Introduction

Coastal dune evolution and morphology is driven by a range of factors including sand supply, vegetation type and cover, wave and wind forces, storm erosion, and increasingly by anthropogenic modification (Hesp 2002). Foredune stability is influenced by storm magnitude and frequency, which drive fine-scale variations in erosion, inundation, and sediment transport (Oliver et al. 2024), as well as shifts in wave climate that can disrupt longshore sediment pathways (Goodwin et al. 2016). Additionally, anthropogenic modifications to foredunes and vegetation can impact shoreline stability and morphology, often necessitating ongoing maintenance and management (Doyle & Woodroffe 2023). Manipulations of foredunes have occurred globally (Bastos et al. 2024; Bossard & Nicolae Lerma 2020) typically as a control to establish a new stable state. However, coasts are dynamic, and monitoring data is required to assess the effectiveness of the manipulation. Three-dimensional high-resolution spatial data, such as LiDAR, is crucial for characterising the morphodynamics of modified foredunes, while integrating nearshore wave data supports understanding the impact of storm events and post-event recovery and the capacity to maintain a new modified stable state. This study examines foredune morphodynamics at Woonona-Bellambi Beach in New South Wales (NSW), southeastern Australia, over a decade following intervention works (Gangaiya et al. 2017). The aim is to evaluate and identify foredune responses to storms and soft engineering modification over annual to decadal timescales using topographic and nearshore wave data. The findings contribute to a better understanding of storm impacts and modification effects, supporting the development of quantitative sediment budgets for coastal compartments.

