1. Introduction

With the rapid integration of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) into real-world operations, their roles have expanded from agriculture and logistics to time-critical disaster response and persistent environmental monitoring. In particular,

urban and built-up environments—characterized by dense buildings, occlusions, and narrow corridors—are becoming key application theaters for UAV swarms, e.g., communication relaying in “urban canyons,” cooperative searching among high-rises, and safe navigation through cluttered streets and courtyards [

1,

2,

3]. While multi-UAV formation can substantially enhance area coverage and resilience, achieving

stable, adaptive, and collision-free coordination in these city-like scenarios remains challenging.

As the team size grows, multi-UAV control faces intertwined difficulties in perception, decision-making, and real-time execution. Concretely, we highlight three practical challenges.

(1) Selective information use under partial observability. Each UAV must filter high-dimensional, multi-source inputs (self state, neighbors, and environment entities) to extract salient cues for timely decisions; without targeted filtering, decision latency and credit assignment deteriorate. Traditional rule-based and control-theoretic schemes—e.g., leader–follower and virtual-structure/potential-field designs [

4,

5], model predictive control (MPC) [

6,

7], and consensus/distributed optimization [

8,

9]—offer clarity and guarantees but are sensitive to modeling errors, communication delay, and dynamic clutter typical of urban scenes.

(2) Multi-objective trade-offs. Formation keeping, obstacle avoidance, task efficiency, and energy economy often conflict; scalarizing them with fixed linear weights masks Pareto structure and yields brittle policies when mission priorities shift.

(3) Scalability and robustness. In practice, packet loss, sensor noise, and non-stationarity degrade performance; vanilla deep MARL methods (e.g., MADDPG-style CTDE) improve coordination [

10,

11,

12] yet still lack explicit mechanisms for dynamic information selection and principled multi-objective optimization, causing sharp performance drops as agent count or scene complexity increases [

13].

To address these challenges, we present a

reinforcement learning method that augments a CTDE-style backbone with

multi-source attention and a

Pareto optimization module. Specifically, we equip decentralized actors with three lightweight attention branches—self attention for intra-state feature selection, inter-agent attention for targeted neighbor reasoning, and entity attention for salient environment perception—whose outputs are concatenated into an attention-enhanced representation. In training, a vector-valued reward models task progress, energy, formation coherence, and safety; a Pareto module maintains a compact archive of non-dominated solutions and provides adaptive weights for updates, avoiding heavy manual reward tuning while preserving simple, interpretable shaping terms for each objective.In a representative 3D urban-like environment, the proposed modules consistently improve team success, safety, and formation quality across 2–5 UAVs with comparable or lower control effort; detailed results are reported in

Section 6.

The main contributions are summarized as follows:

We develop a multi-source attention design (self/inter-agent/entity) for decentralized actors that selectively fuses critical cues from self, teammates, and urban environment entities, improving coordination efficiency and robustness under partial observability.

We introduce a Pareto optimization module for vector rewards that approximates the Pareto front during training, enabling adaptive trade-offs across task efficiency, formation coherence, energy, and safety with only simple, objective-wise shaping terms—not heavy ad hoc manual weighting.

We integrate the above as architecture-agnostic, plug-and-play modules for CTDE-style MARL and validate them in 3D city-like scenes. Across teams of –5 UAVs, inserting our modules into representative MARL backbones increases final team success by about – percentage points and reduces collisions by roughly 20–, with tighter formation tracking at comparable or lower control effort; the gains persist from two to five agents, indicating effectiveness and scalability in complex urban environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 details background knowledge.

Section 4 Section 5 provides an in-depth explanation of our proposed algorithm framework, including the implementation details of the graph attention mechanism and the Pareto multi-objective optimization module.

Section 6 presents the detailed experimental setup and the analysis of the results. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Current Research on Multi-UAV Formation Control

Practical deployments are increasingly moving to

urban/built-up scenes with dense buildings, occlusions, and narrow corridors, where multi-UAV formations support communication relaying, cooperative search, and safe navigation between high-rises. Rule-based and classical control schemes—such as leader–follower and virtual-structure/potential-field designs—remain popular for their clarity and ease of deployment [

4,

5]. Optimization-theoretic approaches including model predictive control (MPC) and consensus/distributed control offer stronger constraint handling and stability guarantees [

6,

7,

9,

14]. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has recently shown promise in handling high-dimensional observations and partial observability, and has been explored for formation, trajectory design, and cooperative navigation [

11,

15,

16].

However, when mapped to city-like environments, these lines face three recurring challenges that align with our problem setting.

(i) Selective information use under partial observability: controllers must extract salient cues from

self,

neighbors, and

environmental entities in high-dimensional, cluttered scenes; fixed-rule filters or hand-crafted interfaces struggle as complexity grows.

(ii) Multi-objective trade-offs: formation coherence, obstacle avoidance/safety, task efficiency, and energy economy often conflict; scalarizing them with fixed linear weights blurs Pareto structure and leads to brittle behavior when mission priorities shift.

(iii) Scalability and robustness: communication delays, packet loss, and sensor noise degrade coordination, and performance tends to drop sharply as agent count or urban clutter increases [

11]. Within optimization/control methods, even with disturbance observers and estimation filters (e.g., Kalman-consensus and disturbance observers in MPC pipelines [

7]), the burden of online optimization and model mismatch in cluttered 3D geometry limits agility. In DRL pipelines, the absence of

explicit mechanisms for dynamic information selection and principled multi-objective optimization remains a key gap.

2.2. Attention Mechanisms for Collaborative Perception and Decision-Making

Attention has been introduced to enhance multi-agent perception/communication and to focus computation on salient cues in cooperative UAV tasks. For trajectory design and resource assignment, graph attention has improved performance by letting agents emphasize critical neighbors and links [

17]. For cooperative encirclement/rounding, multi-head soft attention yields targeted coordination signals [

18]. Transformer-style designs with virtual objects have been used for short-range air combat maneuver decision, showing improved decision quality via structured attention to key entities [

19]. In adversarial/dangerous settings such as missile avoidance, multi-head attention helps capture dynamic obstacles and threat saliencies [

20].

These studies collectively indicate that multi-source attention (self/neighbor/entity) can improve collaborative perception and decision quality. At the same time, prior work typically optimizes a single scalarized return and does not explicitly couple attention with multi-objective value estimation; as a result, policies may overfit to a particular weight setting and generalize poorly when objective priorities change (e.g., switching from aggressive goal-seeking to safety-first in narrow corridors). Our method targets this gap by pairing lightweight attention branches with vector-valued critics and Pareto-aware training.

2.3. Advances in Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) and Pareto Methods

Pareto-based multi-objective optimization (MOO) offers a principled way to expose trade-offs among conflicting objectives without collapsing them into a single weighted sum. In UAV-related literature, NSGA-III and variants have been applied to task allocation and planning under complex constraints [

21,

22]; MOEA/D with adaptive weights has improved solution-set uniformity and has been used for 3D path planning [

23]; and dynamic multi-objective resource allocation has been investigated in related communication/energy settings [

24,

25]. These techniques are effective at

offline design and static instances, but their computational footprint and lack of tight coupling with the perception–decision pipeline make end-to-end,

online deployment in cluttered, partially observable environments difficult.

Accordingly, there is a need to integrate Pareto reasoning into learning-based coordination rather than treating MOO as an external, offline post-processor. Our approach follows this direction: we retain simple, objective-wise shaping signals (task progress, energy, formation coherence, safety) and train vector-valued critics, while a compact Pareto archive provides adaptive training weights to encourage non-dominated policy updates within the MARL loop.

2.4. Summary and Gaps

Summarizing, (i) classical rule/optimization controllers are strong when models and communication are reliable but struggle to select salient information and adapt in cluttered urban scenes; (ii) DRL scales to high-dimensional observations yet often relies on ad hoc scalarization, lacking a principled mechanism to balance competing goals; and (iii) existing attention applications improve perception/coordination but are typically optimized for a single weighted objective, limiting robustness when priorities change. This paper addresses these gaps by combining multi-source attention (self/inter-agent/entity) for selective information fusion with a Pareto module for vector rewards, integrated into a CTDE-style method so that non-dominated trade-offs are discovered during training rather than predetermined by fixed weights.

3. Background Knowledge

3.1. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) is a key framework for handling multiple agents that pursue cooperative or competitive goals through sequential decisions in a shared environment. Unlike single-agent reinforcement learning, MARL faces core challenges: environmental non-stationarity, credit assignment, and mutual policy influence among agents. In UAV formation control, these challenges are pronounced. Each UAV must act on local observations, yet their joint actions determine overall system performance.

To address these issues, many MARL paradigms have been proposed. Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE) is the mainstream. Its idea is to use global information during training to learn cooperative policies, while at execution each agent relies only on its own observations. This balances model expressiveness and system scalability. A representative algorithm is MADDPG. It combines a centralized critic with decentralized actors and mitigates non-stationarity to some extent.

However, traditional MARL still has clear limits. Agents often lack selective perception of multi-source state information and cannot focus on key cues in complex environments. Most methods also rely on a scalar reward formed by linear weighting of multiple objectives. This cannot capture complex trade-offs among objectives. These limits motivate our use of attention mechanisms and multi-objective optimization to improve MARL for UAV formation control.

