Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

30 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Characterization of Cathode Material

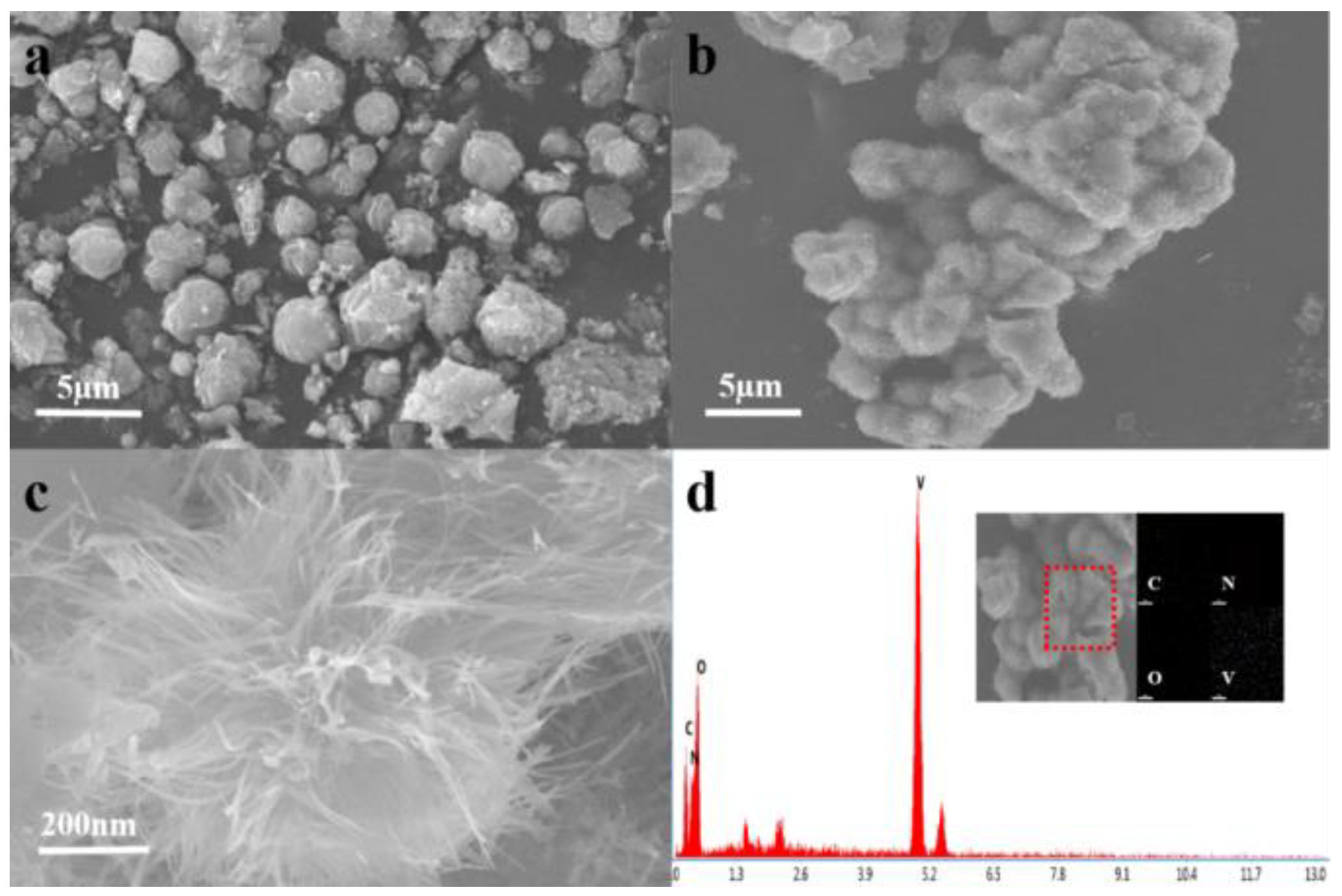

2.2.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS)

