Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Approach and Timeline

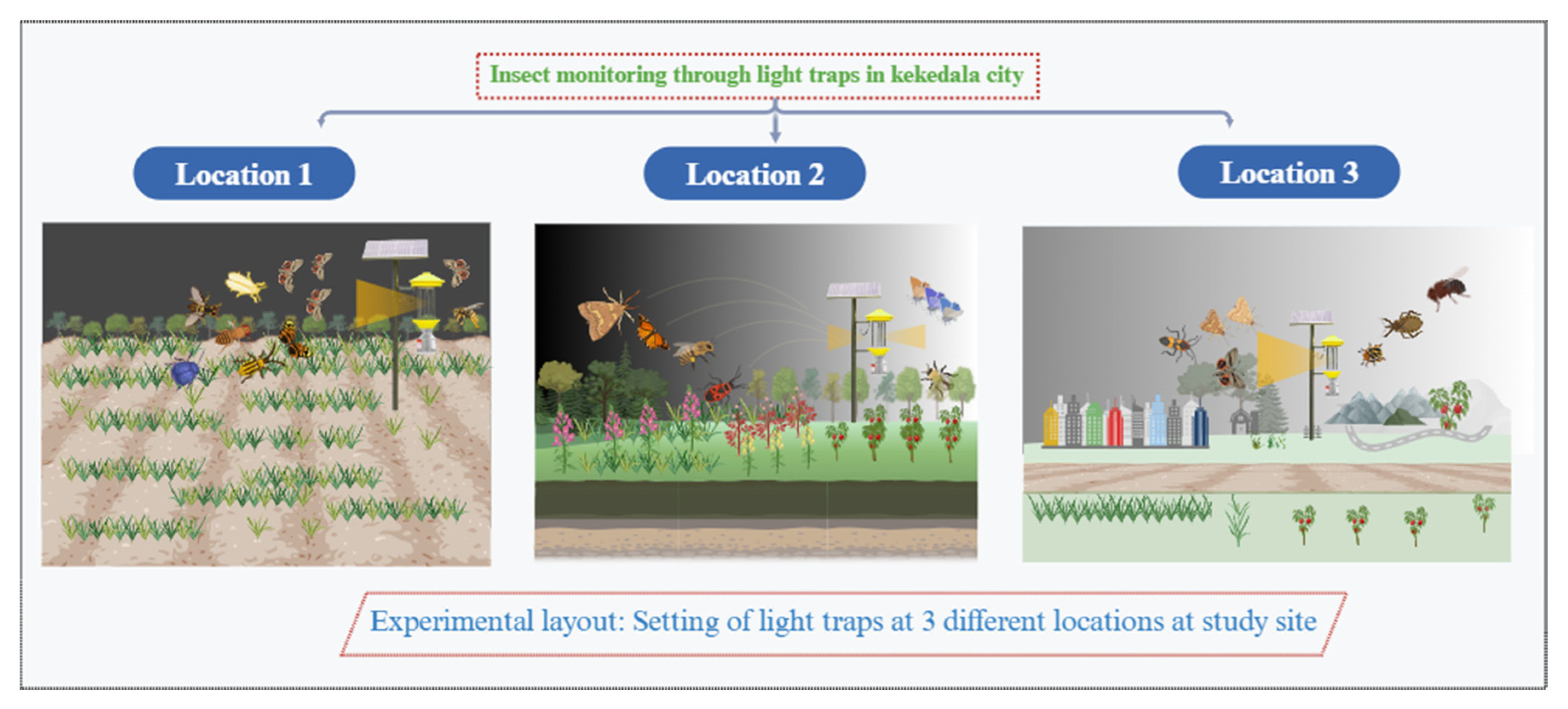

2.2. Description and Setting of Research Site

| Location | Division | Area Name | Type of Vegetation | Total Area |

| 1 2 3 |

4th 4th 4th |

Kekedala, Ili Kazakh autonomous prefecture Kekedala, Ili Kazakh autonomous prefecture. Kekedala, Ili Kazakh autonomous prefecture. |

Terrestrial, wild shrubs and weeds China Fir, plum trees, Apple trees and weeds. Ornamental trees, wild grass, apple trees. |

