Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Natural Characteristics

2.2. Post-Colonial Occupation of the Southern Coastal Region of Santa Catarina State, Intensity of Occupation of the Balneário Gaivota Municipality, and Regional Urban Sprawl

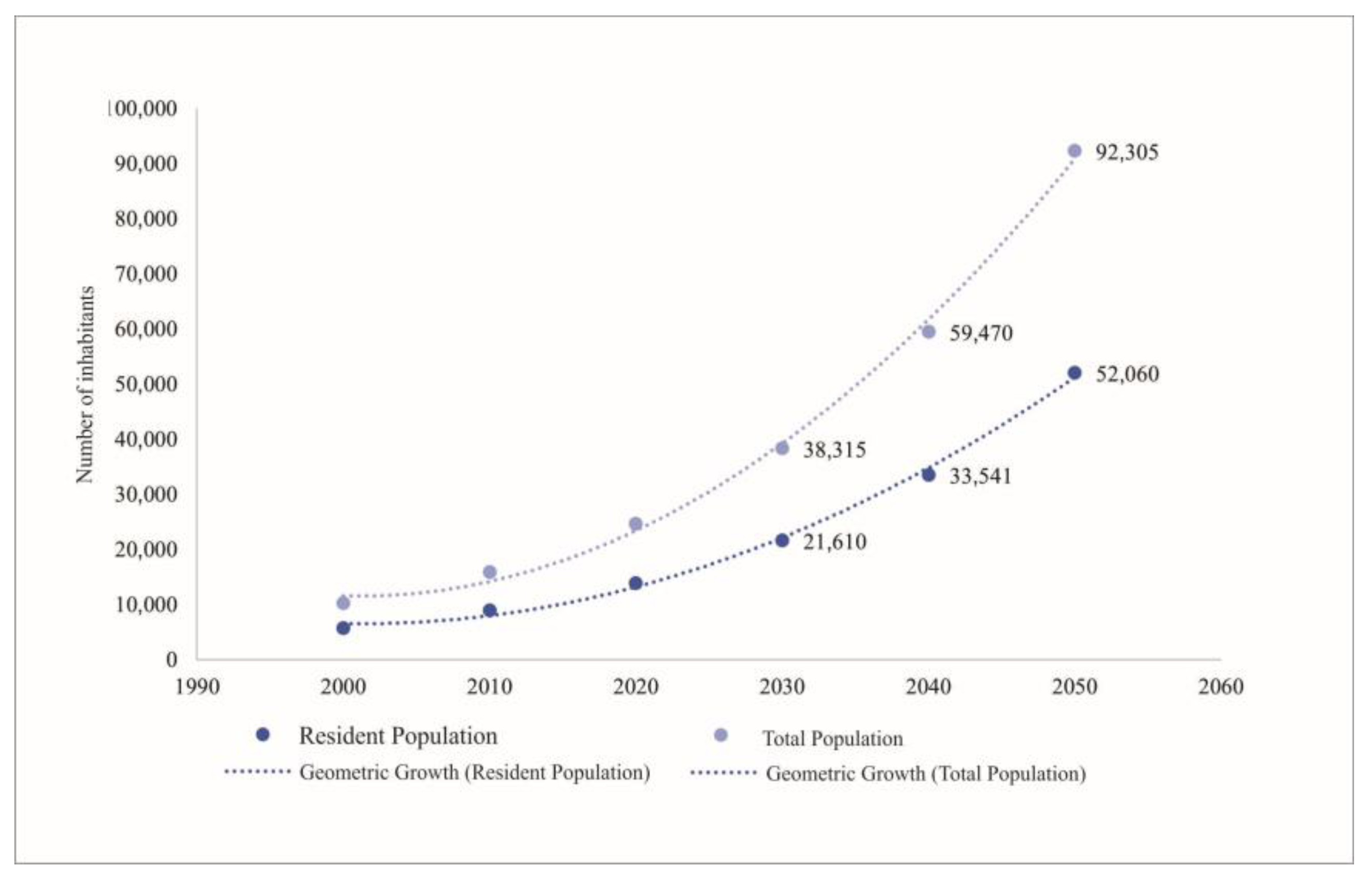

2.3. Human Population Growth Estimates for 2030, 2040, and 2050

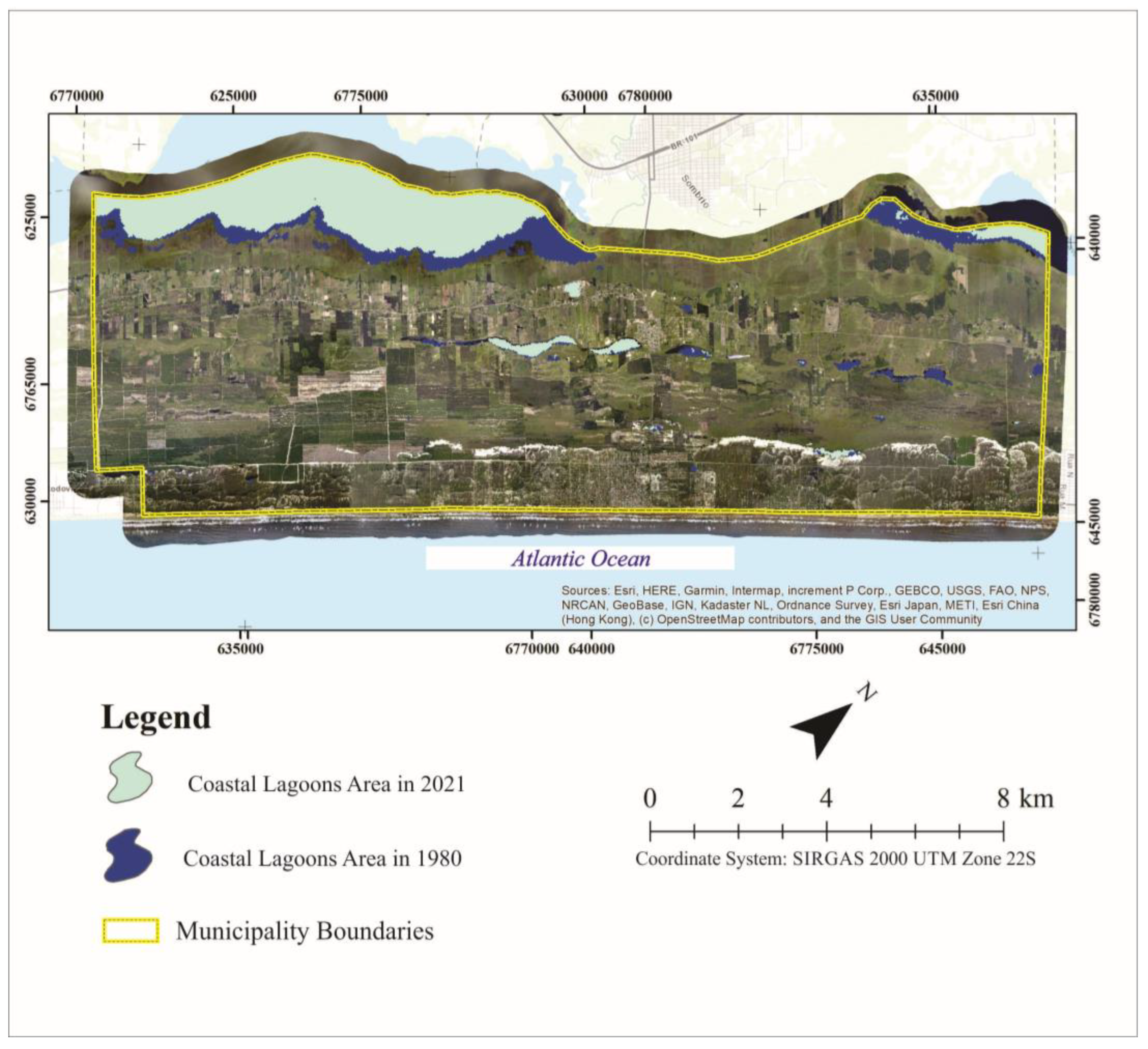

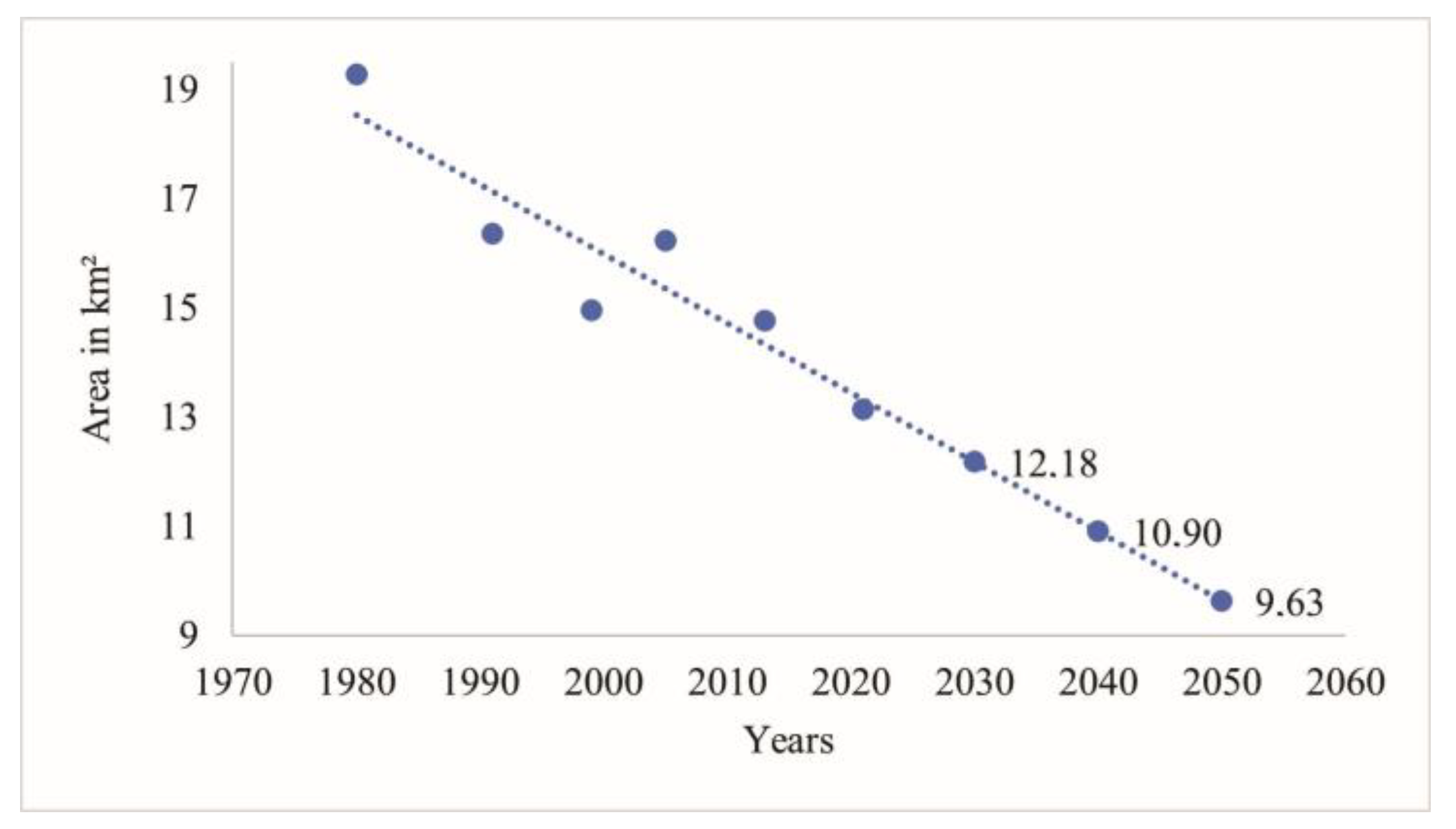

2.4. Coastal Lagoon Dynamics

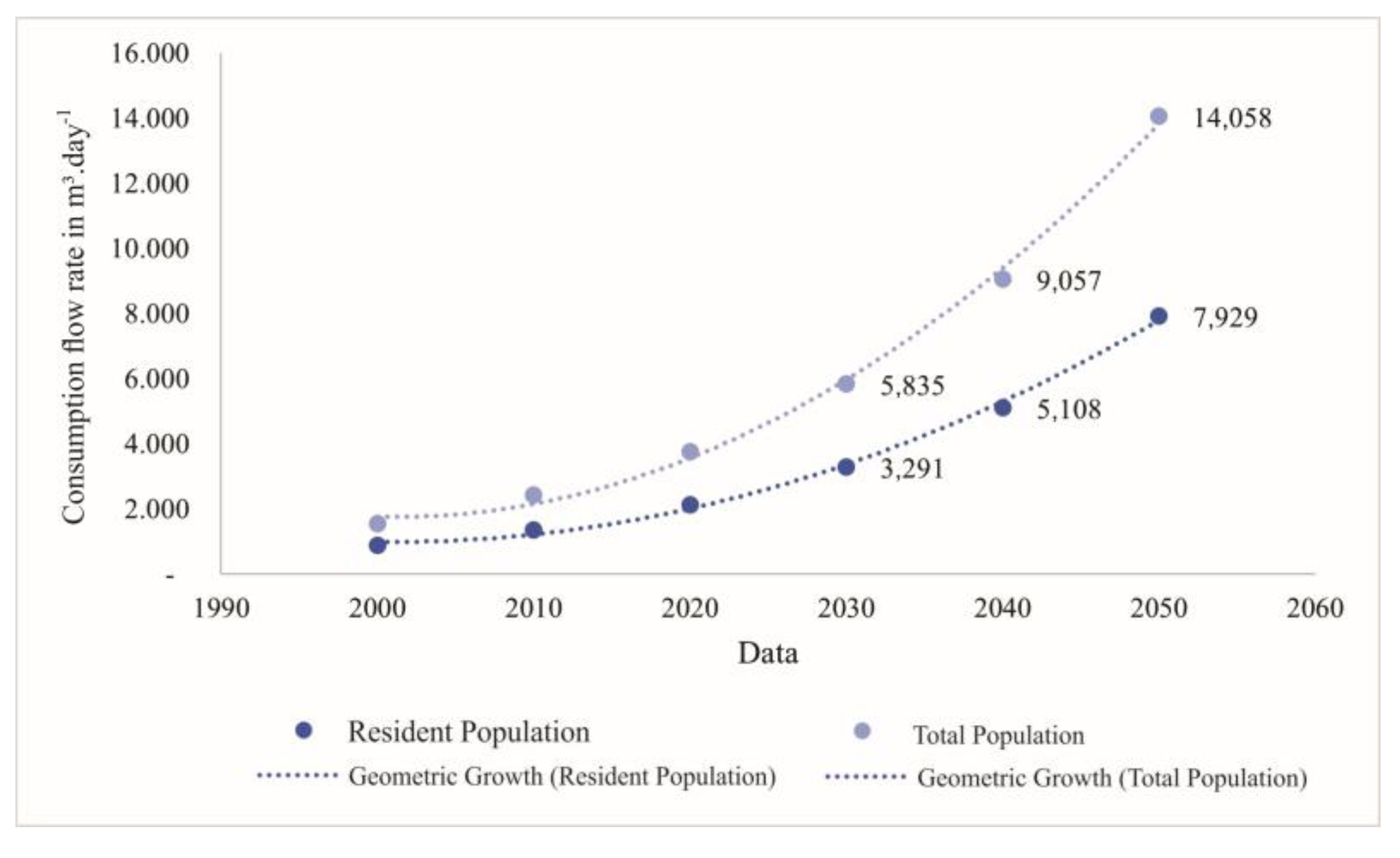

2.5. Water Consumption Projections for 2030, 2040, and 2050

3. Results

3.1. Post-Colonial Occupation of the Southern Coastal Region of Santa Catarina State, Intensity of Occupation of the Balneário Gaivota Municipality, and Regional Urban Sprawl

3.2. Human Population Growth and Growth Estimates for 2030, 2040, and 2050

