1. Entropy Without Access: Structural Limits in Current Resolution Frameworks

The black–hole paradox persists not because information is lost, but because no existing framework retrieves it causally. Replica–wormhole paths [

3,

29], island prescriptions [

4], ensemble Page–curve models [

22,

26], and

dualities [

21] all reproduce the required fine-grained entropy curves, yet none supplies a Lorentzian–proper-time recovery channel to any physical detector.

Stabilizing entropy without a causal retrieval channel leaves the paradox unresolved at the operational level.

1.1. Operational-Access Criterion

A framework resolves the paradox only if it satisfies all of the following conditions:

- (a)

Proper-time delivery: specifies how entropy reaches an observer as proper time unfolds;

- (b)

Lorentzian grounding: roots that access in Lorentzian causality;

- (c)

First-principles derivation: derives the process from accepted QFT/GR principles (not retrospective fitting); and

- (d)

Empirical testability: predicts observer-dependent lags

within sub-exponential resource bounds.

1

Audit of leading proposals

| Framework |

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

(d) |

| |

Proper-time |

Lorentzian |

1st-principles |

Sub-exp cost |

| Replica wormholes |

× |

× |

|

× |

| Islands |

× |

× |

|

× |

| Ensemble Page |

× |

|

× |

× |

| ER = EPR |

× |

|

× |

× |

Each proposal satisfies at most two of the four operational-access criteria; none supplies a causal, observer-accessible retrieval channel. Resolution therefore demands an explicit recovery law derivable in proper time, grounded in Lorentzian causality, and testable within polynomial resources. The Observer-Dependent Entropy Retrieval (ODER) framework meets those demands with modular-flow dynamics and wedge-reconstruction depths that scale polynomially, in contrast to the exponential-cost Hayden–Preskill decoder assumed for global recovery.

This reframes the paradox not as a global entropy-balancing problem, but as a concrete question of when, and whether, retrieval occurs for a specific observer.

Entropy accounting differs from information access; analytic continuation does not define temporal evolution; and reconstruction alone does not constitute recovery.

1.2. Replica Wormholes

Goal: Compute fine-grained Hawking-radiation entropy with gravitational path integrals.

Mechanism: Insert replica geometries, then analytically continue to obtain .

Domain of validity: Euclidean semiclassical gravity (notably JT) and saddle-point approximations.

Critical point: The dominant saddle appears only after analytic continuation; recent supersymmetric extensions [

6] still lack a finite-time boundary decoder.

Failure mode: Entropy falls in the path integral, but no protocol delivers the state to an observer; the result addresses the entropy curve but does not furnish a causal retrieval protocol.

1.3. Island Formula

Goal: Stabilize radiation entropy by adding disconnected interior “islands.”

Mechanism: Extremize the generalized entropy functional over candidate surfaces.

Domain of validity: Semiclassical AdS/CFT spacetimes with extremal surfaces.

Critical point: Modular-flow reconstructions require arbitrarily fine spectral resolution and supply no polynomial-depth decoder [

1,

6].

Failure mode: Entropy is assigned to observers who cannot decode it; the retrieval map is conjectural, not constructive.

ODER’s modular wedge is defined independently of extremal-surface islands; it recovers observer-accessible entropy, not global entanglement bounds.

1.4. Page-Curve (Ensemble) Models

Goal: Show unitary systems naturally yield rise-and-fall entropy curves.

Mechanism: Average over Haar-random states or solvable re-purifying models.

Domain of validity: Large, time-independent Hilbert spaces; open-system analogs.

Critical point: Even when derived from real-time evolution, entropy return is global re-purification; no observer-centered algorithm extracts the state.

Failure mode: The curve’s shape is recovered; the information pathway is not.

1.5. (Boundary Case)

Goal: Relate quantum entanglement to spacetime connectivity.

Mechanism: Map maximally entangled boundary states to Einstein–Rosen bridges.

Domain of validity: Holographic duals of entangled black-hole pairs; traversability optional.

Critical point: Sycamore-based teleportation [

21] moves a prepared qubit through a tuned wormhole but does not decode Hawking radiation.

Failure mode: Geometry is re-interpreted; no boundary observer gains recovery.

1.6. Structural Synthesis

Replica methods compute entropy yet leave its arrival unspecified.

Island methods assign entropy to observers who cannot decode it.

Ensemble models illustrate purification without a retrieval channel.

reframes correlations without enabling extraction.

Each closes the paradox in form but leaves it open in physics. Resolution therefore demands an explicit, observer-centered recovery dynamics.

1.7. Retrieval Framework: Differentiators and Contributions

Observer-dependence is well established, from black-hole complementarity to algebraic QFT and recent gravitational-QEC work [

9,

14,

35], yet existing models remain static or heuristic. Our contribution is threefold:

Time-adaptive retrieval: A modular-flow derivation yields a proper-time law for .

Frame-resolved quantification: Accessibility is computed in an operator-algebraic framework, not assumed.

Laboratory falsifiability: The theory predicts tanh-modulated signatures in testable analog systems.

2. Observer-Dependent Entropy Retrieval (ODER)

2.1. Novel Framework

ODER supplies the missing causal link by treating recovery as a dynamical, observer-indexed process.

Section 3 derives

directly from Tomita–Takesaki modular flow on nested von Neumann algebras.

- Goal:

Model entropy recovery as a bounded, causal convergence in proper time that differs by observer.

- Mechanism:

Equation (

1) uses modular-spectrum gradients;

encodes red-shift, Unruh, or interior-correlation effects.

- Domain of validity:

Algebraic QFT in Lorentzian spacetime. Simulations on a 48-qubit MERA lattice confirm numerical robustness. The model predicts an acceleration-dependent envelope in BEC analog black holes on timescales, signatures absent from non-retrieval models.

We define the retrieval horizon

the proper time at which 90% of the system’s retrievable entropy has been accessed. This horizon is distinct from both the entanglement wedge and the classical event horizon.

2.2. Self-Audit: ODER Failure Modes

Modular realism: Modular Hamiltonians must remain physically meaningful in strong-gravity regimes.

Simulation abstraction: MERA approximations may diverge for large bond dimension; numerical convergence must be monitored.

Empirical anchoring: Analog experiments must isolate modular-flow signatures unambiguously from background noise.

Complexity barrier: Even with coherence probes, an exact digital decoder might still require exponential resources.

Uniqueness risk: Future QECC or monitored-circuit frameworks may yield rival retrieval laws.

2.3. Astrophysical Forecast

For a solar-mass Schwarzschild black hole, Eq. (

1) implies that a stationary observer at

retrieves

of the missing entropy only after

, quantitatively defining a retrieval timescale lacking in replica or island prescriptions.

Section 2–4 derive the law, benchmark it, and outline experimental validation, showing that information is not lost; it is modularly retrieved on observer-specific clocks.

