4.2.1. Reward Engineering

In this paper, a reward engineering approach is adopted to determine the reward function. The core of the reward function is centered around G from the Problem Formulation chapter. A total of three adjustments to the reward function were made, focusing on four aspects of flight procedure design: safety, economy, simplicity, and environmental friendliness. The five reward functions and their corresponding reward function curves are set as follows.

Reward function1:

The aim is to optimize the design of the flight procedure by balancing multiple objectives of safety, economy, simplicity, and noise reduction. Its mathematical expression is(

22):

1. Safety Reward ()

The safety component is defined as (

23):

where

represent state parameters, and

indicates the state variable.

to

contribute positively, while

and

contribute negatively.

2. Economic Reward ()

The economic component is represented as (

24):

where

is the total length of the flight procedure, and

is the distance from the starting point to the endpoint of the linear flight path.

3. Simplicity Reward ()

The simplicity component is defined as (

25):

In the previous definition (

15)

, is clearly defined.

4. Noise Reward ()

The noise reward component is expressed as (

26):

where

N (

27)is calculated based on the environmental model in the Problem Formulation section, ensuring that the reward function remains consistent throughout the noise reward.

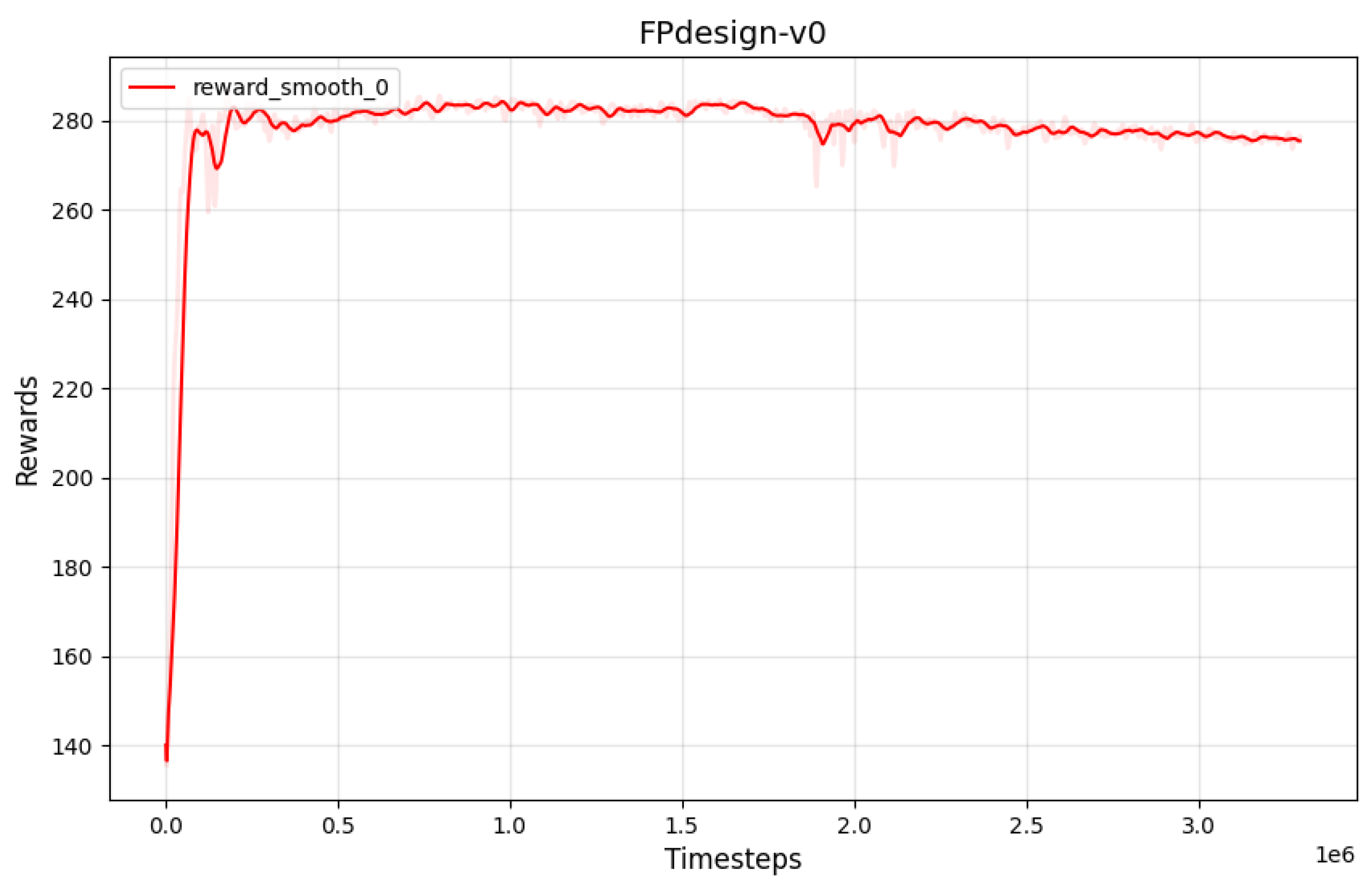

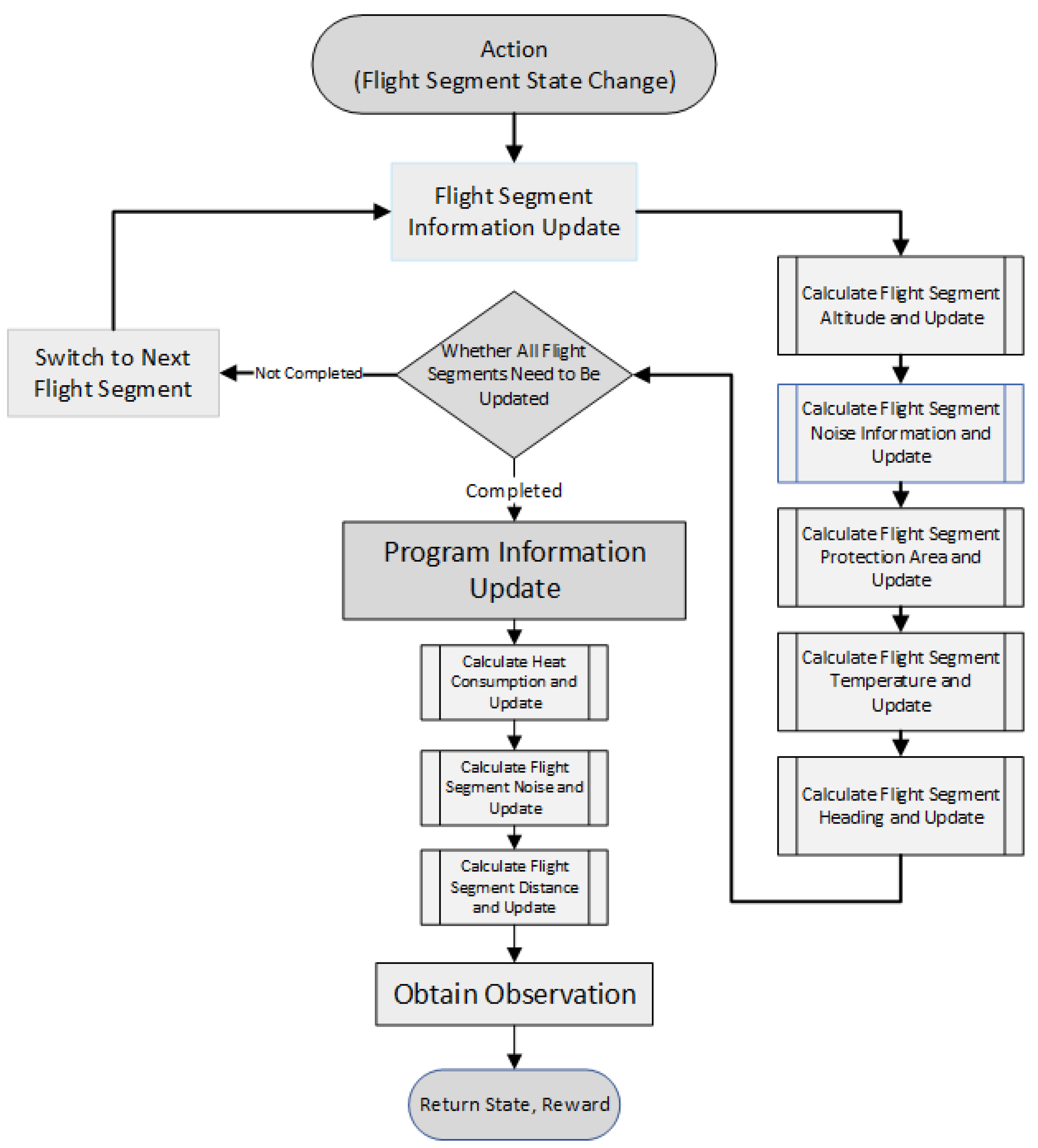

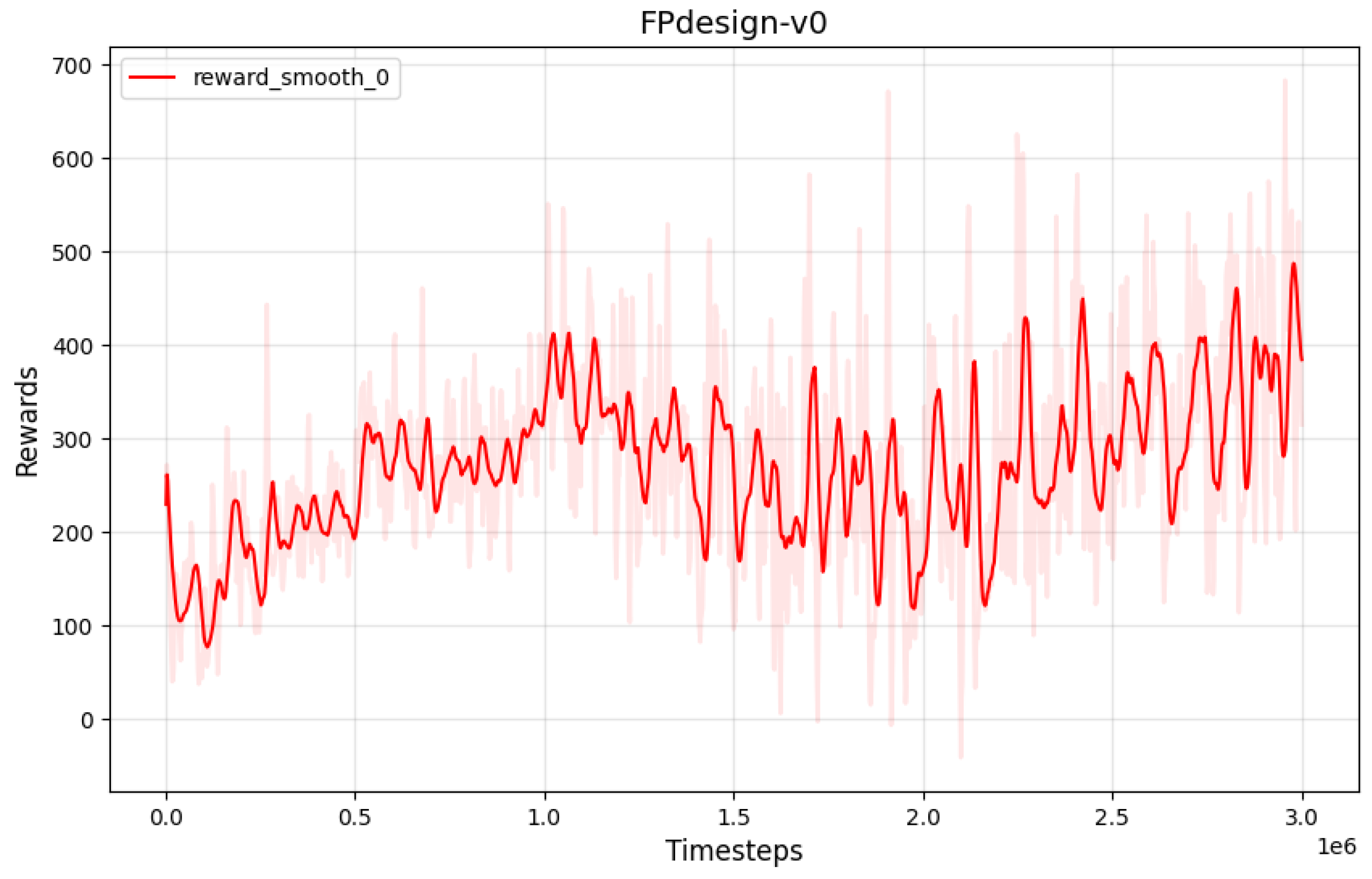

Based on the reward count obtained from the reward curve, as illustrated in the

