Submitted:

17 August 2024

Posted:

19 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Determination of IMF Content

2.4. Histology

2.5. Total RNA Extraction, Library Construction and Sequencing

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.7. Data Processing

2.7.1. Quality Control, Transcript Assembly and Splicing

2.7.2. Sequence Data Mining and Analysis

2.7.3. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

2.7.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

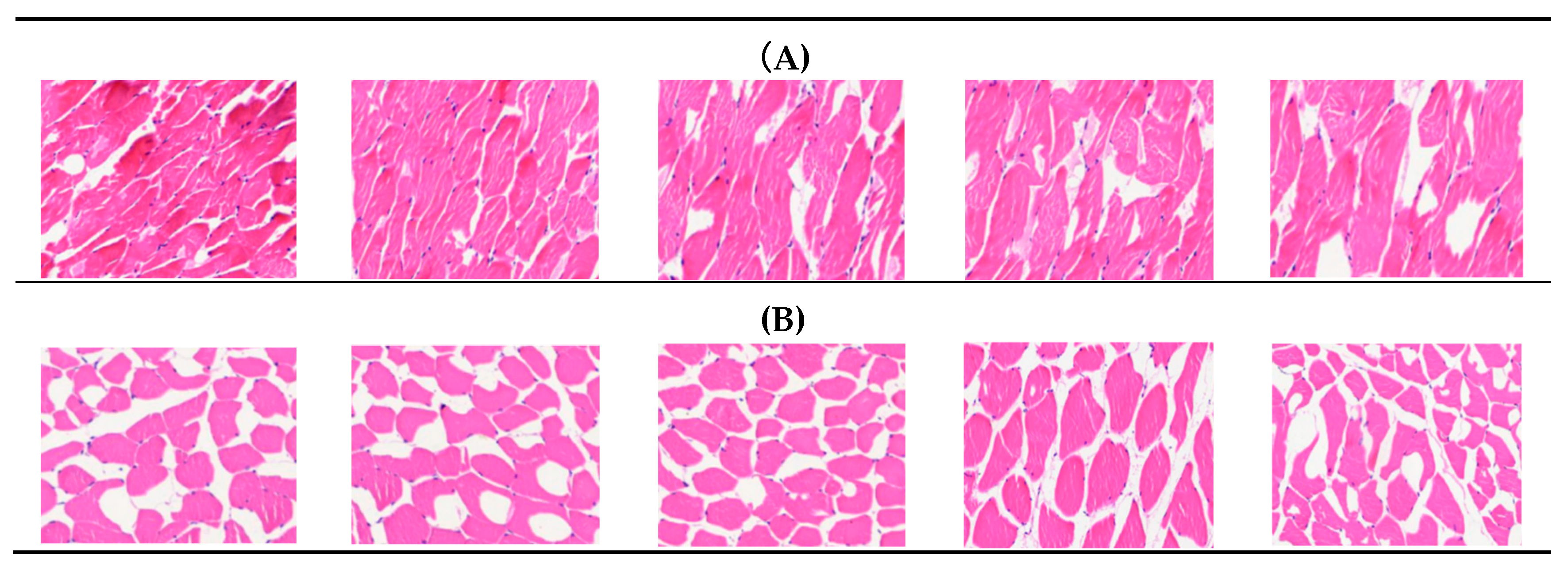

3.1. Comparison of IMF Content and Morphological Observation of the Longissimus Dorsi Muscle in Two Groups

