Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

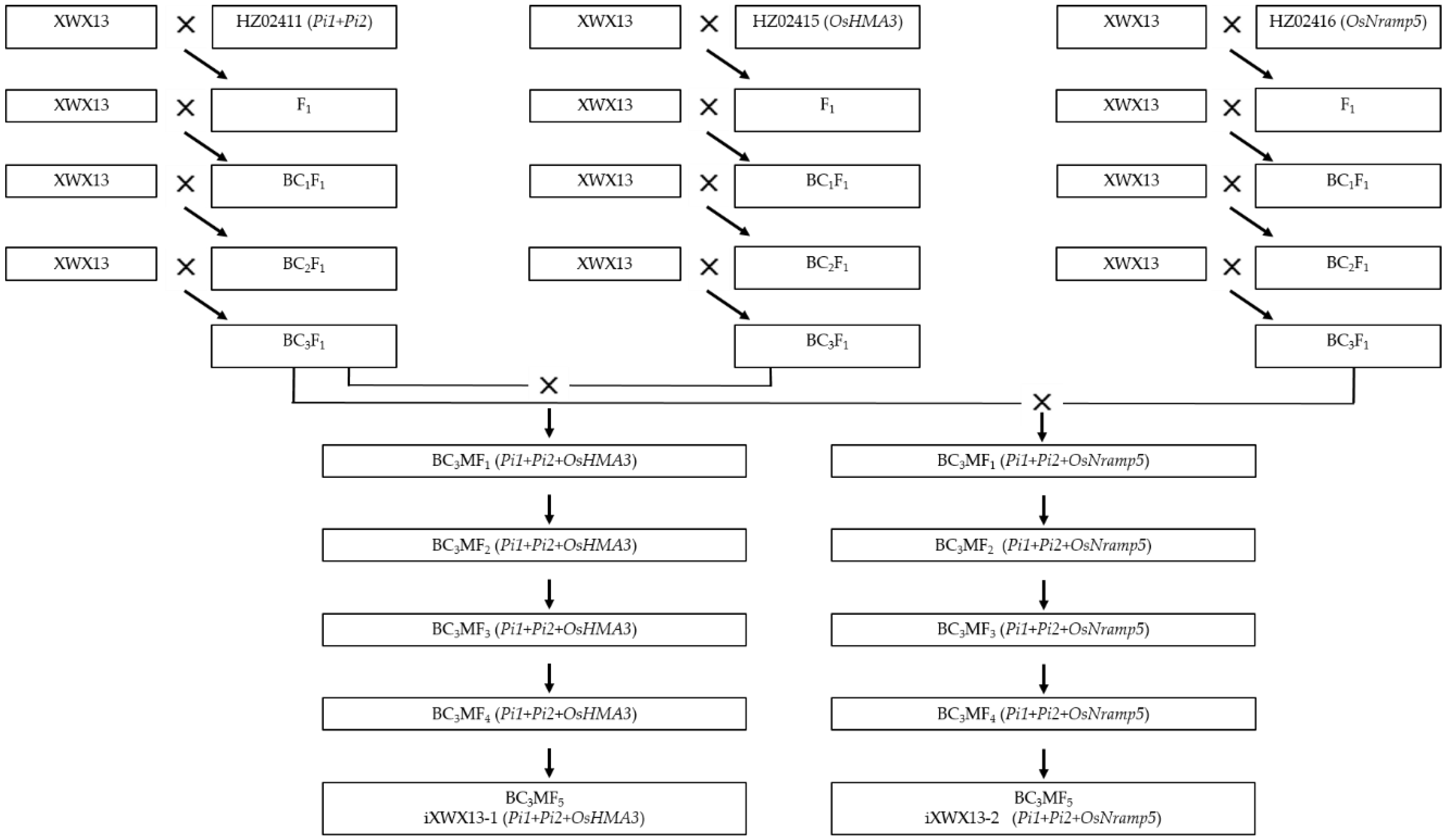

2.2. Population Development and Breeding Selection Procedure

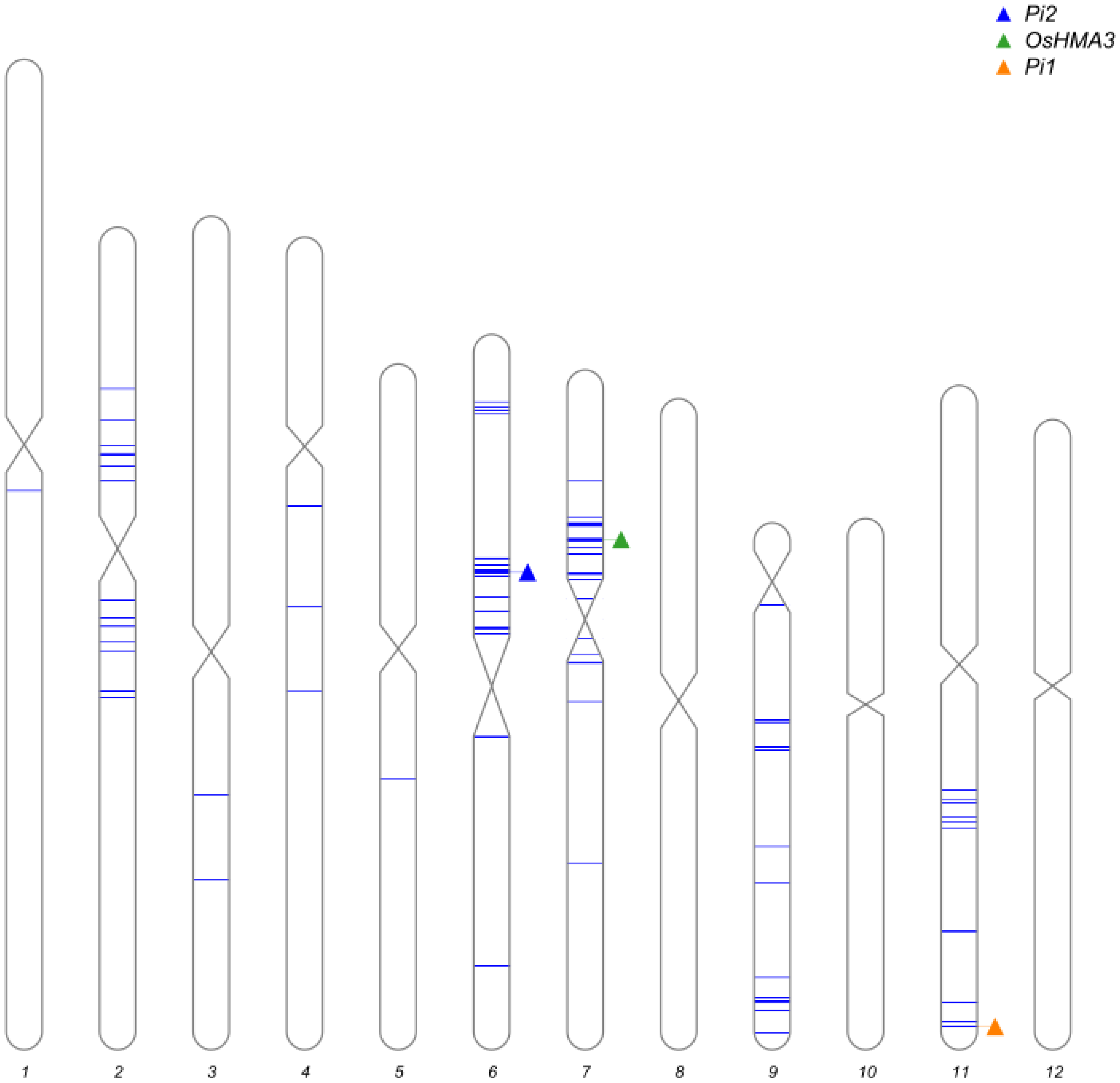

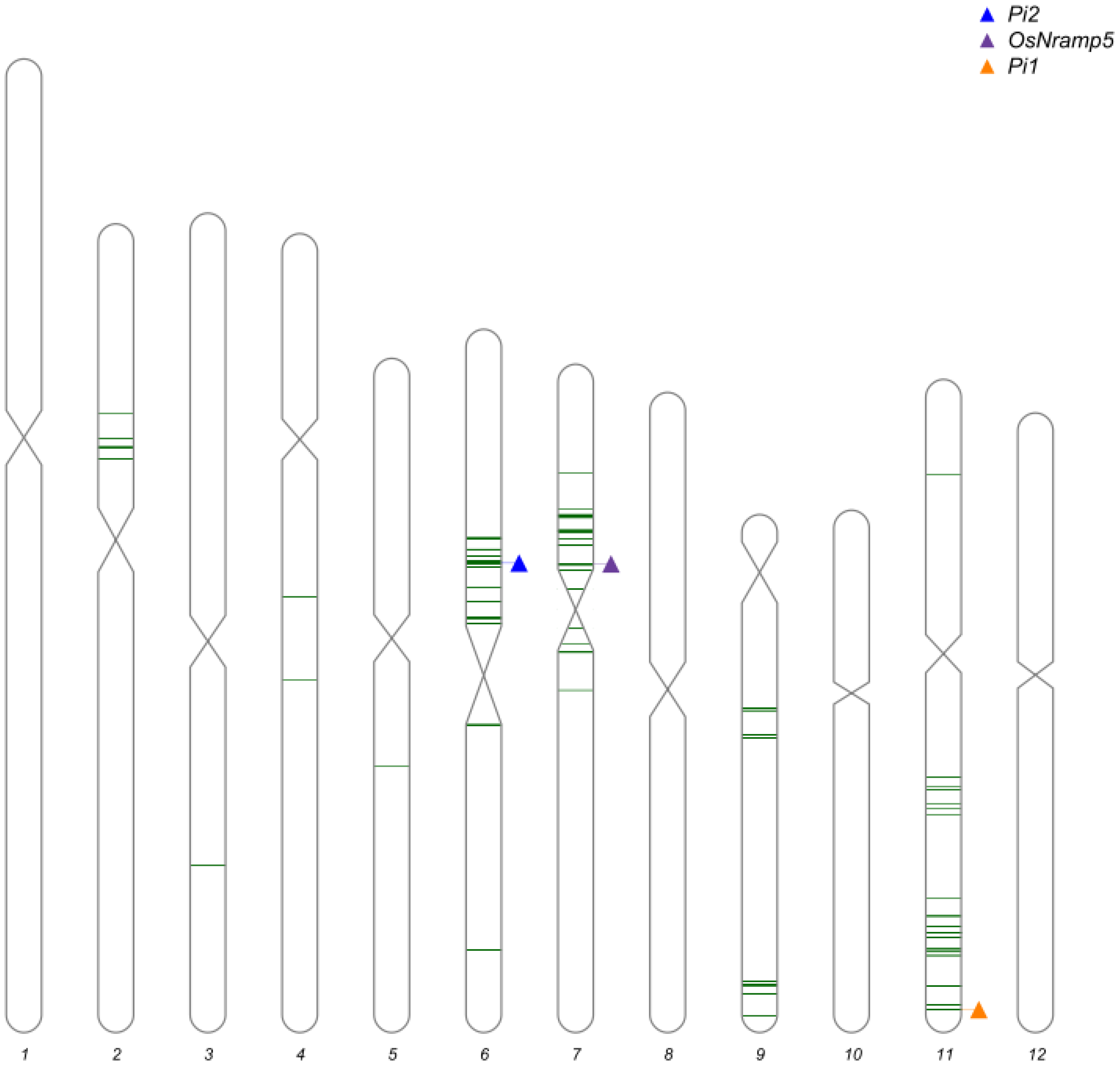

2.3. Marker-Assisted Selection and Background Analysis

2.4. Evaluation of Rice Blast Resistance

2.5. Evaluation of Yield, Main Agronomic Traits and Grain Quality

2.6. Determination of the Grain Cd Concentration

3. Results

3.1. Development of the Improved Lines

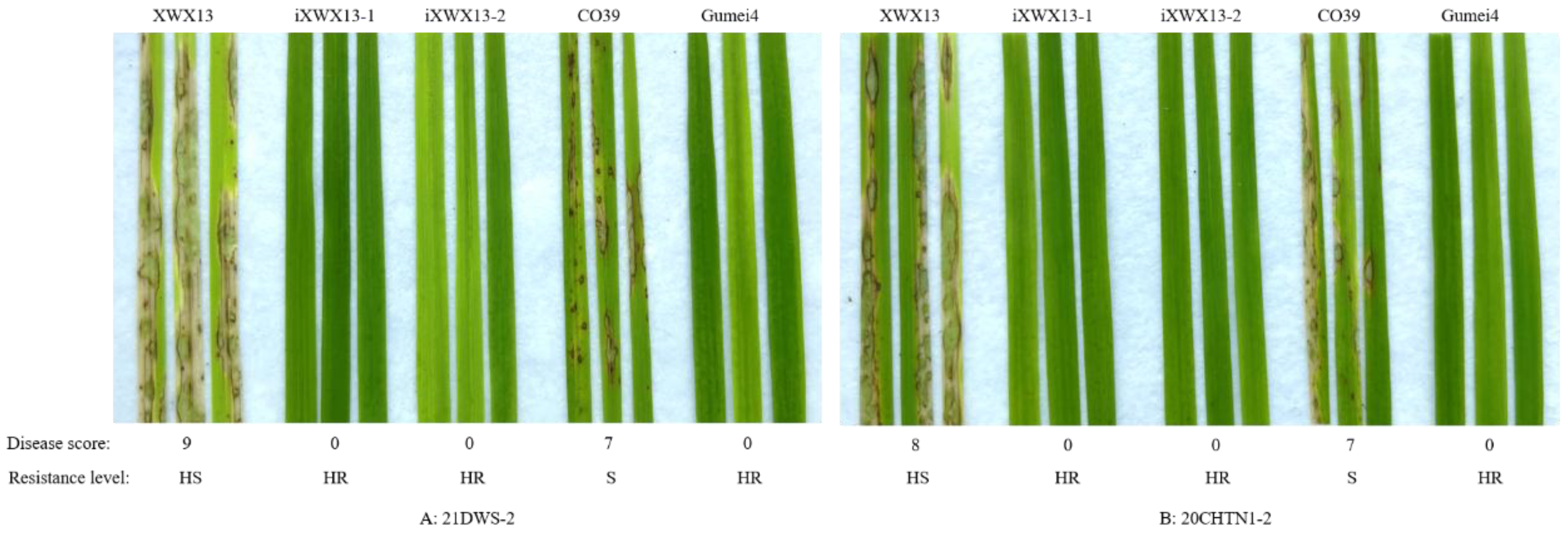

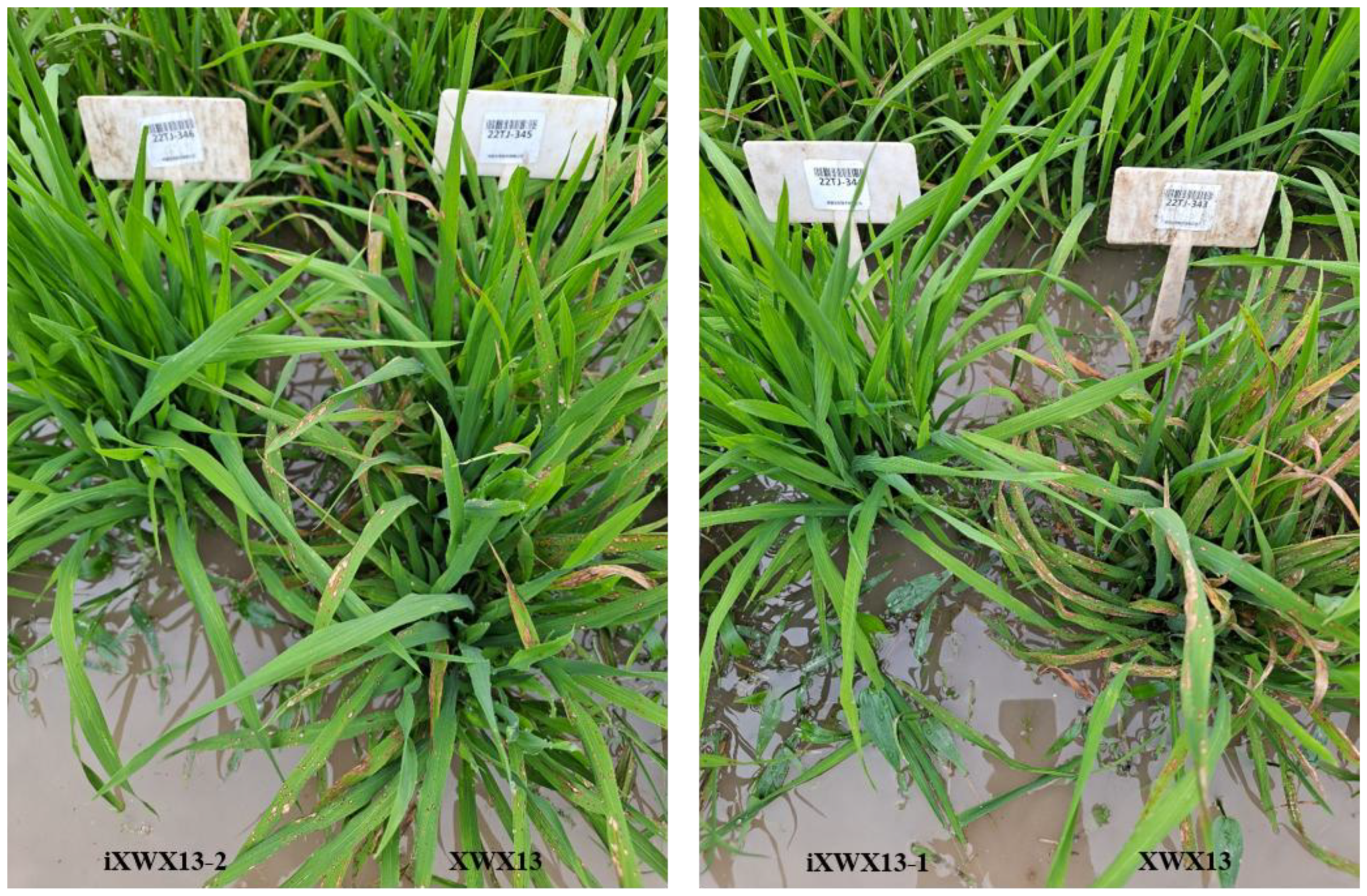

3.2. Blast Resistance of the Improved Lines

3.3. Yield, Agronomic Traits and Grain Quality of the Improved Lines

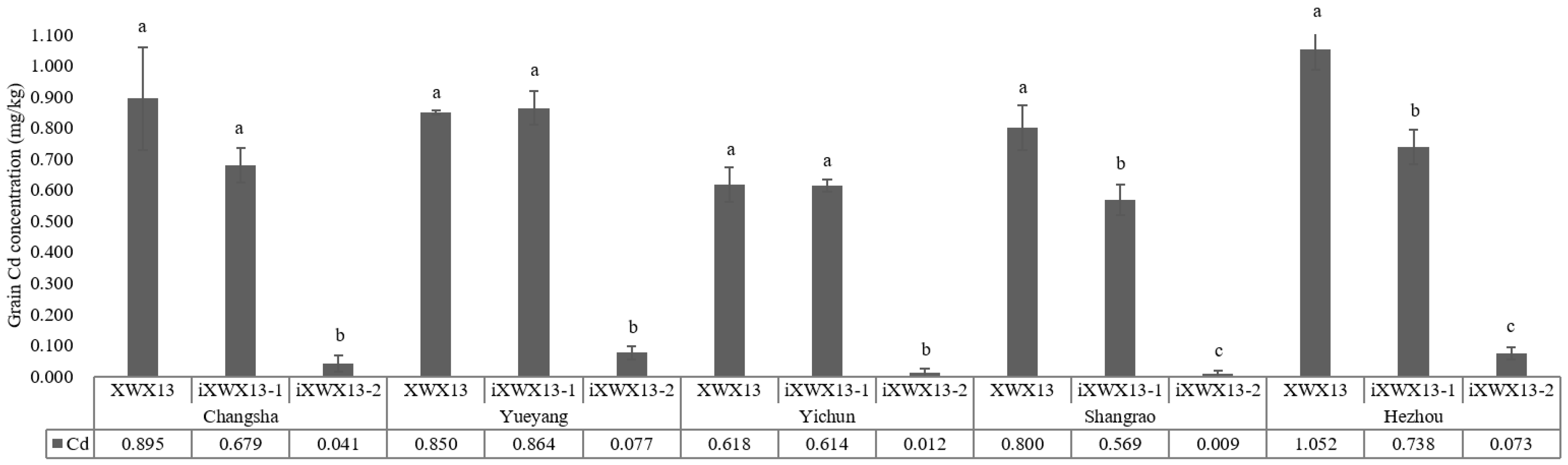

3.4. Grain Cd Accumulation in the Improved Lines

4. Discussion

Improvement Achieved by Genomic Marker-Assisted Selection

Pyramiding Genes to Improve Blast Resistance and Cd Accumulation

Improvement of Traits Without Penalty of the Yield, Main Agronomic Traits and Grain Quality

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khush, G.S. What it will take to feed 5.0 billion rice consumers in 2030. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L. Development of hybrid rice to ensure food security. Rice Sci. 2014, 21, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Skamnioti, P.; Gurr, S.J. Against the grain: safeguarding rice from rice blast disease. Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, W. Genetic and biochemical mechanisms of rice resistance to planthopper. