Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

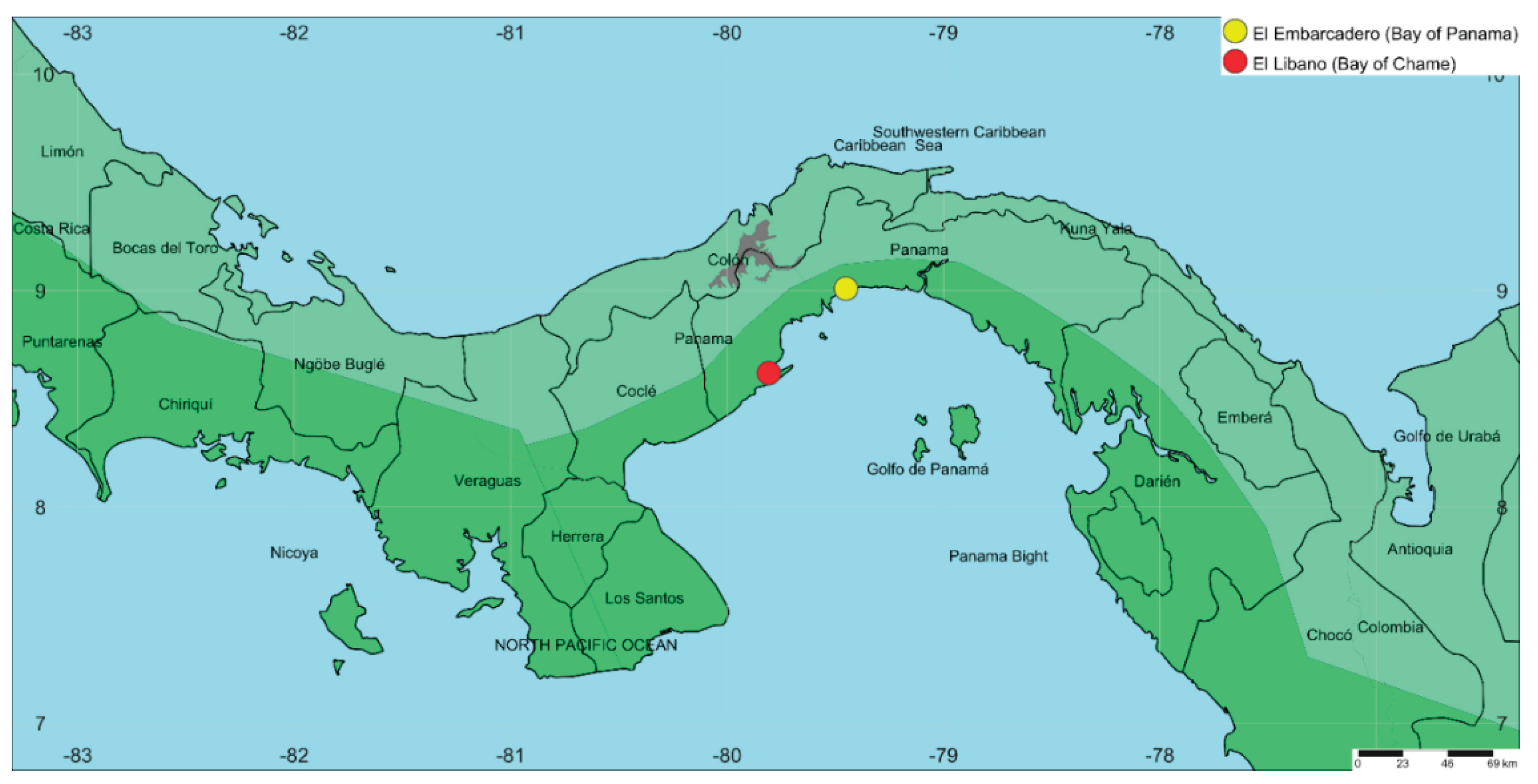

2.1. Study area

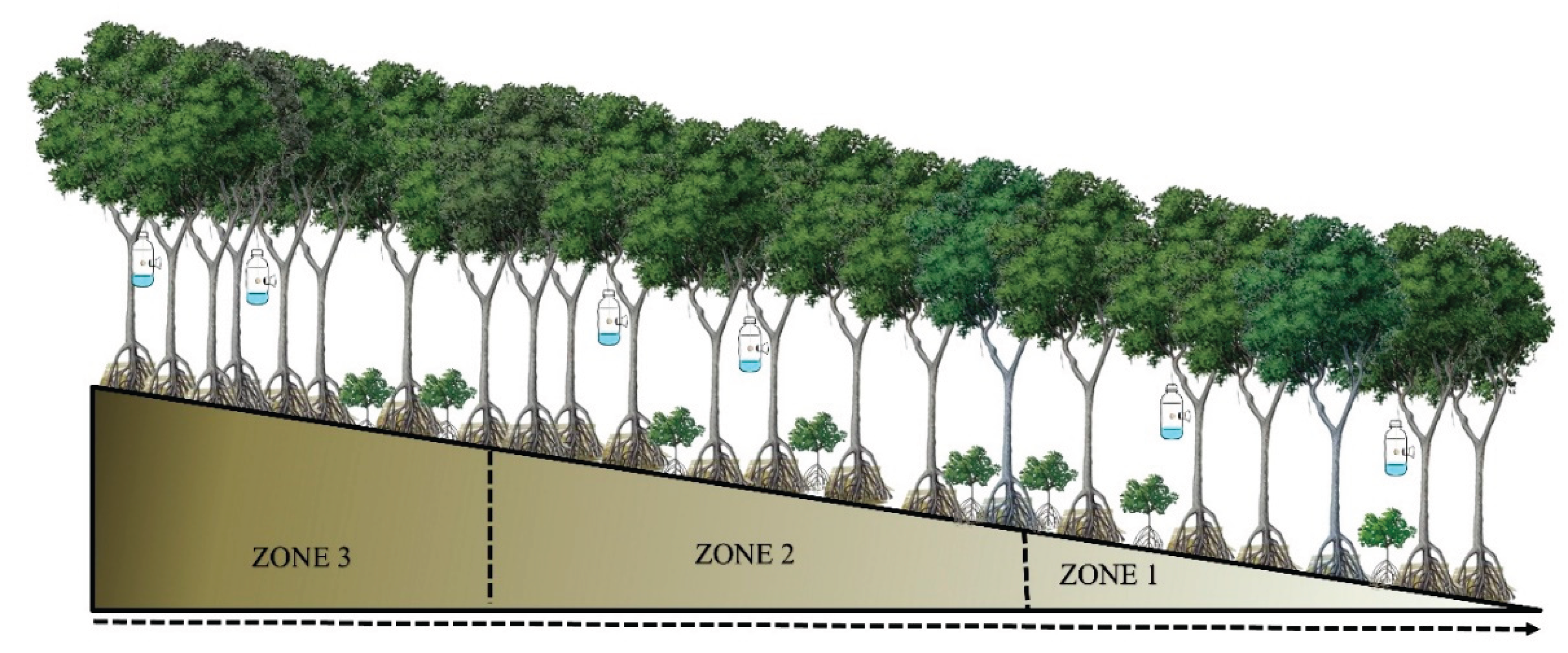

2.2. Sampling of Orchid Bees (Euglossini)

2.3. Data Analysis

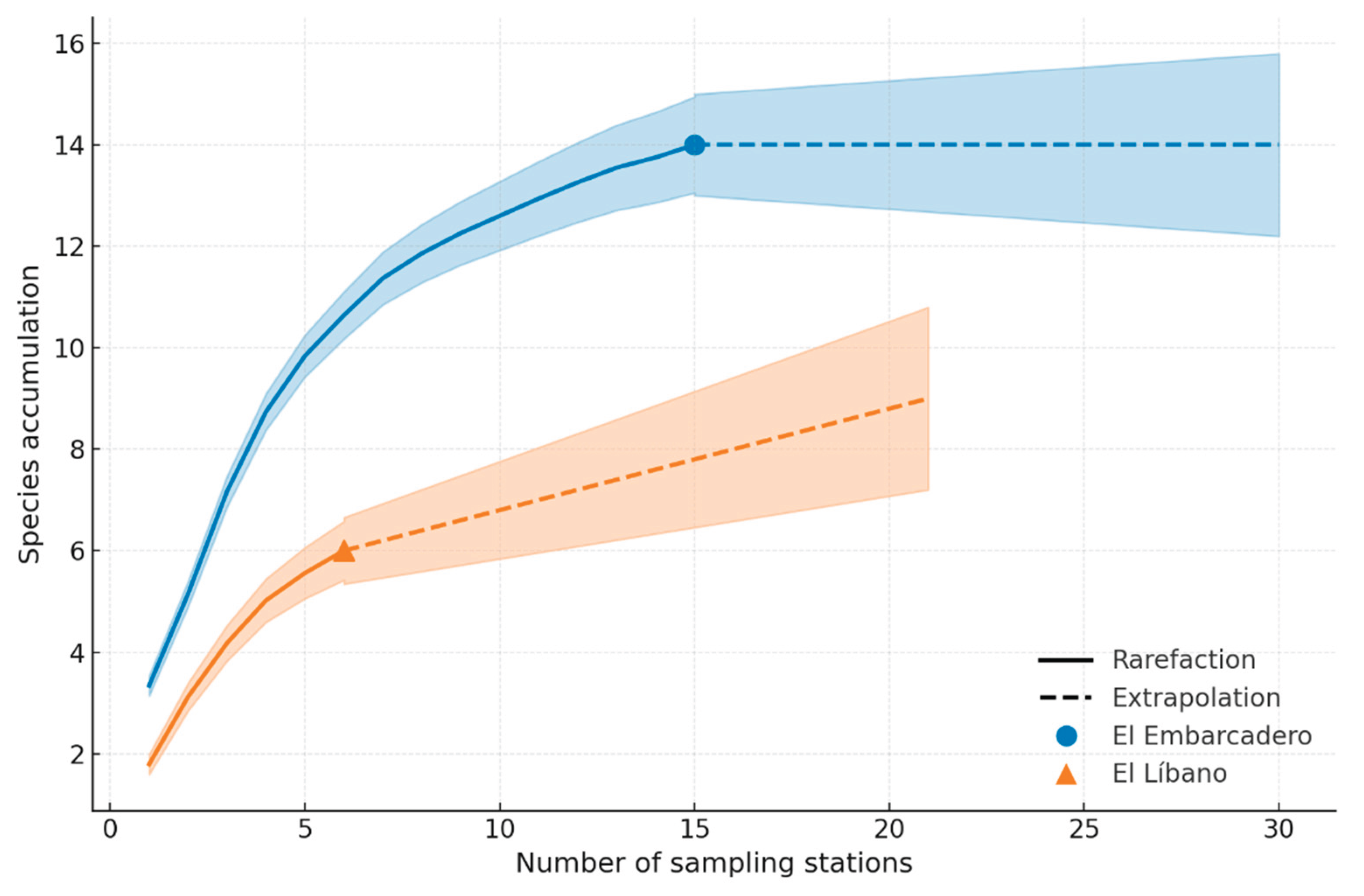

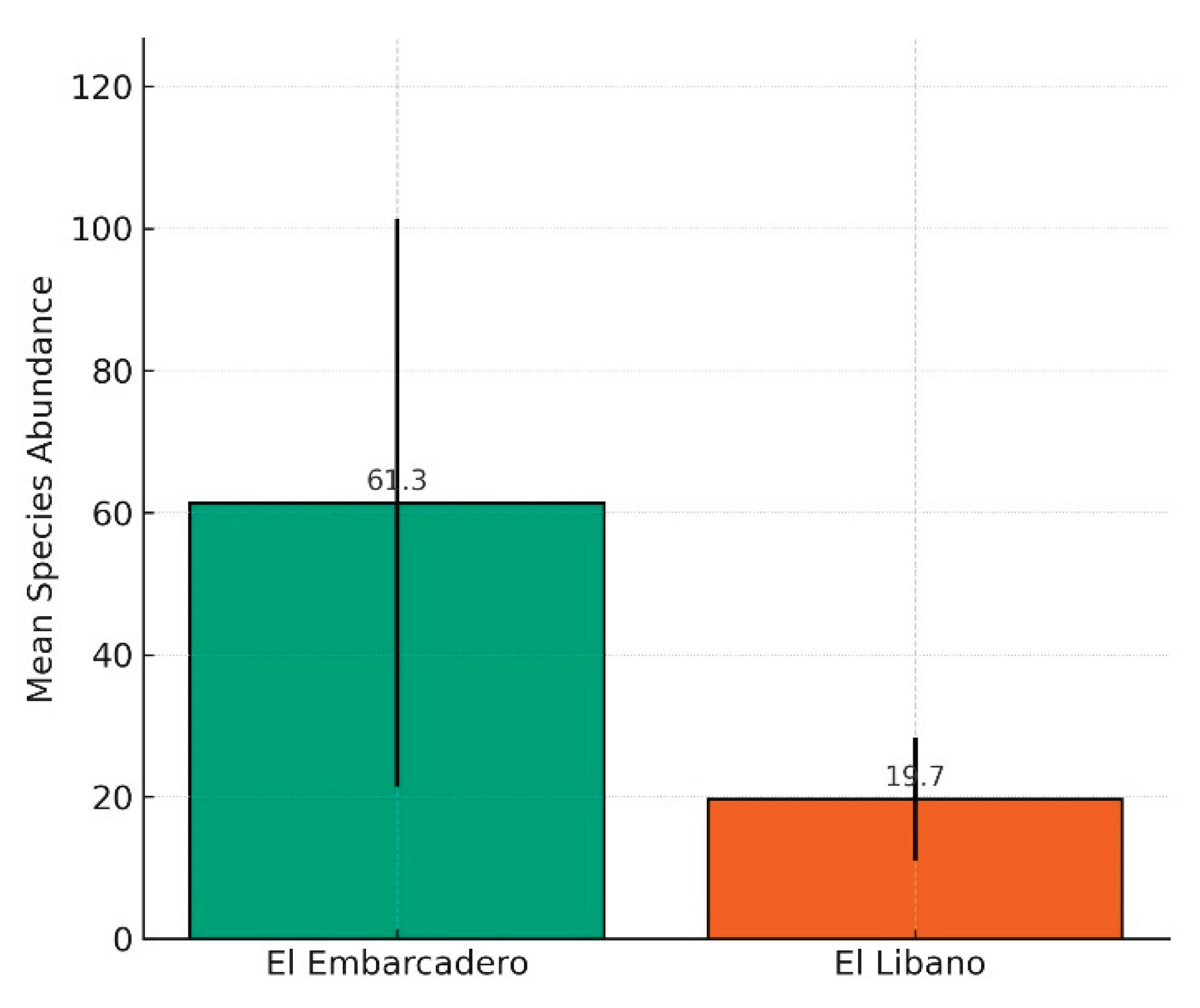

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanson, P. E., & Gauld, I. D. Hymenoptera de la región neotropical. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 2006, 77, 1–994.