30-35 m2 80-90 m2 50-60 m2 |

2.3. Setting of Traps

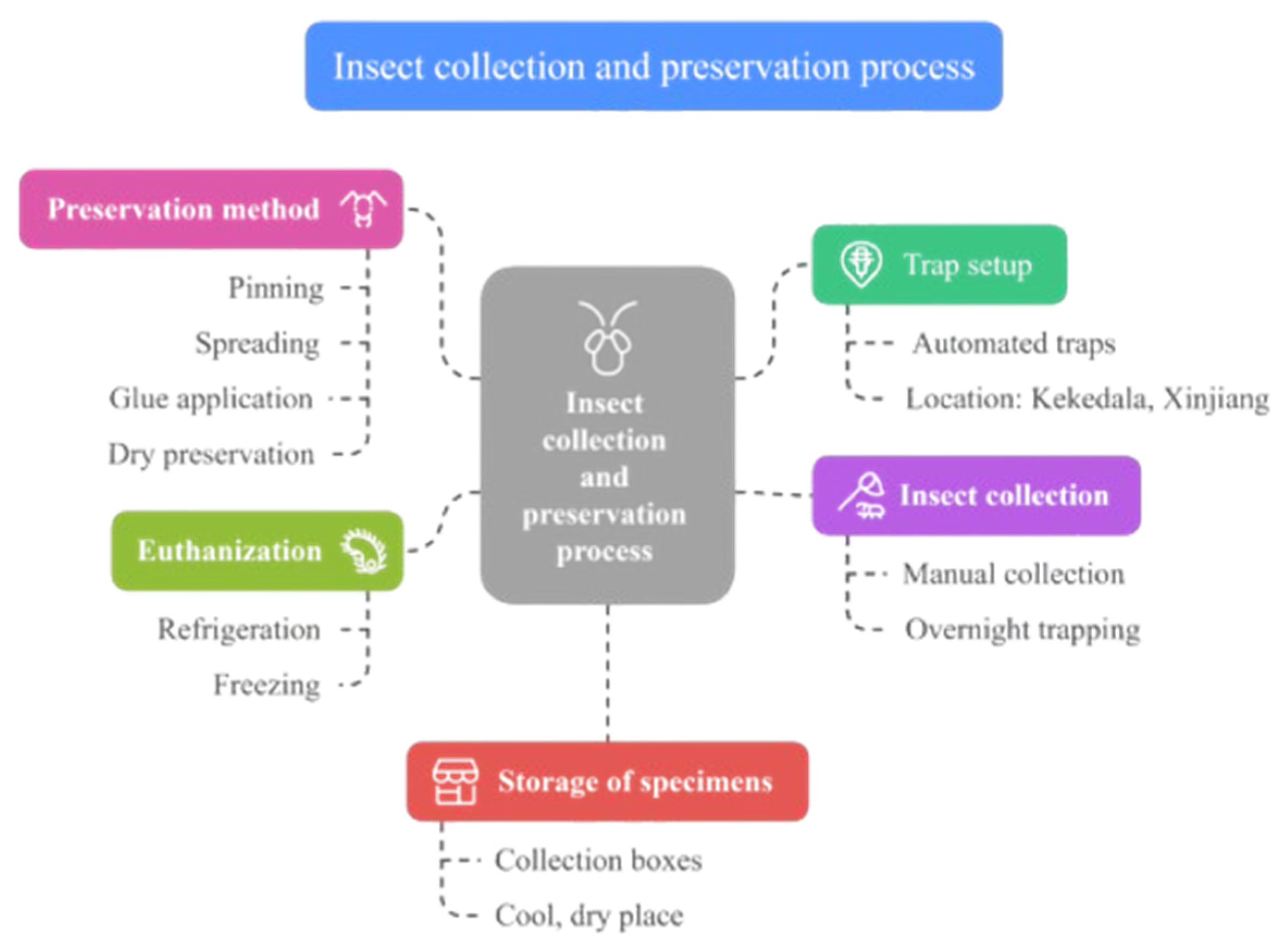

2.4. Sampling and Collection of Insects

2.5. Identification and Preservation Method

3. Data Analysis and Results

Data Preparation and Cleaning

Data Import

Data Structure and Type Conversion

Missing Values and Outlier Removal

Exploratory Data Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

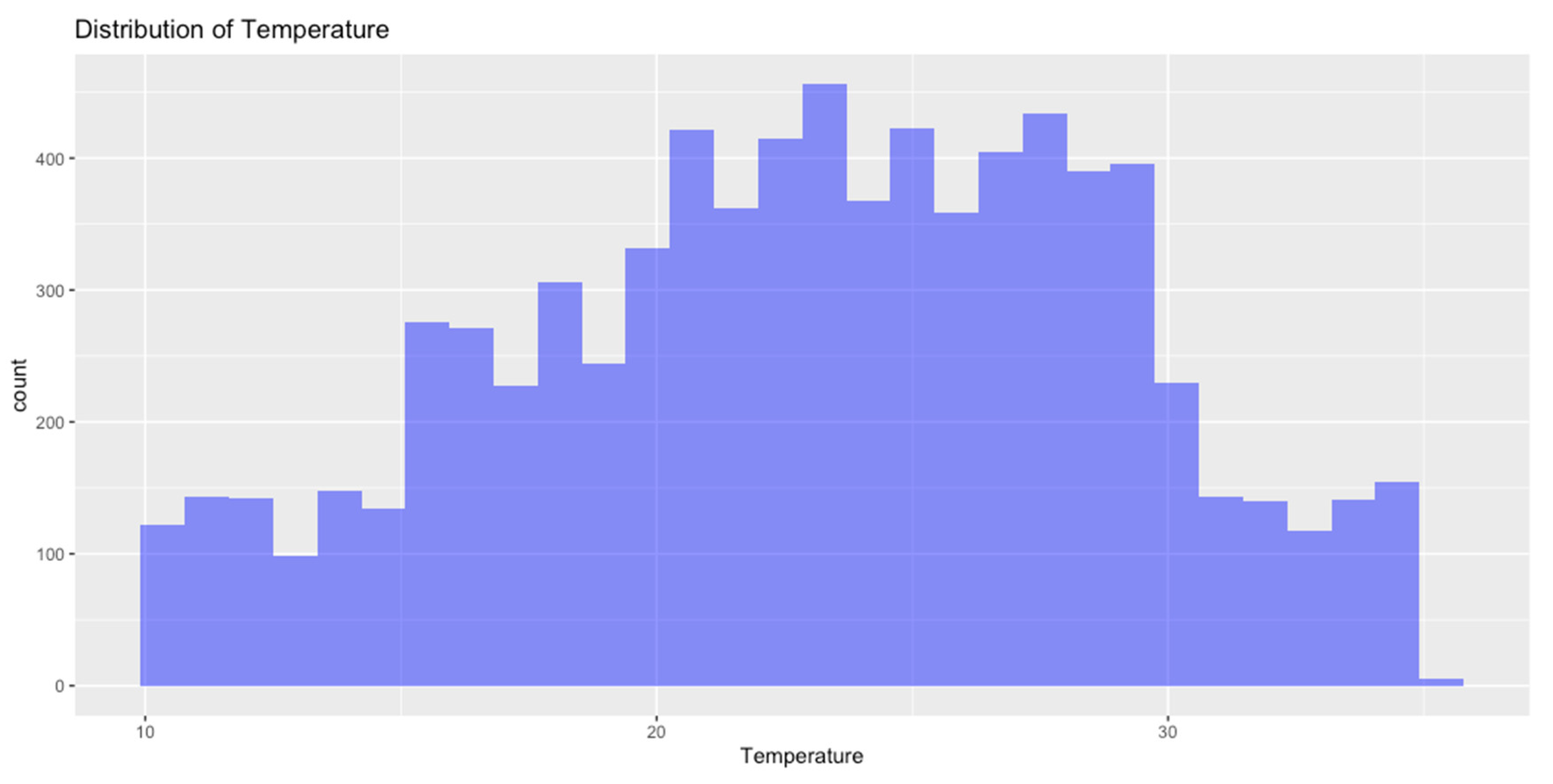

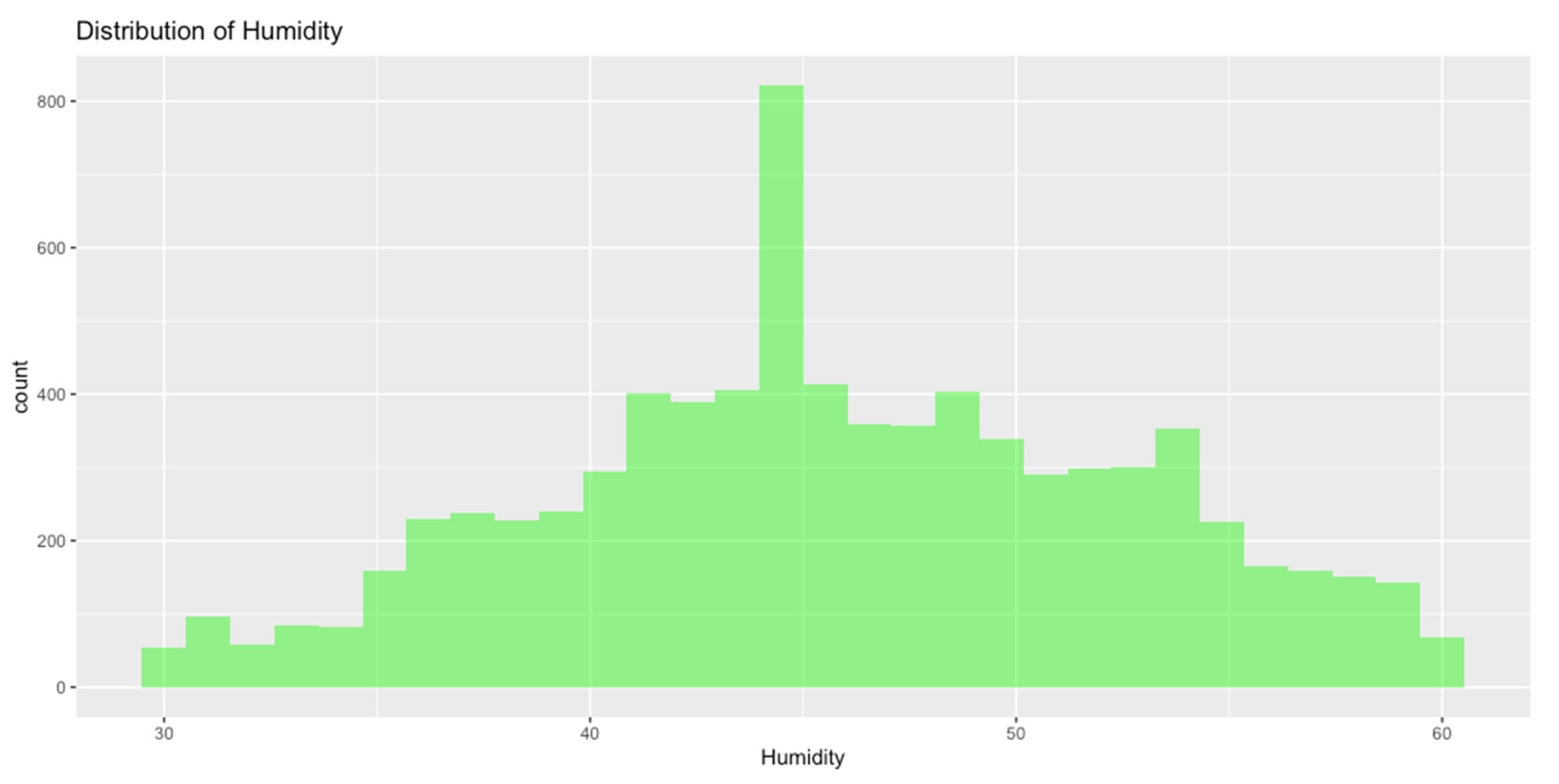

Distribution of Data

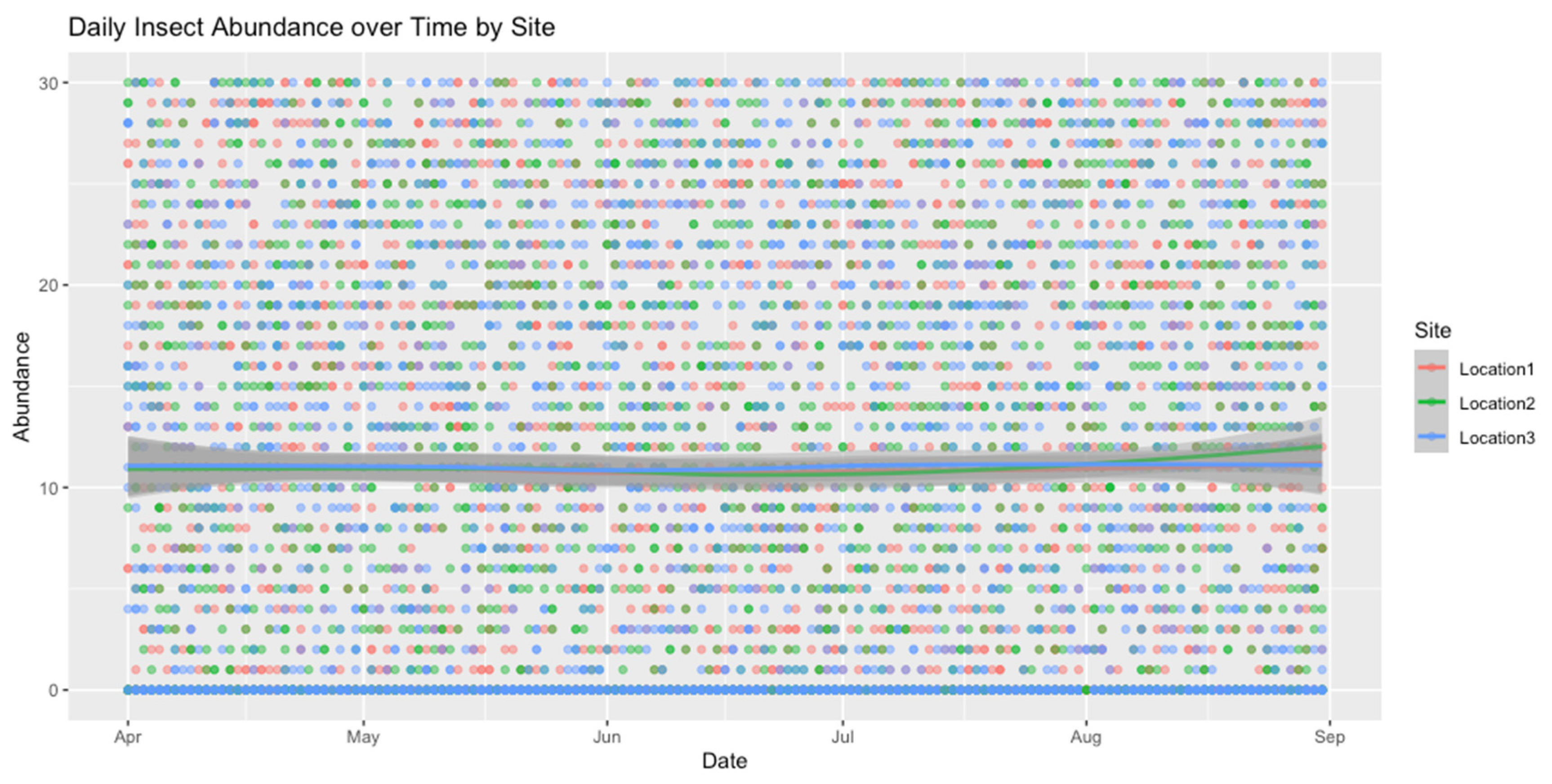

Temporal Trends

Biodiversity Indices

Construction of Site-Species Matrix

Calculation of Diversity Indices

- Species Richness (S)

- Shannon Diversity Index (H′)

- Simpson’s Index (D)

- Evenness (E)

- Shannon (H’): This index reflects the species diversity, considering both the number of species and the evenness of their distribution. The values for all three locations are very similar, with Location 1 having an H’ of 2.831, Location 2 at 2.830, and Location 3 at 2.832, indicating relatively high species diversity across all sites.

- Simpson (D): Simpson’s index measures the probability that two randomly selected individuals from the sample will belong to the same species. Higher values indicate lower diversity. The values for all three locations are close to 0.941, suggesting a similar level of dominance of certain species across all sites.

- Richness (S): This is the total number of species observed at each site. All locations have the same richness value of 17 species, indicating a consistent number of species across the study locations.

- Evenness (E): This index indicates how evenly individuals are distributed among the different species. The values are very close to 1 for all sites, with Location 1 at 0.999, Location 2 at 0.999, and Location 3 at 0.9997. High evenness values suggest that the species populations are relatively evenly distributed, with no single species dominating.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of Abundance and Diversity Across Sites

