1. Introduction

The Red supergiant (RSG) stage occurs after the Main sequence (MS) of massive stars between ∼9-30

. Their direct progenitors are early B-type to late O-type stars that have exhausted their central hydrogen. Extending the Conti scenario [

1] to massive stars in general, Chiosi and Maeder [

2] link the various spectral types into an evolutionary sequence.

|

: |

O Of/WNL LBV WNL WC WO |

WR |

|

: |

O BSG LBV WNL (WNE) WC (WO) |

|

: |

O BSG RSG WNEWCE |

|

|

: |

O (BSG) RSG (YSG? LBV?) |

RSG |

|

: |

O/B RSG (Ceph. loop for ) RSG |

This scenario divides the O/B-type stars that become RSG and end their evolution as such, and the most massive O-types that become WR stars never expanding to the red side of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (HRD). In a small transitional mass range, O-type stars evolve to the red side of the HRD but lose enough mass there to evolve back to the blue and become WR (see

Sect. 4.2). Note that the exact mass range for the different evolutionary paths depends on the physics considered, and does not take into account any binary interactions that would drastically modify these simple relations.

This scenario also predicts that clusters should not host simultaneously RSG and WR populations coming from single stars, except in a very restricted age range (7-10 Myr). An overlap of both populations must come from binary interactions that created WR-like stripped stars through mass transfer.

Assuming a Salpeter initial mass function (IMF,[

3]), then about 90% of massive stars will have an RSG phase at some point in their life

1, and 80% of massive stars would end their life while being a RSG. These numbers highlight the importance of this phase for our understanding of massive star evolution, particularly for the advanced stages. According to the modified Conti scenario, we define three types of stellar pathways encompassing a RSG phase (see

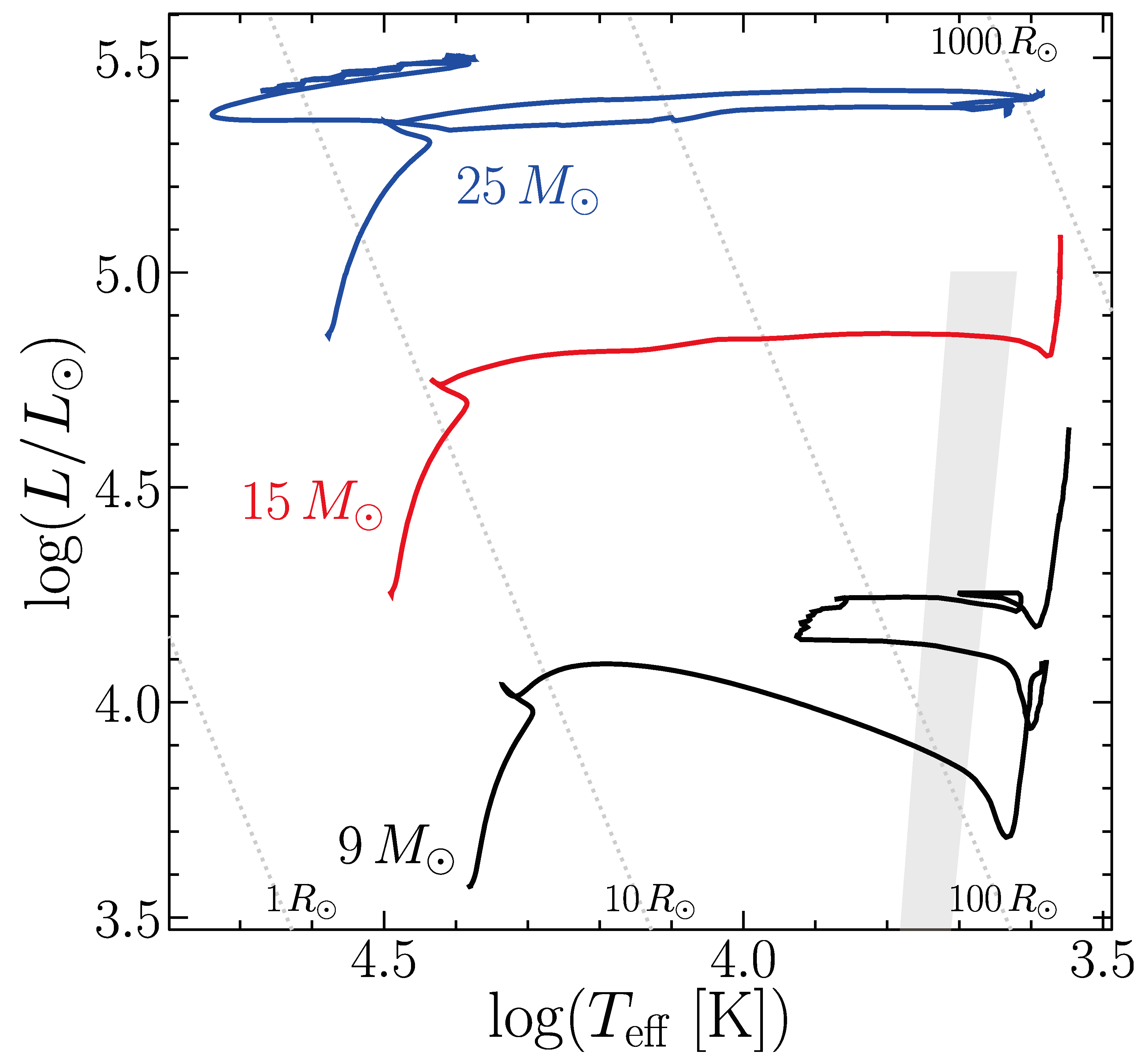

Figure 1):

Stars that become RSG quickly after the end of the MS, and that undergo a blue loop before going back to the red and ending their life there;

Stars that cross the Hertzsprung gap and stay RSG until the end of their life;

Stars that go to the RSG phase after the MS but evolve back to the blue and end their life there.

Figure 1.

HRD showing typical evolutionary pathway for three different initial masses (at solar metallicity, and with an initial rotation ). The 9 model (black) shows a quick crossing of the HRD at the end of the MS, and a blue loop during the RSG phase. The 15 model (red) shows a rather slow crossing to the RSG branch. The 25 model (blue) undergoes strong mass loss during the RSG phase, making the star to evolve bluewards at some point during the RSG phase, and end its life in the blue region of the HRD. The grey shaded area indicates the Cepheid instability strips, inside which a star is expected to have large radial oscillations. Lines of iso-R are displayed.

Figure 1.

HRD showing typical evolutionary pathway for three different initial masses (at solar metallicity, and with an initial rotation ). The 9 model (black) shows a quick crossing of the HRD at the end of the MS, and a blue loop during the RSG phase. The 15 model (red) shows a rather slow crossing to the RSG branch. The 25 model (blue) undergoes strong mass loss during the RSG phase, making the star to evolve bluewards at some point during the RSG phase, and end its life in the blue region of the HRD. The grey shaded area indicates the Cepheid instability strips, inside which a star is expected to have large radial oscillations. Lines of iso-R are displayed.

