Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method Applied to Synthesize the Alloys

2.2. Characterization Methods

2.2. Electrochemical Characterization

3. Results

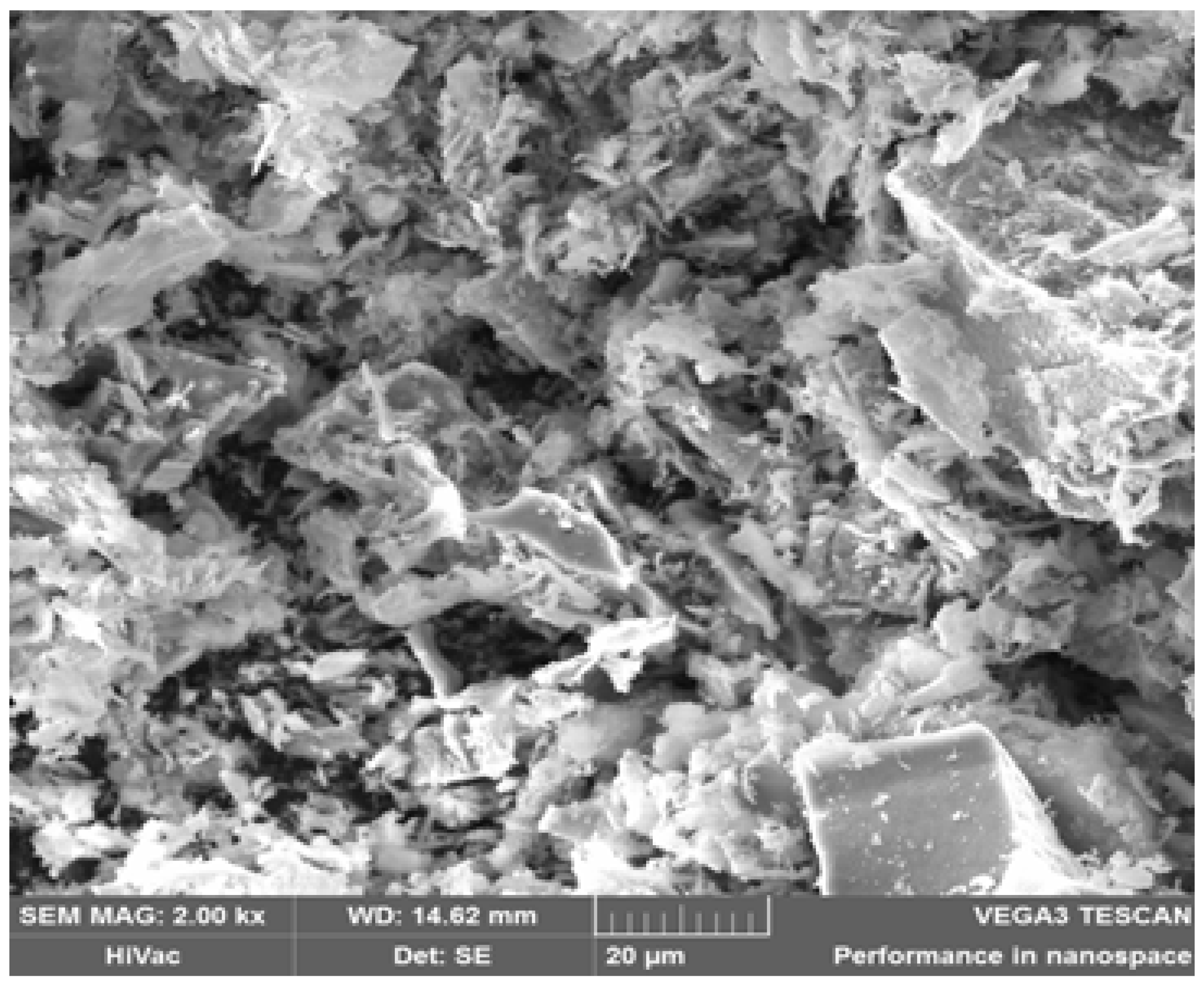

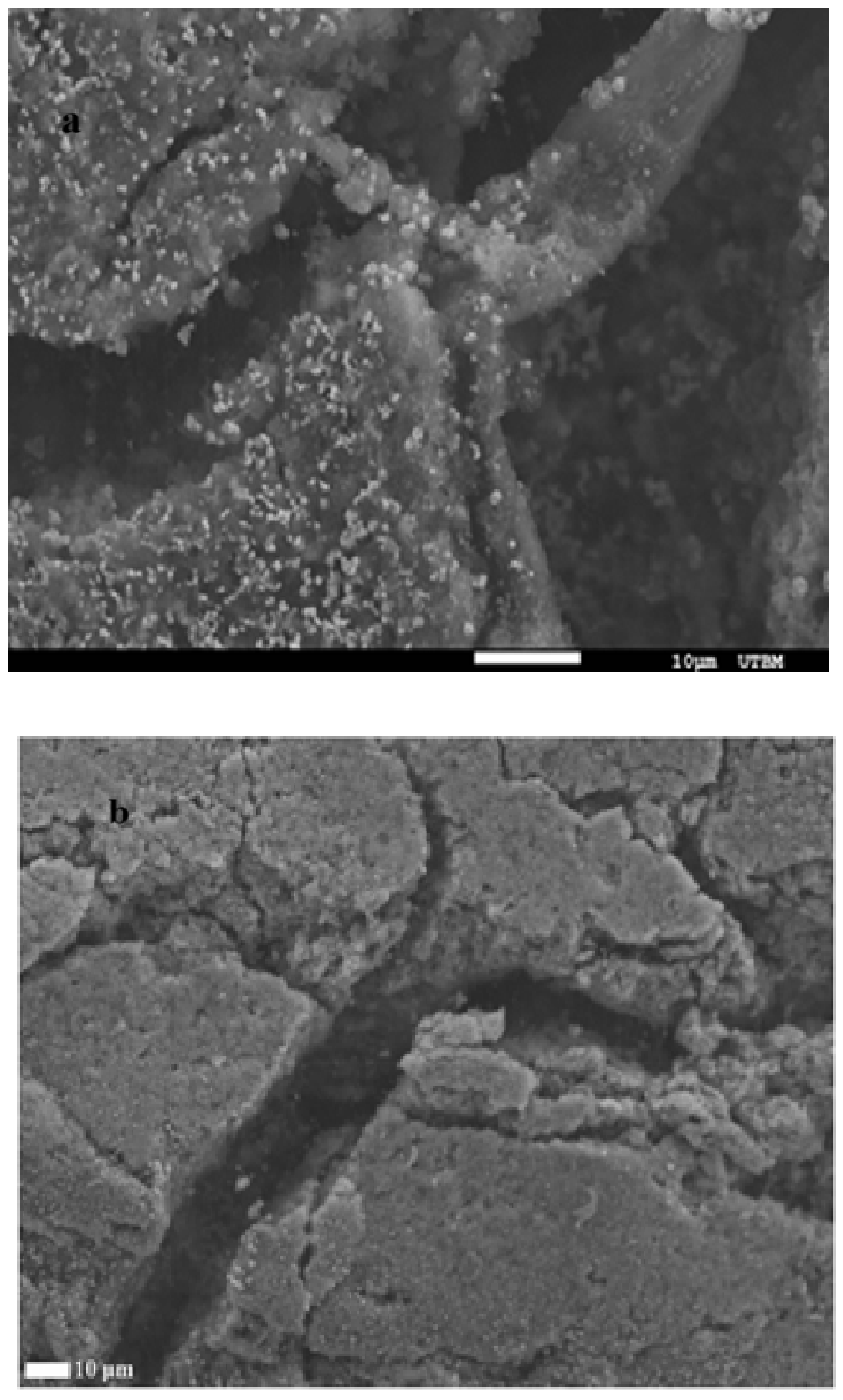

3.1. SEM Observations

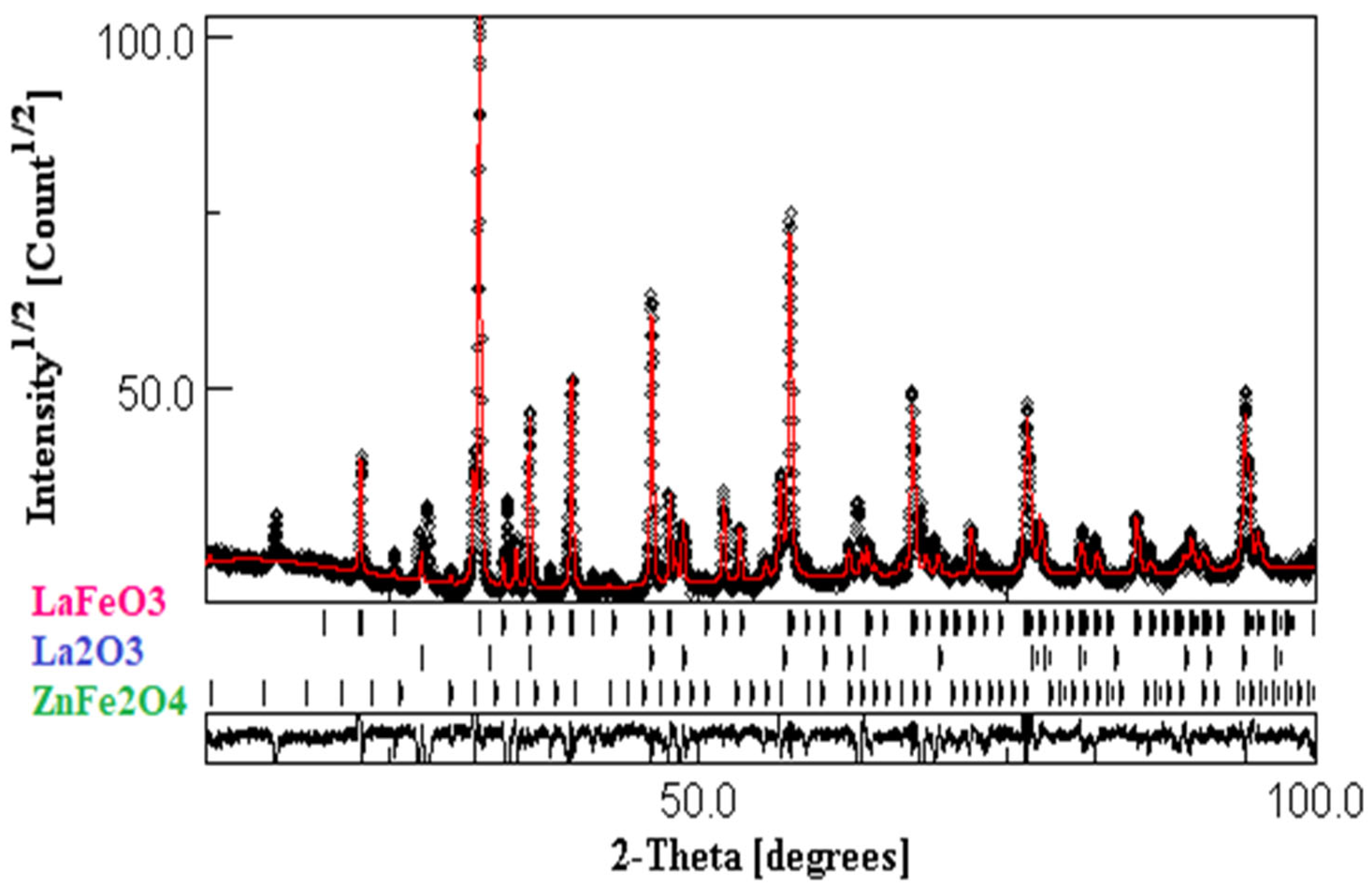

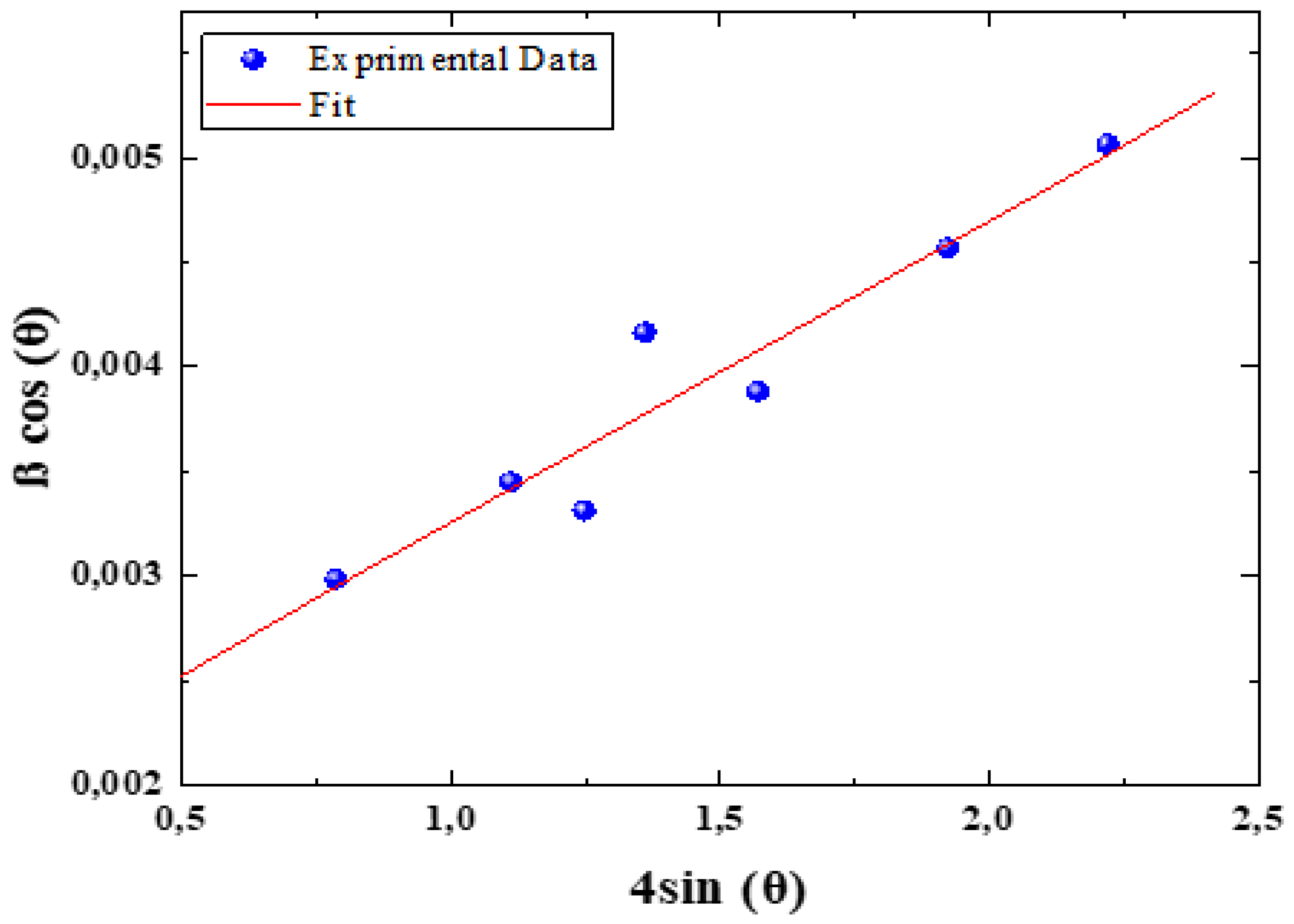

3.2. Structural Properties

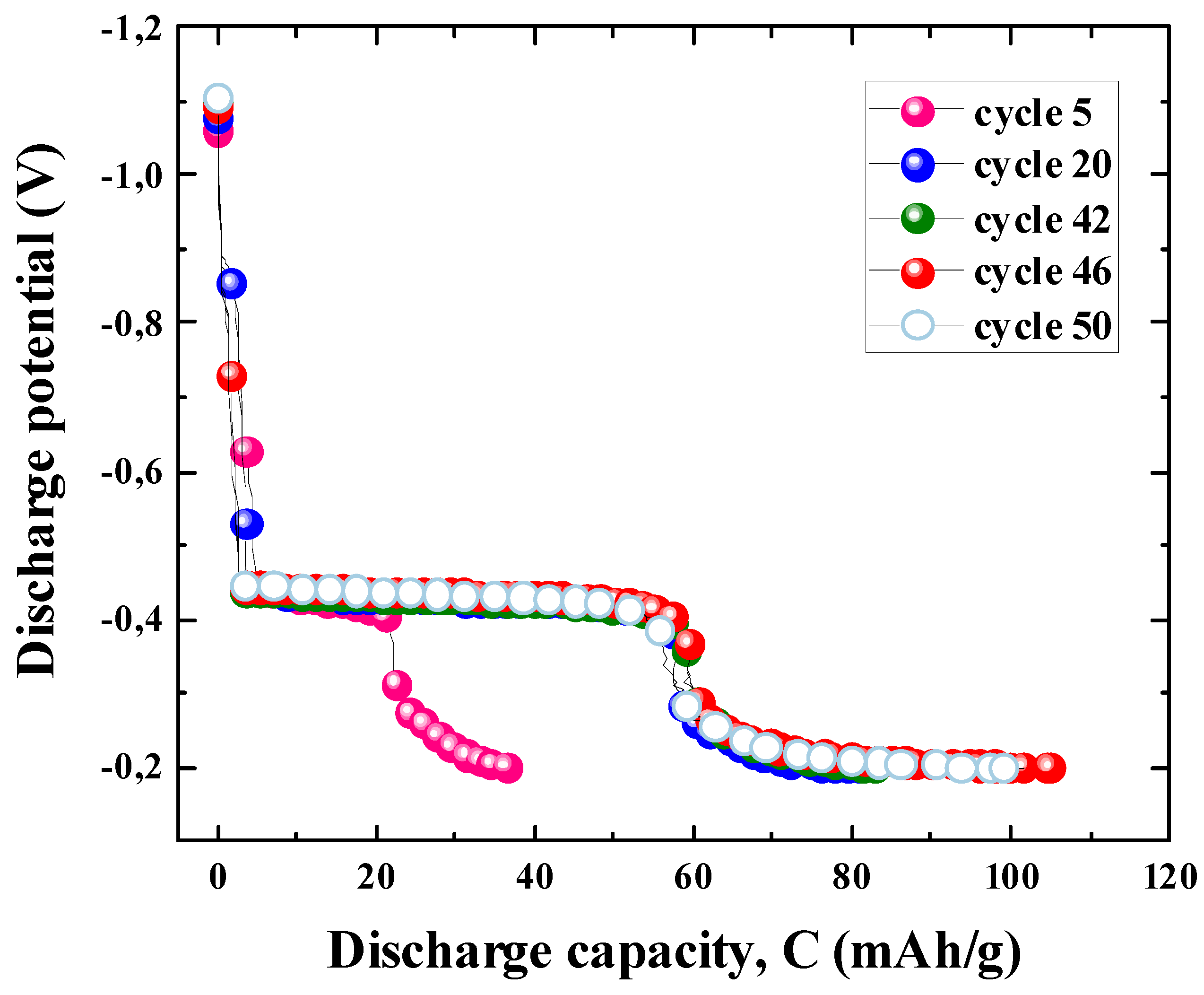

3.2. Cycling Properties of the ZnLaFeO4 Electrode Using the Galvanostatic Method

