1. Introduction

In modern business, one of the most important objects is human resources. Motivated and skilled individuals working in a team are able to create the right atmosphere for the success of the company. Human resources are one of the main elements of success in achieving the set goals in difficult conditions [

1]. However, it is important to distinguish not only competent and qualified personnel but also the appropriate method of their management [

2]. Choosing the right human resources management model for the company's activities can determine its overall competitiveness in the market [

3]. It is for this reason that company managers and owners must understand the importance of human capital. It should be emphasized that it is important not only to choose the most appropriate human resources management method but also to periodically review it: conduct quality research involving personnel and conduct employee satisfaction surveys, provide an opportunity to express opinions or comments, and, if necessary, be able to change the human resources management method [

4]. Some of them failed, while others managed to optimize their activities and continue them with minimal losses [

5,

6]. Like politicians, human resource managers had to make important decisions without fully knowing and completely understanding the uncertainty of the disease progression and the critical nature of the disease. The answers to the main problems often fluctuated between critical healthcare needs and the need to conduct business in other areas without regard to quality [

7]. During the war in Ukraine, companies operating in the Eastern countries were forced to respond quickly to the situation and reorient themselves to the markets of other countries. Both the disease and the war caused extreme chaos in the world and society—people were forced to learn to live anew according to the new established order [

8]. In an emergency, business often experiences chaos. In order to reduce confusion, it is appropriate to follow pre-established guidelines. The events of recent years—the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine—highlighted the need to optimize human resource management in the logistics sector [

9].

The focus of the research is on human resource management within the logistics sec-tor. The objective of the research is to develop a model for human resource management within the logistics sector during an emergency situation [

10]. The purpose of this paper is to carry out an investigation of the elements of human resource management in relation to emergency scenarios. The purpose of this paper is to carry out research and determine the fundamentals of human resource management in the logistics industry. A model of hu-man resource management in the logistics industry during an emergency situation is go-ing to be presented as the goal of this paper.

First of all, the paper stands out in its setting—human resource management in ex-treme conditions, research of the Lithuanian logistics industry. While most research on the sustainability of human resource management are either theoretical or worldwide, this paper investigates a particular economic sector that has been especially impacted by the COVID-19 epidemic and geopolitical events including the crisis in Ukraine. This makes the study unusual since past studies have typically not included the logistics sector, which is one of the most sensitive sectors during supply chain disturbances.

First of all, the work distinguishes itself in its context—research of the Lithuanian logistics sector, human resource management in ex-treme conditions. Although most studies on the sustainability of human resource management are either theoretical or global, this paper examines a specific economic sector that has been particularly affected by the COVID-19 outbreak and geopolitics including the conflict in Ukraine. This makes the research unique since earlier studies have usually not included the logistics sector, one of the most sensitive industry during supply chain disturbances.

Second, the paper looks at the reciprocal interaction between employee well-being and organizational sustainability, therefore contributing significantly to the theory of human resource management. While many past studies have solely looked at how HRM policies impact employees, this study reveals that long-term viability of a company can depend on employee well-being. This offers fresh ideas on how HRM may not only help to manage crises but also help a company to be long-term stable.

Third, the research is distinguished by a creative approach to methodology. While most HRM research employ surveys and case studies, this paper applies quantitative and qualitative analysis techniques like sentiment analysis, clustering, network analysis, and the AHP method. This mix helps us to see not only employee senti-ment but also useful markers of sustainability and work-life balance, therefore giving us a more complete awareness of the success of HRM efforts.

The study underlined the importance of work organization models for sustainability, a field not very investigated in past studies. The findings revealed that companies that embraced digital technologies, more flexible working schedules, and a hybrid model during the crisis kept better degrees of employee well-being and sustainability. This realization can be rather helpful in guiding next human resource management plans.

Finally, the paper provides useful advice and strategic suggestions that busi-nesses might start right away. This sets it apart from merely theoretical studies since it offers businesses data-based ideas on how to more successfully handle staff amid crises. For instance, a crisis reduces the psychological well-being of employees and indicators of organizational sustainability; hence, a better work-life balance greatly boosts organizational sustainability while a drop in productivity has a negative effect on sustainability indicators.

This research study offers a lot to the field of sustainable human resource management since it looks at a particular industry, applies sophisticated data analysis approaches, discovers a two-way link between employee well-being and the sustainability of a company, and provides companies with practical advice. These reasons make it topical, creative, and quite practically important.

2. Literature review

In a modern, dynamic society, it is vital to be able to bring employees together for a common goal. One of the most important secrets of the success of organizations is a united team, whose employees realize their best qualities. A person's beliefs, values, and priorities guide them in life [

11]. It is these aspects of life that give each person exclusivity and uniqueness. A person is a social being who develops through science [

12]. Different abilities, knowledge, skills, and experiences allow a person to become a specialist in one or another field. According to Sinek [

13], if “we do not understand people, we do not understand business,” then in principle it can be said that human resources are one of the main factors in the successful development of countries and regions [

14]. Human resources give impetus to production resources, determine their use, and influence the final result [

15]. According to scientific sources, there is no single definition of human resources, so there is no point in looking for one [

16]. However, in order to clarify the change in the concept of human resources, it is appropriate to analyze its development, which covers the years 1954 - 2024. The scientific literature extensively studied the concept of human resources during this period [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In order to better understand the change in the concept of the analyzed concept, the change in terms can be represented in a timeline (see

Figure 1).

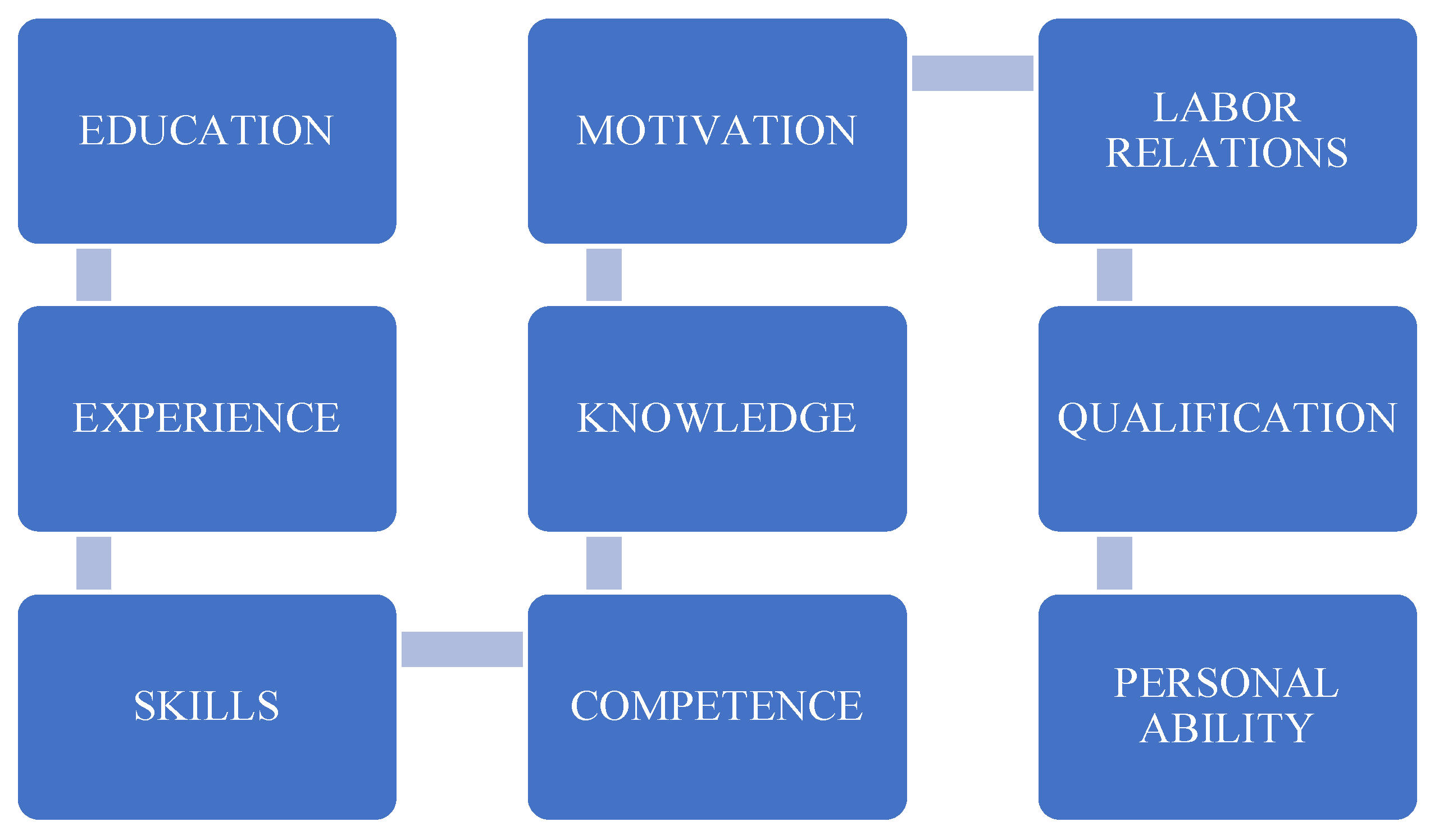

It is appropriate to define the criteria for both future and current employees when analyzing the concept of human resources. The components of human resources described by authors Gižienė and Rečelienė [

23] essentially ensure the stability of the company (see

Figure 2).

Taking into account the components depicted in

Figure 2, we can distinguish the following essential aspects that directly impact the company's sustainability:

1. One of the most important components of human resources is

education [

24]. It provides people with the opportunity to adapt to the constantly changing labor market, innovations, and societal needs. Education promotes critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity, which are essential values and practical skills. Education also shapes culture and values, contributes to community development, and promotes human resource development in society.

2.

Experience is an important part of human resources because it enriches people's abilities and thinking [

25]. This not only helps someone to grow from prior mistakes or achievements but also provides a distinctive way of handling problems. Experience builds a good attitude toward demanding circumstances, helps one overcome obstacles, and facilitates simpler adaption and decision-making. Successful communication and teamwork at the corporate or social level depend on social skills and mutual understanding, which shared life events help to develop.

3. Having a variety of

skills, people become competitive in the labor market and contribute to innovation and economic growth [

26]. The abundance and diversity of skills allow people to realize their potential and effectively adapt to changing circumstances.

4.

Competence is a key element of human resources, indicating the ability to effectively perform work or implement tasks [

27]. Competent people not only work more efficiently but also significantly contribute to the innovation and growth of the organization. Competences also create high-quality work and promote cooperation, which is necessary for success and progress.

5.

Knowledge is an indispensable component of human resources, as it acts as a foundation for personal and collective growth and progress [

28]. The accumulated academic and life knowledge allows people to create, understand the environment, learn from it, and adapt more easily. Accumulated knowledge shapes the uniqueness of an individual and becomes the engine of cultural, educational, and technological development.

6.

Motivation is an essential component of human resource management. Motivational measures help create a favorable work environment in which people feel valued and committed to a common vision [

29]. In addition, motivation promotes personal development and the desire to deepen knowledge, abilities, or existing skills, which eventually become the basis for not only individual but also collective success.

7.

Labor relations are essentially form the basis for productivity and the general well-being of employees [

30].

8. Human resources depend much on

qualification since it reflects all necessary human abilities, knowledge, and skills as well as character qualities or values required for efficient employment [

31]. Whether personally or group, qualified employees not only help the business to be successful but also encourage its general expansion.

Basically, an employee's creative, communicative, leadership, critical thinking, experience, and problem-solving capacity defines their skills and

personal ability [

32].