It has been suggested that RSGs could be used as distance indicators for probing the Universe, either by looking at the brightest RSG of a galaxy [

4,

5] or by using a period-luminosity relation for these objects [

6,

7]. However, these attempts would need some improvements of our understanding of the physics underlying the pulsations of RSGs in order to reach a reasonable efficiency in determining distances, particularly compared to other methods, such as the period-luminosity relation for Cepheid stars.

With their high luminosity that gives the opportunity to see them in distant galaxies, RSGs have been proposed as reliable probes of metallicity even when only low-resolution IR spectroscopy is available [

8,

9].

RSGs are dust producers, the highest luminosity ones producing the largest grain dust [

10]. While in the present-day Universe, RSG are contributing for at most 10% of the dust production [

11], massive Population III RSGs might have been important contributors in the early Universe [

12], as requested by highly dusty galaxies at a redshift

[

13].

2. Structure Change After the Main Sequence

At the end of central hydrogen burning, the core is devoid of fuel and contracts. This contraction liberates gravitational energy that can be used to inflate the envelope. Often referred to as the

mirror effect, the cause of this behaviour has been the subject of many studies [see for instance] [

14,

15,

16]. A simple explanation can be found in Padmanabhan [

17]. The contraction of the core at the end of the MS occurs in a timescale that is of the order of the Kelvin-Helmholtz timescale

, but that is longer than the virialisation timescale. In this case, both the energy conservation (

) and the virial theorem (

) must hold true. The only way to achieve this is to have both

U and

conserved separately. Stars at the end of the MS have a larger part of their mass in the core than in the envelope (

). The potential energy can be expressed as:

The location of the shell does not change significantly during the crossing of the Hertzsprung gap, so we can consider that both

and

are constant:

We can then express the evolution of the star radius as a function of the core radius:

which shows how a contraction of the core triggers the expansion of the envelope.

The fact that stars cross the Hertzsprung gap or not, and if so, the time needed to cross varies with stellar parameters. The strength of the intermediate convective zone (ICZ) building at the end of central H burning, on top of the H-burning shell, and the chemical gradient above it plays a crucial role [

18]. When the shell is strong, it supports the star and slows the crossing [

19]. Any condition leading to a deep and/or active shell favours a large ICZ. This is the case for larger initial masses, where the shell builds in hotter conditions: for stars more massive than 12

, He starts burning while the star is still crossing the Hertzsprung gap because the shell’s sustain is efficient enough to prevent the star to quickly cross the Hertzsprung gap. Similarly, a low metallicity slows the crossing down, because the compactness of the star [

20] locates the shell in a hotter region than in a star at solar metallicity.

For the same reasons, there is a dependency on the criterion used for the definition of convective zones. When the Ledoux criterion (

, [

21])

2 is taken instead of the Schwartzschild one (

, [

22]), the chemical gradient just above the initial location of the H-burning core prevents convection, so the ICZ is located higher in the star and weaker. The crossing is quick and accompanied by a drop in luminosity, with part of the radiation being used to inflate the envelope.

Another reason to cross the Hertzsprung gap quickly is linked to the overall opacity of the envelope, and hence to the mass of the H-rich envelope on top of the shell. The larger the mass of the envelope, the faster the crossing takes place [

23]. This imposes a natural limit to the maximal mass of RSG: above

, the MS mass loss removes enough of the H-rich envelope for the star to remain in the blue side of the Hertzsprung-Russel diagram (HRD). This mass limit translates into a luminosity limit when we compare the models to observations (see

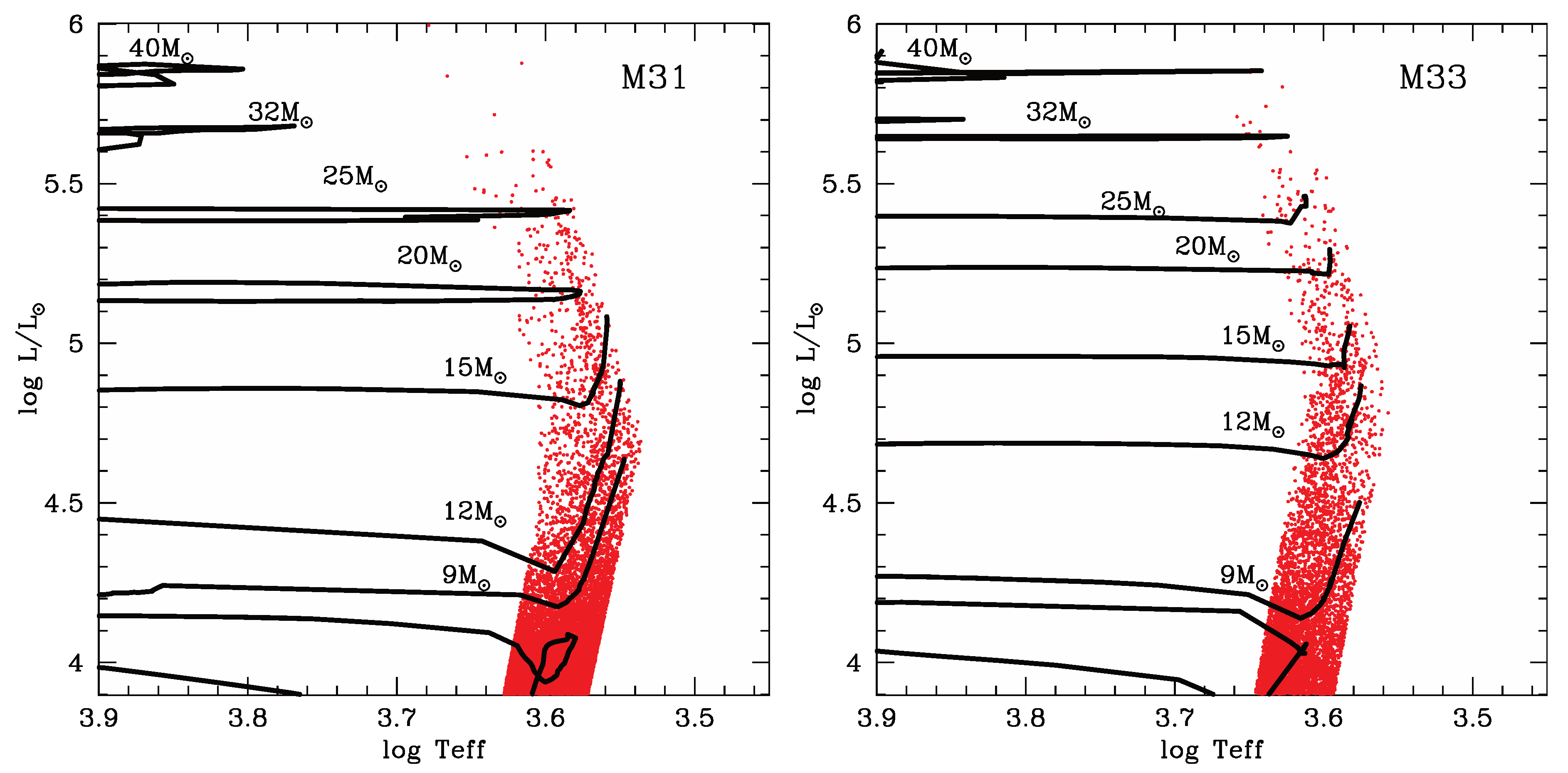

Figure 2) At low metallicity, the MS mass loss is weaker, but the stars are maintained in the blue by the Humphreys-Davidson limit [

24] and the inherent mass loss triggered by instabilities. Thus, the highest luminosity that RSGs can reach does not seem to depend on metallicity [

25].

