Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

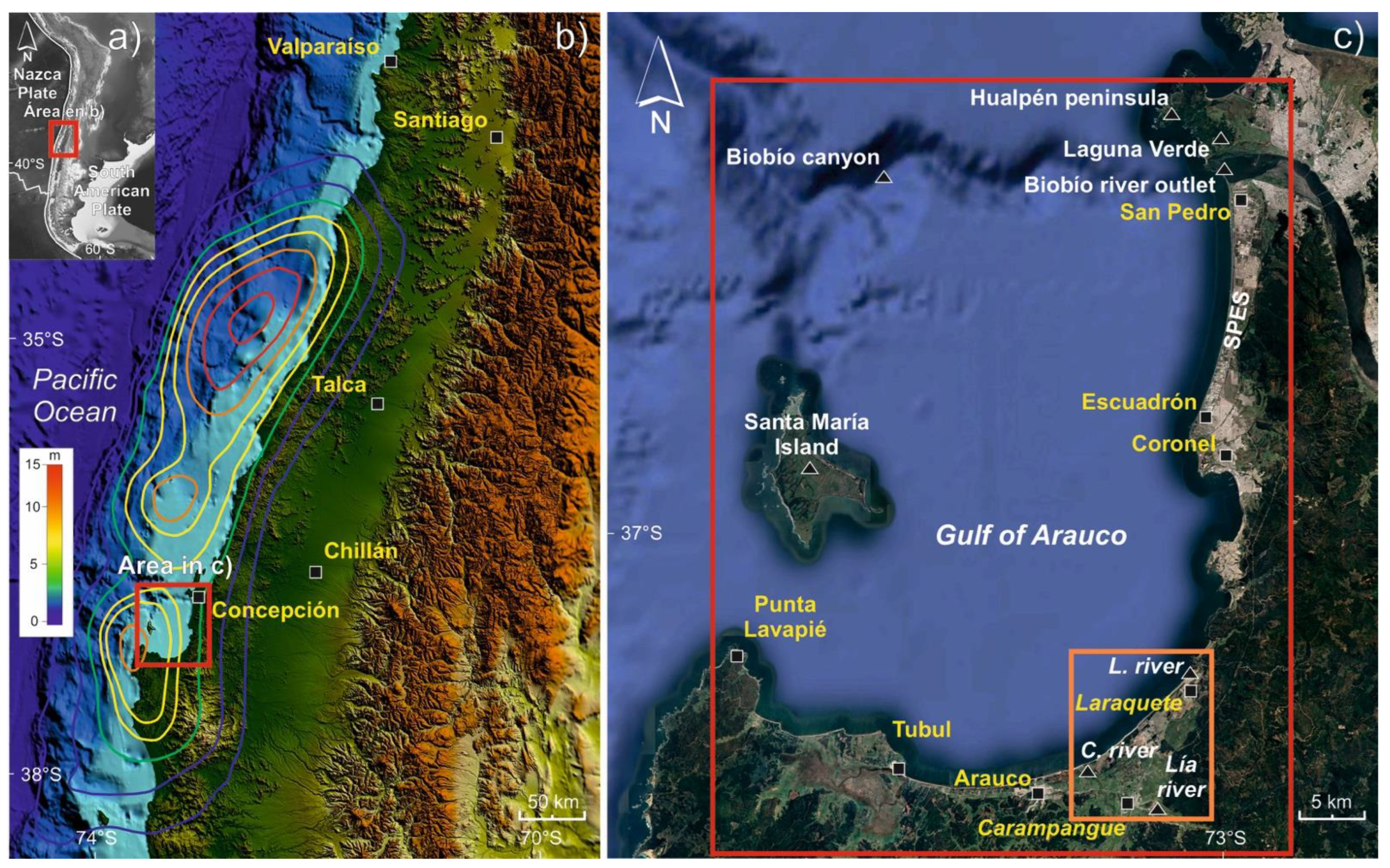

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. LiDAR Data and other Remote Sensing Data