3.3. Coastal Lagoon Dynamics and Water Consumption Projections for 2030, 2040, and 2050

4. Discussion

4.1. Post-Colonial Occupation of the Southern Coastal Region of Santa Catarina State, Intensity of Occupation of the Balneário Gaivota Municipality, and Regional Urban Sprawl

4.2. Coastal Lagoons Dynamics, Human Population Growth Estimates, and Water Consumption Projections for 2030, 2040, and 2050

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| PNGC | National Coastal Management Plan |

| CPRS | Coastal Plain of Rio Grande do Sul |

| BP | Before Present |

| HR10 | Hydrographic Region 10 |

| MRB | Mampituba River Basin |

| RPA | Remotely Piloted Aircraft |

| DP | Digital Processing |

| ESRI | Environmental Systems Research Institute |

| SIRGAS 2000 | Geocentric Reference System for South America |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator |

| GSD | Ground Sample Distance |

| MNDWI | Modified Normalized Difference Water Index |

| IBGE | Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística |

References

- Fawzy, S., Osman, A.I., Doran, J., Rooney, D.W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ Chem Lett 2020, 18, 2069-2094. [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K., Qasim, M.Z., Song, H., Murshed, M., Mahmood, H., Younis, I. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ Sci Pollut R 2022, 29, 42539-42559. [CrossRef]

- Benítez, S., Navarro, J.M., Mardones, D., Villanueva, P.A., Ramirez-Kushel, F., Torres, R., Lagos, N.A., 2023. Direct and indirect impacts of ocean acidification and warming on algae-herbivore interactions in intertidal habitats. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 195, 115549. [CrossRef]

- Shivanna, K.R., 2022. Climate change and its impact on biodiversity and human welfare. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy 88(2), 160-171. [CrossRef]

- Andrés, M. de., Muñoz, J.M.B., 2022. The limits of coastal and marine areas in Andalusia (Spain). A socio-ecological approach for ecosystem-based management. Land Use Policy 120, 106250. [CrossRef]

- Andrés, M. de., Barragán, J.M., Scherer, M., 2018. Urban centers and coastal zone definition: Which area should we manage? Land Use Policy 71, 121-128. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Small, C., 1998. Hypsographic demography: the distribution of human population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14009–14014 https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.95.24.14009.

