1. Introduction

Entropy without Access

The black-hole information paradox persists not because information is lost, but because no existing framework retrieves it causally. Replica–wormhole paths [

1,

2], island prescriptions [

3], ensemble Page–curve models [

4,

5], and

dualities [

6] all reproduce the required fine-grained entropy curves, yet none supplies a Lorentzian, proper-time recovery channel that delivers the state to a detector. Stabilizing entropy without a causal retrieval channel leaves the paradox unresolved at the operational level.

1.1. Operational–Access Criterion

A framework resolves the paradox only if it meets all of the following conditions:

- (a)

Proper-time delivery: specifies how entropy reaches an observer as proper time unfolds;

- (b)

Lorentzian grounding: roots that access in Lorentzian causality;

- (c)

First-principles derivation: derives the process from accepted QFT or GR principles rather than retrospective fitting;

- (d)

Empirical testability: predicts observer-dependent lags

within sub-exponential resource bounds

1.

Table 1.

Compliance of major black-hole information proposals with the criteria in

Section 1.1. A check mark denotes compliance; a cross denotes failure.

Table 1.

Compliance of major black-hole information proposals with the criteria in

Section 1.1. A check mark denotes compliance; a cross denotes failure.

| Framework |

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

(d) |

| Replica wormholes |

× |

× |

✓ |

× |

| Islands |

× |

× |

✓ |

× |

| Ensemble Page |

× |

✓ |

× |

× |

| ER=EPR |

× |

✓ |

× |

× |

Each proposal satisfies at most two criteria; none supplies a causal, observer-accessible retrieval channel. Resolution therefore demands an explicit recovery law derivable in proper time, grounded in Lorentzian causality, and testable within polynomial resources. The Observer-Dependent Entropy Retrieval (ODER) framework meets those demands with modular-flow dynamics and wedge-reconstruction depths that scale polynomially, in contrast with the exponential-cost Hayden–Preskill decoder assumed for global recovery. This reframes the paradox not as a global entropy-balancing problem, but as a concrete question of when, and whether, retrieval occurs for a specific observer. Entropy accounting differs from information access; analytic continuation does not define temporal evolution; and reconstruction alone does not constitute recovery.

Reader Guide

Appendix E offers an interpretive correspondence for readers unfamiliar with modular dynamics, mapping , , and to gravitationally intuitive quantities without altering the retrieval framework.

