Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Equipment

2.2. Stimuli

2.2.1. Sentences

2.2.2. Noise

2.2.3. Scoring

2.3. Procedures

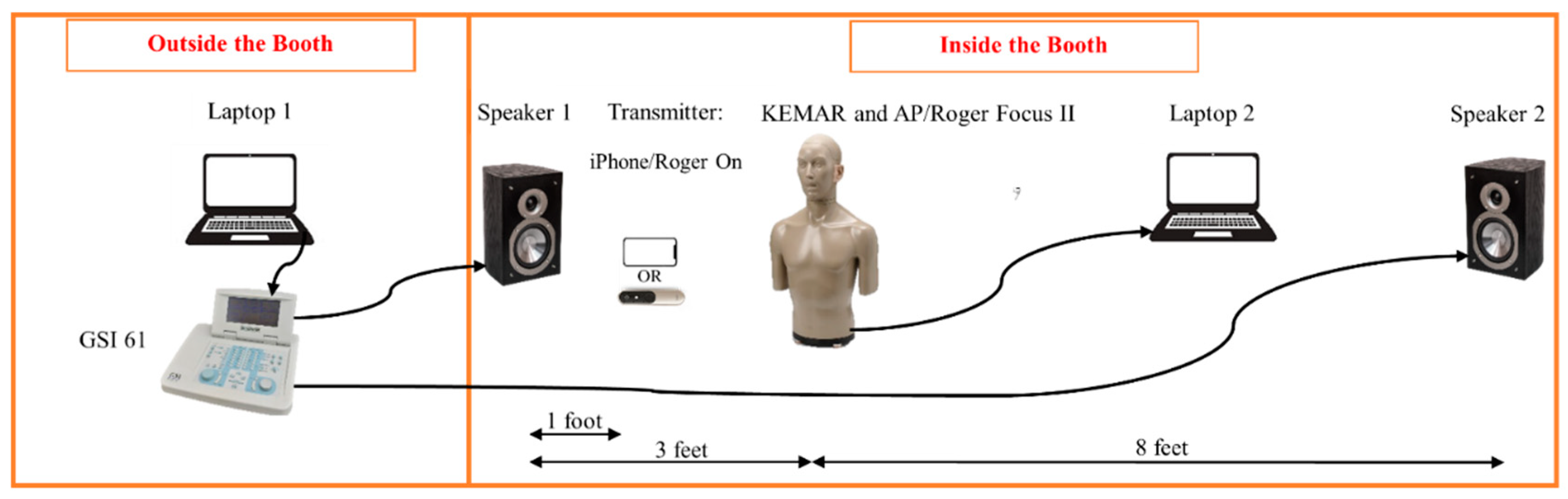

2.3.1. Setup

2.3.2. Test conditions

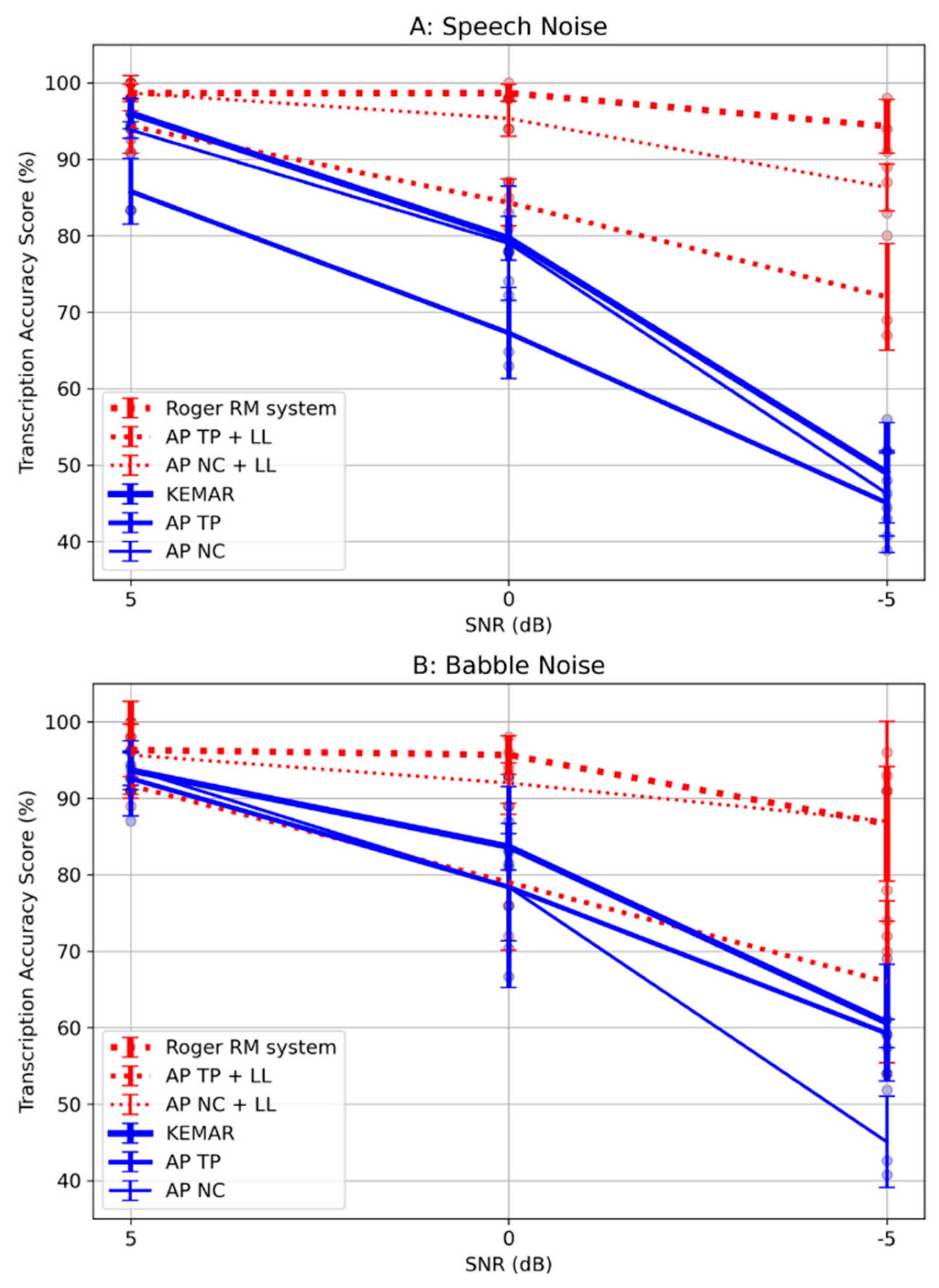

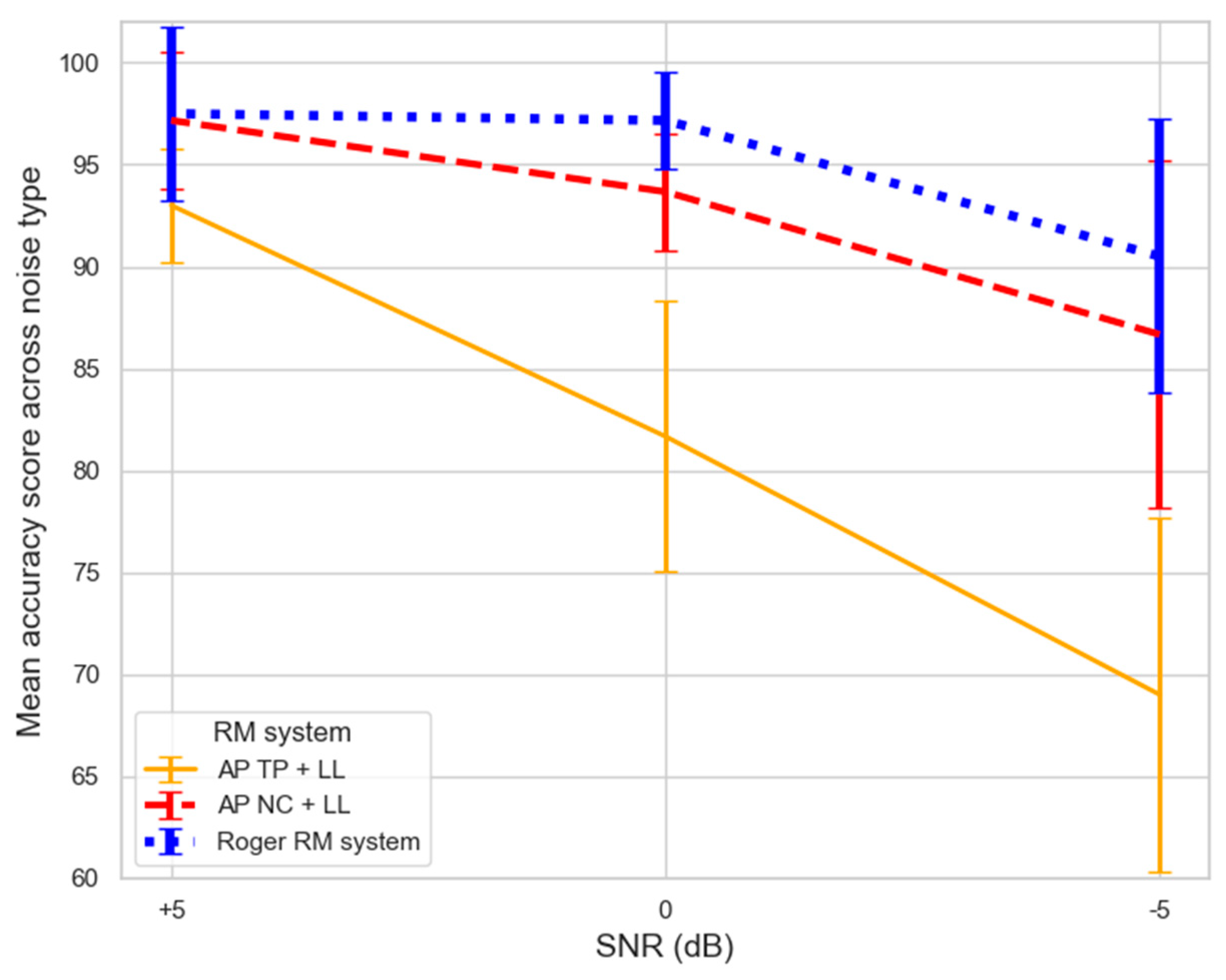

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | AirPods Pro |

| AP 2 | AirPods Pro 2 |

| BKB | Bamford-Kowal-Bench |

| CB | Conversation Boost |

| HA | Hearing aid |

| HINT | Hearing in noise test |

| KEMAR | Knowles Electronics Manikin for Acoustic Research |

| LL | Live listen |

| MHINT | Mandarin hearing in noise test |

| NAL-NL2 | National Acoustics Laboratories-Non-Linear prescription, 2nd generation |

| NC | Noise cancellation |

| OTC | Over-the-counter |

| PSAP | Personal sound amplification products |

| RM | Remote microphone |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| SRT | speech reception threshold |

| TP | Transparency |

| TH | Typical hearing |

| VTT | Voice-to-text |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Noise | Condition | SNR | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speech | Roger | +5 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 100.00 | 98.67 | 1.15 |

| Speech | Roger | 0 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 100.00 | 98.67 | 1.15 |

| Speech | Roger | -5 | 98.00 | 91.00 | 94.00 | 94.33 | 3.51 |

| Speech | AP TP + LL | +5 | 91.00 | 98.00 | 94.00 | 94.33 | 3.51 |

| Speech | AP TP + LL | 0 | 81.00 | 87.00 | 85.00 | 84.33 | 3.06 |

| Speech | AP TP + LL | -5 | 69.00 | 80.00 | 67.00 | 72.00 | 7.00 |

| Speech | AP NC + LL | +5 | 96.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 98.67 | 2.31 |

