Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Speech Samples

2.2. Speech Intelligibility Evaluation by Naïve Listeners

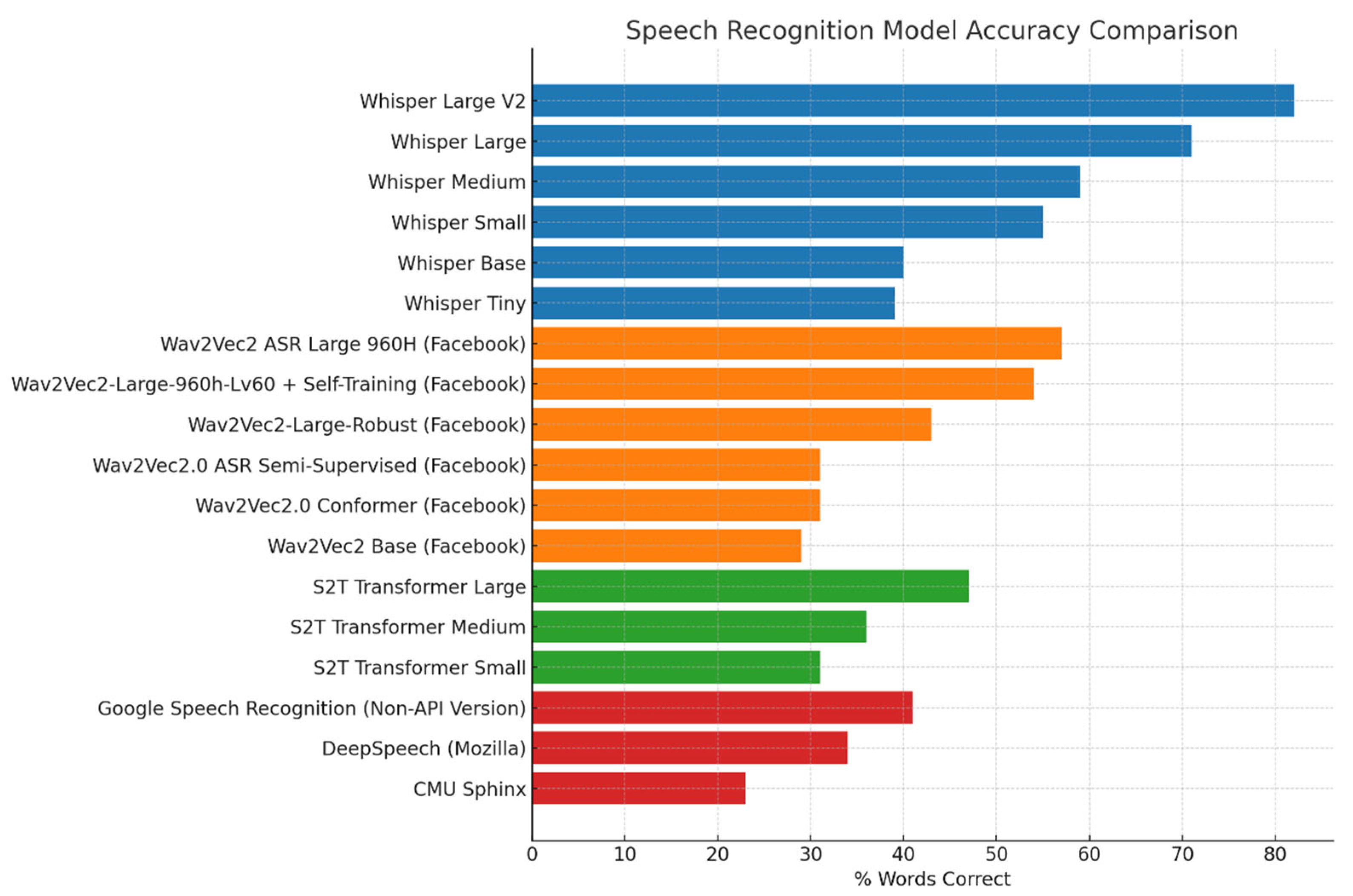

2.3. Selection of AI-Based Speech-to-Text Model

2.4. Data Scoring on the Transcriptions

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparing Word-Level Transcription: AI vs. Naïve Listeners