Seasonal Differences

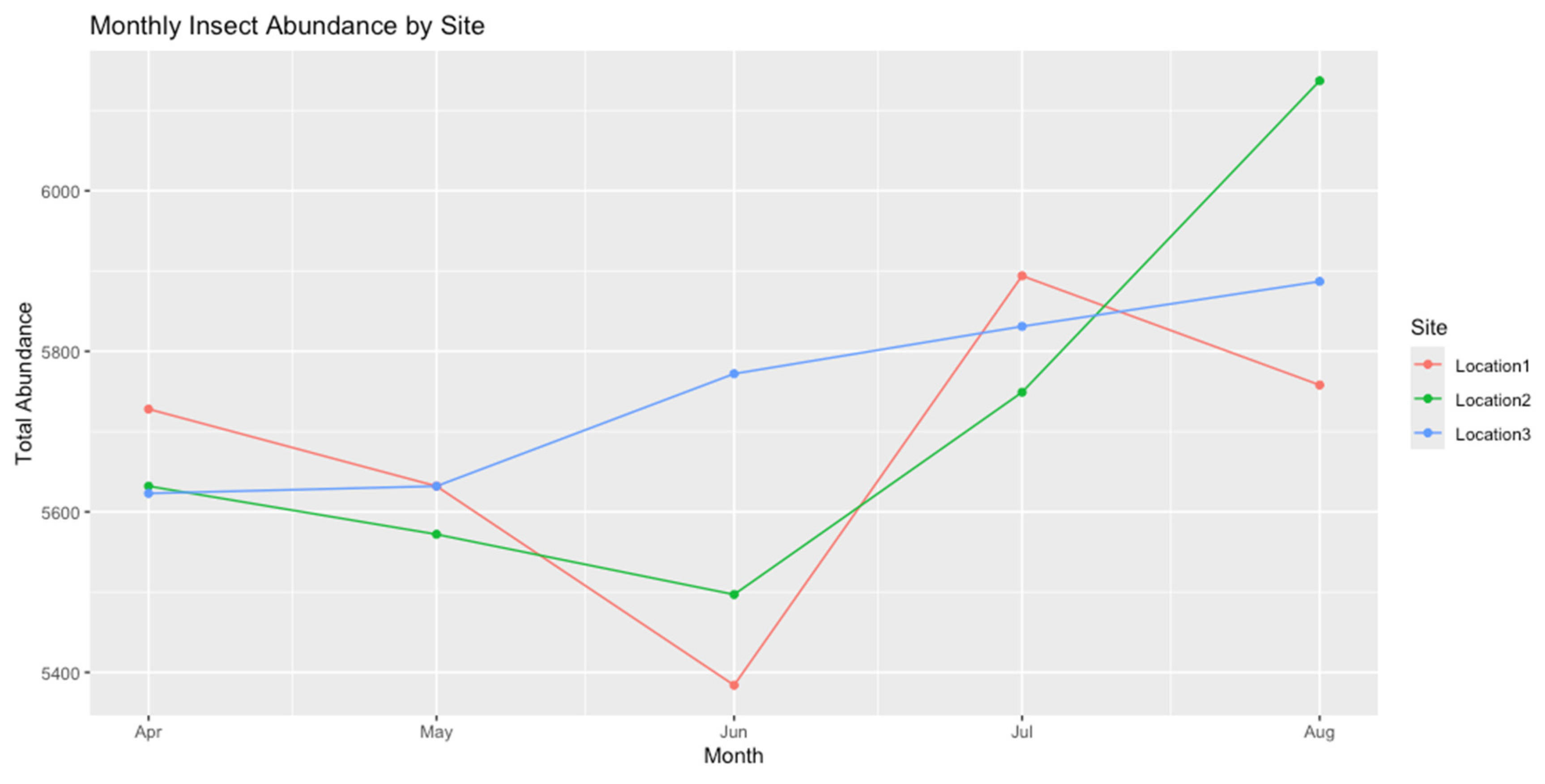

Statistical Analysis Results Comparing Monthly Abundance Across Sites

| Site | Month | Monthly Total |

| Location1 | April/2023 | 5728 |

| Location1 | May/2023 | 5632 |

| Location1 | June/2023 | 5384 |

| Location1 | July/2023 | 5894 |

| Location1 | August/2023 | 5758 |

| Location2 | April/2023 | 5632 |

| Location2 | May/2023 | 5572 |

| Location2 | June/2023 | 5497 |

| Location2 | July/2023 | 5749 |

| Location2 | August/2023 | 6137 |

| Location3 | April/2023 | 5623 |

| Location3 | May/2023 | 5632 |

| Location3 | June/2023 | 5772 |

| Location3 | July/2023 | 5831 |

| Location3 | August/2023 | 5887 |

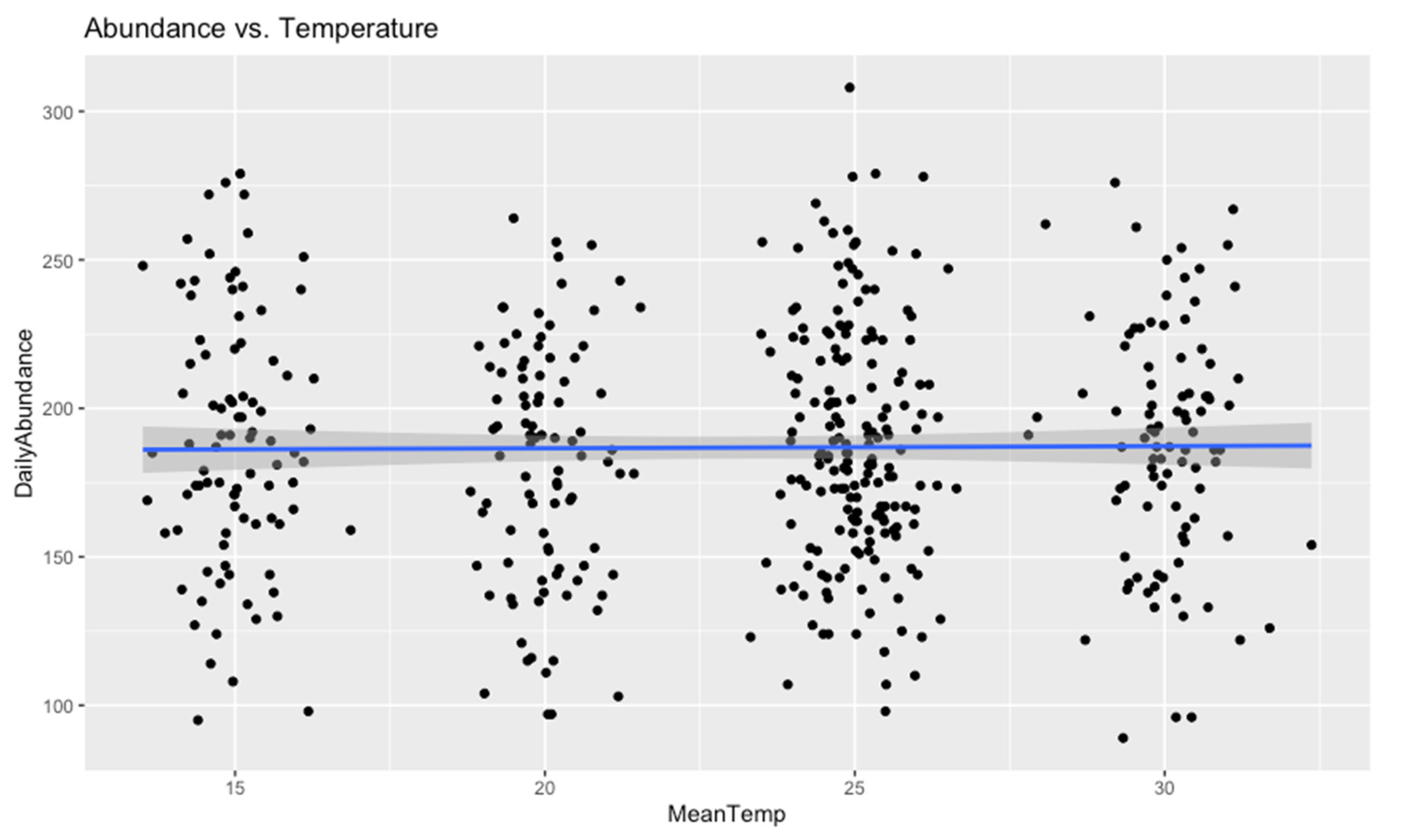

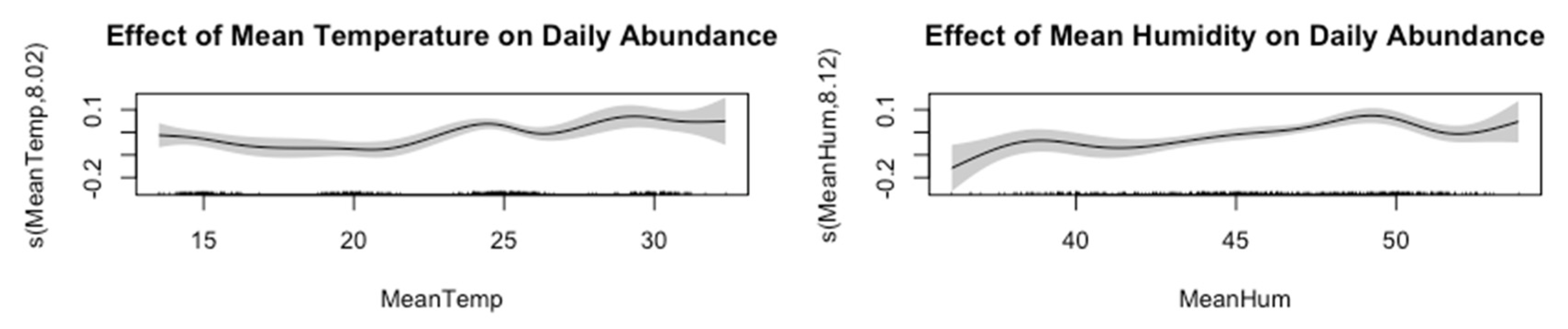

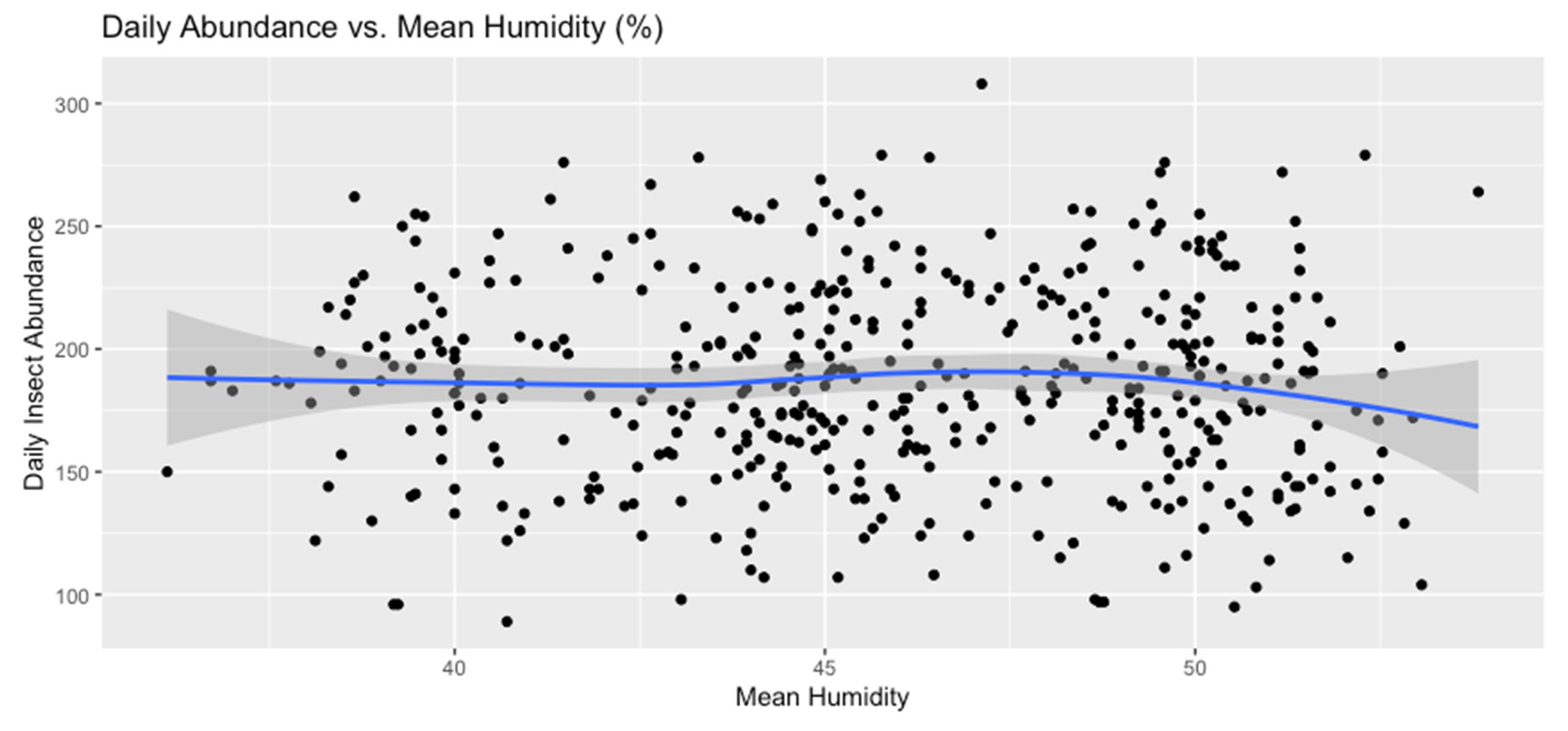

Relationship with Environmental Variables

| S | P-Value | roh | |

| DailyAbundance & MeanHum | 16653600 | 0.4768 | -0.03329274 |

