Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

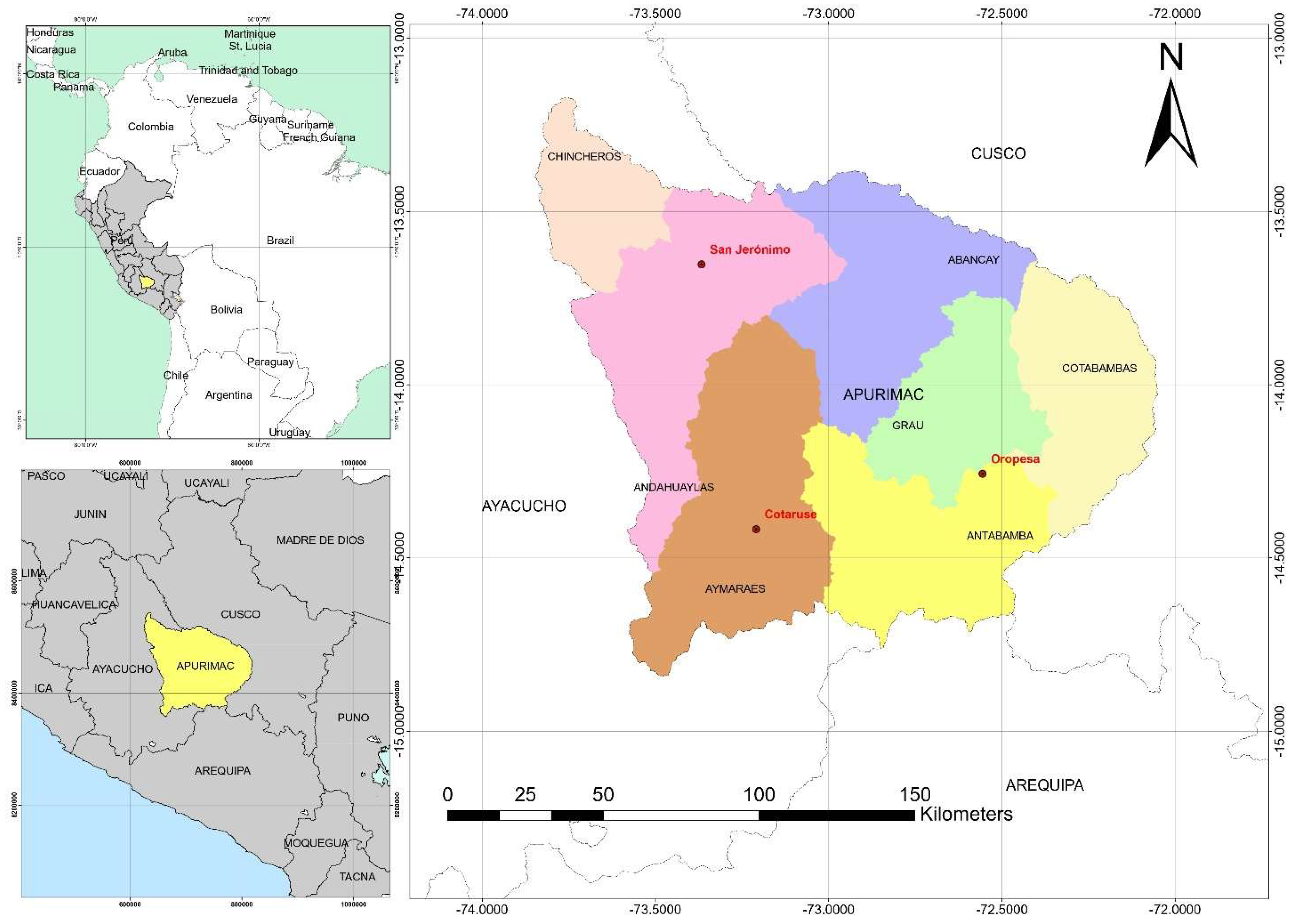

2.1. Location

2.2. Design

2.3. Population and Sample

2.4. Sample Collection and Serological Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MIDAGRI [Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego]. Anuario Estadístico de Producción Ganadera y Avícola 2023. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/6837096/2730346-anuario-produccion-ganadera-y-avicola-2023.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Arauco, F.; Rosadio, R. Seroprevalence of Bovine Viral Diarrhea and Neosporosis in Cows in the Region of Junín, Peru. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2015, 26(3), 543-547. [CrossRef]