All things considered, human resources in the scientific literature for the years 1954–24 are characterized as particular talents, qualifications, and competency of staff [

33,

34,

35,

36]. The company gains a competitive edge in the market and guarantees a success factor by the intended application and appropriate coordination of these components. Applying human resource management techniques in the activities of the business will assist to define the policies for appropriate work and operation and thus implement this. Periodically reviewing these rules and using others or developing new models helps to guarantee the high-quality implementation and result of the management model so that the business may fully realize its possibilities.

In order to define what an emergency situation is, it would be appropriate to analyze its concept. The concept is quite strict and does not have room for interpretation; therefore, it is possible to review the definition of an emergency situation in different sources:

“An emergency situation is a situation that arises due to natural, technical, ecological, or social reasons or military actions and causes a sudden and serious danger to people’s lives or health, property, or nature or causes death, injury, or property damage” [

37].

"What is an extreme event? It's an event that is natural, technical, ecological, or social, and it meets or goes beyond the established criteria. It puts people, their property, the economy, and the environment at risk" [

38]. The international term “force majeure” could also be attributed to a synonym for an emergency situation, which is usually used when talking about agreements, contracts, or other written obligations. "An unexpected event (e.g., war, crime, earthquake, etc.) known as "force majeure" prevents someone from carrying out an agreed-upon action" [

39].

The origin of emergency situations can be due to:

• internal risk factors: radiation, chemical, biological, transport accidents, natural disasters, influxes of illegal migrants, terrorist acts;

• external risk factors: threat of war, economic and social instability in neighboring countries, etc.

All of these listed factors can have a negative impact on: general public health, the risk of individual and mass health disorders, human deaths, and diseases. Lithuania is developing a special crisis management system to handle emergencies and other special situations [

40]. Human resources are a key element of any organization. Some of the many functions performed by human resources management specialists are recruitment and training, assistance in improving qualifications, and a system of employee evaluation and recognition in financial or other forms [

41]. Although this is not an exhaustive list of duties, these are some of the most important and basic responsibilities. Due to the dynamic development of human resources in any institution and its complexity, companies must be able to adapt to constantly changing environmental conditions and circumstances [

42]. The COVID-19 pandemic has re-examined the most important attitudes and qualifications of companies, which has led to significant challenges for human resources. In addition to the uncertainty of jobs, business continuity, and financial concerns, several key stressors may have affected the mental health of employees during and after the COVID-19 pandemic:

1) perception of their own safety, threat, and risk of infection;

2) stressful information overload and uncertainty;

3) quarantine and isolation;

4) social exclusion [

43].

“In every crisis lies a great opportunity” [

44] —this phrase perfectly reflects the impact of extreme situations on companies and their human capital. The crisis creates an opportunity for a strategically focused and strong leader to solve the challenge in such a way that it becomes a competitive advantage for the company [

45,

46]. The strongest and most surviving organizations were those that were able to respond effectively and quickly to the emergency situation. Successful employers are not only well versed in recruitment, retention, and profit generation methods, but also respond appropriately to the psychological health of employees. This problem is most appropriate to apply to the COVID-19 pandemic [

47,

48,

49], but specifically looking at the logistics and transport sector—similar problems have affected transport managers and forwarders working closely or specifically with the Eastern market in relation to the war in Ukraine [

50,

51]. This type of emergency situation not only exposes employees to existential issues, but also puts them on the brink of burnout. Employees constantly feel stress due to the unknown, uncertainties arising from the future, the workplace, and the general fate of the company. According to studies by authors Paycor Yu et al. [

52], stress causes two-thirds of respondents to struggle with focusing on tasks or outcomes during emergencies. Improperly managed stress can cause various physical problems, exacerbate mental health problems, and lead to depression and other mental health disorders. This affects individual work performance, which in the long term negatively affects the performance and productivity of the company [

52]. The events of recent years—the COVID-19 global pandemic and the war in Ukraine—have revealed the true importance of logistics during an emergency. Logistics plays a crucial role in such crises: vehicles transport medicines, essential food products, humanitarian aid, or ammunition. According to the authors, the importance of decisions made in the logistics sector at each stage of emergency or disaster management needs to be emphasized [

53]. Logistics processes are thought of as a planned series of events and actions that involve different types of flow and their interactions [

54,

55]. The goal of these processes is to move and store tangible and intangible resources, such as goods, process participants, transactions, and information related to those resources [

56]. The flow of physical objects and information about them can be thought of as a system of interconnected operations called logistics processes [

57]. Powers [

58] distinguishes the structural analysis of logistics processes as follows:

2) Order acceptance [

60];

3) Customer service policy [

61];

4) Product production and processing [

62];

5) Inventory management [

63];

6) Optimal use of transport warehouses [

64];

7) Cargo processing [

65];

8) Management of non-standard cases [

66].

Summarizing the structural analysis of logistics processes, it can be stated that all the listed processes, together as a whole and separately, are very important and cannot function without each other [

67]. Properly planned tasks, thoughtful decisions, and choices create a harmonious logistics process that does not cause problems. Therefore, we can assert that logistics plays a crucial role in economic development, growth, and market integration. This has a significant impact on the economic performance of various industries.

Unlike before, today the importance of logistics and the need for its creation and development at the global, regional, and local levels are becoming increasingly important. When it comes to logistics development, most people think about logistics and transport infrastructure, creating an economic environment and facilitating the unhindered flow of goods, people, and capital.

However, an ever-growing problem is the workforce, logistics competencies, and skills. This is a labor-intensive activity, and despite the high level of technological development, mechanization, automation, and robotization of processes, the main resources are personnel and labor.

Due to its dynamism and necessity, the logistics sector is one of the most affected in emergency situations. While working, employees worry about whether their jobs will be saved or if the company will survive the crisis.

For people with psychological illnesses, prone to depression, and with various types of commitments, such extreme situations can cause serious health problems. The most notable events in the world today make us think and look for ways to prevent the depletion of human resources—to define a model for performing work and tasks that would ensure continuity of work, allow employees to feel safe and productive, and have a proper balance between life and work.

3. Materials and Methods

The studies include:

- 1.

Methodology for calculating the Average Sustainability Score.

The Average Sustainability Score is a key metric that allows you to assess the level of sustainability of an organization based on the results of several different factors [

68]. This score is usually used to analyze the overall sustainability status of an organization and compare it with other organizations or established standards. Below is a detailed methodology for calculating the average sustainability score [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]:

Data collection. One must gather data from several sustainability angles in order to get the average sustainability score. One can gather this material with: 1) Employee answers on environmental projects, well-being programs, stress levels, working conditions. 2) Objective data from the organization on energy consumption, waste reduction policies, recycling initiatives or social programs. 3) Expert insights on the organization’s strategies in the field of sustainability. 4) Each dimension provides a separate score, which is included in the final calculation.

-

Scoring of Sustainability Dimensions. Each sustainability dimension is assessed against pre-defined indicators or questions that are rated on a scale (e.g., 1 to 5 or 1 to 10):

1) Environmental Sustainability: Measures indicators such as energy conservation programs, recycling practices, and CO₂ emission reduction plans.

2) Social Sustainability: Measures employee diversity, gender equality, and community involvement.

3) Economic Sustainability: Measures the organization’s investment in sustainability or the proportion of profits allocated to social initiatives. 4) Employee Well-being: Measures employees’ stress levels, work-life balance.

The average score for each dimension is calculated using the following formula:

Where: n-amount of scores in dimention, Score

i – evaluation of separate parameters

Estimating the general average sustainability score. The final average sustainability score is computed as the average of all the aspects once the average score for every one of them has been computed. The aggregated outcome is found with the following formula:

Where: m- amount of dimentions; Dimention scorej - average score for each dimension

Standardizing environmental ratings. Sometimes dimensions might have several connotations or be expressed on several scales. Indicators or dimension scores are therefore normalized to guarantee that they have equal weight in the whole computation. Normalcy is carried out using the formula:

Finding an average sustainability score helps you to see overall the degree of sustainability of the company and points up areas of strength and weakness. This approach not only facilitates the comparison of several companies but also helps to establish objectives for next projects aimed at sustainability.

- 2.

Methodology for calculating Feature Importance in Random Forests.

Feature Importance is a machine learning Random Forest model result that shows how strongly a certain model variable (feature) contributes to the prediction accuracy. This method allows you to identify the most important features that most affect the model's decisions. Here's a detailed technique to computing the relevance of Random Forests model features [

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]:

Overview of the Random Forests Model. Random Forests is an ensemble learning method in which a large number of decision trees' predictions are pooled to improve accuracy. In this model, the importance of features is calculated according to their contribution to: Classification accuracy (in classification tasks), or Error reduction (in regression tasks). 2) Key features of Random Forests: Each tree is trained with a randomly selected set of data and features (bootstrap sampling and feature subset selection); The predictions of all trees are combined by the model through voting (for classification) or averaging (for regression).

-

Determining the Significance of a Feature: 1) The significance of features is typically determined in two primary methods in a random forest model: Based on the mean decrease in impurity (MDI) of the nodes; Employing the permutation method (Mean Decrease in Accuracy, MDA); 2) Enhancement of node purity (MDI). The fundamental principle of the significance of features in the random forest model is to evaluate the extent to which a specific feature enhances the purity of the model nodes (impurity). The integrity of nodes is a measure of the effectiveness of the decision tree in separating data into the corresponding classes or predictions. Calculation of MDI involves the following steps: a) Purity measurement: The nodes are divided into two categories by the feature employed in each tree. It is crucial to evaluate the extent to which this feature mitigates imprecision in the nodes, such as by employing the Gini index or entropy. b) Gini index or entropy are employed as purity metrics in classification. c) Variance is employed as a purity metric in regression.

d) Node influence: Calculates how much each feature contributed to the decrease in purity of all nodes across all trees.

e) Normalization: All importance contributions are normalized so that their sum is 1 (or 100%).

Basic MDI formula:

Where: T – number of decision trees; S

i - set of nodes in tree t; ΔI(s,j) – purity improvement when feature j is used at node s.

MDA, the permutation method. MDA ranks the relevance of features according to how their absence (or random rearranging) influences model accuracy. MDA computation steps: 1) Initially, the model's accuracy is computed considering all the features. 2) Random permutation of a single feature's values over the whole dataset retrain the model. This models the scenario whereby a feature gets eliminated. 3) Determines how the removal of a certain feature lowers the model's accuracy change. 4) Normalizing the significance values of features helps one to compare their respective influence on the model performance.

Understanding Feature Valuation. One can show feature importance either as a percentage or as a scale from 0 to 1. A feature's influence on the prediction of the model increases with its larger significance value. Usually just the top ten features show on graphs since less significant features have little or no impact.

Using feature relevance. Feature importance analysis serves to:

List the most crucial elements; companies should concentrate on the main elements influencing results. Simplify the model by eliminating low-important features, hence lowering the complexity without appreciable loss of accuracy. Make wise decisions: The findings reveal which elements are most important and can be applied to design doable activities.

-

Significance and restrictions of the approach. Significancy: 1) Reveal whatever aspects most help the model to be accurate. 2) Model interpretation clarifies how the model decides on issues of relevance for consumers and businesses.

Limitations: 1) Data dependency: Important calculations may be biassed if significant features are lacking or linked in the data. 2) Random forest models occasionally ignore the way that features interact with one another.

- 3.

-

Methodology for Calculating Predicted and Actual Sustainability Scores.

