Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

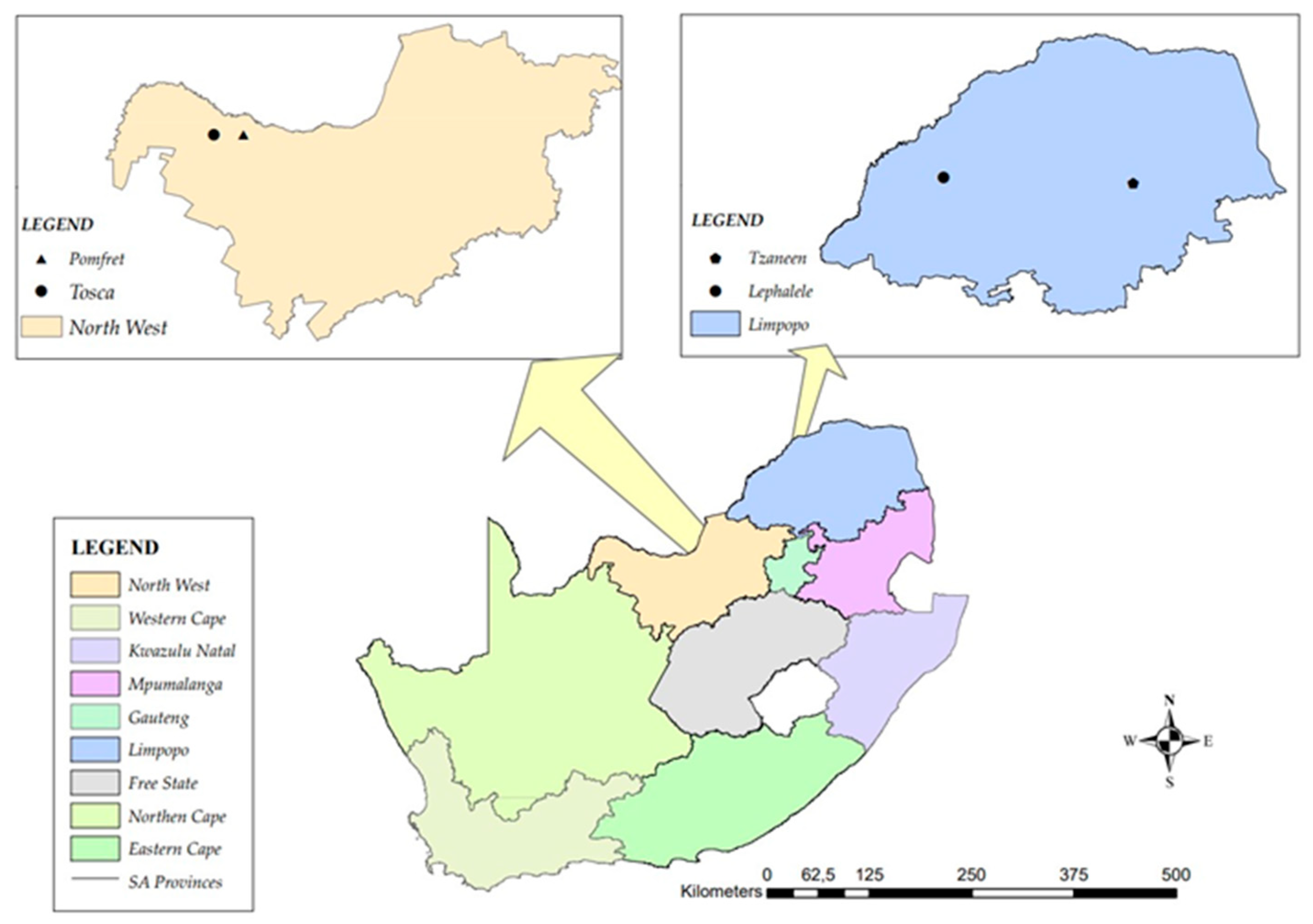

2.1. Description of Study Sites

2.2. Sampling of Insects

2.3. Identification of Sampled Insects

2.3.1. Visual Identification Using Morphological Characteristics

2.3.2. Molecular Identification

2.3.2.1. Extraction of Genomic DNA

2.3.2.2. Genomic DNA Amplification

2.3.2.3. Purification and Sequencing of PCR Products

3. Results

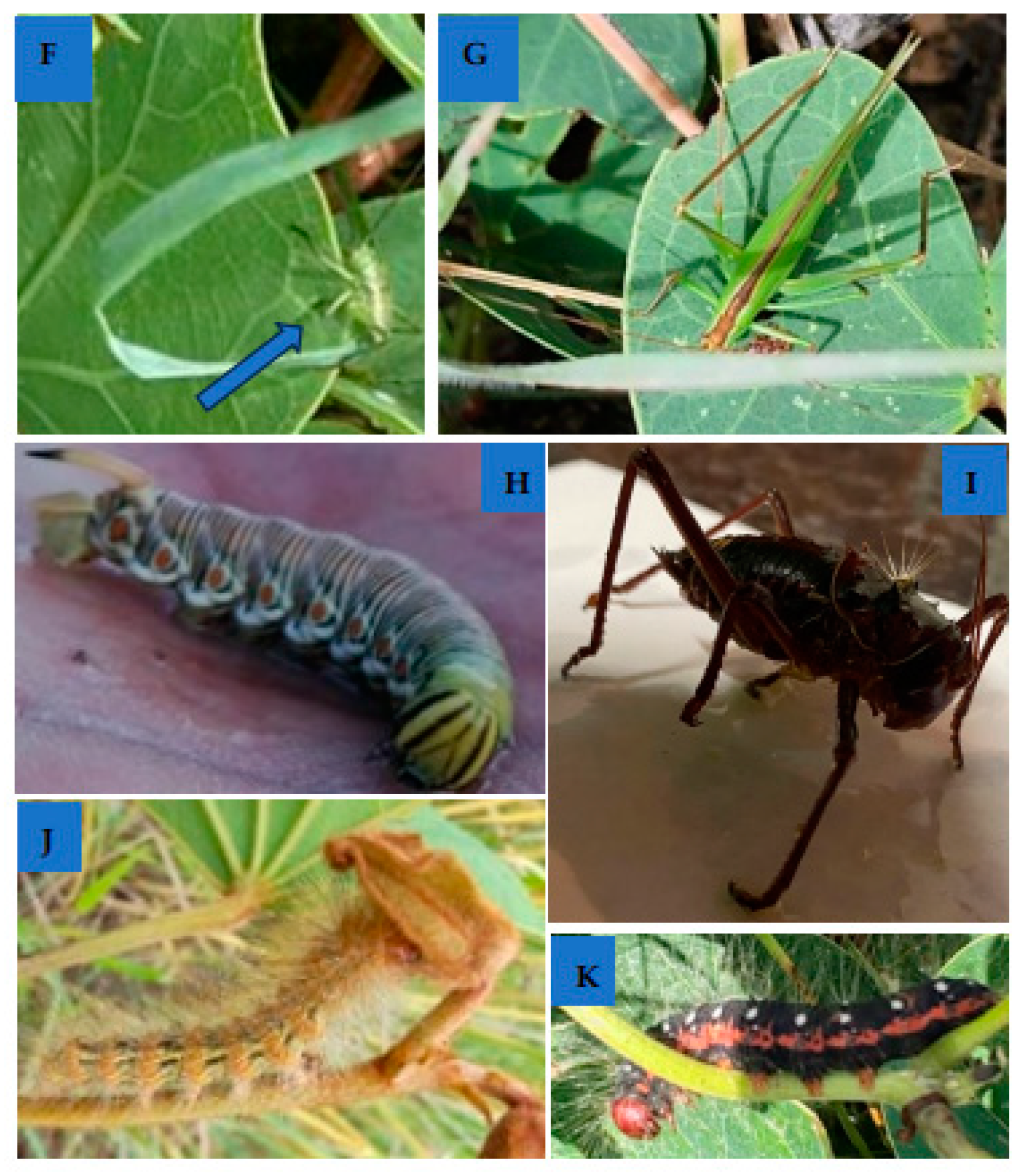

3.1. Insect Pests Associated with Tylosema fassoglense

3.2. Insects Associated with Tylosema esculentum

4. Discussion

4.1. Insects Associated with T. fassoglense

4.2. Insect Pests Associated with T. esculentum

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burhan, K.; Ertek, A.; Bekir, A. Mineral nutrient content of sweet corn under deficit irrigation. Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2016, 22, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, V. Nutritional and health benefits of dried beans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 437S–442S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragya, S.; Rita, S.R. Finger millet for food and nutritional security. African Journal of Food Science 2012. 6, 77–84.

