Submitted:

04 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Apparatus

2.3. Synthesis of ZnO-Coated Biochar

2.4. Electrochemical Degradation

3. Results and Discussions

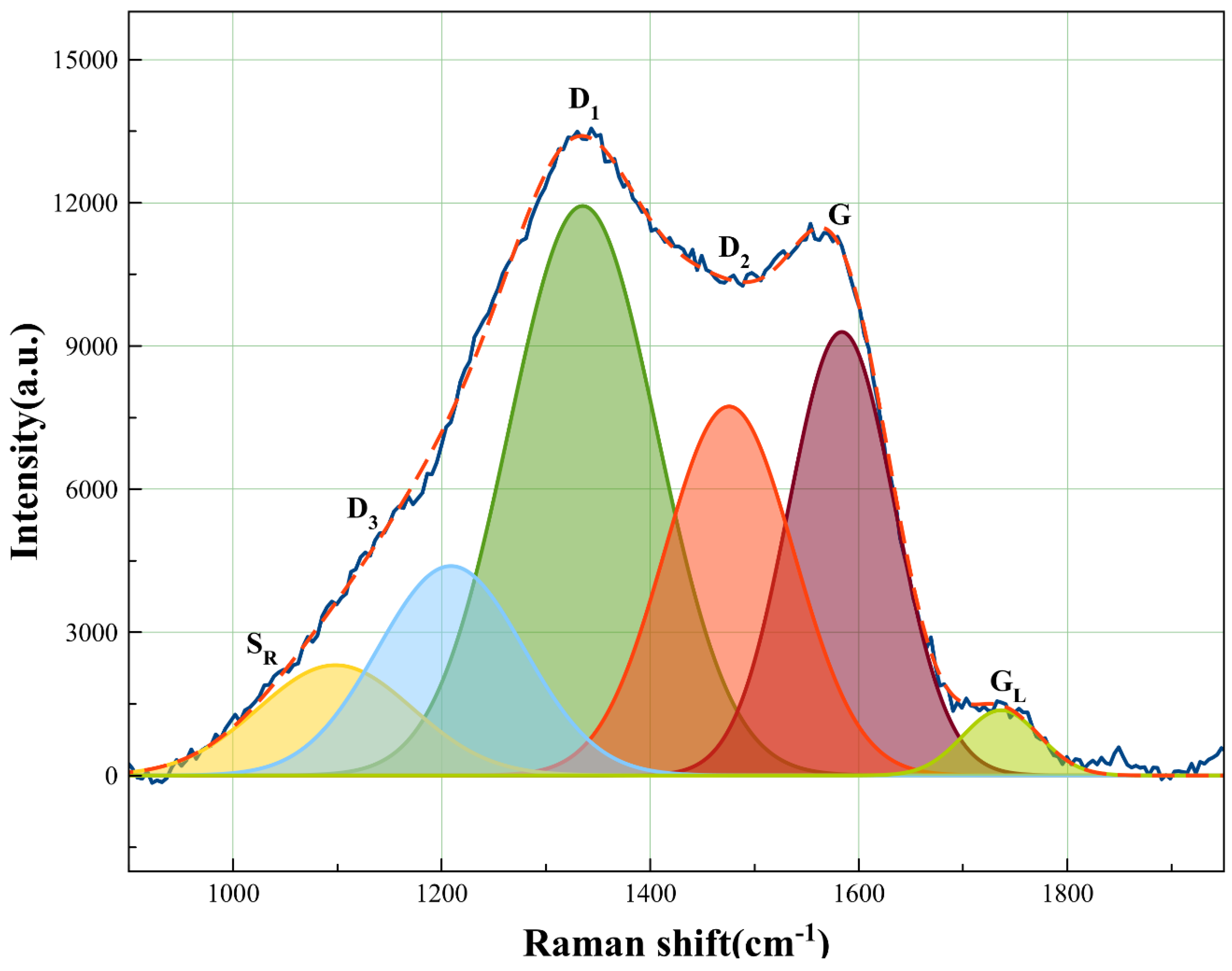

3.1. ZnO Modified Biochar Characterizations

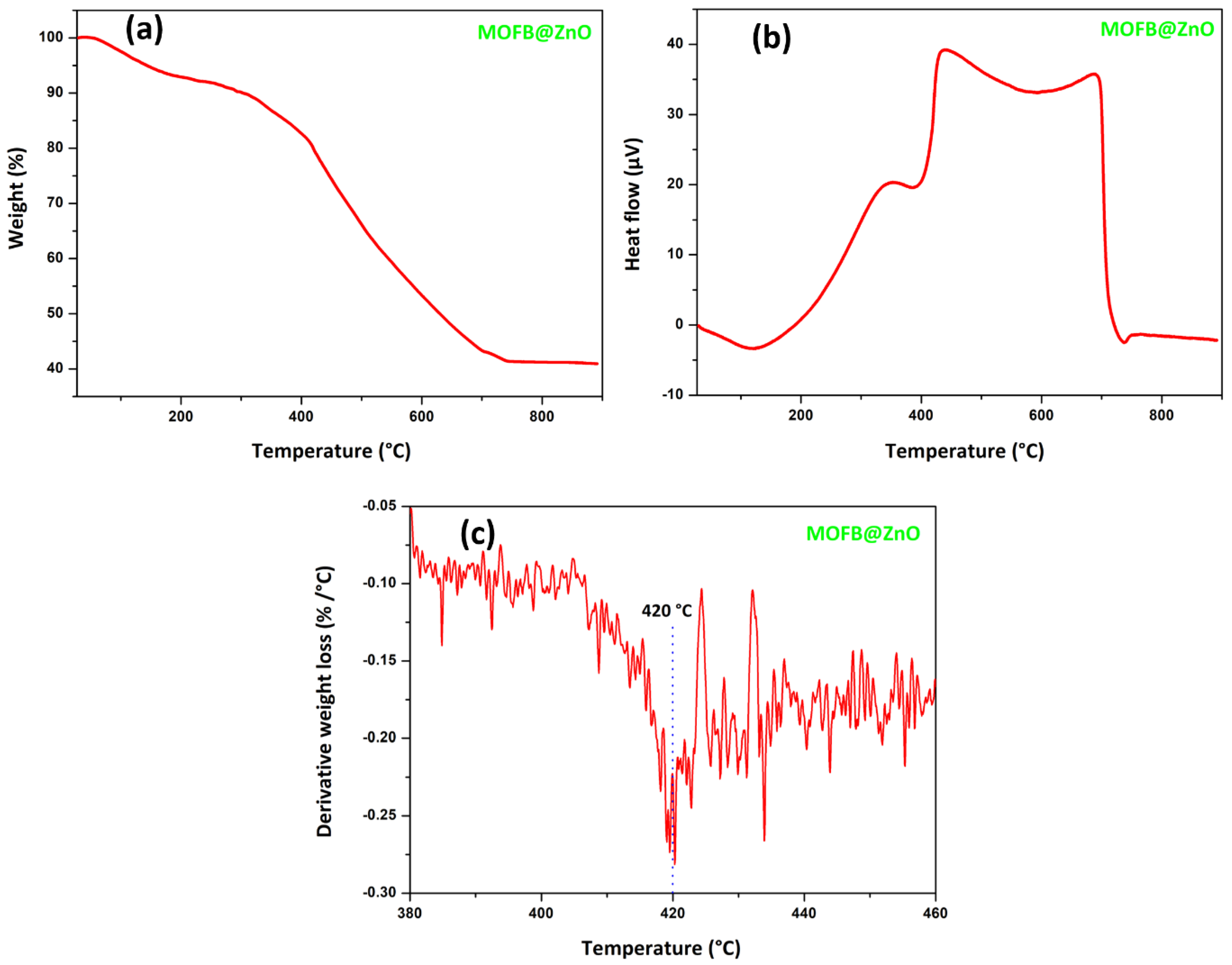

3.2. Thermal Analysis

3.3. Electrochemical Degradation of Congo Red

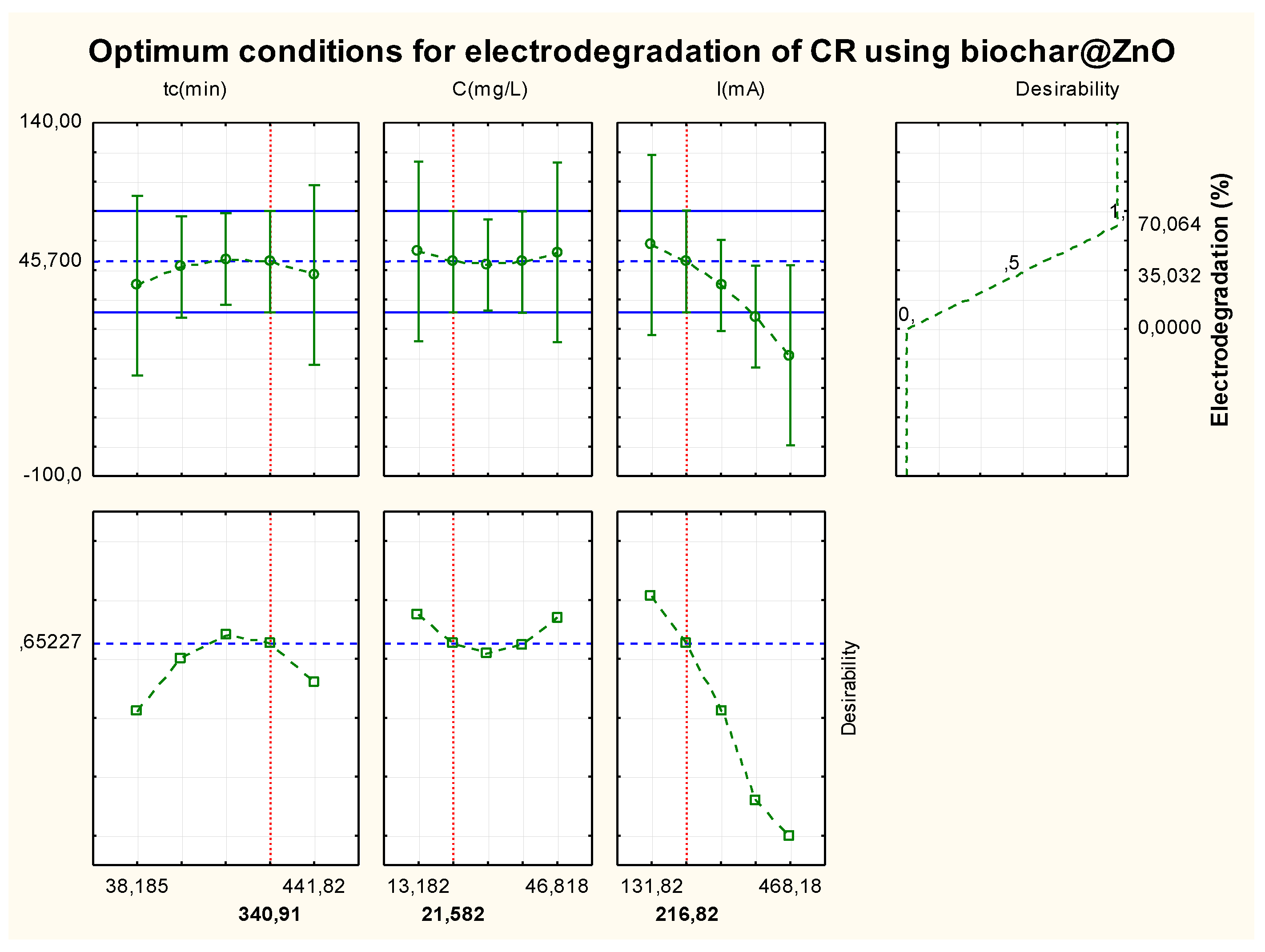

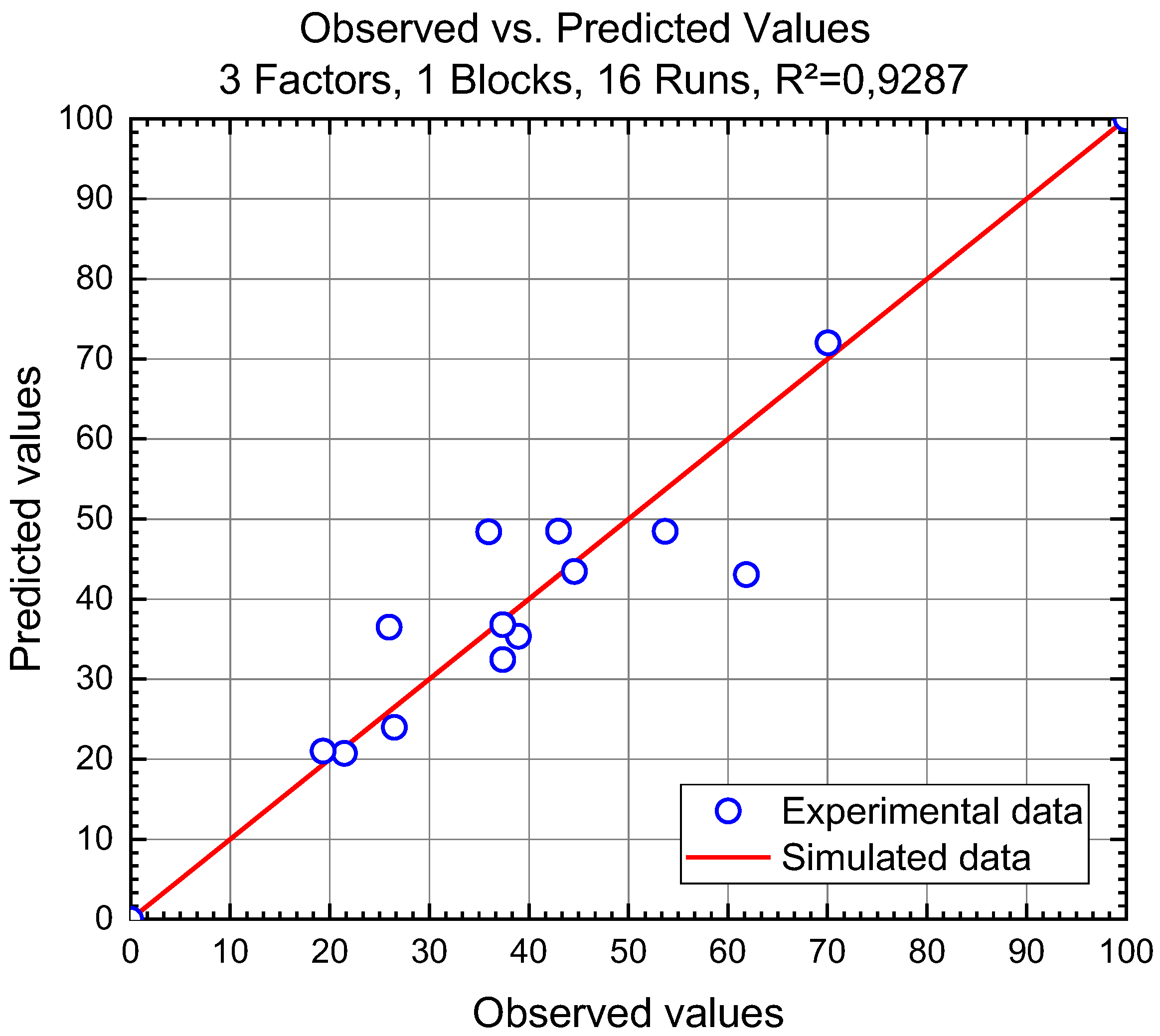

3.3.1. Optimization and Prediction

3.3.2. Kinetic Study

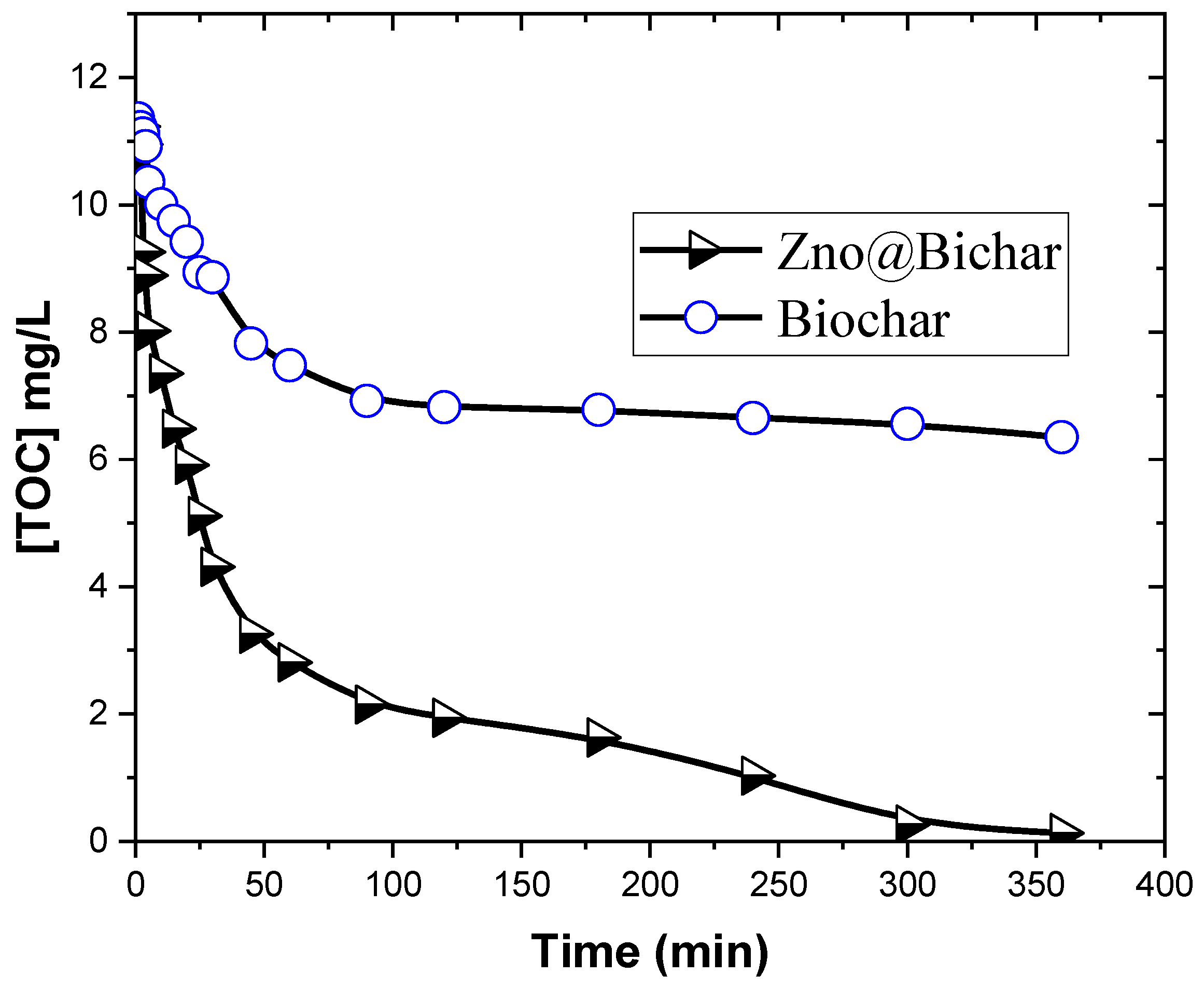

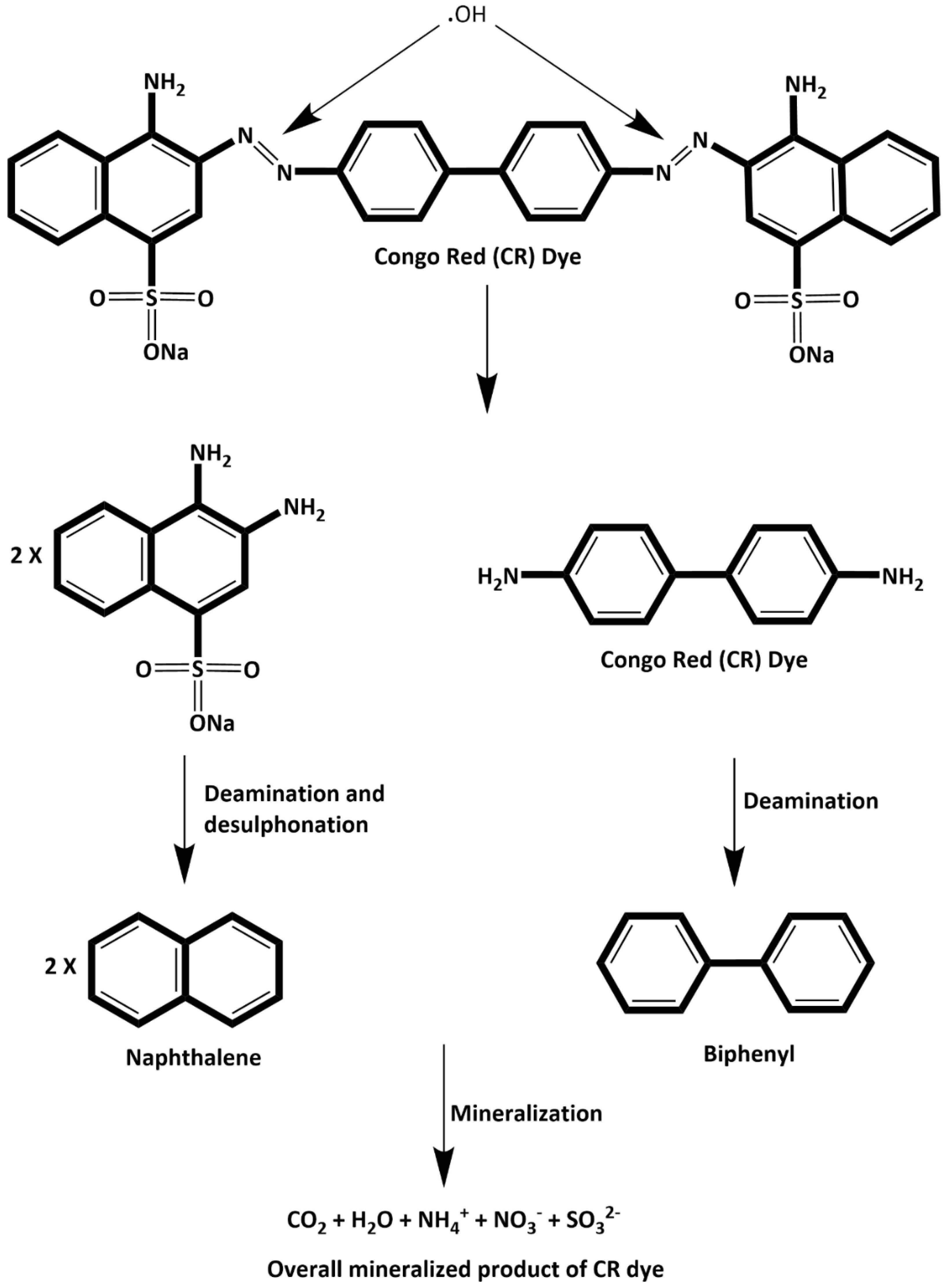

3.3.3. Mechanism of Mineralization

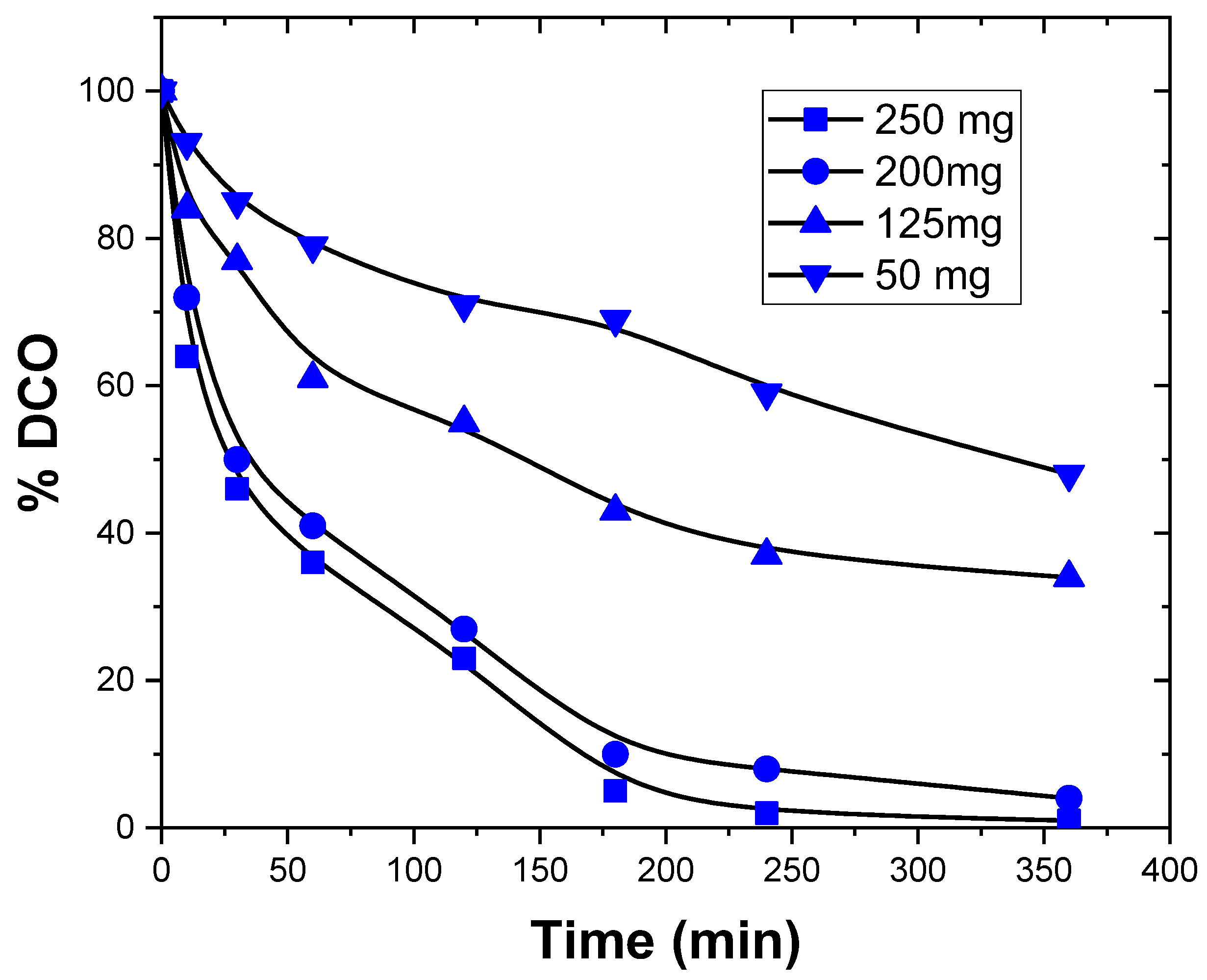

3.3.4. Catalyst Mass Effect

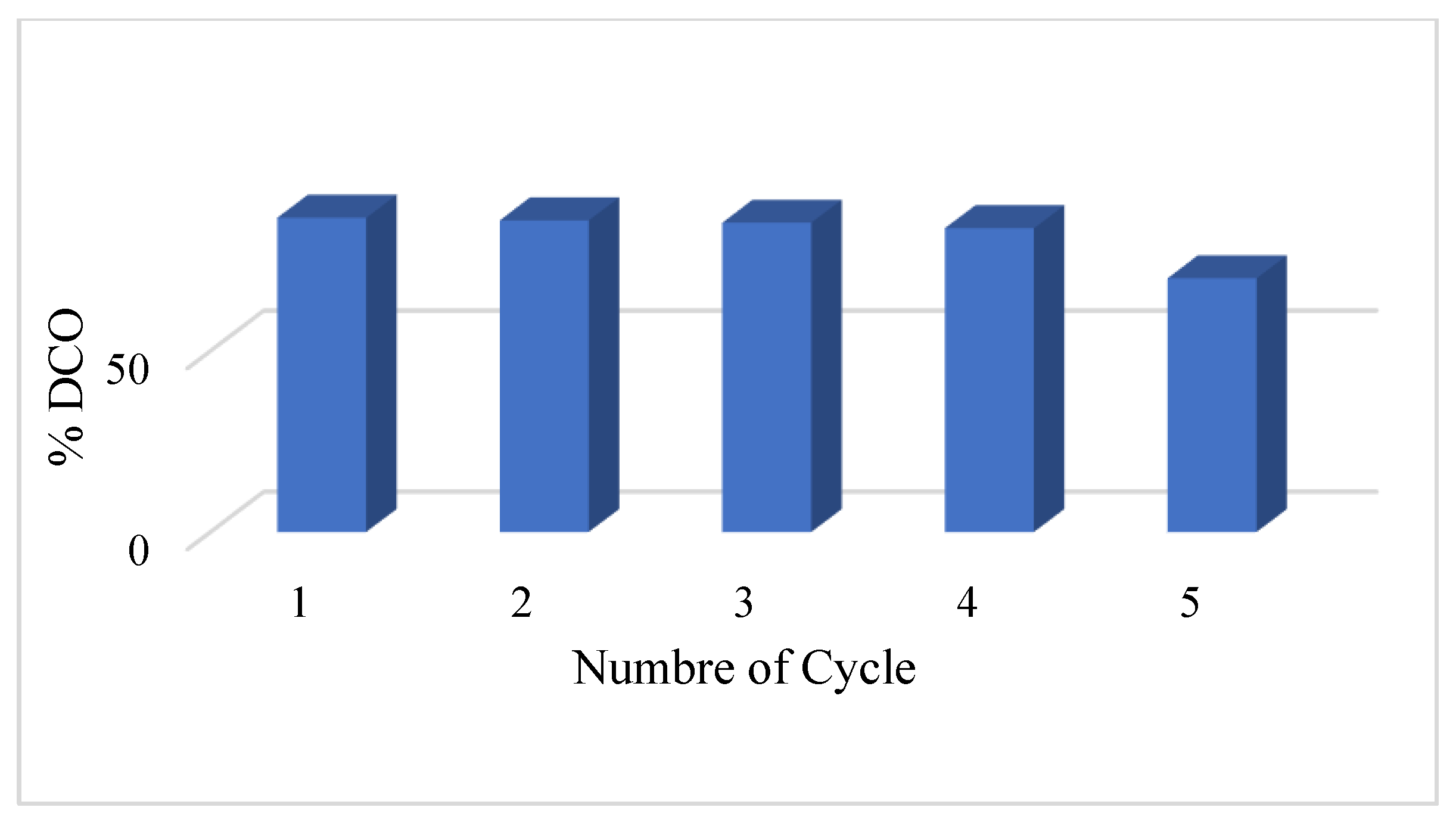

3.3.5. Regeneration of MOFB@ZnO

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Nasir, S.; Hussein, M.Z.; Zainal, Z.; Yusof, N.A. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials / Allotropes : A Glimpse of Their Synthesis, Properties and Some Applications. Materials 2018, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gęca, M.; Khalil, A.M.; Tang, M.; Bhakta, A.K.; Snoussi, Y.; Nowicki, P.; Wiśniewska, M.; Chehimi, M.M. Surface Treatment of Biochar—Methods, Surface Analysis and Potential Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Surfaces 2023, 6, 179–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.R.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K. Parametric Studies on Hydrothermal Gasification of Biomass Pellets Using Box-Behnken Experimental Design to Produce Fuel Gas and Hydrochar. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 388, 135804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibien, L.; Parot, M.; Fotsing, P.N.; Gaveau, P.; Woumfo, E.D.; Vieillard, J.; Napoli, A.; Brun, N. Ionothermal Carbonization in [Bmim][FeCl4]: An Opportunity for the Valorization of Raw Lignocellulosic Agrowastes into Advanced Porous Carbons for CO2 Capture. Green Chemistry 2020, 22, 5423–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, R.; Vivekanand, V.; Pandey, A.K.; Tarafdar, A.; Awasthi, M.K.; Shakya, A.; Kim, S.H.; Sim, S.J.; Tuan, H.A.; Pandey, A. Emerging Trends in Role and Significance of Biochar in Gaseous Biofuels Production. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2023, 30, 103100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghogia, A.C.; Millán, L.M.R.; White, C.E.; Nzihou, A. Synthesis and Growth of Green Graphene from Biochar Revealed by Magnetic Properties of Iron Catalyst. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202201864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenough, S.; Dumont, M.-J.; Prasher, S. The Physicochemical Properties of Biochar and Its Applicability as a Filler in Rubber Composites : A Review. Materials Today Communications 2021, 29, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmuk, G.; Videgain, M.; Manyà, J.J.; Duman, G.; Yanik, J. Effects of Pyrolysis Temperature and Pressure on Agronomic Properties of Biochar. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2023, 169, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, A.K.; Snoussi, Y.; Garah, M. El; Ammar, S.; Chehimi, M.M. Brewer’s Spent Grain Biochar : Grinding Method Matters. Journal of Carbon Research 2022, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, M.; Marković, M.; Raček, J.; Šipka, M.; Chorazy, T.; Tošić, I.; Hlavínek, P. The Use of Biochar Made from Biomass and Biosolids as a Substrate for Green Infrastructure: A Review. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2023, 32, 100999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, C.; Alahakoon, Y.A.; Malaweera Arachchi, U.; Mlsna, T.E.; Gunatilake, S.R.; Zhang, X. Phosphorus-Enriched Biochar for the Remediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2023, 12, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués, I.; Mazzurco Miritana, V.; Passatore, L.; Zacchini, M.; Peruzzi, E.; Carloni, S.; Pietrini, F.; Marabottini, R.; Chiti, T.; Massaccesi, L.; et al. Biochar Soil Amendment as Carbon Farming Practice in a Mediterranean Environment. Geoderma Regional 2023, 33, e00634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Sarkar, D.; Pervez, M.N.; Paul, S.; Cai, Y.; Naddeo, V.; Firoz, S.H.; Islam, M.S. Synthesis, Characterization and Performance Evaluation of Burmese Grape (Baccaurea Ramiflora) Seed Biochar for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Water 2023, 15, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoka, H.; Snoussi, Y.; Bhakta, A.K.; El Garah, M.; Khalil, A.M.; Jouini, M.; Ammar, S.; Chehimi, M.M. Evidencing the Synergistic Effects of Carbonization Temperature, Surface Composition and Structural Properties on the Catalytic Activity of Biochar/Bimetallic Composite. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2023, 173, 106069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarian, S. To What Extent Could Biochar Replace Coal and Coke in Steel Industries? Fuel 2023, 339, 127401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaiyan, P.; Dos Reis, G.S.; Karuppiah, D.; Subramaniyam, C.M.; García-Alvarado, F.; Lassi, U. Recent Progress in Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials for Li-Ion and Na-Ion Batteries—A Review. Batteries 2023, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Boobalan, T.; Sathish, M.; Hotha, S.; Thallada, B. Utilization of CO2 Activated Litchi Seed Biochar for the Fabrication of Supercapacitor Electrodes. Biomass and Bioenergy 2023, 171, 106747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.E., M.; Chandewar, P.R.; Shee, D.; Sankar Mal, S. Phosphomolybdic Acid Embedded into Biomass-Derived Biochar Carbon Electrode for Supercapacitor Applications. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2023, 936, 117354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesini, J.; Perondi, D.; Godinho, M.V.M.V.G.P.G.O.C.M.; Piazza, D. Production and Application of Biochar in a UV Radiation-Curable Epoxy Paint as a Substitute for Graphite. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi-Golezani, K.; Farhangi-Abriz, S. Biochar Related Treatments Improved Physiological Performance, Growth and Productivity of Mentha Crispa L. Plants under Fluoride and Cadmium Toxicities. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 194, 116287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalina, F.; Krishnan, S.