Figure 7, it can be observed that the reward function exhibits a continuous variation. Furthermore, it has been trained over

iterations, indicating that the configuration of the reward function is not capable of completing the task requirements.

Reward function2:

The optimization objectives of the flight procedure have been further adjusted. Compared to the first version, the design has eliminated the economic objective and focuses on three aspects: safety, simplicity, and noise control. Additionally, the safety reward has been normalized, while the normalization setting for the simplicity reward has been removed. The mathematical expression of the reward function(

28) is as follows:

1. Safety Reward ()

The safety reward in the updated version is expressed as (

29):

where

represent positive safety factors (such as safety zone distances), and

represent negative risk factors (such as proximity to obstacles). The first version of the equation is

. In this version, a normalization factor of 4 has been introduced to process the safety components, allowing for a more refined evaluation of the reward based on minor variations in the parameters.

The simplicity reward is defined as (

30):

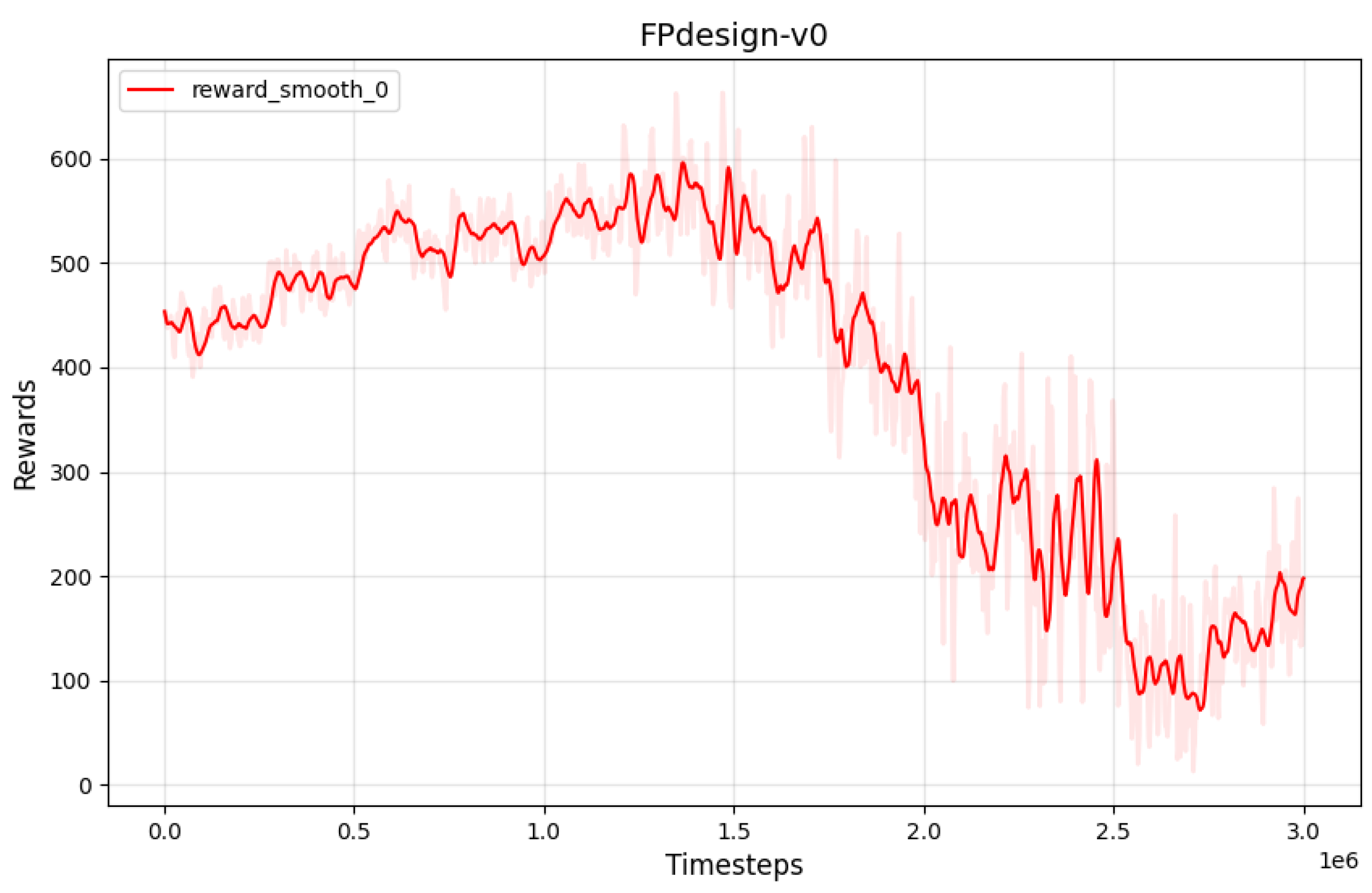

The reward function curve is as follows (

Figure 8), from which it can be seen that the initial stage high reward indicates that the strategy is well adapted to the environment, that the mid stage descent may be correlated with multiple objective conflicts, and that the late stage stabilization at a lower level implies that the strategy converges but does not achieve desired performance.

