1. Introduction

The Atlantic puffin (

Fratercula arctica) is a charadriiform bird renowned for its exceptional diving capabilities and transoceanic migratory behaviour. Phylogenetic analyses have identified several subspecies that nest in various geographical locations, including northern Europe, Greenland, and North America [

1,

2,

3].

Significant population declines of European Atlantic puffins have been linked to reduced recruitment and prey availability [

2,

4,

5,

6]. In Europe, juvenile puffins tend to migrate farther south than adults. These movements contribute to the dispersion of the species during migration, although episodes of mortality associated with migration may be a normal occurrence in the dynamics of Atlantic puffin populations [

5,

7]. However, there is limited literature on the pathological investigation of an unusual mortality events in wild Atlantic puffins [

2,

8,

9].

Digenean trematodes of the genus

Renicola are relatively common parasites found in the urinary tract of marine birds, including Atlantic puffins [

10,

11]. The adult fluke parasitizes the urinary system of seabirds, but the complex life cycle of the helminth requires several intermediate hosts before reaching the avian urinary system [

11]. The role of Renicola infestation in the development of renal lesions in Atlantic puffins remains unclear, as the presence of the trematode is frequent but not typically associated with disease according to previous reports [

11,

12].

This study presents the pathological findings of Atlantic puffins involved in an unusual mortality event observed from late 2022 to early 2023 along the coast of the Canary Islands. This event was temporally and geographically associated with severe adverse environmental (climatic) conditions during migration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Necropsy

Between January 4th and February 14th, 2023, a total of 223 Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) were submitted to the University Institute of Animal Health and Food Security at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria for investigation of the cause of death. The necropsies were performed in cooperation with the “Dirección General de Lucha Contra el Cambio Climático y Medio Ambiente,” as part of the Canarian Network for the Surveillance of Wildlife Health (Orden Nº134/2020 of May 26th, 2020).

The animals were found at various points along the coast of the archipelago. Carcasses were submitted by various entities, including local authorities, environmental police, and wildlife hospitals.

The degree of decomposition was assessed upon reception, with a numeric value assigned between 1 and 5 (1 very fresh, 2 fresh, 3 decomposed, 4 very decomposed, 5 skeletal reduction). A complete necropsy was performed on animals with decomposition codes of 1-3. Body score (BS) was determined using a numeric scale from 1 to 3 (1 cachexia, 2 thin, 3 optimal) based on the evaluation of muscle mass, and subcutaneous and visceral fat (a modification of the body score presented by Burton et al. [

13]. Biometric data were obtained from each individual, including total body length, wingspan, tarsus, culmen, and total body weight. When the feathers of the animal were covered by sand or wet, the weight was considered not representative and excluded from the biometry (n=87). During the necropsy, the sex and development of the gonads were determined, and individuals were classified as mature or immature.

Tissue samples for histological examination included adrenal glands, air sacs, bursa of Fabricius, encephalon, esophagus, eyes, gonads, heart, intestine, kidneys, liver, lungs, proventriculus, sciatic nerves, skeletal muscle, skin, spleen, thymus, thyroid glands, trachea, ureters, ventriculus, and the whole head. Samples were fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 hours, routinely processed, and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4 μm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological analysis. Microscopic examination was conducted by two certified veterinary pathologists (OQC and AF).

2.2. Molecular Analysis

For molecular analysis, a simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction with the magnetic bead method using a robotic platform was performed, following the manufacturer’s protocol for the ZYMO DNA/RNA extraction kit (ZYMO Research). To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the extraction process, both a negative control (nuclease-free water) and a positive control, were included in the protocol.

The animals were also tested for highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) using a real time semi-quantitative (sq) PCR (polymerase chain reaction) [

14].

Genomic DNA was extracted using preserved tissue portions. PCR screening of DNA was based on cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) using the primers CO1-R and JB3.

The PCR products that presented the expected size (650-bp) were sequenced at Macrogen (Madrid, Spain) with primers CO1-R and JB3 [

15]. To see a detailed explanation of the molecular analysis see Pino-Vera et al. [

16].