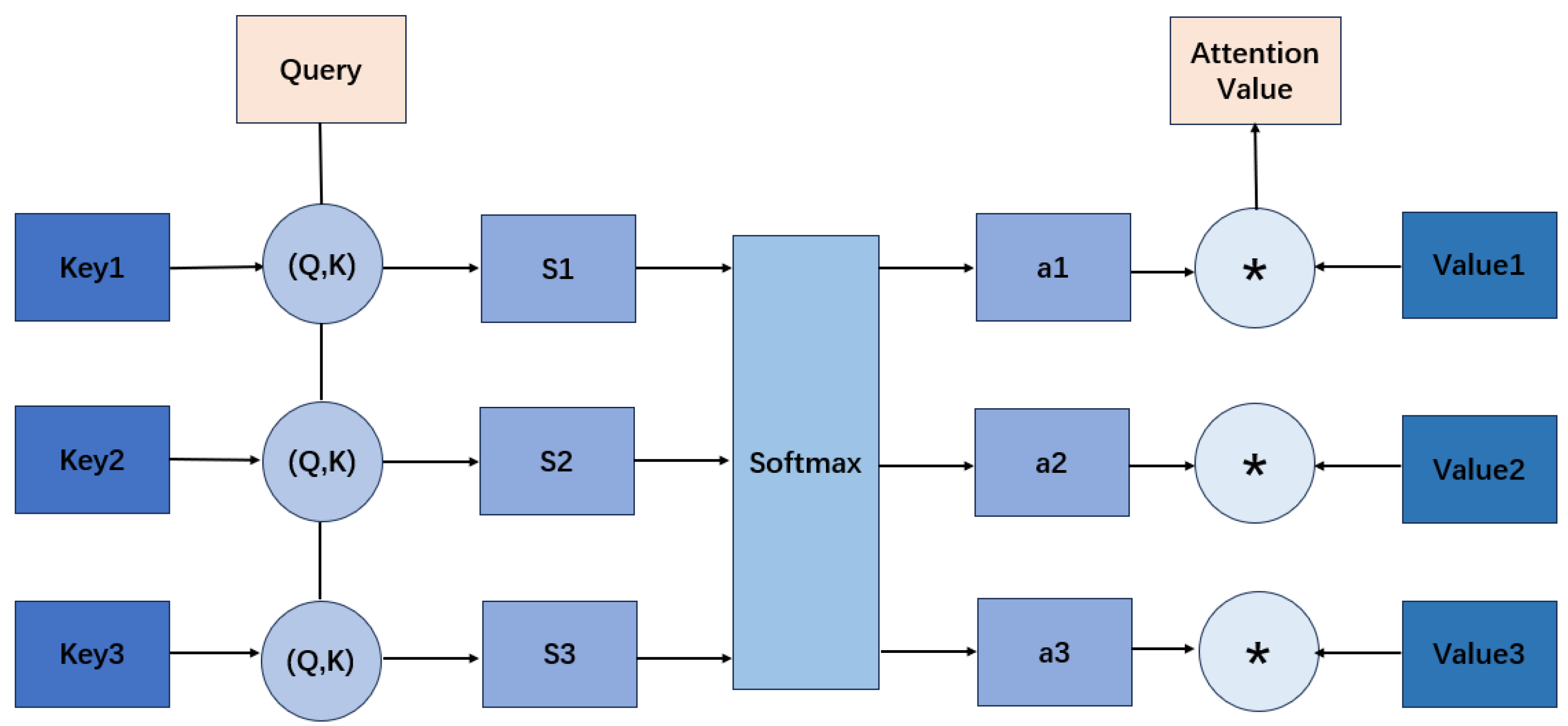

3.2. Attention Mechanisms

Attention provides selective information fusion: a model assigns higher weights to salient parts of its inputs and suppresses distractions, thereby improving long-range dependency modeling and feature prioritization. Beyond its well-known success in NLP and CV, attention is increasingly used in multi-agent systems (MAS)—including cooperative UAV control—to filter self states, neighbor cues, and environmental entities under partial observability and communication imperfections.

We use the standard scaled dot-product attention as the basic operator:

where

queries Q encode the current information need,

keysK index candidate features, and

valuesV carry the content to aggregate. The softmax normalizes relevance scores into a distribution and yields a context vector by weighted summation. Multi-head variants apply (

1) in parallel and concatenate the outputs for richer feature subspaces.

In the context of UAV formation control, attention is particularly useful for:

Selective perception: highlight task-relevant parts of the local observation (e.g., goal direction, energy, safety margins).

Targeted coordination: focus on the most influential neighbors for collision avoidance and formation keeping.

Salient environment awareness: emphasize nearby obstacles or bottlenecks in cluttered, urban-like scenes.

These properties make attention a natural fit for CTDE-style MARL: it improves the actors’ input representations under partial observability and reduces non-stationarity seen by centralized critics. In

Section 4 and

Section 5 we instantiate this idea via self-, inter-agent-, and entity-attention modules tailored to UAV teams.

3.3. Multi-Objective Optimization

Multi-objective optimization handles trade-offs among conflicting objectives. The core concept is Pareto optimality: a solution set where no objective can be improved without worsening another. The problem is formalized as:

In multi-UAV cooperative control, common objectives include path length, energy consumption, safety, and formation-keeping accuracy. Traditional methods often use a scalarization function to convert multiple objectives into a single one, but this cannot fully capture complex trade-offs. Pareto-based methods provide a set of optimal trade-off solutions and give richer information for decision-making.

In summary, this paper integrates multi-agent reinforcement learning, attention mechanisms, and multi-objective optimization to build a collaborative decision framework for multi-UAV formation control. It addresses multi-objective coordination challenges in dynamic environments.

4. Problem Formulation

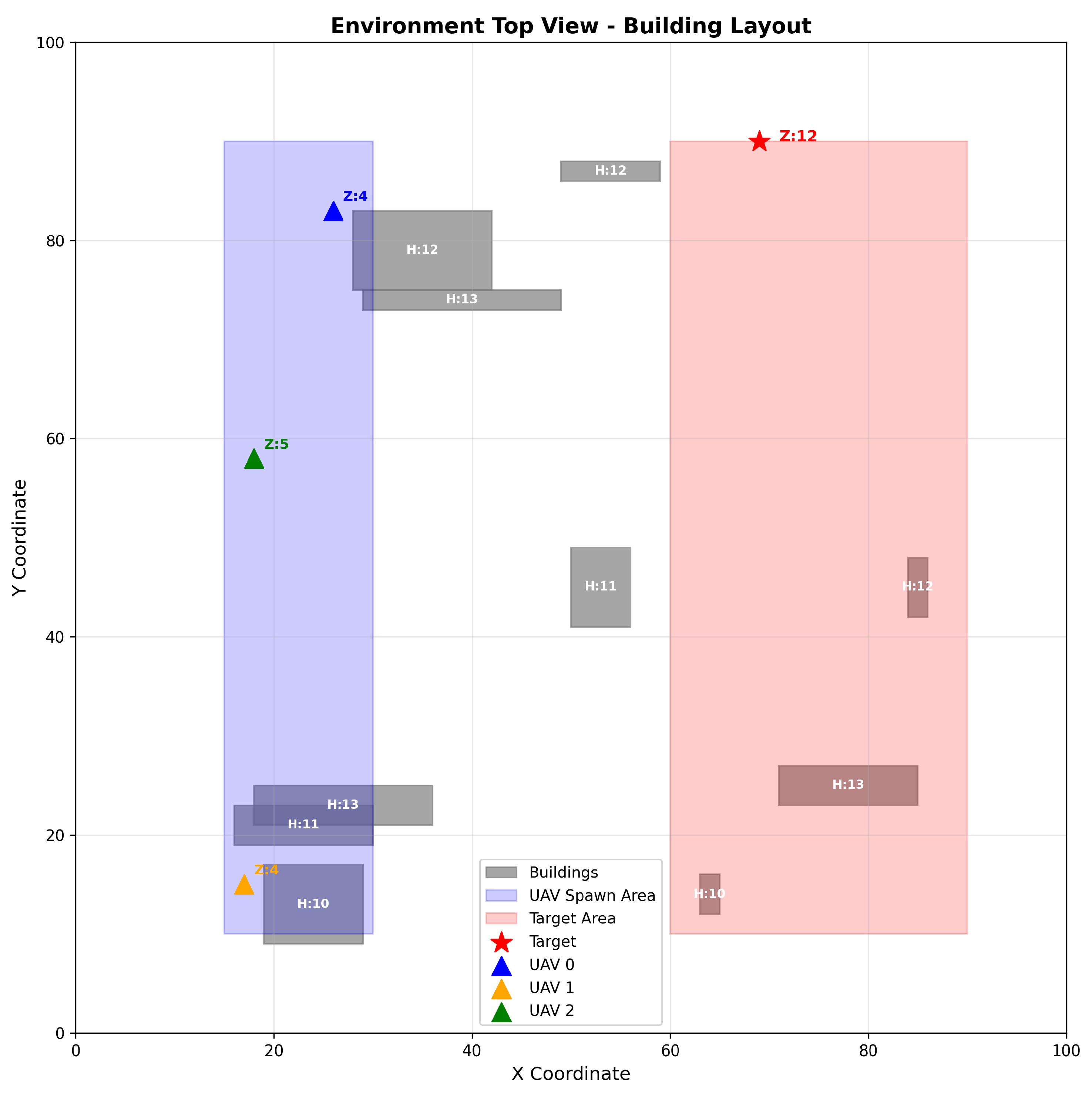

We study cooperative multi–UAV formation control in a built urban area. A team departs from randomized starts and moves to a goal region while (i) avoiding collisions with buildings and teammates, (ii) keeping a prescribed formation, (iii) limiting control/energy usage, and (iv) finishing within a time budget. This setting is representative of city–scale sensing and relay missions, where formation coherence benefits coverage and link reliability.