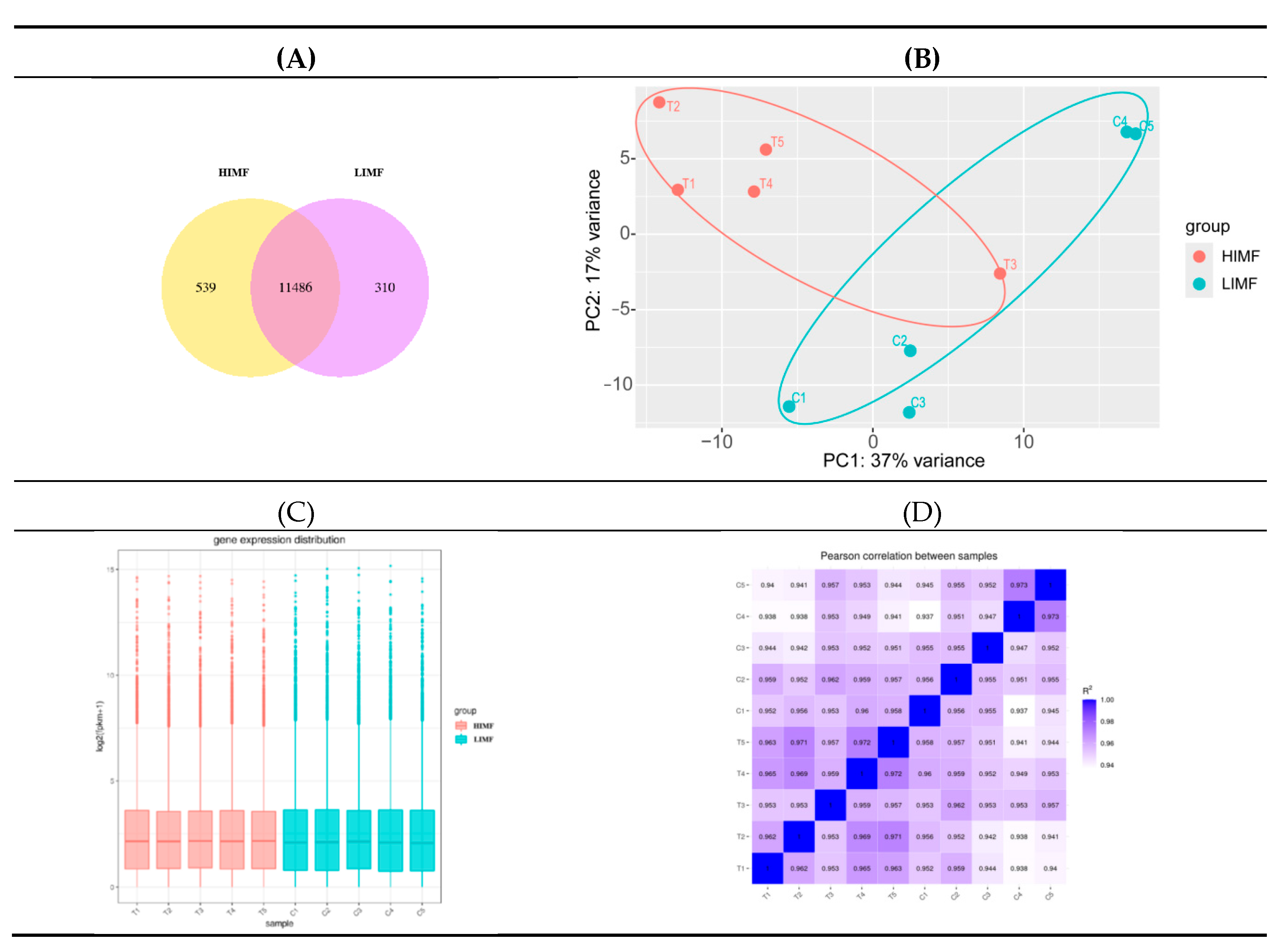

3.2. Transcriptome Sequencing Data Analysis

3.3. Quantitative Analysis of Transcriptome Sequencing

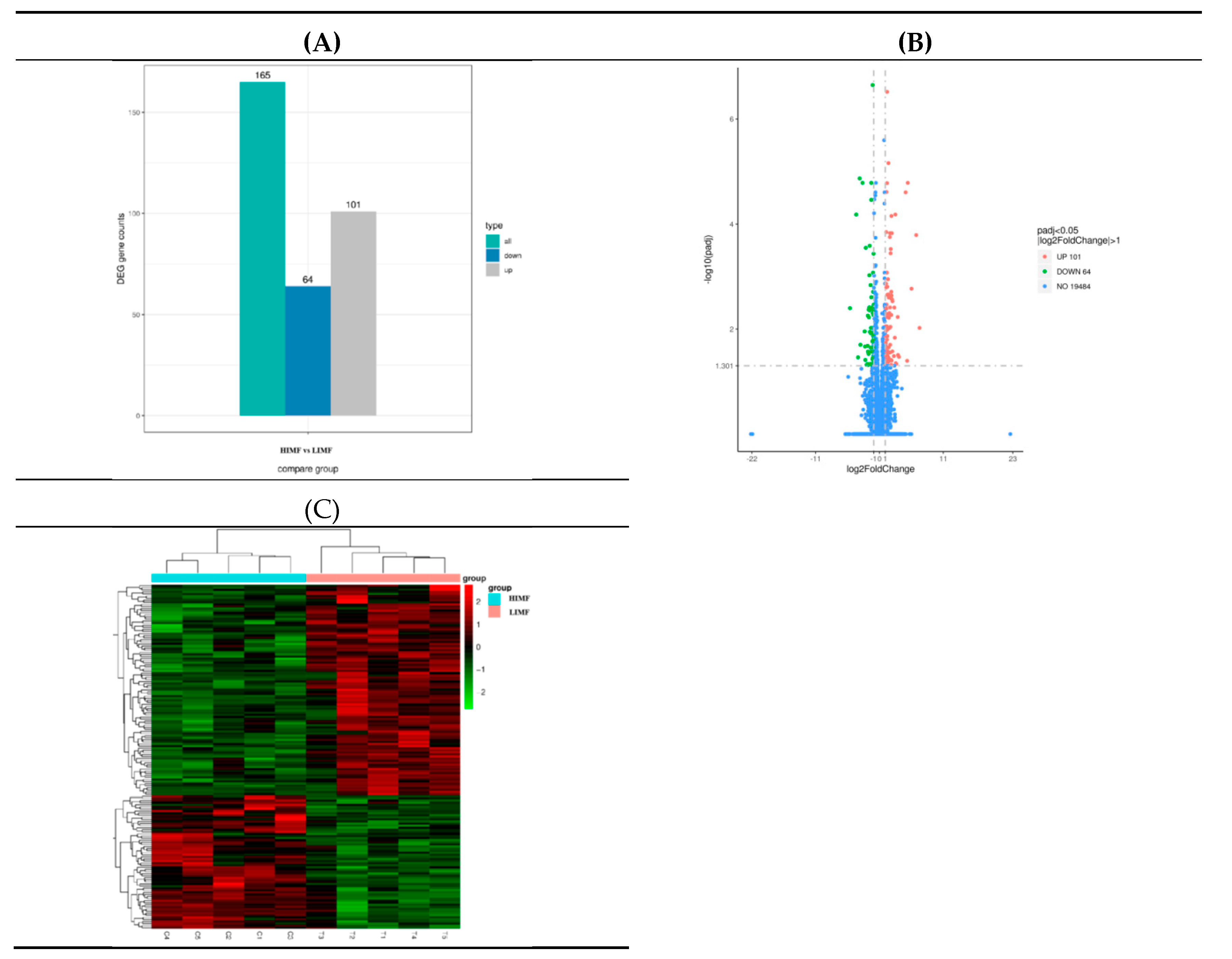

3.4. Transcriptome Sequencing of Differentially Expressed Genes

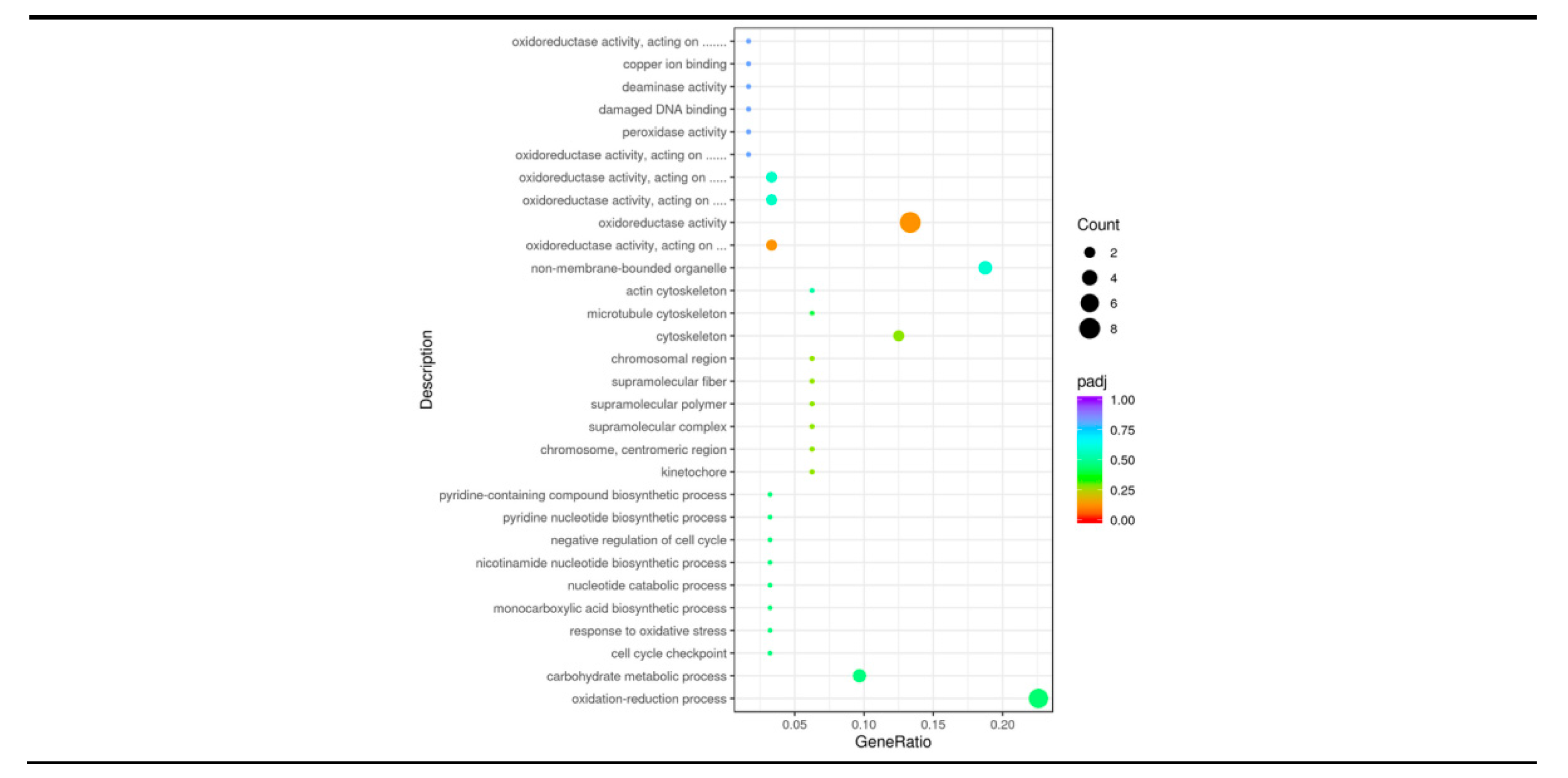

3.5. GO Enrichment Analysis

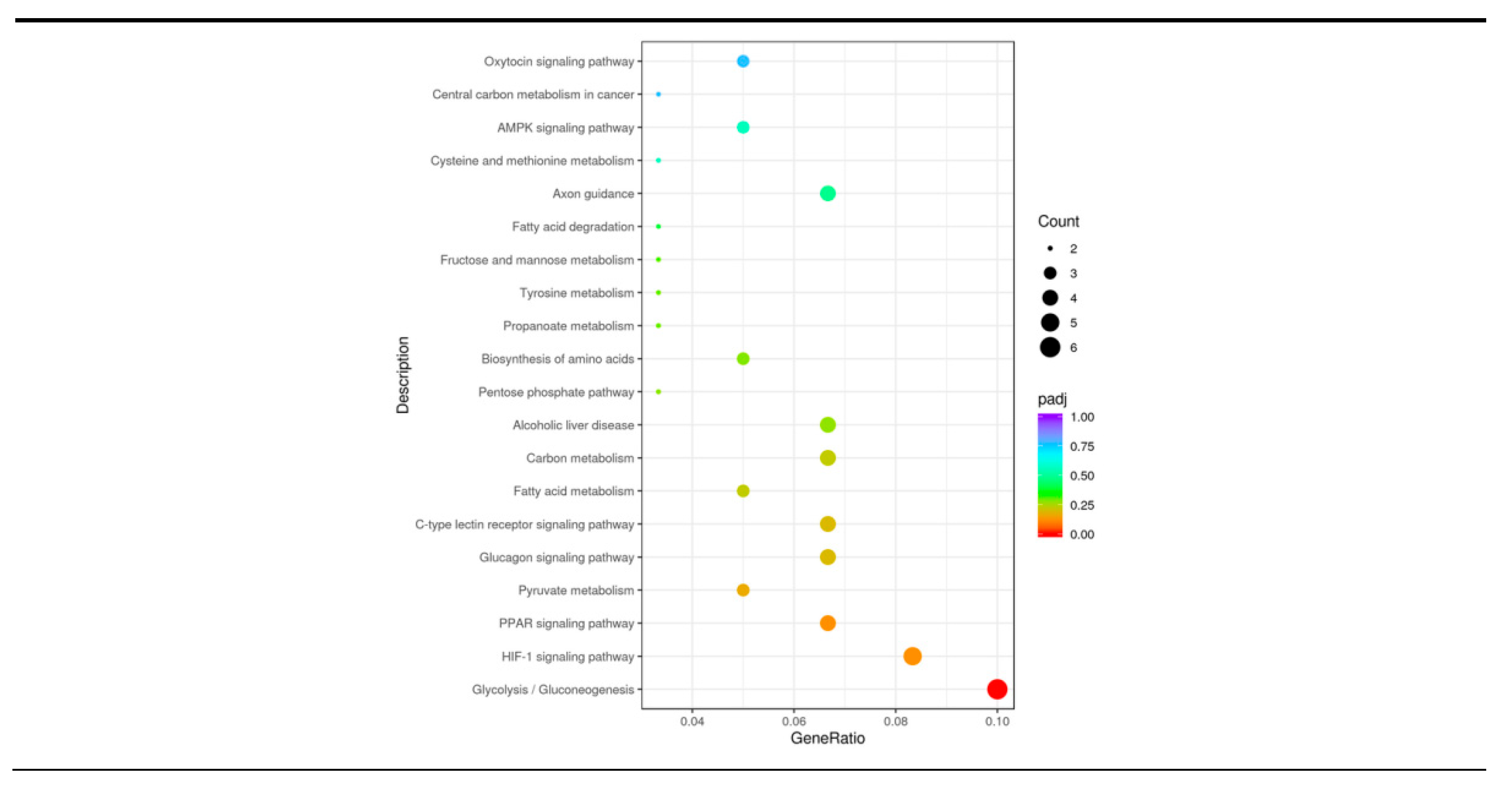

3.6. KEGG Pathway Analysis

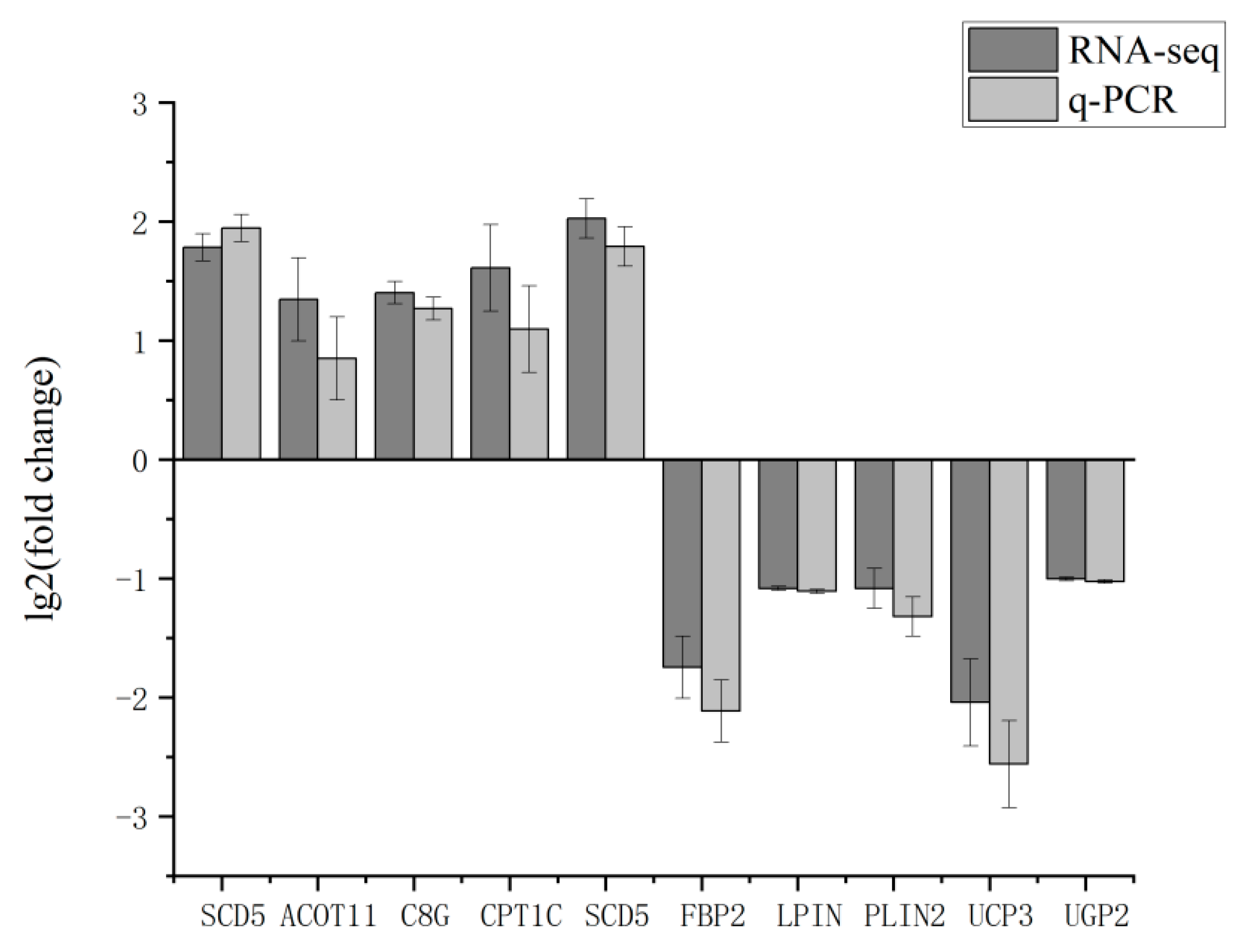

3.7. RT-qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, T.; Yan, M.; Zhai, M.; Huang, X. Whole genome resequencing reveals the genetic contribution of Kazakh and Swiss Brown Cattle to a population of Xinjiang Brown Cattle. Gene 2022, 839, 