Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Muscle Tissue Samples

2.2. Paraffin Section Preparation and Analysis

2.3. RNA Sample Detection and Library Construction

2.4. Clustering and Quality Control of RNA-Seq Libraries

2.5. Analysis of Sequencing Data

3. Results

3.1. The Changes in the Area of Muscle Fibers of Rabbits’ Skeletal Muscle at Different Stages

3.2. Summarization of RNA-Seq

3.3. Differential Expression Analysis of mRNAs in Rabbit Skeletal Muscle

3.4. GO Enrichment and KEGG Pathway of DEGs in Thigh and Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

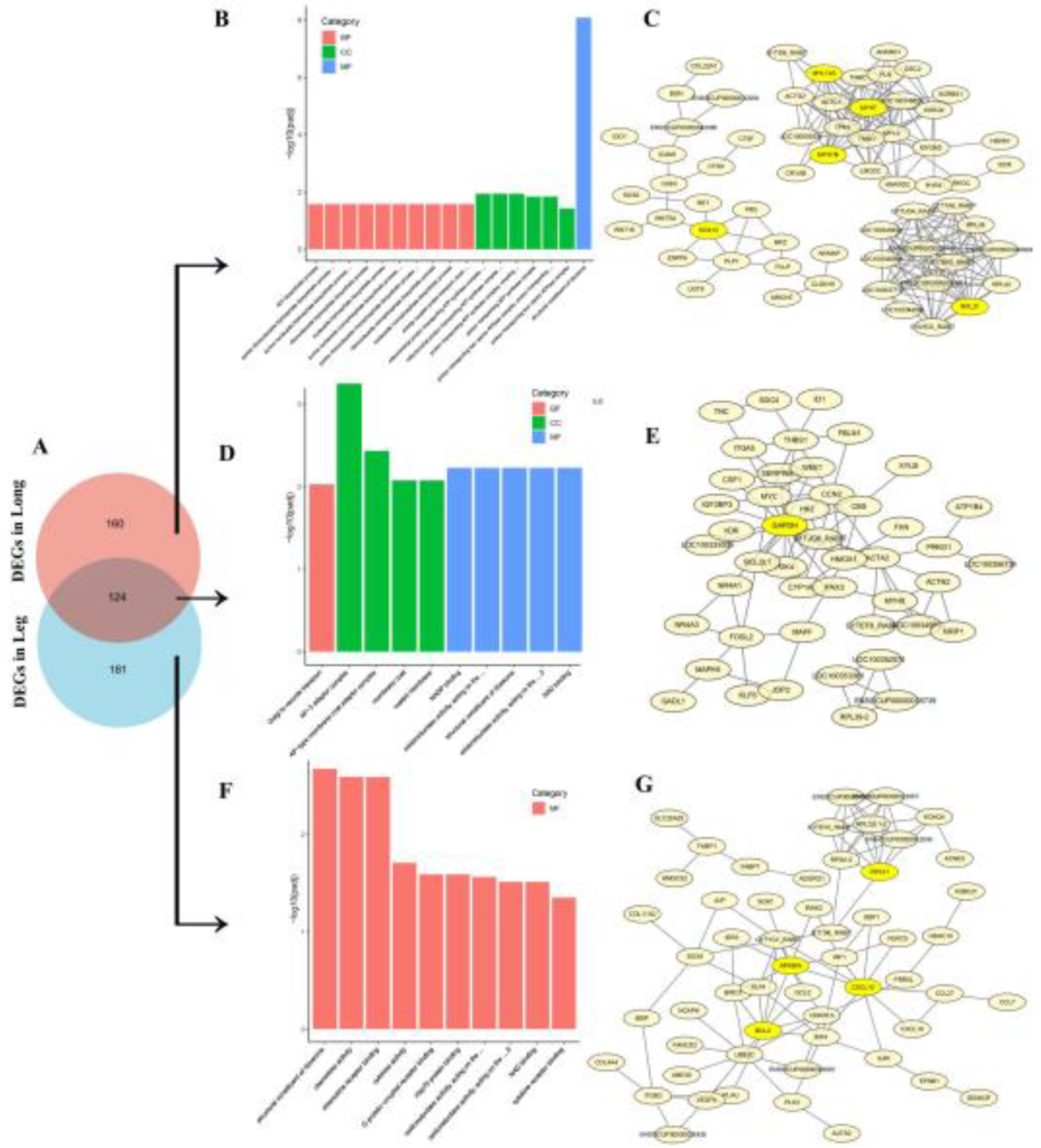

3.5. GO Enrichment, KEGG Pathway and PPI of Top-50 DEGs

3.6. The Analysis of Co-Expressive and Tissue-Specific Expressive DEGs in Thigh and Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ma | Sichuan linen rabbits |

| Ju | Checkered Giant rabbits |

| Leg | the thigh muscle |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| Long | the longissimus dorsi muscle |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatedehydrogenase |

| PGM1 | phosphoglucomutase 1 |

| IGF-1 | Insulin like growth factor 1 |

| SGK1 | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 |

| ACSS1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase short chain family member 1 |

| ALDOA | Aldolase, fructose-bisphosphate A |

| ACTN1 | Actinin alpha 1 |

| MYH10 | Myosin heavy chain 10 |

| HE | hematoxylin-eosin staining |

| CAS | Cross sectional area of muscle fibers |

| HCA | hierarchical cluster analysis |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

