Submitted:

12 October 2024

Posted:

14 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Synthesis of ZnO Nanocrystals

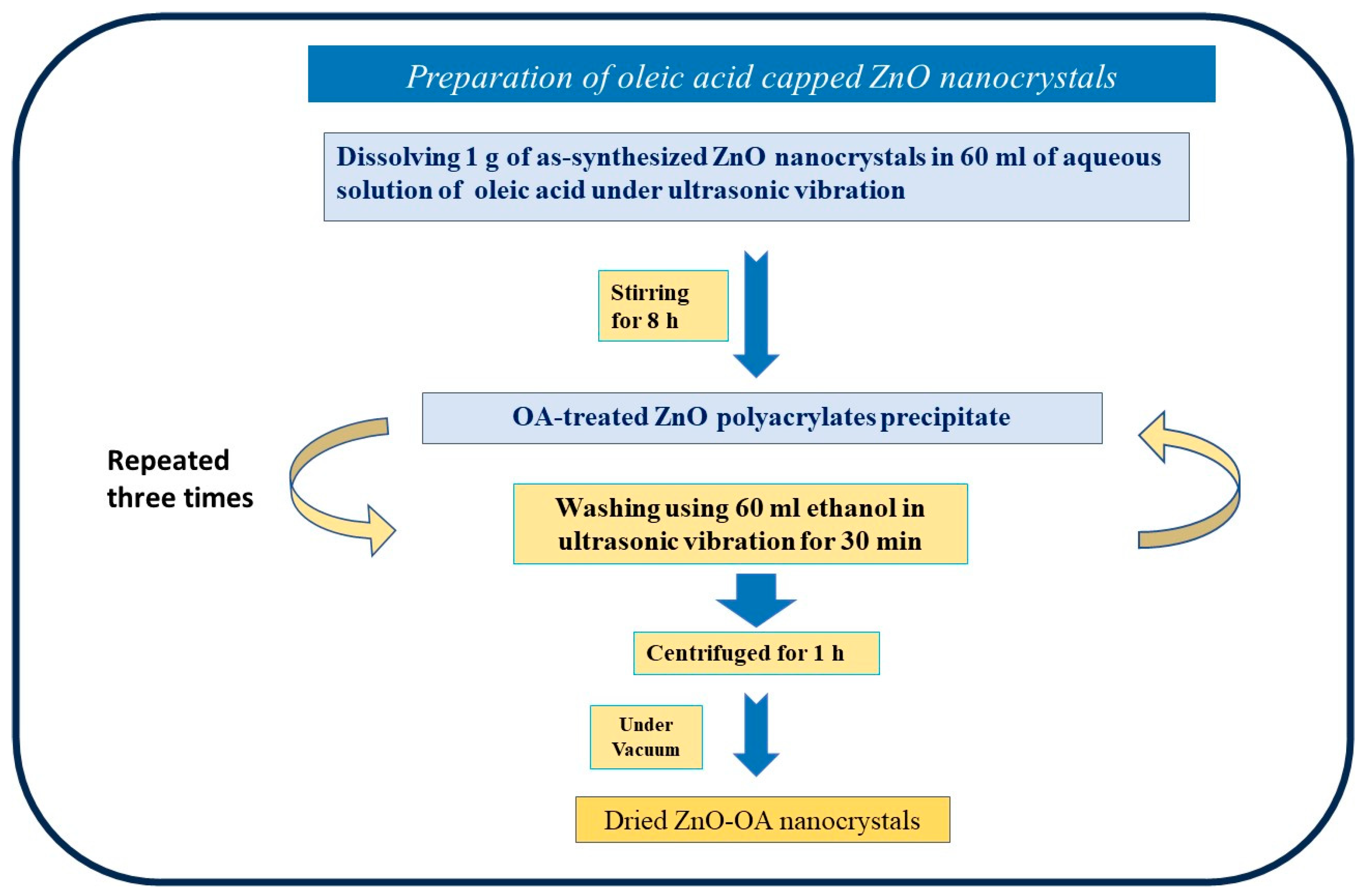

2.2. Capping ZnO Nanocrystals with Oleic Acid (OA)

2.3. Bench Scale Set-Up

2.4. Analytical Determination

2.5. Characterization Techniques for as-Synthesized ZnO and ZnO-OA Nanocrystals

3. Results and Discussions

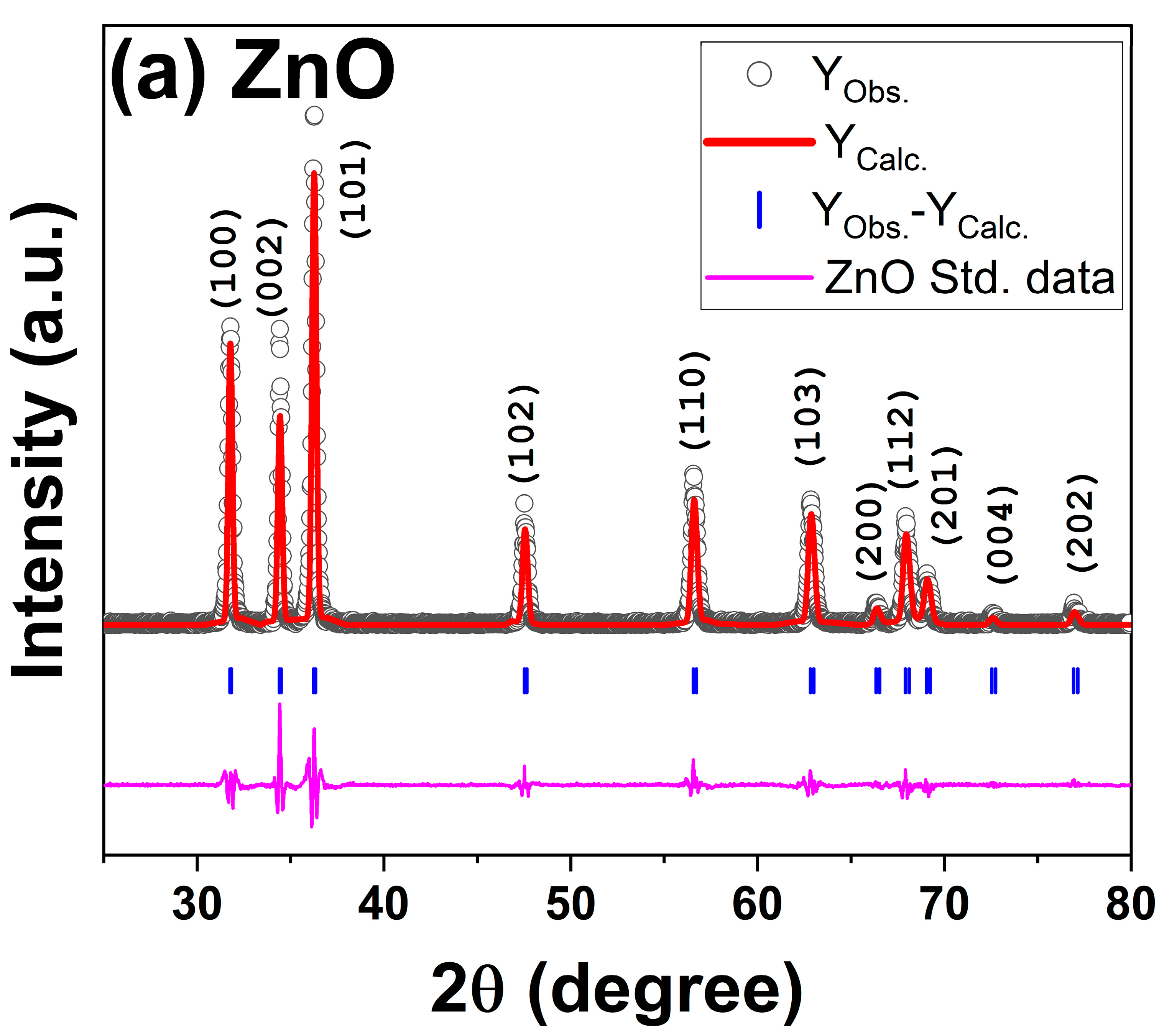

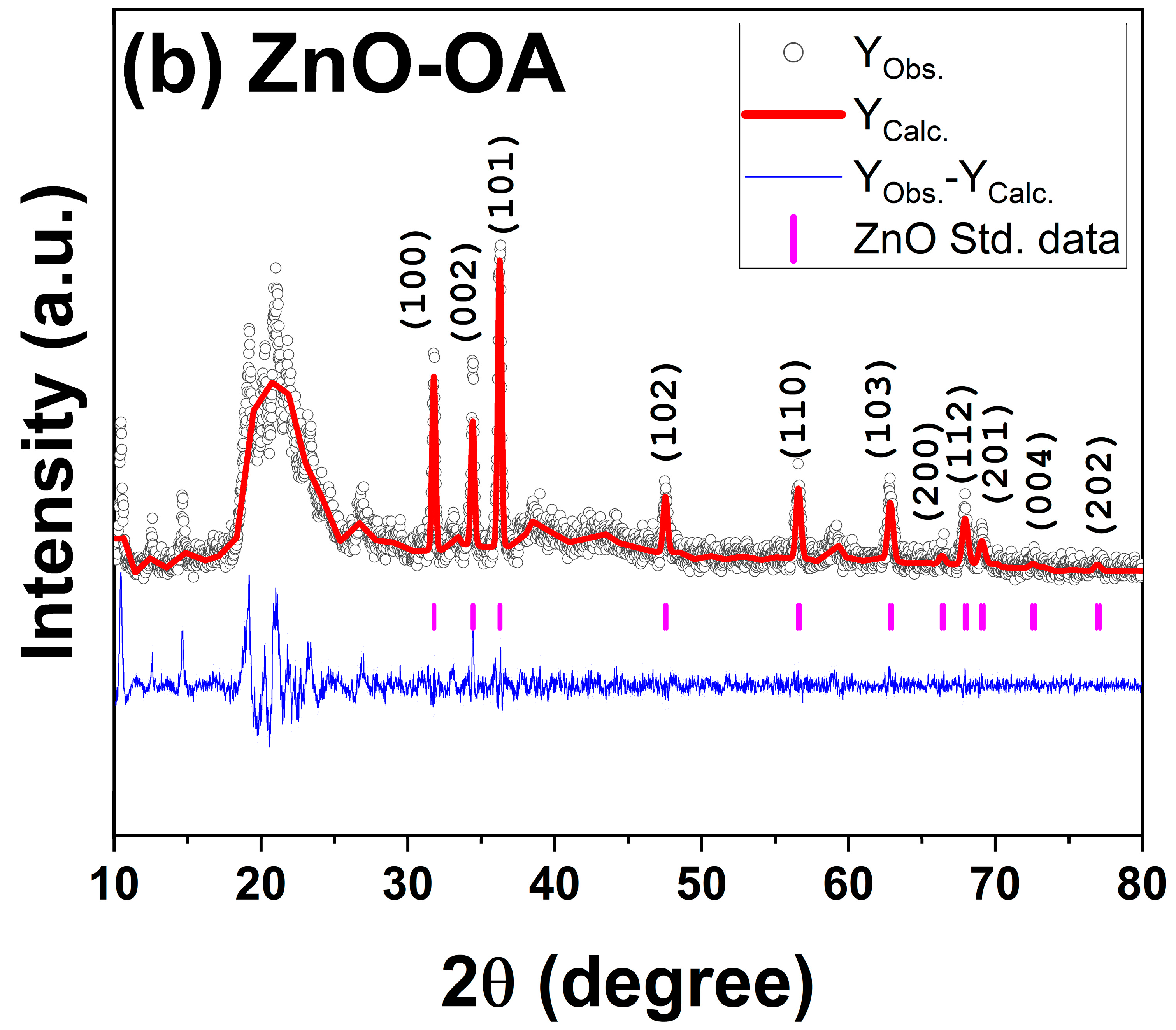

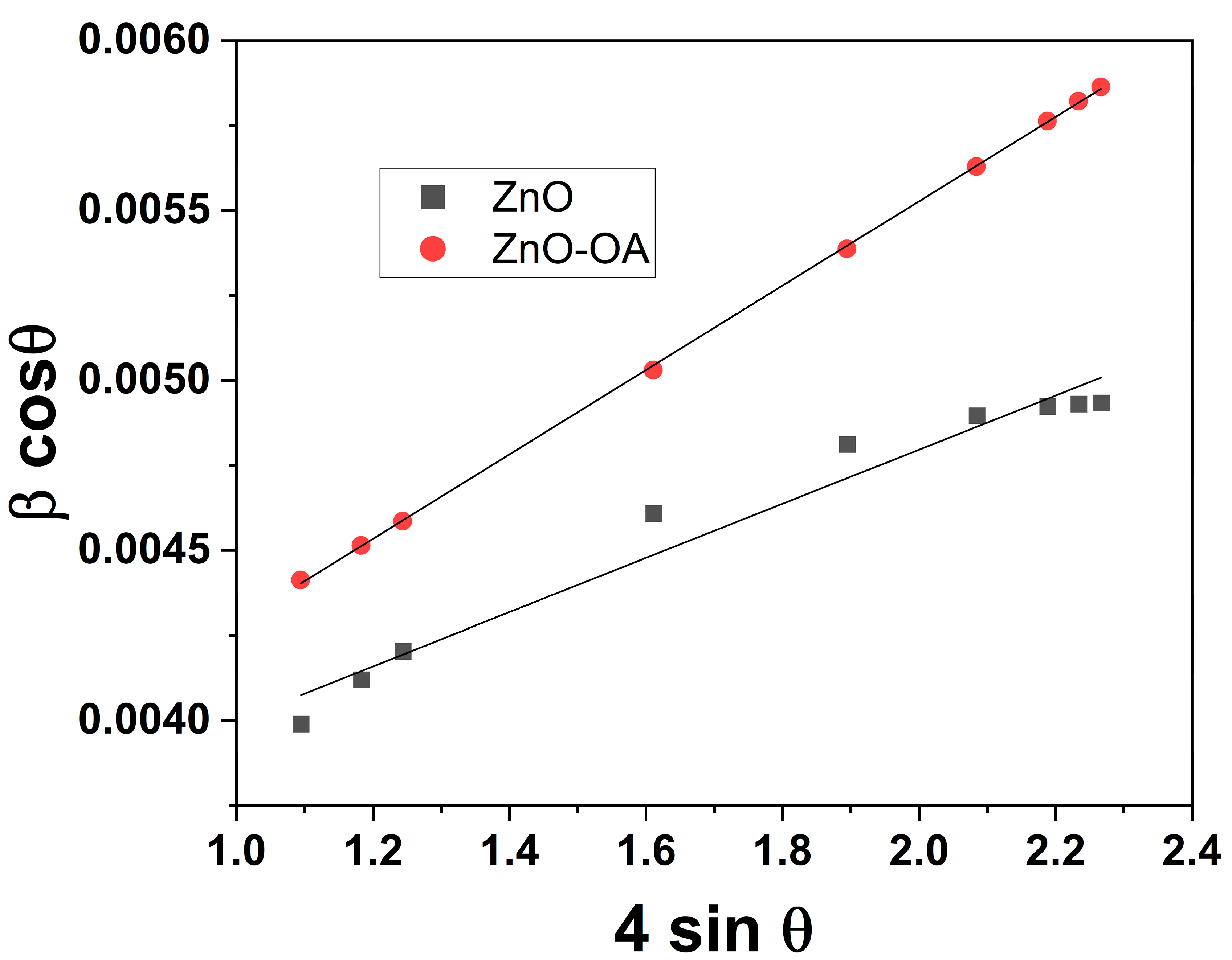

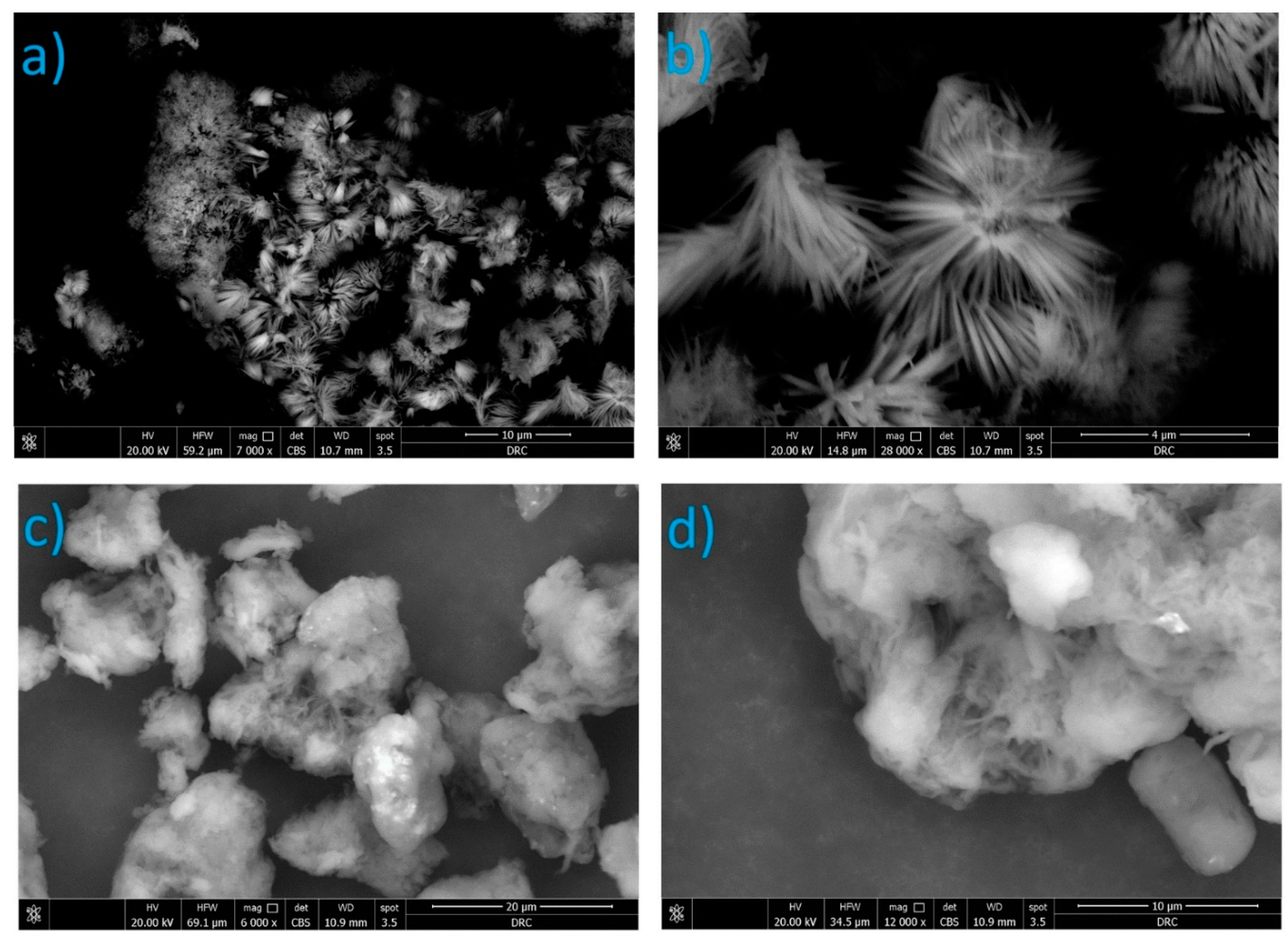

3.1. Structural and Morphological Characterization of as-Synthesized ZnO and OA-ZnO

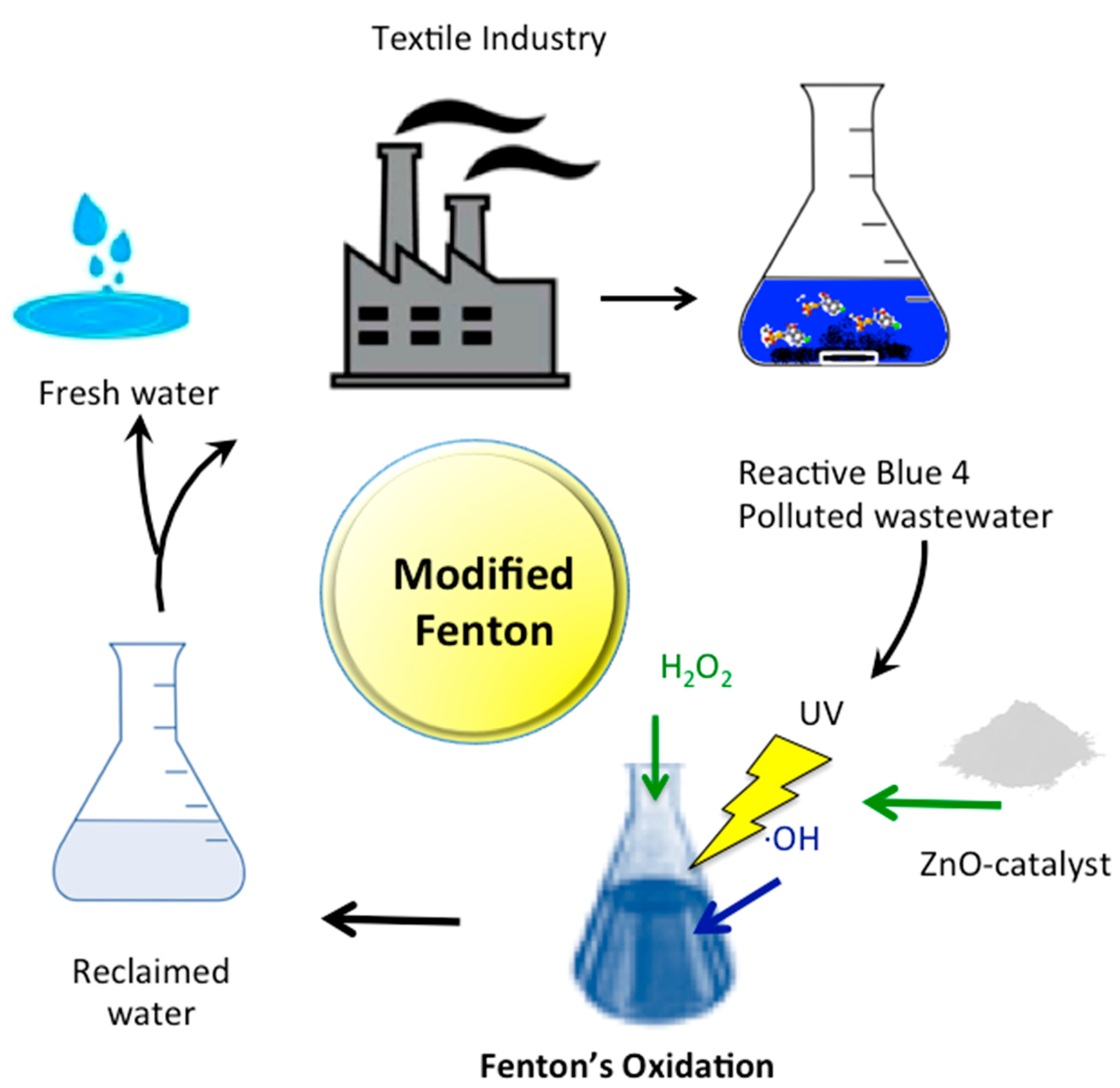

3.2. Studies on RB4 Dye Oxidation

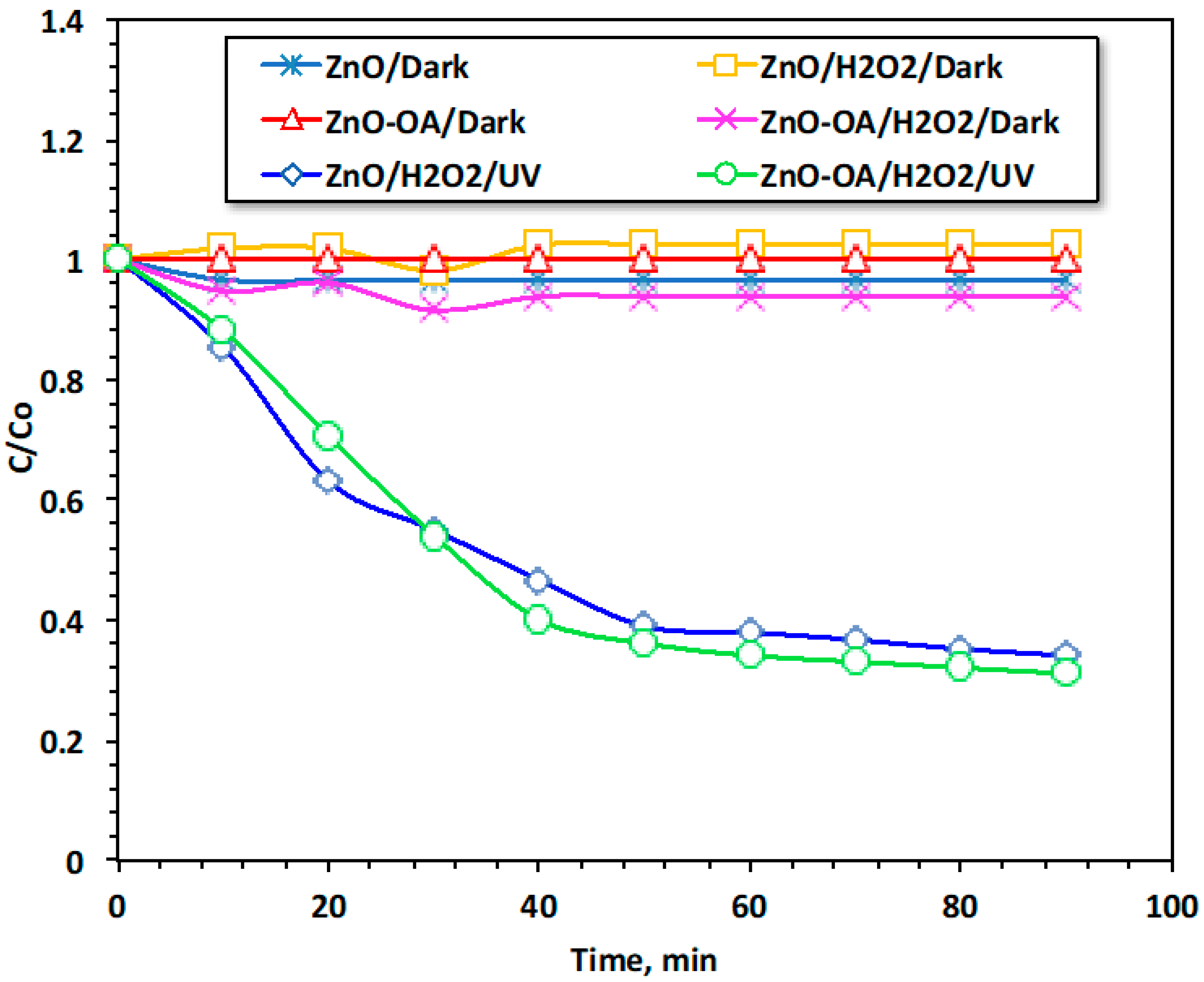

