1. Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is increasingly used in medicine due to its ability to simulate 3D environments with reduced risk to patients. Use of VR improves the spatial awareness, facilitates the visualization of complex 3D data due to depth and volume perception, and simulates real environments, benefiting cases such as diagnostics, surgery planning, and medical education [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Despite the potential of VR in medical applications, there are interaction challenges. Traditional input methods, such as controllers, often fail to replicate the precision and intuitiveness of familiar 2D interfaces like a mouse and keyboard, making tasks such as typing and information retrieval cumbersome in 3D environments [

9]. Cluttered interfaces and overly complex controls further increase cognitive load, limiting smooth operation and user experience. The absence of standardized interaction paradigms across VR systems complicates skill transfer and limits usability [

10]. These challenges arise from limitations in locating and operating tools in VR, coupled with the unfamiliarity of interacting with virtual objects, which contrasts with habitual 2D interface use [

11].

Speech-based interaction offers a promising alternative to address these challenges. Voice commands provide a hands-free method to streamline interaction, reduce cognitive burden, and enhance accessibility in VR systems[

12]. However, their effectiveness depends on the integration of robust natural language processing (NLP) techniques to ensure accurate speech recognition and intuitive user interfaces tailored to specific use cases. Implementing such systems can significantly improve task efficiency and user satisfaction, paving the way for broader adoption of VR in healthcare [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

This research focuses on assistive technologies in VR, particularly the use of spoken voice commands, and evaluates their usability in medical Virtual Reality Systems. Chatbot based assistive technologies are not new, they have demonstrated significant benefits across various industries [

17]. Recent advancements in natural language processing (NLP), including Large Language Models (LLMs) for generative text, transformer models and later BERT and other models [

18,

19], have improved text classification, intent recognition, and information retrieval. Combined with advanced speech-to-text technologies, these innovations enable efficient human-machine interaction, making VR systems more intelligent and adaptive [

15,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The research specifically explored speech commands for tool selection and answering queries in maxillofacial implant surgery. This study aimed to design an intelligent speech assistant and evaluate its impact on usability and cognitive load in real time medical applications. We studied the following research questions.

-

RQ1:

How does the use of intelligent speech interfaces affect usability metrics such as ease of control, comfort, accuracy of commands, satisfaction in response, finding controls, learning and adapting, recovery from mistakes, and naturalness and cognitive load metrics like physical demand, mental demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration.

-

RQ2:

What are the advantages, limitations, general opinion, and expectations from the speech interfaces in VR for medical purposes?

2. Background

Several prior studies have explored the advantages of VR in the medical field, demonstrating simulation of complex medical procedures, improving diagnostics, and enhancing surgical planning [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

24]. For example, in surgical planning, VR has been shown to improve the accuracy of tumor localization in liver resection [

25,

26]. Similarly, in head and neck cancer surgery, VR allows a more detailed assessment of tumor extent and surrounding anatomical structures, leading to improved surgical planning and better oncological outcomes [

27]. In skull base neurosurgery, the complex anatomy and proximity of critical neurovascular structures make precise planning possible [

28]. Each of these studies proves the capabilities of XR (extended reality) technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) in the medical domain.

VR applications suffer from many interaction challenges as discussed in the Introduction. To address these issues, various studies have explored integrating additional modalities such as haptics [

4,

29,

30], speech[

13,

31,

32], gesture-based controls [

29,

33] and gaze [

34] to enhance user interaction. These interaction problems are also solved by adopting a multimodal approach to create more immersive, intuitive, and responsive VR experiences [

35]. Among these modalities, speech is regarded as the most natural because it mirrors the way humans inherently communicate with one another.

Assistive technologies such as chatbots and speech based systems such as Alexa have become pretty common in daily activities and various personal and industrial domains [

17]. It has been possible through various state of art NLP techniques enabling efficient speech systems [

15,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Previous research has demonstrated the specific utility of speech-based systems in various medical use cases. An example is the use of medical decision support system that integrates real-time speech interfaces with deep neural networks (DNN) to predict suitable therapies based on patient medical history. It reduced manual data entry time and allowed more focus on diagnosis and patient care [

15].

Similarly, speech recognition has been leveraged to control virtual tools in immersive environments, improving efficiency, realism, and user engagement through NLP techniques such as intent classification [

32]. In VR, voice-controlled mode switching has been shown to be more intuitive and satisfactory than traditional button-based methods, offering a coherent interaction experience for healthcare professionals [

31]. Speech interfaces have also demonstrated significant utility in high-pressure medical settings, such as surgical environments, where they improve task execution and retention of clinical skills [

16]. For training applications, the DIET (Dual Intent Entity Transformer) model has been employed to classify a wide range of intents, creating immersive and effective medical learning environments [

13]. Furthermore, natural language understanding has been advanced in Virtual Standardized Patients (VSPs) by integrating speech recognition and hybrid AI techniques, enabling enhanced history-taking skills and improving simulation fidelity [

14]. Another study that used the use of large language models to navigate around medical Virtual Reality found various positive remarks [

36,

37] although using LLM had an observed latency of 3-4 seconds and 1.5-1.75 seconds depending on the tasks, which was not suitable for flawless medical interactions. These studies provide insights into usage of machine learning principles in medical domains using speech.

However, there is a lack of research exploring the application of speech interfaces in surgical planning scenarios, where such systems could function as virtual assistants to support secondary tasks in a real-time environment. These tasks may include retrieving surgical tools or providing context-specific information about the virtual environment, thereby improving workflow efficiency and user engagement, especially for new users in VR. Even as users switch between the VR systems and controls are different, the users can interact with any system in the same way, using natural language as long as they have knowledge about the tools, which would be expected from medical professionals. A related study investigated speech interfaces for tool switching, but that was limited to static commands [

31]. The reliance on static commands introduces challenges related to memory recall, potentially disrupting the workflow, and increasing cognitive demands during critical tasks. Furthermore, the lack of adaptive or context-aware design in such systems requires predefined terminology for tools, which may differ from the naming conventions used in real-world surgical practices.

This research addresses these limitations by integrating a dynamic, context-aware verbal assistant capable of interacting naturally with users and adapting to the specific terminology and requirements of the virtual environment. By doing so, it aims to reduce cognitive load, improve the usability of the system, and bridge the gap between existing static command-based interfaces and the flexible and intuitive needs of surgical planning and training scenarios.

3. Materials and Methods

The system design prioritized natural language understanding so that it can be used in all VR systems as long as the user knows about the tools to some extent which is to be expected from medical professionals. Although large language models (LLMs) represent state-of-the-art techniques for handling diverse instructions and generate curated answers, they have several limitations like limited customizability [

38], lack of transparency [

39] and latency [

36,

37]. Small delays can significantly hinder user experience, in a negative way [

40]. Therefore, other approaches were used such as using intent recognition [

13,

41]. Focusing more on interaction side of things, cloud based pre-trained models were chosen such as speech service from Azure [

42].

3.1. System Architecture

The system architecture was designed to integrate Natural Language Processing (NLP) capabilities with a VR interaction framework. Built on the Unity platform and Oculus Meta Quest 3 VR headsets, the architecture featured modular components to support overall speech-driven interactions, intent recognition, and real-time user feedback.