Comparing predicted and actual sustainability scores is an essential part of the analysis to assess the model’s ability to accurately predict phenomena. This methodology includes several key steps, from data collection and model training to generating forecasts and assessing their accuracy. Each step provides important information about the model’s performance and helps identify opportunities for improvement: 1)

Data collection and preparationIn the first stage, two types of data need to be collected: a) Actual sustainability scores: These are real data obtained from questionnaires, expert assessments or other reliable sources. These scores reflect the actual sustainability indicators of organizations. b) Predicted sustainability scores: These are data generated by a model that has been trained using a training set. These scores are based on input variables such as working conditions, stress levels or organizational initiatives. All data has to be standardized and provided in the same style if we are to guarantee flawless computation and analysis. 2)

Model training. However, in order to obtain projected scores, the model must first be trained using historical data. This encompasses the activities that come after it: a) The categorization of data: The original data is comprised of two sets: a training set, which typically accounts for eighty percent of the entire data, and a testing set, which accounts for twenty percent of the data. The only data that the model uses to learn is the training data. b) To further the field of machine learning, two models, including random forest regression, have been chosen for further development. The model's learning is limited to the data used for training. c) Two models, one of which is random forest regression, are selected in order to expand the capabilities of machine learning. In order to gain an understanding of the connections that exist between sustainability scores and input variables (such as stresses and workload), this model would be taught. d) Machine learning is advanced with the use of two models—random forest regression and another. The goal of training this model is to help it understand the factors (such as workload and stresses) that contribute to sustainability scores. e

) The model is evaluated for its ability to predict real values using a test set after training. 3)

Predictions regarding performance. The model is trained and subsequently applied to the test data set to generate predictions. Using the provided data, the model can forecast a sustainability score. For instance, the model can predict a low sustainability score if the input data indicates that employees are highly stressed and have a poor work-life balance. 4)

Calculation of residuals. The residuals are calculated by subtracting the model's projected values from the actual sustainability scores. The following formula explains this calculation:

Negative residuals show instances in which the model overstated the real value.

Positive residuals show situations in which the model understated the real value.

Values equal zero mean the model faithfully matched the real result.

5)

Assessing Model Accuracy. Multiple important criteria help one evaluate the accuracy of the predictions of a model: a) Mean Absolute Error (MAE):

This statistic finds the predictions' average error:

The R

2 coefficient indicates the degree of model explanation for the variance in the real data:

6) Result visualization. The outcomes are shown on a graph with the vertical axis representing the expected scores and the horizontal axis showing the actual scores—also known as actual scores. The red dotted line indicates a perfect match of the predictions to the actual values: a) Points on the line indicate exactly predicted values. b) Deviating points indicate prediction errors.

This methodology is important not only to assess the accuracy of the model’s performance, but also to identify opportunities for improvement. For example, residual analysis can assist in identifying certain conditions in which the model is most likely to make errors. In addition, model accuracy measurements such as MAE or RMSE provide clear signs for evaluating the model's effectiveness and comparing it to other methods.

This methodology also allows you to visually comprehend the model's predictive properties through graphs that compare real and predicted scores. Such analysis gives useful insights for organizations who want to better understand the structure of their data and make informed decisions based on model results.

- 4.

Qualitative, expert research is conducted by means of in-depth interviews.

An expert is a person, a specialist in a specific field, who has studied in a specific scientific or technological field, has accumulated valuable experience, and is competent to express an opinion in a specific field [

79]. Expert research is a special way to gather information in which the professional, practical, theoretical, technological, and other kinds of knowledge of experts are used to look into a certain subject [

80]. The expert assessment method is a specific type of survey of a specially selected group of people who know a certain field [

81]. An in-depth interview is a method of communication between the researcher and the respondent that creates a mutual connection in order to clarify the topic's problem without limiting the time or scope of the respondent's response [

82]. The goal of an in-depth interview is to clarify the answers to the questions of interest so the respondent cannot predict the research direction [

83]. In order for interview questions to help achieve the research goal, it is important to assess several aspects: 1) Clearly formulate the topic and what the interview is aimed at; 2) Are the questions not too complex, clear, and do not raise additional questions for the respondents?

3. Results

3.1. Applying sustainable human resource management models during emergencies

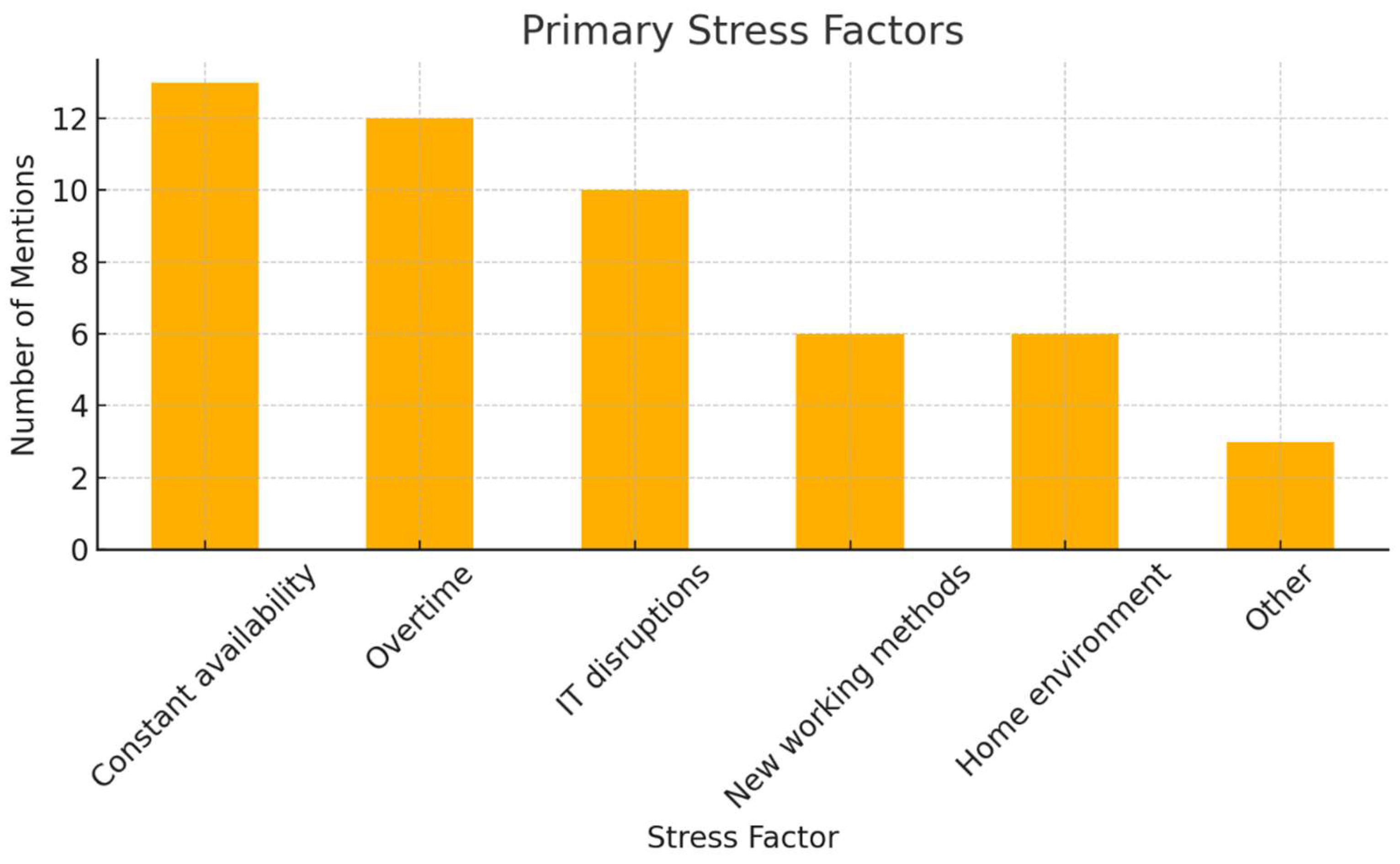

The study identified the most common sources of stress for employees in the work environment during extreme situations (see

Figure 4).

The data presented in it reflects the most important aspects that affect employee well-being and work efficiency, and allows for a deeper look at the problems encountered in the logistics sector. The most frequently mentioned source of stress is constant availability, which has collected as many as 12 mentions. This result reveals that the expectation of employees by employers or colleagues to be always available is a significant problem for employees. Apart from preventing employees from leaving their jobs, perpetual availability generates continuous psychological pressure. Employees cannot adequately relax, which might finally cause burnout, tiredness and workplace discontent. When the balance between work and personal life is not given enough priority, such a phenomena reveals the flaws in the work culture of corporations. Working overtime, which is mentioned 12 times, is another major source of worry. Events like the COVID-19 pandemic or the conflict in Ukraine often require companies to respond quickly, increasing their workload. Working longer hours, not getting enough sleep, and overworking employees can hurt their health and reduce their productivity. This becomes not only an individual problem, but also a challenge for the continuity of the company's activities. The third most important category is IT disruptions, mentioned 10 times. Technological problems, such as internet connection problems, lack of suitable technologies or software instability, cause additional stress, especially for employees working remotely. Disruptions like these can delay regular work processes, put employees on the spot, and make them feel more responsible because they have to figure out how to fix technical issues on their own without much help. The difficulties of hybrid or remote work were highlighted by the 8 mentions each of new working methods and the home environment. Employees often feel pressured to quickly master new work systems and processes, which increases psychological stress. In addition, working from home brings with it a variety of distractions: noise, lack of space, household chores and other household factors. These aspects reduce employee productivity, hinder concentration and can lead to dissatisfaction with working conditions. Finally, the category Other, which was mentioned 4 times, reflects specific or unique challenges faced by employees, perhaps related to personal problems or less common aspects of work organization.

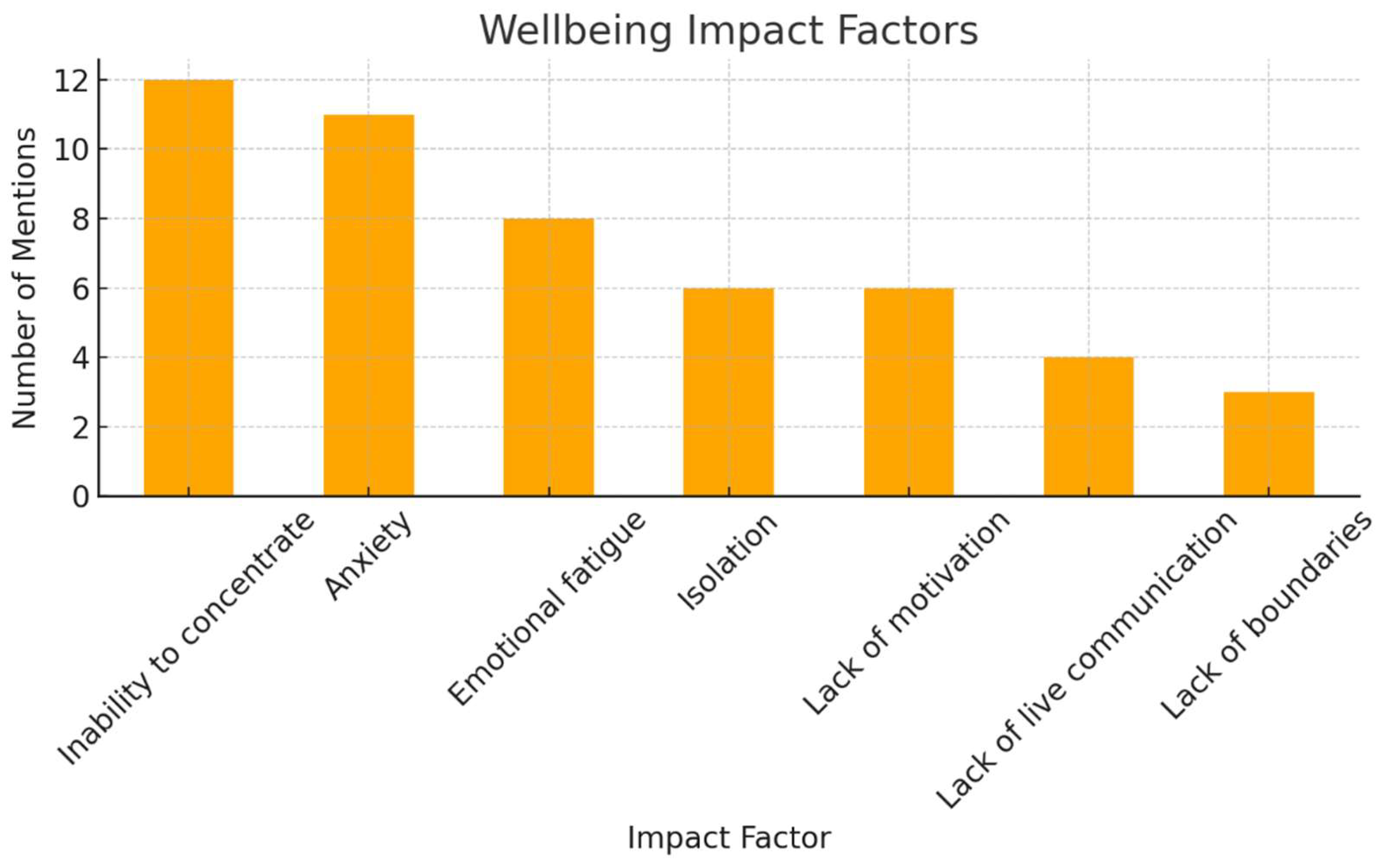

Figure 5 presents the main stress and emotional strain factors that employees face during emergencies.