3.1.2 GPR and Terrain Data Collection

4. Results

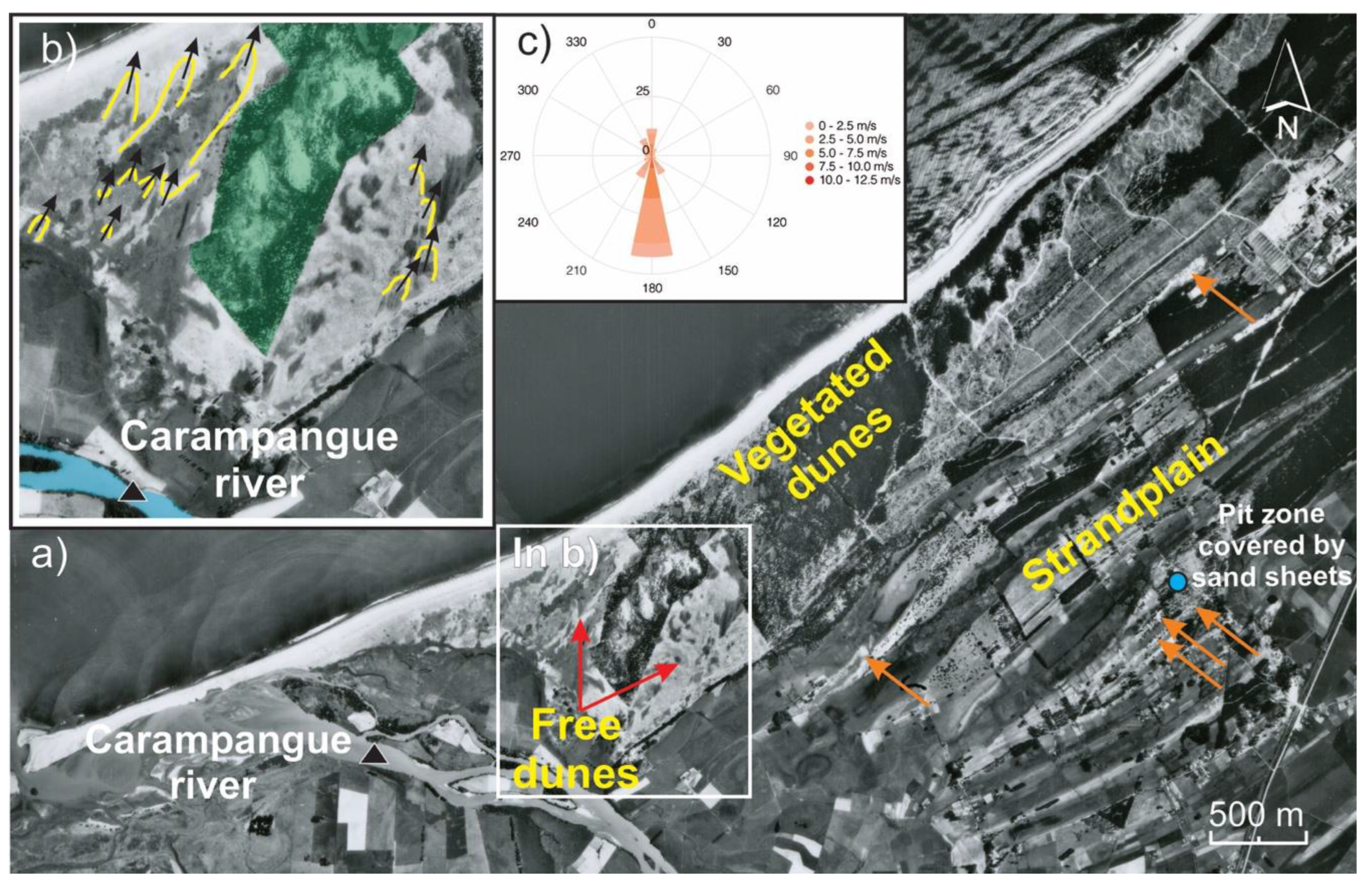

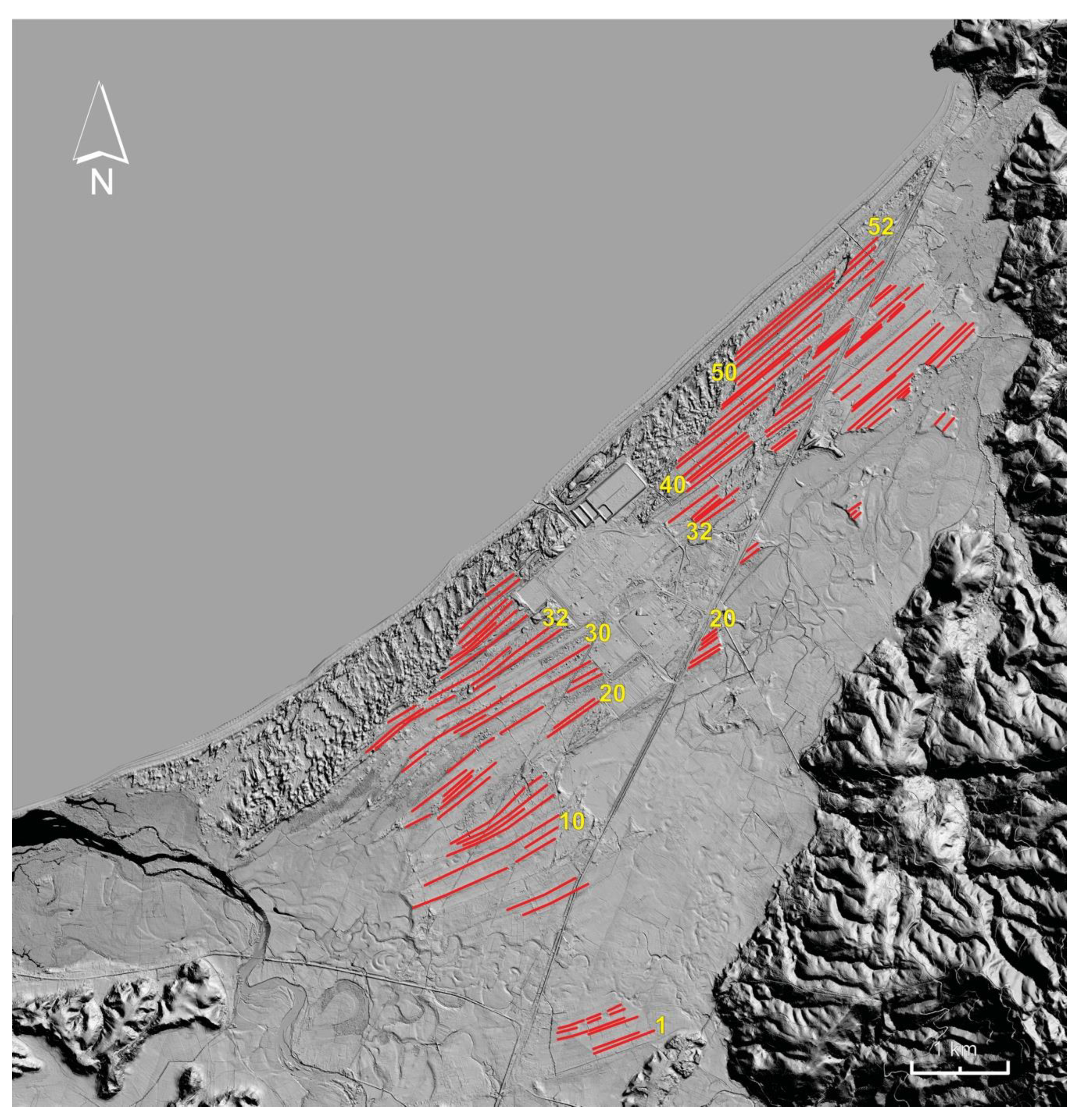

4.1. LCS Geomorphology Revealed by LiDAR Data

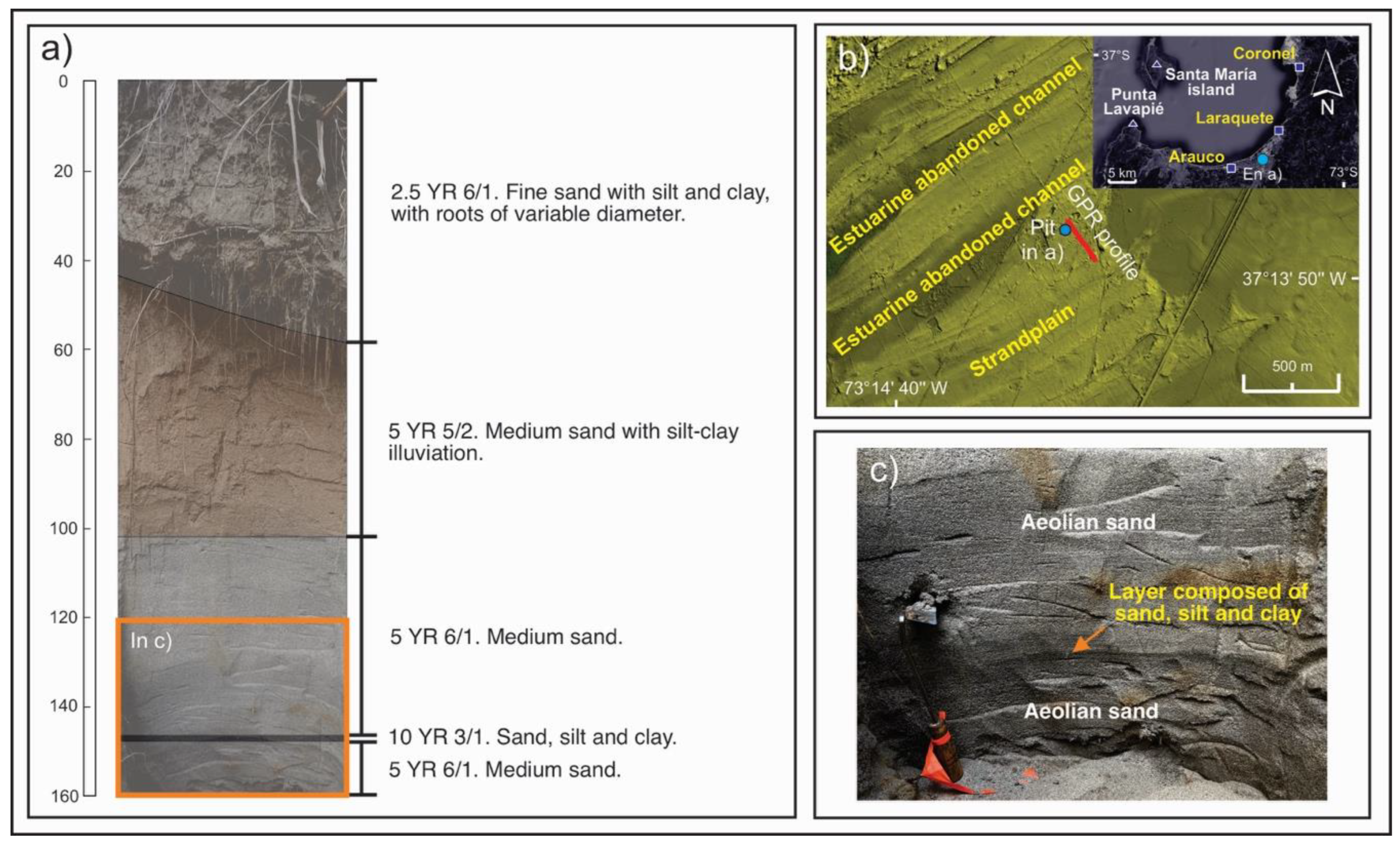

4.2. LCS stratigraphy Revealed by Radargrams Obtained from GPR Profiles

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Beach ridges count

Appendix B

Pit

References

- Roy, P.S.; Cowell, P.J.; Ferland, M.A.; Thom, B.G. Wave-dominated coasts. In Coastal evolution: Late Quaternary shoreline morphodynamics; 1994; pp. 121–186.

