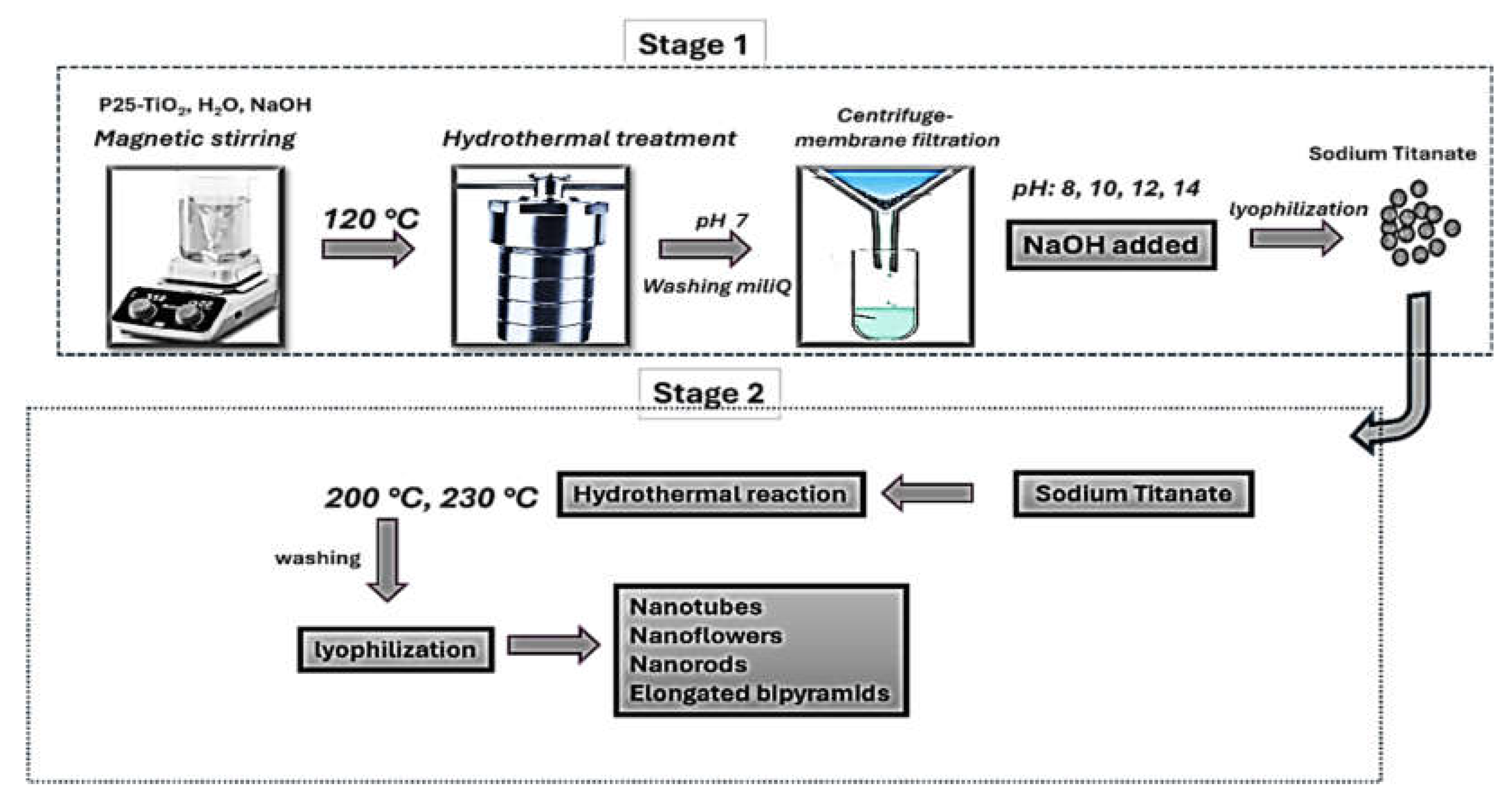

4.1. Structure Analysis

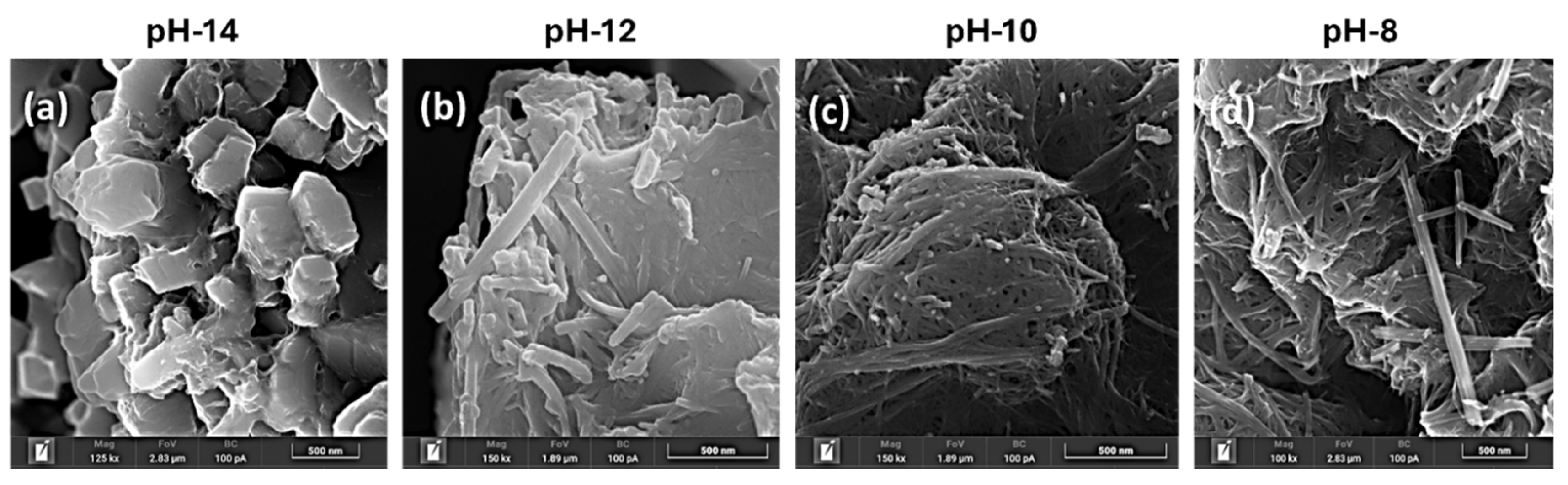

Figure 2 presents the SEM images of the Na-titanates samples, illustrating the significant impact of pH on the morphological evolution of the initial structures. As the pH varies from 14 to 8, morphologies undergo a substantial transformation, shifting from a platelet-like distorted structure to a more elongated rod-fused structure. This transformation is driven by pH-sensitive nucleation and growth processes, highlighting pH's key role in sodium titanate formation of distinct surface morphologies.