These animals were also tested for highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) using a real time semi-quantitative (sq) PCR (polymerase chain reaction) (Spackman et al., 2013).

3. Results

3.1. Necropsy

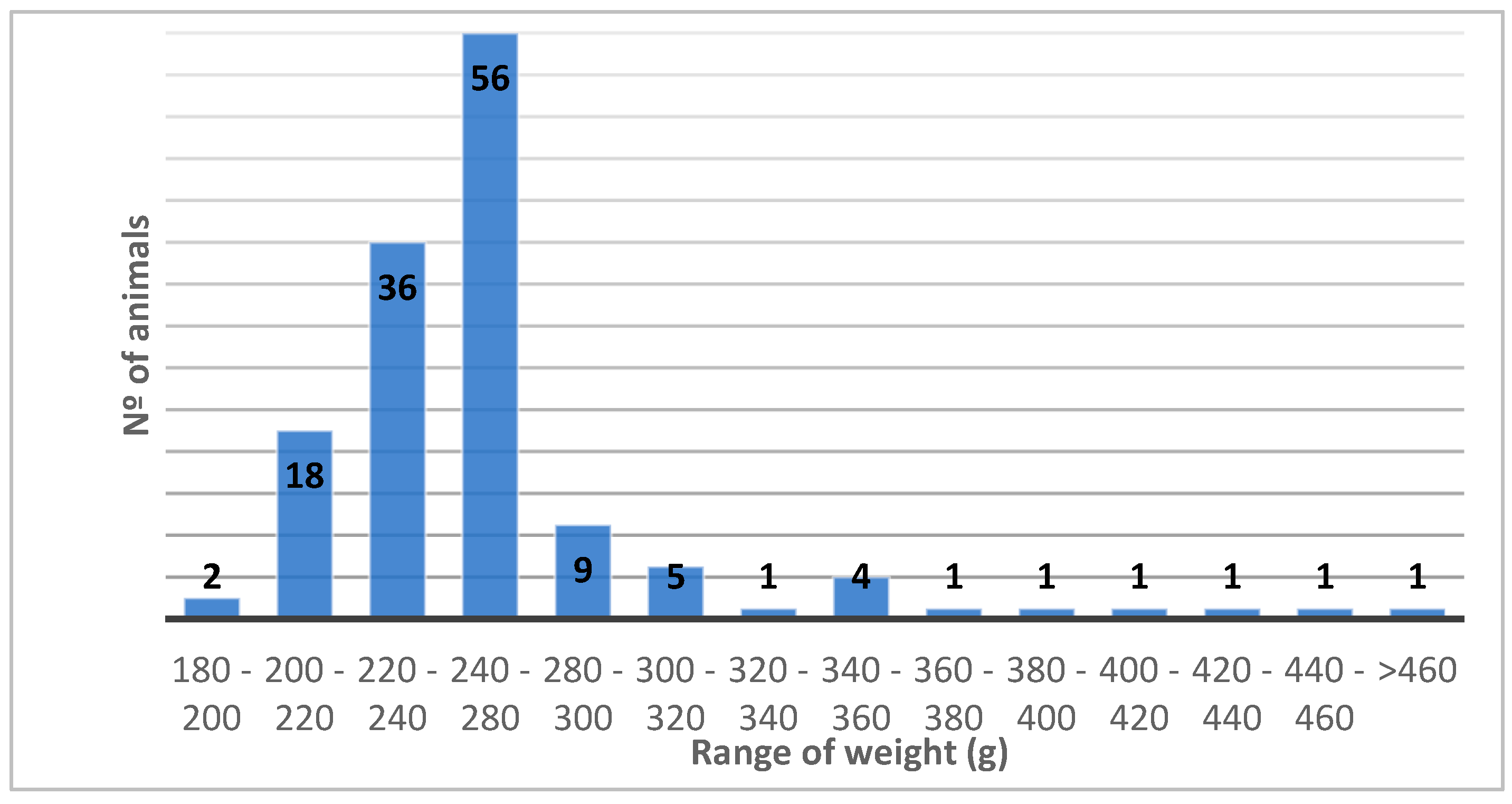

The mean body weight of 136 individuals was 256.0±47.4 g which is much lower that the reported weight for the species wchich ranges from 310 to 550 g [

1].