- De Vries, A. Economic value of pregnancy in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89(10): 3876-3885. [CrossRef]

- Brownlie, J.; Hooper, L.B.; Thompson, I.; Collins, M.E. Maternal recognition of foetal infection with bovine virus diarrhea virus – the bovine pestivirus. Clin. Diagn. Virol. 1998, 10: 141150. [CrossRef]

- López del Aguila, W.Y. Prevalence of Bovine Brucellosis in the Livestock Basin of Alto Imaza, Amazon region, Peru. Revista Científica UNTRM: Ciencias Naturales e Ingeniería 2021, 4(2), 15-19. [CrossRef]

- Reyes Rossi, A.E.; Gordillo, F.E.C.; Beltrán, H.A.S. Presence of bovine brucellosis in the province of Oxapampa, department of Cerro de Pasco, Peru. Biotempo 2017, 14(2), 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.F.N.; Colorado, N.R.; Araque, J.M. Prevalence of bovine viral diarrhea, bovine neosporosis, enzootic bovine leukosis and bovine paratuberculosis in dual-purpose cows in conditions of the Colombian tropics. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2022, 33(2), e20694. [CrossRef]

- Incil, E.B. Seroprevalencia y factores de riesgo de infección por el virus de lengua azul en bovinos del Perú. Master Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, 2023.

- Gong, Q.L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X.Y.; Li, D.L.; Zhao, B.; Ge, G.Y.; Zong, Y.; Li, J.M.; Leng, X.; Shi, K.; Liu, F., Du, R. Seroprevalence and risk factors of the bluetongue virus in cattle in China from 1988 to 2019: a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 550381. [CrossRef]

- Valdez, E.; Pacheco, I.; Vergara, W.; Pinto, J.; Fernández, F.; Guzmán, F.; Rivera, H. Antibody detection against bovine viral diarrhea virus in cattle of the province of Anta, Cusco, Peru. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2018, 29(4), 1500-1507. [CrossRef]

- León, S.E.; Barrantes, C.; Feijoo, S.; Huamán, E.; Ampuero, G.; Canto, F.; Quispe-Ccasa, H.A. Seroprevalence of reproductive and infectious diseases in cattle: the case of Madre de Dios in the Peruvian southeastern tropics. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 85(4), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- SENASA [Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria]. 2011. Caracterización de la Diarrea Viral Bovina, Neospororis Bovina, y Rinotraqueitis Infecciosa Bovina en el Perú. Informe Final. Available online: https://www.senasa.gob.pe/senasa/descargasarchivos/jer/BOVINOS/Caracterizacion%20DVB%20NB%20y%20RIB.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Vilchez-Tineo, C.; Morales-Cauti, S. (2022). Seroprevalencia de anticuerpos contra el virus de la Rinotraqueitis Infecciosa Bovina en ganaderías de crianza extensiva en tres distritos de Ayacucho, Perú. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú, 33(2), e22577. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.E.; Pérez, C.L. Neospora caninum in the Andean Community of Nations. Arch. Latinoam. Prod. Anim. 2024. 32(Supl.1), 87-100. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, G.H. Causas frecuentes de aborto bovino. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2001, 12(2), 117-122.

- Cárdenas, C.; Rivera, H.; Araínga, M.; Ramírez, M.; De Paz, J. Prevalence of bovine viral diarrhea virus and persistently infected cattle in the province of Espinar, Cusco. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2011, 22(3), 261-267.

- Gädickea, P.; Monti, G. Epidemiological and analytical aspects of bovine abortion syndrome. Arch. Med. Vet. 2008, 40(3), 223-234. [CrossRef]

- SENAMHI [Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología]. Estación Meteorológica Convencional Aymaraes. Datos hidrometeorológicos a nivel nacional. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?&p=estaciones (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- INEI [Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria]. 2012. IV Censo Nacional Agropecuario (CENAGRO). Available online: https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/CenagroWeb/# (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Valdivia P.L.; Rivera, G.H. Seroprevalencia de Brucella sp. en bovinos criollos de crianza extensiva de la provincia de Parinacochas, Ayacucho. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2003, 14(2), 174-177.

