Introduction

The gaming industry, as a key driver for the introduction of extended reality (XR), played a central role in the distribution of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) glasses. While VR sets the user into a complete digital visual environment, AR provides a visual overlay of real-world perception. Visual capturing and overlay by AR and VR are assumed to revolutionize how we interact with the digital and even the real world (Xiong et al., 2021).

Although, so far, mostly not in regular daily use, various applications, even in otolaryngology, have been tested and described. In a cadaveric study, Chan et al. used AR with TORS to improve critical structure identification. Other groups tried to use AR to enhance parotid surgeries relevant to structure identification (Scherl et al., 2021). Further, it was used for free flap harvesting and reconstructive planning (Necker et al., 2023).

Otology can be assumed to be a primary driver in digital visual applications. Per definition, the ROBOSCOPE system (BHS, Innsbruck, Austria) is a VR system allowing high-precision surgery like cochlear implantation, free flap anastomosis, and neurosurgical procedures (Holland et al., 2024; Piloni et al., 2021). Even here, an augmentation of electrophysiological information is helpful (Eichler et al., 2024) and implemented into the surgical procedure.

AR-guided surgery has been performed to implant bone conductive devices to improve accuracy (Lui et al., 2023). An AR system guiding through the Da Vinci Si System was used to perform cadaveric mastoidectomies, posterior tympanotomies, and cochleostomies (Liu et al., 2014).

However, AR has much more to offer than just an overlay of additional, primarily anatomic visual information. Cross-modal sensory interaction is well known and applied in different clinical fields, e.g., tinnitus and vestibular rehabilitation. The principle of the Lenire system is a tongue stimulator to improve tinnitus burden (Boedts et al., 2024). This concept is based on the approach described by Danilov et al. (2007), where a device called the “BrainPort” stimulates the tongue to enhance balance control. In this context, the same principle is applied even when head movements deviate from an acceptable range, helping to improve balance.

A mixed-case example is the successful use of the Wii board for vestibular rehabilitation, which used proprioceptive training and visual input (Lang et al., 2010).

VR is used to rehabilitate cochlea-implanted children to improve their spatial hearing skills by adding visual information in gamified content (Parmar et al., 2024). Here, visual and auditory information is shared as an example of successful cross-modal sensory interaction.

The use of transcripts has been widely known for decades as a support for hard-of-hearing television. Newly software-based automated transcripts changed the working field of simultaneous translators and led to the development of software and microphone systems, allowing the differentiation of different speakers (e.g., SPEAKSEER).

The recently developed AR glasses allow the integration of transcriptive software and their visual presentation during a conversation. Related to the design of the glasses, they have an integrative character and allow specific hard of hearing or deaf patients to see for the first time a communicative integration.

This study aims to compare different AR systems as a communicative device, raise pros and cons, and discuss possible indication groups.

Material and Methods

We compared four different systems of AR glasses with the ability for an automated transcript (G1, Even Realities, Shenzen, China; Myvu, Meizu, Guangdong, China; Air, XReal, Haidan, China; Moverio BT 40, Epson, Suwa, Japan) in terms of design, connectivity, software, security design and microphone design. The glasses itself are shown in

Figure 1a–d. The systems automated transcription capabilities were evaluated in a sound booth using the Freiburger monosyllabic (at 65 dB and 80 dB), numbers test (at 65 dB and 80 dB), and Oldenburger sentence test (OLSA) in an open set format, both in quiet and in noise conditions.

Results

As a communicative benchmark used in the regular clinical setting, we performed monosyllabic, understanding numbers, and OLSA testing. This testing allows a comparison with other supportive systems for patients with hearing loss. A primary difference is that for glasses, speech capturing is stable, when using glasses, while speech understanding in patients is affected by different variables influencing the auditory pathway.

Patients’ speech understanding with the different systems is shown in

Table 2.