- Otvos, E.G. Beach Ridges — Definitions and Significance. Geomorphology 2000, 32, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Richards, J.; Pye, K. Sedimentology of coarse-clastic beach-ridge deposits, Essex, southeast England. Sediment Geol 2003, 162, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsela, M.A.; Daley, M.J.A.; Cowell, P.J. Origins of Holocene Coastal Strandplains in Southeast Australia: Shoreface Sand Supply Driven by Disequilibrium Morphology. Mar Geol 2016, 374, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenburg, S.R.; Hesp, P.A. Geology and Geomorphology of Holocene Coastal Barriers of Brazil; Springer Science & Business Media; Vol. 107;

- Oliver, T.S.N.; Tamura, T.; Brooke, B.P.; Short, A.D.; Kinsela, M.A.; Woodroffe, C.D.; Thom, B.G. Holocene Evolution of the Wave-Dominated Embayed Moruya Coastline, Southeastern Australia: Sediment Sources, Transport Rates and Alongshore Interconnectivity. Quat Sci Rev 2020, 247, 106566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, D.M.; Cleary, W.J.; Buynevich, I. V; Hein, C.J.; Klein, A.H.F.; Asp, N.; Angulo, R. Strandplain Evolution along the Southern Coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil. J Coast Res 2007, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Woodroffe, C.D. Coasts: form, process and evolution; Cambridge University Press.