3. Structure and Evolution in the RSG Phase

The RSG phase is marked by a strong contrast between the contracted central parts reaching the high temperature of He burning, and the very extended envelope cooling down as it expands. The opacity increases strongly because of the contribution of metal lines and, for the coolest RSGs, of molecules. The energy produced in the core cannot be transported by radiation only through the envelope, so convection is triggered, and a deep outer convective zone is built.

3.1. A Structure Dominated by Convection

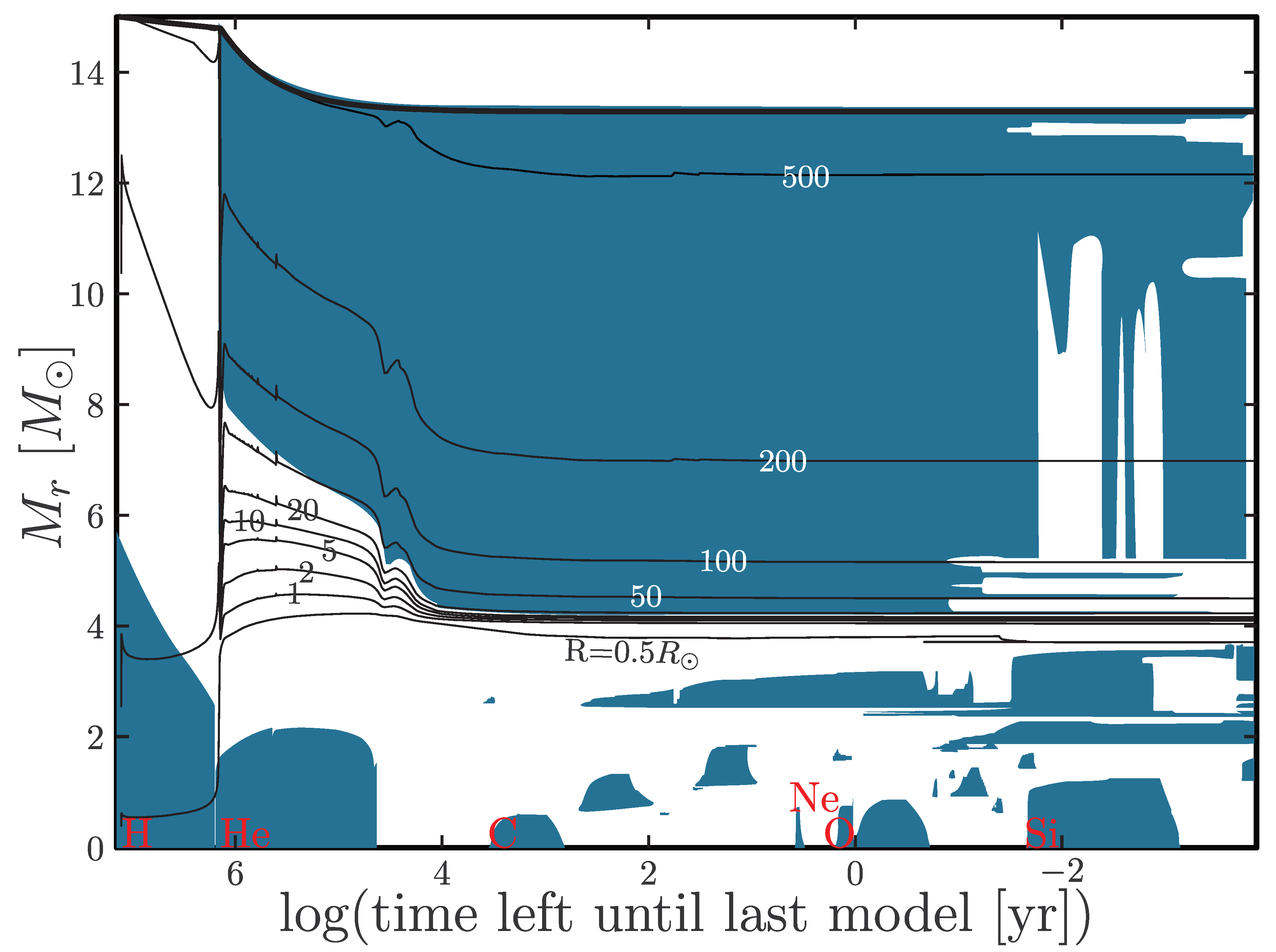

The outer convective zone dives deeply inside the stellar interior, engulfing the outer 60%-70% of the total mass

3 (see

Figure 3). This means that it reaches a zone where H burning took place previously, where the chemical composition has been modified by nuclear reactions (in particular, C and O have been transformed into N). The convective movements transport this material up to the surface [

29], providing a chemical enrichment even to non-rotating stars that are not supposed to mix otherwise. This is known as the First Dredge Up. The effect of this dredge up on the surface abundances depends on the exact modelling of the star. However, the general trend is that CNO-burning products should appear at the surface, i.e. an increase in the nitrogen abundance, and a depletion of carbon and oxygen. This seems to be confirmed by observations of RSG in the Galaxy [

30,

31].

The surface of RSGs is sculpted by convection. Direct imaging [

32] or interferometric observations of Betelgeuse and other RSGs [

33,

34] show inhomogeneities and aspheric structures that are attributed to convective granulation. Radiative hydrodynamic simulations confirm that convective cells are large and strongly asymmetric [

35,

36]. The characteristic size of convective granulation (

) is expected to scale with the atmospheric pressure scale height

like

, with

around 10 for AGB stars [

37]. In the case of RSGs, the effect of the turbulent pressure has to be taken into account, so the pressure scale height becomes

, with

a factor close to one,

the adiabatic exponent, and

the sound speed. This results in a granulation size approximately five times larger than when turbulent pressure is neglected [

35]. The largest convective cells evolve on a time scale of years, whereas smaller features vary on a time scale of months [

38]. At the surface of RSG stars, radiation-hydrodynamics simulations show that the contrast between the brightest and the darkest parts can reach a factor of about 50 [

36].

The variability induced by the convective movement on the surface of RSG contributes to a noise that blurs the determination of the position by astrometric measurements [

39]. For a Betelgeuse-like RSG, typically, the photocentre moves randomly with an amplitude of the order of 0.1 AU, significantly impacting the determination of the parallax, and hence the distance. Conversely, by measuring the dispersion in parallax measurements of RSGs that are members of a cluster (for which the distance can be known thanks to the other members), constraints on the surface convective dynamics could be obtained [

40]. Unfortunately it seems that the sensitivity of current astrometric instruments like

Gaia is still about an order of magnitude too low to be able to give meaningful results [

41].

Figure 3.

Kippenhahn diagram of a 15

model at solar metallicity (model from [

42]). The convective zones are the blue shaded regions. Lines of iso-

R are displayed. The central burning phases are indicated in red. The thick black line shows the total mass evolution of the star.

Figure 3.

