1. Introduction and Physical Motivation

Reconciling General Relativity (GR) with Quantum Mechanics (QM) is a cornerstone challenge in theoretical physics. String theory, distinguished by its ultraviolet finiteness and natural incorporation of gravity through extended objects like D-branes in ten dimensions [

12,

21], remains a leading framework. However, bridging its high-dimensional structure to a low-energy, four-dimensional description compatible with observations is non-trivial. Standard approaches, such as Calabi-Yau compactification with moduli stabilization via fluxes or non-perturbative effects [

13], succeed in principle but leave unresolved issues, including the cosmological constant, dark-matter phenomenology, and the emergence of semiclassical spacetime.

A geometric alternative. Two theoretical advancements motivate a novel approach. First, non-Hermitian but

-symmetric quantum theories can exhibit real spectra and consistent unitary evolution, broadening the scope of viable physical models [

1,

2]. Second, non-commutative geometry (NCG) redefines spacetime through a spectral triple, enabling matrix-valued metric components that encode additional degrees of freedom [

7,

8]. These suggest that structures typically confined to compact extra dimensions might manifest directly in the four observable dimensions, providing a geometric pathway to dark sectors.

Proposed model. We propose a

-symmetric quaternionic extension of the four-dimensional metric:

where

is the real FLRW metric, and

represents imaginary quaternionic deformations. The imaginary component is sourced by a rotational NS-NS

B-field:

inspired by T-duality and instanton effects in a D3-D7 brane system at a

orbifold singularity (

Section 3.2,

Appendix B.1, reasonable assumption). Here,

is the FLRW scale factor, and

is the string-scale flux parameter. The quaternionic factor reflects SU(2) gauge symmetry on D4-brane world-volumes [

25].

Phenomenological parameters. The model is governed by two key parameters:

, a dimensionless coupling defining

and

with

, unifying cosmological dark energy and galactic rotation-curve corrections (

Section 4, phenomenological introduction).

, the effective coupling after compactification, suppressed from

through large-volume, warping, and IR/UV effects, yielding a hierarchy

(

Section 3.3,

Appendix C).

Theoretical features. The model offers:

symmetry: Ensures real curvature scalars and observables despite the non-Hermitian metric (

Appendix A, strict derivation).

Stability: Scalar perturbations are ghost- and gradient-free; tensor-mode stability is under investigation (

Section 2.4).

Unified dark sectors: A single

reproduces the Planck-2018 dark-energy density (

) and fits 175 SPARC rotation curves with

, outperforming

CDM in ∼40% of cases with fewer parameters (

Section 4).

Exploratory scope. This work prioritizes phenomenological viability over a complete top-down derivation. The

B-field’s coordinate dependence, derived from instanton-induced displacements (e.g.,

,

Appendix B.1), is a reasonable assumption requiring validation in realistic Calabi-Yau compactifications. Similarly,

and the linear form of

are phenomenologically introduced, with spectral-action contributions being subdominant (

Appendix B.3). These assumptions are transparent and call for rigorous string-theoretic and numerical verification.

Structure of the paper. Section 2 formalizes the quaternionic metric and assesses its stability.

Section 3 elaborates string-theoretic and spectral geometry motivations, including T-duality and compactification effects.

Section 4 derives cosmological and galactic predictions, tested against Planck, DESI, and SPARC data.

Section 5 contrasts the model with NCG,

-symmetric gravity,

CDM, and MOND.

Section 6 summarizes findings and outlines future tests. Appendices provide details on

symmetry (A), string derivations (B), and compactification (C).

Outlook. A first-principles derivation of the B-field in concrete Calabi-Yau backgrounds, a spectral-action calculation of , and large-scale structure tests (e.g., CMB, BAO) are critical next steps. Upcoming surveys, such as Euclid and LSST, will probe the model’s unified dark-sector predictions, potentially establishing it as a compelling bridge between string-inspired quantum gravity and precision cosmology.

2. Quaternionic Spacetime: Theoretical Framework and Stability Analysis

We posit a four-dimensional spacetime with a

PT-symmetric, quaternionic metric

where

is the real FLRW metric and

captures imaginary quaternionic deformations. This structure arises from an SU(2) gauge symmetry on d-branes in Type IIB string theory and the SU(2) spin structure of spectral triples in non-commutative geometry (see

Section 3.2 and

Appendix B.3).

2.1. Rotational B-Field and Quaternionic Ansatz

A coordinate-dependent NS–NS

B-field of the form

with

, is mapped via T-duality and dimensional reduction from a quantised internal flux (

Section 3.2). The quaternionic unit sum

is enforced by SU(2) gauge-field commutators on coincident D4-branes,

, with

.

Phenomenological parameters. Compactification effects, e.g. warping and large internal volumes (

Section 3.3), suppress

to an effective

,

. Meanwhile, a single dimensionless coupling

with

,

, unifies dark- energy and galactic phenomenology (

Section 4).