3.2.1. RB4 Dye Oxidation Related to Contact Time between Different Oxidation Systems

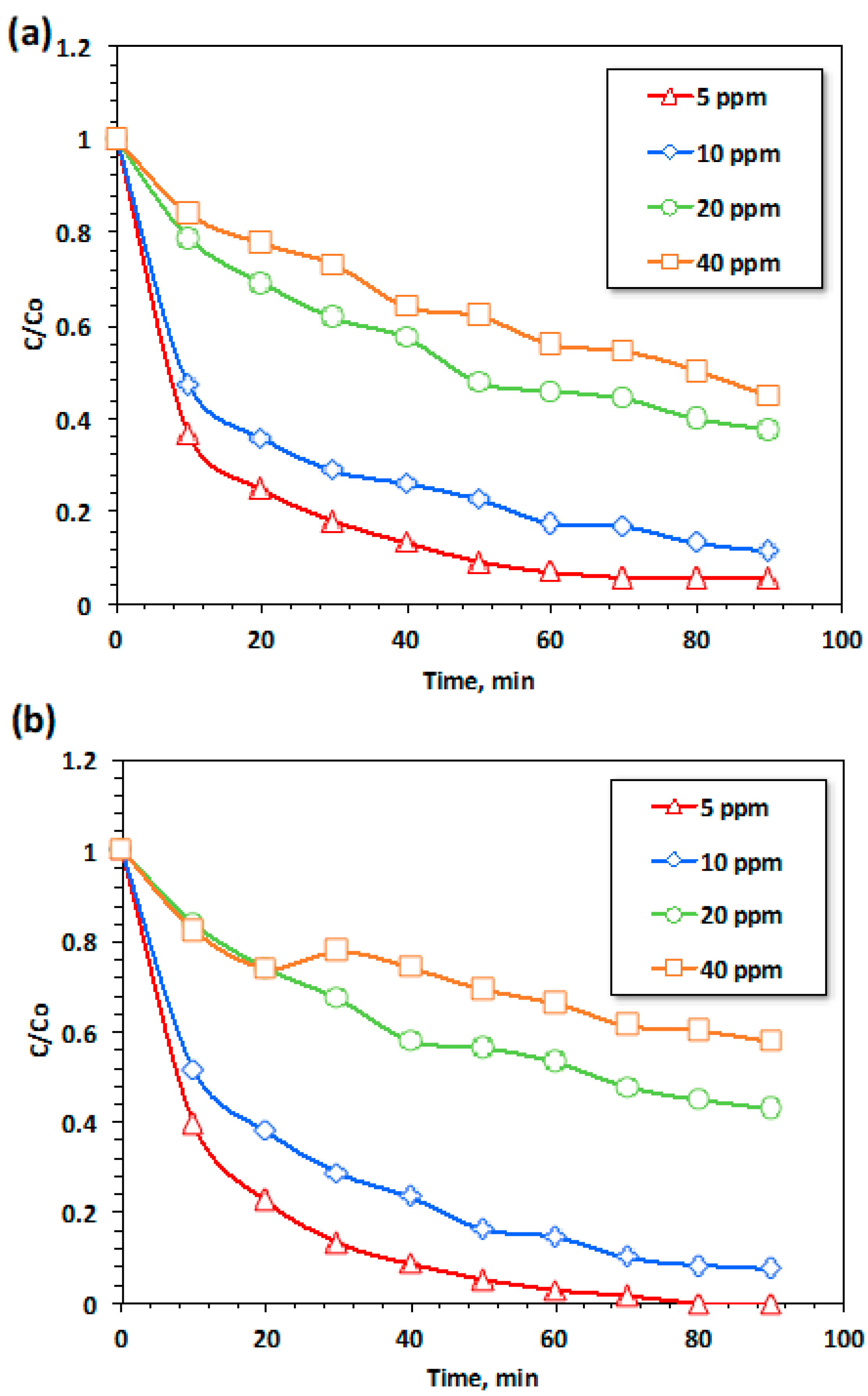

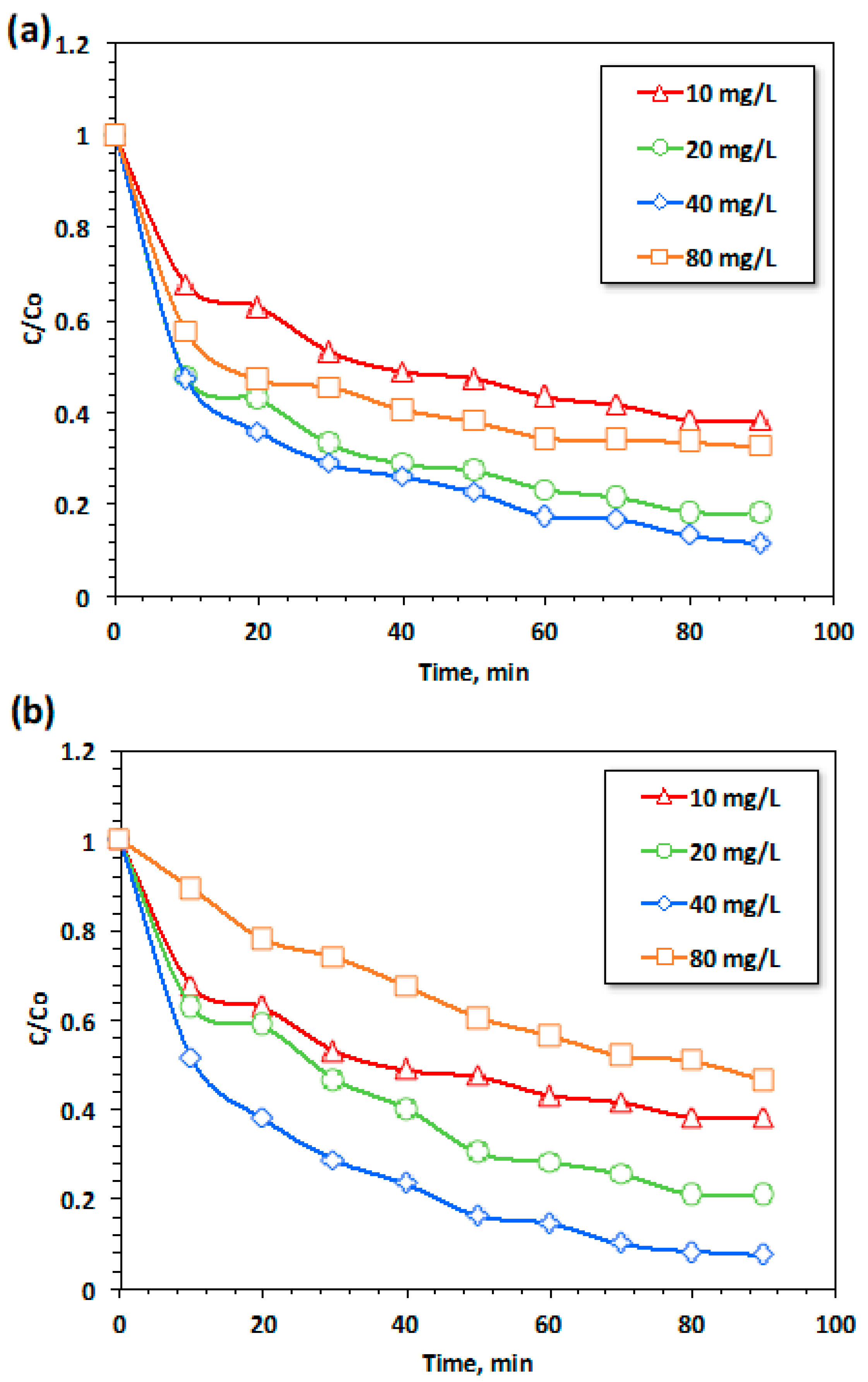

3.2.2. Effect of Initial RB4 Loading on Oxidation System

3.2.3. The Effect of Different Fenton Parameters on Oxidation Behavior

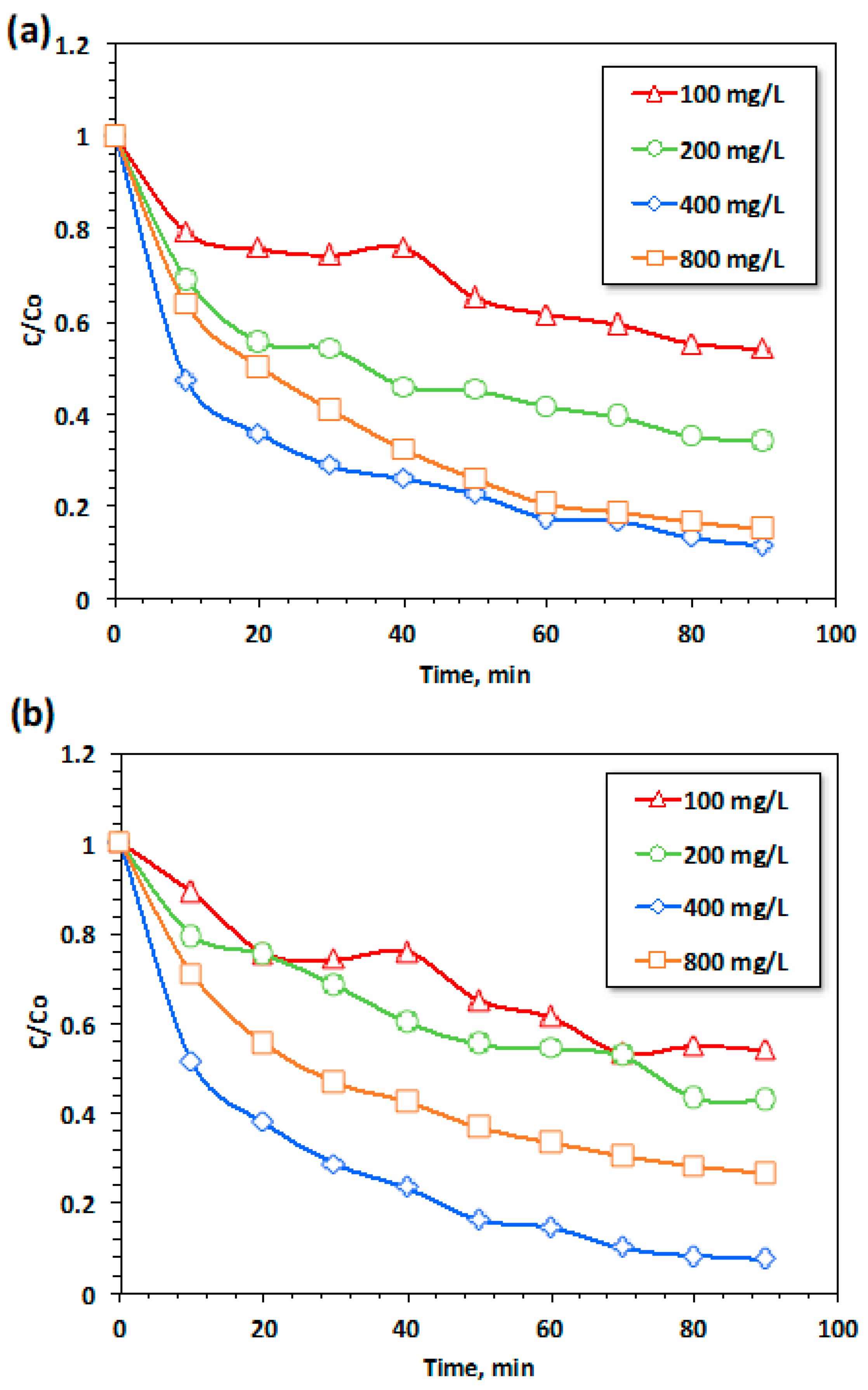

3.2.3.1. Effect of ZnO and ZnO-OA Dosing

3.2.3.2. Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide

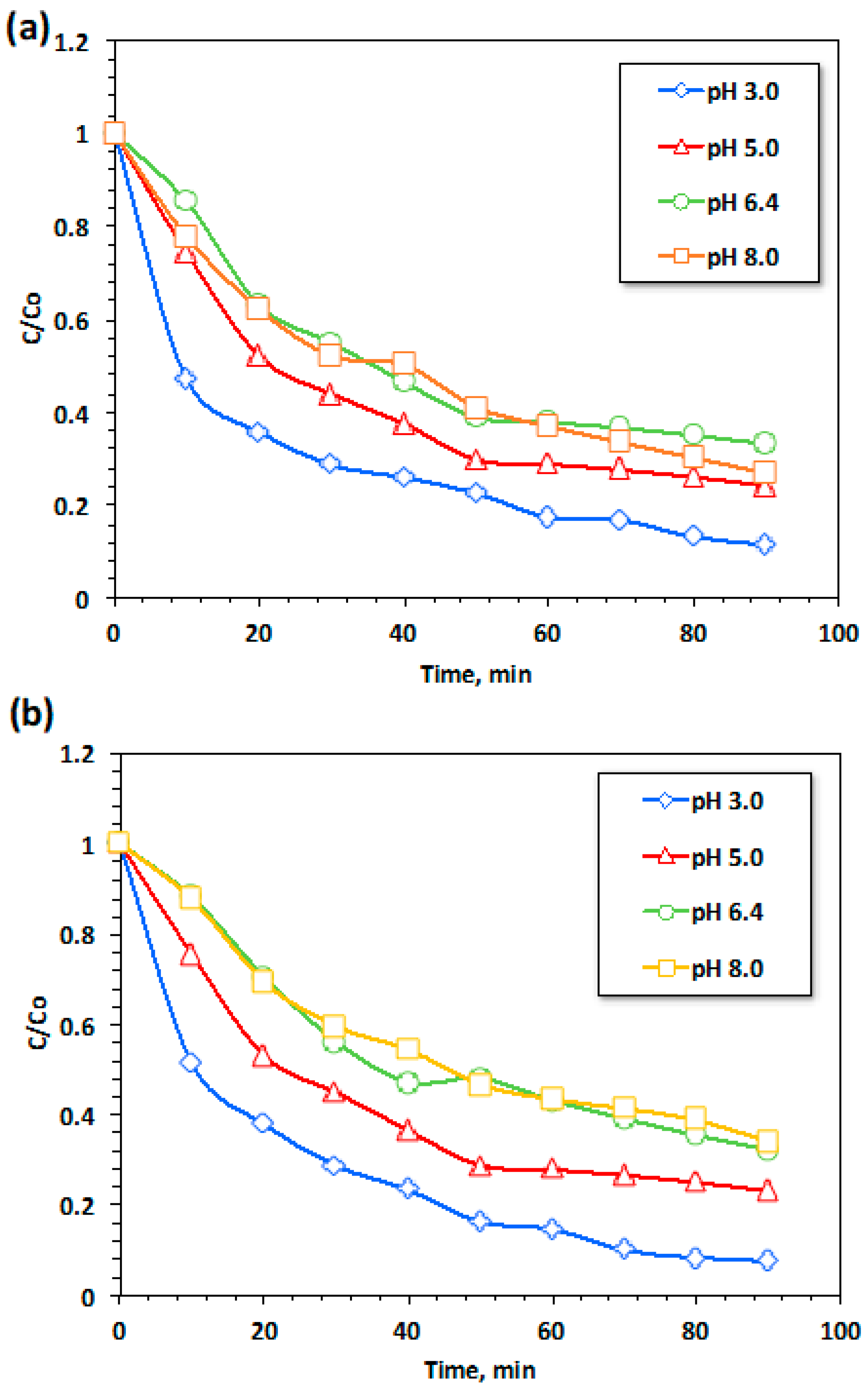

3.2.3.3. Effect of pH

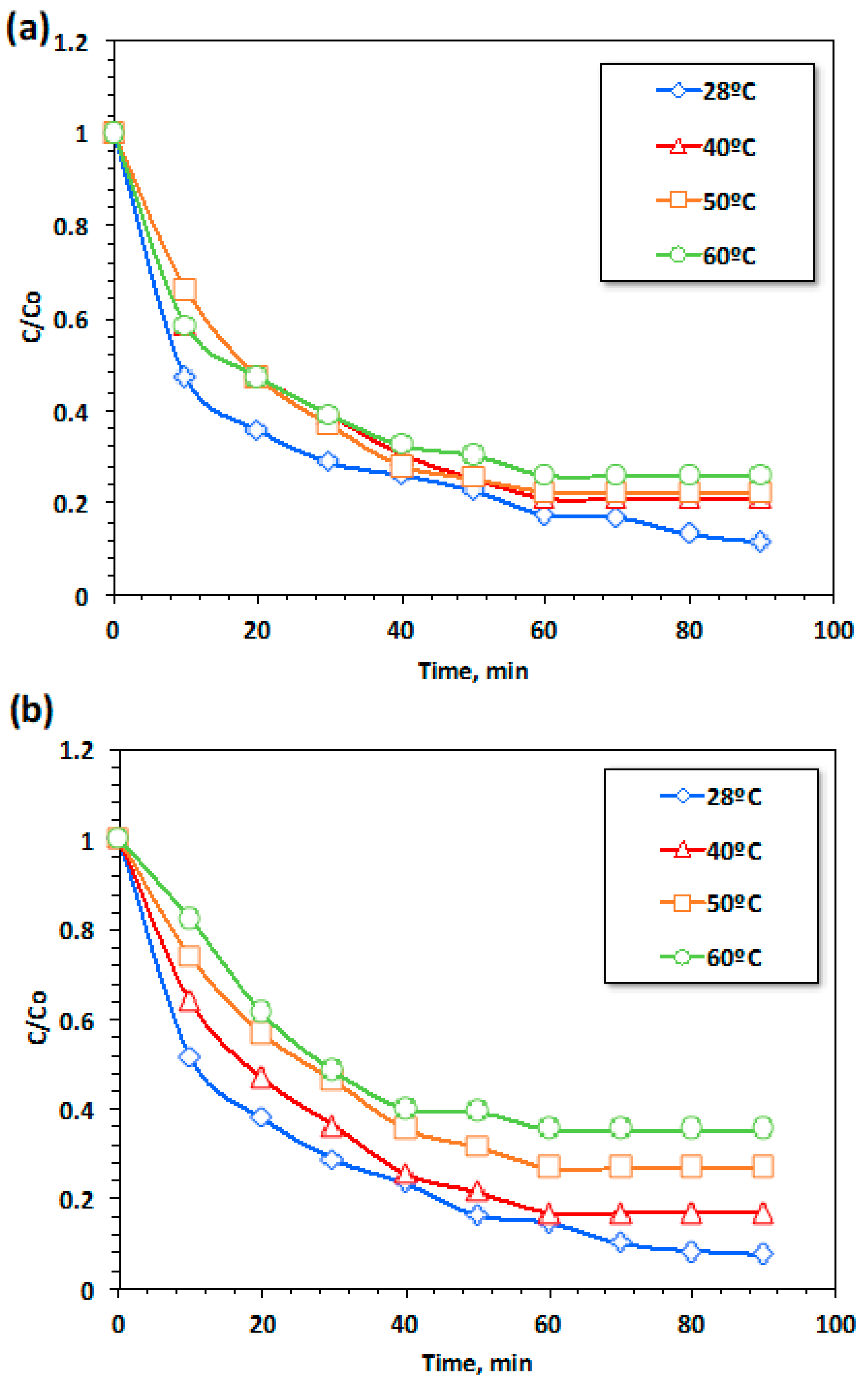

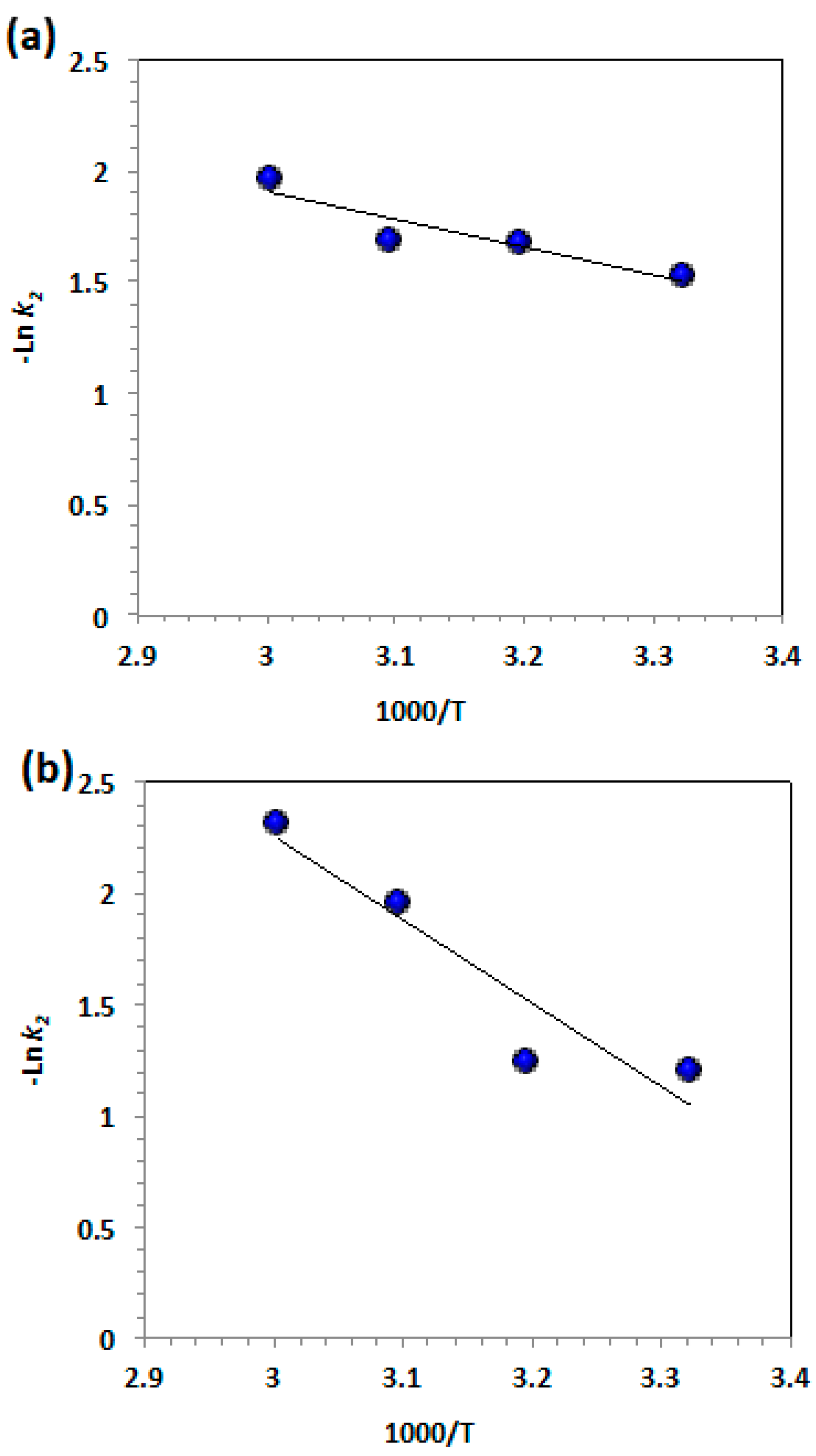

3.2.4. Temperature Effects on Kinetics and Thermodynamic Variables

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Shamberger, P. J.; Bruno, N. M. , Review of metallic phase change materials for high heat flux transient thermal management applications. Applied Energy 2020, 258, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; ai, Y.; Jin, J.