2.1. Material Characterization

In contrast to the commonly utilized nitrogen source, urea, the thiourea molecule features a less stable C=S double bond and amino

p-π conjugated bonds, thereby facilitating a more ready detachment of nitrogen. Leveraging this property, thiourea was chosen as the nitrogen precursor, vanadium acetylacetonate as the vanadium source, and glucose as the carbon scaffold, for the hydrothermal synthesis of N-V

2O

3/C. The structural paradigm of V

2O

3, depicted in

Figure 1a, showcases a trigonal crystal system (space group

c) characterized by a three-dimensional lattice conducive to electron mobility within vanadium-vanadium (V-V) chain frameworks, thus exhibiting metallic properties. Vanadium atoms are strategically positioned within two-thirds of the octahedral sites formed by oxygen atoms. This arrangement is further complemented by the connectivity of two [VO

6] octahedra with their neighboring atoms through shared corners, faces, and edges, culminating in a tunnel-like three-dimensional matrix. Such a configuration is optimally designed to support the facile insertion and extraction of metal ions, pivotal for the material's electrochemical performance.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns reveal the successful synthesis of the desired product. Within the V

2O

3/C composite, the absence of characteristic carbon peaks suggests the involvement of carbon in an amorphous form, which does not impede the crystallinity of V

2O

3 (

Figure 1b). Furthermore, the presence of a nitrogen-doped carbon coating in the N-V

2O

3/C composite does not hinder the formation of V

2O

3, as evidenced in

Figure 1c.

The microstructural characteristics of the synthesized specimens were examined through scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM images of V

2O

3/C, depicted in

Figures 2a-c at varying magnifications, illustrate that the composite is composed of nanoparticles with irregular shapes. Conversely, N-V

2O

3/C is characterized by nanospheres of a more uniform and regular morphology, as shown in

Figures 2d-f. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping of N-V

2O

3/C, provided in

Figure 2g, demonstrates a homogeneous distribution of the elements V, O, and N. The extensive presence of carbon is due to the conductive adhesive, highlighting its role in the composite's structure.

2.2. Electrochemically Induced Phase Transition

In this study, 3M Zn(CF

3SO

3)

2 was employed as the electrolyte, with zinc foil serving as the anode and synthesized products utilized as cathodes to fabricate button cells, aimed at evaluating their electrochemical performance. Initial tests involved constant current charge-discharge assessments, depicted in

Figures 3a and 3d. Notably, a distinct difference was observed in the electrochemical profiles between the initial and subsequent cycles of the two cells, indicating a pronounced overcharging phenomenon.

For the cell incorporating V2O3/C as the cathode material, an initial discharge capacity of 52 mAh g−1 was recorded, which significantly increased to a charging capacity of 1618 mAh g−1. In the cycles that followed, the capacity reached a relatively stable value of approximately 284.3 mAh g−1, with the observed voltage plateaus at 1.10/0.99 V and 0.62/0.87 V, respectively. Similarly, the cell featuring N-V2O3/C as the cathode exhibited an initial discharge capacity of 335.2 mAh g−1 and a charging capacity of 1773.1 mAh g−1. Subsequently, the capacity of this cell stabilized around 332.2 mAh g−1, with voltage plateaus at 1.18/1.01 V and 0.68/0.87 V, respectively.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) analysis was conducted at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s

−1 for both cells, with results presented in

Figures 3b and 3e. The analysis revealed a significant shift in the positions of oxidation and reduction peaks from the first cycle to subsequent cycles in both cells, indicative of irreversible phase transformations. Specifically, the initial cycle for V

2O

3/C was characterized by pronounced oxidation peaks at 0.68 and 1.52 V. In contrast, during the second cycle, these peaks were observed to migrate to 0.96/0.79 V and 1.22/1.09 V, respectively, with subsequent cycles demonstrating considerable overlap, implying the formation of a phase transition product with favorable reversibility. Similarly, the oxidation and reduction peak positions of N-V

2O

3/C closely matched those of V

2O

3/C, suggesting analogous reaction mechanisms. This alignment is corroborated by constant current charge and discharge profiles, which exhibited notable consistency across cycles, further confirming the reversibility of the phase transition product, in a manner comparable to V

2O

3/C.

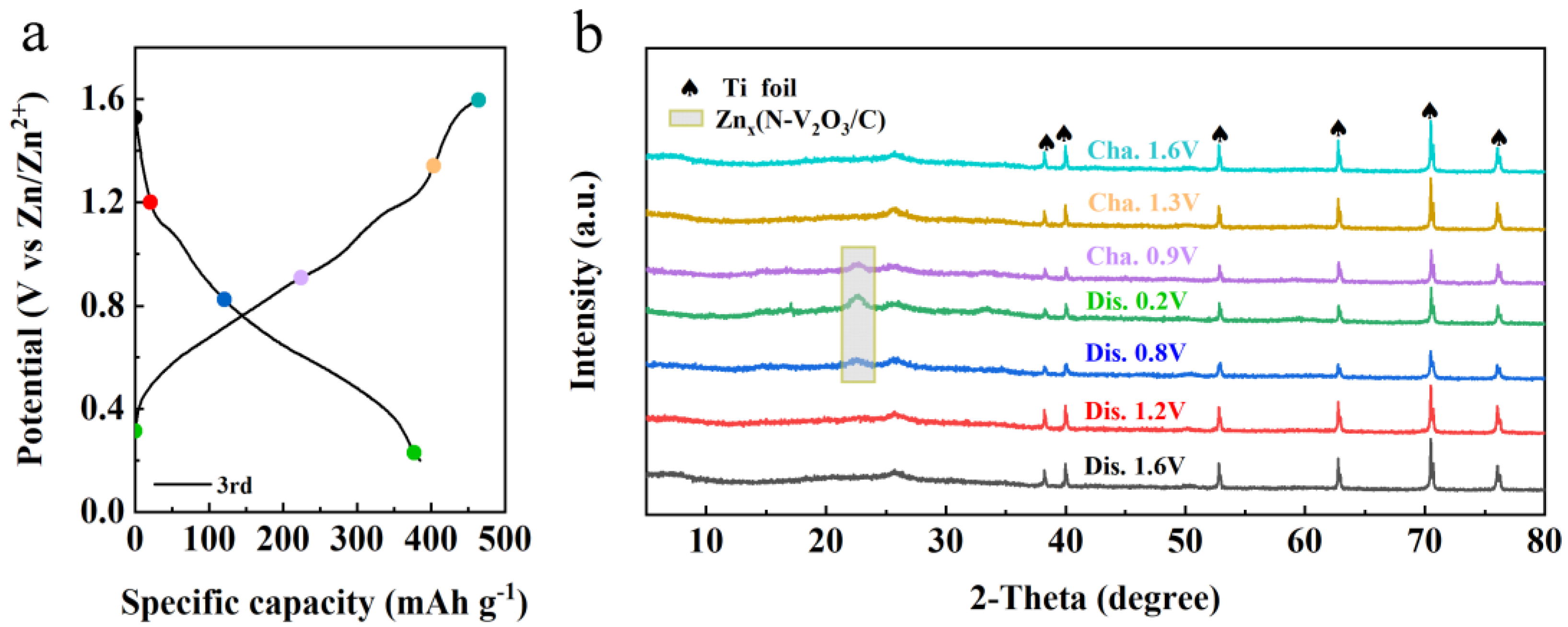

To gain comprehensive insights into the electrochemical changes occurring within the cells, XRD analyses were performed on the cathode materials post-charging, as illustrated in

Figures 3c and 3f. The analyses demonstrated that following the initial charging process, the distinct characteristic peaks of both V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C were eradicated, indicating a transformation to an amorphous, non-crystalline state.

