Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

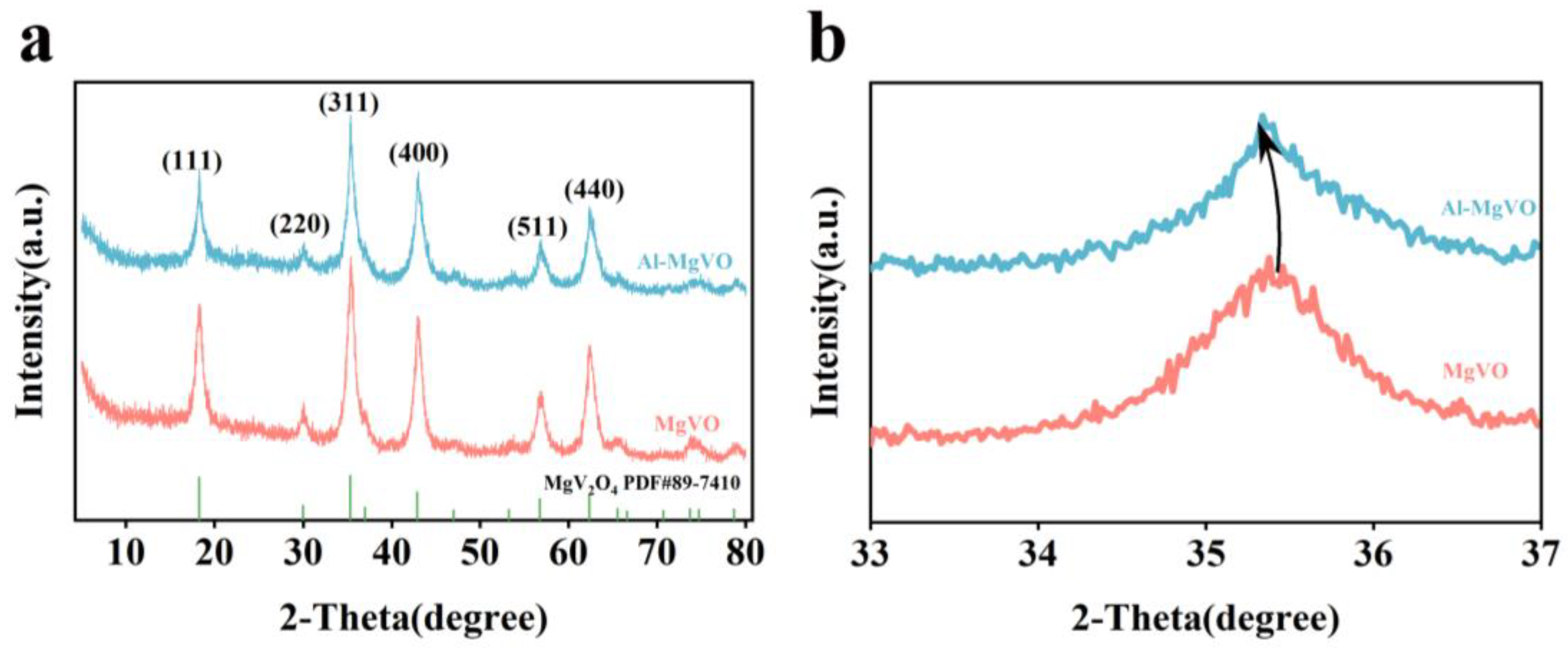

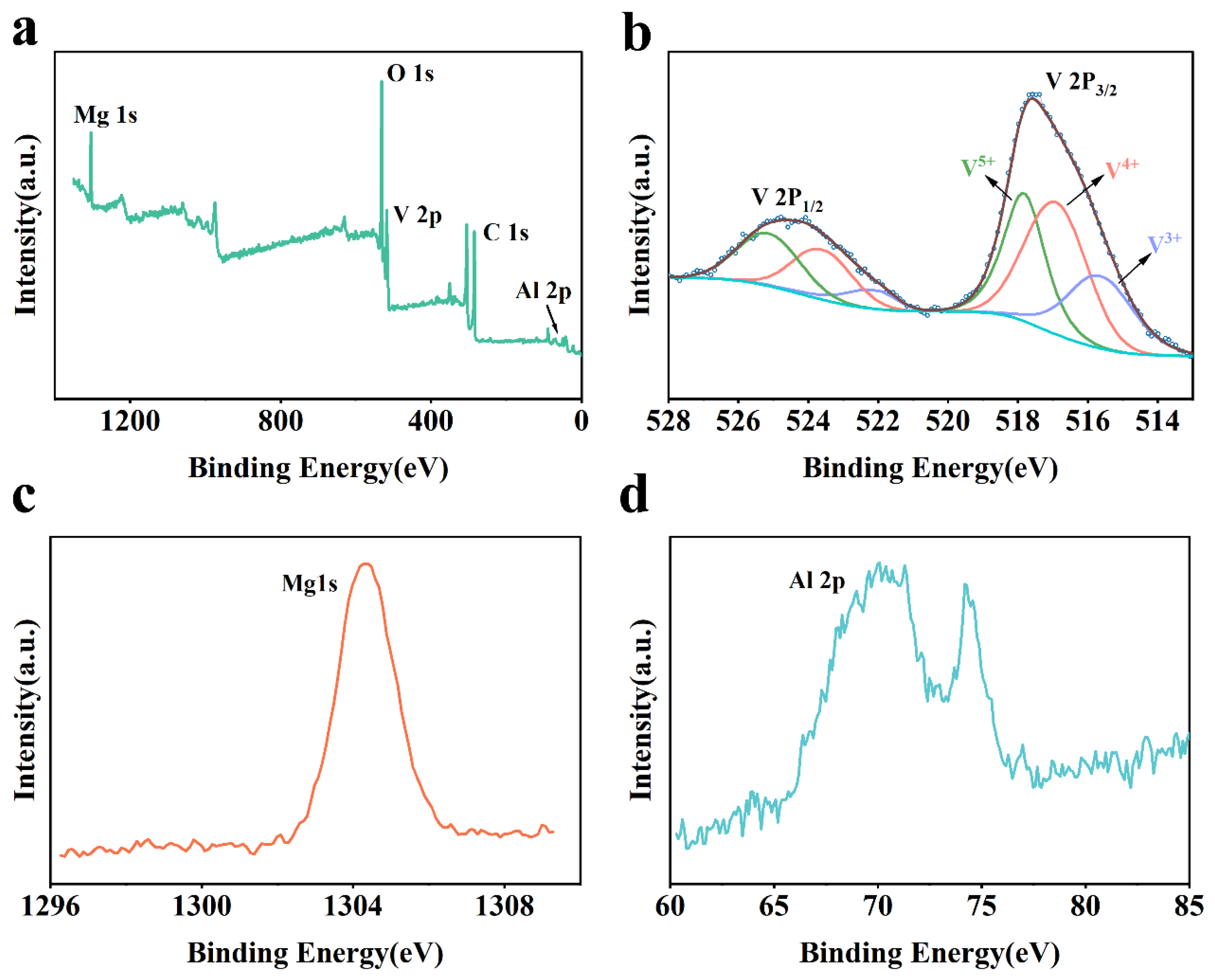

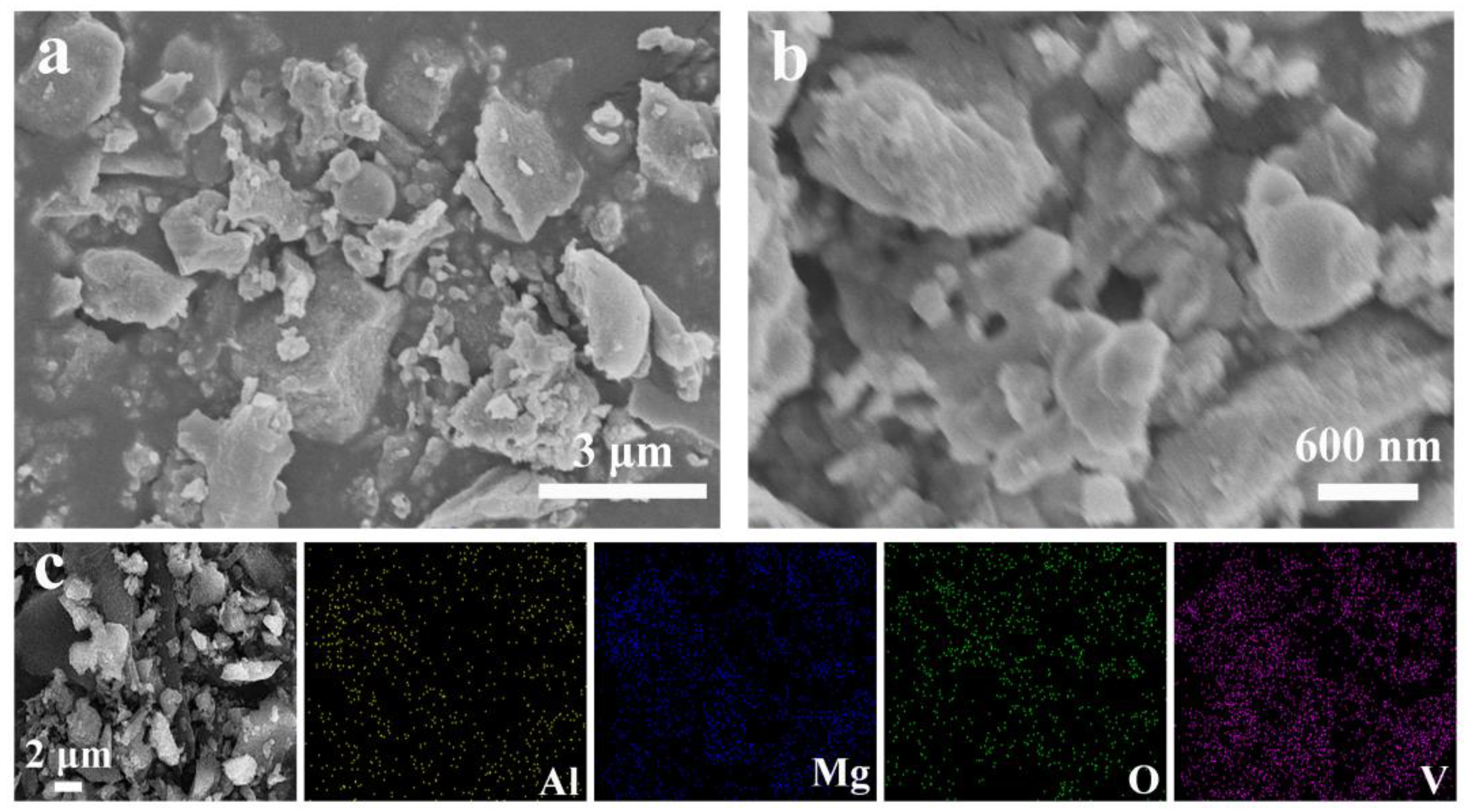

2.1. Morphological Characterization

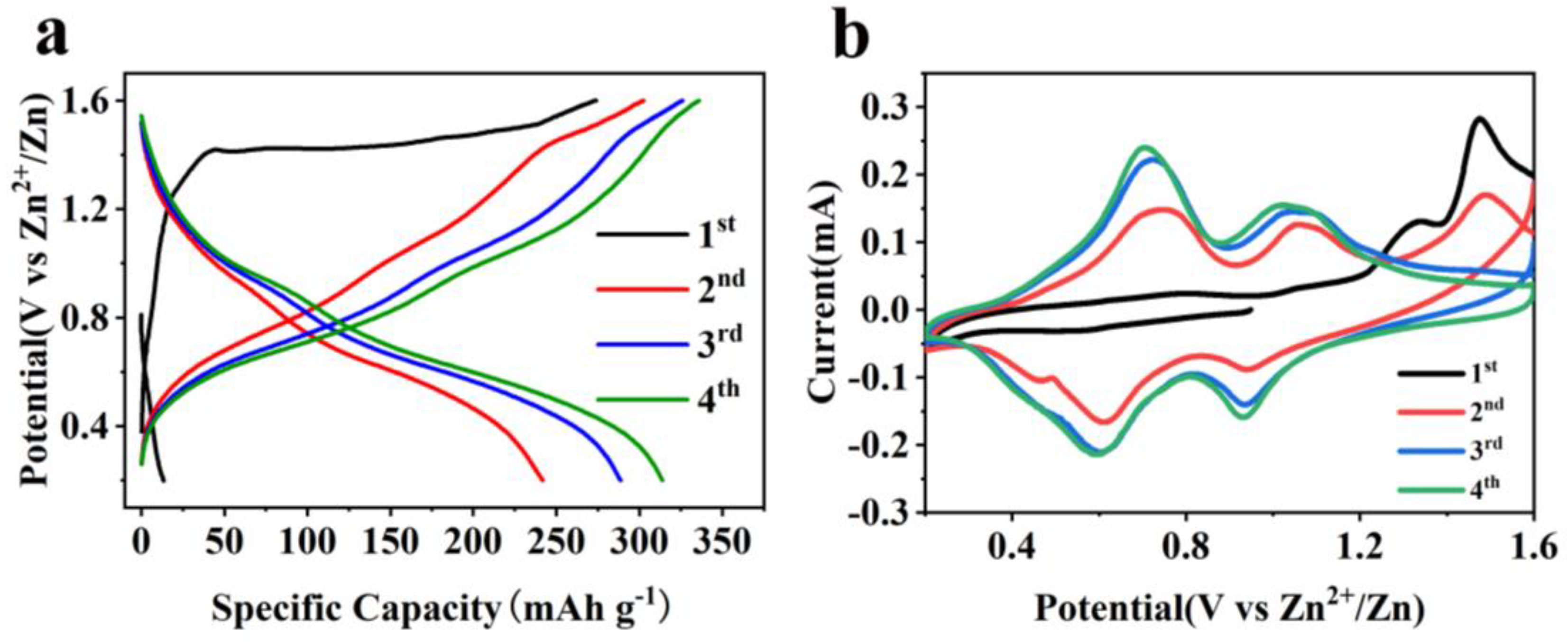

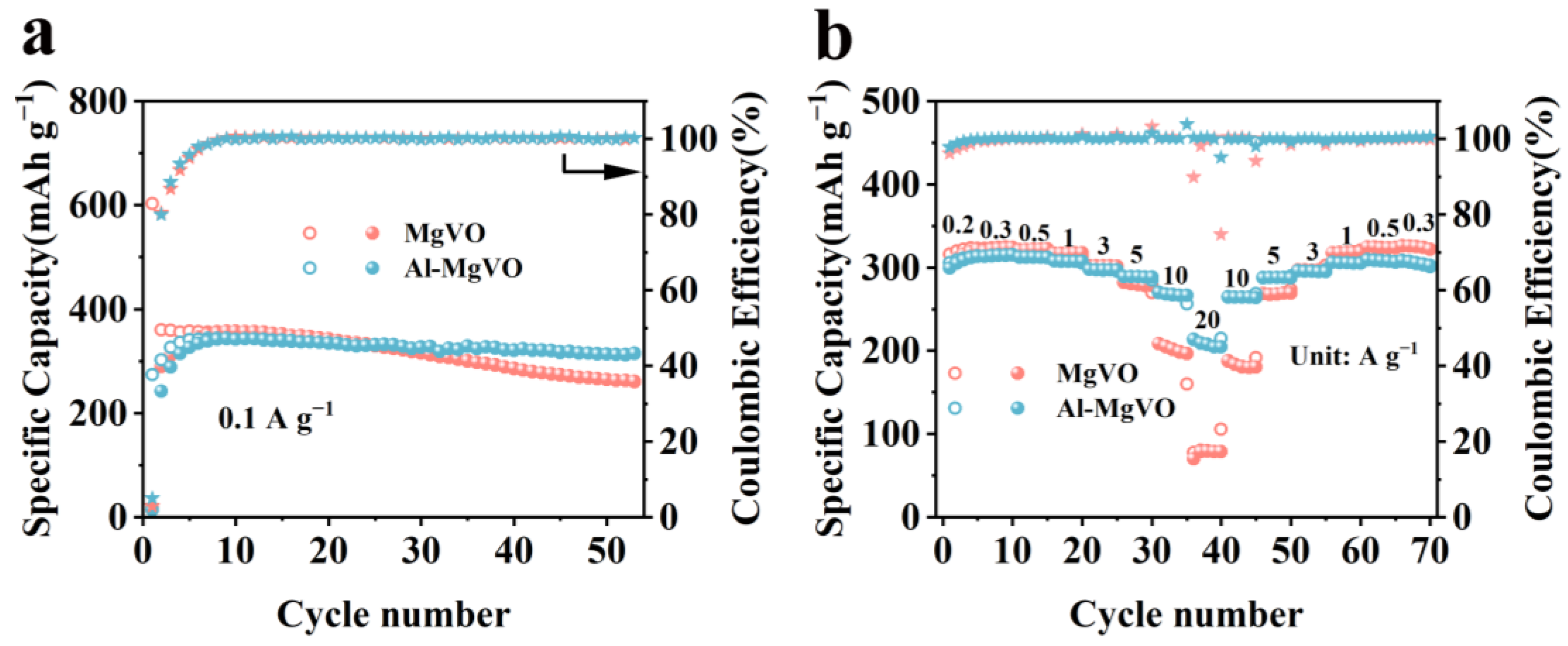

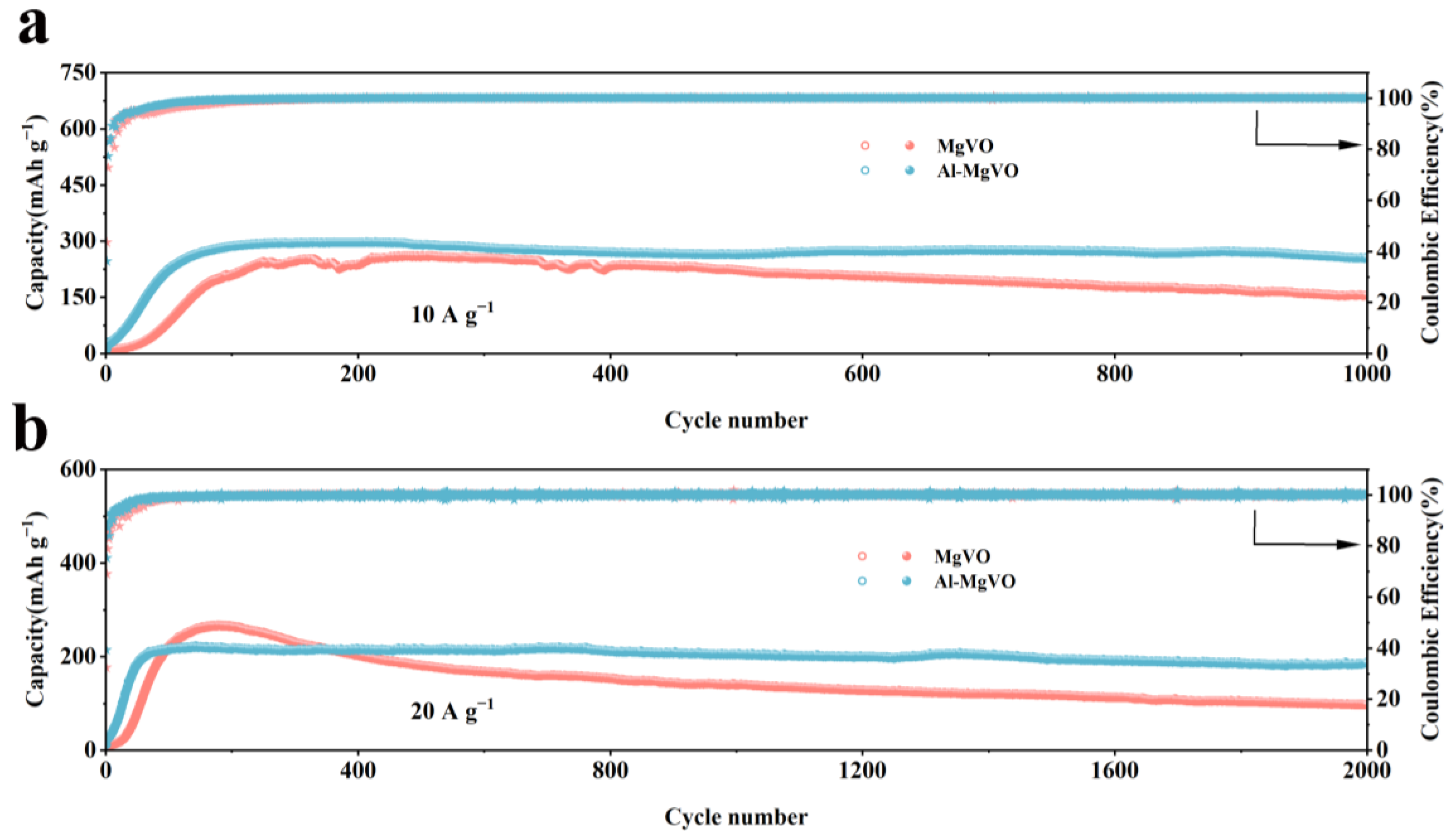

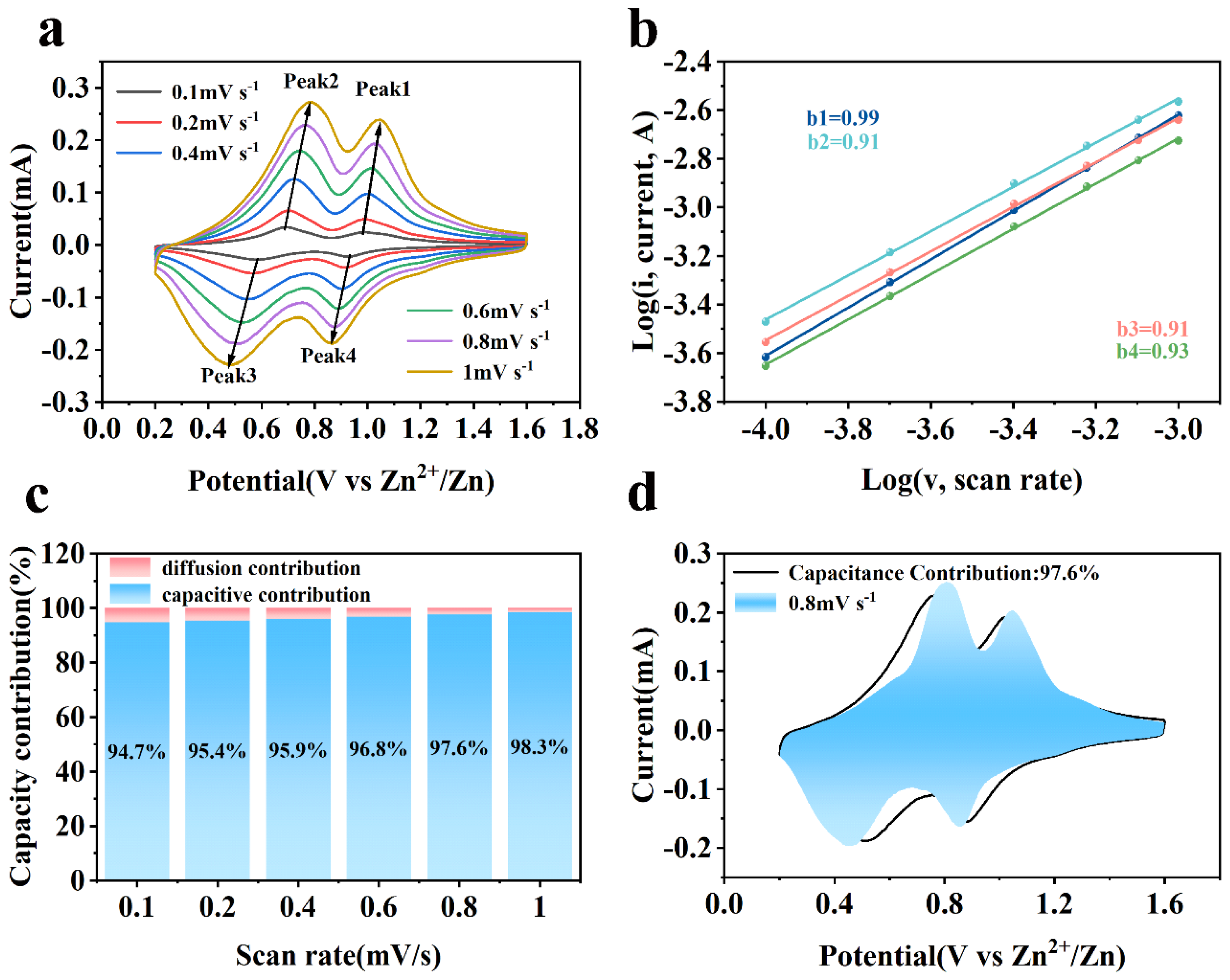

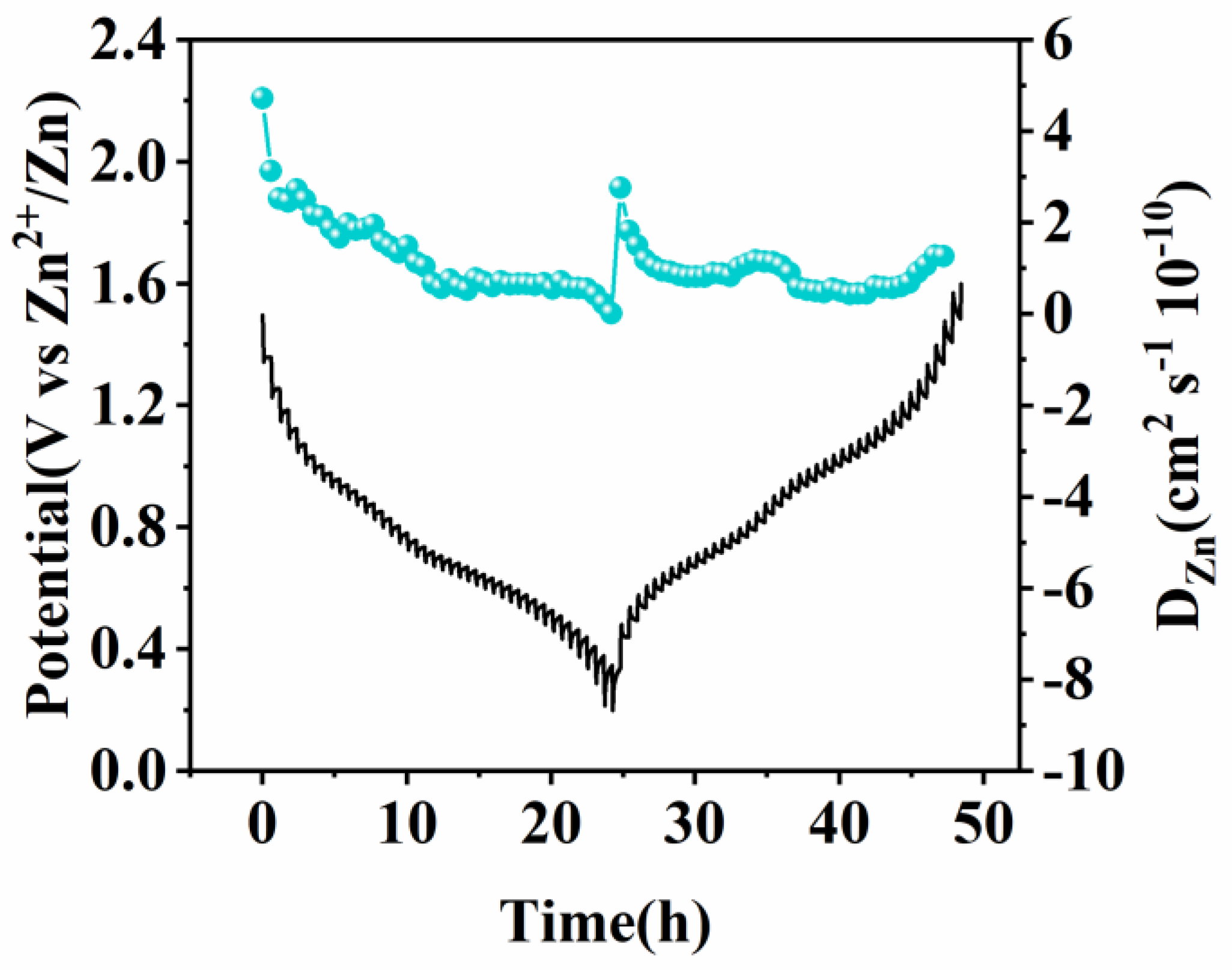

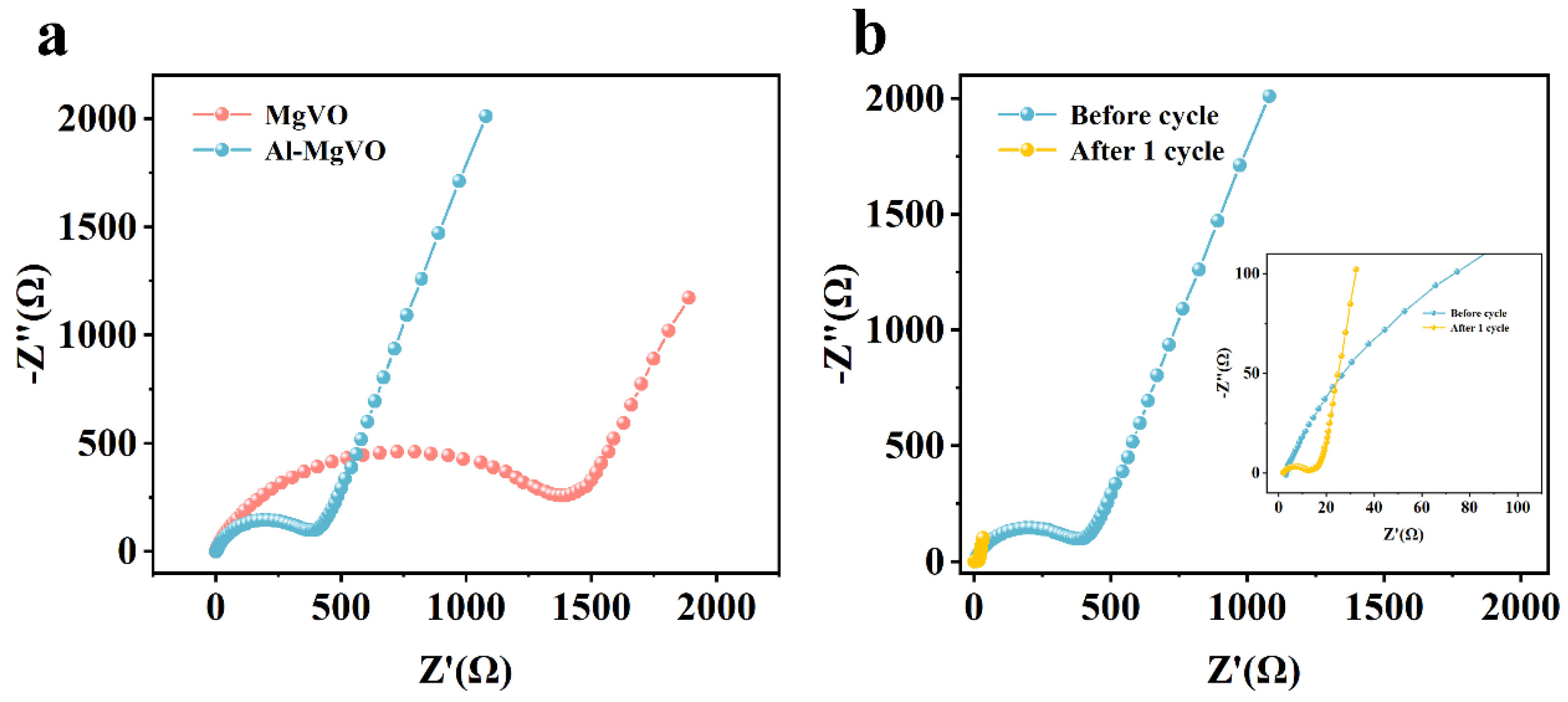

2.2. Electrochemical Properties Characterization

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of Material

3.2. Materials Characterization

3.3. Electrode Fabrication

3.4. Electrochemical Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Algarni, S.; Tirth, V.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshehery, S.; Kshirsagar, P. Contribution of renewable energy sources to the environmental impacts and economic benefits for sustainable development. Sustain. Energy. Techn. 2023, 56, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Niu, Z. Design strategies for vanadium-based aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2019, 131, 16508–16517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.P.; Lv, D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Shi, F.N. Review on defects and modification methods of LiFePO4 cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 1232–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, L.E.; Kundu, D.; Nazar, L.F. Scientific challenges for the implementation of Zn-ion batteries. Joule 2020, 4, 771–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Jin, H.; Davey, K.; Liang, G.; Liu, S.; Mao, J.; Guo, Z. Developing cathode materials for aqueous zinc ion batteries: challenges and practical prospects. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2301291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.P.; Lv, D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Shi, F.N. Review on defects and modification methods of LiFePO4 cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 1232–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, M. Advances in intelligent regeneration of cathode materials for sustainable lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cai, X.; Cai, S.; Shao, Y.; Hu, C.; Lu, S.; Ding, S. High-energy lithium-ion batteries: recent progress and a promising future in applications. Energy Environ. Mater. 2023, 6, e12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ye, H.; Wang, Y.; Qu, S.; Hu, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.; Jia, D.; Lin, H. Experimental validation of density functional theory predictions on structural water impact in vanadium oxide cathodes for zinc-ion batteries. Small 2024, 20, 2406801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Liang, Q.; Ding, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y. Pre-sodiation strategies for constructing high-performance sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 3206–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, N.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tan, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y. Electrolyte design enables stable and energy-dense potassium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2025, 64, e202415491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Geng, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Yan, C. Constructing sulfur-heterocyclic aromatic amine polymer with multiple-redox active sites for long-lifespan and all-organic aqueous magnesium ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2403934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Meng, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, J.; Li, A.; Huang, S. Challenges and strategies for zinc anodes in aqueous Zinc-Ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Zhu, G.; Dong, S.; Kong, Q.; Peng, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Dong, X.; Pang, H.; Zhang, Y. Co-intercalation of dual charge carriers in metal-ion-confining layered vanadium oxide nanobelts for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2023, 135, e202216089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wei, L. MXenes for zinc-based electrochemical energy storage devices. Small 2024, 20, 2304543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Wan, H.; Miao, L.; Jiang, J. Suppressing cathode dissolution via guest engineering for durable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 7631–7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Chen, G.; Hou, F.; Wang, L.; Liang, J. Strategies for the stabilization of Zn metal anodes for Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tie, Z.; Bi, S.; Niu, Z. Towards more sustainable aqueous zinc-ion Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2024, 136, e202403712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, S.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Pang, H. How about vanadium-based compounds as cathode materials for aqueous zinc ion batteries? Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2206907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yi, S.; Si, R.; Xi, B.; An, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Xiong, S. Advances on defect engineering of vanadium-based compounds for high-energy aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2202039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Han, L.; Zhang, W.; Guo, C. Vanadium-based cathodes for aqueous zinc ion batteries: structure, mechanism and prospects. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, J.-C.; Guo, Y.-F.; Wang, P.-F.; Zhu, Y.-R.; Yi, T.-F. Insights on rational design and energy storage mechanism of Mn-based cathode materials towards high performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 479, 215009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lu, M.; Cai, D.; Yang, H.; Han, W. Recent advances in energy storage mechanism of aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 54, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xi, B.; Chen, W.; Jia, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiong, S. Advances and perspectives of cathode storage chemistry in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9244–9272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, T.; Qiu, L.; Qu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y. Towards high-performance cathodes: Design and energy storage mechanism of vanadium oxides-based materials for aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 446, 214124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Pan, Z.; Cai, K. Controllable design of metal-organic framework-derived vanadium oxynitride for high-capacity and long-cycle aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Small 2024, 20, 2401922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lu, M.; Wang, B.; Cheng, H.; Yang, H.; Cai, D.; Han, W.; Fan, H.J. High-mass loading V3O7⸱H2O nanoarray for Zn-ion battery: New synthesis and two-stage ion intercalation chemistry. Nano Energy 2021, 83, 105835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Jia, M.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, L.; Cheng, F. Hydrated layered vanadium oxide as a highly reversible cathode for rechargeable aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Jiao, Z.; Xiao, M.; Huang, Q.; Liu, M.; Shao, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J. Prussian blue and its analogues as cathode materials for Na-, K-, Mg-, Ca-, Zn- and Al-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2022, 99, 107424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Lu, X.F.; Zhang, S.L.; Luan, D.; Li, S.; Lou, X.W. Construction of Co–Mn prussian blue analog hollow spheres for efficient aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2021, 60, 22189–22194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhu, L.; Xie, L.; Han, Q.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, G.; Cao, X. Cathode materials for aqueous zinc-ion batteries: A mini review. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2022, 605, 828–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Li, Z.; Xu, D.; Yang, Z. Multiple redox-active cyano-substituted organic compound integrated with MXene nanosheets for high-performance flexible aqueous Zn-ion battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2316182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, S.; Ali, N.; Kong, X.; Wang, J. High-performance organic electrodes for sustainable zinc-ion batteries: Advances, challenges and perspectives. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 71, 103544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, W.; Ye, F.; Dong, H.; Wu, Y.; Ma, R.; Hu, L. Multiple cations nanoconfinement in ultrathin V2O5 nanosheets enables ultrafast Ion diffusion kinetics toward high-performance zinc ion battery. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2312982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yi, S.; Si, R.; Xi, B.; An, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Xiong, S. Toward low-temperature zinc-ion batteries: strategy, progress, and prospect in vanadium-based cathodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2304010. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, A.; Wang, H.; Jin, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, F.; Chen, R. Organic intercalation induced kinetic enhancement of vanadium oxide cathodes for ultrahigh-loading aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Small 2024, 20, 2305030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shan, L.; Wu, Z.; Guo, X.; Fang, G.; Liang, S. Investigation of V2O5 as a low-cost rechargeable aqueous zinc ion battery cathode. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4457–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhao, P.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, B.; Pan, K.; Song, K.; Cheng, H. Heterojunction tunnelled vanadium-based cathode materials for high-performance aqueous zinc ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 665, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.-H.; Gao, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhan, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Chou, S.-L.; Dou, S.-X.; Cao, D. Vanadium-based cathodes for aqueous zinc-ion batteries: mechanism, design strategies and challenges. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 50, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Muhammad, S.; Sergey, C.; Lee, H.; Yoon, J.; Kang, Y.M.; Yoon, W.S. Advances in the cathode materials for lithium rechargeable batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2020, 59, 2578–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y. Outside-in nanostructure fabricated on LiCoO2 surface for high-voltage lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.D.; Shi, J.L.; Liang, J.Y.; Yin, Y.X.; Zhang, J.N.; Yu, X.Q.; Guo, Y.G. Suppressing surface lattice oxygen release of Li-rich cathode materials via heterostructured spinel Li4Mn5O12 coating. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Qiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; He, G.; Chen, H. Diminishing the migration resistance of zinc ions by cation vacancy engineering in a spinel-framework. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 4877–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Xu, Z.; Hu, W.; Ning, J.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, Y. Formation of sandwiched leaf-like CNTs-Co/ZnCo2O4@NC-CNTs nanohybrids for high-power-density rechargeable Zn-air batteries. Nano Energy 2021, 82, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundarrajan, V.; Sambandam, B.; Kim, S.; Mathew, V.; Jo, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Islam, S.; Kim, K.; Sun, Y.K.; Kim, J. Aqueous magnesium zinc hybrid battery: an advanced high-voltage and high-energy MgMn2O4 cathode. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1998–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Lan, B.; Tang, C.; An, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Zou, C.; Dong, S.; Luo, P. Urchin-like spinel MgV2O4 as a cathode material for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3681–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Cui, M.; Hu, T.; Meng, C. Dual ions enable vanadium oxide hydration with superior Zn2+ storage for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Naveed, A.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Dou, A.; Su, M.; Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Li, C.C. Magnesium ion doping and micro-structural engineering assist NH4V4O10 as a high-performance aqueous zinc ion battery cathode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2306205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Hu, P.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Y.; Pan, X.; Sun, W.; Li, S.; Xue, J.; An, Q.; Mai, L. Revealing excess Al3+ preinsertion on altering diffusion paths of aluminum vanadate for zinc-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 52, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Magnesium (mg/kg)×104 |

Vanadium (mg/kg)×104 |

Aluminium (mg/kg)×104 |

Mg/V/Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-MgVO | 10.98 | 37.24 | 2.58 | 1.23/2/0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).