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Ali, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.F. Genomic breeding of Green Super Rice varieties and their deployment in Asia and Africa. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1427–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubier, A.; Wilkin, R.T.; Pichler, T. Cadmium in soils and groundwater: A review. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 108, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, H.; Kopittke, P.; Zhao, F. Cadmium contamination in agricultural soils of China and the impact on food safety. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Shen, R.; Shao, J. Transport of cadmium from soil to grain in cereal crops: A review. Pedosphere 2021, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Wu, Y.; Li, A. Strategy for use of rice blast resistance genes in rice molecular breeding. Rice Sci. 2020, 27, 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Devanna, B.N.; Jain, P.; Solanke, A.U.; Das, A.; Thakur, S.; Singh, P.K.; Kumari, M.; Dubey, H.; Jaswal, R.; Pawar, D.; Kapoor, R.; Singh, J.; Arora, K.; Saklani, B.K.; AnilKumar, C.; Maganti, S.M.; Somah, H.; Deshmukh, R.; Rathour, R.; Sharma, T.R. Understanding the dynamics of blast resistance in rice-magnaporthe oryzae interactions. J. Fungi. 2022, 8, 584. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.H.; Mackill, D.J.; Bonman, J.M.; McCouch, S.R.; Guiderdoni, E.; Notteghem, J.L.; Tanksley, S.D. Molecular mapping of genes for resistance to rice blast (Pyricularia grisea Sacc.