Post-cycling morphological transformations of V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C electrodes were meticulously examined via scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The analysis revealed that, throughout the course of electrochemical reactions, the V

2O

3/C electrodes underwent a morphological evolution from irregularly shaped nanoparticles to nanorods of diminished diameter (refer to

Figures 4a-b). In a contrasting manner, N-V

2O

3/C electrodes transitioned from well-defined nanospheres to nanosheets (illustrated in

Figures 4c-d). This alteration significantly enhanced their specific surface area, thereby optimizing them for improved Zn

2+ ion storage capabilities.

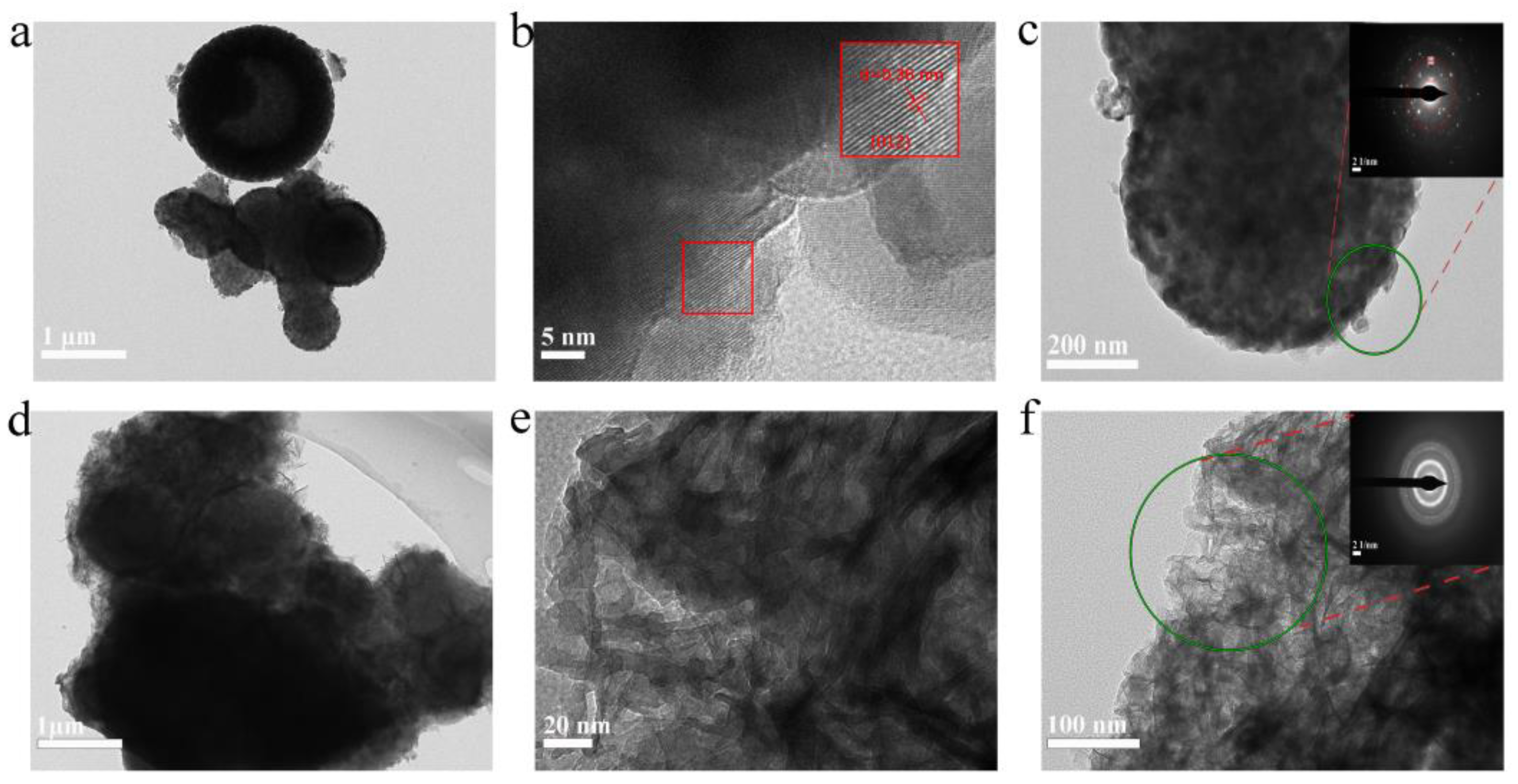

The morphological and microstructural evolutions of N-V

2O

3/C following its phase transition were meticulously characterized through High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM). Prior to electrochemical cycling,

Figure 5a delineates the material's initial structure as nanospheres encased by irregular entities, which were identified as amorphous carbon. The HRTEM imagery distinctly highlighted lattice fringes, elucidating that the introduction of nitrogen doping and carbon encapsulation preserved the crystalline integrity of V

2O

3.

This finding is in harmony with the crystallinity observations reported in the XRD analysis (refer to

Figure 1c). The Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) pattern of N-V

2O

3/C, depicted in

Figure 5c, before cycling, exhibited luminous diffraction rings. These rings correspond to the (012), (024), and (018) crystallographic planes of V

2O

3, affirming the polycrystalline essence of the material. Post-charging, the N-V

2O

3/C specimens transformed into more voluminous, albeit irregular and thinner structures, as illustrated in

Figures 5d and 5e. The SAED pattern after cycling, shown in

Figure 5f, revealed a diffuse halo devoid of sharp boundaries, a manifestation that aligns with the XRD findings post-cycling. This unequivocally corroborates the electrochemical induction of a phase transition to an amorphous state after the initial cycle of charging and discharging.

