Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Isolation and Purifications of Phages

2.3. Infection Curves of the Phages

2.4. Phages Host Range Determination

2.5. Temperature Stability of the Phages

2.6. One Step Growth Curve

2.7. Cocktail Design

2.8. Infection Curves of the Cocktail

2.9. Inhibition Effect of Phages Against E. coli in Saline LB Broth (In Vitro)

2.10. Inhibition Effect of Phages Against E. coli in Lettuce (Challenge)

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Morphology Plates of the Phages

- WWS: wastewater sample

- NO: No observed

3.2. Phage Characterization

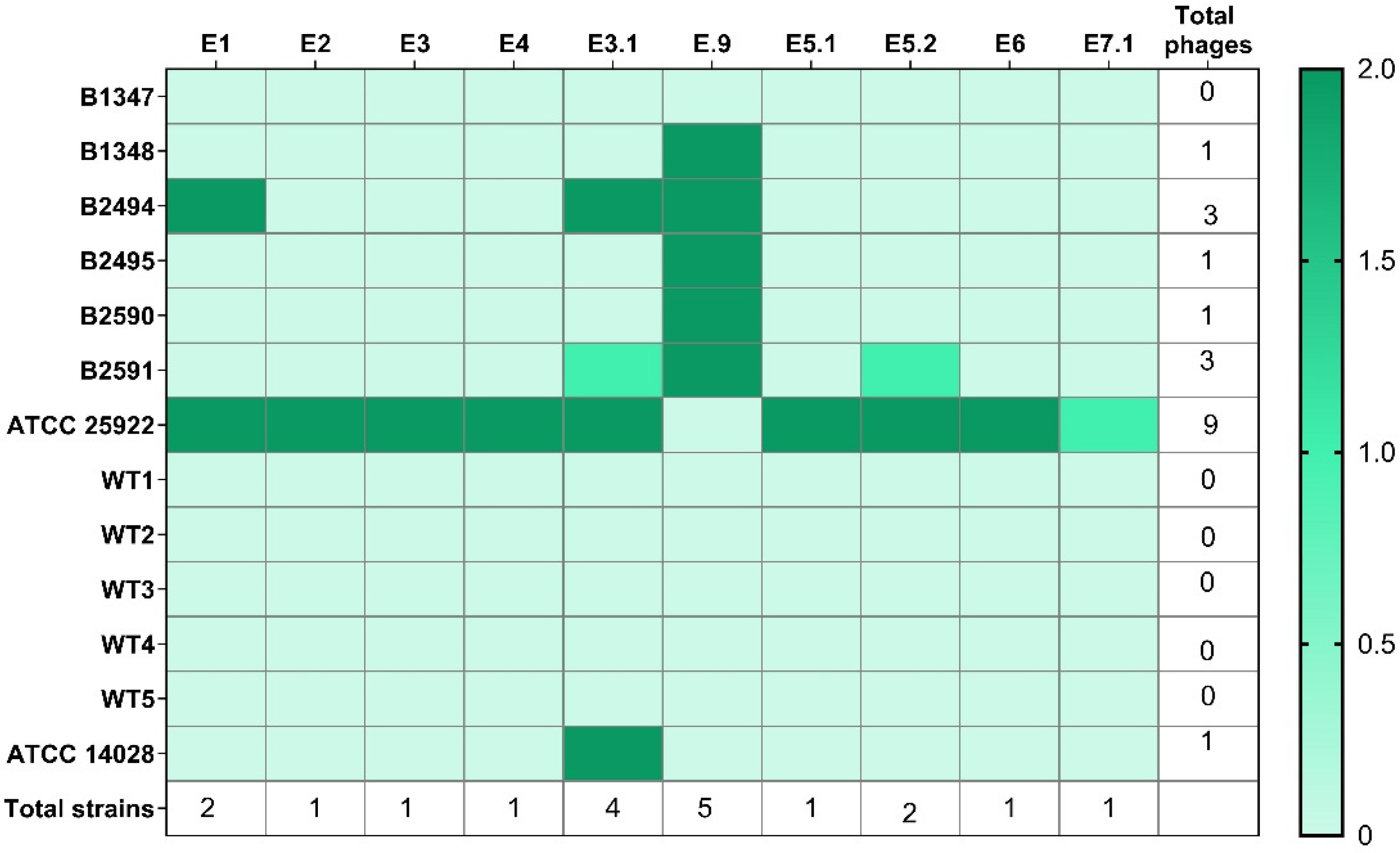

3.2.1. Host Range

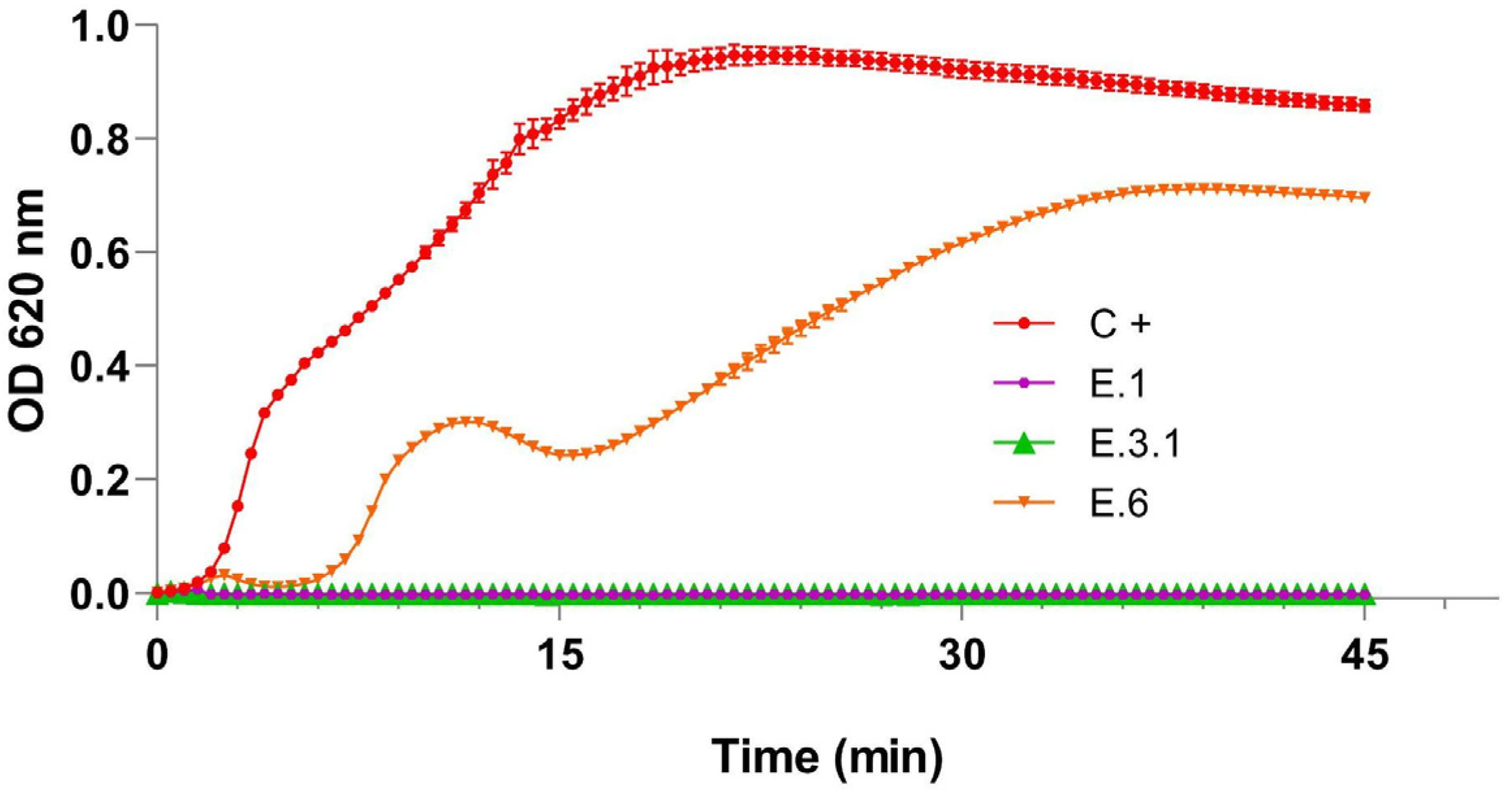

3.2.2. Infection Curves

3.3. Characterization of Cocktail Phages

