1. Introduction

The giant honey bee (

A. dorsata) is an economically important species as a crop pollinator in Pakistan, South Asia, and South-East Asia [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. This honey bee inhabits the Asian tropics, where its colonies produce substantial honey and beeswax in a single, large comb [

1]. In Pakistan,

A. dorsata contributed 3-35% of the total honey production [

14]. In recent years, the number of colonies of this honey bee has markedly declined [

7]. The main reason for such a decline is the erosion of nesting sources and traditional destructive methods of honey hunting. The latter practice involves a method of colony smoking/burning and destruction of combs that leads to large-scale bee mortality. It is opined that obtaining good quality honey from

A. dorsata using traditional methods of honey harvesting was not a desirable technique [

15]. This honey-hunting practice leads to the mass destruction of colonies, thus adversely affecting the indigenous pollination services. For the sustainability of pollination services and the safe honey harvest from this honey bee, proper domestication, handling and conservation of this honey bee have become very important. This necessity prompted the undertaking of these investigations.

The giant honey bee has a migratory habit. Many colonies of this honey bee migrate seasonally, living in two or more rich forage areas in the course of each year [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In the semi-arid environments of Northwest India, the migratory swarms of this honey bee arrive in October/November; stay there, reproduce and produce reproductive swarms, and then emigrate in mid-May [

7]. In the southernmost provinces in Vietnam, Minh Hai, Kien Giang and Hau Giang, which are west of the Mekong River,

A. dorsata migrates between mangrove forests on the coast and the swamp forests of

Melaleuca leucadendron farther inland, which seasonally produce much pollen and nectar [

1].

Recent reports have revealed that the colonies of this honey bee in the semi-arid environments of Northwest India make nests on the cliffs/projections of multi-storey buildings and the branches of tall trees. This honeybee has some fixed preferences for many nesting alternatives, including a preference for the nesting place/site, the height of the nesting site and the direction of the nest. These parameters seemed to play a decisive role in the selection of the source and the site for nesting [

22]. For example,

A. dorsata prefers smooth surfaces over uneven ones for nesting. The majorities of the colonies nest at heights between 14 and 17 m, on supports with an inclination from 0° to 45°; construct their nests in an east/west direction, and choose a site that has relics of the abandoned nest. Most newly arrived swarm colonies construct nests measuring 100–120 cm in length and 30–50 cm in height. The basal thickness of the comb in the non-honey region is 2.04 ± 0.6 cm whilst in the honey region; it is 5.7 ± 1.2 cm [

22].

The giant honey bee (

A. dorsata) has long faced predation from humans, who employ destructive honey-hunting methods. Therefore, there is a need to develop some non-destructive method of honey hunting for this species. Not many reports are, however, available on the domestication and conservation of this honey bee. Rafter beekeeping with

A. dorsata is known in some southeastern countries [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. However, this practice has been done in areas where natural nesting sources for this honey bee are abundant. No such efforts have been made in areas where nesting sources of this honey bee have been depleted due to man-engineered activities. Some efforts have also been made towards the hiving of this honey bee [

15,

31], but with limited success. Some ‘attraction planks’ to capture migrating

A. dorsata swarms were also developed and tested in Southwest India [

15]. The researcher claimed that his device had improved the method of honey harvest from this honey bee; however, the method was never in use.

The foregoing information clearly reveals that this honey bee is an important honey, beeswax and pollination service provider in the areas of its natural habitat. Ensuring the continued availability of these services requires the domestication and conservation of this species. This study was conducted with the following four objectives: (i) examining the role of the giant honey bee as a crop pollinator, (ii) testing nesting devices for attracting and domesticating migratory swarms, (iii) developing safe handling methods, and (iv) evaluating its potential for honey and beeswax production.

2. Material and Methods

This study took place at the College of Basic Sciences and Humanities, Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, India (

Figure 1) where various observations were documented and listed below:

2.1. The Giant Honey Bee as a Pollinator of Crops

Year-round surveys have been conducted over the past 40 years (1984–2024) to document the crop plants visited by the foragers of the giant honey bee (

A. dorsata) in Hisar, India. The foraging behavior of the visiting bees was recorded using previously established methods [

32,

33]. It was assessed whether its foragers acted as pollinators or nectar thieves on the visited flowers. Accordingly, their role in pollination services in this region was evaluated.

2.2. Trials for Domestication and Conservation of the Giant Honey Bee

The primary nesting sources of

A. dorsata in the study region were identified. Based on previous research on the nesting preferences of

A. dorsata [

22], nesting planks made of

Acacia nilotica wood were designed and fabricated measuring 1 m in length, 15 cm in width, and 0.5 m in height (

Figure 2). Molten beeswax was applied to the underside of the treated planks, while untreated planks remained free of beeswax (

Figure 2).

These planks were hung from the eves of the building of the College of Basic Sciences and Humanities, Haryana Agricultural University (Hisar, India), with the help of thin iron wires (

Figure 3). These planks were subjected to the following four treatments before testing:

- i)

Planks treated with beeswax loosely tied with the building eaves.

- ii)

Planks treated with beeswax tightly tied with the building eaves.

- iii)

Untreated planks loosely tied with the building eaves.

- iiii)

Untreated planks tightly tied with the building eaves.

The planks were hung in the preferred direction and height in October, the time of immigration of the swarm colonies of

A. dorsata in this region [

22]. Each treatment was replicated 4 times (4 planks were used for each treatment), and the experiment ran for 10 years (1984 to 1993). Therefore, each treatment had 40 replications during those 10 years. The acceptance of the wooden planks was determined/confirmed on the basis of their occupancy by the migratory swarm colonies of the giant honey bee.

2.3. Occupation and Re-Occupation Indices

Six nesting sites were selected to test the preferred locations for migratory swarms of A. dorsata. On each site, one beeswax-treated plank was hung and tightly tied to the building’s projection in 1994, and the experiment continued until 2012 (for 19 years).

The occupation and re-occupation indices were determined by the following equations:

where

OI = Occupation index.

n = Number of years when the plank was available for the first occupation.