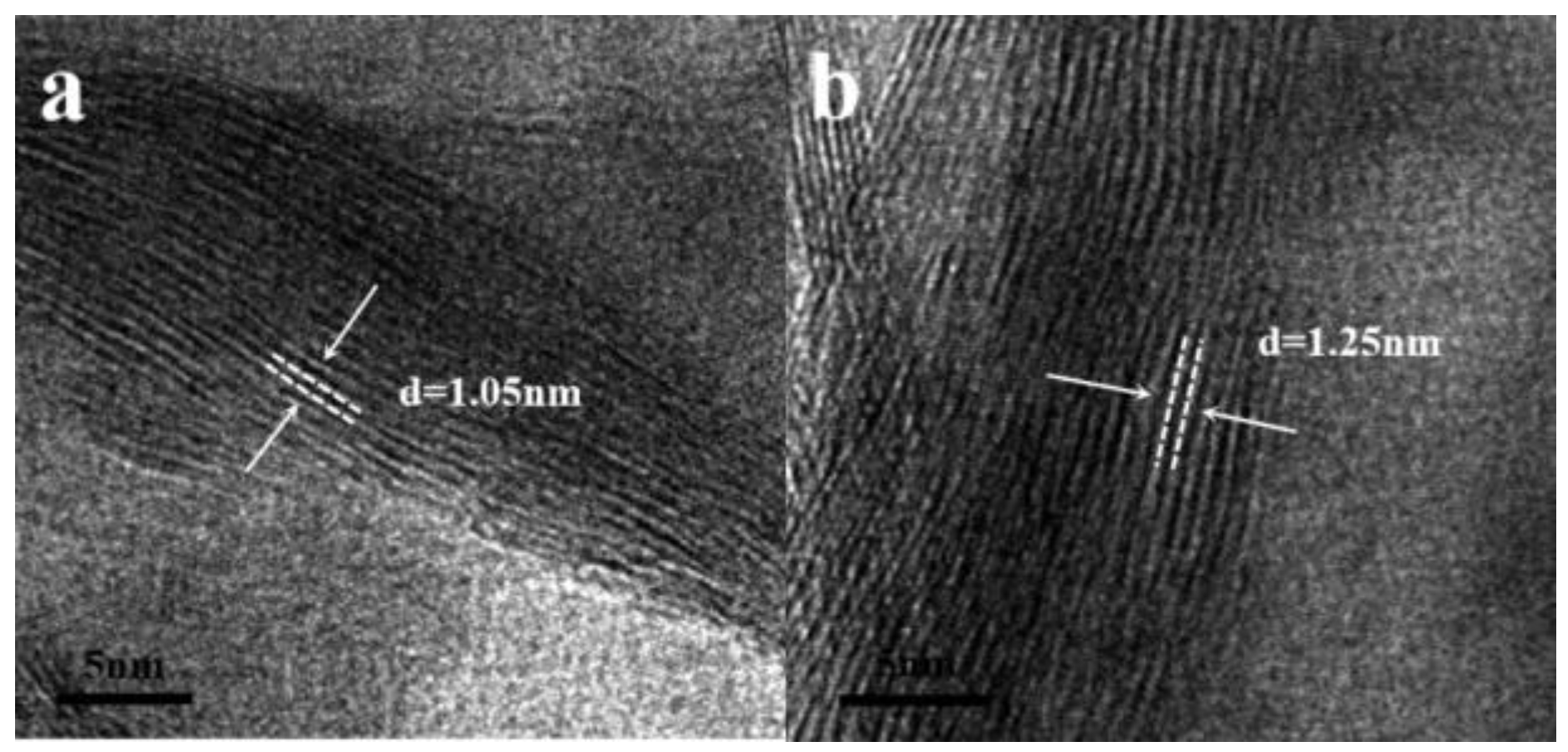

2.2.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

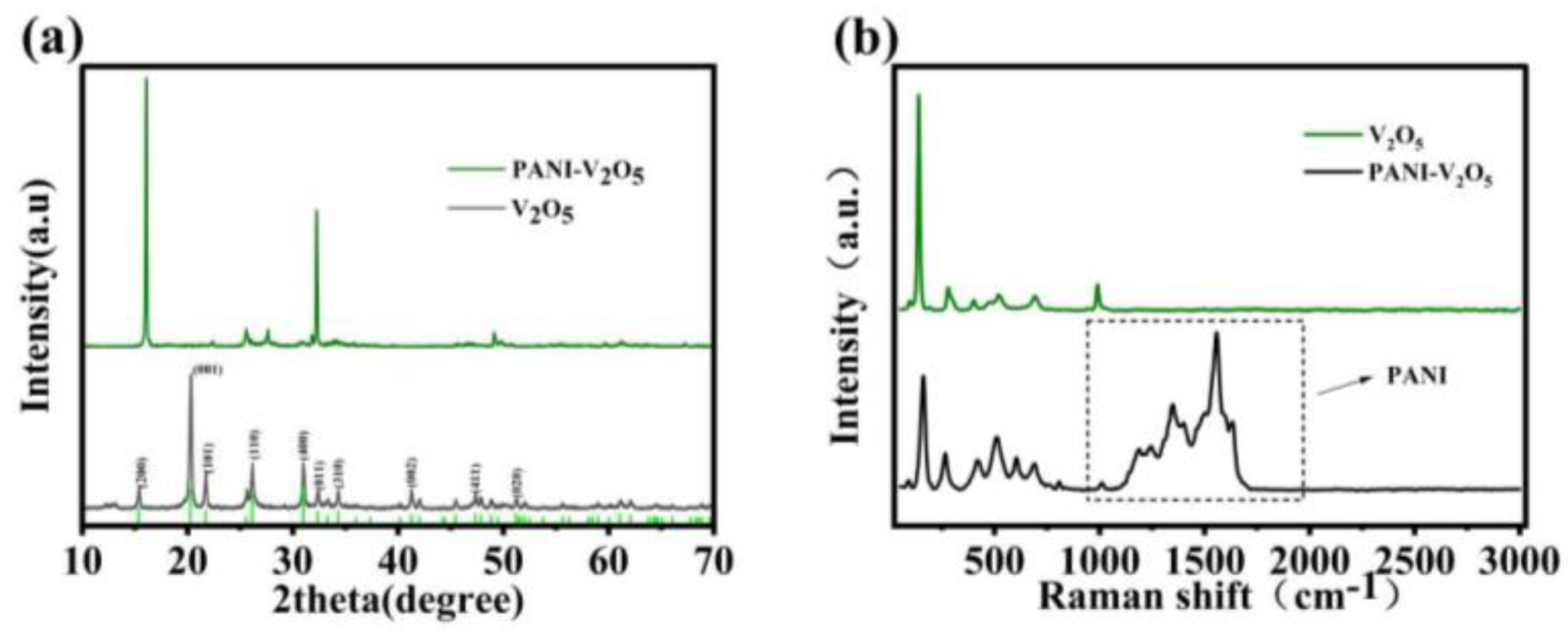

2.2.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) and Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