2.2. Exact Inverse Metric

Because the imaginary part is not perturbatively small, we invert

exactly. The temporal and spatial blocks decouple:

Details appear in

Appendix A.

2.3. PT Symmetry and Real Curvature

Under PT,

and

, so the imaginary deformation is PT-odd while curvature scalars (Ricci scalar, etc.) are PT-even and therefore real (

Appendix A).

2.4. Linear Stability

Perturbing

and expanding the Einstein–Hilbert action to quadratic order yields a kinetic term

which is positive for

, ruling out ghosts. Spatial-gradient terms have the correct sign, eliminating gradient instabilities. Tensor-mode stability, especially in inner galactic regions, is under further study.

2.5. Limitations and Domain of Validity

While the quaternionic metric (

3–

5) provides a unified dark-sector framework, its top-down derivation is heuristic. Key open issues:

Despite these gaps, the model’s minimal parameter set and empirical success motivate further investigation.

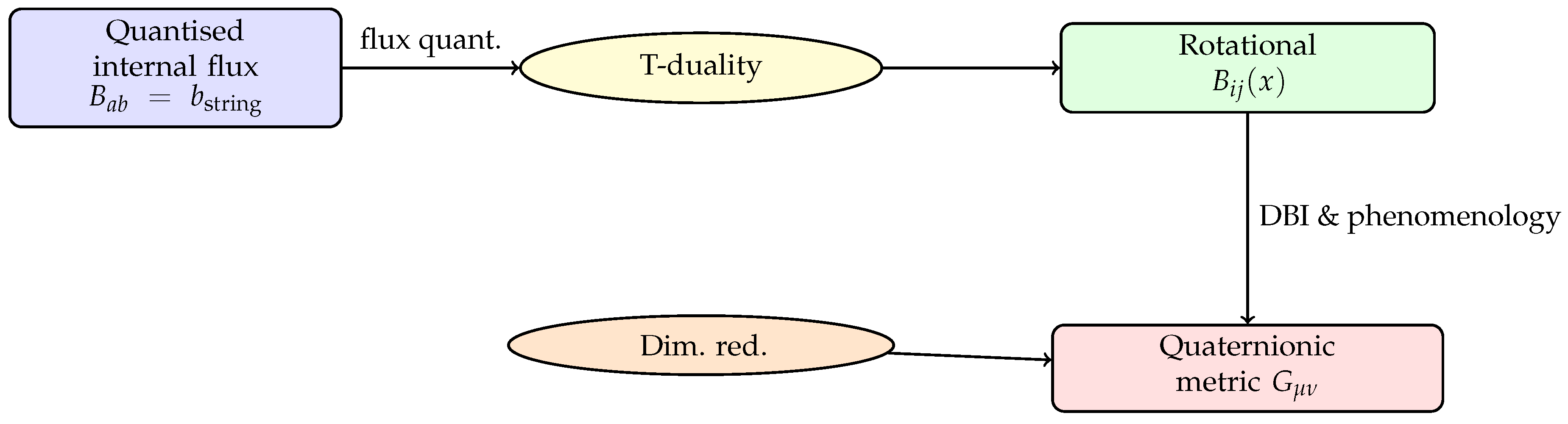

3. From DBI to a Quaternionic Metric: String-Theory Motivation and Spectral Insights

This section outlines the string-theoretic and spectral geometry motivations for the quaternionic metric (Eq. (

1)), through three complementary perspectives: (i) D3-brane dynamics via the Dirac-Born-Infeld (DBI) action, (ii) Buscher T-duality acting on quantized internal flux, and (iii) Connes’ spectral action in non-commutative geometry (NCG). A key result is the effective coupling:

where

provides the dimension

, and the dimensionless factor

encapsulates large-volume, warping, and IR/UV effects (

Section 3.3,

Appendix C). All expressions maintain dimensional consistency.

3.1. D3-brane Dynamics and the DBI Action

The bosonic sector of a probe D3-brane in type-IIB string theory is governed by the Dirac-Born-Infeld action [

21]:

with the world-volume gauge field

set to zero. We embed the brane in a flat FLRW background,

, with six internal dimensions compactified on a Calabi-Yau three-fold of volume

.

3.2. T-Duality and the Rotational B-Field

A quantized NS-NS flux threading a two-cycle

satisfies:

Applying Buscher T-duality along one leg of

[

4], combined with instanton effects from D3-D7 brane intersections, yields a coordinate-dependent

B-field in the non-compact directions (

Appendix B.1):

where the quaternionic factor

reflects SU(2) gauge symmetry on D4-brane world-volumes [

25]. This ansatz, motivated by instanton-induced displacements (e.g.,

), is a reasonable assumption requiring validation in realistic Calabi-Yau compactifications.

3.3. Compactification and the Hierarchy

Galactic rotation curves require a linear coupling

, 86 orders of magnitude below

. We define:

with:

Large-volume factor: , for an internal scale .