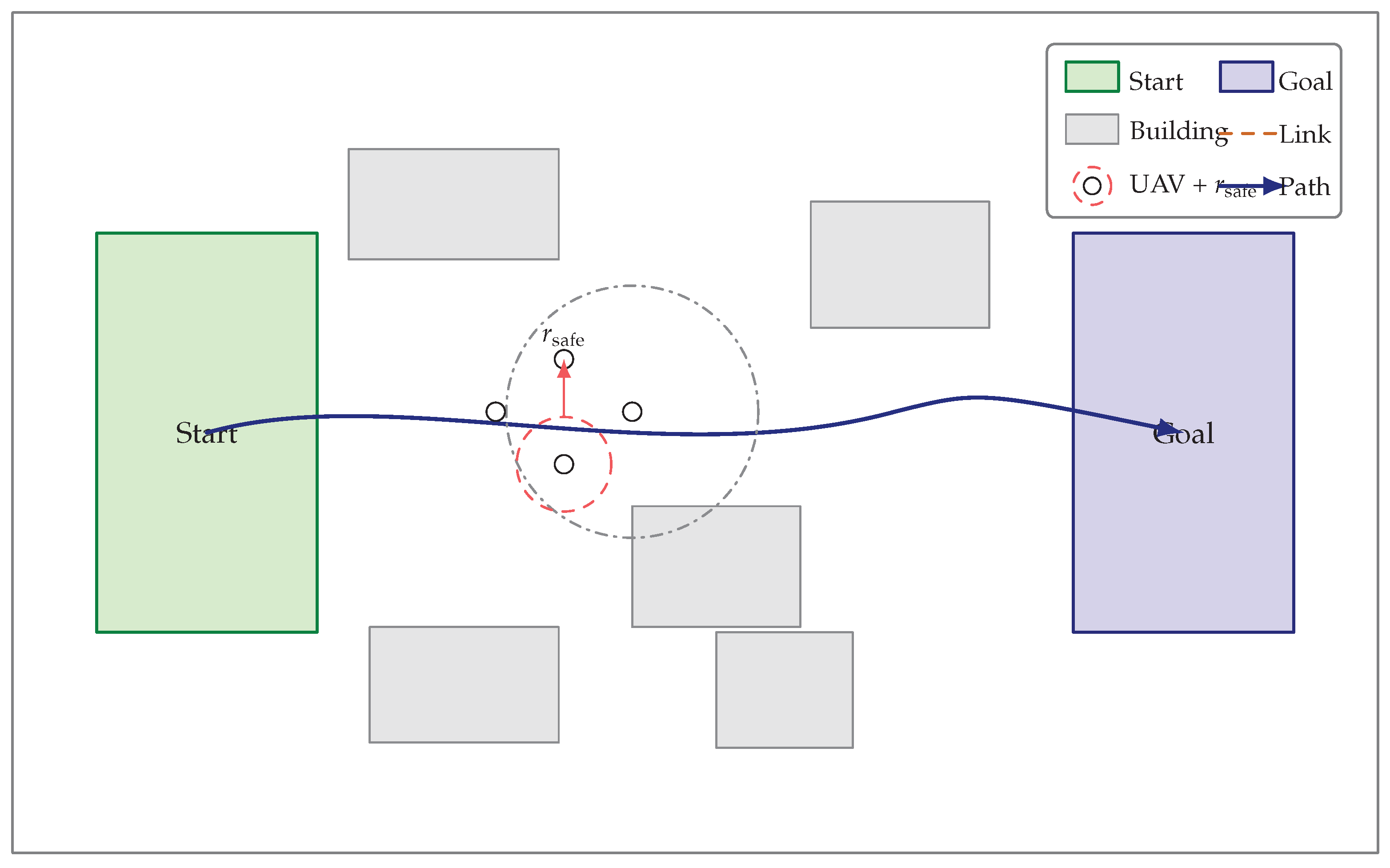

Figure 2.

Problem setup (top view). A team departs from a start region, navigates among buildings, maintains a diamond formation with safety radius , uses local sensing and limited neighbor links, and follows a feasible path toward the goal under energy/time budgets.

Figure 2.

Problem setup (top view). A team departs from a start region, navigates among buildings, maintains a diamond formation with safety radius , uses local sensing and limited neighbor links, and follows a feasible path toward the goal under energy/time budgets.

4.1. Game Model and CTDE Setting

We model the task as a partially observable Markov game (POMG) with discrete time and step . The agent set is . Training follows CTDE: a centralized critic sees global information during learning, whereas execution relies only on local observations.

For the critic, the global state stacks team kinematics, the goal and the formation blueprint, and nearby obstacles:

where

and

are positions and velocities,

G encodes the goal pose/region,

stores desired slot offsets

(formation template), and

lists the

M nearest axis–aligned buildings represented by centers and half–sizes.

4.2. Observations and Actions

Each agent observes only local information. To match the three attention branches used later, we organize the local observation into three parts and then fuse them as

Self features. , where

and

are position and velocity,

is heading,

is normalized remaining energy, and

is distance to the goal.

Inter–agent features. For the

K nearest neighbors

, we use relative kinematics

with fixed

K (e.g.,

) recomputed each step.

Entity features. For the

M closest buildings to agent

i,

, where

is the building center and

are half–sizes; a small

M (e.g.,

) keeps inference time predictable. Actions are 3-D thrust/velocity commands subject to a magnitude bound,

4.3. Vector Reward and Termination

Control is multi-objective. Each agent receives a four-dimensional reward covering task progress, energy, formation coherence, and safety,

with homogeneous definitions and fixed coefficients across runs (defaults in parentheses).

Task progress and success. With

and

,

so moving closer to the goal is rewarded each step and entering the

-ball yields a one-off bonus.

Energy/control. With

,

Formation coherence. With

and

,

where the reference slot

follows a (virtual) leader; small average slot error is mildly rewarded.

Safety. With

,

, and

m,

where

is the distance to the nearest building surface. An episode ends when all agents are in the goal region, upon any collision, or at the horizon

T.

4.4. Objective and CTDE Realization

We seek decentralized actors that are Pareto–efficient with respect to the four objectives under a centralized critic. Let the joint policy be

with per–agent actor

. The vector return averaged across agents is

and policies are ordered by Pareto dominance (no worse in all objectives and strictly better in at least one). The centralized critic estimates per–objective values that guide updates,

while the actors consume

constructed in (

4). This separation keeps modeling choices (rewards and constraints) and architecture (attention and CTDE) cleanly decoupled.

Table 1.

Notation used in the formulation.

Table 1.

Notation used in the formulation.