146725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.M.; Ma, Z.; Yuan, L.X.; Fu, H.Y.; Zhang, J.S.; Zhou, J.Z.; Li, H.B. Efficacy evaluation of population breeding of Xinjiang browncattle (meat breed lines). Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine 2024, 56, 1–6. (in China). [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.M.; Zhang, J.S.; Li, H.B.; Li, N.; Du, W.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y. Comparative study on carcass traits and meat quality of different month old of Xinjiang Brown Cattle steers. China Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine 2015, 42, 2954–2960. (in China). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickworth, C.L.; Loerch, S.C.; Velleman, S.G.; Pate, J.L.; Poole, D.H.; Fluharty, F.L. Adipogenic differentiation state-specific gene expression as related to bovine carcass adiposity. J Anim Sci. 2011, 89, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Huang, Y.; Das, A.K.; Yang, Q.; Duarte, M.S.; Dodson, M.V.; Zhu, M.J. Meat Science and Muscle Biology Symposium: manipulating mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation to optimize performance and carcass value of beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2013, 91, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Han, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Q. Metagenomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal the differences and associations between the gut microbiome and muscular genes in ang-us and Chinese Simmental Cattle. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 815915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y. Transcription factors regulate adipocyte differentiation in beef cattle. Anim Genet 2020, 51, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.M.; Li, S.X.; Li, X.S.; Li, C.Y. Transcriptome studies with the third-generation sequencing technology. Life Science Instruments (in China). 2018, 16, 114–121+113. [Google Scholar]