- Omotayo, A.O.; Aremu, A.O. Marama bean [Tylosema esculentum (Burch.) A. Schreib.]: an indigenous plant with potential for food, nutrition, and economic sustainability. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 2389–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullis, C.; Lawlor, D.W.; Chimwamurombe, P.; Bbebe, N.; Kunert, K.; Vorster, J. Development of marama bean, an orphan legume, as a crop. Food Energy Secur. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, S.; Silveira, P.; Coutinho, A.P.; Figueiredo, E. Systematic studies in Tylosema (Leguminosae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2005, 147, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimwamurombe, P.; Khulbe, R. Domestication, in Biology and breeding of food legumes. CABI Wallingford UK, 2011. p. 19-34.

- Jackson, J.C.; Duodu, K.G.; Holse, M.; de Faria, M.D.L.; Jordaan, D.; Chingwaru, W.; Hansen, A.; Cencic, A.; Kandawa-Schultz, M.; Mpotokwane, S.M.; et al. The morama bean (Tylosema esculentum): a potential crop for southern Africa. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research 2010, 61, 187–246; [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamunyela, M.H.; Nepolo, E.; Emmambux, M.N. Proximate and starch composition of marama (Tylosema esculentum) storage roots during an annual growth period. South African Journal of Science 2020, 116, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, A.M. Marama Bean (Tylosema esculentum, Fabaceae) seed crop in Texas. Econ. Bot. 1987, 41, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holse, M.; Husted, S.; Hansen, Å. Chemical composition of marama bean (Tylosema esculentum)—A wild African bean with unexploited potential. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cullis, C. The Multipartite Mitochondrial Genome of Marama (Tylosema esculentum). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 787443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, M. Belay, and J. De Wet, Plant resources of tropical Africa 1: Cereals and pulses. PROTA Foundation Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cullis, C.; Chimwamurombe, P.; Kunert, K.; Vorster, J. Perspective on the present state and future usefulness of marama bean (Tylosema esculentum). Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataranyika, P.N.; Chimwamurombe, P.M.; Fuyane, B.; Chigayo, K.; Lusilao, J. Comparative Nutritional Analysis of Tylosema esculentum (Marama Bean) Germplasm Collection in Namibia. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, M.M.; Hansen, Å.S.; Engelsen, S.B.; Diaz, J.; Sørensen, I.; Ulvskov, P.; Willats, W.G.; Blennow, A.; Harholt, J. Characterisation of the arabinose-rich carbohydrate composition of immature and mature marama beans (Tylosema esculentum). Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonsou, E.O.; Taylor, J.R.; Beukes, M.; Minnaar, A. Composition of marama bean protein. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F.; Anywar, G.; Wack, B.; Quave, C.L.; Garbe, L.-A. Ethnobotanical study of selected medicinal plants traditionally used in the rural Greater Mpigi region of Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 256, 112742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigen, G. , et al. Ethnopharmacological survey of the medicinal plants used in Tindiret, Nandi County, Kenya. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 2016, 13, 156–168. [Google Scholar]

- Otieno, V.O. Conditions for Optimum Germination of Sprawling Bauhinia Seed (Tylosema Fassoglense)(Kotschy Ex Schweinf.) Torre & Hillc. university of Nairobi, 2020.