| Symbol |

Description |

|

Agent set and its size |

|

Time index, horizon, and time step |

|

Global state, local observation, and action |

| G |

Goal pose/region encoding |

|

Formation template and per–agent slot offset |

|

Set of M nearest buildings (centers and half–sizes) |

| K |

Number of neighbor slots in

|

|

Reward vector in (6) |

|

Discount factor |

|

Decentralized policy and joint policy |

|

Per–objective centralized critic in (12) |

|

Action bound, safety distance, goal threshold |

5. Proposed Method

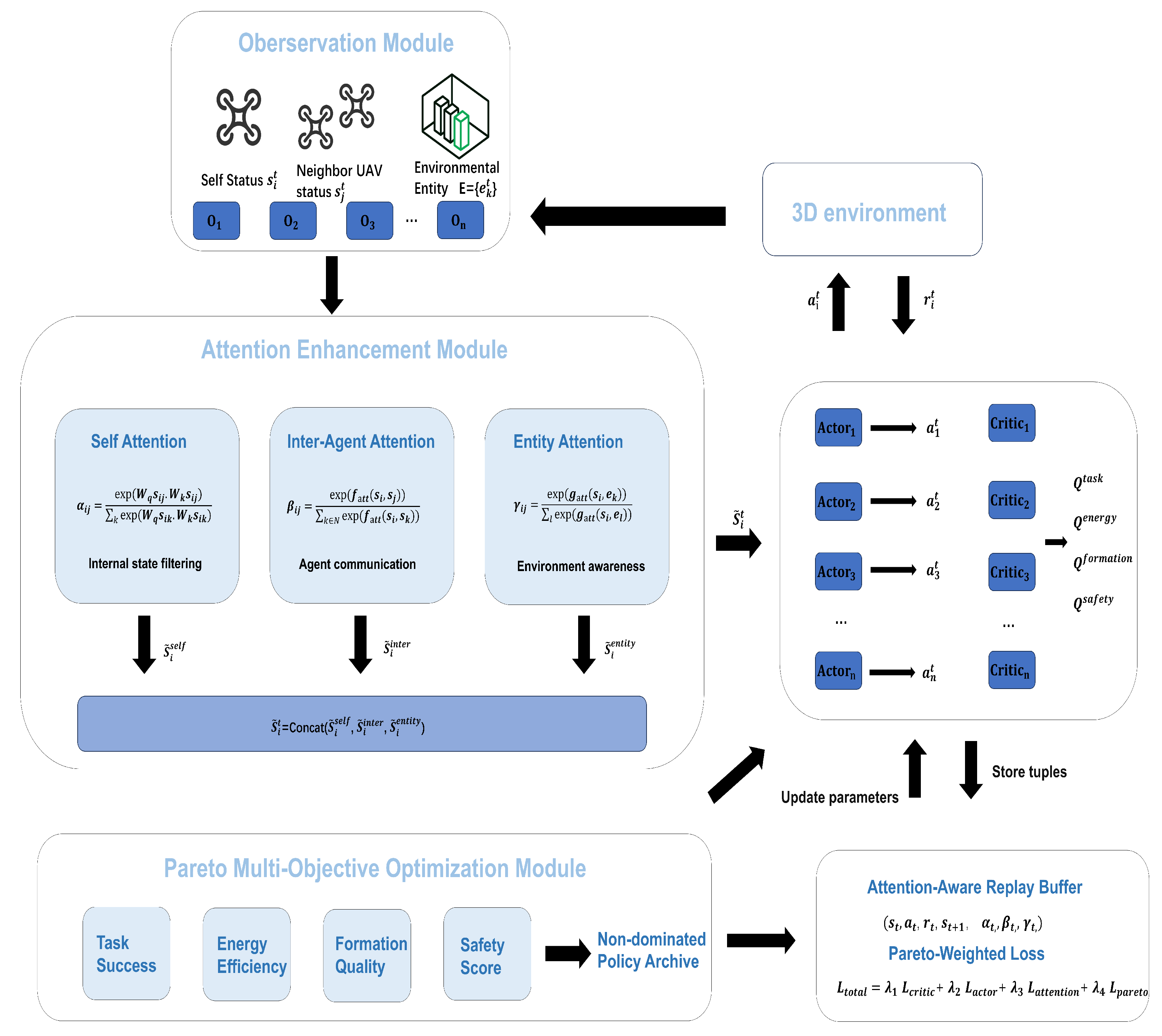

5.1. Framework Overview

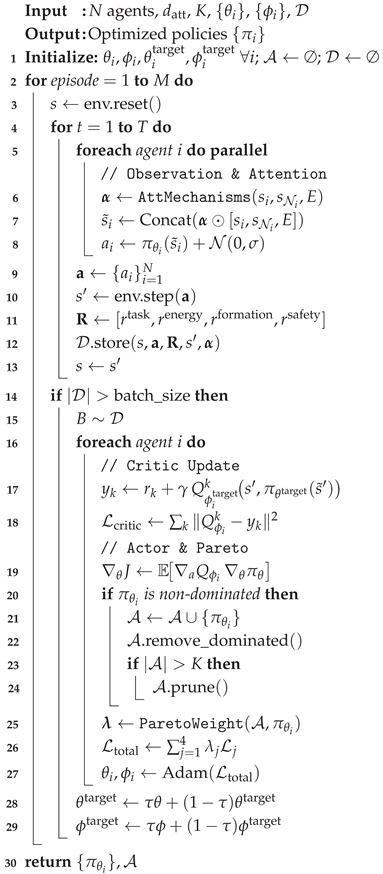

This paper proposes an improved framework for autonomous UAV formation control that is algorithm-agnostic: the two core components—a multi-source attention block (self / inter-agent / entity) and a Pareto multi-objective optimization layer with vector-valued critics—can be plugged into any CTDE-style actor–critic MARL algorithm. In this work we instantiate the framework with MADDPG to provide a concrete realization and fair comparison, but the design applies equally to other backbones (e.g., MATD3/MASAC/MAPPO).

MADDPG, a common MARL method, follows the Centralized Training–Decentralized Execution (CTDE) paradigm: a centralized critic evaluates global information during training, and decentralized actors execute from local observations. Building on this backbone, we introduce attention mechanisms to enhance the handling and fusion of local observations under partial observability. As shown in

Figure 1, the overall pipeline still follows CTDE but is adapted to multi-objective formation control.

Specifically, each UAV decides from its local observation, while the Attention Enhancement Layer applies three lightweight modules—self attention, inter-agent attention, and entity attention—to selectively emphasize salient cues. The three outputs are concatenated into an attention-enhanced representation . The Actor maps to action , and centralized Critics estimate per-objective values in parallel. During training, the Pareto layer maintains a compact archive of non-dominated solutions and provides adaptive signals/weights to guide updates, thereby avoiding brittle manual scalarization. We store in an attention-aware replay buffer and optimize a combined loss .

In summary, when instantiated with MADDPG (

Figure 1), the attention block improves information saliency under partial observability and the Pareto layer enforces principled multi-objective trade-offs;

more generally, these two modules augment the chosen MARL backbone with minimal changes and are applicable to a wide range of CTDE actor–critic methods beyond MADDPG.

5.2. Attention Mechanism Integration

The attention mechanisms in our framework serve three distinct but complementary purposes: enhancing inter-agent communication, improving environmental perception, and enabling hierarchical decision-making. Each mechanism addresses specific challenges in multi-agent coordination while contributing to the overall system performance. Below we detail the three attention mechanisms integrated in our framework.

Self-Attention Mechanism: The self-attention mechanism processes the internal state representation of each UAV agent to identify the most relevant features for decision-making. Given an agent’s state vector

, the self-attention module computes attention weights

for each state component

j:

where

and

are learned query and key transformation matrices. This mechanism enables agents to dynamically prioritize different aspects of their internal state based on the current situation, improving decision quality in complex scenarios through adaptive feature weighting.

Inter-Agent Attention Mechanism: The inter-agent attention mechanism facilitates explicit communication between UAV agents by computing attention weights over neighboring agents’ states. For agent

i with neighbors

, the inter-agent attention weight for neighbor

j is computed as:

where

is a neural network that computes the relevance score between agent

i and agent

j. This mechanism allows agents to selectively focus on the most relevant teammates for coordination, enabling effective formation maintenance and collision avoidance through targeted information exchange.

Entity Attention Mechanism: The entity attention mechanism processes environmental entities such as obstacles, targets, and dynamic elements. Given a set of environmental entities

, the mechanism computes attention weights to determine the relevance of each entity to the current agent:

This mechanism enables agents to dynamically focus on the most relevant environmental features, significantly improving navigation efficiency and obstacle avoidance capabilities by filtering irrelevant sensory input.

Within the CTDE pipeline, attention acts as the front end of representation. Self–attention filters an agent’s own kinematics and intent, inter–agent attention highlights the few teammates that matter for the current maneuver, and entity attention foregrounds the most influential obstacles.The fused vector is therefore more structured and temporally stable than raw observations, so the centralized multi–objective critics receive inputs in which progress, formation deviation, energy use, and risk are easier to tease apart.In practice this yields cleaner per–objective value estimates and crisper policy gradients, reducing ambiguity about which agent and which objective should change.Attention thus strengthens state representation on the actor side and, as a consequence, helps the critics allocate credit with fewer confounding correlations.

5.3. Pareto Multi-Objective Optimization

The Pareto optimization component addresses the inherent multi-objective nature of UAV formation control, where agents must simultaneously optimize competing objectives including task completion, energy efficiency, formation maintenance, and collision avoidance. Traditional reinforcement learning approaches struggle with such multi-objective scenarios due to the difficulty in defining appropriate reward weightings.

Our Pareto-based framework formulates the problem as a multi-objective optimization where the reward function

for agent

i consists of distinct objective components:

each representing critical operational dimensions. The approach maintains a set of non-dominated solutions, enabling exploration of diverse objective trade-offs without manual tuning of reward weights.

The Pareto dominance relationship is defined such that solution

x dominates solution

y if

x is at least as good as

y in all objectives and strictly better in at least one objective. The algorithm maintains an archive of non-dominated solutions to guide policy updates:

The above update is carried out under explicit Pareto-optimality constraints, which preserve non-dominated solutions and encourage coverage of diverse trade-offs across objectives. This constraint guarantees that selected policies represent efficient compromises between competing goals.

This approach fundamentally eliminates the need for manual reward engineering while ensuring robust performance across all operational dimensions. The practical significance is particularly valuable in UAV missions where objective priorities dynamically shift during different mission phases, providing adaptive optimization without parameter recalibration.

5.4. Integrated Framework Architecture

The integrated framework incorporates attention mechanisms with Pareto optimization within a modified MADDPG architecture through a hierarchical processing pipeline. This unified structure comprises three principal components: an attention-enhanced observation processor, a multi-objective critic network, and a coordinated actor network, collectively forming the core innovation of our approach.