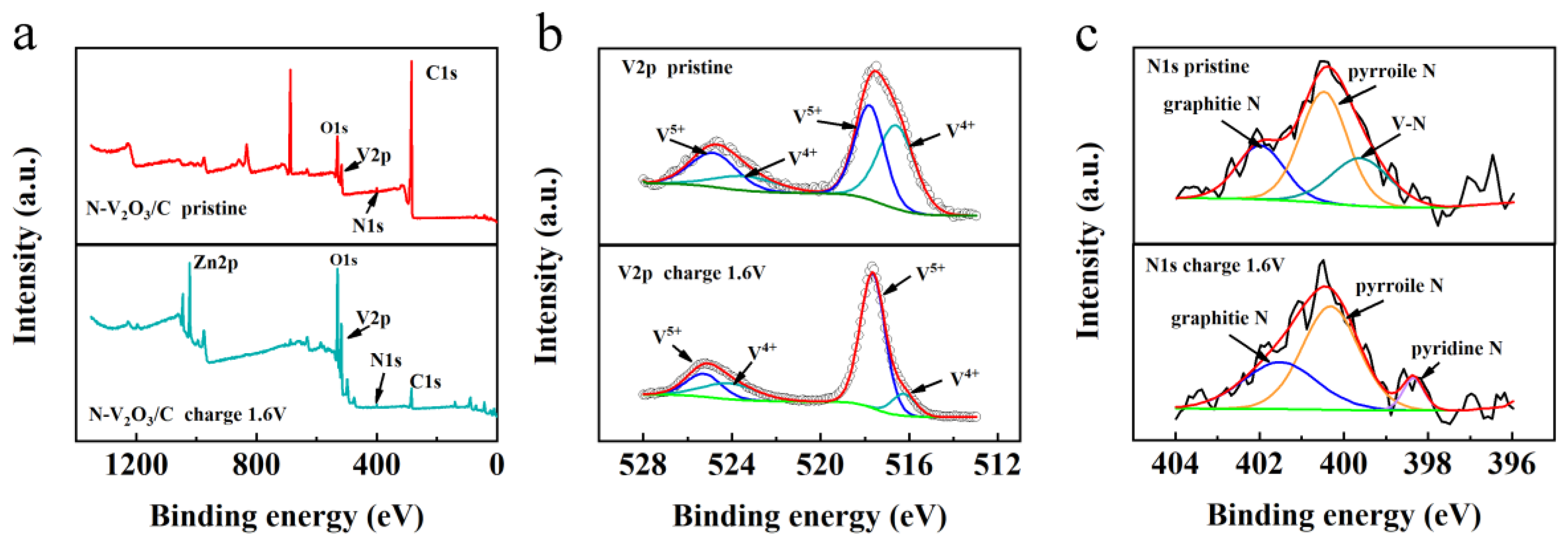

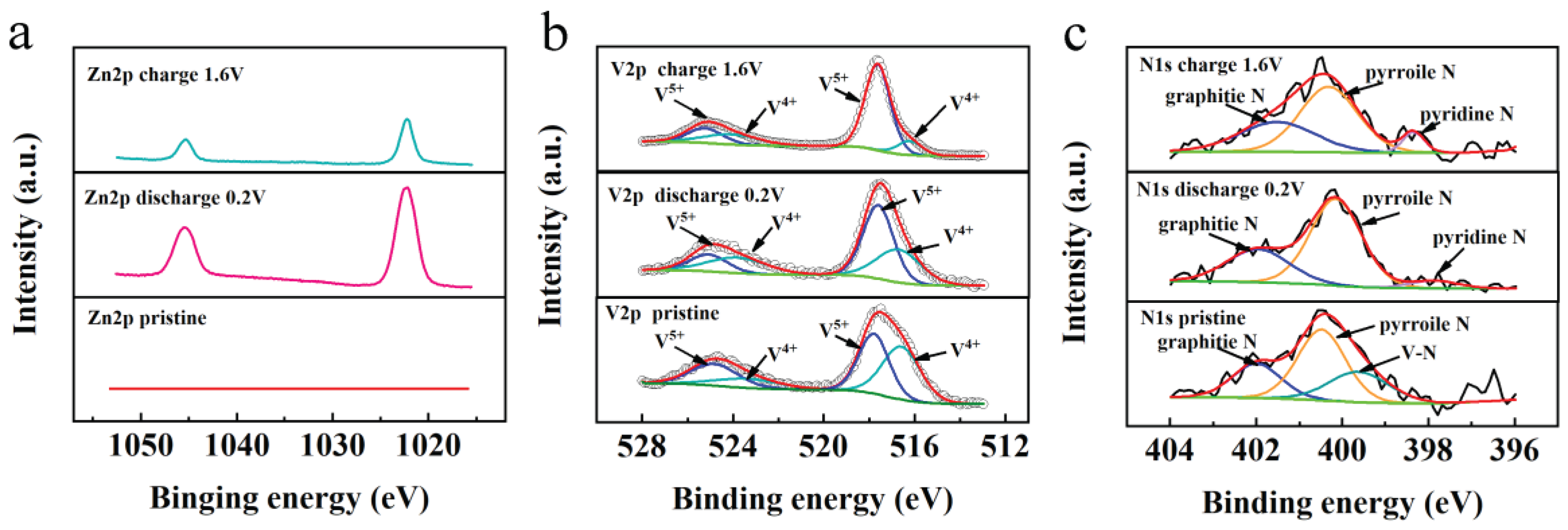

XPS was utilized to elucidate the chemical compositions and the states of elements within N-V

2O

3/C, both prior to and subsequent to the inaugural charging cycle, with the findings illustrated in

Figures 6. The survey spectrum, as presented in

Figure 6a, confirmed the presence of N, vanadium (V), oxygen (O), and carbon (C) in the pristine N-V

2O

3/C. Notably, post-charging, the spectrum also revealed the presence of Zn. Detailed examination of the V 2p fine spectrum, depicted in

Figure 6b, revealed that the binding energies in the pristine sample were predominantly observed at 524.8/517.7 eV and 523.4/516.7 eV, indicative of the oxidation states V

4+ and V

5+, respectively. Following the charging process, the oxidation states of vanadium remained as V

4+ and V

5+. However, a discernible augmentation in the proportion of V

5+ was evident from the enhanced intensity and area of the respective peaks, setting a foundation for an escalated occurrence of redox reactions in subsequent stages [

28].

Additionally, the investigation into the N component within N-V

2O

3/C unveiled that the initial N binding energies were predominantly positioned at 399.6, 400.4, and 401.8 eV. These correspond to V-N bonds, pyrrolic N, and graphitic N, respectively, as illustrated in

Figure 6c. Post-charging, the formation of pyridinic N was observed, with both pyrrolic and pyridinic N exhibiting more negative electronegativities. This characteristic is advantageous for enhancing the transport rate of Zn

2+ ions.