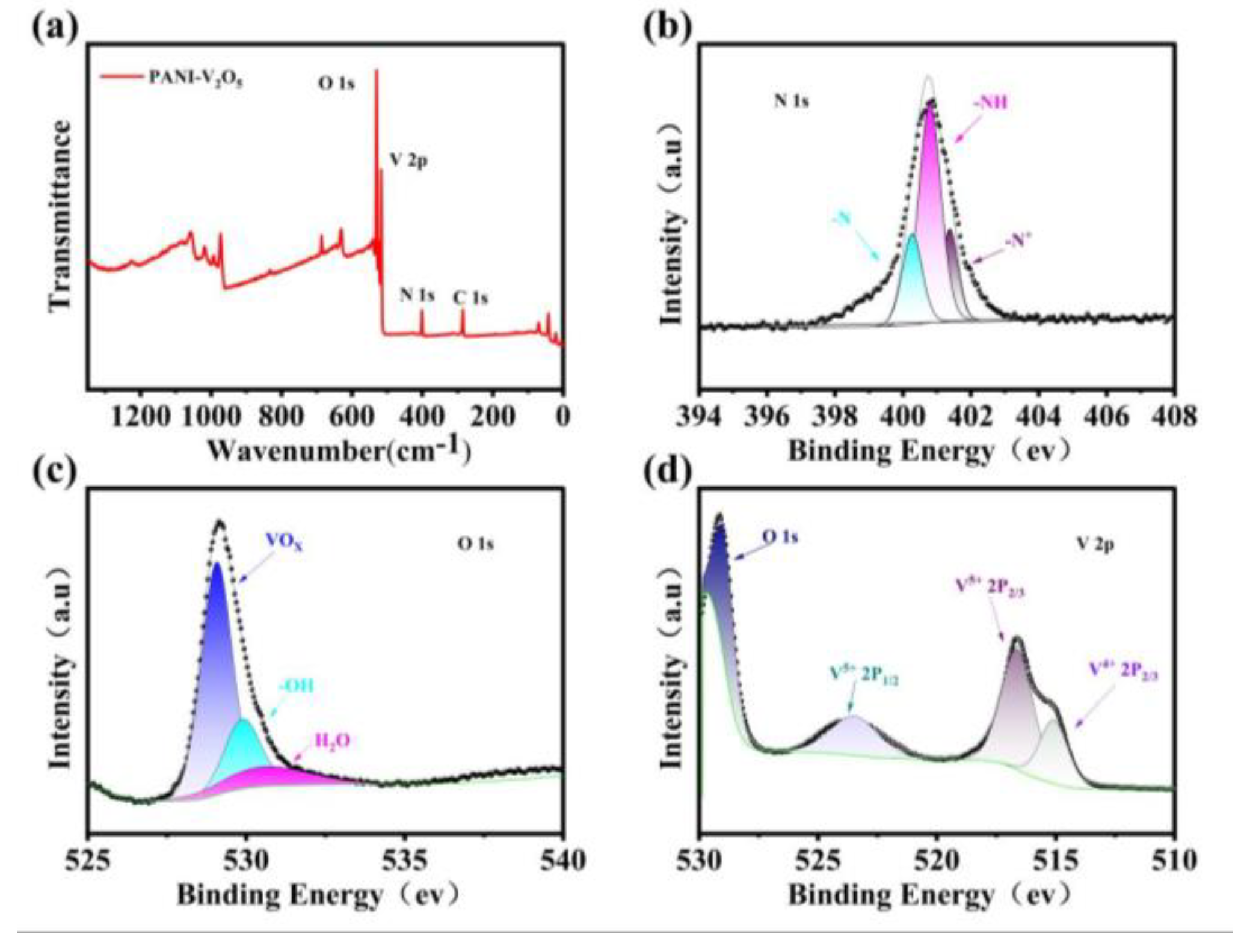

2.2.4. AnalysisX-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

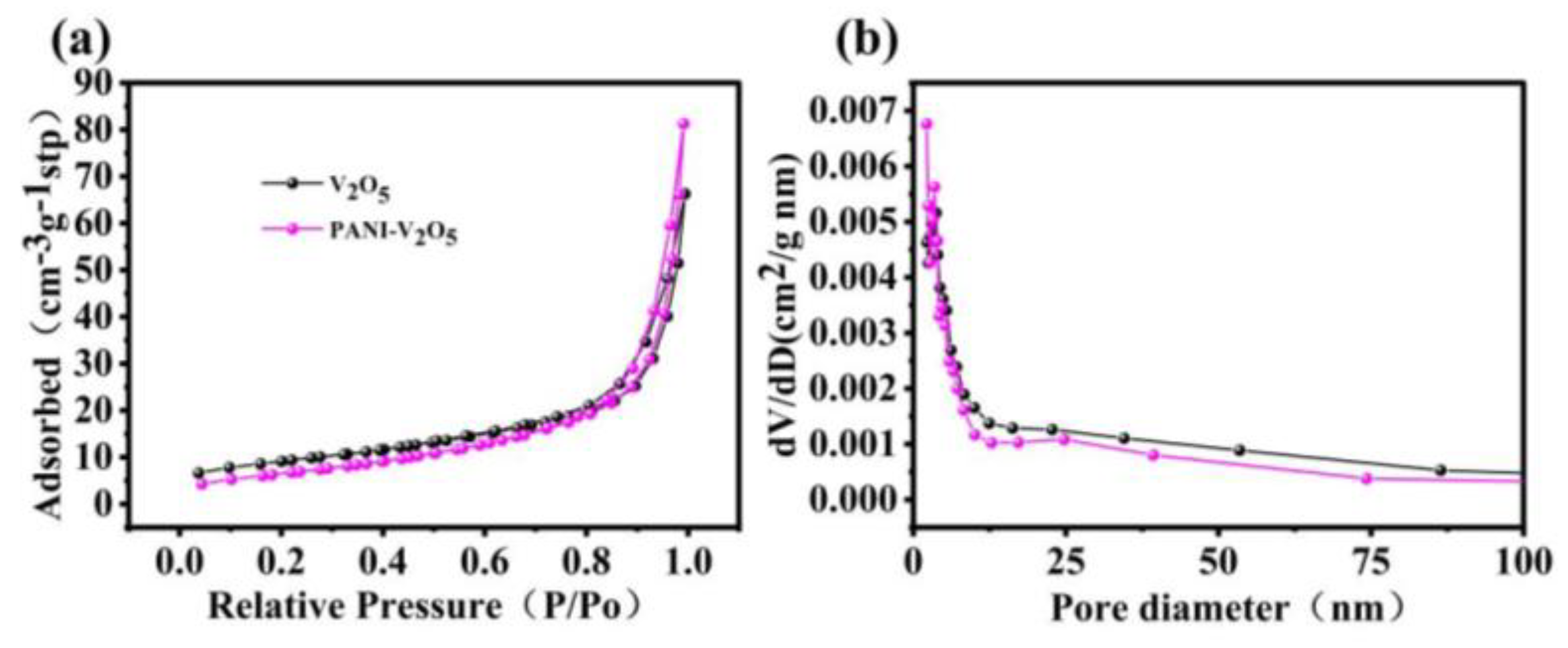

2.2.5. Nitrogen