- Kama-Kama, F.; Midiwo, J.; Nganga, J.; Maina, N.; Schiek, E.; Omosa, L.K.; Osanjo, G.; Naessens, J. Selected ethno-medicinal plants from Kenya with in vitro activity against major African livestock pathogens belonging to the “ Mycoplasma mycoides cluster”. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 192, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandisvika, G.; Chirisa, I.; Bandauko, E. Post-Harvest Issues: Rethinking Technology for Value-Addition in Food Security and Food Sovereignty in Zimbabwe. Adv. Food Technol. Nutr. Sci. Open J. 2015, 1, S29–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukenine, E. Stored product protection in Africa: Past, present and future. [CrossRef]

- Southwood, T. and P. Henderson, Ecological methods / T.R.E. Southwood, P. A. Henderson. SERBIULA (sistema Librum 2.0), 2000.

- Woodcock, B.A. Pitfall trapping in ecological studies. Insect sampling in forest ecosystems, 2005. 37–57.

- Picker, M. , Field guide to insects of South Africa: Penguin Random House South Africa, 2012.

- Hugh Brier, J.W. , Kate Charleston, An identification guide for pest and beneficial insects in summer pulses, soybeans, peanuts and chickpeas, in Good bug Bad bug, H.B.a.T. Grundy, Editor. DEEDI (Primary Industries): Australia, 2012: p. 45.

- Marshall, S.A. , Insects: their natural history and diversity: with a photographic guide to insects of eastern North America. Firefly Books Buffalo, NY, 2006.

- Scholtz, C.H. and E. Holm, Insects of southern Africa: Butterworth, 1985.

- Mathenge, C.W.; Riegler, M.; Beattie, G.A.C.; Spooner-Hart, R.N.; Holford, P. Genetic variation amongst biotypes of Dactylopius tomentosus. Insect Sci. 2015, 22, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J. and W. Megan, Termites, social cockroaches. 2022.

- Picker, M.D.; Hoffman, M.T.; Leverton, B. Density of Microhodotermes viator (Hodotermitidae) mounds in southern Africa in relation to rainfall and vegetative productivity gradients. J. Zoöl. 2006, 271, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edde, P.A. 5 - Arthropod pests of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.), in Field Crop Arthropod Pests of Economic Importance, P.A. Edde, Editor., Academic Press. 2022, p. 276-347.

- Jouquet, P.; Chaudhary, E.; Kumar, A.R.V. Sustainable use of termite activity in agro-ecosystems with reference to earthworms. A review. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, N. , et al., Chapter 5 - Management of Pests and Nematodes, in Sugarcane, F. Santos, A. Borém, and C. Caldas, Editors., Academic Press: San Diego. 2015, p. 89-113.

- Miranda, C.S.; Vasconcellos, A.; Bandeira, A.G. Termites in sugar cane in Northeast Brazil: ecological aspects and pest status. Neotropical Èntomol. 2004, 33, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demissie, G.; Mendesil, E.; Diro, D.; Tefera, T. Effect of crop diversification and mulching on termite damage to maize in western Ethiopia. Crop. Prot. 2019, 124, 104723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsamba, E.F.; Nyagumbo, I.; Mafongoya, P. Termite prevalence and crop lodging under conservation agriculture in sub-humid Zimbabwe. Crop. Prot. 2016, 82, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Chandel, R.S.; Verma, K.S.; Joshi, M.J. Termites in Important Crops and Their Management. Indian J. Èntomol. 2021, 83, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, William H. Urban insects and arachnids: a handbook of urban entomology. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Patel, S., G. Singh, and R. Singh, A checklist of global distribution of Liturgusidae and Thespidae (Mantodea: Dictyoptera). Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 2016. 4(6): p.

- Symondson, W., K. Sunderland, and M. Greenstone, Can generalist predators be effective biocontrol agents? Annual review of entomology, 2002. 47(1): p. 561-594.

- Arnold, D.C. , Blister beetles of Oklahoma. 1976.

- Pierce, J.B. , Blister Beetles in Alfalfa. NM State University Cooperative Extension Service, 2014.

- Eben, A. , Ecology and evolutionary history of Diabrotica beetles—overview and update. Insects, 2022. 13(2), p.156.