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 1996, 93, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, C.; Wu, W.; He, X.; Lin, F.; Wang, L.; Ashikawa, I.; Matsumoto, T.; Wang, L.; Pan, Q. The isolation of Pi1, an allele at the Pik locus which confers broad spectrum resistance to rice blast. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Lu, G.; Zeng, L.; Wang, G. Two broad-spectrum blast resistance genes, Pi9(t) and Pi2(t), are physically linked on rice chromosome 6. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2002, 267, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Daigen, M.; Ashikawa, I. Development of PCR-based SNP markers for rice blast resistance genes at the Piz locus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Shen, Y.; He, Z. Genetic characterization and fine mapping of the blast resistance locus Pigm(t) tightly linked to Pi2 and Pi9 in a broad-spectrum resistant Chinese variety. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 705–713. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, S.; Zeng, L.; Han, J.; Su, J.; Wang, L.; Pan, Q. The identification of Pi50(t), a new member of the rice blast resistance Pi2/Pi9 multigene family. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Feng, Y.; Bao, L.; Li, X.; Gao, G.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Xu, C.; He, Y. Improving blast resistance of Jin23B and its hybrid rice by marker-assisted gene pyramiding. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, J.; Yang, D.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Mou, H.; Huang, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Mou, T. Accelerated molecular breeding of a novel P/TGMS line with broad-spectrum resistance to rice blast and bacterial blight in two-line hybrid rice. Rice 2018, 11, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Tang, J.; Yang, D.; Chen, Y.; Ali, J.; Mou, T. Improving rice blast resistance of Feng39S through molecular marker-assisted backcrossing. Rice 2019, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Xin, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Ye, C.; Yin, H.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, N.; Huang, J.; Xiao, J.; Tian, B.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Peng, J. Genomics-assisted improvement of super high-yield hybrid rice variety "Super 1000" for resistance to bacterial blight and blast diseases. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 881214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, R.L.; Reeves, P.G.; Ryan, J.A.; Simmons, R.W.; Welch, R.M.; Angle, J.S. An improved understanding of soil Cd risk to humans and low cost methods to remediate soil Cd risks. BioMetals 2004, 17, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S.; Aarts, M.M.; Thomine, S.; Verbruggen, N. Plant science: the key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaney, R.L. How does contamination of rice soils with Cd and Zn cause high incidence of human Cd disease in subsistence rice farmers. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants, Fifty-fifth Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives, WHO Technical Report Series. 2001, No. 901.