- Elías, I.C.; Viola, M.N.; Russo, A.M.; Lozina, L.A.; Signorini, M.L. Situation and distribution of bovine brucellosis in the province of Formosa, Argentina. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2023, 34(6), e24958. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano Aguayo, M.D.; Pérez Ruano, M.; Rodríguez Villafuerte, X. Bovine brucellosisinthe manabí province, ecuador. Study of risk factors. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú. 2016, 27(3), 607-617. [CrossRef]

- SENASA. 2012. Caracterización de paratuberculosis bovina en el Perú. Available online: https://www.senasa.gob.pe/senasa/descargasarchivos/jer/BOVINOS/Informe%20SENASA%20PTBC.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Benavides, B.; Arteaga, A.V.; Montezuma, C.A. Epidemiological Study of Bovine Paratuberculosis in Dairy Herds in Southern Nariño, Colombia. Rev. Med. Vet. 2016, 31, 57-66.

- Jaramillo, S.; Montoya, M.A.; Uribe, J.S.; Ramírez, N.F.; Fernández-Silva, J.A. Seroprevalence of paratuberculosis (Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis) in a specialized dairy herd of the northern high plateau of Antioquia, Colombia. Veterinaria y Zootecnia 2017, 11(2), 24-33. [CrossRef]

- García, A.B., Shalloo, L. The economic impact and control of paratuberculosis in cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Fecteau, M.E. Paratuberculosis in cattle. Vet. Clin. Food Anim. 2017, 34(1), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Hasonova, L.; Pavlik, I. Economic impact of paratuberculosis in dairy cattle herds: a review. Vet. Med.-Czech. 2006, 51(5), 193-211. [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.; Rivera, G.H. (2000). Seroprevalencia del Virus de Leucosis Bovina en la Cuenca Lechera de Arequipa. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2000, 11(2), 144-148. [CrossRef]

- Frias, H.; Murga, N.; Rojas-Bravo, Y.; Portocarrero, S.; Torres, E. Seroprevalence of bovine leukosis in dairy stables of Chachapoyas and Pomacochas. Rev. Agrop. Sci. & Biotech. 2021, 1(3), 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, R.; Delgado, A.; Ruiz, L.; Ramos, O. Determination of the seroprevalence of bovine leukemia virus in a dairy farm of Lima, Peru. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2015, 26(1), 152-158. [CrossRef]

- Mionetto, M.; Rodríguez, A.F. Asociación entre leucosis bovina enzoótica y la respuesta inmune humoral natural contra enfermedades infecciosas de interés reproductivo. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de La República, Uruguay, 2018.

- Gutiérrez, S.E.; Lützelschwab, C.M.; Barrios, C.N.; Juliarena, M.A. Bovine Leukosis: an updated review. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2020, 31(3), e16913. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, P.C.; Ruggiero, V.J.; Hutchinson, H.C.; Droscha, C.J.; Norby, B.; Sporer, K.R.B.; Taxis, T.M. Current Developments in the Epidemiology and Control of Enzootic Bovine Leukosis as Caused by Bovine Leukemia Virus. Pathogens 2020, 9(12), 1058. [CrossRef]

- Tupayachi M. Seroprevalencia molecular de cepas emergentes del virus lengua azul en vacunos del distrito de Challabamba – Paucartambo – Cusco. Bachelor Thesis, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Peru. 2024.

- Ramos, H. Distribución espacial y seroprevalencia del virus Lengua Azul en bovinos de los departamentos de la selva del Perú. Bachelor Thesis, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Peru, 2023.