| Speech | AP NC + LL | 0 | 94.00 | 98.00 | 94.00 | 95.33 | 2.31 |

| Speech | AP NC + LL | -5 | 83.00 | 87.00 | 89.00 | 86.33 | 3.06 |

| Speech | KEMAR | +5 | 96.00 | 94.00 | 98.00 | 96.00 | 2.00 |

| Speech | KEMAR | 0 | 78.00 | 78.00 | 83.00 | 79.67 | 2.89 |

| Speech | KEMAR | -5 | 43.00 | 56.00 | 48.00 | 49.00 | 6.56 |

| Speech | AP TP | +5 | 90.74 | 83.33 | 83.33 | 85.80 | 4.28 |

| Speech | AP TP | 0 | 62.96 | 64.81 | 74.07 | 67.28 | 5.95 |

| Speech | AP TP | -5 | 44.44 | 51.85 | 38.89 | 45.06 | 6.50 |

| Speech | AP NC | +5 | 94.44 | 94.44 | 92.59 | 93.83 | 1.07 |

| Speech | AP NC | 0 | 87.04 | 72.22 | 77.78 | 79.01 | 7.48 |

| Speech | AP NC | -5 | 51.85 | 40.74 | 46.30 | 46.30 | 5.56 |

| Babble | Roger | +5 | 89.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 96.33 | 6.35 |

| Babble | Roger | 0 | 93.00 | 98.00 | 96.00 | 95.67 | 2.52 |

| Babble | Roger | -5 | 78.00 | 91.00 | 91.00 | 86.67 | 7.51 |

| Babble | AP TP + LL | +5 | 91.00 | 93.00 | 91.00 | 91.67 | 1.15 |

| Babble | AP TP + LL | 0 | 72.00 | 89.00 | 76.00 | 79.00 | 8.89 |

| Babble | AP TP + LL | -5 | 54.00 | 70.00 | 74.00 | 66.00 | 10.58 |

| Babble | AP NC + LL | +5 | 91.00 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 95.67 | 4.04 |