N = Number of years when the plank was actually occupied.

where

ROI = Re-occupation index.

m = Number of times when the plank was utilized for re-occupation.

M = Number of times when the plank was actually available for re-occupation.

2.4. Trials for Handling and Taming of Colonies

These trials were performed on a bright day using colonies of this honey bee that had already settled on the artificial nesting planks. Two kinds of trials were performed and the aggressive response of the colonies was tested in the following two ways:

2.4.1. Pre-Handling Disturbance Trials

This experiment started on colonies after a month of their settlement on the nesting planks. Under this experiment, colonies were divided into two groups: i) periodically disturbed colonies; and ii) undisturbed (control) colonies. Periodic disturbance to the colonies occurred five times, each at a 10-day interval (i.e., on the 40th, 50th, 60th, 70th, and 80th days after settlement). Likewise, the disturbance was caused to the control colonies. However, a distinction was made between the disturbed and undisturbed (control) colonies. The disturbance treatment was applied repeatedly to the same five colonies selected for this purpose. However, in undisturbed colonies (control), every time fresh colonies were selected to cause disturbance. Therefore, the disturbed colonies received disturbance for five times, but the undisturbed colonies received only once. For the undisturbed colonies, disturbance was applied after specific intervals: after the 40th day to five colonies, after the 50th day to another five colonies, and so on. This trial could not be completed in the same year due to the limited number of colonies, and the experiment extended over multiple years. The disturbance to the colonies was caused by loosening the wire of the planks carrying the colonies, waving them gently up-down and to and fro in all directions, giving them minor jerks, and going near these colonies. The aggressive response of the two types of colonies was recorded as shown in

Table 1, and the intensity of aggressiveness of the two types of experimental colonies was compared.

2.4.2. Pre-Handling Taming Trials

In these trials, the colonies were divided into four groups: i) smoke-treated colonies; ii) water-treated colonies; iii) sham-treated colonies, and iv) untreated (control) colonies. For the smoke treatment, 15-20 gentle puffs of smoke were applied to the experimental colonies with the help of a smoker. Jute cloth was used for burning in the smoker to produce smoke. In the water-treated colonies, normal clean water at room temperature was sprayed on the two faces of the colony with the help of a fine nozzle one-liter capacity hand spray pump. The sham-treatment was given by making 15-20 air puffs gently on the colonies. The control colonies did not receive any taming treatment. Two types of colonies were selected for this experiment; the undisturbed colonies and previously disturbed colonies. For these trials, the colonies were lowered to chest height, and precautions were taken to minimize disturbances, aside from the experimental treatments. The aggressive responses of the colonies subjected to the four treatments were recorded (see

Table 1).

2.5. Utilization of the Attrected Giant Honey Bee for Honey and Beeswax Production, and for Live Studies

A method was developed to utilize the attracted and tamed colonies of the giant honey bee for honey and beeswax production, and for live studies. For this purpose, the colonies were periodically disturbed as described in

Section 2.4.1. Afterward, the colonies were brought down and suitably tamed following the procedures outlined in

Section 2.4.2. The honey portion of the comb was then manually excised using a knife. The excised honeycomb was subsequently squeezed by hand to extract the honey. The remaining beeswax from the deserted combs was also extracted using conventional methods. In total, honey and beeswax production from 10 domesticated colonies was recorded, and the potential of this honey bee to provide these commodities was assessed. The attracted colonies were also used for live studies of this honey bee [

7,

22].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

For the domestication trials, no statistical tests were required [

34]. However, for the handling and taming trials, an unpaired t-test [

35] and one-way ANOVA [36] were used, as appropriate, to find differences between trials.

3. Results

3.1. The Giant Honey Bee (A. dorsata) as an Important Pollinator of Crops

In Hisar, the foragers of the giant honey bee visited the flowers of more than 30 crops for pollen and nectar (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5;

Table 2).

These foragers transferred pollen in each visited flower thus bringing pollination. Based on the foraging behavior, this honey bee is documented as an important pollinator of the crops grown in this region.

3.2. The Nesting Sources of the Giant Honey Bee (A. dorsata)

In Hisar,

A. dorsata has very few places to build nest. These include man-made structures like tall buildings and water towers (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) as well as tall trees like Indian rose wood (

Dalbergia sissoo) and eucalyptus (

Eucalyptus hybrid), Indian banyan (

Ficus benghalensis) and religious peepal (

Ficus religeosa) (

Figure 8). Occasionally dwarf trees planted in undisturbed areas, such as horticultural fields, also serve as nesting sources of this honey bee (

Figure 9). Buildings continue to be the best alternative sources for hanging the nesting planks to attract the migratory swarms of this honey bee because host nesting sources are being quickly removed from this area [

7].

3.3. Trials for Domestication and Conservation

For the artificial devices, this honey bee had a strong choice. Out of the four treatment trials, three treatment trials were completely ignored/ rejected by the migratory swarms of this honey bee (

Table 3). These included, i) beeswax treated planks tied loosely with the building eaves; ii) untreated planks tied loosely with the building eaves; and iii) untreated planks tied tightly with the building eaves. Only the beeswax treated planks tied tightly with the building eaves were accepted (

Figure 10, 11). However, only 29 of the 40 trials were occupied indicating that the occupation level of provided planks remained mediocre (58 percent). After remaining there from October to May, the nested colonies eventually left. It appeared that two criteria were combined to choose the planks. They were; i) the hanging plank’s under side had beeswax on it, and ii) the plank was perfectly aligned with the building projection’s surface.

Figures in the parentheses represent percent values

3.4. Occupation and Re-Occupation Indices

Interestingly, both the occupation and re-occupation indexes for Site-1 and Site-4 were equal to one. This honey bee completely occupied and re-occupied the planks that were hung on these sites year after year (

Table 4). Site-2′s occupation index was equal to one, meaning that it was used in the same year as provided, however, its re-occupation index was 0.5, only nine of the 18 times availability were used. Planks hung at Site-3 had an occupation index equal to 0.5; they were used in second year of their availability. However, their re-occupation index was 0.29, only five times out of 17 times they were available, they were used.