- Roubik, W. D., & Hanson, P. E. Abejas de orquídeas de la América tropical: Biología y guía de campo. 2004. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio).

- Nemésio, A., & Silveira, F. A. Diversity and distribution of orchid bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) with a revised checklist of species. Neotropical Entomology 2007, 36(6), 874–888. [CrossRef]

- Engel, M. S. The first fossil Euglossa and phylogeny of orchid bees (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Euglossini). American Museum Novitates 1999, 3272, 1–14.

- Hinojosa-Díaz, I. A., & Engel, M. S. A checklist of the orchid bees of Nicaragua (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Euglossini). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 2012, 85(2), 135–144. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Ledezma, K. Y., Santos-Murgas, A., González, P., Gómez, I. Y., & Barrios-Vargas, A. Diversidad alpha y beta de abejas Euglossini (Hymenoptera: Apidae) en el dosel y sotobosque del Cerro Turega, provincia de Coclé, Panamá. Tecnociencia 2020, 22(2), 205–225. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Novelo, E., Meléndez R. V., Delfín, G. H., & Ayala, R. Abejas silvestres como bioindicadores en el Neotrópico. Agroecosistemas Tropicales y Subtropicales 2009, 10(1), 1–13.

- Cane, J. H. Habitat fragmentation and native bees: A premature verdict? Conservation Ecology 2001, 5(1), 3. http://www.consecol.org/vol5/iss1/art3/.

- Ramos, M., Pérez, J., & Torres, L. Impacto del desarrollo urbano en la calidad del agua de la Bahía de Panamá. Revista Panameña de Ciencias Ambientales 2020, 15(2), 45–60.

