Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How do teenagers and young adults who received their 1st CI before 30 months perform long-term in linguistics, cognition, hearing, balance, self-efficacy and health related quality of life, in comparison to age-matched controls with typical hearing?

- How do adolescents and young adults with CIs perceive their listening and communication experiences in different everyday life situations and activities (school, work, leisure), in relation to controls with typical hearing?

- Hypotheses:

- Q1: Age at 1st CI has an impact on long-term cognition, linguistics, hearing and HRQoL.

- Q1: Hearing outcomes are related to modifiable clinical parameters.

- Q1: Lower socio-economic status of families are related to poorer long-term outcome (cognition, language and HRQoL).

- Q1: Etiological factors affect balance, hearing, language, cognition and HRQoL.

- Q2: Self-perceived HRQoL is positively affected in adolescents and young adults with CI if they have acquired age-equivalent language skills and is related to better hearing.

- Q2: The overall HRQoL outcome in adolescents and young adults with CI is similar to that of age-matched controls with typical hearing (TH).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Brief Prospective Project Overview

2.3. Participants

2.4. Descriptions of Material and Procedures Used in Sub-Studies (I-V)

2.4.1. Sub-Study I: Language and Cognition

2.4.2. Sub-Study II: Hearing and Listening

Hearing thresholds

Recognition of words in quiet

Recognition of sentences in masking speech and spatial release from masking

Horizontal sound localization accuracy

Interaural level and time differences

Assessment of programming levels and objective and behaviorally assessed thresholds