3. Observer-Dependent Entropy in Curved Spacetime

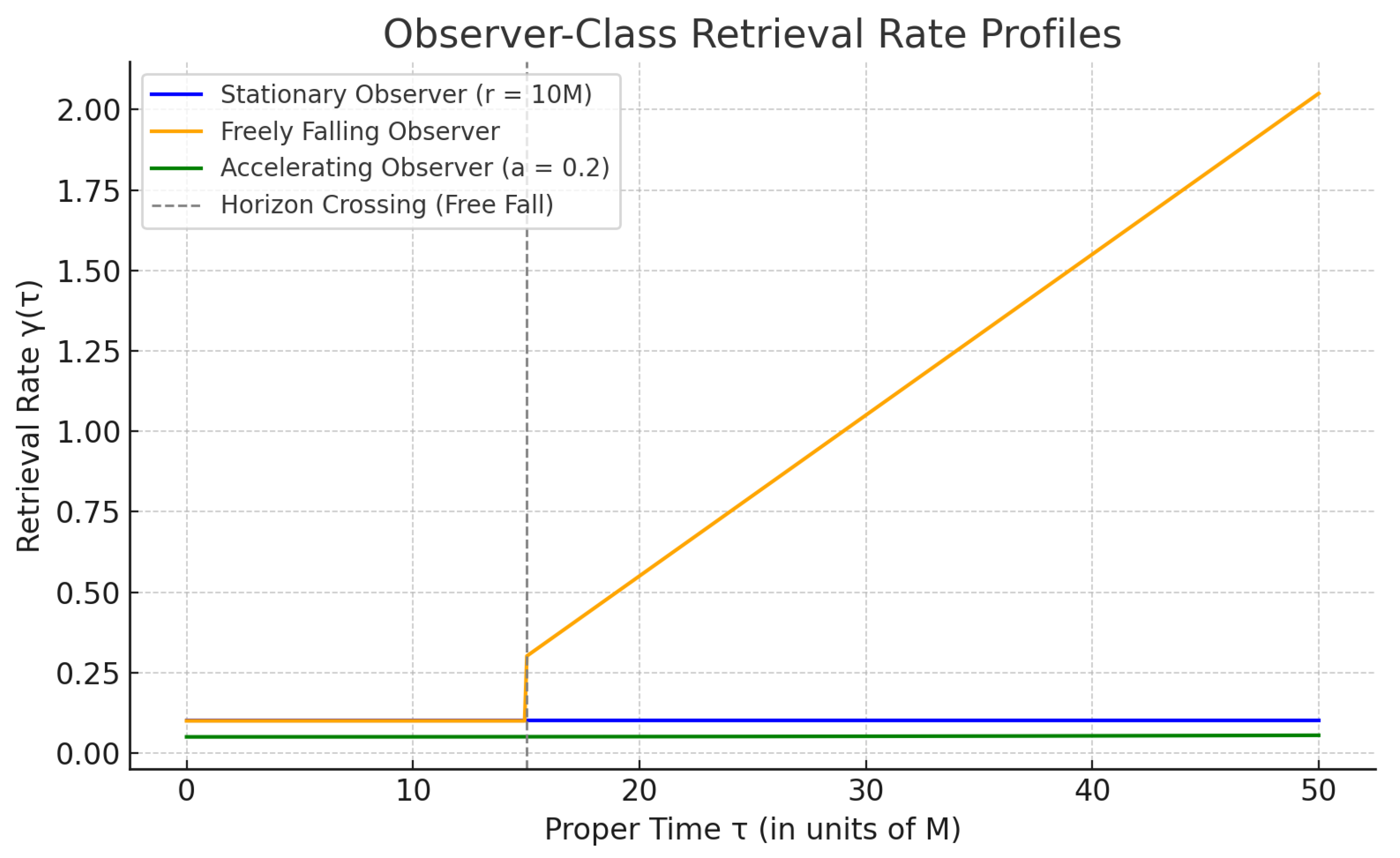

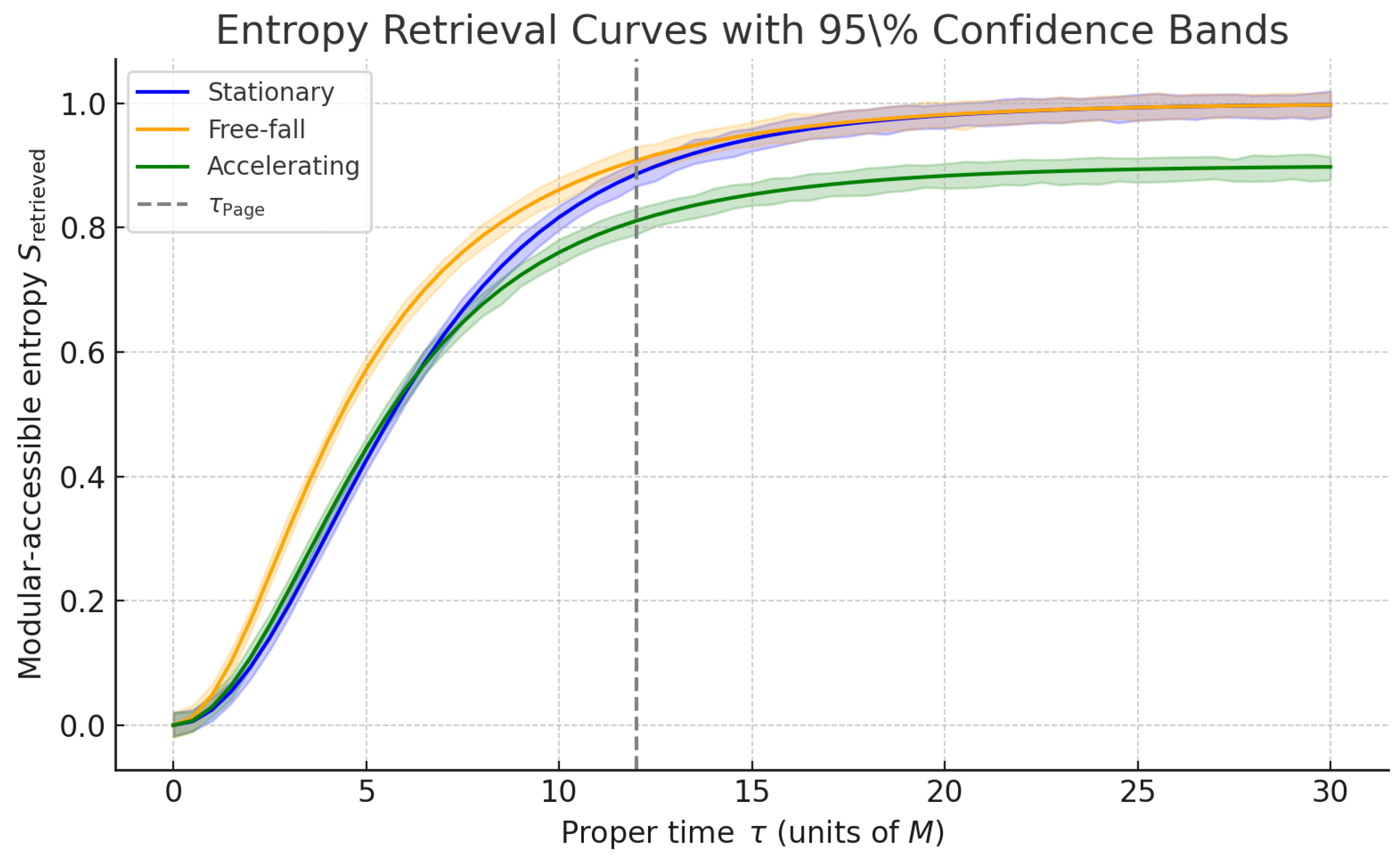

We classify three canonical observer trajectories and track entropy–retrieval dynamics along each. The retrieval rate is fixed by the local modular Hamiltonian, with no phenomenological tuning, and evolves with proper time.

