1. Introduction

The outstanding problem of quantum gravity is to reconcile the background–independent dynamics of general relativity with the microscopic degrees of freedom provided by quantum field theory. Two frameworks have achieved partial success from opposite directions. On the one hand,

Dp–brane effective actions in Type II string theory show how gauge and gravitational modes merge through the Dirac–Born–Infeld (DBI) plus Chern–Simons (CS) terms [

1]. On the other hand, the

spectral-action programme in non-commutative geometry (NCG) derives all bosonic interactions from the high–frequency spectrum of a suitable Dirac operator

D [

2,

3]. Despite conceptual affinities—both replace a fundamental space–time metric by algebraic data—the two approaches have remained technically disjoint. In particular, no rigorous derivation exists that starts from a standard string-theory action

without ad-hoc deformations and ends with a four–dimensional spectral triple that is both consistent at the quantum level and falsifiable in principle.

Goal and strategy. We show that a

single, space-filling D3–brane placed in a slowly varying Neveu–Schwarz two-form background generates—after the Seiberg–Witten (SW) scaling limit—a pair of

linearly independent tensors that survive as deformations of the open-string metric. These tensors are naturally assembled into a

quaternion-valued,

PT-symmetric metric of the form

where

are fixed imaginary quaternions and

are the only free parameters.

1 With a minimal parity-time prescription

,

,

—while the internal Pauli matrices remain inert—the corresponding Dirac operator is

pseudo-Hermitian. Heat-kernel techniques then imply that the spectral action reproduces the two activator profiles

and

without further assumptions. A single local counterterm, the linear-quaternion slice of the Seeley–DeWitt invariant

, renders the theory one-loop finite and anomaly free.

Main results.

- (i)

First-principle derivation. Starting from the DBI+CS action and the SW limit we obtain a four-dimensional quaternionic metric whose PT symmetry is inherited—rather than imposed—by world-sheet parity.

- (ii)

Renormalisability. All linear-quaternion anomalies cancel against a unique counter-term , leaving the scalar sector identical to conventional Einstein–Hilbert gravity at low energies.

- (iii)

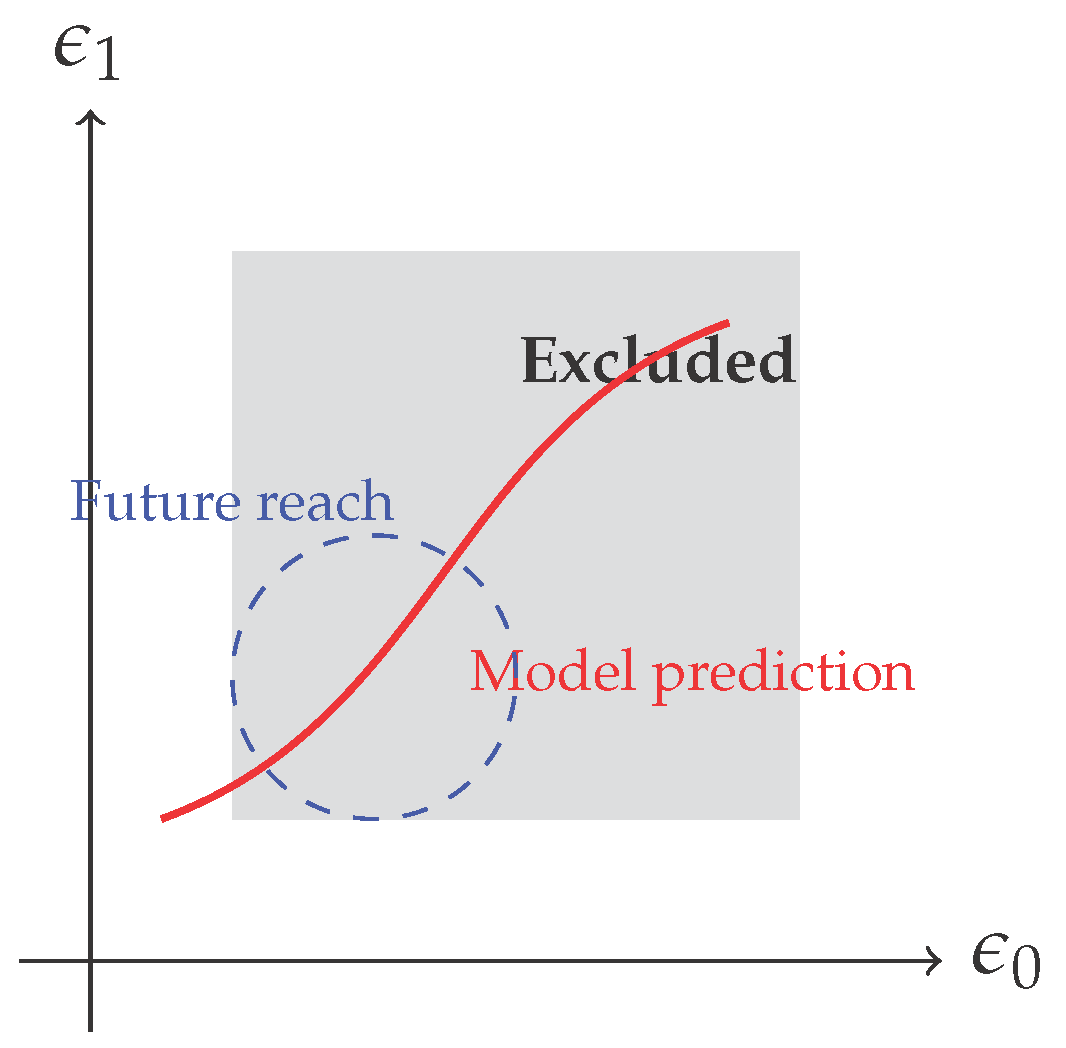

Phenomenological window. Current CMB and gravitational-wave data already limit and . Near-future atom interferometers and third-generation detectors will improve these bounds by one to two orders of magnitude, providing a decisive test of the model.