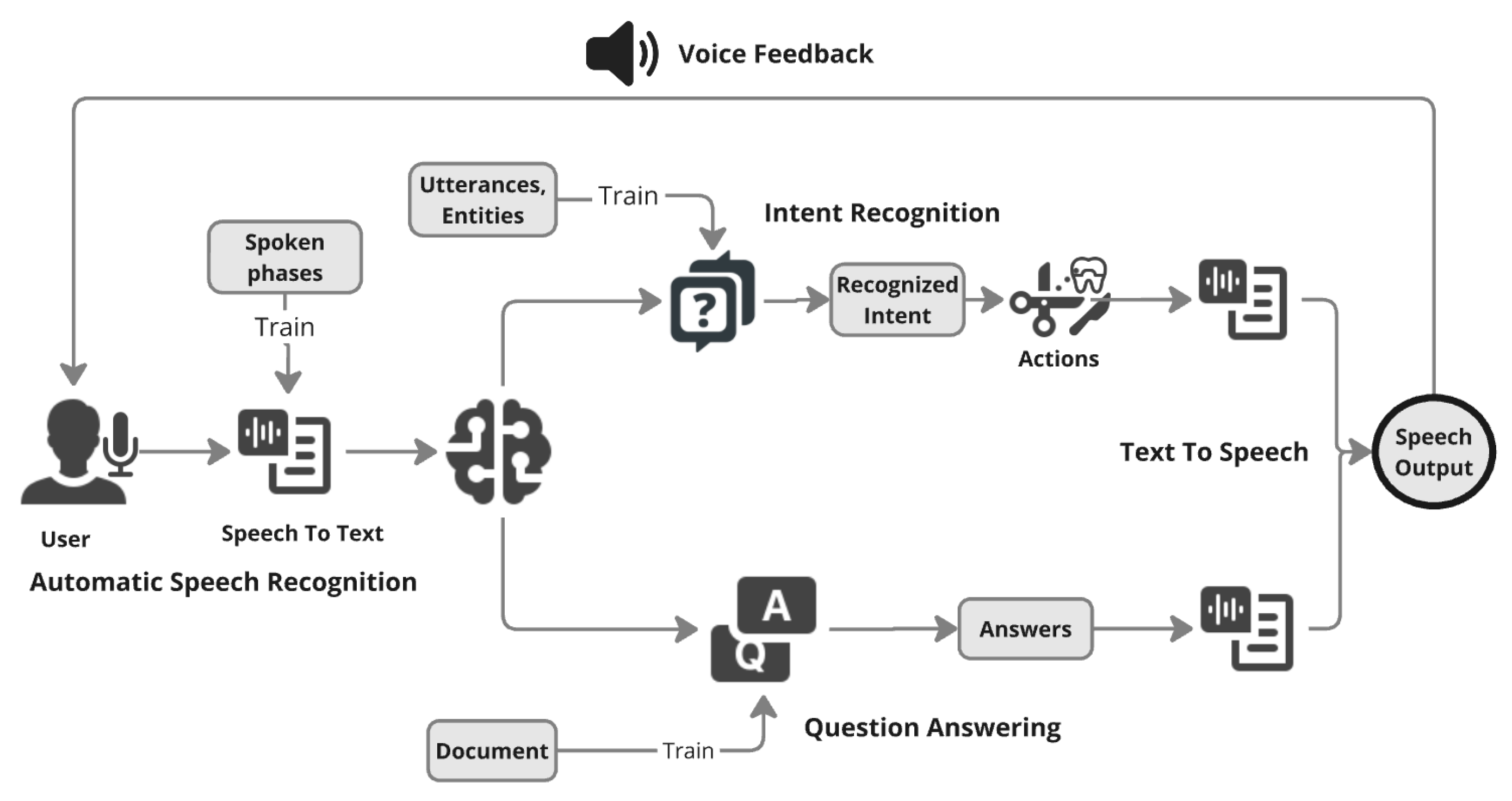

Figure 1 shows key architectural elements, including the NLP pipeline, which consists of Speech-to-Text (STT), Intent Recognition, Question Answering and Text-to-Speech (TTS) components, that facilitate bidirectional communication between users and the VR system. A feedback mechanism was implemented where a logger tracked speech recognition outputs, system responses, and error handling, providing real-time feedback to users in form of audio and visual feedback.

The architecture was designed with a focus on evaluating usability and cognitive load in an exploratory study of speech models. To minimize costs and resources, fewer training examples were used, and limited emphasis was placed on fine-tuning NLP models. This approach prioritized feasibility and preliminary insights over extensive optimization.

3.2. NLP Development

Natural Language Processing components were developed using Azure Cognitive Services, focusing on STT, Intent Recognition, QA functionalities, and Text-to-Speech (TTS). Various speech services were tested, and Azure was selected for its minimal latency due to integration within the same Azure environment.

Azure’s pre-trained STT model was fine-tuned using 20 training examples from people with different tones and accents to improve recognition of medical terminology and diverse vocal patterns. This training resolved issues such as misinterpretation of terms like "sinuses" (previously recognized as "cinuses") and "X-Ray" (misheard as "exray"), ensuring accurate processing of tools and commands such as "Turn on/off the X-Ray Flash Light.", which was seen commonly while testing the STT.

Azure Language Understanding (LUIS) was trained with 20 intents with 15-20 utterances per intent corresponding to different system functionalities. These 20 intents corresponded to all the available feature available in the project and necessary to complete the medical tasks. The major challenge here is classification among short sentences which does not have enough information. Sentences like "Hide all dental implants" and "Show all the dental implants" have a small difference of "hide" and "show" and its related synonyms contrary to relatively long sentences used in [

13,

41]. An iterative approach was used with various combinations of synonyms in training data. Utterances were categorized into entities such as "tools" (e.g., dental implants, X-Ray flashlights etc) and "states" (e.g., activate, hide), ensuring robust command interpretation and handling of synonyms and phrasing variations.

A custom knowledge base enabled dynamic and consistent responses to user queries about system functionality and tools. QA model supported detailed information retrieval, enhancing user support. Although the training example used were small in quantity, the models were trained in iterative manner to make satisfactory results that were observed in development and pilot testing.

3.3. VR Development

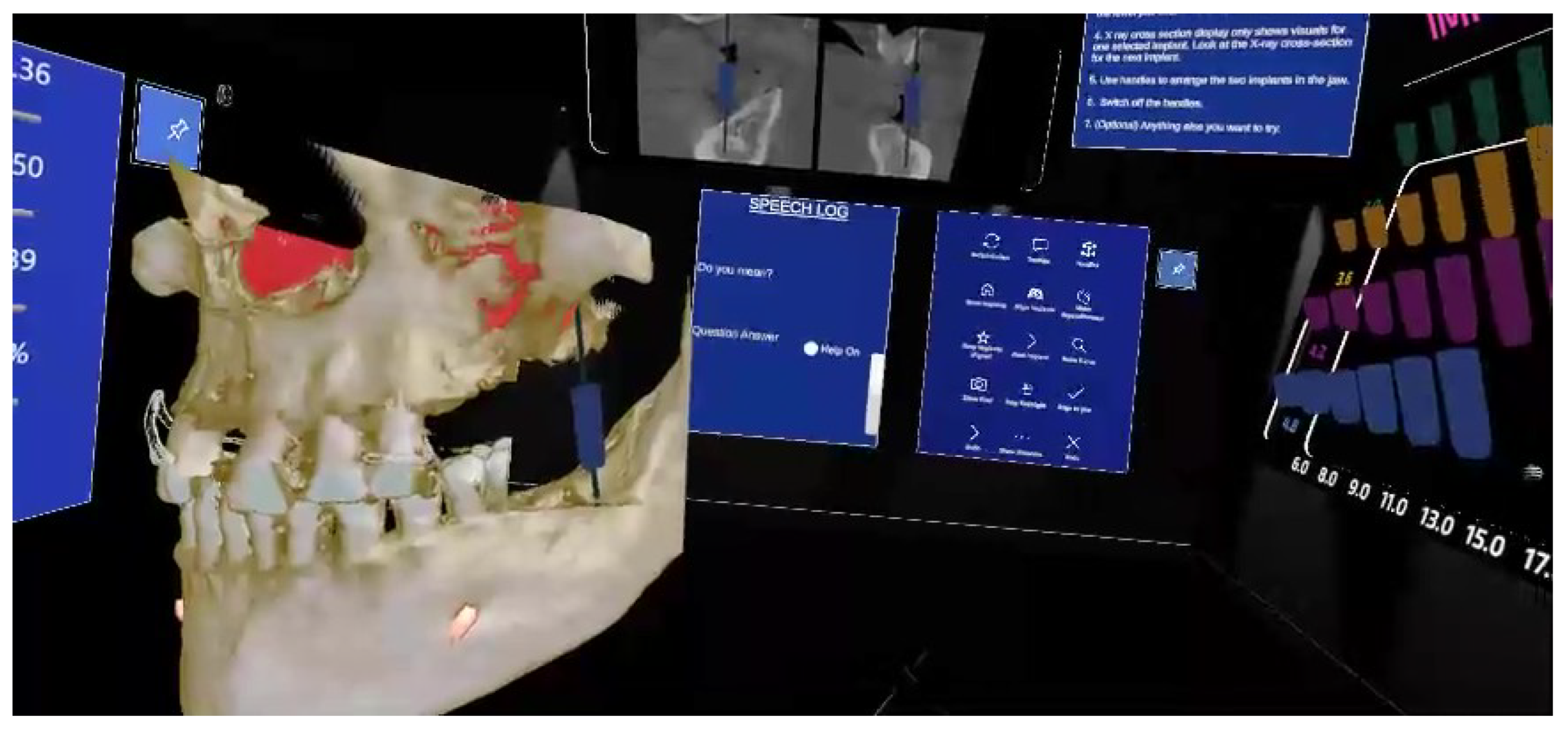

The VR environment, developed using Unity upon Planmeca Romexis software for dental implant and used on the Oculus Meta Quest 3. See

Figure 2 for overall VR environment. The environment included high-fidelity 3D models such as a skull for dental implant placement and a dental implant tray with adjustable implants of varying sizes [

31]. These models provided a realistic representation of medical tools and anatomy, ensuring a practical training experience. Addition to this the VR system allowed interaction through both speech and traditional button controls in the panel. Button panel was used as reference control interface. Speech commands provided a hands-free alternative for the same functions and tools as button panel interface. The control for speech activation was configured using primary button in hand controller to reduce external noises.