Similarly, Site-5′s planks had an occupation index of 0.33 (occupied in the third year of availability) but a significantly higher re-occupation index of 0.5 (used eight times out of 16 times of availability), suggesting that this honey bee found this site to be moderately acceptable. With a 0.2 occupation index (used in the fifth year after becoming available), and a re-occupation index (used only 3 times despite being available 14 times), the nesting plank hung at Site-6 demonstrated very little attraction to the giant honey bee swarms (

Table 4). These findings suggest that this honey bee did not find all of the nesting locations to be equally attractive, and that it preferred some over others based on the availability of nesting locations.

3.5. Trials for Handling and Taming of Colonies

3.5.1. Pre-Handling Disturbance Trials

The aggressive response of the test colonies under the two types of trials is displayed in

Table 5. Colonies that had not been disturbed before had exhibited a significantly higher level of aggression than those that had not been disturbed often (p<0.0001, t-test value= 7.56; df=48,

Table 5).

The often disturbed colonies appeared to begin disregarding/ignoring the surrounding disturbance and progressively became quite/calm for the visitors. In contrast, the undisturbed colonies exhibited a very high degree of aggressiveness even after 80 days of their settlement if they were not frequently disturbed, as their aggressive response remained exceptionally high (

Table 5). The difference in aggressiveness between days was highly significant (F

4,25 = ∞, ANOVA,

Table 5).

3.5.2. Pre-Handling Taming Trials

The colonies of the giant honey bee exposed to four different types of taming treatments responded differently (

Table 6).

Both previously disturbed and undisturbed colonies’ level of aggression were affected by these taming trials in the same way (p>0. 05, t-test value=0. 238, df=38,

Table 6). However, in both previously disturbed as well as undisturbed colonies, the difference between taming trials was highly significant (F

3,16= ∞, ANOVA, Table 12). Undisturbed colonies treated with smoke showed marginally greater level of aggression than those treated with water. Colonies treated with smoke and water that had previously been disturbed, however, did not exhibit any different level of aggression. In actuality, these colonies were free of aggression. However, the sham-treated and control colonies, both undisturbed and disturbed, displayed a high level of aggression; the previously disturbed colonies’ aggression was unquestionably lower than that of the undisturbed colonies. This leads more credence to the previous findings that the giant honey bee’s aggression is reduced when the colonies are periodically disturbed. After being sprayed with water neither disturbed nor undisturbed colonies displayed any sign of aggression (

Table 6).

3.6. Utilization of the Attracted Giant Honey Bee for Honey and Beeswax Production, and for Live Studies

For the purpose of producing honey and beeswax from the enticing and tamed colonies of the giant honey bee (

A. dorsata), a non-destructive method of honey hunting was developed [

Figure 12]; and also for in-person research ([

7,

22];

Figure 14). To do this, the colonies were brought down and the honey portion removed. The honey then extracted by hand squeezing it. This honey bee produced 6.58 ± 0.53 kg (mean ± s.d.; N=10) honey and 1.52 ± 0.18 kg (mean ± s.d.; N=10) beeswax per colony on average (

Table 7). The colonies attracted to the wooden planks also proved a convenient resource for conducting live research on the colonies of this honey bee that would otherwise be extremely challenging to reach ([

7,

22];

Figure 14]).

4. Discussion

The giant honey bee (A.

dorsata) immigrates in the Northwestern region of India during October/November, where it remains and breeds throughout the winter and spring before emigrating in summer [

7]. This honey bee builds nest on the eves of tall buildings and trees [

22]. Human-engineered activities have caused the loss of numerous honey bee host trees in this area in recent years [

7]. Because of its potential for producing honey and beeswax (

Table 7) and pollinating the local crops (

Table 2), it is now crucial to restore its nesting resources in order to support its early conservation. This research has attempted to do so.

Numerous attempts have been made in the past, primarily in the realm of rafter beekeeping, focusing on the giant honey bee for harvesting its honey potential [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. The majority of these attempts involved the installation of rafters on trees to serve as nesting sources of this honey bee. However, in areas where the natural nesting resources (tall trees) have been significantly affected by human activities [

7], this approach has become ineffective. The regeneration or restoration of these could take an extended period. During this time, tall buildings, which have become common in recent years, can offer potential nesting sites. The new strategy could prove crucial for this honey bee in terms of domestication, conservation, and production of honey and beeswax. It will also ensure the sustainability of pollination services in its natural habitat.

This study reveals that not all nesting sites are equally appealing to this honey bee, and given the choice, it tends to prefer certain sites over others. Therefore, initial efforts should be directed towards the identification of preferred sites for attracting the migratory swarms prior to the commencement of large-scale beekeeping operations with this honey bee.

Even though this honey bee is used in rafter beekeeping, there was very little work done to domesticate it [

5,

31], and no attempts were made to attract and tame the colonies. This study offers methods for i) attracting the migratory swarms of this honey bee to the nesting planks suspended from tall buildings projections; and ii) taming the colonies to reduce their aggressive behavior, approach them closely and handle them gently for non-destructive honey harvesting, and scientific research on the live colonies.

The information produced by this investigation is novel for science. This will open a new era of beekeeping with the giant honey bee for honey and beeswax production, and the sustainability of pollination services in the areas of its natural habitat.

5. Conclusion

The giant honey bee (A. dorsata) has enormous potential for producing honey and beeswax, as well as for pollinating crops in area of its natural habitat. Human activity has significantly diminished its nesting sources. Its preservation is now vitally important. In order to attract and domesticate the swarms of this honey bee, artificial wooden planks were devised, fabricated and tested. Additionally, taming and non-destructive honey harvesting methods were also investigated. This study will serve as a manual for the conservation of giant honey for the production of honey and beeswax as well as the sustainability of pollination services in areas of its natural habitats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition were all done by R.C.Sihag.

