1. Introduction

Spatial sound plays a crucial role in human auditory perception, allowing individuals to locate sound sources and navigate their environment effectively. Binaural rendering techniques aim to reproduce spatial audio experiences over headphones by simulating the way sound interacts with the human head and ears. These technologies have gained significant attention in various fields, including gaming, virtual reality (VR), and immersive audio experiences [

1,

2]. However, the accuracy of sound source localization depends on multiple factors, such as the rendering algorithm, head-related transfer functions (HRTFs), and listener adaptation [

3,

4].

Previous studies have explored the impact of different auditory environments on spatial perception. Mróz and Kostek [

5] investigated the differences in perceptual responses to spatial audio presented through headphones versus loudspeakers, highlighting how the reproduction system affects listener perception. Similarly, Moraes et al. [

6] examined physiological responses in a VR-based sound localization task, showing how immersion influences auditory accuracy. Research by Tang [

7] further emphasized the importance of sound in VR applications, demonstrating that spatial audio significantly enhances realism and presence. Additionally, scene-based audio techniques, such as Higher-Order Ambisonics (HOA), have been widely applied in next-generation audio and 360-degree video experiences [

8,

9].

Despite advancements in spatial audio rendering [

10], challenges remain in accurately localizing sound sources, particularly in headphone-based environments. Previous research has shown that head movements improve localization accuracy, while static listening conditions often lead to perceptual ambiguities [

11]. Blauert et al. [

12] developed an interactive virtual environment for psychoacoustic research, highlighting the role of controlled experimental setups in evaluating spatial hearing performance.

This study aims to investigate the accuracy of sound source localization across different binaural renderers, including an ambisonic system and two variations of the Dolby Atmos renderer [

13]. The experiment utilizes VR technology to provide an intuitive method for participants to indicate perceived sound directions [

14]. By analyzing localization precision in different spatial planes, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of binaural audio perception and its implications for immersive sound applications.

2. The role of virtual reality in psychoacoustic research

Virtual Reality (VR) technology has emerged as a crucial tool in psychoacoustic research, providing immersive and controlled environments for studying spatial hearing and sound localization [

14]. VR-based experiments enable researchers to simulate complex auditory scenarios while allowing participants to interact naturally with their surroundings [

15]. This approach enhances the accuracy of perceptual studies by reducing the limitations of traditional laboratory settings.

A study by Moraes et al. [

6] investigated the role of physiological responses in a VR-based sound localization task, demonstrating that VR environments can effectively capture implicit and explicit metrics related to auditory perception. Their findings indicated that physiological measures, such as heart rate variability, are reliable indicators of cognitive load, reinforcing conclusions drawn from the NASA-TLX questionnaire. Moreover, their research emphasized the importance of user-environment interaction in developing spatial auditory skills, suggesting that future studies should involve larger participant groups and a deeper analysis of learning effects.

Another study [

16] evaluated three geometrical acoustic engines to determine their effectiveness in dynamic modeling of acoustical phenomena in interactive virtual environments. The analysis focused on applications in immersive gaming and mobile VR platforms, addressing challenges related to computational constraints in real-time audio processing. The results highlighted the trade-offs between computational efficiency and spatial accuracy in sound rendering, underscoring the need for optimization techniques in VR-based audio research.

Blauert et al. [

12] introduced an interactive virtual environment designed for psychoacoustic research, allowing participants to navigate and engage with spatial auditory scenes. The system provided a flexible platform for presenting complex auditory environments, including both direct and reflected sounds from dynamic sources. Such experimental setups facilitate precise localization studies, enabling researchers to assess human spatial hearing with a high degree of ecological validity. The potential for integrating additional sensory modalities further expands the scope of VR applications in auditory perception studies.

One significant obstacle identified is the potential loss of spatial tracking accuracy for Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) or hand controllers. Such malfunctions can disrupt the virtual environment’s spatial coherence, misaligning the calibrated positions within the virtual space [

16]. Moreover, the usage of speaker systems in conjunction with VR headgear can introduce acoustic distortions. The physical characteristics of VR goggles—namely their size, shape, and material composition—may obstruct the sound’s direct path to the ear, leading to structural reflections or attenuation of sound waves [

1,

2].

Research [

1,

2,

7,

16] has demonstrated that VR and AR glasses alter the interaural sound signals and the overall sound spectrum, potentially degrading the listener’s ability to accurately localize sounds and perceive spatial audio quality. Nevertheless, it has been observed that visual cues provided by the VR system can mitigate these auditory discrepancies, ensuring that the perceived auditory location remains unaffected in most VR applications. [

1] work, offering a database of head-related impulse responses collected with and without HMDs, facilitates the design of compensatory audio filters. These filters aim to restore natural auditory experiences during virtual sound playback, even when VR goggles are worn [

2].

Furthermore, the fidelity of sound localization is also contingent upon the acoustic signal’s properties. Research [

9] evaluated auditory localization using two signal types: pure tones and Gaussian noise, measuring the Minimum Audible Angle (MAA) for each. It was corroborated by [

17] that sound localization precision enhances with broader signal bandwidths. Their findings indicated a significant reduction in MAA values from approximately 10° with tonal stimuli to about 1.5° for wideband signals, varying with the azimuth angle. This underscores the critical role of signal characteristics in optimizing sound localization accuracy within virtual reality settings.

In the VR Tools the pivotal role of auditory delivery is underscored. Sound not only enhances the sensation of presence in virtual environments, as noted by [

18] and [

19], but also surpasses visual stimuli in fostering immersive experiences [

7]. Spatial audio cues in virtual reality environments augment situational awareness, directing user engagement, influencing emotional responses, and disseminating intricate information without burdening the visual sensory channel [

7,

20]. These auditory landscapes are instrumental in defining the essence and ambience of virtual spaces, contributing to a more comprehensive and immersive user experience [

10].

Auditory perceptions during headphone playback significantly differ from those experienced through loudspeaker listening. Notably, there is a sensation of sound originating from within the head, commonly referred to as lateralization. This effect arises from the limitation of sound source localization mechanisms during headphone listening, such as the omission of head-related transfer function (HRTF) considerations. Additionally, factors like bone conduction and environmental reverberation are absent in headphone listening. To mitigate this phenomenon, the effectiveness of employing listener-specific HRTF has been demonstrated. The application of individually tailored HRTF has been observed to substantially reduce the sensation of lateralization among listeners [

21]. Research indicates [

3] that the accuracy of sound source localization during headphone listening significantly decreases for angles ranging from ±15° to ±30°. A somewhat lesser decline in localization accuracy is also noted for angles extending from ±30° to ±60° .