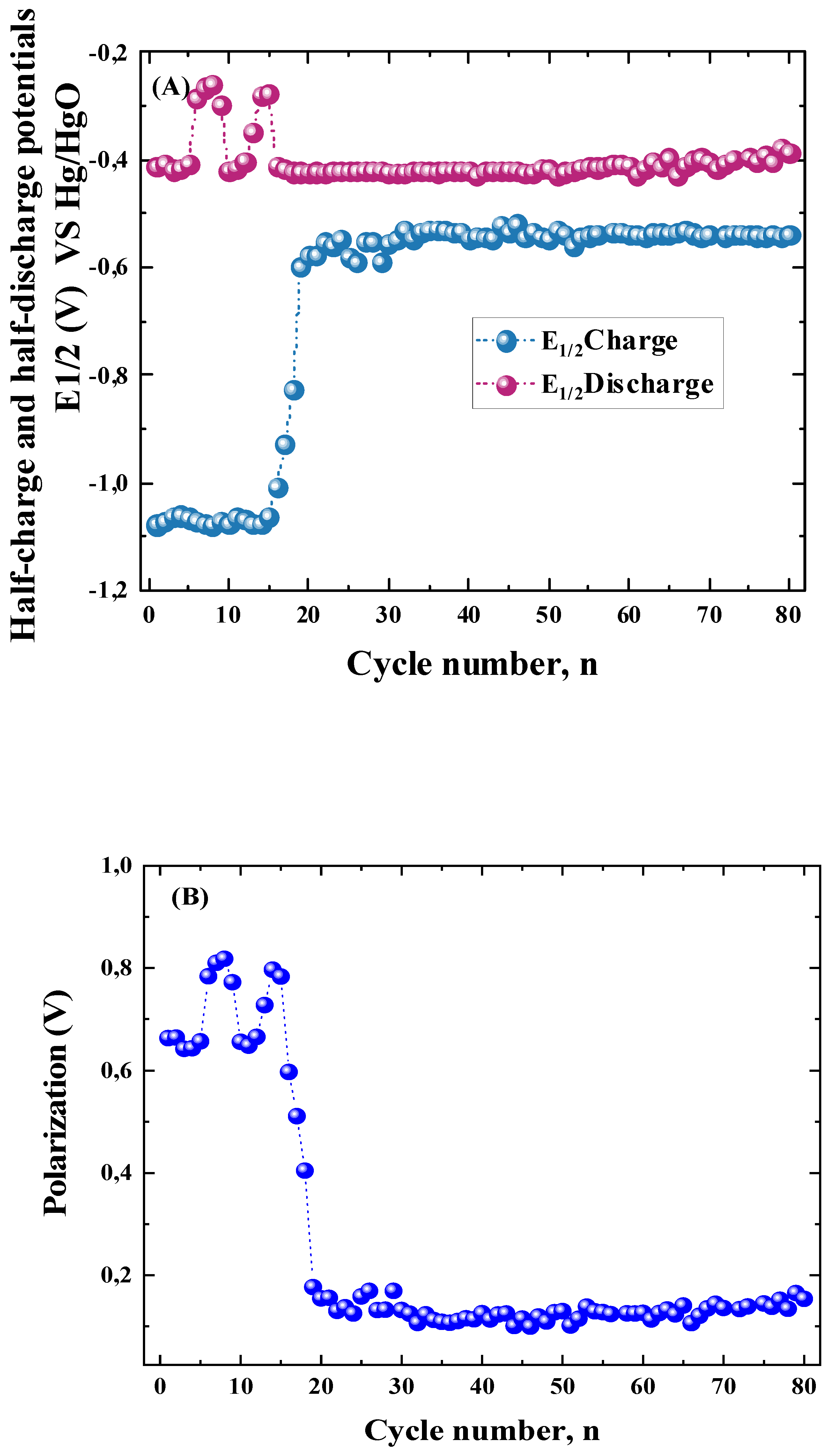

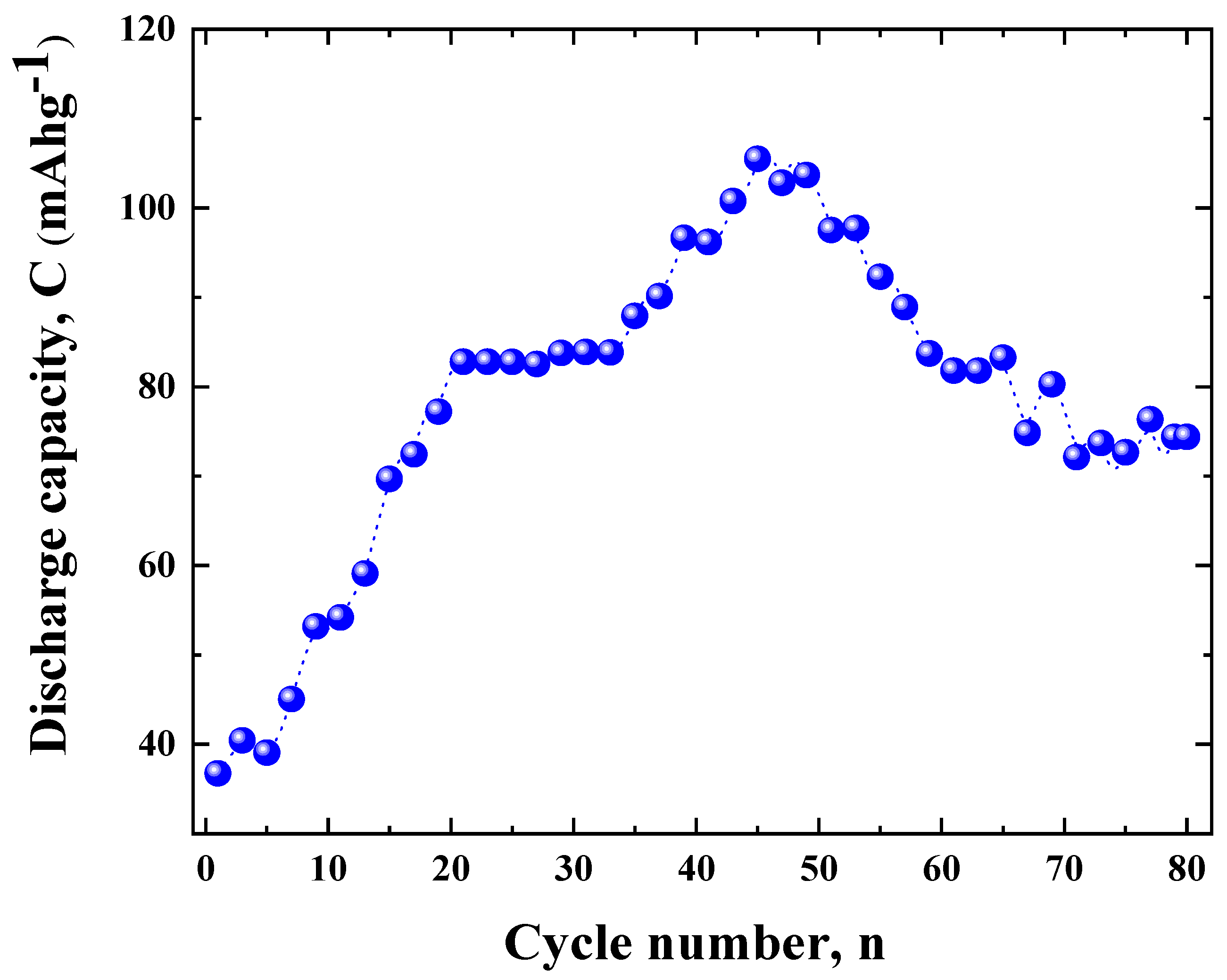

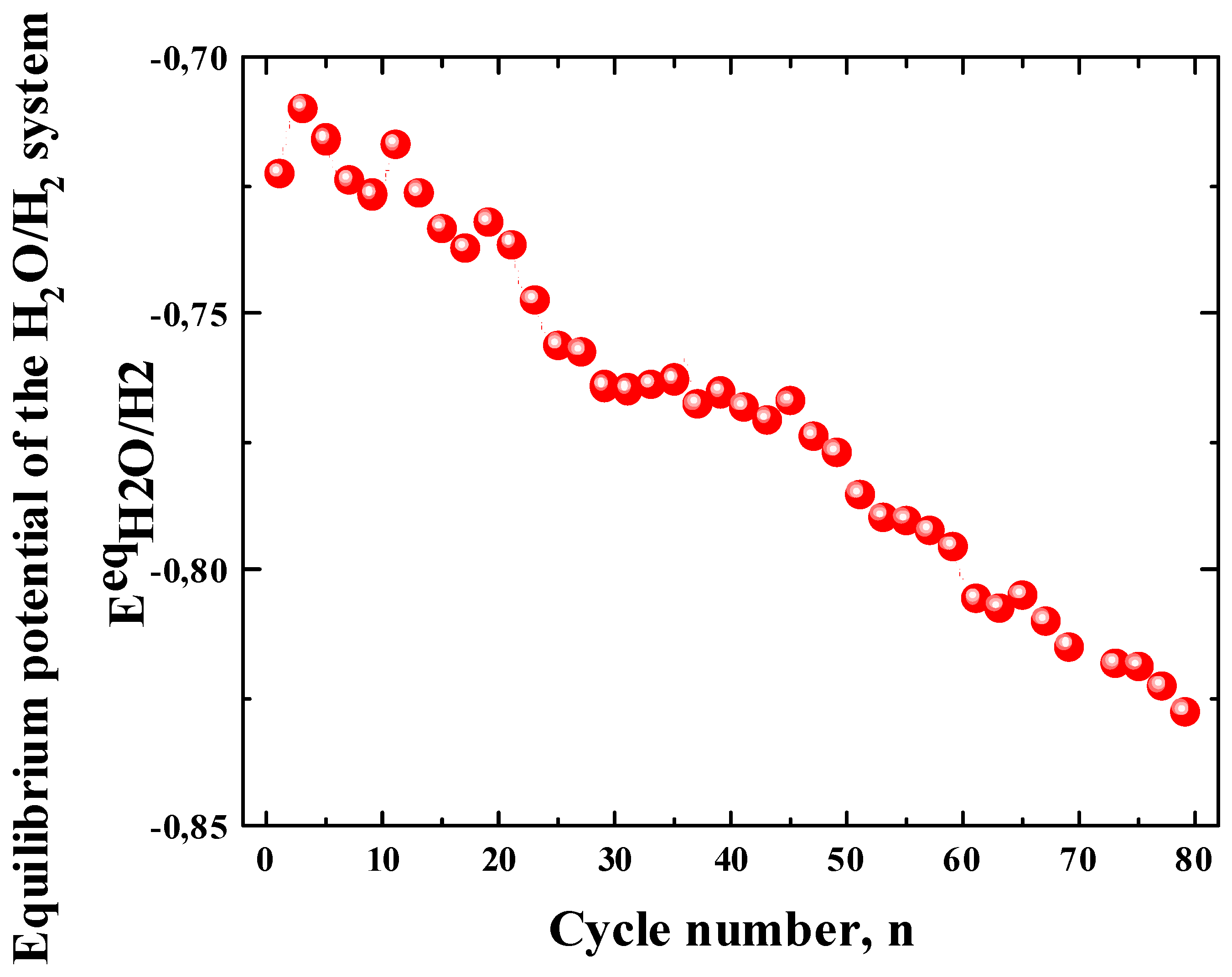

3.2.1. Activation Process of the ZnLaFeO4 Electrode

3.2.2. Cycling Properties of the ZnLaFeO4 Electrode

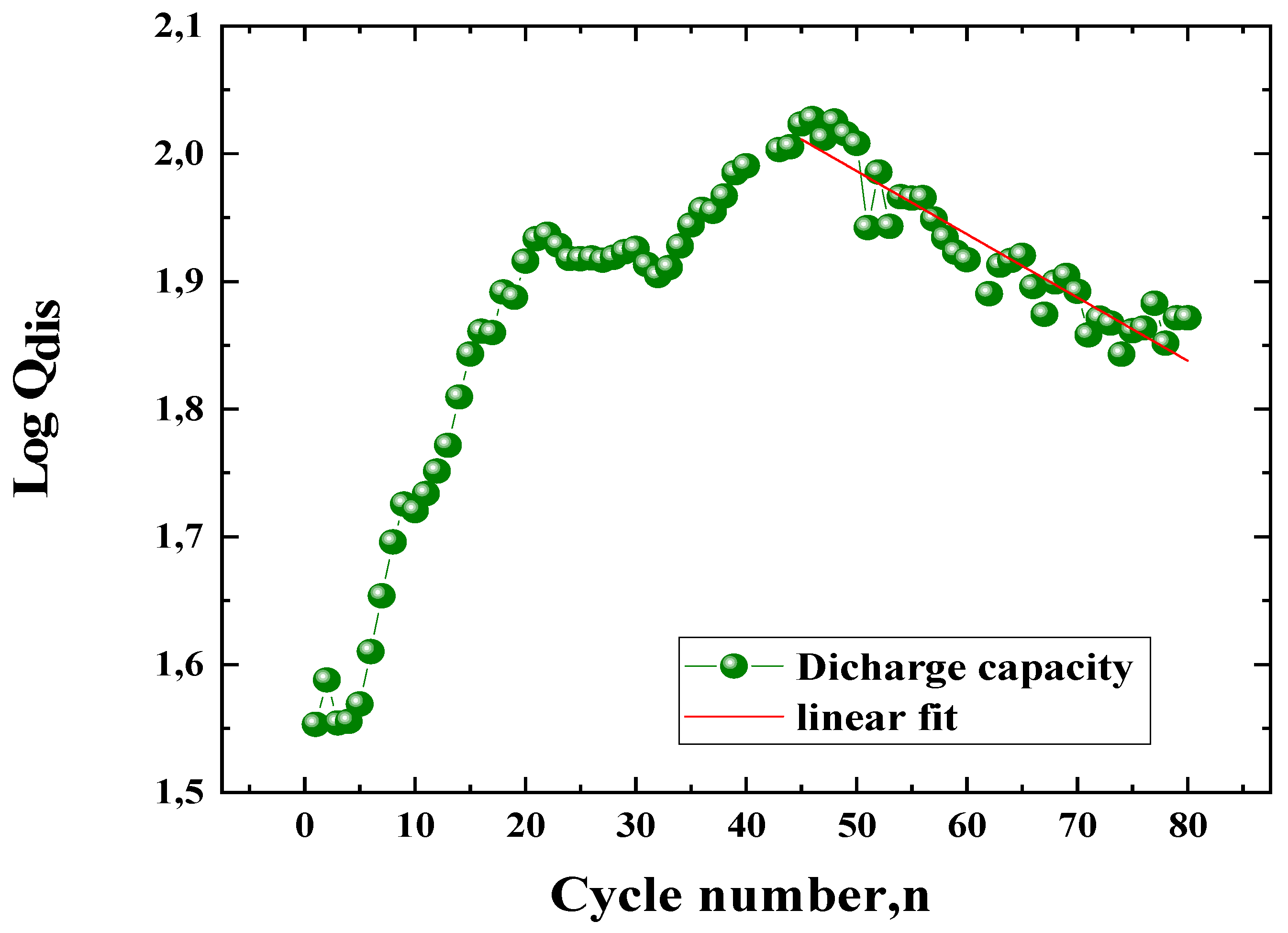

3.2.3. Electrode Degradation Process

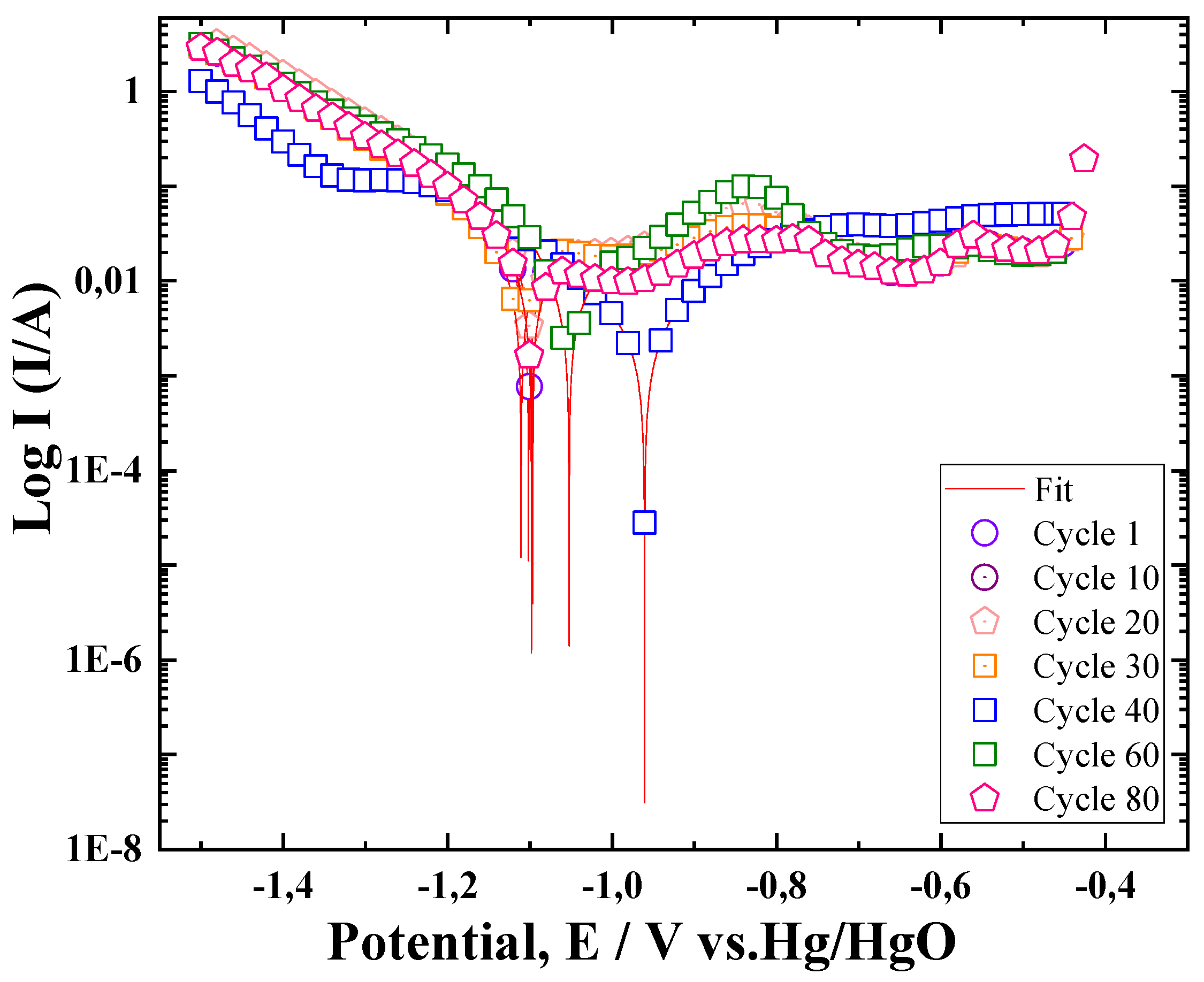

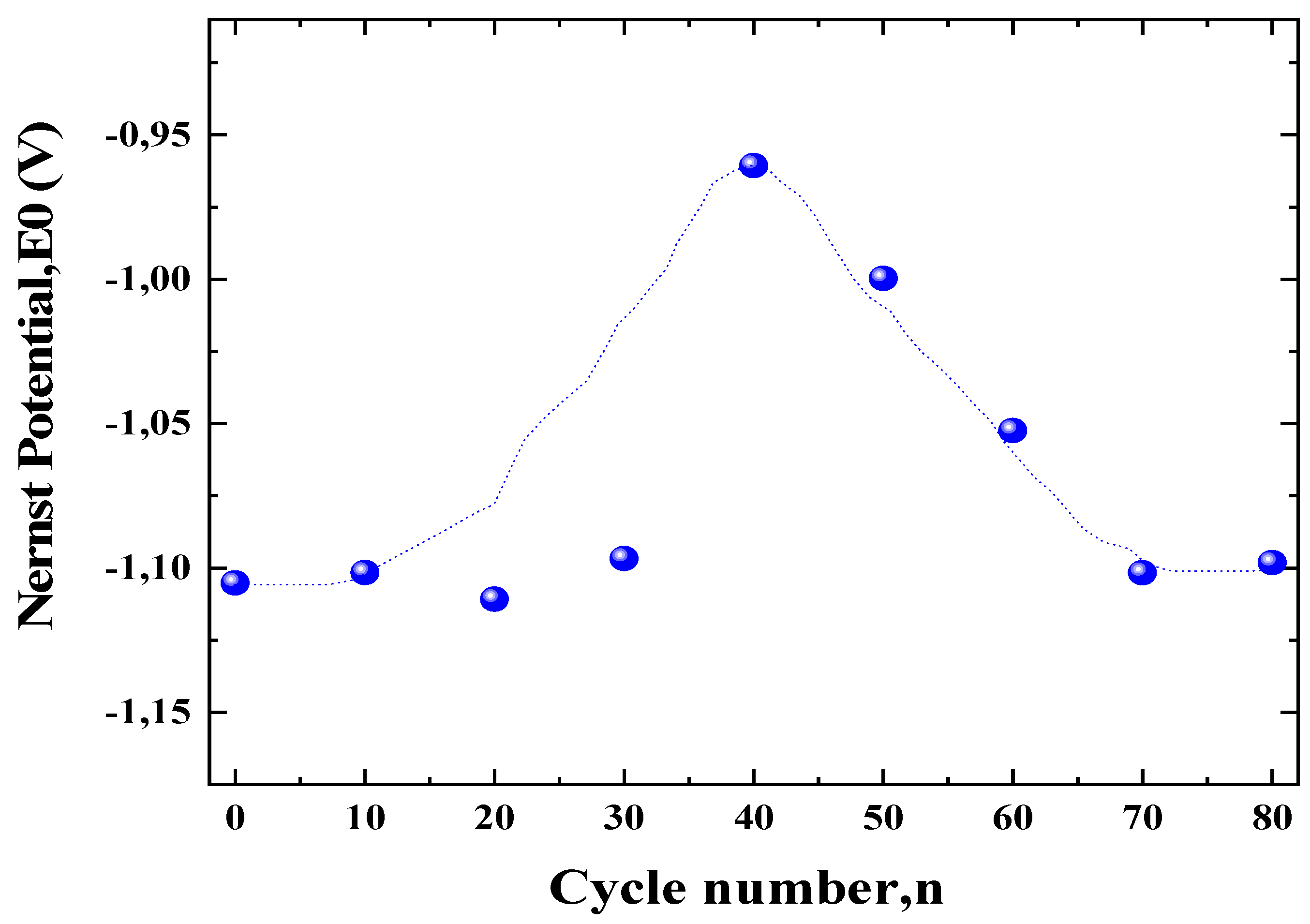

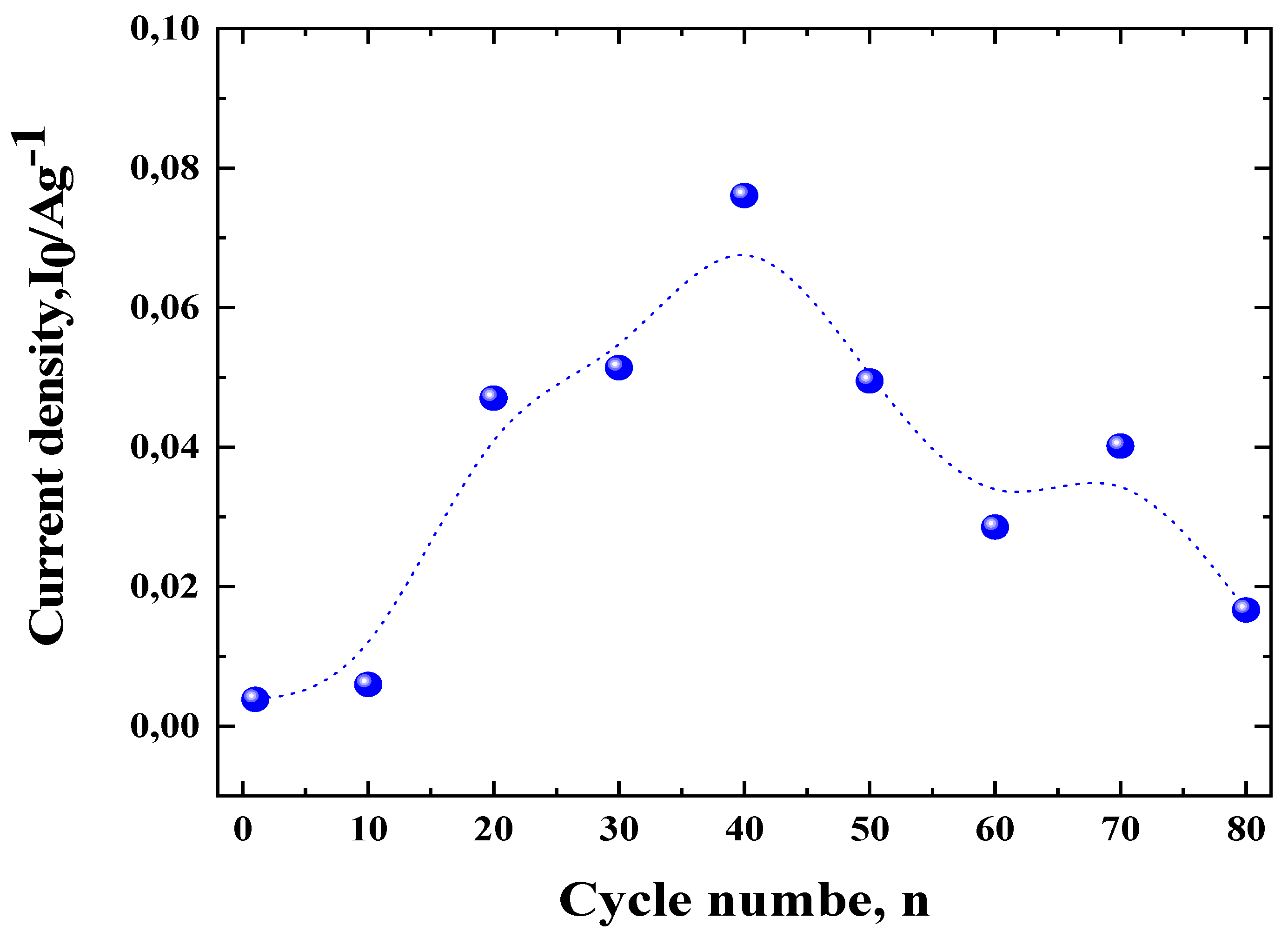