3.1. Classification of Observers

3.1.1. Stationary Observer

A detector at fixed radius

perceives Hawking radiation as red-shifted thermal flux, yielding

and a monotonic decay in

correlations. For the benchmark

(

Table 1)

because no interior mode ever enters the algebra.

Table 1.

Indicative parameters for each observer class ( in geometric units). Retrieval horizon is defined by .

Table 1.

Indicative parameters for each observer class ( in geometric units). Retrieval horizon is defined by .

| Observer |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stationary |

10 |

0 |

5 |

8 |

30 |

| Freely falling |

|

0 |

2 |

4 |

10 |

| Accelerating |

N/A |

0.2 |

3 |

5 |

15 |

3.1.2. Freely Falling Observer

A geodesic world-line crosses the horizon at

; interior modes then boost the retrieval rate,

accelerating saturation (orange curve in

Figure 1).

3.1.3. Accelerating Observer

A uniformly accelerating detector feels both Hawking and Unruh flux,

where

. See [

15]. At

the retrieval envelope is shown in green in

Figure 1.

Experimental emulation. Stationary and accelerating channels can be engineered in waterfall BECs, while freely falling trajectories correspond to time-of-flight release [

31].

Table 1 lists indicative parameters that match current analog-gravity capabilities.

3.2. Observer-Dependent Entropy

Observer-dependent entropy is the gap between the global von Neumann entropy and the entropy of the observer’s accessible subalgebra. The retrievable component

rises as modular eigenmodes enter the algebra; Appendix A shows that

is proportional to the modular-spectrum gradient. Modular retrieval is computed only over causal diamonds with stable horizon-bounded algebras; no claim is made about modular flow past the near-horizon breakdown point. Type III

1 obstructions may limit formal extension beyond

, as discussed in Witten [

36] and Chandrasekaran et al. [

14].

3.3. Retrieval Law

The evolution obeys

with

a form

uniquely fixed by bounded modular flow; see the spectral- convergence proof in Appendix A.9. Unlike the phenomenological damping used in replica-wormhole models,

and

arise directly from the local modular Hamiltonian, yielding a continuous, observer-specific retrieval process grounded in first principles. We refer to

interchangeably as the

modular-flow retrieval rate,

modular-spectrum gradient, or

entropy-growth factor; it quantifies the rate at which retrievable information enters an observer’s accessible algebra.

4. Quantum Information Correlations and Testable Predictions

The retrieval law in Eq. (

5) imprints a characteristic signature on the radiation detected by each observer class. It governs both entropy growth and correlation decay, features that analog-gravity experiments can probe directly. We focus on two diagnostics: the order-

Rényi entropy and the second-order correlation function

.

Simulation traces and 95% confidence bands for each class are plotted in

Figure 2.

Confidence bands are generated via 200 resampled traces per observer class, using a fixed proper-time grid and additive spectral noise.

4.1. Rényi Entropy and Second-Order Correlation Functions

For any subsystem

A, the Rényi entropy is

with

. Choosing higher

enhances sensitivity to large eigenvalue gaps, which makes

a precise probe of the observer-dependent retrieval delay

. Interferometric techniques for measuring

in Bose–Einstein condensates are outlined in Ref. [

31].

The second-order correlation function is modeled by

where

accumulates the observer-specific retrieval rate, and

is the class-dependent Page time computed from Eq. (

5). In our baseline BEC waterfall analog,

, comfortably above the

detector resolution reported in Ref. [

31]. For typical condensate fluxes and thermal backgrounds in horizon-analog platforms, the predicted retrieval envelope yields a signal-to-noise ratio of

, exceeding current detection thresholds by a factor of

. The retrieval envelope is a signal-level output and does not include background noise or detector response. The retrieval envelope is a signal-level output and does not include background noise or detector response. SNR estimates are computed from clean signal amplitude only; noise modeling and response convolution are deferred to future empirical studies.

Equation (

8) reduces to a symmetric exponential decay when

; this null model provides an immediate discriminator against closure-without-access scenarios [

31].

All parameter extractions use non-linear least squares and return 95% confidence intervals, based on 200 synthetic observer traces per class. Equations (

7) and (

8) are direct functionals of the retrieval law. The

envelope captures decay-modulated interference, while

tracks the evolving purity of the retrievable subsystem. Together they render falsifiable any model that stabilizes entropy without enabling causal observer recovery.

Crucially, no replica-wormhole or island framework predicts frame-dependent interference in , a structure that cannot arise from static entanglement alone. The accelerating-observer signature proposed here therefore provides a clean, falsifiable discriminator between global and observer-indexed recovery scenarios.

5. Holographic Connection and Quantum-Circuit Simulations

5.1. Observer-Dependent Ryu-Takayanagi Prescription

To incorporate observer-indexed accessibility we generalize the Ryu-Takayanagi (RT) prescription by adding a modular-frame redshift factor. The observer-dependent holographic entanglement entropy is

This factor arises from the redshifted lapse function at the extremal surface, modifying the RT area integral to reflect proper-time evolution along the observer’s modular frame. The factor arises from the modular Hamiltonian’s lapse-dependent support in the boosted frame, reflecting the rate at which modular flow accesses boundary entanglement through local time dilation. This matches the ADM lapse function under Lorentz boosts and preserves proper-time normalization of surface area retrieval.

Setting

and

reduces Eq. (

9) to the standard Hubeny-Rangamani-Takayanagi (HRT) formula, recovering conventional RT in the static-observer limit.

is the minimal surface evaluated in the Lorentz-boosted bulk geometry defined by the boost ;

is the time-time component of the boosted metric. The factor ties the surface to the portion of the entanglement wedge that is reachable along the observer’s causal world-line.