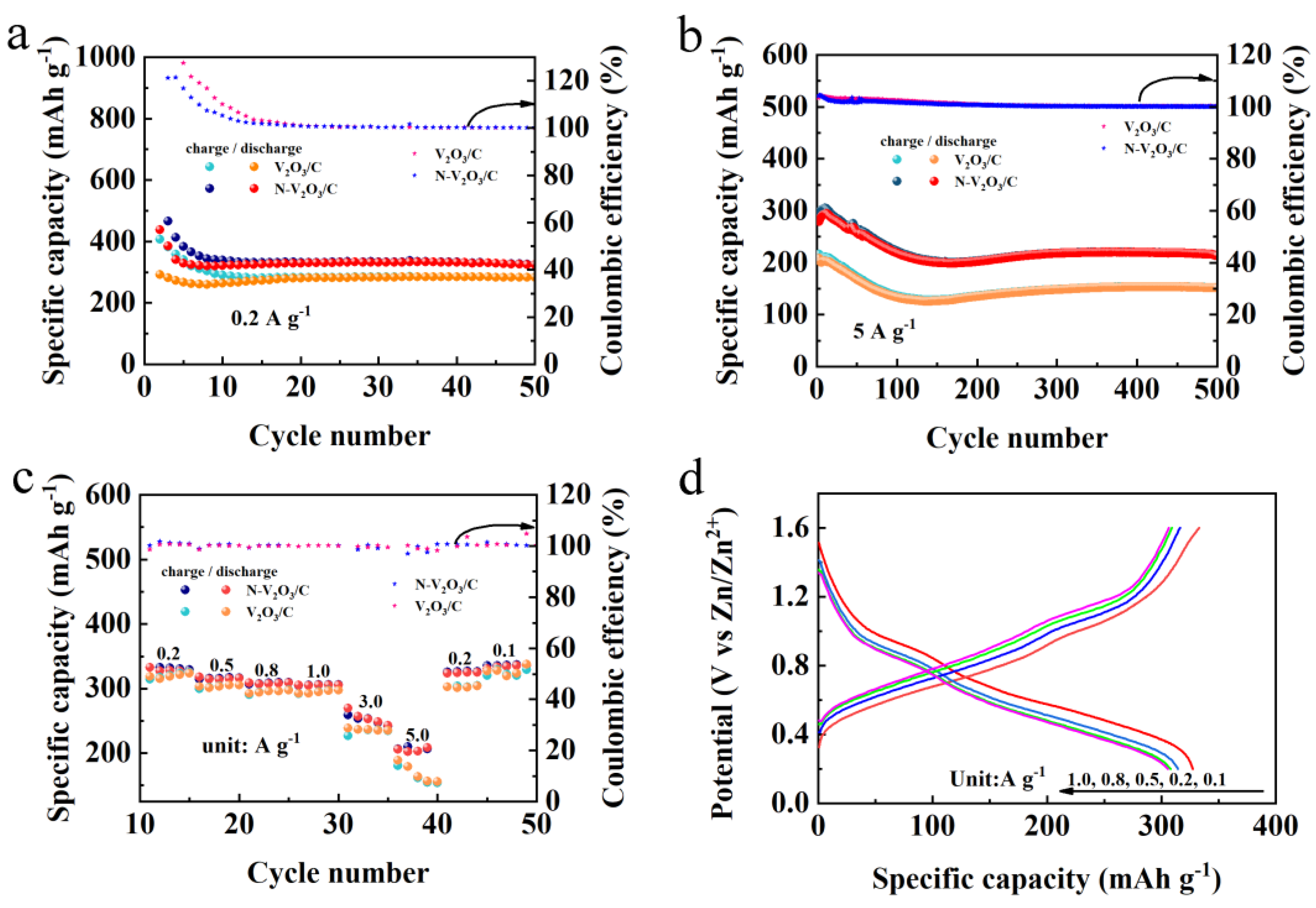

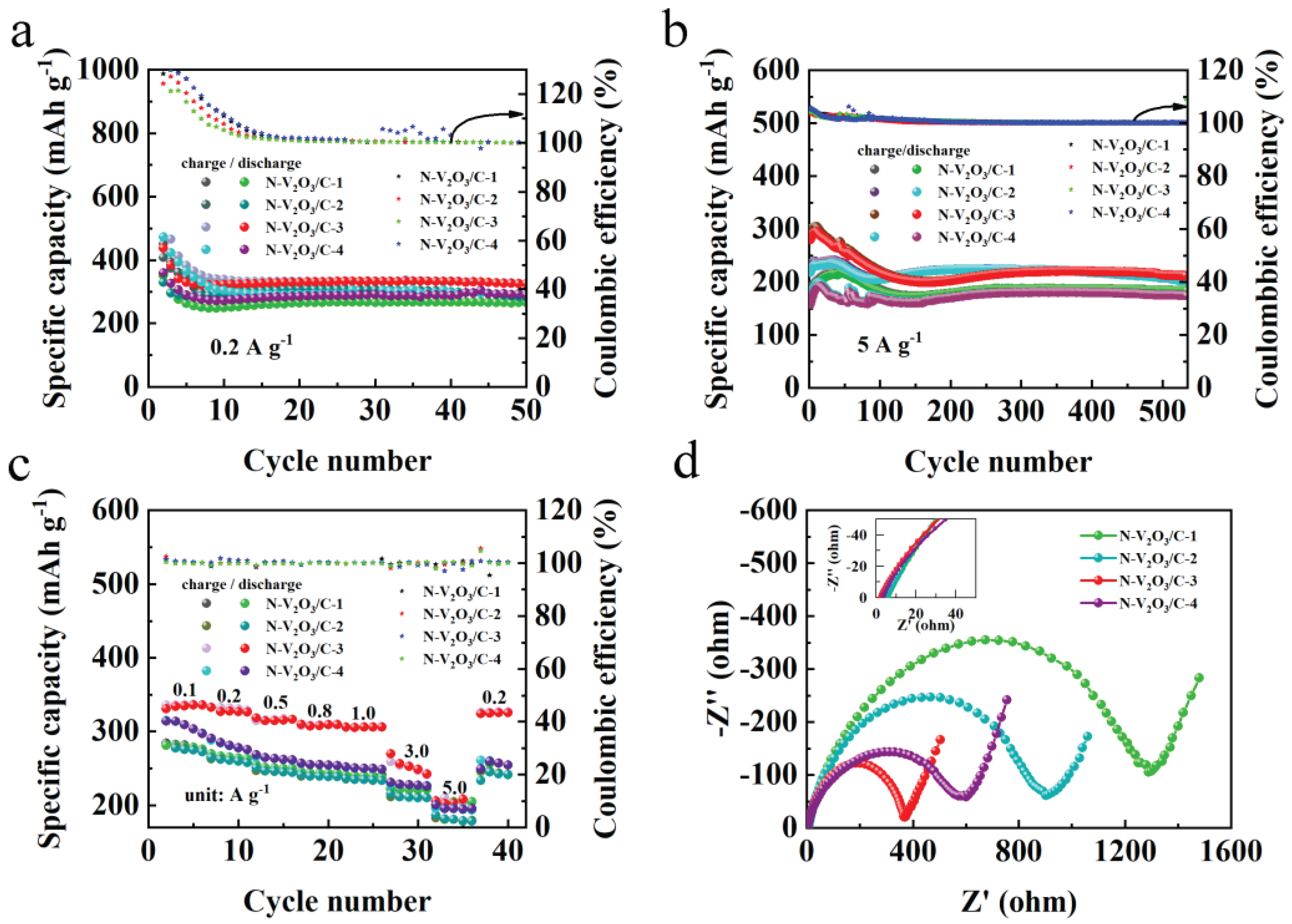

2.3. Electrochemical Performance

To investigate the post-phase transition electrochemical behavior of V

2O

3/C and N-doped V

2O

3/C, these materials were utilized as cathodes within AZIBs. Initially subjected to a current density of 0.2 A g

−1, the cycling performance depicted in

Figure 7a demonstrates that both V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C exhibited notably high specific capacities for both charging and discharging within the initial 10 cycles, alongside a coulombic efficiency surpassing 100%. This phenomenon is ascribed to the phase transition experienced by the cathode materials under subdued current densities, which precluded the attainment of a fully stable structural configuration, thereby leading to the misalignment of charge and discharge profiles. Beyond the preliminary 10 cycles, a commendable degree of stability was observed for both electrodes; V

2O

3/C recorded a capacity of 284.6 mAh g

−1, whereas N-V

2O

3/C demonstrated a superior capacity of 331.1 mAh g

−1. Subsequent to the initial evaluation, cycling performance at an escalated current density of 5 A g

−1 was assessed, as illustrated in

Figure 7b. Mirroring the low-current density findings, an activation process for the electrodes was discernible. Following an extended cycling duration of approximately 150 cycles, a stabilization in capacities was noted, with V

2O

3/C attaining a capacity of 242.6 mAh g

−1 and N-V

2O

3/C achieving a capacity of 264.1 mAh g

−1, each maintaining a coulombic efficiency of 100%.

The rate performance of V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C following the stabilization of phase transition was systematically evaluated across a spectrum of current densities, namely 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0 A g

−1, as illustrated in

Figure 7c. Initial observations reveal that, at lower current densities, the specific capacities of both materials exhibit considerable similarity. However, with an increment in current density, N-V

2O

3/C not only manifests enhanced specific capacities but also displays augmented stability, underscoring its remarkable resilience against high current demands. This finding aligns with the patterns discerned during the cycling performance assessments, where the augmented electrochemical robustness of N-V

2O

3/C was evident. Remarkably, upon the diminution of current densities, both V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C succeeded in reinstating their original specific capacities, thereby demonstrating their exceptional rate capabilities.

Further,

Figure 7d delineates the constant current charge-discharge profiles for both electrodes across varying current densities, mirroring the observed rate performances. A noteworthy aspect of these profiles is the presence of two pronounced and analogous charge-discharge plateaus, pinpointed at 0.97/1.07 V and 1.02/1.22 V, respectively. These plateaus are in harmony with the oxidation and reduction peak positions previously identified in the CV analysis of N-V

2O

3/C.