- Zhao, F.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, Z.; McGrath, S.P. Soil contamination in China: current status and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 750–759. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Jin, Q.; Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5820–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Peng, C. Risk assessment of Cd polluted paddy soils in the industrial and township areas in Hunan, Southern China. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin, M.J.; Smolders, E.; Zhao, F.; Grant, C.; Montalvo, D. Managing cadmium in agricultural systems. Adv. Agron. 2021, 166, 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Carey, M.; Meharg, C.; Williams, P.N.; Signes-Pastor, A.J.; Triwardhani, E.A.; Pandiangan, F.I.; Campbell, K.; Elliott, C.; Marwa, E.M.; Xiao, J.; Farias, J.G.; Nicoloso, F.T.; De Silva, P.M.C.S.; Lu, Y.; Norton, G.; Adoako, E.; Green, A.J.; Moreno-Jimenez, E.; Zhu, Y.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; Haris, P.; Lawgali, Y.F.; Sommella, A.; Pigna, M.; Brabet, C.; Montet, D.; Njira, K.; Watts, M.; Hossain, M.; Islam, M.; Tapia, Y.; Oporto, C.; Meharg, A.A. Rice Grain Cadmium Concentrations in the Global Supply-Chain. Expo. Health 2020, 12, 869–876. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Tang, W.B. A perspective on the selection and breeding of low-Cd rice. Res. Agric. Mod. 2018, 39, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, S.; Ma, J.F. Toxic heavy metal and metalloid accumulation in crop plants and foods. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016, 67, 489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Tang, Z.; Song, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, P. Toxic metals and metalloids: Uptake, transport, detoxification, phytoremediation, and crop improvement for safer food. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Xu, W.; Xie, J.; Gao, Y.; Wu, L.; Sun, L.; Feng, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, T.; Dai, C.; Li, T.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Ma, M.; Zhang, H.; He, Z. Variation of a major facilitator superfamily gene contributes to differential cadmium accumulation between rice subspecies. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, J.; Zeng, D.; Peng, J.; Zhang, G.; Ma, H.; Guan, Y.; Yi, H.; Fu, Y.; Han, B.; Lin, H.; Qian, Q.; Gong, J. A defensin-like protein drives cadmium efflux and allocation in rice. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Mao, D.; Sun, L.; Wang, R.; Tan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, H.; Peng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, C. CF1 reduces grain-cadmium levels in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant J. 2022, 110, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uraguchi, S.; Fujiwara, T. Rice breaks ground for cadmium-free cereals. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013, 16, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Pinson, S.R.; Tarpley, L.; Huang, X.Y.; Lahner, B.; Yakubova, E.; Baxter, I.; Guerinot, M.L.; Salt, D.E. Mapping and validation of quantitative trait loci associated with concentrations of 16 elements in unmilled rice grain. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 137–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, A.; Chen, L.; Tang, W.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Xiao, G.; Huang, D.; Chen, C. Genetic diversity, rather than cultivar type, determines relative grain Cd accumulation in hybrid rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1407. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Wang, R.; Tang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ma, H.; Si, L.; Deng, H.; Han, L.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, D.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, C. Robust identification of low-Cd rice varieties by boosting the genotypic effect of grain Cd accumulation in combination with marker-assisted selection. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127703. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Lu, K.; Zhao, F.; Xie, W.; Ramakrishna, P.; Wang, G.; Du, Q.; Liang, L.; Sun, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tian, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, W.; Dong, H.; Hu, J.; Ming, L.; Xing, Y.; Wang, G.; Xiao, J.; Salt, D.; Lian, X. Genome-wide association studies reveal the genetic basis of ionomic variation in rice. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 2720–2740. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, S.; Yang, T.; Liu, Q.; Dong, J.; Fu, H.; Mao, X.; Liu, B. Genome-wide association study and candidate gene analysis of rice cadmium accumulation in grain in a diverse rice collection. Rice 2018, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, M.; Zheng, G.; Peng, Y.; Shi, X.; Qin, P.; Xu, X.; Teng, S. Association study reveals genetic loci responsible for arsenic, cadmium and lead accumulation in rice grain in contaminated farmlands. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, F.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, H.; Gong, Y.; Tang, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, F. Map-based cloning of a new total loss-of-function allele of OsHMA3 causes high cadmium accumulation in rice grain. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 2857–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Sun, L.; Song, Q.; Mao, D.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, T.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, D.; Xiao, H.; Chen, C. Genetic architecture of subspecies divergence in trace mineral accumulation and elemental correlations in the rice grain. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, L. The genetic architecture for phenotypic plasticity of the rice grain ionome. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Deng, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, W.; Sun, L. Genetic control diversity drives differences between cadmium distribution and tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 638095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Tan, Y.; Chen, C. The road toward Cd-safe rice: from mass selection to marker-assisted selection and genetic manipulation. The Crop Journal 2023, 4, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.; Ishimaru, Y.; Igura, M.; Kuramata, M.; Abe, T.; Senoura, T.; Hase, Y.; Arao, T.; Nishizawa, N.K.; Nakanishi, H. Ion-beam irradiation, gene identification, and marker-assisted breeding in the development of low-cadmium rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 19166–19171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Mao, B.; Li, Y.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; He, H.; Wang, W.; Zeng, X.; Shao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, H.; Xia, S.; Zhao, B. Knockout of OsNramp5 using the CRISPR/Cas9 system produces low Cd-accumulating indica rice without compromising yield. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xie, H.; Song, S.; Qiu, M.; Wen, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, G.; Tian, Y.; Li, C.; Yuan, D.; Wang, J.; Li, L. Mutation at different sites of metal transporter gene OsNramp5 affects Cd accumulation and related agronomic traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.D.; Huang, S.; Konishi, N.; Wang, P.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Ma, J.; Zhao, F.; Dietz, K. Overexpression of the manganese/cadmium transporter OsNRAMP5 reduces cadmium accumulation in rice grain. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5705–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J. Overexpression of OsHMA3 enhances Cd tolerance and expression of Zn transporter genes in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 6013–6021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Z.; Huang, X.; Ma, J.; Zhao, F. Producing cadmium-free indica rice by overexpressing OsHMA3. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanksley, S.; Young, N.; Paterson, N.; Bonierbale, M. RFLP mapping in plant breeding: new tools for an old science. Nat. Biotechnol. 1989, 7, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Parker, J.E.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Schroeder, J.I. Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature 2019, 575, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, X. Comparison of different foreground and background selection methods in marker-assisted introgression. Acta Genet. Sin. 2006, 33, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xie, C.; Gao, S.; Wan, J.; Prasanna, B.M. Whole-genome strategies for marker-assisted plant breeding. Mol. Breed. 2012, 29, 833–854. [Google Scholar]