- Guzmán, H., & Vega, A. Evaluación de ecosistemas costeros en Panamá: Manglares y áreas protegidas. 2019. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

- Brosi, B. J. The effects of forest fragmentation on Euglossine bee communities (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Euglossini). Biological Conservation 2009, 142(2), 414–423. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayo, F., & Wyckhuys, K. A. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biological Conservation 2019, 232, 8–27. [CrossRef]

- Somejima, H., Markuzi, M., Nagamitsu, T., & Nakasizuka, T. The effects of human disturbance on a stingless bee community in a tropical rainforest. Biological Conservation 2004, 120, 577–587. [CrossRef]

- Autoridad del Canal de Panamá. Estado ecológico y biodiversidad de la cuenca del Canal de Panamá. 2022. Autoridad del Canal de Panamá.

- Ramsar. Ficha informativa sobre los Humedales de Importancia Internacional: Bahía de Panamá. 2021. Convención Ramsar.

- Pérez-Buitrago, N., Mojica-Candela, L. J., & Agudelo-Martínez, J. C. Variación estacional de abejas euglosinas (Apidae: Euglossini) en el norte de la Orinoquia colombiana. Revista De La Academia Colombiana De Ciencias Exactas, Físicas Y Naturales 2022, 46(179), 470-481. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2023.

- Rojas, B., Vásquez, O., Santos-Murgas, A., Cobos, R., & Gómez-Robles, I. Y. Abejas de las orquídeas como bioindicadores del estado de conservación de un bosque. Manglar 2022, 19(3), 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Urias, A., Moya-Raygoza, G., & Vásquez-Bolaños, M. Effects of urbanization and floral diversity on the bee community in a tropical dry forest. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 2025, 98, 47–68. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T. C., Cordeiro, G. D., Freitas, B. M., Saraiva, A. M., & Imperatriz-Fonseca, V. L. The dependence of crops for pollinators and the economic value of pollination in Brazil. Journal of Economic Entomology 2017, 108(3), 849–857. [CrossRef]

- Jaffé, R., Pope, N., Carvalho, A. T., Maia, U. M., Blochtein, B., de Carvalho, C. A. L., & Imperatriz-Fonseca, V. L. Landscape genomics to the rescue of a tropical bee threatened by habitat loss and climate change. Evolutionary Applications 2019, 12(6), 1164–1177. [CrossRef]

| Costa Sur | Don Bosco | El Embarcadero | |

| Richness | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| Abundance | 70 | 23 | 226 |

| Site/Species | Zones | Total/ Site | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Costa Sur | 10 | 43 | 17 | 70 |

| E. cognata | 4 | 4 | ||

| E. cybelia | 1 | 9 | 10 | |

| E. dressleri | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| E. imperialis | 6 | 6 | ||

| E. nigrita | 27 | 16 | 43 | |

| E. smaragdina | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Don Bosco | 15 | 3 | 5 | 23 |

| E. cybelia | 1 | 1 | ||

| E. dressleri | 1 | 1 | ||

| E. nigrita | 14 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| E. smaragdina | 1 | 1 | ||

| El Embarcadero | 63 | 78 | 85 | 226 |

| E. allosticta | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| E. cybelia | 1 | 1 | ||

| E. disimula | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| E. dressleri | 1 | 7 | 8 | |