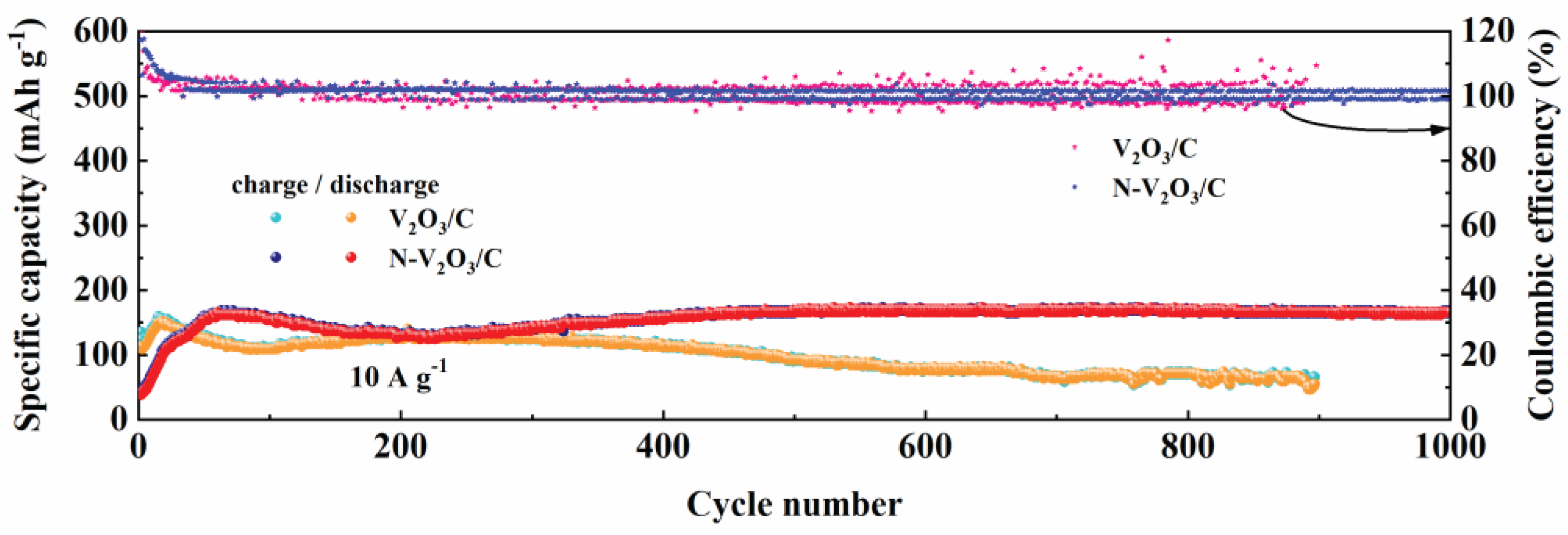

Figure 8 delineates the enduring cycling performance of both V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C under a substantial current load of 10 A g

−1. In the initial cycles, V

2O

3/C demonstrated an initial specific capacity of 110.3 mAh g

−1, in contrast to N-V

2O

3/C, which registered a notably lower capacity of 40.6 mAh g

−1. However, an upward trajectory in the capacities of both materials was observed thereafter, a phenomenon attributed to the progressive activation of the electrodes. Upon reaching full activation, the specific capacities were recorded at 151.6 mAh g

−1 for V

2O

3/C and an elevated 168.4 mAh g

−1 for N-V

2O

3/C. Post 900 cycles, V

2O

3/C’s capacity was reduced to 56.2 mAh g

−1, correlating to a capacity retention rate of 37%. Contrastingly, N-V

2O

3/C showcased remarkable endurance, maintaining a capacity of 160.5 mAh g

−1 even after 1000 cycles, which translates to an impressive retention rate of 95%. These findings underscore the substantial enhancement in capacity retention and cycling stability conferred by nitrogen doping.

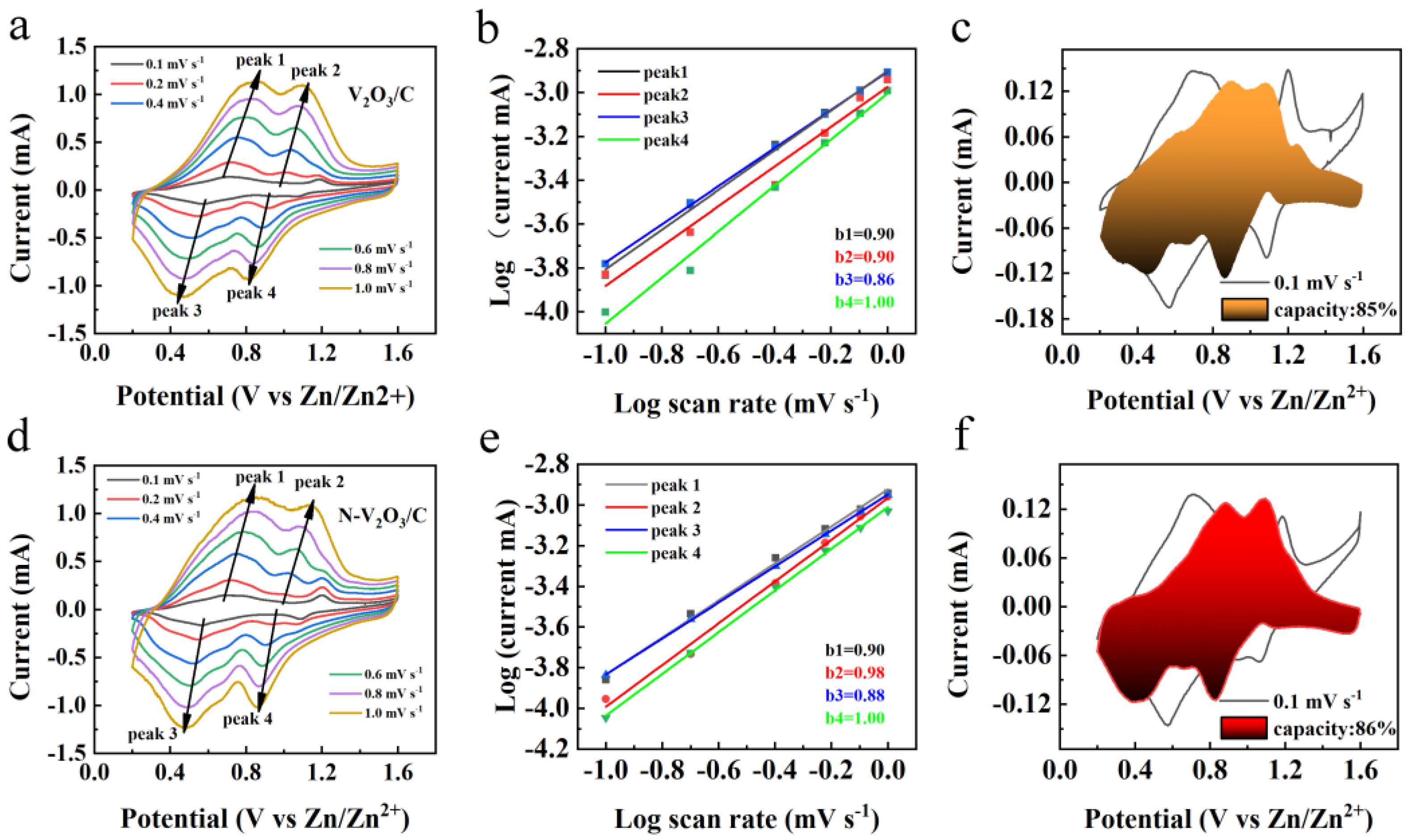

To elucidate the kinetic mechanisms underlying the electrochemical behavior of V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C, CV analyses were conducted across a spectrum of scan rates (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 mV s