The attention-enhanced observation processor transforms raw sensory inputs into enriched state representations through sequential attention layers. This module simultaneously applies self-attention to internal states, inter-agent attention to neighboring UAV states, and entity attention to environmental features. The resulting representations are concatenated to form a comprehensive state vector:

where each attention module operates according to the mechanisms defined in Section 3.1.2.

The multi-objective critic network extends conventional value estimation by maintaining separate value functions for each operational dimension:

This architectural innovation enables distinct value estimation for competing objectives, facilitating precise credit assignment during policy updates under Pareto constraints.

The coordinated actor network synthesizes the attention-enhanced state representations into actions that balance individual objectives with collective coordination requirements. To ensure training stability in decentralized execution, the network architecture incorporates residual connections and layer normalization techniques:

A critical feedback loop emerges between these components: attention mechanisms dynamically inform policy decisions, which subsequently reshape attention patterns as environmental conditions evolve. This adaptive interaction enables continuous optimization of mission-specific trade-offs without manual parameter adjustment.

5.5. Training Algorithm and Implementation

Our training methodology extends the MADDPG framework with integrated attention mechanisms and Pareto optimization, creating a robust learning system for multi-UAV coordination. The algorithm maintains the CTDE paradigm, where centralized critics leverage global information during training while decentralized actors operate solely on local observations during mission execution. This architecture preserves the scalability advantages of decentralized systems while benefiting from centralized learning.

A critical innovation lies in the attention-aware experience replay mechanism. Traditional experience tuples are augmented with attention context vectors capturing the instantaneous focus patterns across all three attention mechanisms. This preservation of attention context during replay significantly enhances learning stability and prevents catastrophic forgetting of attention patterns. The replay buffer implements stratified sampling to ensure balanced representation across diverse attention contexts and mission scenarios.

The multi-objective loss function incorporates four essential components with Pareto-optimized dynamic weighting:

where

enforces temporal consistency in attention weight learning and

maintains diversity in the evolving Pareto front. The adaptive coefficients

are adjusted based on the dominance relationships within the current solution archive.

Implementation employs PyTorch with custom CUDA kernels optimized for parallel attention computation. Network architectures utilize multilayer perceptrons with ReLU activations and batch normalization, with hyperparameters including attention dimension , replay buffer capacity of transitions, batch size of 256, and discount factor . The Pareto archive maintains up to 100 non-dominated solutions to balance solution diversity against computational overhead.

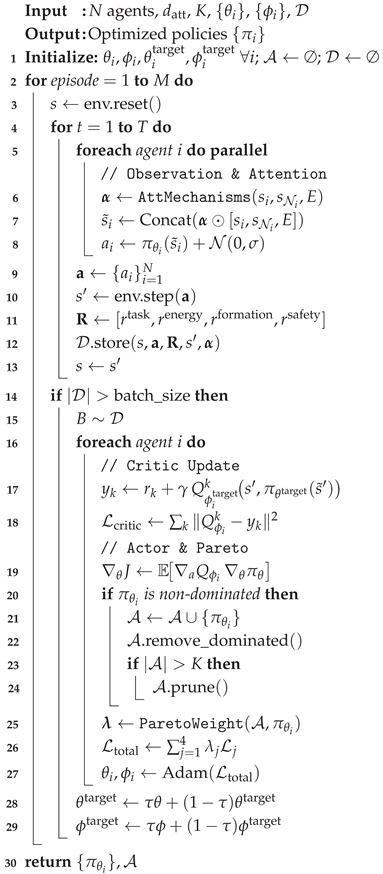

The overall algorithm process of the paper is shown in the following pseudocode

|

Algorithm 1: Multi-Attention Meets Pareto Optimization |

|

6. Experiment

6.1. Experimental Setup

Comprehensive experiments were conducted across diverse UAV formation control scenarios to evaluate the performance of our attention-enhanced MADDPG framework. The evaluation protocol includes comparative analysis against state-of-the-art multi-agent reinforcement learning methods, ablation studies of individual components, and sensitivity analysis of key hyperparameters.

The hardware infrastructure comprised a high-performance computing cluster featuring NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs (24GB VRAM per device), Intel Xeon Gold 6248R processors (3.0GHz, 24 cores), and 128GB DDR4 memory. All experiments executed under Ubuntu 20.04 LTS with CUDA 11.8 and cuDNN 8.6 acceleration. To maximize computational throughput, multi-GPU training with data parallelism across four GPUs was employed for resource-intensive configurations.

Implementation leveraged PyTorch 2.0.1 with Python 3.9.16 as the foundational software stack. Essential dependencies included NumPy 1.24.3 for numerical operations, Matplotlib 3.7.1 for visualization, TensorBoard 2.13.0 for experiment logging, and OpenAI Gym 0.21.0 for environment interfaces. Custom CUDA kernels optimized attention computations for enhanced execution efficiency.

Hyperparameter configuration, established through systematic grid search, is comprehensively detailed in Table 1. Critical parameters encompassed actor learning rate (), critic learning rate (), replay buffer capacity ( transitions), batch size (256), discount factor (0.99), soft update coefficient (0.01), attention dimension (64), and Pareto archive size (100). Training proceeded for 2000 episodes with early termination upon satisfaction of convergence criteria.

Table 2.

Hyperparameters of the Proposed Multi-Agent Attention-DRL Framework.

Table 2.

Hyperparameters of the Proposed Multi-Agent Attention-DRL Framework.

| Category |

Parameter |

Value |

| Network Architecture |

Actor hidden layers |

[256, 128] |

| |

Critic hidden layers |

[512, 256, 128] |

| |

Attention dimension |

64 |

| Training |

Actor learning rate |

|

| |

Critic learning rate |

|

| |

Batch size |

256 |

| |

Replay buffer size |

|

| |

Discount factor

|

0.99 |

| |

Soft-update

|

0.01 |

| Attention |

Self-attention heads |

4 |

| |

Inter-agent range (m) |

10.0 |

| |

Entity attention range (m) |

15.0 |

| Pareto Archive |

Archive size |

100 |

| |

Update frequency |

10 steps |

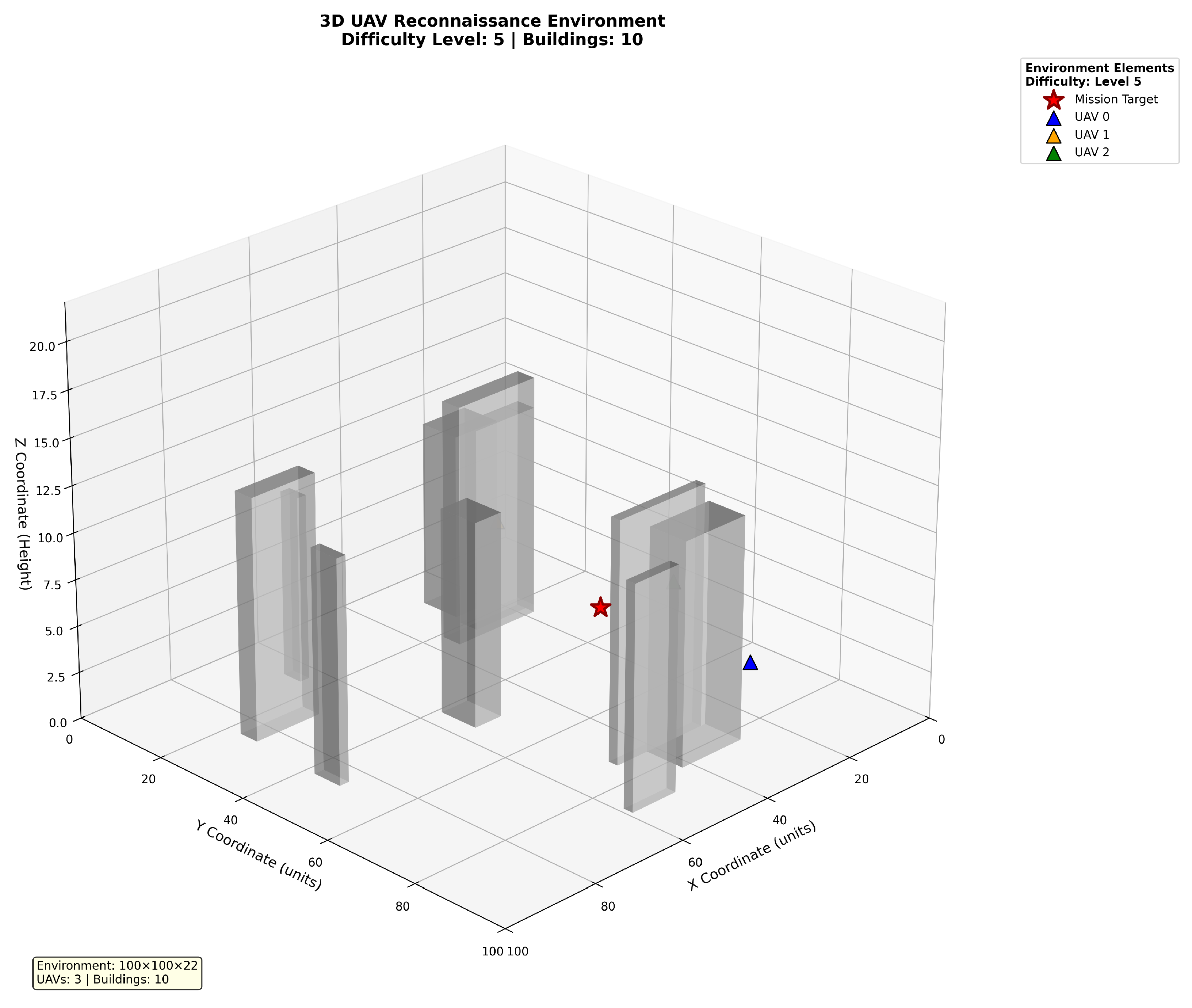

6.2. Experimental Environment

The workspace is a 3D volume with

,

, and

. Buildings are randomly generated in this region, with both location and size sampled at random. To avoid excessive obstacles at the start of training, the number of buildings increases gradually as training proceeds; when the success rate over the most recent 100 navigation tasks exceeds 70%, the building count is increased. The total number of buildings is capped at 20. Buildings lie within

,

on the plane; their half-lengths are in

, half-widths in

, and heights in

. The initial UAV region is

,

,

; the target region is

,

,

. A 2D top-down view in

Figure 4. further illustrates the scene configuration.