Adsorption-Desorption Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

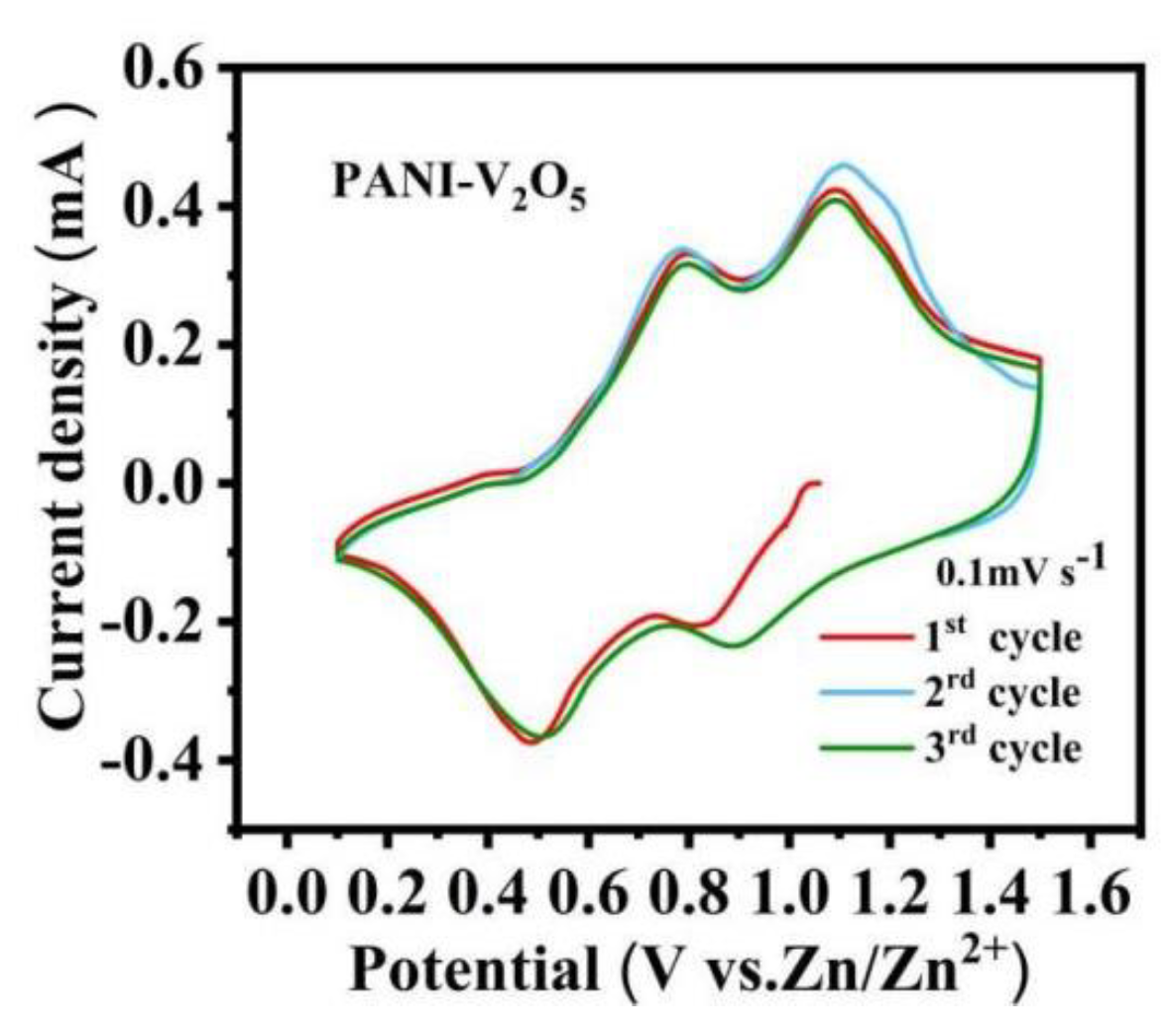

3.1. Cyclic Voltammetry Tests

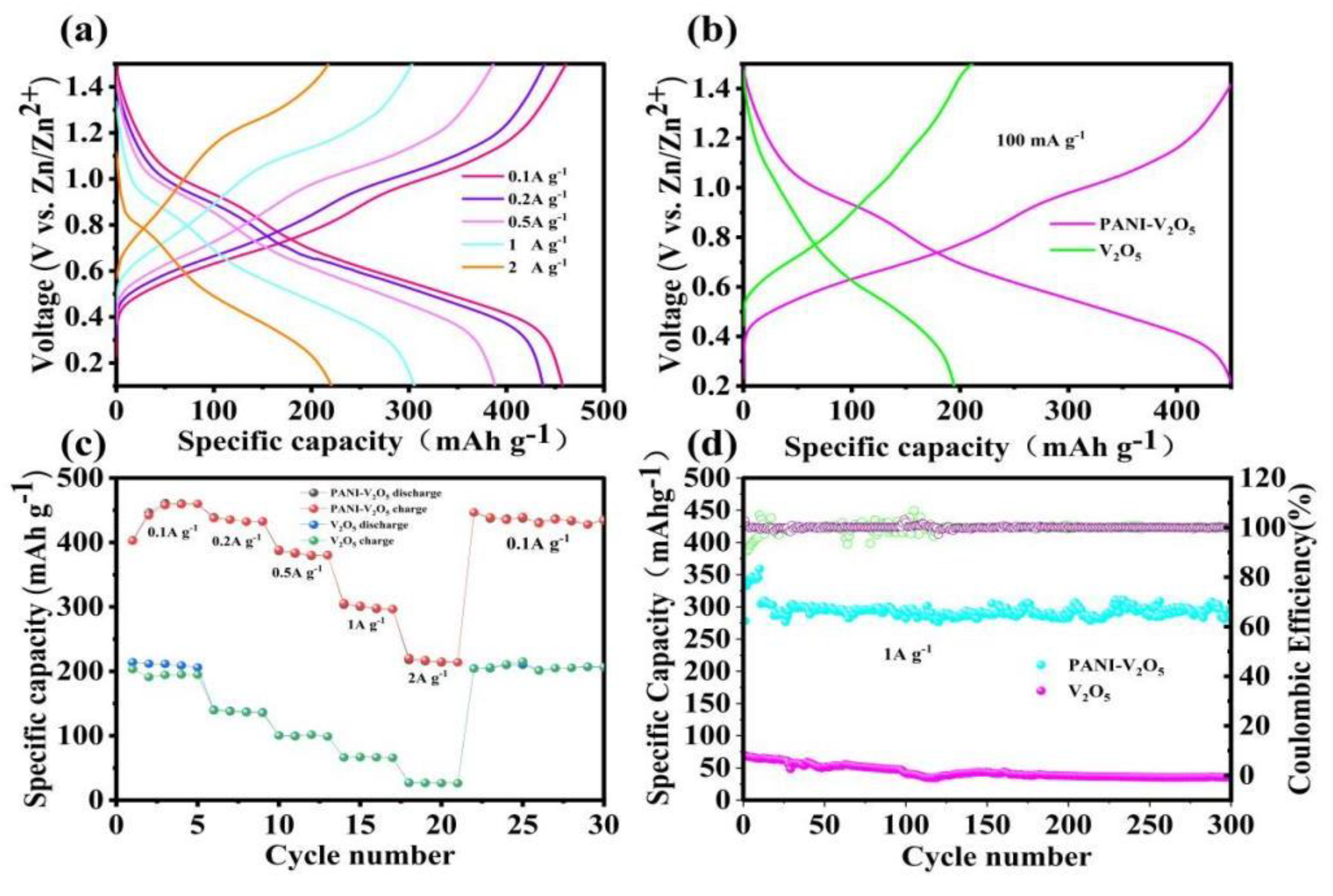