- Berton, M.P.; Fonseca, L.F.; Gimenez, D.F.; Utembergue, B.L.; Cesar, A.S.; Coutinho, L.L.; de Lemos, M.V.; Aboujaoude, C.; Pereira, A.S.; Silva, R.M.; Stafuzza, N.B.; Feitosa, F.L.; Chiaia, H.L.; Olivieri, B.F.; Peripolli, E.; Tonussi; Stafuzza, N. B.; Feitosa, F.L.; Chiaia, H.L.; Olivieri, B.F.; Peripolli, E.; Tonussi, R.L.; Gordo, D.M.; Espigolan, R.; Ferrinho, A.M.; Mueller, L.F.;......Baldi, F. Gene expression profile of intramuscular muscle in Nellore cattle with extreme values of fatty acid. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, A.S.; Regitano, L.C.; Koltes, J.E.; Fritz-Waters, E.R.; Lanna, D.P.; Gasparin, G.; Mourão, G.B.; Oliveira, P.S.; Reecy, J.M.; Coutinho, L.L. Putative regulatory factors associated with intramuscular fat content. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0128350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essén-Gustavsson, B.; Karlsson, A.; Lundström, K.; Enfält, A.C. Intramuscular fat and muscle fibre lipid contents in halothane-gene-free pigs fed high or low protein diets and its relation to meat quality. Meat Sci. 1994, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, T.; Hattori, A.; Takahashi, K. Structural changes in intramuscular connective tissue during the fattening of Japanese black cattle: effect of marbling on beef tenderization. Anim Sci. 1999, 77, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMauro, S.; Schon, E.A. Mitochondrial disorders in the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008, 31, 91–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, D.J. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, regulation of exocytosis and their relevance to neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem 2008, 104, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, M.; Guan, L.L.; Zhang, B.; Dodson, M.V.; Okine, E.; Moore, S.S. Adipogenesis of bovine perimuscular preadipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008, 366, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, C.; Tordjman, J.; Glorian, M.; Duplus, E.; Chauvet, G.; Quette, J.; Beale, E.G.; Antoine, B. Fatty acid recycling in adipocytes: a role for glyceroneogenesis and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003, 31, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, V.E.; Frasson, D.; Kawashita, N.H. Several agents and pathways regulate lipolysis in adipocytes. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1631–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaubert, A.M.; Penot, G.; Niang, F.; Durant, S.; Forest, C. Rapid nitration of adipocyte phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase by leptin reduces glyceroneogenesis and induces fatty acid release. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e40650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Yan, H.; Xia, M.; Chang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, X.; Lu, Y.; Bian, H.; Li, X.; Gao, X. Metformin attenuates triglyceride accumulation in HepG2 cells through decreasing stearyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1 expression. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmani Izadi, M.; Naserian, A.A.; Nasiri, M.R.; Majidzadeh Heravi, R.; Valizadeh, R. Evaluation of SCD and FASN gene expression in Baluchi, Iran-Black, and Arman Sheep. Rep Biochem Mol Biol. 2016, 5, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sinner, D.I.; Kim, G.J.; Henderson, G.C.; Igal, R.A. StearoylCoA desaturase-5: a novel regulator of neuronal cell proliferation and differentiation. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e39787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Burhans, M.S.; Flowers, M.T.; Ntambi, J.M. Hepatic oleate regulates liver stress response partially through PGC-1α during high-carbohydrate feeding. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, R.; McFadden, J.W.; Lengi, A.J.; Corl, B.A.; Chouinard, P.Y. Effects of intravenous infusion of trans-10, cis-12 18:2 on mammary lipid metabolism in lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 5167–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igal, R.A.; Sinner, D.I. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 5 (SCD5), a Δ-9 fatty acyl desaturase in search of a function. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2021, 1866, 158840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xiao, W.; Qin, X.; Cai, G.; Chen, H.; Hua, Z.; Cheng, C.; Li, X.; Hua, W.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, L.; Dai, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Qian, C.; Yao, J.; Bi, Y. Myostatin regulates fatty acid desaturation and fat deposition through MEF2C/miR222/SCD5 cascade in pigs. Commun Biol. 2020, 3, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.B.; Guan, J.Q.; Zhou, X.J.; Liao, X.P.; Guo, D.S.; Luo, X.L. Correlation Analysis of Intramuscular Fat Content and Fat Metabolism Related Gene Expression in Different Muscle Tissues of Yaks. Chinese Journal of Animal Science. 2020, 56, 73–77. (in China) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.H.; Bai, W.Z.; Li, Z.M.; Chen, H.B.; Bi, Z.T. Studies on the effect of pig SCD5 gene deletion on fatty acid composition. Chinese Journal of Animal Science. 2023, 59, 224–231. (in China). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shang, L.; Deng, S.; Li, P.; Chen, K.; Gao, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, J. Peroxisomal oxidation of erucic acid suppresses mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation by stimulating malonyl-CoA formation in the rat liver. J Biol Chem. 2020, 295, 10168–10179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, A.; Dohi, H.; Egashira, Y.; Hirai, S. Erucic acid derived from rosemary regulates differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts/adipocytes via suppression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ transcriptional activity. Phytother Res. 2020, 34, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa-Mansergas, X.; Fadó, R.; Atari, M.; Mir, J.F.; Muley, H.; Serra, D.; Casals, N. CPT1C promotes human mesenchymal stem cells survival under glucose deprivation through the modulation of autophagy. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Ohkura, K.; Yamazaki, N.; Takiguchi, Y.; Shinohara, Y. Comparison of the catalytic activities of three isozymes of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 expressed in COS7 cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014, 172, 1486–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra, A.Y.; Gratacós, E.; Carrasco, P.; Clotet, J.; Ureña, J.; Serra, D.; Asins, G.; Hegardt, F.G.; Casals, N. CPT1c is localized in endoplasmic reticulum of neurons and has carnitine palmitoyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283, 6878–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucci, S.; Zonetti, M.J.; Fisco, T.; Polidoro, C.; Bocchinfuso, G.; Palleschi, A.; Novelli, G.; Spagnoli, L.G.; Mazzarelli, P. Carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1A (CPT1A): a new tumor specific target in human breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19982–19996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaugg, K.; Yao, Y.; Reilly, P.T.; Kannan, K.; Kiarash, R.; Mason, J.; Huang, P.; Sawyer, S.K.; Fuerth, B.; Faubert, B.; Kalliomäki, T.; Elia, A.; Luo, X.; Nadeem, V.; Bungard, D.; Yalavarthi, S.; Growney, J.D.; Wakeham, A.; Moolani, Y.; Silvester, J.; Mak, T.W. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C promotes cell survival and tumor growth under conditions of metabolic stress. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cheng, Y.; Su, D.; Gong, B.; He, X.; Zhou, X.; Pang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Z. Cpt1c regulated by AMPK promotes papillary thyroid carcinomas cells survival under metabolic stress conditions. J Cancer. 2017, 8, 3675–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guan, L.; Jiao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, M.; Bi, H. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C reverses cellular senescence of MRC-5 fibroblasts via regulating lipid accumulation and mitochondrial function. J Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Khan, S.A.; Peng, L.J.; Lange, A.J. Roles for fructose-2,6-bisphosphate in the control of fuel metabolism: beyond its allosteric effects on glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2006, 46, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzugaj, A. Localization and regulation of muscle fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, the key enzyme of glyconeogenesis. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2006, 46, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Xing, R.; Pan, Y.; Li, W.; Cui, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y. Decreased fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase-2 expression promotes glycolysis and growth in gastric cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2013, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, I.; Suryana, E.; Small, L.; Quek, L.E.; Brandon, A.E.; Turner, N.; Cooney, G.J. Fructose bisphosphatase 2 overexpression increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J Endocrinol. 2018, 237, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, L. Hormonal and Metabolite Regulation of Hepatic Glucokinase. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016, 36, 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rukkwamsuk, T.; Wensing, T.; Geelen, M.J. Effect of fatty liver on hepatic gluconeogenesis in periparturient dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | mRNA accession number | Primer sequences(5'~3') | Product size |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | NM_173979.3 | Forward:AAGTACCCCATTGAGCACGG Reverse:TCCTTGATGTCACGGACGATTT |