−1), with the results depicted in

Figures 9a and 9d. Observations revealed analogous oxidation and reduction peaks for both materials, suggesting the occurrence of comparable electrochemical reactions. Notably, an escalation in scan rate led to a polarization-induced shift of these peaks to higher and lower potentials for oxidation and reduction processes, respectively. The empirical relationship between the peak current (

i) and the scan rate (

v) is formalized as follows:

Within these formulations, parameters

a and

b are indicative of the system's electrochemical dynamics, with b serving as a determinant of the dominant control mechanism—diffusion or pseudocapacitance. Specifically, a

b value nearing 1.0 is indicative of pseudocapacitive control, whereas a value approaching 0.5 signifies diffusion dominance. Intermediate

b values suggest a mixed control mechanism. The linear regression analyses of log(

i) versus log(v) for both V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C, presented in

Figures 9b and 9e, respectively, yielded b values predominantly within the range of 0.5 to 1.0, implying a significant influence from both diffusion and pseudocapacitance on the electrochemical reactions. Crucially, a b value of 1.0 for both materials underscores the substantial role of pseudocapacitive behavior in certain electrode processes, contributing to their enhanced rate capabilities. Additionally, CV profiles at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s

−1, showcased in

Figures 9c and 9f, alongside the deduced pseudocapacitive contributions of 85% for V

2O

3/C and 86% for N-V

2O

3/C.

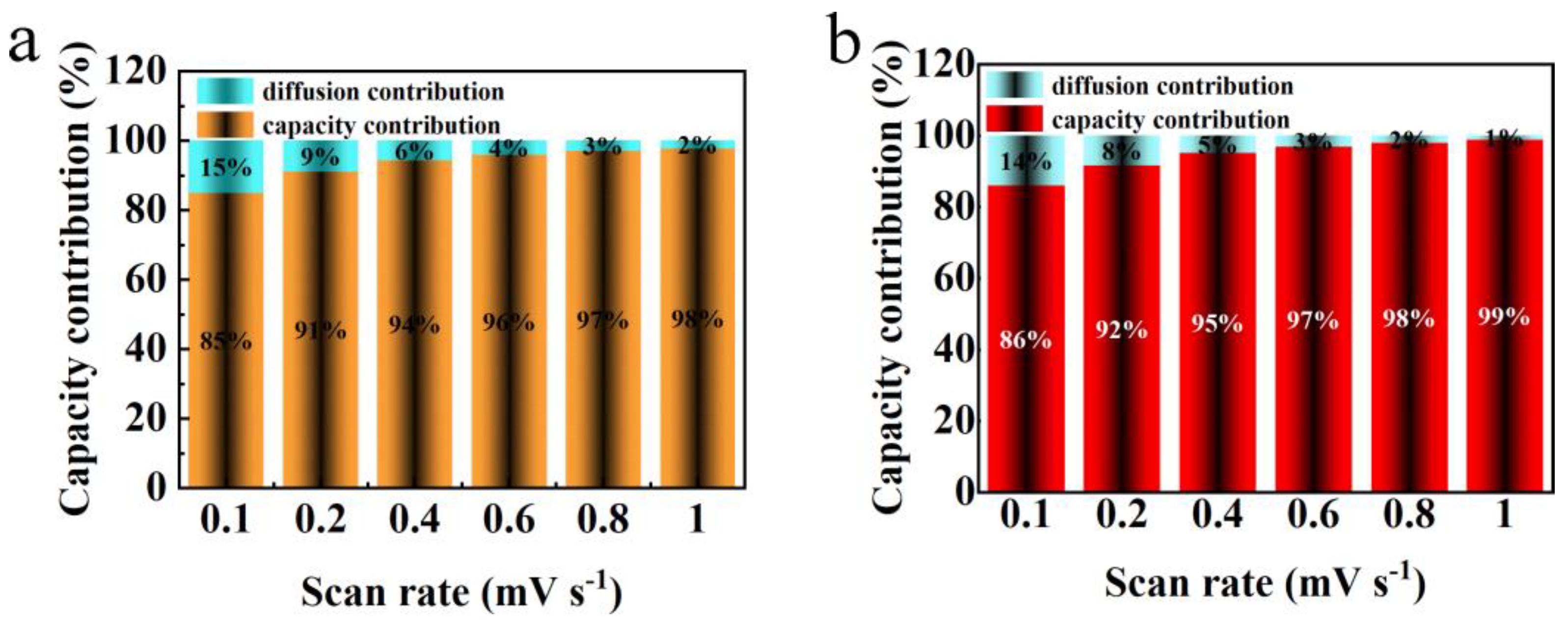

Figure 10 illustrates the variation in pseudocapacitive contribution rates for the electrode materials V

2O

3/C and N-V

2O

3/C across a spectrum of scan rates. The pseudocapacitive contributions for V

2O

3/C are recorded at 85%, 91%, 94%, 96%, 97%, and 98% for increasing scan rates, respectively. Conversely, the corresponding values for N-V

2O

3/C are slightly higher, being 86%, 92%, 95%, 97%, 98%, and 99%, respectively. This upward trend in pseudocapacitance with escalating scan rates signifies a shift towards more capacitive-dominated electrochemical reactions for both materials, a trait that enhances cyclic durability especially under conditions of high current. Remarkably, the consistently higher pseudocapacitive contributions observed for N-V

2O

3/C as compared to V

2O

3/C underscore superior electrochemical kinetics. This distinction not only underpins an improved diffusion rate for Zn

2+ ions but also aligns with the observed enhancements in cyclic and rate performances of the materials.