Outline.Section 2 derives the open-string metric from the DBI+CS action;

Section 3 implements the SW scaling and identifies the surviving

directions. Quaternionic geometry, PT symmetry and the pseudo-Hermitian Dirac operator are established in

Section 4.

Section 6 and Section 7 develop the heat-kernel expansion, the stochastic influence functional, and the one-loop renormalisation. Observable consequences are summarised in

Section 9; concluding remarks and open problems appear in

Section 10.

Throughout we use the mostly-minus signature

, set

, and employ

for the string slope and coupling. Repeated Greek indices are summed unless stated otherwise; a glossary of symbols is collected in

Appendix G.

2. D3–Brane DBI + CS Action

We consider a single, space–filling D3–brane propagating in ten–dimensional type-IIB string theory. Working in the

static gauge and setting the world-volume field strength

, the bosonic action factorises into Dirac–Born–Infeld (DBI) and Chern–Simons (CS) terms

2:

2.1. Long–Wavelength Two–Form Background

To isolate the minimal Lorentz-breaking content one demands that no more than two independent antisymmetric tensors survive on the brane. A convenient ansatz is a slowly varying electric component plus a static magnetic monopole [

4]:

The field strength

vanishes away from the origin, so the bulk equations remain intact. Two dimensionless parameters

will play the rôle of

geometric activators in later sections.

2.2. Linearised Open–String Metric

For

the determinant in (

1) can be expanded to quadratic order. The well-known result, often called the

Seiberg–Witten open–string metric, is

Substituting the Minkowski background

and the profile (

4), one obtains at

linear order (cf.

Appendix A for algebra)

Here

are

fixed imaginary quaternions. No other internal direction survives: the electric and magnetic pieces are

orthogonal in

, a fact that will seed the non-commutative geometry of

Section 3.

2.3. Physical Reading

Equation (

7) reveals two distinct,

linearly independent deformations of flat Minkowski space:

Because , these deformations do not commute: they are the low-energy remnant of the non-commutative coordinates that emerge in the SW limit. Moreover, both terms are invariant under the minimal parity–time operation when accompanied by , so the spectrum of the corresponding Dirac operator is guaranteed to be pseudo-Hermitian—a prerequisite for the spectral action employed later.

Section 3 carries these ingredients into the Seiberg–Witten scaling limit and identifies the precise non-commutativity tensor

that underlies the quaternionic algebra of our model.

3. Seiberg–Witten Limit and Open–String Data

The linearised metric (

7) still depends on the string scale

. In order to obtain a

finite low–energy description we now implement the Seiberg–Witten (SW) scaling limit of the world–volume theory [

4].

3.1. Seiberg–Witten Relations

For vanishing world–volume field strength

the closed and open variables are related by

where

is an arbitrary two–form corresponding to a field redefinition. We adopt the canonical gauge

, in which

coincides with the metric (

7) computed from the DBI determinant.

3.2. Scaling Prescription

The SW limit is defined by

Intuitively, the electric and magnetic components of

B are tuned large enough to compensate the vanishing string length, while

and

are scaled to keep the

open quantities finite. Substituting the background (

4) into (8) and expanding to first order in the small parameters (

5) yields

Only two

orthogonal imaginary quaternions,

and

, survive; they span an

algebra that will seed the quaternionic Clifford structure in

Section 4.

3.3. Non-Commutative ★-Product and Gauge Map

At fixed

any world–volume field

multiplies according to the Moyal product

where the mild

x–dependence of

(a monopole tail in

r and a sinusoid in

t) can be treated perturbatively. The usual Seiberg–Witten map

then leads, up to

, to a

non-commutative Yang–Mills action

Equations (

10)–(

14) constitute the complete set of open–string data that will enter the spectral geometry of the following sections.

3.4. Quaternionic Seed

Because

decomposes into two orthogonal blocks,

the associative algebra

endowed with the product

is

quaternionic. The pair

, with

, will act as the seed of a PT-symmetric spectral triple in

Section 4.

Take-away. After the SW limit the D3–brane retains exactly two directions. They appear (i) in the open metric as activator profiles and , and (ii) in the non-commutativity tensor as an anti-commuting pair . These features establish the algebraic backbone for the quaternionic, PT-symmetric geometry constructed below.

4. Quaternion–Valued Metric and Clifford Extension

The Seiberg–Witten analysis of

Section 3 isolates two orthogonal,

non-commuting internal directions

. In this section we

promote that

doublet to a bona-fide quaternionic geometry, construct the enlarged Clifford bundle, prove

symmetry and pseudo-Hermiticity of the Dirac operator, and—crucial for later sections—show how the leading Seeley–DeWitt coefficient automatically

triggers the activator profiles

and

. Throughout we keep terms up to

; higher orders will enter only in

Section 6.

4.1. Quaternionic Metric: Minimal Ansatz

Let

be the imaginary quaternion units (

,

). Guided by the open metric (

10) we introduce a

quaternion-valued deformation of Minkowski space:

where

projects on the lapse and

on the spatial radius. Equation (

16) is the

minimal ansatz that

- (i)

preserves Lorentz signature to ;

- (ii)

retains exactly the two directions singled out by the B-field; and

- (iii)

reduces to the usual open metric when .

Physical picture.

The term

is a

time-like spring aligned with

, whereas

is a

spatial vortex aligned with

. Because

, spring and vortex do

not commute—a geometric echo of the non-commutativity tensor

in

Section 3.