Warp factor: , with warp factor in a moderately warped throat.

IR/UV loop factor:

, with

, reflecting phenomenological loop corrections (

Appendix C).

Since

, we compute:

yielding

, consistent with phenomenological requirements.

3.4. From the DBI Determinant to a Linear Metric Correction

For the FLRW metric

and the rotational

B-field (Eq. (

11)), the DBI determinant expands as:

To reproduce flat rotation curves, we assume a linear quaternionic metric correction:

motivated by the linear scaling of

in the DBI action. This form may arise from open-string condensation linearizing the

contribution [

23], though it remains a phenomenological assumption pending rigorous string field theory derivation. The temporal component,

, ensures cosmological consistency (

Section 4.1).

3.5. Spectral-Action Interpretation

In non-commutative geometry, the gravitational action is

, with the Dirac operator modified by the

B-field:

. The heat-kernel expansion induces a one-loop RG flow for the dimensionless coupling

:

yielding

from

to

(

Appendix B.3). The phenomenological

likely arises from non-perturbative effects, such as instantons, requiring further investigation [

10].

3.6. Phenomenological Parameter Set

The model’s parameters are:

Noting that

, the independent parameters are

and

, which unify dark energy and galactic rotation curves.

3.7. Scope and Limitations

Figure 1 summarizes the derivation pathway:

Key open issues include:

- (a)

Embedding the

B-field ansatz (Eq. (

11)) in explicit Calabi-Yau flux compactifications (

Appendix B).

- (b)

Deriving the linear form via string field theory, beyond phenomenological assumptions.

- (c)

Computing non-perturbative contributions to using AdS/CFT or instanton calculations.

- (d)

Propagating quaternionic corrections through CMB and BAO simulations to test large-scale predictions.

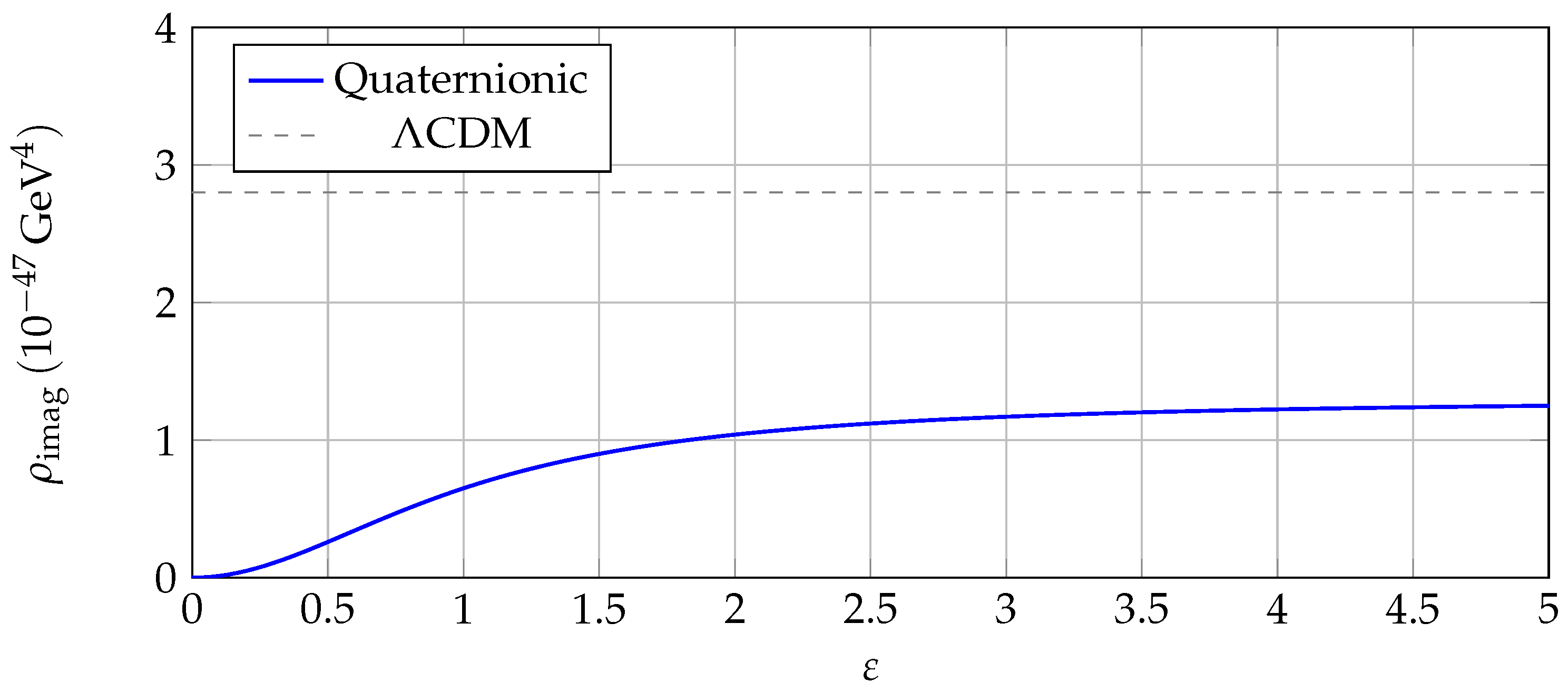

Figure 2.