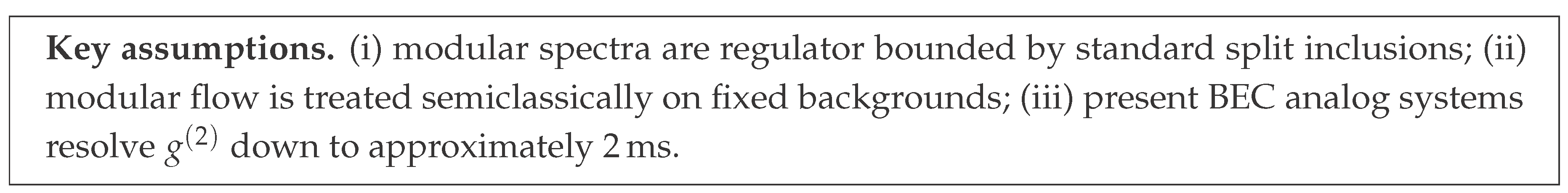

2. Observer-Dependent Entropy Retrieval

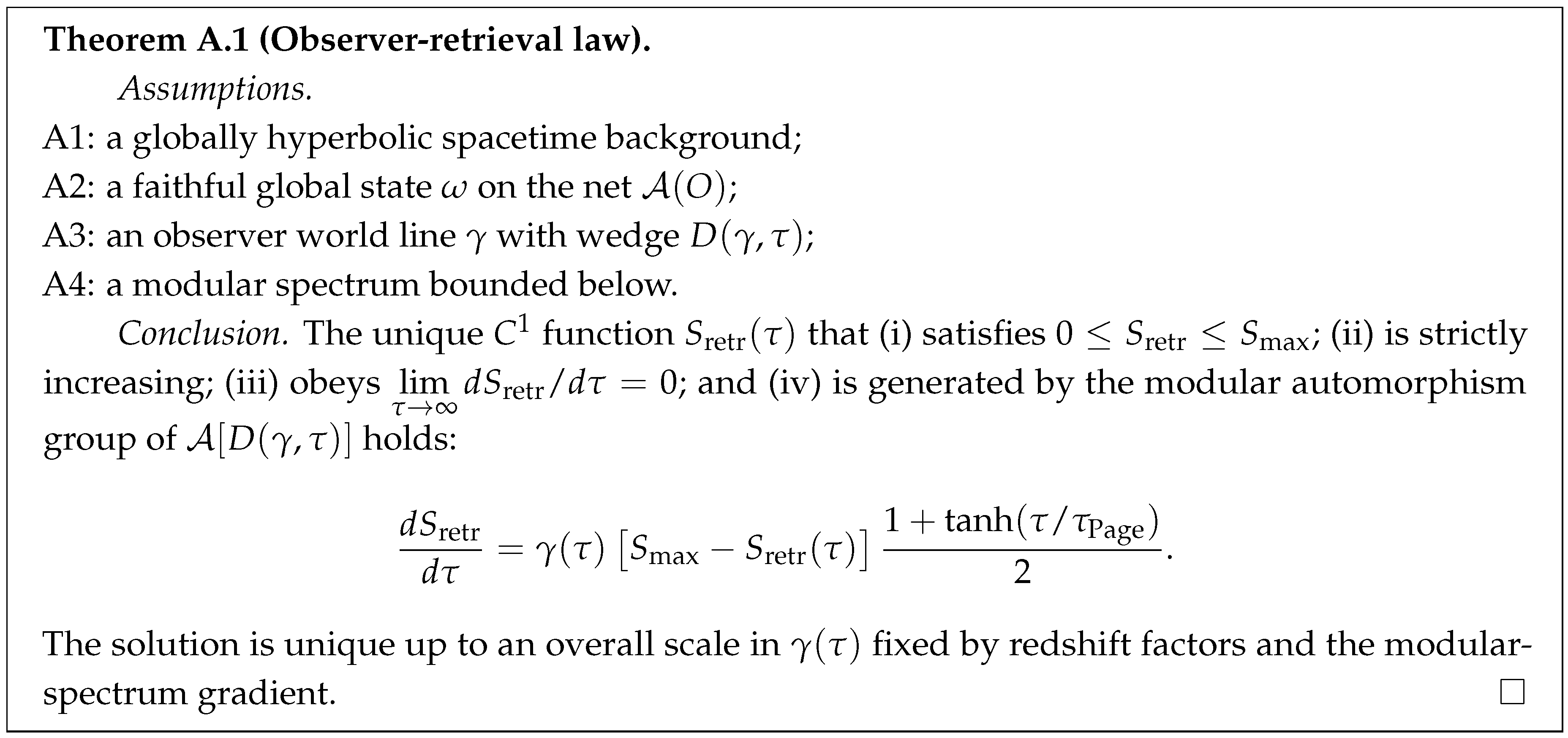

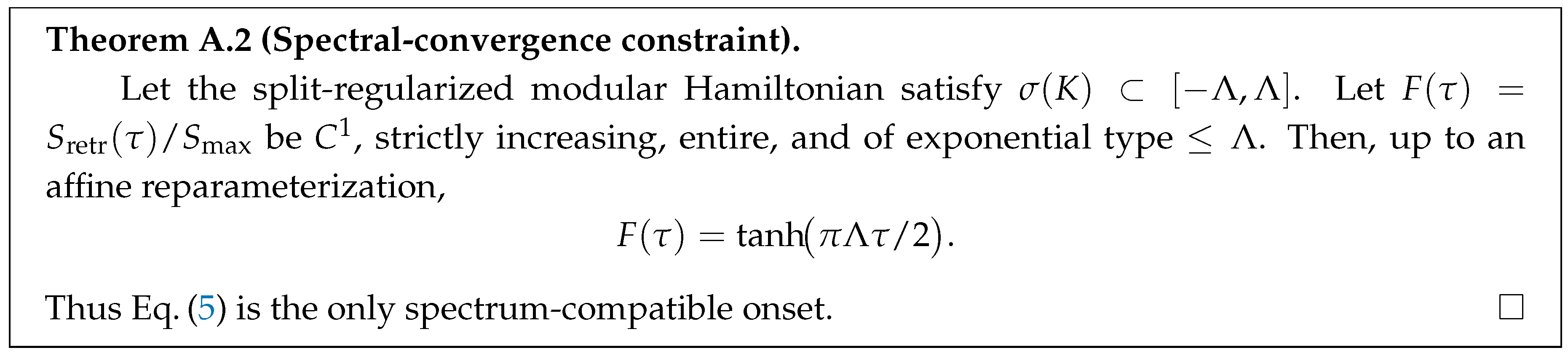

Novel Framework.

ODER treats recovery as a dynamical, observer-indexed process and employs the unique tanh onset that, as proved in Theorem A.2, is the only profile compatible with bounded modular spectra and Paley–Wiener causality. This section derives

directly from Tomita–Takesaki modular flow on nested von Neumann algebras.

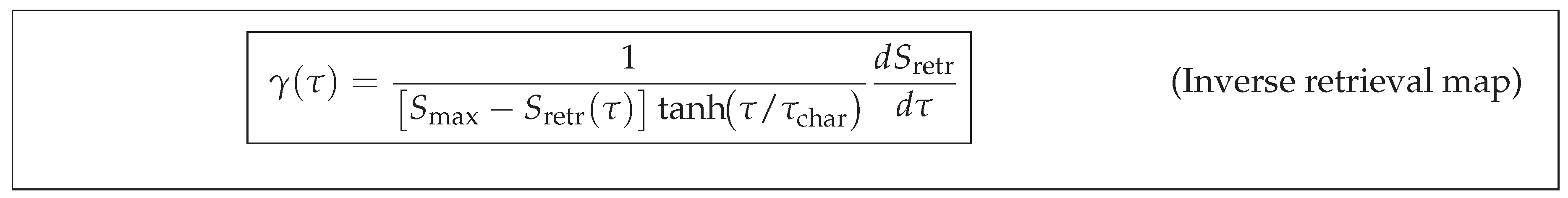

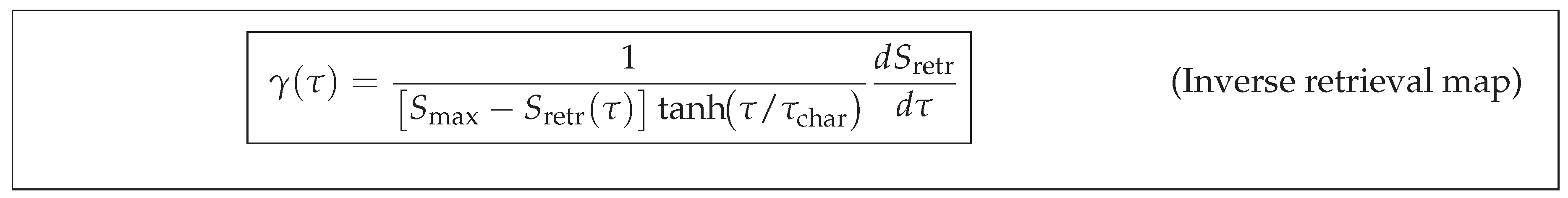

Because Eq. (

1) is first order and monotone in

, we can solve it for the unknown rate

. This inversion is essential in Section 3, where retrieval rates for different observer classes are compared.

Implication. Once an experiment measures , for example through the fringe, the boxed map fixes without further assumptions, turning ODER from a forward model into a calibratable decoder.

-

Goal

model entropy recovery as a bounded, causal convergence in proper time that differs by observer.

-

Mechanism

Eq. (

1) depends on modular-spectrum gradients.

encodes redshift, Unruh, or interior-correlation effects.

-

Domain of validity

algebraic QFT on Lorentzian backgrounds. Simulations on a 48-qubit MERA lattice confirm robustness. The model predicts an acceleration-dependent envelope in BEC analog black holes on timescales, a signature absent from non-retrieval models.

We define the retrieval horizon

the proper time at which

of the retrievable entropy is accessed; this horizon is distinct from both the entanglement wedge and the classical event horizon.

Self-Audit: ODER Failure Modes

Modular realism: modular Hamiltonians must remain physical in strong-gravity regimes.

Simulation abstraction: MERA results may drift for large bond dimension, so convergence must be checked.

Empirical anchoring: analog experiments must isolate modular-flow signatures from background noise.

Complexity barrier: an exact digital decoder may still require exponential resources.

Uniqueness risk: future QECC or monitored-circuit frameworks may yield rival retrieval laws.

Astrophysical Forecast.

For a solar-mass Schwarzschild black hole, Eq. (

1) implies that a stationary observer at

retrieves at least

of the missing entropy only after

, a timescale absent from replica-wormhole or island prescriptions. Sections 6–7.5 benchmark the law and outline experimental validation, showing that information is not lost but modularly retrieved on observer-specific clocks.