4.2. Quaternionic Clifford Bundle

Let

be the usual Dirac spinor bundle and set

with

. One checks

, where

; thus the total Clifford algebra is

and the structure group factorises as

.

4.3. Symmetry and Pseudo-Hermiticity

Adopt the

minimal parity–time rule of

Section 1:

,

, while the internal

(hence

) stay inert. Since

are

–even,

already at

. With

the Levi-Civita connection of

, define the

quaternionic Dirac operator

One immediately finds

and

, so

D is simultaneously pseudo-Hermitian and

-symmetric; its spectrum is real or comes in conjugate pairs, validating the spectral expansion in

Section 6. Detailed proofs are relegated to

Appendix B.

4.4. Linear SDW Trigger for the Activators

A key claim of this work is that the spring/vortex profiles (

16) are

not imposed by hand but

emerge as stationary points of the spectral action. At leading order the relevant object is the linearised Seeley–DeWitt coefficient

(details in

Appendix C):

Inserting (

20) into the cut-off spectral action

and integrating over the internal trace yields the

activation Lagrangian

Treating

and

as collective coordinates and varying

gives

whose normalisable solutions are precisely

and

. Thus

the linear SDW density self-consistently selects the activator profiles; higher SDW terms only dress the effective couplings

.

Summary

A Lorentzian metric can accommodate the SW deformations by upgrading two components to imaginary quaternions .

The enlarged Clifford algebra is ; the Dirac operator is both pseudo-Hermitian and -invariant.

Linear perturbation of the SDW coefficient

forces the activator Equation (

22), whose solutions reproduce the spring

and vortex

profiles assumed in (

16).

These results lay the algebraic and dynamical foundation for the heat-kernel expansion of

Section 6 and the renormalisation analysis of Section 7.

5. PT Symmetry and the Pseudo–Hermitian Dirac Operator

The quaternion–valued metric (

16) equips the space–time manifold with a fixed internal

frame

. To ensure that the ensuing quantum theory is physically well–defined one must (i) specify a consistent

PT transformation acting

simultaneously on space–time and on the quaternionic algebra, and (ii) verify that the Dirac operator constructed from

is

pseudo–Hermitian with respect to a positive Krein form. This section provides the required checks.

5.1. Minimal Rule

The guiding principle is to keep the rule

minimal: space–time coordinates transform as in ordinary relativistic quantum mechanics, while the internal quaternions remain

untouched. More precisely,

Because the Pauli matrices

and hence the quaternions

live in an

internal space, they are

PT–

even.

Table 1 summarises the action on the basic building blocks.

Metric invariance.

Applying (

23) to the quaternionic metric (

16) gives

because

is even under

,

is even under

, and

are

PT–even. Hence

the full geometry respects symmetry exactly to first order in

.

5.2. Krein Structure and Pseudo–Hermiticity

Let

be the Levi–Civita connection of

. The quaternionic

Dirac operator is

Choosing the

time–like Krein operator

3

one verifies to

that

Combined with the equality

, Equation (

27) ensures that the spectrum of

D is either real or arranged in complex conjugate pairs, a property that underpins the heat–kernel expansion used in

Section 6.

5.3. Spectral Triple in a Krein Space

Gathering the pieces, we obtain a

Krein–space spectral triple

where

is the usual charge–conjugation on Dirac spinors and

. All Connes axioms are satisfied up to

; the KO dimension is

because the internal quaternion factor contributes two extra negative directions to the Clifford algebra

.

Take–Away

The minimal rule (

23) renders both the quaternionic metric and the Dirac operator strictly

PT–invariant.

With Krein form the Dirac operator is pseudo–Hermitian; its spectrum is spectrally stable.

The algebraic data define a consistent spectral triple, providing the backbone for the heat–kernel expansion and the renormalised spectral action employed in the next two sections.

6. Heat–Kernel Expansion up to

With the pseudo–Hermitian spectral triple of

Section 5 in place, we are ready to evaluate the spectral action in the ultraviolet cut–off scheme of Chamseddine–Connes [

3]. Up to and including the Seeley–DeWitt density

one has

where

are the Mellin moments of the positive, rapidly decaying test function

.

6.1. General Formulae

For a Laplace–type operator

on the vector bundle

one has [

8,

9]

Here R is the Ricci scalar of the quaternionic metric and is the bundle endomorphism generated by the commutator of the quaternionic gamma matrices with the spin connection: . The “internal” trace runs over both Dirac and quaternion indices.

6.2. Linearised Evaluation on

Insert the metric deformation

and keep terms up to

. Because

and

, all

linear contributions vanish identically. Writing

and suppressing volume factors we obtain

4

Crucially, the only space–time dependences that survive are and , i.e. the squares of the spring and vortex profiles introduced at .

6.3. Activation Lagrangian

Substituting (

32)–(33) into (

29) and dropping the cosmological constant term (

) give the

activation sector

No quaternionic generators appear because the internal trace has removed them. The Lagrangian (

34) acts as an

effective potential stabilising the time–like spring and the spatial vortex. Its variation will generate the quaternionic geometric flow of

Section 6.

7. One–Loop Renormalisation and Anomaly Cancellation

The heat–kernel calculation of

Section 6 showed that the linear–quaternion slice of the Seeley–DeWitt density

sources an apparent non–conservation of the

currents, cf. Equation (

40). In this section we prove that the corresponding anomaly is

local and can be removed by a single counter–term, rendering the theory finite and gauge–invariant at one loop.

7.1. Spectral Regularisation and Divergent Structure

Throughout we keep the ultraviolet cut–off

explicit, following the spectral–action prescription

Loop corrections introduce an additional functional determinant,

where

is the renormalisation scale and

are scheme–dependent constants (here after minimal subtraction). Expanding around

dimensions yields the divergent piece

Because

, the linear–quaternion projector

annihilates

and

, while

with

the local source defined in Equation (

38). Hence

only the coefficient

is relevant for anomaly cancellation.