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Zhuang, L.; Wang, X. , Efficient elimination of organic and inorganic pollutants by biochar and biochar-based materials. Biochar 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Alharbi, N.; Rabah, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. , Synthesis and fabrication of g-C3N4-based materials and their application in elimination of pollutants. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 731, 139054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnago, R.; Berselli, D.; Medeiros, P. , Treatment of wastewater from car wash by fenton and photo-fenton oxidative processes. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 2018, 13, 838–850. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Sharma, R. K.; Goyal, R.; Hekimoğlu, G.; Sarı, A.; Rathore, P. K. S.; Tyagi, V. V. , Development and characterization a novel leakage-proof form stable composite of graphitic carbon nitride and fatty alcohol for thermal energy storage. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthami, D.; Sharma, R. K.; Ansu, A. K.; Sarı, A.; Tyagi, V. V.; Rathore, P. K. S. , Evaluation of carbonized cotton stalk for development of novel form stable composite phase change materials for solar thermal energy storage. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2024, 188, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D. K.; Rathore, P. K. S.; Singh, R. K.; Gupta, A. K.; Sikarwar, B. S. , Experimental Study on Paraffin Wax and Soya Wax Supported by High-Density Polyethylene and Loaded with Nano-Additives for Thermal Energy Storage. Energies 2024, 17, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poormand, H.; Leili, M.; Khazaei, M. , Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solutions using water treatment sludge modified with sodium alginate as a low cost adsorbent. Water Science and Technology 2016, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Liang, F.; Ruan, H.; Wu, F.; Huang, Q.; Xu, C. L.; Kong, C. , Effect of zinc acetate concentration on the structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films deposited by Sol-Gel method. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2012, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. C.; Swamy, M. M.; Mall, I. D.; Prasad, B.; Mishra, I. M. , Adsorptive removal of phenol by bagasse fly ash and activated carbon: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2006, 272, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markandeya, n.; Shukla Sheo, P.; Dhiman, N.; Mohan, D.; Kisku Ganesh, C.; Roy, S. , An Efficient Removal of Disperse Dye from Wastewater Using Zeolite Synthesized from Cenospheres. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste 2017, 21, 04017017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S. A.; El-Sayed, I. E. T.; Tony, M. A. , Impregnated chitin biopolymer with magnetic nanoparticles to immobilize dye from aqueous media as a simple, rapid and efficient composite photocatalyst. Applied Water Science 2022, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhula, M.; Okonkwo, O.; Zvinowanda, C., Fixed bed column adsorption of Cu(II) onto maize Tassel-PVA beads. Journal of Chemical Engineering & Process Technology 2012, 03.

- Deng, D.; Lin, O.; Rubenstein, A.; Weidhaas, J.; Lin, L.-S. , Elucidating biochemical transformations of Fe and S in an innovative Fe(II)-dosed anaerobic wastewater treatment process using spectroscopic and phylogenetic analyses. The Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 358, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argun, M. E.; Karatas, M. , Application of Fenton process for decolorization of reactive black 5 from synthetic wastewater: Kinetics and thermodynamics. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy 2011, 30, 540–548. [Google Scholar]