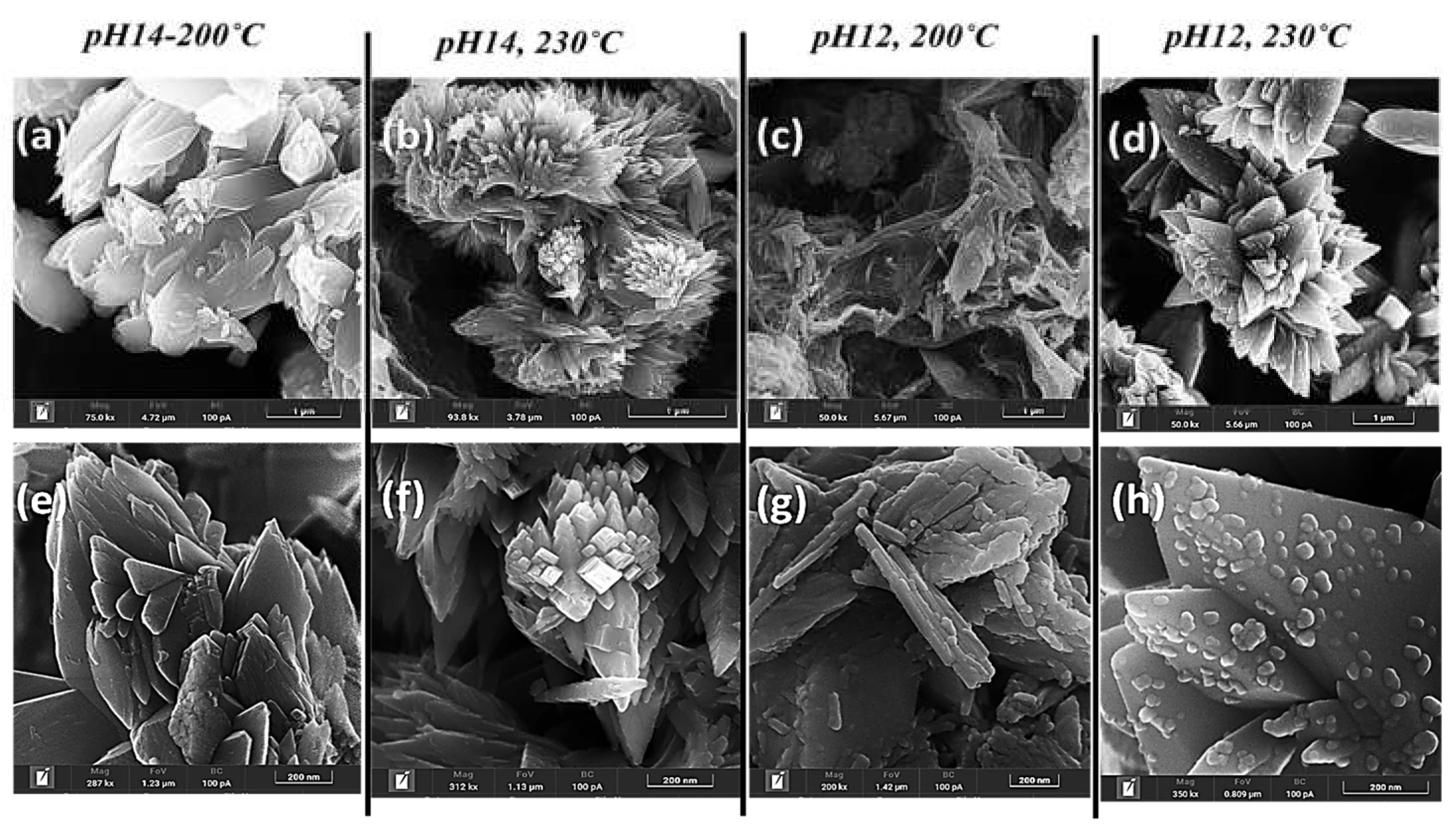

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 depict the morphological evolution of TiO₂ nanoparticles synthesized from Na-titanates (at different pH values) upon thermal treatments at 200°C and 230°C. The results reveal a pH- and temperature-dependent restructuring mechanism.

At pH 14, thermal treatment at 200°C and 230°C induced a transformation from platelet-like Na-titanates to a distinct flower-like TiO₂ morphology (

Figure 3(a, b)). At 200°C, the specimen (pH14-200°C) exhibited a distorted flower-like structure, while at 230°C, the comparatively higher temperature led to a more compact structure with reduced particle size and a more pronounced flower-like morphology (pH14-230°C). The thermal treatment of Na-titanates at pH 12 promoted the formation of disordered fused nanosheet-like structures, resulting in a disordered morphology (pH 12, 200°C) (

Figure 3(c)). However, at 230°C, the increased thermal energy triggered an anisotropic growth mechanism, leading to the self-organization of aloe-vera-like hierarchical structures (pH 12, 230°C) (

Figure 3(d)).

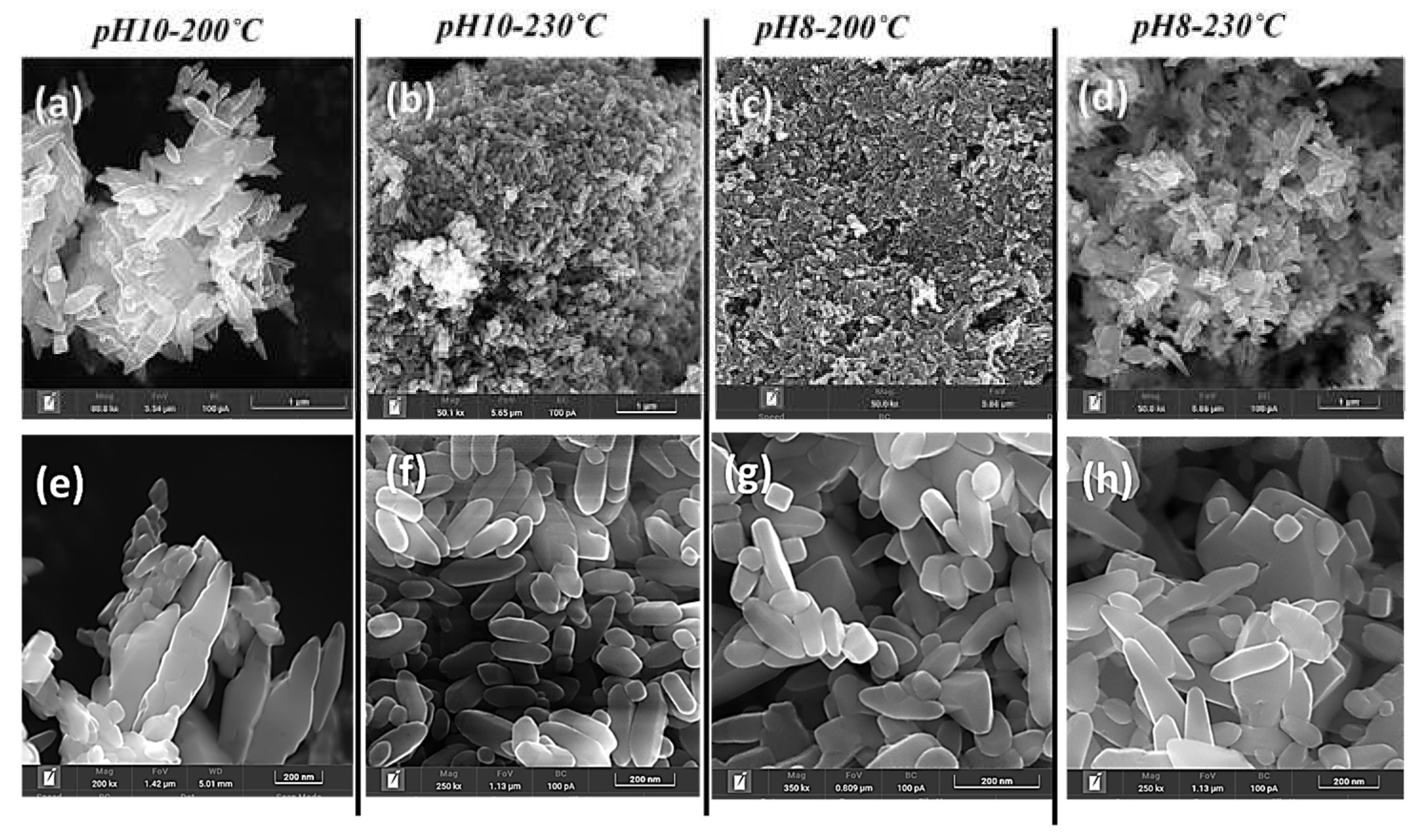

For Na-titanates synthesized at pH 10, the relatively lower alkalinity resulted in a mixture of nanorods upon thermal treatment (

Figure 4(a, b)). At 200°C, thermal treatment promoted the formation of more uniform nanorods, while at 230°C, the higher thermal energy overcame structural rigidity, facilitating the complete scrolling of nanorods into elongated nanotubes. This transition, driven by increased temperature, enhanced structural reorganization and favored nanotube formation, demonstrating a clear temperature-dependent mechanism.

