Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

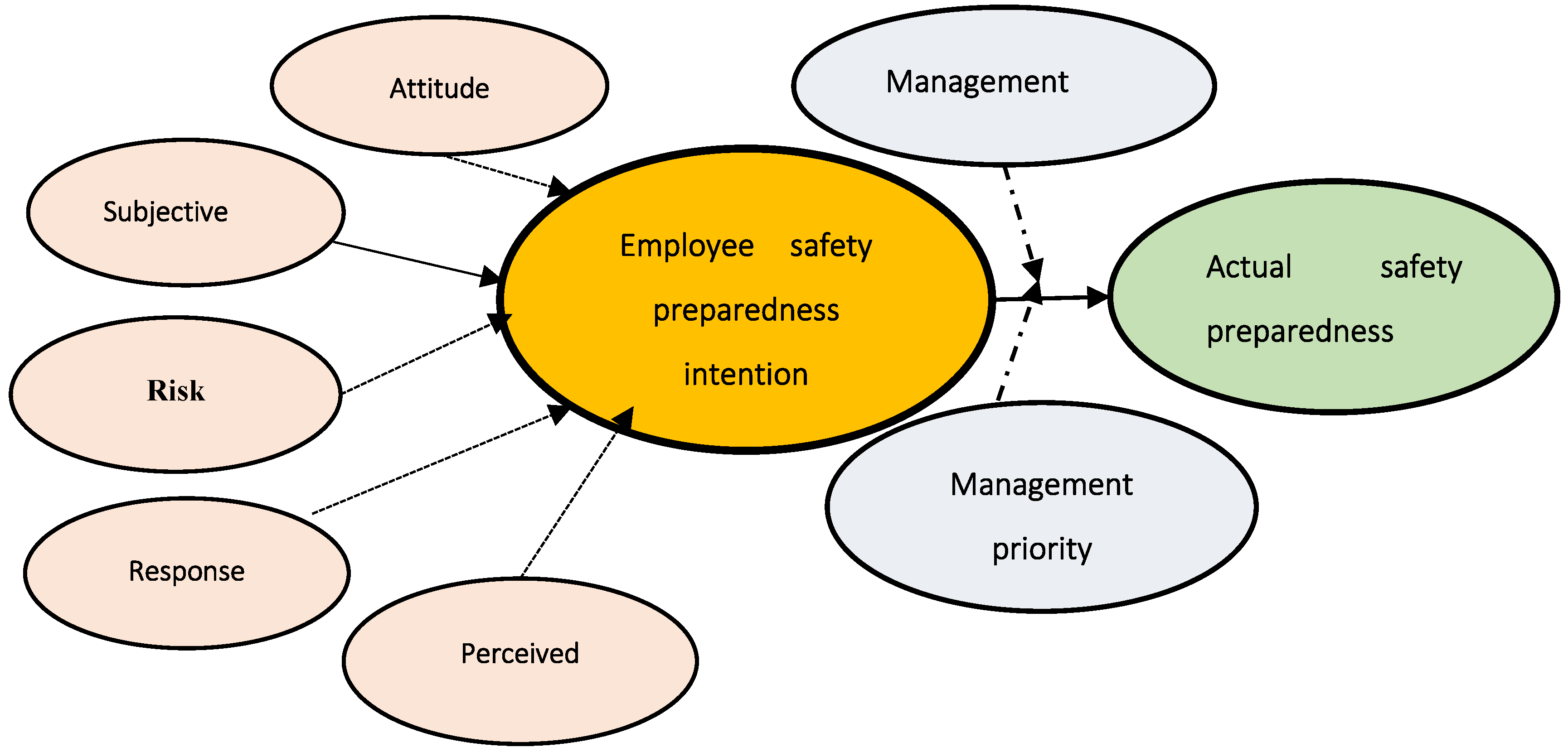

2. Psychosocial Constructs, Planned Behavior Theory (PBT) and Emergency Preparedness Intentions (EPI)

2.1. The Extended TPB Model

2.2. Attitudes and Emergency Preparedness Intentions

2.3. Subjective Norms and Emergency Preparedness Intentions

2.4. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) and Emergency Preparedness Intentions (EPI)

2.5. Mediating Role of Intention in Psychological Factors and Emergency Preparedness Behaviors

3. Research Methods

3.1. Sources and Description of Data

3.2. Analytical Framework

3.3. Ethical Concerns

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Testing the Measurement for Model Fit

5. Conclusion and Policy Implications

References

- Benson C, Dimopoulos CD, Argyropoulos CD, et al. Assessing the common occupational health hazards and their health risks among oil and gas workers. Safety Sci. 2021;140(1):105284. [CrossRef]

- Edokpolo B, Yu QJ, Connell D. Health risk assessment for exposure to benzene in petroleum refinery environments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;1:595-610. [CrossRef]

- Aliyund AA, Saidu S. Pattern of occupational hazards and provisions of occupational health services and safety among workers of Kaduna Refinery and Petrochemical Company Ltd (KRPC), Kaduna, Nigeria. Cont J Trop Med. 2011;5(1):1-5.

