1. Introduction

Hearing loss of any degree in one ear and normal hearing in the other is referred to as unilateral hearing loss (UHL). Single Sided Deafness (SSD) is an extreme form of UHL characterized by severe to profound hearing loss in one ear and normal hearing in the better ear [

1].

Until a few years ago, it was not considered necessary to treat UHL even in the case of SSD. The development of appropriate communication skills and the absence of listening difficulties in quiet environments were the underlying reasons for not using hearing devices in UHL. However, hearing with one ear has consequences such as loss of binaural hearing.

The auditory cortex receives acoustic information from two cochleae auditory nerves and various cochlear nuclei, which are responsible to process sound intensity, timing and frequency differences. The information is then elaborated and a three-dimensional landscape of the acoustic signal is created in the cortex [

2,

3]. This complex central signal processing is the basis of binaural hearing. The advantage of binaural hearing in normal hearing individuals is the ability to separate individual voices from environmental noise and to localize the sound sources.

UHL leads to changes in the auditory cortex and new adaptations in signal processing.

Cochlear Implant (CI) is the gold standard treatment for bilateral severe to profound hearing loss. In contrast, SSD was, until recently, a contraindication for CI use. Only from the early 2000s, the CI indication criteria include SSD patients. The initial indication was related to the presence of the intractable tinnitus in the side of the deaf ear [

4]. Only in 2013 a manufacturer factory received a CE mark for CI surgery in SSD-adults [

3].

Currently, the indications for CI in SSD, initially limited to cases with concomitant severe tinnitus, have expanded to include restoration of binaural hearing as a primary goal [

5,

6,

7]. Restoration of binaural cues in UHL has been tested with different types of hearing devices (hearing aids, controlateral routing of signal -CROS or bone anchored hearing aid -BAH systems), but CI is the only available device capable of restoration these abilities in SSD [

6,

8,

9].

In fact an improvement in sound localization abilities [

10,

11,

12], better understanding in noise [

13] and a reduction in tinnitus [

11,

14,

15,

16] are reported with the use of CI in SSD compared to users of other hearing devices or unaided situation.

Other studies have shown an improvement in non-audiological parameters such as better quality of life [

17,

18] and music enjoyment [

19].

Despite the aforementioned performances, clinical practice and literature have shown that CI benefits vary across individuals with SSD [

20]. Several factors contribute to this variability. Some are related to anatomical structures, others to high-order resources, and still others to audiological characteristics.

The integrity and functionality of anatomical structures is one of the most important factors in the outcome variability. Inner ear malformations (especially cochlear nerve and cochlear opening anomalies) are involved in the aetiology of congenital SSD in more than 40% of the cases [

21,

22]. The number of surviving spiral ganglion cells and cortical plasticity of the central auditory system are also involved in CI success [

20,

23,

24].

Recent studies have focused on investigating how high-order resources; in particular, verbal abilities, working memory capacity and, more generally, listening effort resources have been reported to be associated with CI outcomes [

20,

24,

25,

26,

27].

The variability of CI performance in SSD is related to some audiological characteristics such as duration of the hearing deprivation, aetiology and onset of the hearing loss [

28,

29]. Type of surgery, type of CI array used, daily use of the CI and device fitting are also important aspects to consider in the outcomes of these patients [

30].

There are additional considerations regarding the clinical assessment of CI in SSD compared to bilateral hearing loss. In fact, traditional audiometry (pure tone audiometry or speech audiometry) does not reflect the true benefit of CI in SSD. Therefore a different audiological assessment is needed, including measurement of localization abilities, hearing in noise, tinnitus perception and quality of life.

Most of the studies reported in the literature have only evaluated the CI outcomes at a single follow-up (especially at month 12) or in a single outcome, and only a few have evaluated a significant sample of patients in the different outcome domains [

31,

32].

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the advantages of CI following one year of usage in a group of adults with SSD. Various domains were considered such as localization, speech intelligibility in both quiet and noisy environments, impact on the subjective hearing profile, and the impact on tinnitus

The secondary aim of the study was to assess the long-term stability of the benefits of CI through a comprehensive follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This is an observational, retrospective, monocentric study conducted at the outpatient clinic of the ENT Unit of the “Guglielmo da Saliceto” Hospital in Piacenza, Italy.

The study was registered with the Ethics Committee of the ‘Area Vasta’ Emilia-Nord under number 191/2020/OSS/AUSLPC (date of approval 19/06/2020).

All participants signed the informed consent form before the initial assessment.

Inclusion criteria were age over 18 years, presence of SSD with unilateral hearing loss and normal hearing on the contralateral side (see chapter on audiological assessment), use of a CI in the worst ear.

Subjects unable to give informed consent in person, unable to complete self-report questionnaires independently, or with unrealistic expectations of benefit were excluded from the study.

For the primary objective of the study, all patients underwent two evaluations: before CI surgery (T0) and at 12 months (T12), whereas for the secondary objective, i.e. the study of the CI performance over time, the assessments visits took place annually between the 6th and 60th month of follow-up (T6, T12, T24, T36 and T60).

A full audiological assessment, including the administration of questionnaires, was carried-out at each follow-up visit.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive record of the data collected at different times.

2.2. Audiological Assessment

The audiological assessment included a battery of audiological tests and was conducted in a soundproof room.

In the first evaluations (T0) pure tone audiometry with headphones, Italian matrix sentence test in three configurations and localization test were performed.

From T6 to T60 all subjects underwent speech perception score assessment in quiet, Italian matrix sentence test in three configurations and localization test. All test were performed with the CI.

A Madsen Astera audiometer (from Natus Medical Incorporated, Denmark) was used for pure-tone and speech audiometry. TDH39 supra-aural earphones were used for pure tone in T0 only.

Pure tone average (PTA) was obtained from pure tone audiometry. PTA is the average pure tone threshold at frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz frequencies for both ears.

SSD was defined as PTA less than or equal to 30 dB HL in the better ear, PTA greater than or equal to 70 dB HL in the worst ear, with an interaural threshold gap greater than or equal to 40 dB HL [

1].

Speech intelligibility in quiet was only assessed on the CI side from the T6 visit. It was not possible to perform the test at T0 (before CI surgery) in accordance with the profound hearing loss in SSD patients.

Pre-recorded lists of 20 disyllabic phonetically balanced words were used, delivered by a loudspeaker at zero degrees of azimuth in the sound field [

33]. The patient was asked to repeat three lists at a 65 dB HL. The result was the mean percentage of correctly repeated words in the three lists. A sound masking with an earplug was presented in the better ear.

Speech-in-noise ability was assessed using the Italian matrix sentence test (or Olsa test) [

34]. This test measures the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in dB at which the subject recognizes 50 % of the words presented. After a training session, three randomized lists of 20 sentences with five semantically unpredictable words are presented. The background noise is presented at 65 dB SPL, while the speech level is adaptively adjusted according to the subjects’ response to obtain the SNR. The test is administered using the S0N0 (speech and noise from the same frontal loudspeaker), S0Nci (speech frontal and noise from the CI side) and S0Nnh (speech frontal and noise from the contralateral CI side) presentation setups. The test was administered in a closed-set response format. The Italian matrix sentence test was administered without device at T0 and with CI from T6 to T60.