3. Observer-Dependent Entropy in Curved Spacetime

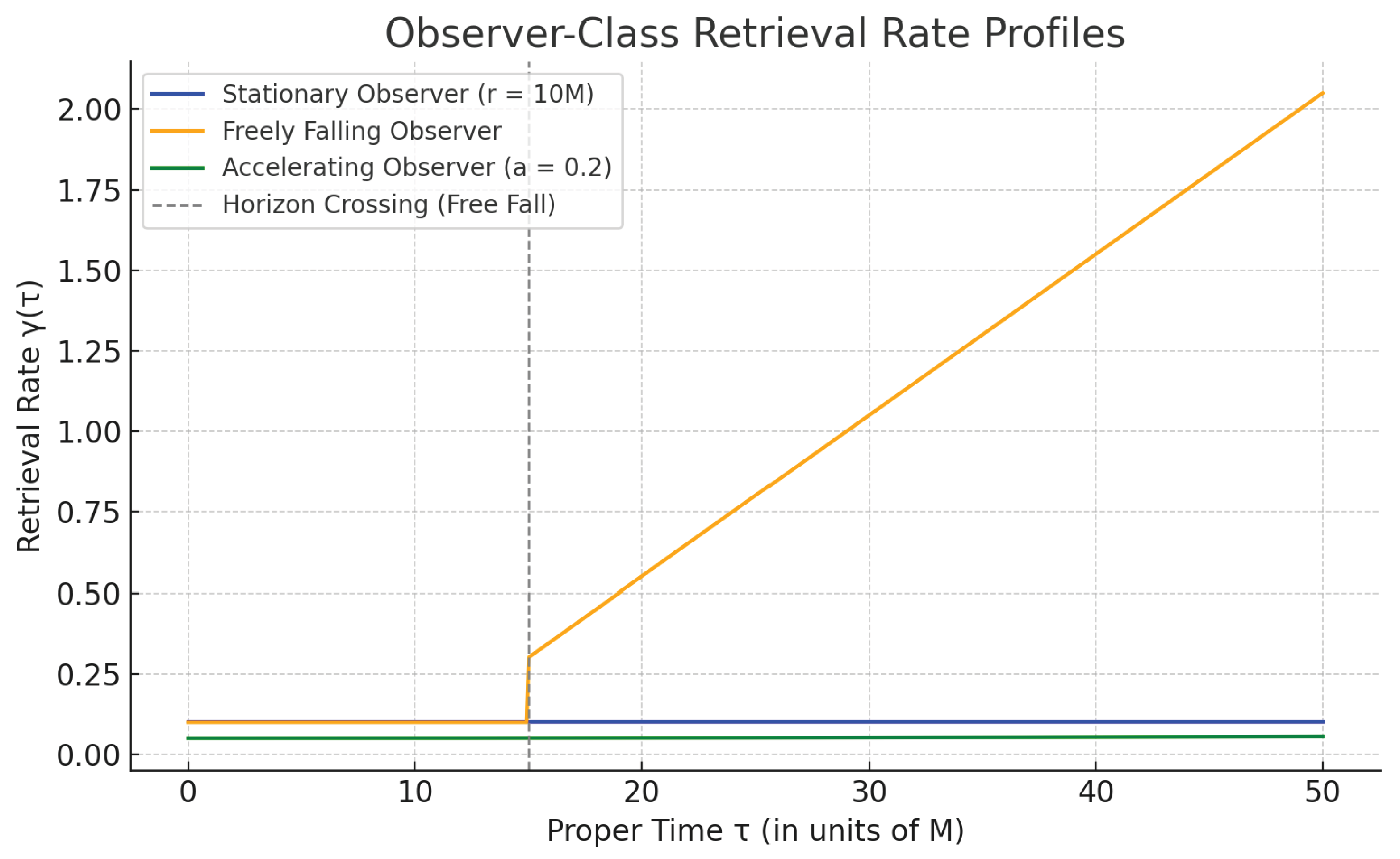

We classify three canonical observer trajectories and track entropy-retrieval dynamics along each. The retrieval rate is fixed by the local modular Hamiltonian, with no phenomenological fits, and evolves with proper time.

3.1. Classification of Observers

Stationary Observer.

A detector at fixed radius

perceives Hawking radiation as redshifted thermal flux; this gives

and a monotonic decay in

correlations. For

we find

because no interior mode enters the algebra.

Freely Falling Observer.

A geodesic world line crosses the horizon at

; interior modes then boost the retrieval rate,

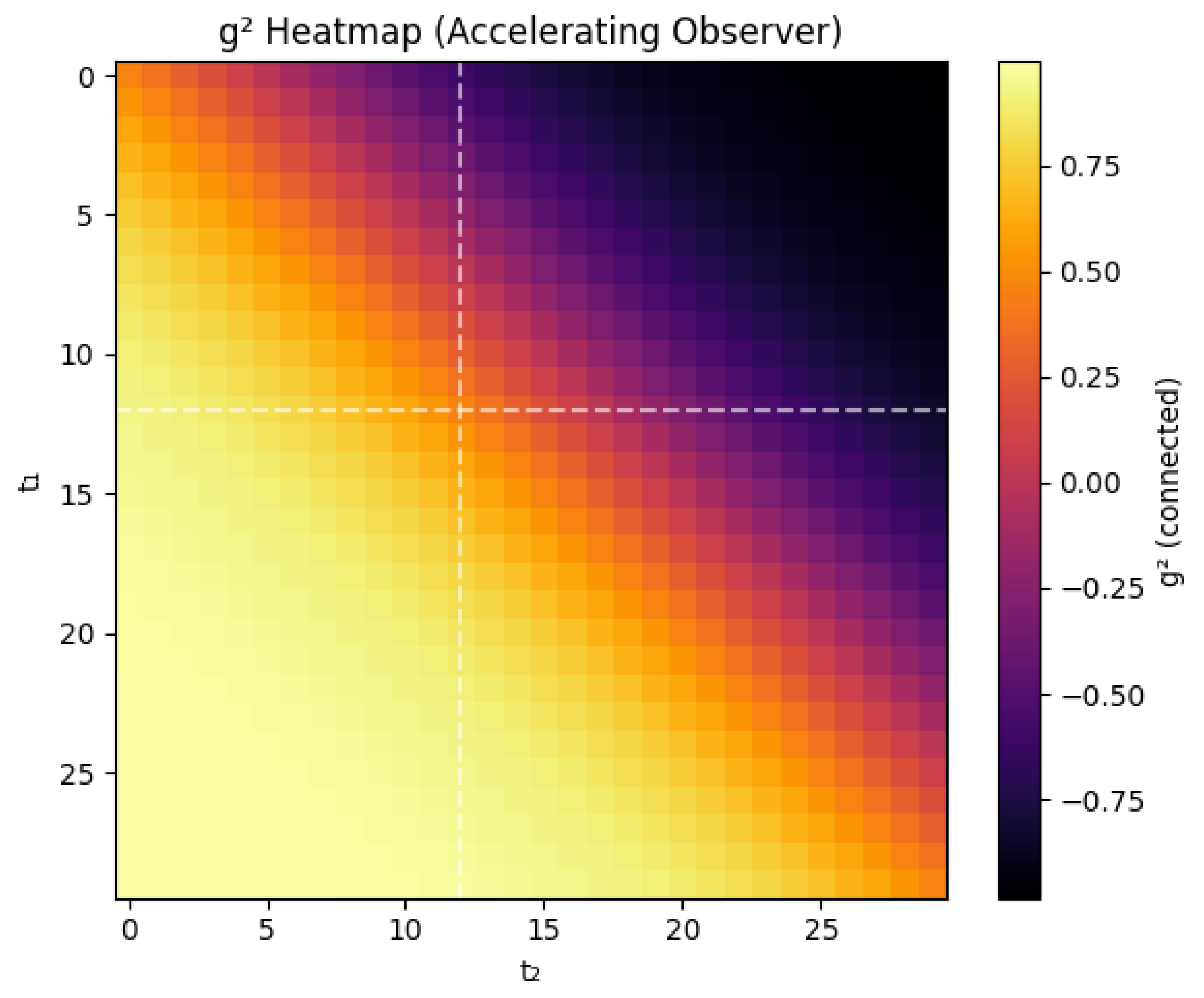

accelerating saturation (orange curve in

Figure 1).

Accelerating Observer.

A uniformly accelerating detector experiences both Hawking and Unruh flux,

with

[

12]. At

the retrieval envelope is the green curve in

Figure 1.

Experimental emulation: stationary and accelerating channels can be engineered in waterfall BECs, while freely falling trajectories correspond to time-of-flight release [

13]. Parameters appear in

Table 2.

Figure 1.

Representative retrieval-rate profiles for the three observer classes. Stationary: (blue); freely falling: geodesic starting at (orange); accelerating: proper acceleration (green). Times are in units of M with .

Figure 1.

Representative retrieval-rate profiles for the three observer classes. Stationary: (blue); freely falling: geodesic starting at (orange); accelerating: proper acceleration (green). Times are in units of M with .

Table 2.

Indicative parameters for each observer class ( in geometric units). The retrieval horizon is defined by .

Table 2.

Indicative parameters for each observer class ( in geometric units). The retrieval horizon is defined by .

| Observer |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stationary |

10 |

0 |

5 |

8 |

30 |

| Freely falling |

6–2 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

10 |

| Accelerating |

— |

0.2 |

3 |

5 |

15 |

3.2. Observer-Dependent Entropy

Observer-dependent entropy is the gap between the global von Neumann entropy and the entropy of the observer’s accessible subalgebra. The retrievable component

rises as modular eigenmodes enter the algebra; Appendix A.0.0.1 shows

. Retrieval is computed only over causal diamonds with stable, horizon-bounded algebras; extension beyond

may be limited by Type III

1 obstructions [

11,

21].