The pH 8, 200°C specimen exhibited the nucleation of TiO₂ with a mixed nanotube/elongated bipyramidal morphology (

Figure 4c). While surface rearrangements were more distinct at 200°C due to a dense population per unit length, increasing the temperature to 230°C resulted in a similar morphology but with a more well-defined shape and larger particle size (

Figure 4d). This suggests that lower pH Na-titanates favour kinetically stable TiO₂ morphologies with minimal reorganization, maintaining structural consistency even with temperature variations. The observed structural evolutions are governed by a complex interplay of pH-dependent hydrolysis, and temperature-induced morphologies. These findings highlight the critical influence of alkaline pH and thermal treatment on TiO₂ morphology and phase transformations (discussed in a later section), which, in turn, impact photocatalytic efficiency by modulating surface area, defect density, and charge carrier dynamics [

23]. The synergy between morphology and phase composition is further explored in subsequent sections to elucidate their combined impact on photocatalytic performance.

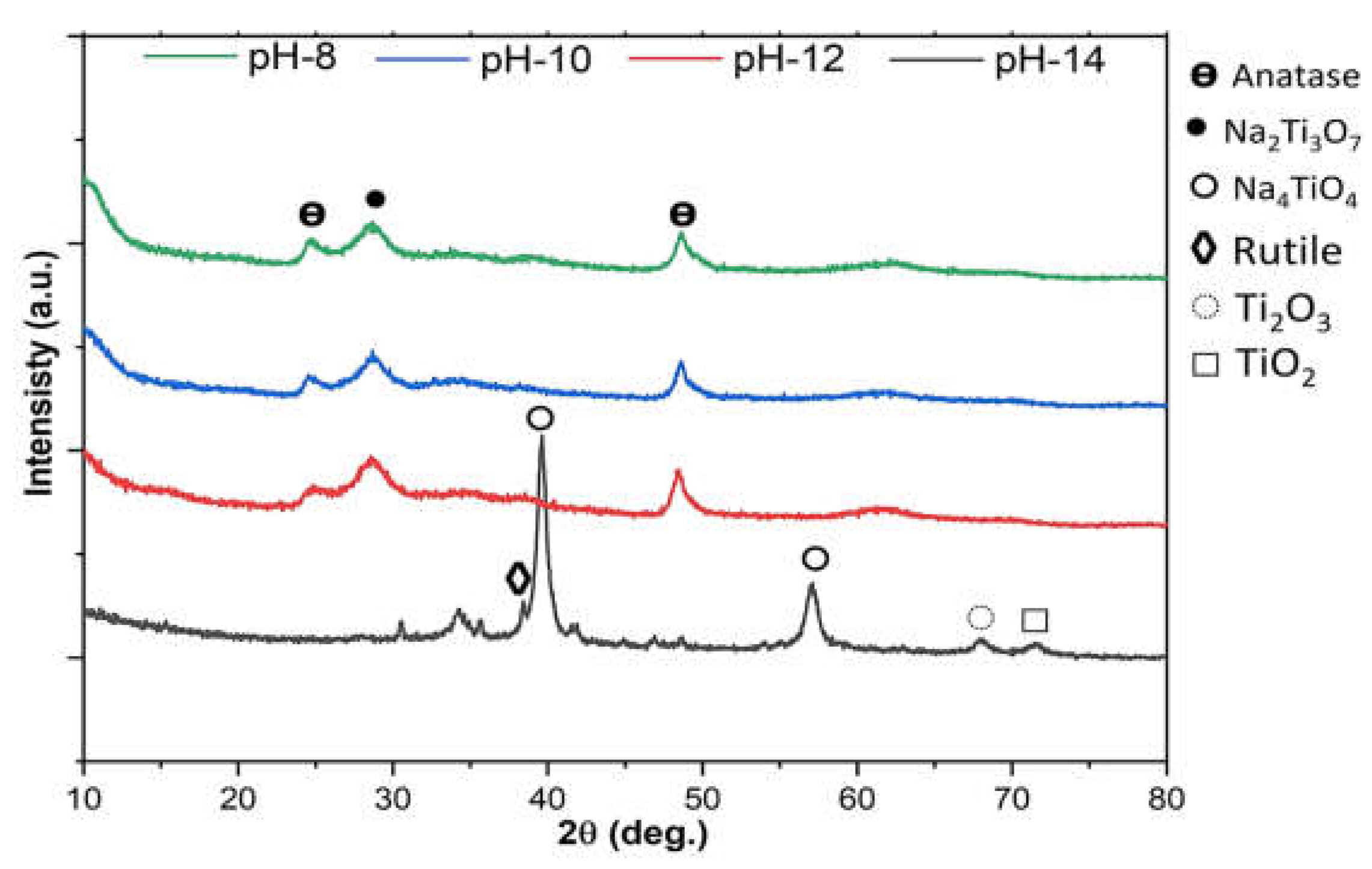

Figure 5 shows the XRD characterization of Na-titanate particles synthesized under controlled pH conditions. The prominent peaks at 2θ values of 28.20° and 48.20° correspond to the characteristic titanate pattern (Na

2Ti

3O

7) [ICDD card no. 04-009-1210]. At pH 14, highly alkaline conditions promote the formation of Na₄TiO₄, exhibiting sharp peaks (indicative of Na₄TiO₄) along with broader peaks corresponding to TiO₂ and Ti₂O₃. At lower pH values (8 and 10), the synthesis results in a mixed-phase composition, including Na₂Ti₃O₇ and anatase, along with potentially amorphous species. Overall, the XRD profile highlights the influence of pH on phase evolution.