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. Recent Advancement and Applications of Biochar Technology as a Multifunctional Component towards Sustainable Environment. Environmental Development 2023, 46, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilli, M.A.; Paranychianakis, N. V.; Lionoudakis, K.; Kritikaki, A.; Voutsadaki, S.; Saru, M.L.; Komnitsas, K.; Nikolaidis, N.P. The Impact of Sewage-Sludge- and Olive-Mill-Waste-Derived Biochar Amendments to Tomato Cultivation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Gaur, R.; Shahabuddin, S.; Tyagi, I. Biochar as Sustainable Alternative and Green Adsorbent for the Remediation of Noxious Pollutants: A Comprehensive Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalina, F.; Krishnan, S.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. Biochar and Sustainable Environmental Development towards Adsorptive Removal of Pollutants: Modern Advancements and Future Insight. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2023, 173, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ambika, S.; Hassani, A.; Nidheesh, P. V. Waste to Catalyst: Role of Agricultural Waste in Water and Wastewater Treatment. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 858, 159762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawy, H.A.; Elhusseiny, A.F.; Hussein, S.M.; Sadik, W.A. Sustainable and Energy-Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Textile Dye Assisted by Ecofriendly Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadadi, A.; Imessaoudene, A.; Bollinger, J.C.; Bouzaza, A.; Amrane, A.; Tahraoui, H.; Mouni, L. Aleppo Pine Seeds (Pinus Halepensis Mill.) as a Promising Novel Green Coagulant for the Removal of Congo Red Dye: Optimization via Machine Learning Algorithm. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 331, 117286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad Aftab, R.; Zaidi, S.; Aslam Parwaz Khan, A.; Arish Usman, M.; Khan, A.Y.; Tariq Saeed Chani, M.; Asiri, A.M. Removal of Congo Red from Water by Adsorption onto Activated Carbon Derived from Waste Black Cardamom Peels and Machine Learning Modeling. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 71, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoye, P.O.; Bamigboye, M.O.; Ogunbiyi, O.D.; Akano, M.T. Toxicity and Decontamination Strategies of Congo Red Dye. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2022, 19, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachin; Pramanik, B.K.; Singh, N.; Zizhou, R.; Houshyar, S.; Cole, I.; Yin, H. Fast and Effective Removal of Congo Red by Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, E.C.; Olatunde, O.C.; Wojuola, O.B.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Applications of Transition Metal Oxides and Chalcogenides and Their Composites in Water Treatment: A Review. Environmental Advances 2023, 11, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Qi, D. Low-temperature Synthesis of Maize Straw biochar-ZnO Nanocomposites for Efficient Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202300511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.F.; Abdulqodus, A.N.; Almessiere, M.A. Biosynthesis of Al-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles with Different Al Doping Ratio for Methylene Orange Dye Degradation Activity. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 34920–34936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunkhe, T.T.; Kumar, V.; Kadam, A.N.; Mali, M.; Misra, M. Rational Construction of Hollow ZnO@SnS2 Core-Shell Nanorods: A Way to Boost Catalytic Removal of Cr (VI) Ions, Antibiotic and Industrial Dyes. Ceramics International 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, D.S.R.V.A.C.S.K.P.T.V.K.M.S.P.K.A.K. Soapnut Plant–Mediated ZnO and Ag-ZnO Nanoparticles for Environmental and Biological Applications. emergent mater. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Fei, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, A.; Sun, D. Optimization of Photoelectric Properties of Transparent Conductive B and Ga Co-Doped ZnO Films for Electrochromic Applications. Ceramics International 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, R.P.L.; Raimundo, R.A.; Medeiros, E.S.; Torquato, R.A. Structural, Morphological, Optical and Thermoresistive Study of the Polyaniline/Polylactic Acid/ZnO Films Produced by Solution Blow Spraying for Temperature Sensors. Ceramics International. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Fan, C.; Ning, C.; Wang, W. Cathodic Electrophoretic Deposited HA-rGO-ZnO Ternary Composite Coatings on ZK60 Magnesium Alloy for Enhanced Corrosion Stability. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 37604–37622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertepov, A.E.; Fedorova, A.A.; Batkin, A.M.; Knotko, A. V; Maslakov, K.I.; Doljenko, V.D.; Vasiliev, A. V; Kapustin, G.I.; Shatalova, T.B.; Sorokina, N.M.; et al. CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol on CuO-ZnO/SiO2 and CuO-ZnO/CeO2 -SiO2 Catalysts Synthesized with β -Cyclodextrin Template. Catalyst 2023, 13, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierałtowska, S.; Zaleszczyk, W.; Putkonen, M.; Zasada, D.; Korona, K.P.; Norek, M. Regularly Arranged ZnO / TiO2, HfO2, and ZrO2 Core / Shell Hybrid Nanostructures - towards Selection of the Optimal Shell Material for Efficient ZnO-Based UV Light Emitters. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 31679–31690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Rai, S.; Pandit, S.; Roy, A.; Gacem, A.; El-hiti, G.A.; Yadav, K.K.; Ravindran, B.; Cheon, J.; Jeon, B. Neodymium-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Catalytic Cathode for Enhanced Efficiency of Microbial Desalination Cells. Catalysts 2023, 2, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.; Darroudi, M. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles_ Biological Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Ceramics International 2017, 43, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubangakene, N.O.; Elwardany, A.; Fujii, M.; Sekiguchi, H.; Elkady, M.; Shokry, H. Biosorption of Congo Red Dye from Aqueous Solutions Using Pristine Biochar and ZnO Biochar from Green Pea Peels. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2023, 189, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.M.; Imran, M.; Hussain, T.; Naeem, M.A.; Al-Kahtani, A.A.; Shah, G.M.; Ahmad, S.; Farooq, A.; Rizwan, M.; Majeed, A.; et al. Effective Sequestration of Congo Red Dye with ZnO/Cotton Stalks Biochar Nanocomposite: MODELING, Reusability and Stability. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2021, 25, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrava, A.; Matei, C.; Diacon, A.; Moscalu, F.; Berger, D. Novel ZnO-Biochar Nanocomposites Obtained by Hydrothermal Method in Extracts of Ulva Lactuca Collected from Black Sea. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 10003–10013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxmi Deepak Bhatlu, M.; Athira, P.S.; Jayan, N.; Barik, D.; Dennison, M.S. Preparation of Breadfruit Leaf Biochar for the Application of Congo Red Dye Removal from Aqueous Solution and Optimization of Factors by RSM-BBD. Adsorption Science and Technology 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, L.; Doriya, K.; Kumar, D.S. Moringa Oleifera: A Review on Nutritive Importance and Its Medicinal Application. Food Science and Human Wellness 2016, 5, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Dave, H.; Maurya, D.M.; Singh, D.; Kumari, M.; Prasad, K.S. Sorptive Removal of Aqueous Arsenite and Arsenate Ions onto a Low Cost, Calcium Modified Moringa Oleifera Wood Biochar (CaMBC). Environmental Quality Management 2022, 31, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourai, M.; Nayak, A.K.; Nial, P.S.; Satpathy, B.; Bhuyan, R.; Singh, S.K.; Subudhi, U. Thermal Plasma Processing of Moringa Oleifera Biochars: Adsorbents for Fluoride Removal from Water. RSC Advances 2023, 13, 4340–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, Y.; Nadi, A.; Mechnou, I.; Saadouni, M.; Cherkaoui, O.; Zyade, S. High Adsorption Capacities of Crystal Violet Dye by Low-Cost Activated Carbon Prepared from Moroccan Moringa Oleifera Wastes: Characterization, Adsorption and Mechanism Study. Diamond and Related Materials 2023, 135, 109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Islam, M.S.; Arifin, M.T.; Firoz, S.H. Chitosan-ZnO Decorated Moringa Oleifera Seed Biochar for Sequestration of Methylene Blue: Isotherms, Kinetics, and Response Surface Analysis. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring and Management 2022, 18, 100752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, S.S.A.M.K.; Javidan, P.; Baghdadi, M.; Mehrdadi, N. Green Synthesis of Pd@biochar Using the Extract and Biochar of Corn-Husk Wastes for Electrochemical Cr(VI) Reduction in Plating Wastewater. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 109911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Su, X.; Zhang, X.; Cao, W.; Xu, Y. Role of the Biochar Modified with ZnCl2 and FeCl3 on the Electrochemical Degradation of Nitrobenzene. Chemosphere 2021, 275, 129966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhao, L.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shi, B. An Iron–Based Biochar for Persulfate Activation with Highly Efficient and Durable Removal of Refractory Dyes. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Feng, M.; Wang, Y. Enhancing the Heterogeneous Electro-Fenton Degradation of Methylene Blue Using Sludge-Derived Biochar-Loaded Nano Zero-Valent Iron. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 59, 104980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, A.K.; Tang, M.; Snoussi, Y.; Khalil, A.M.; Mascarenhas, R.J.; Mekhalif, Z.; Abderrabba, M.; Ammar, S.; Chehimi, M.M. Sweety, Salty, Sour, and Romantic Biochar - Supported ZnO : Highly Active Composite Catalysts for Environmental Remediation. Emergent Materials 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, P.; Dinpazhoh, L.; Khataee, A.; Orooji, Y. Sonocatalytic Activity of Biochar-Supported ZnO Nanorods in Degradation of Gemifloxacin: Synergy Study, Effect of Parameters and Phytotoxicity Evaluation. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2019, 55, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankomal; Kaur, H. Synergistic Effect of Biochar Impregnated with ZnO Nano-Flowers for Effective Removal of Organic Pollutants from Wastewater. Applied Surface Science Advances 2022, 12, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyen, N.T.; Nguyen, K. Van; Dang, N. Van; Huy, T.Q.; Linh, P.H.; Trung, N.T.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Thanh, D. Van Facile One-Step Pyrolysis of ZnO/Biochar Nanocomposite for Highly Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue Dye from Aqueous Solution. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 26816–26827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Ji.I.; Ma, W.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, C.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, C. Resolving the Tribo-Catalytic Reaction Mechanism for Biochar Regulated Zinc Oxide and Its Application in Protein Transformation. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 607, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, E.T.; Sintayehu, Y.D.; Gonfa, B.A.; Sabir, F.K.; Shumete, M.K.; Ravikumar, C.R.; Kumar, N.; Murthy, H.C.A. Green Synthesis of Ternary ZnO/ZnCo2O4 Nanocomposites Using Ricinus Communis Leaf Extract for the Electrochemical Sensing of Sulfamethoxazole. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2024, 160, 111964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, K.S.N.T.; Nascimento, S.Q.; Mazzetto, S.E.; Ribeiro, V.G.P.; Mele, G.; Carbone, L.; Luz, R.A.S.; Gerôncio, E.T.S.; Cantanhêde, W. Structural, Photoluminescent and Electrochemical Properties of Self-Assembled Co3[Co(CN)6]2/ZnO Nanocomposite. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2023, 551, 121473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, D.; Gülcan, M. Synthesis, Characterization, and in-Situ H2O2 Generation Activity of Activated Carbon/Goethite/Fe3O4/ZnO for Heterogeneous Electro-Fenton Degradation of Organics from Woolen Textile Wastewater. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2023, 122, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsson, J.; Abrahams, S.C.; Kvick, Å. Atomic Displacement, Anharmonic Thermal Vibration, Expansivity and Pyroelectric Coefficient Thermal Dependences in ZnO. Acta Crystallographica Section B 1989, 45, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnay, G.; Kihara, K. Powder Diffraction 1986, 1, 64–77.