Reward Function 3:

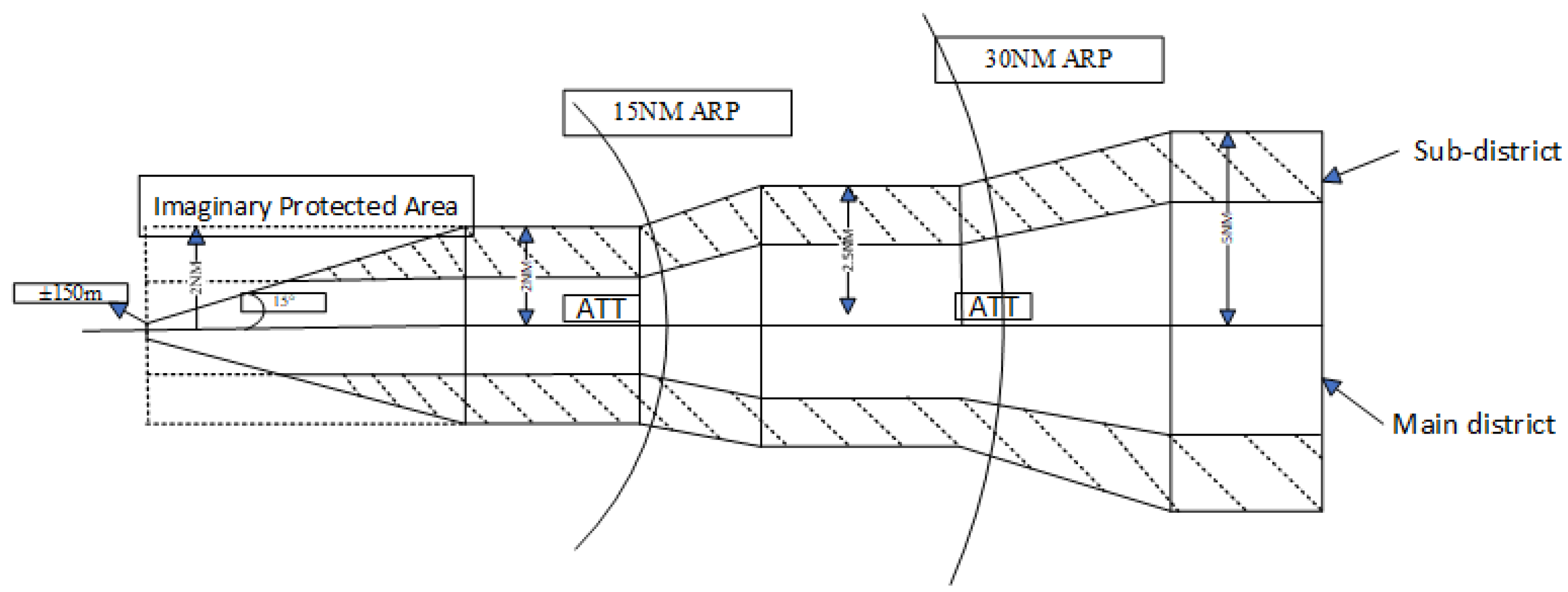

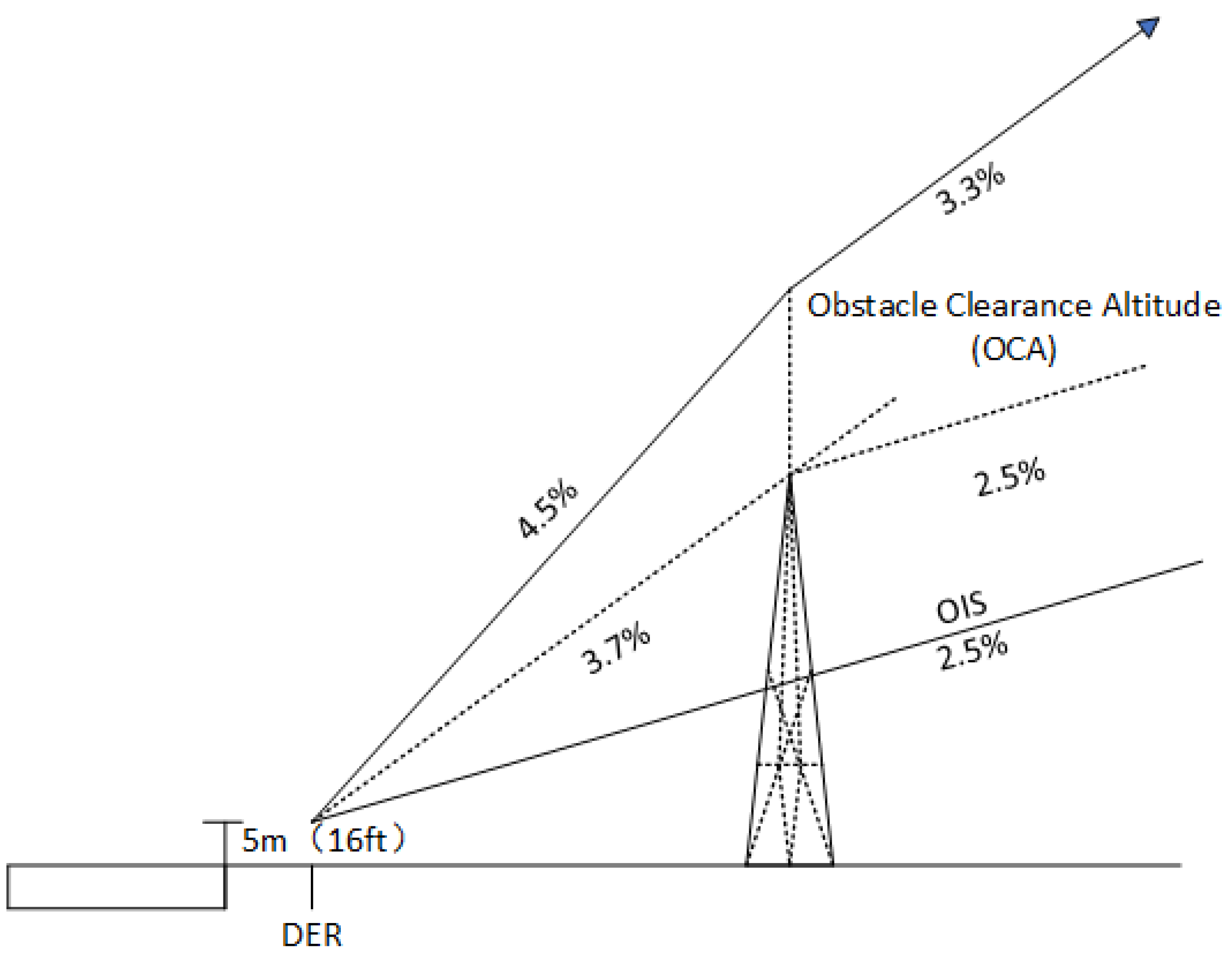

The third version of the reward function represents a significant improvement and expansion over the second version, aiming to optimize the performance of the flight procedure more comprehensively while enhancing adaptability to complex environmental constraints. The second version of the reward function primarily focused on three aspects: safety, simplicity, and noise control. In this version, the simplicity reward was calculated based on the turning angle, without differentiating between angle and distance simplicity, and it lacked a clear penalty for boundary violations. The third version refines the simplicity objectives by explicitly dividing them into angle simplicity and distance simplicity, optimizing for turning angles and segment distances, which significantly enhances the specificity and interpretability of the rewards. The specific settings are as follows:

The safety reward

is derived from Equation (

31), where

takes values between 0 and 1. The previous four states are related to flight disturbance information, with no reward values for obstacles;

and

represent the changes in the pitch and roll angles of the flight segment. If there are deviations in the pitch and roll angles, a penalty is applied.

The angle simplicity reward

is determined by the three angles affected by the current selected flight path, denoted as

. If and only if this turn angle is less than 120 degrees, is considered a straight departure procedure, thus the setting state value must be less than 0.66 to obtain the angle simplicity reward. The calculation method is given by Equation (

32), and the formula for the angle simplicity reward is expressed as:

The distance simplicity reward

is primarily determined by

,

, and

. Here, when the boundary flag for

is set to 1, the total value of the reward function is directly set to 0 as a maximum negative reward. When the boundary flag for

is 0, the calculated value of

is positive, thus the value for

is calculated as twice the value of

. Empirically, we aim to encourage the strategy to explore within a limited distance. If the state value

, which represents the total procedure length, is less than 0.3, an additional reward based on the state value

is added, as shown in Equation (

34).

The environmental reward

is derived from the negative reward of noise. It remains an empirical formula, calculated by dividing the total noise

N updated by the procedure by 10000, as shown in Equation (

35):

Thus, the classification of multi-objective optimization rewards is shown in

Table 5. Note that the relative weights of the rewards depend on the environment. The weights adjusted based on experimental data in this Lu Zhou departure procedure may not be applicable to other flight procedures. The total reward function in this experimental environment is derived from the sum of the safety reward, angle efficiency reward, distance efficiency reward, and environmental noise reward. The total reward function is given by equation (

36):