Kippenhahn diagram of a 15

model at solar metallicity (model from [

42]). The convective zones are the blue shaded regions. Lines of iso-

R are displayed. The central burning phases are indicated in red. The thick black line shows the total mass evolution of the star.

3.2. Radius Increase and Binary Interactions

On the main sequence, the precursors of RSGs are O- and B-type stars, which are notably known to have a binary occurrence fraction larger than 60%. However, the binary occurrence fraction of RSGs is only around 30%. The "missing binaries" have several explanations. Typically, O- and B-type stars have radii of about 10

, but during the crossing of the Hertzsprung gap, the radius increases enormously, up to about 1500

for the largest known RSGs (see e.g. [

43]). With such an increase in radius, all systems with an orbital period lower than ∼1500 days are expected to undergo binary interactions, such as mass transfer, common envelope evolution, or merger, either already on the MS for the closest ones, or when the primary leaves the MS [

44].

In the case of the closest systems (

days), it is considered that there is a high probability that the two components merge already during the MS, creating a blue straggler. Some of them can later evolve into a red straggler, a RSG too young (too luminous) compared to its native cluster [

45] and that shows no sign of binarity any more. The merger can occur later, after a common-envelope phase triggered by the post-MS inflation of the primary, like the probable scenario for the progenitor of SN1987A [

46]. For periods between 10 and 1500 days, the expected binary interactions would lead the primary to become a stripped star, and if the mass transfer is stable, only the secondary would evolve to the RSG. In this case, it would either show signs of a compact companion, or the explosion of the primary would have disrupted the binary, the RSG appearing as a single, run-away star (or rather walk-away [

47]), like

Ori [

48].

For longer periods (

days), both stars essentially evolve as in isolation, preserving their binary nature in the RSG phase. If the RSG is the primary component of the binary system, it is more likely to have a B-type companion, since any companion with a mass lower than 3

would still be in the pre-MS contraction by the time the primary evolves to the RSG phase [

49]. This configuration can be detected by a photometric blue excess. Radial velocities for such long periods typically range between 1-5 km/s stretched on timescales of years or decades [

44]. Since these amplitude and period are close to those coming from the convective movements at the surface of the RSG, the binary diagnostic through radial velocities is a difficult one.

3.3. Mass-Loss Regime

Convective plumes can rise high above the "surface" [

50] and could be at the origin of strong mass-loss episodes [

51,

52,

53]. In general, the mass-loss regime shifts as a star enters the RSG phase. Despite the high opacity due to the low temperature, a radiatively-driven wind regime does not appear to be applicable to RSGs. Estimates of RSG mass-loss rates are abundant in the literature, though often contradictory, varying by orders of magnitude for a given RSG luminosity. [

54]. When a restricted mass domain and parameter space is targetted, as in the well-selected clusters determination performed by [

55], a tight correlation is found between the luminosity of the RSG and the mass-loss rate. Although in this work, the authors find lower mass-loss rates than the ones commonly used in stellar evolution codes, other works aiming at getting constrains on the RSG mass-loss rates through indirect methods, like the radio signature of SNe [

56] or the luminosity function of RSG [

57], seem to not favour low rates. Recent works [

58,

59,

60] find a kink in the

relation, with the slope steepening above a given luminosity (

). An still open question is the metallicity dependence of the RSG mass-loss rates. While measuring the

relation in the Magellanic Clouds is doable, that in the Milky Way is more complicated due to uncertainties in distances and reddening [

61].

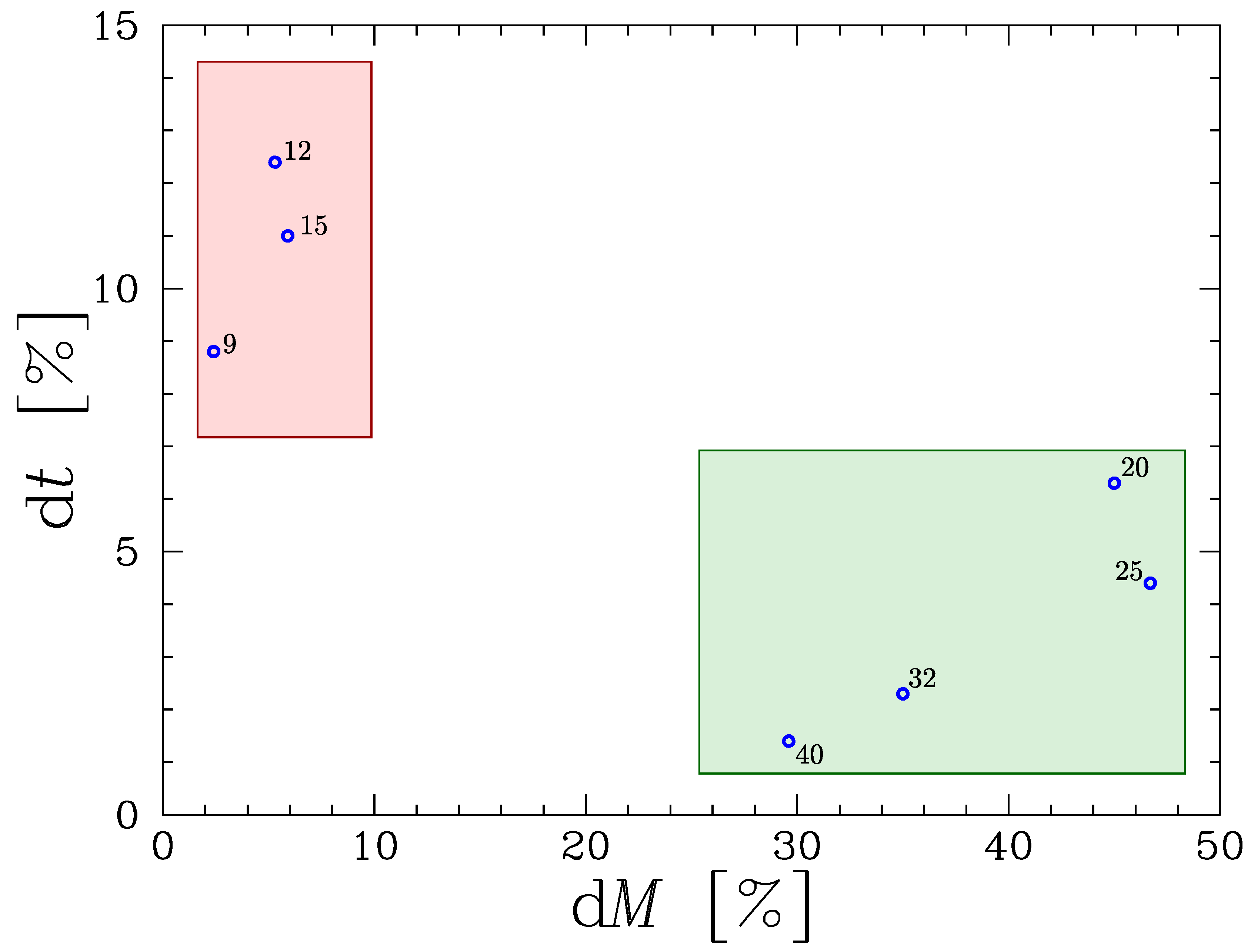

When observed mass-loss rates are translated into a recipe for stellar modelling, the main difficulty resides in the timesteps that are used by the models. Typical timesteps are of the order of decades or centuries, and they need to capture and average the bursty nature of RSG winds. The magnitude of the mass-loss rates has strong consequences in the predictions of stellar evolution in the RSG phase as well as endpoints or supernovae types. A strong mass loss during the RSG is supposed to lead the star to a blueward evolution (see

Sec. 4). Models show a clear division between the ones that lose a lot of mass and stay a short time in the RSG region, and those losing less mass and spending a long time in the RSG region (see

Figure 4).