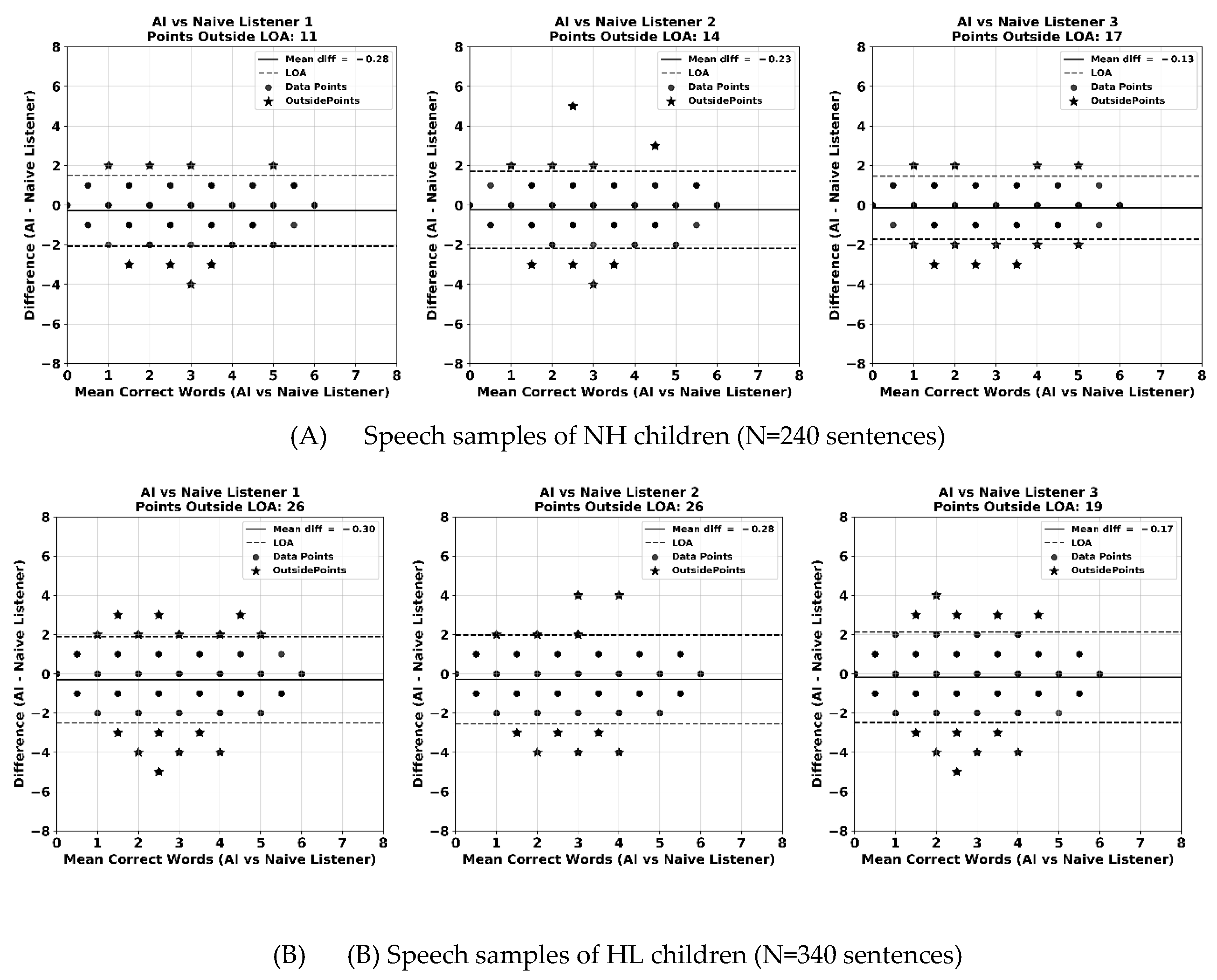

3.2. Word-Level Consistency Analysis Between the AI Model and Naive Listeners

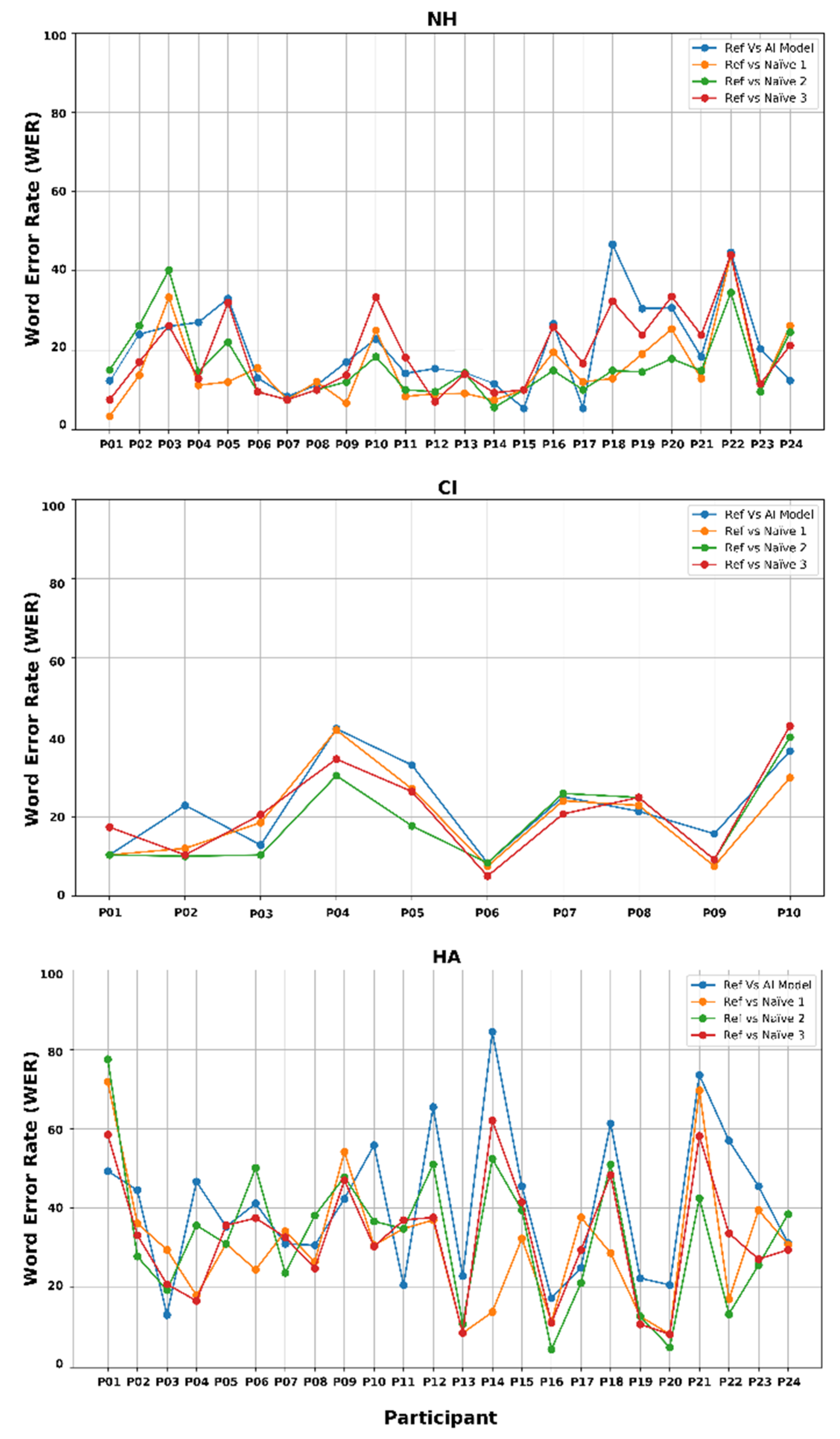

3.3. Word Error Rate Consistency Among AI and Naïve Listener Transcriptions

4. Discussion

4.1. Importance of SI Evaluation for Children with HL

4.2. Summary and Interpretation of Current Findings

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Future Clinical Application

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4FA HL | Four frequency averaged hearing loss at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ASR | Automatic speech recognition |