3.2. Constant Current Charge-Discharge and Cycling Rate Performance Tests

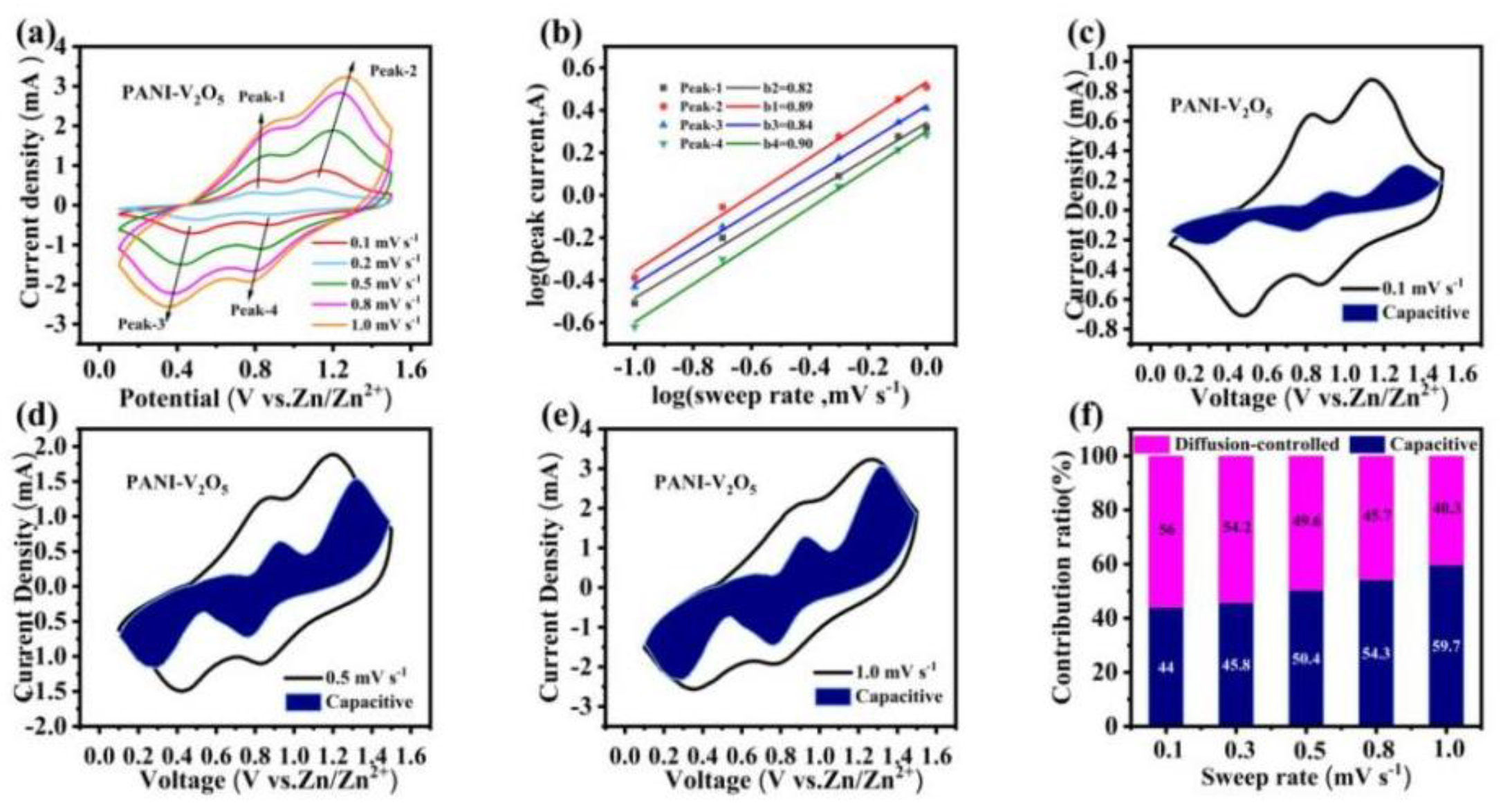

3.3. Electrochemical Kinetics Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu A, Chen W, Li F, et al. Nonflammable Polyfluorides-Anchored Quasi-Solid Electrolytes for Ultra-safe Anode-free Lithium Pouch Cells without Thermal Runaway [J]. Advanced Materials, 2023, 35(51): 2304762. [CrossRef]

