Submitted:

15 April 2024

Posted:

17 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of CQDs and CQD/TiO2

2.3. Characterization of CQDs and CQD/TiO2

2.4. Photo-catalytic activity measurements

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment on CQDs

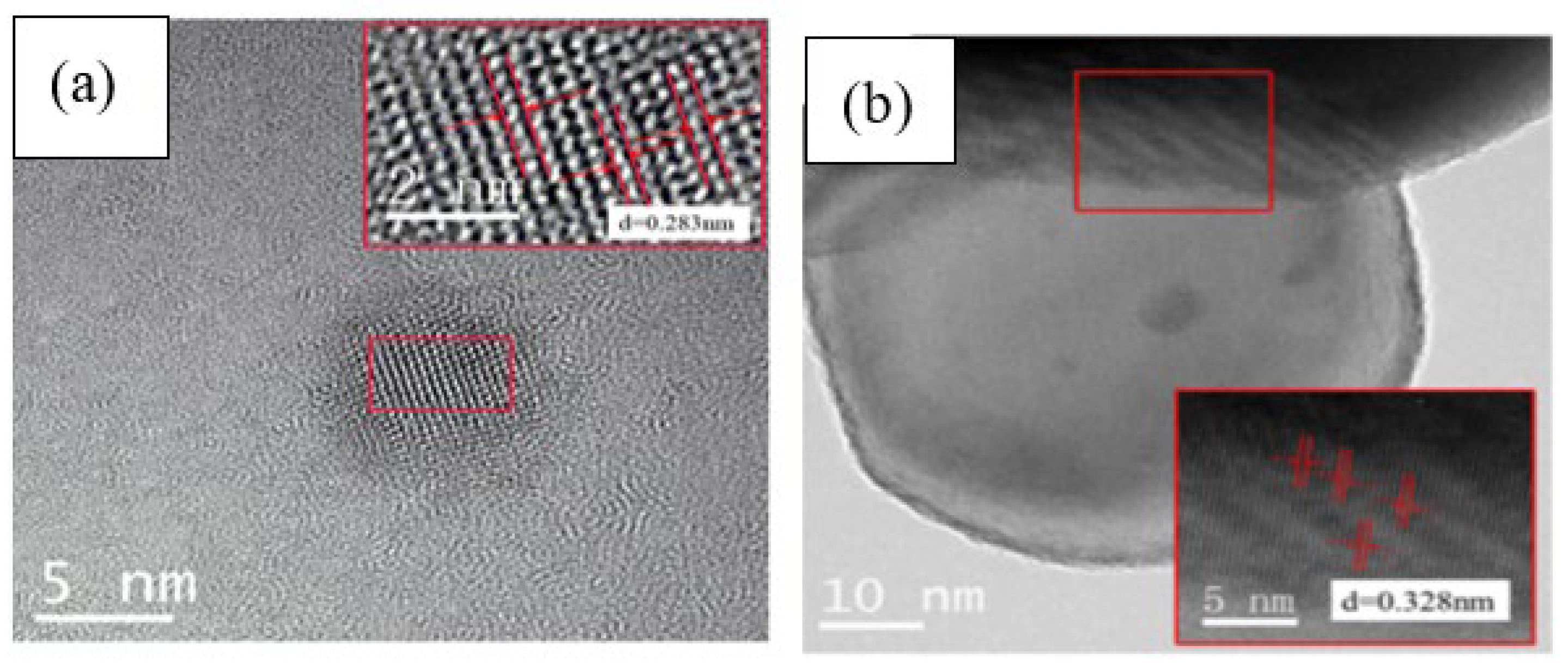

3.2. Characterization of CQDs and CQD/TiO2

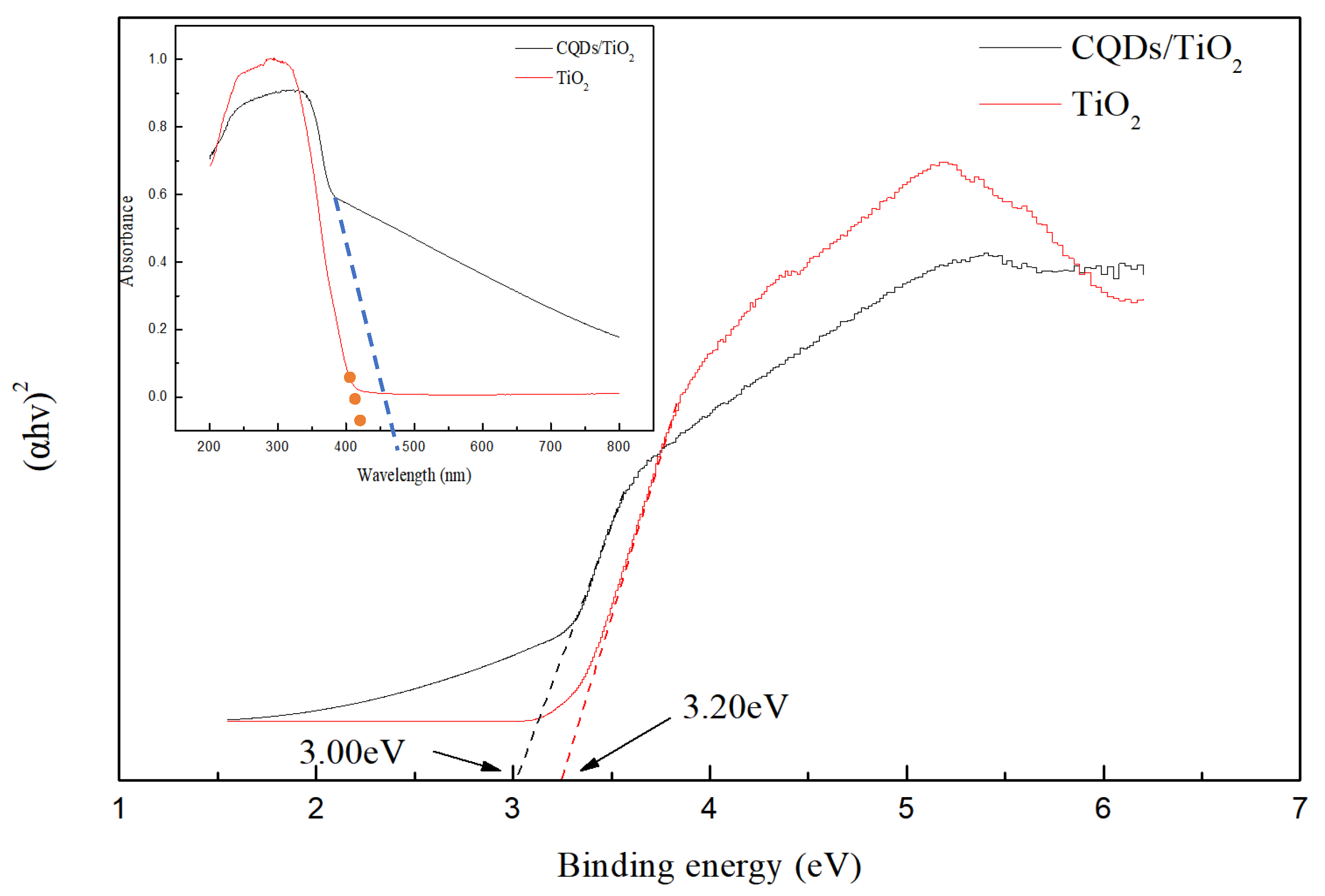

3.2. UV-Vis Analysis of CQD/TiO2

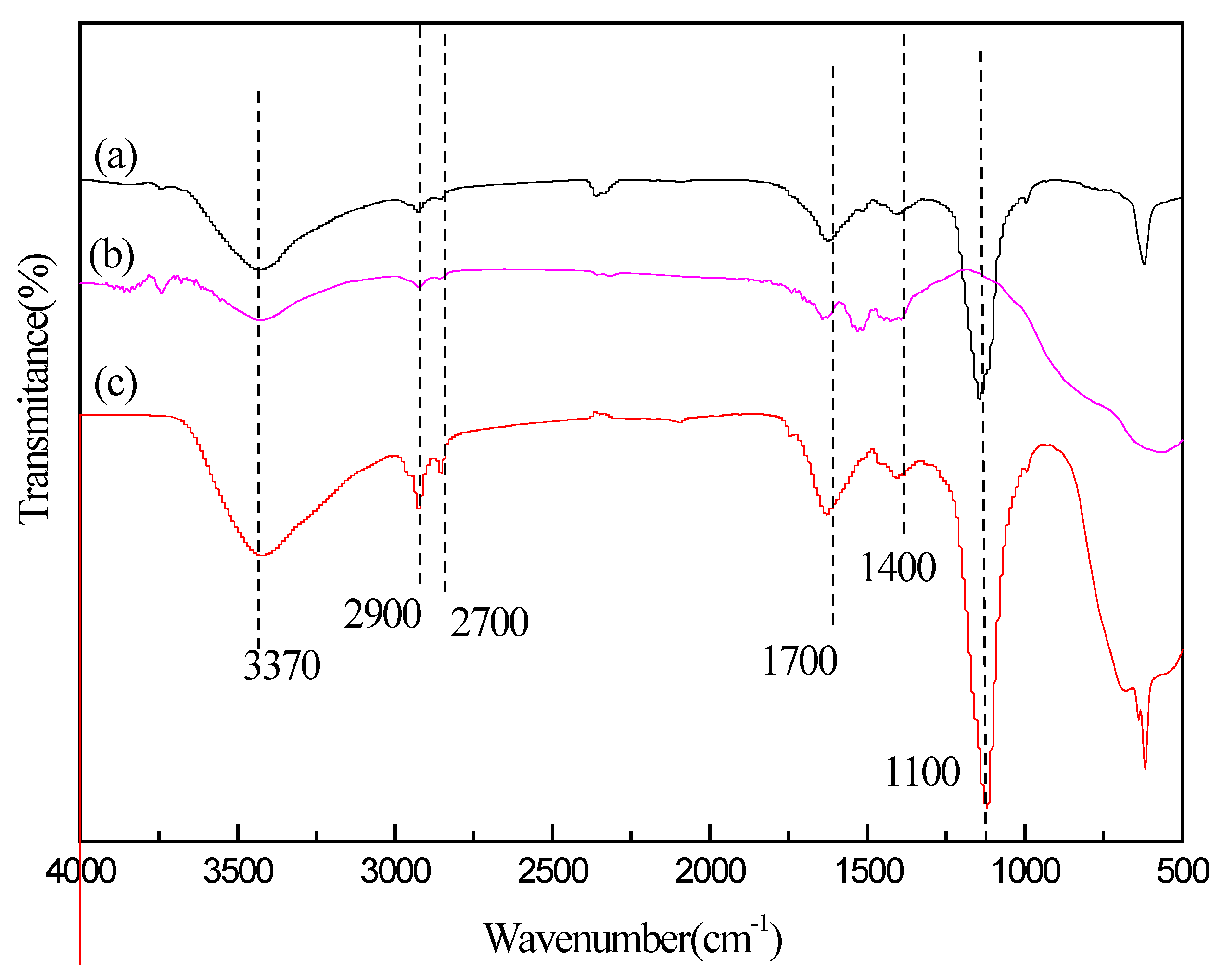

3.3. FTIR Analysis of CQD/TiO2

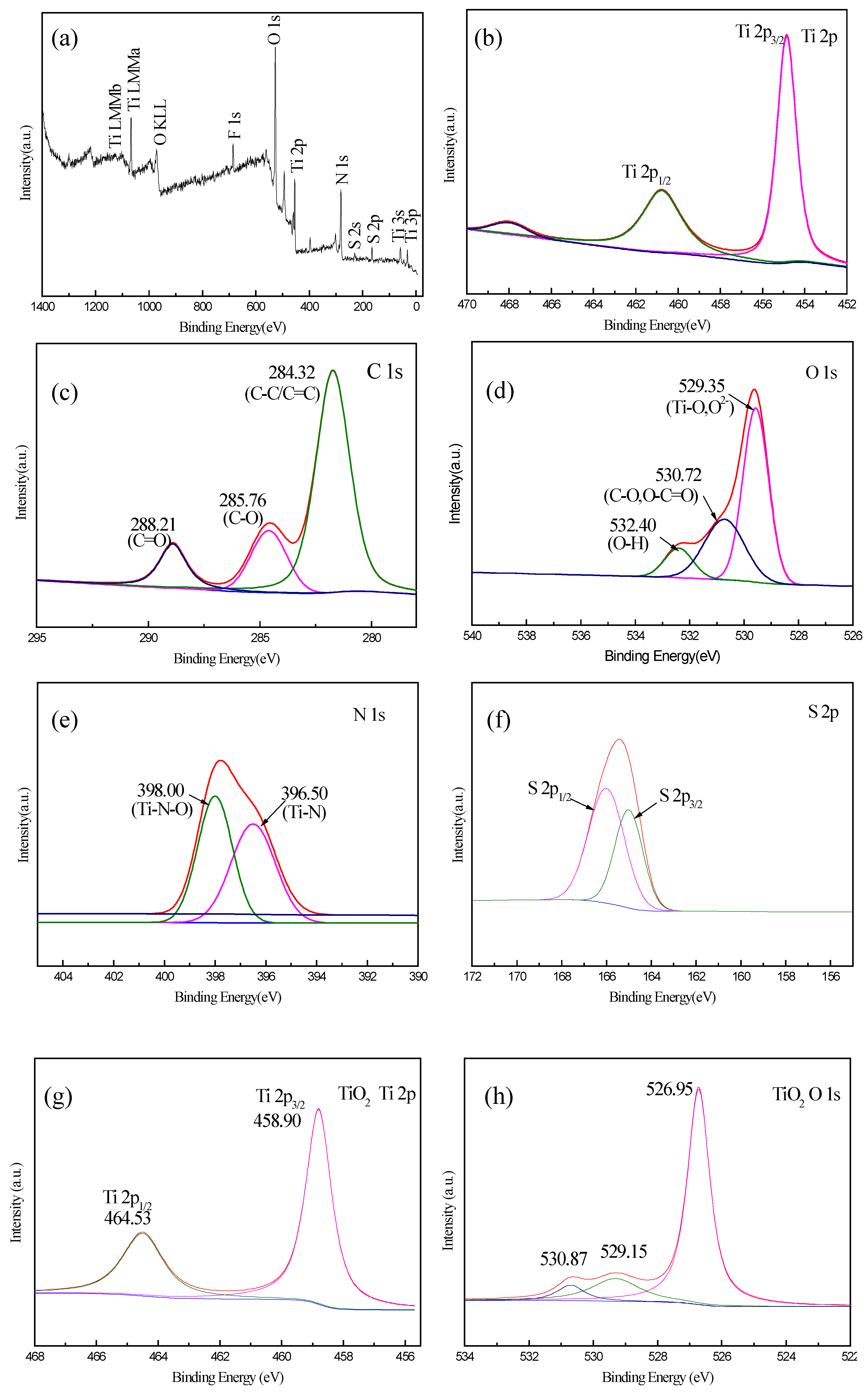