| DailyAbundance & MeanTemp | 15997559 | 0.8742 | 0.007412073 |

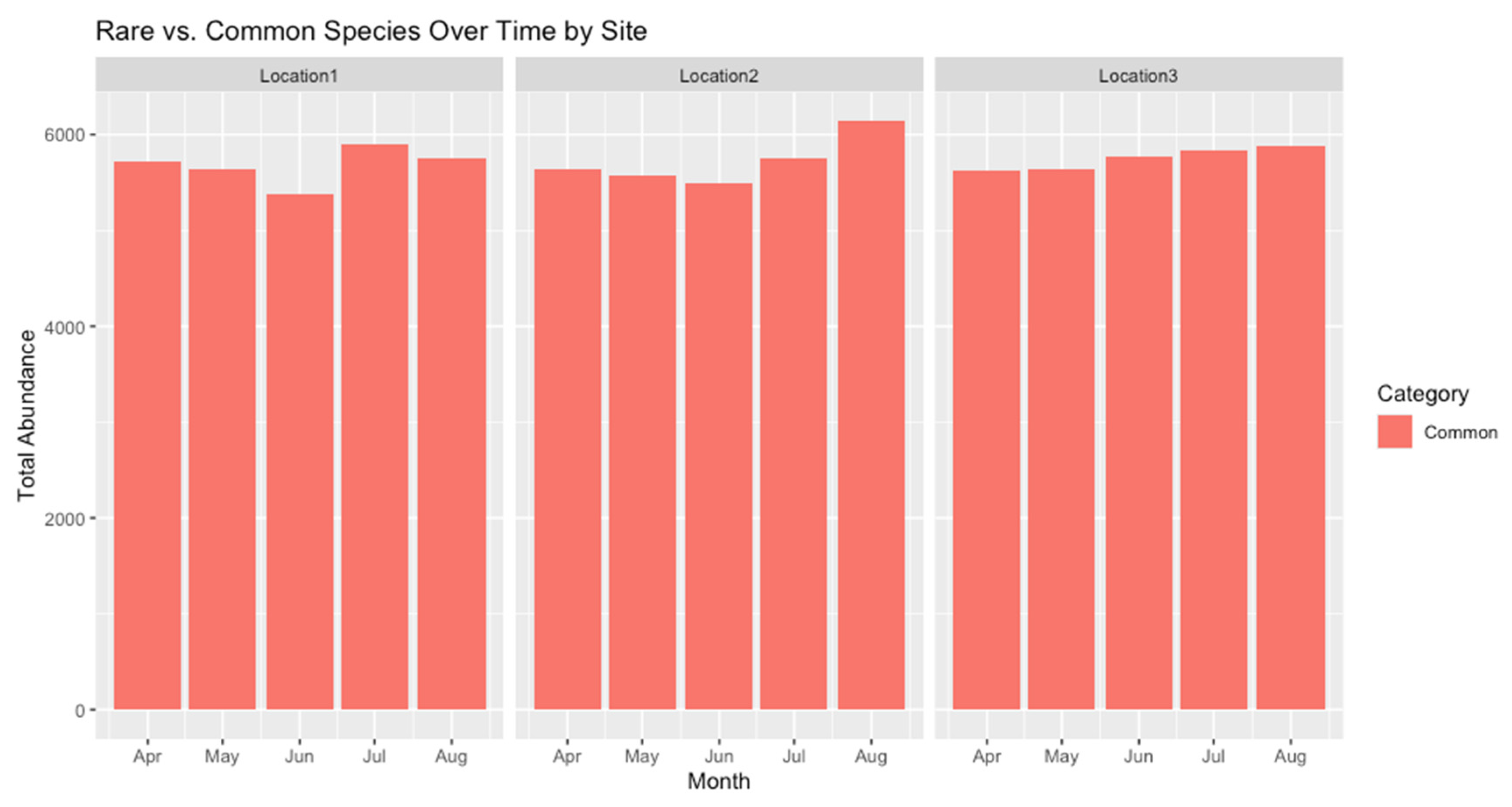

Species-Level Exploration: Rare vs. Common Species

Identify and Classify Rare vs. Common Species

Advanced Statistical Modeling

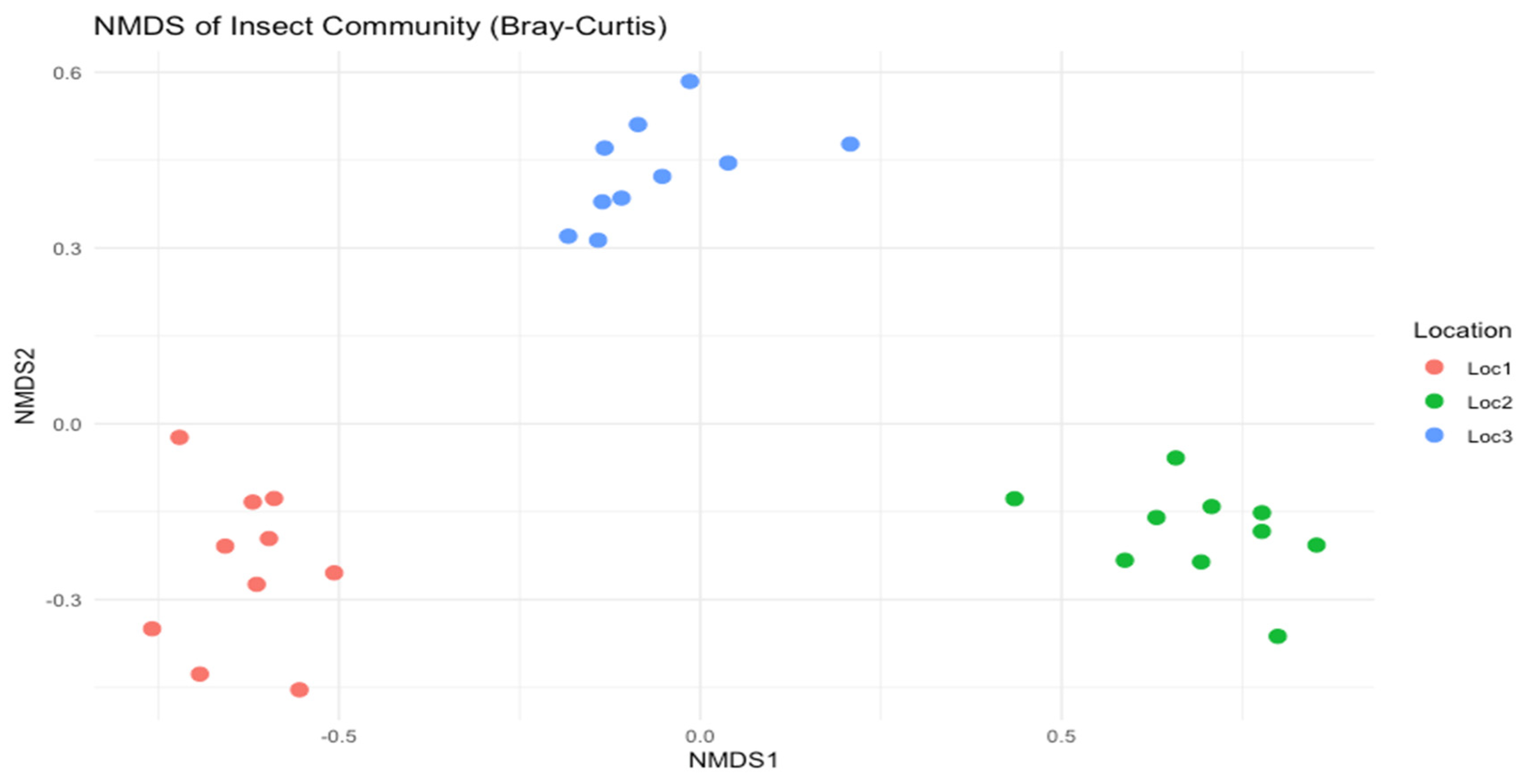

PERMANOVA

Indicator Species Analysis

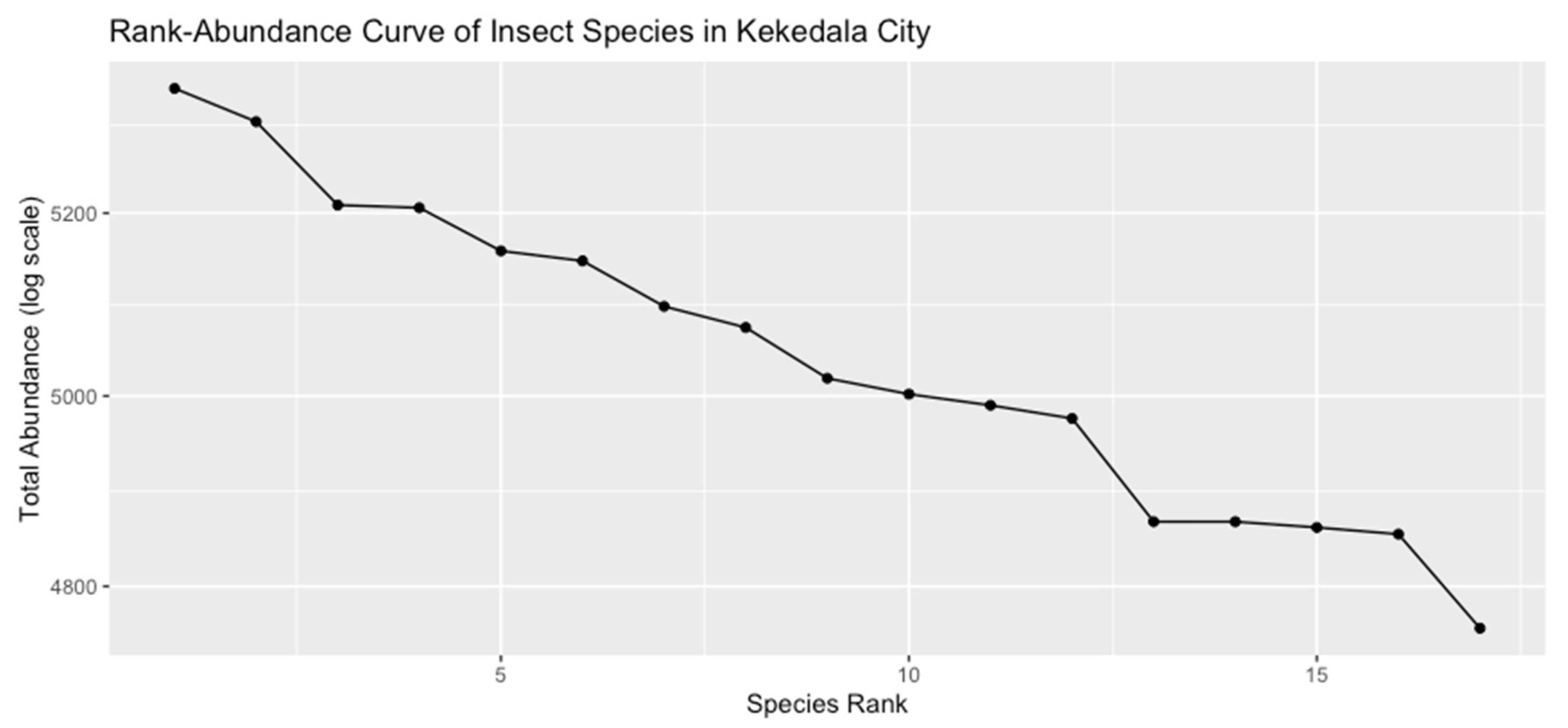

Rank-Abundance Patterns

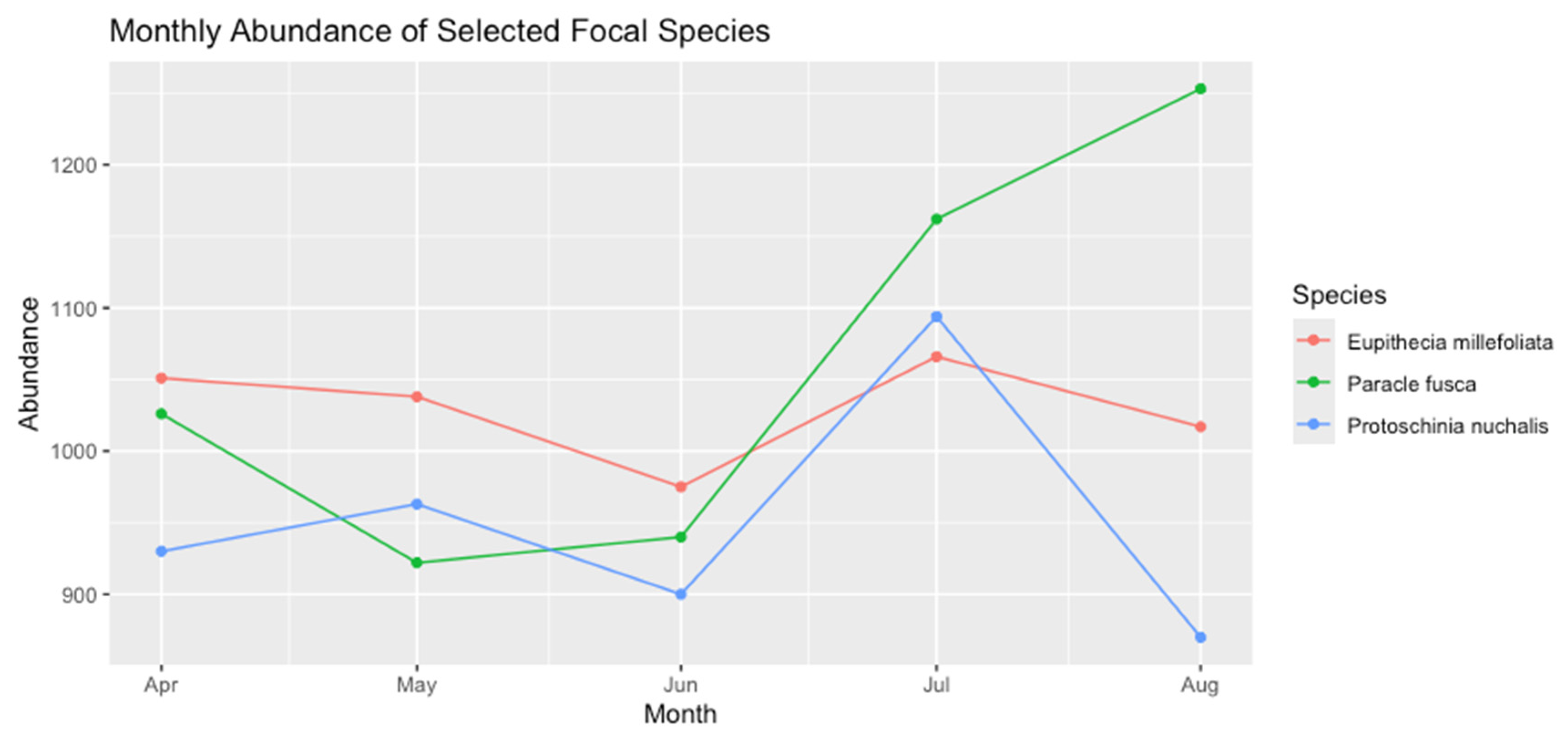

Temporal Analysis of Key Species

Monthly Distribution

|

| Figure A (1 & 2) Pinacoplus didymogramma |

|

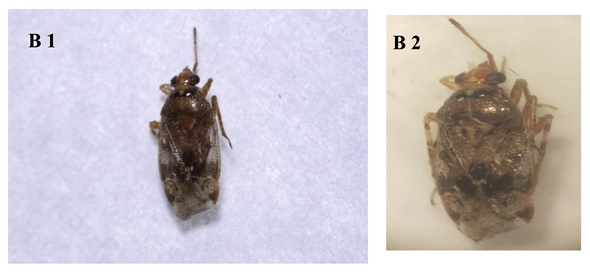

| Figure B (1 & 2) Stethoconus pyri |

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical statement

Code availability

Data availability statement

Acknowledgement

Conflict of interest statement

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

References

- Pandey, P.C.; Pandey, M. Highlighting the role of agriculture and geospatial technology in food security and sustainable development goals. Sustainable Development 2023, 31, 3175-3195. [CrossRef]

- Noriega, J.A.; Hortal, J.; Azcárate, F.M.; Berg, M.P.; Bonada, N.; Briones, M.J.; Del Toro, I.; Goulson, D.; Ibanez, S.; Landis, D.A. Research trends in ecosystem services provided by insects. Basic and applied ecology 2018, 26, 8-23.

- Wei, H.; Jian-jun, X.; Hua, Y.; Yuan-yu, C.; Xiao-jun, S. Study on pest species and population dynamics based on application of insect sex lures in processing tomato fields. Xinjiang Agricultural Sciences 2016, 53, 1618.

- Sharma, R.P.; Boruah, A.; Khan, A.; Thilagam, P.; Sivakumar, S.; Dhapola, P.; Singh, B.V. Exploring the Significance of Insects in Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Examination of Entomological Studies. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 2023, 13, 1243-1252. [CrossRef]

- Madesh, K. Exploring the Secrets of Insect Biodiversity. Insect 2024.