These results provide insight into both psychological and social challenges that affect employee efficiency, motivation and overall well-being. The most frequently mentioned factor is Inability to concentrate, which was mentioned by as many as 12 respondents. This shows that a large proportion of employees experience difficulties maintaining attention to work tasks. Such a situation may be related to disruptions in the work environment, information overload or emotional pressure. Lack of concentration directly reduces work productivity and makes it difficult to complete tasks on time, especially when working remotely. Anxiety, cited eleven times, comes second most importantly. Job instability, more responsibility, or future anxiety might cause employees to feel more psychologically pressured. As an emotional state, anxiety can cause employees to lack motivation, suffer with emotional well-being, and finally contribute to burnout. Emotional fatigue, mentioned 10 times, emphasizes the consequences of long-term stress and tension for employees. Emotional exhaustion occurs due to excessive psychological load, when employees feel the pressure of not only work, but also personal life challenges. In the long run, this state can cause employees to become indifferent to the work they do and the goals of the organization. Social aspects also occupy a significant place, and one of them is Isolation, mentioned 8 times. Working remotely reduces social communication, which not only strengthens the feeling of loneliness, but also complicates team processes and the general emotional stability of employees. In addition, the lack of live communication, mentioned 6 times, further deepens this problem, because employees feel isolated from colleagues and the general activities of the company. Another important factor is Lack of motivation, mentioned 8 times. This highlights that long-term stress and uncertainty about working conditions or the stability of the company significantly reduce employee engagement and the desire to achieve results. Finally, cited five times, the absence of limits between work and personal life indicates that people who work remotely find it challenging to divide their personal and professional life. This emphasizes especially the need of proper work culture and work structure.

The results in

Figure 5 emphasize that the greatest challenges to employee well-being are psychological and social pressures; their impact is especially relevant in demanding conditions. Increasing workloads, adjusting working methods, and uncertainty about the future help to induce anxiety and emotional exhaustion. Meanwhile, social aspects such as isolation and lack of live communication emphasize the need to maintain strong social ties in the work environment, even when working remotely. Inability to concentrate and lack of motivation further worsen the situation, as these factors not only reduce employees’ productivity, but also have a long-term impact on their emotional state. This situation emphasizes that companies must take active measures to ensure well-being, paying particular attention to psychological support and improving work organization methods.

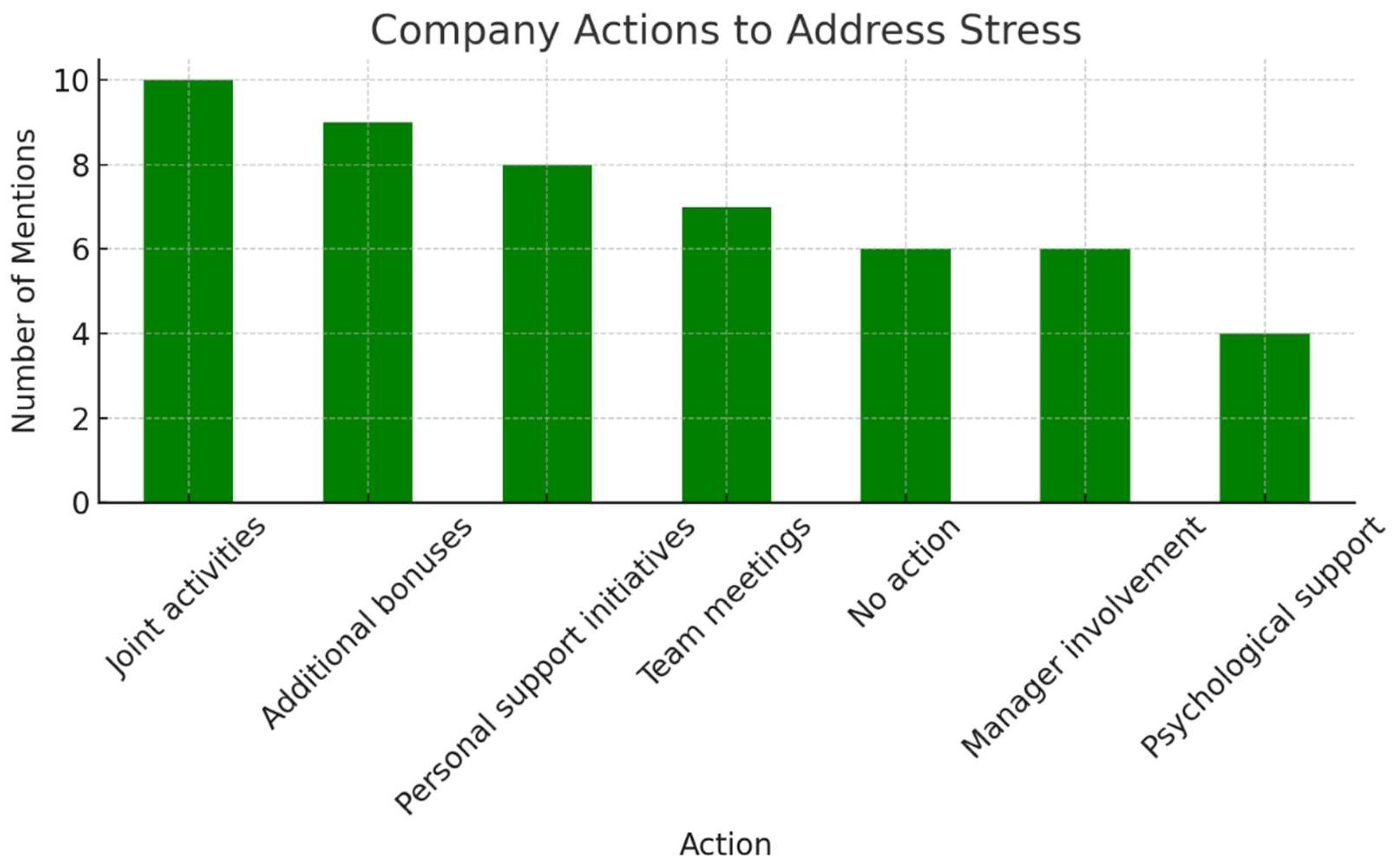

Figure 6 displays the steps companies have taken to lower employee stress under crisis.

This information helps us to evaluate which policies worked best and points out areas for business development. Ten respondents cited Joint activities as the most often referenced metric. Such actions include both virtual and in-person initiatives that promote team community, interpersonal relationships and employee emotional well-being. This measure is particularly effective in reducing feelings of isolation and strengthening employees’ connection to the team. In second place was Additional bonuses, mentioned 9 times. Companies often gave financial bonuses to help staff offset growing workload or inspire them. In the near run, this behavior might help to raise job satisfaction and staff engagement. Personal assistance programs—also cited nine times—are another often used benchmark. This category covers personal attention to staff members, for instance, more flexible work schedules, the ability to work remotely or under specialized assistance in some cases. Such actions enable staff members feel more valued and assist to reduce stress brought on by personal or professional problems. Another valuable tool are team meetings, which got eight references. These kinds of conferences give a chance to talk about present difficulties, preserve open lines of contact and improve team performance. This lessens loneliness and makes staff members’ active participants in the operations of the company. Seven respondents, nonetheless, said their businesses did nothing at all. This outcome suggests that some companies were not ready to handle the stress employees felt during an emergency, which would have affected job satisfaction and staff output. Furthermore highlighted seven times is manager involvement, which underlines the significance of managers in employee emotional well-being. Although managers can be very significant, this instrument has not been extensively applied maybe because managers lack the knowledge or ability to handle stress-related issues. Psychological support received the least attention, and was mentioned by only 6 respondents. This suggests that most organizations have not paid enough attention to providing professional psychological services to employees, although this measure could be one of the most effective in solving stress problems.

Figure 6 reveals that companies, in order to reduce stress, focused mainly on promoting community (joint activities, team meetings) and material motivation (additional bonuses). Such actions are useful for increasing short-term employee satisfaction, but they do not address the deeper causes of stress, such as emotional exhaustion, anxiety or a sense of isolation.

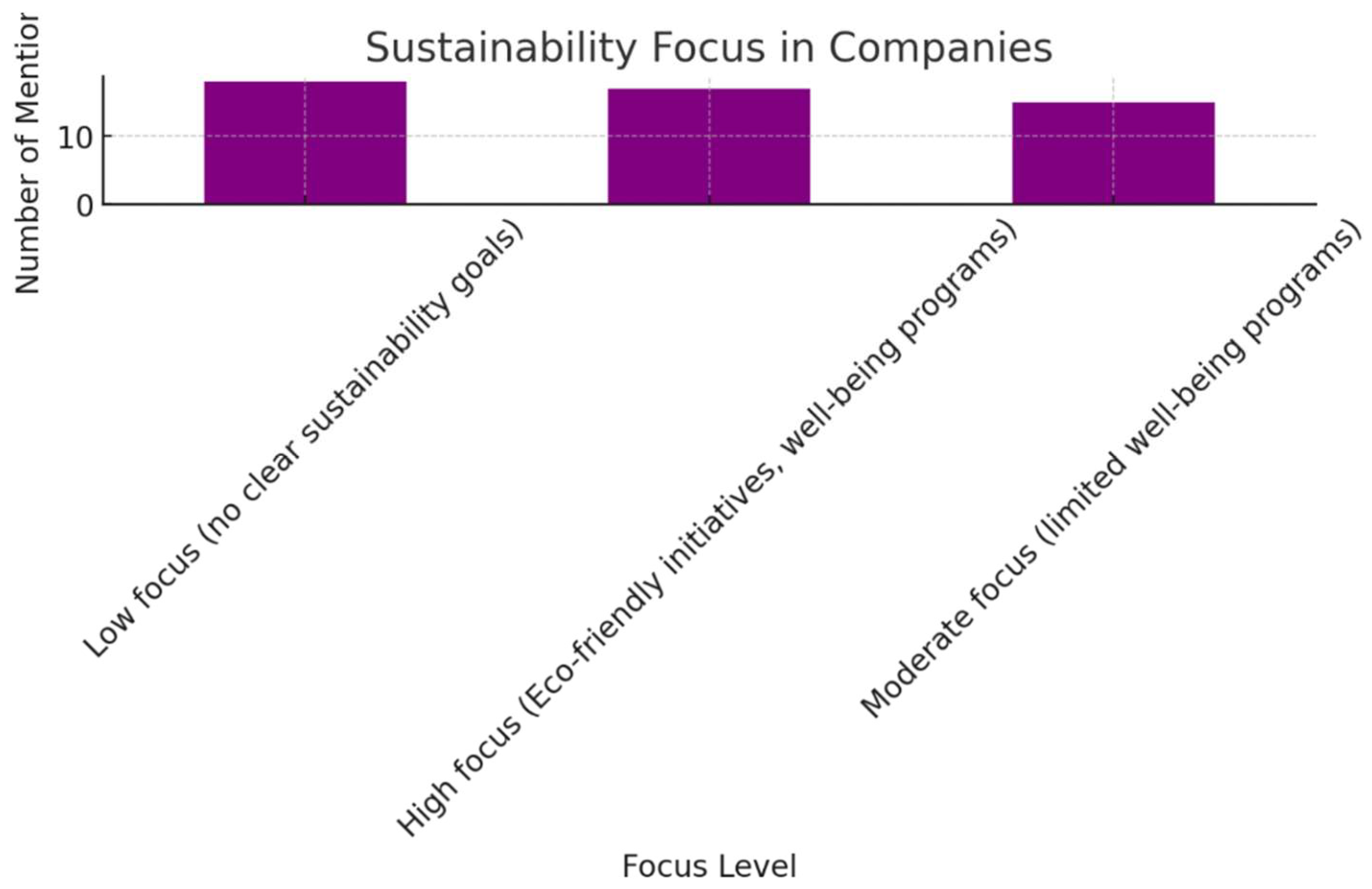

Figure 7 shows the varying degrees of implementation of sustainability goals and activities by different companies.