189 bp |

| SEC14L5 | NM_001191259.3 | Forward:CCACAAAGGCAAGATCCCCA Reverse:AGCTCAAGGACTGACACAGC |

104 bp |

| C8G | NM_001110076.2 | Forward:TCCCCTATCAGCACCATCCA Reverse:GCAGATTCCATCCAGCTTTCG |

198 bp |

| CPT1C | XM_002695120.6 | Forward:GGCTTCCGACCCTCACTGAC; Reverse:CAGAAACGGGAGAGATGCCTT |

116 bp |

| ACOT11 | NM_001103275.2 | Forward:ATCCAGACTGTTGGAAATCACCT Reverse:CTCGCCATCTGCCATGTTGT |

111 bp |

| SCD5 | NM_001076945.1 | Forward:TGGGTGCCATTGGTGAAGGT Reverse:CCCAGCCAACACATGAAGTC |

124 bp |

| FBP2 | NM_001046164.2 | Forward:TTCATGCTTGACCCAGCTCTT Reverse:CCTCCATAGACAAGGGTGCG |

230 bp |

| UCP3 | NM_174210.1 | Forward:CCCAACATCACGAGGAATGC Reverse:CAGGGGAAGTTGTCGGTGAG |

107 bp |

| PLIN2 | NM_173980.2 | Forward:CTCCATTCCGCCTTCAACCT Reverse:ACGTGACTCAATGTGCTCAG |

171 bp |

| UGP2 | NM_174212.2 | Forward:TGCGGATGTAAAGGGTGGGA Reverse:CATGCGCTTTTGGCACTTGA |

83 bp |

| LPIN1 | NM_001206156.2 | Forward:TCTTCCCACTTCCACGCTTC Reverse:ATCCGCAGATTTGCTGACCA |