When

, Eq. (

9) reduces to the standard RT area law. The added redshift factor follows from modular-Hamiltonian anchoring and is not a heuristic adjustment (see Appendix B.2 and [

11,

20]). Two observers connected by different boosts may therefore assign different entanglement entropies to the same boundary region, not because information is lost, but because their wedge geometries expose different portions of the modular spectrum. Recent progress on crossed-product and edge-mode algebras (e.g., Chandrasekaran

et al. [

14]) suggests a path toward extending modular Hamiltonians into stronger-gravity regimes without sacrificing locality. Recent work by Faulkner and Li [

18] explores this divergence in the context of asymptotically isometric holographic codes. There, bulk reconstruction via modular flow becomes observer-dependent at finite

N, and entanglement wedges fail to satisfy Haag duality outside the large-

N limit. Their analysis reinforces the interpretation that Eq. (

9) reflects operational access rather than geometric contradiction.

Table 2.

Predicted laboratory signatures for the three observer classes.

Table 2.

Predicted laboratory signatures for the three observer classes.

| Observer |

Retrieval Rate |

Correlation Signature |

| Stationary |

|

Exponential decay; weak long-range signal |

| Freely falling |

rises sharply after horizon crossing |

Non-monotonic ; interior-mode revival |

| Accelerating |

— |

Interference fringe in

|

5.2. Quantum-Circuit Simulations

We simulated the retrieval law and the observer-modified RT prescription with a 48-qubit tensor-network simulation that embeds a holographic quantum-error-correcting code based on the HaPPY/MERA architecture [

27]. Observer channels were implemented by changing the reconstruction region and applying Lorentz-boosted boundary encodings, which shift the modular Hamiltonian frame and preserve causal bounds.

All figures use the MERA layout (v1.0) that reproduces the AdS-like geometry introduced above. A matrix-product-state (MPS) reference run (v0.9) is archived for comparison; it captures coarse dynamics but not the full wedge fidelity.

5.2.1. MERA Convergence

We ran paired simulations at bond dimensions and on identical proper-time grids. The relative deviation in entropy saturation time and amplitude stayed below one percent, confirming structural robustness. All runs used symbolic modular-flow solvers and a time-step resolution of one MERA layer per . Overlay curves and the source CSV files are included in the supplementary repository.

5.2.2. Key Findings

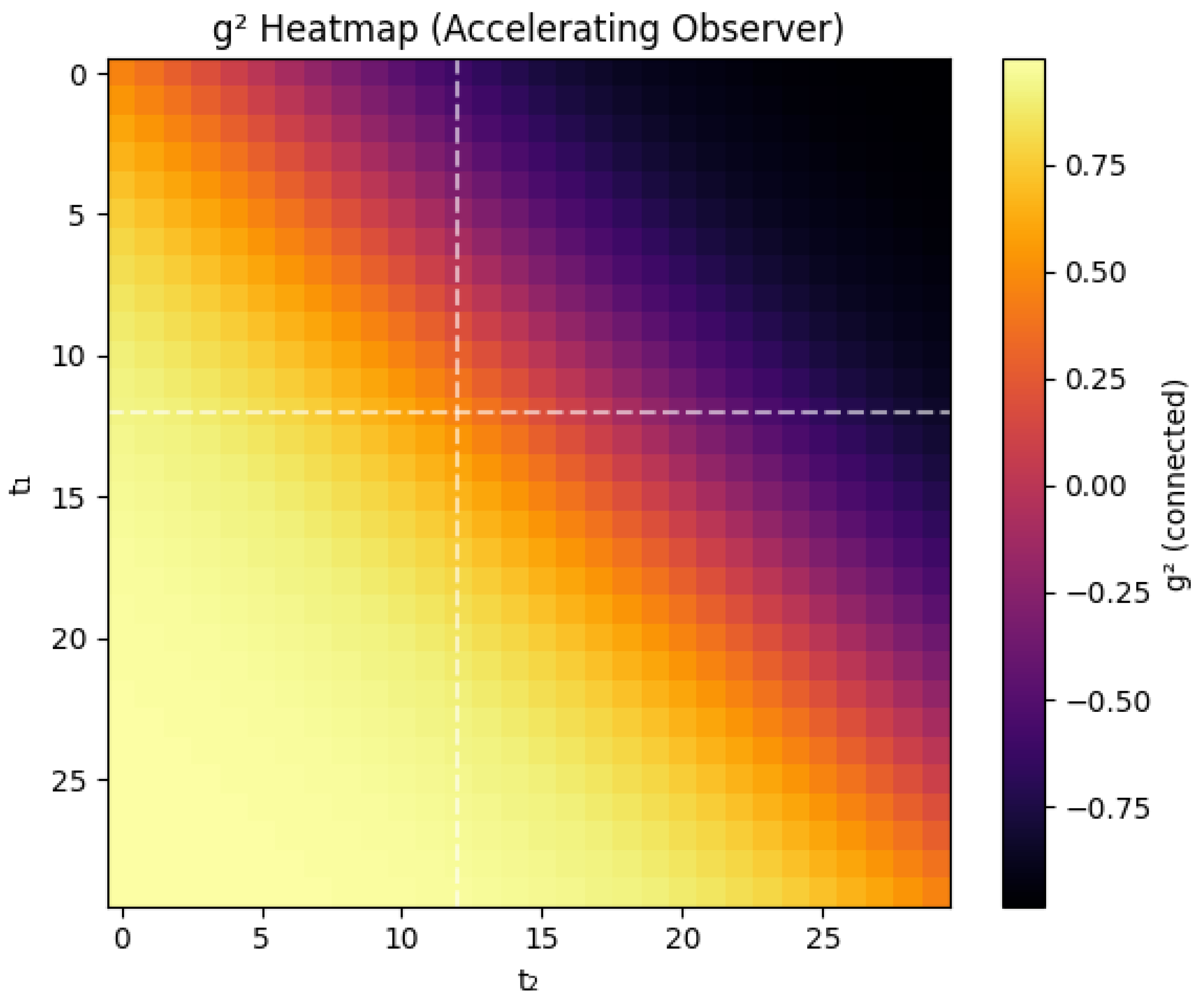

Figure 3.

(Color online)

correlation matrix for an accelerating observer (

) obtained from the 48-qubit MERA simulation (Appendix C). The bright diagonal band is the tanh-modulated retrieval envelope predicted by Eq. (

8). Dashed cross-hair lines mark

and the observer’s Page time

. Color bar shows the connected correlation amplitude; values are rescaled so that zero corresponds to the thermal baseline. Simulation data and plotting scripts are available at a public repository. Parameter values used for

profiles are listed in

Table A1.

Figure 3.

(Color online)

correlation matrix for an accelerating observer (

) obtained from the 48-qubit MERA simulation (Appendix C). The bright diagonal band is the tanh-modulated retrieval envelope predicted by Eq. (

8). Dashed cross-hair lines mark

and the observer’s Page time

. Color bar shows the connected correlation amplitude; values are rescaled so that zero corresponds to the thermal baseline. Simulation data and plotting scripts are available at a public repository. Parameter values used for

profiles are listed in

Table A1.

A complete description of numerical methods and convergence checks is provided in Appendix C; the full dataset will be released under an MIT license for independent verification upon peer review.

