1. Introduction

Coastal environments form the dynamic interface between land and sea, hosting essential ecosystems, infrastructure, and nearly 40% of the global population [

1,

2]. These areas are increasingly exposed to natural and anthropogenic pressures, with coastal erosion being a prominent concern [

3,

4]. Coastal areas, due to their socio-economic and environmental importance, face global challenges associated with erosion, which impacts sandy coastlines across various regions [

5,

6]. It is estimated that approximately 70% of the world’s sandy beaches are experiencing erosion [

7], resulting from complex interactions among climatic, oceanographic, and human-induced factors.

Erosive dynamics result from natural processes such as wave action, tides, beach slope, sediment supply, and sea level rise, often intensified by human activities, such as coastal engineering, land-use changes, and uncontrolled urban expansion [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Consequently, the net loss of sediment along the beach profile, referred to as erosion [

12], can lead to significant morphological transformations in these environments [

13], threatening local ecosystems [

14], infrastructure, and socio-economic activities, including tourism [

15,

16]. Storms, among natural forces, are particularly significant, often causing both short- and long-term sediment displacement. In severe cases, these events may lead to permanent alterations in the coastal landscape [

17,

18,

19]. In addition, unplanned occupation and environmental degradation have contributed to the loss of dunes, mangroves, and built infrastructure [

20,

21].

To assess coastal vulnerability, various indices have been developed globally [

22,

23,

24]. These indices make it possible to identify, quantify, and classify coastal environments based on their varying degrees of vulnerability. One of the most widely applied is the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI), which was initially introduced by [

25]. It integrates physical, geomorphological, and socio-environmental parameters to assess the susceptibility of coastlines to hazards such as sea-level rise, storms, and erosion [

26,

27]. Based on this, the present study adapts the CVI approach to the unique conditions of Amazonian beaches, which are shaped by powerful physical forces and increasing anthropogenic pressures [

28,

29].

The objective of this work is to provide a comprehensive assessment of beach vulnerability across distinct climatic contexts along the Amazonian coast, supporting effective management of natural resources and coastal development. Although focused on Pará state, the methods and findings presented here may inform similar efforts in other dynamic coastal settings.

2. Study Area: The Amazon Coast

2.1. Overview of the Amazon Coast

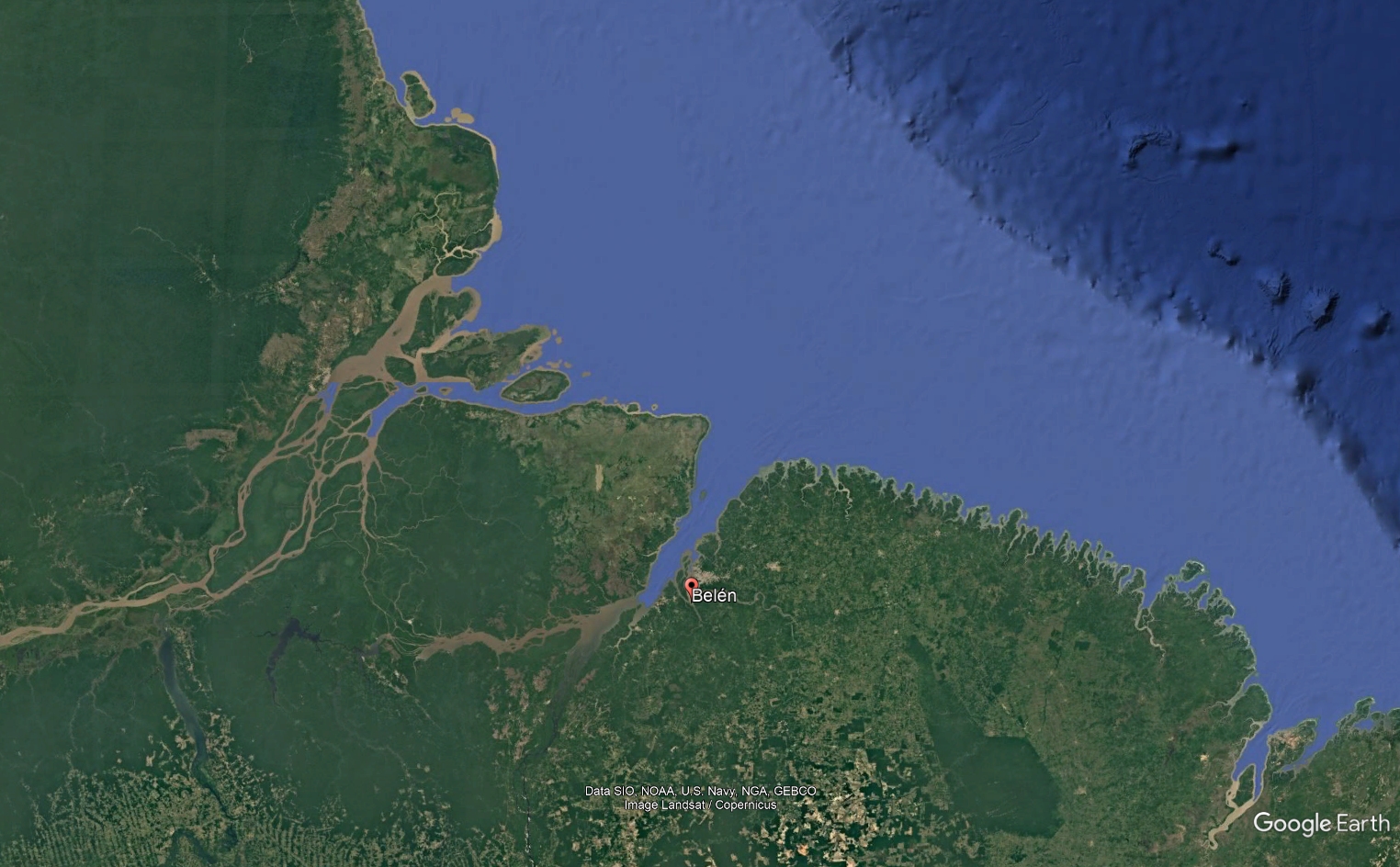

The Brazilian Amazon coast is a vast and dynamic estuarine–marine system shaped by abundant sediment inputs reworked by both fluvial and coastal processes [

29,

30,

31]. Stretching between 4°N and 4°S, this coastal zone represents about 35% of Brazil’s 8,500 km-long shoreline [

32]. It includes the immense sediment, nutrient, and organic matter discharge of the Amazon River (

Figure 1), which alone contributes nearly 20% of global river discharge (~200,000 m³ s

-1 on average) and an estimated 754 × 10⁶ tons of suspended sediments per year [

33,

34,

35]. Although bedload constitutes only about 1% of the discharge, it accounts for millions of tons annually [

36] and sustains extensive sandy beaches and tidal sandflats.

The coastline is dominated by mangroves and comprises various features such as tidal flats, salt marshes, cheniers, beach ridges, deltas, and coastal dunes, making up one of the world’s largest mangrove ecosystems [

37,

38]. Located in a low-latitude region, the Coriolis effect is minimal, making coastal circulation primarily driven by river discharge, prevailing winds, wave action, and meso- to megatidal regimes that create intense tidal currents [

29,

30].

2.2. Geomorphological Setting and Offshore Conditions

From a geomorphological perspective, the Pará coast is divided into two primary zones [

39]: (a) the emergent coast, represented by Marajó Island with a relatively straight shoreline, and (b) the submergent coast, extending between Marajó and Gurupi Bays and characterized by a more irregular, dissected landscape with estuaries, islands, and tidal inlets.