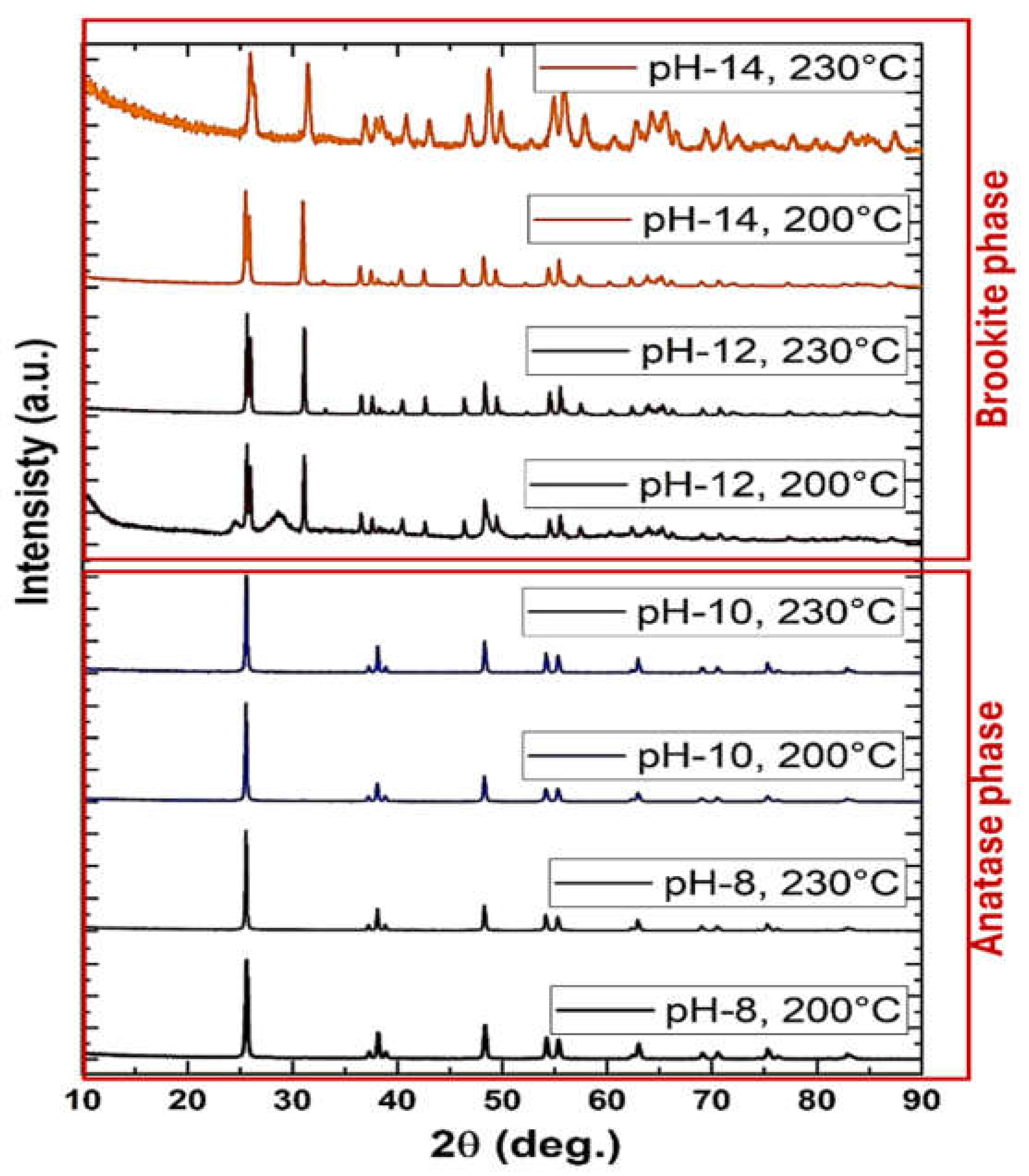

Figure 6 presents the XRD spectra of TiO₂ nanomaterials synthesized via hydrothermal treatment at 200°C and 230°C from Na-titanates at pH 8, 10, 12, and 14. The results highlight the critical role of both pH and reaction temperature in governing TiO₂ phase evolution, enabling precise control over anatase and brookite formation. For TiO₂ nanoparticles synthesized at pH 8 and pH 10 after thermal treatment, distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 25.00°, 37.00°, and 54.00° correspond to the (101), (004), and (211) planes of anatase TiO₂ (ICDD PDF card No. 01-075-2552). These results confirm the successful transformation of Na-titanate precursors into anatase TiO₂, with preferential stabilization of anatase-specific crystal planes. Combined XRD and SEM analyses indicate that moderate alkaline conditions (pH 8–10) favor the nucleation and growth of highly crystalline, phase-pure anatase nanoparticles. In contrast, at higher pH values (12 and 14), the synthesized TiO₂ exhibits diffraction peaks at 2θ = 25.49°, 38.19°, and 54.65°, corresponding to the (111), (311), and (421) planes of brookite TiO₂ (ICDD PDF card No. 04-022-2622). The selective formation of brookite under strongly alkaline conditions is attributed to an increased hydroxyl ion concentration, which induces deprotonation and stabilizes brookite-specific lattice planes by modifying the coordination environment of Ti species. Brookite formation occurs at both 200°C and 230°C, suggesting that pH plays a dominant role in phase selectivity, while temperature primarily influences crystallinity and particle growth. These findings highlight the interplay between pH and synthesis temperature in tuning TiO₂ crystalline phases. The hydrothermal synthesis strategy used here effectively tailors TiO₂ phases with distinct crystallographic properties. While temperature plays a limited role in determining the dominant TiO₂ phase under these conditions, it significantly impacts morphological evolution. The relationship between phase composition and morphology is further explored to elucidate their combined influence on photocatalytic performance.

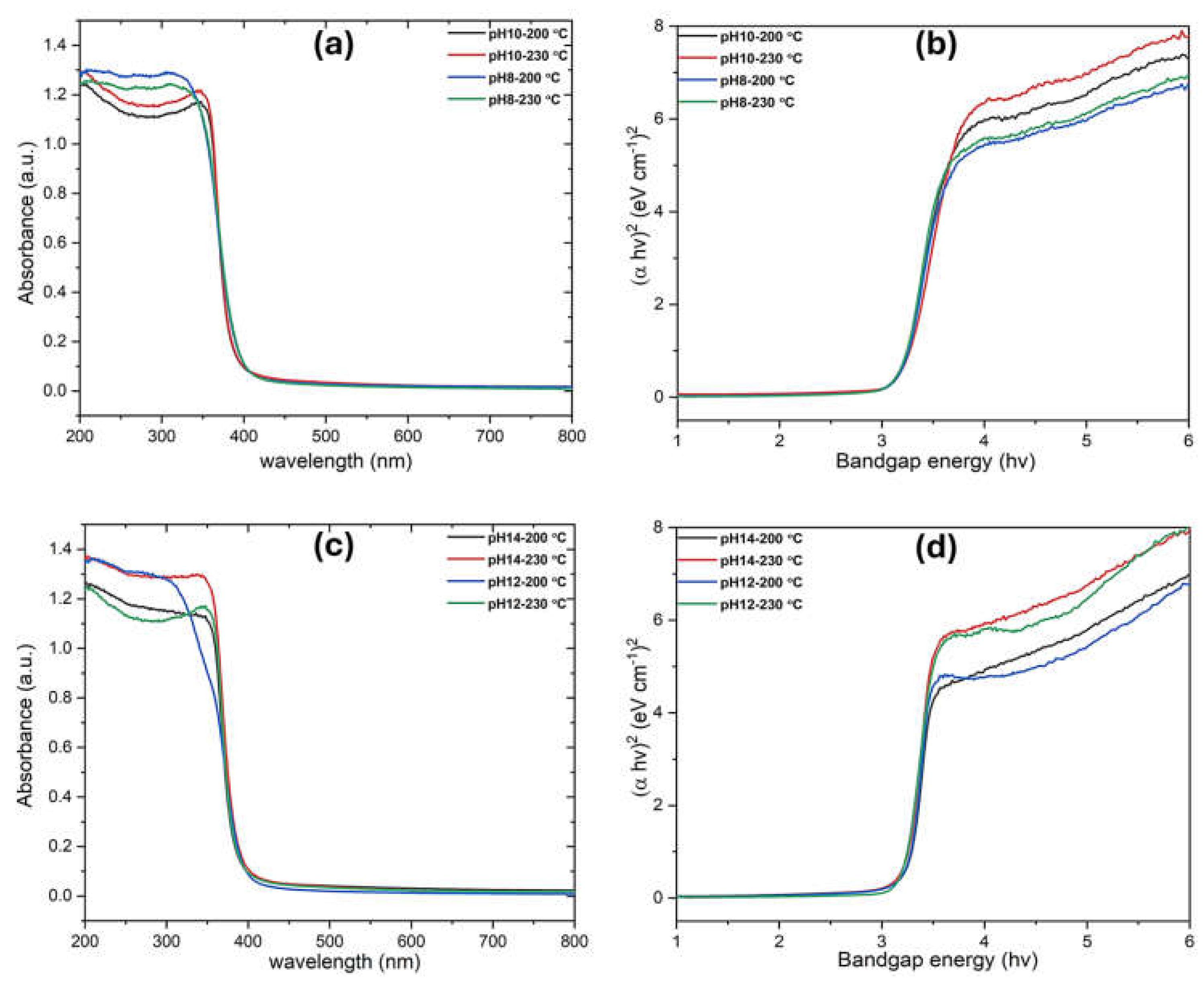

Figure 7 presents the UV-Vis absorption analysis of TiO₂ nanoparticles, with bandgap values calculated from Tauc plots. Samples synthesized at pH 8–10 (anatase phase) exhibit a bandgap of ~3.18-3.20 eV, while those at pH 12–14 (brookite phase) show slightly higher values (3.23–3.28 eV). This increase is attributed to structural differences between anatase and brookite, affecting electronic band dispersion and charge carrier dynamics. The slight difference in bandgap between anatase and brookite TiO₂ with varying morphologies is attributed to changes in surface energy, quantum confinement effects, and crystallographic orientation, which influence electron density and charge carrier dynamics. The results highlight the influence of pH on phase composition and optical properties (

Table 1), offering tunable electronic characteristics for photocatalytic and optoelectronic applications.