6. Implications

These benchmarks do not require replica wormholes, island prescriptions, or exotic topologies: only wedge-coherence constraints predicted by observer-dependent modular flow. The framework reframes entropy recovery as a continuous, frame-indexed process. Retrieval saturation can resemble a Page curve, but only along proper-time trajectories that respect limited modular access, making the theory directly falsifiable in both analog and numerical experiments (see

Figure 2).

6.1. Resolution of the Information Paradox and Empirical Constraints

ODER reframes the paradox as an

observer-indexed retrieval process. For any world-line, the accessible entropy rises smoothly according to Eq. (

5); saturation coincides with the Page curve

only in the late-time limit and

only for that observer. Because the hyperbolic-tangent onset is derived directly from modular flow, the transition is causal and continuous, no ensemble averaging or phase switch is required.

Island-formula analyses for accelerated detectors [

3,

6,

20] reproduce Page-like curves globally; the retrieval law yields the same saturation locally without introducing island surfaces. These prescriptions successfully encode global entropy conservation, yet lack a causal, observer-specific decoding mechanism and, so far, offer no known polynomial-time recovery protocol consistent with local modular evolution (see also Akers–Faulkner–Lin–Rath [

1]).

6.2. Novel Trichotomy: Retrieval Horizon

≠ Entanglement Wedge

≠ Event Horizon

A central implication is a three-way split among operational boundaries:

The retrieval horizon depends on the observer-specific profile and modular-wedge coherence; the entanglement wedge reflects the boosted reconstructability under the observer-modified RT prescription; and the event horizon tracks global causal boundaries irrespective of retrievability. These diverge when access, not existence, defines entropy.

These boundaries generally differ. The retrieval horizon depends on

and

. Even when the entanglement wedge and event horizon coincide, frame-specific recovery diverges; information exists, but its retrievability is bounded by the observer’s wedge alignment. In Kerr spacetime the relevant modular generator is the horizon-adapted Killing vector

[

13]. The observer-modified retrieval factor is therefore

evaluated near

to avoid divergences at the horizon. The Paley–Wiener bound applies within the subregion where

remains timelike,

, excluding the ergosphere but including all stationary observer world-lines with

; retrieval-wedge structure and the tanh onset are thus preserved.

6.3. Implications for Evaporating Black Holes

Standard Page-curve models treat evaporation with a global entropy turnover at the Page time. By contrast, the retrieval law (

5) yields continuous, frame-indexed trajectories:

Stationary observers retrieve information slowly, with .

Freely falling observers access interior correlations after horizon crossing, accelerating convergence.

Accelerating observers show Unruh-induced interference visible in decay modulation.

In every case, ; Page-like saturation thus originates in modular-wedge closure rather than ensemble averaging.

6.4. Experimental Implications and Roadmap

Analog-gravity platforms such as Bose–Einstein condensates can emulate the stationary, free-fall, and accelerating trajectories analyzed here. Detection likelihoods and experimental signal extraction are outside the scope of this theory paper; the discussion below is restricted to theoretical parameter estimates.

6.4.1. Timescale Bridge

Using natural units with

and

, proper time

translates to laboratory time as

so a

retrieval interval for an

acoustic analog corresponds to

.

The model therefore predicts that the

correlation matrix will exhibit a tanh-modulated decay within

, comfortably above the

detector resolution reported in Ref. [

31]. Full

trajectories, raw CSV files, and plotting scripts are archived at Figshare. For horizon velocities

and healing lengths

, the predicted retrieval window lies well inside current measurement sensitivity.

6.4.2. Operational Falsifiability Checklist

If the envelope is absent, the modular-access postulate fails.

If the envelope is present but the fitted is misaligned with theory, the retrieval law is incomplete.

If the extracted does not vary by observer class as predicted, observer specificity is invalidated.

Table 3.

Operational comparison for an observer at : ODER versus replica-wormhole/island frameworks.

Table 3.

Operational comparison for an observer at : ODER versus replica-wormhole/island frameworks.

| Feature |

ODER (This Work) |

Replica / Islands |

| Causal retrieval |

Proper-time delivery via modular flow |

Post-hoc entropy stabilization |

| Decoding protocol |

Polynomial MERA reconstruction |

No known decoder |

| Empirical observable |

in BECs |

None defined |

| Computational cost |

|

(H–P) |

Observation of these signatures, or their systematic absence, offers a decisive test of observer-dependent modular flow.

7. Limitations and Scope

Although the framework is tractable and experimentally accessible, several assumptions restrict its generality and point to clear directions for refinement.

7.1. No Back-Reaction Effects Modeled

All retrieval dynamics in this paper assume a fixed background metric. Setting in Eq. (5) recovers the standard semiclassical Einstein equation, showing that back-reaction is a controlled extension. If , feedback can shift the retrieval horizon by an amount of order ; a first-order scaling estimate shows that the modular-retrieval stress–energy remains of the Hawking flux for the simulations considered here (see Appendix C), so the induced change in is negligible for all observer classes studied.

7.1.1. Back-Reaction Bound

For a Schwarzschild black hole of mass

M, the retrieval flux scales as

so the fractional geometric response obeys

Hence modular retrieval produces a negligibly small metric shift over the entire parameter range considered, justifying the fixed-background treatment adopted in this work.

Outlook. Preliminary work is underway on a retrieval–gravity coupling model in which sources dynamical metric response. In spherical symmetry this defines a time-dependent system , with retrieval flux modulating curvature via causal saturation. The present paper isolates the fixed-background case; gravitational coupling will be addressed in a forthcoming companion analysis.

7.1.2. Semiclassical Modular-Flow Assumption

Throughout, we employ finite-split regularizations of Type III

1 algebras (see [

12,

16]) so that the restricted modular Hamiltonians are bounded on detector scales. Extending the retrieval law to Kerr (Appendix D), de Sitter, or other multi-horizon geometries will require the relative-Tomita framework and, in cosmological cases, crossed-product or edge-mode algebras [

14,

16].

7.2. Analog-System Resolution

Current Bose–Einstein–condensate platforms achieve timing precision of

–10 ms, demonstrated, for example, in

measurements by Steinhauer [

31], giving at least a five-fold margin for resolving the predicted 10–100 ms retrieval window. Detector fidelity should be benchmarked with baseline

runs before interpretation.

7.3. Exclusion of Exotic Topologies

The model omits replica wormholes, islands, and other “speculative” bulk geometries, preserving observer-bounded emergence coherence and keeping all predictions directly testable.

7.4. Potential Extension to Superposed Geometries

Future work could couple the retrieval law to geometries in quantum superposition, probing whether modular coherence bridges fluctuating horizons and informing quantum-cosmology scenarios.

7.5. No Global Unitarity Guarantee

Equation (

5) ensures unitarity only inside each observer’s causal wedge; persistent modular disagreements across overlapping diamonds are a feature, not a flaw, of wedge-indexed retrieval.

7.6. Retrieval-Horizon Scope

The framework guarantees saturation of only within the modular-flow domain visible to a given observer. Complete recovery beyond lies outside its present mandate.