This coast is further subdivided based on sedimentary environments and coastal processes. For example, the area between Marajó and Pirabas Bays features a narrow coastal plain and active cliffs formed from Tertiary sediments (Barreiras and Pirabas formations), while the region between Pirabas and Gurupi Bays is distinguished by expansive mangrove areas and sedimentary plains.

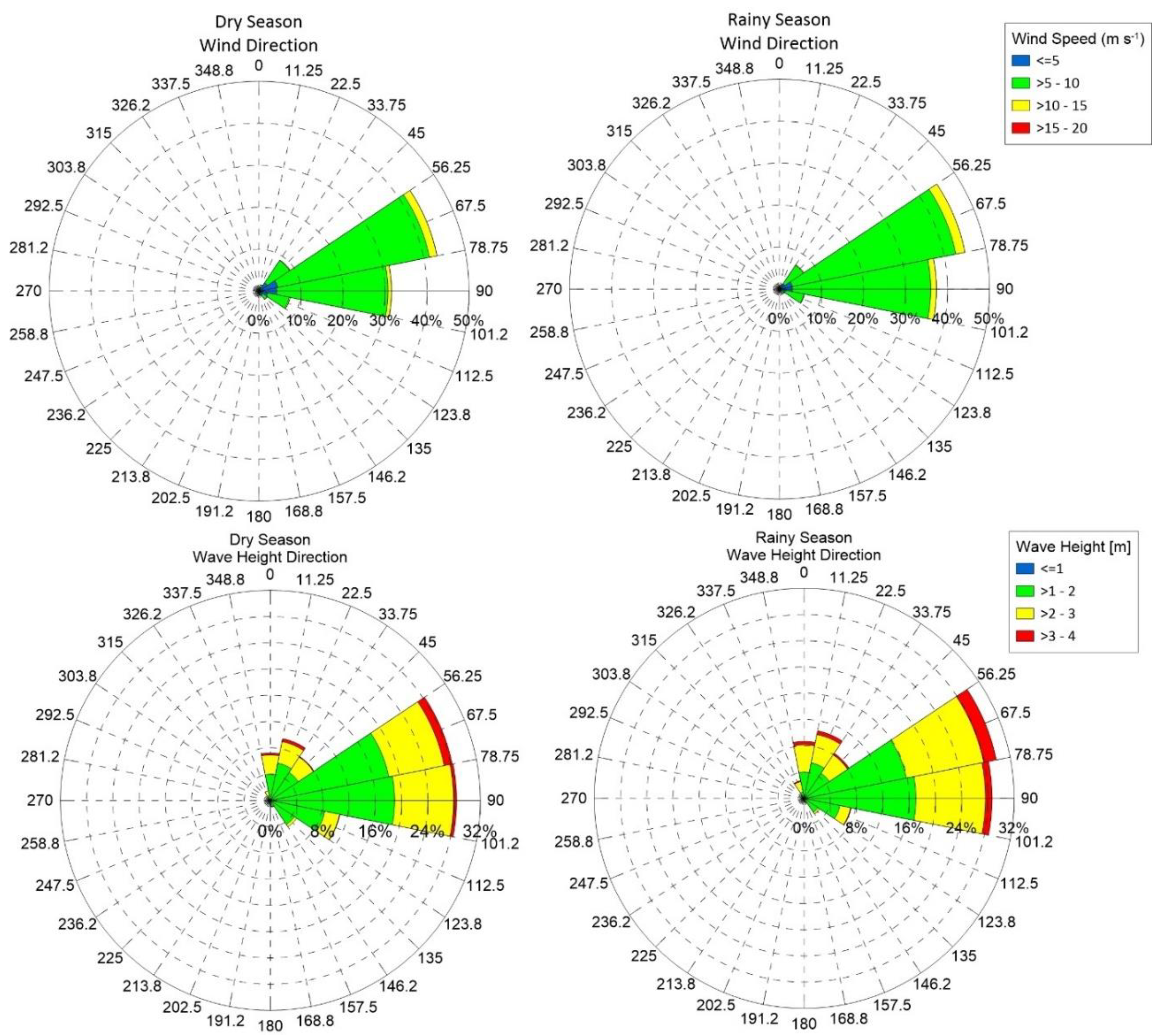

Offshore conditions are a critical element in understanding coastal dynamics. Data from NOAA’s National Data Buoy Center (Station 41041) indicate that prevailing trade winds—from the northeast and east—drive the generation of waves. During the rainy season (February–May), winds (5.0–14.0 m s

-1) produce significant wave heights (

Hs) of up to 5.0 m, with predominant directions between 50° and 110° and wave periods of 3 to 19 s. In contrast, during the dry season (September–November), wind speeds and wave heights are generally lower.

Figure 2 shows the offshore wind and wave parameters that control the nearshore conditions, setting the stage for coastal processes.