Spectral discrimination

Photon-counting computer tomography

2.4.3. Sub-Study III: Balance

2.4.4. Sub-Study IV: Etiology

2.4.5. Sub-Study V: Mental Health and Health-Related Quality of Life

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

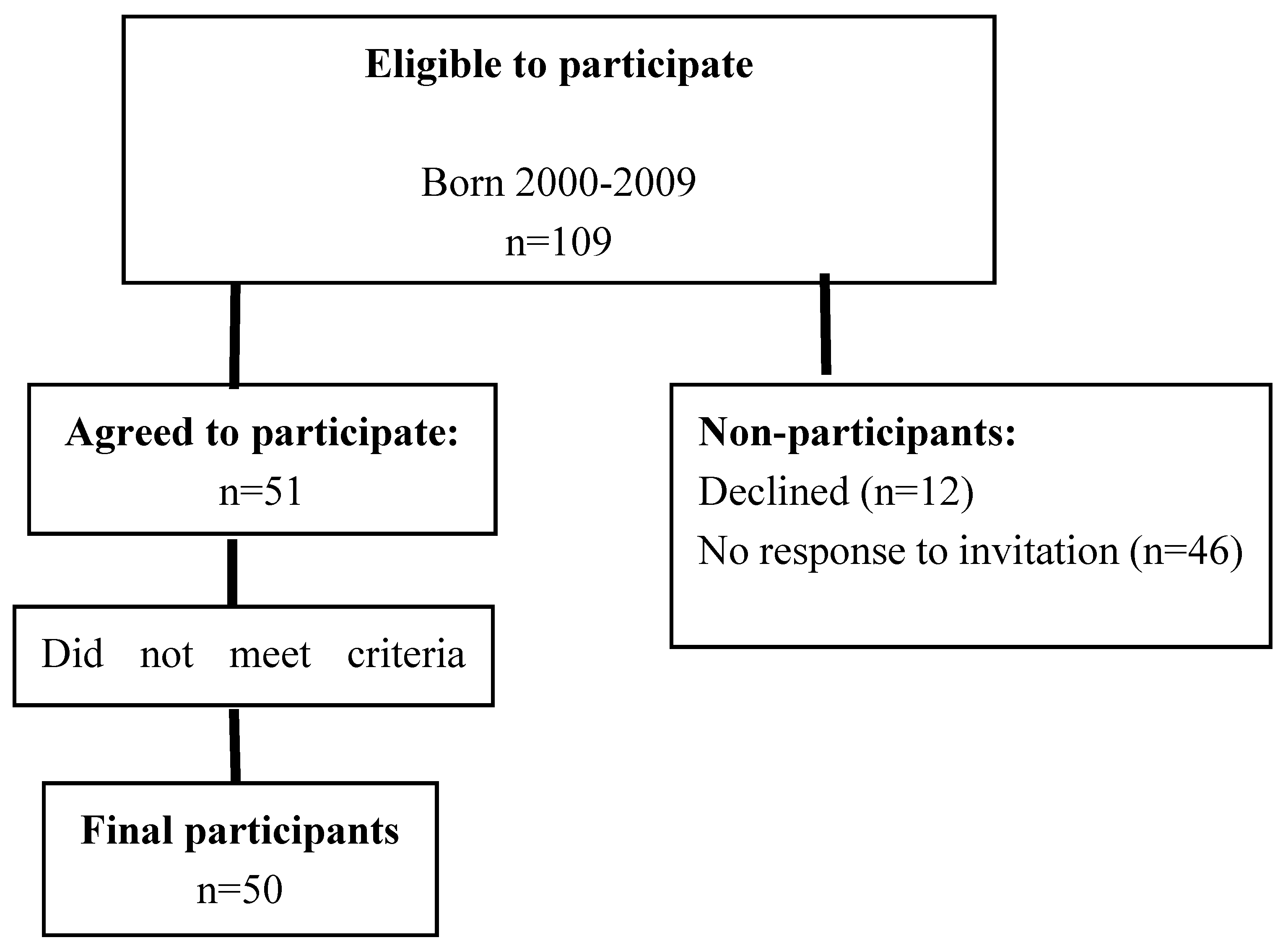

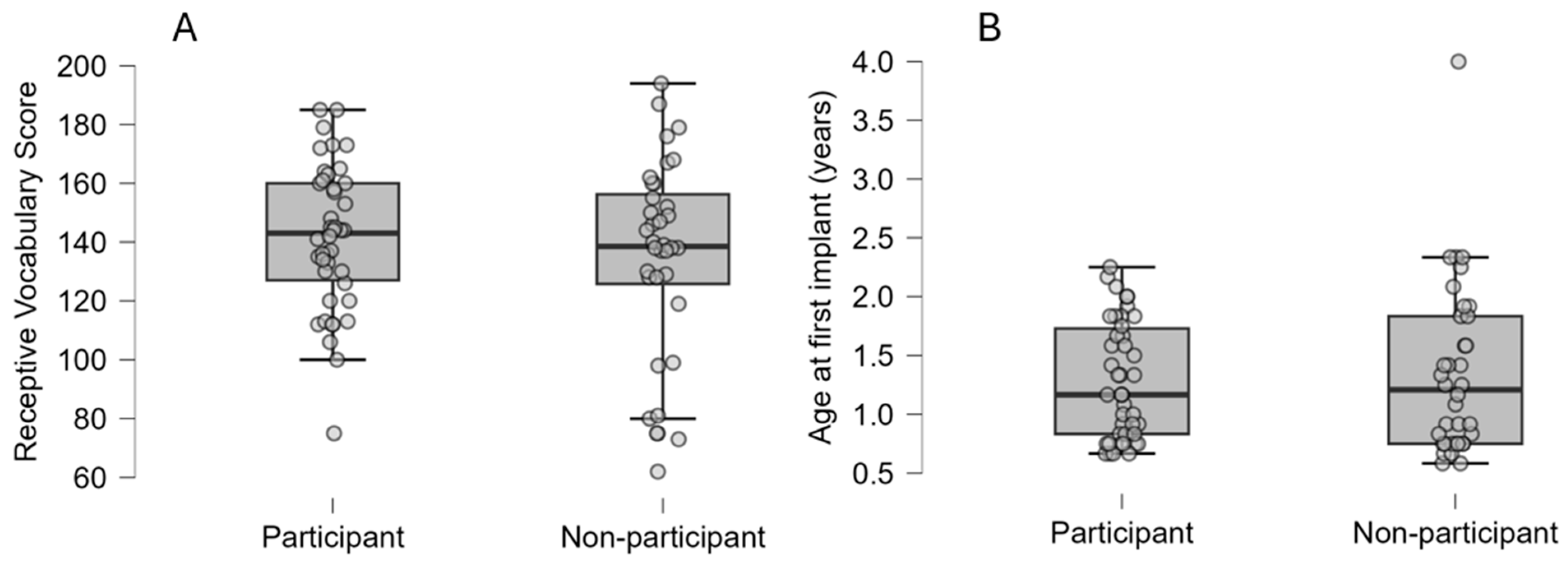