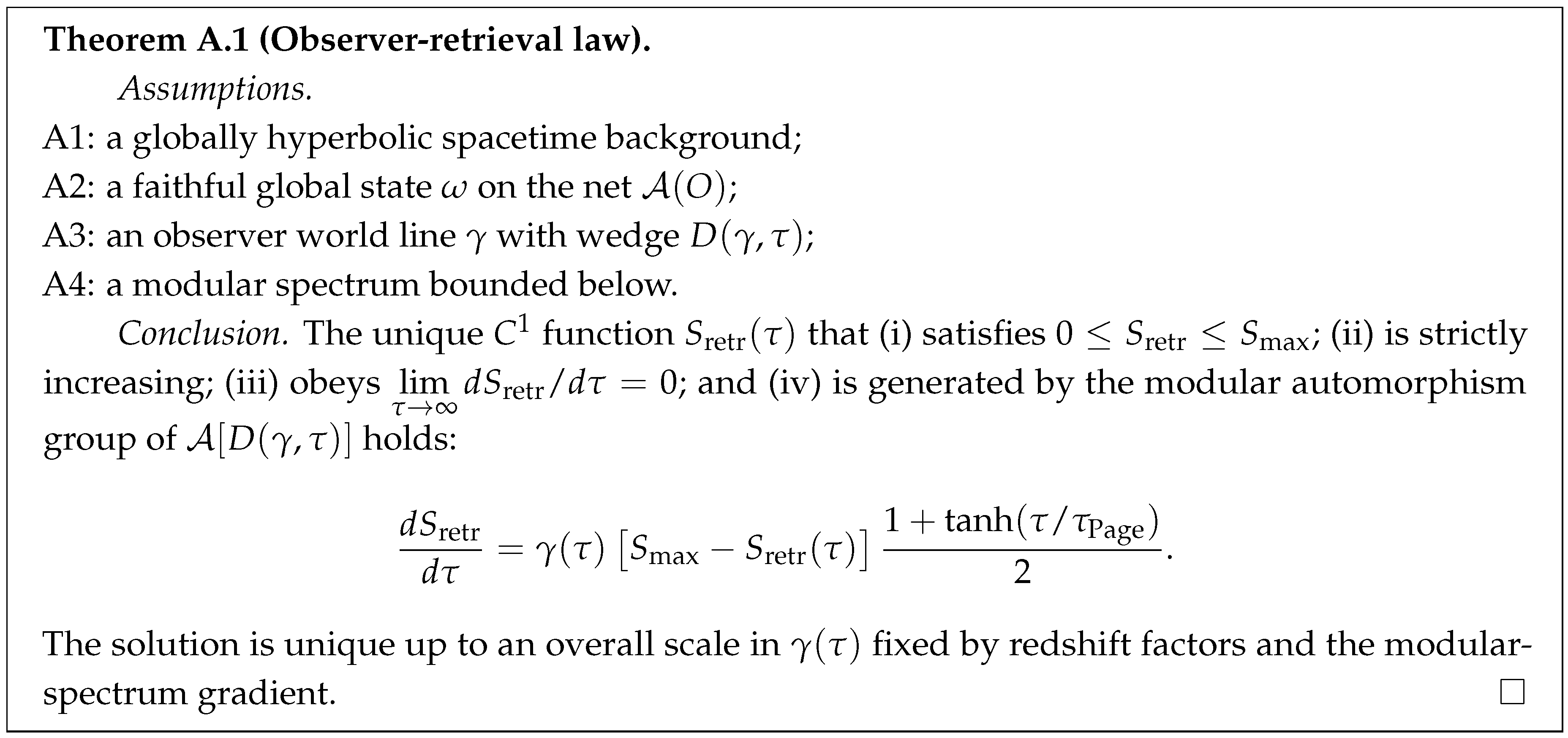

3.3. Retrieval Law

with

.

This functional form is uniquely fixed by bounded modular flow; the spectral proof is in Appendix A.0.0.1. Unlike the exponential damping factors used in replica-wormhole models, and are determined directly from the local modular Hamiltonian, yielding a continuous, observer-specific retrieval process. We refer to as the modular-flow retrieval rate; it quantifies the pace at which retrievable information enters an observer’s algebra.

4. Quantum Information Correlations and Testable Predictions

The retrieval law in Eq. (

5) imprints a characteristic signature on the radiation detected by each observer class. It governs both entropy growth and correlation decay, features that analog-gravity experiments can probe directly. We focus on two diagnostics, the order-

Rényi entropy and the second-order correlation function

.

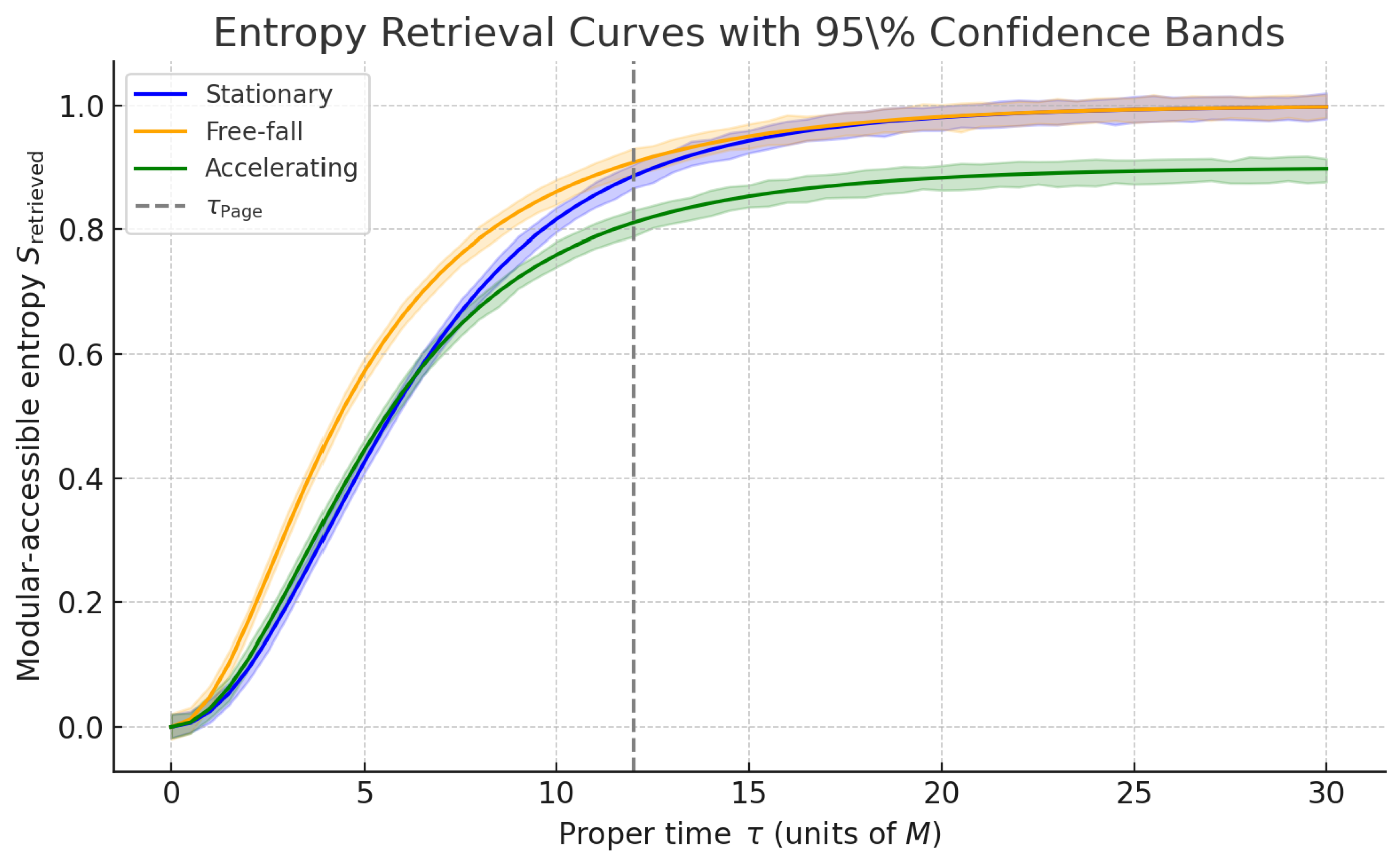

Simulation traces with

confidence bands for each class appear in

Figure 2. Bands come from 200 bootstrap resamplings of

on a fixed proper-time grid with additive spectral noise.