3.2.4. Kinetic Parameters of the ZnLaFeO4 Negative Electrode

3.2. Redox Properties of the Electrode ZnLaFeO4 Studied by Potentiodynamic Method

5. Conclusions

References

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.D.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy. strat. Reviews. 2019. 24, 38-50. [CrossRef]

- Campanari, S.; Manzolini, G.; De la Iglesia, F. G. Energy analysis of electric vehicles using batteries or fuel cells through well-to-wheel driving cycle simulations. J. Power Sou. 2009, 186(2) 464-477. [CrossRef]

- Smith,W.J. Can EV (electric vehicles) address Ireland’s CO2 emissions from transport? Energy. 2010. 35(12), 4514-4521. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Hu, X.; Zou, Y. ; Li, S. Adaptive unscented Kalman filtering for state of charge estimation of a lithium-ion battery for electric vehicles. Energy. 2011, 36(5), 3531-3540. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B.; Mårtensson, A. Energy and environmental costs for electric vehicles using CO2-neutral electricity in Sweden. Energy. 2000. 25(8), 777-792 . [CrossRef]

- Chau, K. T. ;.Wu, K. C. ; Chan, C. C. A new battery capacity indicator for lithium-ion battery powered electric vehicles using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. Energy. Conver.Manag. 2004. 45(11-12),1681-169 . [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Wang, S. A review of power battery thermal energy management. Renew. Sustai. Energy.Rev. 2011. 15(9),4554-4571. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Yan, F.; Zhang, P. ; Du, C. Comparison of comprehensive properties of Ni-MH (nickel-metal hydride) and Li-ion (lithium-ion) batteries in terms of energy efficiency. Energy. 2014, 70, 618-625. [CrossRef]

- Niu, H. ; Zhang, N. ; Lu, Y. ; Zhang, Z. ; Li, M. ; Liu, J.; Zhang, N.; Song, W.; Zhao Y.; Miao, Z. Strategies toward the development of high-energy-density lithium batteries. J. Energy Storage, 2024. 88, 111666 . [CrossRef]