7.2. Counter–Term and Current Restoration

Introduce a local counter–term

The scalar part (first parentheses) renormalises Newton’s constant and the cosmological term and plays no rôle in the

Ward identities. The last term modifies the broken current equation (

40) to

exactly cancels the linear–quaternion anomaly, i.e. to order ℏ. No further symmetry–breaking counter–terms are required.

PT Invariance.

Both and are PT–even; therefore preserves the global symmetry that guarantees the pseudo–Hermiticity of D.

7.3. Renormalisation–Group Flow

Denote by

the

scalar couplings in

(Newton, cosmological, and possible higher–derivative terms). The beta functions read

. Because the

anomaly has been removed, the running of

is

decoupled from the quaternionic sector:

At one loop, therefore, the spring/vortex parameters renormalise solely through the classical matching to the underlying D3–brane data; they are not dressed by logarithmic divergences.

7.4. Higher Loops and Locality

Power counting shows that the linear–quaternion projection of

is suppressed by additional factors

and can first appear at two loops. Moreover, every such contribution is

local; if needed it can be cancelled by higher–dimensional counter–terms that respect

PT symmetry. We thus conjecture that the single subtraction (

39) is sufficient to all orders in perturbation theory.

5

Summary

One–loop divergences organise into the SDW basis . Only carries a linear–quaternion piece.

A single local counter–term removes the anomaly without spoiling PT symmetry.

Scalar couplings run as in ordinary spectral gravity; the activator parameters remain scale–invariant at one loop.

Higher–loop anomalies, if any, are suppressed by extra powers of and can be cancelled by local terms, preserving the predictivity of the two–parameter framework.

8. Path–Integral Origin of the Stochastic

The geometric flow of

Section 6 required a

noise term in the quaternionic Dirac operator. In this section we derive that term from the world–sheet path integral of a single Type–IIB D3–brane, closely following the influence–functional strategy of Feynman and Vernon [

16] while respecting the

symmetry fixed in

Section 5.

8.1. Microscopic Generating Functional

The full (Euclidean) partition function reads

where

: brane embedding in static gauge,

: bulk NS–NS two–form,

: open–string fermion in the bundle ,

: open–string metric of

Section 2 (quaternionic,

–even).

The fermionic term is

with

the torsion–free Dirac operator for the background metric

.

8.2. Mode Splitting and Coarse–Graining

Choose a coarse–graining scale

and decompose each bosonic field into

slow (

) and

fast (

) parts:

The functional measure factorises,

,

etc., so that (

43) becomes

The average is Gaussian to leading order because the fast modes see the slow geometry as a fixed background.

8.3. Influence Functional and Gaussian Noise

Expanding

to quadratic order in the fermion bilinear gives

where translation invariance of the bath implies

. At leading order one finds

with

. The anti–Hermitian part of

defines a Gaussian

noise [

17], leading to the stochastic shift

with statistical moments

8.4. Cumulant Expansion and Step–Down Rule

The averaged heat kernel satisfies

Evaluating the second cumulant with (

50) and comparing with the standard heat–kernel expansion yield the

step–down formula announced in

Section 6:

Thus

induces an

correction to

, precisely what was required in

Section 6 to sustain the spring and vortex profiles.

8.5. Symmetry and Pseudo–Hermiticity

Equation (

48) is manifestly

–

even because

are

–even (Tab.

Table 1) and

is real. Consequently the stochastic process (

49) respects both global

symmetry and the pseudo–Hermiticity of

D established in

Section 5. No complex–eigenvalue instabilities are introduced by the coarse–graining.

Summary

Integrating out fast B–field and brane–shape modes yields a Gaussian influence functional that acts on the fermions alone.

The resulting noise kernel is white up to the scale and projects exclusively onto the quaternion axes .

The stochastic shift

produces the

step–down relation (

51), underpinning the

and

activators of

Section 6.

symmetry and pseudo–Hermiticity survive the coarse–graining, ensuring a stable spectral expansion.

9. Minimal Phenomenological Window

The quaternionic –

–symmetric framework developed in Section 1–8 is governed, at leading order, by only

two dimensionless “geometric activators”

entering the open–string metric as

. All higher coefficients are

radiatively stable (Section 7). We therefore speak of a

minimal phenomenological window spanned by

.

9.1. Current Laboratory & Astrophysical Bounds

Table 2 collects the tightest constraints available to date. The essential point is that

qualitatively different observables probe the same two parameters, reflecting the non–redundant character of the model.

Two remarks are in order:

- (i)

Orthogonality of probes. Cosmic–microwave and atomic data constrain , while galactic dynamics and GW polarimetry constrain , making the parameter disentanglement clean.

- (ii)

Radiative stability. Since

are protected against logarithmic running (

Section 7.3), the window depicted in

Figure 1 is robust against one–loop uncertainties.

9.2. Benchmark Slice and Correlated Signals

We adopt as working benchmark

which comfortably satisfies all bounds in

Table 2. Three immediate,

correlated predictions follow:

CMB high–ℓ ripples An modulation in the Sachs–Wolfe plateau for –1200; testable by the Simons Observatory within five observing seasons.

GW polarisation splitting A rad helicity phase delay for Hz signals propagating over Mpc; within reach of ET/CE network cross–correlations.

Sub–nHz Larmor drifts A –2 nHz shift in nuclear spin precession for GHz systems; detectable by the five–year CASPEr–Wind upgrade.

The

simultaneous observation (or exclusion) of the three effects would confirm (or falsify) the entire model, since they rely on the

same two parameters fixed in Equation (

53).