Three basic groups define the results: businesses paying low, medium or high attention to sustainability. This distribution shows the many goals and orientations of actions of companies connected to employee welfare and environmental conservation. The grouping Low focus: 11 mentions of no defined sustainability goals received. Businesses falling under this category lack clearly defined sustainability goals or strategies and their operations lack environmental protection or social responsibility projects. This could have something to do with inadequate company resources, ignorance of sustainability or lack of prioritizing of it. Such a position can have negative consequences not only for the reputation of the organization, but also for employee satisfaction and long-term stability of the company's operations. In second place with 10 mentions is the category High focus – Eco-friendly initiatives, well-being programs. Companies in this category implement various sustainability initiatives, such as promoting green activities, reducing waste or developing employee well-being programs. These organizations are often socially responsible and pursue long-term goals that contribute to a better image, greater employee engagement and motivation. The well-being programs that were mentioned nine times were constrained in the third category, Moderate focus. These organizations prioritize employee well-being initiatives, which span only a portion of their sustainability initiatives. Despite the potential for positive short-term outcomes, such endeavors do not always guarantee long-term outcomes. This indicates that these organizations may face challenges related to a lack of resources or limited attention to strategic sustainability planning.

Figure 7 allows us to see that the approach of organizations to sustainability and employee well-being varies greatly. The majority of companies still pay low attention to sustainability, which indicates a lack of prioritization in this area. This may lead not only to a negative impact on employee motivation, but also to insufficient adaptation to the growing societal and market pressure to implement sustainable solutions. Meanwhile, companies with a high focus on sustainability show positive trends that can encourage the progress of other organizations. The implementation of environmental initiatives and employee welfare programs creates value not only for employees, but also for society as a whole, promoting long-term growth of organizations and resilience in times of crisis. A medium focus on sustainability shows that some companies are trying to implement sustainability goals, but their actions are usually limited. This may be related to financial or organizational constraints that prevent the full integration of sustainability principles into the business strategy.

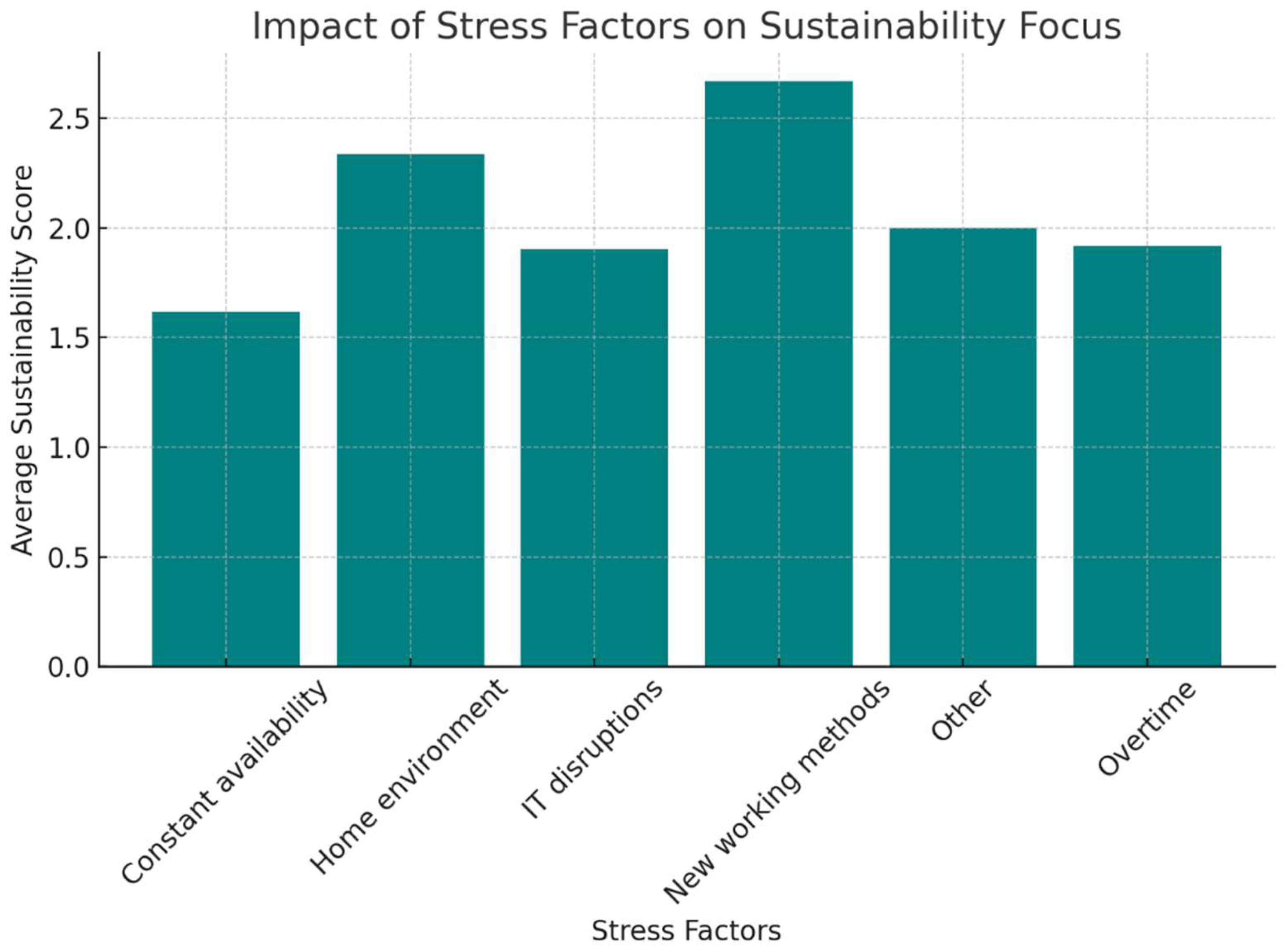

Figure 8 shows how different stressors affect organizations’ ability to focus on sustainability initiatives.

The Average Sustainability Score reflects how each factor affects employees’ engagement in sustainability goals and the organizations’ strategic priorities. Constant availability is the factor that has the greatest negative impact on sustainability focus. With the lowest average sustainability score (around 1.5), this factor indicates that employees who are pressured to be constantly available often experience burnout and emotional exhaustion. This work organization model makes it difficult to focus on long-term initiatives, such as environmental protection or employee well-being. Constant availability not only reduces employees’ productivity, but also weakens their motivation to participate in additional projects. Home environment, with an average sustainability score (around 2.5), also significantly affects organizations’ focus on sustainability. In remote working conditions, employees often face inappropriate workplaces, noise, household chores, or family responsibilities. These challenges prevent employees from effectively performing core tasks, which reduces the energy and time that employees can devote to sustainability initiatives. IT disruptions, such as poor technological infrastructure or connectivity issues, scored an average sustainability score of around 2. These disruptions hinder efficient work organization and often divert employees’ attention from problem-solving to strategic goals. This is especially true for organizations that rely on digital platforms and virtual communication. In contrast, new working methods has the highest average sustainability score of around 2.7. This suggests that organizations that are able to flexibly adapt to new working models have a greater potential to innovate and strengthen their focus on sustainability initiatives. Leadership support and effective change management in this area can be an important factor in increasing organizations’ commitment to sustainability. Other stressors, such as Overtime, with an average score of around 2.3, also have a significant impact. Increased workload reduces employees’ opportunities to engage in additional activities, including environmental programs or socially responsible activities. Similarly, the Other category, with an average score of around 2.5, includes unique employee experiences that also highlight the need to address multiple sources of stress.

Figure 8 reveals that stressors have a significant impact on organizations’ focus on sustainability. Constant availability and IT disruptions are two of the main barriers that prevent companies from maintaining focus on sustainability goals. Meanwhile, the implementation of new working methods shows that flexibility and the ability to adapt to change can become an organizational advantage, allowing them to implement sustainability initiatives even in challenging circumstances. These findings also show how important good stress management is not just for guaranteeing employee welfare but also for advancing the long-term survival of the company. Reducing stressors or creating plans to control them will enable companies not just to enhance their working conditions but also their accountability toward social and environmental problems.

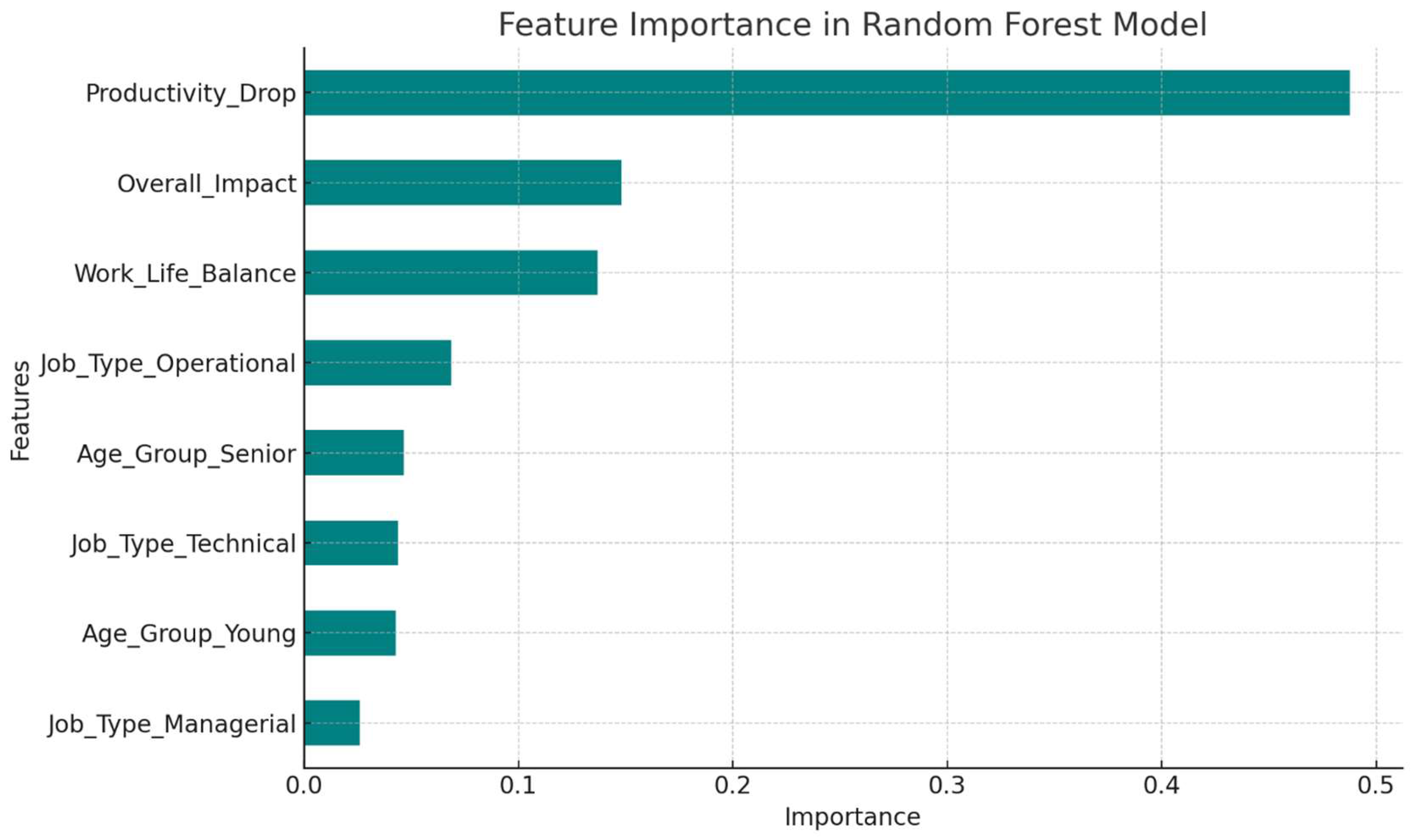

Figure 9 provides data on which features contribute most to the model’s prediction accuracy.