4.2. Photocatalytic Degradation of Aqueous Pollutants

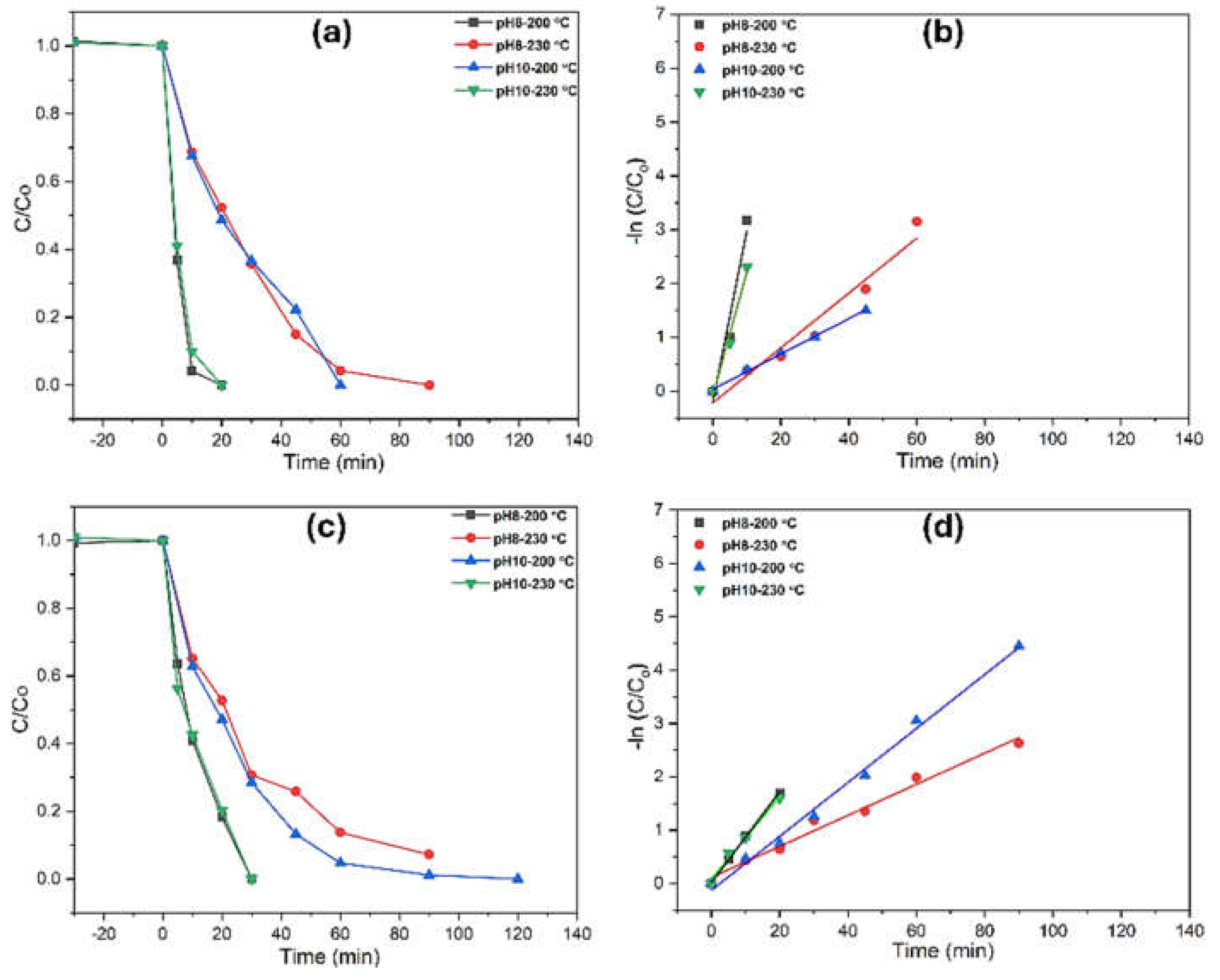

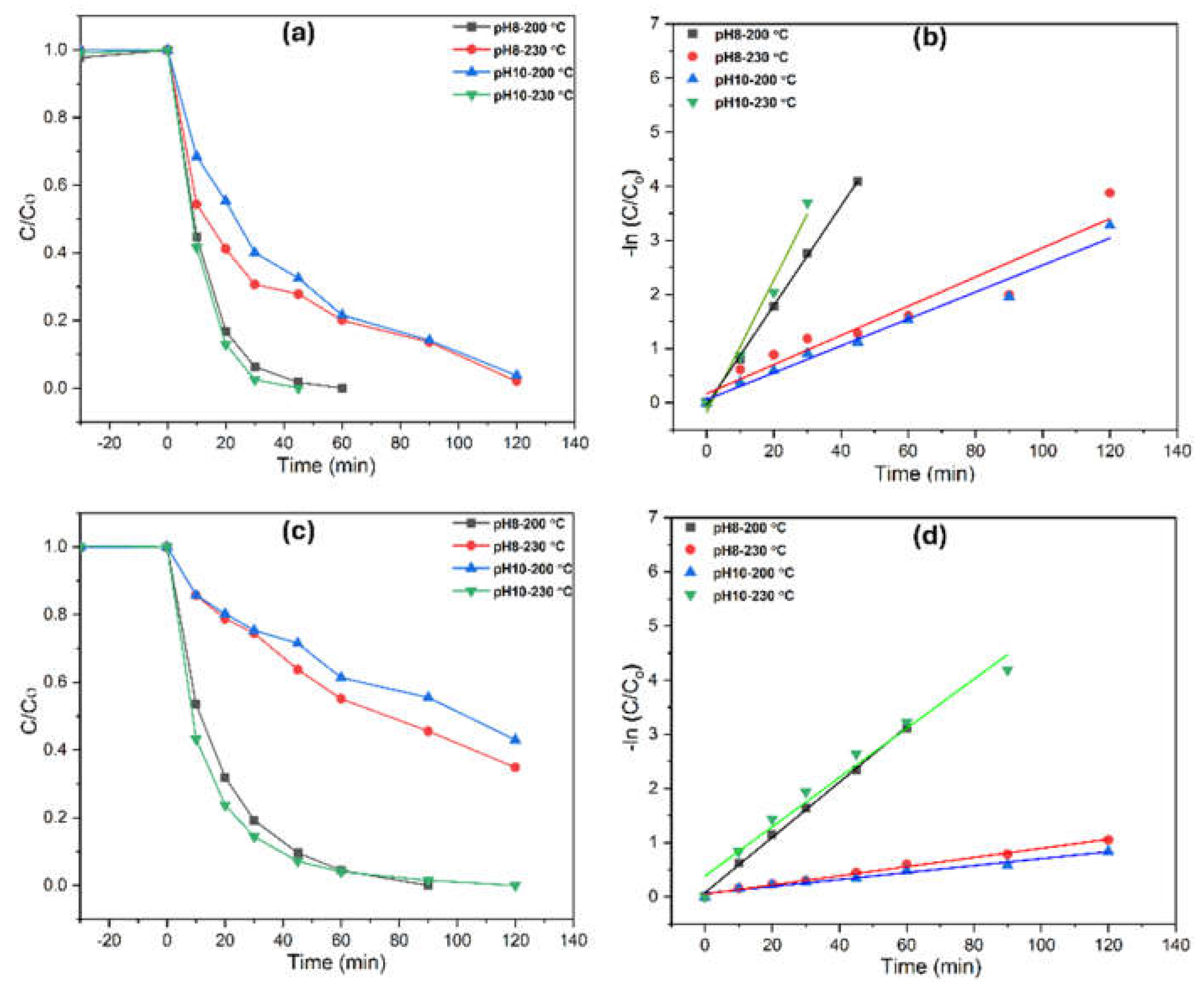

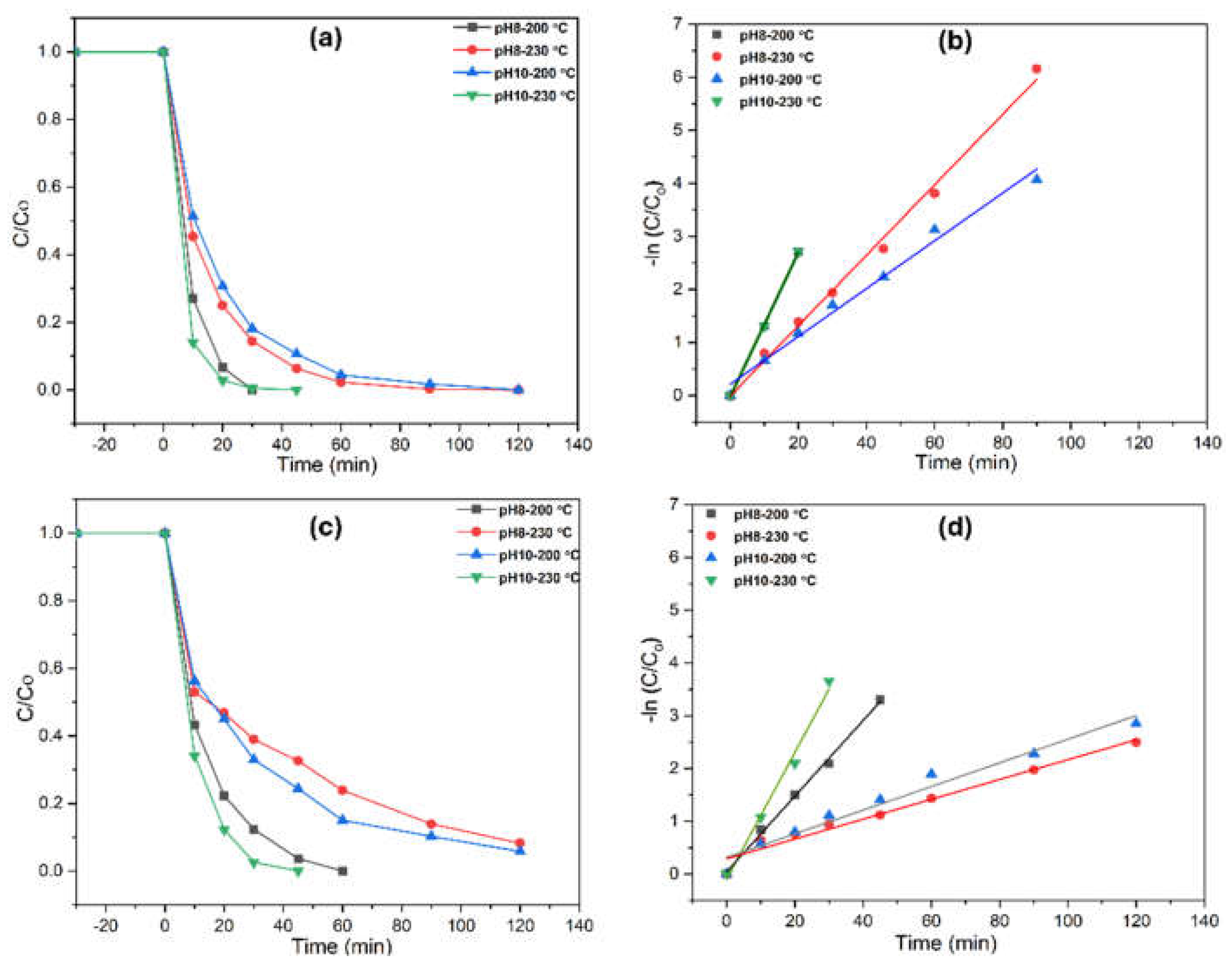

The photocatalytic performance of TiO₂ for aqueous degradation was evaluated in two water matrices—Milli-Q water (UW) and highly basic stormwater (SW)—using a fixed pollutant concentration of 0.1 mM. For phenol degradation, TiO₂ samples synthesized at pH 8 (200°C) and pH 10 (230°C) exhibited significantly higher photocatalytic activity compared to those synthesized at pH 10 (200°C) and pH 8 (230°C), despite being primarily anatase (

Figure 8). Considering the impact of morphology, TiO₂ specimens with nanotubes and mixed nanotubes/elongated bipyramids showed faster degradation rates, achieving nearly complete phenol removal within 20 minutes in UW and full degradation within 30 minutes in SW for pH-8, 200°C and pH-10, 230°C. The higher TOC removal values of 70% (in UW) and 56% (in SW) for pH-10, 230°C indicate more efficient photocatalytic activity. Higher TOC removal is critical as it reflects the extent of organic pollutant degradation, demonstrating the complete mineralization of contaminants into harmless byproducts like carbon dioxide and water. This suggests that the photocatalyst not only reduces the concentration of pollutants but also contributes to their complete breakdown, ensuring cleaner, safer output in environmental applications.

The distinctive photocatalytic performance among anatase-phase samples is attributed to differences in surface morphology. Fully developed, compact nanotubes and bipyramids (with dense populations and finer sizes) exhibited superior degradation efficiency due to their higher surface area, increased active sites, and enhanced generation of reactive hydroxyl radicals. In contrast, brookite-phase samples showed negligible photocatalytic activity across all morphologies. This is likely due to the lower charge mobility and higher electron-hole recombination rates associated with the brookite phase, significantly reducing the formation of reactive species necessary for pollutant