Auditory signals, due to their omnidirectional and continuous nature, facilitate quicker user responses compared to visual cues, enabling users to perceive environmental alterations without the need to visually scan their surroundings [

7,

10,

20].

The evolution of 360° video formats necessitates audio solutions capable of delivering a full-spherical sound experience. The integration of ambisonic technology, occasionally in conjunction with object-based audio, addresses this requirement by enabling spatial playback around the user [

4]. Given the prevalence of headphone usage in VR applications, the ease of converting ambisonic content to a binaural format, combined with the adaptability in sound field manipulation, positions ambisonics as the preferred choice for spatial audio in VR/AR settings [

8].

These examples illustrate the growing significance of VR-based interactive systems in psychoacoustic research. By leveraging immersive interfaces and real-time spatial audio rendering, researchers can gain deeper insights into sound perception mechanisms. The flexibility of VR platforms also makes them well-suited for a wide range of applications, from basic auditory science to practical implementations in virtual and augmented reality technologies.

3. Experiments

This project integrated Virtual Reality (VR) and spatial audio technology to study sound localization in an immersive environment. A binaural rendering system processed spatialized audio, and a custom-based platform ensured real-time interaction, data collection, and analysis.

Developed using Unity (2020.2.6f1) with C#, the platform synchronized VR headset movements with real-time audio stimuli. Hand-held controllers allowed precise pointing at sound sources, while Reaper managed auditory stimulus playback via OSC protocol, integrating with Unity through the XR Integration Toolkit (UnityOSC). The system also employed UnityEngine.XR for controller input and Newtonsoft.Json for result serialization.

The experiment utilized the Oculus Rift (CV1) with Touch controllers and sensors, enabling precise spatial audio assessment [

15]. Participants engaged with a 3D interactive user interface.

3.1. Audio Processing and Software Integration

Spatial audio was rendered through open-source IEM Ambisonic BinauralDecoder [

22], Dolby Atmos Binaural Renderer [

23], and Apple Binaural Renderer [

23], then imported into Reaper DAW, where pre-rendered samples and markers synchronized with Unity via OSC (Open Sound Control) scripts. The Unity environment managed test administration, user interactions, and data recording, refined through preliminary testing to ensure optimal usability.

Participants (25 individuals) completed a tutorial followed by two experimental sessions:

Listeners responded by indicating the perceived localization of each sound by pointing with the controllers. Responses were recorded as azimuth and elevation angle pairs, serialized into JSON format for further analysis.

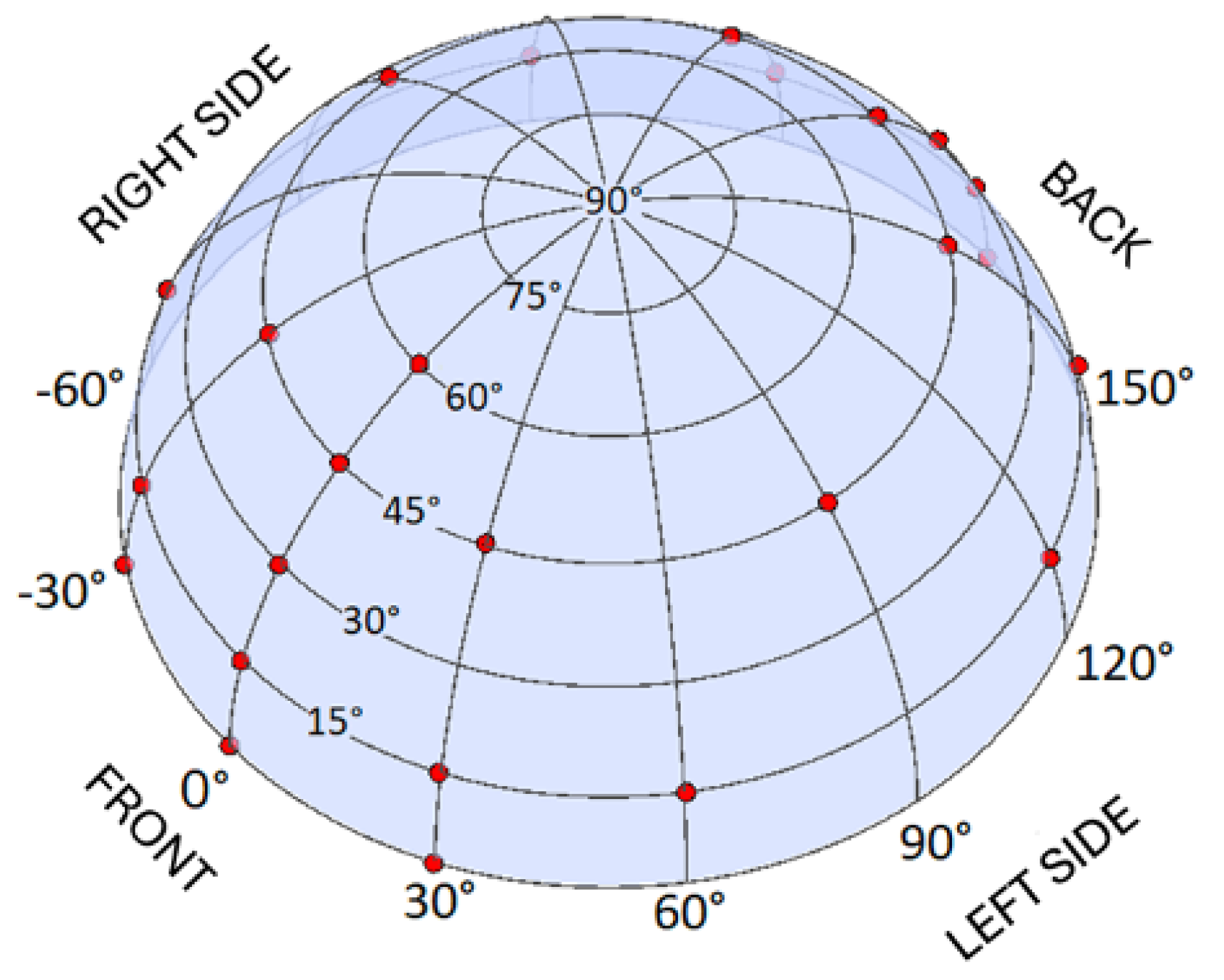

A grid of 25 points was established and distributed across a hemisphere. The selection of their locations was guided by human auditory perception principles (e.g., only a few points were placed within the cone of confusion). The designated points, where the virtual sound source was positioned, are presented in

Figure 1, while their exact coordinates are listed in

Table 1.

A spherical coordinate system was used, with the azimuth angle ranging from -180° to 180° and the elevation angle ranging from 0° to 90°.