The Localization test was carried out in a soundproof room with 7 loudspeakers arranged in a 180° semicircle in the horizontal plane. Each loudspeaker was 30° away from the others. Each patient was seated in a fixed chair at a distance of 100 cm from the loudspeakers, which were placed at the height of the patient's head. Two different noise signals (unfiltered CCITT sound and CCITT filtered by a standard head transfer function) were randomly presented at three different intensities (65, 70 and 75 dBA) for each loudspeaker. A total of 42 stimuli were presented in each setup.

The patient was asked to indicate on a touch screen the loudspeaker from which they heard the sound. BIAS, Root Mean Square (RMS) and the Standard mean degree of error (STD) were obtained at the end of the test. BIAS show any deviation, in degree, from the correct degree of sound presentation. The RMS is the square root of the mean square of the error and STD represent the mean degree of error.

2.3. Medical Evaluation

A careful and comprehensive preoperative (T0) medical evaluation was performed by an otolaryngologist or medical audiologist from our team.

One of the aims of the examination was to code different variables such as aetiology, age at onset of the hearing loss, presence of ear malformations, duration of hearing deprivation (measured as the time between diagnosis of hearing loss and activation of the CI), and potential associated pathologies that could compromise the success of the CI.

2.4. Questionnaires

The Italian version of two questionnaires was administered by trained professionals at each visit to assess subject understanding of the task: the Speech Spatial and Qualities (SSQ) [

35] and the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) [

36].

SSQ

The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ) is a widely used self-administered questionnaire for assessing the impact of hearing loss in various real-life listening situations in adults [

35]. The questionnaire results present a ‘profile’ of notable symptoms categorized in three major scales totaling 49 items: Scale A (Speech) with 14 items, Scale B (Spatial Hearing) with 17 items, and Scale C (Other Hearing Qualities) with 18 items.

Scale A explores speech perception under various conditions; scale B focuses on direction, distance, and movement of sound sources, while scale C examines segregation of sounds, listening abilities, naturalness of sound and clarity of hearing.

Participants are asked to rate each item on a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 10. The scale is presented as a ruler. A mean value is calculated for each scale, with higher mean values indicating better subjective performance.

THI

The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) is a self-report questionnaire employed to evaluate the everyday-life impact of tinnitus. It comprises 25 items, divided into three subscales: functional (12 items), emotional (8 items), and catastrophic response (5 items).

Each item has three possible answers: “yes” (scored 4 points), “sometimes” (2 points), and “no” (0 points).

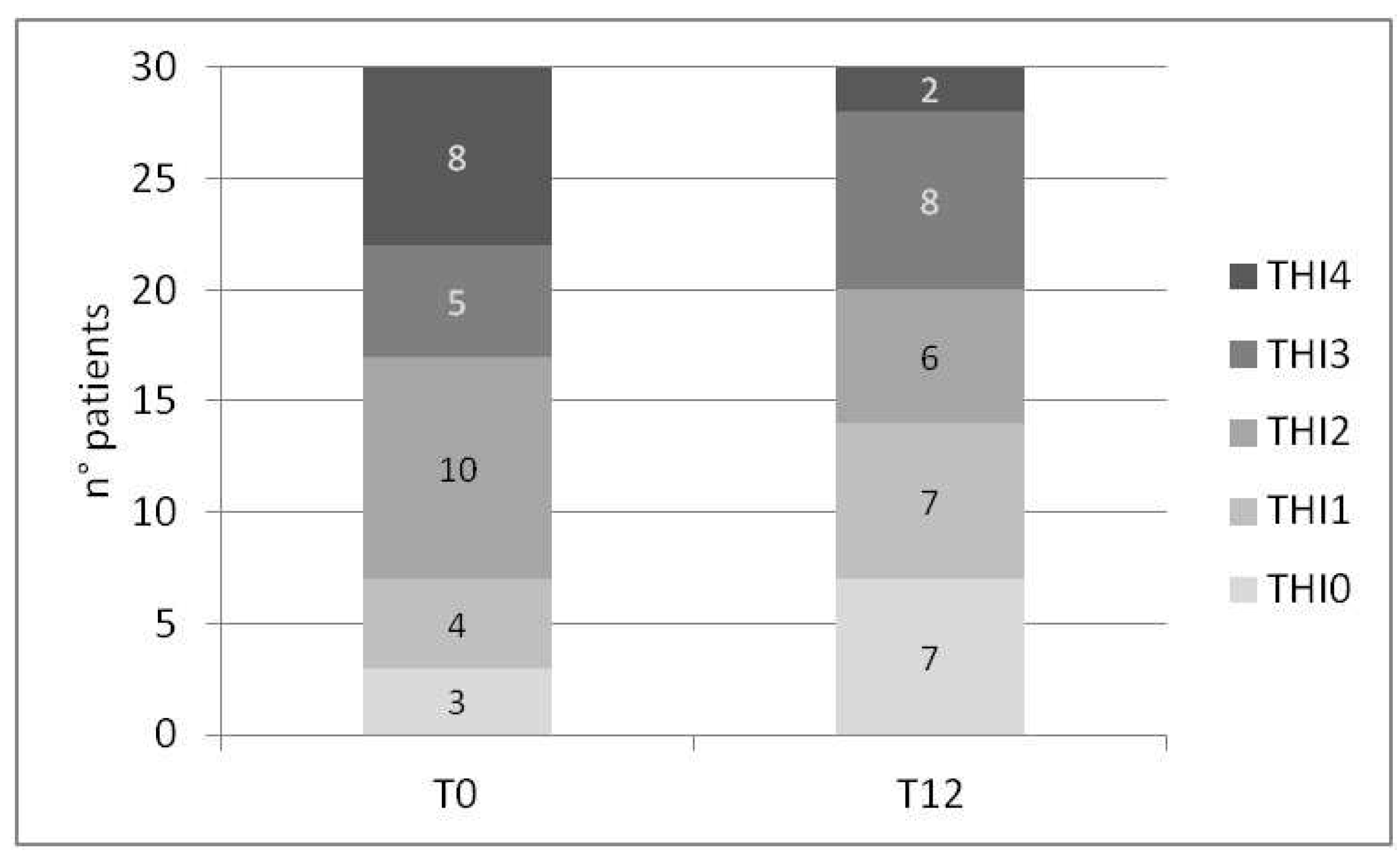

This results in a total score ranging from 0 to 100 with different levels of handicap: 0 represents no tinnitus handicap (THI0); 2 to 24 represents mild tinnitus (THI1); 26 to 48 denotes moderate tinnitus (THI2); 50 to 74 represents severe tinnitus (THI3) and 76 to 100 signifies catastrophic tinnitus (THI4) [

37].

2.5. CI Fitting

Prior to each examination, a functional check of the CI speech processor was conducted, with appropriate modifications made if necessary. Furthermore, information about the device’s daily usage time was obtained through the speech processor’s datalogging.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A two-sample paired t-test was used to compare the Italian matrix sentence test, the localization test, the SSQ and the THI questionnaires at T0 and T12. Specifically, a t-test is used if normality is not rejected at the 0.01 level (Shapiro-Wilk test), and a Wilcoxon test if normality is rejected.