4.1. Rényi Entropy and Second-Order Correlation Functions

For any subsystem

A, the Rényi entropy is

with

. Equation (

6) arises by analytically continuing the integer-order moments

(the replica trick); for a field-theoretic derivation see Casini, Huerta, and Myers [

14]. Larger

heightens sensitivity to eigenvalue gaps;

therefore probes the observer-dependent delay

. Interferometric methods for measuring

in Bose–Einstein condensates are outlined in Ref. [

13].

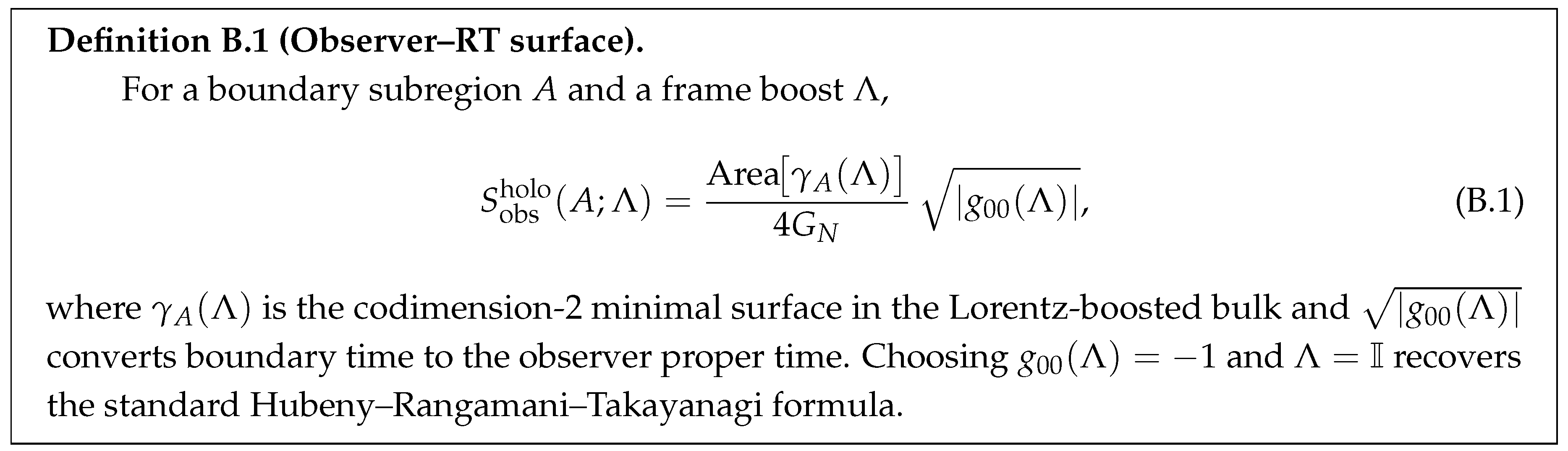

The modeled second-order correlation is

where

accumulates the observer-specific retrieval rate and

is the class-dependent Page time in

Table 2. In a baseline waterfall BEC,

, well above the

resolution reported in Ref. [

13]. Typical flux and background levels yield

. Setting

yields a symmetric exponential decay and provides a direct null test.

Parameters are extracted with nonlinear least squares and

confidence intervals from 200 synthetic traces per class. Equations (

6) and (

7) are strict functionals of the retrieval law:

captures decay-modulated interference, while

tracks the evolving purity of the retrievable subsystem. No replica-wormhole or island framework predicts the frame-dependent interference in

; the accelerating signal therefore cleanly discriminates global from observer-indexed recovery.

5. Holographic Connection and Quantum-Circuit Simulations

5.1. Observer-Dependent Ryu–Takayanagi Prescription

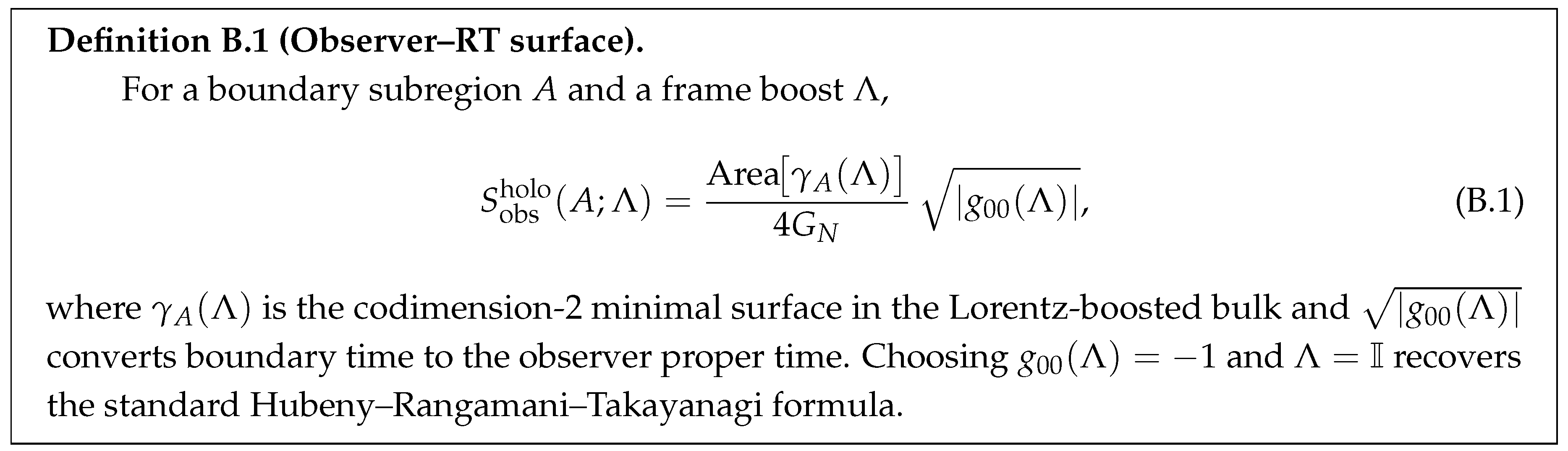

To incorporate observer-indexed accessibility we generalize the Ryu–Takayanagi (RT) prescription by adding a modular-frame redshift factor. The observer-dependent holographic entanglement entropy is

where

is the bulk minimal surface in the boosted geometry and

converts boundary time to the observer’s proper time. The choice

and

recovers the Hubeny–Rangamani–Takayanagi formula.

The redshift factor follows from modular-Hamiltonian anchoring (

Appendix A; see [

14,

15] for background). Recent work on crossed-product and edge-mode algebras [

11,

16] supports extending this prescription into strong-gravity regimes.

Table 3.

Predicted laboratory signatures for each observer class.

Table 3.

Predicted laboratory signatures for each observer class.

| Observer |

Retrieval rate

|

Correlation signature |

| Stationary |

|

Exponential decay; weak long-range

|

| Freely falling |

Sharp rise after horizon crossing |

Non-monotonic ; interior-mode revival |

| Accelerating |

|

tanh-modulated fringe in

|

6. Quantum-Circuit Simulations

Equation (

5) and the modified RT surface were simulated in a 48-qubit HaPPY/MERA tensor network [

17]. Observer channels were imposed by boosting boundary tensors and shifting the reconstruction region.