| Babble | AP NC + LL | 0 | 89.00 | 93.00 | 94.00 | 92.00 | 2.65 |

| Babble | AP NC + LL | -5 | 72.00 | 93.00 | 96.00 | 87.00 | 13.08 |

| Babble | KEMAR | +5 | 94.00 | 91.00 | 96.00 | 93.67 | 2.52 |

| Babble | KEMAR | 0 | 81.00 | 83.00 | 87.00 | 83.67 | 3.06 |

| Babble | KEMAR | -5 | 54.00 | 59.00 | 69.00 | 60.67 | 7.64 |

| Babble | AP TP | +5 | 94.44 | 96.30 | 87.04 | 92.59 | 4.90 |

| Babble | AP TP | 0 | 92.59 | 66.67 | 75.93 | 78.40 | 13.14 |

| Babble | AP TP | -5 | 57.41 | 59.26 | 61.11 | 59.26 | 1.85 |

| Babble | AP NC | +5 | 92.59 | 92.59 | 96.30 | 93.83 | 2.14 |

| Babble | AP NC | 0 | 70.37 | 81.48 | 83.33 | 78.40 | 7.01 |

| Babble | AP NC | -5 | 40.74 | 51.85 | 42.59 | 45.06 | 5.95 |

References

- Tremblay, K. L.; Pinto, A.; Fischer, M. E.; Klein, B. E. K.; Klein, R.; Levy, S.; Tweed, T. S.; Cruickshanks, K. J. Self-Reported Hearing Difficulties among Adults with Normal Audiograms: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Ear Hear 2015, 36, e290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spankovich, C.; Gonzalez, V. B.; Su, D.; Bishop, C. E. Self Reported Hearing Difficulty, Tinnitus, and Normal Audiometric Thresholds, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Hearing Research 2018, 358, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice guidelines and standards. American Academy of Audiology. Available online: https://www.audiology.org/practice-resources/practice-guidelines-and-standards/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- ASHA practice policy. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Available online: https://www.asha.org/policy/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Position statement: Preventing noise-induced occupational hearing loss. American Academy of Audiology. Available online: https://www.audiology.org/practice-guideline/position-statement-preventing-noise-induced-occupational-hearing-loss/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Mealings, K.; Yeend, I.; Valderrama, J. T.; Gilliver, M.; Pang, J.; Heeris, J.; Jackson, P. Discovering the Unmet Needs of People with Difficulties Understanding Speech in Noise and a Normal or Near-Normal Audiogram. American Journal of Audiology 2020, 29, 329–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, L. M. Between the Listener and the Talker: Connectivity Options. Semin Hear 2020, 41, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibodeau, L. M. Benefits in Speech Recognition in Noise with Remote Wireless Microphones in Group Settings. J Am Acad Audiol 2020, 31, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, L. M.; Land, V.; Sivaswami, A.; Qi, S. Benefits of Speech Recognition in Noise Using Remote Microphones for People with Typical Hearing. Journal of Communication Disorders 2024, 106467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, L.; Tomlin, D.; Rance, G. The Assistive Benefits of Remote Microphone Technology for Normal Hearing Children with Listening Difficulties. Ear and Hearing 2023, 44, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealings, K.; Valderrama, J. T.; Mejia, J.; Yeend, I.; Beach, E. F.; Edwards, B. Hearing Aids Reduce Self-Perceived Difficulties in Noise for Listeners with Normal Audiograms. Ear Hear 2024, 45, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J. C.; de Araujo, C. M.; Lüders, D.; Santos, R. S.; Moreira de Lacerda, A. B.; José, M. R.; Guarinello, A. C. The Self-Stigma of Hearing Loss in Adults and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Ear Hearing 2023, 44, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, N.; Bhat, G. S.; Panahi, I. M. S.; Tittle, S.; Thibodeau, L. M. Smartphone-Based Single-Channel Speech Enhancement Application for Hearing Aids. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2021, 150, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobile fact sheet. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Thibodeau, L. M.; Panahi, I. Smartphone Technology: The Hub of a Basic Wireless Accessibility Plan. The Hearing Journal 2021, 74, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA authorizes first over-the-counter hearing aid software. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-first-over-counter-hearing-aid-software (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Gilmore, J. N. Design for Everyone: Apple AirPods and the Mediation of Accessibility. Critical Studies in Media Communication 2019, 36, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.; Dunn, A. Assistive listening device for children - roger focus II. Phonak. Available online: https://www.phonak.com/content/dam/phonak/en/evidence-library/field-studies/PH_FSN_Roger_Focus_II_in_children_with_%20UHL_210x280_EN_V1.00.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Lin, H.-Y. H.; Lai, H.-S.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Wu, S.-L.; Chu, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-F.; Lai, Y.-H.; Cheng, Y.-F. Smartphone-Bundled Earphones as Personal Sound Amplification Products in Adults with Sensorineural Hearing Loss. iScience 2022, 25, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, E.; Diedesch, A. C. Usability and Perceived Benefit of Hearing Assistive Features on Apple AirPods Pro. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics 2023, 51, 050004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S. Evaluating apple AirPods pro 2 hearing protection and listening. The Hearing Review. Available online: https://hearingreview.com/inside-hearing/research/evaluating-apple-airpods-pro-2-for-hearing-protection-and-listening (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Valderrama, J. T.; Mejia, J.; Wong, A.; Chong-White, N.; Edwards, B. The Value of Headphone Accommodations in Apple Airpods pro for Managing Speech-in-Noise Hearing Difficulties of Individuals with Normal Audiograms. International Journal of Audiology 2024, 63, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-Y.; Yun, H. J.; Jo, M.; Jo, S.; Cho, Y. S.; Moon, I. J. Apple AirPods pro as a Hearing Assistive Device in Patients with Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss. Yonsei Medical Journal 2024, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroogozar, M. Assessing the Influence of Apple AirPods with Live Listen Feature on Speech Recognition and Memory Retention in Noise Levels Simulating Noisy Healthcare Settings - Insights from QuickSIN; Arizona State University, 2024; Available online: https://keep.lib.asu.edu/items/193345 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Goldenthal, E.; Park, J.; Liu, S. X.; Mieczkowski, H.; Hancock, J. T. Not All AI Are Equal: Exploring the Accessibility of AI-Mediated Communication Technology. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 125, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, P. Accuracy of Speech-to-Text Captioning for Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. Journal of Educational, Pediatric & (Re)Habilitative Audiology 2021, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Soli, S. D.; Sullivan, J. A. Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for the Measurement of Speech Reception Thresholds in Quiet and in Noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1994, 95, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, J.; Rance, G. Functional Hearing in the Classroom: Assistive Listening Devices for Students with Hearing Impairment in a Mainstream School Setting. International Journal of Audiology 2016, 55, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engen, K. J. Speech-in-Speech Recognition: A Training Study. Language and Cognitive Processes 2012, 27, (7–8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Participants | Methods | Findings | ||

| N and Age | Hearing | Devices | Tests | ||

| Lin et al. (2022) [19] |

|

Mild-to-moderate hearing loss |

|

|

|

| Hammond & Diedesch (2023) [20] |

|

7 with self-reported hearing loss and 18 with self-reported TH |

|

|

All participants felt confident in using and teaching others to use these features regardless of their hearing status.