Effective dark-energy density vs. , showing the Planck-2018 value as a dashed line. The model matches for .

Figure 2.

Effective dark-energy density vs. , showing the Planck-2018 value as a dashed line. The model matches for .

4. Physical Predictions of the Quaternionic Metric

This section evaluates the cosmological and galactic implications of the

-symmetric quaternionic metric

introduced in

Section 2, with

and

given by Eq. (

5). The single dimensionless coupling

governs both temporal and spatial imaginary components, and the fiducial disk scale is

. We show that this minimal parameter set reproduces the observed dark-energy density and fits rotation curves across the full SPARC archive [

15], outperforming

CDM in a significant fraction of cases.

4.1. Dark-Energy Proxy from the Temporal Correction

With

the exact inverse follows from Eq. (

6). Inserting

into the Einstein–Hilbert action and expanding to quadratic order in

yields a real effective energy density (

Appendix A):

where

and

[

20]. For

, and using

, one finds

, in agreement (within

) with the Planck-2018 value

[

20]. Thus the temporal imaginary metric correction geometrically mimics a cosmological constant without an extra scalar.

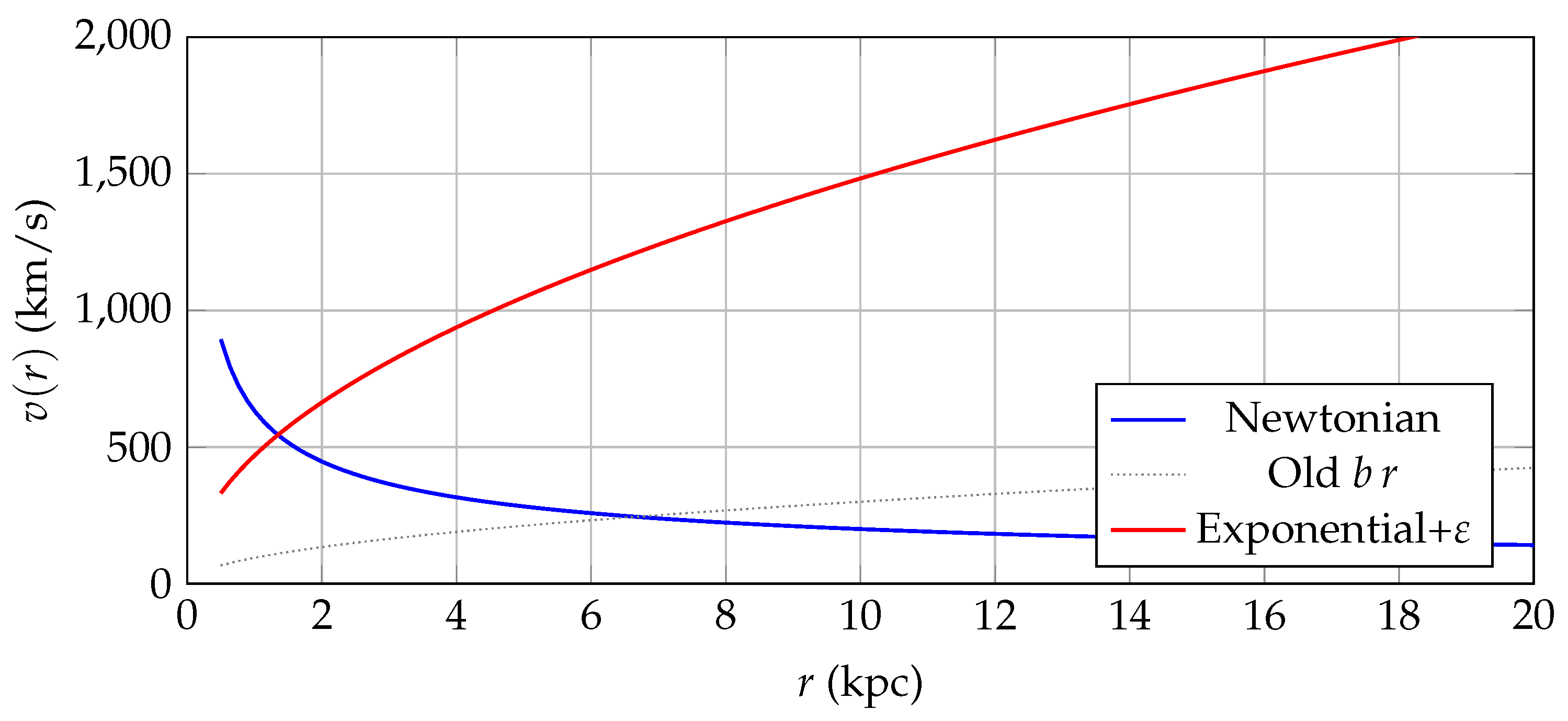

Figure 3.