- Islam B. Petroleum sludge, its treatment and disposal: A review. Int J Chem Sci. 2015;13(4):1584-1602.

- Eyayo F. Evaluation of occupational health hazards among oil industry workers: A case study of refinery workers. IOSR J Environ Sci Toxicol Food Technol. 2014;8(12):22-53. [CrossRef]

- Overton EB, Adhikari PL, Radovic JR, et al. Fates of petroleum during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill: A chemistry perspective. Front Mar Sci. 2022;9:928576. [CrossRef]

- Adamu UW, Yeboah E, Sarfo I, et al. Assessment of oil spillage impact on vegetation in South-Western Niger Delta, Nigeria. J Geo Environ Earth Sci Int. 2021;25(9):31-45. [CrossRef]

- Acheampong T, Phimister E, Kemp A. What difference has the Cullen Report made? Empirical analysis of offshore safety regulations in the United Kingdom's oil and gas industry. Energy Policy. 2021;155:112354. [CrossRef]

- Purohit BK, Tewari KSNV, Prasad VK, et al. Marine oil spill clean-up: A review on technologies with recent trends and challenges. Reg Stud Mar Sci. 2024;80:103876. [CrossRef]

- Edmund et al. Emotional intelligence as a conduit for improved occupational health safety environment in the oil and gas sector. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Khan Y, O’Sullivan T, Brown A, et al. Public health emergency preparedness: a framework to promote resilience. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1344. [CrossRef]

- Hammond M, Owusu NO, Nunoo EK, et al. How quality of work-life influences employee job satisfaction in a gas processing plant in Ghana. Discov Sustain. 2023;4:10. [CrossRef]

- Wendelboe AM, Morrow R, Hsu J, et al. Tabletop exercise to prepare institutions of higher education for an outbreak of COVID-19. J Emerg Manag. 2020;18(2):183–184. [CrossRef]

- Mabuku M, Nkhata S, Phiri J, et al. Rural households’ preparedness and social determinants in Mwandi district of Zambia and Eastern Zambezi Region of Namibia. Int J Disaster Risk Reduc. 2018;28:284–297. [CrossRef]

- Herstein J, Kuehnert M, Kahn K, et al. Emergency preparedness: What is the future? Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2021;1(1):e29. [CrossRef]

- Keim M. Planning as a component of preparedness. In: Disaster Planning: A Practical Guide for Effective Health Outcomes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2021:17-24.

- Aminizadeh S, Ranjbar S, Majidi M, et al. Hospital management preparedness tools in biological events: A scoping review. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8(1):234. [CrossRef]

- Bazyar J, Gholami S, Mohammadi A, et al. The principles of triage in emergencies and disasters: A systematic review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2020;35(3):305–313. [CrossRef]

- Paton D. Disaster risk reduction: Psychological perspectives on preparedness. Aust J Psychol. 2019;71(4):327–341. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Occupational safety and health and skills in the oil and gas industry operating in polar and subarctic climate zones of the northern hemisphere: Report for discussion at the Tripartite Sectoral Meeting on Occupational Safety and Health and Skills in the Oil and Gas Industry Operating in Polar and Subarctic Climate Zones of the Northern Hemisphere. Geneva: International Labour Office, Sectoral Policies Department; 2016.

- Ejeta LT, Ardalan A, Paton D. Application of behavioural theories to disaster and emergency health preparedness: A systematic review. PLoS Curr. 2015;7. [CrossRef]

- Najafi A, Shahraki A, Shahraki M, et al. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and Disaster Preparedness. PLoS Curr. 2017;9. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta R, Yamaguchi K, Hoshino Y, et al. A rapid indicator-based assessment of foreign resident preparedness in Japan during Typhoon Hagibis. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;51:101849.