3.2. Sound stimuli - Preliminary research

Before conducting the main tests comparing the selected renderers, preliminary testing was carried out using one of them — the IEM renderer. The purpose of this phase was to evaluate whether the designed experiment was understandable and comfortable for the participants. During the test, participants were encouraged to report any concerns regarding the procedure. Particular attention was given to the appearance and usability of the VR interface, as well as the overall duration of the test. Additionally, an assessment was made to determine which type of audio signal was easier to localize — a natural source (human voice) or Gaussian noise.

Using the selected renderer (IEM StereoEncoder + BinauralDecoder), 25 samples were rendered for the natural source and another 25 for the Gaussian noise. Each human voice sample lasted approximately 9 seconds, while a single noise sample had a duration of 500 milliseconds, including a 10 ms fade-in and fade-out time. The noise sample was repeated four times, with a 500 ms pause between repetitions. Each signal type was tested in a separate test session. The positions of the sound source were presented in a randomized order.

Two participants took part in the preliminary test, with neither reporting any hearing issues on the day of the session.

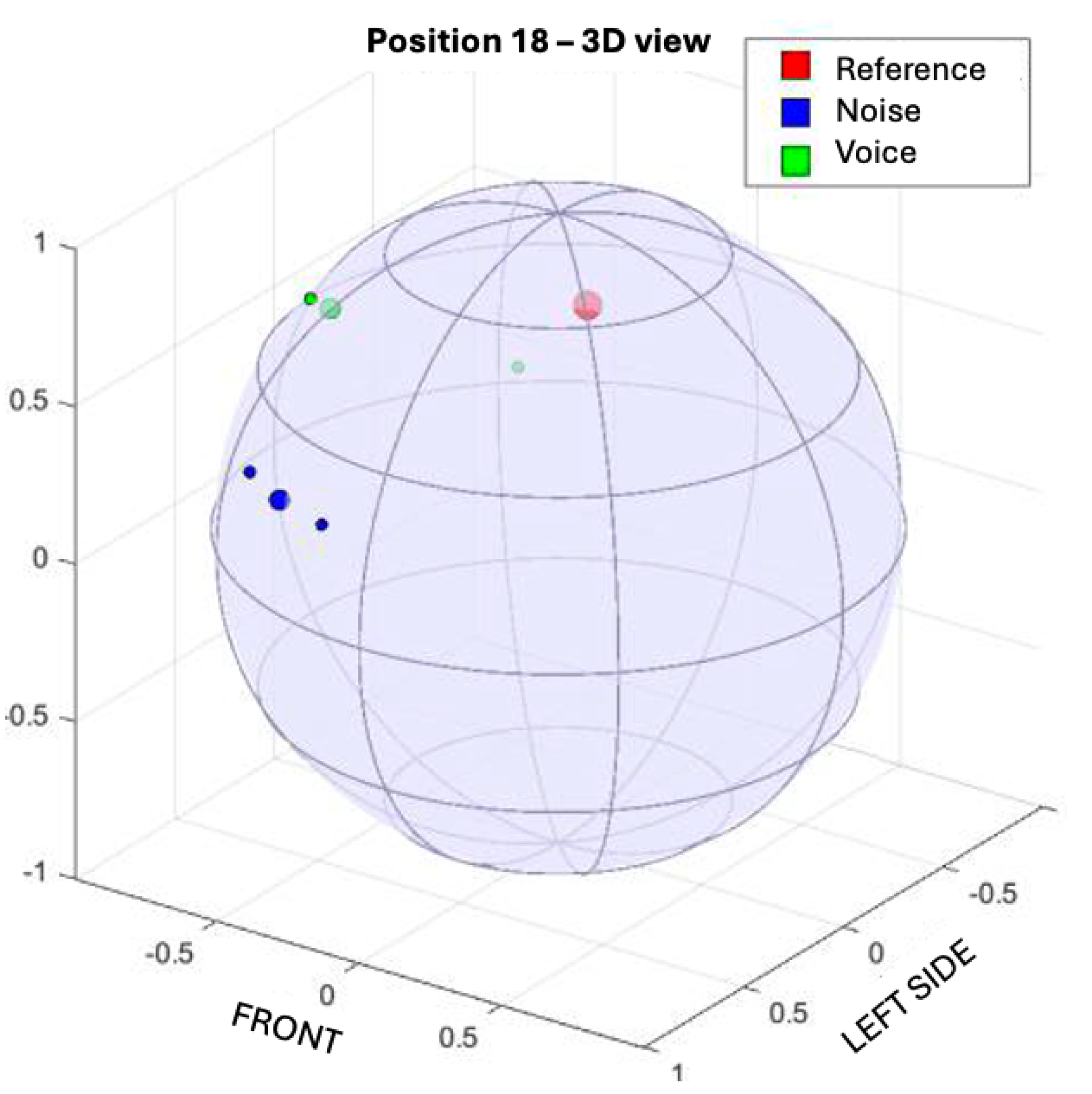

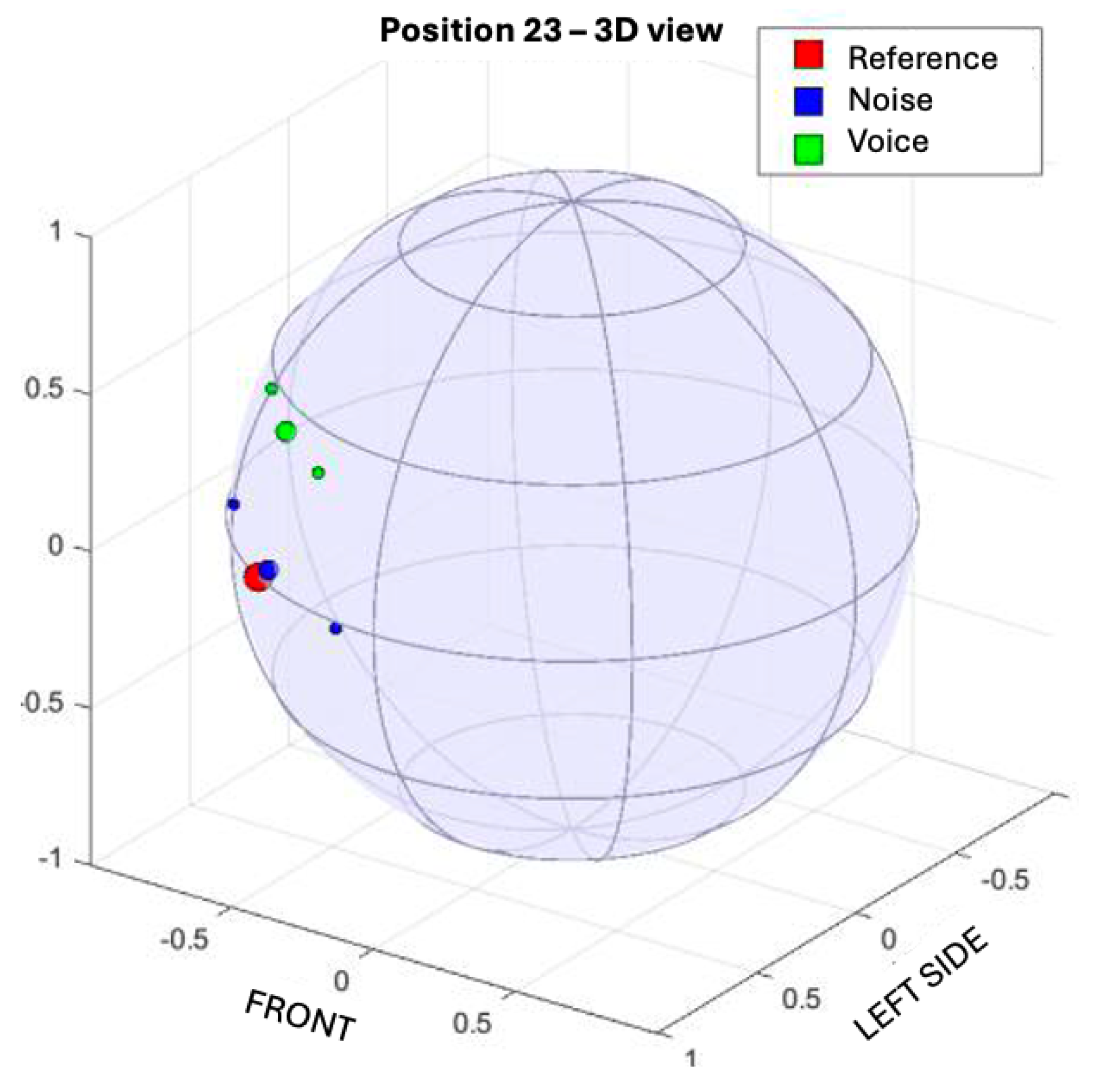

The responses collected during the preliminary tests for all positions and both types of audio signals (noise and human voice) are presented in

Table 2. Additionally responses for selected positions are presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Coordinates of ositions are labeled according to

Table 1.

The preliminary tests allowed refining the system, the testing setup, and the overall experiment. The participants confirmed that the interface was intuitive and did not cause disorientation during the test. They reported feeling comfortable in the created virtual environment.