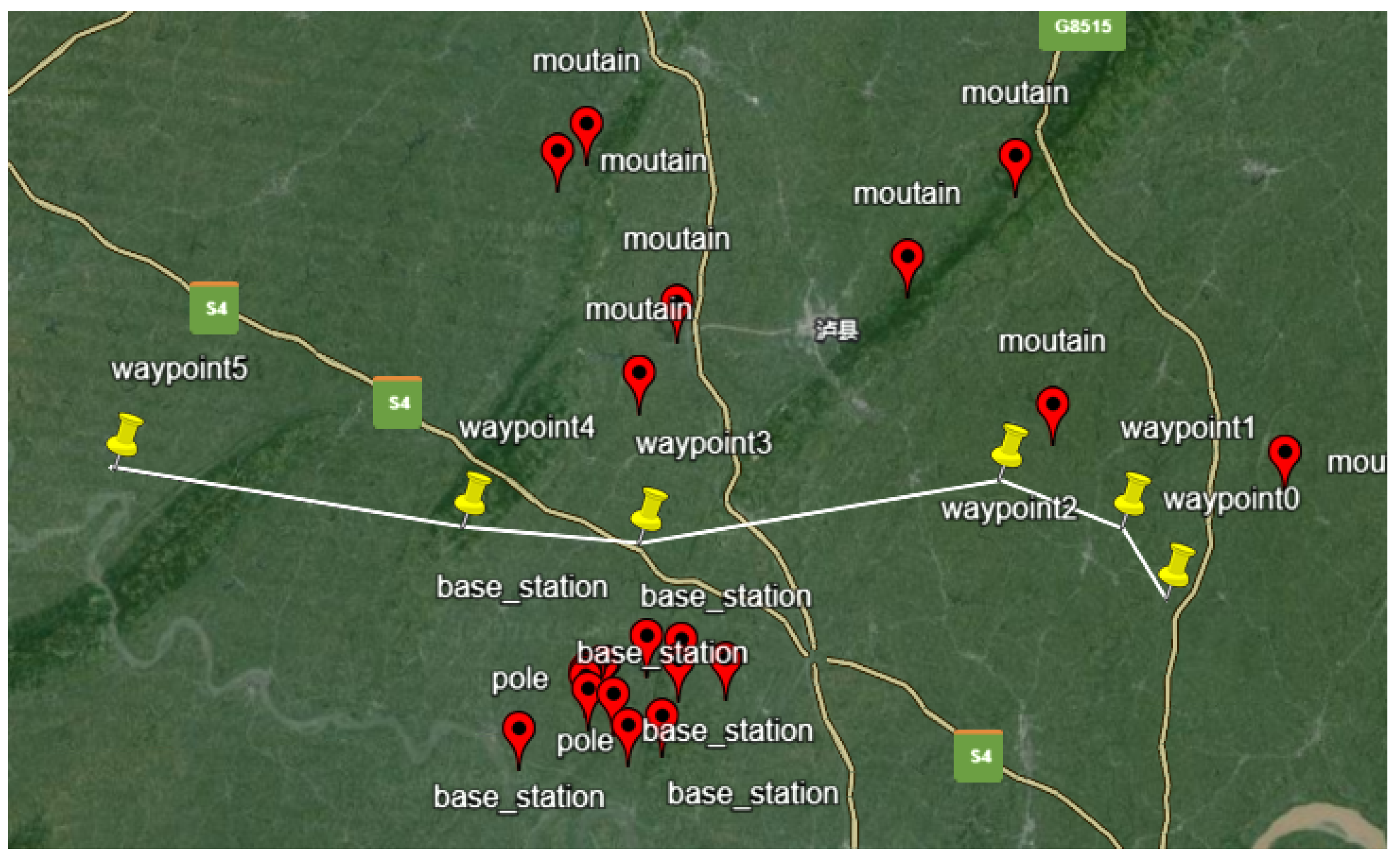

The reward function curve is shown below. From the figure, it can be seen that the reward function curve converges around 50,000. Observing the reward curve, it shows an overall upward trend and oscillates close to a certain peak value. The trend is positive, indicating that the model has learned a good strategy. Our algorithm and environmental adjustments can be considered complete. The model weights at 2,500,000 time steps were called for visualization, and the results are shown in

Figure 10.