The Random Forest model, as one of the most popular machine learning methods, allows us to assess the influence of different factors on the phenomenon under analysis. The findings of this

Figure 6 show that several elements, such work-life balance and declining productivity, are rather important in determining organizational performance and employee well-being. With a relevance value of roughly 0.45, Productivity Drop is the most crucial characteristic of the model. This suggests that fluctuations in productivity are one of the key factors allowing us to reasonably assess organizational success, employee stress, and emotional condition. When employee output drops, sometimes the first sign that there are unsolved problems in the business—including too much work, stress, or a bad working environment—is a declining employee productivity. The second most important is Overall Impact, with an importance value of about 0.25. This indicator includes the combined influence of various factors, such as stress, working conditions, or employee job satisfaction. The high importance of this characteristic in the model shows that it is important for organizations to consider not only individual factors, but also their overall impact on employee well-being and performance. Third in terms of relevance is job and work life balance; their value comes about at 0.2. This element underlines the requirement of preserving a balance between personal needs and professional responsibilities. Employee mental and physical well-being suffers when they find it difficult to balance these two elements, which can directly affect the operations of the company.

The

Figure 9 presents other factors, such as Job Type Operational, the value of which is about 0.1. This indicates that operational functions have some influence, but they are not as significant as a decrease in productivity or work-life balance. Age Group Young, Age Group Senior and Job Type Technical, Job Type Managerial had relatively low importance in the model (about 0.05). This means that the model assessed these characteristics as less significant for the phenomenon under analysis. The results show that productivity decline is not only the most important indicator of the model, but also the main signal that organizations should pay attention to in order to manage employee stress and ensure their well-being. Monitoring productivity indicators allows for early detection of potential problems that may have a negative impact on the organization's performance. Work-life balance also remains one of the most important factors, emphasizing the need to create a work environment that ensures employees can balance work and personal needs. Despite their lower importance, age groups and job types can be significant in specific situations, so they should not be ignored. These results allow us to conclude that the random forest model effectively reveals which characteristics are most important in predicting employee well-being, productivity and organizational effectiveness.

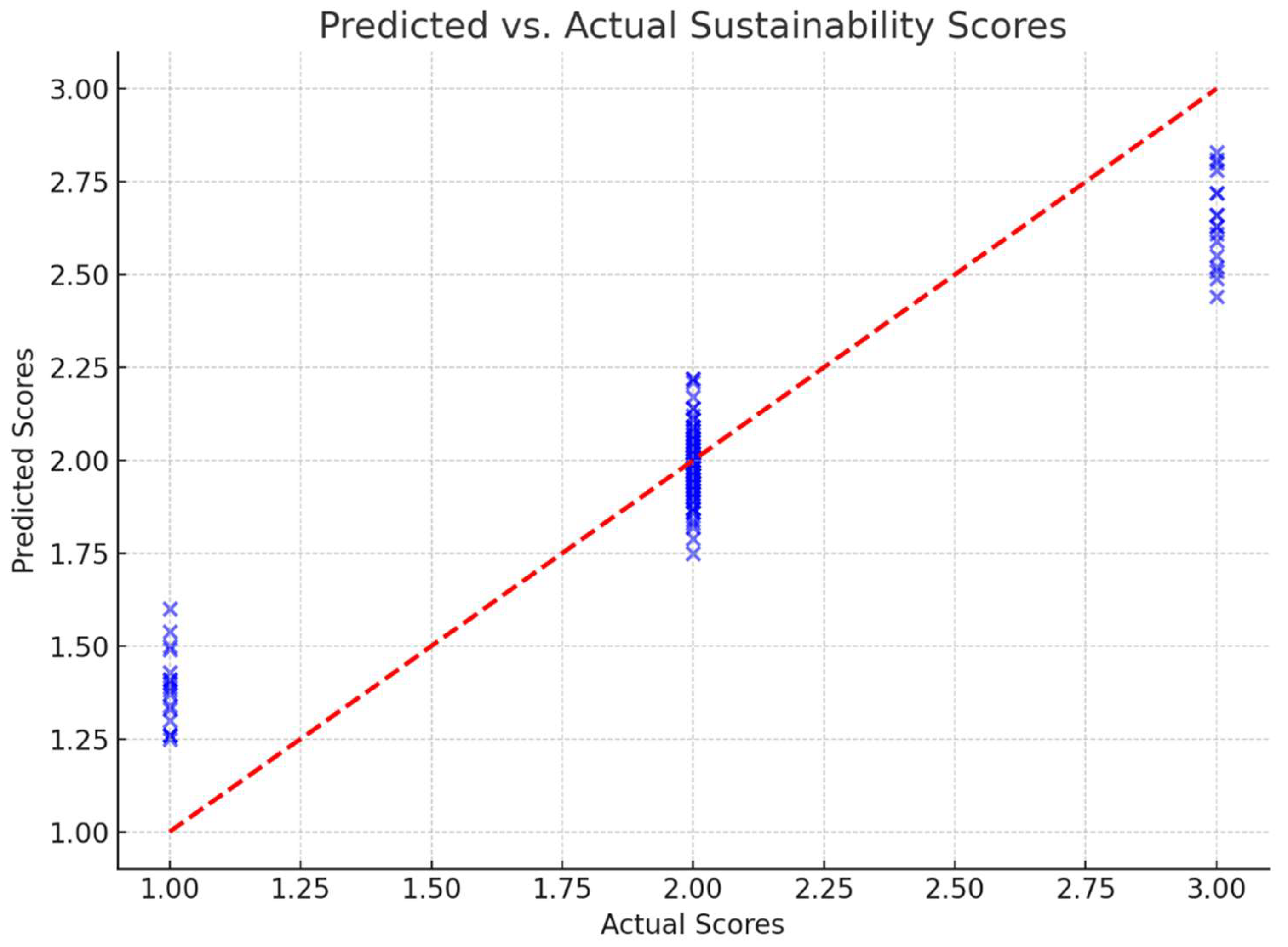

By means of a comparison between projected values (vertical axis) with actual values (horizontal axis),

Figure 10 shows how precisely the model forecasts sustainability ratings. In a perfect prediction match—where the expected values exactly match the actual values—the red dotted line marks ones near this line show accurate predictions; ones far from suggest model mistakes.

Three primary groups of actual scores—1.0, 2.0, and 3.0—show up on the graph. These groups most certainly match the way sustainability scores are categorized into several tiers: a) 1.0: Attached by companies lacking a strong sustainability dedication, this is the lowest degree of sustainability. b) 2.0: Medium level of sustainability, which indicates partial but not comprehensive sustainability initiatives. c) 3.0: The highest level of sustainability, reflecting the most advanced initiatives by organizations in this area.

Lowest sustainability level (1.0): The model predicted scores for this group quite accurately, with most of the points falling very close to the red line. This implies that the approach is useful in spotting companies with the least concentration on sustainability.

Level of medium sustainability (2.0) Given certain departures from the red line, the prediction accuracy in this group is somewhat lower than that in the lowest level. This may indicate that the model has difficulty distinguishing moderate sustainability features, possibly due to the greater variability in the data for this group.

Highest sustainability level (3.0): This group shows larger deviations, indicating that the model does not always accurately predict high sustainability scores. The points are still concentrated near the red line, but some results are overestimated or underestimated.

All score groups have small deviations from the red line. This suggests that the model sometimes tends to overestimate or underestimate sustainability scores. These errors are not very pronounced, so the model performance remains quite reliable. The performance and accuracy of the model can be deduced from the graph's outcomes in several really significant ways. First, the model presents some accuracy problems at higher levels (2.0 and 3.0), yet it fairly forecasts the lowest sustainability level (1.0). This can be attributed to the following factors:

Organizations with medium and high sustainability levels may have a wider range of characteristics, making it more difficult for the model to make accurate predictions.

In the case of higher sustainability levels, there may be a lack of specific data or variables that would more accurately describe the characteristics of this group.

At higher sustainability levels, the relationships between factors may be more complex, and the model may not always be able to handle them accurately.

Despite these challenges, the overall accuracy of the model is quite good, especially when it comes to organizations with lower sustainability levels. This suggests that the model can be useful in predicting general sustainability trends and assessing the effectiveness of organizations’ commitments.