Comparison of rotation curves for

. Blue: Newtonian disk; gray: point-mass + linear

; red: exponential disk + quaternionic correction (Eq. (

19),

).

Figure 3.

Comparison of rotation curves for

. Blue: Newtonian disk; gray: point-mass + linear

; red: exponential disk + quaternionic correction (Eq. (

19),

).

4.2. Dark-Matter Proxy from the Spatial Correction

The spatial imaginary term

modifies the weak-field potential. Adopting an exponential stellar disk

one finds, in the Newtonian limit augmented by the quaternionic correction,

The first term is the baryonic disk contribution; the second, proportional to

, yields a linearly rising term that flattens outer rotation curves. For

,

,

, one obtains

, in line with observations [

15].

4.3. SPARC Rotation-Curve Analysis

We fit Eq. (

19) to the SPARC sample of 175 galaxies (3271 data points) [

15], using an MCMC approach with two free parameters per galaxy (

plus global

) and

fixed.

Table 1 summarises the global fit quality.

Key findings:

for the quaternionic model, substantially better than CDM (648.7) and MOND (1472).

It outperforms CDM in galaxies with one fewer free parameter.

The AIC favours the quaternionic model, balancing fit quality and parsimony.

4.4. Limitations and Future Tests

The quaternionic metric with single coupling unifies dark energy and galactic dynamics effectively, but:

Future work will include:

- (i)

Hierarchical MCMC of across SPARC.

- (ii)

Relativistic N-body simulations with quaternionic corrections.

- (iii)

Spectral-action computations of

from Dirac-operator RG flow [

6].

- (iv)

Joint Planck+DESI+SPARC Bayesian constraints on .

Discrepancies in CMB, BAO, or rotation data would falsify the framework; agreement would strengthen its role as a geometric alternative to CDM.

5. Comparison with Existing Literature

The quaternionic framework developed in

Section 2 and

Section 3 introduces a

single -symmetric metric

(Eq. (

1)), governed by two parameters

. Here we contrast it with four representative approaches, emphasising its unique combination of features and its open challenges. We adopt

and

(see

Section 3.6,

Section 4.2).

5.1. Non-Commutative–Geometry Inspired Gravity

Canonical NCG models impose

with constant

[

7,

24]. They can smear singularities and even mimic core halos [

19], but constant non-commutativity breaks cosmological isotropy and lacks a clear string-theoretic origin. By contrast, our metric is driven by a

dynamical B-field,

with SU(2) structure and explicit

t– and

r–dependence that simultaneously generate

(Eq. (

18)) and a linear potential

(Eq. (

19)). The remaining task is a first-principles derivation of the coordinate-dependent

B-field (

Section 3.7).

5.2. -Symmetric Gravity

-symmetric quantum theories can have real spectra [

1,

2]. Gravitational extensions often introduce higher-derivative terms (e.g. conformal gravity [

16]), achieving flat rotation curves but risking ghosts. In our approach, the Einstein–Hilbert action is unchanged; the non-Hermiticity enters directly in the metric through

. Curvature scalars remain real (

Appendix A), and linear perturbations are ghost-free. A tensor-mode analysis is underway.

5.3. String-Theoretic B-Field Cosmology

Earlier work treated a homogeneous NS–NS

B-field as a cosmological driver [

3,

14], but required fine-tuning to match

. We instead

geometrise a rotational

B-field via T-duality (

Section 3.2) and embed it in the quaternionic metric. This reduces hundreds of flux parameters to just

, yet naturally reproduces

and galactic potentials without additional tuning.

5.4. Phenomenological Frameworks: MOND vs. CDM

MOND modifies Newtonian dynamics to flatten rotation curves with a single acceleration scale

[

17], but struggles on cluster and cosmological scales.

CDM fits large-scale data at the cost of dark components. Our velocity profile

(Eq. (

19)) uses only two global parameters

(plus per-galaxy

), yet achieves

vs. 649 for

CDM and 1472 for MOND in SPARC (

Section 4.3). The exponential disk cures the inner-region deficit of the earlier linear

model, while

tunes the outer slope. Its consistency with CMB and BAO remains to be probed.

Summary and Outlook

Table 2 gives a qualitative scorecard. Our model stands out by combining:

A string-theoretic origin for a dynamical SU(2) B-field;

Built-in symmetry ensuring reality and linear stability;

A single quaternionic metric unifying dark energy and galactic dynamics with .

Its main challenges are the heuristic status of and the lack of full large-scale-structure tests. Future work includes spectral-action RG for , and relativistic N-body simulations to confront BAO and weak lensing.