- Scheffers, A.; Engel, M.; Scheffers, S.; Squire, P.; Kelletat, D. Beach Ridge Systems – Archives for Holocene Coastal Events? Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 2012, 36, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.R.; Manley, W.F. Holocene Coseismic and Aseismic Uplift of Isla Mocha, South-Central Chile. Quaternary International 1992, 15, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monecke, K.; Templeton, C.K.; Finger, W.; Houston, B.; Luthi, S.; McAdoo, B.G.; Sudrajat, S.U. Beach Ridge Patterns in West Aceh, Indonesia, and Their Response to Large Earthquakes along the Northern Sunda Trench. Quat Sci Rev 2015, 113, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Aedo, D.; Melnick, D.; Cisternas, M.; Brill, D. Tectonic Control on Great Earthquake Periodicity in South-Central Chile. Commun Earth Environ 2024, 5, 703. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, T. Beach Ridges and Prograded Beach Deposits as Palaeoenvironment Records. Earth Sci Rev 2012, 114, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hede, M.U.; Bendixen, M.; Clemmensen, L.B.; Kroon, A.; Nielsen, L. Joint Interpretation of Beach-Ridge Architecture and Coastal Topography Show the Validity of Sea-Level Markers Observed in Ground-Penetrating Radar Data. Holocene 2013, 23, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.; Klein, A.H.F.; Fetter-Filho, A.F.H.; Hein, C.J.; Méndez, F.J.; Broggio, M.F.; Dalinghaus, C. Climate-Induced Variability in South Atlantic Wave Direction over the Past Three Millennia. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 18553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FRASER, C.; HILL, P.R.; ALLARD, M. Morphology and Facies Architecture of a Falling Sea Level Strandplain, Umiujaq, Hudson Bay, Canada. Sedimentology 2005, 52, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HEIN, C.J.; FitzGERALD, D.M.; CLEARY, W.J.; ALBERNAZ, M.B.; De MENEZES, J.T.; KLEIN, A.H. da F. Evidence for a Transgressive Barrier within a Regressive Strandplain System: Implications for Complex Coastal Response to Environmental Change. Sedimentology 2013, 60, 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenburg, S.R.; Barboza, E.G.; Rosa, M.L.C.C.; Caron, F.; Sawakuchi, A.O. The Complex Prograded Cassino Barrier in Southern Brazil: Geological and Morphological Evolution and Records of Climatic, Oceanographic and Sea-Level Changes in the Last 7–6 Ka. Mar Geol 2017, 390, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, H.M.; Witter, R.C.; Engelhart, S.E.; Briggs, R.; Nelson, A.; Haeussler, P.; Corbett, D.R. Beach Ridges as Paleoseismic Indicators of Abrupt Coastal Subsidence during Subduction Zone Earthquakes, and Implications for Alaska-Aleutian Subduction Zone Paleoseismology, Southeast Coast of the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. Quat Sci Rev 2015, 113, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, S.J.; Jol, H.M.; Shulmeister, J.; Hart, D.E. Storm Response of a Mixed Sand Gravel Beach Ridge Plain under Falling Relative Sea Levels: A Stratigraphic Investigation Using Ground Penetrating Radar. Earth Surf Process Landf 2019, 44, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.; Loveson, V.J.; Kumar, V.; Shukla, A.D.; Chandra, P.; Verma, S.; Yadav, R.; Magotra, R.; Tirodkar, G.M. Reconstruction of Holocene Relative Sea-Level from Beach Ridges of the Central West Coast of India Using GPR and OSL Dating. Geomorphology 2023, 442, 108914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aedo, D.; Cisternas, M.; Melnick, D.; Esparza, C.; Winckler, P.; Saldaña, B. Decadal Coastal Evolution Spanning the 2010 Maule Earthquake at Isla Santa Maria, Chile: Framing Darwin’s Accounts of Uplift over a Seismic Cycle. Earth Surf Process Landf 2023, 48, 2319–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.; Clemmensen, L.B. Sea-level Markers Identified in Ground-penetrating Radar Data Collected across a Modern Beach Ridge System in a Microtidal Regime. Terra Nova 2009, 21, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, L.B.; Nielsen, L. Internal Architecture of a Raised Beach Ridge System (Anholt, Denmark) Resolved by Ground-Penetrating Radar Investigations. Sediment Geol 2010, 223, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas, S.; Ferreira, Ó.; Plomaritis, T.A.; Leorri, E. Coastal Barrier Stratigraphy for Holocene High-Resolution Sea-Level Reconstruction. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 38726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, T.B.; Fernandez, G.B.; de Oliveira Peixoto, M.N. Applications of Ground-Penetrating Radar to Investigate the Quaternary Evolution of the South Part of the Paraiba Do Sul River Delta (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). J Coast Res 2013, 65, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinegina, T.K.; Bourgeois, J.; Bazanova, L.I.; Zelenin, E.A.; Krasheninnikov, S.P.; Portnyagin, M. V Coseismic Coastal Subsidence Associated with Unusually Wide Rupture of Prehistoric Earthquakes on the Kamchatka Subduction Zone: A Record in Buried Erosional Scarps and Tsunami Deposits. Quat Sci Rev 2020, 233, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Santalla, I.; Gomez-Ortiz, D.; Martín-Crespo, T.; Sánchez, M.J.; Montoya-Montes, I.; Martín-Velázquez, S.; Barrio, F.; Serra, J.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Gracia, F.J. Study and Evolution of the Dune Field of La Banya Spit in Ebro Delta (Spain) Using LiDAR Data and GPR. Remote Sensing 2021, Vol. 13, Page 802 2021, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, B.P.; Huang, Z.; Nicholas, W.A.; Oliver, T.S.N.; Tamura, T.; Woodroffe, C.D.; Nichol, S.L. Relative Sea-Level Records Preserved in Holocene Beach-Ridge Strandplains – An Example from Tropical Northeastern Australia. Mar Geol 2019, 411, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarletta, D.J.; Shawler, J.L.; Tenebruso, C.; Hein, C.J.; Lorenzo-Trueba, J. Reconstructing Coastal Sediment Budgets From Beach- and Foredune-Ridge Morphology: A Coupled Field and Modeling Approach. J Geophys Res Earth Surf 2019, 124, 1398–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Oliver, T.S.N.; Cunningham, A.C.; Woodroffe, C.D. Recurrence of Extreme Coastal Erosion in SE Australia Beyond Historical Timescales Inferred From Beach Ridge Morphostratigraphy. Geophys Res Lett 2019, 46, 4705–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switzer, A.D.; Gouramanis, C.; Bristow, C.S.; Simms, A.R. Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) in Coastal Hazard Studies. In Geological Records of Tsunamis and other Extreme Waves; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 143–168.