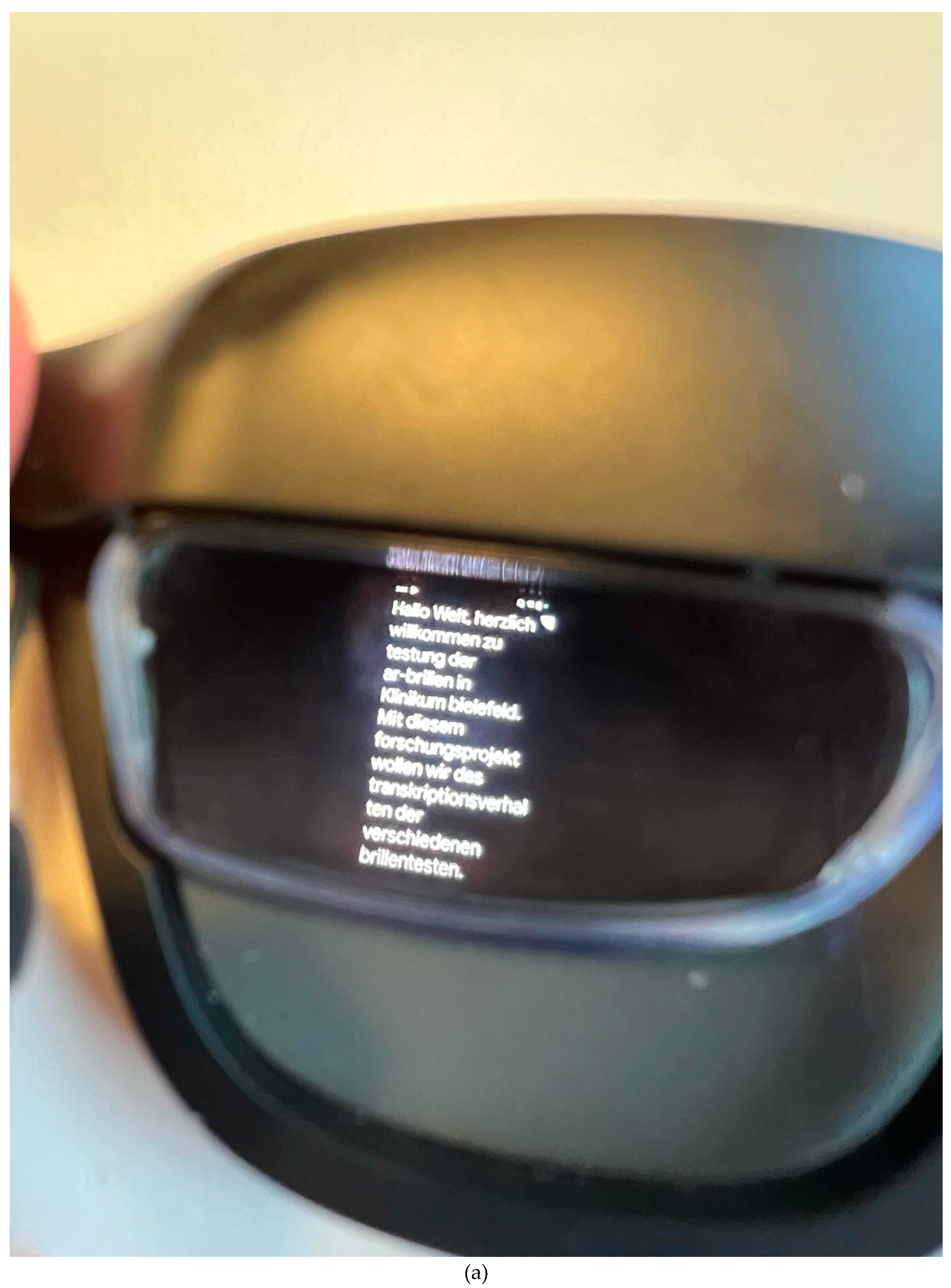

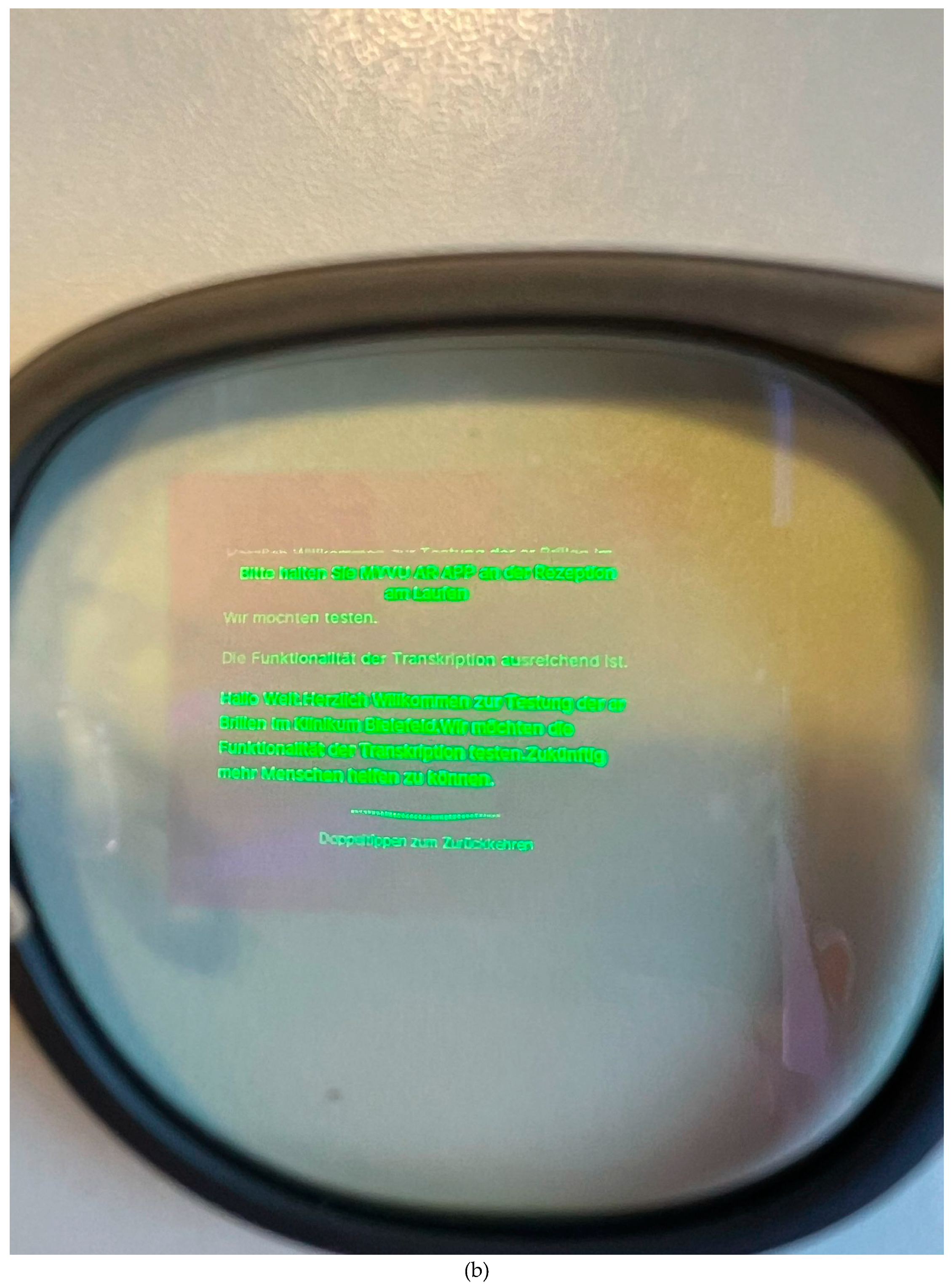

Besides the pure communicative support, further aspects are essential for assessing the integrative value of the different systems. Regarding the glass design, the AIR and Moverio are based on a screen principle distinct from the G1 and MYVU glasses. The first design is based on prism glasses, which allow the color projection of whole browser screens. In contrast, the latter photodiode projection transfers information in letters and numbers in a singular color (green) (

Figure 2a,b). The G1 system allows an adaptation of the glasses to the individual visual deficit by changing the glass. The AIR system looks like sunglasses, which cover the prism glass. Limited system control directly on the glasses is possible for the AIR, G1, and MYVU, either by touching the frame`s sides using the accelerometer through head movements.

Further steering of the systems can be performed by a controller (connected by USB-C) for the AIR and the Moverio system or by Bluetooth and a mobile phone for the G1 and the MYVU system. A direct microphone- integration into the glasses is fitted into the G1, AIR, and MYVU systems. The Moverio has its microphone on the controller. Offline functionality is system-dependent: AIR and Moverio support offline communication by projecting content directly from smartphone or controller screens, while the G1 and MYVU lack this capability entirely.

Implementing Laviere microphones to improve individualization and directionality is possible for the AIR and Moverio systems.

While the G1 and the MYVU system-based software allows, besides the speech-to-text transcript, a translation into and from different languages, the package contains an AI communicator (ChatGPT, Perplexity for G1; unclear for MYVU), a prompter tool, and a navigation tool. The AIR and Moverio systems have access to the Google apps ecosystem. The G1 system can be used by apps based on AugmentOS (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of different AR systems.

Table 1.