To address potential confounding variables such as sex, age at cochlear implantation, and duration of hearing deprivation, we examined the differences between preoperative (T0) and post-operative state (T12) through a linear mixed model (LMM) analysis.

The trend of these outcome measures, along with aided speech perception in quiet and daily use of the CI (from T6 onwards), was assessed repeatedly at different follow-up visits. To analyze these longitudinal data, we use the same linear mixed model, which also considers the effect of potential confounders.

Statistical analysis was conducted using R software [

38]. In particular, the estimation of linear mixed models relied on the lme4 package [

39].

3. Results

The study sample consists of 57 participants with single-sided deafness and cochlear implant use, comprising of 34 females and 23 males. Their age at hearing loss diagnosis was 43.2 years (SD= 16.3), whilst the age at CI surgery was 49.0 years (SD= 13.2). On average, patients experienced 5.4 years of hearing deprivation (i.e., time elapsed between hearing loss identification and CI), with substantial variance across participants (SD = 9.0; range 6 months to 51 years).

The etiology of hearing loss in these patients was diverse. It included trauma (n 8), sudden hearing loss (n 34), meningitis (n 2), acoustic schwannoma (n 2), intralabyrinthine schwannoma (ILS) (n 2), Meniere’s disease (n 2), otosclerosis (n 2), and unknown cause (n 5). None of the patients had any radiological malformations of the middle and inner ear or other associated pathologies.

The mean PTA at T0 was 17.2 dB HL (SD 5.8; range 10-30 dB HL) in the better ear and it was 107.2 dB HL (SD 19.8; range 72.5-130 dB HL) in the worse ear.

27 patients had right-sided SSD and 30 had left-sided SSD.

Various CI brands were used, including Medel (MED-EL Elektromedizinische Geräte Gesellschaft m.b.H., Innsbruck, Austria) (28 participants, all with Flex 28 electrode), Cochlear (Cochlear LTD, Sydney, Australia) (19 participants, 13 with perimodiolar arrays and 6 with straight arrays), Advanced Bionics (Advanced Bionics, LLC, Valencia, CA, USA) (6 participants, 4 with Slim J and 2 with Mid scala arrays) and Oticon (Oticon A/S, Smørum, Denmark) (4 participants with Neuro zti EVO).

3.1. CI Outcomes after one Year of Use

In

Table 2 are reported the results of speech in noise and localization errors.

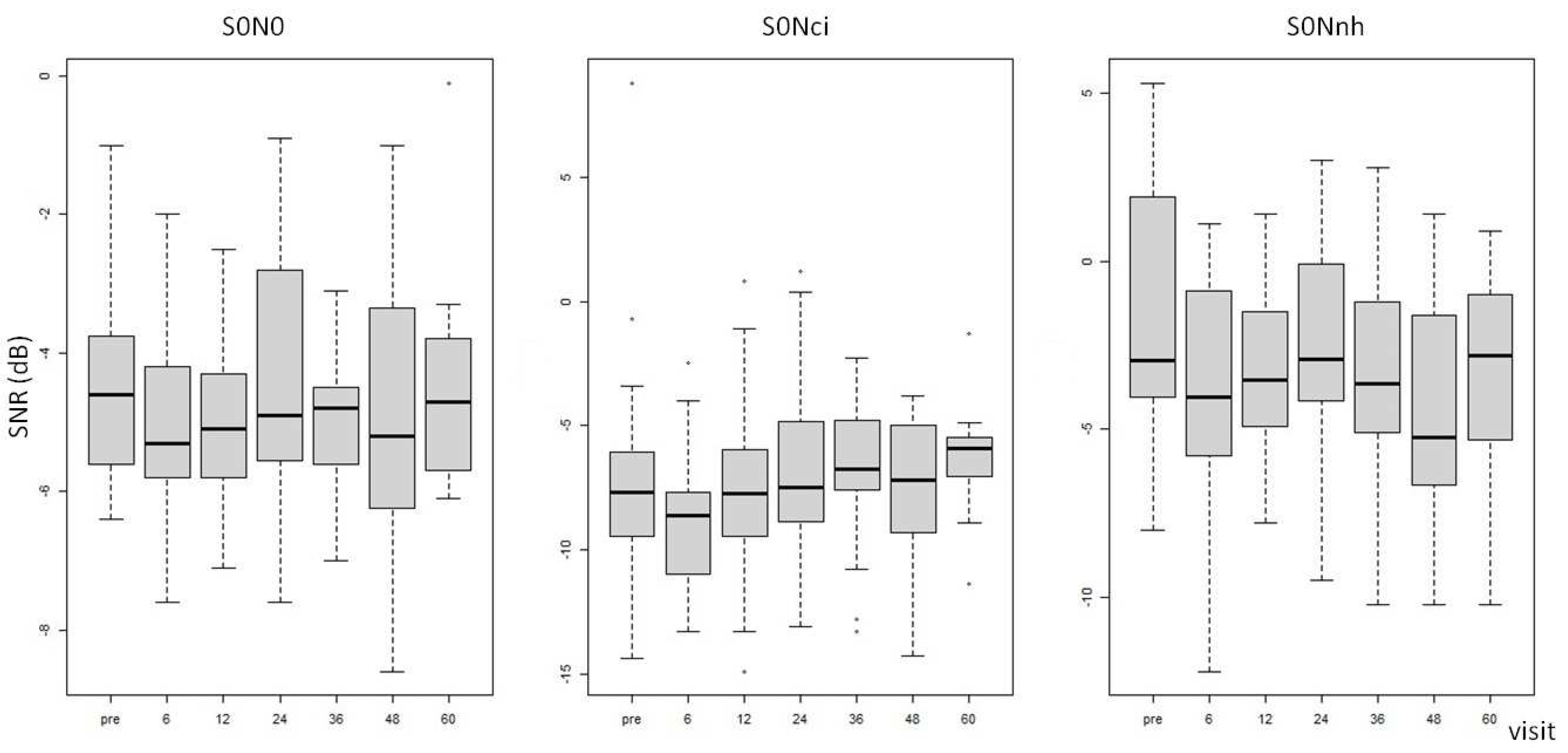

After one year of CI usage, we observed a positive change in speech-to-noise ratio (SNR) across the three different configurations explored (delta values: 0.43 dB SNR in S0N0; 0.19 dB SNR in S0Nci and 1.4 dB SNR in S0Nnh). The LMM statistical analysis which also considered potential confounders such as sex, age at CI and time of hearing deprivation, indicated statistically significant improvements in S0N0 (p-value 0.0001)..

Not all participants completed the matrix test in both T0 and T12 evaluations. In the S0N0 setup the test was carried out by 38 patients at T0 and 36 patients at T12. 31 subjects undertook the test in the S0Nic and S0Nnh configuration at T0, with 32 patients completing the test at T12.