- Schulz, H.; Thiemann, K.H. Structure Parameters and Polarity of the Wurtzite Type Compounds Sic—2H and ZnO. Solid State Communications 1979, 32, 783–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Fernandez, N.B.; Mullassery, M.D.; Surya, R. Biochar-ZnO/Polyaniline Composite in Energy Storage Application: Synthesis, Characterization and Electrochemical Analysis. Results in Chemistry 2023, 6, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, Z.; Brites, P.; Ferreira, N.M.; Figueiredo, G.; Otero-Irurueta, G.; Gonçalves, I.; Mendo, S.; Ferreira, P.; Nunes, C. Thermoplastic Starch-Based Films Loaded with Biochar-ZnO Particles for Active Food Packaging. Journal of Food Engineering 2024, 361, 111741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, Y.; Ametani, A.; Tsunehiro, J.; Nomura, K.; Itoh, M.; Fukui, F.; Kaminogawa, S. Macrophage Stimulation Activity of the Polysaccharide Fraction from a Marine Alga (Porphyra Yezoensis): Structure-Function Relationships and Improved Solubility. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 1995, 59, 1933–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Dhara, S.; Velmurugan, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Analysis on Binding Energy and Auger Parameter for Estimating Size and Stoichiometry of ZnO Nanorods. International Journal of Spectroscopy 2012, 2012, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroubaix, G.; Marcus, P. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Analysis of Copper and Zinc Oxides and Sulphides. Surface and Interface Analysis 1992, 18, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, L.S.; Baer, D.R.; Zachara, J.M. Auger Parameter Measurements of Zinc Compounds Relevant to Zinc Transport in the Environment. Surface and Interface Analysis 1989, 14, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferro, A.; Rovere, M.; Padovano, E.; Bartoli, M.; Mauro, G. Introducing the Novel Mixed Gaussian-Lorentzian Lineshape in the Analysis of the Raman Signal of Biochar. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Snoussi, Y.; Bhakta, A.K.; El Garah, M.; Khalil, A.M.; Ammar, S.; Chehimi, M.M. Unusual, Hierarchically Structured Composite of Sugarcane Pulp Bagasse Biochar Loaded with Cu/Ni Bimetallic Nanoparticles for Dye Removal. Environmental Research 2023, 232, 116232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naydenova, I.; Radoykova, T.; Petrova, T.; Sandov, O.; Valchev, I. Utilization Perspectives of Lignin Biochar from Industrial Biomass Residue. Molecules 2023, 28, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, N.P.F.; Lourenço, M.A.O.; Baleuri, S.R.; Bianco, S.; Jagdale, P.; Calza, P. Biochar Waste-Based ZnO Materials as Highly Efficient Photocatalysts for Water Treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergan, B.T.; Aydin, E.S.; Gengec, E. Improving Electro-Fenton Degradation Performance Using Waste Biomass-Derived-Modified Biochar Electrodes : A Real Environment Textile Water Treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 111439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prediction and Optimization of Electroplated Ni-Based Coating Composition and Thickness Using Central Composite Design and Artificial Neural Network. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry 2021, 51, 1591–1604. [CrossRef]