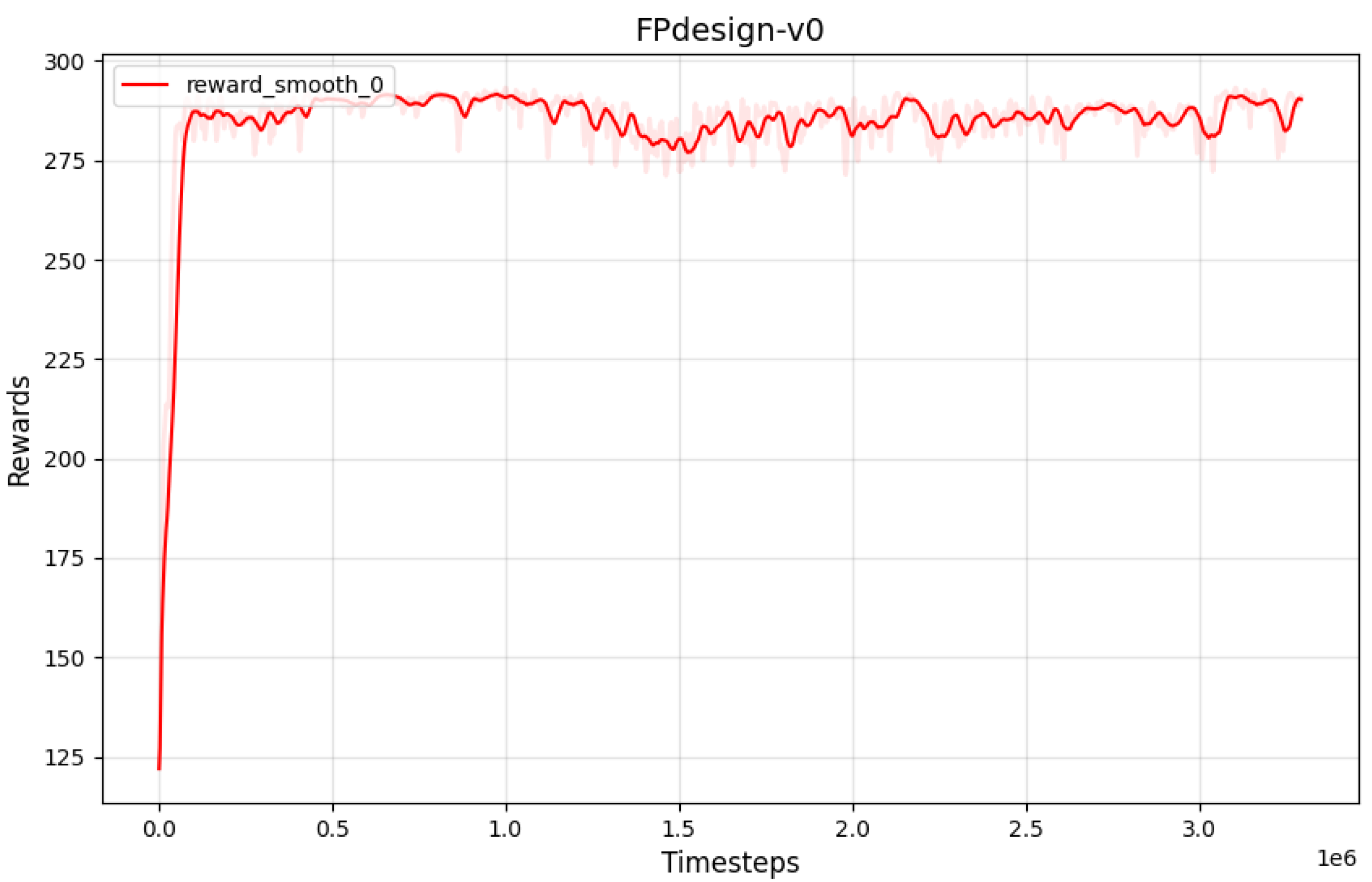

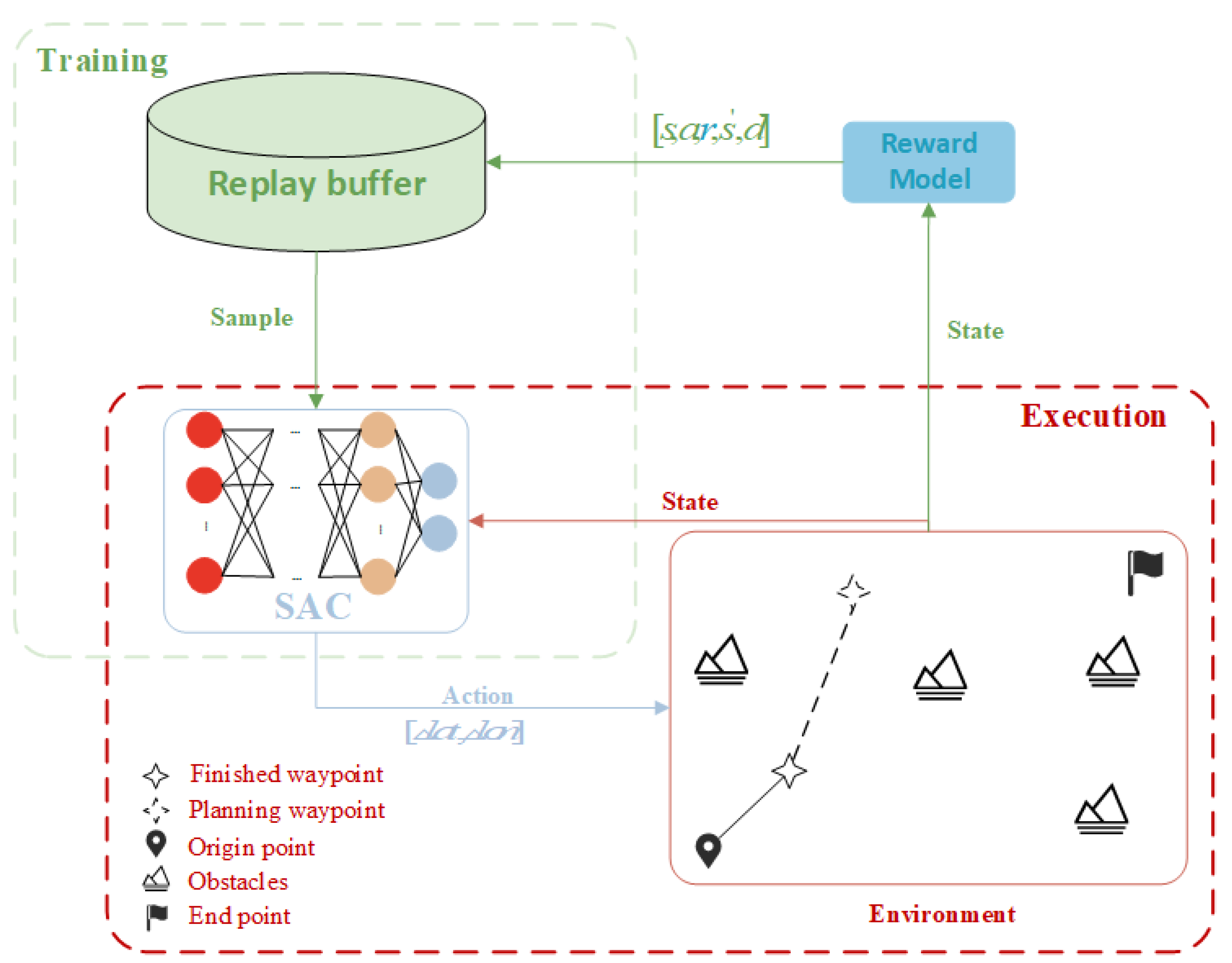

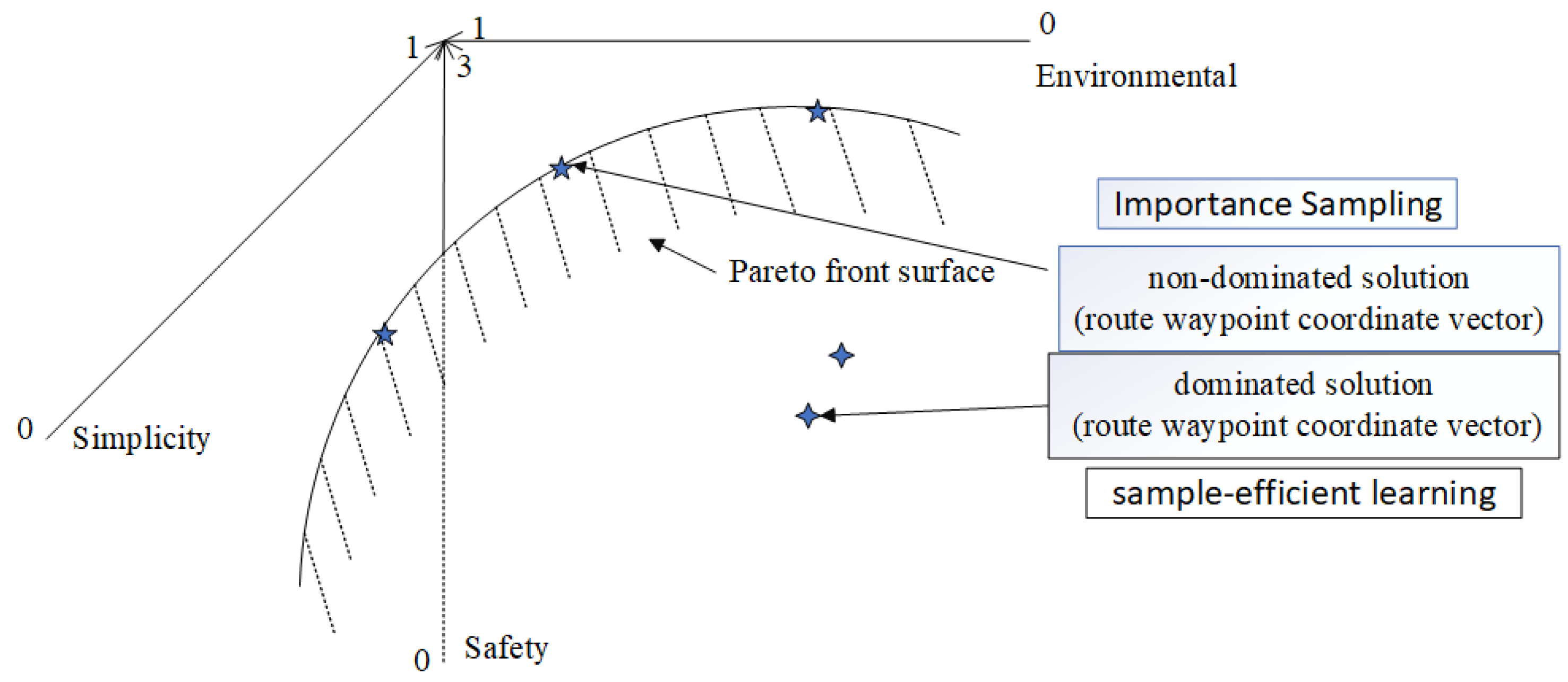

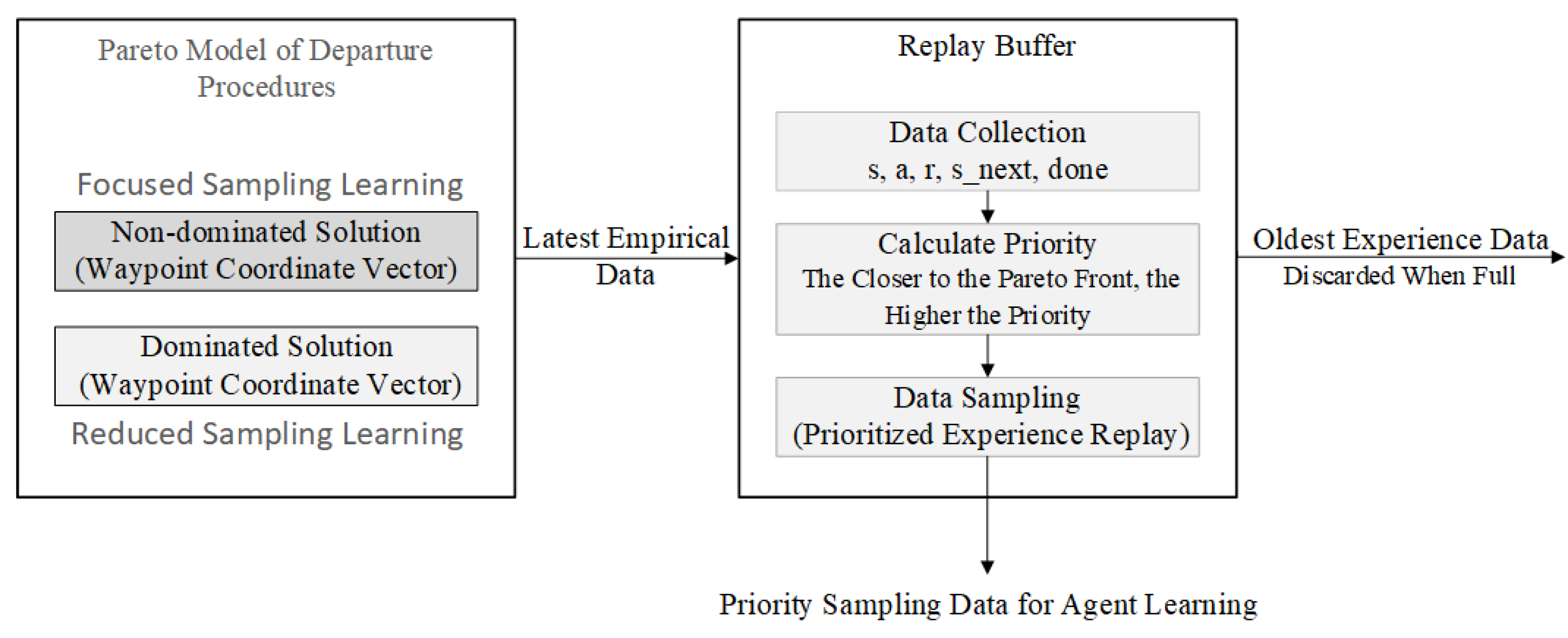

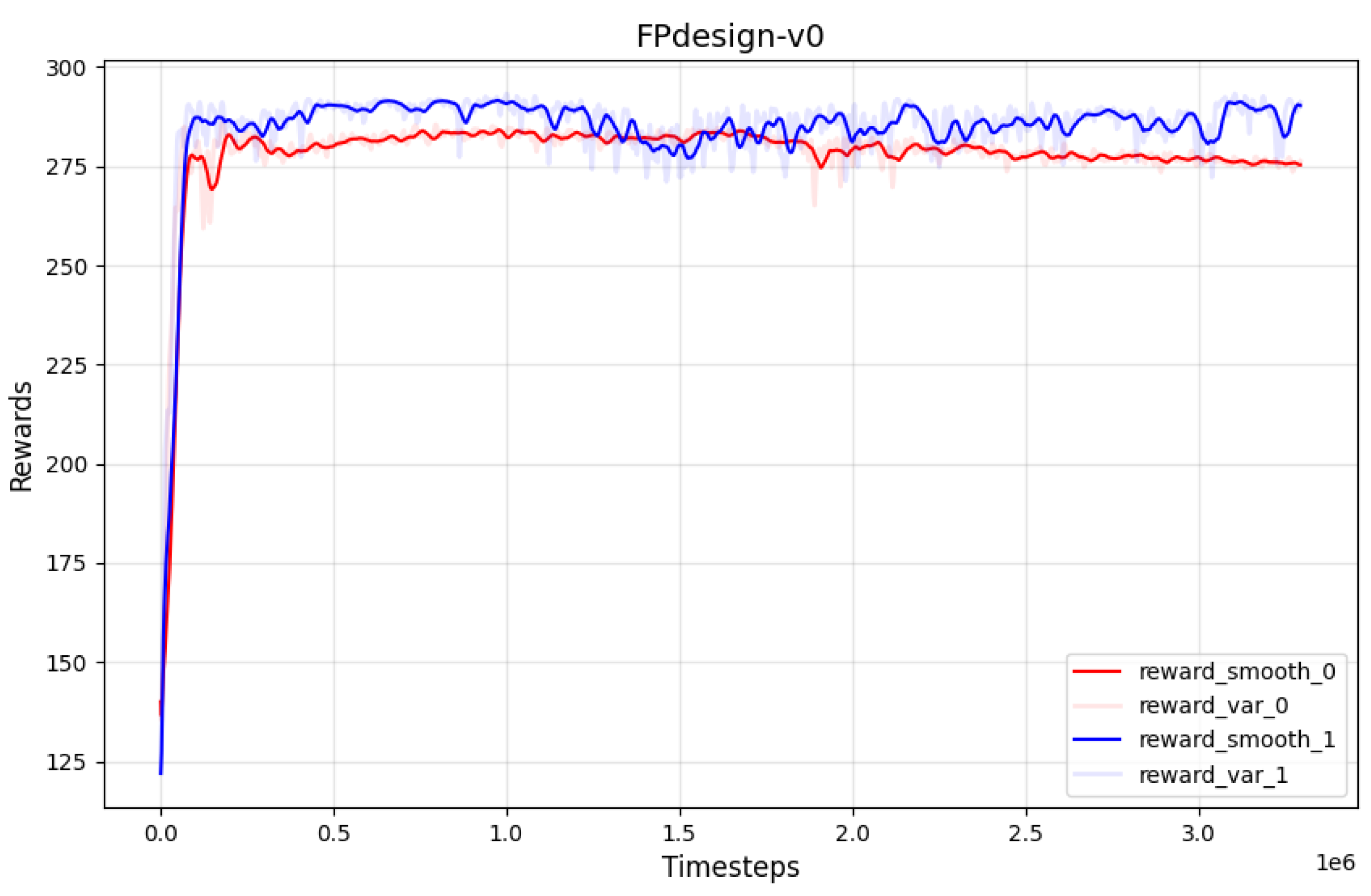

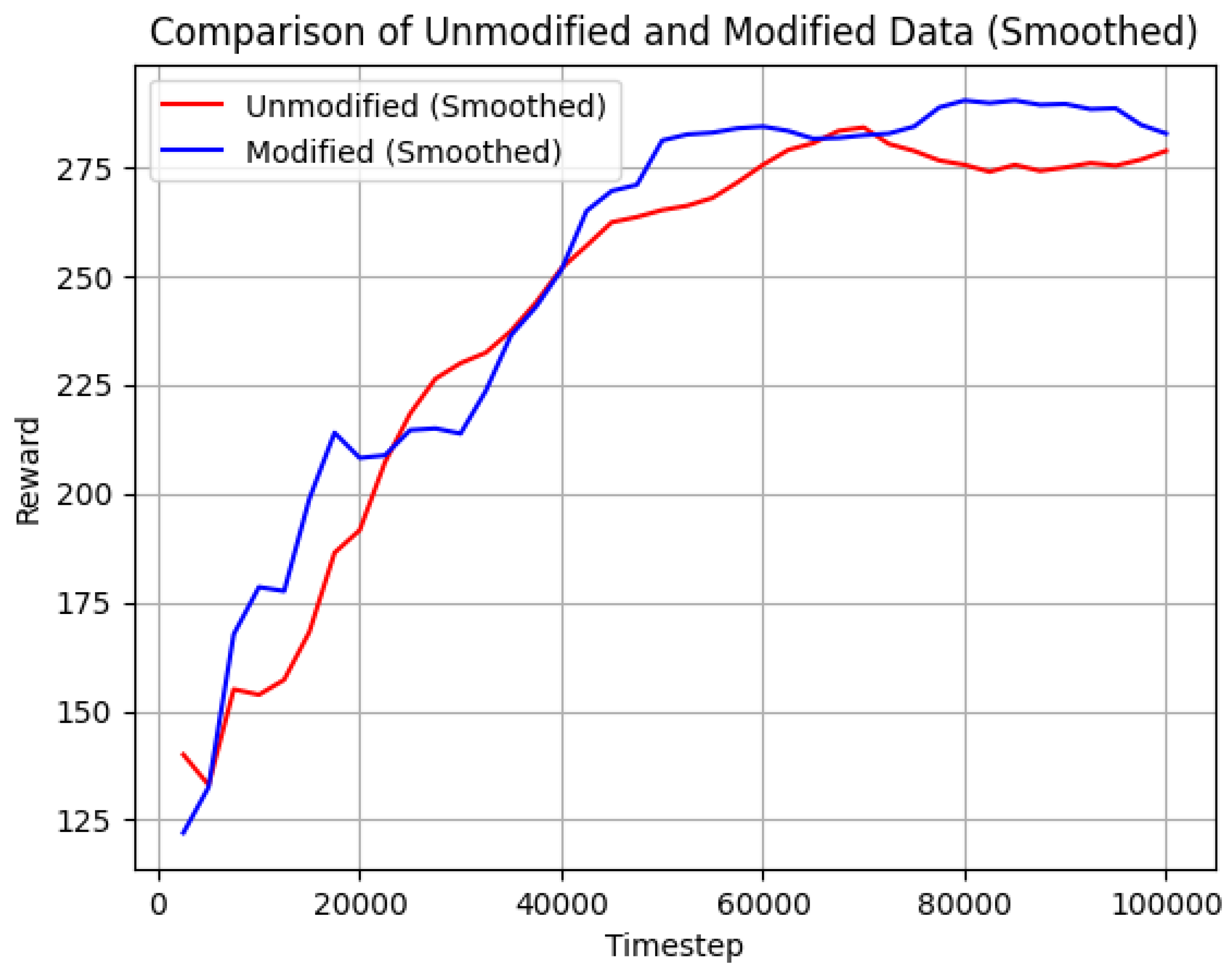

Priority-Based Replay Buffer Sampling

The experiment includes two comparison groups: one group applies the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) algorithm with an unmodified sampling mechanism, while the other group employs an improved Replay Buffer and dynamic learning rate adjustment within the SAC algorithm [

36]. The convergence curve of the original SAC reward is shown in

Figure 9, while the reward curve of the SAC with the improved Replay Buffer and dynamic learning rate adjustment is shown in

Figure 11. The reward curve of the improved SAC converges in a very short number of time steps and does not exhibit the slight decline in peak values observed in the later training stages of the original SAC algorithm. Additionally, the use of dynamic learning rate adjustment helps to keep the variance of the reward curve within a reasonable range.

Figure 9.

Original SAC Reward Curve Chart

Figure 9.

Original SAC Reward Curve Chart

Figure 10.

procedure Visualization

Figure 10.

procedure Visualization

Figure 11.

Improved SAC Reward Curve Chart

Figure 11.

Improved SAC Reward Curve Chart

By comparing the convergence curves of the reward functions for both algorithms, the results are shown in