3.1. Representativeness of Study Sample

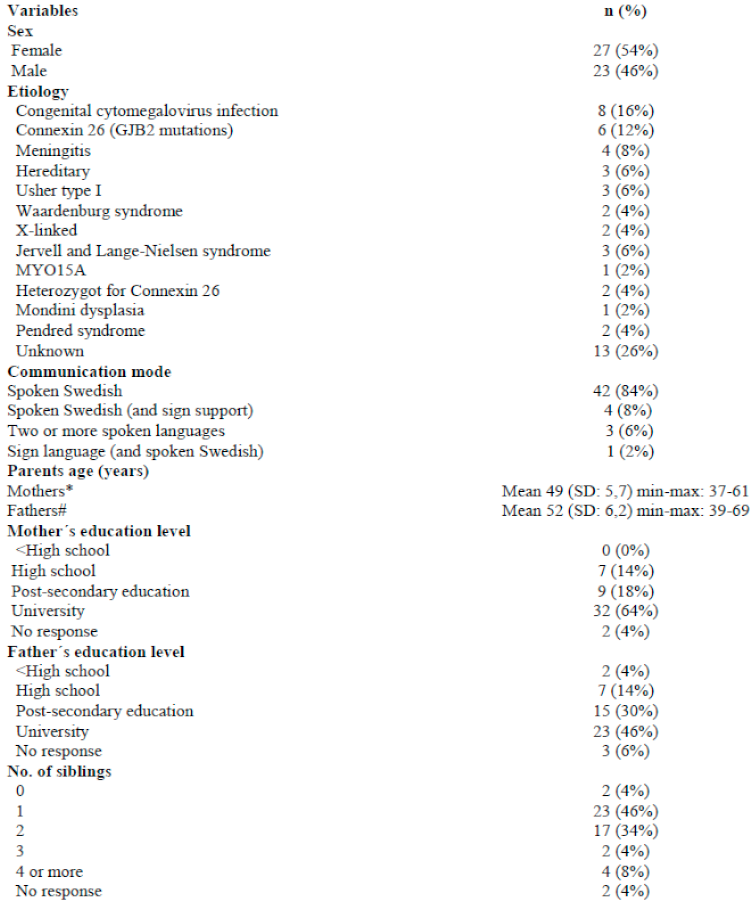

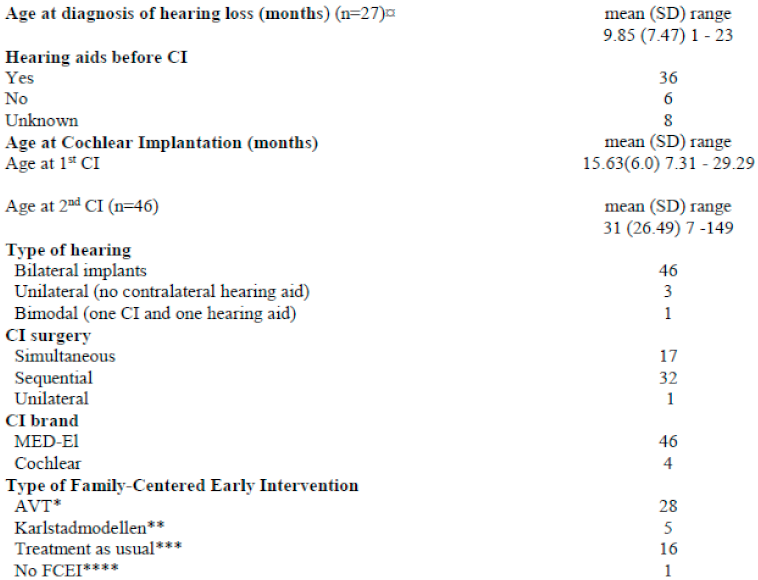

3.2. Characteristics of Participants with CI and Their Families

3.3. Early Follow-Up Procedures and Habilitation Actions After First CI

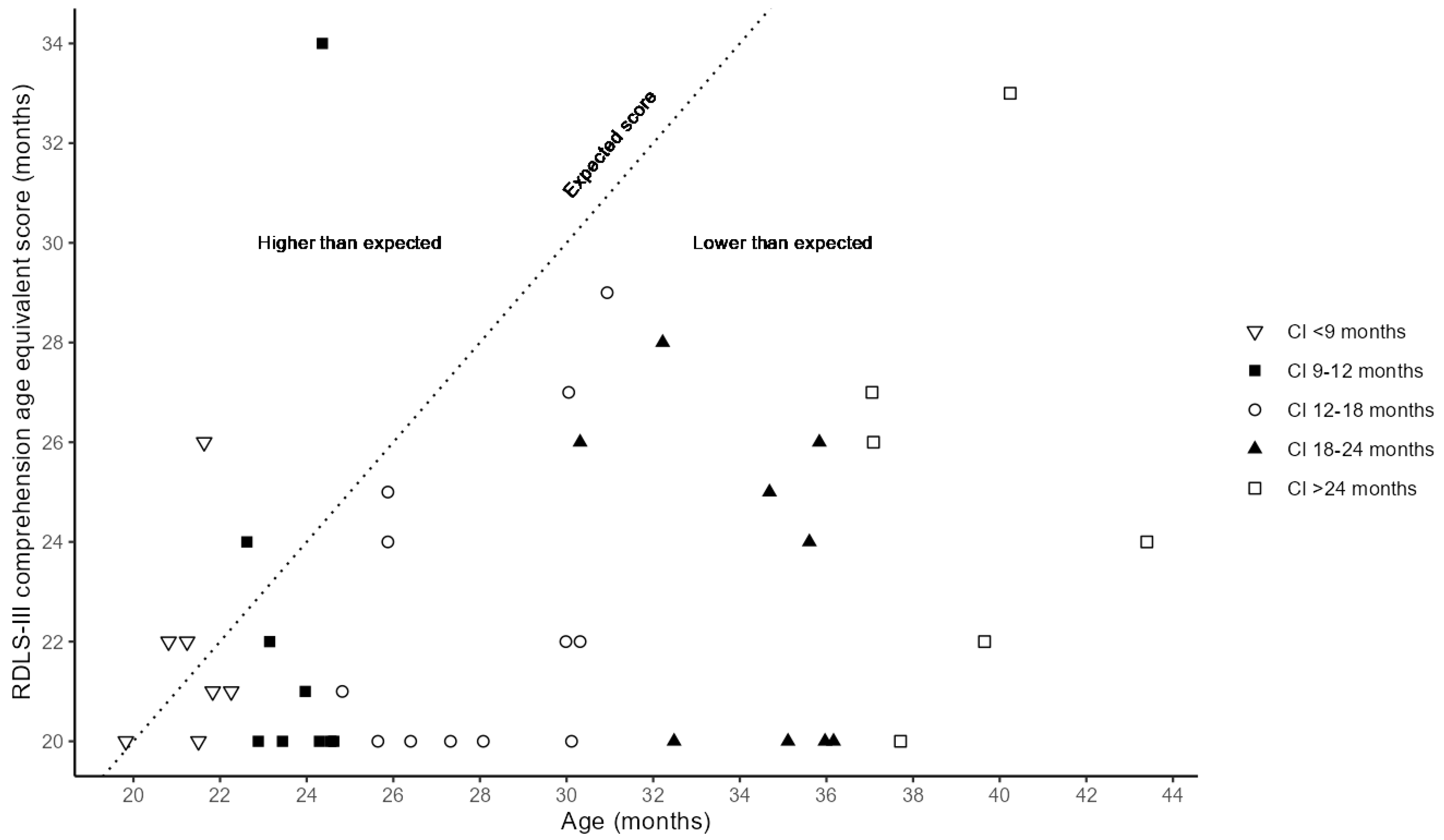

3.4. Language Understanding After One Year with First CI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dettman SJ, Dowell RC, Choo D, Arnott W, Abrahams Y, Davis A, et al. Long-term Communication Outcomes for Children Receiving Cochlear Implants Younger Than 12 Months: A Multicenter Study. Otology & Neurotology 2016;37:e82–95. [CrossRef]