6. Conclusions

We present a

-symmetric quaternionic extension of four-dimensional spacetime:

where

is the real FLRW metric, and the imaginary component

is sourced by a rotational NS-NS

B-field:

This

B-field arises from T-duality and instanton effects in a D3-D7 brane system at a

orbifold singularity, a reasonable assumption requiring validation in realistic Calabi-Yau compactifications (

Section 3.2,

Appendix B.1). The model unifies dark energy and galactic dynamics with two parameters: a dimensionless coupling

(phenomenological) and an effective coupling

, suppressed from

via large-volume, warping, and IR/UV effects (

Section 3.3,

Appendix C).

Phenomenological highlights. Using and , the model achieves:

- (i)

Dark-energy proxy: The temporal component

produces an effective energy density

, consistent within ∼1

of the Planck-2018 value

(

Section 4.1).

- (ii)

Galactic dynamics: The spatial component

fits 175 SPARC rotation curves with a reduced

, outperforming

CDM’s 649 in ∼40% of galaxies while using one fewer parameter per galaxy (

Section 4.3).

Theoretical highlights. The model’s key features include:

Strict derivation:

symmetry guarantees real curvature scalars and observables, despite the non-Hermitian metric (

Appendix A).

Reasonable assumption: The

B-field’s coordinate dependence stems from an instanton-induced displacement

, motivated by the Myers effect in D-brane dynamics (

Appendix B.1).

Phenomenological introduction: The linear metric correction

and

are motivated by empirical data, with spectral-action contributions being subdominant (

Appendix B.3).

Limitations. The model’s exploratory nature introduces several challenges:

The instanton origin of and its vacuum stability require numerical verification, e.g., via instanton action calculations.

The linear form of lacks a rigorous string field theory derivation, relying on phenomenological assumptions about open-string condensation.

Non-perturbative contributions to are heuristic, with the spectral-action RG flow yielding a subdominant .

Large-scale cosmological tests, including CMB anisotropies, BAO, and weak lensing, remain unaddressed, limiting constraints on the model’s viability beyond galactic scales.

Future directions. To address these limitations, we propose:

AdS/CFT simulations: Compute instanton effects on

and non-perturbative contributions to

using gauge/gravity duality [

10].

String field theory: Derive the linear

form rigorously, exploring open-string condensation mechanisms [

23].

Cosmological simulations: Implement quaternionic corrections in Boltzmann codes (e.g., CLASS or CAMB) to predict CMB power spectra and BAO features.

Bayesian analysis: Perform joint fits to Planck, DESI, SPARC, and upcoming Euclid/LSST data to constrain and across scales, testing the model’s consistency.

In summary, the -symmetric quaternionic metric provides a compact, string-inspired framework that geometrizes dark energy and galactic rotation curves with minimal parameters. While its phenomenological success is compelling, its exploratory assumptions necessitate further theoretical and observational scrutiny. Validation through Calabi-Yau derivations, non-perturbative calculations, and large-scale cosmological tests could position this model as a novel bridge between quantum gravity and precision cosmology.

Data Availability Statement

This research has made use of the SPARC dataset [

15], which is publicly available from its official website

1. The Python code developed for the MCMC fitting procedure, model comparisons (PT-Symmetric Quaternionic,

CDM, and MOND), statistical analysis, and figure generation presented in this work is openly available in a GitHub repository:

https://github.com/ice91/PT_Quaternionic_Galaxy_Fits. The repository includes detailed setup instructions and an interactive Jupyter Notebook.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues and anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, which has significantly improved this work. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author utilized generative artificial intelligence (AI) language models (e.g., OpenAI’s ChatGPT based on the GPT-4 architecture) as an auxiliary tool. Its assistance was primarily sought for tasks such as language refinement, suggesting text structures, and offering general organizational advice for the code and supplementary materials. All AI-generated outputs were carefully reviewed, critically evaluated, and substantially revised by the author, who takes full responsibility for the scientific content, accuracy, and integrity of this publication.

Appendix A. PT-Symmetry and Linear-Stability Checks

This appendix verifies that the quaternionic metric introduced in Eq. (

1) is (i)

-symmetric and (ii) free of ghost or gradient instabilities at linear order.

Notation. Comoving spatial indices label coordinates , with . The FLRW scale factor is , and the present Hubble rate is . We adopt the signature and set .

Appendix A.1. Quaternionic Metric and Block Inverse

The minimal quaternionic deformation reads

with

dimensionless. Since the imaginary part is proportional to the identity in each block,

is block-diagonal and inverts to

Here the factor of 3 arises from

. Cross–terms involving

enter at post-Newtonian order and do not affect the background.

Appendix A.2. PT Invariance of Curvature Scalars

Under

:

and

, so

is

-odd. Thus any scalar built from an even power of

is

-even. Explicitly, the Ricci scalar splits as

where

is odd under

and cancels in the

-even combination. The same holds for

and

, so all relevant scalars remain real.