Perceived Benefit: Overall, participants found the custom features more beneficial in quiet than in noise. Hearing-impaired participants reported greater benefit from the features in both quiet and noisy conditions compared to TH participants.

|

| Martinez (2023) [21] | None |

|

Noise attenuation of AP and AP 2 in different modes (NC, TP, and Off) under various noise conditions at different levels. |

|

|

| Valderrama et al. (2024) [22] |

|

TH but self-reported hearing difficulties in noise |

|

|

|

| Kim et al. (2024) [23] |

|

Mild to moderate hearing loss |

|

|

|

| Foroogozar (2024) [24] |

|

Normal to mild/moderate hearing loss |

|

|

The improvement in memory retention and recognition accuracy are both significant.

A positive correlation between SNR loss and recognition improvement (slope = 1.095, R² = 0.284) showed the potential of LL feature to benefit those with higher SNR loss.

|

| Function | Name | Device |

|---|---|---|

| Sentence and noise stimuli input | Laptops | ThinkPad P70 (Lenovo) |

| Otter VTT | Latitude 7480 (Dell) | |

| Stimuli transmission | Audiometer | Grason Stadler GSI 61 |

| Speakers | Two free-field corner speakers (Grason Stadler GSI) | |

| KEMAR | KEMAR Dummy-Head | |

| Transmitter | Smartphone-based RM system | iPhone 12 (IOS 15.0, Apple) |

| Receiver | Right ear AP (1st Gen., Apple) | |

| Transmitter | Phonak Roger RM system | Roger On |

| Receiver | Roger Focus II |

| Sentence played | Scoring (points) |

|---|---|

| A/The clown has/had a/the funny fac | 6 |

| The bath water is/was warm | 5 |

| She injured four of her fingers | 6 |

| He paid his bill in full | 6 |

| They stared at a/the picture | 5 |

| A/The driver started a/the car | 5 |

| A/The truck carries fresh fruit | 5 |

| A/The bottle is/was on a/the shelf | 6 |

| The small tomatoes are/were green | 5 |

| A/The dinner plate is/was hot | 5 |

| Total | 54 |

| Technology | Speech noise (dB SNR) | Babble noise (dB SNR) | Mean | ||||

| +5 | 0 | -5 | +5 | 0 | -5 | ||

| AP NC | 93.83 | 79.01 | 46.30 | 93.83 | 78.40 | 45.06 | 72.74 |

| AP TP | 85.80 | 67.28 | 45.06 | 92.59 | 78.40 | 59.26 | 71.40 |

| KEMAR | 96.00 | 79.67 | 49.00 | 93.67 | 83.67 | 60.67 | 77.11 |

| Mean | 91.88 | 75.32 | 46.79 | 93.36 | 80.16 | 55.00 | 73.75 |

| Technology | Speech noise (dB SNR) | Babble noise (dB SNR) | Mean | ||||

| +5 | 0 | -5 | +5 | 0 | -5 | ||

| AP NC + LL | 98.67 | 95.33 | 86.33 | 95.67 | 92.00 | 87.00 | 92.50 |

| AP TP + LL | 94.33 | 84.33 | 72.00 | 91.67 | 79.00 | 66.00 | 81.22 |

| Roger RM system | 98.67 | 98.67 | 94.33 | 96.33 | 95.67 | 86.67 | 95.06 |

| Mean | 97.22 | 92.78 | 84.22 | 94.56 | 88.89 | 79.89 | 89.59 |

| SNR (dB) | +5 | 0 | -5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roger RM system vs. AP NC+LL | 0.13 | 1.34 | 1.46 |

| Roger RM system vs. AP TP+LL | 1.72 | 5.92*** | 8.21*** |

| AP NC+LL vs. AP TP+LL | 1.59 | 4.58** | 6.75*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).