2.3. Climatic Drivers and Hydrological Dynamics

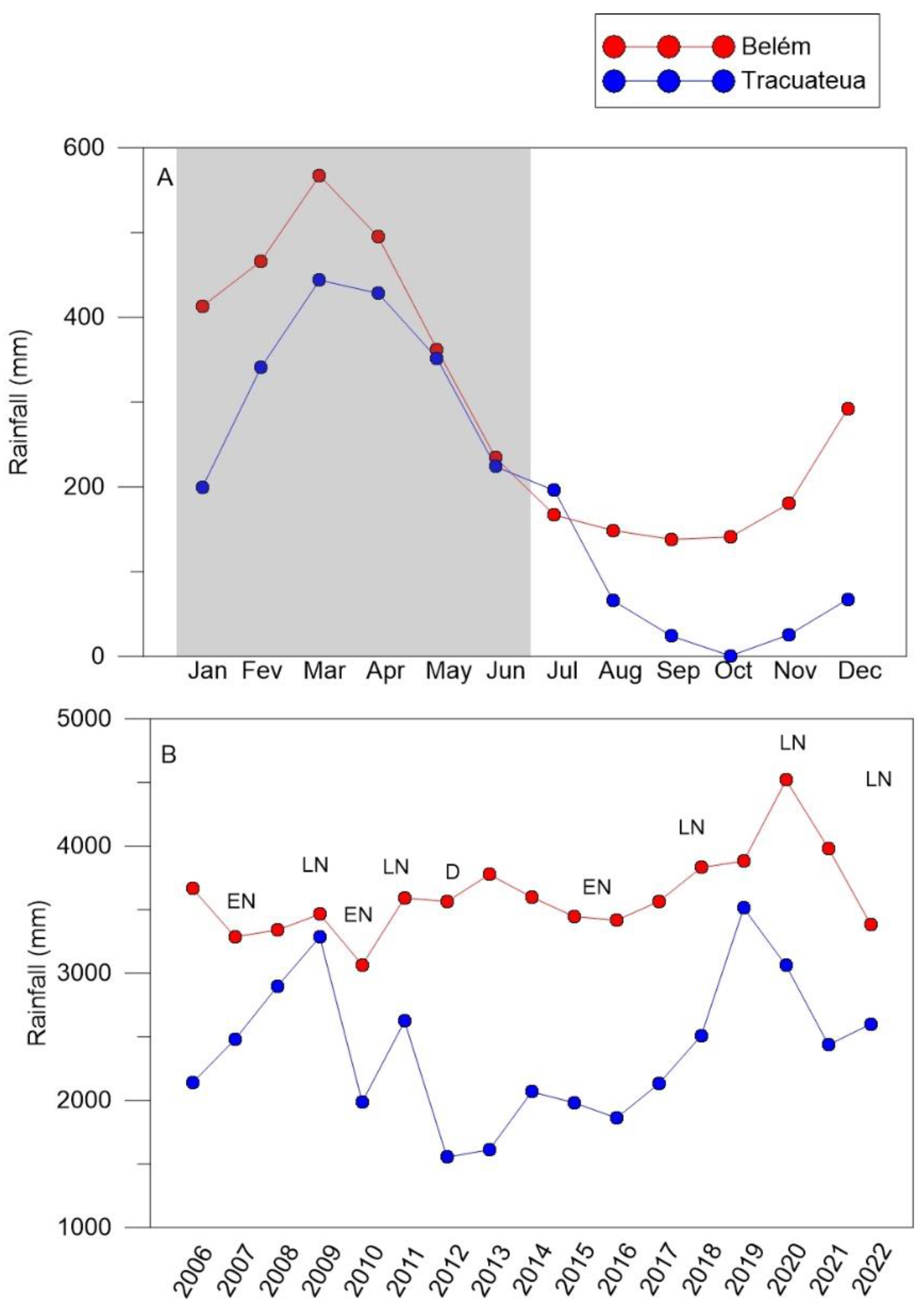

Rainfall on the Amazon coast is predominantly controlled by the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The region experiences a humid equatorial climate (Köppen Am) with distinct rainy (January–June) and dry (July–December) seasons (

Figure 3A). Annual rainfall (

Figure 3B) may exceed 2000 mm on the Atlantic coast sector (e.g., Tracuateua station) and 3000 mm within the continental estuarine sector (e.g., Belém station) [

41,

42].

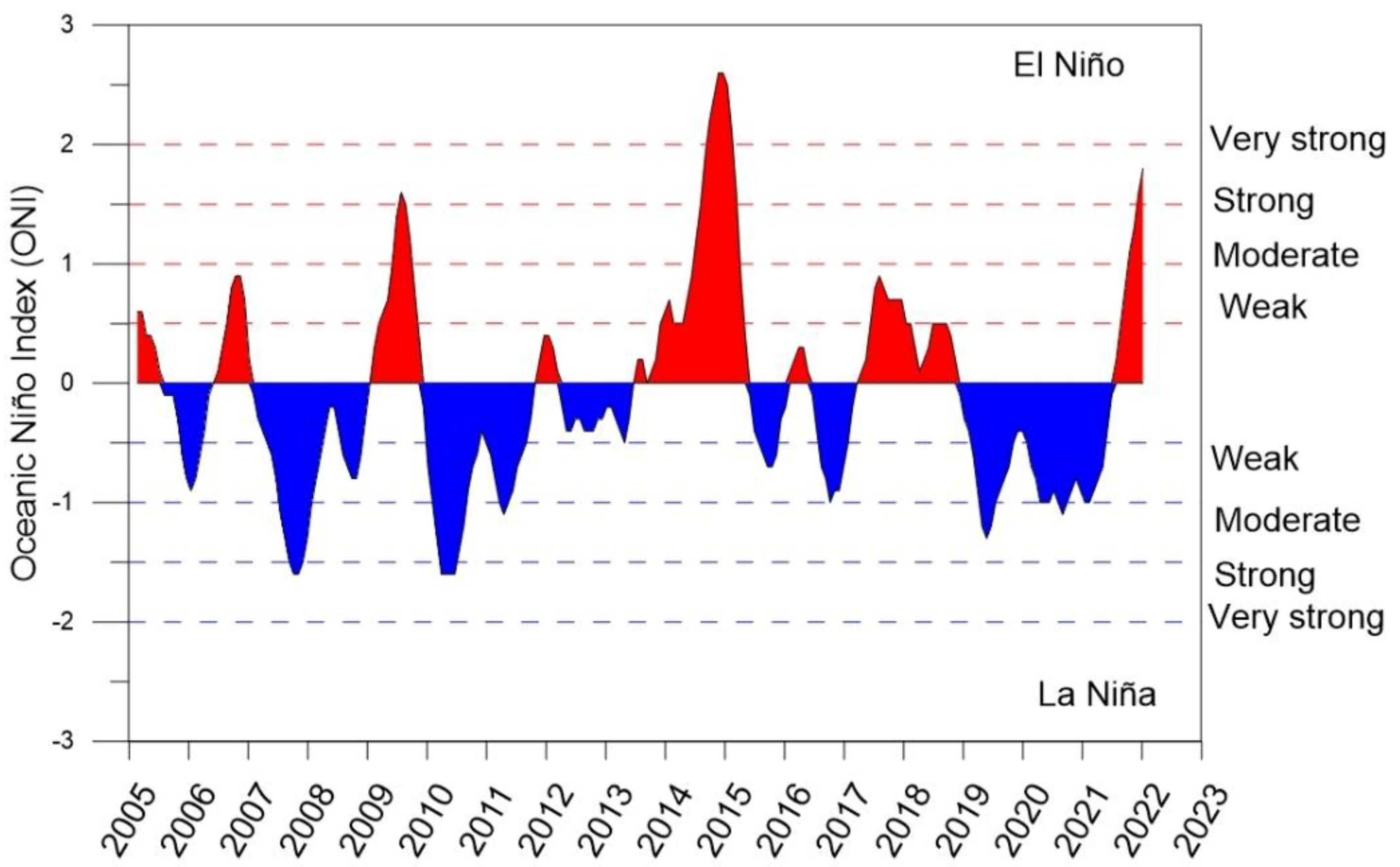

Interannual climate variability on the Amazon coast is strongly influenced by the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) for the Niño-3.4 region [

40], where El Niño events (ONI ≥ +0.5) reduce rainfall and La Niña events (ONI ≤ -0.5) enhance precipitation. Major El Niño events in 2009–2010 and 2015–2016, as well as La Niña episodes in 2007–2008 and 2010–2011, are clearly reflected in the ONI trends (

Figure 4). Additionally, severe droughts—such as those in 2005, 2010, and 2012—have also had notable impacts on regional hydrology, driven in part by elevated sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic.

River discharge is closely linked to regional rainfall, with peak flows typically occurring about one month after the highest precipitation periods. Data from the National Water Agency [

44] show significant variability between stations, such as the Atlantic Coast Sector (Nova Mocajuba station) and the Continental Estuarine Sector (Guamá station), where Guamá’s discharge is approximately 70% higher (

Figure 5).

The wide and shallow Amazonian continental shelf amplifies the tidal range; for instance, tidal amplitudes exceed 4 m in the Atlantic sector (Salinópolis station), but tide attenuation through the Marajó estuary causes a notable reduction in tidal amplitude at Belém and Breves stations (

Figure 6).

2.4. The Study Area and Beach Characteristics

The study area comprises beaches located across four sectors (

Figure 7): Eastern Marajó (Pesqueiro and Praia Grande), Continental Estuarine (Murubira), Fluvio-Maritime (Colares, Marudá, and Princesa), and the Atlantic Coast (Atalaia and Ajuruteua).