This work defines testable envelopes, but does not model full detector noise or receiver operating characteristic (ROC) sensitivity curves.

8. Conclusion and Next Steps

We introduced a relativistic, observer-dependent framework for black-hole entropy retrieval that reconciles quantum mechanics with general relativity without invoking non-unitary dynamics or speculative topologies. By anchoring information recovery to proper time and causal access, the model replaces Page-curve bookkeeping with a continuous, falsifiable description of entropy flow. All theoretical derivations and simulation protocols are fully specified in the manuscript to ensure standalone reproducibility.

The retrieval law is not heuristic; it follows from first principles via the Tomita–Takesaki structure of modular spectra (Appendix A, Eq. A10). Entropy access arises from bounded modular flow that links spectral smoothing, redshift factors, and observer-specific algebras. Retrieval becomes a physically motivated process, not an epistemic relabel.

Concrete predictions follow. Observer classes exhibit distinct retrieval rates and envelopes, all testable with current analog-gravity technology. Failure to observe these signatures in bounded-access experiments would falsify the assumption of observer-modular accessibility, without impugning modular flow itself.

8.1. Roadmap: Theory, Simulation, Experiment

8.1.1. Theory

Semiclassical back-reaction. Couple entropy flow to metric response, extending Eq. (

5) into a dynamical observer–spacetime retrieval equation.

Intersecting horizons. Analyze overlapping yet non-identical causal diamonds to pinpoint conditions where retrieval coherence fails, refining the retrieval-horizon concept.

Quantum-superposed geometries. Probe retrieval when the background metric is in superposition, testing horizon blending and modular coherence.

8.1.2. Simulation

High-bond-dimension MERA. Benchmark convergence at and quantify finite-entanglement effects on fidelity.

Error-budget propagation. Integrate detector-noise kernels into synthetic data to produce ROC-style sensitivity curves.

8.1.3. Experiment

Trajectory-differentiated detectors. Deploy stationary, co-moving, and accelerating probes in BEC waterfalls; target the retrieval window with timing resolution.

Cross-platform validation. Replicate envelopes in photonic-crystal and superconducting-circuit analogs to assess universality across dispersion profiles.

These coordinated steps will sharpen the theory and support empirical validation. The analog-gravity community is well positioned to adjudicate the framework; forthcoming data will determine whether modular-access entropy flow may provide a testable, observer-specific alternative to global unitarity and shift the retrieval question from metaphysics to measurement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Simulation design, Visualization, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review & editing, Evlondo Cooper. The author has read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Simulation data (entropy–retrieval vectors and matrices), all plotting scripts, and full simulation logs are available to reviewers and qualified researchers upon request. A curated version of the Figshare record will be made publicly available upon peer-reviewed publication. An identical copy will be mirrored on GitHub.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Appendix A. First-Principles Derivation of the Observer-Dependent Retrieval Equation

Theorem A 1 (Observer-Retrieval Law).

Assumptions (A1–A4). A1: a globally hyperbolic background spacetime. A2: a faithful global state on the net . A3: an observer world-line with proper-time wedge . A4: a modular spectrum bounded below.

Conclusion. The unique function that (i) satisfies , (ii) is strictly increasing, (iii) has , and (iv) is generated by the modular automorphism group of obeys The solution is unique up to an overall scale in fixed by redshift factors and the gradient of the modular spectrum. □

|

Appendix A.1. Motivation: Bounded Algebras and Observer-Dependent Entropy

Algebraic quantum field theory (AQFT) describes quantum fields via nets of von Neumann algebras assigned to spacetime regions O. A global state on encodes all degrees of freedom in the domain of dependence of an observer’s world-line . At proper time the observer accesses only . The von Neumann-entropy difference between these algebras is the retrievable entropy deficit.

(Detector-scale split inclusions regularize the Type III1 spectrum; the Paley–Wiener bound relies only on analytic order, so the tanh-onset proof remains valid as . See discussion in the Introduction.)

Appendix A.1.1. Finite–Split regularization

Because

is Type III

1, its modular Hamiltonian is unbounded. For any realistic detector, however, one works inside a

split inclusion , where the intermediate factor

is Type I and the split distance is fixed by detector resolution. Longo’s split property guarantees such an

exists [

16]; explicit constructions for free fields appear in [

12]. Projecting

onto

smooths the modular spectrum above the detector cutoff

, giving

Because the Paley–Wiener bound depends only on the analytic order of , its form—and hence the tanh onset—remains unchanged as , so the derivation does not rely on any particular cutoff. Consequently, the Paley–Wiener bound used below is satisfied. In the limit one recovers the full Type III1 algebra; the retrieval law thus functions as an effective description valid on detector scales.

Appendix A.2. Entropic Retrieval Inside a Causal Diamond

In simulations (Appendix C) this causal-diamond growth is implemented by masking qubit indices along the chosen trajectory.

Combining a spectral-smoothing factor

with a frame-dependent growth factor

yields

Appendix A.2.1. Bounding Sketch

Monotonicity, a bounded modular spectrum, and

smoothness force the Laplace–Fourier transform of

to satisfy a Paley–Wiener–type bound. The only onset functions saturating this bound while obeying (i)–(iii) are asymptotically affine reparameterizations of

; see D’Antoni–Longo [

16] for a rigorous treatment of modular-spectrum constraints.

Lemma A1 (Uniqueness of the tanh onset).

Let satisfy assumptions(i)

–(iii)

of Theorem 1 and suppose its Laplace–Fourier transform is analytic for with the Paley–Wiener bound . Then the unique monotone onset compatible with this bound is, up to an affine reparameterization,

Proof (Proof sketch). Apply Thm. 3.2 of D’Antoni–Longo [

16] (bounded modular Hamiltonian ⇒ exponential type

) and combine with the monotone-convolution theorem; any sigmoid other than tanh violates the bound. □

The prefactor comes from bounded-spectrum regularization of the restricted modular Hamiltonian; no ensemble averaging is involved, and as .

Appendix A.3. The Role of γ(τ): Modular Spectrum and Redshift

The explicit normalization values used in the simulations are listed in

Table A1.

Table A1.

Observer-class retrieval parameters used in simulations for fig:gammaprofiles,fig:entropyretrievalcurves. is decomposed into a normalization constant and a trajectory-dependent profile. All times are in geometric units ().

Table A1.

Observer-class retrieval parameters used in simulations for fig:gammaprofiles,fig:entropyretrievalcurves. is decomposed into a normalization constant and a trajectory-dependent profile. All times are in geometric units ().

| Observer Class |

Prefactor |

|

|

|

| Stationary () |

|

|

|

— (no 90% retrieval) |

| Freely falling |

|

|

|

|

| Accelerating () |

|

|

|

|

Appendix A.4. Observer-Bounded Modular Automorphisms and the tanh Factor

Global modular flow generated by restricts to on , producing a smoothly expanding accessible spectrum. Finite detector resolution selects the onset, completing the derivation of Theorem A1.