- Geers AE, Strube MJ, Tobey EA, Pisoni DB, Moog JS. Epilogue: Factors Contributing to Long-Term Outcomes of Cochlear Implantation in Early Childhood. Ear & Hearing 2011;32:84S-92S. [CrossRef]

- Cejas I, Barker DH, Petruzzello E, Sarangoulis CM, Quittner AL. Cochlear Implantation and Educational and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Adolescence. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2023;149:708. [CrossRef]

- Marschark M, Duchesne L, Pisoni D. Effects of Age at Cochlear Implantation on Learning and Cognition: A Critical Assessment. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2019;28:1318–34. [CrossRef]

- Hickson, L., Wong, L. Evidence Based Practice in Audiology: Evaluating Interventions for Children and Adults with Hearing Impairment. Plural Publishing; 1st Edition.; 2012.

- Ching TYC, Dillon H, Button L, Seeto M, Van Buynder P, Marnane V, et al. Age at Intervention for Permanent Hearing Loss and 5-Year Language Outcomes. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20164274. [CrossRef]

- Asp F, Mäki-Torkko E, Karltorp E, Harder H, Hergils L, Eskilsson G, et al. Bilateral versus unilateral cochlear implants in children: Speech recognition, sound localization, and parental reports. International Journal of Audiology 2012;51:817–32. [CrossRef]

- Asp F, Mäki-Torkko E, Karltorp E, Harder H, Hergils L, Eskilsson G, et al. A longitudinal study of the bilateral benefit in children with bilateral cochlear implants. International Journal of Audiology 2015;54:77–88. [CrossRef]

- Karltorp E, Eklöf M, Östlund E, Asp F, Tideholm B, Löfkvist U. Cochlear implants before 9 months of age led to more natural spoken language development without increased surgical risks. Acta Paediatr 2020;109:332–41. [CrossRef]

- Löfkvist, U., Östlund, E., Karltorp, E., Eklöf, M. Multilingual children with cochlear implants in Sweden: a longitudinal follow-up study. (In Manuscript) n.d.

- Amundsen VV, Wie OB, Myhrum M, Bunne M. The impact of ethnicity on cochlear implantation in Norwegian children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2017;93:30–6. [CrossRef]

- Clauss-Ehlers CS, Chiriboga DA, Hunter SJ, Roysircar G, Tummala-Narra P. APA Multicultural Guidelines executive summary: Ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. American Psychologist 2019;74:232–44. [CrossRef]

- Szagun G, Stumper B. Age or Experience? The Influence of Age at Implantation and Social and Linguistic Environment on Language Development in Children With Cochlear Implants. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2012;55:1640–54. [CrossRef]

- Uhlén I, Mackey A, Rosenhall U. Prevalence of childhood hearing impairment in the County of Stockholm – a 40-year perspective from Sweden and other high-income countries. International Journal of Audiology 2020;59:866–73. [CrossRef]

- Kral A, Sharma A. Developmental neuroplasticity after cochlear implantation. Trends in Neurosciences 2012;35:111–22. [CrossRef]

- Registret för hörselnedsättning för barn https://hnsb.registercentrum.se/: Registercentrum VGR; 2023-10-29. n.d.

- De Melo ME, Soman U, Voss J, Valencia MFH, Noll D, Clark F, et al. Listening and Spoken Language Specialist Auditory–Verbal Certification: Self-Perceived Benefits and Barriers to Inform Change. Perspect ASHA SIGs 2022;7:1828–52. [CrossRef]

- Cupples L, Ching TYC, Crowe K, Seeto M, Leigh G, Street L, et al. Outcomes of 3-Year-Old Children With Hearing Loss and Different Types of Additional Disabilities. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2014;19:20–39. [CrossRef]

- Lieu JEC, Kenna M, Anne S, Davidson L. Hearing Loss in Children: A Review. JAMA 2020;324:2195. [CrossRef]

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol 2007;17:253–76. [CrossRef]

- Vaccination coverage and impact of pneumococcal vaccine in Sweden. Retrieved from. 2019.