In the Eastern Marajó sector, Pesqueiro Beach is located in the municipality of Soure. This beach extends approximately 4 km in length and 1 km in width, with a north-south orientation and a straight to convex shoreline. Its gentle slope, segmented by large tidal channels, is influenced by fetch-limited waves from Marajó Bay and strong tidal currents. The fine to very fine sediments contribute to barrier beach formation, while adjacent mangrove and tidal flat systems offer natural shelter. Pesqueiro Beach lies within the Soure Marine Extractive Reserve, supporting traditional artisanal fishing communities. Also in the Eastern Marajó sector, Praia Grande was another beach studied. It features a 1.2 km-long beach with an NNW-SSE orientation, characterized by a narrow, concave sandy strip and steep topography at the base of coastal cliffs. Sediments derived from the Barreiras/Post-Barreiras Group, along with wave action and tidal currents, shape its geomorphology.

In the Continental Estuarine sector, Murubira Beach is situated on Mosqueiro Island along the Pará River. Murubira spans 1.4 km and is about 70 m wide at low tide. The beach is bordered by a series of active and inactive cliffs from the Barreiras Group, with hydrodynamics influenced by tidal ranges of approximately 3.5 m and wave heights reaching 1.5 m.

In the Fluvio-Maritime sector, Colares is a mesotidal beach located on Colares Island. It measures 560 m in length and 400 m in width during low spring tides. Additionally, Marudá Beach, situated at the mouth of the Marapanim estuary, experiences tidal ranges of up to 5 m, spans over 1 km in length, and reaches up to 300 m in width at low tide.

In the Atlantic Coast sector, the studied beaches were Princesa, Atalaia, and Ajuruteua. These insular beaches are surrounded by dunes, estuaries, lagoons, and mangroves. They are characterized by intertidal sandy ridges (200–400 m wide), shaped by macrotidal conditions (tidal ranges >4–6 m) and strong tidal currents (up to 1.5 m s⁻¹). Sandbanks modulate wave energy at low tide, while at high tide, wave heights may exceed 1.5 m. Princesa Beach benefits from additional protection within the Algodoal-Maiandeua Environmental Protection Area, whereas Atalaia and Ajuruteua are near protected areas such as the Caeté-Taperacu Marine Extractive Reserve and the Atalaia Natural Monument.

3. Methodology

This section introduces the newly proposed Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI), designed to assess coastal erosion and customized to the specific characteristics of the Amazon coast. The methodology is based on the CVI framework from [

46]. The dataset comprises 14 indicators grouped into four categories: Geological (GE), which includes Geomorphology (GM), Beach Slope (BS), Beach Exposure (BE), and Terrain Elevation (TE); Physical (PH), encompassing Wave Climate (WC), Spring Tidal Range (STR), Rainfall Level (RL), and Wave Orientation (WO); Environmental (EN), covering the Conservation Status of Dunes (CD), Conservation Status of Mangrove Forests (CM), and Protected Areas (PA); and Seafront Features (SF), which include Development Level (DL), Territorial Occupation (TO), and Erosion Indicator (EI).

Each CVI component represents a characteristic affecting overall coastal vulnerability, enabling a comprehensive analysis for the eight beaches studied. The indicators were obtained through field campaigns, satellite image analysis, and data from national and international sources (

Table 1). The vulnerability scores for each indicator range from 1, indicating Very low vulnerability, to 5, representing Very high vulnerability, as detailed in

Table 2. The CVI value was calculated (Eq. 1) using the arithmetic mean of the indicator values. In this study, the CVI was classified using the same principle applied to the indicators. This standardized scale facilitates the interpretation of the results.

eq.1

3.1. Development of the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI)

The geological component includes Geomorphology, which serves as an indicator of the relative erodibility of coastal landforms. For this indicator, vulnerability classification intervals are based on the susceptibility of various relief types, where rocky and cliffed coasts receive the lowest vulnerability scores, while landforms such as beach ridges, sandy beaches, muddy or sandy flats bordered by dunes, deltas, and mangrove environments are assigned the highest scores (

Table 2). Another indicator is Beach Slope, which encompasses both the subaerial beach profile (linked to inundation vulnerability) and the submerged slope (associated with erosion potential). Gentle slopes indicate higher vulnerability compared to steeper slopes, as shown in

Table 2. This study adopts the ranges provided by [

47]. Additionally, Beach Exposure is determined by natural and anthropogenic features, as well as wave-tide interactions (

Table 2). The classification system, adapted from [

29,

48], ranges from sheltered environments that provide physical protection (Very Low vulnerability) to exposed beaches lacking protective structures, with no modulation of the breaking wave climate (Very High vulnerability). The fourth indicator, Terrain Elevation, evaluates the vulnerability of coastal areas to inundation, overwash, and sea-level rise. In this study, the classification criteria were adapted from [

49]. For estuarine beaches, influenced by mesotidal conditions, Very Low vulnerability corresponds to elevations above 6 m, while Very High vulnerability applies to elevations below 3 m. For oceanic beaches, shaped by macrotidal conditions (tidal ranges typically between 5.0 and 6.0 m) and significant wave heights (

Hs) up to 1.8 m, Very Low Vulnerability is assigned to elevations above 9 m, and Very High vulnerability to elevations below 6 m. Only three scores, as indicated in

Table 2, were used for this indicator to align with those established by [

49].

The Physical component encompasses four indicators. The first is Wave Climate, a key factor in coastal sediment balance, particularly during high-energy wave events. According to [

47], the ratio between

Hs295% (wave height exceeded only 5% of the time) and the

Hs threshold (which depends on local conditions) defines coastal vulnerability based on erosion potential. When wave heights exceed this threshold, significant erosive impacts can reshape the coastline, damage habitats, and affect infrastructure (

Table 2). The second indicator is Spring Tidal Range, which is linked to risks of permanent and episodic flooding. High tidal ranges—especially when combined with strong tidal currents—are associated with increased coastal erosion [

50] (

Table 2). High Rainfall Levels directly influence the water table and coastal sediment transport. Greater beach saturation enhances sediment movement, increasing erosion (higher vulnerability). Along the Amazon coast, groundwater exfiltration in the upper intertidal zone occurs when cumulative three-month rainfall exceeds 500 mm [

51]. The fourth indicator is Wave Direction, which is determined by the angle between beach alignment and prevailing wave directions. Vulnerability is assessed based on criteria outlined in [

50], as shown in

Table 2.

With respect to the Environmental components, three indicators stand out. The first is the conservation status of dunes, as dunes serve as natural barriers that protect coastal areas and contribute to sediment balance. Adapted from [

52], vulnerability classifications range from preserved and vegetated dunes (Very Low vulnerability) to suppressed dunes (Very High vulnerability), as shown in

Table 2. The second indicator is the conservation status of mangrove forests, as mangroves act as protective barriers against waves and storms, making them effective indicators of erosion. Vulnerability classifications range from beaches with dense, mature mangroves showing no signs of erosion (Very Low vulnerability) to sparse or absent mangrove trees and leaning vegetation (Very High vulnerability), as shown in

Table 2. The last indicator is the presence of protected areas, primarily designated for sustainable use. Vulnerability is ranked from beaches located within protected areas (Very Low vulnerability) to beaches outside and distant from protected areas (Very High vulnerability).