A speech interface panel was developed as a logger to provide a visual representation of both spoken words and their recognized intents. This configuration enabled users to monitor the accuracy of their inputs and generated responses, thereby determining whether their speech is correctly recognized and processed through the system’s pipeline. A toggle switch was introduced to switch between question answering and tool selection. Text-to-Speech (TTS) converted system responses into audible outputs, improving accessibility, ensuring correct commands and enhancing the immersive experience. A task panel displayed specific objectives for users to complete, while visual cues and contextual highlights guided interactions with tools and objects. This ensured participants, especially those unfamiliar with medical tools, could navigate and perform tasks effectively.

3.4. Participants

For exploratory purposes, we selected non-medical student participants, ensuring the system could be assessed for usability in a manner consistent with everyday technology usage. The study involved 20 participants aged between 21 and 35 years, with an average age of 25.8 years. The group comprised 10 males and 10 females, representing diverse nationalities. 19 participants were trying medical VR for the first time, and 5 participants had never used VR in any capacity. Participants were briefed about the study’s objectives, tasks, and potential risks before providing informed consent. To minimize learning bias, the sequence of interaction modes was randomized, with 10 participants starting with the speech interface and the other 10 beginning with the button interface.

3.5. Experiment Process

Two instructional videos were shown to familiarize participants with the VR environment. The videos introduced the key components of the VR space, particularly the medical tools that are necessary for dental implant-related activities. These videos demonstrated VR functionalities, including interaction techniques. Participants were trained on operating the hand controllers, including activating speech input via designated controller buttons. They were then given 5-10 minutes to explore the VR environment freely, manipulating 3D skull models, practicing dental implant placement and experimenting on some tools provided by button panel and speech interface.

For those who appeared unsure during the freeform try-out phase, minimal guidance was provided to help them perform basic tasks such as moving objects or toggling implant visibility. Participants were also introduced to the task panel and the question-answering toggle feature, which they would use to retrieve assistance or complete tasks during the experiment. The

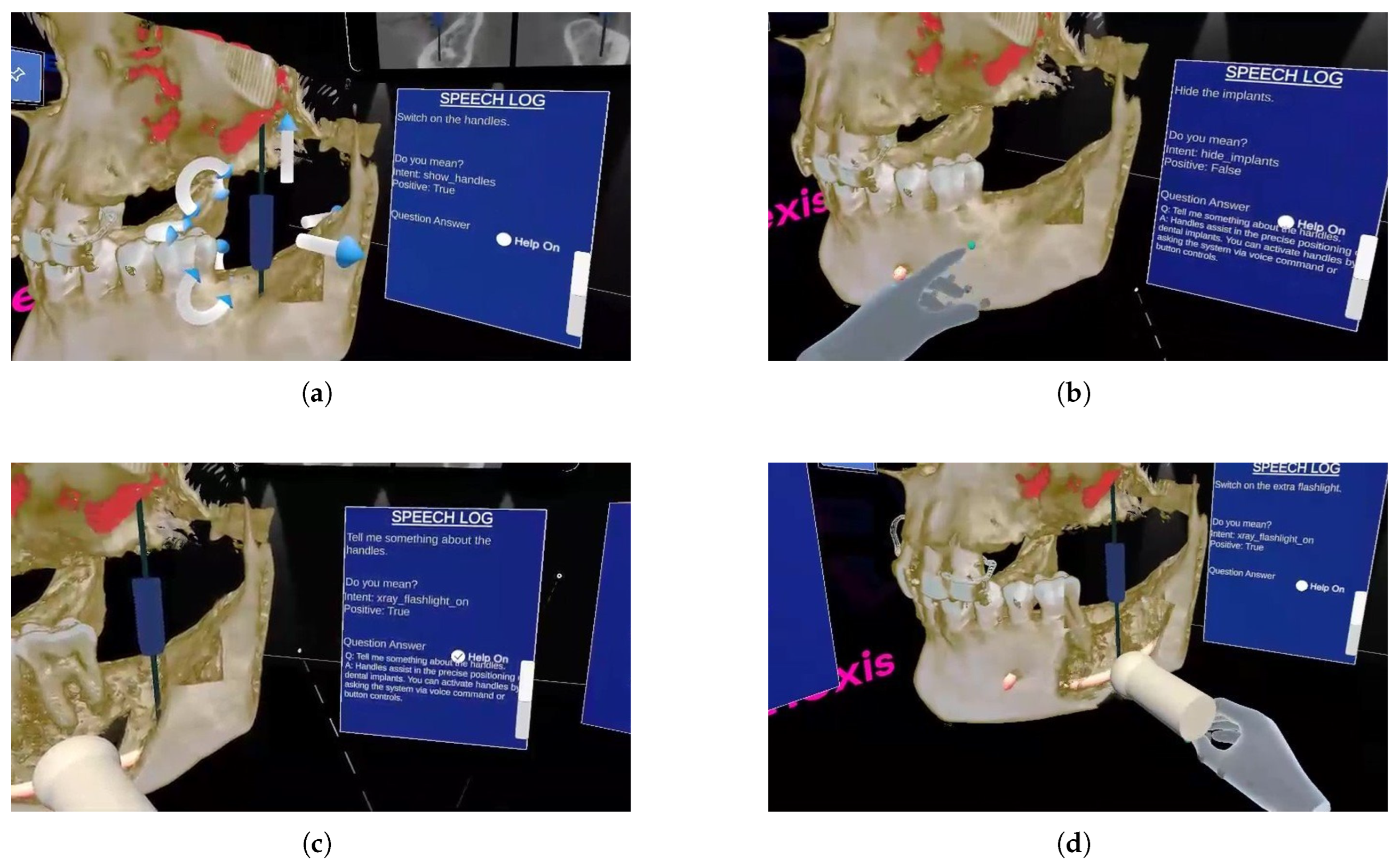

Figure 3 shows the usage of speech for different operations.