- Sarant JZ, Blamey PJ, Dowell RC, Clark GM, Gibson WPR. Variation In Speech Perception Scores Among Children with Cochlear Implants: Ear and Hearing 2001;22:18–28. [CrossRef]

- Houston DM, Miyamoto RT. Effects of Early Auditory Experience on Word Learning and Speech Perception in Deaf Children With Cochlear Implants: Implications for Sensitive Periods of Language Development. Otology & Neurotology 2010;31:1248–53. [CrossRef]

- Dunn CC, Walker EA, Oleson J, Kenworthy M, Van Voorst T, Tomblin JB, et al. Longitudinal Speech Perception and Language Performance in Pediatric Cochlear Implant Users: The Effect of Age at Implantation. Ear & Hearing 2014;35:148–60. [CrossRef]

- Misurelli SM, Litovsky RY. Spatial release from masking in children with normal hearing and with bilateral cochlear implants: Effect of interferer asymmetry. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2012;132:380–91. [CrossRef]

- Misurelli SM, Litovsky RY. Spatial release from masking in children with bilateral cochlear implants and with normal hearing: Effect of target-interferer similarity. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2015;138:319–31. [CrossRef]

- Lovett RES, Kitterick PT, Hewitt CE, Summerfield AQ. Bilateral or unilateral cochlear implantation for deaf children: an observational study. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2010;95:107–12. [CrossRef]

- Asp F, Eskilsson G, Berninger E. Horizontal Sound Localization in Children With Bilateral Cochlear Implants: Effects of Auditory Experience and Age at Implantation. Otology & Neurotology 2011;32:558–64. [CrossRef]

- Killan C, Scally A, Killan E, Totten C, Raine C. Factors Affecting Sound-Source Localization in Children With Simultaneous or Sequential Bilateral Cochlear Implants. Ear & Hearing 2019;40:870–7. [CrossRef]

- Verbecque E, Marijnissen T, De Belder N, Van Rompaey V, Boudewyns A, Van De Heyning P, et al. Vestibular (dys)function in children with sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review. International Journal of Audiology 2017;56:361–81. [CrossRef]

- Jacot E, Van Den Abbeele T, Debre HR, Wiener-Vacher SR. Vestibular impairments pre- and post-cochlear implant in children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2009;73:209–17. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Zhang Q, Xiao Q, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Liu S, et al. Vestibular dysfunction in pediatric patients with cochlear implantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol 2022;13:996580. [CrossRef]

- Kaga K, Suzuki J, Marsh RR, Tanaka Y. INFLUENCE OF LABYRINTHINE HYPOACTIVITY ON GROSS MOTOR DEVELOPMENT OF INFANTS. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1981;374:412–20. [CrossRef]

- Cushing SL, Papsin BC, Rutka JA, James AL, Gordon KA. Evidence of Vestibular and Balance Dysfunction in Children With Profound Sensorineural Hearing Loss Using Cochlear Implants. The Laryngoscope 2008;118:1814–23. [CrossRef]

- Wolter NE, Gordon KA, Campos J, Vilchez Madrigal LD, Papsin BC, Cushing SL. Impact of the sensory environment on balance in children with bilateral cochleovestibular loss. Hearing Research 2021;400:108134. [CrossRef]

- Braswell J, Rine RM. Evidence that vestibular hypofunction affects reading acuity in children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2006;70:1957–65. [CrossRef]

- Wolter NE, Gordon KA, Papsin BC, Cushing SL. Vestibular and Balance Impairment Contributes to Cochlear Implant Failure in Children. Otology & Neurotology 2015;36:1029–34. [CrossRef]

- Van Hecke R, Danneels M, Deconinck FJA, Dhooge I, Leyssens L, Van Acker E, et al. A cross-sectional study on the neurocognitive outcomes in vestibular impaired school-aged children: are they at higher risk for cognitive deficits? J Neurol 2023;270:4326–41. [CrossRef]

- Cushing SL, Papsin BC, Rutka JA, James AL, Blaser SL, Gordon KA. Vestibular End-Organ and Balance Deficits After Meningitis and Cochlear Implantation in Children Correlate Poorly With Functional Outcome. Otology & Neurotology 2009;30:488–95. [CrossRef]

- Suarez H, Ferreira E, Arocena S, Garcia Pintos B, Quinteros M, Suarez S, et al. Motor and cognitive performances in pre-lingual cochlear implant adolescents, related with vestibular function and auditory input. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2019;139:367–72. [CrossRef]