Figure 1 represents the weight distribution of the analyzed animals.

Necropsies were performed on 147 animals. The sex could be determined in 114 individuals, resulting in 73 females (64%) and 41 males (35.9%). Both juveniles (n=35) and adults (n=67) were present.

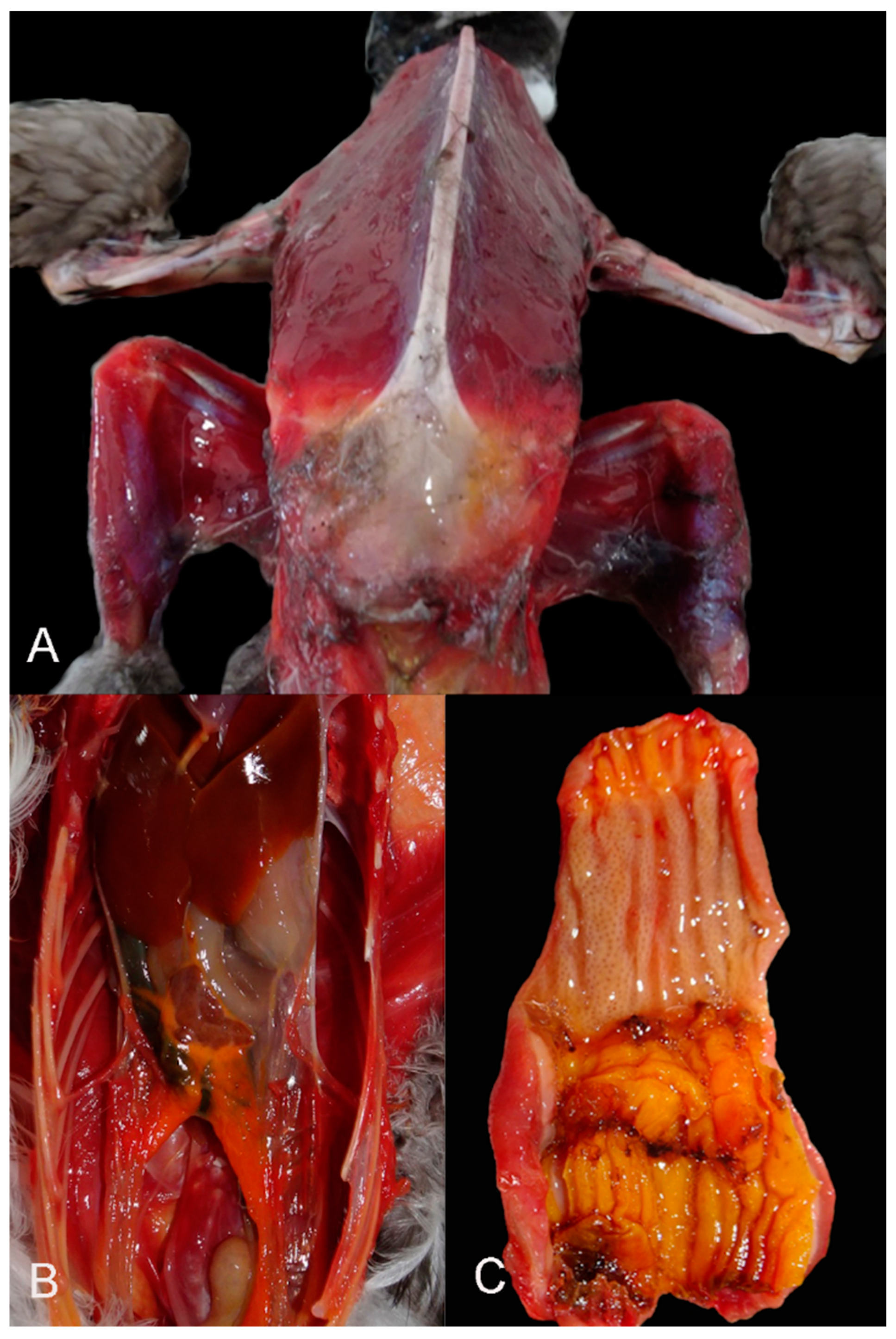

The most consistent gross findings were generalized muscle atrophy (

Figure 2A) and serous fat atrophy (

Figure 2B). These conditions were evident in 97.9% (95/97) of the individuals for which body score (BS) could be determined. The BS ranged from cachectic (BS1, n=46) to thin (BS2, n=49), with only two individuals having a BS of 3. In 50 animals, the BS could not be determined due to advanced decomposition or predation. In all animals, the ventriculus and proventriculus were empty (