| BIT | Beginners Intelligibility Test |

| CIs | Cochlear implants |

| DNN | Deep neural network |

| HAs | Hearing aids |

| HL | Hearing loss |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| LoA | limits of agreement |

| NAL | National Acoustic Laboratories |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| NH | Normal hearing |

| PTA | Pure tone audiometry |

| RMS | Root-mean-square |

| RNN | Recurrent neural network |

| SI | Speech intelligibility |

| SOA | State-of-the-art |

| STT | speech-to-text |

| WER | Word Error Rate |

References

- Kent, R.D., et al., Toward phonetic intelligibility testing in dysarthria. J Speech Hear Disord, 1989. 54(4): p. 482-499.

- Ruben, R.J., Redefining the survival of the fittest: Communication disorders in the 21st century. Laryngoscope, 2000. 110(2 Pt 1): p. 241-245.

- Monsen, R.B., Toward measuring how well hearing-impaired children speak. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 1978. 21(2): p. 197-219.

- MacNeilage, P.F., The production of speech. Springer-Verlag. New York, United States. 2012.

- Montag, J.L., et al., Speech intelligibility in deaf children after long-term cochlear implant use. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 2014. 57(6): p. 2332-43.

- Weiss, C.E., . Weiss intelligibility test. C.C. Publications. Tigard, Oregon, United States. 1982.

- Coplan, J. and Gleason, J.R., Unclear speech: Recognition and significance of unintelligible speech in preschool children. Pediatrics, 1988. 82(3 Pt 2): p. 447-52.

- Gordon-Brannan, M. and Hodson, B.W., Intelligibility/severity measurements of prekindergarten children’s speech. Am J Speech Lang Pathol, 2000. 9(2): p. 141-150.

- Carney, A.E., Understanding speech intelligibility in the hearing impaired. Topics in Language Disorders, 1986. 6(3): p. 47-59.

- Osberger, M.J., et al., Speech intelligibility of children with cochlear implants. Volta Rev., 1994. 96(5): p. 12.

- Osberger, M.J., Speech intelligibility in the hearing impaired: Research and clinical implications, in Intelligibility in speech disorders: Theory, measurement and management, Kent, R.D., Editor. 2011, John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 233-264.

- Brannon Jr, J.B., Visual feedback of glossal motions and its influence upon the speech of deaf children. Northwestern University. 1964.

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C., From screening to early identification and intervention: Discovering predictors to successful outcomes for children with significant hearing loss. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ, 2003. 8(1): p. 11-30.

- Most, T., Weisel, A., and Lev-Matezky, A., Speech intelligibility and the evaluation of personal qualities by experienced and inexperienced listeners. Volta Rev., 1996. 98(4): p. 181-190.

- Most, T., Speech intelligibility, loneliness, and sense of coherence among deaf and hard-of-hearing children in individual inclusion and group inclusion. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ., 2007. 12(4): p. 495-503.

- Most, T., Ingber, S., and Heled-Ariam, E., Social competence, sense of loneliness, and speech intelligibility of young children with hearing loss in individual inclusion and group inclusion. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ, 2012. 17(2): p. 259-72.

- Most, T., Weisel, A., and Tur-Kaspa, H., Contact with students with hearing impairments and the evaluation of speech intelligibility and personal qualities J. Spec. Educ., 1999. 33(2): p. 103-111.

- Barker, D.H., et al., Predicting behavior problems in deaf and hearing children: the influences of language, attention, and parent-child communication. Dev Psychopathol, 2009. 21(2): p. 373-92.

- Hoffman, M.F., Quittner, A.L., and Cejas, I., Comparisons of social competence in young children with and without hearing loss: a dynamic systems framework. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ, 2015. 20(2): p. 115-24.

- Ertmer, D.J., Assessing speech intelligibility in children with hearing loss: Toward revitalizing a valuable clinical tool. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch, 2011. 42(1): p. 52-58.