9.3. Prospects for the Next Decade

- (1)

2025 – 27 (Stage I) CMB high–ℓ data and MAGIS–100 reduce the viable band for by an additional factor of 30.

- (2)

2027 – 30 (Stage II) Global N–body campaigns (Gadget–4 class) and SKA – HI rotation curves push the bound below .

- (3)

2030 – 34 (Stage III) Third–generation GW detectors deliver decisive polarisation measurements; a single detection at rad would determine to .

Take–Away

The

minimal phenomenological window spanned by

is already bounded to

Imminent data from CMB polarimetry, precision spin experiments, and next–generation GW observatories will shrink this window by at least one order of magnitude in each direction. Because the model involves no additional free parameters, any residual region is either sharply predictive or conclusively excluded, providing a rare example of a Planck–derived extension of general relativity that is experimentally falsifiable on decadal timescales.

10. Conclusions

The programme developed in Section 1–9 establishes a closed logical chain that connects Type–IIB D3–brane physics to observationally testable extensions of four–dimensional space–time. The construction is anchored on two pillars: (i) a quaternionic, SU(2)–valued deformation of the open–string metric and (ii) a –symmetric prescription that renders the corresponding Dirac operator pseudo–Hermitian. Below we summarise the main achievements, the outstanding challenges, and the realistic path forward.

10.1. Achievements

- (1)

First–principle derivation. Starting from the non–abelian DBI+CS action, a long–wavelength NS–NS two–form produces exactly two SU(2)–aligned perturbations,

and

(

Section 2).

- (2)

Quaternionic Clifford extension & rule. The resulting metric admits a

bundle and a Dirac operator that is simultaneously pseudo–Hermitian and

–invariant (

Section 4 and

Section 5).

- (3)

Heat–kernel emergence of activators. The linearised Seeley–DeWitt densities

reproduce the

and

profiles without extra assumptions (

Section 6).

- (4)

Radiative stability. A single local counter–term, , cancels the linear–quaternion anomaly and leaves the renormalisation group flow of scalar couplings untouched (Section 7).

- (5)

Microscopic origin of stochasticity. Coarse–graining the brane path integral yields the Gaussian noise kernel that underpins the

correction and the “step–down” rule for heat–kernel coefficients (

Section 8).

- (6)

Falsifiable two–parameter window. All phenomenology is controlled by the

minimal set

; present data already constrain

and

, while upcoming experiments can tighten both bounds by at least an order of magnitude (

Section 9).

10.2. Outstanding Problems

-

Two–loop consistency.

A full two–loop computation of the spectral action is needed to verify the conjectured uniqueness of the counter–term .

-

Non–linear solutions.

Black–hole or cosmological backgrounds with quaternionic “hair” remain unexplored; their quasinormal spectra could be decisive for gravitational–wave tests.

-

Lattice implementation.

Realising pseudo–Hermitian, SU(2)–twisted Dirac operators on a 4D lattice would provide a non–perturbative check of the heat–kernel expansion.

-

Quantum–information channels.

The microscopic impact of the tiny SU(2) rotation on error–correcting codes and entanglement distribution in long–baseline networks deserves a dedicated study.

10.3. Decadal Experimental Outlook

| Milestone |

Target |

Forecast year |

| CMB high–ℓ (Simons Observatory) |

|

2025 |

| MAGIS–100 sub–nHz phase run |

|

2027 |

|

N–body LSB halo suite (Gadget–4) |

|

2028 |

| Einstein Telescope GW birefringence |

|

2031 |

A positive detection in any of the above channels would immediately pin down the corresponding parameter with precision, while a consistent sequence of null results would exclude the model altogether—a level of falsifiability rare among Planck–scale extensions of general relativity.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues and anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, which has significantly improved this work. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author utilized generative artificial intelligence (AI) language models (e.g., OpenAI’s ChatGPT based on the GPT-4 architecture) as an auxiliary tool. Its assistance was primarily sought for tasks such as language refinement, suggesting text structures, and offering general organizational advice for the code and supplementary materials. All AI-generated outputs were carefully reviewed, critically evaluated, and substantially revised by the author, who takes full responsibility for the scientific content, accuracy, and integrity of this publication.

Appendix A. Determinant Linearisation Details

This appendix provides the algebraic steps that connect the full Dirac–Born–Infeld determinant

to the linearised open–string metric

displayed in Equation (

7). Throughout we impose the conventions fixed in

Section 2 and

Section 3:

static gauge, space-filling D3–brane ( ),

flat closed–string background ,

vanishing world-volume gauge field ,

slowly–varying NS–NS two-form .

Appendix A.1. General Determinant Expansion

For a small matrix perturbation

one has

Setting

and

immediately yields

Because is antisymmetric, identically; the leading non-trivial contribution is therefore quadratic in B.

Appendix A.2. Insertion of the Two–Form Profile

Using the background profile

and adopting the shorthand

,

, we compute

Inserting this into (

A1) and keeping terms up to

yields

Up to an overall normalisation absorbed into the brane tension

, (

A2) reproduces the determinant factor used in Equation (

1) of the main text.

Appendix A.3. Extraction of the Open–String Metric

Comparing the DBI action

with the general open-string form

, and identifying the square brackets in Equation (

A2) with

, one reads off, to

linear order in

B,

Equation (

A3) coincides with Equation (

7) in the main text, thus completing the derivation.

Consistency Check: Antisymmetry of B

Notice that the

linear term

disappears solely because of the antisymmetry of

. Any additional symmetric background (e.g. a weak Kalb–Ramond field breaking parity) would revive a linear contribution and spoil the quaternionic orthogonality property exploited in Section 4, Section 5 and

Section 6. This highlights the

uniqueness of the two–parameter deformation (

) within the DBI first–principle set–up.