3.4. Late Stages

After central helium burning exhaustion, the core contracts and heats, reaching temperatures where carbon burning can start. From this stage on, the energy produced inside the star is mostly evacuated by the mean of neutrinos rather than photons, and escapes the star without interacting with the gas. The nuclear timescale of the C-burning phase, which is the longest of the advanced phases, can be expressed as (contraction + C burning):

where

is the gravitational energy liberated by the contraction,

the energy produced by C burning,

the mass fraction of the core where the burning occurs, and

the luminosity emitted in the form of neutrinos. It becomes shorter than the Kelvin-Helmholtz time scale on which the envelope evolves:

The envelope therefore has no time to react to whatever happens in the centre of the star: the external appearance of the star is no longer changing, even if major changes occur in the central region, while multiple burning and contraction episodes succeed each other.

However, very early SNe observations reveal the latest events of the stars life, and offer a glimpse into the closest region of the circumstellar medium (CSM, [

62]). In the case of RSG progenitors, they point to a strongly increased mass loss shortly prior to the explosion. A steady wind lasting for more than a few decades is ruled out by pre-explosion images, because such a wind would veil the progenitor in dust and alter its appearance. Only an outburst or a strong wind lasting at most a few years is supported by early SN analyses [

63,

64]. Curiously, this CSM layer of thick and slow wind around ready-to-collapse RSG can mimic a WR wind and its typical HeII

4686 and CIII/NIII features [

65].

4. Blueward Evolution and Loops

While some stars remain RSGs once they enter this phase, others may either temporarily exit the RSG regime or permanently evolve back towards the blue. The former scenario is associated with Cepheid blue loops, whereas the latter pertains to the most massive RSGs.

4.1. Cepheids and Blue Loops

As they evolve along the red (super-)giant branch, stars with masses below approximately 12

undergo a temporary blueward excursion before returning to the red and ultimately ending their lives as RSGs. These blue loops develop progressively at the lower end of the mass range, with their extent reaching bluer regions of the HRD for more massive stars. At the upper end of this range, a sharp transition occurs from a maximally extended loop to the complete absence of a loop [

66].

The mechanism responsible for the launch of a blue loop is extremely complex. As expressed in Kippenhahn & Weigert: "

We see that details, which have originated from different regions and from earlier phases when the effects were scarcely recognizable, can now pop up and modify the evolution appreciably. The present phase is a sort of magnifying glass, also revealing relentlessly the faults of calculations of earlier phases." [

67]. Blue loops have been the subject of many studies. Parametric, static models with 2 or 3 zones have been used in the 1970s to explore under which conditions the solution of the stellar equations results in a blue or red location [

68,

69,

70], but causes and effects are difficult to disentangle. The key factor influencing the appearance or not of a loop seems to be the helium excess above the H-burning shell, a large composition discontinuity having a suppressing effect on the looping behaviour: while early studies evoked the potential of the core

as an influencing factor for the loops, it seems that it is not so much its value that plays a role, but rather its influence on the position of the H-burning shell and hence the H-He discontinuity [

71]. Any process that would modify the steepness of the discontinuity or the depth at which the outer convective zone dives will have an influence on the loops, either suppressing them or changing their extent [

72,

73].

Since the launching of a loop is triggered by the H-burning shell reaching the composition discontinuity left by the first dredge-up, it usually takes half the He-burning phase to reach that point, and the blue loop occurs in the second half of the He-burning phase. The end of the loop takes place very shortly before He exhaustion in the core. After the loop, the star moves back on the RSG branch and ends as a type II SN.

Given the sensitivity of the blue loops on the depth of the convective dredge-up and on the distance between the H-burning shell and the composition discontinuity, the mass range at which a blue loop is expected changes with metallicity. At solar

Z, blue loops are expected from

(but for the loop to reach the Cepheid instability strip, only

do so). At low

Z, the mass range is slightly shifted down. The loops are wider, and the most massive stars climb on the loop before having fully reached the RSG region [

73].

4.2. Blueward Excursion as the Final Evolution

Mass loss becomes an important process during the RSG phase (see the review by van Loon in this Special Issue). Since it is usually believed that the mass-loss rates scale with luminosity [

74,

75], they can reach high values for more luminous RSGs near the end of their life. The mass-loss rates during the RSG phase are relatively poorly known and vary a lot depending on the authors, the sample used, the type of stars, among other factors [e.g.[

54,

75,

76] see also [

77]]. In case the total mass lost during this phase is large enough to decrease significantly the mass of the H-rich envelope, it will make the star leave the RSG branch and evolve bluewards in the HRD, becoming a yellow hypergiant (see the review by Jones & Humphreys in this Special Issue), or possibly becoming a WR star if it were to lose its envelope almost completely. The blueward evolution of the RSG usually starts when the mass of the core exceeds about 60% of the total stellar mass [

78]. Depending on the mass-loss prescription used, this can occur for stars with an initial mass around

[

77,

79], or not at all below about

[

80]. Knowing precisely the mass-loss rates of RSG is thus of prime importance for stellar evolution, not only during the quiescent phases but also in the case of less common events of large outbursts. If the total mass lost during this phase remains relatively modest, the star will remain a RSG until the end of its life, leading to a type IIP supernova [

80] or directly collapse into a BH [

81]. On the other hand, if more copious amounts of mass can be lost during the RSG phase, the star will evolve further as a yellow supergiant, and then possibly as a blue supergiant or even a WR star [

82]. This would allow stars to end their life at different locations in the HRD, producing different types of SN events: intermediate type IIL or IIb for stars with an end-point in the yellow part of the HRD [

79], or type Ib or even type Ic for more massive stars able to completely remove their H-rich envelope [

77,

82] (see also the review by Van Dyk in this Special Issue).

Observationally, the idea that mass-loss rates of RSGs could have been underestimated has emerged from the so-called “red supergiant problem”. In fact, it appears from the study of the progenitors of a sample of type IIP supernova that no one of them had an initial mass greater than about

[

83,

84]. This implies that either more massive RSGs directly collapse into a BH [

81], or they evolve towards other regions of the HRD prior to explode into another supernova type, this being possible by increasing the mass-loss prescription in stellar evolution codes or by considering late mass-transfer episodes. However, note that this finding has been debated recently [

85,

86].