References

- Cullere, M.; Dalle Zotte, A. Rabbit meat production and consumption: State of knowledge and future perspectives. Meat Sci. 2018, 143, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Zotte, A.; Szendrő, Z. The role of rabbit meat as functional food. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, L.; Lei, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Y.; Zheng, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yang, C.; Mei, X.; et al. Identification of Long Non-Coding RNAs Related to Skeletal Muscle Development in Two Rabbit Breeds with Different Growth Rate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillies, M.-A.; Rau, A.; Aubert, J.; Hennequet-Antier, C.; Jeanmougin, M.; Servant, N.; Keime, C.; Marot, G.; Castel, D.; Estelle, J.; et al. A comprehensive evaluation of normalization methods for Illumina high-throughput RNA sequencing data analysis. Briefings Bioinform. 2012, 14, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, J.; Spacek, D.V.; Snyder, M. High-throughput sequencing technologies. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 586–597 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrdlickova, R.; Toloue, M.; Tian, B. RNA-Seq methods for transcriptome analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C, Huang, Y, Yang, Z, Ma, Y. ; Chaogetu, B.; Zhuoma, Z.; Chen, H. RNA-Seq Analysis Identifies Differentially Expressed Genes Insubcutaneous Adipose Tissuein Qaidamford Cattle, Cattle-Yak, and Angus Cattle. Animals (Basel) 2019, 9, 1077 [CrossRef].