- Crossland, C.J., Baird, D., Ducrotoy, J-P., Lindeboom H., 2005. The Coastal Zone—a Domain of Global Interactions. In: Crossland, C.J., Kremer, H.H., Lindeboom, H.J., Marshall Crossland, J.I., Le Tissier, M.D.A. (Eds.), Coastal Fluxes in the Anthropocene. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Ritzema, H.P., 2008. Coastal lowland development: coping with climate change: examples from the Netherlands. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Sustainable paddy farming and healthy environment. Korean INWERF Committee and ICID WG-SDTA, Changwon City, pp. 1-12. https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/coastal-lowland-development-coping-with-climate-change-examples-f (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Bazant-Fabre, O., Bonilla-Moheno, M., Martínez, M.L., Lithgow, D., Muñoz-Piña, C., 2022. Land planning and protected areas in the coastal zone of Mexico: Do spatial policies promote fragmented governance? Land Use Policy 121, 106325. [CrossRef]

- Barragán Muñoz, J.M., 2020. Progress of coastal management in Latin America and the Caribbean. Ocean & Coastal Management 105009. [CrossRef]

- Skinner L.F., 2020. Oceano, humanidade e regiões tropicais: nosso futuro depende da nossa reconexão. Journal of Human and Environment of Tropical Bays 1, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Viaud, V., Legrand, M., Squividant, H., Parnaudeau, V., André, A., Bera, R., Dupé, S., Marie Pot, M., Marianne Cerf, M., Revelin, F., Toffolini, Q., Levain, A., 2023. Farming by the sea: A qualitative-quantitative approach to capture the specific traits of coastal farming in Brittany, France. Land Use Policy 125, 106493. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y., Dunn, R.J.K., Young, R.A., Connolly, R.M., Dale, P.E.R., Dehayr, R., Lemckert, C.J., Mckinnon, S., Powell, B., Teasdale, P.R., Welsh, D.T., 2006. Impact of urbanization on coastal wetland structure and function. Austral Ecol 31, 149-163. [CrossRef]

- Varnell, L.M., Evans, D.A., Havens, K.J., 2003. A geomorphological model of intertidal cove marshes with application to wetland management. Ecol Eng 19(5), 339–347. [CrossRef]

- Watywarawan, A., Zenere, J.L., Touguinha, G.C., da Silva, L.P., Bilhalva, D.N., Dias, J.F., Zocche, J.J., 2025. Toxic trace elements in wild mussels Perna perna (Linnaeus, 1758) in two Brazilian rocky shores of the South Atlantic Ocean. Mar Pollut Bull 216:118012. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.C., Oliveira, M.R.L., 2015. Plano nacional de gerenciamento costeiro: 25 anos do gerenciamento costeiro no Brasil. Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Brasília. https://gerenciamentocosteiro.furg.br/images/Materiais/PNGC-25-anos.pdf (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Brouwer, R., van Ek, R., 2004. Integrated ecological, economic and social impact assessment of alternative flood control policies in the Netherlands. Ecol Econ 50(1-2), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.P., 2000. Wetland loss and biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol 14(1), 314-317. [CrossRef]

- Ballut-Dajud, G.A., Sandoval Herazo, L.C., Fernández-Lambert, G., Marín-Muñiz, J.L., López Méndez, M.C., Betanzo-Torres, E.A., 2022. Factors affecting wetland loss: A review. Land 11(3), 434. [CrossRef]

- Kominoski, J.S., Gaiser, E.E.; Castaneda-Moya, E.; Davis, S.E.; Dessu, S.B.; Julian II, P.; Lee, D.Y.; Marazzi, L.; Rivera-Monroy, V.H.; Sola, A.; Stingl, U.; Stumpf, S.; Surratt, D.; Travieso, R.; Troxler, T.G., 2020. Disturbance legacies increase and synchronize nutrient concentrations and bacterial productivity in coastal ecosystems. Ecology 101(5), e02988. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Zhang, C., Wang, V., Yang, C., Zhou, W., 2025. Spatio-temporal variations of land use carbon emissions and its low carbon strategies for coastal areas in China with nighttime lighting data. J Environ Manage 385, 125651. [CrossRef]

- Gianuca, K. de S., Tagliani, C.R.A., 2012 Análise em um sistema de informação geográfica (SIG) das alterações na paisagem em ambientes adjacentes a plantios de pinus no Distrito do Estreito, município de São José do Norte, Brasil. Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada—Journal of Integrated Coastal Zone Management 12(1), 43-55. [CrossRef]

- Santinhos, A.J., Martinho, A.P., Caeiro, S., 2014. Perceção das populações locais face à sustentabilidade dos serviços das zonas costeiras: o caso da Lagoa de Santo André, Portugal. Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada—Journal of Integrated Coastal Zone Management 14(3), 413-427. [CrossRef]