Study Location

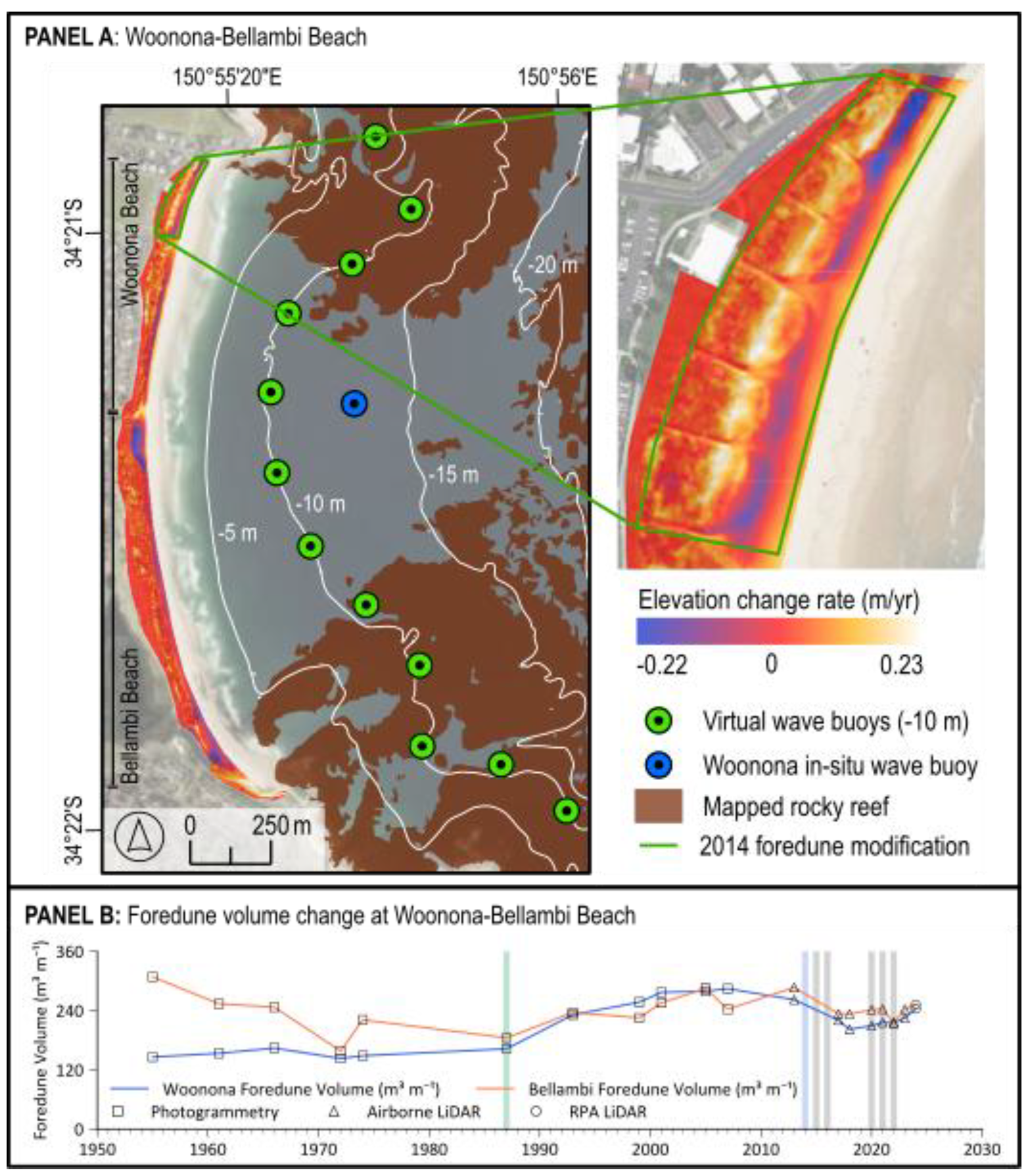

Woonona-Bellambi Beach (-34.35, 150.92,

Figure 1A) is a highly modified and managed beach and foredune system with urban development and infrastructure backing the northern foredune (i.e. Woonona Beach), a stormwater creek entrance in the middle, and Bellambi Lagoon backing Bellambi Beach at the southern end. It is a 2 km long sandy beach with an easterly aspect and a shoreface dominated by rocky reef substrate and limited sediment sharing. This region of the Australian coast is wave-dominated with a deepwater mean H

s of 1.6 m, T

p of 9.6 s with swells predominantly from the south-east (Kinsela

et al. 2022). It has a semi-diurnal micro-tidal regime with a range of 0.8 m neap tide to 1.2 m spring tide. Extra-tropical cyclones known as East Coast Lows (ECLs) are the dominant source of extreme wave conditions leading to coastal inundation, elevated sea levels and heavy rainfall (Harley

et al. 2017).

Engineering works aimed at enhancing recreational amenity and improving coastal resilience in the 1980s included installing fencing, planting dune vegetation, and shaping frontal areas of the foredunes. At Woonona Beach, these efforts stabilised the previously sparsely vegetated northern foredunes by 1993 which then prograded and vegetation expanded seaward eventually causing community concerns regarding amenity and safety. In response, soft engineering modification works in 2014 included the removal of vegetation, re-profiling of a 250 m section of the northern dune-beach area and the establishment of a new vegetation line 30 m landward. Within 8 months, an incipient dune formed, and within 21 months, some areas had accreted more than the removed volume, and the lower beach width gained had diminished (Gangaiya et al. 2017).

Materials and Methods

Foredune Geomorphic Change Analysis

Volumes for the Woonona and Bellambi foredunes were measured using triangulated irregular network (TIN) surface models derived from photogrammetric data (1958–2007), aircraft LiDAR (2013–2023), and remote piloted aircraft LiDAR data collected specifically for this research in 2024 (

Figure 1B). An area of interest (AoI) polygon was drawn to define the foredune extent, including any incipient dunes, for each year of survey data. Volumes were measured using 20 m spaced, 1 m wide transects for north-south comparison (Doyle & Woodroffe 2018). Digital elevation models were generated using ground-classified returns from point clouds derived from LiDAR surveys conducted between 2013 and 2024 (8 in total). A pixel-wise linear regression analysis was then performed to create a surface model of elevation rates of change along the foredune.

Coastal Storm Events Analysis

Wave data was sourced through the NSW Nearshore Wave Tool which provides modelled nearshore wave data using WAVEWATCH III (NOAA, USA) at 250 m spaced virtual nodes for 10 m and 30 m depth contours (Baird 2024). The tool was developed using in-situ wave buoy observations at 20 locations, including a buoy at Woonona Beach, from shallow waters (<35 m) in southeast Australia (Kinsela

et al. 2024) and provides hindcast data from 1958 to July 2024. At the 10 m depth contour, 12 nodes covered waves arriving along the Woonona-Bellambi embayment (

Figure 1A).

Coastal storm events were defined using the peak-over-threshold method (Harley 2017) with the NSW threshold values (Shand et al. 2011); wave height (Hthresh) ≥ 3.0 m; minimum storm duration (Dstorm) ≥ 6 h; and the meteorological independence criterion (I) of 24 h. For storm events between 2014 and 2024, the mean and maximum Hs, Tp, and predominant wave direction were calculated using averaged 10 m depth virtual wave buoy data.