- Dubber, D.; Gray, N. , Replacement of chemical oxygen demand (COD) with total organic carbon (TOC) for monitoring wastewater treatment performance to minimize disposal of toxic analytical waste. Journal of environmental science and health. Part A, Toxic/hazardous substances & environmental engineering 2010, 45, 1595–600. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, J. A.; Tebbutt, T. H. Y. , Significance of COD, BOD and TOC correlations in kinetic models of biological oxidation. Water Research 1980, 14, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintor, A. M. A.; Vilar, V. J. P.; Boaventura, R. A. R. , Decontamination of cork wastewaters by solar-photo-Fenton process using cork bleaching wastewater as H2O2 source. Solar Energy 2011, 85, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, L. A.; Fatta-Kassinos, D. , Solar photo-Fenton oxidation against the bioresistant fractions of winery wastewater. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2013, 1, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounab, L.; Iglesias, O.; González-Romero, E.; Pazos, M.; Ángeles Sanromán, M. , Effective heterogeneous electro-Fenton process of m-cresol with iron loaded actived carbon. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 31049–31056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buthiyappan, A.; Abdul Raman, A. A.; Daud, W. M. A. W. , Development of an advanced chemical oxidation wastewater treatment system for the batik industry in Malaysia. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 25222–25241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, P.; Mohedano, A. F.; Casas, J. A.; Zazo, J. A.; Rodriguez, J. J. , An overview of the application of Fenton oxidation to industrial wastewaters treatment. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2008, 83, 1323–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Miao, J.; Zou, L. , Fenton Reagent Oxidation and Decolorizing Reaction Kinetics of Reactive Red SBE. Energy Procedia 2012, 16, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, B.; Palmer, A.; Jeffrey, P.; Stuetz, R.; Judd, S. , Grey water characterisation and its impact on the selection and operation of technologies for urban reuse. Water Science and Technology 2004, 50, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Deng, L. , Efficient decolorization of dye pollutants with LiFe(WO4)2 as a reusable heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst. Desalination 2011, 269, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradu, C.; Frunza, L.; Mihalche, N.; Avramescu, S.-M.; Neaţă, M.; Udrea, I. , Removal of Reactive Black 5 azo dye from aqueous solutions by catalytic oxidation using CuO/Al2O3 and NiO/Al2O3. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2010, 96, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. G.; Devi, L. G. , Review on Modified TiO2 Photocatalysis under UV/Visible Light: Selected Results and Related Mechanisms on Interfacial Charge Carrier Transfer Dynamics. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2011, 115, 13211–13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaneti, R. N.; Etchepare, R.; Rubio, J. , Car wash wastewater treatment and water reuse – a case study. Water Science and Technology 2013, 67, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwapwa, J. K.; Jaiyeola, A. T.; Chetty, R. , Bioremediation of acid mine drainage using algae strains: A review. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering 2017, 24, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Lin, L.-S. , Continuous sulfidogenic wastewater treatment with iron sulfide sludge oxidation and recycle. Water Research 2017, 114, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Guzman, P.; Giannakis, S.; Rtimi, S.; Grandjean, D.; Bensimon, M.; de Alencastro, L.; Torres-Palma, R.; Pulgarin, C. , A green solar photo-Fenton process for the elimination of bacteria and micropollutants in municipal wastewater treatment using mineral iron and natural organic acids. Applied Catalysis B Environmental 2017, 219, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhang, H.; Han, L.; Mei, J.; Ge, Q.; Long, Z.; Yu, Y. , Exploring bacterial communities and biodegradation genes in activated sludge from pesticide wastewater treatment plants via metagenomic analysis. Environmental Pollution 2018, 243, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A. K.; Srivastava, O. N.; Singh, K. , Shape and Size-Dependent Magnetic Properties of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Piperidine. Nanoscale Research Letters 2017, 12, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Khan, S. B.; Kamal, T.; Alamry, K. A.; Asiri, A. M.; Sobahi, T. R. A. , Chitosan coated cotton cloth supported zero-valent nanoparticles: Simple but economically viable, efficient and easily retrievable catalysts. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 16957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Garg, V. K.; Kataria, N.; Kadirvelu, K. , Applications of Fe3O4@AC nanoparticles for dye removal from simulated wastewater. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Mishra, S. B.; Sheng, L. , An easily applicable and recyclable Fenton-like catalyst produced without wastewater emission and its performance evaluation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 234, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnasas, A.; Karavasilis, M. V.; Aggelopoulos, C.; Poulopoulos, P. , Growth and Characterization of Nanostructured Ag-ZnO for Application in Water Purification. Trans Tech Publications 2020, 62, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, A. H.; Al Naim, A. F.; Mansour, S. A. , Cost-Effective and Efficient Cool Nanopigments Based on Oleic-Acid-Surface-Modified ZnO Nanostructured. Materials 2023, 16, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Li, Y.-Y. , Synthesis of ZnO nanowires by thermal decomposition of zinc acetate dihydrate. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2009, 113, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkallas, F. H.; Elshokrofy, K. M.; Mansour, S. A. , Structural and Diffuse Reflectance Study of Cr-Doped ZnO Nanorod-Pigments Prepared via Facile Thermal Decomposition Technique. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials 2019, 29, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Su, Z. , Preparation and Characterization of PMMA/ZnO Nanocomposites via In-Situ Polymerization Method. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 2006, 45, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S. A.; Farha, A. H.; Tahoun, B. A.; Elsad, R. A. , Novel magnetic polyaniline nanocomposites based on as-synthesized and surface modified Co-doped ZnO diluted magnetic oxide (DMO) nanoparticles. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2021, 265, 115032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mote, V.; Purushotham, Y.; Dole, B. , Williamson-Hall analysis in estimation of lattice strain in nanometer-sized ZnO particles. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Physics 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R.; Pan, T.; Qian, J.; Li, H. , Synthesis and surface modification of ZnO nanoparticles. Chemical Engineering Journal 2006, 119, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, M. A.; Mansour, S. A. , Synthesis of nanosized amorphous and nanocrystalline TiO2 for photochemical oxidation of methomyl insecticide in aqueous media. Water and Environment Journal 2020, 24(S1), 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Q.; Keogh, C.; Tony, M. A. , On the necessity of sludge conditioning with non-organic polymer: AOP approach. Journal of Residuals Science & Technology 2009, 6, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tony, M. A.; Lin, L.-S. , Iron Coated-Sand from Acid Mine Drainage Waste for Being a Catalytic Oxidant Towards Municipal Wastewater Remediation. International Journal of Environmental Research 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, M. A.; Purcell, P. J.; Zhao, Y.; Tayeb, A. M.; El-Sherbiny, M. F., Kinetic modeling of diesel oil wastewater degradation using photo-Fenton process. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal (EEMJ) 2015, 14, (1).

- Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Ban, Y.; Ren, B. , A comparative study of UV–Fenton, UV–H2O2 and Fenton reaction treatment of landfill leachate. Environmental technology 2011, 32, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primo, O.; Rueda, A.; Rivero, M. J.; Ortiz, I. , An integrated process, Fenton reaction− ultrafiltration, for the treatment of landfill leachate: pilot plant operation and analysis. Industrial & engineering chemistry research 2008, 47, 946–952. [Google Scholar]

- Hamd, W.; Dutta, J., Heterogeneous photo-Fenton reaction and its enhancement upon addition of chelating agents. 2020; pp 303-330.

- Abdollahzadeh, H.; Fazlzadeh, M.; Afshin, S.; Arfaeinia, H.; Feizizadeh, A.; Poureshgh, Y.; Rashtbari, Y. , Efficiency of activated carbon prepared from scrap tires magnetized by Fe3O4 nanoparticles: characterisation and its application for removal of reactive blue19 from aquatic solutions. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2022, 102, 1911–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, M. A.; Ali, I. A. , Mechanistic implications of redox cycles solar reactions of recyclable layered double hydroxides nanoparticles for remazol brilliant abatement. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 19, 9843–9860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, W.; Chirchi, L.; Santos, E.; Ghorhel*, A. , Kinetic study of 2-nitrophenol photodegradation on Al-pillared montmorillonite doped with copper. Journal of Environmental Monitoring 2001, 3, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tony, M. A.; Lin, L.-S. , Performance of acid mine drainage sludge as an innovative catalytic oxidation source for treating vehicle-washing wastewater. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2021, 43, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crystallite Size, nm | Microstrain (ε) | a, Å | c, Å | Cell Volume, (Å)-3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | 43.3 | 0.0008 | 3.2513 | 5.2085 | 47.681 |

| ZnO-OA | 46.2 | 0.0012 | 3.2524 | 5.2112 | 47.741 |

| T, °C | Zero-order reaction kinetics | First-order reaction kinetics | Second-order reaction kinetics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k0, | R2 | t1/2, min | k1, | R2 | t1/2, min | k2, | R2 | t1/2, min | |||

| min-1 | min-1 | L/mg.min | |||||||||

| ZnO based Fenton system | |||||||||||

| 28 °C | 0.0036 | 0.69 | 45.13 | 0.0251 | 0.9 | 33.804 | 0.218 | 0.97 | 14.11 | ||

| 40 °C | 0.0037 | 0.83 | 43.91 | 0.24 | 0.97 | 2.783 | 0.187 | 0.98 | 16.45 | ||

| 50 °C | 0.0039 | 0.84 | 41.66 | 0.249 | 0.96 | 2.88 | 0.185 | 0.99 | 16.63 | ||

| 60 °C | 0.0034 | 0.78 | 47.79 | 0.0205 | 0.92 | 27.61 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 21.97 | ||

| ZnO-OA based Fenton system | |||||||||||

| 28 °C | 0.0039 | 0.77 | 41.66 | 0.0304 | 0.95 | 38.5 | 0.3005 | 0.98 | 10.23 | ||

| 40 °C | 0.0035 | 0.89 | 46.42 | 0.0289 | 0.98 | 31.78 | 0.289 | 0.97 | 10.64 | ||

| 50 °C | 0.0038 | 0.9 | 42.76 | 0.0218 | 0.98 | 23.9 | 0.1409 | 0.99 | 21.83 | ||

| 60 °C | 0.0035 | 0.88 | 46.42 | 0.018 | 0.94 | 22.79 | 0.0988 | 0.97 | 31.14 | ||

| T, °C | Ln k1 | Ea, | ∆ Gº, | ∆Hº, | ∆Sº, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kJ/mol | kJ/mol | kJ/mol | J/mol | ||

| ZnO based Fenton system | |||||

| 28 °C | -1.52 | 10.38 | 77.55 | 7.88 | -231.46 |

| 40 °C | -1.67 | 81.15 | 7.78 | -234.38 | |

| 50 °C | -1.68 | 83.85 | 7.70 | -235.76 | |

| 60 °C | -1.96 | 87.30 | 7.61 | -239.29 | |

| ZnO-OA based Fenton system | |||||

| 28 °C | -1.20 | 31.38 | 76.75 | 28.88 | -159.03 |

| 40 °C | -1.24 | 80.01 | 28.78 | -163.68 | |

| 50 °C | -1.95 | 84.58 | 28.69 | -173.02 | |

| 60 °C | -2.31 | 88.26 | 28.61 | -179.15 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).