- Walsh, G.C.; Avila, C.J.; Cabrera, N.; Nava, D.E.; de Sene Pinto, A.; Weber, D.C. Biology and Management of Pest Diabrotica Species in South America. Insects 2020, 11, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, A.F.; Abiodun, T.A.; Foluke, A.O.; Oluwaseyi, O.E. Comparative assessment of insect pests population densities of three selected cucurbit crops. Acta Fytotech. et Zootech. 2018, 20, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, A.I.; Pasteur, K.; Guzman, F.; Boyle, S.M.; Kuhar, T.P.; Weber, D.C. Spotted cucumber beetle (Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi) is attracted to vittatalactone, the pheromone of striped cucumber beetle (Acalymma vittatum). J. Pest Sci. 2023, 96, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health, E.P.o.P. , et al., Pest categorisation of non-EU Tephritidae. EFSA Journal, 2020. 18(1): p. e05931.

- Jin, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xian, X.; Li, M.; Qi, Y.; Guo, J.; Yang, N.; Lü, Z.; Liu, W. Early warning and management of invasive crop pests under global warming: estimating the global geographical distribution patterns and ecological niche overlap of three Diabrotica beetles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 13575–13590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Marchioro, C.; Krechemer, F.S. Potential global distribution of Diabrotica species and the risks for agricultural production. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 2100–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, J.W. and J.S. Thomas, Burrower bugs (Heteroptera: Cydnidae) in peanut: seasonal species abundance, tillage effects, grade reduction effects, insecticide efficacy, and management. Journal of economic entomology, 2003. 96(4): p. 1142-1152.

- Aigner, B.L., M. S. Crossley, and M.R. Abney, Biology and management of peanut burrower bug (Hemiptera: Cydnidae) in Southeast US Peanut. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2021. 12(1): p. 29.

- Monnig, N.; Bradley, K.W. Impact of fall and early spring herbicide applications on insect populations and soil conditions in no-till soybean. Crop. Prot. 2008, 27, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, C.W. , The food plants of some'primitive'Pentatomoidea (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fernanda-Ruiz-Cisneros, M. , et al., First Record of Feeding by Vanessa cardui Caterpillars1 on Bean Plants and Their Parasitism by Lespesia melalophae2. Southwestern Entomologist, 2020. 45(3): p. 629-638.

- Arpaia, S.; Baldacchino, F.; Bosi, S.; Burgio, G.; Errico, S.; Magarelli, R.A.; Masetti, A.; Santorsola, S. Evaluation of the potential exposure of butterflies to genetically modified maize pollen in protected areas in Italy. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanescu, C.; Puig-Montserrat, X.; Samraoui, B.; Izquierdo, R.; Ubach, A.; Arrizabalaga, A. Back to Africa: autumn migration of the painted lady butterfly Vanessa cardui is timed to coincide with an increase in resource availability. Ecol. Èntomol. 2017, 42, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, R.J. , Noctuinae (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Part 1, Austramathes, Cosmodes, Proteuxoa, Physetica. Fauna of New Zealand, 2017. 73.

- Forbes, R.J.; Watson, S.J.; O’connor, E.; Wescott, W.; Steinbauer, M.J. Diversity and abundance of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera in multiple-species reforestation plantings to offset emissions of carbon dioxide. Aust. For. 2019, 82, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodingpuia, C.; Lalthanzara, H. An insight into black cutworm (Agrotis ipsilon): A glimpse on globally important crop pest. Sci. Vis. 2021, 21, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Lee, H.-A.; Kim, G.-H.; Baek, S. Effects of host plant on the development and reproduction of Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on horticultural crops. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser CL, Steiner A, Bartsch D, Holstein J. On the identity of an enigmatic Delias from New Britain, Papua New Guinea: Delias mayrhoferi Bang-Haas, 1939 and Delias shunichii Morita, 1996, syn. n. Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Nachrichten Entomologischen Vereins Apollo NF. 2009;30(3):121-4.

- Bouyer, T. Démembrement et réorganisation des genres africains Jana Herrich-Schäffer, 1854 et Hoplojana Aurivillius, 1901 (Lepidoptera, Eupterotidae). Lambillionea. 2011;111(3):211-8.