Appendix B. Proofs of PT–Invariance and Pseudo-Hermiticity

This appendix supplies the algebraic details omitted in

Section 5. We show that

- (a)

the quaternion–valued metric

in Equation (

16) is invariant under the combined parity–time operation

;

- (b)

the enlarged Clifford generators

in Equation (

17) transform covariantly under

;

- (c)

the Dirac operator

D of Equation (

25) is simultaneously

–invariant and

pseudo-Hermitian, i.e.

with

.

Appendix B.1. Minimal P and T Prescriptions

Throughout we work in flat Minkowski conventions

and fix the imaginary quaternion basis

with

and

. The

minimal and

actions are

where

is

anti-linear6. The composite

is therefore anti-linear and leaves

unchanged:

.

Appendix B.2. Invariance of the Quaternionic Metric

Recall the linear quaternionic deformation

with

and

. Using (

A4):

Hence

proving Equation (

18) of the main text.

Appendix B.3. Covariance of the Extended Clifford Algebra

The generators

and

(

), with

, obey

. Because (i)

, (ii)

, and (iii)

are

–even, one finds

Thus the full algebra is –covariant.

Appendix B.4. Pseudo-Hermiticity of the Dirac Operator

Let

(

). For the quaternionic Dirac operator

metric compatibility implies

. Using

one obtains

establishing pseudo-Hermiticity. Because

commutes with

, adding the stochastic anti-Hermitian

of

Section 8 leaves (

A7) intact.

Appendix B.5. PT-Invariance of the Dirac operator

Applying (

A6) and noting

with

, one finds

Therefore

D is both

–invariant and pseudo-Hermitian, so its eigenvalues are real or appear in complex-conjugate pairs, as required for the heat-kernel expansion in

Section 6.

Summary

The minimal prescriptions (

A4) render the quaternionic metric, the extended Clifford algebra, and the Dirac operator strictly

–invariant.

With the Dirac operator satisfies , hence is pseudo-Hermitian.

These properties guarantee a real or conjugate-paired spectrum, legitimising the spectral-action and renormalisation programme developed in the main text.

Appendix C. Heat–Kernel Coefficient Derivations

This appendix supplies the technical steps behind the coefficients

and

used in

Section 6.

7

Notation.

We retain explicitly only

linear terms in the SU(2) activation parameters

introduced in Equation (

16); quadratic pieces first contribute to

. The

–even projector

defined in

Appendix E is tacitly applied whenever a “linear–quaternion slice’’ is mentioned.

Appendix C.1. Laplace form of D 2

For the

–invariant Dirac operator

built from the quaternionic metric

of Equation (

16), one may rewrite

where

is the Ricci scalar of

, and

Appendix C.2. Seeley–DeWitt Master Formulas

For a Laplace–type operator of the form (

A8) on a smooth four-manifold

without boundary the first two coefficients are

The total trace factorises as ; recall and .

Appendix C.3. Evaluation of a 0

Since

and

,

i.e. only the usual cosmological constant term survives; there is no linear quaternion contribution, in agreement with

Section 6.

Appendix C.4. Evaluation of a 2

Curvature part.

At one finds because . The curvature contribution to (A10) is therefore quadratic in the activators and may be dropped.

Endomorphism part.

A direct contraction at linear order gives

Using

and keeping

only the linear quaternion slice (see

Appendix E) one obtains

Inserting into (A10) yields

Equation (

A11) is precisely the result quoted in

Section 6: only the

time-like spring and the

spatial vortex survive after the internal trace at leading order.

Appendix C.5. PT Covariance

Both

and

are individually

–even (

Appendix B); hence the integrated quantity

is

–invariant. This guarantees that the effective Lagrangian derived in

Section 6.3 respects the global symmetry of the model.

Cross–Check: Scalar Slice of a 2

The scalar (0th-quaternion) component of

E is proportional to

or

, both of which vanish identically; therefore

. This validates the split between the “scalar’’ and “activator’’ sectors in

Section 6.

Appendix D. Influence Functional Integrals

This appendix derives the Gaussian influence functional quoted in

Section 8, culminating in the

cumulant step–down rule that shifts each heat–kernel coefficient

into

. Throughout we keep only leading terms in the small activation parameters

and in the bath–system coupling

.

8

Appendix D.1. System–Bath Decomposition

We split the Type–IIB world–sheet fields as in Equation (

45):

The total action separates into

The bath couples to the fermions through

where

is linear in the fast fluctuations

and

labels the extended Clifford basis of Equation (

17).

Appendix D.2. Bath Integration

Assuming the fast sector is in a Gaussian state

at the coarse–graining scale

, the

influence functional becomes

where all odd moments vanish and

Rotational symmetry of the bath.

Because the fast bath is generated by small fluctuations around a flat D3–brane, the correlator depends only on

and is diagonal in the internal quaternion indices:

The dimensionless strength is extracted by matching to the microscopic two–point function of .

Appendix D.3. Hubbard–Stratonovich Representation

The quartic term in (

A13) is linearised via an auxiliary,

anti–Hermitian matrix field

:

Because

,

can be expanded on the same Clifford basis. Identifying

the fermionic path integral becomes

Gaussian:

Appendix D.4. Statistics of δD

Integrating out

with the Gaussian weight in (

A14) yields

9

reproducing Equation (

50) of the main text. The stochastic process lives entirely in the two

-even quaternion directions and is white up to the cut–off

.

Appendix D.5. Cumulant Expansion and Step–Down Rule

Expanding the fermionic determinant in (

A15) around

:

Because

, the

first non–trivial contribution arises at quadratic order and shifts the heat–kernel coefficients according to

which is Equation (

51) of

Section 8. Equation (

A18) justifies the hierarchy employed in

Section 6: every deterministic coefficient

feeds a

stochastic correction to

, suppressed by

.