- Wang H, Wang L, Zhang S, et al. Study on the formation mechanism of medical and health organisation staff’s emergency preparedness behavioural intention: From the perspective of psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8246. [CrossRef]

- Wu G, Han Z, Xu W, Gong Y. Mapping individuals’ earthquake preparedness in China. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2018;18(5):1315–1325. [CrossRef]

- Han Z, Wang H, Du Q, Zeng Y. Natural hazards preparedness in Taiwan: A comparison between households with and without disabled members. Health Secur. 2017;15(6):575–581. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Tsai N. Factors affecting elementary and junior high school teachers’ behavioural intentions to school disaster preparedness based on the theory of planned behaviour. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;69:102757. [CrossRef]

- Yanquiling RS. Predictors of risk reduction behavior: Evidence in last-mile communities. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024;113:104875. [CrossRef]

- Gumasing MJ, Sobrevilla MD. Determining factors affecting the protective behaviour of Filipinos in urban areas for natural calamities using an integration of Protection Motivation Theory, Theory of Planned Behaviour, and Ergonomic Appraisal: A sustainable disaster preparedness approach. Sustainability. 2023;15(8):6427. [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh Z, Samah AA, Roslan S, Shaffril HAM, D’Silva JL, Kamarudin S, Ahrari S. Household preparedness for future earthquake disaster risk using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021;65:102533. [CrossRef]

- Vinnell LJ, Milfont TL, McClure J. Why do people prepare for natural hazards? Developing and testing a Theory of Planned Behaviour approach. Curr Res Ecol Soc Psychol. 2021;2:100011. [CrossRef]

- Kurata S, Otsuki K, Nakanishi H, et al. Factors affecting perceived effectiveness of Typhoon Vamco (Ulysses) flood disaster response among Filipinos in Luzon, Philippines: An integration of Protection Motivation Theory and Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;67:102670. [CrossRef]

- Kurata S, Otsuki K, Nakanishi H, et al. Determining factors affecting perceived effectiveness among Filipinos for fire prevention preparedness in the National Capital Region, Philippines: Integrating Protection Motivation Theory and extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023; 85:103497. [CrossRef]

- Ng SL. Effects of risk perception on disaster preparedness toward typhoons: An application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2022;13(1):100–113. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Zhao J, Wang Y, Hong Y. Study on the formation mechanism of medical and health organization staff’s emergency preparedness behavioral intention: From the perspective of psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8246. [CrossRef]

- Sin C, Rochelle T. Using the theory of planned behavior to explain hand hygiene among nurses in Hong Kong during COVID-19. J Hosp Infect. 2022; 123:119–125. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Qin B, Hu Z, Li H, Li X, He Y, Huang H. Predicting mask-wearing behaviour intention among international students during COVID-19 based on the theory of planned behavior. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(4):3633–3647. [CrossRef]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of Structural Equation Modelling. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2011.

- Tang JS, Feng JY. Residents’ disaster preparedness after the Meinong Taiwan earthquake: A test of Protection Motivation Theory. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1434. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(4):665–683. [CrossRef]

- Obaidellah U, Al Haek M, Cheng P. A survey on the usage of eye-tracking in computer programming. ACM Comput Surv. 2019;51:1-58. [CrossRef]

- Trifiletti E, Shamloo SE, Faccini M, Zaka A. Psychological predictors of protective behaviours during the Covid-19 pandemic: Theory of planned behavior and risk perception. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2021;32(3):382–397. [CrossRef]

- Xing H, Que T, Wu Y, et al. Public intention to participate in sustainable geohazard mitigation: An empirical study based on an extended theory of planned behavior. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2023;23(4):1529–1547. [CrossRef]

- Poe WA, Mokhatab S. Introduction to natural gas processing plants. In: Poe WA, Mokhatab S, eds. Modeling, Control, and Optimization of Natural Gas Processing Plants. Gulf Professional Publishing; 2017:1-72. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Cheng Z. Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. Chest. 2020;158(1):65-71.

- Alfons A, Ateş NY, Groenen PJF. A robust bootstrap test for mediation analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2022;25(3):591-617. [CrossRef]

- Johnson N. Elevating natural gas liquid (NGL) extraction and fractionation train performance: A systematic approach of simulation analysis, advanced modification, and vertical advancement. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;30(3):607–610. [CrossRef]

- Karimi S, Mohammadimehr S. Socio-psychological antecedents of pro-environmental intentions and behaviors among Iranian rural women: An integrative framework. Front Environ Sci. 2022;10:979728. [CrossRef]

- Jacob J, Valois P, Tessier M. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict the adoption of heat and flood adaptation behaviors by municipal authorities in the province of Quebec, Canada. Sustainability. 2021;13(5):2420. [CrossRef]

- McClure J, Ferrick M, Henrich L, Johnston D. Risk judgments and social norms: Do they relate to preparedness after the Kaikōura earthquakes? Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies. 2019;23(2):41-51.