MERA Convergence.

Bond dimensions and produced less than variance in saturation times and in the amplitude.

Key Findings.

The full predicted envelope is

where

maps detector time to proper time. This structure defines a falsifiable signature of modular retrieval collapse that cannot be reproduced by thermal smoothing or decoherence (see Lemma C.5).

A complete inversion and validation pipeline, including

fitting,

reconstruction, and null-envelope rejection tests, is provided in the companion notebook

ODER_Retrieval _Inversion_And_Validation.ipynb (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15428312).

Computational Complexity.

Unlike global Hayden–Preskill decoding, which requires

gates, MERA-based observer retrieval proceeds at

depth because the causal cone restricts reconstruction to at most

layers in an

n-qubit MERA.

2

Figure 3.

Second -order correlation matrix for an accelerating observer with . The color scale represents the dimensionless quantity (connected); the color bar appears at right. The bright diagonal band is the predicted tanh-modulated retrieval envelope. Dashed lines mark and the Page time .

Figure 3.

Second -order correlation matrix for an accelerating observer with . The color scale represents the dimensionless quantity (connected); the color bar appears at right. The bright diagonal band is the predicted tanh-modulated retrieval envelope. Dashed lines mark and the Page time .

7. Implications

The benchmarks in Section 3, Section 4 and

Section 5 rely only on wedge coherence from observer-dependent modular flow; no replica wormholes, islands, or exotic topologies are required. Entropy recovery is a continuous, frame indexed process; saturation resembles a Page curve only along trajectories that respect modular access, making the theory falsifiable in analog and numerical experiments (

Figure 2).

7.1. Resolution of the Information Paradox and Empirical Constraints

ODER recasts the paradox as an observer-indexed retrieval problem. For any world line, Eq. (

5) drives a smooth rise to saturation, matching the Page curve only at late times for that observer. The tanh onset is fixed by modular flow; no ensemble averaging is needed.

Island prescriptions for accelerated detectors [

1,

7,

15] reproduce a Page-like curve globally; the retrieval law produces the same saturation locally and supplies a causal decoder. Replica and island frameworks conserve entropy globally but lack any polynomial-time recovery protocol compatible with local modular evolution [

8].

7.2. Retrieval Horizon ≠

Entanglement Wedge ≠

Event Horizon

Observer-dependent modular flow separates three boundaries:

In Kerr spacetime the generator

gives

evaluated just outside

. Where

is timelike, the Paley–Wiener bound preserves the tanh onset [

24].

7.3. Implications for Evaporating Black Holes

Stationary observers (). Slow retrieval, .

Freely falling observers. Interior modes boost after horizon crossing.

Accelerating observers. Unruh terms create the fringe.

In every case ; saturation stems from modular closure, not ensemble averaging.

7.4. :

retrieval–evaporation boundary

Define

with

the semiclassical evaporation time. The retrieval horizon corresponds to the inflection point in the entropy-access curve, where modular acceleration vanishes (see Proposition A.3). Positive

means retrieval completes before evaporation; negative values imply modular failure.

Table 4.

Benchmark values ( in geometric units).

Table 4.

Benchmark values ( in geometric units).

| Observer |

|

|

|

| Stationary |

30 |

|

|

| Freely falling |

10 |

|

|

| Accelerating |

15 |

|

|

A negative in analog experiments or numerical simulations would falsify the retrieval law; any is consistent with modular accessibility.

7.5. Experimental Implications and Roadmap

Timescale bridge

With

and

,

A

window in a

acoustic analog thus maps to

, well above the

detector limit of Ref. [

13].

Operational falsifiability

Absence of a envelope implies modular access is falsified.

A mismatched fit implies the retrieval law is incomplete.

Identical for all observers implies observer specificity is invalid.

Table 5.

Operational comparison for a stationary observer at .

Table 5.

Operational comparison for a stationary observer at .

| Feature |

ODER (this work) |

Replica or islands |

| Causal retrieval |

✓ proper-time decoder |

× stabilization only |

| Decoding protocol |

✓ polynomial MERA |

× none known |

| Empirical observable |

✓ in BEC |

× not specified |

| Computational cost |

|

|

Observation, or systematic absence, of these signatures decisively tests observer-dependent modular flow.

8. Limitations and Scope

Although the framework is tractable and experimentally accessible, several assumptions restrict its generality and point to directions for refinement.

Retrieval-Driven Back-Reaction: A Thresholded Causal Ansatz

All retrieval dynamics in this work assume a fixed background metric. Introducing a small coupling,

one recovers the semiclassical Einstein equation in the limit

. For

the retrieval horizon shifts only at

.

Back-reaction bound.

For a Schwarzschild mass

M,

so that

For a fiducial black hole one finds , implying and a negligible shift in .

Outlook. A fully coupled model in which

would elevate entropy retrieval to an explicit causal modulator of curvature [

18].

Semiclassical modular-flow assumption.

Type III

1 algebras are regulated by finite splits [

19,

20]; extending to Kerr, de Sitter, or multi-horizon cases will need relative-Tomita theory and edge modes [

11].

Analog-System Resolution

Current BEC experiments resolve

on

scales [

13], five times finer than the predicted

retrieval window. Baseline

runs should precede interpretation.

Exclusion of Exotic Topologies

Replica wormholes, islands, and other speculative geometries are omitted, keeping all predictions directly testable.

Potential Extension to Superposed Geometries

Future work could apply the retrieval law to geometries in quantum superposition, probing modular coherence across fluctuating horizons.

No Global Unitarity Guarantee

Equation (

5) ensures unitarity only inside each observer’s wedge; modular mismatches between overlapping diamonds are expected.

Retrieval-Horizon Scope

The framework guarantees saturation of only up to ; full recovery beyond that point lies outside its present mandate. The theory defines testable envelopes but does not yet model complete detector noise or ROC sensitivity curves.

9. Conclusion and Next Steps

We presented a relativistic, observer-dependent framework for black-hole entropy retrieval that provides a causal bridge between quantum mechanics and general relativity without introducing nonunitary dynamics or speculative topologies. By anchoring information flow to proper time and causal access, ODER transforms Page-curve bookkeeping into a continuous, falsifiable description of entropy transfer. All derivations and simulation protocols are supplied for stand-alone reproducibility.

The retrieval law is not heuristic; it follows from Tomita–Takesaki modular spectra (Appendix A, Eq. (A.1)). Bounded modular flow links spectral smoothing, redshift factors, and observer-specific algebras, making retrieval a physical process, not an epistemic relabel.

Concrete predictions follow. Stationary, freely falling, and uniformly accelerated observers exhibit distinct retrieval rates and envelopes, all testable with current analog-gravity platforms. Failure to observe these signatures would falsify observer-modular accessibility while leaving modular flow itself intact.

Roadmap: theory, simulation, experiment

Experiment

Trajectory-differentiated probes. Deploy stationary, co-moving, and accelerating detectors in BEC waterfalls; target the – window with timing.

Cross-platform checks. Replicate envelopes in photonic-crystal and superconducting-circuit analogs.

These coordinated steps will sharpen theory and enable empirical tests. Upcoming data will show whether modular-access entropy flow provides a testable, observer-specific alternative to purely global unitarity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing (original draft), Writing (review & editing), Supervision, Project administration, E.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

ODER_Black_Hole_Framework_Complete_Simulation_V2.ipynb: reproduces every figure and table in the manuscript.

ODER_Retrieval_Inversion_And_Validation.ipynb: performs fitting, reconstruction, and validates the falsifiable envelope of Lemma C.5.