90 bp |

| Item1 | IMF content (%) | Minimum (%) | Maximum (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIMF | 6.996±0.723A | 5.863 | 7.824 | 0.002 |

| LIMF | 4.790±0.783B | 3.874 | 5.624 |

| sample | Raw reads | Raw bases | Clean reads | Clean bases | Error rate | Q20 | Q30 | GC pct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 43246440 | 6.49G | 42439552 | 6.37G | 0.03 | 97.81 | 93.85 | 51.02 |

| T2 | 43426076 | 6.51G | 42377682 | 6.36G | 0.03 | 97.87 | 94.04 | 52.11 |

| T3 | 41992442 | 6.3G | 41202940 | 6.18G | 0.02 | 98.03 | 94.47 | 52.4 |

| T4 | 41644788 | 6.25G | 40126880 | 6.02G | 0.02 | 98.02 | 94.46 | 52.64 |

| T5 | 48098022 | 7.21G | 46682976 | 7.0G | 0.03 | 97.9 | 94.16 | 51.8 |

| C1 | 42494264 | 6.37G | 41037266 | 6.16G | 0.03 | 97.9 | 94.1 | 54.01 |

| C2 | 43497090 | 6.52G | 42302406 | 6.35G | 0.02 | 98.03 | 94.44 | 51.74 |

| C3 | 46125528 | 6.92G | 43760976 | 6.56G | 0.02 | 97.95 | 94.24 | 52.16 |

| C4 | 48924916 | 7.34G | 47173470 | 7.08G | 0.02 | 98.08 | 94.58 | 50.79 |

| C5 | 47427100 | 7.11G | 45659038 | 6.85G | 0.02 | 98.07 | 94.53 | 51.84 |

| Sample | Total reads | Total map | Map rate | Unique map | Unique map rate | Multi map | Multi map rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 42439552 | 40217936 | 94.77% | 39141933 | 92.23% | 1076003 | 2.54% |

| T2 | 42377682 | 40157154 | 94.76% | 38944182 | 91.9% | 1212972 | 2.86% |

| T3 | 41202940 | 39045874 | 94.76% | 37817486 | 91.78% | 1228388 | 2.98% |

| T4 | 40126880 | 38521569 | 96.0% | 37350423 | 93.08% | 1171146 | 2.92% |

| T5 | 46682976 | 44779474 | 95.92% | 43397543 | 92.96% | 1381931 | 2.96% |

| C1 | 41037266 | 39309911 | 95.79% | 38015521 | 92.64% | 1294390 | 3.15% |

| C2 | 42302406 | 40332401 | 95.34% | 39075620 | 92.37% | 1256781 | 2.97% |

| C3 | 43760976 | 40739851 | 93.10% | 39403210 | 90.04% | 1336641 | 3.05% |

| C4 | 47173470 | 44649391 | 94.65% | 43182346 | 91.54% | 1467045 | 3.11% |

| C5 | 45659038 | 43293569 | 94.82% | 41735269 | 91.41% | 1558300 | 3.41% |

| KEGG id | KEGG description | P-value | Upregulated genes | Downregulated genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bta04152 | AMPK signaling pathway | 0.0710 | FBP2; SCD5 | CPT1C |

| bta04921 | Oxytocin signaling pathway | 0.1093 | RGS2; PTGS2 | NFATC3 |

| bta05230 | Central carbon metabolism in cancer | 0.1063 | ENSBTAG00000032217; LDHB | / |

| bta04360 | Axon guidance | 0.0550 | RND1 | SSH2; UNC5A; NFATC3 |

| bta00270 | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 0.0682 | ENSBTAG00000032217; LDHB | / |

| bta00071 | Fatty acid degradation | 0.0417 | CPT1C | ENSBTAG00000052243 |

| bta00051 | Fructose and mannose metabolism | 0.0312 | / | FBP2; ALDOA |

| bta00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 0.0280 | ENSBTAG00000046264 | TYRP1 |

| bta00640 | Propanoate metabolism | 0.0264 | ENSBTAG00000032217; LDHB | / |

| bta01230 | Biosynthesis of amino acids | 0.0222 | / | ALDOA; ENSBTAG00000018554 |

| bta00030 | Pentose phosphate pathway | 0.0205 | / | FBP2; ALDOA |

| bta04936 | Alcoholic liver disease | 0.0175 | SCD5; CPT1C | LPIN1; ENSBTAG00000052243 |

| bta01200 | Carbon metabolism | 0.0129 | / | FBP2; ALDOA; ENSBTAG00000018554 |

| bta01212 | Fatty acid metabolism | 0.0118 | SCD5;CPT1C | ENSBTAG00000052243 |

| bta04625 | C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway | 0.0083 | EGR3; PTGS2 | CCL22; NFATC3 |

| bta04922 | Glucagon signaling pathway | 0.0072 | ENSBTAG00000032217;LDHB;CPT1C | FBP2 |

| bta00620 | Pyruvate metabolism | 0.0047 | ACOT11; ENSBTAG00000032217;LDHB | / |

| bta03320 | PPAR signaling pathway | 0.0026 | SCD5; CPT1C | ENSBTAG00000052243; PLIN2 |

| bta04066 | HIF-1 signaling pathway | 0.0018 | ENSBTAG00000032217; LDHB | ALDOA; ENSBTAG00000018554 |

| bta00010 | Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | <0.0001 | ENSBTAG00000032217; LDHB | FBP2; ALDOA; ENSBTAG00000018554 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).