Appendix A.5. Related Work

Bounded-algebra approaches using crossed products and edge modes [

14,

36] parallel the observer restriction adopted here. The resulting smooth entropy growth resembles ETH behavior [

32], though no ETH assumption is made.

Appendix A.6. Strengthened Toy Model

A simplified 1D spin chain with 40 sites and qubit Hilbert-space dimension qualitatively reproduces the tanh saturation behavior in under discrete time steps of . This model complements the MERA-based simulations but is not used in the main figures. Simulation code will be released in a supplementary repository or provided upon request.

Appendix A.7. Philosophical Implications

The retrieval law supports relational views in which entropy values depend on an observer’s accessible algebra. Disagreement between observers signals frame misalignment, not loss.

Appendix A.8. Derivation of τ Page from Spectral Gaps

Let be the smallest non-zero eigenvalue of . Then . For a Schwarzschild black hole of mass M, ; in lattice analogs it scales with correlation length . Because is wedge dependent, is observer specific; no universal value applies across distinct wedges.

Appendix A.9. Spectral Convergence and Uniqueness of the Retrieval Law

|

Theorem A.1 (Spectral–convergence constraint). Let the split-regularized modular Hamiltonian satisfy on the observer net . Let be a , strictly increasing, entire function with Then, up to an affine reparametrization of , the unique solution is Hence the retrieval law in Eq. (5) is the only smooth, spectrum-compatible onset allowed by bounded modular flow.□ |

Appendix A.9.1. Proof Sketch

By the Paley–Wiener theorem, any entire function whose Fourier transform is supported in is of exponential type . Among monotone sigmoids that converge to 1, is the unique minimal-type solution; linear, exponential, or oscillatory profiles either exceed the type bound or violate monotonicity. Therefore bounded-spectrum modular flow fixes the hyperbolic-tangent onset.

Appendix A.9.2. Corollary A.2 (Modular Convergence Class M 1 (Λ))

Define as the set of retrieval functions obeying the hypotheses of Theorem A.1. Then is the unique minimal element of ; any alternative retrieval curve must abandon at least one of bounded spectrum, monotonicity, or Paley–Wiener analyticity.

Appendix A.9.3. Remark

The theorem elevates the hyperbolic-tangent onset from a motivated ansatz to a spectral necessity. Competing exponential, linear, or damped profiles violate modular causality or observer-bounded access and are excluded from .

Appendix B. Extended Holographic Formulation

Appendix B.1. Observer-Dependent Minimal Surfaces

|

Definition A1 (Observer-RT Surface). For a boundary subregion A and an observer–frame boost , the observer-dependent holographic entanglement entropy is where is the codimension-2 minimal surface in the bulk geometry boosted by , and converts boundary coordinate time to the observer’s proper time so that only modes inside the causal diamond contribute to retrievable entropy. In the limit and , Eq. () reduces to the standard Ryu–Takayanagi formula.

|

The redshift factor is operational, not gauge: it removes bulk degrees of freedom that cannot be accessed within the observer’s proper-time flow and is fixed by the local lapse function in ADM decomposition.

Appendix B.2. Modular Wedge Alignment and Retrieval Horizons

Let

be the entanglement wedge reconstructed from boundary data in the frame

. Define the

retrieval horizon

where

is the Tomita–Takesaki flow for the boosted boundary state

and

is the

observer-specific Page time (Appendix A.8). Retrieval saturates when

stabilizes; its boundary

marks the modular limit of decodable information.

Appendix B.2.1. Wedge Disagreement

If observers are related by boosts

and

,

signaling that global entanglement reconstruction fails across frames and defining distinct retrieval horizons (see

Section 6.2).

Appendix B.3. Connection to HRT and Quantum Error-Correcting Codes

When

follows the boundary time slicing, Eq. () reduces to the Hubeny–Rangamani–Takayanagi (HRT) proposal for dynamical spacetimes. In holographic quantum-error-correcting codes (HaPPY, random-tensor MERA [

27]) the boost permutes bulk indices, altering which logical qubits are correctable from a fixed boundary patch. Our 48-qubit simulations (Appendix C) implement this by boosting boundary tensors before greedy decoding; minimal-surface areas differ by up to one MERA layer for bond dimension

, matching Eq. ().

Appendix B.4. Contrast with Replica Wormholes and Island Formulae

Replica-wormhole and island prescriptions reproduce the Page curve by adding Euclidean saddles. Equation () instead attributes late-time entropy saturation to bounded modular flow governed by ; no replica symmetry breaking or bulk topology change is required. Trans-horizon modes remain inaccessible until .

Appendix B.5. Outlook

- (1)

Cosmological horizons. Extend Eq. () to de Sitter and FRW spacetimes, where competing boosts generate multiple retrieval horizons acting as dynamical causal cutoffs.

- (2)

Back-reaction coupling. Couple the boost-dependent surface to semiclassical Einstein equations, allowing to evolve as information is extracted.

- (3)

Higher-bond networks. Test observer-dependent decoding in larger-bond MERA networks to quantify how tensor geometry sets redshift factors and retrieval latency.

Appendix C. Simulation Methods and Data Analysis

Appendix C.1. Simulation Setup

The tensor-network architecture follows Ref. [

27], with interchangeable layouts for matrix-product states (MPS) and multiscale entanglement renormalization ansatz (MERA). All figures in the main text use a 48-qubit MERA network with bond dimension

; a

variant was run to confirm retrieval-profile robustness (see C.4). A reproducible MPS implementation (v0.9) is included in a private repository that will be shared with reviewers and made publicly available upon publication.

Hardware envelope. All simulations were executed on a standard desktop computer with an Intel Core i7-9700 CPU (3.0 GHz, 8 threads) and 16 GB RAM, running a 64-bit operating system; no GPU acceleration was required.

System architecture: Forty-eight qubits discretize the bulk; bond edges encode holographic connectivity and entanglement structure.

Initial state: The network is prepared in a highly entangled pure state (vacuum analog). Unitary time evolution preserves long-range correlations.

Boundary conditions: Boundary tensors act as detectors or frame constraints, modified to emulate each observer class and to anchor the modular wedge.

Appendix C.2. Implementation of Observer-Dependent Channels

Observer channels are realized by adjusting geometry and algebraic access of the wedge:

Reconstruction regions: Stationary observers remain confined to fixed outer layers; freely falling and accelerating observers receive time-evolving wedges modeling modular growth or acceleration-induced interference.

Lorentz-boost encodings: Frame-dependent Lorentz transforms are applied to boundary tensors, altering reconstruction geometry and modular flow.

Channel variation: Systematic wedge realignment reproduces stationary, freely falling, and accelerating retrieval profiles, mapping directly onto the modular-access structures of Sec.

Section 3.

Appendix C.3. Data Analysis and Observable Extraction

Two observables test the retrieval law (

5):

Entanglement entropy. Reduced density matrices for each accessible wedge are computed at successive time steps; the resulting von Neumann entropies trace Page-like curves with class-specific saturation behavior.