6.3. Experimental Results and Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate the superior performance of our attention-enhanced MADDPG framework across all evaluation scenarios. Our approach consistently outperforms baseline methods in terms of task success rate, formation quality, and sample efficiency. The following subsections provide detailed analysis of the comparative results, ablation studies, and sensitivity analysis.

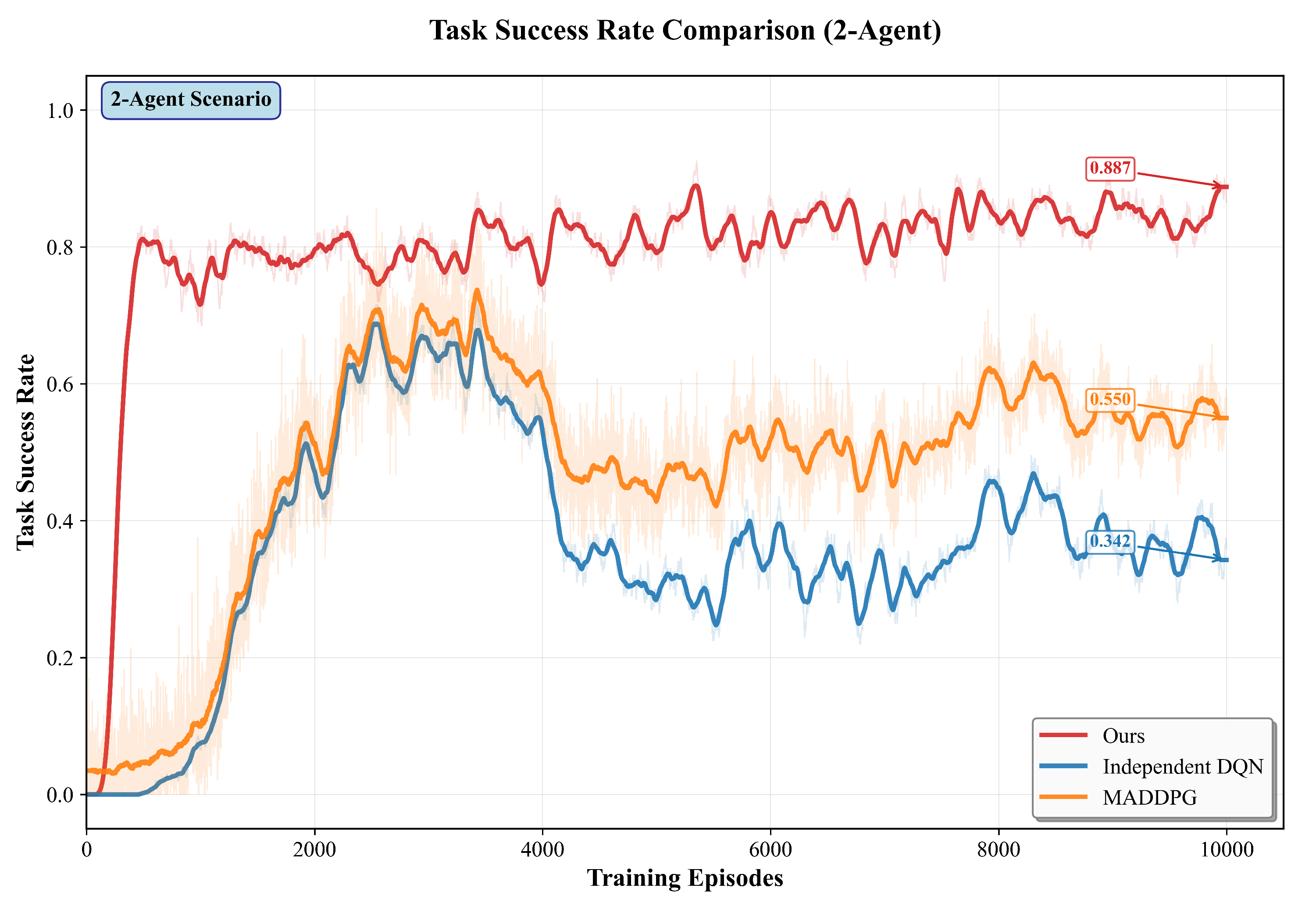

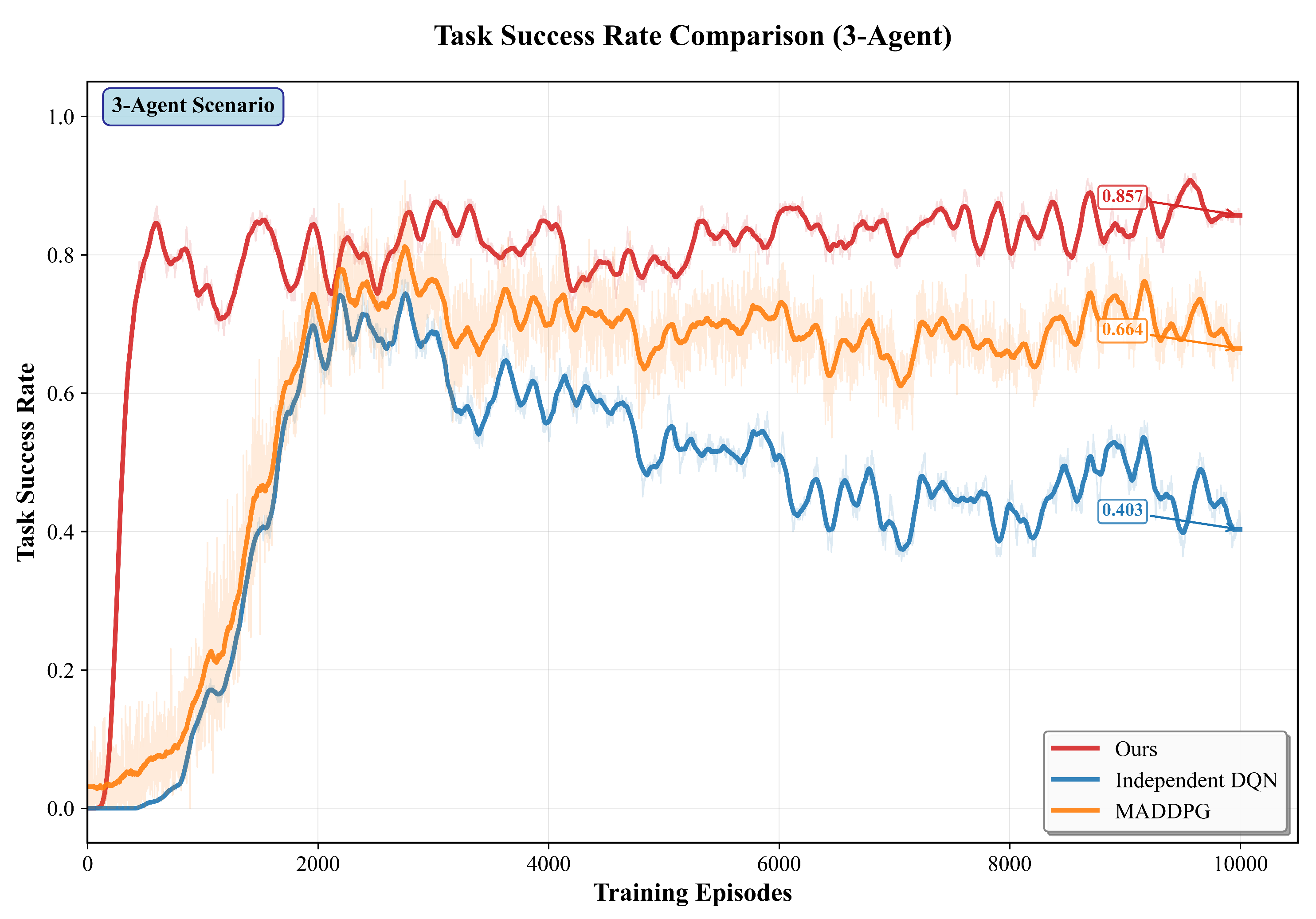

6.3.1. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

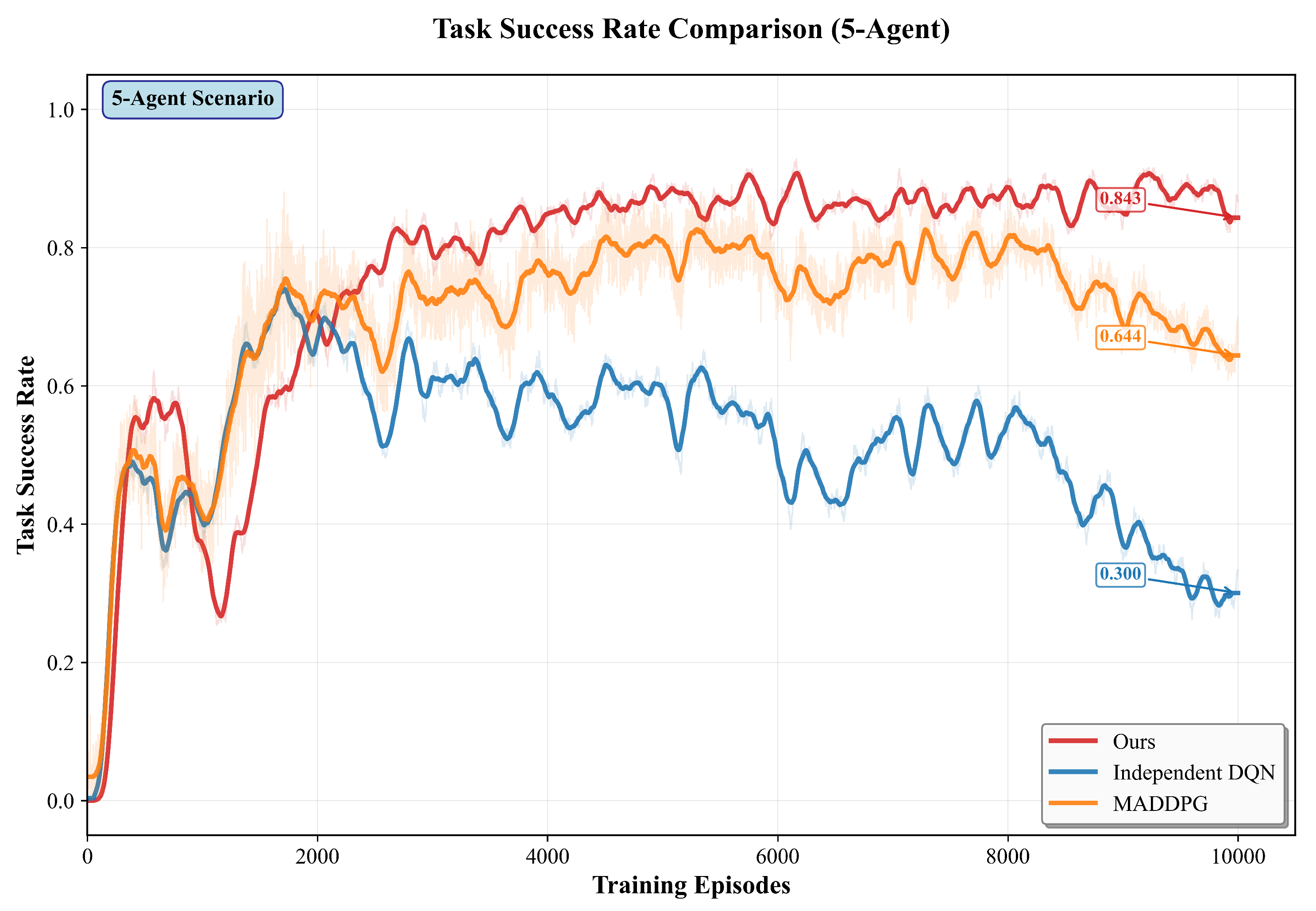

We compare the proposed method with MADDPG and IDQN under 2, 3, and 5 agents. All methods use the same network architecture and training setup to ensure fairness. In the 2, 3, and 5-agent settings, our method achieves higher overall task success than MADDPG and IDQN. As the number of agents grows, performance remains stable.

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 further shows the training curves of success rate for 2-agent to 5-agent in 10000 episodes.The training results for scenarios with 2, 3, and 5 agents are presented in Table 3.

For two agents (), our method attains a final team success rate of 84.6%, versus 57.4% for MADDPG and 47.8% for IDQN, absolute gains of +27.2 pp (vs MADDPG) and +36.8 pp (vs IDQN).

For three agents (), our method reaches 83.1%, compared with 70.4% (MADDPG) and 58.1% (IDQN), yielding gains of +12.7 pp and +25.0 pp.

For five agents (), our method achieves 81.7%, while MADDPG and IDQN obtain 68.6% and 55.7%; the corresponding gains are +13.1 pp and +26.0 pp.

In

Figure 5–7, the baselines rise quickly in the first ∼3k episodes and then drift downward.Two factors explain this pattern. First, the curriculum in environmetal setup increases obstacle density once the rolling success exceeds 70%, which shifts the data distribution from sparse to cluttered layouts and breaks the policies that have adapted to the earlier regime.Second, off-policy value learning with replay mixes old (easy) and new (hard) experiences, so the critic targets become non-stationary; in DDPG/DQN-style learners this often amplifies overestimation and causes policy chattering in dense scenes.

By contrast, our approach degrades less after the curriculum switch: the attention modules yield a cleaner state representation for the critic, and the multi-objective (task/formation/safety/energy) signals regularize updates when the environment hardens, reducing regressions. For clarity, evaluation curves are reported with deterministic actors (no exploration noise).

Table 3.

Final team success rate (%) after training (mean over 5 seeds).

Table 3.

Final team success rate (%) after training (mean over 5 seeds).

| Method |

|

|

|

| PA-MADDPG (ours) |

84.6 |

83.1 |

81.7 |

| MADDPG |

57.4 |

70.4 |

68.6 |

| IDQN |

47.8 |

58.1 |

55.7 |