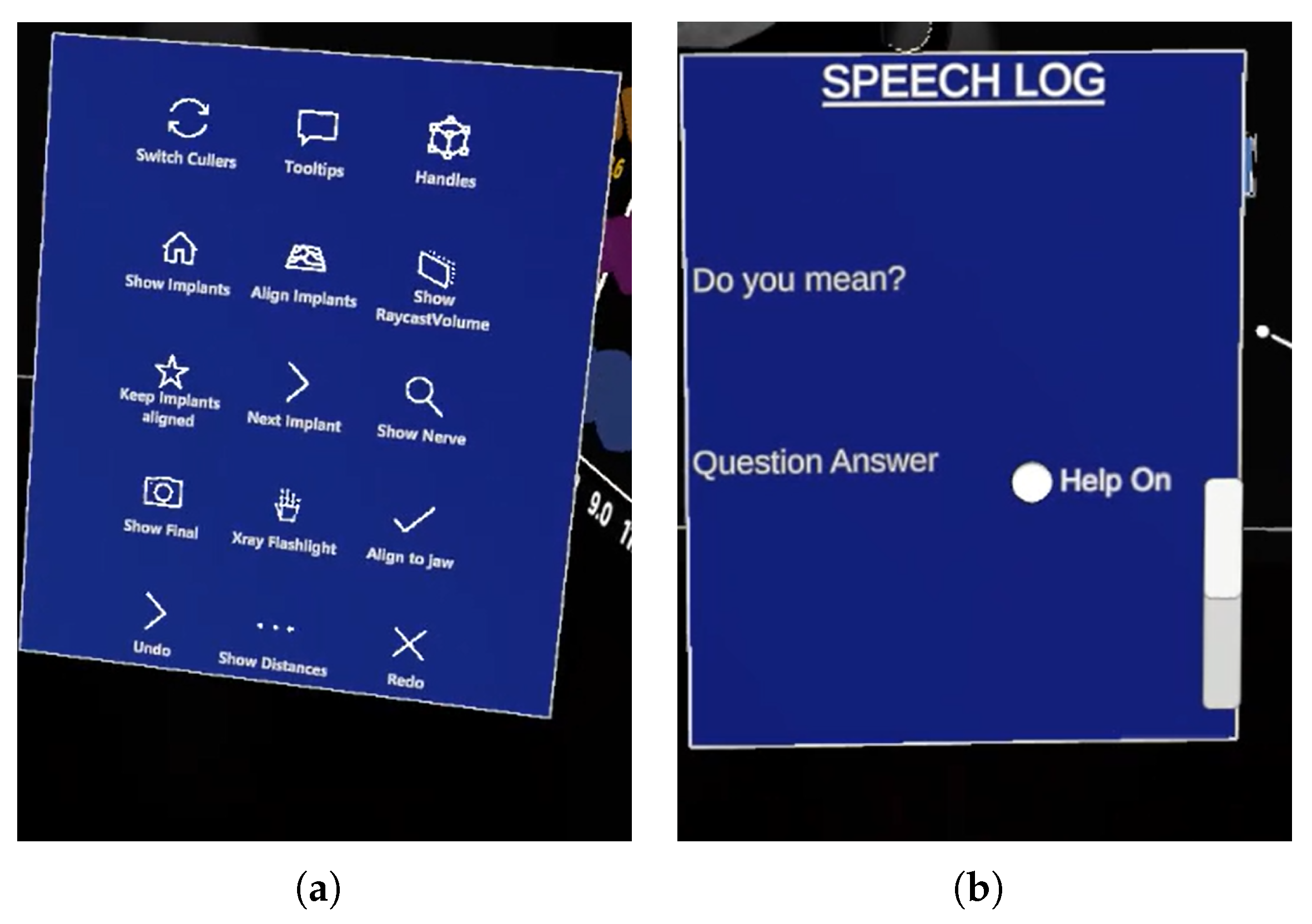

After familiarization, participants were asked to complete predefined tasks using both the speech interface and the button interface (

Figure 4 (a)). The order of interfaces was randomized to minimize order effects. At the conclusion of each interaction mode, participants completed a questionnaire evaluating their experience, specifically focusing on usability and cognitive load metrics.

3.6. Data Collection

The study employed a within-subject design, where each participant interacted with both the speech and button panel interfaces. Usability metrics, including ease of control, comfort, accuracy, satisfaction, and naturalism, were evaluated using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = lowest, 7 = highest). Cognitive load was assessed using the NASA TLX questionnaire, which included components such as mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, effort, and frustration.

Open-ended questions were also included to gather qualitative feedback regarding challenges, preferences, and suggestions for improving the speech interface. To maintain clarity, the "Performance" component of the NASA TLX scale was reversed during data collection, with higher scores indicating better performance. Adjustments were made during analysis to ensure consistency with the original methodology.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

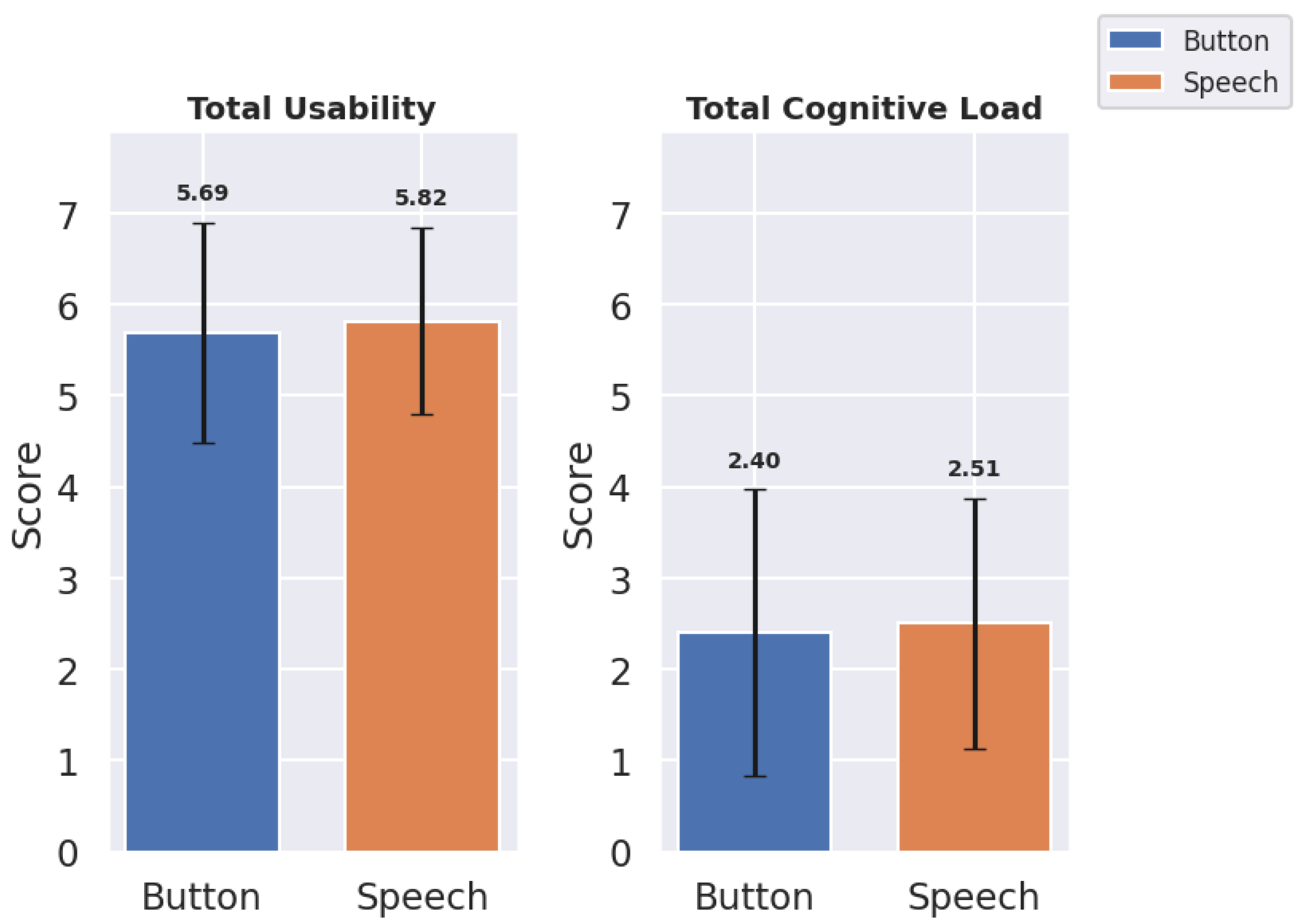

Results for total scores, mean (

M), and standard deviations (

) of usability and cognitive load indicate an overall preference for speech in usability but suggest less overall cognitive load with Button (

Table 1,

Figure 5).

The Speech interface achieved an overall similar total usability score () in comparison with the Button interface (). Also, mean usability score demonstrated similar behavior in case of speech and button interface withs scores () and () respectively. The Button interface exhibited a lower mean cognitive load () than speech (), suggesting that speech may slightly increase cognitive load due to recognition inaccuracies. These findings demonstrate overall results. But for in-depth analysis the metrics used in usability and cognitive load were analyzed.