- Asmus, M.L., Kitzmann, D., Laydner, C., Tagliani, C.R.A., 2006. Gestão costeira no Brasil: Instrumentos, fragilidades e potencialidades. Gerenciamento Costeiro Integrado 1, 52-57. https://repositorio.furg.br/bitstream/handle/1/2053/GEST%C3O%20COSTEIRA%20NO%20BRASIL.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Lei, 1988. Lei Nacional de Gerenciamento Costeiro. Presidência da República. (7.661/88). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l7661.htm (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Rosa, M.L.C. da C., Barboza, E.G., Abreu, V. dos. S., Tomazelli, L.J., Dillenburg, S.R., 2017. High-frequency sequences in the Quaternary of Pelotas Basin (coastal plain): a record of degradational stacking as a function of longer-term base-level fall. Braz J Geol 47(2), 183-207. [CrossRef]

- Tomazelli, L., Villwock, J., 1991. Geologia do sistema lagunar holocênico do litoral norte do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Pesquisas em Geociências 18(1), 13-24. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.E., Marchett, C.A., Schuh, S.M., Ahlert, S., Lanzer, R.M., 2014. Morphological characterization of eighteen lakes of the north and middle coast of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 26(2), 199-214. [CrossRef]

- Tomazelli, L., Villwock, J., 1992. Considerações sobre o ambiente praial e à deriva litorânea de sedimentos ao longo do litoral norte do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Pesquisas em Geociências 19(1), 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Tomazelli, L.J., Villwock, J.A., 2005. Mapeamento geológico de planícies costeiras: o exemplo da costa do Rio Grande do Sul. Gravel 3(1), 109-115. https://www.ufrgs.br/gravel/3/Gravel_3_11.pdf (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Bitencourt, N. de L. da R., Lalane, H. de C., Rocha, I. de O., 2011. O processo de ocupação dos espaços costeiros do extremo sul de Santa Catarina, Brasil. Revista Geográfica de América Central (Número Especial EGAL), 1-15. https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/geografica/article/view/2531/2420 (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Bitencourt, N. de L. da R.; Soriano-Sierra, E.J.; Ernandorena, P.R., 2013. Ações para conter impactos ambientais na orla marítima: Caso do município de Balneário Gaivota. OLAM-Ciência e Tecnologia 1(1), 183-203. https://www.periodicos.rc.biblioteca.unesp.br/index.php/olam/article/view/7535/5609 (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Cohenca, D., Scherer, M.E.G., Vieira, C.A.O., 2017. Ocupação na zona costeira do sul de Santa Catarina: uma análise histórica de vetores e processos. Geosul 32(64), 47-65. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.R.S., Nodari, E.S., 2012. “O que é da natureza não se mexe”: memória e degradação ambiental na Lagoa de Sombrio SC (1960-2010). História Oral 15(1), 55-80. [CrossRef]

- Porcher, L.C.F., Poester, G., Lopes, M., Schonhofen, P., Silvano, R.A.M., 2010. Percepção dos moradores sobre os impactos ambientais e as mudanças na pesca em uma lagoa costeira do litoral sul do Brasil. Bol Inst Pesca 36(1), 61-72. https://institutodepesca.org/index.php/bip/article/view/903/884 (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Secretaria de Estado do Desenvolvimento Econômico Sustentável, 2017. Plano estadual de recursos hídricos de Santa Catarina—PERH/SC. Santa Catarina: Prognóstico das demandas hídricas de Santa Catarina. https://www.aguas.sc.gov.br/jsmallfib_top/DHRI/Plano%20Estadual/etapa_c/PERH_SC_Recomendacoes_enquadramento_CERTI-CEV_2017_final.pdf (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Villwock, J.A., 1984. Geology of the coastal Province of Rio Grande do Sul, Southern Brazil. A synthesis. Pesquisas em Geociências 16(16), 5-49. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.E., Pereira, R., Lanzer, R., 2009. Atlas socioambiental dos Municípios de Mostardas, Tavares, São José do Norte e Santa Vitoria do Palmar. Educs. Caxias do Sul. https://www.ucs.br/educs/arquivo/ebook/atlas-socioambiental-dos-municipios-de-mostardas-tavares-sao-jose-do-norte-santa-vitoria-do-palmar/ (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Klein, A.H. da F., Short, A.D., Bonetti, J., 2016. Santa Catarina beach systems. In: Klein, A.H. da F., Short, A.D., Bonetti, J. (Eds.), Brazilian beach systems, Springer, Switzerland pp. 465–506. [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A., Starpe, J.L., Sentelhas, P.C., Gonçalves, J.L.M., Sparovek, G., 2013. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol Z 22(6), 711-728. [CrossRef]