Figure 2C), except for the frequent presence of microplastics (i.e., fragments of plastic less than 5 mm) in the ventriculus.

Thirteen animals exhibited lesions indicative of acute blunt-force trauma, including skin abrasions and lacerations, subcutaneous hematomas, internal hemorrhages, and bone fractures.

3.2. Histopathology

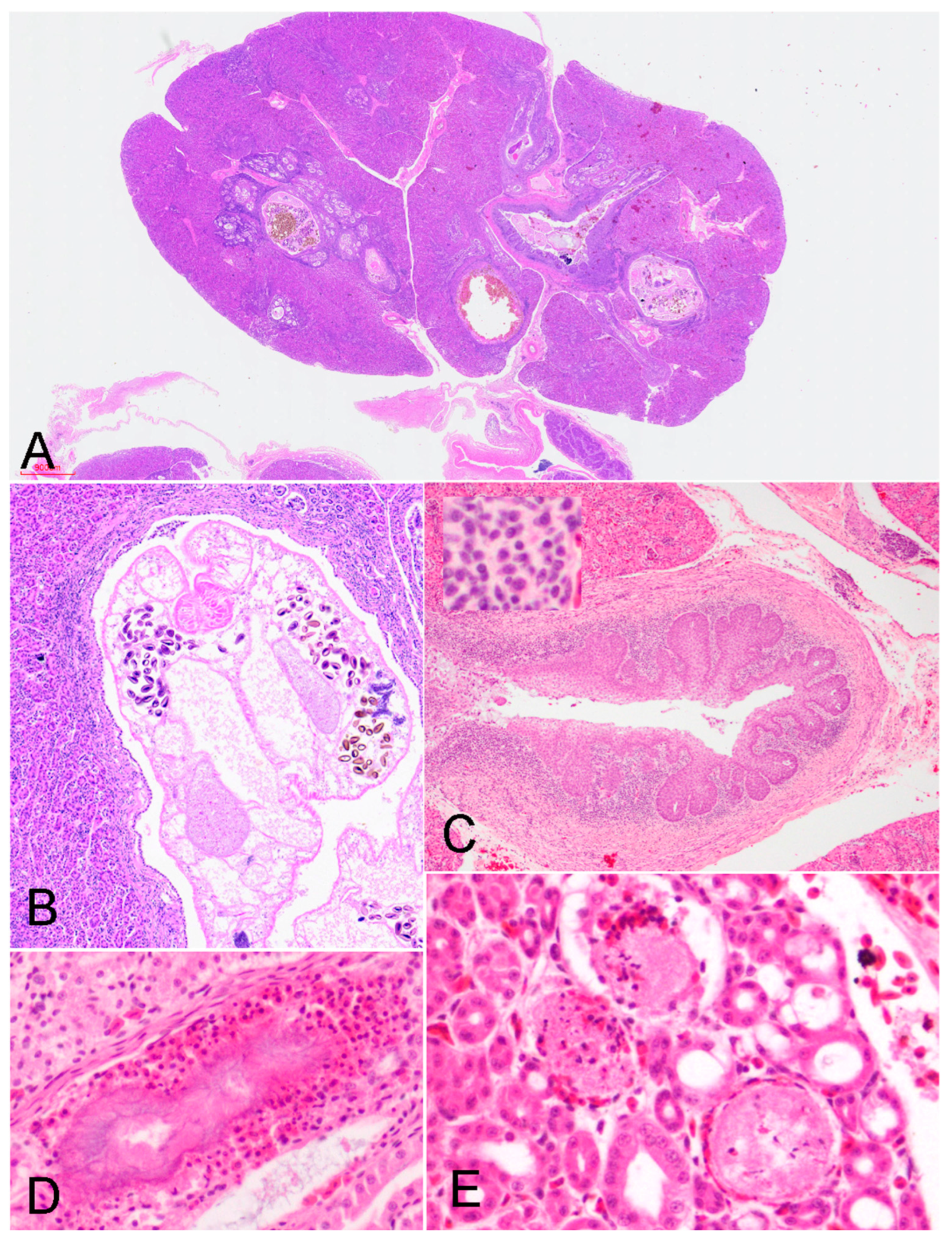

Histological analysis was performed on 81 animals, and the findings are summarized in

Supplementary Table S1. The primary lesions were found in the kidneys of all the animals analyzed and included dilation and inflammation of the primary ureter branch and medullary cones, with occasional presence of intraluminal helminths (Figures 3A and 3B). Marked epithelial hyperplasia was detected in 88.8% (72/81) of the cases, with concurrent moderate-to-severe squamous metaplasia in 18.5% of individuals (n=15) (

Figure 3C). The collecting ducts of the medullary cone were dilated, containing abundant cellular debris. There was severe lymphoplasmacytic inflammation of the subepithelial connective tissue, with occasional heterophils and macrophages (inset of

Figure 3C). While ureteritis was noted in 100% (n=81) of the animals, it ranged from mild (n=3) to severe (n=54). Concomitant interstitial lymphoplasmacytic nephritis was observed in 59.3% (48/81) of cases. In 82.7% of animals (67/81), there was urate deposition in the form of crystals or spheres in the renal tubules (

Figure 3D). Acute tubular necrosis was noted in 8.6% (7/81) of individuals (

Figure 3E). Adult trematodes or their eggs were detected in the collecting ducts or the primary branch of the ureter in 27.2% of individuals (22/81).

Additional relevant histological findings were noted in the skeletal muscle. The pectoral muscles of 30 individuals were evaluated, all of which showed severe diffuse myocyte atrophy. Acute to subacute lesions were observed in the pectoral muscles of 19 animals, including moderate to severe acute degeneration and segmental necrosis of myocytes, with occasional presence of macrophages phagocytizing cellular debris.

3.3. Molecular Analysis