- Paradis, F.; Yue, S.; Grant, J.R.; Stothard, P.; Basarab, J.A.; Fitzsimmons, C. Transcriptomic analysis by RNA sequencing reveals that hepatic interferon-induced genes may be associated with feed efficiency in beef heifers1. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 3331–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wei, X.; Yang, J.; Dong, D.; Huang, Y.; Lan, X.; Plath, M.; Lei, C.; Qi, X.; Bai, Y.; et al. Developmental transcriptome profiling of bovine muscle tissue reveals an abundant GosB that regulates myoblast proliferation and apoptosis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 32083–32100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Hou, Y.; Wu, H.; Miao, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, J.; Brameld, J.M.; Parr, T.; Zhao, S. Transcriptome analysis of mRNA and miRNA in skeletal muscle indicates an important network for differential Residual Feed Intake in pigs. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.-K.; Lee, S.; Jung, M.H. RNA-Seq Analysis Reveals a Negative Role of KLF16 in Adipogenesis. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0162238–e0162238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keel, B.N.; Zarek, C.M.; Keele, J.W.; Kuehn, L.A.; Snelling, W.M.; Oliver, W.T.; Freetly, H.C.; Lindholm-Perry, A.K. RNA-Seq Meta-analysis identifies genes in skeletal muscle associated with gain and intake across a multi-season study of crossbred beef steers. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareek, C.S.; Sachajko, M.; Jaskowski, J.M.; Herudzinska, M.; Skowronski, M.; Domagalski, K.; Szczepanek, J.; Czarnik, U.; Sobiech, P.; Wysocka, D.; et al. Comparative Analysis of the Liver Transcriptome among Cattle Breeds Using RNA-seq. Veter- Sci. 2019, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, P.; Zhou, K.; He, M.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, T.; Xie, K.; Dai, G.; et al. Study on the transcriptome for breast muscle of chickens and the function of key gene RAC2 on fibroblasts proliferation. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballan, M.; Bovo, S.; Bertolini, F.; Schiavo, G.; Schiavitto, M.; Negrini, R.; Fontanesi, L. Population genomic structures and signatures of selection define the genetic uniqueness of several fancy and meat rabbit breeds. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2023, 140, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.L.; Leinwand, L.A. Postnatal Myosin Heavy Chain Isoform Expression in Normal Mice and Mice Null for IIb or IId Myosin Heavy Chains. Dev. Biol. 2001, 229, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeandro, V.; Notarnicola, A.; Bianco, A.; Tafuri, S.; Russo, L.; Pesce, V.; Moretti, B.; Petruzzella, V. ACTN3/ACE genotypes and mitochondrial genome in professional soccer players’ performance. . 2017, 31, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Nanaei, H.A.; Wei, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Dai, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Shao, J. Comparative Transcriptome Profiling Analysis Uncovers Novel Heterosis-Related Candidate Genes Associated with Muscular Endurance in Mules. Animals 2020, 10, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaosap, C.; Sitthigripong, R.; Sivapirunthep, P.; Pungsuk, A.; Adeyemi, K.D.; Sazili, A.Q. Myosin heavy chain isoforms expression, calpain system and quality characteristics of different muscles in goats. Food Chem. 2020, 321, 126677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M.; Smith, T.P.; Bass, J.J. Mutations in myostatin (GDF8) in Double-Muscled Belgian Blue and Piedmontese Cattle. Genome Res. 1997, 7, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboalola, D.; Han, V.K.M. Different Effects of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-2 on Myogenic Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xiao, W.; Qin, X.; Cai, G.; Chen, H.; Hua, Z.; Cheng, C.; Li, X.; Hua, W.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, L.; Dai, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Qian, C.; Yao, J.; Bi, Y. Myostatin regulates fatty acid desaturation and fat deposition through MEF2C/miR222/SCD5 cascade in pigs. Commun Biol. 2020, 3, 612 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Feng, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Shen, W. Transcriptomic regulatory analysis of skeletal muscle development in landrace pigs. Gene 2024, 915, 148407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yue, F.; Kuang, S. Muscle Histology Characterization Using H&E Staining and Muscle Fiber Type Classification Using Immunofluorescence Staining. Bio-Protocol 2017, 7, e2279–e2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Morris, J.H.; Cook, H.; Kuhn, M.; Wyder, S.; Simonovic, M.; Santos, A.; Doncheva, N.T.; Roth, A.; Bork, P.; Jensen, L.J.; von Mering, C. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D362–D368 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammit, P.S. Function of the myogenic regulatory factors Myf5, MyoD, Myogenin and MRF4 in skeletal muscle, satellite cells and regenerative myogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 72, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, T.; Kemter, E.; Flenkenthaler, F.; Klymiuk, N.; Otte, K.A.; Blutke, A.; Krause, S.; Walter, M.C.; Wanke, R.; Wolf, E.; et al. Progressive muscle proteome changes in a clinically relevant pig model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.-C.; Park, H.-B.; Ahn, J.S.; Han, S.-H.; Lee, J.-B.; Lim, H.-T.; Yoo, C.-K.; Jung, E.-J.; Kim, D.-H.; Sun, W.-S.; et al. A functional regulatory variant of MYH3 influences muscle fiber-type composition and intramuscular fat content in pigs. PLOS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesek, M.; Murawska, D.; Otrocka-Domagała, I.; Michalska, K.; Zawacka, M. Effects of caponization and age on the histology, lipid localization, and fiber diameter in muscles from Leghorn cockerels. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqin, Q.; Nishiumi, T.; Yamada, T.; Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Wu, R.; Borjigin, G. Relationships among muscle fiber type composition, fiber diameter and MRF gene expression in different skeletal muscles of naturally grazing Wuzhumuqin sheep during postnatal development. Anim Sci J. 2017, 88, 2033–2043 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhu, C.; Jing, J.; Ling, Y.; Qin, S.; Wang, J.; Zha, L.; Liu, Y.; Fang, F. Morphological changes and functional circRNAs screening of rabbit skeletal muscle development. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Morita, T.; Takasu, H.; Kuroki, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Hiraba, K.; Goto, S. Histochemical study of rabbit medial pterygoid muscle during postnatal development. Odontology 2016, 105, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, P.; Zhou, K.; He, M.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, T.; Xie, K.; Dai, G.; et al. Study on the transcriptome for breast muscle of chickens and the function of key gene RAC2 on fibroblasts proliferation. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keel, B.N.; Zarek, C.M.; Keele, J.W.; Kuehn, L.A.; Snelling, W.M.; Oliver, W.T.; Freetly, H.C.; Lindholm-Perry, A.K. RNA-Seq Meta-analysis identifies genes in skeletal muscle associated with gain and intake across a multi-season study of crossbred beef steers. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, C.; Yu, C.; Chen, M.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Y. Transcriptome analysis of breast muscle and liver in full-sibling hybrid broilers at different ages. Gene 2022, 842, 146801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Cai, Z.; Wei, C.; Ma, X.; Yu, B.; Fu, X.; Zhang, T.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, J. Functional identification of PGM1 in the regulating development and depositing of inosine monophosphate specific for myoblasts. Front. Veter- Sci. 2023, 10, 1276582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, B.O.S.; Zanella, B.T.T.; Perez, E.S.; Mareco, E.A.; Blasco, J.; Dal-Pai-Silva, M.; de la Serrana, D.G. Amino Acids and IGF1 Regulation of Fish Muscle Growth Revealed by Transcriptome and microRNAome Integrative Analyses of Pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus) Myotubes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres-Mateos, E.; Brinkmeier, H.; Burks, T.N.; Mejias, R.; Files, D.C.; Steinberger, M.; Soleimani, A.; Marx, R.; Simmers, J.L.; Lin, B.; et al. Activation of serum/glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 (SGK1) is important to maintain skeletal muscle homeostasis and prevent atrophy. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012, 5, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Hu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J. Identifying Acss1, Mtfp1 and Oxct1 as key regulators and promising biomarkers of sarcopenia in various models. Gene 2023, 896, 148053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, Z.; Wu, A.; Pan, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, X. Muscle transcriptome analysis provides new insights into the growth gap between fast- and slow-growing Sinocyclocheilus grahami. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1217952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondelle, J.; Tallapaka, K.; Seto, J.T.; Ghassemian, M.; Clark, M.; Laitila, J.M.; Bournazos, A.; Singer, J.D.; Lange, S. Cullin-3–dependent deregulation of ACTN1 represents a pathogenic mechanism in nemaline myopathy. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Jiang, L.; Song, W.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Yan, X. Skeletal muscle feature of different populations in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea): from an epigenetic point of view. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1403861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredient | Content (%) |