Funding

This research was funded by the Government of Haryana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

By request from the author.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses gratitude to the successive Heads, Department of Zoology, for providing the facilities that were required. Additionally deserving of gratitude are beekeeping staff members, Dalbir Singh, Jhokhu Lal, Jagmal Singh and J.P. Narain, for helping with the field work for this study. This study was completed as part of the research projects, C(a)-Zoo-2- Plan (Agri.), C(a)-Zoo-2- Non-Plan (Agri.), and B (IV)- Non-Plan (Agri.) supported by the State Government of Haryana.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Crane, E.; Luyen, V.V.; Mulder, V.; Ta, T.C. Traditional management system for Apis dorsata in submerged forests in southern Vietnam and central Kalimantan. Bee Wld. 1993, 74, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, D.R.; Sihag, R.C.; Yadav, P.R. Diversity, abundance and foraging activity of insect pollinators of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) at Hisar (India). Indian Bee J. 1994, 56, 172–78. [Google Scholar]

- Priti; Sihag, R.C. Diversity, visitation frequency, foraging behaviour and pollinating efficiency of insect pollinators visiting cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis cv. Hazipur Local) blossoms. Indian Bee J. 1997, 59, 230-237.

- Chaudhary, N.; Sihag, R.C. Diversity, foraging behavior and foraging efficiency of different pollinators visiting onion (Allium cepa L.) blossoms. J. Apiculture 2003, 18, 103–108.

- Priti; Sihag, R.C. Diversity, visitation frequency, foraging behaviour and pollinating efficiency of different insect pollinators visiting coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) blossoms. Asian Bee J. 1999, 1, 36–42.

- Priti; Sihag, R.C. Diversity, visitation frequency, foraging behaviour and pollinating efficiency of different insect pollinators visiting fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) blossoms. Asian Bee J 2000, 2, 57–64.

- Sihag, R.C. Phenology of migration and decline in colony numbers, and crop hosts of giant honeybee (Apis dorsata F.) in semiarid environment of Northwest India. J. Insects 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, N.; Sihag, R.C. Melittophilous mode of pollination predominates in European plum (Prunus domestica L.) in the semi-arid environment of Northwest India. Asian J. Agric. Res. 2015, 9, 189-207. [CrossRef]

- Saini, Reena; Sihag, R.C. Abundance, foraging behavior and pollination efficiency of insects visiting the flowers of Aonla (Emblica officinalis). EUREKA: Life Sciences 2023, 2023, 40-56. [CrossRef]

- Priti; Sihag, R. C. Diversity, visitation frequency, foraging behaviour and pollinating efficiency of insect pollinators visiting carrot (Daucus carota L.var. HC-I) blossoms. Indian Bee J. 1998, 60, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Gahlawat, S. K.; Narwania, S. K.; Sihag, R. C.; Ombir. Studies on the diversity, abundance, activity duration and foraging behaviour of insect pollinators of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) at Hisar. J. Apiculture 2002, 17, 69–76.

- Gahlawat, S. K.; Narwania, S. K.; Ombir; Sihag, R. C. Pollination studies on Pracitrullus fistulosus at Hisar, India. Ecoprint 2002, 9, 1–6.

- Gahlawat, S. K.; Narwania, S. K.; Ombir; Sihag, R. C. Diversity, abundance, foraging rates and pollinating efficiency of insects visiting wanga (Cucumis melo ssp. melo) blossoms at Hisar (India). J. Apiculture 2003, 18, 29–36.

- Ahaiao, R. Methods to control migration by Apis dorsata colonies in Pakistan. Bee Wld. 1989, 70, 160–162. [Google Scholar]

- Mahindre, D.B. Developments in the management of Apis dorsata colonies. Bee Wld. 2000, 81, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 1Koeniger, N.; Koeniger, G. Observations and experiments on migration and dance communication of Apis dorsata in Sri Lanka. J. Apic. Res 1980, 19, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, G.; Reddy, C.C. Rates of swarming and absconding in the giant honey bee, Apis dorsata F, Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. (Anim. Sci.) 1989, 98, 425–430.

- Woyke, J.; Wilde, J.; Wilde, M. Swarming and migration of Apis dorsata and Apis laboriosa honey bees in India, Nepal and Bhutan. J. Apic. Sci. 2012, 56, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, J. B.; Mandal, C. K.; Shrestha, S. M.; Ahmad, F. The trend of the giant honeybee, Apis dorsata Fabricius colony migration in Chitwan, Nepal. The Wildlife 2002, 7, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel, S. Pokhrel, S. Climato-cyclic immigrations with declining populations of wild honeybee, Apis dorsata F. in Chitwan valley, Nepal. J. Agric. Environ 2010, 11, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, F. C.; Seeley, T. D. Colony migration in the tropical honey bee Apis dorsata F. (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Insect. Soc 1994, 41, 129–140.

- Sihag, R.C. Nesting behavior and nest site preferences of the giant honey bee (Apis dorsata F.) in the semi-arid environment of northwest India. J. Apic. Res 2017, 56, 452–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.R. Non-destructive method of honey hunting. Bee Wld 2005, 86, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldroyd, B.P.; Nanork, P. Conservation of Asian honey bees. Apidologie 2009, 40, 296–312. [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd, B.P.; Wongsiri, S. Asian honey bees. Biology, conservation, and human interactions. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. 2006.

- Strickland, S.S. 1982. Honey hunting by the Gurungs of Nepal. Bee Wld. 1982, 63, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, N. Q.; Chinh, P. H.; Thai, P. H.; Mulder, V. Rafter beekeeping with Apis dorsata: some factors affecting the occupation of rafters by bees. J. Apic. Res. 1997, 36, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, N. Q.; Chinh, P. H.; Ha, D. T. Socio-economic factors in traditional rafter beekeeping with Apis dorsata in Vietnam. Bee Wld. 2002, 83, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, C. and Jump, D.R. Rafter beekeeping in Cambodia with Apis dorsata. Bee Wld 2004, 85, 14–18. [CrossRef]

- Thakar, C.V. A preliminary note on hiving Apis dorsata colonies. Bee Wld. 1973, 54, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihag, R. C. Characterization of the pollinators of cultivated cruciferous and leguminous crops of sub-tropical, Hisar, India. Bee Wld. 1988, 69, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sihag, R.C.; Shivrana, S. Foraging behaviour and strategies of the flower visitors. In: Pollination Biology: Basic and Applied Principles (Ed.: R. C. Sihag). Rajendra Scientific Publishers, Hisar 1997; 53-73.