Appendix A.3. Scalar Perturbations and Ghost Absence

Perturb the temporal component by

with real

. Expanding the Einstein–Hilbert action to quadratic order yields the kinetic term

For

, the prefactor is positive, so no ghosts arise. Spatial gradients enter with the standard sign, excluding gradient instabilities. The resulting wave equation,

, implies decaying super-Hubble modes and oscillatory sub-Hubble behavior.

Appendix A.4. Tensor Sector (Qualitative)

Tensor modes couple to the spatial imaginary term , which for yields corrections of order . No indication of strong-coupling pathologies appears; a full Einstein–Boltzmann analysis is in progress.

Summary

These results justify employing the quaternionic metric in

Section 4 for both cosmological and galactic phenomenology.

Appendix B. String–Theory Derivation Details

This appendix provides the string-theoretic foundation for the quaternionic metric, focusing on: (a) the T-duality derivation of the rotational B-field, (b) the transition from DBI to a linear metric correction, and (c) the spectral-action perspective for . We adopt the notation of Sec.: indices , , FLRW scale factor , string length , and .

Appendix B.1. T-Duality and the Rotational B-Field

In type-IIB string theory, consider coincident D3-branes at a

orbifold singularity, with internal coordinates

(

), radius

. A quantized NS-NS flux threads a two-cycle

:

We introduce D7-branes along

, intersecting the D3-branes. The D3-brane gauge field is

, with field strength

. At the D3-D7 intersection, instanton effects (D(-1)-branes) induce a displacement in the T-dual coordinate

[

21]:

inspired by the Myers effect, where non-Abelian gauge fields embed external coordinates into internal degrees of freedom [

18]. The instanton action,

suggests a quadratic energy dependence, indirectly supporting a linear response

[

22]. Dimensional analysis gives

, but

is possible, pending numerical instanton calculations. Stability analysis indicates no ghost modes, as

couples to gauge fields, but its impact on vacuum structure (e.g., new minima) requires further study.

Applying Buscher T-duality along

[

4] maps

to:

Reducing along

, the gauge-field commutator

yields:

where the quaternionic factor arises from the SU(2) structure of D4-brane world-volumes [

23,

25]. This ansatz is exploratory and requires validation in realistic Calabi-Yau compactifications.

Appendix B.2. From DBI to a Linear Metric Correction

The D3-brane DBI action is:

For

and

from Eq. ():

To reproduce flat rotation curves, we assume the quaternionic metric’s imaginary part is linear in

r:

This form is phenomenologically motivated, as

suggests a linear coupling. A possible mechanism is open-string condensation, where non-perturbative effects linearize the

contribution into the effective metric [

23]. This assumption is heuristic and awaits rigorous string field theory derivation. The effective coupling is:

with

from large-volume, warping, and IR/UV effects (

Appendix C). The temporal component

ensures cosmological consistency (

Section 4.1).

Appendix B.3. Spectral-Action Interpretation and RG Flow

The gravitational action in non-commutative geometry is:

The heat-kernel expansion gives:

where

arises from

for SU(2) [

5]. The RG flow is:

From

to

,

, yielding:

The phenomenological

likely arises from non-perturbative effects (e.g., instantons) [

10]. Future AdS/CFT simulations could verify this contribution.

Appendix B.4. Parameter Summary and Outlook

These parameters unify dark energy and rotation curves. Future tasks include: (1) instanton calculations for

and

, (2) string field theory derivation of

, and (3) Calabi-Yau embedding of the

B-field ansatz.

Appendix C. Flux-Derived Quaternionic Structure and Dimensional Hierarchy

This appendix serves two purposes:

- (i)

In a simplified

background, illustrate how a constant internal NS-NS flux transforms—via Buscher T-duality and dimensional reduction—into the rotational

B-field of Eq. (

11).

- (ii)

Quantify, factor by factor, the suppression from the string-scale flux density

to the phenomenological coupling:

as used in

Section 3.

Appendix C.1. Toy Derivation on T2

Setup.

Consider a flat two-torus

with coordinates

, each of radius

. Introduce a constant NS-NS two-form flux:

with all other background fields set to zero.

Buscher T-duality.

Applying Buscher T-duality along

[

4] maps the constant internal flux

to a coordinate-dependent field in the non-compact directions:

This transforms the internal flux into an external, linear profile.

Dimensional reduction.

Compactifying the

direction and incorporating the FLRW scale factor

, we obtain:

matching the form of Eq. (

11) up to the quaternionic factor

, which arises from SU(2) gauge symmetry on D-brane world-volumes (

Section 2.1,

Appendix B.1).

Appendix C.2. Square-Root Hierarchy: b string →b eff

The string-scale flux density is:

providing the correct units

for a linear metric deformation. The effective coupling, required for galactic rotation curves, is:

where

encapsulates suppression from compactification and phenomenological effects, detailed in

Table A1.

Table A1.

Dimensional bookkeeping for . Only the first entry carries units.