During the study, participants observed that, subjectively, it was easier for them to localize the natural source (voice) than the noise. However, the available literature indicates that, when studying localization precision, the stimulus should include frequencies above 7 kHz [

24]. In addition, noise is commonly used as a stimulus in psychoacoustic research. For these reasons, Gaussian noise samples were ultimately chosen for the main tests.

Given that only two participants took part, it is difficult to draw conclusions about sound source localization precision. However, the goal of the preliminary tests — to refine the experimental setup — was successfully achieved.

Therefore, gaussian noise samples (500 ms duration, 500 ms pauses, repeated 4 times) were presented from 25 predefined positions on a hemispherical grid. A calibration module ensured accurate tracking, with positional errors observed between 0.5%–4.7% (horizontal) and 0.5%–3.5% (vertical).

4. Results

This chapter summarizes the outcomes of the conducted experiment. In addition to the circular mean, circular standard deviation, and spherical distances between the reference and perceived positions, the accuracy and precision of the listener responses are also discussed. The results are presented graphically on a spherical surface to facilitate the visualization and analysis of listeners’ responses, which is essential for studying the characteristics of spatial audio systems.

4.1. Circular mean and Circular standard deviation

Key statistical values were calculated, including the circular mean and the circular standard deviation, using Equations (

1) and (

2). Calculations were performed within the MATLAB environment using the Circular Statistics Toolbox available [