- Kaga K, Shinjo Y, Jin Y, Takegoshi H. Vestibular failure in children with congenital deafness. International Journal of Audiology 2008;47:590–9. [CrossRef]

- Niparko JK. Spoken Language Development in Children Following Cochlear Implantation. JAMA 2010;303:1498. [CrossRef]

- Vlastarakos PV, Proikas K, Papacharalampous G, Exadaktylou I, Mochloulis G, Nikolopoulos TP. Cochlear implantation under the first year of age—The outcomes. A critical systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2010;74:119–26. [CrossRef]

- Gooch D, Thompson P, Nash HM, Snowling MJ, Hulme C. The development of executive function and language skills in the early school years. Child Psychology Psychiatry 2016;57:180–7. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pereira M, Martínez-López Z, Maneiro L. Longitudinal Relationships Between Reading Abilities, Phonological Awareness, Language Abilities and Executive Functions: Comparison of Low Risk Preterm and Full-Term Children. Front Psychol 2020;11:468. [CrossRef]

- Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG, Roman AS, Geers AE. Measures of Digit Span and Verbal Rehearsal Speed in Deaf Children After More Than 10 Years of Cochlear Implantation. Ear & Hearing 2011;32:60S-74S. [CrossRef]

- Beer J, Kronenberger WG, Pisoni DB. Executive function in everyday life: implications for young cochlear implant users. Cochlear Implants International 2011;12:S89–91. [CrossRef]

- Nicastri M, Filipo R, Ruoppolo G, Viccaro M, Dincer H, Guerzoni L, et al. Inferences and metaphoric comprehension in unilaterally implanted children with adequate formal oral language performance. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2014;78:821–7. [CrossRef]

- Gold R, Segal O. Metaphor Comprehension by Deaf Young Adults. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2017;22:316–25. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami H, Faramarzi S, Amouzadeh M. A comparative study of metaphorical expression understanding between children with cochlear implants and normal children. AVR 2018:131–6. [CrossRef]

- Punch R, Hyde M. Social Participation of Children and Adolescents With Cochlear Implants: A Qualitative Analysis of Parent, Teacher, and Child Interviews. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2011;16:474–93. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler A, Archbold S, Gregory S, Skipp A. Cochlear Implants: The Young People’s Perspective. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2007;12:303–16. [CrossRef]

- Watson V, Verschuur C, Lathlean J. Exploring the experiences of teenagers with cochlear implants. Cochlear Implants International 2016;17:293–301. [CrossRef]

- Avenevoli S. Prevalence, Persistence, and Sociodemographic Correlates of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:372. [CrossRef]

- Wesselhoeft R, Sørensen MJ, Heiervang ER, Bilenberg N. Subthreshold depression in children and adolescents – a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 2013;151:7–22. [CrossRef]

- Hintermair Manfred. Prevalence of Socioemotional Problems in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children in Germany. American Annals of the Deaf 2007;152:320–30. [CrossRef]

- Theunissen SCPM, Rieffe C, Kouwenberg M, Soede W, Briaire JJ, Frijns JHM. Depression in hearing-impaired children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2011;75:1313–7. [CrossRef]

- Bandura A, Pastorelli C, Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV. Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1999;76:258–69. [CrossRef]

- Ambrose SE, Appenzeller M, Mai A, DesJardin JL. Beliefs and Self-Efficacy of Parents of Young Children with Hearing Loss. J Early Hear Detect Interv 2020;5:73–85.

- Cejas I, Mitchell CM, Barker DH, Sarangoulis C, Eisenberg LS, Quittner AL. Parenting Stress, Self-Efficacy, and Involvement: Effects on Spoken Language Ability Three Years After Cochlear Implantation. Otology & Neurotology 2021;42:S11–8. [CrossRef]

- Ching TYC, Dillon H, Leigh G, Cupples L. Learning from the Longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Impairment (LOCHI) study: summary of 5-year findings and implications. International Journal of Audiology 2018;57:S105–11. [CrossRef]

- Cupples L, Ching TYc, Button L, Seeto M, Zhang V, Whitfield J, et al. Spoken language and everyday functioning in 5-year-old children using hearing aids or cochlear implants. International Journal of Audiology 2018;57:S55–69. [CrossRef]