All the animals resulted negative for highly pathogenic avian influenza.

The recovered digeneans were identified as belonging to the genus Renicola, 1904 (Renicolidae) [

10,

16,

17]. with morphoanatomical characteristics resemble those of Renicola sloanei [

11]. From the PCR a fragment of 527 bp was obtained for the region of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene. The BLAST analysis showed greater homology with Renicola sloanei (Accession Number: MK463857, Query Cover: 99%, Identity: 87.68%). The 527 bp nucleotide sequence obtained in this study was submitted to the GenBank database (accession number OQ992508). To see detailed description of the parasite morphology and molecular identification see Pino-Vera et al. [

15].

4. Discussion

The Atlantic puffin is a rare visitor to the Canarian coast. As part of the Canarian Network for the Surveillance of Wildlife Health, only four animals were submitted for necropsy between 2021 and 2022. The atypical beaching of hundreds of Atlantic puffins in January 2023 alerted the authorities and the public, prompting this investigation.

Burnham et al. [

7] reported different migratory movements for male and female, with females migrating with more segregation and a more southern distribution than males. This difference in migratory patterns may explain why we observed more females than males involved in this mortality event.

There are several populations of Atlantic puffins that may show significant variation in body mass [

1,

3]. However, the expected weight for the species should be around 380 to 550 g, although there are reports of the largest Atlantic puffin weighing over 700 g [

2]. Variations can occur according to sex (males are slightly heavier), breeding period, or migration [

18]. The biometric results indicate that most of our cases were below the normal range, with a median body mass of 256.0 g. This is drastically lower than the reported healthy weight for different populations of wild Atlantic puffins [

1,

2,

3]. This low body mass is indicative of a systemic alteration, such as malnutrition or illness.