- Nogueira, A.C.; De Stefano, E.; Martins, M.S.N.; Okuda, L.H.; Lima, M.S.; Garcia, T.S.; Hellwig, O.H.; Lima, J.E.; Savini, G.; Pituco, E.M. Prevalence of Bluetongue virus serotype 4 in cattle in the State of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Vet. Ital. 2016, 52(3-4), 319-323. [CrossRef]

- Verdezoto, J.; Breard, E.; Viarouge, C.; Quenault, H.; Lucas, P.; Sailleau, C.; Zientara, S.; Augot, D.; Zapata, S. Novel serotype of bluetongue virus in South America 65 and first report of epizootic haemorrhagic disease virus in Ecuador. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65(1), 244-247. [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, N.J.; Mayo, C.E.; Daniels, P.W.; Savini, G.; Zientara, S.; Gibbs, E.P.J. Bluetongue. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2015, 34, 329-340. [CrossRef]

- Katsoulos, P.D.; Giadinis, N.D.; Chaintoutis, S.C.; Dovas, D.I.; Kiossis, E.; Tsousis, G.; Psychas, V.; Vlemmas, I.; Papadopoulos, T.; Papadopoulos, O.; Zientara, S.; Karatzias, H.; Boscos, C. Epidemiological characteristics and clinicopathological features of bluetongue in sheep and cattle, during the 2014 BTV serotype 4 incursion in Greece. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016, 48(3), 469-477. [CrossRef]

- Saminathan, M.; Singh, K.P.; Khorajiya, J.H.; Dinesh, M.; Vineetha, S.; Maity, M.; Rahman, A.F.; Misri, J.; Malik, Y.S.; Gupta, V.K.; Dhama, K. An updated review on bluetongue virus: epidemiology, pathobiology, and advances in diagnosis and control with special reference to India. Vet. Q. 2020, 40(1), 258-321. [CrossRef]

- Navarro Mamani, D.A.; Ramos Huere, H.; Vera Buendia, R.; Rojas, M.; Chunga, W.A.; Valdez Gutierrez, E.; Vergara Abarca, W.; Rivera Gerónimo, H.; Altamiranda-Saavedra, M. Would Climate Change Influence the Potential Distribution and Ecological Niche of Bluetongue Virus and Its Main Vector in Peru? Viruses 2023, 15, 892. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, L.l.S.; Rivera, G.H.; Pezo, C.D.; García, V.W. Detección de anticuerpos contra pestivirus en rumiantes de una comunidad campesina de la provincia de Canchis, Cuzco. Rev. Inv. Vet. Peru 2002, 13(1), 46-51.

- Cabello, R.K.; Quispe, Ch.R.; Rivera, G.H. Frecuencia de los virus parainfluenza-3, respiratorio sincitial y diarrea viral bovina en un rebaño mixto de una comunidad campesina de Cusco. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2006, 17(2), 167-172.

- Quispe, Q.R.; Ccama, S.A.; Rivera, G.H.; Araínga, R.M. Bovine viral diarrea virus in criollo cattle of the Province of Melgar, Puno. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2008, 19(2), 176-182.

- Huamán, G.J.; Rivera, G.H.; Araínga, R.M.; Gavidia, Ch.C.; Manchego, S.A. Bovine viral diarrhoea and persistently infected animals in dairy herds in Majes, Arequipa. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2007, 18 (2): 141-149.

- Herrera-Yunga, V.; Labada, J.; Castillo, F.; Torres, A.; Escudero-Sanchez, G.; Capa-Morocho, M.; Abad-Guaman, R. Prevalence of antibodies and risk factors to bovine viral diarrhea in non-vaccinated dairy cattle from Southern Ecuador. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2018, 21(1), 11-18. [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, K.; Sibhat, B.; Ayelet, G.; Skjerve, E.; Gebremedhin, E.Z.; Asmare, K. Seroprevalence and factors associated with bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) infection in dairy cattle in three milksheds in Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2018. 50, 1821-1827. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, A.I.E.; Alenius S. Principles for eradication of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) infections in cattle populations. Vet. Microbiol. 1999, 64, 197-222. [CrossRef]