- Fetcenko, M. A.; Ovshinsky, S. R.; Reichman, B.; Young, K.; Fierro, C.; Koch, J.;Zallen, A. ; Mays, W.; Ouchi, T. Recent advances in NiMH battery technology. J.Power Sou. 2007. 165(2), 544-551. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, W. ; Su, H. ; Lu, H. ; Li, Y.; Peng, Q.; Shumin H.; Zhang, L. Insights into the effect of Y substitution on superlattice structure and electrochemical performance of A5B19-type La-Mg-Ni-based hydrogen storage alloy for nickel metal hydride battery.J Mater Sci Technol.2025. 207, 60-69. [CrossRef]

- Salighe, Z.; Arabi, H.; Ghorbani, S.; Komeili, M. Microstructural, hydrogenation and electrochemical properties of La2Mg1-xYxNi10Mn0. 5 (x= 0.1, 0.38) alloys for Ni-MH battery anode. J. Solid State Chem. 2025. 348, 125340. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. ; Bian, Z. ; Liu, X. ; Lan, X. ; Liu, J. ; Ma, Z. ; Zhang, H. ; Luo, Y. Effects of thickness and gas hydrogenation on the electrochemical performances of a-Si thin film as anode for Ni-MH battery. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024. 82, 959-967. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Sheng, P.; Zhang, X.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Cao, Z., Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y. Metal Hydride Electrodes Applied to Ni-MH Battery Using Mg-Y-Ni-Cu-Based Alloys. Energy Technology. 2025. 2402252. [CrossRef]

- Marins, A. A.; Boasquevisque, L. M.; Muri, E. J.; Freitas, M. B. Enviromentally friendly recycling of spent Ni–MH battery anodes and electrochemical characterization of nickel and rare earth oxides obtained by sol–gel synthesis. Mater. Chemi. Phys. 2022. 280, 125821. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. H.; Wei, X.; Gao, J. L.; Hu, F.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, D. L. Electrochemical hydrogen storage behaviors of as-milled Mg–Ti–Ni–Co–Al-based alloys applied to Ni-MH battery. Electro .Acta. 2020. 342, 136123 . [CrossRef]

- Kalita, G.; Otsuka, R.; Endo, T.; Furukawa, S. Recent advances in substitutional doping of AB5 and AB2 type hydrogen storage metal alloys for Ni-MH battery applications. J Alloys Compd. 2025.179352. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M. Progress of hydrogen storage alloys for Ni-MH rechargeable power batteries in electric vehicles: A review. Mater. Chem.Phy. 2017.200, 164-178. [CrossRef]

- Joubert, J. M. ; Paul-Boncour, V.; Cuevas, F.; Zhang, J. ; Latroche, M. LaNi5 related AB5 compounds: Structure, properties and applications. J.Alloys. Comp. 2021. 862, 158163. [CrossRef]

- Gamo, T.; Moriwaki, Y.; Yanagihara, Yamashita, T.; Iwaki, T. Formation and properties of titanium-manganese alloy hydrides. Int.J.Hydr. Ener. 1985. 10(1), 39-47. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Takeshita, H. T. ; Tanaka, H.; Kuriyama, N. ; Sakai, T.; Uehara, I.; Haruta, M. Hydriding properties of LaNi3 and CaNi3 and their substitutes with PuNi3-type structure. J.Alloys . Comp. 2000. 302(1-2), 304-313. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, F.; Joubert, J. M.; Latroche, M.; Percheron-Guegan, A. Intermetallic compounds as negative electrodes of Ni/MH batteries. App. Phys. A. 2001. 72, 225-238.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s003390100775#citeas.

- Arya, S.; Verma, S. Nickel-metal hydride (Ni-MH) batteries. Rechar. Batteries: Histo. Prog. Appli. 2020. 131-175 . [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Ren, K.; Liang, J.; Kong, J. A novel sheet perovskite type oxides LaFeO3 anode for nickel-metal hydride batteries. J Mater Sci Technol. 2024. 195, 218-226. [CrossRef]

- Esaka, T.; Sakaguchi, H.; Kobayashi, S. Hydrogen storage in proton-conductive perovskite-type oxides and their application to nickel–hydrogen batteries. Solid .State Ioni. 2004. 166(3-4), 351-357. [CrossRef]

- Stoumpos, C. C.; Kanatzidis, M. G. Halide Perovskites: poor Man's high-performance semiconductors. Adv. Mater .2016.28(28), 5778-5793. [CrossRef]

- M.Bini, M.Ambrosetti , D.Spada, ZnFe2O4, a green and high-capacity anode material for lithium-ion batteries: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021. 11(24), 11713. [CrossRef]

- Brabers, V. A. M. Progress in spinel ferrite research. Hand.mag.mater. 1995. 8, 189-324. [CrossRef]

- Narang, S. B. ; Pubby, K. Nickel spinel ferrites: a review. J. Mag. Mag. Mater. 2021. 519, 167163. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, D.; Latwal, M.; Singh, J.P.; K.Gupta, L.; Srivastava, R .C. 9 - Zinc ferrite nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. Woodhead Publishing .Ox .Med.Appl. 2023. 233-255. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, R. Novel applications of ferrites. Phys.Resea. Int . 2012(1), 591839 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R. S.; Kuřitka, I.; Vilcakova, J.; Urbánek, P.; Machovsky, M.; Masař, M.; Holek, M. Structural, magnetic, optical, dielectric, electrical and modulus spectroscopic characteristics of ZnFe2O4 spinel ferrite nanoparticles synthesized via honey-mediated sol-gel combustion method. J.Phys.Chem.Solids. 2017.110, 87-99. [CrossRef]

- Baykal, A.; Kasapoğlu, N.; Durmuş, Z.; Kavas, H.; Toprak, M. S.; Köseoğlu, Y. CTAB-Assisted Hydrothermal Synthesis and Magnetic Characterization of NixCo{1-x} Fe2O4 Nanoparticles (x= 0.0, 0.6, 1.0). Turkish. J. chem. 2009.33(1), 33-45. [CrossRef]

- Selvan, R. K. ; Krishnan, V.; Augustin, C. O.; Bertagnolli, H.; Kim, C. S.; Gedanken, A.Investigations on the structural, morphological, electrical, and magnetic properties of CuFe2O4− NiO nanocomposites. Chem. Mater. 2008. 20(2), 429-439. [CrossRef]

- Kefeni, K. K.; Mamba, B. B.; Msagati, T. A. Application of spinel ferrite nanoparticles in water and wastewater treatment: a review. Sepa. Pur. Tech. 2017.188, 399-422. [CrossRef]

- Šutka, A.; Gross, K. A. Spinel ferrite oxide semiconductor gas sensors. Sens. actuators B: chem. 2016.222, 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Lima-Tenório, M. K. ; Tenório-Neto, E. T.; Hechenleitner, A. A. W.; Fessi, H.; Pineda, E. A. G. CoFe2O4 and ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles: an overview about structure, properties, synthesis and biomedical applications. J. Coll. Sci. 2016. Biotech.5(1), 45-54. [CrossRef]

- Amini, M. M.; Yadavi, M. Influence of metal core of mixed-metal carboxylates in preparation of spinel: ZnFe2O (O2CCF3) 6 as a single-source precursor for preparation of ZnFe2O4. Appl. Organo. Chem.2005. 19(11), 1164-1167. [CrossRef]

- Kalendova, A.; Veselý, D.; Brodinova, J. Anticorrosive spinel-type pigments of the mixed metal oxides compared to metal polyphosphates. Anti-Corr. Meth. Mater. 2004. 51(1), 6-17. [CrossRef]

- Dhineshbabu, N. R.; Vettumperumal, R.; Narendrakumar, A.; Manimala, M. ; Kanna, R. R. ; Optical properties of lanthanum-doped copper spinel ferrites nanoparticles for optoelectronic applications. Adv. Sci. Enginee. Med.2017. 9(5), 377-383. [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, M.; Khan, R. U.; Mumtaz, M.; Soomro, S. A.; Ullah, S. NiFe2O4 nanoparticles/MWCNTs nanohybrid as anode material for lithium-ion battery. Cer.Int.2019. 45(7), 8486-8493. [CrossRef]