Wind analysis was conducted using 1997 to 2023 data from the Bellambi AWS weather station (-34.37, 150.93) provided by the Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Rainfall totals for 24-hour periods for each coastal storm were calculated using Bellambi AWS data. Sea level maxima were determined using tidal data from the Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology Port Kembla station (-34.47, 150.91) for each coastal storm period.

Results

Foredune Geomorphic Change

Linear regression analyses of elevation changes indicated spatial variability within the complex foredune system (

Figure 1A), as indicated by a relatively low overall R

2 of 0.25. In the section of the Woonona Beach foredune modified in 2014, a decrease in elevation is observed along the foredune front, coinciding with a more peaked dune crest immediately landward. In the unmodified section of the Woonona Beach foredune, elevation decreases are evident along the foredune front. The most prominent elevation losses occur near the mouth of the stormwater creek near the centre of the embayment, where scarping and sand losses are evident. At the southern extent, elevation increases are observed along the foredune, and near the gully outlet channel, which shows signs of migration.

The Woonona-Bellambi Beach foredune was classified as a generally stable to slightly prograding system over multidecadal timescales (

Figure 1B). A decrease in elevation occurred along both the Woonona and Bellambi foredunes between 2013 and 2017. From 2018 onward, the entire foredune increased in volume, though recovery was interrupted in 2022 and a volume decrease occurred in the Bellambi foredune. The trends suggest continued recovery, with volumes approaching levels comparable to those estimated for 2013.

Coastal Storm Events

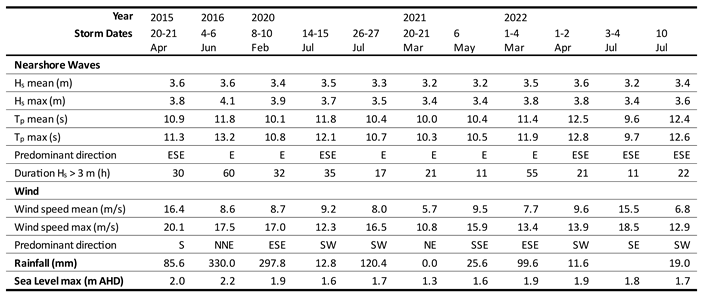

A total of 11 storm events met the coastal storm thresholds at Woonona-Bellambi Beach over the focal study period (2013 to 2024) (

Table 1). The 2016 storm (4-6 June) featured the highest significant wave height (H

s max of 4.1 m), the most rainfall (330 mm), the highest sea level (2.2 m AHD), and a long duration (60 hours). Notably, the north-northeast wind direction aligned closely with the easterly wave direction and was observed from the northeast in other areas of NSW (Harley

et al. 2017). In contrast, the 1-4 March and 3-4 July storms of 2022 also exhibited close alignment between wave and wind directions but lacked a northerly wind component, which is more typical for the region. The 2022 storm series also featured considerable rainfall.

Discussion

The foredune system at Woonona-Bellambi Beach appears relatively stable over multidecadal timescales, with episodic storm cut and recovery. Soft engineering of the Woonona Beach foredune resulted in morphological changes over the following years and decade, including a landward increase in height and a higher dune crest, indicating sediment transfer from the front of the foredune as the re-profiled sand volume returned. This longer-term trend of increasing volume and geomorphic change appears to be a continuation of the trends observed in the 21 months following the modification works in which immediate volume increases where observed (Gangaiya et al. 2017). A landward shift or higher dune crest was not observed along the unmodified Woonona foredune, despite volume increases after 2018. Changes in elevation rate and volume suggest natural processes as key drivers of erosion and recovery, resulting in a morphology distinct from the modified foredune.

The timing, magnitude and extent of volume reductions observed across the entire foredune between 2013 to 2017 indicate the 2016 storm was a significant driver of erosion. This is consistent with other studies detailing the extreme erosion particularly at the southern end of NSW beaches due to large waves, anomalous wind/wave directions, and coincidence with spring high tides (Harley et al. 2017). Along the Bellambi foredune, elevation losses at the stormwater creek mouth near the centre of the embayment were likely driven by high rainfall events. These impacts are potentially exacerbated by urban runoff directed through the creek as similar erosion is not observed at the southern extent, where the unconstrained channel disperses gully overflow.