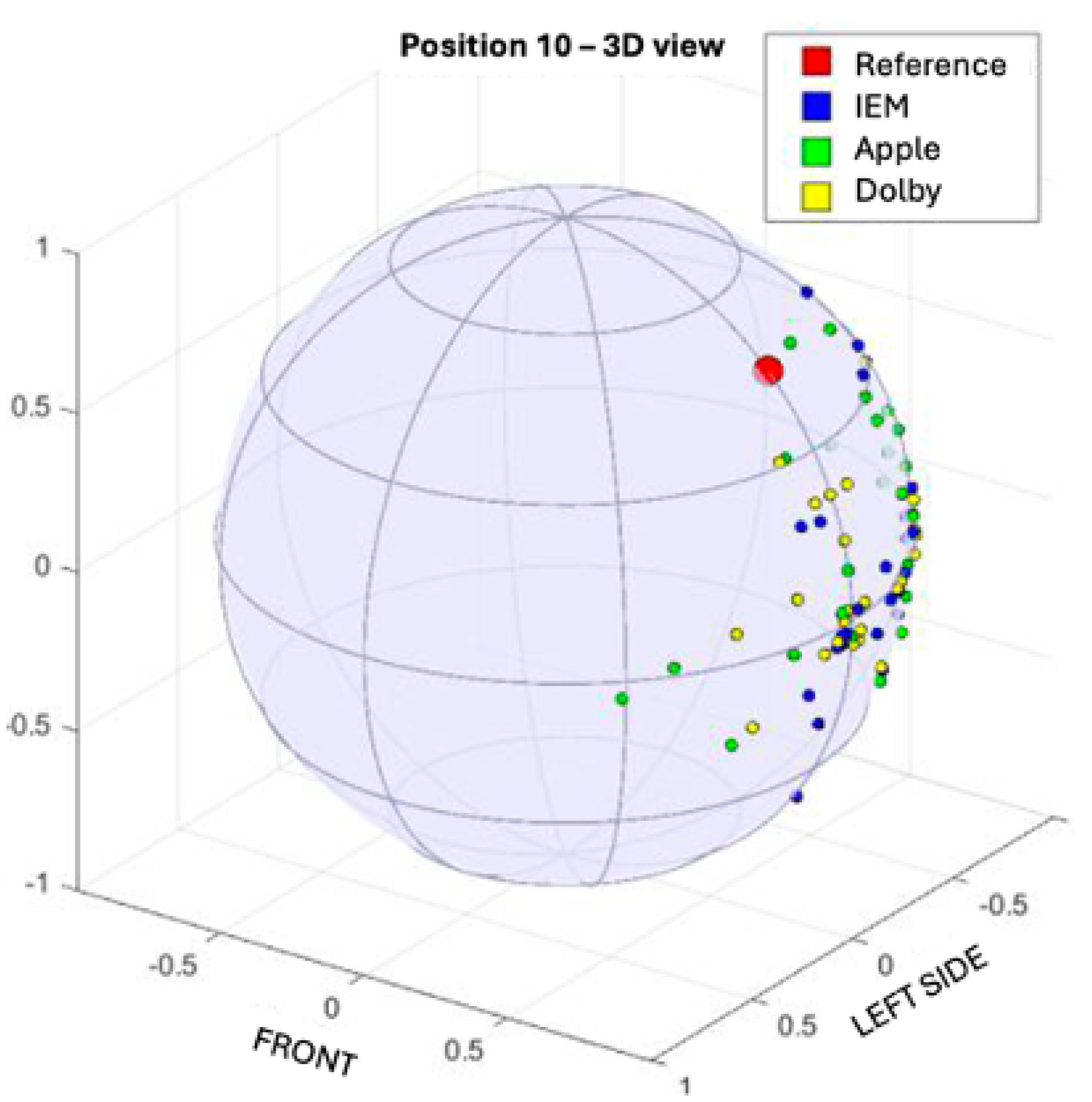

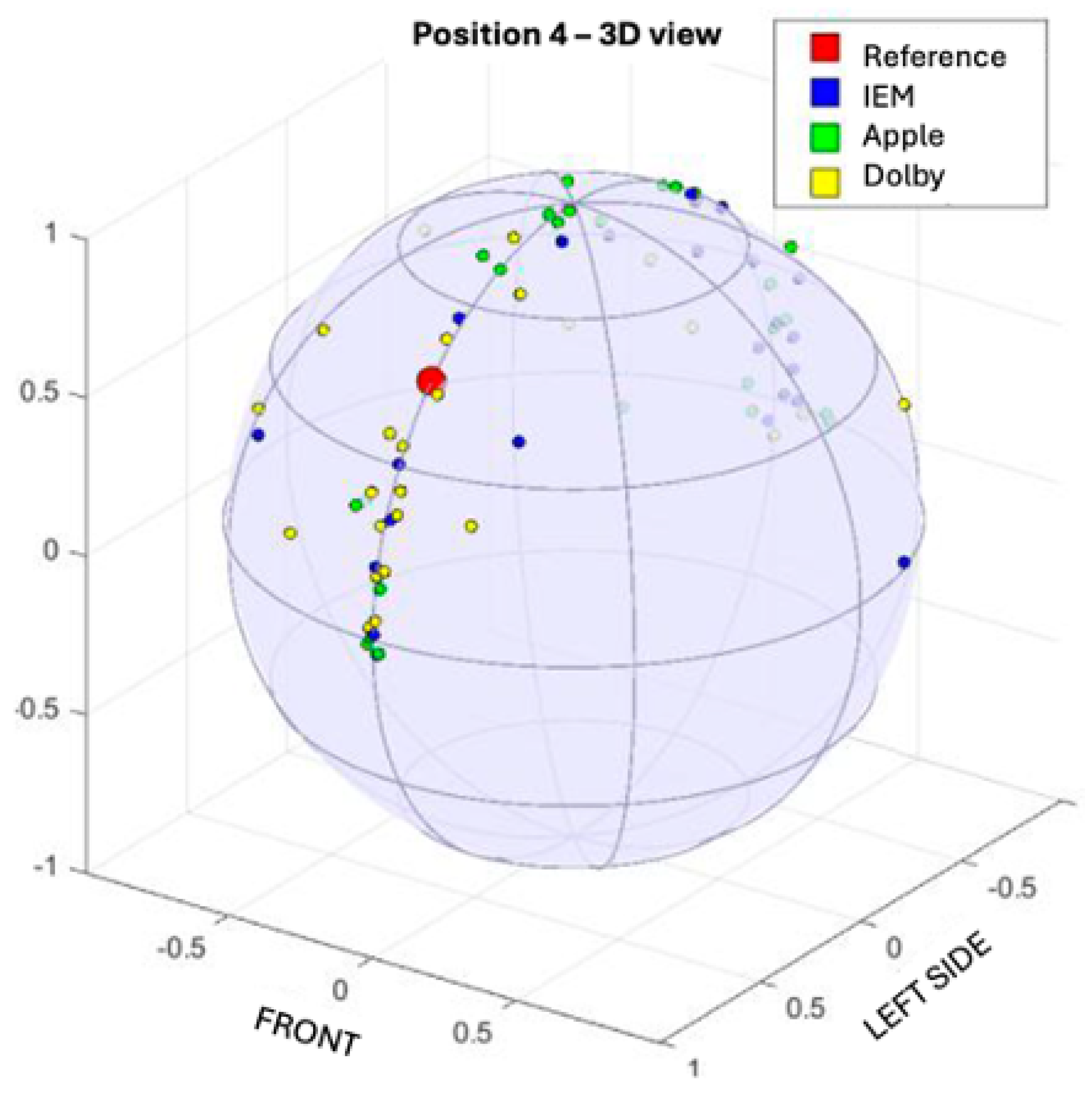

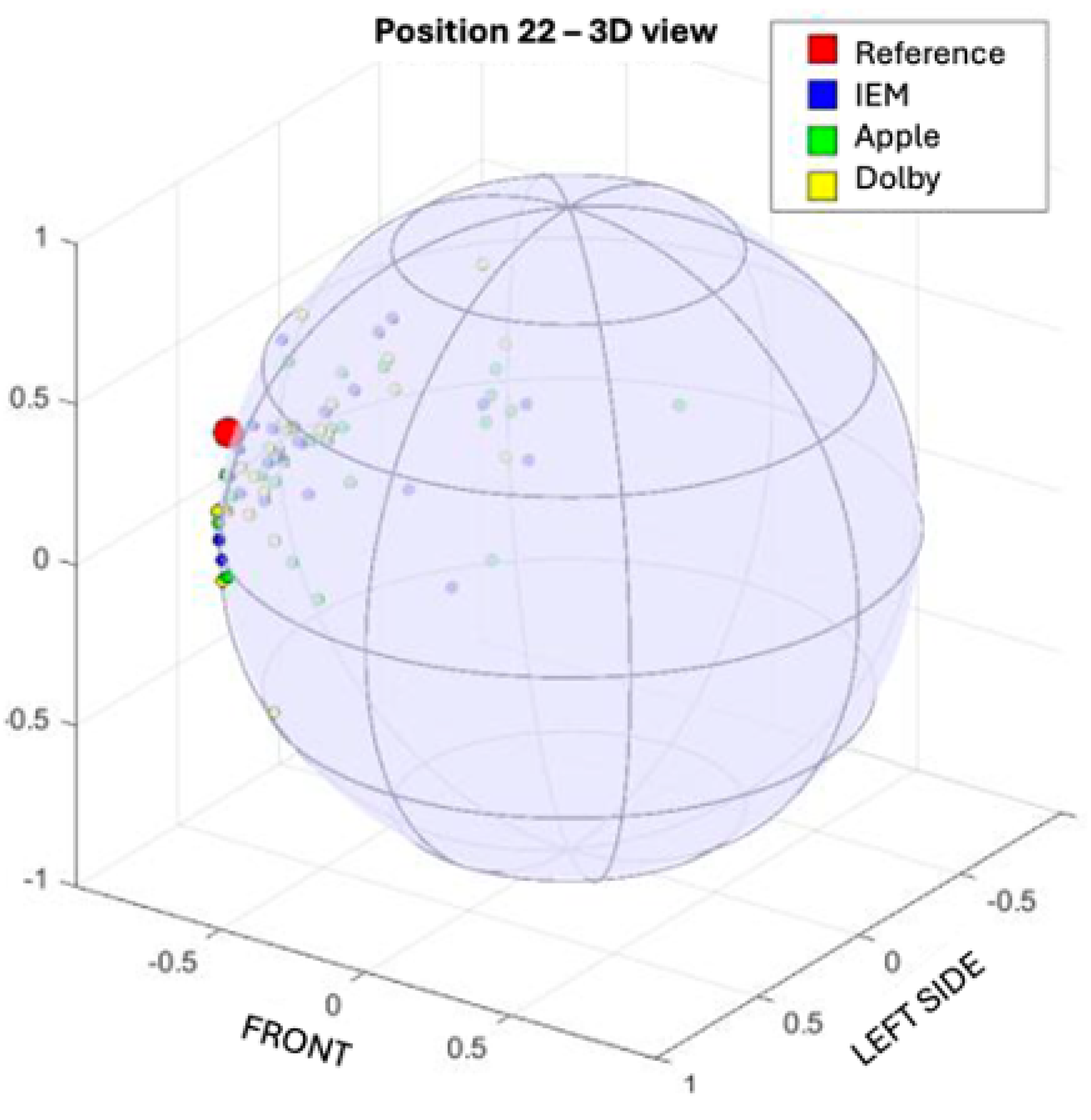

25]. The examples of responses collected for all listeners are presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The mean values have been marked on the plots. The circular standard deviation, which indicates how widely the responses are distributed around the mean, as well as the circular mean itself, are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

where:

– circular mean

– consecutive angles expressed in radians