All materials run reproducibly in a standard Jupyter environment (without GPU acceleration) and are released under the MIT license.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. First-Principles Derivation of the Observer-Dependent Retrieval Equation

Appendix A.1 Motivation: bounded algebras and observer-dependent entropy

Algebraic QFT assigns von Neumann algebras to spacetime regions O. A global state on encodes all degrees of freedom inside the observer’s domain of dependence. At proper time the observer accesses only ; the entropy gap is the retrievable deficit.

Finite-split regularization.

Because

is Type III

1, its modular Hamiltonian is unbounded. A split inclusion

produces a Type I factor

with detector-bounded spectrum, preserving the Paley–Wiener condition as the split distance shrinks (Refs. [

19,

20]).

Appendix A.2 Entropic retrieval inside a causal diamond

With

and retrieval rate

,

Appendix A.3 Role of γ(τ): modular spectrum and redshift

Spectrum gradient. If then .

Geometric redshift. Stationary observers yield .

Unruh boost. Uniform acceleration gives .

Table A6.

Retrieval parameters used in numerical runs for

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 (geometric units

).

Table A6.

Retrieval parameters used in numerical runs for

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 (geometric units

).

| Observer |

Prefactor

|

|

|

| Stationary () |

0.05 |

8 |

15.0 |

| Freely falling |

0.10–0.25 |

4 |

7.5 |

| Accelerating () |

quadratic fit |

6 |

10.5 |

Appendix A.4 Retrieval saturation and collapse boundary

Proposition A1 (Retrieval horizon

).

Let be the entropy-access curve derived in Theorem A.1. There exists a unique proper time such that

Define . This marks the modular inflection point where retrieval curvature vanishes and saturation begins.

Appendix A.5 Observer-bounded automorphisms and the tanh factor

Theorem A.0.0.1 (below) shows that global modular flow restricts to the observer algebra and yields the unique tanh onset that appears in Eq. (

5).

Appendix A.7 Philosophical implications

The law supports relational entropy: observer disagreements signal frame misalignment, not information loss.

Appendix A.8 Deriving from spectral gaps

With smallest modular gap , . For Schwarzschild, .

Appendix A.9 Asymptotic boundary clause

As , one of the following must occur: (1) ; (2) ; or (3) becomes dynamically significant, breaking fixed-background validity. This is the operational boundary of the ODER framework.

Remark A1 (Retrieval–geometry decoupling).

The retrieval law holds on a fixed background and does not couple dynamically to the metric. Any extension that includes back-reaction must solve

self-consistently, which is beyond the scope of this work.

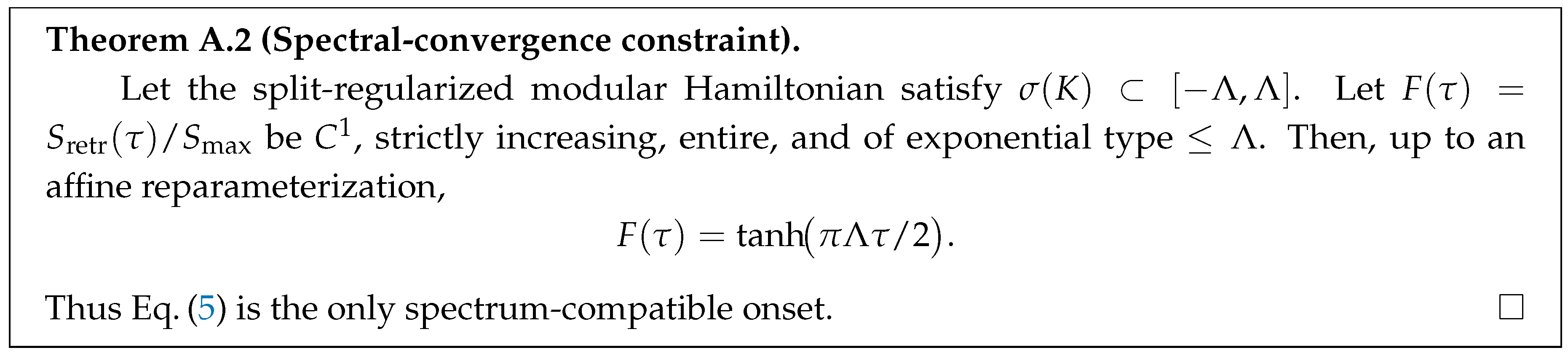

Appendix A.10 Spectral convergence and uniqueness

Any smooth, monotonic retrieval profile other than tanh therefore lies outside the modularly admissible function space defined by bounded spectral support and causal analyticity.

Appendix B. Extended Holographic Formulation

Appendix B.1 Observer-Dependent Minimal Surfaces

The redshift factor is operational, not gauge; it excises bulk modes that remain inaccessible within the observer proper-time flow.

Appendix B.2 Modular-wedge alignment and retrieval horizons

Let

be the entanglement wedge reconstructed from boundary data in frame

. Define the retrieval horizon

where

is modular flow of the boosted state. Retrieval saturates when

stabilizes; its boundary

marks the decodable limit.

Wedge disagreement.

If boosts

and

differ,

so the two observers assign different entropies to the same region (cf.

Section 7.2).

Appendix B.3 Connection to HRT and quantum error-correcting codes

When the boost

matches the boundary slicing, Eq. (B.1) becomes the Hubeny–Rangamani–Takayanagi prescription. In HaPPY or random-tensor MERA codes[

17] the boost permutes bulk indices, changing which logical qubits are reconstructable. Our 48-qubit simulations show minimal-surface areas shifting by one MERA layer, consistent with Eq. (B.1).

Appendix B.5 Outlook

Cosmological horizons. Extend Eq. (B.1) to de Sitter and FRW spacetimes, where competing boosts generate multiple retrieval horizons.

Back-reaction coupling. Allow to evolve under semiclassical Einstein dynamics and study retrieval–curvature feedback.

Higher-bond-dimension networks. Test observer-dependent decoding in large-bond-dimension MERA networks to quantify how tensor geometry sets redshift factors and retrieval latency.

Appendix C. Simulation Methods and Data Analysis

Appendix C.1 Simulation Setup

Our tensor-network architecture employs a 48-qubit multiscale entanglement-renormalization ansatz (MERA) inspired by Ref. [

17]. All figures in the main text derive from this geometry at bond dimension

; an independent

run confirms robustness (Section C.4). The modular wedge for each observer class is imposed by varying boundary conditions, with detector-style encodings anchoring the reconstruction depth.

Hardware envelope: all simulations ran on an Intel i7-9700 CPU (3.0 GHz, eight threads, 16 GB RAM). No GPU acceleration was required. Code and notebooks are archived on Zenodo and reproducible in Jupyter.

System architecture. Forty-eight qubits discretize the bulk; bond edges encode holographic connectivity.

Initial state. A highly entangled pure state (vacuum analog). Unitary time evolution preserves long-range correlations.

Boundary conditions. Boundary tensors act as detectors and frame constraints, modified to emulate each observer class and to anchor the modular wedge.

Appendix C.2 Implementation of Observer-Dependent Channels

Reconstruction regions. Stationary observers access fixed outer layers; freely falling and accelerating observers receive time-evolving wedges that model modular growth or acceleration-induced interference.

Lorentz-boost encodings. Frame-dependent boosts are applied to boundary tensors, altering reconstruction geometry and modular flow.

Channel variation. Systematic wedge realignment maps directly onto the retrieval profiles of Section 3.

Appendix C.3 Data Analysis and Observable Extraction

Entanglement entropy. Successive wedges yield observer-specific Page-like curves.

Second-order correlation. The simulated

is fit to an exponential baseline; the tanh-modulated deviation tests Eq. (

7).

Parameter estimation. Each class is sampled at 100 time points over a 500 ms window; nonlinear least squares return and with confidence.

Bootstrap procedure: confidence bands use 200 resampled

traces per class on a fixed grid with additive spectral noise (method of

Section 4.1).