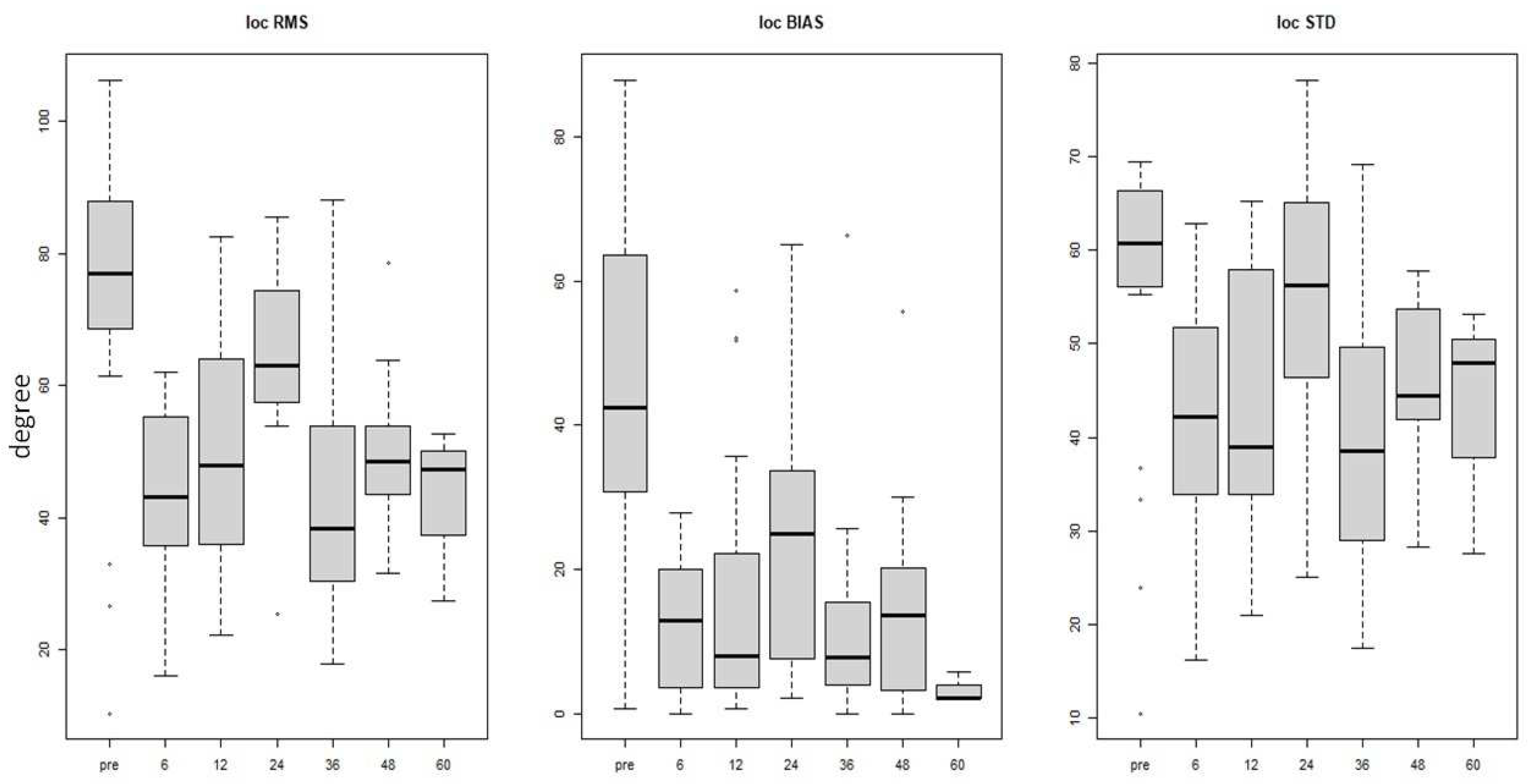

Statistically significant improvement in sound localization abilities was observed postoperatively, compared to preoperative assessment, when examining both RMS and STD parameters (p-value 0.001). The mean reduction of errors was 27.02° in RMS, 29.75° in BIAS, and 13.35° in STD values.

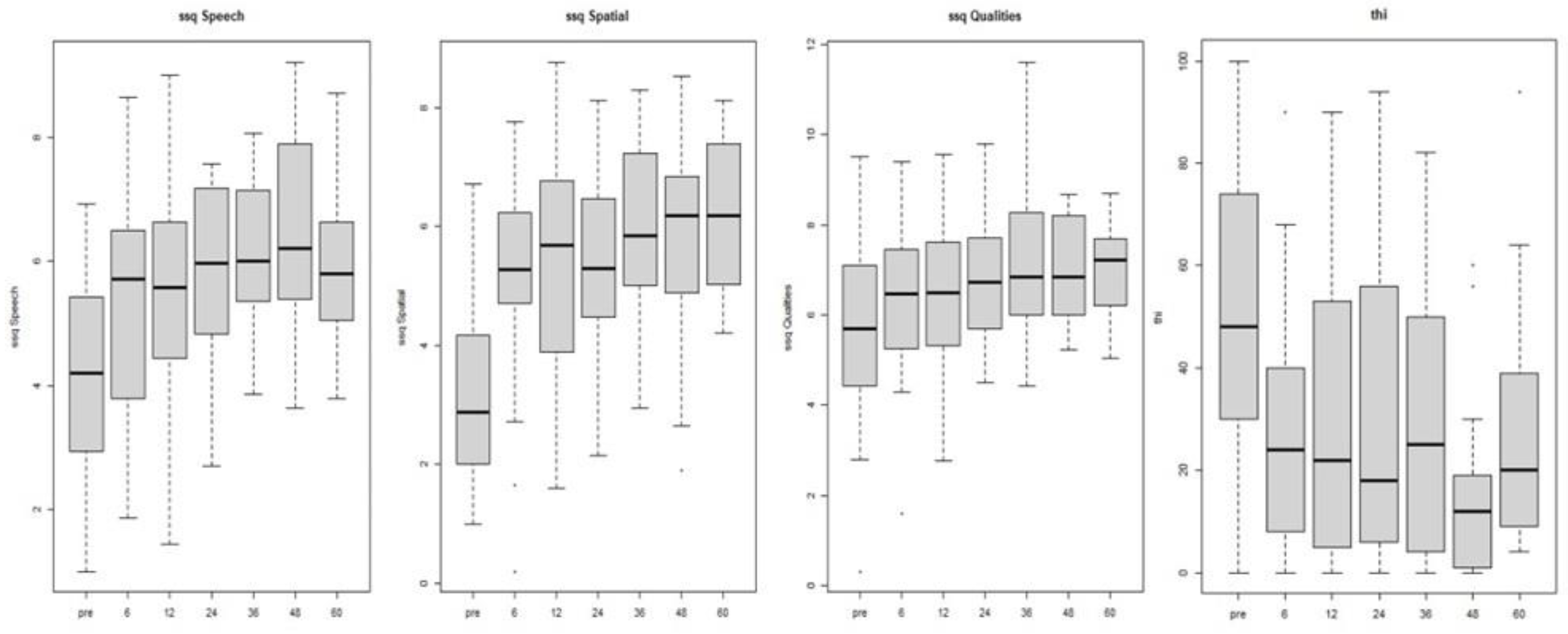

Table 3 reports the results of the questionnaires. A statistically significant mean score improvement was found in the Speech (p-value 0.001) and Spatial (p-value 0.001) subscales of the SSQ questionnaire with a mean increase of. 1.46 and 2.22 respectively. Also in the Qualities subscale we found a mean score improvement of 0.66 (p-value 0.1) points.