- González-Bautista, E.D.D.; Bulla-Castañeda, D.M.; Lopez-Buitrago, H.A.; Díaz-Anaya, A.M.; Lancheros-Buitrago, D.J.; Garcia-Corredor, D.J.; Tobón, J.C.; Ortiz, D.; Pulido-Medellín, M.O. Seroprevalence of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) in cattle from Sotaquirá, Colombia. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2021, 14, 100202. [CrossRef]

- Gates, M.C.; Woolhouse, M.E.J.; Gunn, G.J.; Humphry, R.W. Relative associations of cattle movements, local spread and biosecurity with bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) seropositivity in beef and dairy herds. Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 112, 285-295. [CrossRef]

- Corro, A.; Escalona, J.; Mosquera, O.; Vargas, F. Risk factors associated with Bovine Viral Diarrohea seroprevalence in non-vaccinated cows and heifer in the Bolívar Municipality of Yaracuy state, Venezuela. Gaceta de Ciencias Veterinarias 2017, 22(1), 27-32.

- Bharti, V.; Giri, A.; Vivek, P.; Kalia, S. Health and productivity of dairy cattle in high altitude cold desert environment of Leh-Ladakh: A review. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 87, 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Begazo, C.; Portocarrero, H.; Dávila, R. Electrocardiographic Parameters in Holstein calves reared at High Altitude and at sea level. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2017, 28, 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.C.; Rincón, J.C.; Echeverry, J.C. Prevalence of some infectious diseases in cattle of the indigenous resguards in Cauca, Colombia 2017. Rev. U.D.C.A. Actual. Divulg. Cient. 2018, 21(2), 507-517. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.L.; Miranda, I.C.S.; Hein, H.E.; Neto, W.S.; Costa, E.F.; Marks, F.S.; Rodenbusch, C.R.; Canal, C.W.; Corbellini, L.G. Herd-level risk factors for bovine viral diarrhea virus infection in dairy herds from Southern Brazil. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 95(3), 901–907. [CrossRef]

- Sayers, R.G. Associations between exposure to bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) and milk production, reproductive performance, and mortality in Irish dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2017. 100(2), 1340-1352. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.L.; Motta-Delgado, P.A.; Herrera, W.; Polania, R.; Cháves, L.C. Prevalence of bovine infectious rhinotracheitis virus in Caquetá. Rev. Med. Vet. Zoot. 2020, 67(1), 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, G.H.; Benito, Z.A.; Ramos, C.O.; Manchego, S.A. Prevalencia de enfermedades de impacto reproductivo en bovinos de la estación experimental de trópico del centro de investigaciones IVITA. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2004, 15(2), 120-126.

- Ruiz-Sáenz, J.; Jaime, J.; Vera, V. Prevalencia serológica y aislamiento del Herpesvirus Bovi-no-1 (BHV-1) en hatos ganaderos de Antioquia y del Valle del Cauca. Rev. Colomb. Cienci Pecu. 2010, 23(3), 299-307.

- Zacarías, R.E.; Benito, Z.A.; Rivera, G.H. Seroprevalencia del virus de la rinotraqueitis infecciosa en bovinos criollos de Parinacochas, Ayacucho. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú, 2002, 13(2): 61-65.

- Boelaert, F.; Speybroeck, N.; Kruif, A.; Aerts, M.; Burzykowski, T.; Molenberghs, G.; Berkvens, D. Risk factors for bovine herpesvirus-1 seropositivity. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 69, 285-295. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.S.; Meshram, C.D.; Singh, N.K.; Saini, M.; Mishra, B.P.; Gupta, P.K. Development of a SYBR Green I based duplex real-time PCR for detection of bovine herpesvirus-1 in semen. J. Virol. Methods 2014, 208, 6-10. [CrossRef]

- Abad, J.; Ríos, A.; Rosete, J.; García, A.; Zarate, J. Prevalence of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and bovine viral diarrhea in females in three seasons in the downtown area of Veracruz. Nova Scientia 2016, 8, 213–227.