3.4. XPS analysis of CQD/TiO2

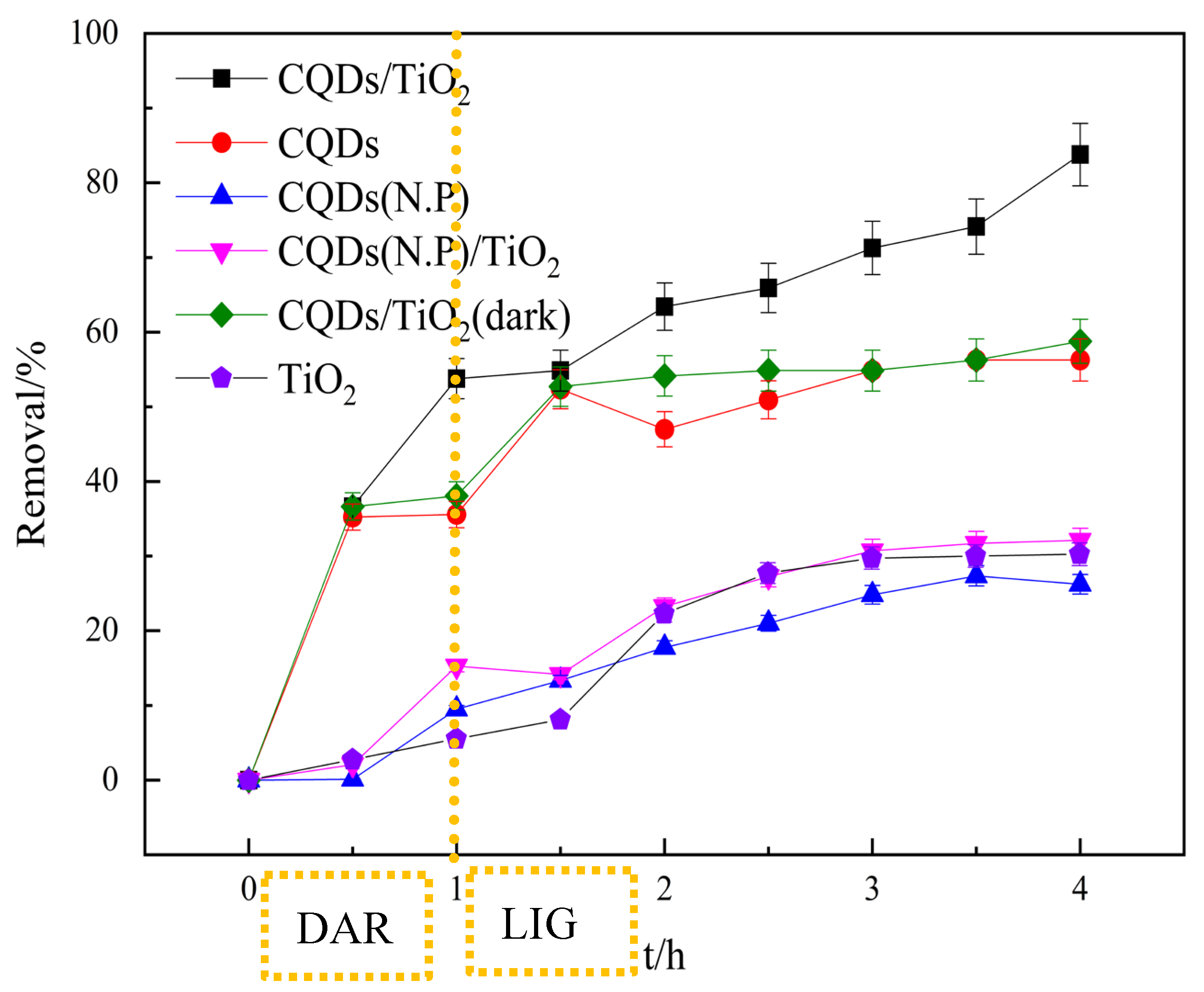

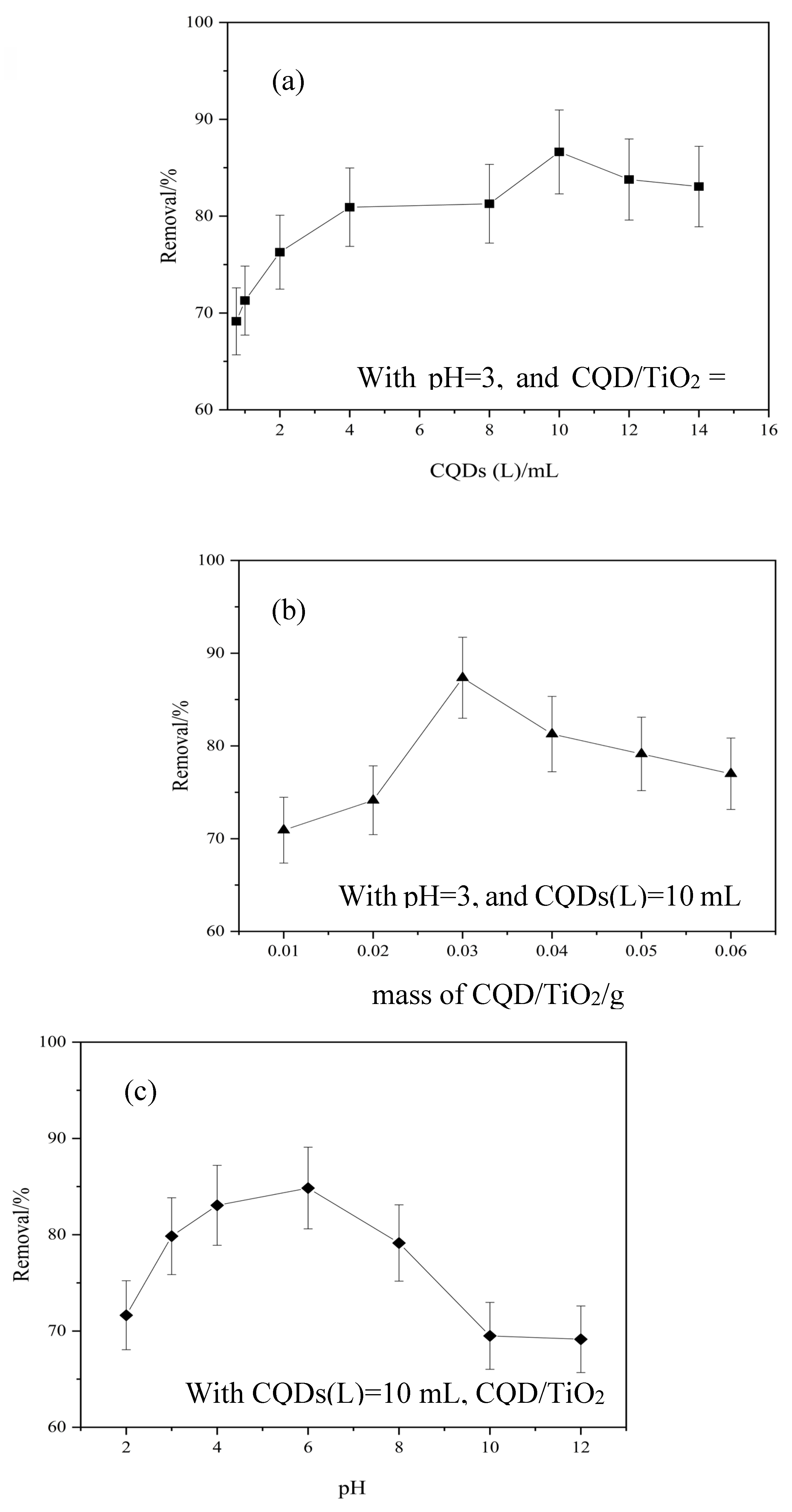

3.5. Photocatalytic Performance of CQD/TiO2 on Naphthalene Removal

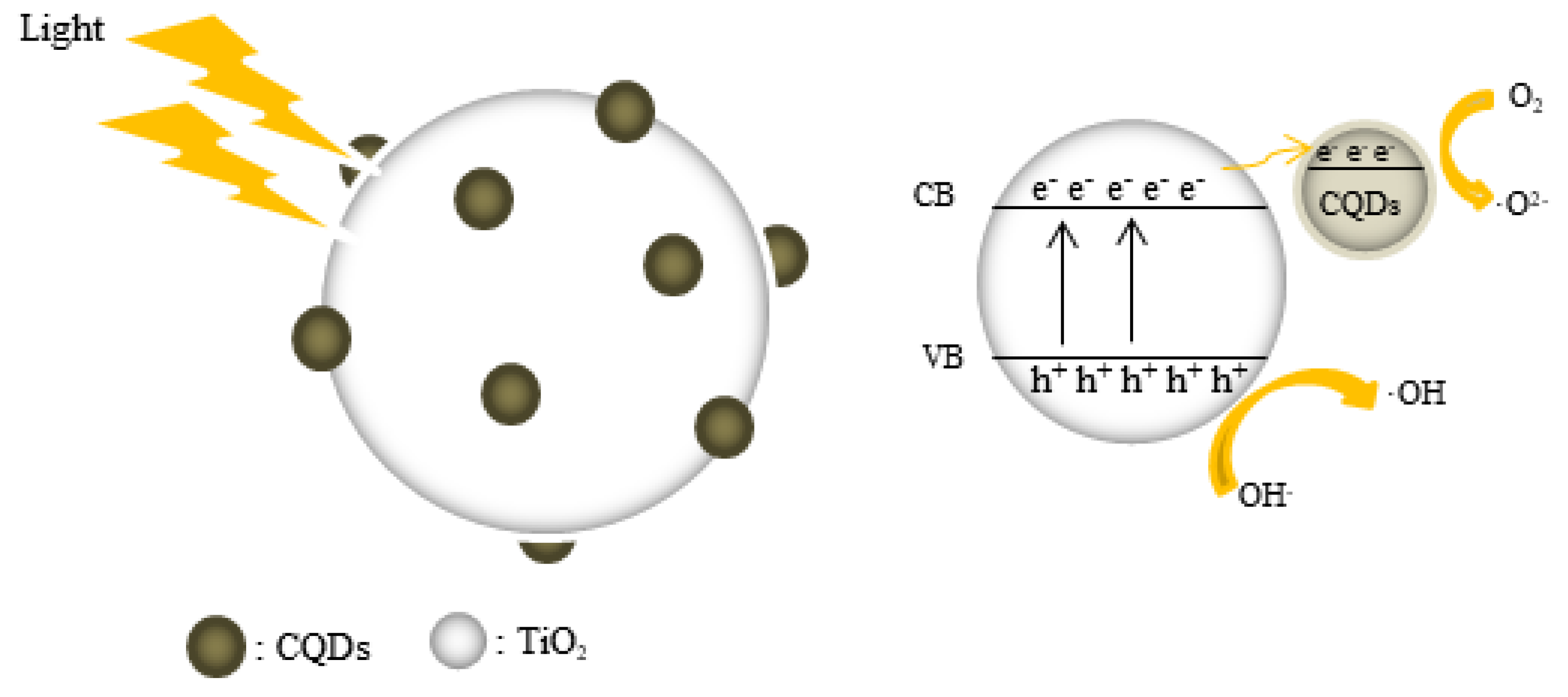

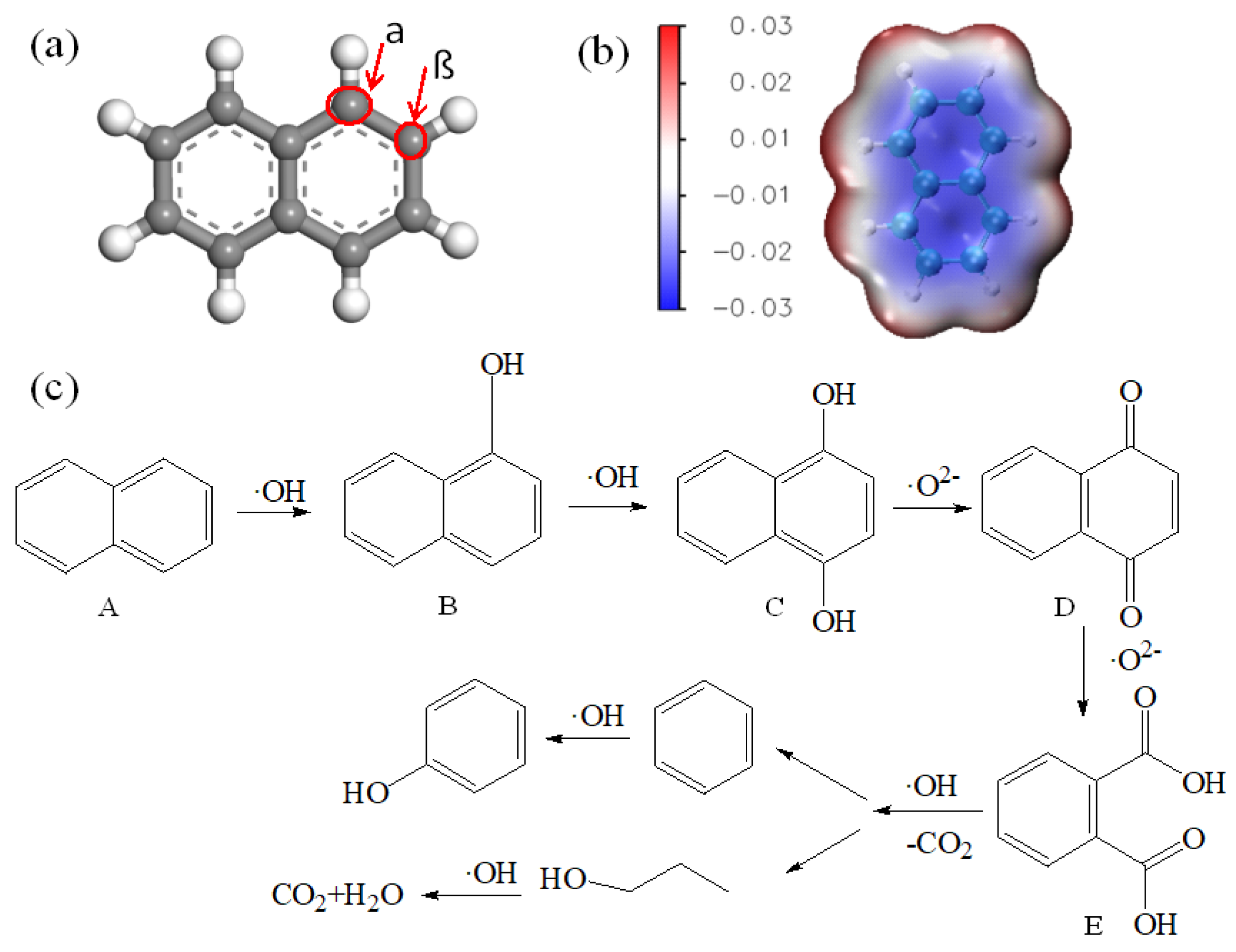

3.6. Photocatalytic Mechanism Analysis of CQD/TiO2 on Naphthalene Removal.

3.7. Kinetic Model Analysis of Naphthalene Removal by CQD/TiO2

4. Conclusions

References

- Vijayanand, M., Ramakrishnan, A., Subramanian, R., Issac, P. K., Nasr, M., Khoo, K., Rajagopal, R., Greff, B., Wan, A.N., Jeon, B.H., Chang, S.W., & Ravindran, B. Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the water environment: A review on toxicity, microbial biodegradation, systematic biological advancements, and environmental fate. Environmental Research 2023, 115716.

- Zeng, G., You, H., Du, M., Zhang, Y., Ding, Y., Xu, C., Liu, B., Chen, B. & Pan, X. Enhancement of photocatalytic activity of TiO2 by immobilization on activated carbon for degradation of aquatic naphthalene under sunlight irradiation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 412, 128498.