The Seafront features are composed of three indicators. The first is Development Level, which assesses the distribution of populations and settlements to determine the degree of development in an area. This can place pressure on coastal zones and potentially exacerbate coastal erosion. Development levels are categorized into five classifications, as presented in

Table 2. The second indicator is Territorial Occupation, which evaluates the percentage of spatial occupation along the seafront. Scores, adapted from [

53], are determined based on the percentage of occupation, as outlined in

Table 2. The third indicator is Erosion Indicators, which analyze the presence of specific signs of coastal erosion, as shown in

Table 2. These indicators include buried vegetation, exposed roots, erosion escarpments, narrowing or absence of the backshore, coastal protection structures, and damage to seafront properties

4. Results

4.1. The Coastal Vulnerability Index-CVI

The Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) (

Table 3) highlights differences in vulnerability among the studied beaches. The lowest vulnerability scores are observed in rural beaches such as Pesqueiro (CVI = 2.9), Princesa (CVI = 3.2) and Colares (CVI = 3.3). Although geological and physical factors contribute to Moderate to High vulnerability in these areas, their lower overall vulnerability is attributed to the conservation of dune, mangrove, and restinga environments, along with limited development and reduced human impact. Moderate vulnerability scores are assigned to Praia Grande (CVI = 3.6) and Murubira (CVI = 3.6), primarily due to higher scores in physical factors (such as rainfall levels and wave orientation), environmental aspects (absence of protected areas), and seafront features (erosion indicators). The highest vulnerability scores are recorded for semi-urban beaches, including Marudá (CVI = 4.2), Atalaia (CVI = 4.2), and Ajuruteua (CVI = 4.0). Ajuruteua, although currently a rural beach, is undergoing rapid development and transitioning towards semi-urbanization, increasing its vulnerability. Below is the description of the indicators by sector.

4.2. Eastern Marajó Island (Sector II)

In this sector, two beaches were analyzed: Pesqueiro and Praia Grande. Pesqueiro Beach exhibited Very High vulnerability in the Geological and Physical components, particularly in the Geomorphology indicator, as it is a barrier beach characterized by a curved spit shaped by local north-south longitudinal sediment transport. Similarly, High vulnerability was observed in the Rainfall level indicator, due to rainfall accumulation exceeding 1500 mm over three months during the rainiest period, and in the Wave orientation indicator. Moreover, High vulnerability was noted in the Beach slope indicator, as the slope typically ranges between 0.02 and 0.04, and in the Wave climate indicator, where the ratio of Hs295% to Hs2 falls between 1.0 and 1.5. Conversely, Pesqueiro Beach is situated within a protected area, which results in Low vulnerability for five of the six environmental and seafront feature indicators. It is a rural beach surrounded by well-preserved dunes and mangroves, making it part of the Soure Marine Extractive Reserve. Territorial occupation along the beachfront is less than 30%. The sole exception was the Erosion indicator, which revealed evidence of buried vegetation, exposed roots, and an erosion escarpment. As a consequence of the erosion issue, the beach area experienced a reduction of 61,202 m² between 2007 and 2021 (Figure 9).

At Praia Grande, six indicators exhibit Moderate vulnerability: two within the Geology component: (i) Geomorphology, as it is a beach with ridges running in a NNW-SSE direction, bordered by cliffs and headlands of the coastal plateau; and (ii) beach slope, which ranges between 0.04 and 0.08. One indicator within the Physical component, the Spring tidal range, reaching 2.0–4.0 m, classifying it as mesotidal. Two indicators within the Environmental component—dunes and mangroves, which are partially affected by nearby construction. Finally, one within the Seafront features component. Very High vulnerability was recorded in the Physical component for Rainfall level and Wave orientation. It is a semi-urban beach located outside protected zones. The Territorial occupation at Praia Grande covers 50–70% of the beachfront, indicating High vulnerability, with Erosion indicators including property damage, cliffs, mangroves, dunes, exposed roots, and a narrow shoreline.

4.3. Continental Estuarine and Fluvio-Maritime (Sectors III and IV)

Four beaches were studied within these sectors: Murubira, Colares, Marudá, and Princesa. Murubira Beach is characterized by active cliffs of the Barreiras Group, indicating Moderate vulnerability. Its Beach slope, ranging between 0.04 and 0.08, is also classified as Moderate vulnerability. About 75% of its terrain has elevations greater than 6 m, corresponding to Very Low vulnerability. Colares Beach features sandy deposits primarily shaped by Wave action, located at the foot of cliffs, resulting in Moderate vulnerability. Its Beach slope, ranging between 0.04 and 0.08, also falls under Moderate vulnerability, with 86% of the coastline at elevations between 3 and 6 m. Marudá Beach consists of sandy ridges, forming banks and channels that create Very High vulnerability (

Figure 8). The beach slope, varying from 0.02 to 0.04, indicates High vulnerability, while 100% of the coastline has elevations between 3 and 6 m, marking it as Moderate vulnerability. Princesa Beach is a flat, linear barrier ridge, surrounded by dunes and mangroves, contributing to Very High vulnerability. Its Beach slope, ranging between 0.08 and 0.12, is considered Low vulnerability, but its coastal elevation, measuring less than 6 m, results in Very High vulnerability for this indicator.Among all beaches in these sectors, the

Hs295% and the

Hs2 ratio exceeded 1.5, only in Princesa beach.

In addition, Murubira and Colares exhibit mesotidal conditions, with a Spring tidal range of 3.9 m, indicating Moderate vulnerability, while Marudá and Princesa, with Spring tidal ranges exceeding 4.0 m, fall into the macrotidal category, leading to Very High vulnerability. During the rainiest months, rainfall accumulation surpasses 1500 mm over three months across all beaches, resulting in Very High vulnerability in this regard. The Environmental features further differentiate these beaches. Murubira and Marudá experience significant human impact, with territorial occupation affecting 70–80% of the coastline, leading to Very High vulnerability. These semi-urban beaches are heavily used for recreational purposes, causing considerable modifications to their original natural conditions, resulting in Moderate vulnerability. Erosion indicators, such as buried vegetation, exposed roots, erosion escarpments, and damage to properties, are prominent in both locations. Colares and Princesa are rural and less developed, which places them in Low and Very Low vulnerability categories, respectively. Colares, in particular, has less than 30% of its coastline occupied by buildings, with well-preserved dunes and native vegetation, denoting Low vulnerability. Princesa Beach, located within the Algodoal/Maiandeua Environmental Protection Area, enforces strict territorial management, ensuring well-conserved dunes and mangroves, contributing to Very Low vulnerability. However, the construction of 30 bars in the intertidal zone adds an element of Low vulnerability to its overall environmental profile. However, at Marudá and Princesa beaches, the surface area decreased by 41,414 m² and 51,910 m², respectively, between 2007 and 2021. In Murubira, the retaining wall helped limit the reduction in surface area to 709 m² during this period (

Figure 9).

4.4. Atlantic Coast (Sector V)

The two beaches analyzed in this sector, Ajuruteua and Atalaia, are geomorphologically classified as highly vulnerable due to their barrier beach ridge characteristics (

Figure 8). Both beaches are flat, linear, elongated landforms, bordered by tidal deltas, dunes, and mangrove areas, contributing to their Very High vulnerability. Additionally, the beach slope is absent in both Ajuruteua and Atalaia, further emphasizing their Very High vulnerability. During low tide, semi-submerged sandbanks offer protection to both beaches. Ajuruteua provides better protection during low tide, with wave heights (

Hs values) ranging from 0.1 to 0.4 m, while Atalaia offers less protection, with

Hs values between 0.5 and 0.8 m. The seafront terrain elevation ranges from 3 to 9 m, yet inhabited areas reveal that 52% of Ajuruteua’s coastline and 77% of Atalaia’s coastline feature elevations below 6 m, placing both beaches in the Very High vulnerability category.