| E. hemichlora | 5 | 5 | 10 | |

| E. imperialis | 11 | 19 | 30 | |

| E. nigrita | 57 | 49 | 50 | 156 |

| E. smaragdina | 4 | 10 | 14 | |

| E. tridentata | 2 | 2 | ||

| Total | 88 | 124 | 107 | 319 |

| Orchid bee species | El Embarcadero (Bay of Panama) |

El Líbano (Bay of Chame) |

|---|---|---|

| Euglossa allosticta Moure, 1969 | x | - |

| Euglossa deceptrix Moure, 1968 | x | x |

| Euglossa imperialis Cockerell, 1922 | - | x |

| Euglossa disimula Dressler, 1978 | x | - |

| Euglossa dodsoni Moure, 1965 | x | - |

| Euglossa hemichlora Cockerell, 1917 | x | - |

| Euglossa heterosticta Moure, 1968 | x | - |

| Euglossa tridentata Moure, 1970 | x | - |

| Euglossa variabilis Friese, 1899 | x | x |

| Eulaema nigrita Lepeletier, 1841 | x | x |

| Eulaema meriana (Olivier, 1789) | - | x |

| Exaerete smaragdina (Guérin-Méneville, 1845) | - | x |

| x: present, -: absent. |

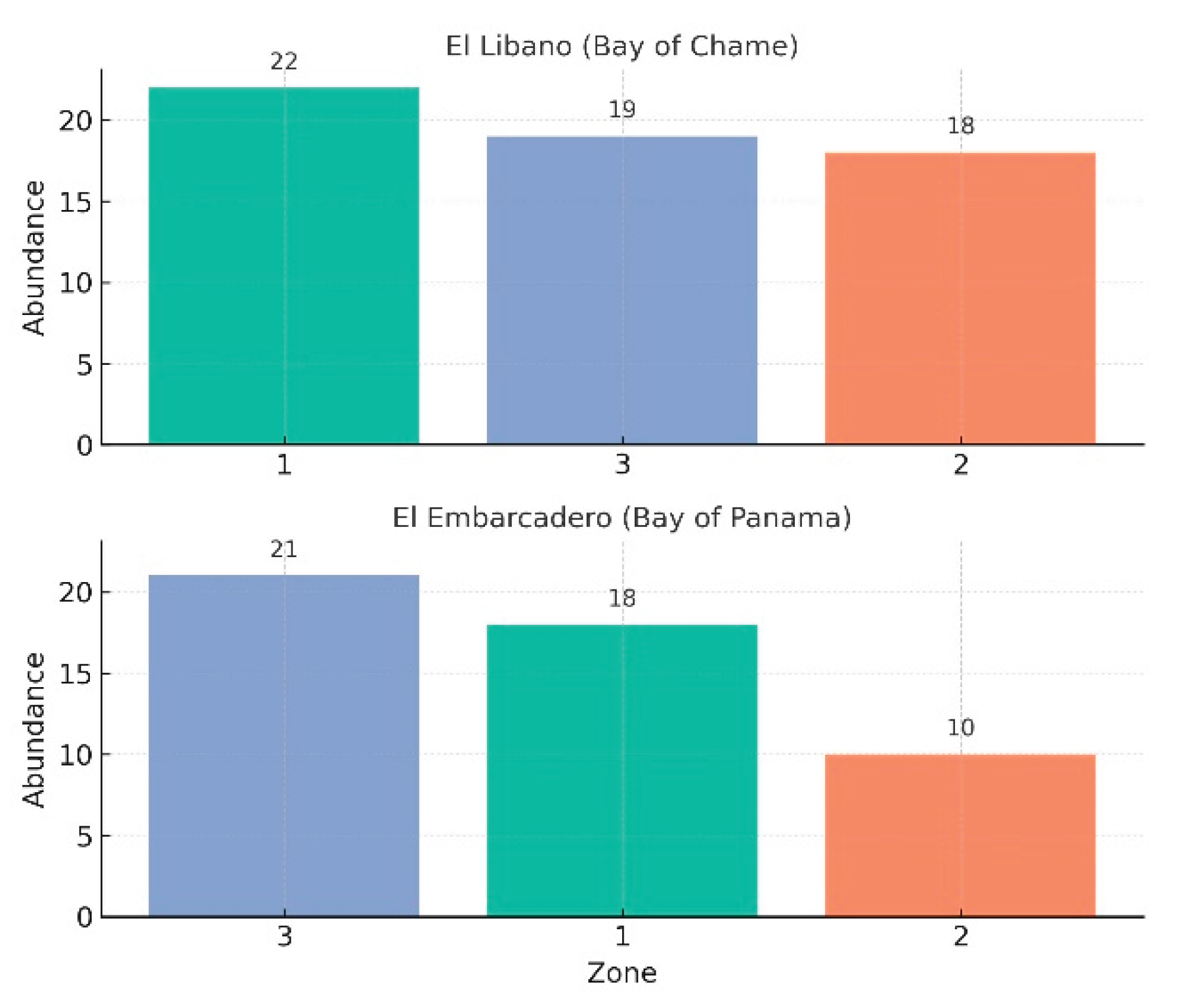

| Alpha diversity indices | El Líbano (Bay of Chame) | El Embarcadero (Bay of Panamá) |