Specific combinations of storm wave direction, wind direction, and water level are known to modify coastal erosion, cause considerable spatial variability and result in extreme impacts such as foredune overtopping and erosion (Oliver et al. 2024). This study emphasises the spatial and temporal diversity of foredune change in response to an array of potential drivers, or their combinations, including storm wave direction, wind direction, water levels, and rainfall. It also illustrates the complexity and scale of natural drivers, the dominance of natural variability over anthropogenic modifications on annual to decadal timescales and demonstrates the importance of working with nature and understanding natural patterns.

This analysis highlights the value of high-frequency and high-resolution monitoring data to improve understanding foredune responses to large-scale natural and anthropogenic changes over annual to decadal timescales. Combining this information with nearshore wave data further improves understanding of wave processes, storm impacts, and post-storm recovery. Integrating other monitoring data will continue to fill the gaps to develop comprehensive sediment budgets and create adaptable methods to improve coastal management in a changing climate.

References

- Baird 2024, NSW Nearshore Wave Tool – Validation Report, Sydney, Australia.

- Bastos, AP, Taborda, R, Andrade, C, Ponte Lira, C & Nobre Silva, A 2024, ‘Short-Term Foredune Dynamics in Response to Invasive Vegetation Control Actions’, Remote Sensing, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 1487. [CrossRef]

- Bossard, V & Nicolae Lerma, A 2020, ‘Geomorphologic characteristics and evolution of managed dunes on the South West Coast of France’, Geomorphology, vol. 367, p. 107312. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, TB & Woodroffe, CD 2018, ‘The application of LiDAR to investigate foredune morphology and vegetation’, Geomorphology, vol. 303, pp. 106-121. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, TB & Woodroffe, CD 2023, ‘Modified foredune eco-morphology in southeast Australia’, Ocean & Coastal Management, vol. 240, p. 106640. [CrossRef]

- Gangaiya, P, Beardsmore, A & Miskiewicz, T 2017, ‘Morphological changes following vegetation removal and foredune re-profiling at Woonona Beach, New South Wales, Australia’, Ocean & Coastal Management, vol. 146, pp. 15-25.

- Goodwin, ID, Mortlock, TR & Browning, S 2016, ‘Tropical and extratropical-origin storm wave types and their influence on the East Australian longshore sand transport system under a changing climate’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, vol. 121, no. 7, pp. 4833-4853. [CrossRef]

- Harley, M 2017, ‘Coastal Storm Definition’, in G Coco & P Ciavola (eds), Coastal Storms: Processes and Impacts, Wiley Blackwell, pp. 1-21.

- Harley, MD, Turner, IL, Kinsela, MA, Middleton, JH, Mumford, PJ, Splinter, KD, Phillips, MS, Simmons, JA, Hanslow, DJ & Short, AD 2017, ‘Extreme coastal erosion enhanced by anomalous extratropical storm wave direction’, Scientific Reports, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 6033. [CrossRef]

- Hesp, P 2002, ‘Foredunes and blowouts: initiation, geomorphology and dynamics’, Geomorphology, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 245-268.

- Kinsela, MA, Hanslow, DJ, Carvalho, RC, Linklater, M, Ingleton, TC, Morris, BD, Allen, KM, Sutherland, MD & Woodroffe, CD 2022, ‘Mapping the Shoreface of Coastal Sediment Compartments to Improve Shoreline Change Forecasts in New South Wales, Australia’, Estuaries and Coasts, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 1143-1169. [CrossRef]

- Kinsela, MA, Morris, BD, Ingleton, TC, Doyle, TB, Sutherland, MD, Doszpot, NE, Miller, JJ, Holtznagel, SF, Harley, MD & Hanslow, DJ 2024, ‘Nearshore wave buoy data from southeastern Australia for coastal research and management’, Scientific Data, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 190. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, TSN, Kinsela, MA, Doyle, TB & McLean, RF 2024, ‘Foredune erosion, overtopping and destruction in 2022 at Bengello Beach, southeastern Australia’, Cambridge Prisms: Coastal Futures, vol. 2, pp. 1-20.

- Shand, T, Goodwin, I, Mole, M, Carley, J, Browning, S, Coghlan, I, Harley, M & Peirson, W 2011, NSW coastal inundation hazard study: coastal storms and extreme waves, Sydney, Australia.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).