4.1.1. Usability Metrics

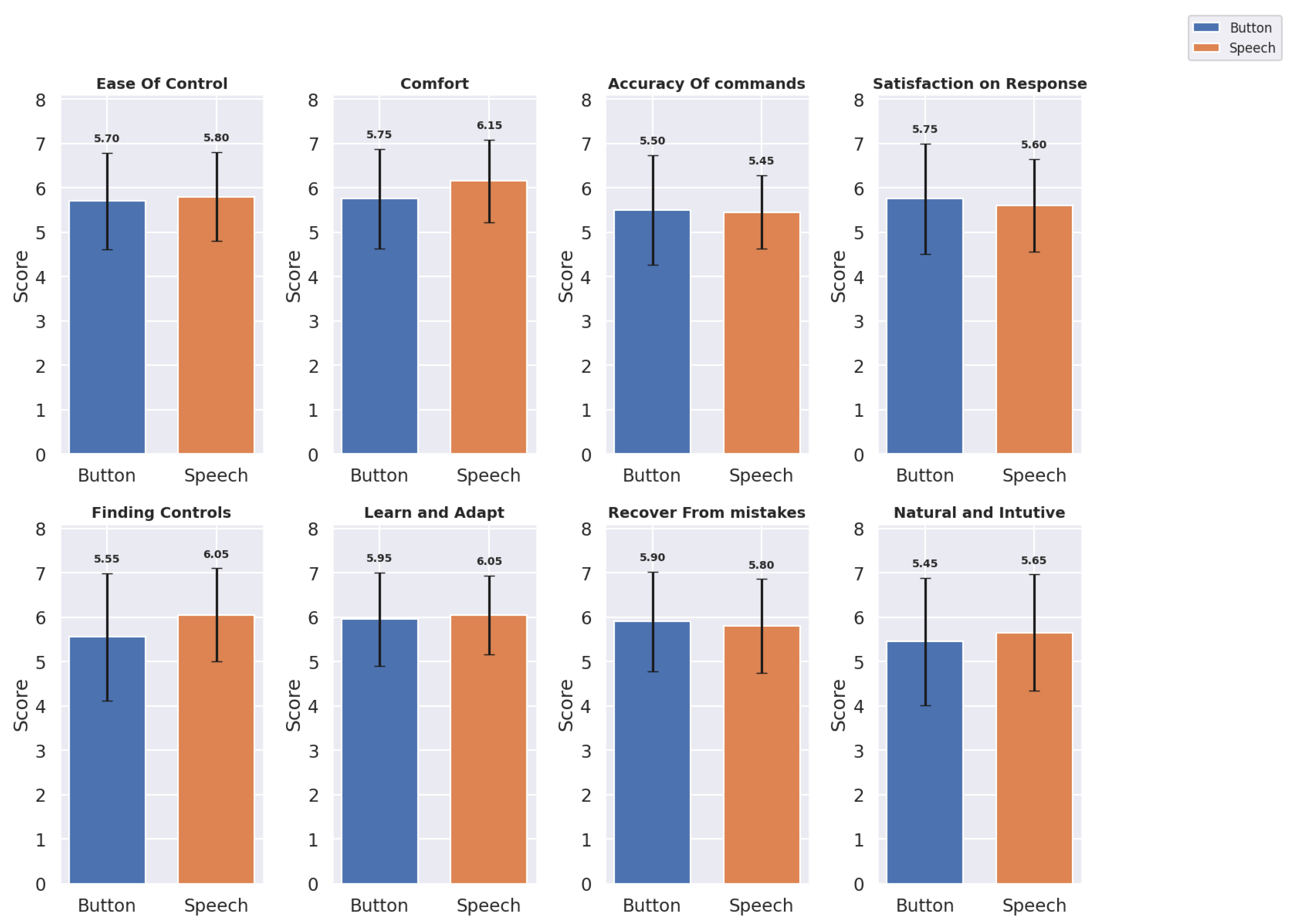

The usability metrics were evaluated across eight domains for both Button and Speech interfaces:

Ease of Control, Comfort, Accuracy of Commands, Satisfaction with Response, Finding Controls, Learning and Adapting, Recover from Mistakes, and Natural and Intuitive Use. Mean scores (

M) and standard deviations (

) provide insights into user experiences with each interface. The

Table 2 shows the Mean and Standard Deviation of the Button and Speech Interface for each usability metric and

Figure 6 shows a bar graph of the same.

Based on the updated usability metrics, we observe slight variations between Button and Speech interfaces across several dimensions:

For Ease of Control, Speech scored marginally higher () compared to Button (), indicating a slight preference for speech-based control. The Comfort ratings also favored the Speech interface () over Button (), suggesting that users found voice commands less physically and mentally demanding. For Accuracy of Commands, Button performed slightly better () than Speech (). However, in terms of Satisfaction with Response, Speech received slightly lower ratings () compared to Button (). Speech was rated higher in Finding Controls () and Learn and Adapt (), indicating that users found the speech interface more intuitive for these aspects. However, Button scored slightly better on Recovering from Mistakes () compared to Speech (). For Natural and Intuitive Use, Speech scored slightly higher () than Button (), suggesting users found the Speech interface somewhat more natural and intuitive.

Overall, usability metrics indicate a nuanced user preference. While Buttons Panel excel in ease of control and finding controls, Speech provides more comfort and learnability, suggesting it is less physically taxing.

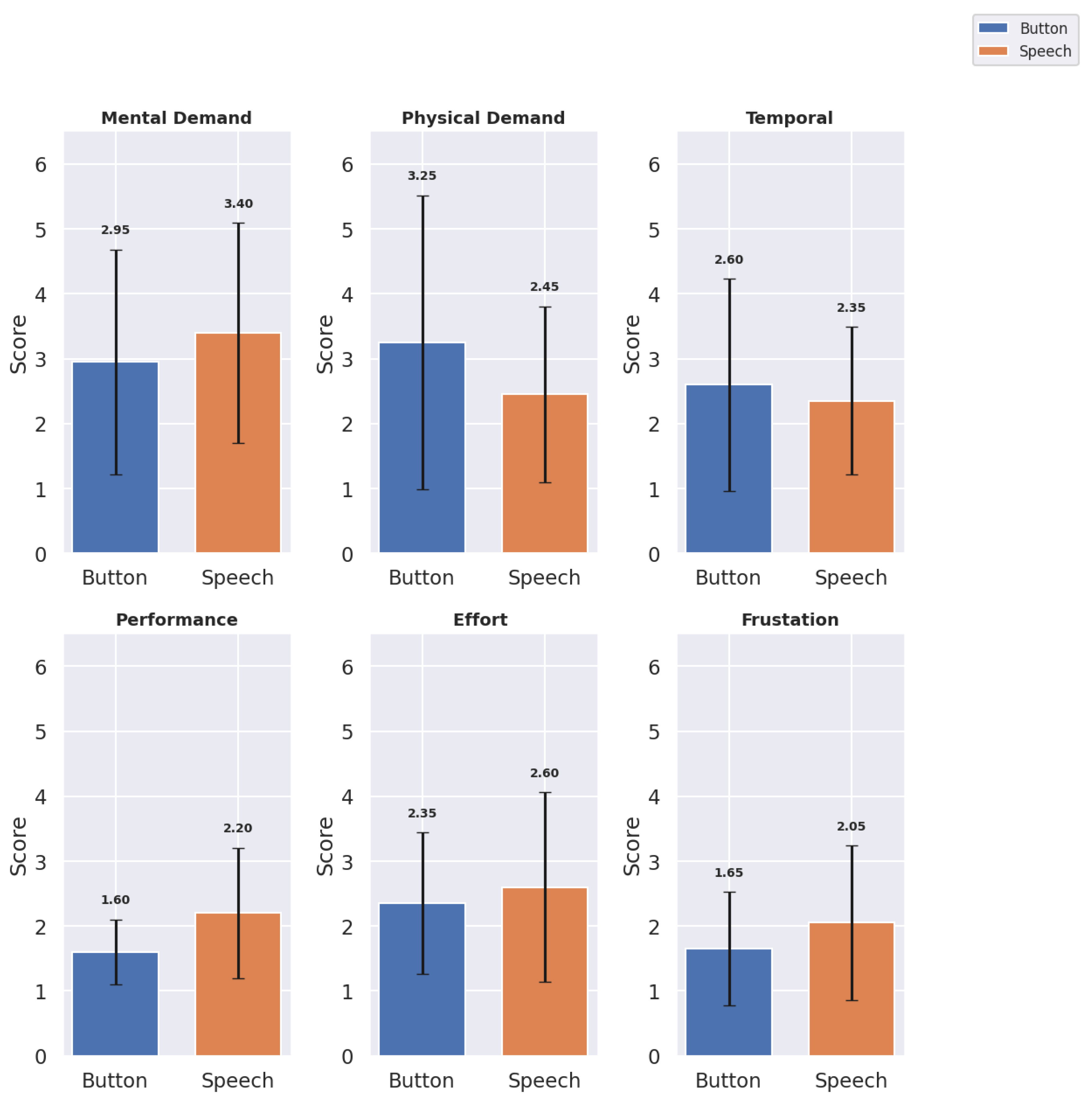

4.1.2. Cognitive Load Metrics

The cognitive load metrics were evaluated across six domains:

Mental Demand,

Physical Demand,

Temporal Demand,

Performance,

Effort, and

Frustration. Mean scores and standard deviations provide insight into the cognitive load associated with each interface (see

Table 3 and

Figure 7).

The Speech interface showed higher mental demand () than Button (), though it scored lower on physical demand (), suggesting that Speech may reduce physical effort but increase cognitive processing. Temporal Demand was rated similarly across interfaces, with Button at and Speech at , indicating that neither interface added significant time pressure. Button scored higher on affected performance (), reflecting user confidence with Button interactions (here performance is affected performance in NASA TLX cognitive load scoring where lower score indicates better performance. Higher score means bad performance). Speech required more effort (). Speech had a higher frustration score () compared to Button (), potentially due to inaccuracies in voice recognition.

4.1.3. Significance Test

A Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the data were not normally distributed. This study employs a within-subjects design, in which each participant used both interfaces (Button and Speech), providing related (or paired) measurements for each usability and cognitive load metric. Therefore, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was selected as it is ideal for paired or matched samples, where each participant serves as their own control, enabling effective comparison of score differences across the two interfaces. The W-statistic and p-values are represented in the

Table 4.