- Doyle, T.B.; Woodroffe, C.D. The Application of LiDAR to Investigate Foredune Morphology and Vegetation. Geomorphology 2018, 303, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.J.; Young, A.P.; Ashford, S.A. TopCAT—Topographical Compartment Analysis Tool to Analyze Seacliff and Beach Change in GIS. Comput Geosci 2012, 45, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermann, D.; Klotz, J.; Reigber, C. Space-Geodetic Estimation of the Nazca-South America Euler Vector. Earth Planet Sci Lett 171, 329–334.

- Davis, R.A. 10.16 Evolution of Coastal Landforms. Treatise on Geomorphology 2013, 10, 417–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya-Vergara, J.F. Análisis de La Localización de Los Procesos y Formas Predominantes de La Linea Litoral de Chile: Observación Preliminar. Investigaciones Geográficas: Una mirada desde el sur 1982, 29, g–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, M.F.; Moyano-Paz, D.; FitzGerald, D.M.; Simontacchi, L.; Veiga, G.D. Contrasting Beach-Ridge Systems in Different Types of Coastal Settings. Earth Surf Process Landf 2023, 48, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, F.I.; Flory, J.Q.; Martínez, C.; Fernández, A.; Jaque, E. The evolution of the bío bío delta and the coastal plains of the Arauco Gulf, bío bío region: the holocene sea-level Curve of Chile. J Coast Res 2012, 28, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Muñoz, J.; Melnick, D.; Zambrano, P.; Rietbrock, A.; González, J.; Argandoña, B.; Strecker, M.R. Quantifying Offshore Fore-arc Deformation and Splay-fault Slip Using Drowned Pleistocene Shorelines, Arauco Bay, Chile. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 2017, 122, 4529–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick, D.; Bookhagen, B.; Strecker, M.R.; Echtler, H.P. Segmentation of Megathrust Rupture Zones from Fore-arc Deformation Patterns over Hundreds to Millions of Years, Arauco Peninsula, Chile. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, E.; Melnick, D.; Dura, T.; Cisternas, M.; Ely, L.L.; Wesson, R.L.; Whitehouse, P.L. Holocene Relative Sea-Level Change along the Tectonically Active Chilean Coast. Quat Sci Rev 2020, 236, 106281. [Google Scholar]