- Snedecor, G.W.; Cochran, W. G. Statistical Methods (6th Edn.). Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi 1967, 593p.

- https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ttest2/.

- https://www.statskingdom.com/180Anova1way.html.

Figure 1.

The multi-storey building of the College of Basic Sciences and Humanities, where

A. dorsata nested on various ceiling projections (Adapted from Sihag, 2017 [

22]).

Figure 1.

The multi-storey building of the College of Basic Sciences and Humanities, where

A. dorsata nested on various ceiling projections (Adapted from Sihag, 2017 [

22]).

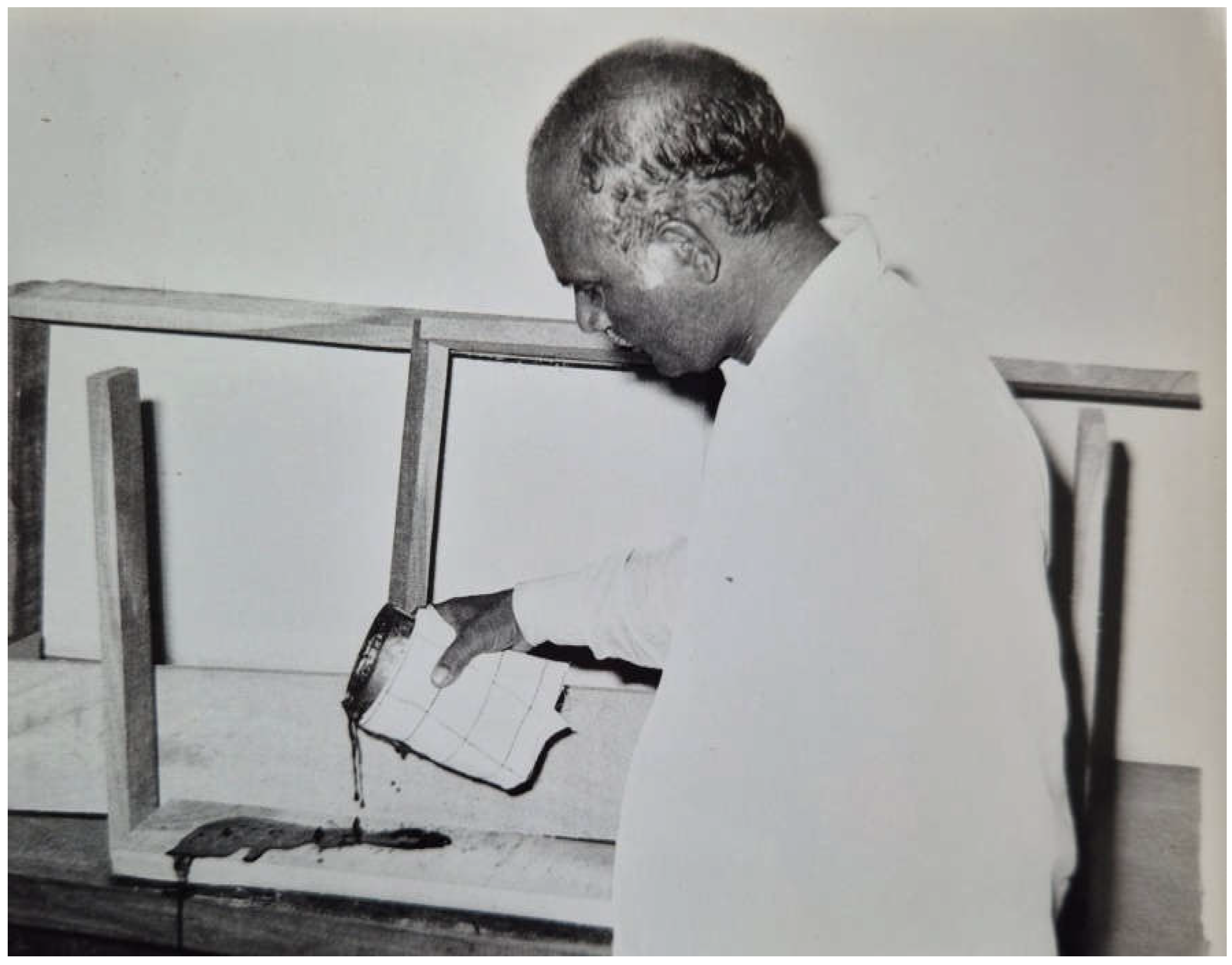

Figure 2.

Wooden planks used for the domestication of A. dorsata; molten beeswax is applied to the underside of the plank.

Figure 2.

Wooden planks used for the domestication of A. dorsata; molten beeswax is applied to the underside of the plank.

Figure 3.

A loosely tied wooden plank hung on the projection of the building with the help of iron wires.

Figure 3.

A loosely tied wooden plank hung on the projection of the building with the help of iron wires.

Figure 4.

A. dorsata foraging on rapeseed (

Brassica campestris) flowers for pollen and nectar; the forager always served as a pollinator by transferring pollen during each foraging visit [

32,

33].

Figure 4.

A. dorsata foraging on rapeseed (

Brassica campestris) flowers for pollen and nectar; the forager always served as a pollinator by transferring pollen during each foraging visit [

32,

33].

Figure 5.

A. dorsata foraging on lemon (

Citrus l

imon) flowers for pollen and nectar; the forager always served as a pollinator by transferring pollen during each foraging visit [

32,

33].

Figure 5.

