the major no-hidden-variables theorems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 65, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian-Wei Pan; D. Bouwmeester; M. Daniell; H. Weinfurter; A. Zeilinger, Experimental test of quantum nonlocality in three-photon GHZ entanglement, Nature, 403 (6769): 515-519(2000).

- M. Scully and M. Zubairy, Quantum Optics, (Cambridge University Press, 1997), ISBN-13: 978-0524235959, Chapter 18, p529.

- Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Is the Contextuality Loophole Fatal for the Derivation of Bell Inequalities? Found. Phys. 2010, 41, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowski, M.; Brukner, Č. Quantum non-locality—it ainʼt necessarily so. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2014, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.B. Nonlocality claims are inconsistent with Hilbert-space quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 022117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, A.; Cetto, A.M.; Hess, K.; Valdés-Hernández, A. Towards a Local Realist View of the Quantum Phenomenon; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrennikov, A. Get Rid of Nonlocality from Quantum Physics. Entropy 2019, 21, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hance, J.R.; Hossenfelder, S. Bell’s theorem allows local theories of quantum mechanics. Nat. Phys. 2022, 18, 1382–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermin, N.D. Physics: QBism puts the scientist back into science. Nature 2014, 507, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusey, M.F.; Barrett, J.; Rudolph, T. On the reality of the quantum state. Nat. Phys. 2012, 8, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimmer, John D., The Present Situation in Quantum Mechanics: A Translation of Schrödinger's "Cat Paradox" Paper, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 124 (5): 323–338(1980).

- Wigner, E.P. Remarks on the Mind-Body Question, In Mehra, Jagdish (ed.). Philosophical Reflections and Syntheses. The Collected Works of Eugene Paul Wigner. Vol. B/6. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 247–260(1995). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78374-6_20. ISBN 978-3-540-63372-3.

- Frauchiger, D.; Renner, R. Quantum theory cannot consistently describe the use of itself. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, K.-W.; Utreras-Alarcón, A.; Ghafari, F.; Liang, Y.-C.; Tischler, N.; Cavalcanti, E.G.; Pryde, G.J.; Wiseman, H.M. A strong no-go theorem on the Wigner’s friend paradox. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeh, H.D. On the interpretation of measurement in quantum theory. Found. Phys. 1970, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Pointer basis of quantum apparatus: Into what mixture does the wave packet collapse? Phys. Rev. D 1981, 24, 1516–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Environment-induced superselection rules. Phys. Rev. D 1982, 26, 1862–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximilian Schlosshauer, Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics, Reviews of Modern Physics. 76 (4): 1267–1305(2005).

- Schlosshauer, M. Quantum decoherence. Phys. Rep. 2019, 831, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchietti, F.M.; Paz, J.P.; Zurek, W.H. Decoherence from spin environments. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 052113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekhovich, E.A.; Ulhaq, A.; Zallo, E.; Ding, F.; Schmidt, O.G.; Skolnick, M.S. Measurement of the spin temperature of optically cooled nuclei and GaAs hyperfine constants in GaAs/AlGaAs quantum dots. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, E.; Zeh, H.D. The emergence of classical properties through interaction with the environment. Eur. Phys. J. B 1985, 59, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G.; Zurek, W.H. Reduction of a wave packet in quantum Brownian motion. Phys. Rev. D 1989, 40, 1071–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence and the Transition from Quantum to Classical. Phys. Today 1991, 44, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).