- Fink NE, Wang N-Y, Visaya J, Niparko JK, Quittner A, Eisenberg LS, et al. Childhood Development after Cochlear Implantation (CDaCI) study: Design and baseline characteristics. Cochlear Implants International 2007;8:92–112. [CrossRef]

- Moeller MP, Tomblin JB. An Introduction to the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss Study. Ear & Hearing 2015;36:4S-13S. [CrossRef]

- Kalandadze T, Braeken J, Brynskov C, Næss K-AB. Metaphor Comprehension in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Core Language Skills Matter. J Autism Dev Disord 2022;52:316–26. [CrossRef]

- Lidén G, Fant G. Swedish Word Material for Speech Audiometry and Articulation Tests. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1954;43:189–204. [CrossRef]

- Berninger E, Karlsson KK. Clinical study of Widex Senso on first-time hearing aid users. Scandinavian Audiology 1999;28:117–25. [CrossRef]

- Asp F, Reinfeldt S. Effects of Simulated and Profound Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss on Recognition of Speech in Competing Speech. Ear & Hearing 2020;41:411–9. [CrossRef]

- Hagerman B. Sentences for Testing Speech Intelligibility in Noise. Scandinavian Audiology 1982;11:79–87. [CrossRef]

- Asp F, Olofsson Å, Berninger E. Corneal-Reflection Eye-Tracking Technique for the Assessment of Horizontal Sound Localization Accuracy from 6 Months of Age. Ear & Hearing 2016;37:e104–18. [CrossRef]

- Denanto FM, Wales J, Tideholm B, Asp F. Differing Bilateral Benefits for Spatial Release From Masking and Sound Localization Accuracy Using Bone Conduction Devices. Ear & Hearing 2022;43:1708–20. [CrossRef]

- Peirce J, Gray JR, Simpson S, MacAskill M, Höchenberger R, Sogo H, et al. PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behav Res 2019;51:195–203. [CrossRef]

- Eklöf M, Tideholm B. The choice of stimulation strategy affects the ability to detect pure tone inter-aural time differences in children with early bilateral cochlear implantation. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2018;138:554–61. [CrossRef]

- Stadler S, Leijon A. Prediction of Speech Recognition in Cochlear Implant Users by Adapting Auditory Models to Psychophysical Data. EURASIP J Adv Signal Process 2009;2009:175243. [CrossRef]

- McGarvie LA, MacDougall HG, Halmagyi GM, Burgess AM, Weber KP, Curthoys IS. The Video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) of Semicircular Canal Function – Age-Dependent Normative Values of VOR Gain in Healthy Subjects. Front Neurol 2015;6. [CrossRef]

- Rosengren SM, Colebatch JG, Young AS, Govender S, Welgampola MS. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in practice: Methods, pitfalls and clinical applications. Clinical Neurophysiology Practice 2019;4:47–68. [CrossRef]

- Dewar R, Claus AP, Tucker K, Ware R, Johnston LM. Reproducibility of the Balance Evaluation Systems Test (BESTest) and the Mini-BESTest in school-aged children. Gait & Posture 2017;55:68–74. [CrossRef]

- Kollén L, Bjerlemo B, Fagevik Olsén M, Möller C. Static and dynamic balance and well-being after acute unilateral vestibular loss. Audiological Medicine 2008;6:265–70. [CrossRef]

- Saltin B, Grimby G. Physiological Analysis of Middle-Aged and Old Former Athletes: Comparison with Still Active Athletes of the Same Ages. Circulation 1968;38:1104–15. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Yu S, Zang X, Yu Q, Yang L. Discrimination of vestibular function based on inertial sensors. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2022;214:106554. [CrossRef]

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.M., & Dunn, D.M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (3rd ed.). American Guidance Service,; 1997.

- Dunn, L.M., & Dunn, D.M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.; 2007.

- Statistikmyndigheten. Utbildningsnivån i Sverige. 2024.

- Edwards S, Garman M, Hughes A, Letts C, Sinka I. Assessing the comprehension and production of language in young children: an account of the Reynell Developmental Language Scales III. Intl J Lang & Comm Disor 1999;34:151–71. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).