A. dorsata foraging on lemon (

Citrus l

imon) flowers for pollen and nectar; the forager always served as a pollinator by transferring pollen during each foraging visit [

32,

33].

Figure 6.

A colony of A. dorsata nesting on the college building’s projection, which is roughly 15 m above the ground.

Figure 6.

A colony of A. dorsata nesting on the college building’s projection, which is roughly 15 m above the ground.

Figure 7.

Colonies of A. dorsata nesting on the water tower building, which is roughly 15 m above the ground.

Figure 7.

Colonies of A. dorsata nesting on the water tower building, which is roughly 15 m above the ground.

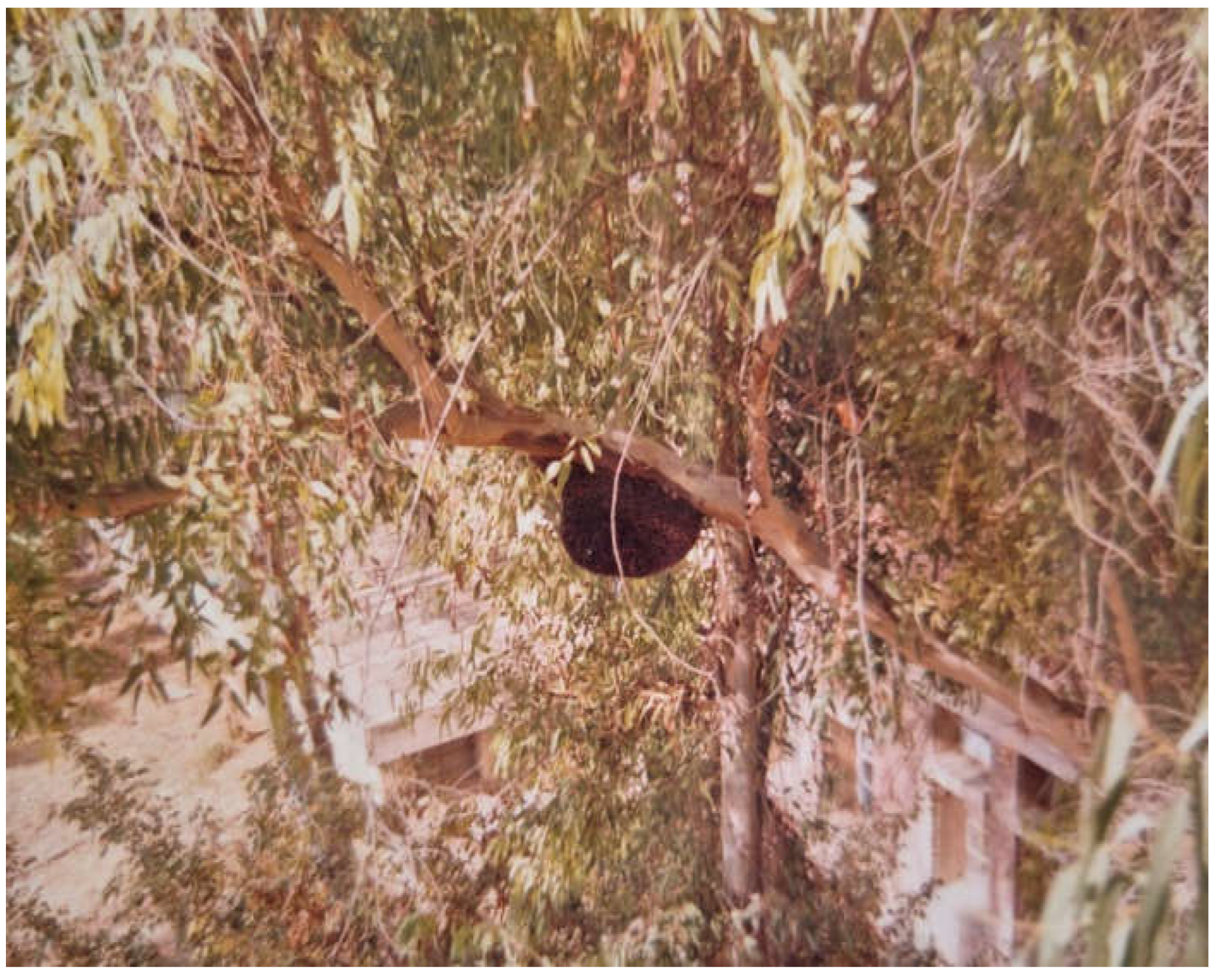

Figure 8.

A colony of A. dorsata nesting on a eucalyptus tree, which is roughly 5 m above the ground.

Figure 8.

A colony of A. dorsata nesting on a eucalyptus tree, which is roughly 5 m above the ground.

Figure 9.

A colony of A. dorsata nesting on a jujube tree which is roughly 5 m above the ground.

Figure 9.

A colony of A. dorsata nesting on a jujube tree which is roughly 5 m above the ground.