– circular standard deviation

– mean resultant length

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the mean values and standard deviations for each position, categorized by the tested renderers.

4.2. Distance between points on a sphere

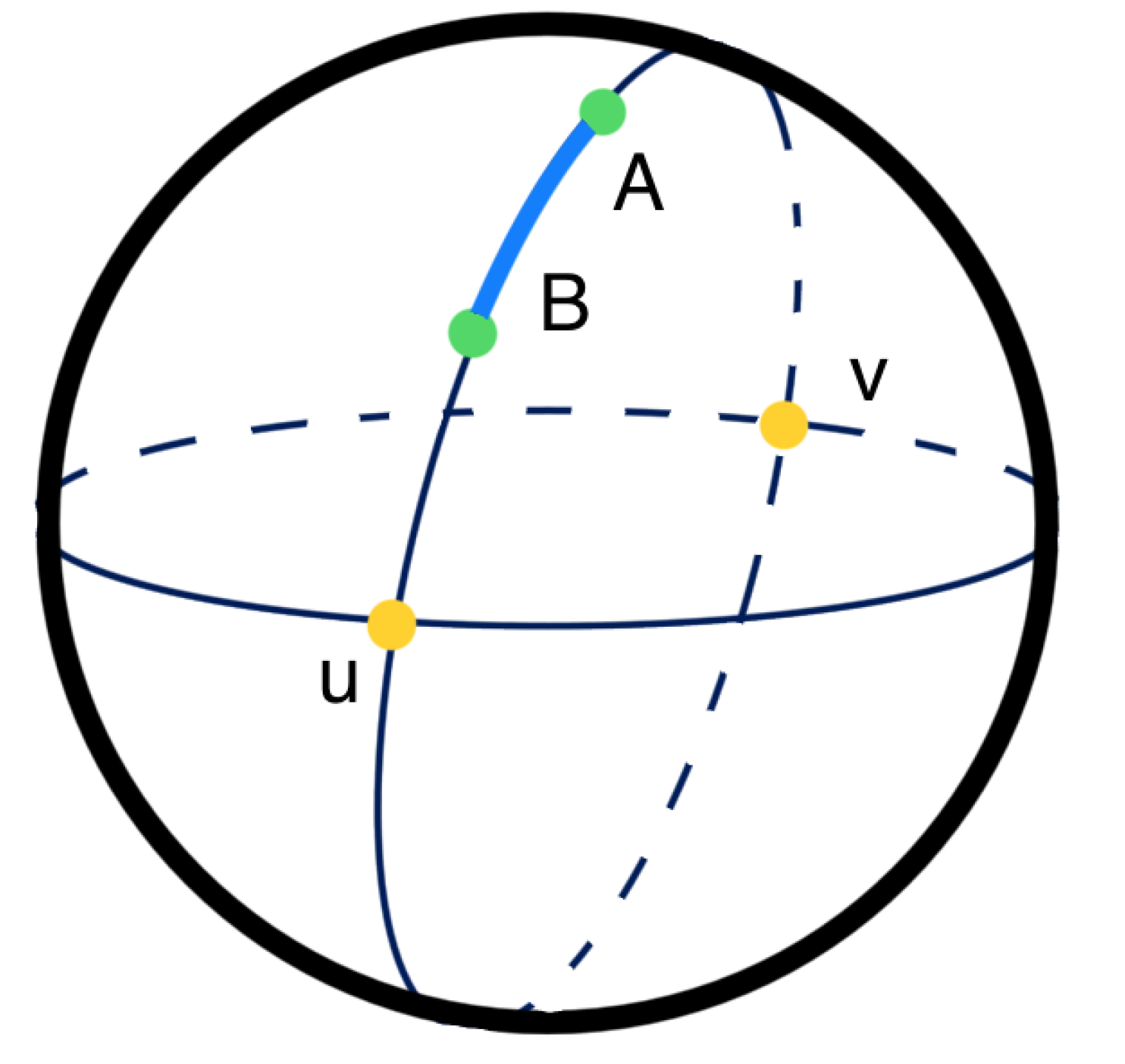

The distance between two points on a sphere was calculated as the length of the arc defined by those points on the so-called great circle [

26]. This is the largest possible circle that can be inscribed in a sphere, and its radius is equal to the radius of the sphere.