degradation. Additionally, brookite’s structural characteristics may hinder its interaction with light, further decreasing its catalytic efficiency under the tested conditions, thus the morphology made no impact on degradation. As a result, brookite samples were excluded from aqueous pollutant degradation studies. Photocatalytic activity in both matrices followed first-order kinetics concerning phenol concentration. First-order rate constants and degradation rates were analyzed using the Langmuir-Hinshelwood model, with results summarized in

Table 2.

Figure 9 illustrates the photodegradation of methomyl using TiO₂ with various morphologies under UV irradiation across different water matrices. Similar to phenol degradation, TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C) and pH 8 (200°C) exhibited notable photocatalytic activity, achieving near-complete methomyl removal in 45 and 60 minutes in Milli-Q water (UW), respectively. In contrast, degradation in rainwater (RW) was slower, requiring 90 and 120 minutes for near-complete removal. This delay is likely due to the additional ions and organic matter in RW, which may compete with methomyl for active sites on the catalyst surface, thereby reducing efficiency. Compared to phenol, the methomyl degradation rate is slower. This is due to the more complex structure of methomyl, which contains multiple functional groups, making it more resistant to photocatalytic degradation. Furthermore, methomyl may form more persistent by-products that are difficult to degrade, which slows down the overall degradation process.

For mineralization, total organic carbon (TOC) conversion was significantly higher in UW than in RW after 120 minutes of UV exposure. Specifically, the TiO₂ samples synthesized at pH 10 (230°C) and pH 8 (200°C) achieved 57% and 46% TOC conversion in UW, respectively, indicating effective mineralization of methomyl into CO₂ and H₂O. However, in RW, mineralization efficiency was lower, with TOC conversions of 41% and 29%, suggesting that the RW matrix promotes the formation of more persistent by-products, which are more challenging to completely mineralize.