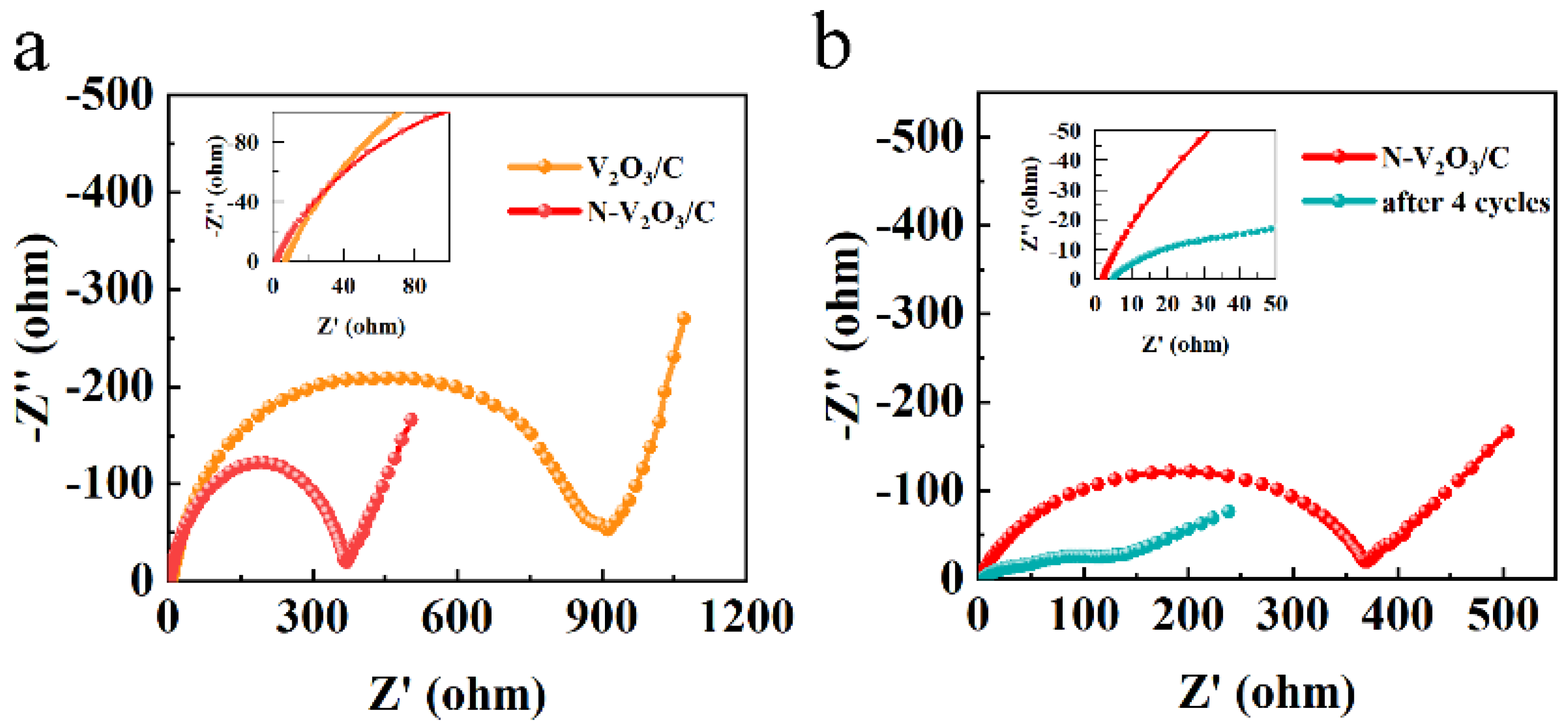

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyses were executed employing an electrochemical workstation, with outcomes illustrated in

Figure 11a. These outcomes revealed a semicircle in the high-frequency range, indicative of charge transfer resistance, and a linear slope in the low-frequency range, indicative of ion diffusion processes. Importantly, the N-V

2O

3/C exhibited a markedly reduced charge transfer resistance in comparison to V

2O

3/C, which aligns with their respective electrochemical performances. Upon conducting four cycles, a notable reduction was observed in both charge transfer resistance and ion diffusion for N-V

2O

3/C, as demonstrated in

Figure 11b, thereby augmenting its electronic conductivity. This enhancement substantiates the observed initial capacity increment throughout the cycling process.

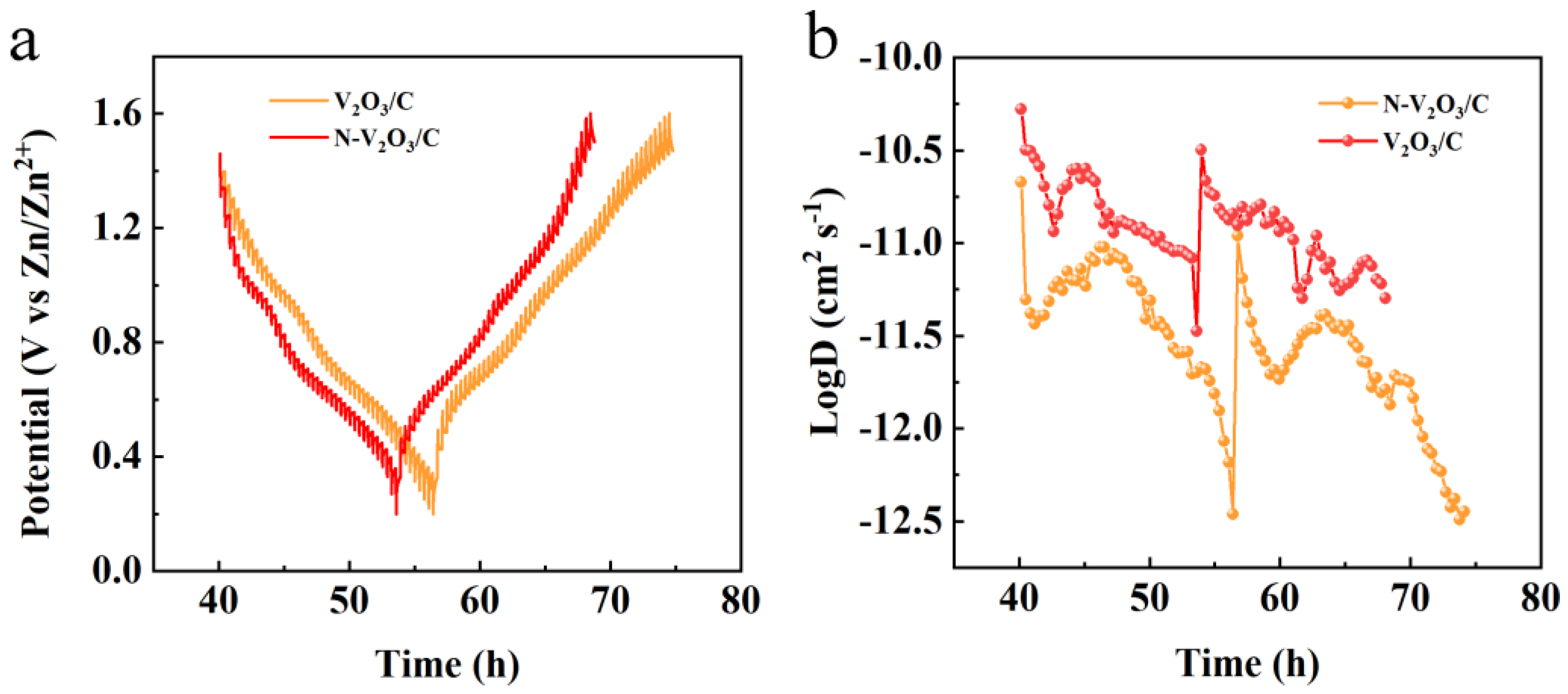

The Zn

2+ diffusion coefficient was quantified employing the Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT), which substantiated the enhancement of ionic kinetics subsequent to nitrogen doping. The GITT experimentation was executed with a specified current density of 0.1 A g

−1, a relaxation time (τ) of 30 minutes, and measurement intervals set at 60 seconds.

Figure 12b reveals that the diffusion coefficient for V

2O

3/C was observed to lie between 10

−11 and 10

−12 cm

2 s

−1. Conversely, for N-V

2O

3/C, the Zn

2+ diffusion coefficient was determined to be within the range of 10

−10 to 10

−11 cm

2 s

−1.

2.4. Mechanistic Investigation

To elucidate the zinc storage mechanism within the N-V

2O

3/C matrix following its phase transition, ex-XRD examinations were performed throughout the third charge/discharge cycle.

Figure 13b reveals minimal alterations in peak positions during the initial discharge phase, aligning with observations post the inaugural charge cycle (refer to

Figure 3f). Notably, discharging to 0.8 V resulted in the emergence of a novel peak at 22.4°, indicative of a reaction between Zn

2+ ions and N-V

2O

3/C, culminating in the formation of Zn

x(N-V

2O

3/C). The intensity of this peak was further amplified upon discharging to 0.2 V. Conversely, the peak's intensity waned as the charging process reached 0.9 V and, upon completion of charging to 1.6 V, all peaks representative of intermediate phases vanished. This phenomenon underscores the structure’s pronounced reversibility concerning Zn

2+ ion intercalation and deintercalation processes.