- Yang B, Pan Y, Li T, et al. High-safety lithium Metal Pouch Cells for Extreme Abuse Conditions by Implementing Flame-Retardant Perfluorinated Gel Polymer Electrolytes [J]. Energy Storage Materials, 2024, 65: 103124. [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Yan Z, Zhou B, et al. Identifying the Role of Lewis-Base Sites for The Chemistry in Lithium-Oxygen Batteries [J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2023, 62(32): 202302746. [CrossRef]

- Fang C, Li J, Zhang M, et al. Quantifying Inactive Lithium in Lithium Metal Batteries [J]. Nature, 2019, 572(7770): 511-515. [CrossRef]

- Wang P-F, Sui B-B, Sha L, et al. Nitrogen-rich Graphite Flake from Hemp as Anode Material for High Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries [J]. Chemistry – An Asian Journal, 2023, 18(13): 202300279. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Gong Z, Wang D, et al. Facile Fabrication of F-doped Biomass Carbon as High-Performance Anode Material for Potassium-ion Batteries [J]. Electrochimica Acta, 2021, 389: 138799. [CrossRef]

- Quilty C D, Wu D, Li W, et al. Electron and Ion Transport in Lithium and Lithium-Ion Battery Negative and Positive Composite Electrodes [J]. Chemical Reviews, 2023, 123(4): 1327-1363. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Ge M, Ma F, et al. Multifunctional Electrolyte Additives for Better Metal Batteries [J]. Advanced Functional Materials, 2024, 34(5): 2301964. [CrossRef]

- Yi X, Feng Y, Rao A M, et al. Quasi-Solid Aqueous Electrolytes for Low-Cost Sustainable Alkali-metal Batteries [J]. Advanced Materials, 2023, 35(29): 2302280. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Rao A M, Zhou J, et al. Selective Potassium Deposition Enables Dendrite-resistant Anodes for Ultrastable Potassium-Metal Batteries [J]. Advanced Materials, 2023, 35(30): 2300886. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Sun J, Hua Y, et al. Planar and Dendrite-Free Zinc Deposition Enabled by Exposed Crystal Plane Optimization of Zinc Anode [J]. Energy Storage Materials, 2022, 53: 273-304. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Sun W, Wang Y. Covalent Organic Frameworks for Next-Generation Batteries [J]. ChemElectroChem, 2020, 7(19): 3905-3926. [CrossRef]

- Shuai H, Xu J, Huang K. Progress in Retrospect of Electrolytes for Secondary Magnesium Batteries [J]. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2020, 422: 213478. [CrossRef]

- Meng Z, Foix D, Brun N, et al. Alloys to Replace Mg Anodes in Efficient and Practical Mg-Ion/SulfurBatteries [J]. ACS Energy Letters, 2019, 4(9): 2040-2044. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Dong D, Caro A L, et al. Aqueous Electrolytes Reinforced by Mg and Ca Ions for Highly Reversible Fe Metal Batteries [J]. ACS Central Science, 2022, 8(6): 729-740. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Firby C J, Elezzabi A Y. Rechargeable Aqueous Hybrid Zn2+/Al3+ Electrochromic Batteries [J]. Joule, 2019, 3(9): 2268-2278. [CrossRef]

- Yi Z, Chen G, Hou F, et al. Strategies for The Stabilization of Zn Metal Anodes for Zn-Ion Batteries [J]. Advanced Energy Materials, 2021, 11(1): 2003065. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Y, Ren J, Li M, et al. Charge-Tuning Mediated Rapid Kinetics of Zinc Ions in Aqueous Zn-Ion Battery [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023, 474: 145801. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Li Y, Xie R, et al. Structural Engineering of Cathodes for Improved Zn-Ion Batteries [J]. Journal of Energy Chemistry, 2021, 58: 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, An Y, Liu C, et al. Reversible Zinc-Based Anodes Enabled by Zincophilic Antimony Engineered Mxene for Stable and Dendrite-Free Aqueous Zinc Batteries [J]. Energy Storage Materials, 2021, 41: 343-353. [CrossRef]

- Fu X, Li G, Wang X, et al. The Etching Strategy of Zinc Anode to Enable high Performance Zinc-Ion Batteries [J]. Journal of Energy Chemistry, 2024, 88: 125-143. [CrossRef]