- Mirzaei N, Dehdari T, Taghdisi MH, Zare N. Development of an instrument based on the theory of planned behavior variables to measure factors influencing Iranian adults' intention to quit waterpipe tobacco smoking. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2019;12:901-912. [CrossRef]

- Nunoo EK, Twum E, Panin A. A criteria and indicator prognosis for sustainable forest management assessments: Concepts and optional policy baskets for the high forest zone in Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Forestry. 2016;35(2):149-171. [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management. 2016;5(1):28-36. [CrossRef]

- Khan et al. The role of sense of place, risk perception, and level of disaster preparedness in disaster vulnerable mountainous areas of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2020; 27:44342-44354. [CrossRef]

- Thompson C, Kim R, Aloe A, Becker B. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2017;39:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Nusair K, Hua N. Comparative assessment of structural equation modelling and multiple regression research methodologies: E-commerce context. Tourism Management. 2010;31(3):314-324. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh D, Justin P. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021;173:121092.

- Best JW, Kahn JV. Research in Education. 10th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2006.

- Cai J, Hu S, Sun et al. Exploring the relationship between risk perception and public disaster mitigation behaviour in geological hazard emergency management: A research study in Wenchuan County. Disaster Prevention and Resilience. 2023. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Nunoo EK, Twum E, Panin A. Assessment of students’ behavioural risk to environmental hazards in academic institutions in Ghana. J Environ Res. 2018;2(2):4-16.

- Nunoo EK, Panin A, Essien B. Environmental health risk assessment of asbestos containing materials in the brewing industry. J Environ Res. 2018;2(2):3-14.

- Budhathoki NK, Paton D, Lassa JA, Bhatta GD, Zander KK. Heat, cold, and floods: exploring farmers' motivations to adapt to extreme weather events in the Terai region of Nepal. Nat Hazards Rev. 2020;103(3):3213-3237. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Cong Z. Response efficacy perception and taking action to prepare for disasters with different lead time. Nat Hazards Rev. 2022;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179-211. [CrossRef]

- Ejeta LT, Ardalan A, Paton D. Application of Behavioral Theories to Disaster and Emergency Health Preparedness: A Systematic Review. PLOS Curr Disasters. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Yeboah E, Sarfo I, Nunoo EK, et al. GIS-based emergency fire response for minimization of fire outbreaks in the Greater Accra Metropolis, Ghana. J Geogr Environ Earth Sci Int. 2021;25(5):30-45. [CrossRef]

| Description | Frequency (f) | Percent(%) | |

| Gender | Male | 129 | 75.9 |

| Female | 41 | 24.1 | |

| Age | 20-29 | 81 | 47.6 |

| 40-49 | 14 | 8.2 | |

| 50-59 | 11 | 6.5 | |

| 60-69 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Highest level of Education | Undergraduate Degree | 54 | 31.8 |

| Postgraduate Degree | 116 | 68.2 | |

| Number of Years Worked | Less than a year | 8 | 4.7 |

| 1-5 years | 27 | 15.9 | |

| 5-10 years | 107 | 62.9 | |

| 10-15 years | 19 | 11.2 | |

| 15-20 years | 9 | 5.3 |

| Measures for model fit | Index |

| Chi-square Fit Test | 1.33 |

| RMSEA | 0.04 |

| SUMMER | 0.03 |

| CFI | 0.97 |

| IF | 0.94 |

| NFI | 0.97 |

| TLI | 0.90 |

| Path Description | β | SE | T | P-Value | CI |

| ATT → EPI | 0.36 | 0.05 | 7.18 | < 0.001*** | 0.30, 0.40 |

| SN → EPI | 0.31 | 0.06 | 5.17 | < 0.001*** | 0.25, 0.42 |

| PBC → EPI | 0.27 | 0.04 | 6.72 | < 0.001*** | 0.21, 0.35 |

| RP → EPI | 0.22 | 0.03 | 7.29 | <0.001*** | 0.09, 0.25 |

| RE → EPI | 0.12 | 0.02 | 6.15 | <0.001*** | 0.06, 0.14 |

| Path Description | Β | SE | T | P-Value | CI |

| ATT→ APB (Direct Effect) | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.25 | 0.15 | |

| ATT → EPI → APB (Indirect Effect) | 0.29 | 0.06 | 4.83 | <0.001*** | 0.25, 0.35 |

| SN → APB (Direct Effect) | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.30 | 0.10 | |

| SN→ EPI → APB (Indirect Effect) | 0.16 | 0.06 | 2.60 | 0.005 | 0.10, 0.20 |

| PBC → APB (Direct Effect) | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.85 | 0.20 | |

| PBC → EPI → APB (Indirect Effect) | 0.18 | 0.09 | 1.98 | 0.025 | 0.15, 0.24 |

| RP → APB (Direct Effect) | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.28 | 0.10 | |

| RP → EPI → APB (Indirect Effect) | 0.10 | 0.002 | 5.00 | <0.001*** | 0.05, 0.15 |

| RE → APB (Direct Effect) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.25 | |

| RE → EPI → APB (Indirect Effect) | 0.22 | 0.03 | 7.33 | <0.001*** | 0.20, 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).