XPS analyses were conducted to elucidate the elemental state transformations in N-V

2O

3/C throughout the third charging and discharging cycle. Initially, the Zn 2p spectrum exhibited no detectable Zn signals (

Figure 14a). This absence changed upon discharging the material to 0.2 V, at which point a prominent pair of Zn 2p peaks at 1022.2 eV and 1045.1 eV became evident, denoting the successful intercalation of Zn

2+ ions. However, upon full recharge to 1.6 V, these Zn 2p peaks markedly diminished in intensity, albeit not vanishing entirely, hinting at a partial, irreversible incorporation of Zn

2+ ions.

The valence state dynamics of V were detailed in

Figure 14b, where initial spectra revealed two peak pairs located at 524.8/517.7 eV and 523.4/516.7 eV, attributed to the V

4+ and V

5+ oxidation states in V 2p3/2, respectively. The discharge to 0.2 V resulted in a notable shift in the V

4+/V

5+ ratio, which was further altered upon recharging to 1.6 V. At this juncture, an increase in the V

5+ content was observed, indicating the reversion of vanadium valence states post-Zn

2+ deintercalation.

Additionally, changes in the chemical state of nitrogen, as indicated by N 1s spectra (

Figure 14c), were observed. A marginal increase in pyridinic nitrogen content was detected following discharge to 0.2 V, which amplified upon complete recharge. This alteration is posited to account for the accelerated diffusion rate of Zn

2+ ions in N-V

2O

3/C relative to its V

2O

3/C counterpart during the electrochemical cycle.

2.4. Investigation of Nitrogen Content

To investigate the impact of nitrogen doping levels on performance, the synthesis process involved varying the molar ratios of the vanadium source acetylacetonate vanadium to the nitrogen source thiourea as 2:1, 2:2, 2:3, and 2:4, using 0.076 g, 0.152 g, 0.228 g, and 0.304 g of thiourea respectively. These were designated as N-V2O3/C-1, N-V2O3/C-2, N-V2O3/C-3, and N-V2O3/C-4, respectively.

From the cycling performance at a current density of 0.2 A g

−1 (

Figure 15a), it can be observed that these materials all undergo similar cycling experiences. In the first 10 charge-discharge cycles, their charge and discharge profiles do not overlap, with the Coulombic efficiency exceeding 100%, indicative of a transition from phase change to stability. After 10 cycles, the charge and discharge begin to stabilize, among which N-V

2O

3/C-3 exhibits the highest capacity after 50 cycles, reaching 331.1 mAh g

−1.

Figure 15b presents the cycling performance at a current density of 5 A g

−1. It is evident that their cycling processes are similar, among which N-V

2O

3/C-3 has the highest initial capacity. When reaching a stable cycle, N-V

2O

3/C-2 exhibits a relatively higher capacity, but its retention rate is not as favorable. After 500 cycles, N-V

2O

3/C-3 shows the highest capacity and the best retention rate, achieving 111%.

In

Figure 15c, the rate performance of N-V

2O

3/C electrodes, with varying levels of nitrogen doping, is evaluated across a series of current densities: 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0 A g

−1. Notably, the electrode designated N-V

2O

3/C-3 consistently demonstrated the most superior capacity, exhibiting negligible variation over the tested current density range. Furthermore, this electrode's ability to recover its initial capacity upon the reduction of current density to lower rates signifies its exceptional rate capability. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis, depicted in

Figure 15d, reveals that N-V

2O

3/C-3 possesses the minimal electrochemical charge transfer and ionic diffusion resistances among the tested materials, establishing a robust basis for its outstanding electrochemical attributes. The observed lower contact resistance of N-V

2O

3/C-3 also provides insight into its enhanced initial capacity, further validating the material's electrochemical efficiency.

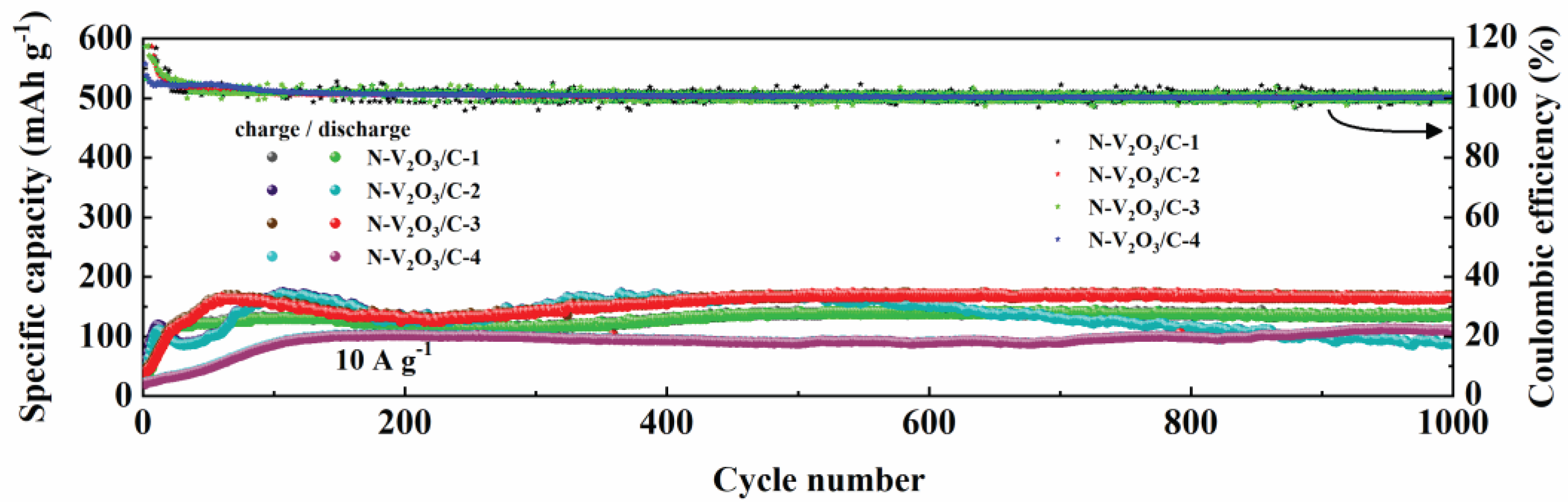

The long-term cycling stability of N-V

2O

3/C electrodes, differentiated by their nitrogen content, was rigorously evaluated under a high current density condition of 10 A g

−1. As depicted in

Figure 16, a trend towards stabilization was observed for all materials after an initial 100 cycles. Upon extending the cycling to 1000 cycles, the following observations were made: N-V

2O

3/C-1 demonstrated a stable capacity of 135.7 mAh g

−1, maintaining a retention rate of 100%. N-V

2O

3/C-2 recorded a capacity of 87.1 mAh g

−1, with a significantly lower retention rate of 51%. N-V

2O

3/C-3 showcased a superior capacity of 168.5 mAh g

−1, accompanied by a retention rate of 102%, whereas N-V

2O

3/C-4 achieved a capacity of 109.9 mAh g

−1, marking the highest retention rate among the samples at 111%. Notably, while N-V

2O

3/C-4 exhibited the highest retention rate, its initial capacity was comparatively lower. Conversely, N-V

2O

3/C-3 not only presented the highest initial capacity but also maintained a relatively high retention rate, underscoring that the electrochemical performance reached its zenith when the vanadium and nitrogen sources were combined at a molar ratio of 2:3. This composition was found to yield the most favorable outcomes in terms of both capacity and durability.