The study discovered a marked reduction in THI score after one year of CI use (p-value 0.001), resulting in a mean score decrease of 19.81 points. Only 30 subjects from the sample completed the THI questionnaire at both T0 and T12. Out of these, 15 demonstrated a decrease in tinnitus grading rank, while 14 maintained the same level, and only one experienced an increase in the grade, shifting from THI2 to THI3 (

Figure 1). The distribution of patients in the THI grading at visit T0 and T12 is reported in

Figure 1. Notably, there was an improvement in the number of patients with no tinnitus (THI0) and mild tinnitus (THI1), as well as a reduction in the number of patients in the THI2 grade (from 10 to 6) and THI4 grade (from 8 to 2). Although there was an increase in the number of patients with THI3 grade, 4 patients came from THI4, 3 remained stable in THI3, and only one worsened from THI2 to THI3.

3.2. CI Outcomes over Time

All 57 patients underwent preoperative evaluation (T0) and were re-evaluated six months after CI activation (T6). At T12, 51 patients were evaluated, and at T24 37 patients were evaluated. At T36, 32 patients were evaluated, followed by 25 patients at T48 and 13 patients at T60.

At each subsequent visit, the patients underwent the SNR and localization test, the THI and SSQ questionnaires, as well as the assessment of aided speech perception in quiet and the extraction of daily CI use data (from T6 to T60). The findings are shown in

Table 4.

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in both S0N0 and S0Nic configurations demonstrated no significant differences between preoperative and postoperative mean values. However, in the S0Nnh configuration, there was a postoperative SNR reduction that was sustained throughout all visits from T6 to T60 (see

Table 4 and

Figure 2). The LMM analysis, which accounted for confounders such as sex, age at CI, and hearing deprivation time, demonstrated a statistically significant effect of duration of hearing deprivation on the SNR in S0N0 and S0Nnh configurations (p-value 0.01).

The results pertaining to localization abilities (RMS, BIAS, and STD) revealed a statistically significant error reduction between pre-operative and evaluation at 6 months even after adjusting for potential confounding factors using LMM analysis (p. value 0.001). A comparable difference was observed between the pre-operative assessment and each subsequent post-operative follow-up observation (

Table 4 and

Figure 3) while the effect of the duration of hearing deprivation was not consistent.

We observed a statistically significant difference between T0 and postoperative evaluations (from T6) for both questionnaires, even after controlling for any possible confounders. In particular, there was a marked decrease in the THI score and a significant increase in the Speech and Spatial SSQ scale score (p-value 0.001), while the Qualities scale of SSQ show a more moderate effect (p-value 0.01); refer to

Table 4 and

Figure 4 for further details.

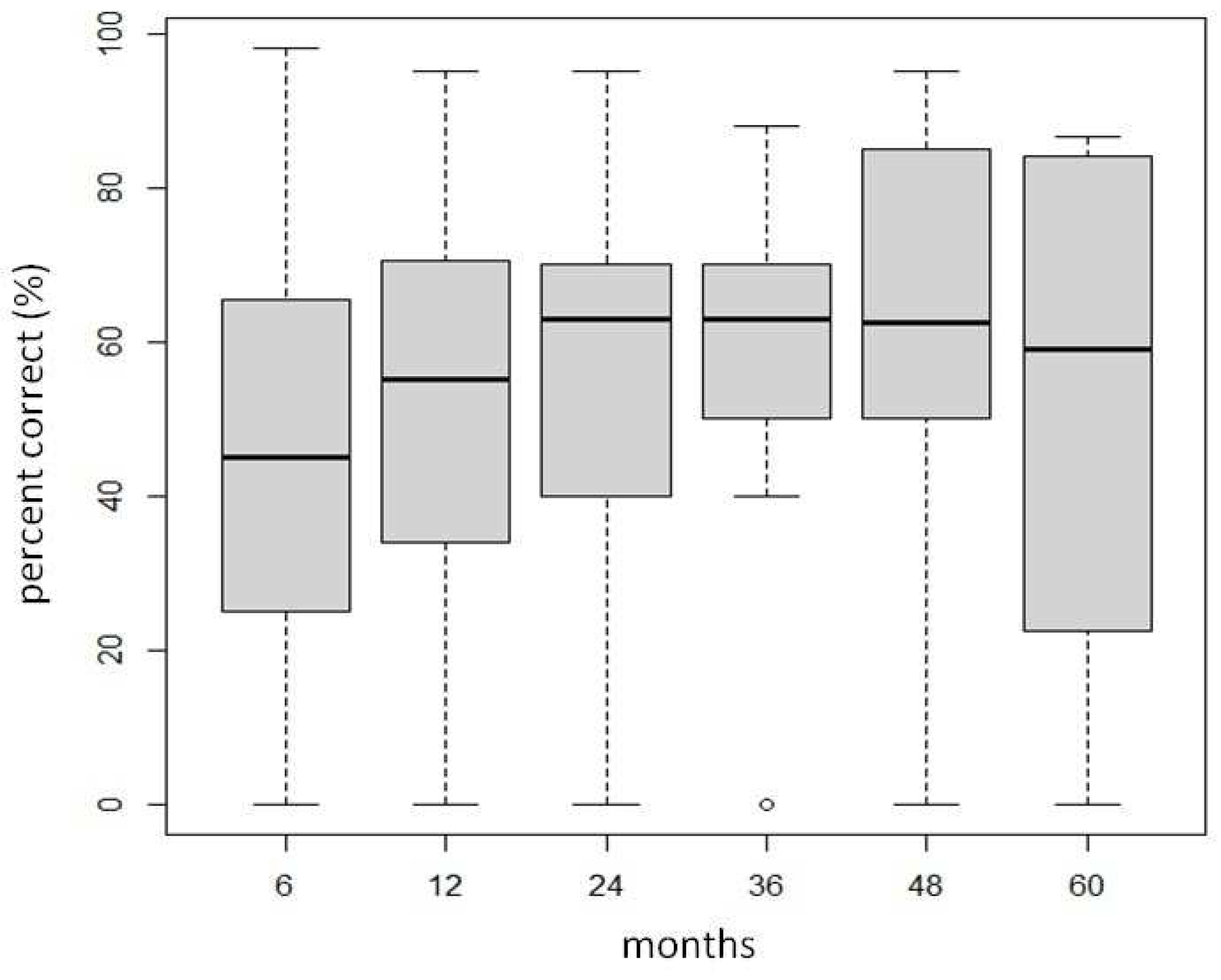

There was no significant difference observed in the aided speech perception scores in quiet over time. The scores ranged between 45.03 and 63.06 % as illustrated in

Table 4 and

Figure 5.