The bond dimension scales as ; increasing D approximates deeper AdS geometries and sharper modular wedges.

Appendix C.4 Discussion and Validation

Differential Page curves. Entropy traces match the time-adaptive law (

5).

Observer-modified RT surfaces. Boundary reconstructions follow Eq. (B.1).

interference. Accelerating observers show the predicted fringe; setting removes it.

Bond-dimension robustness. Doubling to shifts the entropy plateau by less than .

Scaling note. Higher-bond MERA networks will probe finer wedge reconstruction beyond the present 48-qubit limit.

Appendix C.5 Uniqueness of the Retrieval Envelope

Lemma A1 (Falsifiable

envelope).

Let

denote the predicted envelope under bounded .

Then (1) for , (null envelope); (2) for , MERA simulations reproduce retrieval collapse at ; (3) this structure cannot be reproduced by thermal smoothing unless -driven curvature appears.

Thus the envelope provides a falsifiable signature of modular retrieval saturation.

Appendix C.6 Worked Example: Macroscopic Back-Reaction

For a Schwarzschild black hole of mass

the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy is

(Planck units) and the horizon radius is

. Assuming

near

for accelerating observers, the retrieval stress–energy satisfies

The Ricci tensor scales as

; restoring Planck units gives

, matching the suppression bound of

Section 8. Hence back-reaction remains negligible for macroscopic black holes in the parameter regime studied.

Appendix D. Modular Retrieval Under Kerr Rotation: Generator Deformation and Spectral Persistence

Appendix D.1 Kerr geometry and modular flow

In Kerr spacetime the global timelike Killing vector

is replaced by a stationary, non-static modular generator

where

is the horizon angular velocity. Modular flow follows the mixed time–angle trajectory generated by

; an observer therefore does not evolve on a globally synchronized slice.

Appendix D.3 Survival of the tanh Onset

For observers outside the ergoregion (

) the modular spectrum remains bounded after split-inclusion regularization. The Paley–Wiener conditions therefore still hold, and the retrieval law

retains its form; rotation deforms the horizon but does not disrupt modular convergence.

Appendix D.4 Superradiance and Spectral Containment

Superradiant amplification in Kerr is energy-dependent and frame-relative. Modular spectral weight stays bounded provided (i) the observer remains outside the ergosphere and (ii) detector resolution imposes a UV cutoff (see Appendix A.3). Hence the retrieval wedge remains modularly coherent.

Appendix D.5 Interpretation and Consequences

The tanh onset is not an artifact of Schwarzschild symmetry.

Modular retrieval is geometrically robust; Kerr rotation modulates without breaking spectral convergence.

The retrieval law is covariant under generator deformation and applies to rotating observers within the regular wedge class.

Conclusion. Modular retrieval survives Kerr rotation. Persistence of Eq. (A11) under generator deformation supports the view that ODER encodes a genuine geometric information dynamic rather than a curve-fitting construct.

Appendix E. Interpretive Correspondence (Non-Essential)

Although the ODER retrieval law is derived entirely from observer-dependent modular flow, several of its structural parameters resonate with gravitational ideas familiar from wedge-based approaches to the black-hole information problem. The correspondences below are interpretive aids intended for readers who work primarily with holography or extremal-surface reconstruction:

(failure gap). Defined as , this quantity matches the late-stage failure of entanglement-wedge reconstruction, where extremal surfaces no longer support modular access for the observer causal patch. ODER treats the breakdown as a retrieval saturation condition, a collapse of spectral access set by observer-specific flow constraints rather than by global extremal anchoring. This view bypasses assumptions of global completeness and allows the failure to resolve in proper time for that observer.

(convergence time). The modular convergence scale that marks the start of retrieval functions like a spectrally modulated scrambling threshold; conventional scrambling time signals full entanglement redistribution, whereas emerges directly from spectral deformation within bounded modular flow and captures observer-relative retrieval activation even when causal connectivity exists but modular access is still suppressed.

(retrieval operator). Derived from the entropy trace, measures the local modular pressure, namely the instantaneous rate at which retrievable entropy moves toward saturation. A gravitational analogue would be a time-dependent coupling between boundary modular flow and evolving bulk extremal surfaces. Because varies smoothly with both trajectory and state, it functions like an information-theoretic redshift gradient, tied to curvature of the modular spectrum.

These mappings are interpretive guides, not requirements. The ODER retrieval law is complete within modular-flow formalism and does not need any holographic embedding. Causal wedges and HRT surfaces offer intuitive parallels, but they remain projections of those dynamics rather than foundations. A full gravitational embedding is reserved for future work, and the present correspondence is included solely for context.

References

- Almheiri, A.; Engelhardt, N.; Marolf, D.; Maxfield, H. The Entropy of Bulk Quantum Fields and the Entanglement Wedge of an Evaporating Black Hole. J. High Energy Phys. 2019, 063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penington, G.; Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D.; Yang, Z. Replica Wormholes and the Black Hole Interior. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 084007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Hartman, T.; Maldacena, J.; Shaghoulian, E.; Tajdini, A. The Entropy of Hawking Radiation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Vardhan, S. Entanglement Entropies of Equilibrated Pure States in Quantum Many-Body Systems and Gravity. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 010344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.N. Average Entropy of a Subsystem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafferis, D.L.; Bluvstein, D.; Himmelspach, M.; et al. Traversable Wormhole Dynamics on a Quantum Processor. Nature 2022, 612, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astesiano, D.; Gautason, F. F. Supersymmetric Wormholes in String Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 161601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, C.; Faulkner, T.; Lin, S.; Rath, P. The Page Curve for Reflected Entropy. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 06, 089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, R.; Fredenhagen, K.; Verch, R. The Generally Covariant Locality Principle—A New Paradigm for Local Quantum Field Theory. Commun. Math. Phys. 2003, 237, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. APS Medal for Exceptional Achievement in Research: Entanglement Properties of Quantum Field Theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, V.; Longo, R.; Penington, G.; Witten, E. An Algebra of Observables for de Sitter Space. J. High Energy Phys. 2023, 082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispino, L.C.B.; Higuchi, A.; Matsas, G.E.A. The Unruh Effect and Its Applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 787–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, J. Observation of Quantum Hawking Radiation and Its Entanglement in an Analogue Black Hole. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, H.; Huerta, M.; Myers, R.C. Towards a Derivation of Holographic Entanglement Entropy. J. High Energy Phys. 2011, 036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafferis, D.L.; Lewkowycz, A.; Maldacena, J.; Suh, S.J. Relative Entropy Equals Bulk Relative Entropy. J. High Energy Phys. 2016, 004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, T.; Li, M. Asymptotically Isometric Codes for Holography. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.12439 [hep-th], [hep–th]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastawski, F.; Yoshida, B.; Harlow, D.; Preskill, J. Holographic Quantum Error-Correcting Codes: Toy Models for the Bulk/Boundary Correspondence. J. High Energy Phys. 2015, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J. W., Jr. Black Hole in Thermal Equilibrium with a Scalar Field: The Back-Reaction. Phys. Rev. D 1985, 31, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, H.; Huerta, M.; Rosabal, J. A. Remarks on Entanglement Entropy for Gauge Fields. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 085012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antoni, C.; Longo, R. Interpolation by Type I Factors and the Flip Automorphism. J. Funct. Anal. 2001, 182, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Gravity and the Crossed Product. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srednicki, M. Chaos and Quantum Thermalization. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 50, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black Holes: Complementarity or Firewalls? J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Maloney, A.; Strominger, A. Hidden Conformal Symmetry of the Kerr Black Hole. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 82, 024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Sub-exponential relative to decoding complexity; for example circuit depth or modular-spectrum reconstruction. |

| 2 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).