Usability Metrics: No statistically significant differences were observed in usability metrics between the Button and Speech interfaces, as all comparisons yielded p-values greater than 0.05. The test revealed no statistically significant differences between Button and Speech interfaces across most usability metrics, including Ease of Control (, ), Comfort (, ), Accuracy of Commands (, ), and Satisfaction on Response (, ). However, Finding Controls approached significance (, ), suggesting a trend in which users might have found control features easier to locate on one interface over the other. Other metrics, including Learn and Adapt (, ), Recover from Mistakes (, ), and Natural and Intuitive Use (, ), also showed no significant differences, indicating comparable ease in learning and adapting, error recovery, and intuitiveness between the interfaces.

Cognitive Load Metrics: The Performance metric showed a statistically significant difference between the Button and Speech interfaces (, ), suggesting a notable variation in cognitive load associated with performance across the two interfaces. Additionally, Physical Demand and Frustration demonstrated marginally non-significant p-values ( for Physical Demand and for Frustration), indicating a trend approaching toward a significance but not exactly statistically significant.

4.2. Qualitative Results

The qualitative analysis of user feedback on the speech interface was done by codes and themes where codes represent more granular detail while theme present overall category that code belongs to.

Table 5(Qp) and

Table 6(Qn) show some distinct positive and negative remarks from participants respectively.

Many participants highlighted the speech interface’s ease of use, specifically noting its capacity to simplify tasks and reduce physical demands compared to button-based interaction. Qp1, Qp2, Qp9 are some examples of those instances. Responsiveness was another aspect that was commented on on multiple instances (Qp1, Qp9). Participants also stated its ease of use through Qp4, Qp5, Qp6. Some also commented about ease of finding controls and commands using speech which proved sometimes difficult with button (Qp8). Many also commented about workflow efficiency, and natural flow of things using speech interface (Qp10, Qp11).

There were negative aspects of the speech as well, mostly due to inaccuracy for speech recognition ( Qn1, Qn2, Qn3) and overall accuracy (Qn4) leading to bad user experience. Primary reason behind this was varying accents and pitch of the voice, results being misinterpretation of full or half sentences, leading to wrong results. Many commented on overall task limitation in the speech interface (Qn4, Qn6, Qn7) stating that many aspect of whole setup is manual work like placing the dental implant. It is also inline with expectation for complete hands free interaction with speech, like in Qn6, where expectation was manual placement of dental implant to be done by speech and like in Qn5 where there was suggestion that no hand controller button to be used for speech activation, thus automating the whole processes.

5. Discussion

The described speech interface designed for changing tools and asking questions in medical VR applications demonstrated comparable performance to traditional button-panel interfaces in task completion metrics. Participants successfully completed an equal number of tasks with both interfaces, showing speech interfaces as a viable alternative to button-based methods. This aligns with prior research on single-word voice commands by [

31], where medical experts rated speech modalities as satisfactory, useful, natural, and accurate. Comparable results were observed in metrics like ease of control, comfort, and intuitiveness, further validating the speech-based system’s usability and its potential for broad application in dynamic medical environments. Systems that incorporate conversational fidelity and intent recognition has shown positive results in medical scenarios with speech being a effective medium in VR for medical training and diagnosis [

13,

14,

32]). This study proves similar technology can be extended to being as assistant in surgical scenarios providing realism through natural language, adaptivity, ease of control, comfort, finding control and less physical effort through objective and subjective results. The use of speech not only improves interaction in many key areas but also enables independent work. These results highlight the potential of speech-based systems to improve user interaction in medical VR, making them more effective and user-friendly in completing tasks. Another reason for relatively good score across various usability and cognitive load metrics was reduced latency, with results almost in real time which was not observed in prior studies [

36,

37]. This system also enabled users or developers to make easy configurations where number of commands, feedback and answers can be personalized. Reduced physical load and effort were also reported by similar studies [

15,

32], that dealt with physical elements in VR like keyboard, manual data entry etc. A novel finding in this research was the improved ease of finding controls with speech interfaces, supported by the "finding control" metric and open-ended responses, addressing a gap not explored in previous studies. This functional parity suggests that speech interfaces could serve as viable alternatives to button panels in similar contexts, particularly in terms of usability.

Participants reported slightly higher cognitive load with the speech interface, though the difference was statistically insignificant. Qualitative results suggest this increased cognitive load was primarily due to mental demand, which contrasts with past studies [

13,

15] where speech interfaces were associated with reduced cognitive effort. The higher mental demand in this study stemmed from small inaccuracies in command recognition which was commented on in qualitative results. When an unintended tool was activated, participants had to issue two additional commands, one to disable the incorrect tool and another to activate the correct one. In contrast, the button panel allowed users to simply reselect the desired tool, minimizing mental demand.

An anticipated aspect of the speech interface was the ability to automate physical activities within VR (Qn6, Qn8, Qn9 in

Table 6), such as picking up dental implants and placing them in jaws, as well as answering commands like "is the placement accurate or not" through a "Question Answering" feature. Participants also recommended adding conversational elements to understand, such as polite expressions ("Thank you," "Please"), to make interactions more natural and human like, akin to modern voice assistants like Alexa or ChatGPT.

5.1. Future Work

In further studies, a broader emphasis can be given to training examples in order to utilize diverse accents and dialects. Even small inaccuracies may lead to a lower user experience in real time interaction which was observed and noted in the experiments. Aspects such as accents, medical verbatim and dialects supporting these can be taken into consideration while training the speech-to-text model.

It was seen that the participants were often confused about which controls were automated under the speech. With the emergence and familiarity with LLM-based services such as ChatGPT and home automation speech assistants, it was anticipated that the speech assistant in this study would support a diverse range of actions. However, even after their introduction and demonstration of the use case, the interface did not fully meet these expectations, highlighting areas for further development to align with advancements in similar technologies. This can be achieved by adding more training examples and leveraging LLMs to recognize the actions in a more intelligent manner. Light-weight LLMs can be applied with reduced latency. For answering in questions, advanced techniques like RAGs (Retrieval Augmented Generation) can be used to generate more robust answers. Further, there were expectations like picking of the dental implant looking at implant positioning, and showing the accuracy of placement points. The anticipation from the speech interface was for it to function as a more intelligent system, not only controlling objects within medical VR scenarios but also extracting and providing relevant information from the interface to enhance decision-making and interactivity. Furthermore, incorporating conversational elements such as greetings and medically appropriate phrases can enhance the naturalness and interactivity of the system.

A multimodal approach combining speech and button interfaces on screen could reduce cognitive load and improve performance by mitigating some negative aspect of speech like Task limitations. Although the present study focused on comparing the speech interface to a button-based interface, integrating the two could leverage the strengths of both, minimizing cognitive demand. A similar conclusion was drawn by [

31], who suggested that combining modalities enhances usability and overall interaction efficiency. Other modalities such as gaze tracking further enables reducing cognitive load, as the target of an action could be determined from the user’s gaze direction. Gestures can also be an effective addition. For example, inaccuracies can be easily undone with a wave of the hand.

6. Conclusion

The development of the speech interface in this study prioritized considerations of human-computer interaction metrics over purely enhancing machine learning metrics. Although minor challenges persists, this study provided us with various insights in terms of usability and cognitive load along with different opinions, experiences, and feedback of using speech interfaces as a assistant in surgical scenarios. Our study proves the naturalness of using speech in VR and highlights key points using which it can be further developed.

Intelligent speech interfaces not only enhances interaction within VR but also acts as an medium to operate independently. Looking forward, further refinements in speech recognition accuracy, integration with lightweight and fast language models, and multimodal approaches are expected to significantly enhance user experience and promote advancements in medical VR applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N., J.K., and R.R.; methodology, M.N.; software, M.N.; validation, M.N.; formal analysis, M.N.; investigation, M.N.; resources, R.R.; data curation, M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.N., J.K., and R.R.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, J.K. and R.R.; project administration, R.R.; funding acquisition, R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Council of Finland grant number 345448 and Business Finland grant number 80/31/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to nature of the experimental tasks and the participant population.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected during the study are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of TAUCHI Research Center for their support in the practical experiment arrangements. We would also like to thank Planmeca Oy for providing software and the 3D skull models.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR |

Augmented reality |

| BERT |

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| DNN |

Deep neural networks |

| LLM |

Large language model |

| LUIS |

Azure language understanding |

| NLP |

Natural language processing |

| NLU |

Natural language understanding |

| QA |

Quality assurance |

| STT |

Speech-to-text |

| TLX |

Task load index |

| TTS |

Text-to-speech |

| VR |

Virtual reality |

| VSP |

Virtual standardized patient |

| XR |

Extended reality |

References

- Reitinger, B.; Bornik, A.; Beichel, R.; Schmalstieg, D. Liver surgery planning using virtual reality. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 2006, 26, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Jayender, J.; Bhagavatula, S.K.; Shyn, P.B.; Pieper, S.; Kapur, T.; Lasso, A.; Fichtinger, G. An immersive virtual reality environment for diagnostic imaging. Journal of Medical Robotics Research 2016, 1, 1640003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajtchuk, R.; Satava, R.M. Medical applications of virtual reality. Communications of the ACM 1997, 40, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kiiveri, M.; Rantala, J.; Raisamo, R. Evaluation of haptic virtual reality user interfaces for medical marking on 3D models. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2021, 147, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, J.; Li, Z.; Raisamo, R. Expert Evaluation of Haptic Virtual Reality User Interfaces for Medical Landmarking. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts. ACM, CHI ’22. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantamaa, H.R.; Kangas, J.; Jordan, M.; Mehtonen, H.; Mäkelä, J.; Ronkainen, K.; Turunen, M.; Sundqvist, O.; Syrjä, I.; Järnstedt, J.; et al. Evaluation of virtual handles for dental implant manipulation in virtual reality implant planning procedure. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 2022, 17, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, J.; Järnstedt, J.; Ronkainen, K.; Mäkelä, J.; Mehtonen, H.; Huuskonen, P.; Raisamo, R. Towards the Emergence of the Medical Metaverse: A Pilot Study on Shared Virtual Reality for Orthognathic–Surgical Planning. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtonen, H.; Järnstedt, J.; Kangas, J.; Kumar, S.; Rinta-Kiikka, I.; Raisamo, R. Evaluation of properties and usability of virtual reality interaction techniques in craniomaxillofacial computer-assisted surgical simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 35th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference. [CrossRef]

- Bueckle, A.; Buehling, K.; Shih, P.C.; Börner, K. 3D virtual reality vs. 2D desktop registration user interface comparison. PloS one 2021, 16, e0258103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Suh, G.; Kim, S.H.; Yang, H.J.; Lee, G.; Kim, S. Effect of Auto-Erased Sketch Cue in Multiuser Surgical Planning Virtual Reality Collaboration System. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 123565–123576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, A.; McKenzie, B. Evaluating the effectiveness of spatial memory in 2D and 3D physical and virtual environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, 2002, pp. 203–210.

- Fernandez, J.A.V.; Lee, J.J.; Vacca, S.A.S.; Magana, A.; Pesam, R.; Benes, B.; Popescu, V. 2024; arXiv:cs.HC/2402.15083].

- Ng, H.W.; Koh, A.; Foong, A.; Ong, J.; Tan, J.H.; Khoo, E.T.; Liu, G. Real-time spoken language understanding for orthopedic clinical training in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education. Springer; 2022; pp. 640–646. [Google Scholar]

- Maicher, K.; Stiff, A.; Scholl, M.; White, M.; Fosler-Lussier, E.; Schuler, W.; Serai, P.; Sunder, V.; Forrestal, H.; Mendella, L.; et al. 2. Artificial intelligence in virtual standardized patients: Combining natural language understanding and rule based dialogue management to improve conversational fidelity. Medical Teacher, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prange, A.; Barz, M.; Sonntag, D. Speech-based medical decision support in vr using a deep neural network. In Proceedings of the IJCAI; 2017; pp. 5241–5242. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, J.L.; Taekman, J.M.; Dev, P.; Danforth, D.R.; Mohan, D.; Kman, N.; Crichlow, A.; Bond, W.F.; Riker, S.; Lemheney, A.; et al. Using virtual reality simulation environments to assess competence for emergency medicine learners. Academic Emergency Medicine 2018, 25, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbala, M.K.; Lingolu, M.S.S. Conversational AI and Chatbots: Enhancing User Experience on Websites. American Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2024, 11, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. 2017.

- Kenton, J.D.M.W.C.; Toutanova, L.K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of naacL-HLT.

- Trivedi, A.; Pant, N.; Shah, P.; Sonik, S.; Agrawal, S. Speech to text and text to speech recognition systems-Areview. IOSR J. Comput. Eng 2018, 20, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Kader, S.A.; Woods, J.C. Survey on chatbot design techniques in speech conversation systems. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2015, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, S.; Naikwadi, Z.; Akole, A.; Darshankar, P. Enhancing college chat bot assistant with the help of richer human computer interaction and speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC). IEEE; 2020; pp. 427–433. [Google Scholar]

- Inupakutika, D.; Nadim, M.; Gunnam, G.R.; Kaghyan, S.; Akopian, D.; Chalela, P.; Ramirez, A.G. Integration of NLP and speech-to-text applications with chatbots. Electronic Imaging 2021, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.S.; Jorge, J.A. Extending medical interfaces towards virtual reality and augmented reality. Annals of Medicine 2019, 51, 29–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, E.; Wu, L.; Liao, W. Application of VR and 3D printing in liver reconstruction. Annals of Translational Medicine 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huettl, F.; Saalfeld, P.; Hansen, C.; Preim, B.; Poplawski, A.; Kneist, W.; Lang, H.; Huber, T. Virtual reality and 3D printing improve preoperative visualization of 3D liver reconstructions—results from a preclinical comparison of presentation modalities and user’s preference. Annals of translational medicine 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, K.L.; Jegede, V.; Mann, D.S.; Llerena, P.; Wu, R.; Estephan, L.; Kumar, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Banoub, R.; Keith, S.W.; et al. A Randomized Pilot Trial of Virtual Reality Surgical Planning for Head and Neck Oncologic Resection. The Laryngoscope 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isikay, I.; Cekic, E.; Baylarov, B.; Tunc, O.; Hanalioglu, S. Narrative review of patient-specific 3D visualization and reality technologies in skull base neurosurgery: enhancements in surgical training, planning, and navigation. Frontiers in Surgery 2024, 11, 1427844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantamaa, H.R.; Kangas, J.; Kumar, S.K.; Mehtonen, H.; Järnstedt, J.; Raisamo, R. Comparison of a vr stylus with a controller, hand tracking, and a mouse for object manipulation and medical marking tasks in virtual reality. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamilla, M.A.; Barnouin, C.; Moreau, R.; Zara, F.; Jaillet, F.; Redarce, H.T.; Coury, F. A Virtual Reality and haptic simulator for ultrasound-guided needle insertion. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics 2022, 4, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantamaa, H.R.; Kangas, J.; Jordan, M.; Mehtonen, H.; Mäkelä, J.; Ronkainen, K.; Turunen, M.; Sundqvist, O.; Syrjä, I.; Järnstedt, J.; et al. Evaluation of voice commands for mode change in virtual reality implant planning procedure. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 2022, 17, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Chan, M.; Uribe-Quevedo, A.; Kapralos, B.; Jaimes, N.; Dubrowski, A. Prototyping virtual reality interactions in medical simulation employing speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 22nd Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality (SVR). IEEE; 2020; pp. 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, K.; Gonzalez, G.; Sellen, A.; Penney, G.; Varnavas, A.; Mentis, H.; Criminisi, A.; Corish, R.; Rouncefield, M.; Dastur, N.; et al. Touchless interaction in surgery. Communications of the ACM 2014, 57, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Akkil, D.; Raisamo, R. Gaze-based kinaesthetic interaction for virtual reality. Interacting with Computers 2020, 32, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkolainen, I.; Farooq, A.; Kangas, J.; Hakulinen, J.; Rantala, J.; Turunen, M.; Raisamo, R. Technologies for multimodal interaction in extended reality—a scoping review. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2021, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombeck, J.; Voigt, H.; Lawonn, K. Voice user interfaces for effortless navigation in medical virtual reality environments. Computers & Graphics 2024, 124, 104069. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Cai, Y.; Wang, R.; Ding, S.; Tang, Y.; Hansen, P.; Sun, L. Supporting text entry in virtual reality with large language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR). IEEE; 2024; pp. 524–534. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Pu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; et al. When large language models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities. World Wide Web 2024, 27, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Liu, N.; Deng, H.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Yin, D.; Du, M. Explainability for large language models: A survey. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2024, 15, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Heer, J. The effects of interactive latency on exploratory visual analysis. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 2014, 20, 2122–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent-Iglesias, D.; Serantes-Raposo, S.; Botana, I.L.R.; González-Vázquez, S.; Fernandez-Graña, P.M. IVAMED: Intelligent Virtual Assistant for Medical Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the SEPLN (Projects and Demonstrations); 2023; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, K.S. Fundamentals of Natural Language Processing. In Microsoft Azure AI Fundamentals Certification Companion: Guide to Prepare for the AI-900 Exam; Springer, 2023; pp. 119–180.

Figure 1.

System architecture of usage of NLP based speech system and its integration with VR environment.

Figure 1.

System architecture of usage of NLP based speech system and its integration with VR environment.

Figure 2.

The complete VR Setup from user’s point of view. The major components from left to right are the skull model. The X-Ray cross section monitor on top, speech logger next to skull model, button interface panel, implant tray and panel with list of tasks on top.