- Monteiro, F. C., Guimaraes, I. D. L., & Rodrigues, P. D. A. Degradation of pahs using TiO2 as a semiconductor in the heterogeneous photocatalysis process: a systematic review. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology, A. Chemistry 2023, 437, 114497.

- Abdel-Latif, H. M., Dawood, M. A., Menanteau-Ledouble, S., & El-Matbouli, M. Environmental transformation of n-TiO2 in the aquatic systems and their ecotoxicity in bivalve mollusks: A systematic review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 200, 110776.

- Lettieri, S., Pavone, M., Fioravanti, A., Santamaria Amato, L., & Maddalena, P. Charge carrier processes and optical properties in TiO2 and TiO2-based heterojunction photocatalysts: A review. Materials 2021, 14, 1645.

- Li, F., Liu, G., Liu, F., Wu, J., & Yang, S. Synergetic effect of cqd and oxygen vacancy to TiO2 photocatalyst for boosting visible photocatalytic no removal. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 452, 131237.

- Yu, X., Liu, J., Yu, Y., Zuo, S., & Li, B. Preparation and visible light photocatalytic activity of carbon quantum dots/TiO2 nanosheet composites. Carbon 2014, 68, 718–724.

- García de Arquer, F. P., Talapin, D. V., Klimov, V. I., Arakawa, Y., Bayer, M., & Sargent, E. H. Semiconductor quantum dots: Technological progress and future challenges. Science 2021, 373, eaaz8541.

- Zhang, Z., Liu, H., Xu, J., & Zeng, H.Carbon quantum dots/ biponanocomposites with enhanced visible-light absorption and charge separation. Journal of Photochemistry & Photobiology A Chemistry 2017, 336, 25–31.

- Pourreza N, Ghomi M. Green synthesized carbon quantum dots from Prosopis juliflora leaves as a dual off-on fluorescence probe for sensing mercury (II) and chemet drug. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 98, 887–896. [CrossRef]

- Das G.S., Shim J.P., Bhatnagar A., Tripathi K.M., & Kim T.Y. Biomass-derived carbon quantum dots for visible-light-induced photocatalysis and label-free detection of Fe(III) and ascorbic acid. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 15084.

- Smetacek V., Adriana Z. Green and golden seaweed tides on the rise. Nature 2013, 504, 84–88. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Y., Han, Y. L., Yang, J. J., Deng, S. L., & Wang, B. Y. Construction and photocatalysis of carbon quantum dots/layered mesoporous titanium dioxide (cqds/lm-TiO2) composites. Applied Surface Science 2021, 546, 149089.

- Piątkowska, A., Janus, M., Szymański, K., & Mozia, S. C-, N-and S-doped TiO2 photocatalysts: a review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 144.

- Li, F., Liu, G., Liu, F., Wu, J., & Yang, S. Synergetic effect of cqd and oxygen vacancy to TiO2 photocatalyst for boosting visible photocatalytic no removal. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 452, 131237.

- Khan, M. E., Mohammad, A., & Yoon, T. State-of-the-art developments in carbon quantum dots (CQDs): Photo-catalysis, bio-imaging, and bio-sensing applications. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134815.

- Marković, Z. M., Labudová, M., Danko, M., Matijasević, D., Mičušík, M., Nádaždy, V., Kováčová, M., Kleinová, A., Špitalský, Z., Pavlović, V., Milivojević, D. D., Medić, M. & Marković , B.M. Highly efficient antioxidant F- and Cl-doped carbon quantum dots for bioimaging. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 8, 16327–16338.

- Cao, F. J., Hou, X., Wang, K. F., Jin, T. Z., & Feng, H. Facile synthesis of phosphorus and nitrogen co-doped carbon dots with excellent fluorescence emission towards cellular imaging. RSC Advances 2023, 13, 21088–21095.

- Tajik, S., Dourandish, Z., Zhang, K., Beitollahi, H., Le, Q. V., Jang, H. W., & Shokouhimehr, M. Carbon and graphene quantum dots: a review on syntheses, characterization, biological and sensing applications for neurotransmitter determination. RSC Advances 2020, 10, 15406–15429.

- Deb, A., & Chowdhury, D. (2024). Biogenic carbon quantum dots: Synthesis and applications. Current Medicinal Chemistry.

- He, Z., Sun, Y., Zhang, C., Zhang, J., Liu, S., & Zhang, K., & Lan, M. Recent advances of solvent-engineered carbon dots: a review. Carbon 2023, 204, 76–93.

- Wareing, T. C., Gentile, P., & Phan, A. N. Biomass-based carbon dots: current development and future perspectives. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 15471–15501.

- Pinna, M., Binda, G., Altomare, M., Marelli, M., Dossi, C., Monticelli, D., Spanu, D., & Recchia, S. Biochar nanoparticles over TiO2 nanotube arrays: A green co-catalyst to boost the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1048.

- Nu, T. T. V., Tran, N. H. T., Truong, P. L., Phan, B. T., Dinh, M. T. N., Dinh, V. P., Phan, T.S., Go, S., Chang, M., Trinh, K.T. L., & Van Tran, V. Green synthesis of microalgae-based carbon dots for decoration of TiO2 nanoparticles in enhancement of organic dye photodegradation. Environmental Research 2022, 206, 112631.