- Sassi, W.; Msaadi, R.; Ardhaoui, N.; Ammar, S.; Nafady, A. Selective/Simultaneous Batch Adsorption of Binary Textile Dyes Using Amorphous Perlite Powder: Aspects of Central Composite Design Optimization and Mechanisms. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering 2023, 21, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanmi, I.; Sassi, W.; Oulego, P.; Collado, S.; Ghorbal, A.; Díaz, M. Optimization and Comparison Study of Adsorption and Photosorption Processes of Mesoporous Nano-TiO 2 during Discoloration of Indigo Carmine Dye. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2022, 342, 112138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoulih, M.; Tigani, S.; Byoud, F.; Rharib, M.E.; Saadane, R.; Pierre, S.; Chehri, A.; Ghachtouli, S.E. Electrocoagulation-Based AZO DYE (P4R) Removal Rate Prediction Model Using Deep Learning. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 236, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, W.; Ghanmi, I.; Oulego, P.; Collado, S.; Ammar, S.; Díaz, M. Pomegranate Peel-Derived Biochar as Ecofriendly Adsorbent of Aniline-Based Dyes Removal from Wastewater. Clean Techn Environ Policy 2023, 25, 2689–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhtar, S.N.N.M.; Yusof, N.; Fajrina, N.; Hairom, N.H.H.; Aziz, F.; Wan Salleh, W.N. V2O5/Cds as Nanocomposite Catalyst for Congo Red Dye Photocatalytic Degradation under Visible Light. Materials Today: Proceedings 2024, 96, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, J.; Vikrant, K.; Kim, K.-H.; Kumar, S.; Pal, M.; Badru, R.; Masand, S.; Momoh, J. Photocatalytic Degradation of Congo Red Dye Using Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Prepared Using Carica Papaya Leaf Extract. Materials Today Sustainability 2023, 22, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, B.; Muthukutty, B.; Chen, S.M.; Amanulla, B.; Ramaraj, S.K. Sustainable One-Pot Synthesis of Strontium Phosphate Nanoparticles with Effective Charge Carriers for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Carcinogenic Naphthylamine Derivative. New Journal of Chemistry 2021, 45, 15437–15447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, H.; Ganda, V.; Kiranadi, B.; Pinontoan, R. Metabolite Identification from Biodegradation of Congo Red by Pichia Sp. KnE Life Sciences 2020, 2020, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, U.O.; Wu, J.J.; Asiri, A.M.; Anandan, S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Congo Red Using PbTiO3 Nanorods Synthesized via a Sonochemical Approach. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 11851–11858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthapandi, M.; Saravanan, A.; Manohar, P.; Luong, J.H.T.; Gedanken, A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes and Antimicrobial Activities by Polyaniline–Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Dot Nanocomposite. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhu, M.; Chen, R.; Lu, B.; Liu, H. Adsorption and Degradation of Congo Red on a Jarosite-Type Compound. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 102972–102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, D.; Alblawi, E.; Alsukaib, A.K.D.; Al Shammari, B. Removal of Congo Red Dye by Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Process : Optimization, Degradation Pathways, and Mineralization. Sustainable Water Resources Management 2024, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, N.; Labiadh, L.; Oturan, M.A.; Oturan, N.; Gadri, A.; Ammar, S.; Brillas, E. Electrochemical Mineralization of the Antibiotic Levofloxacin by Electro-Fenton-Pyrite Process. Chemosphere 2015, 141, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yashni, G.; Al-gheethi, A.; Maya, R.; Radin, S.; Dai-viet, N.V.; Al-kahtani, A.A.; Al-sahari, M.; Jihan, N.; Hazhar, N.; Noman, E.; et al. Bio-Inspired ZnO NPs Synthesized from Citrus Sinensis Peels Extract for Congo Red Removal from Textile Wastewater via Photocatalysis : Optimization, Mechanisms, Techno-Economic Analysis. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganash, A.; Alajlani, L.; Ganash, E.; Al-Moubaraki, A. Efficient Electrochemical Degradation of Congo Red Dye by Pt/CuNPs Electrode with Its Attractive Performance, Energy Consumption, and Mechanism: Experimental and Theoretical Approaches. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 56, 104497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, Z. Preparation of MWCNT-MnO2/Ni Foam Composite Electrode for Electrochemical Degradation of Congo Red Wastewater. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2021, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, F.; Dawoud, T.M.; Alshehrei, F.; Alsamhary, K.; Almansob, A. Decolorization of Acid Blue 29, Disperse Red 1 and Congo Red by Different Indigenous Fungal Strains. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, N.; Khan, I.; Shah, T.; Gul, T.; Khan, N.; Saeed, K. Ag–Co Oxides Nanoparticles Supported on Carbon Nanotubes as an Effective Catalyst for the Photodegradation of Congo Red Dye in Aqueous Medium. Inorganic and Nano-Metal Chemistry 2020, 50, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.H.; Rahman, M.N.A.; Kamarudin, W.F.W.; Irwan, Z.; Muhammud, A.; Akhir, N.E.F.M.; Yaafar, M.R. Photocatalytic Degradation of Congo Red Dye Based on Titanium Dioxide Using Solar and UV Lamp. J Fundam Appl Sci 2018, 10, 832–846. [Google Scholar]

| Factors | Code | (- δ) | (-1) | (0) | (+1) | (+ δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolysis time tc (min) | X1 | 28 | 120 | 240 | 360 | 452 |

| Dye concentration C (mg/L) | X2 | 12 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 48 |

| Electrolysis current I (mA) | X3 | 124 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 476 |

| Name of Catalyst | Synthesis procedure | CR dye conc. | Amount of catalyst | Time/ Conditions |

% Degradation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt/Cu NPs | Electrodeposition | 150 ml of 50 mg /L | 60 min / Electrochemical | 95.95% | [93] | |

| MWCNT-MnO2/Ni foam | Hydrothermal | 500 mL of 100 mg/L | 90 min/Electrochemical | 92% | [94] | |

| ZnO-biochar (Ulva lactuca extract from Algae as a source of biochar) |

Hydro-thermal | 30 mg/L | 0.05 g catalyst/100 mL CR solution | 120 min / UV lamp | 89.28% | [45] |

| Aspergillus strains | Fungal strains used isolated from soil | 100 mg/L | 7 days at 30 °C | More than 86%. | [95] | |

| MWNTS supported Ag–Co oxides | Chemical reduction method | 10mL (80 ppm) | 0.02g | 75 min/UV | 90.37% | [96] |

| TiO2 | Not given | 250 ml of 4ppm | 0.1g | 30 min /UV lamp | 66.99% | [97] |

| MOFB@ZnO (Moringa oleifera as a precursor of biochar) |

Pyrolysis | 250 mL of 20mg/L | 0.2 g/L | 3 min for complete decolourization and 360 min for TOC removal/ electrochemical |

98% | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).