The physical indicators further reflect their susceptibility to erosion. The Hs295% and the Hs2 threshold ratio exceeded 1.5, indicating Very High vulnerability. This ratio signifies that wave heights exceeded 5% of the time are greater than 2.5 m, demonstrating significant erosion potential. Additionally, the spring tidal range (sTR) for both beaches varies between 5 and 6 m, representing high vulnerability. Rainfall accumulation during the wettest months surpasses 1500 mm over three months, confirming very high vulnerability in this regard.

In addition, Ajuruteua is adjacent to the Caeté-Taperaçu Marine Extractive Reserve, established in 2005, while Atalaia is adjacent to the Atalaia Natural Monument, created in 2018. Both beaches feature numerous wooden structures built on stilts within the intertidal zone, dunes, and mangrove areas. Territorial occupation affects 50–70% of Ajuruteua’s coastline, resulting in High vulnerability, while Atalaia’s territorial occupation exceeds 70%, placing it in the Very High vulnerability category. Ajuruteua retains rural characteristics but is transitioning into semi-urbanization, presenting Low vulnerability. Several houses, bars, and restaurants line its seafront, whereas Atalaia Beach exhibits significant semi-urbanization, with extensive construction of bars, hotels, and houses, contributing to moderate vulnerability. With respect to erosion, both beaches have experienced substantial erosion over the decades, leading to the partial or complete destruction of buildings, infrastructure, dunes, and mangroves. Equinoctial spring tides exacerbate erosion events, resulting in the loss of street lighting, bars, restaurants, and inns. At Atalaia, wooden structures are frequently relocated to dunes during periods of severe erosion, while Ajuruteua has implemented structural engineering solutions to protect its buildings. However, Ajuruteua’s surface area has decreased by 110,046 m² betweem 2007-2021 (

Figure 9). Common erosion indicators at both beaches include buried vegetation, exposed roots, escarpments, concentrations of heavy minerals, coastal protection structures, and damage to seafront properties.

5. Discussion

5.1. Geological Indicators

Coastal erosion vulnerability is assessed through indicators that reflect susceptibility to high-energy events [

27,

47,

54]. In this study, the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) incorporates geological, physical, environmental, and seafront indicators. Geomorphology was classified based on the relative resilience of coastal landforms [

8,

55,

56]. Two types of coastal relief were identified: (i) barrier beach ridges -composed of unconsolidated sediments and highly vulnerable (score 5)- found in Pesqueiro, Marudá, Princesa, Atalaia, and Ajuruteua; and (ii) low cliffs, moderately vulnerable, in Praia Grande, Murubira, and Colares. Beach slope, a key erosion predictor, shows that gentler slopes are more prone to erosion [

49,

57]. Protection levels—natural or artificial—also modulate exposure: (i) Estuarine beaches within bays (e.g., Marajó Bay) are Moderate vulnerability due to limited fetch; (ii) Partially protected beaches (e.g., with sandbanks or tidal bars) show Very Low vulnerability; (iii) Less sheltered beaches, like Atalaia, exhibit Low vulnerability [

29]. Elevation proved to be crucial: beaches below 6 m are highly vulnerable, 6–9 m moderately so, and above 9 m have low vulnerability (modified from [

48]). High vulnerability coincides with barrier beach ridges, while low cliffs correspond to lower vulnerability.

5.2. Physical Indicators

Tidal attenuation reduces tidal elevation by ~35% in Marajó Bay compared to the Atlantic coast. Thus, macrotidal beaches (Atlantic) are more vulnerable due to stronger currents and flooding risk, contrary to previous classifications [

46,

58]. On the Amazon coast, macrotides and moderate waves drive intense erosion, particularly during equinoctial spring tides [

28,

51]. Offshore waves (3–4 m) attenuate nearshore (1–2 m), with sandbanks buffering wave energy at low tide. However, high tide exposes the shoreline to wave impact, making it the critical period for erosion. Storm-induced vulnerability is classified as very high (CVI > 1.5) due to significant

Hs values (1.5–1.8 m). Wave incidence angles (θ > 70°) increase exposure [

56,

59]. Rainfall also contributes: heavy seasonal rains saturate beaches, enhancing offshore sediment transport and erosion [

60]. All beaches showed High vulnerability due to intense rainfall.

5.3. Environmental Indicators

Dune fields and coastal vegetation—such as mangroves and restinga—serve as critical natural barriers. They not only mitigate the direct impact of waves and storms on the coast but also play a central role in maintaining the sediment balance by acting as both buffers and sources of sediment for neighboring areas. In the study area, rural beaches with well-preserved dune systems and mangroves (e.g., Pesqueiro, Colares, and Princesa) demonstrated Low vulnerability to erosive processes, highlighting the protective function of these natural elements. In addition, the existence of protected areas, where local regulations restrict unplanned urban expansion and promote coastal ecosystem preservation [

61,

62,

63], reinforces the resilience of these coastal zones. Such areas facilitate the implementation of sustainable management strategies and effective land-use regulations, which are essential for maintaining the natural stability of the coastline. In contrast, unregulated development and disorganized territorial occupation alter sedimentary processes and significantly increase erosion risk [

64,

65]. This unsustainable development undermines the natural recovery capability of coastal ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to extreme events.

5.4. Seafront Features

In terms of seafront features, semi-urban beaches like Murubira, Atalaia, and Marudá are characterized by a higher concentration of facilities and services—including restaurants, bars, private residences, inns, and hotels—which intensifies the pressure on these coastal zones. In areas with high territorial occupation (e.g., Praia Grande, Murubira, Marudá, Atalaia, and Ajuruteua), increased anthropogenic activity often exacerbates the natural processes of erosion. The presence of infrastructure limits the natural adaptability of the coast, often aggravating erosion by altering natural sediment dynamics.

When erosion intensifies, it frequently results in significant structural impacts: wooden buildings might be relocated to avoid total loss of utility, whereas concrete constructions could suffer partial or complete failure. Visible signs of erosion include deteriorating structures, exposed tree roots, and the tilting or collapse of trees, which are indicators of severe substrate instability. Although some coastal protection structures have been installed in locations such as Atalaia, Ajuruteua, and Murubira, these interventions are typically limited in scope and sometimes insufficient to counteract the severe impact of extreme weather events.

Furthermore, climatic phenomena like El Niño and La Niña amplify these challenges by causing alternating periods of drought and intense rainfall. These events not only increase rainfall intensity and wave energy during strong wind conditions but also elevate groundwater levels, further destabilizing the coastal landscape. The compounded influence of natural forces and human activities underscores the importance of comprehensive vulnerability assessments. Such integrated analyses are crucial for devising sustainable coastal management strategies and for planning interventions aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of coastal erosion.