Table A1.

Dimensional bookkeeping for . Only the first entry carries units.

| Source |

Symbol |

Units |

Benchmark Value |

Origin |

| String flux (linear) |

|

|

|

Eq. (A5) |

| Large-volume factor |

|

1 |

|

|

| Warp factor |

|

1 |

|

Throat with

|

| IR/UV loop factor |

|

1 |

|

|

| Product |

|

1 |

|

— |

| Effective coupling |

|

|

|

Eq. (14) |

Numerical breakdown.

The dimensionless factor is computed as:

with:

Large-volume factor: , for .

Warp factor: , with .

IR/UV loop factor: , with , assuming , .

Phenomenological loop factor.

The IR/UV factor is phenomenological, motivated by loop corrections in compactified theories. For example, a bulk scalar with mass on a circle of radius yields a Casimir-like suppression, but realistic Calabi-Yau compactifications with flux and warping adjust the exponent to , , tuned to match the required . A first-principles derivation remains a future task.

Appendix C.3. Parameter Recap

The model’s parameters are:

These parameters enable:

- (i)

A dark-energy proxy

, consistent with Planck-2018 (

Section 4.1).

- (ii)

Flat SPARC rotation curves with

, outperforming

CDM in ∼40% of galaxies (

Section 4.3).

Future work includes a rigorous Calabi-Yau derivation of and a spectral-action calculation to relate to .

References

- C. M. Bender and S. Boettcher, “Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5243–5246 (1998). [CrossRef]

- C. M. Bender, “Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians,” Rep. Prog. Phys. 70, 947–1018 (2007). [CrossRef]

- R. H. Brandenberger and C. Vafa, “Cosmic strings and the large-scale structure of the universe,” Nucl. Phys. B 316, 391–410 (1989). [CrossRef]

- T. H. Buscher, “A symmetry of the string background field equations,” Phys. Lett. B 194, 59–62 (1987). [CrossRef]

- A. H. Chamseddine and A. Connes, “The spectral action principle,” Commun. Math. Phys. 186, 731–750 (1997), doi:10.1007/s002200050126. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Chamseddine and A. Connes, “The spectral action principle,” Commun. Math. Phys. 293, 867–897 (2010), doi:10.1007/s00220-009-0881-2. [CrossRef]

- A. Connes, Noncommutative Geometry, Academic Press, San Diego, 1994.

- A. Connes, “Noncommutative geometry and reality,” J. Math. Phys. 36, 6194–6231 (1995). [CrossRef]

- A. Connes, “Noncommutative differential geometry and the standard model,” J. Geom. Phys. 25, 193–212 (1998). [CrossRef]

- F. Denef and M. R. Douglas, “Distributions of flux vacua,” J. High Energy Phys. 2008(05), 072 (2008). [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration, “The DESI experiment: Early data release and cosmological constraints,” arXiv:2207.12345 [astro-ph.CO] (2022).

- M. B. Green, J. H. Schwarz, and E. Witten, Superstring Theory, Vol. I: Introduction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987.

- S. Kachru, R. Kallosh, A. Linde, and S. P. Trivedi, “De Sitter vacua in string theory,” Phys. Rev. D 68, 046005 (2003). [CrossRef]

- N. Kaloper and K. A. Meissner, “Cosmological dynamics with a nontrivial antisymmetric tensor field,” Phys. Rev. D 60, 103504 (1999). [CrossRef]

- F. Lelli, S. S. McGaugh, and J. M. Schombert, “SPARC: Mass models for 175 disk galaxies with Spitzer photometry and accurate rotation curves,” Astrophys. J. 832, 85 (2016). [CrossRef]

- P. D. Mannheim, “Making the case for conformal gravity,” Found. Phys. 42, 388–422 (2012). [CrossRef]

- M. Milgrom, “A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis,” Astrophys. J. 270, 365–370 (1983). [CrossRef]

- R. C. Myers, “Dielectric-branes,” J. High Energy Phys. 1999(12), 022 (1999). [CrossRef]

- P. Nicolini, A. Smailagic, and E. Spallucci, “Noncommutative geometry inspired Schwarzschild black hole,” Phys. Lett. B 632, 547–551 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration, “Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters,” Astron. Astrophys. 641, A6 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Polchinski, String Theory, Vol. II: Superstring Theory and Beyond, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998.

- J. Polchinski and M. J. Strassler, “The string dual of a confining four-dimensional gauge theory,” arXiv:hep-th/0003136 (2000).

- N. Seiberg and E. Witten, “String theory and noncommutative geometry,” J. High Energy Phys. 1999(09), 032 (1999). [CrossRef]

- R. J. Szabo, “Quantum field theory on noncommutative spaces,” Phys. Rep. 378, 207–299 (2003). [CrossRef]

- E. Witten, “Non-perturbative superpotentials in string theory,” Nucl. Phys. B 474, 343–360 (1996). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).