- Secretaria do Meio Ambiente e Infraestrutura, 2018. L050—Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Mampituba. https://www.sema.rs.gov.br/l050-bh-mampituba (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Sistema de Informações de Recursos Hídricos de Santa Catarina, 2018. Bacias Hidrográficas do Estado. https://www.aguas.sc.gov.br/jsmallfib_top/DHRI/bacias_hidrograficas/bacias_hidrograficas_sc.pdf (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Lei, 1998. Dispõe sobre a caracterização do Estado em 10 Regiões Hidrográficas. (10.949). https://www.aguas.sc.gov.br/jsmallfib_top/DHRI/Legislacao/Lei-Estadual-10949-1998.pdf (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Bitencourt, N. de L. da R., Rocha, I. de O., 2014. Percepção das populações costeiras sobre os efeitos dos eventos adversos no extremo sul de Santa Catarina, Brasil. Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada—Journal of Integrated Coastal Zone Management 14(1), 15-25. [CrossRef]

- Meneses, P.R., Almeida, T. de., 2012. Distorções e correções dos dados da imagem. In: Meneses, P.R., Almeida, T. de. (Orgs.), Introdução ao processamento digital de imagens de sensoriamento remoto. UnB/CNPq, Brasília, pp. 81-102. https://memoria.cnpq.br/documents/10157/56b578c4-0fd5-4b9f-b82a-e9693e4f69d8 (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Silva, C.A. da., Duarte, C.R., Souto, M.V.S., Santos, A.L.S. dos., Amaro, V.E., Bicho, P.B., Sabadia, J.A.B., 2016. Avaliação da acurácia do cálculo de volume de pilhas de rejeito utilizando VANT, GNSS e LIDAR. Bol Ciênc Geod 22(1), 73–94. [CrossRef]

- Ladwig, N.I.; Pereira, J.R.; Neves, G.R., 2021. Qualidade posicional planimétrica de ortomosaico obtido com uso de aeronave remotamente pilotada—RPA. Geografía y Sistemas de Información Geográfica 21, 1–14. https://87538a9a-4129-4498-961e-1bc765cd62c3.filesusr.com/ugd/79758e_b21dea93fe884b7f8c2a19d8ffca7ca0.pdf (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Câmara, G., Carvalho, M.S., 2004. Análise espacial de eventos. In: Druck, S., Carvalho, M.S., Câmara, G., Monteiro, A.V.M. (Eds.), Análise Espacial de Dados Geográficos. EMBRAPA, Brasília, pp. 1-15. http://www.dpi.inpe.br/gilberto/livro/analise/cap2-eventos.pdf (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Souza Jr, C.M., Shimbo, J.Z, Rosa, M.R., Parente, L.L., Alencar, A.A., Rudorff, B.F.T, Hasenack, H., Matsumoto, M., Ferreira, L.G., Souza-Filho, P.W.M., Oliveira, S.W., Rocha, W.F., Fonseca, A.V., Marques, C.B. Diniz, C.G., Costa, D., Monteiro, D., Rosa, E.R., Vélez-Martin, E., Weber, E.J., Lenti, F.E.B., Paternost, F.F., Pareyn, F.G.C., Siqueira, J.V., Viera, J.L., Ferreira Neto, L.C., Saraiva, M.M., Sales, M.H., Salgado, M.P.G., Vasconcelos, R., Galano, S., Mesquita, V.V., Azevedo, T., 2020. Reconstructing three decades of land use and land cover changes in Brazilian biomes with Landsat archive and earth engine. Remote Sens 12(17), 2735. [CrossRef]

- UN United Nations, 2015. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development. The 17 Goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed 24 April 2025).

- IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2022. Censo Demográfico. Panorama do senso 2022. https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br/panorama/ (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Lei, 1995. Cria o Município de Balneário Gaivota, e adota outras providências. (10.054). http://leis.alesc.sc.gov.br/html/1995/10054_1995_Lei.html (accessed 23 April 2025).

- McFeeters, S.K., 1996. The use of the normalized difference water index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int J Remote Sensing 17(7), 1425-1432. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., 2006. Modification of normalized difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. International journal of remote sensing 27(14), 3025-3033. [CrossRef]

- Ministério do Desenvolvimento Regional, 2020. Sistema Nacional de Informações sobre Saneamento: 25º Diagnóstico dos Serviços de Água e Esgoto–2019. SNS/MDR, Brasilia. https://www.gov.br/mdr/pt-br/assuntos/saneamento/snis/diagnosticos-anteriores-do-snis/agua-e-esgotos-1/2019/2-Diagnstico_SNIS_AE_2019_Republicacao_31032021.pdf (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Lopes, A.R.S., 2011. A Lagoa do Sombrio corre que desaparece: uma história ambiental da degradação e o atual debate sobre a preservação da Lagoa de Sombrio. (Master Degree) Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC). http://repositorio.ufsc.br/xmlui/handle/123456789/95285 (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Holanda, S.B. de., 1994. Caminhos e fronteiras. Companhia das Letras, São Paulo, 374p.