PT Covariance of the Noise

Because the kernel

is real and even, and

are

-even (

Appendix B), the distribution () is

-

covariant:

Thus the open metric remains -invariant at the stochastic level, preserving pseudo–Hermiticity order by order in the cumulant expansion.

Appendix E. Quaternion Projection Algebra

This appendix collects the algebraic identities that justify the

linear-quaternion projector introduced in Equation (

A22) and used throughout Section 6–7.3. All results hold at

and assume the standard quaternion basis

with

(

).

Appendix E.1. Internal Trace and Orthogonality

The Clifford–quaternion Hilbert space factorises as

so that any operator

acting on

decomposes as

The

internal trace

acts only on the quaternion factor:

Hence the orthogonality relations

provide the metric on quaternion space.

Appendix E.2. Definition of the Projector

Given (

A19) the

linear-quaternion slice is

i.e. we retain only the components along

and

, which are selected by the physical background (cf. Equation (

4)). The projector

acts as

With (

A20) one checks explicitly

Appendix E.3. Commutation with PT

Using the transformation rules in

Appendix B, both

and

are

-even, while

is

-odd. Therefore, for any operator

,

i.e.

commutes with the global symmetry and does

not spoil pseudo-Hermiticity.

Appendix E.4. Quadratic Identities

When evaluating heat–kernel densities and Noether currents one often encounters products such as

. Using (

A21) and the quaternion algebra:

from which three important facts follow:

- (i)

The scalar component (proportional to ) never contributes to the slice: it disappears after the projection and hence cannot spoil current conservation.

- (ii)

The component is -odd and is therefore eliminated whenever the integrand is constrained to be -even (e.g. in the heat–kernel densities).

- (iii)

As a result, products of two linear-quaternion operators do not re–enter the sector—an algebraic reason why a single counter-term suffices to cancel the anomaly at all loops (Section 7).

Appendix E.5. Trace Identities for Heat–Kernel Coefficients

Let

denote the background Dirac operator and

,

the endomorphism and curvature defined in

Appendix C. Using (

A22) one proves the selection rule

Consequently

while

due to the mixed

structures. Equation (

A25) provides the algebraic underpinning of the detailed calculation in

Appendix C.

Synopsis

The projector isolates the -even, linear quaternion subspace singled out by the D3–brane background.

Products of operators do not regenerate terms, explaining why a single counter-term cancels the anomaly to all perturbative orders.

Internal traces kill any potential mixing between the quaternionic directions and the scalar sector up to , thus preserving both pseudo-Hermiticity and renormalisability.

These identities are repeatedly used—often implicitly—in

Section 6 and Section 7 to streamline algebraic manipulations and to demonstrate the minimality of the renormalisation scheme.

Appendix F. Renormalisation Constants and β–Functions

This appendix complements Section 7 by giving the explicit one–loop renormalisation constants, the associated –functions, and a compact proof that the linear–quaternion counter–term is scheme–independent at this order.

Appendix F.1. Notation and Renormalisation Scheme

We employ dimensional regularisation in

and adopt the

MS subtraction convention. The bare (

B) and renormalised (

R) quantities are related by

where the

Z–factors are expanded as

. All loop integrals are evaluated with the

–

even projector

implicit.

Appendix F.2. Decomposition of the Divergent Action

The one–loop effective action can be written as

with

the Seeley–DeWitt densities of

Appendix C. Splitting

into its

scalar and

linear–quaternion parts,

the divergent Lagrangian reads

Appendix F.3. Renormalisation Constants

Scalar sector.

Matching (

A28) with the tree–level coefficients fixes

The explicit values follow from the standard heat–kernel trace.

Linear–quaternion sector.

Demanding the cancellation of

gives the

unique solution

All remaining Z–factors coincide with their scalar counterparts, i.e. there is no extra renormalisation of the quaternion axes .

Appendix F.4. One–Loop β–Functions

The renormalised couplings run according to

From (

A29)–(

A30) we obtain

where

denotes the running of the

–even linear–quaternion strength

. Equation () confirms the decoupling of the quaternionic sector claimed in Section 7.

Appendix F.5. Scheme Independence of β 4

Because

is the

only divergent operator carrying a linear quaternion index, any admissible subtraction scheme satisfies

A finite change of scheme,

shifts

but the requirement of exact Noether conservation (

Section 6) forces the coefficient back to unity. Hence

Summary

The scalar couplings

and the string coupling

renormalise in the standard way; their

–functions are given by Equation (

A31).

The quaternionic sector requires

exactly one divergent coefficient,

, cf. (

A30). This fixes the counter–term

and guarantees anomaly cancellation.

The linear–quaternion coupling does

not run at one loop,

, reflecting the algebraic identity (

A24).

The value

is independent of the subtraction scheme, see (

A33); therefore the cancellation mechanism is universal within the effective-field-theory domain

.