- Blanc L E, Kundu D, Nazar L F. Scientific Challenges for the Implementation of Zn-Ion Batteries [J]. Joule, 2020, 4(4): 771-799. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Wei X, Wu C, et al. Constructing Three-Dimensional Structured V2O5/Conductive Polymer Composite with Fast Ion/Electron Transfer Kinetics for Aqueous Zinc-Ion Battery [J]. ACS Applied Energy Materials, 2021, 4(4): 4208-4216. [CrossRef]

- Shao Y, Zeng J, Li J, et al. Sandwich Structure of 3D Porous Carbon and Water-Pillared V2O5 Nanosheets for Superior Zinc-Ion Storage Properties [J]. ChemElectroChem, 2021, 8(10): 1784-1791. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Tang Y, Liang S, et al. Transition metal Ion-Preintercalated V2O5 as High-performance Aqueous Zinc-Ion Battery Cathode with Broad Temperature Adaptability [J]. Nano Energy, 2019, 61: 617-625. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Wang Z, Ben H, et al. Boosting the Zinc ion Storage Capacity and Cycling Stability of Interlayer-Expanded Vanadium Disulfide Through In-Situ Electrochemical Oxidation Strategy [J]. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2022, 607: 68-75. [CrossRef]

- Javed M S, Lei H, Wang Z, et al. 2D V2O5 Nanosheets as a Binder-free High-Energy Cathode for Ultrafast Aqueous and Flexible Zn-Ion Batteries [J]. Nano Energy, 2020, 70: 104573. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Wen Y, Huang F, et al. Rational Design and Demonstration of a High-Performance Flexible Zn/V2O5 Battery with Thin-Film Electrodes and Para-Polybenzimidazole Electrolyte Membrane [J]. Energy Storage Materials, 2020, 27: 418-425. [CrossRef]

- Wan F, Zhang L, Dai X, et al. Aqueous Rechargeable Zinc/Sodium Vanadate Batteries with Enhanced Performance from Simultaneous Insertion of Dual Carriers [J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 520-529. [CrossRef]

- Lv T-T, Liu Y-Y, Wang H, et al. Crystal Water Enlarging the Interlayer Spacing of Ultrathin V2O5·4VO2·2.72H2O Nanobelts for High-Performance Aqueous Zinc-Ion Battery [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 411: 128533. [CrossRef]

- Zhou S, Wu X, Du H, et al. Dual Metal Ions and Water Molecular Pre-Intercalated δ-MnO2 Spherical Microflowers for Aqueous Zinc Ion Batteries [J]. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2022, 623: 456-466. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Xing F, Li T, et al. Intercalated Polyaniline in V2O5 as a Unique Vanadium Oxide Bronze Cathode for Highly Stable Aqueous Zinc Ion Battery [J]. Energy Storage Materials, 2021, 38: 590-598. [CrossRef]

- Yin C, Pan C, Liao X, et al. Regulating the Interlayer Spacing of Vanadium Oxide by In Situ Polyaniline Intercalation Enables an Improved Aqueous Zinc-Ion Storage Performance [J]. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2021, 13(33): 39347-39354. [CrossRef]

- Du Y, Xu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Metal-Organic-Framework-Derived Cobalt-Vanadium Oxides with Tunable Compositions for High-Performance Aqueous Zinc-Ion Batteries [J]. Chemical Engineering , 2023, 457: 141162. [CrossRef]

- Yang B, Tamirat A G, Bin D, et al. Regulating Intercalation of Layered Compounds for Electrochemical Energy Storage and Electrocatalysis [J]. Advanced Functional Materials, 2021, 31(52): 2104543. [CrossRef]

- Liu N, Wu X, Fan L, et al. Intercalation Pseudocapacitive Zn2+ Storage with Hydrated Vanadium Dioxide toward Ultrahigh Rate Performance [J]. Advanced Materials, 2020, 32(42): 1908420. [CrossRef]

- Tang H, Peng Z, Wu L, et al. Vanadium-Based Cathode Materials for Rechargeable Multivalent Batteries: Challenges and Opportunities [J]. Electrochemical Energy Reviews, 2018, 1(2): 169-199. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Sun W, Shadike Z, et al. How Water Accelerates Bivalent Ion Diffusion at the Electrolyte/Electrode Interface [J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2018, 57(37): 11978-11981. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Han C, Gu Q, et al. Electron Delocalization and Dissolution-Restraint in Vanadium Oxide Superlattices to Boost Electrochemical Performance of Aqueous Zinc-Ion Batteries [J]. Advanced Energy Materials, 2020, 10(48): 2001852. [CrossRef]

- Kumankuma-Sarpong J, Guo W, Fu Y. Yttrium Vanadium Oxide–Poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) Composite Cathode Material for Aqueous Zinc-Ion Batteries [J]. Small Methods, 2021, 5(9): 2100544. [CrossRef]

- Zhang K, Hu Z, Liu X, et al. FeSe2 Microspheres as a High-Performance Anode Material for Na-Ion Batteries [J]. Advanced Materials, 2015, 27(21): 3305-3309. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).