- Mangal, V.; Verma, L.K.; Singh, S.K.; Saxena, K.; Roy, A.; Karn, A.; Rohit, R.; Kashyap, S.; Bhatt, A.; Sood, S. Triumphs of genomic-assisted breeding in crop improvement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, R.M.; Morales, K.Y.; Singh, N.; Perez, F.A.; Ignacio, J.C.; Thapa, R.; Arbelaez, J.D.; Tabien, R.E.; Famoso, A.; Wang, D.R.; Septiningsih, E.M.; Shi, Y.; Kretzschmar, T.; McCouch, S.R.; Thomson, M.J. An improved 7K SNP array, the C7AIR, provides a wealth of validated SNP markers for rice breeding and genetics studies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232479. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Yang, Y.; Yi, H.; Xu, L.; He, H.; Fan, Y.; Wang, L.; Ge, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhao, J. New resources for genetic studies in maize (Zea mays L.): a genome-wide Maize6H-60K single nucleotide polymorphism array and its application. Plant J. 2020, 105, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, A.; Hao, Y.; Xia, X.; Khan, A.; Xu, Y.; Varshney, R.K.; He, H. Crop Breeding Chips and Genotyping Platforms: Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. Mol. Plant. 2017, 10, 1047–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, M.M.; Rapazote-Flores, P.; Ganal, M.; Hedley, P.E.; Macaulay, M.; Plieske, J.; Ramsay, L.; Russell, J.; Shaw, P.D.; Thomas, W.; Waugh, R. Development and Evaluation of a Barley 50k iSelect SNP Array. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1792. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, F. The Wheat 660K SNP array demonstrates great potential for marker-assisted selection in polyploid wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020, 18, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ali, J.; Zhou, S.; Ren, G.; Xie, H.; Xu, J.; Yu, X.; Zhou, F.; Peng, S.; Ma, L.; Yuan, D.; Li, Z.; Chen, D.; Zheng, R.; Zhao, Z.; Chu, C.; You, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, S.; Gu, Q.; He, G.; Li, S.; Liu, G.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, J.; Luo, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q. From Green Super Rice to green agriculture: reaping the promise of functional genomics research. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, C.W.; Zhao, K.Y.; Wright, M.H.; Ali, M.L.; Jung, J.; Kimball, J.; Tyagi, W.; Thomson, M.J.; McNally, K.; Leung, H.; Kim, H.; Ahn, S.N.; Reynolds, A.; Scheffler, B.; Eizenga, G.; McClung, A.; Bustamante, C.; McCouch, S.R. Development of a research platform for dissecting phenotype-genotype associations in rice (Oryza spp.). Rice 2010, 3, 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Xie, W.; Li, J.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Q. A whole genome SNP array, RICE6K, for genomic breeding in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Jayaswal, P.K.; Panda, K.; Mandal, P.; Kumar, V.; Singh, B.; Mishra, S.; Singh, Y.; Singh, R.; Rai, V.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, T.R.; Singh, N.K. Single-copy gene based 50 K SNP chip for genetic studies and molecular breeding in rice. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCouch, S.; Wright, M.; Tung, C.W.; Maron, L.; McNally, K.; Fitzgerald, M.; Singh, N.; DeClerck, G.; Agosto, P.F.; Korniliev, P.; Greenberg, A.J.; Naredo, M.E.; Mercado, S.M.; Harrington, S.E.; Shi, Y.; Branchini, D.A.; Kuser-Falcão, P.R.; Leung, H.; Ebana, K.; Yano, M.; Eizenga, G.; McClung, A.; Mezey, J. Open access resources for genome wide association mapping in rice. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10532. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, K.Y.; Singh, N.; Perez, F.A.; Ignacio, J.C.; Thapa, R.; Arbelaez, J.D.; Tabien, R.E.; Famoso, A.; Wang, D.R.; Septiningsih, E.M.; Shi, Y.; Kretzschmar, T.; McCouch, S.R.; Thomson, M.J. An improved 7K SNP array, the C7AIR, provides a wealth of validated SNP markers for rice breeding and genetics studies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Liang, L.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; L, Yi.; Liang, J.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Fu, B.; Shi, Y.; Xu, J.; Tian, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, W. Rice3K56 is a high-quality SNP array for genome-based genetic studies and breeding in rice (Oryza sativa L.). The Crop Journal 2023, 11, 800–807. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, B.; Teng, Z.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Ling, W.; Xiang, S.; Bai, L. Screening and verification of rice varieties with low cadmium accumulation. Hunan Agric. Sci. 2017, 12, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, S.; Hu, J.; Sun, W.; Padilla, J.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Yin, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Shen, D.; Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Cui, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, P.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Z. Phosphorylation-guarded light-harvesting complex II contributes to broad-spectrum blast resistance in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 17572–17577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Standard Evaluation System for Rice. Manila. Philippines. 1996, 4th ed, pp. 17-18.