Figure 12. The analysis reveals that the convergence speeds of the two reward function curves are similar. The reward curve obtained from the improved algorithm has peak values during the convergence process that are closer to the theoretically optimal strategy. Although this method results in an increase in the variance of the reward curve, the strategy of dynamically adjusting the learning rate successfully maintains it within an acceptable range.

From the visualization results in

Figure 14, it can be observed that the improved SAC algorithm demonstrates more significant effects in terms of optimization speed and results. This indicates the effectiveness of scalarization of the reward function in multi-objective optimization and proves the efficacy of the Pareto optimal prioritized experience replay sampling strategy in enhancing algorithm performance. Through experimental evaluation, the average score of the improved SAC reward demonstrates a 4% increase compared to the original SAC reward, as illustrated in the

Table 6 below. Furthermore, the optimization speed of the improved method is 28.6% faster than that of the original approach. As shown in the

Figure 13.

Verification of Flight Procedures Based on BlueSky

To ensure that the procedure demonstrates rationality and effectiveness under simulated real flight conditions, it is necessary to validate the flight procedure optimized by the reinforcement learning algorithm. If the procedure performs poorly in specific scenarios during the validation phase, it must be returned to the design stage for detailed adjustments until the performance of the flight procedure meets the expected standards.

This paper uses BlueSky as the validation platform for the flight procedure. BlueSky is an open-source flight simulation platform that provides a flexible and extensible environment for testing and validating various flight procedures [

37].