Another way of verifying whether a blue supergiant star is pre- or post-RSG phase is to compare some of its surface properties with observations. It has been shown that the surface abundances and pulsational properties of variable blue supergiant are best in line with stellar evolution prediction of post-RSG evolution for such stars, indicating that they are possibly on a bluewards evolution due to mass loss [

87,

88]. Indeed, a strong mass loss during the RSG phase considerably increases the

ratio of these stars, greatly favouring the triggering of pulsations, making their luminosity vary over time.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

As discussed above, the majority of massive stars will undergo an RSG phase, and most of them end their life during this stage. It is therefore of prime importance to have a good understanding of this phase, in order to have a better comprehension of massive star evolution in general, of the type II P supernovae progenitors

4, and of the precursors of various types of massive stars in their late stages. Seen from the point of view of star modelling, the most critical process to be constrained is the mass loss rates of RSGs. Not only the regular mass loss, but also possible mass-loss events related to eruptions, where a consequent quantity of mass can be lost in a short timescale. How frequent are these event? How much mass do they remove? How does metallicity affect the mass-loss budget of RSGs? Having strong constraints on this would definitely help in better modelling the RSG stage and the possible subsequent evolution of massive stars.

Acknowledgments

SE acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), grant number 212143.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BH(s) |

Black hole(s) |

| CSM |

Circumstellar medium |

| HRD |

Hertzsprung-Russell diagram |

| ICZ |

Intermediate convective zone |

| IMF |

Initial mass function |

| MS |

Main sequence |

| RSG(s) |

Red Supergiant(s) |

| SN(e) |

Supernova(e) |

| WR |

Wolf-Rayet |

References

- Conti, P.S. On the relationship between Of and WR stars. Memoires of the Société Royale des Sciences de Liège 1975, 9, 193.

- Chiosi, C.; Maeder, A. The evolution of massive stars with mass loss. ARA&A 1986, 24, 329. [CrossRef]

- Salpeter, E.E. The Luminosity Function and Stellar Evolution. ApJ 1955, 121, 161–+. [CrossRef]

- Sandage, A.; Tammann, G.A. Steps toward the Hubble constant. II. The brightest stars in late-type spiral galaxies. ApJ 1974, 191, 603–621. [CrossRef]

- Glass, I.S. Infrared observations of late-type supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds. MNRAS 1979, 186, 317. [CrossRef]

- Jurcevic, J.S.; Pierce, M.J.; Jacoby, G.H. Period-luminosity relations for red supergiant variables - II. The distance to M101. MNRAS 2000, 313, 868. [CrossRef]

- Chatys, F.W.; Bedding, T.R.; Murphy, S.J.; Kiss, L.L.; Dobie, D.; Grindlay, J.E. The period-luminosity relation of red supergiants with Gaia DR2. MNRAS 2019, 487, 4832. [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Kudritzki, R.P.; Figer, D.F. The potential of red supergiants as extragalactic abundance probes at low spectral resolution. MNRAS 2010, 407, 1203. [CrossRef]

- Bergemann, M.; Kudritzki, R.P.; Plez, B.; Davies, B.; Lind, K.; Gazak, Z. Red Supergiant Stars as Cosmic Abundance Probes: NLTE Effects in J-band Iron and Titanium Lines. ApJ 2012, 751, 156. [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; Plez, B.; Levesque, E.M.; Olsen, K.A.G.; Clayton, G.C.; Josselin, E. The Reddening of Red Supergiants: When Smoke Gets in Your Eyes. ApJ 2005, 634, 1286. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Boyer, M.L.; Kemper, F.; Meixner, M.; Sargent, B.A.; Riebel, D. The evolved-star dust budget of the Small Magellanic Cloud: the critical role of a few key players. MNRAS 2016, 457, 2814. [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, T.; Yoon, S.C.; Maeda, K.; Kozasa, T.; Nomoto, K.; Langer, N. Dust Production Factories in the Early Universe: Formation of Carbon Grains in Red-supergiant Winds of Very Massive Population III Stars. ApJL 2014, 787, L17. [CrossRef]

- Akins, H.B.; Casey, C.M.; Allen, N.; Bagley, M.B.; Dickinson, M.; Finkelstein, S.L.; Franco, M.; Harish, S.; Arrabal Haro, P.; Ilbert, O.; et al. Two Massive, Compact, and Dust-obscured Candidate z ≃ 8 Galaxies Discovered by JWST. ApJ 2023, 956, 61.

- Yahil, A.; van den Horn, L. Why do giants puff up? ApJ 1985, 296, 554.

- Applegate, J.H. Why Stars Become Red Giants. ApJ 1988, 329, 803. [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R.; Nigam, A. Qualitative Explanations of Red Giant Formation. ApJ 1991, 372, 592. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Theoretical Astrophysics, Volume 2: Stars and Stellar Systems; 2001.

- Sugimoto, D.; Fujimoto, M.Y. Why Stars Become Red Giants. ApJ 2000, 538, 837. [CrossRef]

- Sibony, Y.; Georgy, C.; Ekström, S.; Meynet, G. The impact of convective criteria on the properties of massive stars. A&A 2023, 680, A101. [CrossRef]

- Maeder, A.; Meynet, G. Stellar evolution with rotation. VII. Low metallicity models and the blue to red supergiant ratio in the SMC. A&A 2001, 373, 555.

- Ledoux, P. Stellar Models with Convection and with Discontinuity of the Mean Molecular Weight. ApJ 1947, 105, 305.

- Schwarzschild, M. Structure and evolution of the stars.; Princeton University Press, 1958.

- Farrell, E.J.; Groh, J.H.; Meynet, G.; Eldridge, J.J.; Ekström, S.; Georgy, C. SNAPSHOT: connections between internal and surface properties of massive stars. MNRAS 2020, 495, 4659. [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, R.M.; Davidson, K. Studies of luminous stars in nearby galaxies. III - Comments on the evolution of the most massive stars in the Milky Way and the Large Magellanic Cloud. ApJ 1979, 232, 409. [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Crowther, P.A.; Beasor, E.R. The luminosities of cool supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds, and the Humphreys-Davidson limit revisited. MNRAS 2018, 478, 3138. [CrossRef]

- Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Eggenberger, P.; Meynet, G.; Mowlavi, N.; Wyttenbach, A.; Granada, A.; Decressin, T.; Hirschi, R.; Frischknecht, U.; et al. Grids of stellar models with rotation. I. Models from 0.8 to 120 M⊙ at solar metallicity (Z = 0.014). A&A 2012, 537, A146.

- Eggenberger, P.; Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Martinet, S.; Pezzotti, C.; Nandal, D.; Meynet, G.; Buldgen, G.; Salmon, S.; Haemmerlé, L.; et al. Grids of stellar models with rotation. VI. Models from 0.8 to 120 M⊙ at a metallicity Z = 0.006. A&A 2021, 652, A137. [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; Neugent, K.F.; Levesque, E.M.; Drout, M.R.; Courteau, S. The Red Supergiant Content of M31 and M33. AJ 2021, 161, 79. [CrossRef]

- Iben, Jr., I. The Surface Ratio of N14 to C12 during Helium Burning. ApJ 1964, 140, 1631.