- Atocsa, J.; Chávez, A.; Casas, E.; Falcón, N. Seroprevalencia de Neospora caninum en bovinos lecheros criados al pastoreo en la provincia de Melgar, Puno. Rev Inv Vet Perú 2005, 16, 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Cevallos, A.F.; Morales-Cauti, S. Seroprevalence of antibodies against Neospora caninum in extensive cattle farming in three districts of Parinacochas, Ayacucho. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2021. 32(4), e20933. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, T.; Betancur, C.; Mestra, A.; González, M.; Reza, L.; Calonge, K. Serological study about neosporosis in cattle with reproductive disorders in Monteria, Córdoba, Colombia. Rev. MVZ Cordoba 2007, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Pulido Medellín, M.O.; Díaz Anaya, A.M.; Andrade Becerra, R.J. Association between reproductive variables and anti Neospora caninum antibodies in dairy cattle herds from a Colombian municipality. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2017, 8(2), 167-174. [CrossRef]

- Pulido Medellín, M.O.; Díaz Anaya, A.M.; García, D.J.; Andrade Becerra, R.J. Verifying presence of anti Neospora caninum antibodies in cows in Sugamuxi province, Colombia. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2013, 4(4), 501-506.

- Maldonado, J.E.; Pérez, C.L. Infectious diseases of cattle diagnosed between 2020 and 2022 in the southern highlands of Ecuador. Arch. Latinoam. Prod. Anim. 2022, 30(Supl.2), 63-65. [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.; Chávez, A.; Falcón, N.; Casas, E.; Puray, N. (2010). Prevalence of Neospora caninum in shepherd dogs of a livestock farm in the southern highlands of Peru. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú 2010, 21(1), 80-86.

- Serrano-Martínez, M.E.; Cisterna, C.A.B.; Romero, R.C.E.: Huacho, M.A.Q.; Bermabé, A.M.; Albornoz, L.A.L. Evaluation of abortions spontaneously induced by Neospora caninum and risk factors in dairy cattle from Lima, Peru. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019, 28(2), 215-220.

| Variable | BR | MAP | BHV | VDVB | BLV | BTV | NC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | |||||||

| San Jerónimo | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.79 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.79 (1) | 0 (0) | 10.32 (13) |

| Cotaruse | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21.62 (32) | 0.68 (1) | 1.35 (2) | 1.35 (2) | 4.05 (6) |

| Oropesa | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 37.93 (33) | 2.30 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6.90 (6) |

| p-value | - | - | <0.001 | 0.185 | 0.544 | 0.235 | 0.126 |

| Sector | |||||||

| Choccecancha | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Champaccocha | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.70 (1) | 0 (0) | 3.70 (1) | 0 (0) | 25.93 (7) |

| Ancatira | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14.29 (2) |

| Cupisa | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 23.08 (3) |

| Totoral | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6.67 (1) |

| Soytocco | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20.00 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pilluni | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Llaccsa | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 37.50 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12.5 (2) |

| San Miguel de Mestisas | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.00 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pallccapampa | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8.33 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Promesa | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27.27 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9.09 (1) | 9.09 (1) |

| Cotaruse | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 41.67 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ccosccoche - Pampamarca | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27.27 (3) | 0 (0) | 9.09 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Puerto Aparanga | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Panamericana | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14.29(1) | 0 (0) |

| Pamparica | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 50.00 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ancco - Pamapamarca | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 57.14 (4) | 0 (0) | 14.29 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pucursa | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9.09 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27.27 (3) |

| Huayllucuna | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33.33 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pumaturco | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100.00 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hmpalla | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25.00 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Totora | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 36.99 (27) | 1.37 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8.22 (6) |

| Cahautia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 42.86 (6) | 7.14 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| p-value | - | - | <0.001 | 0.922 | 0.123 | 0.010 | 0.005 |

| Total | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18.28 (66) | 0.83 (3) | 0.83 (3) | 0.55 (2) | 6.93 (25) |

| Seropositivity level | District | N | BHV | VDVB | BLV | BTV | NC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector-level seropositivity | San Jerónimo | 5 | 20.00 (1) | 0 (0) | 20.00 (1) | 0 (0) | 80.00 (4) |

| Oropesa | 2 | 100.00 (2) | 100.00 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 50.00 (1) | |