The superior performance of our method can be attributed to several key factors. First, the attention mechanisms enable more effective information processing and agent coordination, leading to better formation maintenance and obstacle avoidance. The self-attention mechanism helps agents focus on relevant state features, while inter-agent attention facilitates explicit coordination signals. Second, the Pareto optimization framework effectively balances multiple objectives without requiring manual reward tuning, resulting in more robust policies. Third, the integrated architecture creates synergistic effects between attention and multi-objective optimization, leading to emergent coordination behaviors that are difficult to achieve with traditional methods.

6.3.2. Ablation Study on Attention Mechanisms

A systematic ablation study was conducted to validate the individual contributions of each attention component by progressively removing mechanisms from the full framework. This analysis quantifies the specific impact of self-attention, inter-agent attention, and entity attention on overall system performance. Five configurations were evaluated: the complete framework with all attention components; removal of entity attention; removal of inter-agent attention; removal of self-attention; and a baseline without any attention mechanisms.

Table 4.

Ablation Study Results of Attention Modules.

Table 4.

Ablation Study Results of Attention Modules.

| Configuration |

Success |

Formation |

Collision |

Energy |

| |

Rate (%) |

Dev. (m) |

Rate (%) |

Efficiency |

| Full Model |

88.7 ± 1.8 |

1.47 ± 0.15 |

3.2 ± 0.8 |

0.86 ± 0.04 |

| w/o Entity Attention |

87.1 ± 2.3 |

1.89 ± 0.21 |

4.7 ± 1.1 |

0.81 ± 0.05 |

| w/o Inter-Agent Attention |

82.4 ± 2.8 |

2.15 ± 0.26 |

6.3 ± 1.4 |

0.78 ± 0.06 |

| w/o Self-Attention |

85.7 ± 2.5 |

1.98 ± 0.23 |

5.1 ± 1.2 |

0.79 ± 0.05 |

| w/o All Attention |

78.5 ± 2.8 |

2.31 ± 0.22 |

6.8 ± 1.2 |

0.74 ± 0.06 |

The ablation results reveal several critical insights. First, inter-agent attention demonstrates the most significant individual impact, with its removal causing the largest performance degradation (success rate dropping to 82.4%). This highlights its essential role in maintaining coordination stability and preventing collisions. Second, entity attention proves crucial for environmental awareness, as its absence increases collision rates and reduces navigation efficiency. Third, self-attention contributes substantially to energy optimization, with its removal noticeably decreasing control efficiency. Finally, the synergistic effects between attention mechanisms exceed their individual contributions, enabling emergent coordination behaviors that significantly surpass baseline capabilities.

6.3.3. Effectiveness of Pareto Multi-Objective Optimization

To validate the efficacy of Pareto multi-objective optimization, we conducted comparative analyses against traditional weighted-sum reward methods with various manual weight configurations. This evaluation specifically assesses the capability to discover diverse high-quality trade-offs between competing objectives without manual parameter tuning. Five baseline configurations were tested, each emphasizing different objectives as detailed in

Table 5:

Quantitative results in

Table 6 demonstrate that our Pareto approach achieves superior or comparable performance across all objectives simultaneously. In contrast, weighted-sum methods excel only in their specifically emphasized objectives while compromising others.