- Davies, B.; Origlia, L.; Kudritzki, R.P.; Figer, D.F.; Rich, R.M.; Najarro, F.; Negueruela, I.; Clark, J.S. Chemical Abundance Patterns in the Inner Galaxy: The Scutum Red Supergiant Clusters. ApJ 2009, 696, 2014–2025, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/0902.2378]. [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Origlia, L.; Kudritzki, R.P.; Figer, D.F.; Rich, R.M.; Najarro, F. The Chemical Abundances in the Galactic Center from the Atmospheres of Red Supergiants. ApJ 2009, 694, 46–55, [arXiv:astro-ph/0811.3179]. [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, R.L.; Dupree, A.K. First Image of the Surface of a Star with the Hubble Space Telescope. ApJL 1996, 463, L29. [CrossRef]

- Tatebe, K.; Chandler, A.A.; Wishnow, E.H.; Hale, D.D.S.; Townes, C.H. The Nonspherical Shape of Betelgeuse in the Mid-Infrared. ApJL 2007, 670, L21. [CrossRef]

- Haubois, X.; Perrin, G.; Lacour, S.; Verhoelst, T.; Meimon, S.; Mugnier, L.; Thiébaut, E.; Berger, J.P.; Ridgway, S.T.; Monnier, J.D.; et al. Imaging the spotty surface of Betelgeuse in the H band. A&A 2009, 508, 923.

- Chiavassa, A.; Plez, B.; Josselin, E.; Freytag, B. Radiative hydrodynamics simulations of red supergiant stars. I. interpretation of interferometric observations. A&A 2009, 506, 1351. [CrossRef]

- Chiavassa, A.; Haubois, X.; Young, J.S.; Plez, B.; Josselin, E.; Perrin, G.; Freytag, B. Radiative hydrodynamics simulations of red supergiant stars. II. Simulations of convection on Betelgeuse match interferometric observations. A&A 2010, 515, A12.

- Freytag, B.; Holweger, H.; Steffen, M.; Ludwig, H.G. On the Scale of Photospheric Convection. In Proceedings of the Science with the VLT Interferometer; Paresce, F., Ed., 1997, p. 316.

- Norris, R.P.; Baron, F.R.; Monnier, J.D.; Paladini, C.; Anderson, M.D.; Martinez, A.O.; Schaefer, G.H.; Che, X.; Chiavassa, A.; Connelley, M.S.; et al. Long Term Evolution of Surface Features on the Red Supergiant AZ Cyg. ApJ 2021, 919, 124. [CrossRef]

- Chiavassa, A.; Pasquato, E.; Jorissen, A.; Sacuto, S.; Babusiaux, C.; Freytag, B.; Ludwig, H.G.; Cruzalèbes, P.; Rabbia, Y.; Spang, A.; et al. Radiative hydrodynamic simulations of red supergiant stars. III. Spectro-photocentric variability, photometric variability, and consequences on Gaia measurements. A&A 2011, 528, A120. [CrossRef]

- Chiavassa, A.; Kudritzki, R.; Davies, B.; Freytag, B.; de Mink, S.E. Probing red supergiant dynamics through photo-center displacements measured by Gaia. A&A 2022, 661, L1. [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, C.S. A non-detection of red supergiant convection in Gaia. MNRAS 2023, 520, 3510. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.; Aloy, M.Á.; Hirschi, R.; Reichert, M.; Obergaulinger, M.; Whitehead, E.E.; Martinet, S.; Sciarini, L.; Ekström, S.; Meynet, G. Evolving massive stars to core collapse with GENEC: Extension of equation of state, opacities and effective nuclear network. A&A 2025, 693, A93. [CrossRef]

- Wittkowski, M.; Hauschildt, P.H.; Arroyo-Torres, B.; Marcaide, J.M. Fundamental properties and atmospheric structure of the red supergiant VY Canis Majoris based on VLTI/AMBER spectro-interferometry. A&A 2012, 540, L12, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1203.5194]. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, L.R.; Lennon, D.J.; Evans, C.J.; Sana, H.; Bodensteiner, J.; Britavskiy, N.; Dorda, R.; Herrero, A.; Negueruela, I.; de Koter, A. Multiplicity of the red supergiant population in the young massive cluster NGC 330. A&A 2020, 635, A29. [CrossRef]

- Britavskiy, N.; Lennon, D.J.; Patrick, L.R.; Evans, C.J.; Herrero, A.; Langer, N.; van Loon, J.T.; Clark, J.S.; Schneider, F.R.N.; Almeida, L.A.; et al. The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey. XXX. Red stragglers in the clusters Hodge 301 and SL 639. A&A 2019, 624, A128.

- Podsiadlowski, P.; Joss, P.C.; Rappaport, S. A merger model for SN 1987A. A&A 1990, 227, L9.

- Renzo, M.; Zapartas, E.; de Mink, S.E.; Götberg, Y.; Justham, S.; Farmer, R.J.; Izzard, R.G.; Toonen, S.; Sana, H. Massive runaway and walkaway stars. A study of the kinematical imprints of the physical processes governing the evolution and explosion of their binary progenitors. A&A 2019, 624, A66.

- Harper, G.M.; Brown, A.; Guinan, E.F. A New VLA-Hipparcos Distance to Betelgeuse and its Implications. AJ 2008, 135, 1430.

- Neugent, K.F. The Red Supergiant Binary Fraction as a Function of Metallicity in M31 and M33. ApJ 2021, 908, 87. [CrossRef]

- López Ariste, A.; Wavasseur, M.; Mathias, P.; Lèbre, A.; Tessore, B.; Georgiev, S. The height of convective plumes in the red supergiant μ Cep. A&A 2023, 670, A62. [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Humphreys, R.M.; Davidson, K.; Gehrz, R.D.; Schuster, M.T.; Krautter, J. The Asymmetric Nebula Surrounding the Extreme Red Supergiant VY Canis Majoris. AJ 2001, 121, 1111. [CrossRef]

- Montargès, M.; Cannon, E.; Lagadec, E.; de Koter, A.; Kervella, P.; Sanchez-Bermudez, J.; Paladini, C.; Cantalloube, F.; Decin, L.; Scicluna, P.; et al. A dusty veil shading Betelgeuse during its Great Dimming. Nature 2021, 594, 365. [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, R.M.; Jones, T.J. Episodic Gaseous Outflows and Mass Loss from Red Supergiants. AJ 2022, 163, 103. [CrossRef]

- Mauron, N.; Josselin, E. The mass-loss rates of red supergiants and the de Jager prescription. A&A 2011, 526, A156. [CrossRef]

- Beasor, E.R.; Davies, B. The evolution of red supergiant mass-loss rates. MNRAS 2018, 475, 55. [CrossRef]

- Moriya, T.J. Constraining red supergiant mass-loss prescriptions through supernova radio properties. MNRAS 2021, 503, L28. [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; Neugent, K.F.; Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Meynet, G. The Time-averaged Mass-loss Rates of Red Supergiants as Revealed by Their Luminosity Functions in M31 and M33. ApJ 2023, 942, 69. [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, R.M.; Helmel, G.; Jones, T.J.; Gordon, M.S. Exploring the Mass-loss Histories of the Red Supergiants. AJ 2020, 160, 145. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Bonanos, A.Z.; Jiang, B.; Zapartas, E.; Gao, J.; Ren, Y.; Lam, M.I.; Wang, T.; Maravelias, G.; Gavras, P.; et al. Evolved massive stars at low-metallicity. V. Mass-loss rate of red supergiant stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud. A&A 2023, 676, A84.