- Guo, J., Guo, X., Yang, H., Zhang, D., & Jiang, X. Construction of Bio-TiO2/Algae Complex and Synergetic Mechanism of the Acceleration of Phenol Biodegradation. Materials 2023, 16, 3882.

- Lai, C., Yang, B., He, J., Huang, C., Li, X., Song, X., & Yong, Q. Enhanced enzymatic digestibility of mixed wood sawdust by lignin modification with naphthol derivatives during dilute acid pretreatment. Bioresource Technology 2018, 269, 18–24.

- Ghatak, H. R. Biorefineries from the perspective of sustainability: Feedstocks, products, and processes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15, 4042–4052. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G., Hong, C., Ma, Y., Du, M., Zhang, Y., Luo, H., Chen, B., Pan, X. 2022.Sargassum Horneri based carbon doped TiO2 and its aquatic naphthalene photo-degradation under sunlight irradiation. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 9 7, 1267-1274.

- Bian, J., Huang, C., Wang, L., Hung, T. F., Daoud, W. A. , & Zhang, R. Carbon dot loading and tio2 nanorod length dependence of photoelectrochemical properties in carbon dot/tio2 nanorod array nanocomposites. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces 2014, 6, 4883–90.

- Zhang, L. Y., Han, Y. L., Yang, J. J., Deng, S. L. , & Wang, B. Y. Construction and photocatalysis of carbon quantum dots/layered mesoporous titanium dioxide (cqds/lm-tio2) composites. Applied Surface Science 2021, 546, 149089.

- Natarajan, S., Bajaj, H., & Tayade, R. (2018) Recent advances based on the synergetic effect of adsorption for removal of dyes from waste water using photocatalytic process. Journal of Environmental Sciences 30, 201–222.

- Chen, J., Shu, J., Anqi, Z., Juyuan, H., Yan, Z., & Chen, J. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots/TiO2 nanocomposite for photo-degradation of Rhodamine B and cefradine. Diamond and Related Materials 2016, 70, 137–144.

- He, C., Peng, L., Lv, L., Cao, Y., Tu, J., Huang, W., & Zhang, K. In situ growth of carbon dots on TiO2 nanotube arrays for PEC enzyme biosensors with visible light response. RSC advances 2019, 9, 15084–15091.

- Chang, L., Ahmad, N., Zeng, G., Ray, A., & Zhang, Y. N, S co-doped carbon quantum dots/TiO2 composite for visible-light-driven photocatalytic reduction of Cr (VI). Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 108742.

- Peñas-Garzón, M., Gómez-Avilés, A., Bedia, J., Rodriguez, J. J., & Belver, C. Effect of activating agent on the properties of TiO2/activated carbon heterostructures for solar photocatalytic degradation of acetaminophen. Materials 2019, 12, 378.

- Baruah, M., Supong, A., Bhomick, P. C., Karmaker, R., Pongener, C., & Sinha, D. Batch sorption-photodegradation of Alizarin Red S using synthesized TiO2 /activated carbon nanocomposite: an experimental study and computer modelling. Nanotechnology for Environmental Engineering 2020, 5, 1–13.

- Marković, Z. M.,Kováčová, M., Jeremić, S.R., Nagy, Š, Milivojević, D. D., Kubat, P., Kleinová, A., Budimir, M.D., Mojsi, M.M., Stevanović, M.J., Annušová, A., Špitalský, Z., Marković, B. M. T. Highly efficient antibacterial polymer composites based on hydrophobic riboflavin carbon polymerized dots. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4070.

- Liu, J., Zhu, W., Yu, S., & Yan, X. Three dimensional carbogenic dots/TiO2 nanoheterojunctions with enhanced visible light-driven photocatalytic activity. Carbon 2014, 79, 369–379.

- Hu, C., Mu, Y., Li, M., & Qiu, J. Recent advances in the synthesis and applications of carbon dots. Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica 2019, 35, 572–590.

- , Li, H. J., Ou, N., Lyu, B., Gui, B., Tian, S., Qian, D., Wang, X., & Yang, J. Visible-light driven tio photocatalyst coated with graphene quantum dots of tunable nitrogen doping. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 24.

- Chang, L., Ahmad, N., Zeng, G., Ray, A., & Zhang, Y. N, S co-doped carbon quantum dots/TiO2 composite for visible-light-driven photocatalytic reduction of Cr (VI). Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 108742.

| Kinetic model | Parameters | Samples | ||

| CQD/TiO2 | CQD/TiO2 (dark) |

CQDs | ||

| Pseudo-first order |

k1x102/ (min-1) |

0.603 | 0.008 | 0.104 |

| R2 | 0.8968 | 0.8608 | 0.4932 | |

| Pseudo-second order |

k2x104/ (L·mg-1·min-1) |

5.642 | 0.447 | 0.552 |

| R2 | 0.7764 | 0.8480 | 0.5179 | |

| Double exponential | A1 | -41.89 | -29.56 | -28.14 |

| A2 | -41.89 | -29.56 | -28.14 | |

| k3 | 0.0588 | 0.0214 | 0.1529 | |

| k4 | 0.0588 | 0.0214 | 0.1529 | |

| R2 | -0.4477 | 0.2531 | 0.9150 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).