| Cotaruse | 16 | 75.00 (12) | 6.30 (1) | 12.50 (2) | 12.50 (2) | 18.80 (3) | |

| p-value | 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.04 | ||

| Total | 23 | 65.20 (15) | 13.00 (3) | 13.00 (3) | 8.70 (2) | 34.80 (8) | |

| Herd-level seropositivity | San Jerónimo | 24 | 2.00 (1) | 0 (0) | 2.00 (1) | 0 (0) | 21.60 (11) |

| Oropesa | 18 | 55.60 (10) | 11.10 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16.70 (3) | |

| Cotaruse | 51 | 62.50 (15) | 4.20 (1) | 8.30 (2) | 8.30 (2) | 16.70 (4) | |

| p-value | <0.01 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.84 | ||

| Total | 93 | 28.00 (26) | 3.20 (3) | 3.20 (3) | 2.20 (2) | 19.40 (18) |

| Variable | BHV | VDVB | BLV | BTV | NC |

| Age | |||||

| 2 years | 15.04 (17) | 1.77 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7.08 (8) |

| 3 years | 19.05 (20) | 0 (0) | 1.90 (2) | 0 (0) | 7.62 (8) |

| 4 years | 16.85 (15) | 1.12 (1) | 1.12 (1) | 0 (0) | 6.74 (6) |

| 5 years | 29.17 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8.33 (2) |

| 6 years | 19.05 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9.52 (2) | 4.76 (1) |

| 7 years | 33.33 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| p-value | 0.517 | 0.756 | 0.706 | <0.001 | 0.964 |

| Age group | |||||

| 2-3 years | 16.97 (37) | 0.92 (2) | 0.92 (2) | 0 (0) | 7.34 (16) |

| 4-5 years | 19.47 (22) | 0.88 (1) | 0.88 (1) | 0 (0) | 7.08 (8) |

| 6-7 years | 23.33 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6.67 (2) | 3.33 (1) |

| p-value | 0.648 | 0.871 | 0.871 | <0.001 | 0.718 |

| Phenotypic traits | |||||

| Creole | 17.24 (40) | 0 (0) | 0.43 (1) | 0.86 (2) | 8.62 (20) |

| Brown Swiss | 14.78 (17) | 2.61 (3) | 1.74 (2) | 0 (0) | 4.35 (5) |

| p-value | 0.561 | 0.013 | 0.215 | 0.318 | 0.147 |

| Seropositivity | District | |||||||||||

| Oropesa | Cotaruse | San Jerónimo | ||||||||||

| VDVB | NC | BLV | BTV | VDVB | NC | BLV | BTV | VDVB | NC | BLV | BTV | |

| BHV | 0.04 | 0.12 | . | . | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.06 | . | 0.03 | 0.01 | . |

| 0.73 | 0.27 | . | . | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.33 | 0.46 | . | 0.74 | 0.93 | . | |

| VDVB | 0.04 | . | . | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | . | . | . | |||

| 0.70 | . | . | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.91 | . | . | . | ||||

| NC | . | . | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | . | ||||||

| . | . | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.74 | . | |||||||

| BLV | . | 0.01 | . | |||||||||

| . | 0.87 | . | ||||||||||

| Coeficients | BHV | NC | |||||

| OR | IC 95% | p-value | OR | IC 95% | p-value | ||

| (Intercept) | 0.007 | 0.0004–0.04 | <0.01** | 0.167 | 0.08–0.33 | <0.01** | |

| San Jerónimo | Cotaruse | 35.109 | 7.33–630.75 | <0.01** | 0.333 | 0.11–0.88 | 0.033* |

| Oropesa | 70.764 | 14.11–1289.94 | <0.01** | 0.943 | 0.31–2.59 | 0.911 | |

| 2–3 years | 4–5 years | 1.581 | 0.80–3.09 | 0.181 | 0.808 | 0.31–1.94 | 0.644 |

| 6–7 años | 0.902 | 0.24–2.81 | 0.867 | 0.376 | 0.02–2.02 | 0.357 | |

| Creole | Brown Swiss | 0.693 | 0.33–1.39 | 0.313 | 0.384 | 0.12–1.02 | 0.074 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).