- Antoniadis, K.; Bonanos, A.Z.; de Wit, S.; Zapartas, E.; Munoz-Sanchez, G.; Maravelias, G. Establishing a mass-loss rate relation for red supergiants in the Large Magellanic Cloud. A&A 2024, 686, A88. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, K.; Zapartas, E.; Bonanos, A.Z.; Maravelias, G.; Vlassis, S.; Munoz-Sanchez, G.; Nally, C.; Meixner, M.; Jones, O.C.; Lenkic, L.; et al. Investigating the metallicity dependence of the mass-loss rate relation of red supergiants. arXiv e-prints 2025, p. arXiv:2503.05876.

- Morozova, V.; Piro, A.L.; Valenti, S. Measuring the Progenitor Masses and Dense Circumstellar Material of Type II Supernovae. ApJ 2018, 858, 15. [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Plez, B.; Petrault, M. Explosion imminent: the appearance of red supergiants at the point of core-collapse. MNRAS 2022, 517, 1483. [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, D.; Tsuna, D.; Berger, E.; Itagaki, K.; Goldberg, J.A.; Gomez, S.; Kishalay De.; Hosseinzadeh, G.; Bostroem, K.A.; Brown, P.J.; et al. From Discovery to the First Month of the Type II Supernova 2023ixf: High and Variable Mass Loss in the Final Year before Explosion. ApJL 2023, 955, L8. [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Mauerhan, J.C.; Cenko, S.B.; Kasliwal, M.M.; Silverman, J.M.; Filippenko, A.V.; Gal-Yam, A.; Clubb, K.I.; Graham, M.L.; Leonard, D.C.; et al. PTF11iqb: cool supergiant mass-loss that bridges the gap between Type IIn and normal supernovae. MNRAS 2015, 449, 1876. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.I.; Saio, H.; Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Meynet, G. On the effect of rotation on populations of classical Cepheids. II. Pulsation analysis for metallicities 0.014, 0.006, and 0.002. A&A 2016, 591, A8.

- Kippenhahn, R.; Weigert, A. Stellar Structure and Evolution; Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg New York., 1990.

- Lauterborn, D.; Refsdal, S.; Weigert, A. Stars with Central Helium Burning and the Occurrence of Loops in the H-R Diagram. A&A 1971, 10, 97.

- Fricke, K.J.; Strittmatter, P.A. Evolutionary aspects of the Cepheid stage. MNRAS 1972, 156, 129. [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, B.M. The hydrogen profile, previous mixing, and loops in the H-R diagram during core helium burning. ApJ 1977, 212, 507–512. [CrossRef]

- Walmswell, J.J.; Tout, C.A.; Eldridge, J.J. On the blue loops of intermediate-mass stars. MNRAS 2015, 447, 2951. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Bressan, A.; Rosenfield, P.; Slemer, A.; Marigo, P.; Girardi, L.; Bianchi, L. New PARSEC evolutionary tracks of massive stars at low metallicity: testing canonical stellar evolution in nearby star-forming dwarf galaxies. MNRAS 2014, 445, 4287. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Song, H.; Meynet, G.; Maeder, A.; Ekström, S.; Zhang, R.; Qin, Y.; Qi, S.; Zhan, Q. The evolutionary properties of the blue loop under the influence of rapid rotation and low metallicity. A&A 2023, 674, A92. [CrossRef]

- de Jager, C.; Nieuwenhuijzen, H.; van der Hucht, K.A. Mass loss rates in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. A&AS 1988, 72, 259–289.

- Beasor, E.R.; Davies, B.; Smith, N.; van Loon, J.T.; Gehrz, R.D.; Figer, D.F. A new mass-loss rate prescription for red supergiants. MNRAS 2020, 492, 5994–6006, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2001.07222]. [CrossRef]

- van Loon, J.T.; Cioni, M.R.L.; Zijlstra, A.A.; Loup, C. An empirical formula for the mass-loss rates of dust-enshrouded red supergiants and oxygen-rich Asymptotic Giant Branch stars. A&A 2005, 438, 273–289. [CrossRef]

- Meynet, G.; Chomienne, V.; Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Granada, A.; Groh, J.; Maeder, A.; Eggenberger, P.; Levesque, E.; Massey, P. Impact of mass-loss on the evolution and pre-supernova properties of red supergiants. A&A 2015, 575, A60. [CrossRef]

- Giannone, P. Sequences of Inhomogeneous Models for Helium-Burning Stars. Zeitschrift für Astrophysik 1967, 65, 226.

- Georgy, C. Yellow supergiants as supernova progenitors: an indication of strong mass loss for red supergiants? A&A 2012, 538, L8. [CrossRef]

- Beasor, E.R.; Davies, B.; Smith, N. The Impact of Realistic Red Supergiant Mass Loss on Stellar Evolution. ApJ 2021, 922, 55, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2109.03239]. [CrossRef]

- Fryer, C.L. Mass Limits For Black Hole Formation. ApJ 1999, 522, 413. [CrossRef]

- Georgy, C.; Ekström, S.; Meynet, G.; Massey, P.; Levesque, E.M.; Hirschi, R.; Eggenberger, P.; Maeder, A. Grids of stellar models with rotation. II. WR populations and supernovae/GRB progenitors at Z = 0.014. A&A 2012, 542, A29.

- Smartt, S.J.; Eldridge, J.J.; Crockett, R.M.; Maund, J.R. The death of massive stars - I. Observational constraints on the progenitors of Type II-P supernovae. MNRAS 2009, 395, 1409–1437. [CrossRef]

- Smartt, S.J. Observational Constraints on the Progenitors of Core-Collapse Supernovae: The Case for Missing High-Mass Stars. PASA 2015, 32, e016. [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Beasor, E.R. ’On the red supergiant problem’: a rebuttal, and a consensus on the upper mass cut-off for II-P progenitors. MNRAS 2020, 496, L142–L146, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2005.13855]. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, E.J.; Groh, J.H.; Meynet, G.; Eldridge, J.J. The uncertain masses of progenitors of core-collapse supernovae and direct-collapse black holes. MNRAS 2020, 494, L53. [CrossRef]

- Saio, H.; Georgy, C.; Meynet, G. Evolution of blue supergiants and α Cygni variables: puzzling CNO surface abundances. MNRAS 2013, 433, 1246–1257. [CrossRef]

- Georgy, C.; Saio, H.; Meynet, G. The puzzle of the CNO abundances of α Cygni variables resolved by the Ledoux criterion. MNRAS 2014, 439, L6–L10. [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Li, W.; Filippenko, A.V.; Chornock, R. Observed fractions of core-collapse supernova types and initial masses of their single and binary progenitor stars. MNRAS 2011, 412, 1522–1538, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1006.3899]. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Here we assume it is the case for stars with an initial mass between 8 and 40

|

| 2 |

with (where comes from a general equation of state of the form ), the radiative gradient (where the opacity and obvious meanings for L, P, M, and T), and the gradient of the average mean molecular weight. |

| 3 |

It is even more impressive when expressed in terms of the radius of the star. The outer convective zone of a RSG covers more than of the total radius of the star. |

| 4 |

We recall here that type II P SNe is by far the most numerous type of gravitational supernovae [ 89]. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).