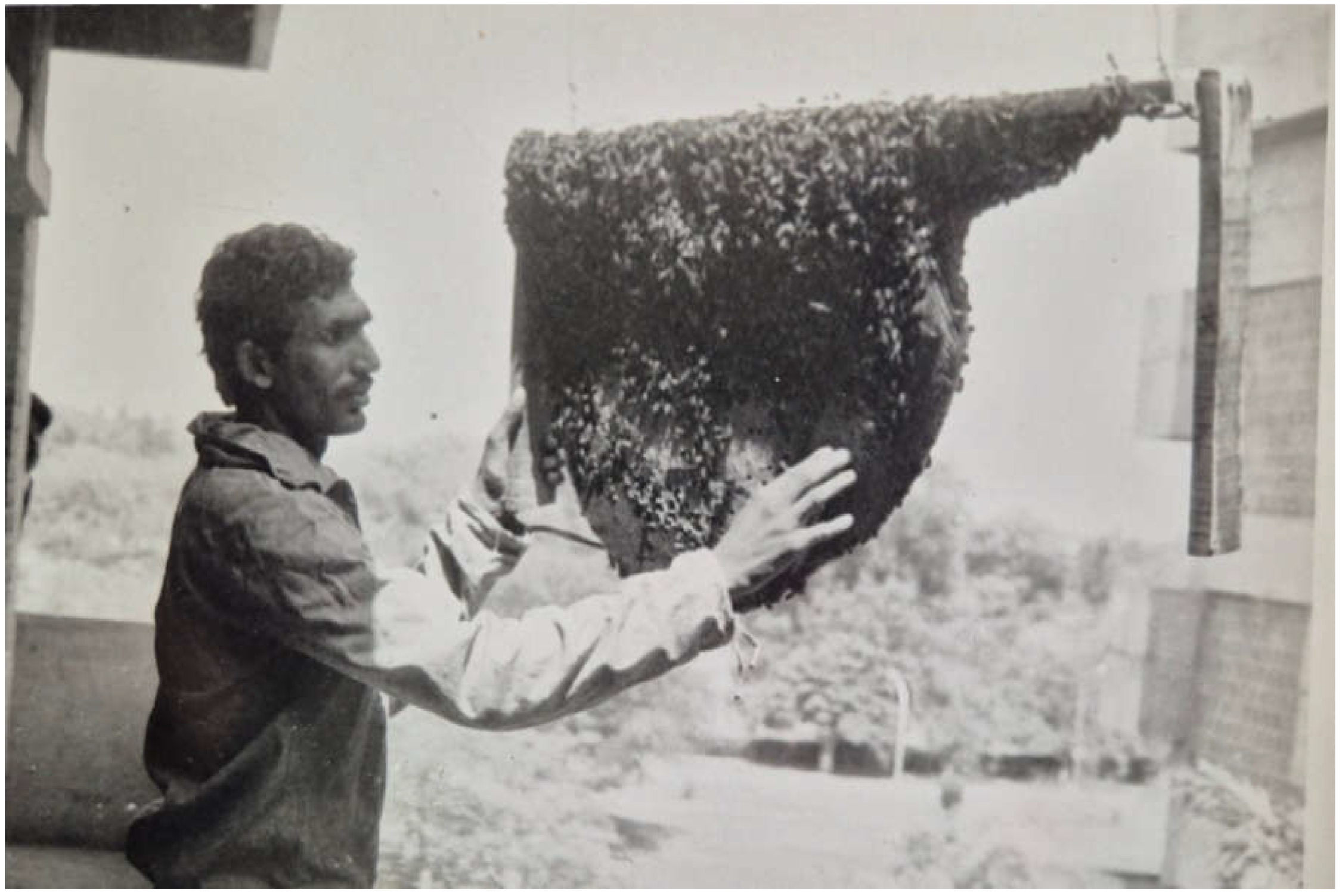

Figure 10.

A giant honey bee colony that built its nest on a beeswax-treated wooden plank. The colony has been brought down to conduct various experiments by loosening the plank’s wire.

Figure 10.

A giant honey bee colony that built its nest on a beeswax-treated wooden plank. The colony has been brought down to conduct various experiments by loosening the plank’s wire.

Figure 11.

An abandoned giant honey bee comb constructed on a wooden plank that was tightly tied with the building projection.

Figure 11.

An abandoned giant honey bee comb constructed on a wooden plank that was tightly tied with the building projection.

Figure 12.

An abandoned comb of the giant honey bee A. dorsata, which was raised on the wooden plank; the white upper portion shows the honey comb; sealed brood is located in the center, and queen cells are located at the lower end.

Figure 12.

An abandoned comb of the giant honey bee A. dorsata, which was raised on the wooden plank; the white upper portion shows the honey comb; sealed brood is located in the center, and queen cells are located at the lower end.

Figure 13.

A comb of the giant honey bee, A. dorsata; the honey portion was excised from the upper left portion. The deserted comb makes an excellent source of beeswax, and can be used for research.

Figure 13.

A comb of the giant honey bee, A. dorsata; the honey portion was excised from the upper left portion. The deserted comb makes an excellent source of beeswax, and can be used for research.

Figure 14.

A live colony of the giant honey bee, A. dorsata. The honey portion was excised following the taming trials, and the colony was readily manageable for live research.

Figure 14.

A live colony of the giant honey bee, A. dorsata. The honey portion was excised following the taming trials, and the colony was readily manageable for live research.

Table 1.

Level of aggression in the giant honey bee caused by different taming trials.

Table 1.

Level of aggression in the giant honey bee caused by different taming trials.

| Serial. Number |

Degree of Aggression |

Aggression Score |

| 1 |

Spontaneous and very high aggression [Hundreds of bees attacked the person handling the colony] |

5 |

| 2 |

Spontaneous and high aggression [Two to three hundred bees attacked the person handling the colony] |

3 |

| 3 |

Delayed and mild aggression [Fewer than 100 (approximately 40–80) bees tried to attack the person handling the colony] |

1 |

| 4 |

No aggression was observed [No bee attacks were observed] |

0 |

Table 2.

The various crops pollinated by the giant honey bee (A. dorsata) in Hisar (India).

Table 2.

The various crops pollinated by the giant honey bee (A. dorsata) in Hisar (India).

| No. |

Crop (Common Name) |

Crop (Botanical Name) |

Family |

Flowering Months |

Visit for |

| 1 |

Onion |

Allium cepa L. |

Apiaceae |

Mar.-Apr. |

P, N |

| 2 |

Sun flower |

Helianthus annuus L. |

Asteraceae |

Mar.-May |

P, N |

| 3 |

Cauliflower |

Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis

|

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 4 |

Chinese cabbage |

Brassica chinensis L.D. |

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 5 |

Edible leafy mustard |

Brassica juncea Czern. & Coss |

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 6 |

Radish |

Raphanus sativus L. |

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 7 |

Rape |

Brassica napus L. |

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 8 |

Salad rocket |

Eruca vesicaria ssp. sativa Mills. |

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 9 |

Turnip |

Brassica rapa L. |

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 10 |

Toria |

Brassica campestris L. var. toria

|

Brassicaceae |

Dec.-Feb |

P, N |

| 11 |

Apple gourd |

Praecitrullus fistulosus (Stocks) Pangalo |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 12 |