- Ali, H.; Hou, Y.; Tahir, M.B. Climate change and insect biodiversity: challenges and implications; CRC Press: 2023.

- Yi, Z.; Jinchao, F.; Dayuan, X.; Weiguo, S.; Axmacher, J. Insect diversity: addressing an important but strongly neglected research topic in China. Journal of Resources and Ecology 2011, 2, 380-384.

- Abbas, M.; Ramzan, M.; Hussain, N.; Ghaffar, A.; Hussain, K.; Abbas, S.; Raza, A. Role of light traps in attracting, killing and biodiversity studies of insect pests in Thal. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research 2019, 32, 684-690. [CrossRef]

- Medan, D.; Devoto, M. Ambophily, not entomophily: the reproduction of the perennial Discaria chacaye (Rhamnaceae: Colletieae) along a rainfall gradient in Patagonia, Argentina. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2017, 303, 841-851. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Sultana, R.; Islam, S.; Zian Reza, S. A Study on Light Traps for Attracting and Killing the Insects Using PKL Electricity. In Proceedings of the Advances in Medical Physics and Healthcare Engineering: Proceedings of AMPHE 2020, 2021; pp. 135-143.

- Enkhtur, K.; Brehm, G.; Boldgiv, B.; Pfeiffer, M. Effects of grazing on macro-moth assemblages in two different biomes in Mongolia. Ecological indicators 2021, 133, 108421. [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, L.J.; Fisher, B.L.; Miraldo, A.; Goodsell, R.M.; Iwaszkiewicz-Eggebrecht, E.; Raharinjanahary, D.; Rajoelison, E.T.; Łukasik, P.; Andersson, A.F.; Ronquist, F. Temperature and water availability drive insect seasonality across a temperate and a tropical region. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2024, 291, 20240090. [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.J.; Li, E.; Bahlai, C.A.; Meineke, E.K.; McGlynn, T.P.; Brown, B.V. Local-and landscape-scale variables shape insect diversity in an urban biodiversity hot spot. Ecological Applications 2020, 30, e02089. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Tougeron, K.; Gols, R.; Heinen, R.; Abarca, M.; Abram, P.K.; Basset, Y.; Berg, M.; Boggs, C.; Brodeur, J. Scientists’ warning on climate change and insects. Ecological monographs 2023, 93, e1553. [CrossRef]

- Bhagarathi, L.K.; Maharaj, G. Impact of climate change on insect biology, ecology, population dynamics, and pest management: A critical review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2023, 19, 541-568.

- Sunil, V.; Majeed, W.; Chowdhury, S.; Riaz, A.; Shakoori, F.R.; Tahir, M.; Dubey, V.K. Insect Population Dynamics and Climate Change. In Climate Change and Insect Biodiversity; CRC Press: 2023; pp. 121-146.

- Gaona, F.P.; Iñiguez-Armijos, C.; Brehm, G.; Fiedler, K.; Espinosa, C.I. Drastic loss of insects (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in urban landscapes in a tropical biodiversity hotspot. Journal of Insect Conservation 2021, 25, 395-405. [CrossRef]

- Danabalan, R.; Planillo, A.; Butschkau, S.; Deeg, S.; Pierre, G.; Thion, C.; Calvignac-Spencer, S.; Kramer-Schadt, S.; Mazzoni, C. Comparison of mosquito and fly derived DNA as a tool for sampling vertebrate biodiversity in suburban forests in Berlin, Germany. Environmental DNA 2023, 5, 476-487. [CrossRef]

- Liere, H.; Egerer, M. Ecology of insects and other arthropods in urban agroecosystems. In Urban ecology: its nature and challenges; CABI Wallingford UK: 2020; pp. 193-213.

- Nuñez-Penichet, C.; Cobos, M.E.; Checa, M.F.; Quinde, J.D.; Aguirre, Z.; Aguirre, N. High diversity of diurnal Lepidoptera associated with landscape heterogeneity in semi-urban areas of Loja City, southern Ecuador. Urban Ecosystems 2021, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Dröge, S.; Martin, D.A.; Andriafanomezantsoa, R.; Burivalova, Z.; Fulgence, T.R.; Osen, K.; Rakotomalala, E.; Schwab, D.; Wurz, A.; Richter, T. Listening to a changing landscape: Acoustic indices reflect bird species richness and plot-scale vegetation structure across different land-use types in north-eastern Madagascar. Ecological Indicators 2021, 120, 106929. [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.S.; Kehail, M.A.; Almannaa, S.A.; Alkhalifa, A.H.; Alqahtani, A.M.; Altalhi, M.H.; Alkhamis, H.H.; Alowaifeer, A.M.; Alrefaei, A.F. Seasonal Occurrence and Biodiversity of Insects in an Arid Ecosystem: An Ecological Study of the King Abdulaziz Royal Reserve, Saudi Arabia. Biology 2025, 14, 254. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fu, X.; Zhao, S.; Shen, X.; Wyckhuys, K.A.; Wu, K. Long-term shifts in abundance of (migratory) crop-feeding and beneficial insect species in northeastern Asia. Journal of Pest Science 2020, 93, 583-594. [CrossRef]

- Denlinger, D.L. Insect diapause; Cambridge University Press: 2022.

- Wu, S.; Shiao, M.T. Temporal and forest-type related dynamics of moth assemblages in a montane cloud forest in subtropical Taiwan. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 2023, 26, 102073. [CrossRef]

- Magura, T.; Lövei, G.L. Consequences of urban living: Urbanization and ground beetles. Current Landscape Ecology Reports 2021, 6, 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Forero-Chavez, N.; Arenas-Clavijo, A.; Armbrecht, I.; Montoya-Lerma, J. Urban patches of dry forest as refuges for ants and carabid beetles in a neotropical overcrowded city. Urban Ecosystems 2024, 27, 1263-1278. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.T.; Munshi-South, J. Evolution of life in urban environments. Science 2017, 358, eaam8327. [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, G.V.d.S.; Mesquita, V.P.; Bobrowiec, P.E.D.; Iannuzzi, L.; Salomão, R.P.; Cornelius, C. Habitat loss reduces abundance and body size of forest-dwelling dung beetles in an Amazonian urban landscape. Urban Ecosystems 2024, 27, 1175-1190. [CrossRef]

- Amador Rocha, E. Insect urban ecology: aphid interactions with natural enemies and mutualists. University of Reading, 2017.

- Frizzas, M.R.; Batista, J.L.; Rocha, M.V.; Oliveira, C.M. Diversity of Scarabaeinae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in an urban fragment of Cerrado in Central Brazil. European Journal of Entomology 2020, 117, 273-281. [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.J.; Fox, R. Insect responses to global change offer signposts for biodiversity and conservation. Ecological Entomology 2021, 46, 699-717. [CrossRef]

- Tougeron, K.; Brodeur, J.; Le Lann, C.; van Baaren, J. How climate change affects the seasonal ecology of insect parasitoids. Ecological Entomology 2020, 45, 167-181. [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Hedlund, J.; Reynolds, D.R.; Zhai, B.; Hu, G.; Chapman, J.W. The ‘migratory connectivity’concept, and its applicability to insect migrants. Movement Ecology 2020, 8, 48.

- Juhász, E.; Németh, Z.; Gór, Á.; Végvári, Z. Multilevel climatic responses in migratory insects. Ecological Entomology 2023, 48, 755-764. [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, W.L.; Doyle, T.; Massy, R.; Weston, S.T.; Davies, K.; Cornelius, E.; Collier, C.; Chapman, J.W.; Reynolds, D.R.; Wotton, K.R. The most remarkable migrants—systematic analysis of the Western European insect flyway at a Pyrenean mountain pass. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2024, 291, 20232831. [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.O.C.; Kunin, W.E. Effect of bulb type on moth trap catch and composition in UK gardens. 2024.

- Kammar, V.; Rani, A.; Kumar, K.; Chakravarthy, A.K. Light trap: a dynamic tool for data analysis, documenting, and monitoring insect populations and diversity. Innovative pest management approaches for the 21st century: harnessing automated unmanned technologies 2020, 137-163.

- Mathejczyk, T.F.; Wernet, M.F. Sensing polarized light in insects. In Oxford research encyclopedia of neuroscience; 2017.

- Hinson, K.R. Species diversity and seasonal abundance of Scarabaeoidea at four locations in South Carolina. Clemson University, 2011.

- Wenzel, A.; Grass, I.; Belavadi, V.V.; Tscharntke, T. How urbanization is driving pollinator diversity and pollination–A systematic review. Biological Conservation 2020, 241, 108321. [CrossRef]

- Fenoglio, M.S.; Calviño, A.; González, E.; Salvo, A.; Videla, M. Urbanisation drivers and underlying mechanisms of terrestrial insect diversity loss in cities. Ecological Entomology 2021, 46, 757-771. [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.M.; Audusseau, H.; Hassall, C.; Keyghobadi, N.; Sinu, P.A.; Saunders, M.E. Insect ecology and conservation in urban areas: An overview of knowledge and needs. Insect conservation and diversity 2024, 17, 169-181. [CrossRef]

- Keeve, N. Towards multispecies spaces. Rethinking architectural practice in the context of urban biodiversity loss. 2023.