- Municipality ML, District E. Biodiversity assessment. 2021.

- Staude, H.S.; Maclean, M.; Mecenero, S.; Pretorius, R.J.; Oberprieler, R.G.; Van Noort, S.; Sharp, A.; Sharp, I.; Balona, J.; Bradley, S.; et al. Noctuoidea: Erebidae: Lymantriinae, Rivulinae, Scoliopteryginae, Thiacidinae, Tinoliinae, Toxocampinae, undetermined subfamily. Metamorphosis 2022, 31, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, W.W. A manual of dangerous insects likely to be introduced in the United States through importations. Ed. by W. Dwight Pierce, entomologist, southern field crop insect investigations. 2011.

- Tan, J.L.; Trandem, N.; Fránová, J.; Hamborg, Z.; Blystad, D.-R.; Zemek, R. Known and Potential Invertebrate Vectors of Raspberry Viruses. Viruses 2022, 14, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vappula, Niilo A. "Pests of cultivated plants in Finland." (1962).

- Gayo, L. Influence of afforestation on coleopterans abundance and diversity at the University of Dodoma, Tanzania. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawdsley, J.R. , et al., The genus Anthia Weber in the Republic of South Africa, Identification, distribution, biogeography, and behavior (Coleoptera, Carabidae). Zookeys, 2011(143): p. 47-81.

- Bhut, J.; Khanpara, D.; Bharadiya, A.; Madariya, R. Bio-Efficacy of Chemical Insecticides Against Defoliators Spodoptera litura and Achaea janata in Castor. J. Phytopharm. 2022, 11, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasankar, A. , et al., Feeding and growth inhibition activities of Tragiain volucrata Linn (Euphorbiaceae) on Achaea janata (Linn.)(Noctuidae: Lepidoptera) and Pericallia ricini (Fab.)(Lepidoptera: Arctidae). Open Access Library Journal, 2014. 1(4): p. 1-7.

- Phartale, N.; Bhede, B.; Patait, D.; Kadam, T.; Gyananath, G. Pest control potential of four predatory spiders from soybean fields. J. Èntomol. Res. 2019, 43, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamare, V. , et al., Impact of abiotic factors on population dynamics of lepidopteran insect-pests infesting sole soybean and soybean intercropped with pigeonpea. Journal of Entomology and Zoology studies, 2018. 6(5): p. 430-436.

- Dhurgude, S. , et al., Key mortality factors of semilooper Achae janata (Linn) infesting soybean. Journal of Entomological Research, 2014. 38(2): p. 125-128.

- Bolu, H. , et al., A new host record for Exorista xanthaspis (Wiedemann, 1830) (Diptera: Tachinidae) from Turkey. Journal of the Entomological Research Society, 2019. 21(3): p. 373-378.

- Kriegler, P. , Notes on the occurrence of fruit-sucking moths on deciduous fruits in the winter rainfall region. South African Journal of Agricultural Science, 1958. 1(3): p. 245-247.

- Roy, S.; Barooah, A.K.; Ahmed, K.Z.; Baruah, R.D.; Prasad, A.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Impact of climate change on tea pest status in northeast India and effective plans for mitigation. Ecol. Front. 2020, 40, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayi, O. and F.A. Oboite, Importance of spittle bugs, Locris rubens (Erichson) and Poophilus costalis (Walker) on sorghum in West and Central Africa, with emphasis on Nigeria. Annals of Applied Biology, 2000. 136(1): p. 9-14.

- Kruger, M.; Berg, J.v.D.; Du Plessis, H. Diversity and seasonal abundance of sorghum panicle-feeding Hemiptera in South Africa. Crop. Prot. 2008, 27, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Kumar, S.; Sultana, R. A New Species of the Sub-Genus Afromorgus (Trogidae: Scarabaeoidea) from Cholistan Desert, Pakistan. Pak. J. Zoöl. 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, M.L.; Escobar, F.; Halffter, G.; García–Chávez, J.H. Distribution and Feeding Behavior of Omorgus suberosus (Coleoptera: Trogidae) in Lepidochelys olivacea Turtle Nests. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0139538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Tougeron, K.; Gols, R.; Heinen, R.; Abarca, M.; Abram, P.K.; Basset, Y.; Berg, M.; Boggs, C.; Brodeur, J.; et al. Scientists' warning on climate change and insects. Ecol. Monogr. 2023, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outhwaite, C.L.; McCann, P.; Newbold, T. Agriculture and climate change are reshaping insect biodiversity worldwide. Nature 2022, 605, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peace, N. , Impact of climate change on insects, pest, diseases and animal biodiversity. International Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources, 2020. 23(5): p. 151-153.