Regarding illness, we excluded highly pathogenic avian influenza but confirmed a high prevalence of renal lesions associated with infestation by

Renicola sloanei [

16].

R. sloanei has been associated with mild lesions in different species of penguins (Spheniscidae), the common murre (

Uria aalge), and the Manx shearwater (

Puffinus puffinus) [

10,

19].

In previous studies in the United Kingdom, a high rate of infection was detected in Atlantic puffins, but the histopathology usually revealed an apparent lack of host-tissue reaction, dilation of ducts due to the presence of the worms, and epithelial erosion [

11].

There is a single finding of an unidentified species of the genus

Renicola in Britain [

12] causing “nephrosis” in Atlantic puffins. Wright [

11] also described a case of an exhausted Atlantic puffin found in the London Docks that shortly died, with the cause of death determined as renal insufficiency. Approximately 40 flukes were found in the kidney, corresponding to

Renicola sp. closely related to

Renicola sloanei.

It would be expected that a well-adapted host-parasite relationship would result in minimal to mild lesions. In literature reports of

R. sloanei, the trematode is visualized inside the ureter with no associated inflammatory reaction [

10,

11]. In a pathological study of

Fratercula cirrhata, renal trematodiasis was not found to be a cause of mortality [

20]. Although histologically we detected the trematode in only 27.2% of cases, we observed moderate to severe lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory reactions in 96.3% of the puffins. This may suggest a much higher degree of infestation, not detected during routine histopathology, although other causes cannot be ruled out. The trematode is relatively small (around 1600 μm), and adults may be located anywhere in the urinary tract, including ureters or main ureteral branches of the different renal divisions [

11]. Careful investigation of the ureters during gross examination, and the inclusion of representative samples of different renal divisions, as well as ureters for histopathology, may increase the chance of detecting the trematode. However, molecular analysis with the amplification of the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 gene may be more sensitive for detecting the parasite in renal tissue. Clarification of the best diagnostic method for this condition merits further investigation.

Two important factors in exerting density-dependent effects are host immune responses and competitive interactions between trematodes. Both these factors may lead to host mortality as trematode density increases [

21]. The nutritional status of birds can influence parasite dynamics and parasite virulence, with undernourished birds having more parasites causing more tissue damage [

22].

Vitamin A deficiency in avian species is a well-recognized syndrome causing squamous metaplasia of stratified epithelium in various body locations, including conjunctiva, lacrimal and salivary glands, esophageal glands, respiratory and ureteral epithelium [

23]. We observed moderate grades of squamous metaplasia of the ureteral epithelium in 18.5% of the analyzed animals. Chronic ureteral irritation caused by the presence of the trematode is one important predisposing cause for squamous metaplasia [

19]. However, starvation, in which hypovitaminosis and dehydration coexist, may be another relevant component for the development of the reported renal lesions. Dehydration may rapidly occur in a chronically debilitated and starved marine bird with renal trematodiasis and a partially obstructed urinary tract. Dehydration can induce hypovolemic shock, renal gout, and ultimately death. More studies are needed to understand the pathogenesis of nephropathy in chronically debilitated marine birds with

Renicola sp. parasitism.

Mass mortality of tufted puffins (

Fratercula cirrhata) and Atlantic puffins has been attributed to starvation [

2,

8,

9]. Our mortality event shares some similarities, such as fat and muscle atrophy, but differs in the high presence of renal lesions. We hypothesize that renal lesions were exacerbated in these Atlantic puffins due to malnutrition [

24]. It should be noted that the mortality event coincided with the presence of a snowstorm extending from the North Atlantic to Spain (Storm Fein and Gérard, January 2023), which could have displaced the animals far from their feeding areas [

25]. The lesions described in the skeletal muscle and the relatively high prevalence of trauma would be expected in animals suffering from exertion after struggling with bad weather conditions [

26].