Figure 7 shows the distance between two points on the sphere determined using a great circle. In the calculations, the radius of the sphere was assumed to be 1.

Table 5 presents the calculation results along with the shortest distance marked between the reference value and the average value obtained from the responses at each measurement position.

4.3. Precision versus Accuracy

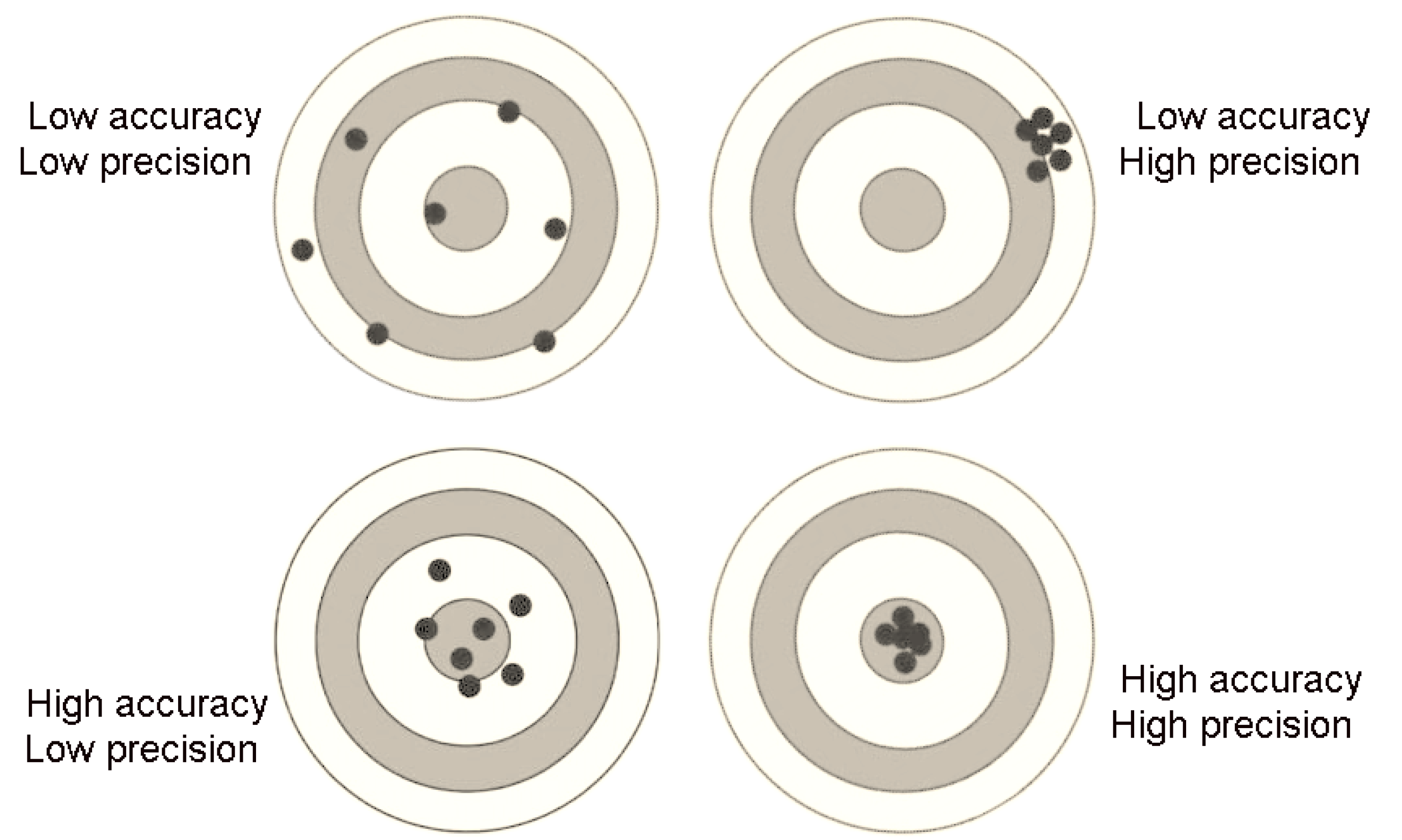

To better understand the following conclusions and analyses, it is worth examining the difference between precision and accuracy of measurement. This is illustrated graphically in

Figure 8.

In the context of this analysis, precision refers to how closely grouped the responses are (i.e., how consistent participants were), while accuracy refers to how close the average response was to the reference sound source location. In other words, a low standard deviation indicates high precision, and a low distance from the reference point indicates high accuracy.

Table 4 presents the standard deviation values of the responses. Cases in which a given renderer had the lowest standard deviation for both elevation and azimuth (i.e., the responses were the least scattered) are listed as follows:

This indicates that, when listening to samples rendered using the Dolby renderer, participants most frequently gave responses that were closely grouped together. Therefore, in the conducted study, the Dolby renderer demonstrated the highest precision.

Further, by analyzing the distances between the reference point and the average response for each renderer at every test position (

Table 5), the number of times each renderer achieved the

lowest distance was counted:

IEM – 5 times,

Apple – 9 times,

Dolby – 11 times.

This means that in the case of the Dolby renderer, the participants’ responses were most often closest to the expected (reference) location of the virtual sound source. Although this time the lead was not as dominant (Apple achieved the best results in only two fewer cases), Dolby still proved to be the most accurate renderer.

Additionally, there were 5 specific test positions (3, 4, 8, 9, and 24) for which the Dolby renderer demonstrated both the highest precision and highest accuracy among all tested renderers. In comparison, neither IEM nor Apple achieved this for any position.

5. Discussion

The collected data provide valuable insights into the precision of sound source localization in binaural listening, depending on the spatial position of the source. By analyzing the response distributions, circular means, and standard deviations, several key observations emerge:

Greater response dispersion for front-facing sources: Responses for centrally positioned sound sources at the front (positions 1–5) were more scattered, whereas responses for rear sources (positions 11–13) were more concentrated, as indicated by lower standard deviation values. This effect was particularly noticeable in the azimuth plane (

Table 4).

Correct hemisphere identification with small shifts: When the sound source was shifted slightly in the horizontal plane (e.g., position 6, offset 30° to the left), participants correctly identified the hemisphere, confirming that even minor shifts in azimuth were perceived accurately.