6. Summary and Conclusions

This study evaluated the erosion vulnerability of eight beaches along the Pará coast (Amazonian coast, Brazil) by integrating geomorphological characteristics, coastal physical processes, patterns of territorial occupation, ecosystem conservation, and erosion indicators. The analysis revealed a vulnerability spectrum ranging from low to high across the study area. Natural factors play a crucial role, as the inherent geology and physical processes largely drive high vulnerability in most of the beaches. Anthropogenic impacts further exacerbate vulnerability, with unplanned territorial occupation significantly affecting semi-urban beaches (e.g., Atalaia) or in semi-urban process (e.g., Ajuruteua) with higher development. In contrast, rural beaches, particularly those within protected areas, demonstrated lower vulnerability due to reduced human interference and better preservation of natural protective features. However, evidence of erosion was recorded in Princesa and Pesqueiro beaches. The presence of promade on the semi-urban beaches of Marudá, Murubira, and Colares prevented them from experiencing significant variations in the coastline; Extreme meteorological events, including prolonged rainfall and intensified wave activity, also contribute to erosion, temporarily heightening erosive processes and disrupting coastal equilibrium. These episodic events can accelerate erosion, posing additional threats to coastal stability. The findings highlight the necessity of integrating comprehensive vulnerability assessments into coastal management practices. They provide critical support for the development and implementation of mitigation strategies to reduce erosion impacts on both estuarine and oceanic beaches, regardless of urbanization levels. Overall, the study offers valuable insights for the sustainable management of natural resources and infrastructure preservation along the Amazonian coast, emphasizing the need for proactive and adaptive management strategies in response to both natural and human-induced challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Pereira RLMC, Pereira LCC and Aranda CM; methodology, RLMC, Pereira LCC and Aranda CM; validation, RLMC, Pereira LCC and Aranda CM; formal analysis, RLMC, Pereira LCC and Aranda CM; investigation, RLMC and Pereira LCC; resources, RLMC, Pereira LCC and Aranda CM; data curation, RLMC, Pereira LCC and Aranda CM; writing—original draft preparation, RLMC, Pereira LCC and Aranda CM; supervision, RLMC and Aranda CM; funding acquisition, Pereira LCC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq (483913/2012-0, 431295/2016-6, 314037/ 2021–7).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) through a Universal Project (483913/2012-0, 431295/2016-6). The authors Pereira LCC (314037/2021–7) would also like to thank CNPq for its research grants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martinez, M.L.; Intralawan, A.; Vázquez, G.; Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Sutton, P.; Landgrave, R. The coasts of our world: Ecological, economic and social importance. Ecol Econ 2007, 63, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hacker, S.D.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol Monogr 2011, 81, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, D.H.; Kumar, N.D. Coastal erosion studies—a review. Int J Geosci 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Ranasinghe, R.; Mentaschi, L.; Plomaritis, T.A.; Athanasiou, P.; Luijendijk, A.; Feyen, L. Sandy coastlines under threat of erosion. Nat Clim Chang 2020, 10, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzini, E.; Williams, A.T. Coastal erosion and protection in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; 457p. [Google Scholar]

- Mentaschi, L.; Vousdoukas, M.I.; Pekel, J.F.; Voukouvalas, E.; Feyen, L. Global long-term observations of coastal erosion and accretion. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 12876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A. JR.; FitzGerald, D.M. Beaches and coasts, 1st ed.; Blackwell science Ltd, 2004; Volume 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karymbalis, E.; Chalkias, C.; Chalkias, G.; Grigoropoulou, E.; Manthos, G.; Ferentinou, M. Assessment of the sensitivity of the southern coast of the Gulf of Corinth (Peloponnese, Greece) to sea-level rise. Cent Eur Geol 2012, 4, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmerman, S.; Meire, P.; Bouma, T.J.; Herman, P.M.; Ysebaert, T.; Vriend, H.J. Ecosystem-based coastal defence in the face of global change. Nature 2013, 504, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biel, R.G.; Hacker, S.D.; Ruggiero, P.; Cohn, N.; Seabloom, E.W. Coastal protection and conservation on sandy beaches and dunes: context-dependent tradeoffs in ecosystem service supply. Ecosphere 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, A.; Defeo, O.; Short, A.D. Characterising sandy beaches into major types and states: Implications for ecologists and managers. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 2018, 215, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolinez, J.A.A.; Méndez, F.J.; Camus, P.; Vitousek, S.; González, E.M.; Ruggiero, P.; Barnard, P. A multiscale climate emulator for long-term morphodynamics (MUSCLE-morpho). J Geophys Res Oceans 2016, 121, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, M.D.; Masselink, G.; Alegría-Arzaburu, R.A.; Valiente, N.G.; Scott, T. Single extreme storm sequence can offset decades of shoreline retreat projected to result from sea-level rise. Commun Earth Environ 2022, 3, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Mondal, I.; Bar, S.; Nandi, S.; Ghosh, P.B.; Das, P.; De, T.K. Shoreline changes and its impact on the mangrove ecosystems of some islands of Indian Sundarbans, North-East coast of India. J Clean Prod 2021, 284, 124764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.R.; Jones, A.L. ; Erosion and tourism infrastructure in the coastal zone: Problems, consequences and management. Tour Manag 2006, 27, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig-Munar, F.X.; Mir-Gual, M.; Rodríguez-Perea, A.; Pons, G.X.; Martín-Prieto, J.A.; Gelabert, B.; Blázquez-Salom, M. Beaches of Ibiza and Formentera (Balearic Islands): a classification based on their environmental features, tourism use and management. J Coast Res 2013, 65, 1850–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splinter, K.D.; Carley, J.T.; Golshani, A.; Tomlinson, R. A relationship to describe the cumulative impact of storm clusters on beach erosion. Coast Eng 2014, 83, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, M.D.; Turner, I.L.; Kinsela, M.A.; Middleton, J.H.; Mumford, P.J.; Splinter, K.D.; Short, A.D. Extreme coastal erosion enhanced by anomalous extratropical storm wave direction. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavola, P.; Coco, G. Coastal storms: processes and impacts; John Wiley & Sons, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.C.; Guimarães, D.O.; Ribeiro, M.J.S.; Costa, R.M.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M. Use and occupation in Bragança littoral, Brazilian Amazon. J Coast Res 2007, SI 50, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.C.; Sousa-Felix, R.C.; Costa, R.M.; Jimenez, J.A. Challenges of the recreational use of Amazon beaches. Ocean Coast Manag 2018, 165, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, C.H.R.I.S. Indicative mapping of Tasmanian coastal geomorphic vulnerability to sea-level rise using GIS line map of coastal geomorphic attributes; Consultant Report to Department of Primary Industries & Water: Tasmania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Narra, P.; Coelho, C.; Sancho, F.; Escudero, M.; Silva, R. Coastal hazard assessments for sandy coasts: appraisal of five methodologies. J Coast Res 2019, 35, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rosales, B.; Abreu, D.; Ortiz, R.; Becerra, J.; Cepero-Acán, A.E.; Vázquez, M.A.; Ortiz, P. Risk and vulnerability assessment in coastal environments applied to heritage buildings in Havana (Cuba) and Cadiz (Spain). Sci Total Environ 2021, 750, 141617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornitz, V.M. Vulnerability of the East Coast USA to future sea level rise. J Coast Res 1990, 9, 201–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Kunte, P.D. Coastal vulnerability assessment for Chennai, east coast of India using geospatial techniques. Nat Hazards (Dordr) 2012, 64, 853–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantusa, D.; D’Alessandro, F.; Riefolo, L.; Principato, F.; Tomasicchio, G.R. Application of a coastal vulnerability index. A case study along the Apulian Coastline, Italy. Water 2018, 10, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.C.; Vila-Concejo, A.; Costa, R.M.; Short, A.D. Managing physical and anthropogenic hazards on macrotidal Amazon beaches. Ocean Coast Manag 2014, 96, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.C.; Vila-Concejo, A.; Short, A.D. Coastal Morphodynamic Processes on the Macro-Tidal Beaches of Pará State Under Tidally Modulated Wave Conditions. In Brazilian Beach Systems. Coastal Research Library; Short, A., Klein, A., Eds.; Springer Cham, 2016; vol 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, J.E.; Gardel, A.; Proisy, C.; Fromard, F.; Gensac, E.; Peron, C.; Walcker, R.; Lesourd, S. The role of fluvial sediment supply and river-mouth hydrology in the dynamics of the muddy Amazon-dominated Amapá-Guianas coast South America: a three-point research agenda. J S Am Earth Sci 2013, 44, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, J.E.; Gardel, A.; Gratiot, N. Fluvial sediment supply, mud banks, cheniers and the morphodynamics of the coast of South America between the Amazon and Orinoco river mouths. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2014, 388, 533–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, V.J.; Barthem, R.B. Os Recursos pesqueiros da Amazônia brasileira; PR-MCT/CNPq Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Meade, R.H.; Rayol, J.M.; Conceicão, S.C.; Natividade, J.R. Backwater effects in the Amazon River basin of Brazil. Environ Geol Water Sci 1991, 18, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, R.L.; Amado-Filho, G.M.; Moraes, F.C.; Brasileiro, P.S.; Salomon, P.S.; Mahiques, M.M.; Thompson, F.L. An extensive reef system at the Amazon River mouth. Sci Adv 2016, 2, e1501252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, J.E.; Gardel, A.; Gratiot, N.; Proisy, C.; Allison, M.A.; Dolique, F.; Fromard, F. The Amazon-influenced muddy coast of South America: a review of mud-bank–shoreline interactions. Earth Sci Rev 2010, 103, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, T.; Mertes, L.A.K.; Meade, R.; Richey, J.E.; Forsberg, B.R. Exchanges of sediment between the floodplain and channel of the Amazon in Brazil. Geol Soc Am Bull 1998, 110, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjerfve, B.; Lacerda, L.D. Mangroves of Brazil. In Conservation and sustainable utilization of mangrove forests in Latin America and Africa regions; Lacerda, L.D., Ed.; International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems: Okinawa, 1993; pp. 245–272. [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Morais Tozzi, H.A.; El-Robrini, M. Geomorphology, land-use and environmental hazards in Ajuruteua macrotidal sandy beach, northern Brazil. J Coast Res 2003, 580–589. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40928810.