|---|---|

| Alfalfa meal | 34.4 |

| Corn | 21.5 |

| Soya bean meal | 13.5 |

| Bran | 22.5 |

| Wheat | 5 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate | 0.9 |

| Mountain flour | 0.7 |

| NaCl | 0.5 |

| The vitamin premix 1 | 0.5 |

| The mineral Premix 2 | 0.5 |

| Total | 100.00 |

| Nutrient level 3 | Content |

| Digestible energy, Mcal/kg | 10.45 |

| Crude protein, % | 17.07 |

| Crude fibre, % | 10.92 |

| Lysine, % | 0.84 |

| Methionine + Cystine, % | 0.62 |

| Calcium, % | 1.01 |

| Phosphorus, % | 0.65 |

| Neutral detergent fiber, % | 27.22 |

| Acid detergent fiber, % | 14.29 |

| Sample | Clean Reads | Clean Bases | Mapped ratio | Uni-mapped | Q30 | GC(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma_Leg_1 | 42394110 | 6.36G | 88.86% | 84.39% | 94.47 | 54.55 |

| Ma_Leg_2 | 41266572 | 6.19G | 90.21% | 85.58% | 93.77 | 53.29 |

| Ma_Leg_3 | 42051878 | 6.31G | 89.78% | 85.37% | 94.02 | 53.67 |

| Ju_Leg_1 | 42406862 | 6.36G | 87.94% | 83.85% | 94.08 | 55.13 |

| Ju_Leg_2 | 41415140 | 6.21G | 89.51% | 85.25% | 95.2 | 54.2 |

| Ju_Leg_3 | 41681174 | 6.25G | 89.35% | 84.76% | 94.13 | 53.93 |

| Ma_Long_1 | 46907154 | 7.04G | 84.05% | 79.4% | 94.66 | 54.42 |

| Ma_Long_2 | 43304158 | 6.5G | 86.49% | 82.52% | 93.74 | 55.95 |

| Ma_Long_3 | 39350026 | 5.9G | 87.75% | 83.68% | 93.9 | 55.46 |

| Ju_Long_1 | 44311234 | 6.65G | 87.66% | 83.11% | 95.35 | 54.63 |

| Ju_Long_2 | 42472108 | 6.37G | 82.41% | 78.17% | 95.71 | 57.76 |

| Ju_Long_3 | 42970742 | 6.45G | 87.9% | 83.47% | 95.88 | 55.27 |

| average | 42544263.17 | 6.51G | 87.66% | 94.58 | 54.86 |

| Category | GOID | Description |

|---|---|---|

| BP | GO:0014812 | muscle cell migration |

| BP | GO:0043069 | negative regulation of programmed cell death |

| BP | GO:0014909 | smooth muscle cell migration |

| CC | GO:0030017 | sarcomere |

| CC | GO:0030016 | myofibril |

| CC | GO:0032432 | actin filament bundle |

| MF | GO:0043177 | organic acid binding |

| MF | GO:0005516 | calmodulin binding |

| MF | GO:0050661 | NADP binding |

| MF | GO:0005509 | calcium ion binding |

| KEGG | KEGGID | Description |

| ocu00010 | Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | |

| ocu04066 | HIF-1 signaling pathway | |

| ocu04151 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | |

| ocu04068 | FoxO signaling pathway | |

| ocu04010 | MAPK signaling pathway |

| Category | GOID | Description |

|---|---|---|

| BP | GO:0014812 | muscle cell migration |

| BP | GO:0006954 | inflammatory response |

| BP | GO:0014909 | smooth muscle cell migration |

| BP | GO:0061061 | muscle structure development |

| CC | GO:0015629 | actin cytoskeleton |

| CC | GO:0043292 | contractile fiber |

| CC | GO:0030016 | myofibril |

| CC | GO:0016459 | myosin complex |

| MF | GO:0005509 | calcium ion binding |

| MF | GO:0001968 | fibronectin binding |

| MF | GO:0051015 | actin filament binding |

| KEGG | KEGGID | Description |

| ocu04066 | HIF-1 signaling pathway | |

| ocu00010 | Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | |

| ocu04810 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | |

| ocu03320 | PPAR signaling pathway |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).