Comparison of different AR systems.

| System |

Epson, Moverio 40 |

Xreal, AIR |

Meizo, MYVU IMIKI |

Even Realities, G1 |

| Shape/ inclusion |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

| Display |

prism |

prism |

photodiode |

photodiode |

| Glasses |

fixed |

fixed |

fixed |

adjustable |

| Software |

Automated transcript, google 6.6.589729414 |

Automated transcript, google 6.6.589729414 |

MYVU, 2.32.141 |

1.5 and access to Augment OS |

| Microphone |

controller |

glass lateral or controller |

glass lateral |

glass frontal |

| Connection |

USB C |

USB C |

bluetooth |

bluetooth |

| Storage |

controller, EPSON |

controller, XREAL X 4000 |

mobile |

mobile |

| Communication |

offline |

offline |

online |

online |

Table 2.

Best speech understanding of different AR systems.

Table 2.

Best speech understanding of different AR systems.

| System |

Epson, Moverio 40 |

XREAL, AIR |

Meizo, MYVU IMIKI |

Even Realities, G1 |

| numbers 80 dB |

100% |

100% |

95% |

100% |

| 65 dB |

100% |

100% |

70% |

90% |

|

monosyllabic80 dB

|

75% |

65% |

55% |

80% |

| 65 dB |

45% |

25% |

20% |

45% |

| OLSA in quiet |

97% |

77% |

100% |

99% |

| OLSA in noise |

+2.3 dB |

+1.7 dB |

+ 2 dB |

+ 3.5 dB |

Discussion

AR and AI bear enormous potential in many medical fields. In the otolaryngological field, AI-based transcription software has replaced sign language interpreters.

AR glass systems in the gaming industry or industrial use are almost unrelated to communicative content. The combination of transcriptive software and AR glasses has enormous potential as an additional tool for rehabilitating deaf people. It allows specific groups to integrate into speech-to-text-based communication for the first time. This means, e.g., that people dependent on pure sign language-based communication could have access to speech-based communication. A key advantage is the glass’s non-surgical character of informational transmission in cases of severe hearing loss and deafness. Surgery is a limiting point in patients with severe disabilities and comorbidities.

The detailed comparison of the technical abilities of the different systems shows the deficits, the pros and cons, and even the details where a substantial improvement could help communication significantly or where the difference between the systems is a matter of taste, which one is preferred. A frontal microphone seems to show better speech capturing (G1). Although this has no effect on hearing in noise.

AIR and Moverio are, related to their design, less inclusive than MYVU and G1. On- or offline communication is of significant importance in terms of communicative security.

Additionally, it must be mentioned that a cross modal sensory solution is not comparable with a sensory supporting solution (hearing aids, cochlear implant). We see AR glasses as a solution for patient groups without any other options for inclusion into speech-text-based communication or as a supportive tool to improve speech-text-based communication during rehabilitation (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Medical indication for AR systems.

Table 3.

Medical indication for AR systems.

| Medical indication criteria: |

|

A: Direct sensory support (hearing aids, cochlea implant) is not possible |

| (e.g., pre lingual deafness and reading ability (sign-language dependence), bilateral nerve deficiency, hearing loss and chronic otitis externa without possibility to perform an active middle ear implant surgery) |

|

B: Support for the rehabilitation with hearing aids and CI |

| (e.g., low CI outcome, low HA outcome, temporary use during CI rehabilitation) |

In contrast to a sensory supporting system like hearing aids and cochlear implants, which offer passive support for the patient, the AR system requires active cognitive performance of deaf people. This performance is influenced by the ability to read (e.g., alphabetic, age dependence, communicative level, attention, fatigue, …).

The tested systems showed good speech-capturing abilities in quiet and for numbers. OLSA in quiet and tested numbers performance was up to 100%. Speech capturing in noise (OLSA in noise) or difficult situations (monosyllabic) was done for all systems and shows the current limitations of the systems.

The outcome of the speech understanding of the systems depends mainly on microphone ability and software speech recognition quality. It can be assumed that a further AI integration of speech-to-noise separation will improve speech capturing significantly, similar to what is currently observable in the hearing aids field. The possible connection of a Laviere microphone might be important in further improving transcriptive quality in specific interindividual situations in noise.

The glass design plays a significant role in including deaf persons. Here, regular looks like standard glasses, weight, and adjustability to visual impairment are important. On the other hand, connecting to a controller/ mobile phone limits the mobility of wearing the glasses.