- Latif, M.A.; Badsha, M.A.; Tajul, M.I.; Kabir, M.S.; Rafii, M.Y.; Mia, M. Identification of genotypes resistant to blast.; bacterial leaf blight.; sheath blight and tungro and efficacy of seed treating fungicides against blast disease of rice. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 2804–2811. [Google Scholar]

- Wing, R.A.; Purugganan, M.D.; Zhang, Q. The rice genome revolution: from an ancient grain to Green Super Rice. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C. Genome engineering for crop improvement and future agriculture. Cell 2021, 184, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Jiang, G.; Yang, L.; Qiu, L.; He, P.; Nong, C.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Xing, Y. Gene diagnosis and targeted breeding for blast-resistant Kongyu 131 without changing regional adaptability. J. Genet. Genomics 2018, 45, 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Gao, Y.; Mao, F.; Xiong, L.; Mou, T. Directional upgrading of brown planthopper resistance in an elite rice cultivar by precise introgression of two resistance genes using genomics-based breeding. Plant Sci. 2019, 288, 110211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Xiong, L.; Mou, T.; Mi, J. Improving the resistance of the rice PTGMS line Feng39S by pyramiding blast, bacterial blight, and brown planthopper resistance genes. The Crop Journal 2022, 10, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Mawia, A.M.; Hui, S.; Xu, B.; Jiao, G.; Sheng, Z.; Shao, G.; Wei, X.; Wang, L.; Xie, L.; Zhao, F.; Tang, S.; Hu, P. Production of grains with ultra-low heavy metal accumulation by pyramiding novel Alleles of OsNramp5 and OsLsi2 in two-line hybrid rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2921–2931. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Song, J.; Cui, Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, J. Detection and evaluation of blast resistance genes in backbone indica rice varieties from South China. Plants 2024, 13, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, N.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Pan, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, N.; Ji, H.; Dai, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, A. Comprehensive evaluation of resistance effects of pyramiding lines with different broad-spectrum resistance genes against Magnaporthe oryzae in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 2019, 12, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hittalmani, S.; Parco, A.; Mew, T.V.; Zeigler, R.S.; Huang, N. Fine mapping and DNA marker-assisted pyramiding of the three major genes for blast resistance in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 100, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.P.; Ellur, R.K.; Choudhary, V.; Sarkel, S.; Singh, D.; Krishnan, S.G.; Nagarajan, M.; Vinod, K.K. Incorporation of blast resistance into “PRR78”, an elite Basmati rice restorer line, through marker assisted backcross breeding, Field Crops Res. 2012, 128, 8-16.

- Zeng, P.; Wei, B.; Zhou, H.; Gu, J.; Liao, B. Co-application of water management and foliar spraying silicon to reduce cadmium and arsenic uptake in rice: A two-year field experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.J.; Wang, P. Arsenic and cadmium accumulation in rice and mitigation strategies. Plant and Soil 2020, 446, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, R.; Tian, L.; Song, T.; Tan, H.; Peng, Y.; Zeng, M.; Chen, L.; Liang, M.; Li, D. Association between sequence variants in cadmium-related genes and the cadmium accumulation trait in thermo-sensitive genic male sterile rice. Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, L.; Yang, M.; Zou, X.; Yin, C.; Lin, Y. Research Advances in Cadmium Uptake, Transport and Resistance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Cells 2022, 11, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, C.; Zhu, J.; Li, F.; Deng, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C. Cadmium availability in rice paddy fields from a mining area: The effects of soil properties highlighting iron fractions and pH value. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 209, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Pinson, S.R.M.; Tarpley, L.; Huang, X.Y.; Lahner, B.; Yakubova, E.; Baxter, I.; Guerinot, M.L.; Salt, D.E. Mapping and validation of quantitative trait loci associated with concentrations of 16 elements in unmilled rice grain. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 137–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Whalley, W.; Miller, A.; White, P.; Zhang, F.; Shen, J. Sustainable Cropping Requires Adaptation to a Heterogeneous Rhizosphere. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zhu, C.; Ren, Y.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, D. Genotypic variation in grain cadmium concentration of lowland rice. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2006, 169, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, F.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Z. Cadmium accumulation in different rice cultivars and screening for pollution-safe cultivars of rice. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 370, 302–309. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; He, Z. The seesaw action: balancing plant immunity and growth. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.; Wiesner-Hanks, T.; Wisser, R.; Balint-Kurti, P. Navigating complexity to breed disease-resistant crops. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellur, R.K.; Khanna, A.; S, G.K.; Bhowmick, P.K.; Vinod, K.K.; Nagarajan, M.; Mondal, K.K.; Singh, N.K.; Singh, K.; Prabhu, K.V.; Singh, A.K. Marker-aided incorporation of Xa38, a novel bacterial blight resistance gene, in PB1121 and comparison of its resistance spectrum with xa13 + Xa21. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mores, A.; Borrelli, G.M.; aidò, L.G.; Petruzzino, G.; Pecchioni, N.; Amoroso, L.G.; Desiderio, F.; Mazzucotelli, E.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Marone, D. Genomic approaches to identify molecular bases of crop resistance to diseases and to develop future breeding strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code of isolates | Place of origin | XWX13 | iXWX13-1 | iXWX13-2 | CO39 | Gumei4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110-2 | Hunan, China | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 236-1 | Hunan, China | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 2016CH-2 | Hunan, China | 8 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 21TJ-9 | Hunan, China | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 21TJ-18 | Hunan, China | 8 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 21TJ-23 | Hunan, China | 9 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 21DWS-2 | Hunan, China | 9 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 21DWS-4 | Hunan, China | 9 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 21DWS-19 | Hunan, China | 9 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 20JYR900-3 | Hunan, China | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 20JYR900-18 | Hunan, China | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 20JYR900-23 | Hunan, China | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 20CHR900-5 | Hunan, China | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 20CHTN1-2 | Hunan, China | 8 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 20CHTN1-28 | Hunan, China | 8 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| E2007046A2 | Hubei, China | 7 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 6 |

| E2007038A3 | Hubei, China | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 19-765-1-2 | Zhejiang, China | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 19-763-7-2 | Zhejiang, China | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| RB7 | Guangdong, China | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| CHL1743 | Guangdong, China | 9 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| M2006123A3 | Fujian, China | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| M2006123A1 | Fujian, China | 9 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| C8-3-1 | Sichuan, China | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 20DT-1 | Sichuan, China | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 20DT-6 | Sichuan, China | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 20DT-14 | Sichuan, China | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 12-1 | Sichuan, China | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 19-9-6-2 | Sichuan, China | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| CH-11391 | Yunnan, China | 3 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| CH105a | Yunnan, China | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 2016ZY-8 | Unknown | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 95097AZC13 | Unknown | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| chnos60-2-3 | Unknown | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| ROR1 | South Korea | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| P06-6 | Philippines | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Guy11 | France | 8 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| ES6 | Spain | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| IC-17 | America | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Number of resistant isolates | 7 | 38 | 39 | 7 | 36 | |