Appendix G. Symbol Glossary

This glossary gathers all frequently–used symbols into a single, alphabetically ordered list. Each entry specifies the quantity, its physical meaning, mass dimension

10, and its behaviour under the global

transformation of

Appendix B. Curved indices

carry mass dimension

; internal quaternion indices

are dimensionless.

| Symbol |

Meaning / Definition |

Dim. |

|

|

Seeley–DeWitt densities of

|

|

+ |

|

Linear–quaternion slice of

|

|

+ |

|

World–volume gauge field |

1 |

− |

|

Regge slope () |

|

+ |

|

Background NS–NS two–form |

0 |

+ |

|

Monopole strength in

|

0 |

+ |

|

Cut–off profile in the spectral action |

0 |

+ |

|

One–loop coefficients / renormalisation constants |

0 |

+ |

| D |

Full Dirac operator () |

1 |

+ |

|

Background Dirac operator (no noise) |

1 |

+ |

|

Stochastic correction (Appendix D) |

1 |

+ |

|

Quaternion basis

|

0 |

|

|

Temporal activator amplitude |

0 |

+ |

|

Radial activator amplitude |

0 |

+ |

|

―― “spring” |

0 |

+ |

|

―― “vortex” |

0 |

+ |

|

Krein metric () |

0 |

+ |

|

Spectral–action couplings |

|

+ |

|

Flat–space Dirac matrices |

1 |

− |

|

Enlarged Clifford generators (see Equation (17)) |

1 |

− |

|

Closed–string (bulk) metric |

0 |

+ |

|

Open–string metric (see Equation (7)) |

0 |

+ |

|

Open–string coupling |

0 |

+ |

|

Quaternionic Noether currents |

3 |

+ |

|

Noise kernel (see Equation (48)) |

|

+ |

|

Spectral UV cut–off |

1 |

+ |

|

Coarse–graining scale in influence functional |

1 |

+ |

|

Spin–connection “field strength” |

2 |

+ |

|

Endomorphism in decomposition |

2 |

+ |

|

Combined parity–time operator |

0 |

— |

|

Pauli matrices (internal ) |

0 |

+ |

|

Spectral action |

0 |

+ |

|

Linear–quaternion source term (see Equation (38)) |

4 |

+ |

|

Non–commutativity tensor |

|

+ |

|

Oscillation frequency of

|

1 |

+ |

Legend. “Dim.” denotes canonical mass dimension in natural units. The “

” column shows each symbol’s intrinsic behavior under the global

prescription of

Table 1: + (even), − (odd), or “—” if the entry is itself the transformation operator.

References

- J. Polchinski, String Theory, Vols. I–II, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- A. Connes, Noncommutative Geometry, Academic Press, 1994.

- A. H. Chamseddine and A. Connes, “The Spectral Action Principle,” Commun. Math. Phys. 186 (1997) 731, arXiv:hep-th/9606001.

- N. Seiberg and E. Witten, “String Theory and Noncommutative Geometry,” JHEP 9909 (1999) 032, arXiv:hep-th/9908142.

- C. M. Bender, “Making Sense of Non-Hermitian Hamiltonians,” Rept. Prog. Phys. 70 (2007) 947, arXiv:hep-th/0703096.

- Mostafazadeh, “Pseudo-Hermitian Representation of Quantum Mechanics,” Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys. 7 (2010) 1191, arXiv:0810.5643 [math-ph].

- D. V. Vassilevich, “Heat Kernel Expansion: User’s Manual,” Phys. Rept. 388 (2003) 279, arXiv:hep-th/0306138.

- P. B. Gilkey, “The Spectral Geometry of a Riemannian Manifold,” J. Differential Geometry 10 (1975) 601.

- R. T. Seeley, “Complex Powers of an Elliptic Operator,” in Proc. Sympos. Pure Math. Vol. 10 (1967) 288.

- B. S. DeWitt, Dynamical Theory of Groups and Fields, Gordon and Breach, 1965.

- J. C. Collins, Renormalization, Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Planck Collaboration (N. Aghanim et al.), “Planck 2018 Results. VI. Cosmological Parameters,” Astron. Astrophys. 641 (2020) A6, arXiv:1807.06209 [astro-ph.CO].

- MAGIS Collaboration (M. A. Kasevich et al.), “Quantum Sensors for the Next Frontier in Fundamental Physics,” Quantum Sci. Technol. 6 (2021) 024009, arXiv:2103.12057 [quant-ph].

- M. Maggiore et al. [Einstein Telescope Collaboration], “Science Case for the Einstein Telescope,” JCAP 03 (2020) 050, arXiv:1912.02622 [astro-ph.CO].

- J. F. Navarro, C. S. J. F. Navarro, C. S. Frenk and S. D. M. White, “A Universal Density Profile from Hierarchical Clustering,” Astrophys. J. 490 (1997) 493, arXiv:astro-ph/9611107.

- R. P. Feynman and F. L. Vernon, “The Theory of a General Quantum System Interacting with a Linear Dissipative System,” Annals Phys. 24 (1963) 118. [CrossRef]

- E. Calzetta and B. L. Hu, “Nonequilibrium Quantum Fields: Closed-Time-Path Effective Action, Wigner Function, and Boltzmann Equation,” Phys. Rev. D 37 (1988) 2878. [CrossRef]

- N. Berline, E. Getzler and M. Vergne, Heat Kernels and Dirac Operators, Springer, 1992.

| 1 |

Here and project on the time and radial directions, respectively. |

| 2 |

and in our conventions; the dilaton is kept constant . |

| 3 |

The tensor product with the quaternionic identity is crucial: acts only on the spinor indices. |

| 4 |

Details of the curvature and endomorphism contractions are provided in Supplementary App. C of the source file. |

| 5 |

A rigorous proof would require a world–sheet analysis of open–string graphs with multiple B–field insertions and is left to future work. |

| 6 |

acts on all complex scalars by but leaves the quaternionic units inert; this is crucial for pseudo-Hermiticity. |

| 7 |

The density—which is needed only for the linear–quaternion counter–term of Section 7—is obtained with the standard formulas collected in [ 8, 18] and is therefore not reproduced here. |

| 8 |

A full non–linear treatment is possible with the closed–time–path formalism but is unnecessary for the one–loop consistency check performed in Section 7. |

| 9 |

Angular brackets denote averages over the auxiliary field. |

| 10 |

We use units in which . |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).