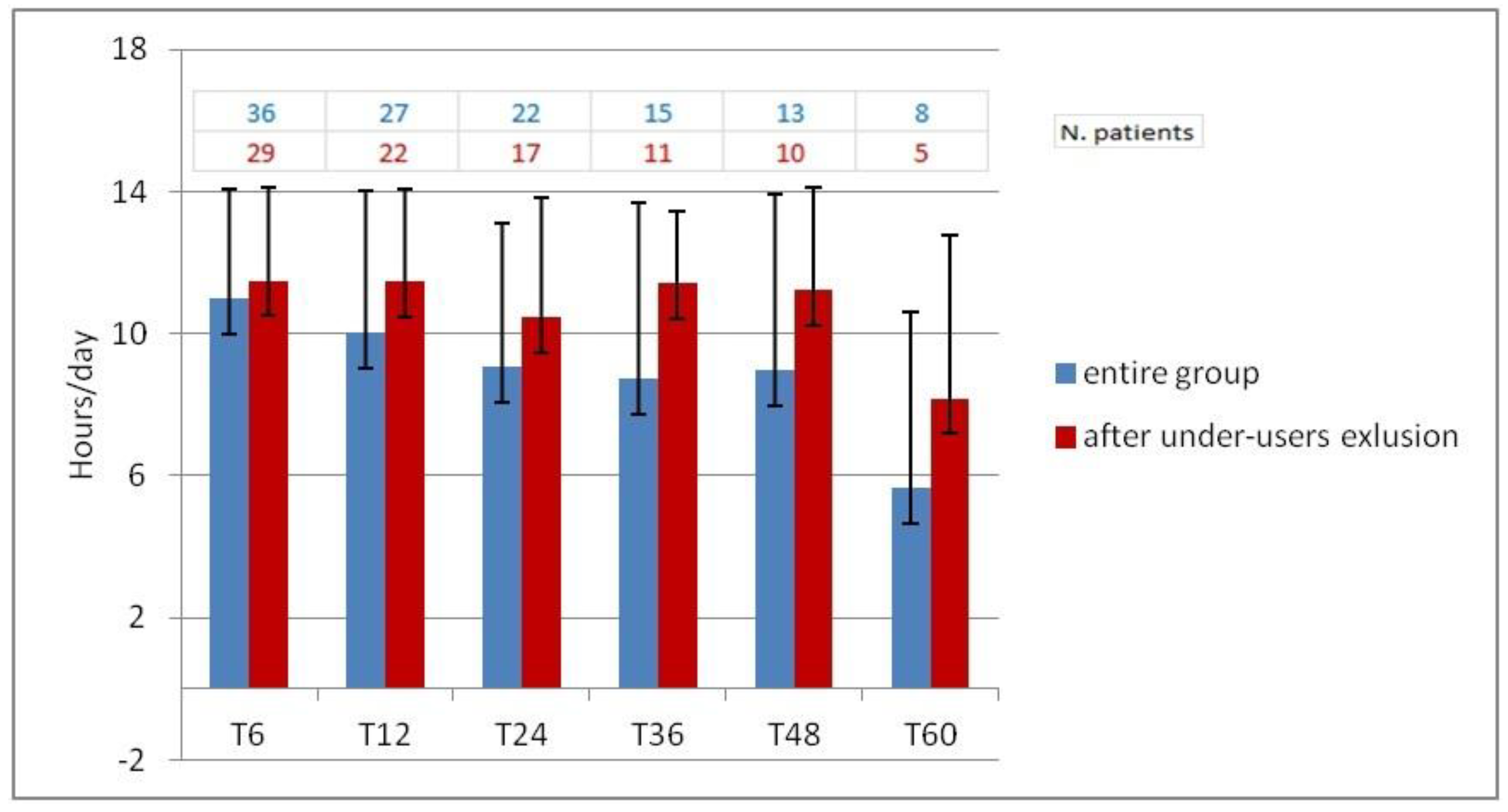

Daily use of cochlear implant could not be extracted from 15 subjects due to lack of suitable auditory processors that had datalogging technology. In the remaining sample, mean daily CI use has decreased slightly over time, from T6 (10.98 hours/day) to T48 (8.96 hours/day). A further reduction in CI use was seen at T60 (5.64 hours/day). A careful analysis of the data revealed that eight participants did not fully utilize the CI, six of whom used the device for less than five hours a day from the start, while the remaining two, after an initial full use, experienced a decline in usage after 12 months. Upon exclusion of the under-users from the sample, analysis revealed a consistent pattern of CI utilization from T6 (11.49 hours/day) to T48 (11.21 hours/day). The CI use is reduced to 8.18 hours per day in T60, but the evaluation was limited to just five subjects.

Figure 6 illustrates the average daily use in the entire sample (in blue) and after excluding under users (in red).

4. Discussion

The study aimed to verify whether using a CI in SSD leads to enhancements in various skills such as localization, speech intelligibility in noise surroundings, alleviation of tinnitus and hearing symptoms. It also examined whether these skills can be sustained over a prolonged period of CI usage.

Significant improvement was observed in intelligibility under noisy conditions with the use of the CI, in comparison to scores obtained pre-surgery without the device. The reduced signal-to-noise ratio SNR remain consistent over the period of 6 to 60 months of using a CI device without any notable changes or variations to its performances. This improvement is observed across all setup configurations, but a statistically significant difference is found only when speech originated from the front of the user and noise came from the normal hearing side (S0Nnh) or the front (S0N0).

The S0Nnh configuration presents a particularly challenging listening scenario for individuals with SSD as the noise source is located in close proximity to the hearing ear and therefore masks it. However, the use of a CI may mitigate this masking effect as the microphone of the device, in this setting, capitalizes on the advantages of head shadow and detects input with a more favorable signal-to-noise ratio. The CI reintroduces signals to restore binaural hearing, which are processed in terms of interaural time difference (ITD) and interaural level difference (ILD). As a result, patients experience improvements in effects such as summation, squelch, and head shadow. However, binaural hearing is still deficient compared to that of normal hearing subjects since the CI only partially restores hearing and the contralateral normal hearing ear remains the dominant. Our findings are consistent with the existing literature investigating speech perception in noise in patients with cochlear implants for SSD [

9,

31,

32]. Specifically, Tavora-Viera et al. evaluated speech intelligibility in noise using the same three setup configurations as our study and found that performance improved in the S0N0 and S0Nnh configurations [

32].

Cochlear implantation for SSD patients is associated with improvements in localization abilities. Our study shows a significant improvement between pre- and post-CI surgery, with an approximate BIAS improvement of 30°. Additionally, significant improvement was observed in all three parameters (RMS, BIAS and STD) evaluated between TO and all subsequent follow-up visits. Localization restoration is only evident with cochlear implants and not with CROS hearing aids or osseointegrated implants [

40]. Thompson et al. show significant improvements in sound source localization from the first weeks of CI use, with further improvement over time (up to 5 years of CI use) [

41]. Additionally, Sullivan et al. reported an enhancement in localization abilities through evaluating the decrease in the RMS parameter. These authors employed a localization setup similar to ours, albeit their sample had superior skill abilities prior to the CI intervention (mean RMS approximately 40° compared to 70° in our sample) [

31]. It is pertinent to note that the abilities after the CI usage improve with the device usage time, just like our findings. There were no differences in speech intelligibility in quiet at any of the follow-up sessions. Due to the profound hearing loss in the worst ear, it was not possible to perform the pre-CI surgery test. It is challenging to perform this test, as it conceals the unaffected ear, and even using high-level maskers through earplugs may generate a shadow response from that side. Consequently, it was not possible to quantify exactly the actual benefit of CI on speech perception in quiet.