The Pareto optimization approach demonstrates four key advantages. First, solution diversity enables discovery of multiple high-quality trade-offs, providing operators with adaptable deployment options for varying mission requirements. Second, objective balance ensures superior performance across all metrics simultaneously, avoiding the compromise in non-emphasized objectives observed in weighted-sum methods. Third, automatic discovery eliminates domain-specific manual weight tuning that typically requires extensive expert knowledge. Finally, adaptive optimization maintains diverse solutions during training, guiding exploration toward promising regions of the objective space for more effective learning.

6.3.4. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

Understanding the sensitivity of our method to key hyperparameters is essential for practical deployment and parameter tuning. A comprehensive sensitivity analysis was conducted on three influential parameters: attention dimension, learning rates, and Pareto archive size. This investigation provides critical insights into the approach’s robustness and offers practical guidance for parameter selection across diverse operational scenarios.

The analysis of learning rate combinations revealed relative robustness within reasonable ranges, as illustrated in

Figure 3. Optimal performance emerged at actor learning rate

and critic learning rate

, balancing training stability with rapid convergence. Higher actor rates exceeding

induced training instability, while rates below

significantly slowed convergence.

Evaluation of Pareto archive sizes between 50 and 200 demonstrated that smaller archives limited solution diversity, while archives larger than 150 provided diminishing returns with disproportionate computational costs. The selected size of 100 maintained 85% of maximum diversity with only 60% of the computational overhead of larger archives.

Robustness was quantified under various noise conditions and parameter perturbations, with results detailed in Table 5. Performance remained reasonable even under substantial sensor noise (=0.2) and significant parameter variations (±20% from optimal values), confirming practical applicability in real-world UAV systems.

Table 7.

Robustness evaluation under different perturbations (absolute degradation from nominal 88.7%).

Table 7.

Robustness evaluation under different perturbations (absolute degradation from nominal 88.7%).

| Condition |

Success Rate (%) |

Performance Degradation (pp) |

| Nominal |

88.7 ± 1.8 |

– |

| Sensor Noise () |

85.4 ± 2.1 |

3.3 |

| Sensor Noise () |

82.3 ± 2.8 |

6.4 |

| Learning Rate +20% |

87.9 ± 2.3 |

0.8 |

| Learning Rate

|

86.5 ± 2.0 |

2.2 |

| Attention Dim ±25% |

85.7 ± 2.2 |

3.0 |

| Archive Size ±30% |

87.2 ± 1.9 |

1.5 |

The sensitivity analysis confirms robust performance under moderate parameter variations while retaining sufficient sensitivity to benefit from precise tuning. Identified optimal parameters—attention dimension 64, learning rates /, archive size 100—deliver consistent performance across scenarios. Combined with demonstrated resilience to noise and perturbations, these characteristics establish the method’s suitability for real-world UAV deployment.

The comprehensive experimental evaluation validates the effectiveness and robustness of our attention-enhanced MADDPG framework for UAV formation control. Superior performance across metrics, verified component contributions, and consistent operation under diverse conditions position this approach as a promising solution for real-world multi-agent UAV applications.

7. Conclusion

This paper proposes a unified multi-agent reinforcement learning framework that integrates hierarchical attention mechanisms with Pareto-based multi-objective optimization to address fundamental challenges in autonomous UAV formation control within dynamic, partially-observable environments. Key theoretical contributions include: a comprehensive attention architecture combining self-attention, inter-agent attention, and entity attention, enabling adaptive context-aware information selection; a Pareto optimization module maintaining a compact archive of non-dominated policies that eliminates manual reward-weight tuning while ensuring convergence; and a centralized-training-decentralized-execution framework preserving MADDPG’s convergence guarantees with linear execution complexity scaling. Extensive experiments across agents show consistent gains in team success (by 13–27 pp over MADDPG and 25–37 pp over IDQN), alongside lower collision rates (21–28% relative reductions) and improved formation tracking at comparable control effort.Ablation studies confirm each attention mechanism provides unique performance benefits, while sensitivity analyses show graceful degradation (≤7.5%) under realistic noise and parameter perturbations.

Future research will pursue three complementary directions: conducting outdoor field trials with heterogeneous UAVs to quantify sim-to-real transfer gaps; extending attention mechanisms to handle dynamic communication topologies; and integrating meta-learning for efficient policy transfer across mission types. The resulting framework provides a generalizable foundation for large-scale multi-agent coordination in autonomous logistics, disaster response, and distributed sensing applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and R.J.; methodology, L.Z.; software, L.Z.; resources (initial environment), J.Z.; validation, L.Z. and J.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, L.Z.; data curation, L.Z.; visualization, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.J. and J.Z.; supervision, R.J.; project administration, R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to manufacturer restrictions. Sample images and code can be requested from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Rusheng Ju for guidance on the research direction and manuscript revisions, and Junjie Zeng for contributing the initial course-project environment upon which our multi-UAV simulation was extended.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| MARL |

Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

| MADDPG |

Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| CTDE |

Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution |

| DRL |

Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| MPC |

Model Predictive Control |

| MOEA |

Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

References

- Hassnain, M.S.A.; Hamood, O.N.Q.; Yanlong, L.; H, A.M.; Asghar, K.M. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): practical aspects, applications, open challenges, security issues, and future trends. Intelligent service robotics 2023, 16, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinyong, C.; Rui, Z.; Guibin, S.; Qingwei, L.; Ning, Z. Distributed formation control of multiple aerial vehicles based on guidance route. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2023, 36, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.; Guo, R.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, X.; Ji, J.; Miao, Z. Reinforcement learning-based robust formation control for Multi-UAV systems with switching communication topologies. Neurocomputing 2025, 611, 128591–128591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, P. Leader–follower UAVs formation control based on a deep Q-network collaborative framework. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Q.; Wan, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, D. Formation control of a multi-AUVs system based on virtual structure and artificial potential field on SE(3). Ocean engineering 2022, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevet, T.; Vlad, C.; Maniu, C.S.; Zhang, Y. Decentralized MPC for UAVs Formation Deployment and Reconfiguration with Multiple Outgoing Agents. Springer Netherlands 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danghui, Y.; Weiguo, Z.; Hang, C.; Jingping, S. Robust control strategy for multi-UAVs system using MPC combined with Kalman-consensus filter and disturbance observer. ISA transactions 2022, 135, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.; Meng, Q.; Hinde, C.; Huang, T. A Consensus-Based Grouping Algorithm for Multi-agent Cooperative Task Allocation with Complex Requirements. Cognitive Computation 2014, 6, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesco, L.F.; Elisa, C.; Giorgio, G. A Review of Consensus-based Multi-agent UAV Implementations. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2022, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, M.; Papakonstantinou, K.G.; Andriotis, C.P.; Stoffels, S.M. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning with centralized training and decentralized execution for transportation infrastructure management 2024.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y. Recent progress, challenges and future prospects of applied deep reinforcement learning : A practical perspective in path planning. Neurocomputing 2024, 608, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yang, Z.; Baar, T. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning: A Selective Overview of Theories and Algorithms. Springer, Cham 2021.

- Scaramuzza, D.; Kaufmann, E. Learning Agile, Vision-based Drone Flight: from Simulation to Reality 2023.

- Siwek, M. Consensus-Based Formation Control with Time Synchronization for a Decentralized Group of Mobile Robots. Sensors 2024, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G.; Yan, C.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z. Flexible multi-UAV formation control via integrating deep reinforcement learning and affine transformations. Aerospace Science and Technology 2025, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Wu, Y.; Peng, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, G. Multi-UAV maritime collaborative behavior modeling based on hierarchical deep reinforcement learning and DoDAF process mining. Aerospace Systems 2025, 8, 447–466. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Wu, D.; Huang, M.; Yuen, C. Graph Attention-based Reinforcement Learning for Trajectory Design and Resource Assignment in Multi-UAV Assisted Communication. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Wei, R. UAV Swarm Rounding Strategy Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning Goal Consistency with Multi-Head Soft Attention Algorithm. Drones 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.; Cui, H.; Wang, R. Short-range air combat maneuver decision of UAV swarm based on multi-agent Transformer introducing virtual objects. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Tao, C.; Su, Z.; Xu, Z.; Feng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y. Adaptive Missile Avoidance Algorithm for UAV Based on Multi-Head Attention Mechanism and Dual Population Confrontation Game. Drones 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization Algorithm Using Reference-Point-Based Nondominated Sorting Approach, Part I: Solving Problems With Box Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2014, 18, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, W. UAV Task Allocation for Hierarchical Multiobjective Optimization in Complex Conditions Using Modified NSGA-III with Segmented Encoding. Journal of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Science) 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, K.; Wu, G. AAV 3-D Path Planning Based on MOEA/D With Adaptive Areal Weight Adjustment. Aerospace and Electronic Systems, IEEE Transactions on 2025, 61, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, F. A Proactive Resource Allocation Algorithm for UAV-Assisted V2X Communication Based on Dynamic Multi-Objective Optimization. IEEE communications letters 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, B.; Qin, K. Global Energy Consumption Optimization for UAV Swarm Topology Shaping. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).