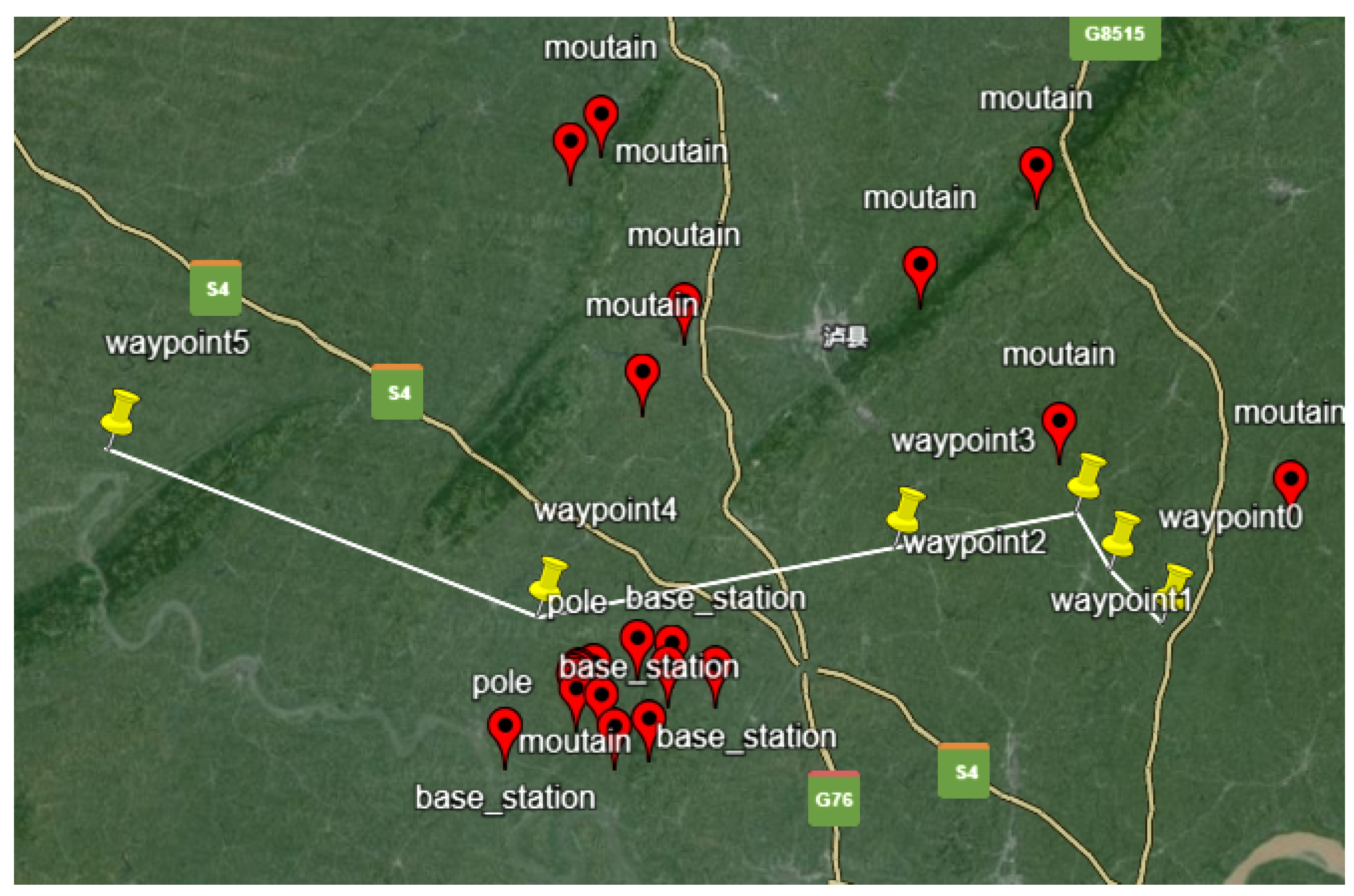

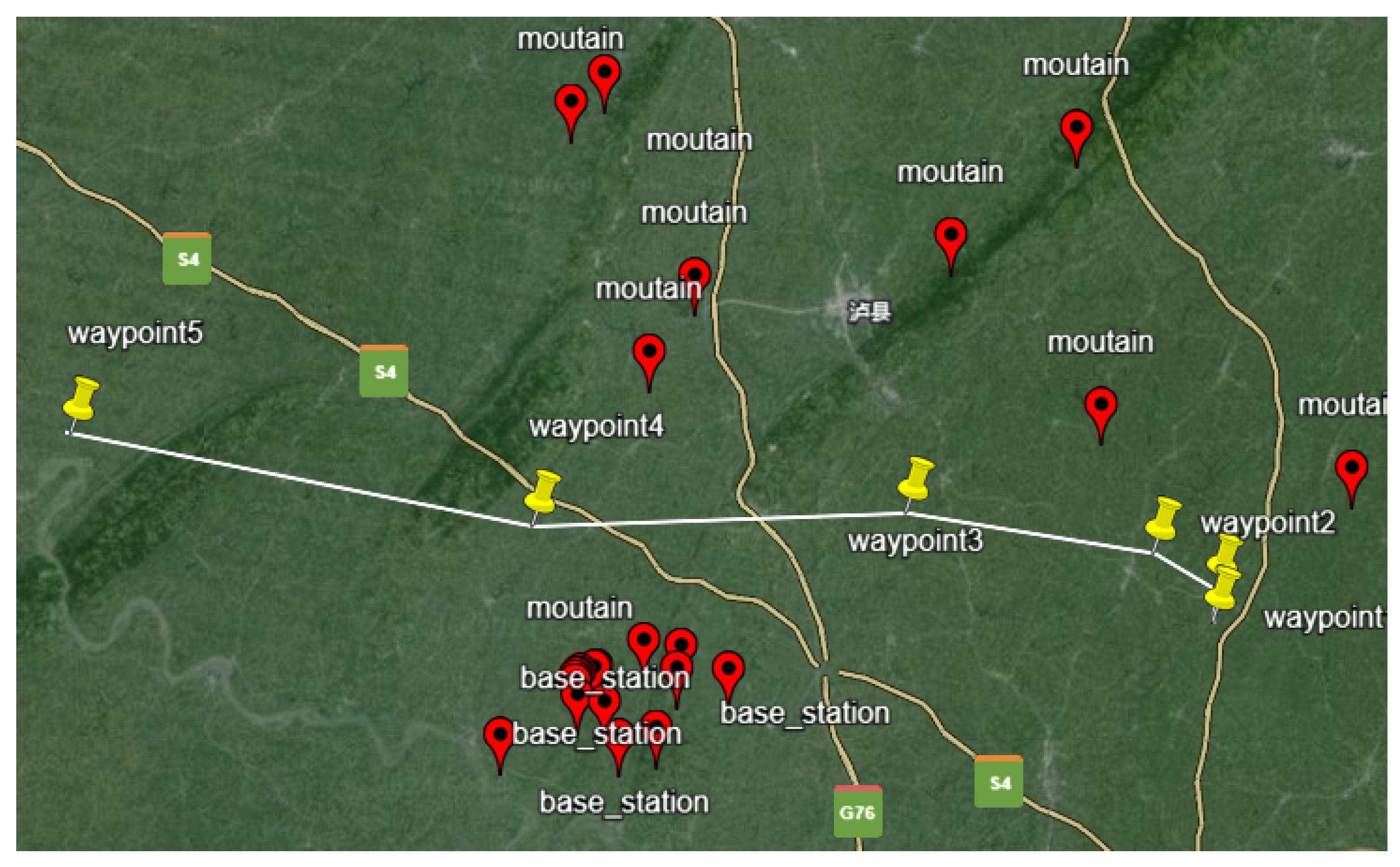

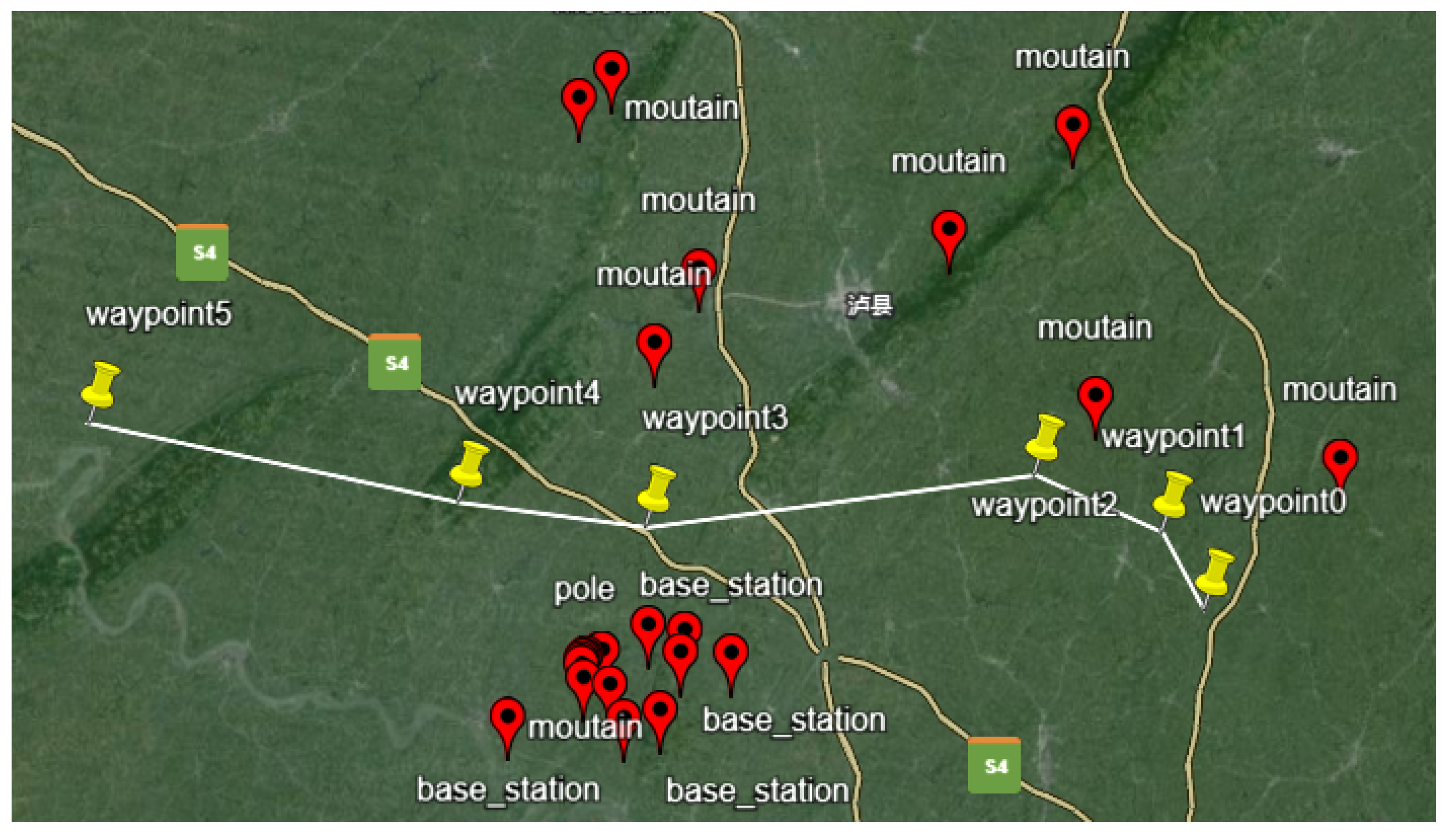

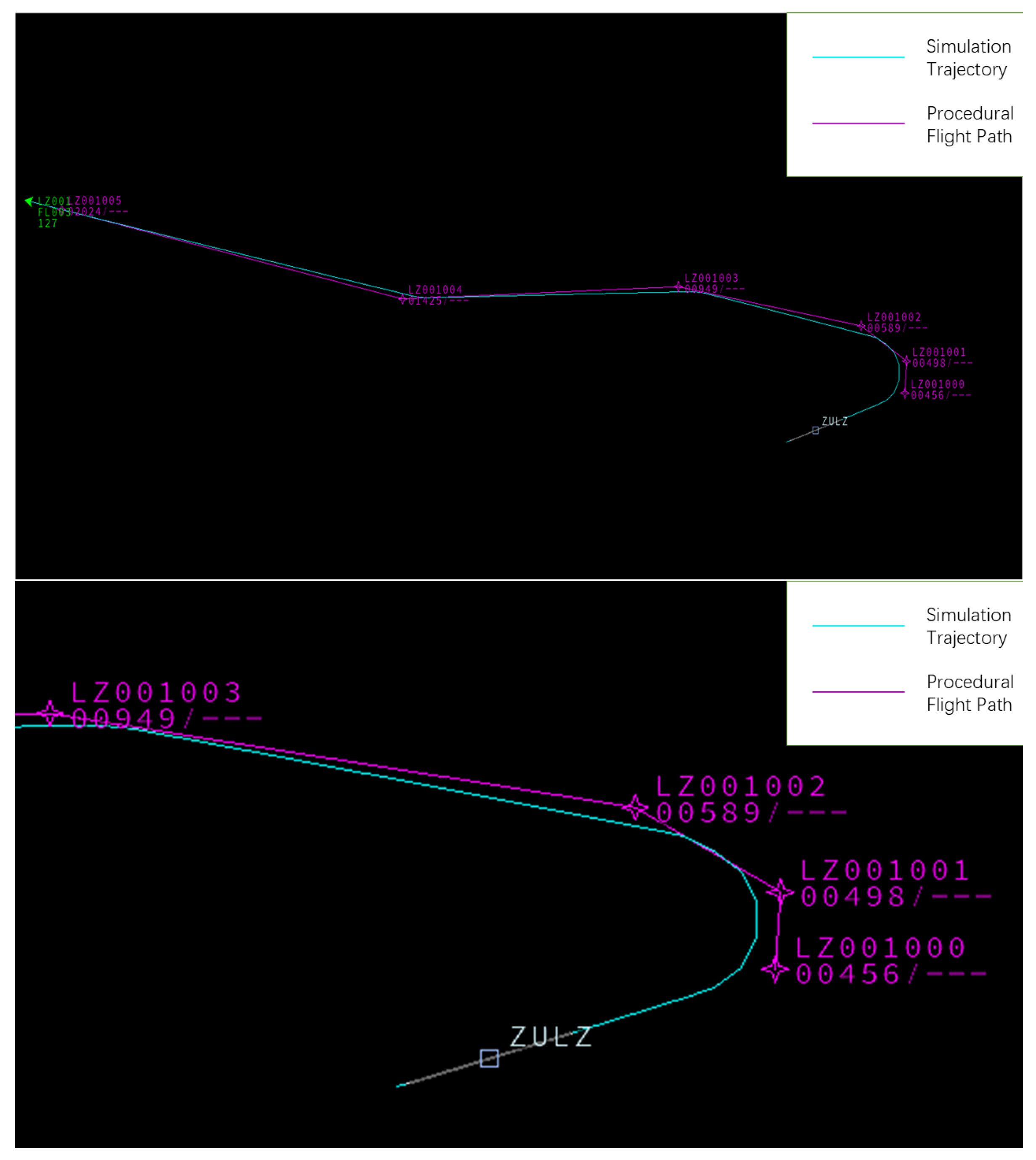

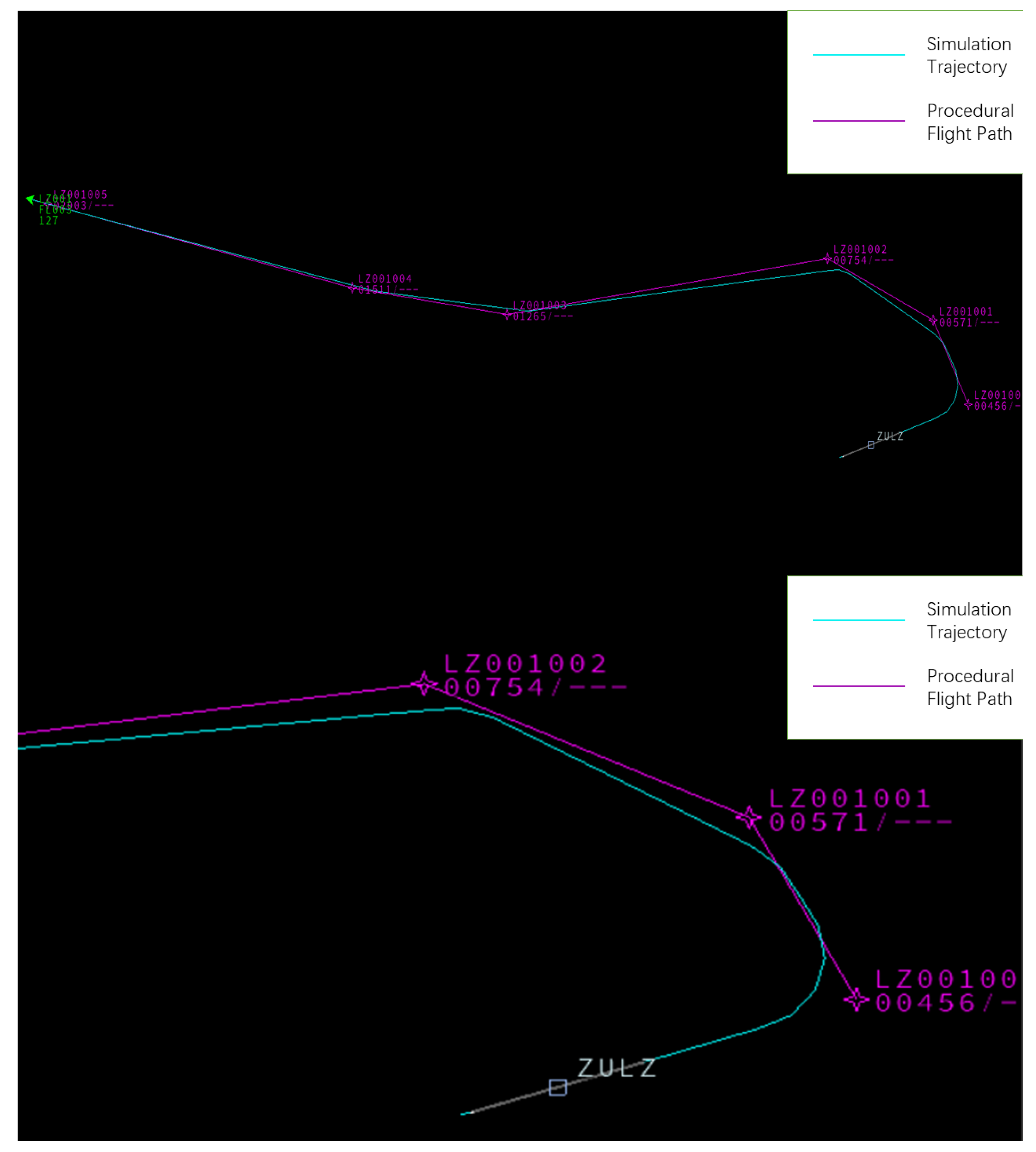

Validating the flight procedure using BlueSky requires the creation of scenario scheme files. Next, two flight procedures optimized through multi-objective reinforcement learning are randomly selected, as shown in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

Figure 17 shows the comparison for Verification procedure 1, while

Figure 18 shows the comparison for Verification procedure 2. Since the initial phase of departure is the most critical and has the lowest overlap with the simulation trajectory, this section has been enlarged for observation. By analyzing the simulated flight trajectory in conjunction with the predefined procedure trajectory, the reasonableness of the trajectory settings, protected area settings, and climb gradient is assessed based on safety, simplicity, and environmental considerations, indicating that the designed flight procedure is feasible [

38].