- Winckler, P.; Martín, R.A.; Esparza, C.; Melo, O.; Sactic, M.I.; Martínez, C. Projections of Beach Erosion and Associated Costs in Chile. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoener, G.; Muñoz, E.; Arumí, J.L.; Stone, M.C. Impacts of Climate Change Induced Sea Level Rise, Flow Increase and Vegetation Encroachment on Flood Hazard in the Biobío River, Chile. Water (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, F.; Hebbeln, D.; Wefer, G. High-Resolution Marine Record of Climatic Change in Mid-Latitude Chile during the Last 28,000 Years Based on Terrigenous Sediment Parameters. Quat Res 1999, 51, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, F.; Hebbeln, D.; Röhl, U.; Wefer, G. Holocene Rainfall Variability in Southern Chile: A Marine Record of Latitudinal Shifts of the Southern Westerlies. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2001, 185, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, B.; Valero-Garcés, B.L.; Urrutia, R.; Kelts, K.; Veit, H.; Appleby, P.G.; Geyh, M. Moisture Changes and Fluctuations of the Westerlies in Mediterranean Central Chile during the Last 2000 Years: The Laguna Aculeo Record (33 50′ S. Quaternary International 2002, 87, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Martínez, R.; Villagrán, C.; Jenny, B. The Last 7500 Cal Yr BP of Westerly Rainfall in Central Chile Inferred from a High-Resolution Pollen Record from Laguna Aculeo. Quat Res 2003, 60, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterken, M.; Verleyen, E.; Sabbe, K.; Terryn, G.; Charlet, F.; Bertrand, S.; Vyverman, W. Late Quaternary Climatic Changes in Southern Chile, as Recorded in a Diatom Sequence of Lago Puyehue (40 40′ S. J Paleolimnol 2008, 39, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frugone-Álvarez, M.; Latorre, C.; Giralt, S.; Polanco-Martínez, J.; Bernárdez, P.; Oliva-Urcia, B.; Valero-Garcés, B. A 7000-year High-resolution Lake Sediment Record from Coastal Central Chile (Lago Vichuquén, 34° S): Implications for Past Sea Level and Environmental Variability. J Quat Sci 2017, 32, 830–844. [Google Scholar]

- Francois, J.P.; Hernandez, P.; Schneider, I.; Cerda, J. Nuevos datos en torno a la historia paleoambiental del centro-sur de Chile. El registro sedimentario y palinológico del Humedal Laguna Verde (36°47’S), Península Hualpén, Región del Bío-Bío, Chile. Revista De Geografía Norte Grande 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, F.; Kilian, R.; Arz, H.W.; Francois, J.P.; Kaiser, J.; Prange, M.; Steinke, T. Holocene Changes in the Position and Intensity of the Southern Westerly Wind Belt. Nat Geosci 2010, 3, 695–699. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.; Melnick, D.; Rosenau, M.; Baez, J.; Klotz, J.; Oncken, O.; Hase, H. Toward Understanding Tectonic Control on the Mw 8.8 2010 Maule Chile Earthquake. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2012, 321, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.N.N.; Sladen, A.; Ortega-Culaciati, F.; Simons, M.; Avouac, J.P.; Fielding, E.J.; Socquet, A. Coseismic and Postseismic Slip Associated with the 2010 Maule Earthquake, Chile: Characterizing the Arauco Peninsula Barrier Effect. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 2013, 118, 3142–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick, D.; Cisternas, M.; Moreno, M.; Norambuena, R. Estimating Coseismic Coastal Uplift with an Intertidal Mussel: Calibration for the 2010 Maule Chile Earthquake (Mw= 8.8. Quat Sci Rev 2012, 42, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada, J.; Jaque, E.; Fernández, A.; Vásquez, D. Cambios en el relieve generados como consecuencia del terremoto Mw= 8,8 del 27 de febrero de 2010 en el centro-sur de Chile. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande 2012, 53, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, C.; Rojas, D.; Quezada, M.; Quezada, J.; Oliva, R. Post-Earthquake Coastal Evolution and Recovery of an Embayed Beach in Central-Southern Chile. Geomorphology 2015, 250, 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cisternas, M.; Melnick, D.; Ely, L.; Wesson, R.; Norambuena, R. Similarities between the Great Chilean Earthquakes of 1835 and 2010. In Proceedings of the Chapman Conference on Giant Earthquakes and their Tsunamis, AGU; 2010; Vol. 19.

- Moreno, M.; Rosenau, M.; Oncken, O. 2010 Maule Earthquake Slip Correlates with Pre-Seismic Locking of Andean Subduction Zone. Nature 2010, 467, 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzroy, R. Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle Between the Years 1826 and 1836: Describing Their Examination of the Southern Shores of South America. In Proceedings of the and the Beagle’s Circumnavigation of the Globe: Proceedings of the Second Expedition; 1839.