Second-order correlation function. is extracted from simulated detector responses. An exponential baseline is fitted, and tanh-modulated deviations are isolated. For accelerating observers this interference is a distinctive signature unattainable in globally averaged models.

Parameter estimation. Each observer class is sampled at 100 uniform time points across a 500 ms retrieval window; non-linear least-squares fits yield and (10–100 ms) with 95% confidence intervals.

Bootstrap procedure. Confidence bands are generated via 200 resampled

traces per observer class, using a fixed proper-time grid and additive spectral noise, identical to the method described in Sec.

Section 4.1.

Following holographic–tensor-network conventions, the bond dimension scales roughly as , where is the Planck length; thus increasing D approximates deeper AdS geometries and yields finer-grained modular wedges.

Appendix C.4. Discussion and Validation

Differential Page curves. Observer-specific entropy trajectories validate the time-adaptive retrieval law (

5).

Observer-modified RT surfaces. Boundary reconstructions depend on modular-wedge alignment, confirming Eq. ().

interference. Accelerating observers exhibit the tanh-modulated pattern predicted by Eq. (

8); masking

collapses the pattern to a symmetric exponential.

Bond-dimension robustness. Doubling the bond dimension to changes the entanglement-entropy plateau by less than 1%, confirming numerical stability of the modular-saturation profile.

Scaling note. Future work will employ higher-bond MERA networks to probe finer-grained wedge reconstructions beyond the present 48-qubit limit.

Appendix D. Kerr Extension of the Retrieval Law

Modular flow in Kerr spacetime is generated by the horizon–adapted Killing vector

where

is the angular velocity of the outer horizon. For an observer following a stationary world-line outside the ergosphere, we define the frame-corrected retrieval factor

evaluated on a timelike surface at

with

the outer-horizon radius and

a small near-horizon regulator. Although

fails to commute with

, the modular spectrum in the

-timelike domain,

remains analytic and spectrally bounded, (see Castro

et al. [

13]), for explicit modular generators in Kerr, so the Paley–Wiener conditions that enforce the tanh retrieval onset are preserved.

Superradiant amplification widens the onset profile but does not alter its functional form. To leading order we obtain

where

is the Schwarzschild onset width and

encodes the net superradiant gain. All stationary observers satisfying the timelike condition above therefore experience the same modular-retrieval law as in the static case, up to this calculable broadening.

A complete perturbative derivation, covering the full Kerr modular flow, the impact of non-commuting angular modes, and laboratory implications for rotating analogue black holes, will be explored in future work.

References

- Akers, C.; Faulkner, T.; Lin, S.; Rath, P. The Page Curve for Reflected Entropy. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 06, 089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black Holes: Complementarity or Firewalls? J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Engelhardt, N.; Marolf, D.; Maxfield, H. The Entropy of Bulk Quantum Fields and the Entanglement Wedge of an Evaporating Black Hole. J. High Energy Phys. 2019, 063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Hartman, T.; Maldacena, J.; Shaghoulian, E.; Tajdini, A. The Entropy of Hawking Radiation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, H. Relative Entropy of States of von Neumann Algebras. Publ. Res. Inst. Math. Sci. 1976, 11, 809–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astesiano, D.; Gautason, F. F. Supersymmetric Wormholes in String Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 161601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R.; Casini, H.; Fisher, Z.; Maldacena, J. Proof of a Quantum Bousso Bound. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 044002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratteli, O.; Robinson, D.W. Operator Algebras and Quantum Statistical Mechanics I: C*- and W*-Algebras, Symmetry Groups, Decomposition of States, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, R.; Fredenhagen, K.; Verch, R. The Generally Covariant Locality Principle—A New Paradigm for Local Quantum Field Theory. Commun. Math. Phys. 2003, 237, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, P.; Cano, P.A.; Hennigar, R.A. Regular Black Holes from Pure Gravity. Phys. Lett. B 2020, 861, 139260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, H.; Huerta, M.; Myers, R.C. Towards a Derivation of Holographic Entanglement Entropy. J. High Energy Phys. 2011, 036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, H.; Huerta, M.; Rosabal, J. A. Remarks on Entanglement Entropy for Gauge Fields. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 085012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Maloney, A.; Strominger, A. Hidden Conformal Symmetry of the Kerr Black Hole. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 82, 024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, V.; Longo, R.; Penington, G.; Witten, E. An Algebra of Observables for de Sitter Space. J. High Energy Phys. 2023, 082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispino, L.C.B.; Higuchi, A.; Matsas, G.E.A. The Unruh Effect and Its Applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 787–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antoni, C.; Longo, R. Interpolation by Type I Factors and the Flip Automorphism. J. Funct. Anal. 2001, 182, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, W.; Michel, B.; Wall, A. C. Electromagnetic Duality and Entanglement Anomalies. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 045008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, T.; Li, M. Asymptotically Isometric Codes for Holography. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.12439 [hep-th], [hep–th]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, P.; Preskill, J. Black Holes as Mirrors: Quantum Information in Random Subsystems. J. High Energy Phys. 2007, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafferis, D.L.; Lewkowycz, A.; Maldacena, J.; Suh, S.J. Relative Entropy Equals Bulk Relative Entropy. J. High Energy Phys. 2016, 004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafferis, D.L.; Bluvstein, D.; Himmelspach, M.; et al. Traversable Wormhole Dynamics on a Quantum Processor. Nature 2022, 612, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Vardhan, S. Entanglement Entropies of Equilibrated Pure States in Quantum Many-Body Systems and Gravity. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 010344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, R. Lectures on Conformal Nets—Part I. Unpublished lecture notes, 2008. https://www.mat.uniroma2.it/~longo/Lecture-Notes_files/LN-Part1.pdf.

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool Horizons for Entangled Black Holes. Fortschr. Phys. 2013, 61, 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de Nova, J. R.; Golubkov, K.; Kolobov, V. I.; Steinhauer, J. Observation of Thermal Hawking Radiation and Its Temperature in an Analogue Black Hole. Nature 2019, 569, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.N. Average Entropy of a Subsystem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastawski, F.; Yoshida, B.; Harlow, D.; Preskill, J. Holographic Quantum Error-Correcting Codes: Toy Models for the Bulk/Boundary Correspondence. J. High Energy Phys. 2015, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penington, G. Entanglement Wedge Reconstruction and the Information Paradox. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penington, G.; Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D.; Yang, Z. Replica Wormholes and the Black Hole Interior. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 084007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A. Traversable Wormholes, Regular Black Holes, and Black-Bounces. Master’s Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, J. Observation of Quantum Hawking Radiation and Its Entanglement in an Analogue Black Hole. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srednicki, M. Chaos and Quantum Thermalization. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 50, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The World as a Hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesaki, M. Theory of Operator Algebras I; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, E. APS Medal for Exceptional Achievement in Research: Entanglement Properties of Quantum Field Theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Gravity and the Crossed Product. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Sub-exponential relative to decoding complexity, e.g., circuit depth or modular-spectrum reconstruction. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).