In accordance with existing literature [

11,

14,

15,

16,

42,

43], our data demonstrate a noteworthy reduction of the THI score from pre- to post-CI surgery. Specifically, we found a THI score reduction in half of the participants, whilst 46,7% of subjects maintained stable THI score; only one participant had a worsening of the THI score leading to a grade change from T2 to T3. This data demonstrate an overall improvement in tinnitus severity when using a CI. The improvement remains consistent over time at various follow-up visits Our data align with that of Mertens et al. [

11] who demonstrated that cochlear implant in patients with SSD lead to a reduction in tinnitus for up to three months of CI use. Furthermore, the reduction remains sustained over a period of up to ten years of follow-up [

11].

The SSQ questionnaire demonstrates improvement of scores in all three subscales Specifically, there was a statistically significant improvement in the speech and spatial subscales between pre- and post-CI surgery. Additionally, the quality subscale exhibited an improving trend ( of 0.66 points) between T0 and T12 evaluation.

These improvements remained stable in all three subscales for up to five years following CI use. The SSQ questionnaire is commonly used to assess subjective hearing ability in a variety of everyday situations. Since the items in this questionnaire explore various listening scenarios including noisy environments, sound localization, and other real-world listening context, it has already been used to highlight the advantages of CI in individuals with SSD [

32,

43]. According to our results, Tavora-Viera et al. [

32] demonstrate a significant improvement in the global SSQ score, measuring it prior to and after long-term CI use (between 4 and 10 years of CI use). On the contrary, Fan et al. did not observe significant changes in SSQ scores in SSD patients when using CI [

43]. This could be due to the specific population included in the study and the duration of the follow-up period. In fact, only seven patient affected by SSD and tinnitus were evaluated, and they were only evaluated for a short follow up period of 6 months after implantation.

Although we observed a significant and sustained improvement in most of the explored abilities and symptoms (localization, speech in noise, tinnitus and subjective listening skills) we observed a decline in the CI utilization over time. This trend may be attributed to the small number of subjects with lengthy follow-up (only 8 subjects in T60) and to under-users (CI usage of less than 5 hours/day), which represent 14% of our sample. Few studies in literature have assessed the incidence of non-use or limited use of CI [

44]. Tavora-Vieira et al. found that 4.4% of their CI recipients elected to discontinue device use [

44]. The higher percentage in our study can be attributed to the criterion for under-user, which includes individuals with an average CI usage of less than 5 hours per day. On the other hand, the other study only considered elective non-use (subjects who chose to stop using their device).

One limitation of our study is the varying number of tests conducted during both pre- and post-surgery visits. The reason for this is that certain tools such as the Italian Matrix and localization test were unavailable at the time of subject recruitment. Additionally, a shared clinical assessment of adult CI candidates and recipients with SSD was only recently coded [

45]. Data pertaining to this cohort will be further reviewed in accordance with the latest recommendations.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study shows that the use of CI in subjects with SSD generally results in initial benefits during the first few months of use, with no significant changes observed during follow-up visits.