Bath sponge |

Luffa cylindrica L. |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 13 |

Bitter gourd |

Momordica charantia L. |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 14 |

Bottle gourd |

Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl.) |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 15 |

Cucumber |

Cucumis sativus L. |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 16 |

Muskmelon |

Cucumis melo L. |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 17 |

Pumpkin |

Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poir. |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 18 |

Ribbed gourd |

Luffa acutangula (L.) Roxb. |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 19 |

Summer squash |

Cucurbita pepo L. |

Cucurbitaceae |

Mar.-Nov. |

P, N |

| 20 |

Pigeon pea |

Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp. |

Fabaceae |

Sep.-Oct. |

P, N |

| 21 |

Chick pea |

Cicer arietinum L. |

Fabaceae |

Dec.-Feb. |

P, N |

| 22 |

Berseem/clover |

Trifolium alexandrinum L. |

Fabaceae |

Mar.-May |

P, N |

| 23 |

Lucern |

Medicago sativa L. |

Fabaceae |

Mar.-Oct. |

P, N |

| 24 |

Fenugreek |

Trigonella foenum-graecum L. |

Fabaceae |

Feb.-Mar. |

P, N |

| 25 |

Guava |

Psidium guajava L. |

Myrtaceae |

Apr.-May |

P, N |

| 26 |

Amla |

Phyllanthus emblica |

Phyllanthaceae |

Apr.-May |

P |

| 27 |

Pearl millet |

Pennisetum glaucum |

Poaceae |

Aug.-Sep |

P |

| 28 |

Peach |

Prunus persica (L.) Stokes |

Rosaceae |

March |

P, N |

| 29 |

Kinnow |

Citrus nobilis × Citrus deliciosa

|

Rutaceae |

Feb.-Mar. |

P, N |

| 30 |

Lemon |

Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. |

Rutaceae |

Feb.-Mar. |

P, N |

| 31 |

Coriander |

Coriandrum sativum L. |

Umbelliferae |

Feb.-Mar. |

P |

| 32 |

Fennel |

Foeniculum vulgare L. |

Umbelliferae |

Feb.-Mar. |

P |

Table 3.

Number of wooden planks occupied by migratory swarms of giant honey bee under various treatments (1984-93).

Table 3.

Number of wooden planks occupied by migratory swarms of giant honey bee under various treatments (1984-93).

| Hanging State of Wooden Planks |

Treatment |

| Planks Traeted with Wax |

Untreated Planks |

| Tightly Hung |

29 (58) |

0 (0) |

| Loosely Hung |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Table 4.

Occupancy level of various available nesting planks that were made available over the years to attract migratory swarms of the giant honey bee.

Table 4.

Occupancy level of various available nesting planks that were made available over the years to attract migratory swarms of the giant honey bee.

| Year |

Nesting Plank Number and Occupation Status |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| 1994 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

| 1995 |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

| 1996 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 1997 |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 1998 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

| 1999 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

| 2000 |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 2001 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

| 2002 |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 2003 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 2005 |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

| 2006 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 2007 |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 2008 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

| 2009 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

| 2010 |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 2011 |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

| 2012 |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

| Occupation Index |

1 |

1 |

0.31 |

1 |

0.47 |

0.21 |

| Re-occupation index |

1 |

0.5 |

0.05 |

1 |

0.22 |

0 |

Table 5.

Aggressive response of A. dorsata test colonies under two trial types after various durations of their settlements and pre-disturbance status.

Table 5.

Aggressive response of A. dorsata test colonies under two trial types after various durations of their settlements and pre-disturbance status.

| No. |

Days After Settlement the Handling Was Done |

Disturbed Colonies* |

Undisturbed Colonies* |

| 1 |

10 (1st) |

5,5,5,5,5 |

5,5,5,5,5 |

| 2 |

20 (2nd) |

4,4,4,4,4 |

5,5,5,5,5 |

| 3 |

30 (3rd) |

3,3,3,3,3 |

5,5,5,5,5 |

| 4 |

40 (4th) |

2,2,2,2,2 |

5,5,5,5,5 |

| 5 |

50 (5th) |

2,2,2,2,2 |

5,5,5,5,5 |

| |

Mean±s.d. |

3.2 ±1.166 |

5.0±0.0* |

Table 6.

Aggressive response of two types of A. dorsata test colonies subjected to four kinds of pre-handling treatments.

Table 6.

Aggressive response of two types of A. dorsata test colonies subjected to four kinds of pre-handling treatments.

| S. No. |

Colony Status |

Pre-Handling Treatment |

| Water |

Smoke |

Sham |

Control |

Average |

| 1 |

Undisturbed |

0,0,0,0,0 |

1,1,1,1,1 |

4,4,4,4,4 |

5,5,5,5,5 |

2.5 |

| 2 |

Periodically disturbed |

0,0,0,0,0 |

0,0,0,0,0 |

3,3,3,3,3 |

4,4,4,4,4 |

1.75 |

| Average |

0 |

0.5 |

3.5 |

4.5 |

|

Table 7.

Yearly production of honey and beeswax by the giant honey bee (A. dorsata).

Table 7.

Yearly production of honey and beeswax by the giant honey bee (A. dorsata).

| Colony. No. |

Honey Production (kg) |

Wax Production (kg) |

| 1 |

6.8 |

1.5 |

| 2 |

7.2 |

1.6 |

| 3 |

5.8 |

1.2 |

| 4 |

6.4 |

1.7 |

| 5 |

6.3 |

1.6 |

| 6 |

5.9 |

1.5 |

| 7 |

7.1 |

1.8 |

| 8 |

6.2 |

1.4 |

| 9 |

7.5 |

1.6 |

| 10 |

6.6 |

1.3 |

| Mean |

6.58 |

1.52 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.53 |

0.18 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).