We frequently noticed the presence of microplastics in the ventriculus of the stranded puffins during this event. This was considered an incidental finding not related to the cause of death; however, it emphasizes the high exposure of plastic for Atlantic marine species, as evidenced in other studies [

27,

28]. The consequences of chronic exposure to microplastics are still unknown, although absorption and translocation of ingested plastic particles have been experimentally demonstrated [

29].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we consider that the most likely cause of death in these animals was a combination of starvation and nephropathy. The severity of the lesions and the high incidence of parasitism indicate that Renicola sloanei can cause disease and contribute to mortality in the Atlantic puffin. However, starvation associated with a climatic event could be a major predisposing cause for the unusual mortality event of Atlantic puffins in the Canary Islands.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Summary of histopathological results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.S. and A.F.; methodology, C.S.S., A.C.R., L.C.H., C.R.H.; validation, R.P.V., J.M. and P.F.; formal analysis, C.S.S., O.Q.C., R.P.V., C.R.H., and L.C.H.; investigation, C.S.S., L.M.P.; resources, A.F., M.C.P., A.V.W.; data curation, A.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S.S., O.Q.C.; visualization, A.F.; supervision, A.F., M.C.P.; project administration, A.F.; funding acquisition, A.F., M.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been performed with the economic and logistical support from the “Dirección General de Lucha Contra el Cambio Climático y Medio Ambiente” under the creation of the Canarian Network for the Surveillance of the Wildlife Health: Red Vigía (Orden Nº134/2020 de 26 de mayo de 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to legal reasons and privacy regulation.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Beneharo Rodríguez and the team from the Canary Islands’ Ornithology and Natural History Group (GOHNIC), who dedicated great efforts to the study of the Canarian avifauna, as well as to the technicians and Ambiental Police officers that collaborated in the collection and shipping of the carcasses. Also, we would like to thank all the veterinarians involved in the care of wildlife in the Recovery Veterinary Hospitals, especially Pascual Calabuig and the veterinarians of La Tahonilla Recovery Center (Cabildo de Tenerife).