- Reitz, R., 1988. Paróquia de Sombrio: ensaio de uma monografia paroquial. Paróquia Santo Antonio de Pádua, Sombrio, 194 pp.

- Farias, V.F. de., 2000. Sombrio 85 anos: natureza, história e cultura para o ensino fundamental. Ed. do autor, Sombrio, 326 pp.

- Bertolo, L.S., Lima, G.T.N.P., Santos, R.F., 2012. Identifying change trajectories and evolutive phases on coastal landscapes. Case study: São Sebastião Island, Brazil. Landscape Urban Plan 106(1), 115-123. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, A.C.R., 2007. Contribuições para a gestão da zona costeira do Brasil: elementos para uma geografia do litoral brasileiro. Annablume, São Paulo, 232 pp.

- Pereira, R.M.F. do A., 2003. Formação sócio-espacial do litoral de Santa Catarina (Brasil): gênese e transformações recentes. Geosul, 18(35), 99–129. https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/geosul/article/view/13604/12471 (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Lopes, E.B., Ruiz, T.C.D., Anjos, F.A.D., 2018. A ocupação urbana no Litoral Norte do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil, e suas implicações no turismo de segunda residência. Urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana—Brazilian Journal of Urban Management 10 (2), 426-441. [CrossRef]

- Marchett, C.A., 2017. Caracterização morfológica das lagoas de Osório, norte da planície costeira do Rio Grande do Sul. (Master Degree), Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS). https://repositorio.ucs.br/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11338/3378/Dissertacao%20Cassiano%20Alves%20Marchett.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Schwarzbold, A.; Schäfer, A., 1984. Gênese e morfologia das lagoas costeiras do Rio Grande do Sul-Brasil. Amazoniana 9(1), 87-104. https://archive.org/details/amazoniana-9-001-087-104 (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Wang, Z., Lu, Z., Ma, J., Huang, G., An, C., 2024. Assessing the water metabolism of coastal urban areas based on the water mass balance framework across time periods: A case study of Cape Town, South Africa. Ocean Coasta Manage, 259, 107434. [CrossRef]

- Gebeyehu, A.K., Snelder, D., Sonneveld, B., 2023. Land use-land cover dynamics, and local perceptions of change drivers among Nyangatom agro-pastoralists, Southwest Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 131, 106745. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.C.F., Novo, E.M.L.M., Martins, V.S., 2019. Introdução ao sensoriamento remoto de sistemas aquáticos: Princípios e aplicações. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, São José dos Campos, 178 pp. http://www.dpi.inpe.br/labisa/livro/res/conteudo.pdf (accessed 23 April 2025).

- Gomes, M.P., 2024. The convergence of antibiotic contamination, resistance, and climate dynamics in freshwater ecosystems. Water 16(18), 2606. [CrossRef]

- Heller, L., Pádua, V.L. de., 2010. Abastecimento de água para consumo humano. Editora UFMG, Belo Horizonte, 859 pp.

- Chen, N., Hong, H., Gao, X., 2021. Securing drinking water resources for a coastal city under global change: scientific and institutional perspectives. Ocean Coast Manag. 207, 104427. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.C., Dunn, G., Hammer, K., Novalia, W., de Haan, F.J., Brown, L., Brown, R.R., Lloyd, S., Urich, C., Wong, T.H.F., Chesterfield, C., 2020. Water Sensitive Cities Index: a diagnostic tool to assess water sensitivity and guide management actions. Water Res. 186, 116411. [CrossRef]

- Lozoya, J.P., 2022. As zonas costeiras no antropoceno. In: Polette, M., Bombana, B., Longarete, C., Conde, D. (Eds.), Praias: Princípios e diretrizes para Gestão. Autor e editor, Itajaí, pp. 12-19. http://www.profagua.uerj.br/livros/Praias_pricipios%20e%20diretrizes%20para%20gestao.pdf (accessed 24 April 2025).

- Hariram, N.P., Mekha, K.B., Suganthan, V., Sudhakar, K. 2023). Sustainalism: An integrated socio-economic-environmental model to address sustainable development and sustainability. Sustainability 15(13), 10682. [CrossRef]

- Tundisi, J.G., 2006. Novas perspectivas para a gestão de recursos hídricos. Revista USP 70, 24-35. [CrossRef]

| Years | Months | Rainfall (mm) | Area (km2) | Percentage of Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | November | 109.8 | 19.3 | 0 |

| 1991 | January | 102.2 | 16.4 | 15.1 |

| 1999 | January | 83.1 | 14.9 | 22.4 |

| 2005 | November | 128.9 | 16.2 | 15.8 |

| 2013 | December | 98.7 | 18.8 | 23.4 |

| 2021 | January | 140.5 | 13.1 | 31.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).