- Marchante, E.; López-Núnez, F.A.; Duarte, L.N.; Marchante, H. The role of citizen science in biodiversity monitoring: when invasive species and insects meet. In Biological Invasions and Global Insect Decline; Elsevier: 2024; pp. 291-314.

- Richter, A.; Hauck, J.; Feldmann, R.; Kühn, E.; Harpke, A.; Hirneisen, N.; Mahla, A.; Settele, J.; Bonn, A. The social fabric of citizen science—drivers for long-term engagement in the German butterfly monitoring scheme. Journal of Insect Conservation 2018, 22, 731-743. [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.; Diekötter, T.; Höffler, T.; Kremer, K. Biodiversity citizen science: Outcomes for the participating citizens. People and Nature 2021, 3, 294-311. [CrossRef]

- Rega-Brodsky, C.C.; Aronson, M.F.; Piana, M.R.; Carpenter, E.-S.; Hahs, A.K.; Herrera-Montes, A.; Knapp, S.; Kotze, D.J.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Moretti, M. Urban biodiversity: State of the science and future directions. Urban Ecosystems 2022, 25, 1083-1096. [CrossRef]

- Nilon, C.H.; Aronson, M.F.; Cilliers, S.S.; Dobbs, C.; Frazee, L.J.; Goddard, M.A.; O’Neill, K.M.; Roberts, D.; Stander, E.K.; Werner, P. Planning for the future of urban biodiversity: a global review of city-scale initiatives. BioScience 2017, 67, 332-342. [CrossRef]

| Site | MeanAbundance | SDAbundance | MeanTemp | SDTemp | MeanHumidity | SDHumidity |

| Location1 | 10.91734 | 10.23830 | 23.08989 | 5.842402 | 45.93310 | 6.969173 |

| Location2 | 10.99077 | 10.10064 | 22.97605 | 5.869153 | 45.84006 | 6.858444 |

| Location3 | 11.05152 | 10.17045 | 23.07732 | 5.884701 | 45.92349 | 6.893748 |

| Location1 | Location2 | Location3 | |

| Acronicta impleta | 1486 | 1714 | 1661 |

| Amara aulica | 1675 | 1474 | 1718 |

| Anomala errans | 1519 | 1812 | 1645 |

| Anomala nimbosa | 1678 | 1689 | 1707 |

| Athetis gluteosa | 1694 | 1536 | 1789 |

| Caddisfly | 1611 | 1654 | 1832 |

| Cicindela ocellata | 1680 | 1846 | 1815 |

| Eupithecia millefoliata | 1892 | 1618 | 1637 |

| Goat moth | 1628 | 1763 | 1611 |

| Helicoverpa zea | 1769 | 1758 | 1682 |

| Heteronychus Arator | 1698 | 1595 | 1574 |

| Anarta trifolii | 1661 | 1526 | 1667 |

| Oryctes rhinoceros | 1896 | 1673 | 1637 |

| Paracle fusca | 1714 | 1975 | 1614 |

| Polyphylla ragusae | 1523 | 1847 | 1788 |

| Protoschinia nuchalis | 1559 | 1480 | 1718 |

| Tinea columbariella | 1713 | 1627 | 1650 |

| Site | Shannon (H’) | Simpson (D) | Richness (S) | Evenness (E) |

| Location1 | 2.83099906 | 0.94091429 | 17 | 0.99921846 |

| Location2 | 2.82994854 | 0.94079034 | 17 | 0.99884767 |

| Location3 | 2.83226126 | 0.94106369 | 17 | 0.99966395 |

| Data | W | p-value |

| Abundance Daily Total | 0.99518 | 0.1651 |

| Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F Value | Pr(>F) | |

| Site | 2 | 399 | 199.6 | 0.121 | 0.886 |

| Residuals | 456 | 754578 | 1654.8 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr (>|z|) | |

| (Intercept) | 5.452458 | 0.111194 | 49.035 | <2e-16*** |

| MeanTemp | -0.002244 | 0.001384 | -1.621 | 0.1050 |

| MeanHum | -0.003856 | 0.001784 | -2.161 | 0.0307* |

| SiteLocation2 | 0.006094 | 0.008384 | 0.727 | 0.4673 |

| SiteLocation3 | 0.012159 | 0.008367 | 1.453 | 0.1462 |

| Df | Sum of Sqs R2 | F Pr(>F) | |

| Model | 2 | 0.0016761 | 1 |

| Residual | 0 | 0.0000000 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 0.0016761 | 1 |

| Multilevel pattern analysis | |

| Association function: | IndVal.g |

| Significance level (alpha): | 0.05 |

| Total number of species: | 17 |

| Selected number of species: | 0 |

| Number of species associated to 1 group | 0 |

| Number of species associated to 2 groups | 0 |

| Species | TotalAbundance | Rank | |

| 1 | Cicindela ocellata | 5341 | 1 |

| 2 | Paracle fusca | 5303 | 2 |

| 3 | Helicoverpa zea | 5209 | 3 |

| 4 | Oryctes rhinoceros | 5206 | 4 |

| 5 | Polyphylla ragusae | 5158 | 5 |

| 6 | Eupithecia millefoliata | 5147 | 6 |

| 7 | Tasiagma ciliata | 5097 | 7 |

| 8 | Anomala nimbosa | 5074 | 8 |

| 9 | Athetis gluteosa | 5019 | 9 |

| 10 | Cossus cossus | 5002 | 10 |

| 11 | Tinea columbariella | 4990 | 11 |

| 12 | Anomala errans | 4976 | 12 |

| 13 | Amara aulica | 4867 | 13 |

| 14 | Heteronychus Arator | 4867 | 14 |

| 15 | Acronicta impleta | 4861 | 15 |

| 16 | Anarta trifolii | 4854 | 16 |

| 17 | Protoschinia nuchalis | 4757 | 17 |

| Families | Location | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrididae | 1 2 3 |

4 2 4 |

4 2 4 |

| Anthocoridae | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Apidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 2 |

1 1 2 |

| Argyresthiidae | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Blastobasidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Belostomatidae | 1 3 |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Calliphoridae | 1 2 3 |

1 2 1 |

1 2 1 |

| Carabidae | 1 2 3 |

10 3 4 |

10 3 4 |

| Cerambycidae | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chrysopidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Cicadellidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Cicadidae | 1 3 |

2 1 |

2 1 |

| Cicindelidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Coccinellidae | 1 2 3 |

7 4 6 |

7 4 6 |

| Coenagrionidae | 1 3 |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Corixidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Cossidae | 1 2 3 |

1 2 3 |

1 2 3 |

| Crambidae | 1 2 3 |

4 8 5 |

5 9 6 |

| Curculionidae | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Dixidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Dytiscidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 2 |

1 1 2 |

| Elateridae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Empusidae | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Ephemeridae | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Erebidae | 1 2 3 |

4 5 4 |

4 5 4 |

| Forficulidae | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Geometridae | 1 2 3 |

4 5 7 |

4 5 7 |

| Gomphidae | 1 2 3 |

3 1 1 |

3 1 1 |

| Gryllidae | 1 3 1 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Gryllotalpidae | 2 3 |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Labiduridae | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Lasiocampidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Libellulidae | 1 2 3 |

2 1 1 |

2 1 1 |

| Miridae | 1 3 |

1 2 |

1 2 |

| Mycetophilidae | 1 2 |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Myrmeleontidae | 1 2 3 |

22 16 15 |

22 16 15 |

| Noctuidae | 1 3 |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Nolidae | 1 3 |

11 | 1 1 |

| Notodontidae | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Papilionidae | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Passalidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Peltoperlidae | 1 2 3 |

2 1 2 |

2 1 2 |

| Pentatomidae | 1 2 3 |

2 3 3 |

2 3 3 |

| Pyralidae | 1 2 3 |

3 1 3 |

3 1 3 |

| Reduviidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Rhyacophilidae | 1 2 3 |

7 5 6 |

9 6 7 |

| Scarabaeidae | 1 2 3 |

4 4 4 |

4 4 4 |

| Sphingidae | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Staphylinidae | 1 3 1 |

1 1 2 |

1 1 2 |

| Syrphidae | 2 3 |

3 3 |

3 3 |

| Tineidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Tabanidae | 2 3 |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Tortricidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 1 |

1 1 1 |

| Vespidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 2 |

1 1 2 |

| Yponomeutidae | 1 2 3 |

1 1 2 |

1 1 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).