| Number of susceptible isolates | 32 | 1 | 0 | 32 | 3 | |

| Resistance frequency | 17.95% | 97.44% | 100.00% | 17.95% | 92.31% | |

| Entries | Dawei Mountain, Liuyang City | Taojiang County, Yiyang City | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf blast score | Leaf blast score | Panicle neck blast infection rate | |

| CO39 | 7 | 7 | 50% |

| Fengliangyou4 | 7 | 7 | 40% |

| XWX13 | 7 | 8 | 18% |

| iXWX13-1 | 0 | 2 | 4% |

| XWX13 | 7 | 7 | 15% |

| iXWX13-2 | 1 | 2 | 5% |

| Gumei4 | 2 | 2 | 6% |

| Sites | Entries | YD | DTM | PH | PL | SPP | FGP | GW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changsha | XWX13 | 6.70 | 116.0 | 116.2 | 23.5 | 128.2 | 81.1 | 29.6 |

| iXWX13-1 | 6.53 | 116.0 | 115.9 | 23.8 | 120.3 | 77.8 | 32.9 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 6.72 | 116.0 | 115.2 | 23.6 | 125.3 | 79.6 | 31.8 | |

| Yueyang | XWX13 | 8.19 | 115.0 | 116.5 | 24.1 | 120.3 | 84.1 | 33.2 |

| iXWX13-1 | 8.15 | 115.0 | 115.3 | 24.3 | 125.3 | 82.6 | 33.2 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 8.25 | 115.0 | 114.8 | 24.4 | 124.8 | 82.4 | 33.1 | |

| Yichun | XWX13 | 7.99 | 125.0 | 133.0 | 23.8 | 144.9 | 82.1 | 28.3 |

| iXWX13-1 | 7.89 | 130.0 | 128.4 | 21.9 | 140.7 | 74.2 | 27.6 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 8.05 | 132.0 | 128.8 | 22.8 | 142.5 | 76.4 | 28.1 | |

| Shangrao | XWX13 | 7.13 | 128.0 | 95.5 | 21.2 | 152.8 | 76.3 | 25.1 |

| iXWX13-1 | 6.93 | 136.0 | 91.5 | 22.4 | 141.1 | 76.6 | 27.2 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 7.15 | 134.0 | 91.2 | 21.8 | 150.4 | 77.4 | 26.8 | |

| Hezhou | XWX13 | 7.49 | 118.0 | 115.2 | 23.9 | 118.5 | 81.9 | 33.5 |

| iXWX13-1 | 7.34 | 118.0 | 112.6 | 24.1 | 127.4 | 79.3 | 33.0 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 7.37 | 118.0 | 111.6 | 23.6 | 122.4 | 79.1 | 33.3 | |

| Mean | XWX13 | 7.50 | 120.4 | 115.3 | 23.3 | 132.9 | 81.1 | 30.0 |

| iXWX13-1 | 7.37 | 123.0 | 112.7 | 23.3 | 131.0 | 78.1 | 30.8 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 7.51 | 123.0 | 112.3 | 23.2 | 133.1 | 79.0 | 30.6 | |

| F | 0.076 | 0.163 | 0.071 | 0.005 | 0.044 | 1.515 | 0.097 | |

| p-value | 0.927 | 0.851 | 0.931 | 0.995 | 0.957 | 0.259 | 0.909 | |

| Student-Newman-Keuls (p=0.05) | 0.936 | 0.875 | 0.935 | 0.996 | 0.962 | 0.247 | 0.910 | |

| Sites | Entries | BRP | MRP | HRP | CRP | CD | RGL | L/W | ASV | AC | GC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changsha | XWX13 | 80.5 | 70.4 | 55.1 | 11.4 | 2.7 | 6.9 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 14.6 | 48.8 |

| iXWX13-1 | 80.7 | 70.9 | 54.0 | 14.5 | 2.5 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 14.7 | 46.0 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 80.7 | 70.8 | 54.7 | 12.0 | 2.6 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 14.6 | 47.0 | |

| Yueyang | XWX13 | 79.0 | 71.8 | 65.3 | 8.3 | 2.2 | 6.9 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 14.2 | 44.8 |

| iXWX13-1 | 79.5 | 71.5 | 62.0 | 8.4 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 14.5 | 55.5 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 79.2 | 71.7 | 64.3 | 9.0 | 2.1 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 14.4 | 50.0 | |

| Yichun | XWX13 | 79.0 | 70.6 | 63.0 | 7.2 | 2.3 | 6.8 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 14.0 | 51.5 |

| iXWX13-1 | 79.3 | 70.9 | 63.9 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 6.6 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 55.0 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 79.4 | 70.8 | 63.6 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 15.5 | 54.0 | |

| Shangrao | XWX13 | 80.9 | 72.1 | 60.7 | 21.6 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 14.6 | 44.0 |

| iXWX13-1 | 80.9 | 71.5 | 56.1 | 22.9 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 16.5 | 45.0 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 80.5 | 71.8 | 58.5 | 22.0 | 4.9 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 16.3 | 44.0 | |

| Hezhou | XWX13 | 80.0 | 70.3 | 49.6 | 11.4 | 2.6 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 14.9 | 60.8 |

| iXWX13-1 | 80.3 | 70.7 | 41.3 | 16.8 | 3.3 | 6.6 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 16.3 | 65.8 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 80.4 | 70.9 | 44.8 | 13.0 | 2.8 | 6.6 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 16.2 | 64.0 | |

| Mean | XWX13 | 79.88 | 71.04 | 58.74 | 11.98 | 3.06 | 6.88 a | 3.36 a | 2.50 | 14.46 | 49.98 |

| iXWX13-1 | 80.14 | 71.10 | 55.46 | 13.40 | 2.78 | 6.58 b | 3.20 b | 2.48 | 15.60 | 53.46 | |

| iXWX13-2 | 80.04 | 71.20 | 57.18 | 12.20 | 2.78 | 6.68 b | 3.20 b | 2.46 | 15.40 | 51.80 | |

| F | 0.149 | 0.088 | 0.221 | 0.070 | 0.073 | 13.462 | 5.565 | 0.003 | 3.135 | 0.256 | |

| p-value | 0.863 | 0.916 | 0.805 | 0.932 | 0.930 | 0.001* | 0.019* | 0.997 | 0.080 | 0.778 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).