Increased response precision for rear-located sources: The further behind the listener the virtual sound source was placed, the more concentrated the responses were around it.

Tendency to localize sound sources behind the head: A striking observation is that 63 out of 75 mean response values were positioned behind the listener (azimuth angle between 120° and 180° or -120° and -180°). This suggests that participants had difficulty localizing sound sources in front of them (

Table 3).

Limited accuracy for front-facing sources

Smaller variations in elevation perception: Differences between mean values were smaller in the vertical plane (elevation angle) than in the horizontal plane (azimuth angle). This suggests that listeners perceived less variation in the up-down positioning of the sound source (

Table 3).

Largest errors for front-centered positions: The greatest differences between mean listener responses and the reference values occurred for front-central positions (1–5) (

Table 3).

These findings reinforce existing knowledge about the challenges of front-facing localization in binaural rendering and suggest that sound sources positioned behind the listener tend to be perceived with higher precision.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate variations in sound source localization accuracy depending on the spatial position of the source and the binaural rendering method.

Participants frequently reported difficulty in accurately placing the sound source in front of them. In many cases, they perceived the sound as being "inside the head," which aligns with the known phenomenon of lateralization [

27]. On the other hand, sounds coming from the sides were easier to localize, and participants had no difficulty determining the primary direction (left or right).

Significant differences were noted among the various binaural renderers. The Dolby Renderer, utilized in Dolby Atmos technology, demonstrated the highest accuracy, with listener responses being the closest to the expected localization points.

Additionally, VR technology and spatial audio play a crucial role in advancing psychoacoustic research. The combination of these technologies enhances experimental control while also significantly improving participant immersion, leading to more reliable and naturalistic data collection.

Future research could explore personalized HRTF (Head-Related Transfer Function) adjustments to enhance front-localization precision and investigate the role of head movements in refining spatial perception.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Robotics, AGH University of Krakow, Research Subsidy No. 16.16.130.942. All proprietary names and technologies mentioned in this article remain the intellectual property of their respective creators. The results and conclusions presented reflect the outcomes of a limited study conducted under specific conditions and should not be interpreted as an endorsement or ranking of the tested solutions. The selected technologies are widely used and commercially available in nearly all multimedia devices, making their commercial names commonly recognized and broadly applied. The study and experiments were conducted with complete scientific integrity and neutrality. This research was neither funded nor influenced by the manufacturers of the tested solutions, ensuring the absence of any conflict of interest.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, H. A Conceptual Model of Immersive Experience in Extended Reality, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J. Acoustic Virtual Reality: An Introductory Research for Application. Technical report, Delft University of Technology, 2020.

- Sharma, N.K.; Gaznepoglu, Ü.E.; Robotham, T.; Habets, E.A.P. Two Congruent Cues Are Better Than One: Impact of ITD–ILD Combinations on Reaction Time for Sound Lateralization. JASA Express Lett. 2023, 3, 054401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagasti, A.; Pietrzak, A.; Martin, R.; Eguinoa, R. Localization of Sound Sources in Binaural Reproduction of First and Third Order Ambisonics. Vib. Phys. Syst. 2023, 33, 2022214. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, B.; Kostek, B. Pursuing Listeners’ Perceptual Response in Audio-Visual Interactions—Headphones vs. Loudspeakers: A Case Study. Arch. Acoust. 2022, 47, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, A.N.; et al. The Role of Physiological Responses in a VR-Based Sound Localization Task. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 122082–122091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. Research on the Application of Sound in Virtual Reality. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 44, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Peters, N.; Sen, D. Scene-Based Audio and Higher Order Ambisonics: A Technology Overview and Application to Next-Generation Audio, VR, and 360 Video. Technical report, EBU Tech., 2019.

- Sochaczewska, K.; Małecki, P.; Piotrowska, M. Evaluation of the Minimum Audible Angle on Horizontal Plane in 3rd Order Ambisonic Spherical Playback System. In Proceedings of the Immersive and 3D Audio: From Architecture to Automotive; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bosman, I.; Buruk, O.; Jørgensen, K.; Hamari, J. The Effect of Audio on the Experience in Virtual Reality: A Scoping Review. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gari, S.V.A.; Schissler, C.; Robinson, P. Perceptual Comparison of Efficient Real-Time Geometrical Acoustics Engines in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the AES Int. Audio Games Conf. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blauert, J.; et al. An Interactive Virtual-Environment Generator for Psychoacoustic Research. I: Architecture and Implementation. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2000, 86, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Małecki, P.; Stefańska, J.; Szydłowska, M. Assessing Spatial Audio: A Listener-Centric Case Study on Object-Based and Ambisonic Audio Processing. Arch. Acoust. 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahu, H.; Carpentier, T.; Noisternig, M.; Warusfel, O. Comparison of Different Egocentric Pointing Methods for 3D Sound Localization Experiments. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2016, 102, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, L.C.; Valdés, B.A.; Loos, H.M.V.D. Determining the Accuracy of Oculus Touch Controllers for Motor Rehabilitation Applications Using Quantifiable Upper Limb Kinematics: Validation Study. JMIR Biomed. Eng. 2019, 4, e12291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, A.; Lund, K.D.; Marschall, M.; Dau, T. Sound Source Localization with Varying Amounts of Visual Information in Virtual Reality. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, D.; Grantham, W. Minimum audible movement angle in the horizontal plane as a function of stimulus frequency and bandwidth, source azimuth, and velocity. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1992, 91, 1624–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgarno, B.; Lee, M.J.W. What are the learning affordances of 3-D Virtual Environments? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2010, 40, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapralos, B.; Jenkin, M.; Milios, E. Virtual Audio Systems. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2008, 17, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilling, R.; Shinn-Cunningham, B.G. Virtual Auditory Displays. In Handbook of Virtual Environments; Stanney, K., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, W.M.; Wittenberg, A. On the externalization of sound images. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1996, 99, 3678–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zotter, F.; Frank, M. All-Round Ambisonic Panning and Decoding. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 2012, 60, 807–820. [Google Scholar]

- Pfanzagl-Cardone, E. The Dolby ‘Atmo’ System. In The Art and Science of 3D Audio Recording; Springer Int. Publ.: Cham, 2023; pp. 143–188. [Google Scholar]

- Roffler, S.K.; Butler, R.A. Factors that influence the localization of sound in the vertical plane. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1968, 43, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Circular Statistics Toolbox (Directional Statistics). Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/10676-circular-statistics-toolbox-directional-statistics (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Distance between two points on sphere 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-20.

- Freyman, R.L.; Balakrishnan, U.; Zurek, P.M. Lateralization of Noise-Burst Trains Based on Onset and Ongoing Interaural Delays. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).