CI represents an effective method for improving speech recognition in noisy environments, restoring sound localization abilities, reducing tinnitus and improve subjective listening skills.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C; Methodology, E.P and A.L.; Validation, D.S., A.L. and E.P.; Formal Analysis, S.G and E.P.; Investigation, S.G. and D.C.; Resources, E.P. and S.G.; Data Curation, E.P. and A.L.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, S.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, D.C.; Visualization, D.S., E.P. and A.L.; Supervision, D.C.; Project Administration, S.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Area Vasta’ Emilia-Nord (approval number 191/2020/OSS/AUSLPC; date of approval 19/06/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they are sensitive health data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Enrico Fabrizi for his contribution to the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Van de Heyning, P.; Tavora-Vieira, D.; Mertens, G.; Van Rompaey, V.; Rajan, G.P.; Müller, J.; Hempel, J.M.; Leander, D.; Polterauer, D.; Marx, M.; Usami, S.I.; Kitoh, R.; Miyagawa, M.; Moteki, H.; Smilsky, K.; Baumgartner, W.D.; Keintzel, T.G.; Sprinzl, G.M.; Wolf-Magele, A.; Arndt, S.; Wesarg, T.; Zirn, S.; Baumann, U.; Weissgerber, T.; Rader, T.; Hagen, R.; Kurz, A.; Rak, K.; Stokroos, R.; George, E.; Polo, R.; Del Mar Medina, M.; Henkin, Y.; Hilly, O.; Ulanovski, D.; Rajeswaran, R.; Kameswaran, M.; Di Gregorio, M.F.; Zernotti, M.E. Towards a unified testing framework for single-sided deafness studies: a consensus paper. Audiol Neurootol 2016, 21, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avan, P.; Giraudet, F.; Buki, B. Importance of binaural hearing. Audiol Neurootol 2015, 20 (Suppl 1), 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasingh, A.; Hochmair, I. CI in single-sided deafness. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 2021; 141, Suppl. 1, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Heyning, P.; Vermiere, K.; Diebl, M.; Nopp, P.; Anderson, I.; De Ridder, D. Incapacitating unilateral tinnitus in single-sided deafness treated by cochlear implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2008, 117, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeire, K.; Van de Heyning, P. Binaural hearing after cochlear implantation in subjects with unilateral sensorineural deafness and tinnitus. Audiol Neurootol 2009, 14, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.; Aschendorff, A.; Laszig, R.; Beck, R.; Schild, C.; Kroeger, S.; Ihorst, G.; Wesarg, T. Comparison of pseudobinaural hearing to real binaural hearing rehabilitation after cochlear implantation in patients with unilateral deafness and tinnitus. Otol Neurotol 2011, 32, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechner, A.; Brendel, M.; Lesinski-Schiedat, A.; Wenzel, G.; Frohne-Buechner, C.; Jaeger, B.; Lenarz, T. Cochlear implantation in unilateral deaf subjects associated with ipsilateral tinnitus. Otol Neurotol 2010, 31, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.; Laszig, R.; Aschendorff, A.; Beck, R.; Schild, C.; Hassepass, F.; Ihorst, G.; Kroeger, S.; Kirchem, P.; Wesarg, P. Einseitige Taubheit und Cochlear-Implant- Versorgung. HNO 2011, 59, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Steizig, Y. The Koblenz experience in treating single sided deafness with cochlear implants. Audiol Neurotol 2011, 16 (suppl 1), 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, S.M.; Robinson, A.D.; Diaz, R.C. Cochlear implantation in single-sided deafness for enhancement of sound localization and speech perception. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012, 20, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, G.; De Bodt, M.; Van de Heyning, P. Cochlea implantation as a long-term treatment for ipsilateral incapacitating tinnitus in subjects with unilateral hearing loss up to 10 years. Hear Res 2016, 331, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlastarakos, P.V.; Nazos, K.; Tavoulari, E.F.; Nikolopoulos, T.P. Cochlear implantation for single sided deafness: the outcomes. An evidence based approach. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013, 271, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Stelzig, Y.; Nopp, P.; Schleich, P. Audiological results with cochlear implants for single-sided deafness. HNO 2011, 59, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, R.A.G.J.; George, E.L.J.; Stokroos, R.J.; Vermeire, K. Review: cochlear implants as a treatment of tinnitus in single-sided deafness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012, 20, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punte, A.K.; Vermeire, K.; Hofkens, A.; De Bodt, M.; De Ridder, D.; Van de Heyning, P. Cochlear implantation as a durable tinnitus treatment in single-sided deafness. Cochlear Implants Int 2011, 12, S26–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.J.; Punte, A.K.; De Ridder, D.; Vanneste, S.; Van de Heyning, P. Neural substrates predicting improvement of tinnitus after cochlear implantation in patients with single-sided deafness. Hear Res 2013, 299, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härkönen, K.; Kivekäs, I.; Rautiainen, M.; Kotti, V.; Sivonen, V.; Vasama, J.P. Single-sided deafness: the effect of cochlear implantation on quality of life, quality of hearing, and working performance. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2015, 77, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muigg, F.; Bliem, H.R.; Kühn, H.; Seebacher, J.; Holzner, B.; Weichbold, V.W. Cochlear implantation in adults with single-sided deafness: generic and disease-specific long-term quality of life. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020, 277, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberger, D.M.; Vermeire, K.; Stupak, N.; Lavender, A.; Neukam, J.; Van de Heyning, P.; Svirsky, M.A. Music is more enjoyable with two ears, even if one of them receives a degraded signal provided by a cochlear implant. Ear Hear 2020, 41, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, M.; Sandmann, P.; Bönitz, H.; Kral, A.; Büchner, A. Consequences of Stimulus Type on Higher-Order Processing in Single-Sided Deaf Cochlear Implant Users. Audiol Neurotol 2016, 21, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, E.; Bajin, M.D.; Jafarov, S.; Yıldırım, M.Ö.; Çınar, B.Ç.; Sennaroğlu, G.; Sennaroğlu, L. Inner-ear malformations as a cause of single-sided deafness. J Laryngol Otol 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollaers, K.; Thompson, A.; Kuthubutheen, J. Cochlear nerve anomalies in paediatric single-sided deafness - prevalence and implications for cochlear implantation strategies. J Laryngol Otol 2020, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadol, J.; Young, Y.; Glynn, R. Survival of spiral ganglion cells in profound sensorineural hearing loss: implications for cochlear implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1989, 98, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, A.; Kronenberger, W.G.; Pisoni, D.B.; O’Donoghue, G.M. Neurocognitive factors in sensory restoration of early deafness: a connectome model. Lancet Neurol 2016, 15, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finke, M.; Sandmann, P.; Kopp, B.; Lenarz, T.; Buchner, A. Auditory distraction transmitted by a cochlear implant alters allocation of attentional resources. Audit Cogn Neurosci 2015, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, E.N.; Dillon, M.T.; Park, L.M.; Rooth, M.A.; Richter, M.E.; Thompson, N.J.; O'Connell, B.P.; Pillsbury, H.C.; Brown, K.D. Influence of cochlear implant use on perceived listening effort in adult and pediatric cases of unilateral and asymmetric hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 2021, 42, e1234–e1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronnberg, J.; Rudner, M.; Foo, C.; Lunner, T. Cognition counts: a working memory system for Ease of Language Understanding (ELU). Int J Audiol 2008, 47, S99–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.M.; Svirsky, M.A. Duration of unilateral auditory deprivation is associated with reduced speech perception after cochlear implantation: A single-sided deafness study. Cochlear Implants Int 2019, 20, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist, N.R.; Holder, J.T.; Patro, A.; Cass, N.D.; Tawfik, K.O.; O'Malley, M.R.; Bennett, M.L.; Haynes, D.S.; Gifford, R.H.; Perkins, E.L. Cochlear Implants for Single-Sided Deafness: Quality of Life, Daily Usage, and Duration of Deafness. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 2362–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, L.R.; Gagnon, E.B.; Dillon, M.T. Factors that influence outcomes and device use for pediatric cochlear implant recipients with unilateral hearing loss. Front Hum Neurosci 2023, 12, 1141065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.B.; Al-Qurayshi, Z.; Zhu, V.; Liu, A.; Dunn, C.; Gantz, B.J.; Hansen, M.R. Long-term audiologic outcomes after cochlear implantation for single-sided deafness. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 1805–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Távora-Vieira, D.; Rajan, G.P.; Van de Heyning, P.; Mertens, G. Evaluating the Long-Term Hearing Outcomes of Cochlear Implant Users With Single-Sided Deafness. Otol Neurotol 2019, 40, e575–e580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, M.; Cutugno, G.; Maturi, P.; Prosser, S.; Leoni, F.A.; Arslan, E. Bisyllabic words for speech audiometry; a new Italian material. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 1993, 13, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puglisi, G.E.; Warzybok, A.; Hochmuth, S.; Visentin, C.; Astolfi, A.; Prodi, N.; Kollmeier, B. An Italian matrix sentence test for the evaluation of speech intelligibility in noise. Int J Audiol 2015, 54 (Suppl. 2), 2),44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse, S.; Noble, W. The speech, spatial and qualities of hearing scale (SSQ). Int J Audiol 2004, 43, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passi, S.; Ralli, G.; Capparelli, E.; Mammone, A.; Scacciatelli, D.; Cianfrone, G. The THI questionnaire: psychometric data for reliability and validity of the Italian version. Int Tinnitus J 2008, 14, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- McCombe, A.; Baguley, D.; Coles, R.; McKenna, L.; McKinney, C.; Windle-Taylor, P. ; British Association of Otolaryngologists, Head and Neck Surgeons. Guidelines for the grading of tinnitus severity: the results of a working group commissioned by the British Association of Otolaryngologists, head and neck surgeons, 1999. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2001, 26, 388–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Statistical Softw 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.R.; Gantz, B.J.; Dunn, C. Outcomes after cochlear implantation for patients with single-sided deafness, including those with recalcitrant Meniere’s disease. Otol Neurotol 2013, 34, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.J.; Dillon, M.T.; Buss, E.; Rooth, M.A.; Richter, M.E.; Pillsbury, H.C.; Brown, K.D. Long-Term Improvement in Localization for Cochlear Implant Users with Single-Sided Deafness. Laryngoscope 2022, 132, 2453–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.A.; Lee, J.A.; Nguyen, S.A.; McRackan, T.R.; Meyer, T.A.; Lambert, P.R. Cochlear Implantation for Treatment of Tinnitus in Single-sided Deafness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol 2020, 41, e1004–e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, C.; Chen, M.; Mao, J.; Li, S. The impact of cochlear implantation on quality of life and psychological status in single-sided deafness or asymmetric hearing loss with tinnitus and influencing factors of implantation intention: a preliminary study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Távora-Vieira, D.; Acharya, A.; Rajan, G.P. What can we learn from adult cochlear implant recipients with single-sided deafness who became elective non-users? Cochlear Implants Int 2020, 21, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, M.T.; Kocharyan, A.; Daher, G.S.; Carlson, M.L.; Shapiro, W.H.; Snapp, H.A.; Firszt, J.B. American Cochlear Implant Alliance Task Force Guidelines for Clinical Assessment and Management of Adult Cochlear Implantation for Single-Sided Deafness. Ear Hear 2022, 43, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).