- Giorgini, E.; Orellana, F.; Arratia, C.; Tavasci, L.; Montalva, G.; Moreno, M.; Gandolfi, S. InSAR Monitoring Using Persistent Scatterer Interferometry (PSI) and Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) Techniques for Ground Deformation Measurement in Metropolitan Area of Concepción, Chile. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesson, R.L.; Melnick, D.; Cisternas, M.; Moreno, M.; Ely, L.L. Vertical Deformation through a Complete Seismic Cycle at Isla Santa María, Chile. Nat Geosci 2015, 8, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Villagrán, M.; Gómez, M.; Martínez, C. Coastal Erosion and a Characterization of the Morphological Dynamics of Arauco Gulf Beaches under Dominant Wave Conditions. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanis, A. MATGPR Release 2: A Freeware MATLAB ® Package for the Analysis & Interpretation of Common & Single Offset GPR Data. Geophysical Research Abstracts 2010, 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bristow, C.S.; Neil Chroston, P.; Bailey, S.D. The Structure and Development of Foredunes on a Locally Prograding Coast: Insights from Ground-Penetrating Radar Surveys, Norfolk, UK. Sedimentology 2000, 47, 923–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.S.; Dougherty, A.J.; Gliganic, L.A.; Woodroffe, C.D. Towards More Robust Chronologies of Coastal Progradation: Optically Stimulated Luminescence Ages for the Coastal Plain at Moruya, South-Eastern Australia. 2014, 25, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, C.J.; Fitzgerald, D.M.; De Souza, L.H.P.; Georgiou, I.Y.; Buynevich, I. V.; Klein, A.H.D.F.; De Menezes, J.T.; Cleary, W.J.; Scolaro, T.L. Complex Coastal Change in Response to Autogenic Basin Infilling: An Example from a Sub-Tropical Holocene Strandplain. Sedimentology 2016, 63, 1362–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, B.P.; Huang, Z.; Nicholas, W.A.; Oliver, T.S.N.; Tamura, T.; Woodroffe, C.D.; Nichol, S.L. Relative Sea-Level Records Preserved in Holocene Beach-Ridge Strandplains – An Example from Tropical Northeastern Australia. Mar Geol 2019, 411, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribolini, A.; Bertoni, D.; Bini, M.; Sarti, G. Ground-Penetrating Radar Prospections to Image the Inner Structure of Coastal Dunes at Sites Characterized by Erosion and Accretion (Northern Tuscany, Italy. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11260. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Santalla, I.; Gomez-Ortiz, D.; Martín-Crespo, T.; Sánchez, M.J.; Montoya-Montes, I.; Martín-Velázquez, S.; Barrio, F.; Serra, J.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Gracia, F.J. Study and Evolution of the Dune Field of La Banya Spit in Ebro Delta (Spain) Using Lidar Data and Gpr. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Figueiredo, M.; Rocha, T.; Brill, D.; Borges Fernandez, G. Morphostratigraphy of Barrier Spits and Beach Ridges at the East Margin of Salgada Lagoon (Southeast Brazil. J South Am Earth Sci 2022, 116, 103850. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, P.; Loveson, V.J.; Kumar, V.; Shukla, A.D.; Chandra, P.; Verma, S.; Yadav, R.; Magotra, R.; Tirodkar, G.M. Reconstruction of Holocene Relative Sea-Level from Beach Ridges of the Central West Coast of India Using GPR and OSL Dating. Geomorphology 2023, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanucci, F.; Amore, C.; Pineda, V. Characteristics and Dynamics of the Coasts in the Araugo Gulf (Central Chile). In Proceedings of the Bollettino di oceanologia teorica ed applicata; 1992; Vol. 10, pp. 265–271. 1992; Vol. 10.

- Flores-Aqueveque, V.; Arias, P.A.; Gómez-Fontealba, C.; González-Arango, C.; Apaestegui, J.; Evangelista, H.; Guerra, L.; Latorre, C. The South American Climate During the Last Two Millennia. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Oxford University Press, 2024.

- Hein, C.J.; Fitzgerald, D.M.; Cleary, W.J.; Albernaz, M.B.; De Menezes, J.T.; Klein, A.H. da F. Evidence for a Transgressive Barrier within a Regressive Strandplain System: Implications for Complex Coastal Response to Environmental Change. Sedimentology 2013, 60, 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, K.; Tsoar, H. Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes. Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, F. Las dunas del centro de Chile. Edición de la Pontifica Universidad Católica de Chile; Biblioteca Fundamentos de la Construcción de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, S.; Boës, X.; Castiaux, J.; Charlet, F.; Urrutia, R.; Espinoza, C.; Fagel, N. Temporal Evolution of Sediment Supply in Lago Puyehue (Southern Chile) during the Last 600 Yr and Its Climatic Significance. Quat Res 2005, 64, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lamy, F.; Kaiser, J.; Lamy, F. Glacial to Holocene Paleoceanographic and Continental Paleoclimate Reconstructions Based on ODP Site 1233/GeoB 3313 Off Southern Chile. 2009, 129–156. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).