3.2 Assessing the effectiveness of sustainability strategies in emergency situations

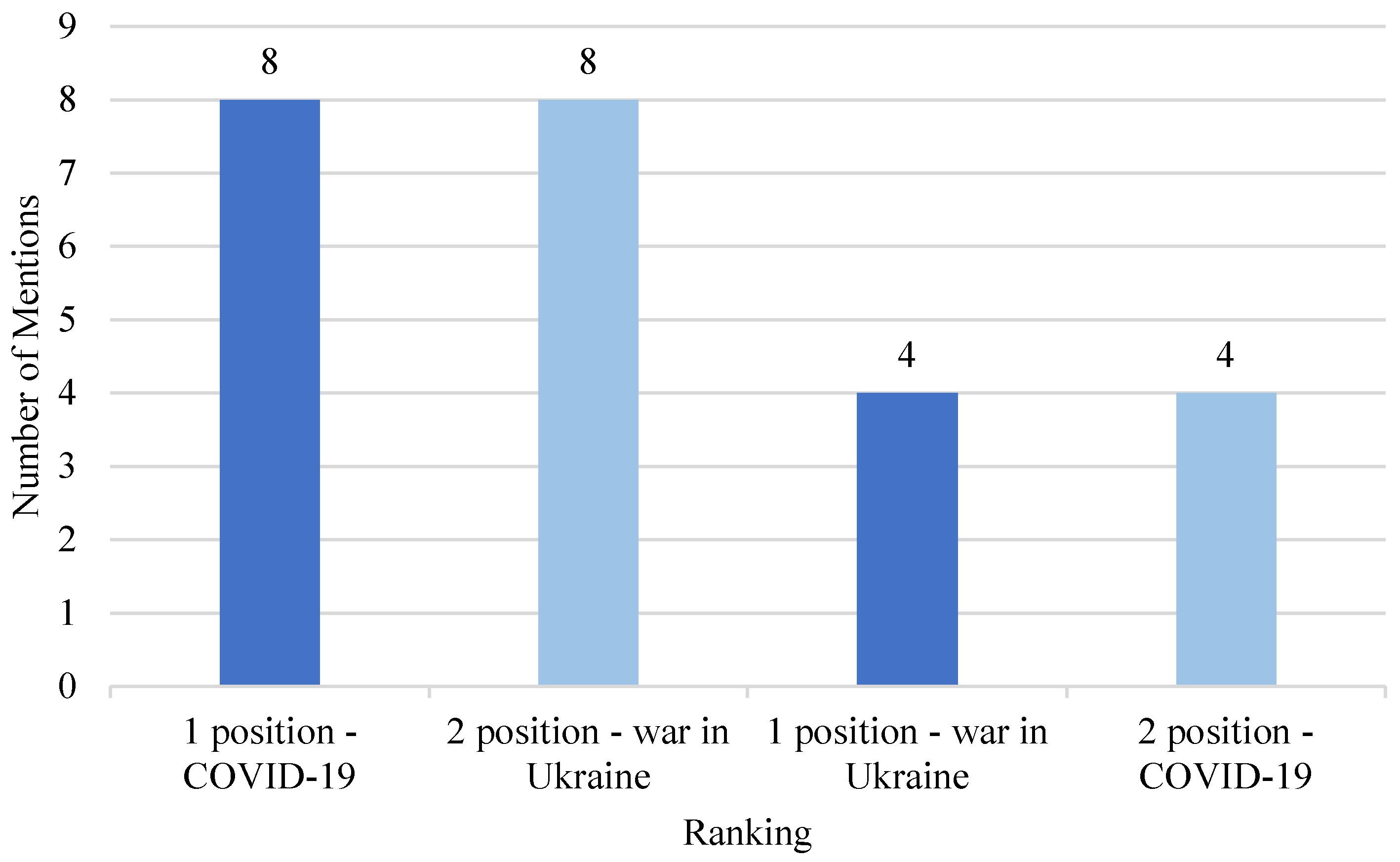

One of the objectives of the study is to find out which emergencies respondents consider to be the most important and which are less important. A ranking form was chosen for the question, where the most important event, in the opinion of experts, is assigned to position 1, and less important events are assigned to positions 2 to 4. The experts were presented with four emergencies: the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, mass worker protests, and terrorist attacks. The results of this question can be presented in a diagram (see

Figure 11).

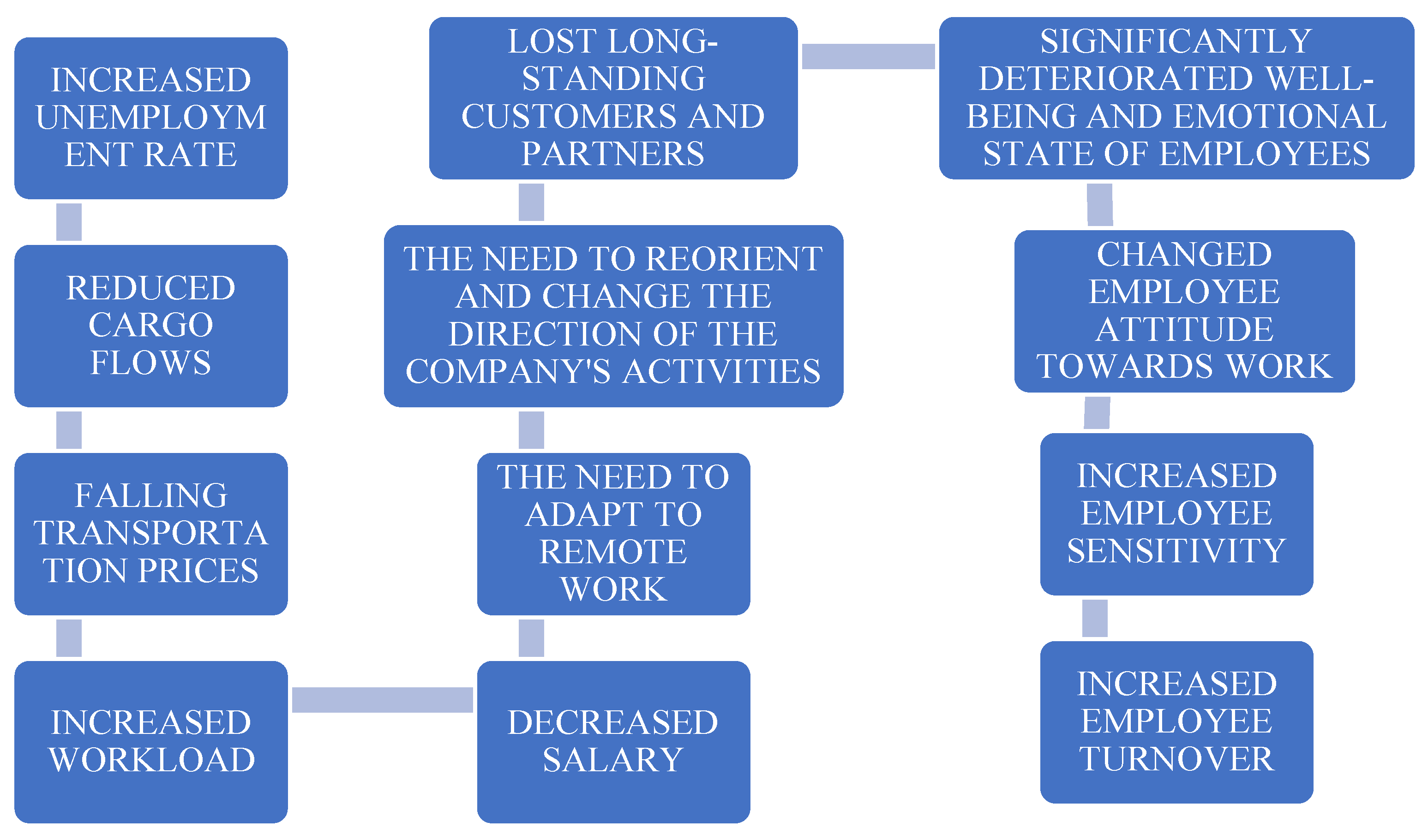

From the presented diagram, it can be stated that the vast majority of experts – 8 out of 12 – rank the COVID-19 pandemic as the most significant and most negatively impacting emergency in the first position, and the war in Ukraine in the second position. In order to determine how the specifics of the respondents’ work changed during the COVID-19 pandemic or after the war in Ukraine began, the respondents described the changes related to the specifics of the work (see

Figure 12).

According to experts, the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have caused a lot of negative consequences at the entire level of the company, starting with employees and ending with the overall performance of the company. These extreme situations, first of all, affected the employees. During the pandemic, a large part of the employees were sick and unable to work, and their mood and well-being changed significantly; tension and a sense of insecurity appeared. People became suspicious and sensitive; the general attitude towards work changed—work productivity and efficiency decreased significantly, and employee turnover increased. Reduced wages led to general sluggishness among the employees. The need to adapt to remote work caused a lot of inconvenience for some employees—they had to learn to work with programs and systems, and smooth work was disrupted by information technology problems (internet connection disruptions, slow operation of programs and systems). The introduced restrictions, sanctions, and hygiene requirements have fundamentally changed the logistics and freight market. Transportation prices fell sharply, cargo flows decreased significantly, competition among companies increased, and overall company performance fell. Certain restrictions imposed led to the loss of long-standing customers and partners, forcing companies to quickly change their business directions. The responsibility for reorienting the company's activities largely fell on employees, meaning that in order to achieve the same result, it was necessary to put in twice as much work. Explaining logistics human resource management practices and strategies in an extreme situation, experts described the specifics of the work of employees in different company departments (see

Table 1).

The statements of the respondents presented in

Table 1 make it clear that the administration and managers experienced the most changes, but managers had an exceptionally large responsibility for managing the personnel. Managers were forced to look for ways to retain employees, motivate them and find effective solutions by changing the company's field of activity and the destination countries and markets with which they had worked until then. It can be concluded that only close and coordinated work of all departments allowed the companies to "survive" and promptly search for ways and solutions, adapting to the circumstances of the current emergency situation and the negative consequences caused. The experts were also asked what measures were applied in the company in order to properly organize the work of personnel in the context of the emergency. The majority of experts stated that all the measures applied were effective, but "it was always possible to react better, to do better, but the situation was not ordinary, so it was not possible to avoid mistakes." It is appropriate to specify the work organization measures that were named by the respondents:

• The hybrid work model—worked.

• Psychological assistance and wellness services—worked.

• Daily meetings to discuss current issues affecting work activities—worked.

• Vacations granted at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in order to control employee flows and minimize the risk of infection worked.

• Maximum use of information technologies in organizing regular work processes worked.

• In the context of the war in Ukraine, respondents stated that special measures were not introduced into the company's daily procedures; only the emotional state and financial situation of employees who were very closely related and directly affected were taken care of.

When assessing the circumstances of emergency situations, it is obvious that employees had to fully adapt to work using the opportunities provided by information technologies. In response to the question, all twelve people who answered agreed that companies used hybrid work models to manage their employees during the emergency. These models let everyone work from home, and the IT departments made exceptions for employees by connecting them to internal company networks and systems. Several companies additionally invested in the development of information technology at the company level: they purchased new systems, computers, licenses for programs, and projectors for offices so that employees could communicate remotely with clients and hold meetings with partners. Unfortunately, when interviewing experts, opinions differed on how remote work affected efficiency compared to working in a regular workplace. Respondents stated that:

1) Some employees showed irresponsibility when they were unable to perform their direct functions.

2) Work efficiency did not change.

3) Work efficiency increased because most employees were satisfied with the possibility of working from home.

4) Work efficiency decreased significantly, and difficulties arose in communicating with closely related colleagues.

5) The time for solving problems and making decisions increased, as there was no more “live” communication with colleagues, and communication had to be done via letters or calls.

6) Work efficiency decreased due to the home environment; some employees relaxed, and some could not concentrate because they had to isolate themselves with other family members.

7) Work efficiency decreased due to constant uncertainty and lack of a sense of security.

8) Some employees found the beginning challenging, but they later noticed a positive change.

9) Some employees were not ready to work independently, so their results deteriorated.

Upon reviewing the aforementioned statements, we can conclude that remote work impacted employees in diverse ways. Several respondents highlighted that self-motivation and the pursuit of results were extremely important when working from home. In order to assess which factors had the greatest impact on employees’ work efficiency and emotional state, experts were provided with tables with a list of different factors and a ranking form. Two main questions were selected for the assessment:

1) What causes you stress when working remotely?

2) Did the factors presented for assessment influence your well-being during the emergency situation(s)?

The

Table 2 shows that some experts unanimously hold several positions:

1. Information technology disruptions, such as internet connection disruptions and lack of necessary equipment, cause stress for as many as 5 out of 12 experts.

2. 5 out of 12 experts indicated that the need for constant availability caused them stress.

3. 2 experts in the field "Other (enter your own)" mentioned on their own initiative the deterioration and prolonged communication with other colleagues due to remote/hybrid work or unavailability.

Notably, anxiety affected 7 of 12 experts' overall well-being. On his own initiative, one of the experts identified constant stay in a closed room with his family as a factor that negatively impacted his well-being during an emergency. In order to find out what measures the company took to reduce the risk of “burnout” or other negative consequences for employees during emergencies, the experts answered this question very differently:

a) 4 out of 12 experts answered that the company did not take any measures;

b) 2 out of 12 experts answered that the company provided psychological assistance;

c) 2 out of 12 experts answered that the manager paid special attention to the employees and their well-being;

d) 1 out of 12 experts answered that the company tried to maintain normal communication by organizing meetings in which everyone participated with cameras;

e) 1 out of 12 experts answered that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the company tried to motivate employees with an additional bonus system, and when the war in Ukraine began, it took into account the general mood of the employees more, therefore it began to organize joint activities after working hours. For example: joint dinners, team games, and visiting cinemas;

f) 1 out of 12 experts answered that employees were consulted not only on work-related but also on personal issues;

g) 1 out of 12 experts answered that no measures were taken at the company level, but the personal initiative to engage in sports after working hours helped to reduce stress and distract from work.