- Kent, R.D., Miolo, G., and Bloedel, S., The intelligibility of children’s speech: A review of evaluation procedures. Am J Speech Lang Pathol, 1994. 3(2): p. 81-95.

- McGarr, N., The intelligibility of deaf speech to experienced and inexperienced listeners. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 1983. 26: p. 8.

- Chin, S.B., Tsai, P.L., and Gao, S., Connected speech intelligibility of children with cochlear implants and children with normal hearing. Am J Speech Lang Pathol, 2003. 12: p. 12.

- Flipsen Jr. P and Colvard, L.G., Intelligibility of conversational speech produced by children with cochlear implants. J Commun Disord, 2006. 39(2): p. 93-108.

- Nikolopoulos, T.P., Archbold, S.M., and Gregory, S., Young deaf children with hearing aids or cochlear implants: Early assessment package for monitoring progress. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2005. 69(2): p. 175-86.

- Samar, V.J. and Metz, D.E., Criterion validity of speech intelligibility rating-scale procedures for the hearing-impaired population. J Speech Hear Res, 1988. 31(3): p. 307-16.

- Allen, M.C., Nikolopoulos, T.P., and O'donoghue, G.M., Speech intelligibility in children after cochlear implantation. Am J Otol, 1988. 19(6): p. 742-746.

- Beadle, E.A., et al., Long-term functional outcomes and academic-occupational status in implanted children after 10 to 14 years of cochlear implant use. Otol Neurotol, 2005. 26(6): p. 1152-60.

- Chin, S.B., Bergeson, T.R., and Phan, J., Speech intelligibility and prosody production in children with cochlear implants. J Commun Disord, 2012. 45(5): p. 355-66.

- Habib, M.G., et al., Speech production intelligibility of early implanted pediatric cochlear implant users. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2010. 74(8): p. 855-9.

- Tobey, E.A., et al., Factors associated with development of speech production skills in children implanted by age five. Ear Hear, 2003. 24(1 Suppl): p. 36S-45S.

- Halpern, B.M., et al., Automatic evaluation of spontaneous oral cancer speech using ratings from naive listeners. Speech Communication, 2023. 149(Apr): p. 84-97.

- Martinez, A.M.C., et al., Prediction of speech intelligibility with DNN-based performance measures. Comput. Speech Lang., 2022. 74(March): p. 34.

- Araiza-Illan, G., et al., Automated speech audiometry: Can it work using open-source pre-trained Kaldi-NL automatic speech recognition?. , 28, 23312165241229057. Trends Hear, 2024. 28: p. 13.

- Le, D., et al., Automatic assessment of speech intelligibility for individuals with Aphasia. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process, 2016. 24(11): p. 2187-2199.

- Herrmann, B., The perception of artificial-intelligence (AI) based synthesized speech in younger and older adults. Int J Speech Technol, 2023. 26(2): p. 395-415.

- Miyamoto, R.T., et al., Speech intelligibility of children with multichannel cochlear implants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl, 1997. 168: p. 35-6.

- Ching, T.Y., Leigh, G., and Dillon, H., Introduction to the longitudinal outcomes of children with hearing impairment (LOCHI) study: background, design, sample characteristics. Int J Audiol, 2013. 52 Suppl 2(Suppl 2): p. S4-9.

- Wechsler, D. and Naglieri, J.A., Wechsler Nonverbal Scale of Ability. Harcourt Assessment. San Antonio, TX. 2006.

- Zimmerman, I., Steiner, V.G., and Pond, R.E., Preschool Language Scale. 4th ed. The Psychological Corporation. San Antonio, TX. 2002.

- Ching, T.Y., et al., Factors influencing speech perception in noise for 5-year-old children using hearing aids or cochlear implants. Int J Audiol, 2018. 57(sup2): p. S70-S80.

- Lai, W.K. and Dillier, N., MACarena: A flexible computer-based speech testing environment, in 7th International Cochlear Implant Conference. 2002: Manchester, England.

- Yeung, G. and Alwan, A., On the difficulties of automatic speech recognition for kindergarten-aged children, in Proceedings of the Interspeech. 2018: Hyderabad, India. p. 1661-1665.