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BS |

Body Score |

| PCR |

Polimerase chain reaction |

| BLAST |

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

References

- Burnham, K.K.; Burnham, J.L.; Johnson, J.A. Morphological measurements of Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica naumanni) in High-Arctic Greenland. Polar Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker-Nilssen, T.; Jensen, J.K.; Harris, M.P. Fit is fat: winter body mass of Atlantic Puffins Fratercula arctica. Bird Study 2018, 65, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkhill, P. Measurements of Puffins as criteria of sex and age. Bird Study 1972, 19, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R.T.; Nilsen, E.B.; Anker-Nilssen, T. Long-term decline in egg size of Atlantic puffins Fratercula arctica is related to changes in forage fish stocks and climate conditions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 457, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, W.T.; Mavor, R.; Riddiford, N.J.; Harvey, P.V.; Riddington, R.; Shaw, D.N.; Reid, J.M. Decline in an Atlantic puffin population: evaluation of magnitude and mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, F.A. Clinical, gross, and histological findings in herring gulls and Atlantic puffins that ingested Prudhoe Bay crude oil. Vet. Pathol. 1986, 23, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.K.; Burnham, J.L.; Johnson, J.A.; Huffman, A. Migratory movements of Atlantic puffins Fratercula arctica naumanni from high Arctic Greenland. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.; Divine, L.M.; Renner, H.; Knowles, S.; Lefebvre, K.A.; Burgess, H.K.; Wright, C.; Parrish, J.K. Unusual mortality of Tufted puffins (Fratercula cirrhata) in the eastern Bering Sea. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, J.P.; Harris, M.P.; Turner, D.M. Mass mortality of puffins, linked to starvation. Vet. Rec. 2013, 173, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.M.R.N.; Lavorente, F.L.P.; Lorenzetti, E.; Meira-Filho, M.R.C.; Nóbrega, D.F.; Chryssafidis, A.L.; Oliveira, A.G.; Domit, C.; Bracarense, A.P.F.R.L. Molecular identification and histological aspects of Renicola sloanei (Digenea: Renicolidae) in Puffinus puffinus (Aves: Procellariiformes): a first record. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019, 28, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.A. Studies on the life-history and ecology of the trematode genus Renicola Cohn, 1904. In Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London; Blackwell Publishing Ltd: Oxford, UK, 1956; Vol. 126, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, W.C.O. Report, of the Society’s Prosector for the year 1953. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1954, 124, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.J.; Newnham, R.; Bailey, S.J.; Alexander, L.G. Evaluation of a fast, objective tool for assessing body condition of budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 98, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spackman, E.; Senne, D.A.; Myers, T.J.; Bulaga, L.L.; Garber, L.P.; Perdue, M.L.; Lohman, K.; Daum, L.T.; Suarez, D.L. Development of a real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for type A influenza virus and the avian H5 and H7 hemagglutinin subtypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2002, 40, 3256–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, O.; Kuris, A.M.; Torchin, M.E.; Hechinger, R.F.; Dunham, E.J.; Chiba, S. Molecular-genetic analyses reveal cryptic species of trematodes in the intertidal gastropod, Batillaria cumingi (Crosse). Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Vera, R.; Miquel, J.; Suárez-Santana, C.; Martín-Carrillo, N.; Abreu-Acosta, N.; Marrero-Ponce, L.; Fariña-Brito, A.; Rodríguez, B.; Fernández, A.; Foronda, P. Record of Renicola sloanei Wright, 1954 (Plagiorchiida: Renicolidae) in the Atlantic puffin Fratercula arctica (Linnaeus, 1758) arrived at the Canary Islands (Spain). J. Helminthol. 2024, 98, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneberg, P.; Sitko, J.; Bizos, J.; Horne, E.C. Central European parasitic flatworms of the family Renicolidae Dollfus, 1939 (Trematoda: Plagiorchiida): molecular and comparative morphological analysis rejects the synonymization of Renicola pinguis complex suggested by Odening. Parasitology 2016, 143, 1592–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.L.; Zhang, Y.; Jimenez, A.G. Skeletal muscle and metabolic flexibility in response to changing energy demands in wild birds. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 961392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerdy, H.; Baldassin, P.; Werneck, M.R.; Bianchi, M.; Ribeiro, R.B.; Carvalho, E.C.Q. First report of kidney lesions due to Renicola sp. (Digenea: Trematoda) in free-living Magellanic Penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus Forster, 1781) found on the coast of Brazil. J. Parasitol. 2016, 102, 650–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, J.; Anderson, K.; Wolf, K. Retrospective mortality review of tufted puffins (Fratercula cirrhata) at a single institution (1982–2017). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2022, 53, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, O.; Fernández, J.C.; Esch, G.W.; Seed, J.R. Parasitism: the diversity and ecology of animal parasites; Cambridge University press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2001; ISBN 0521662788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornet, S.; Bichet, C.; Larcombe, S.; Faivre, B.; Sorci, G. Impact of host nutritional status on infection dynamics and parasite virulence in a bird-malaria system. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014, 83, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, A. A Contribution to the Pathomorphology of Vitamin A Deficiency in Chickens. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. Reihe A 1972, 19, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wobeser, G.; Kost, W. Starvation, staphylococcosis and vitamin A deficiency among mallards overwintering in Saskatchewan. J. Wildl. Dis. 1991, 28, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurenson, K.; Wood, M.J.; Birkhead, T.R.; Priestley, M.D.; Sherley, R.B.; Fayet, A.L.; Votier, S.C. Long-term multi-species demographic studies reveal divergent negative impacts of winter storms on seabird survival. J. Anim. Ecol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmo, C.G.; Piersma, T.; Williams, T.D. A sport-physiological perspective on bird migration: evidence for flight-induced muscle damage. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 2683–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Lozano, R.; de Quirós, Y.B.; Díaz-Delgado, J.; García-Álvarez, N.; Sierra, E.; De la Fuente, J.; Arbelo, M. Retrospective study of foreign body-associated pathology in stranded cetaceans, Canary Islands (2000–2015). Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, J.F.; Bond, A.L.; Hedd, A.; Montevecchi, W.A.; Muzaffar, S.B.; Courchesne, S.J.; Mallory, M.L. Prevalence of marine debris in marine birds from the North Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 84, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sales-Ribeiro, C.; Brito-Casillas, Y.; Fernandez, A.; Caballero, M.J. An end to the controversy over the microscopic detection and effects of pristine microplastics in fish organs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).