Notably, the TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C) exhibited higher TOC conversion than pH 8 (200°C), demonstrating its superior performance in mineralizing methomyl. This can be attributed to the more optimized surface area and active sites of the anatase-phase structure formed at pH 10 (230°C), which enhances both pollutant degradation and mineralization efficiency. The higher TOC conversion observed for the pH 10 (230°C) TiO₂ further emphasizes the importance of tailoring synthesis conditions, such as pH and temperature, to enhance photocatalytic efficiency. Other morphologies, such as those formed under pH 8 (230°C) and pH 10 (200°C), exhibited relatively lower photocatalytic performance, likely due to less optimal surface structures that offer reduced surface area and active sites for degradation.

The apparent first-order rate constants (kₚₑₛₜ) for methomyl degradation in both water matrices are provided in

Table 3, with high r² values (0.9194–0.9996) confirming the suitability of the first-order kinetic model for describing methomyl degradation under both UW and RW conditions.

Figure 10 illustrates the photodegradation of diclofenac (DCF) under UV irradiation in both mili-Q water (UW) and rainwater (RW), revealing a degradation trend similar to that of phenol and methomyl. The degradation rate was significantly higher in UW, with anatase-phase TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C) and pH 8 (200°C) demonstrating the highest photocatalytic efficiency. In UW, nearly complete DCF degradation was achieved within 30 minutes, whereas in RW, TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C) reached full degradation in 45 minutes, and the pH 8 (200°C) sample required 60 minutes.

The mineralization efficiency, measured by TOC conversion, was notably higher in UW than in RW, highlighting the simpler composition of UW, which facilitates more complete breakdown of organic pollutants. Specifically, anatase-phase TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C) achieved up to 78% TOC removal in UW within 120 minutes, compared to 66% in RW. Kinetic analysis using a modified Langmuir-Hinshelwood model confirmed that degradation followed first-order kinetics in both matrices. The first-order rate constants for DCF degradation further underscore the influence of pH-induced phase transitions in TiO₂ (

Table 4). Anatase-phase TiO₂ exhibited superior photocatalytic activity, contributing to more efficient mineralization. The degradation pathway of DCF follows sequential transformations into hydroxy- and dihydroxy-diclofenac derivatives, which then undergo further transformations into chloro- or hydroxyl-phenol intermediates. These intermediates are eventually mineralized through processes like ring opening, ultimately converting into carboxylic acids.

The significant differences in photocatalytic performance among TiO₂ samples can be attributed to the interplay between morphology, phase composition, and the consistently observed anatase phase in the pH 8–10 range. While the anatase phase dominates across all these pH conditions, variations in morphology—such as surface area, population density, and exposed crystal facets—play a critical role in determining photocatalytic efficiency. TiO₂ synthesized at pH 8 (200°C) and pH 10 (230°C) showed superior photocatalytic activity, mainly due to their unique morphologies. The sample synthesized at pH 10 (230°C), which forms nanotubes and mixed nanotubes/elongated bipyramids, has a higher surface area and more accessible active sites, improving interaction with pollutants and boosting degradation efficiency. Similarly, the bipyramidal morphology observed at pH 8 (200°C) exhibited comparable photocatalytic performance, highlighting the importance of morphology even when the crystal phase remains unchanged.

The Total Organic Carbon (TOC) values further reinforce the significance of these morphological variations. Higher TOC removal rates were observed for TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C), indicating more complete mineralization of pollutants into CO₂ and H₂O. This suggests that the optimized surface area and active site accessibility in these morphologies enhance the overall breakdown of organic contaminants. TiO₂ synthesized under other conditions with less favorable morphologies exhibited comparatively lower TOC values, indicating reduced pollutant mineralization efficiency. This limitation is primarily due to their lower capacity for reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and inefficient charge carrier separation, ultimately hindering their overall photocatalytic performance. This is indicative of the crucial role that surface characteristics play in not just the degradation of pollutants but also in their mineralization, which is essential for complete pollutant removal.

These findings underscore the critical synergy between phase composition, morphology, and TOC values in optimizing photocatalytic materials. By controlling not only the crystallographic phase but also the shape and surface characteristics of TiO₂ nanostructures, it becomes possible to enhance photocatalytic efficiency, as demonstrated by TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C), which showed the highest TOC removal and the most efficient degradation of organic pollutants. This material, featuring a nanorod morphology, emerges as an ideal candidate for advanced photocatalytic applications.

4.3. Photocatalytic NOX Abatement

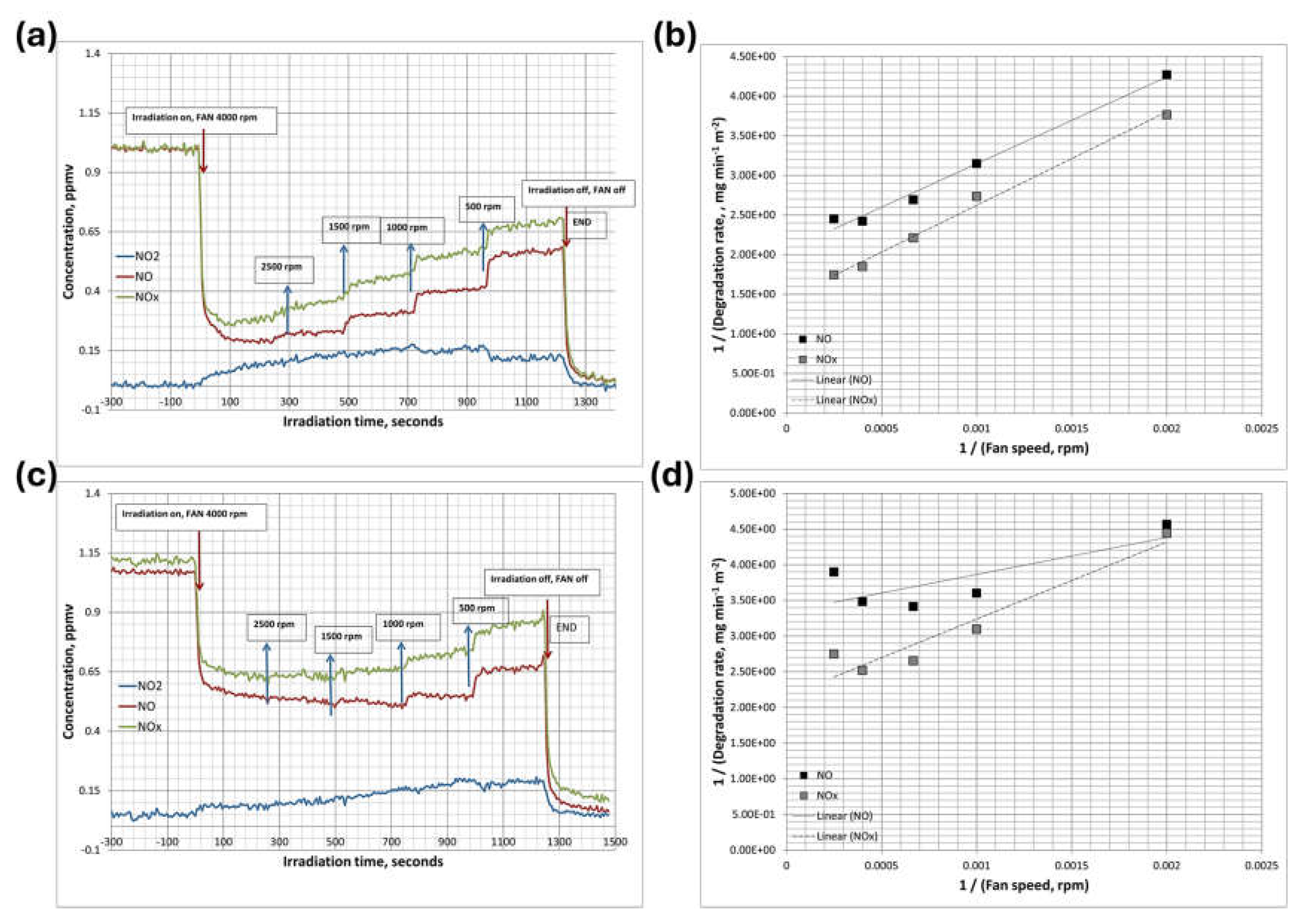

This study systematically investigates the photoconversion of nitrogen oxides (NOx) using TiO₂-based photocatalysts of two distinct phases, anatase and brookite. The impact of varying fan speeds (500–4000 rpm) on boundary layer thickness, mass transfer, and NO photodegradation is thoroughly examined in a custom-designed photoreactor. This approach enables a comparative analysis of the selective phases and morphologies, providing deeper insights into their photocatalytic efficiency and selectivity for NOx abatement (