Figure 2.

The complete VR Setup from user’s point of view. The major components from left to right are the skull model. The X-Ray cross section monitor on top, speech logger next to skull model, button interface panel, implant tray and panel with list of tasks on top.

Figure 3.

Snapshots of the Speech Logger with different commands. The spoken text can be seen on top with activated tools under “Do you mean?” and question, answers under “Question Answering” section: (a) Switching on handles for precise positioning of dental implants, (b) Hiding dental implants, (c) Asking question about handles and getting answer at the bottom of the speech logger, and (d) Switching on X-Ray Flashlight.

Figure 3.

Snapshots of the Speech Logger with different commands. The spoken text can be seen on top with activated tools under “Do you mean?” and question, answers under “Question Answering” section: (a) Switching on handles for precise positioning of dental implants, (b) Hiding dental implants, (c) Asking question about handles and getting answer at the bottom of the speech logger, and (d) Switching on X-Ray Flashlight.

Figure 4.

(a) The button panel as the control interface. (b) The empty speech logger.

Figure 4.

(a) The button panel as the control interface. (b) The empty speech logger.

Figure 5.

Bar Graph for combined usability and cognitive load metrics

Figure 5.

Bar Graph for combined usability and cognitive load metrics

Figure 6.

Bar Graph showing Usability Metrics: Mean and Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces

Figure 6.

Bar Graph showing Usability Metrics: Mean and Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces

Figure 7.

Bar Graph showing Cognitive Load Metrics: Mean and Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces

Figure 7.

Bar Graph showing Cognitive Load Metrics: Mean and Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces

Table 1.

Summary of Total, Mean, and Standard Deviation of Usability and Cognitive Load for Button and Speech Interfaces.

Table 1.

Summary of Total, Mean, and Standard Deviation of Usability and Cognitive Load for Button and Speech Interfaces.

| |

Usability |

Cognitive Load |

| Mode |

Total |

Mean |

Std Dev |

Total |

Mean |

Std Dev |

| Button |

911 |

5.69 |

1.21 |

288 |

2.40 |

1.56 |

| Speech |

931 |

5.82 |

1.02 |

301 |

2.50 |

1.37 |

Table 2.

Usability Metrics: Mean ± Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces.

Table 2.

Usability Metrics: Mean ± Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces.

| Metric |

Button |

Speech |

| Ease of Control |

5.70 ± 1.08 |

5.80 ± 1.01 |

| Comfort |

5.75 ± 1.12 |

6.15 ± 0.93 |

| Accuracy of Commands |

5.50 ± 1.24 |

5.45 ± 0.83 |

| Satisfaction on Response |

5.75 ± 1.25 |

5.60 ± 1.05 |

| Finding Controls |

5.55 ± 1.43 |

6.05 ± 1.05 |

| Learn and Adapt |

5.95 ± 1.05 |

6.05 ± 0.89 |

| Recover from Mistakes |

5.90 ± 1.12 |

5.80 ± 1.06 |

| Natural and Intuitive |

5.45 ± 1.43 |

5.65 ± 1.31 |

Table 3.

Cognitive Load Metrics: Mean ± Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces.

Table 3.

Cognitive Load Metrics: Mean ± Standard Deviation for Button and Speech Interfaces.

| Metric |

Button |

Speech |

| Mental Demand |

2.95 ± 1.73 |

3.40 ± 1.70 |

| Physical Demand |

3.25 ± 2.27 |

2.45 ± 1.36 |

| Temporal Demand |

2.60 ± 1.64 |

2.35 ± 1.14 |

| Performance |

1.60 ± 0.50 |

2.20 ± 1.01 |

| Effort |

2.35 ± 1.09 |

2.60 ± 1.47 |

| Frustration |

1.65 ± 0.88 |

2.05 ± 1.19 |

Table 4.

Results of the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test for Usability and Cognitive Load Metrics for Button and Speech Interfaces.

Table 4.

Results of the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test for Usability and Cognitive Load Metrics for Button and Speech Interfaces.

| Metric Category |

Metric |

W-statistic |

p-value |

| Usability Metrics |

Ease of Control |

63.0 |

0.7879 |

| Comfort |

43.5 |

0.3368 |

| Accuracy of Commands |

30.0 |

0.7850 |

| Satisfaction on Response |

35.0 |

0.4389 |

| Finding Controls |

20.0 |

0.0638 |

| Learn and Adapt |

20.0 |

0.7551 |

| Recover from Mistakes |

40.5 |

0.7121 |

| Natural and Intuitive |

68.0 |

0.6798 |

| Cognitive Load Metrics |

Mental Demand |

29.5 |

0.2545 |

| Physical Demand |

11.5 |

0.0541 |

| Temporal Demand |

5.0 |

0.2356 |

| Performance |

9.0 |

0.0146 |

| Effort |

27.5 |

0.6094 |

| Frustration |

6.0 |

0.0845 |

Table 5.

Positive remarks from participants with Codes and Themes.

Table 5.

Positive remarks from participants with Codes and Themes.

| ID |

Quotes |

Codes |

Themes |

| Qp1 |

"It is very responsive and its ability to understand instructions in many ways makes it handy and accessible." |

Responsive, Flexible Instructions |

Ease of Use, Reduced Latency |

| Qp2 |

"The speech interface simplified tasks significantly since I didn’t have to press buttons some of which were difficult to reach." |

Avoids Button Pressing, Simplifies Tasks |

Task Simplification, Less physical |

| Qp3 |

"Great, even though I have used VR before it was hard for me to use the panel but the speech felt more natural." |

Natural Feeling, Panel Interaction Difficulties |

Natural Interaction, Usability |

| Qp4 |

"At first it was challenging, but after a few tasks, I got a good grasp and it felt like a compact, effective tool." |

Initial Difficulty, Improved Over Time |

Learning Curve, Adaptability |

| Qp5 |

"Easy to learn and work. It can be really useful for professionals." |

Easy to Learn, Professional Usefulness |

Learning Curve, Adaptability |

| Qp6 |

"Easier to learn and adapt to. Made the tasks easier. I didn’t have to press the buttons and some of the buttons are not easy to press." |

Avoids Button Pressing, Panel Interaction difficulties |

Learning Curve and Adaptability |

| Qp7 |

"The VR speech assistant was able to understand my questions at least 90% so that’s a plus." |

Accurate Understanding of Questions |

Speech Recognition Accuracy |

| Qp8 |

"Overall good, may improve speech recognition. I was able to visualize but still struggled to find handles, there were a lot of buttons in the panel displayed." |

Difficult to Find Buttons, Visualization Clarity |

Finding controls and Commands |

| Qp9 |

"It’s very responsive and its ability to understand the instruction in many ways. It’s handy in many ways." |

Responsive, Flexible Instructions |

Reduced Latency, Ease of Use |

| Qp10 |

"I could stay focused on the model without needing to stop and press buttons, which is crucial in a workflow setting." |

Workflow Continuity |

Workflow Efficiency |

| Qp11 |

"I think it is easier to stick with the flow using speech while working. I felt effortless and it might be very interesting for the dentists to play around with efficiency. I feel this speech interface might be an artificial assistant." |

Task Flow Continuity, Artificial Assistant Potential |

Natural Interaction, Task Flow |

Table 6.

Negative remarks from participants with Codes and Themes.

Table 6.

Negative remarks from participants with Codes and Themes.

| ID |

Quotes |

Codes |

Themes |

| Qn1 |

"My accent was not understood clearly. Sometimes I had to speak slowly so that it understands entirely." |

Struggles with Accent |

Speech Recognition Accuracy |

| Qn2 |

"It interpreted few words wrong maybe due to lower voice and accent." |

Misinterpreted Commands |

Speech Recognition Accuracy |

| Qn3 |

"It was difficult for the system to take in long sentences." |

Struggles with Long Commands |

Speech Recognition, Accuracy |

| Qn4 |

"Some commands are not interpreted correctly, limitation in the amount of tasks. The system responded identically to ’Hide implants’ and ’Show implants,’ showing a need for command differentiation." |

Incorrect Commands, Limited Tasks |

Overall Accuracy, Task Limitation |

| Qn5 |

"Automating the speech activation, similar to Siri or Alexa, could reduce the need for physical input, making the interface more hands-free." |

Automation Suggestion, Reduced Physical Input |

Automation, Hands-Free Design |

| Qn6 |

"The speech was good in total, but in some scenarios, manual intervention was required. So for completing the task by using speech interface alone was not achieved." |

Manual Intervention Needed |

Task Limitation |

| Qn7 |

"Including more command variations and adding common questions would make it feel more intuitive." |

Suggests Expanded Commands, Common Questions |

Task Limitation, Command Variation |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).