- Miller, J.F., Andriacchi, K., and Nockerts, A., Using language sample analysis to assess spoken language production in adolescents. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch, 2016. 47(2): p. 99-112.

- Hannun, A., et al. Deep speech: Scaling up end-to-end speech recognition. 2014. 1-12.

- Poursoroush, S., et al., Speech intelligibility of cochlear-implanted and normal-hearing children. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol, 2015. 27(82): p. 361-7.

- IBM Corp., IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 29.0). 2022, IBM Corp.: Armonk, New York, United States.

- Bland, J.M. and Altman, D.G., Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet, 1986. 1(8476): p. 307-10.

- Koo, T.K. and Li, M.Y., A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med, 2016. 15(2): p. 155-63.

- Spille, C., Kollmeier, B., and Meyer, B.T., Comparing human and automatic speech recognition in simple and complex acoustic scene. Comput. Speech Lang., 2018. 52(2018): p. 123-140.

- Way With Words. Word error rate: Assessing transcription service accuracy. Available online: https://waywithwords.net/resource/word-error-rate-transcription-accuracy/. accessed on 18/6/2025.

- Geers, A.E., Factors affecting the development of speech, language, and literacy in children with early cochlear implantation. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch, 2002. 33(3): p. 172-183.

- Geers, A., et al., Educational factors contributing to cochlear implant benefit in children. International Congress Series, 2003. 154(November): p. 6.

- Tobey, E.A., et al., Factors influencing speech production in elementary and high school-aged cochlear implant users. Ear Hear, 2011. 32(1 Suppl): p. 27S-38S.

- Zhang, V.W., et al., Speech intelligibility outcome of 5-year-old children with severe to profound hearing loss, in 12th Asia Pacific Symposium on Cochlear Implants and Related Sciences (APSCI). 2019: Tokyo, Japan.

- Monaghan, J., et al. Automatic detection of hearing loss from children's speech using wav2vec 2.0 features. in Proceedings of the Interspeech. 2024.

| Characters |

Cochlear Implant (CI) (n =10) |

Hearing Aid (HA) (n = 24) |

Normal Hearing (NH) (n=24) |

| Age at BIT assessment (months), Mean (SD) | 61.4 (1.6) | 61.4 (1.4) | 61.5 (1.5) |

| Gender (Male), n (%) | 3 (30.0%) | 10 (41.7%) | 10 (41.7%) |

| Degree of hearing loss at BIT assessment (4FA HL in better ear), Mean (SD) | 109 (18.4) | 52 (15.1) | na |

| Age at hearing aids fitting, Mean (SD) | 5.3 (5.3) | 5.2 (6.0) | na |

| Age at cochlear implantation, Mean (SD) | 21.8 (16.5) | na | na |

| Nonverbal cognitive ability*, Mean (SD) | 102.2 (14.7) | 92 (13.5) | 103. 9 (15.8) |

| Language score*, Mean (SD) | 104.7 (9.7) | 110.2 (11.9) | 104.6 (9.8) |

| Hearing Group | Comparison | ICC value | 95% confidence interval | F (df1, df2) | p-value |

| NH group (n=240sentences) |

Within naïve listeners only | 0.95 | [0.94, 0.96] | F (239, 478) = 20.8 | < 0.001 |

| AI model vs naïve listeners | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.96] | F (239, 717) = 22.4 | ||

| HL group (CI and HA) (n=340 sentences) |

Within naïve listeners only | 0.92 | [0.90, 0.93] | F (339, 678) = 11.7 | |

| AI model vs naïve listeners | 0.93 | [0.91, 0.94] | F (339, 1017) = 13.8 | ||

| CIs group only (n=100 sentences) |

Within naïve listeners only | 0.96 | [0.94, 0.97] | F (99, 198) = 20.8 | |

| AI model vs naïve listeners | 0.96 | [0.94, 0.97] | F (99, 297) = 22.1 | ||

| HAs group only (n=240 sentences) |

Within naïve listeners only | 0.90 | [0.87, 0.92] | F (239, 478) = 9.6 | |

| AI model vs naïve listeners | 0.91 | [0.89, 0.93] | F (239, 717) = 11.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).