Figure 11). Higher fan speeds reduce the boundary layer thickness, minimizing mass transfer resistance and allowing for more efficient NO transport to the catalyst surface. This results in accelerated reaction rates and improves overall conversion efficiency.

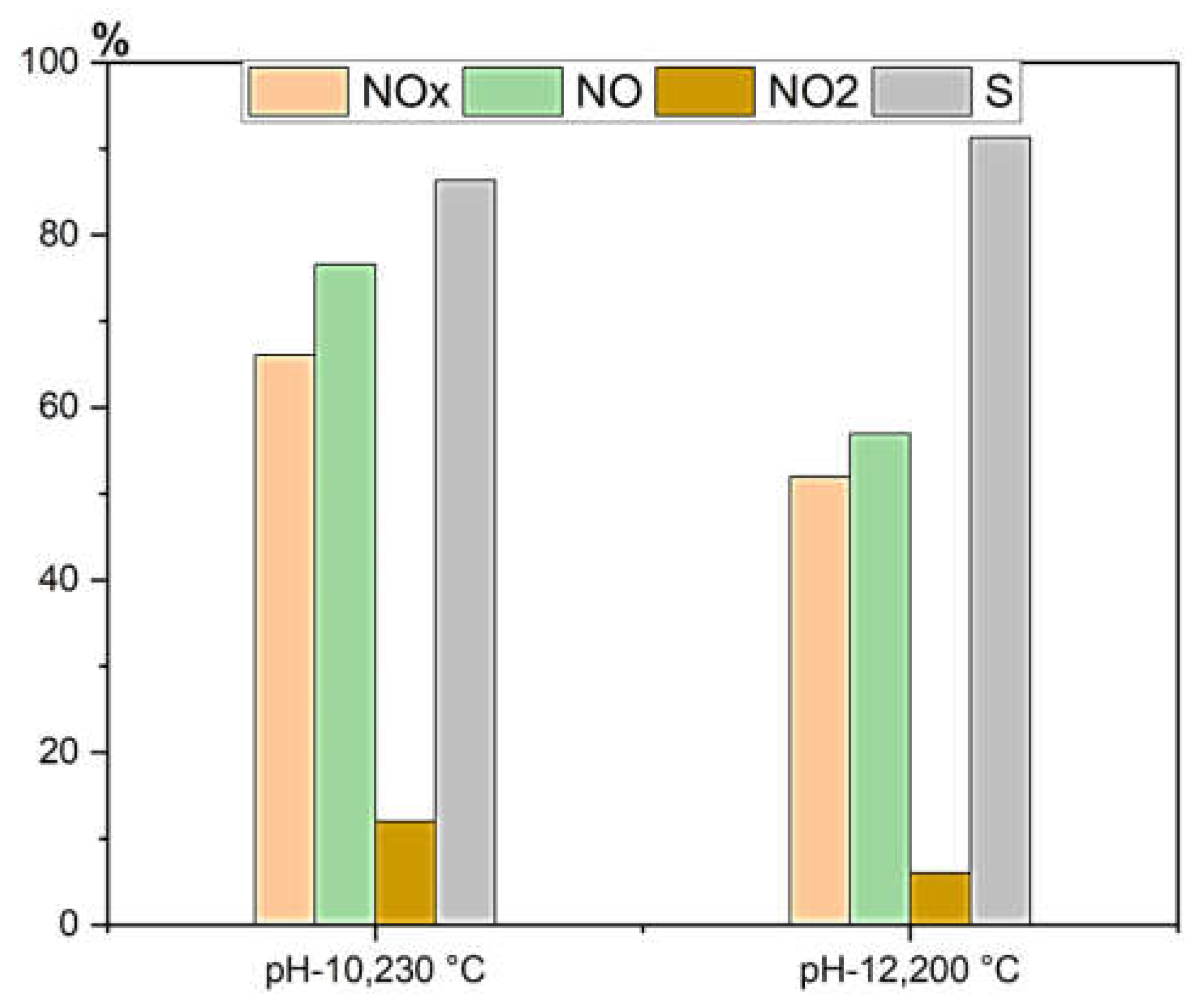

For comparative analysis, TiO₂ synthesized at pH 10 (230°C) was selected due to its superior performance in aqueous pollutant degradation, making it an ideal candidate for evaluating NOx abatement efficiency. Meanwhile, the brookite-based specimen synthesized at pH 12 (200°C) was chosen after initial screening for its distinct response in air pollutant degradation, allowing a systematic comparison of phase-dependent photocatalytic performance. Under LED irradiation at 20 W/m², anatase-phase TiO₂ (pH-10, 230°C) achieved approximately 78% NO conversion efficiency, with degradation rates of 0.427 mg·min⁻¹·m⁻² for NO and 0.578 mg·min⁻¹·m⁻² for NOx. Although anatase-phase TiO₂ demonstrated high NO conversion efficiency, it released more NO₂ (16%) than brookite-phase TiO₂ (pH-12, 200°C), indicating that it is less selective in NOx abatement. This selectivity is a crucial factor in improving urban air quality. Brookite-phase TiO₂ (pH-12, 200°C) demonstrated high NO conversion (~60%) with remarkable selectivity (~91%) and minimal NO₂ release (3–4%), (

Figure 12). This distinctive performance in NOx abatement, despite its comparatively lower efficiency in aqueous pollutant degradation, makes brookite-phase TiO₂ significant for air pollution control. Furthermore, brookite-phase TiO₂ showed a continuous increase in NO degradation efficiency even at decreasing fan speeds down to 100 rpm, after which the reaction rate plateaued. This suggests that at lower fan speeds (100–500 rpm), mass transfer is the limiting factor, while at higher speeds, reaction kinetics dominate. Thus, brookite-phase TiO₂ maintained excellent selectivity towards NOx degradation products and minimized NO₂ formation—an essential characteristic for optimizing deNOx processes in gas-phase applications. The comparison between anatase-phase TiO₂ (pH 10, 230°C) and brookite-phase TiO₂ (pH 12, 200°C) underscores the importance of phase engineering in determining photocatalytic efficiency. Anatase-phase TiO₂ (pH-10, 230°C) excelled in aqueous pollutant degradation, while brookite-phase TiO₂ demonstrated superior selectivity in NOx abatement, achieving higher selectivity and lower NO₂ release. This highlights the critical role of phase and morphology in optimizing TiO₂-based photocatalysts for different environmental applications.

In summary, this study emphasizes the significance of phase-engineered TiO₂ in photocatalytic applications, with anatase-phase TiO₂ excelling in aqueous pollutant degradation and brookite-phase TiO₂ performing remarkably well in NOx abatement. The interplay between morphology, crystallographic phase, and mass transfer dynamics is crucial for optimizing photocatalytic performance, and the results further emphasize the importance of selecting the appropriate phase and morphology for targeted environmental applications, particularly for air pollution control.