- Lavela, P. ; Tirado, J. L. CoFe2O4 and NiFe2O4 synthesized by sol–gel procedures for their use as anode materials for Li ion batteries. J. Pow. Sou. 2007. 172(1), 379-387. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. R.; H.Jung, Y.; Bharathi, K. K.; Lim, C. H. ; Kim, D. K. High capacity and low cost spinel Fe3O4 for the Na-ion battery negative electrode materials. Elect. Acta. 2014.146, 503-510. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, S. D.; Joy, P. A.; Anantharaman, M. R. Effect of mechanical milling on the structural, magnetic and dielectric properties of coprecipitated ultrafine zinc ferrite. J.Mag. Mag. Mater. 2004. 269(2), 217-226 . [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Zeng, Q.; Goya, G. F.; Torres, T.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Ge, M.; Zeng, Y.;Wang, Y. ; Jiang, J. Z. ZnFe2O4 nanocrystals: synthesis and magnetic properties. J. Phy. Chem. 2007.111(33), 12274-12278. [CrossRef]

- Rameshbabu, R.; Ramesh, R.; Kanagesan, S.; Karthigeyan, A.; Ponnusamy, S. Synthesis and study of structural, morphological and magnetic properties of ZnFe 2 O 4 nanoparticles. J. Super. Novel Mag. 2014. 27, 1499-1502. [CrossRef]

- Haija, M. A.; Abu-Hani, A. F. ; Hamdan, N.; Stephen, S.; Ayesh, A. I. Characterization of H2S gas sensor based on CuFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Alloys. Comp. 2017. 690, 461-8. [CrossRef]

- Soussi, A.; Haounati, R.; Taoufiq, M.; Baoubih, S.; Jellil, Z.; Elfanaoui, A.; Ihlal, A. Investigating structural, morphological, electronic, and optical properties of SnO2 and Al-doped SnO2: A combined DFT calculation and experimental study. Physica B: Condens. Matter. 2024. 690, 416242. [CrossRef]

- Renuka, L.; Anantharaju, K. S.; Sharma, S. C.; Vidya, Y. S.; Nagaswarupa, H. P.; Prashantha, S. C. ; Nagabhushana, H. Synthesis of ZnFe2O4 nanoparticle by combustion and sol gel methods and their structural, photoluminescence and photocatalytic performance. Mater. Today: Procee. 2018. 5(10), 20819-20826. [CrossRef]

- Zayani, W.; Azizi, S.; El-Nasser, K. S.; Othman Ali, I.; Molière,M.; Fenineche, N. ; Mathlouthi, H.; Lamloumi, J. Electrochemical behavior of a spinel zinc ferrite alloy obtained by a simple sol-gel route for Ni-MH battery applications. Int. J. Ener.Resea. 2021.45(4), 5235-5247. [CrossRef]

- Zayani, W., Azizi, S., El-Nasser, K. S., Belgacem, Y. B., Ali, I. O., Fenineche, N., Mathlouthi, H. New nanoparticles of (Sm, Zn)-codoped spinel ferrite as negative electrode in Ni/MH batteries with long-term and enhanced electrochemical performance. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2019. 44(22), 11303-11310. [CrossRef]

- Epp, J. X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques for materials characterization. Woodhead Publishing. Mater. Chara.using nondes. Evalua. (NDE) Meth. 2016. 81-124. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. W.; Elkedim, O.; Moutarlier, V. Synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline Mg2Ni prepared by mechanical alloying: Effects of substitution of Mn for Ni. J. Alloys. Comp. 2010. 504, S311-S314. [CrossRef]

- Karaoud, I.; Dabaki, Y.; Khaldi, C.; ElKedim, O.; Fenineche, N.; Lamloumi, J. Electrochemical properties of the CaNi4. 8M0. 2 (M= Mg, Zn, and Mn) mechanical milling alloys used as anode materials in nickel-metal hydride batteries. Environ. Prog. Sus. Energy. 2023. 42(5), e14118 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, V.; Shirsath, S. E.; Mane, M. L.; Kadam, R. H.; Shelke, S. B.; Mane, D. R. Crystallographic, magnetic and electrical properties of Ni0. 5Cu0. 25Zn0. 25LaxFe2− xO4 nanoparticles fabricated by sol–gel method. J. Alloys. Comp. 2013. 549, 213-220. [CrossRef]

- Al Angari, Y. M. Magnetic properties of La-substituted NiFe2O4 via egg-white precursor route. J. Mag. Mag. Mater. 2011.323(14), 1835-1839. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.; Rehman, A. U.; Amin, N.; un Nabi, M. A.; ul ain Abdullah , Q.; Morley, N. A.; Mehmood, K. Lanthanum doped Zn0. 5Co0. 5LaxFe2− xO4 spinel ferrites synthesized via co-precipitation route to evaluate structural, vibrational, electrical, optical, dielectric, and thermoelectric properties. J. Phy. Chem. Solids. 2021. 154, 110080. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, F.; Li, L. ; Liu, H.; Qiu, H.; Jiang, J. Magnetic properties of La-substituted Ni–Zn–Cr ferrites via rheological phase synthesis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008. 112(3), 769-773. [CrossRef]

- Ganure, K. A.; Dhale, L. A.; Katkar, V. T.; Lohar, K. S. Synthesis and characterization of lanthanum-doped Ni-Co-Zn spinel ferrites nanoparticles via normal micro-emulsion method. Int. J. Nanotechnol. Appl. 2017. 11(2), 189-195.

- Li, X. D., Elkedim, O., Nowak, M., Jurczyk, M., & Chassagnon, R. Structural characterization and electrochemical hydrogen storage properties of Ti2− xZrxNi (x= 0, 0.1, 0.2) alloys prepared by mechanical alloying. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2013. 38(27), 12126-12132. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. H.; Srinivasan, V.; Wang, C. Y. An experimental and modeling study of isothermal charge/discharge behavior of commercial Ni–MH cells. J. Power. Sour. 2002. 112(1), 298-306 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Dymek, M.; Nowak, M.; Jurczyk, M.; Bala, H. Encapsulation of La1. 5Mg0. 5Ni7 nanocrystalline hydrogen storage alloy with Ni coatings and its electrochemical characterization. J.Alloys.Comp. 2018.749,534-542. [CrossRef]

- Bala, H.; Dymek, M. Corrosion degradation of powder composite hydride electrodes in conditions of long-lasting cycling. Mater. Chem. Phys.167, 265-270 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Bala, H. ; Giza, K. ; Kukula, I. Determination of hydrogenation ability and exchange current of H 2 O/H 2 system on hydrogen-absorbing metal alloys. J. App. Elec. 2010. 40, 791-797(2010). [CrossRef]

- Bala, H.; Dymek, M. ; Adamczyk, L. ; Giza, K.; Drulis, H. Hydrogen diffusivity, kinetics of H 2 O/H 2 charge transfer and corrosion properties of LaNi 5-powder, composite electrodes in 6 M KOH solution. J. Solid.State Electr. 2014. 18, 3039-3048. [CrossRef]

- Bala, H.; Kukuła, I.; Giza, K.; Marciniak, B.; Różycka-Sokołowska, E.; Drulis, H. Evaluation of electrochemical hydrogenation and corrosion behavior of LaNi5-based materials using galvanostatic charge/discharge measurements. Int. J. Hydro. Energy. 2012. 37(22), 16817-16822. [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Miao, J.; Shen, W.; Su, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Han, S. High temperature electrochemical.

| Sample | Phases found | Lattice parameters (Å) | Abundance of Phase (wt%) |

Crystallite size Ds(nm) |

Crystallie size DW-H(nm) |

Sig | Fit parameters |

| ZnLaFeO4 | LaFeO3 | a= 5.562 b= 7.841 c= 5.549 |

54.88 | 36.45 |

54.32 |

1.8 |

Rwp = 6.11; Rb = 5.77 Rexp=5.36 |

| La2O3 | a= 3.956 c= 6.137 |

33.23 | |||||

| ZnFe2O4 | a= 8.439 | 11.89 |

| Material | Nmax |

Qdisch,max (mAh/g) |

Qdich80 (mAh/g) |

R80 (%) |

K (cycle -1) |

CM (g.cm-3) |

rcorr (g.cm-3.cycle -1 |

|

| ZnLaFeO4 | 46 | 106 | 74 | 69.81 | -0.00495 | 0.01140 | 2.028 | 0.02311 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).