The underlying software, even under the aspect of upgradeability and integration of further applications and easy adjustments, is a further important factor. The open-source nature of the software, including Android XR and the Augment OS, presents a potential path for future developments in this direction. This would follow the understanding of seeing AR glasses as a platform for further applications. Limits of the transcripts persist with respect to expressing accentuations to deliver emotions, irony, or cynicism.

A significant drawback of AR systems is the dependence on a second device, such as a mobile phone or a controller, for the transcript. A second device can be lost, and battery lifetime is an unpretty limitation for communication. Another important aspect is the third-party communication, when a mobile online connection or WIFI dependence in two of the four glass systems. This fact raises concerns about the security of interpersonal communication.

Limitations of the systems persist clearly in catching up with directionality. Here, further developments in software and microphone techniques are needed to integrate these crucial points for improved speech capturing.

Conclusions

AR glasses provide a new treatment option for specific patients with hearing loss in selected indication groups. Current systems have their pros and cons and should be chosen on an individual base.

Author Contributions

H.R.: conception, draft, final approval; I.E., measurements, calculation, draft, final approval; S.A.: measurements, calculation, draft, final approval; C.J.P.: preparation of figures, final approval; AL. V.: conception, draft, final approval; I.T.: idea, writing, calculation, draft, final approval;

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the staff of Westkampschool, Bielefeld Sennestadt, for their invaluable support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Xiong, J.; Hsiang, E.L.; He, Z.; Zhan, T.; Wu, S.T. Augmented reality and virtual reality displays: emerging technologies and future perspectives. Light Sci Appl. 2021, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan JYK, Holsinger FC, Liu S, et al. Augmented reality for image guidance in transoral robotic surgery. J Robot Surg 2020, 14, 579–583.

- Scherl C, Stratemeier J, Rotter N, et al. Augmented reality with hololens (r) in parotid tumor surgery: A Prospective Feasibility Study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2021, 83, 439–448.

- Necker FN, Chang M, Leuze C, et al. Virtual resection specimen integration using augmented reality holograms to guide margin communication and flap sizing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2023, 169, 1083–1085.

- Lui JT, Dahm V, Chen JM, et al. Using augmented reality to guide bone conduction device implantation. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 7182.

- Liu WP, Azizian M, Sorger J, et al. Cadaveric feasibility study of da Vinci Si-assisted cochlear implant with augmented visual navigation for otologic surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014, 140, 208–214.

- Lakomek, A.; Eichler, T.; Meyer, M.; Höing, B.; Dudda, M.; Lang, S.; Arweiler-Harbeck, D. Muscular tension in ear surgeons during cochlear implantations: does a new microscope improve musculoskeletal complaints? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 282, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland-Elliott, T.; Marineni, S.; Patel, N.; Ameerally, P.; Mair, M. Novel use of a robot for microvascular anastomosis in head and neck surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024, S0266-4356(24)00540-0.

- Piloni, M.; Bailo, M.; Gagliardi, F.; Mortini, P. Resection of Intracranial Tumors with a Robotic-Assisted Digital Microscope: A Preliminary Experience with Robotic Scope. World Neurosurg. 2021, 152, e205–e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichler, T.; Lakomek, A.; Waschkies, L.; Meyer, M.; Sadok, N.; Lang, S.; Arweiler-Harbeck, D. Two different methods to digitally visualize continuous electrocochleography potentials during cochlear implantation: a first description of feasibility. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 2913–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boedts, M.; Buechner, A.; Khoo, S.G.; Gjaltema, W.; Moreels, F.; Lesinski-Schiedat, A.; Becker, P.; MacMahon, H.; Vixseboxse, L.; Taghavi, R.; Lim, H.H.; Lenarz, T. Combining sound with tongue stimulation for the treatment of tinnitus: a multi-site single-arm controlled pivotal trial. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 6806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Danilov, Y.P.; Tyler, M.E.; Skinner, K.L.; Hogle, R.A.; Bach-y-Rita, P. Efficacy of electrotactile vestibular substitution in patients with peripheral and central vestibular loss. J Vestib Res. 2007, 17, 119–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, B.; Flynn, S.; Proffitt, R.; Chang, C.Y.; Rizzo, A.S. Development of an interactive game-based rehabilitation tool for dynamic balance training. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2010, 17, 345–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar BJ, Salorio-Corbetto M, Picinali L, Mahon M, Nightingale R, Somerset S, Cullington H, Driver S, Rocca C, Jiang D and Vickers D Virtual reality games for spatial hearing training in children and young people with bilateral cochlear implants: the “Both Ears (BEARS)” approach. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1491954.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).