- Franzinelli, E. Evolution of the geomorphology of the coast of the State of Pará Brazil. In Évolution des littoraux de Guyane et de la Zone Caraïbe Méridionale pendant le Quaternaire; Prost, M.T., Ed.; ORSTOM: Paris, 1992; pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-NOAA, 2024. Buoy Data - 41041 Middle Atlantic ncei.noaa.gov/access/marine-environmental-buoy-database/41041.html.

- Figueroa, S.N.; Nobre, C.A. Precipitations distribution over central and western tropical South America. Climanálise 1990, 5, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marengo, J.A. Interannual variability of deep convection over the tropical South American sector as deduced from ISCCP C2 data. Int J Climatol 1995, 15, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agência Bacional de Águas - ANA.; 2024. https://www.gov.br/ana/pt-br.

- Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia – INMET, 2024. Monitoramento das estações automáticas. http://www.inmet.gov.br/sonabra/maps/automaticas.php.

- Centro de Hidrografia da Marinha - CHM, 2024. Tábuas de maré. www.marinha.mil.br/chm/dados-do-segnav/dados-de-mare-mapa.

- Thieler, E.R.; Hammar-Klose, E.S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise: preliminary results for the US Atlantic coast (No. 99-593). US Geological survey. 1999.

- López Royo, M.; Ranasinghe, R.; Jiménez, J.A. A rapid, low-cost approach to coastal vulnerability assessment at a national level. J Coast Res 2016, 32, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangor, K.; Drønen, N.K.; Kærgaard, K.H.; Kristensen, S.E. Shoreline management guidelines. 2004.

- Bush, D.M.; Neal, W.J.; Young, R.S.; Pilkey, O.H. Utilization of geoindicators for rapid assessment of coastal-hazard risk and mitigation. Ocean Coast Manag 1999, 42, 647–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragaki, A.; Gallousi, C.; Karymbalis, E. Coastal hazard vulnerability assessment based on geomorphic, oceanographic and demographic parameters: The case of the Peloponnese (Southern Greece). Land 2018, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Concejo, A.V.; Trindade, W. Tidal modulation. In Sandy Beach Morphodynamics; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.H.G.O. Vulnerabilidade à erosão costeira no litoral de São Paulo: Interação entre processos costeiros e atividades antrópicas (PhD dissertation) São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto Oceanográfico. 2013.

- Silva, I.R.; Pereira, L.C.C.; Trindade, W.N.; Magalhaes, A.; Costa, R.M. Natural and anthropogenic processes on the recreational activities in urban Amazon beaches. Ocean Coast Manag 2013, 76, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrakis, G.; Poulos, S. An holistic approach to beach erosion vulnerability assessment. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageswara Rao, K.; Subraelu, P.; Venkateswara Rao, T.; Hema Malini, B.; Ratheesh, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Ajai. Sea-level rise and coastal vulnerability: an assessment of Andhra Pradesh coast, India through remote sensing and GIS. J Coast Conserv 2008, 12, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, T.S.; Sousa, P.H.G.O.; Siegle, E. Vulnerability to beach erosion based on a coastal processes approach. Appl Geogr 2019, 102, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzeda, F.; Ortega, L.; Costa, L.L.; Fanini, L.; Barboza, C.A.; McLachlan, A.; Defeo, O. Global patterns in sandy beach erosion: unraveling the roles of anthropogenic, climatic and morphodynamic factors. Front Mar Sci 2023, 10, 1270490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, E.A.; Thieler, E.R.; Williams, S.J.; Beavers, R.L. Coastal vulnerability assessment of Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS) to sea-level rise (No. 2004-1090). US Geological Survey. 2004.

- Pereira, L.C.C.; Silva, N.I.S.; Costa, R.M.; Asp, N.E.; Costa, K.G.; Vila-Concejo, A. Seasonal changes in oceanographic processes at an equatorial macrotidal beach in northern Brazil. Cont Shelf Res 2012, 43, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Moura, D.; Horta, J.; Nascimento, A.; Gomes, A.; Veiga-Pires, C. The morphosedimentary behaviour of a headland–beach system: Quantifying sediment transport using fluorescent tracers. Mar Geol 2017, 388, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, R.M.C.; Pereira, L.C.C.; Sousa, R.C.; Costa, R.A.M. Water Quality during the Recreational High Season for a Macrotidal Beach (Ajuruteua, Pará, Brazil). J Coast Res 2016, 75, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, R.M.C.; Jiménez, J.A.; Costa, R.M.; Pereira, L.C.C. Federal conservation units in the Brazilian amazon coastal zone: An adequate approach to control recreational activities? Ocean Coast Manag 2019, 178, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.C.; Pessoa, R.M.C.; Sousa-Felix, R.C.; Dias, A.B.B.; Costa, R.M. How sustainable are recreational practices on Brazilian Amazon beaches? J Outdoor Recreat Tour 2024, 45, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.C.; Pereira, L.C.C.; Silva, N.I.S.; Oliveira, S.M.O.; Pinto, K.S.T.; Costa, R.M. Recreational carrying capacity of three Amazon macrotidal beaches during the peak vacation season. J Coastal Res 2011, 64, 1292–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, P.H.; Siegle, E.; Tessler, M.G. Vulnerability assessment of Massaguaçú beach (SE Brazil). Ocean Coast Manag 2013, 77, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).