| Richness | 6 | 9 |

| Abundance | 59 | 49 |

| Shannon | 1.014 | 1.863 |

| Gini- Simpson | 0.5136 | 0.8038 |

| Inverse Simpson Index | 2.056 | 5.098 |

| Fisher- Alpha | 1.670 | 3.236 |

| Berger- Parker | 0.6610 | 0.3061 |

| Pielou's Evenness | 0.5660 | 0.8478 |

| E-evenness | 0.4595 | 0.7157 |

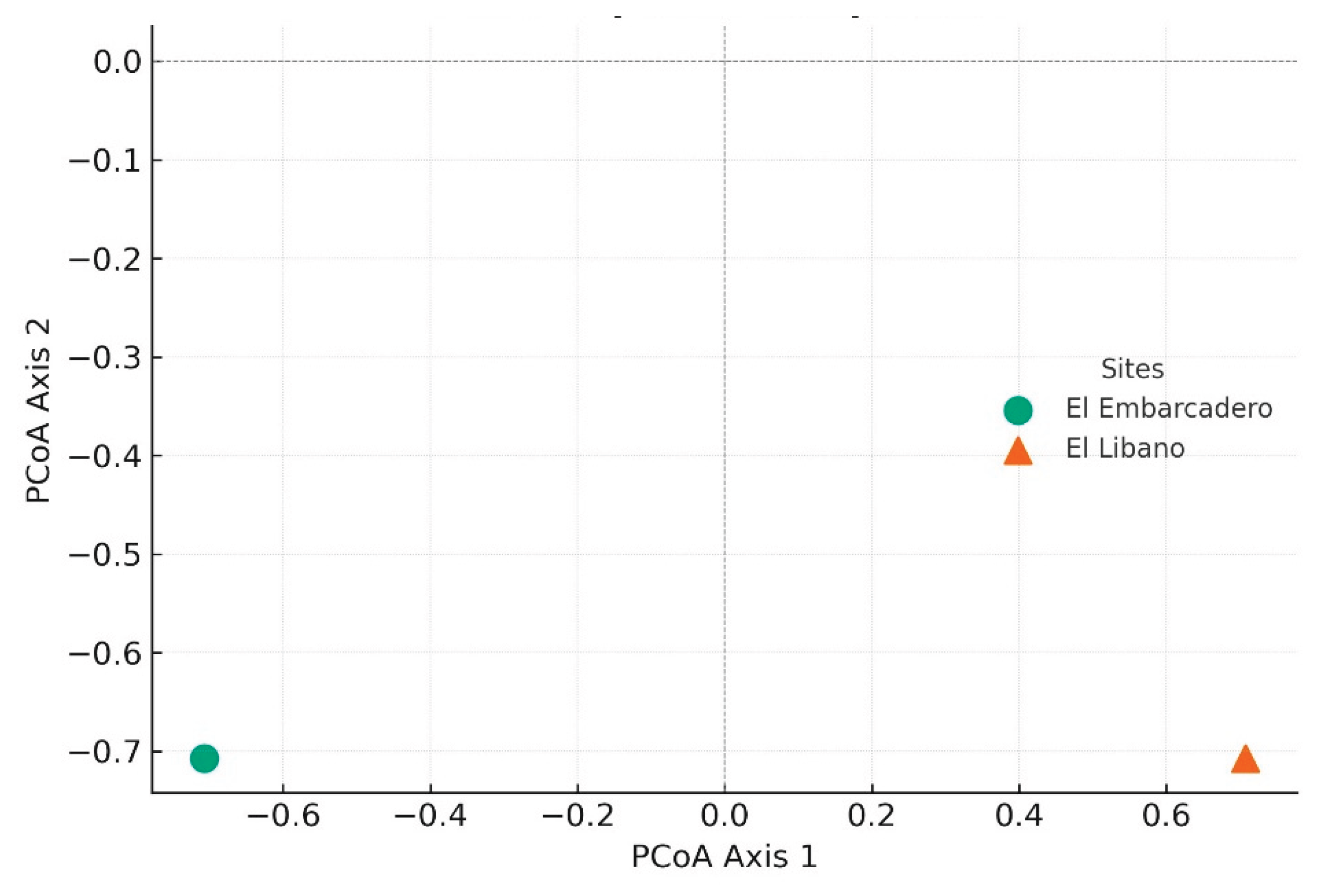

| Sampling sites | El Líbano (Bay of Chame) | Beta diversity indices |

| El Embarcadero (Bay of Panamá) | 0.7407 | Bray- Curtis |

| El Embarcadero (Bay of Panamá) | 0.75 | Jaccard |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).