- Wilson, R.J.; Fox, R. Insect responses to global change offer signposts for biodiversity and conservation. Ecol. Èntomol. 2021; 46, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, A. , et al., Impact of climate change on insect pests and their management strategies. Climate change and sustainable agriculture, 2017: p. 253-286.

- Raven, P.H.; Wagner, D.L. Agricultural intensification and climate change are rapidly decreasing insect biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118, e2002548117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order | Family | Species | Feeding guild |

| Blattodea | Blattidae | Deropeltis erythrocephala | Omnivorous scavengers |

| Isoptera | Hodotermidae Termidae |

Microhodotermes viator Amitermes hastatus |

Detritivores |

| Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | Diabrotica undecimpunctata | Herbivorous pests |

| Meloidea | Zonitis sayi | ||

| Lycidae Scarabaeidae |

Lycus sp Proatetia brevitarsis Maladera drescheri |

||

| Hemiptera | Cydnidae | Sehirus cinctus | Herbivorous pests |

| Pentatomidae | Nezara viridula | ||

| Eupterodidae | Tantaliana tantalus | Unknown | |

| Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | Proteuxoa sp | Herbivorous pest |

| Agrotis ipsilon | Herbivorous pest | ||

| Lasiocampidae | Macrothylacia rubi | Herbivorous pest | |

| Janomima mariana | Unknown | ||

| Nymphalidae | Vanessa cardui | Pest | |

| Sphingidae | Theretra oldenlandiae | Herbivorous pest | |

| Undetermined 1 | Pests | ||

| Mantodea | Thespidae | Hoplocoryphella grandis | Carnivorous predator |

| Orthoptera | Pyrgomorphidae | Zonocerus elegans | Herbivorous pests |

| Acrididae | Undetermined 2 & Undetermined 3 | Herbivorous pests | |

| Order | Family | Species | Feeding guild | |

| Blattodea | Blattidae | Undetermined 4 | Omnivorous scavengers | |

| Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae |

Altica sp Lema rufotestacea |

Herbivorous pests | |

| Meloidea | Zonitis sayi | |||

| Erotylidae | Amblyopus sp | Unknown | ||

| Scarabaeidae | Sisyphus sp | Coprophagous | ||

| Trogidae | Omorgus asperulatus | Necrophagous | ||

| Tenebrionidae |

Gonopus tibialis Psammodes bertelonii Psammodes striatus |

Herbivorous pest | ||

| Unknown | ||||

| Herbivorous pest | ||||

| Carabidae |

Anthia cinctipennis Passalidius fortipes |

Predators | ||

| Phalacridae | Olibrus sp | Herbivorous pests | ||

| Hemiptera | Cercopidae | Locris arithmetica | Herbivorous pests | |

| Scutelleridae | Solenostethium liligerum | |||

| Lepidoptera | Erebidae |

Achaea Janata Utetheisa pulchella |

Herbivorous pests | |

| Noctuidae |

Helicoverpa armigera Cyligramma latona Undetermined 5 |

|||

| Geometridae |

Undetermined 6 Undetermined 7 & 8 |

|||

| Odonata | Libellulidae | Undetermined 9 | Carnivorous pest | |

| Orthoptera | Pyrgomorphidae Acrididae Bradyporidae |

Zonocerus elegans Undetermined 10 Locustana pardalina Acanthoplusdiscoidalis |

Herbivorous pests | |

| Haematophagous | ||||

| Omnivorous pests | ||||

| Tettigoniidae | Tettigonia viridissima | Herbivorous pests | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).