Experts also answered differently to the question of whether the company provided the necessary support and encouragement to employees during the emergency situation(s). 8 out of 12 respondents answered positively: companies organized various trainings in psychology or working with information technologies; constant communication within the companies allowed them to feel more confident about the future, helping psychologically and financially. Employees were consulted on various issues, and discussions were constantly held about the hybrid work model in order to ensure the best possible conditions for them. The circumstances of extreme situations led to positive changes within the company—personnel management specialists and managers appeared in the company; the LEAN system began to be applied in daily tasks, on the basis of which "Asaichi" meetings are held in the departments; and the Kai-Zen method, when all employees of the company are included in the processes, was used to optimize or improve complex and stalled processes. Some respondents stated that the companies did not care about the well-being of employees; as usual, there was pressure to achieve high performance. In order to identify the shortcomings of existing human resource management practices and strategies, the experts were asked two questions:

Does the company have a specific action plan in place to manage personnel during an emergency situation(s)?

What additional measures should the company take to manage personnel during an emergency situation(s)?

The results of the experts' answers to the question, "Does the company have a specific action plan in place to manage personnel during an emergency situation(s)?" were essentially the same, i.e., the majority said no, and the rest said that if there is such a plan, I do not know. Such results were somewhat surprising, considering that over the past three years, the world has been shaken not only by a pandemic but also by military conflicts. Such positions among companies are unusual and signal a threat in the future if the same or similar emergencies occur. Companies, based on past events, must prepare not only personnel management but also company activity plans with special responsibility. A clear plan, various trainings according to situations, and an introduction to possible alternatives of actions—this is what allows you to start acting and make rational decisions in the face of an emergency. In response to the last question, experts shared their thoughts on how companies could improve the personnel management situation in an emergency. Taking into account the experts' opinion, five main statements were distinguished:

1) Not only to be interested in the emotional and psychological state of employees but also to pay more attention to it by organizing courses, training, or other educational activities and providing the necessary help or support.

2) To invest more in employee motivation, workplaces, and personnel flexibility in emergency situations.

3) To provide all opportunities to have a place at home adapted for work.

4) Encourage active rest of employees after work by organizing group activities or providing discounts/compensations for wellness services or procedures.

5) Fully involve all staff groups in preparing for unexpected and emergency situations. Taking into account the results obtained during the study, it is necessary to conduct a simulation of the situation and create a human resource management model.

4. Discussion

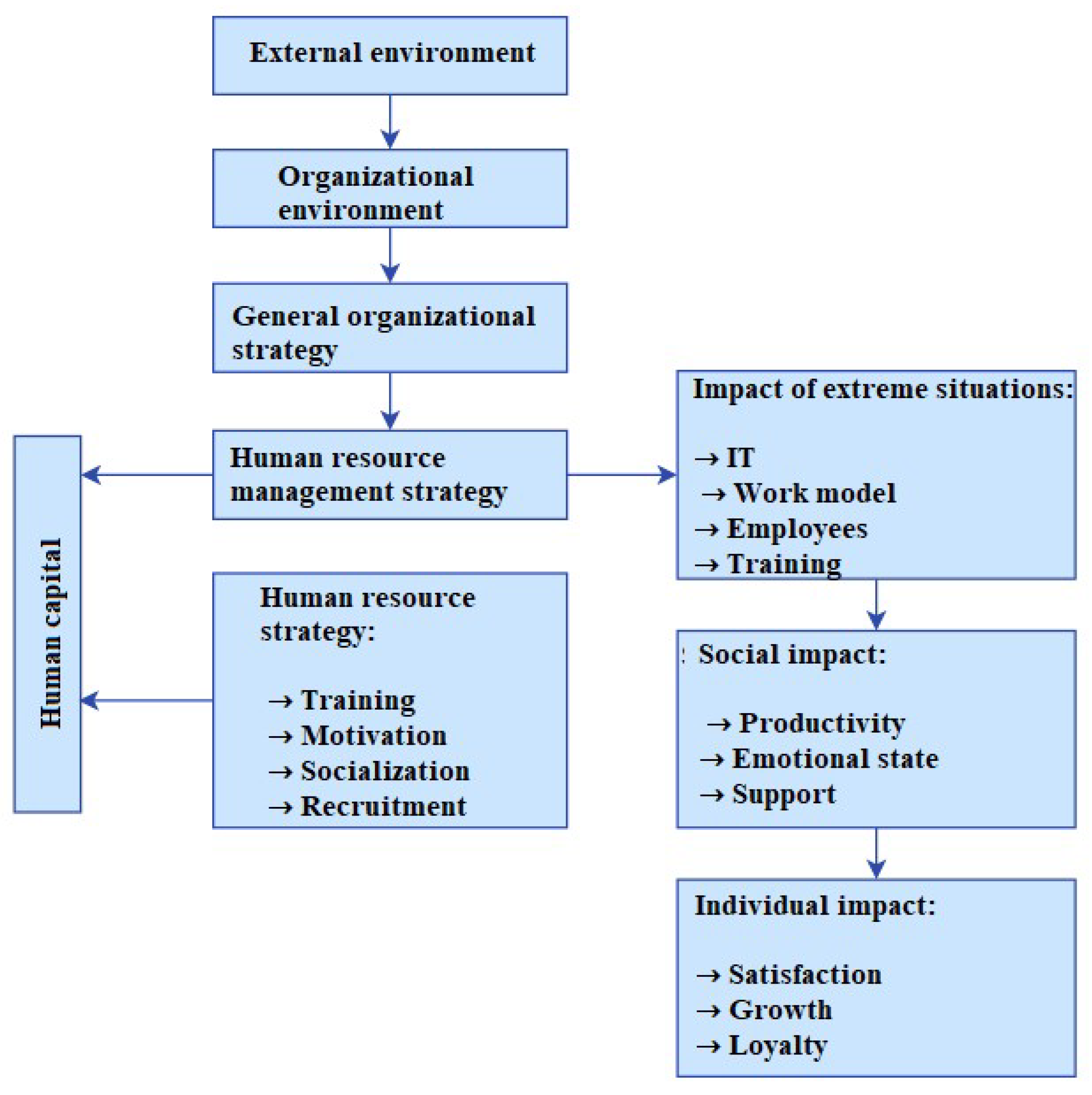

In order to optimize human resource management in an emergency situation, it is appropriate to envision a model based on which companies could minimize the negative impact on employees (see

Figure 13).

The emergency situation has the greatest impact on the following areas of the company:

• Information technology. Employees must fully familiarize themselves with all company systems and programs in the event of an emergency. Employees must be given all the necessary equipment (computer, phone, system access) and familiarized with databases to ensure uninterrupted work and avoid problems caused by employees' incompetence with systems, programs, or additional equipment.

• Work model. An emergency situation can fundamentally change the established work model. In the case of the Covid-19 pandemic, employees were forced to work from home in order to minimize the number of contacts and the level of risk of infection. For this, it is necessary to prepare in advance: plan a workplace at home so that, if necessary, it can be implemented within the next 24 hours. Make sure that employees have uninterrupted access to all necessary systems, databases, contacts, etc.

• Employees. Employees are the main driving force of every company. When employees are not properly cared for, they lose motivation, become withdrawn and sluggish, their productivity and efficiency decrease, loyalty becomes meaningless, and employees often start looking for work elsewhere. Prioritizing their psychological health and emotional state is crucial for maintaining employee motivation. The results obtained during the study showed that most respondents experienced anxiety; they lacked “live” communication. Managers should take this into account and create systems that reduce the negative emotions experienced by employees during an emergency situation, as far as the work environment is concerned. Motivational systems can be provided not only in monetary terms but also in support, access to psychological consultations, and the organization of joint activities.

• Training. All problems and negative areas identified during the study can be addressed through training. IT training, training to work in a hybrid way, lectures on how not to lose motivation, discussions on psychological health individually and at the company level.

In summary, it can be said that emergencies such as a pandemic, military conflicts, or other crises can have a significant negative impact on companies operating in the logistics sector. Guaranteeing employee proficiency with all company systems and programs is crucial. Companies must be prepared in advance to adapt their work models by allowing employees to work from home or other alternative locations. It is important to ensure that employees have the necessary equipment and access to essential systems. Managers should pay special attention to the emotional state of employees by organizing different support and assistance systems and measures. Training is becoming an indispensable tool for companies to solve problems and improve employee skills. This includes both technical and psychological training that would allow employees to adapt to new work models, maintain a high level of motivation, and manage stress. The coordination of all these factors gives the company flexibility, strengthens employee relationships, and helps maintain efficiency even in emergency situations.

5. Conclusions

Based on the analysis of scientific sources, we can define human resources as the competence, skills, experience, and qualifications of employees. If a company properly adapts and coordinates the totality of these elements, its competitive advantage in the market grows. Human resource management methods and models implement this goal, providing guidelines for proper operation. In order to maintain the effectiveness of these methods, it is appropriate to periodically review the provided guidelines or adapt new models as needed to fulfill the maximum potential of the company. The scientific literature distinguishes two categories of human resource management functions: managerial and operational. Human resource functions include various processes—from hiring employees to assessing their performance. The effectiveness of the company's activities depends on the well-coordinated work of its employees, except in emergency situations.

The study showed that high stress levels compromise the sustainability scores of companies. Higher degrees of emotional tiredness and anxiety among the staff members reduced their drive and sense of organizational commitment. This suggests that short-term crisis solutions like one-time compensation or support packages are inadequate to ensure long-term welfare of employees. Instead, organizations should invest in psychological support programs and long-term employee well-being strategies that would not only reduce stress, but also ensure their motivation and loyalty.

The results of the analysis show a clear link between work-life balance and the level of organizational sustainability. Organizations that organize work flexibly during crises, promote hybrid working models and invest in digital technologies achieve better employee well-being indicators. Moreover, this allows them not only to reduce stress, but also to implement sustainability strategies more effectively.

The research also revealed that a decrease in productivity during a crisis can have long-term consequences for the organization's sustainability results. Companies that clearly supported visible support initiatives including better working conditions and employee incentive programs kept better productivity and sustainability ratings. Moreover, sentiment analysis found links between sustainability ratings and staff morale and engagement. This indicates that companies who proactively meet employee needs and promote a strong corporate culture can keep long-term competitive.

The results obtained during the expert study revealed that emergency situations most strongly affect the information technologies of companies, their work model, employees, and training. In emergency situations, an essential aspect of information technologies is the preparation of employees. It is important to ensure that employees not only have the necessary equipment for their work but also are familiar with the systems and programs used by the company in order to avoid possible problems due to incompetence. An emergency situation can fundamentally change the work model. Proper preparation includes organizing a home workplace and ensuring that employees have unlimited access to the necessary systems and data. Employee well-being and motivation are an essential part of a company's success. The results of the study show that in emergency situations, employees feel stress due to the lack of "live" communication and anxiety.

In summary, it can be stated that emergency situations affect company employees in one way or another: they cause anxiety, make work more difficult, and pose additional challenges not only in organizing the work process but also in achieving results. The results of the expert study revealed that in the event of an emergency, companies in the logistics sector either do not have a pre-prepared action plan at all, or employees are not informed about such a plan and are not involved in its implementation.

Therefore, managers should create systems that would alleviate this situation by providing not only psychological help but also financial support. Training can overcome the problems identified during the study. Both individuals and companies can implement IT training, hybrid work training, motivational support, and psychological health discussions. It might be interesting to look into companies and see how many of them have or are in the process of putting human resource management plans into action, as well as how these plans affect both the employees and the long-term success of the business.