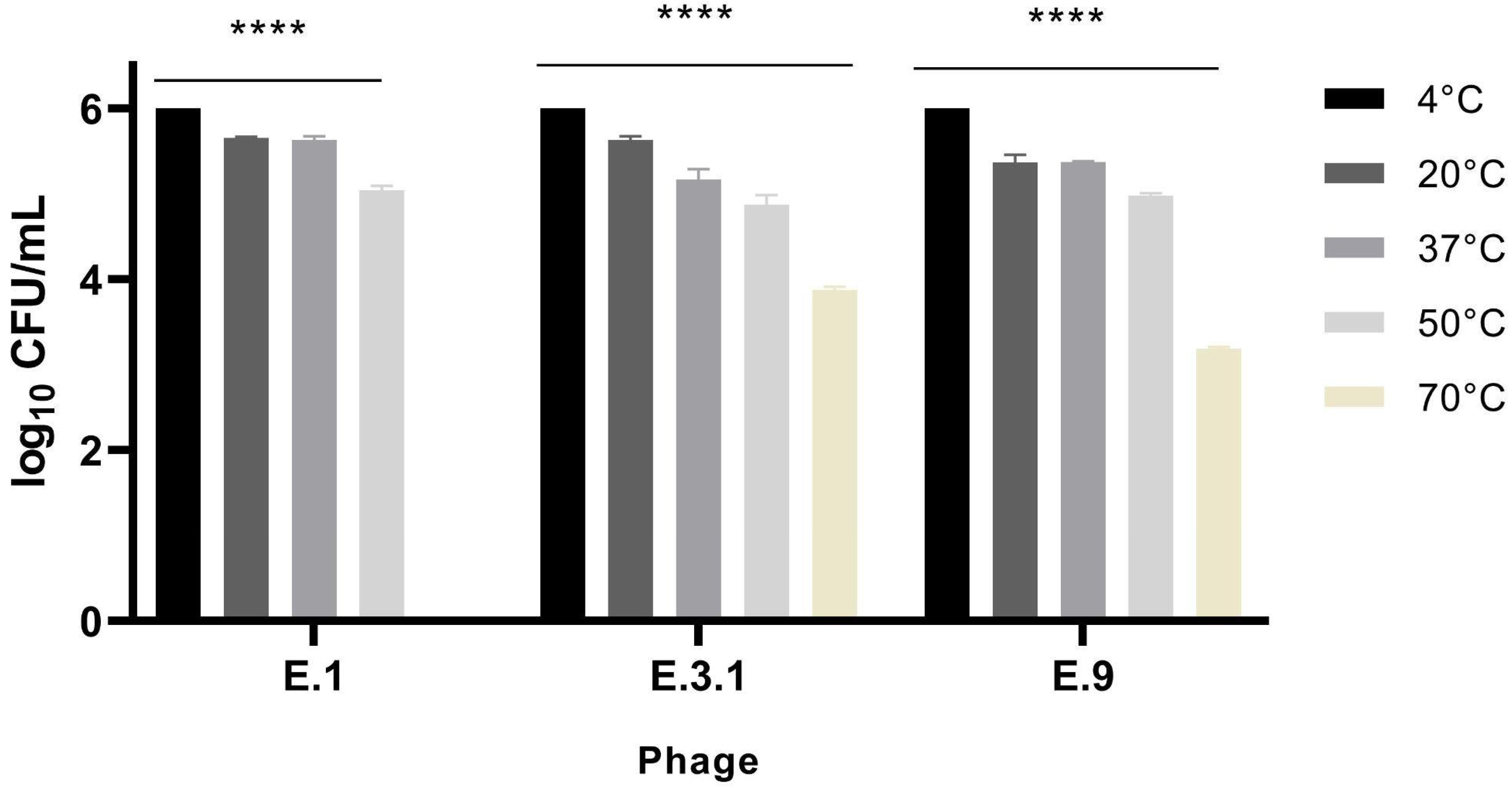

3.3.1. Phage Temperature Stability

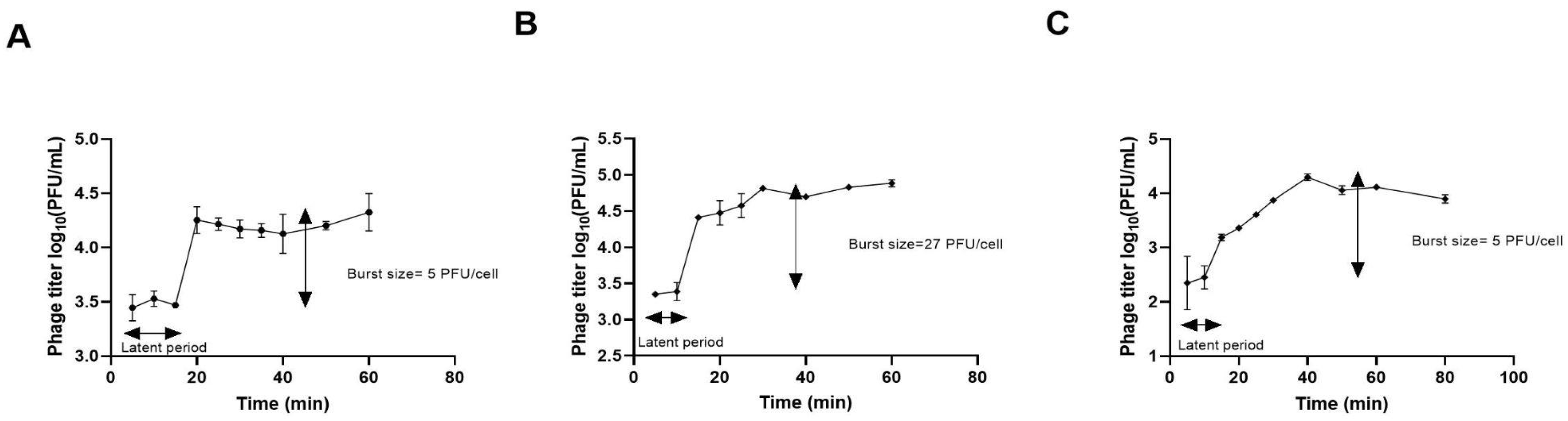

3.3.2. Phage Adsorption Rate and One Step Growth Curve

3.4. Application

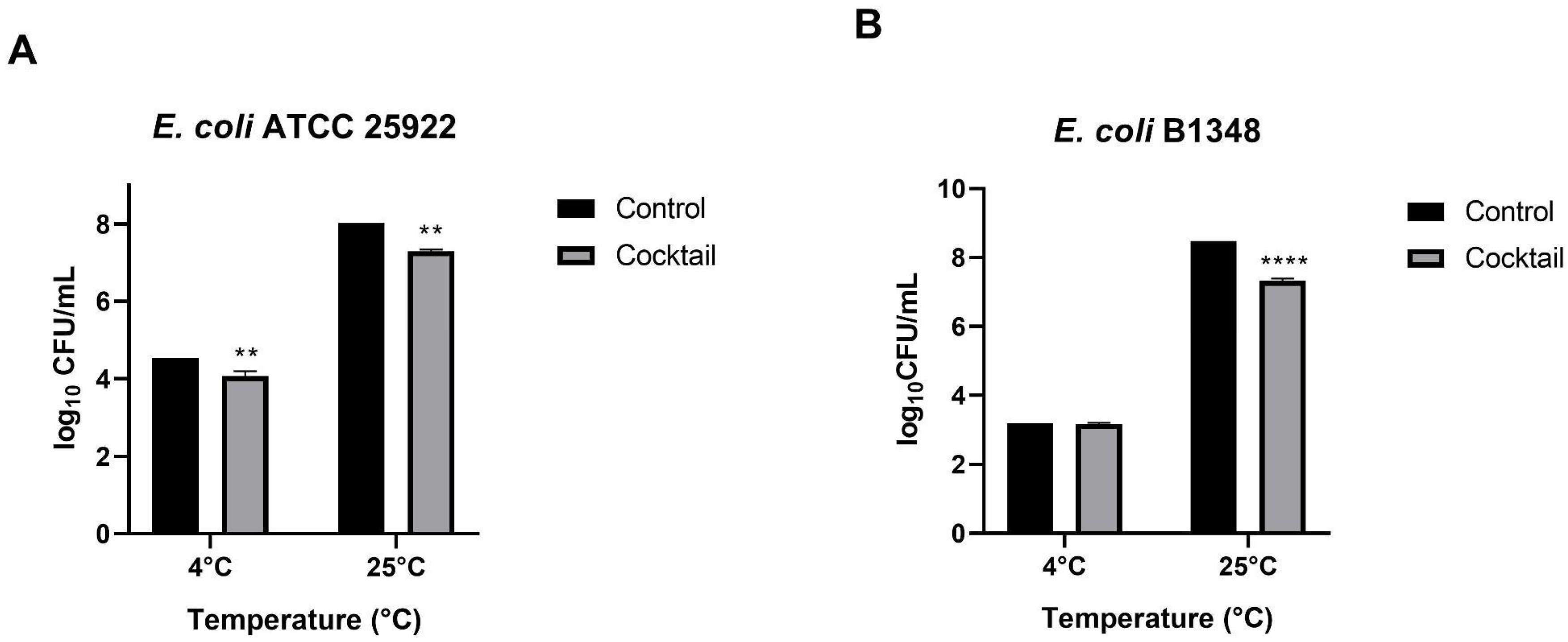

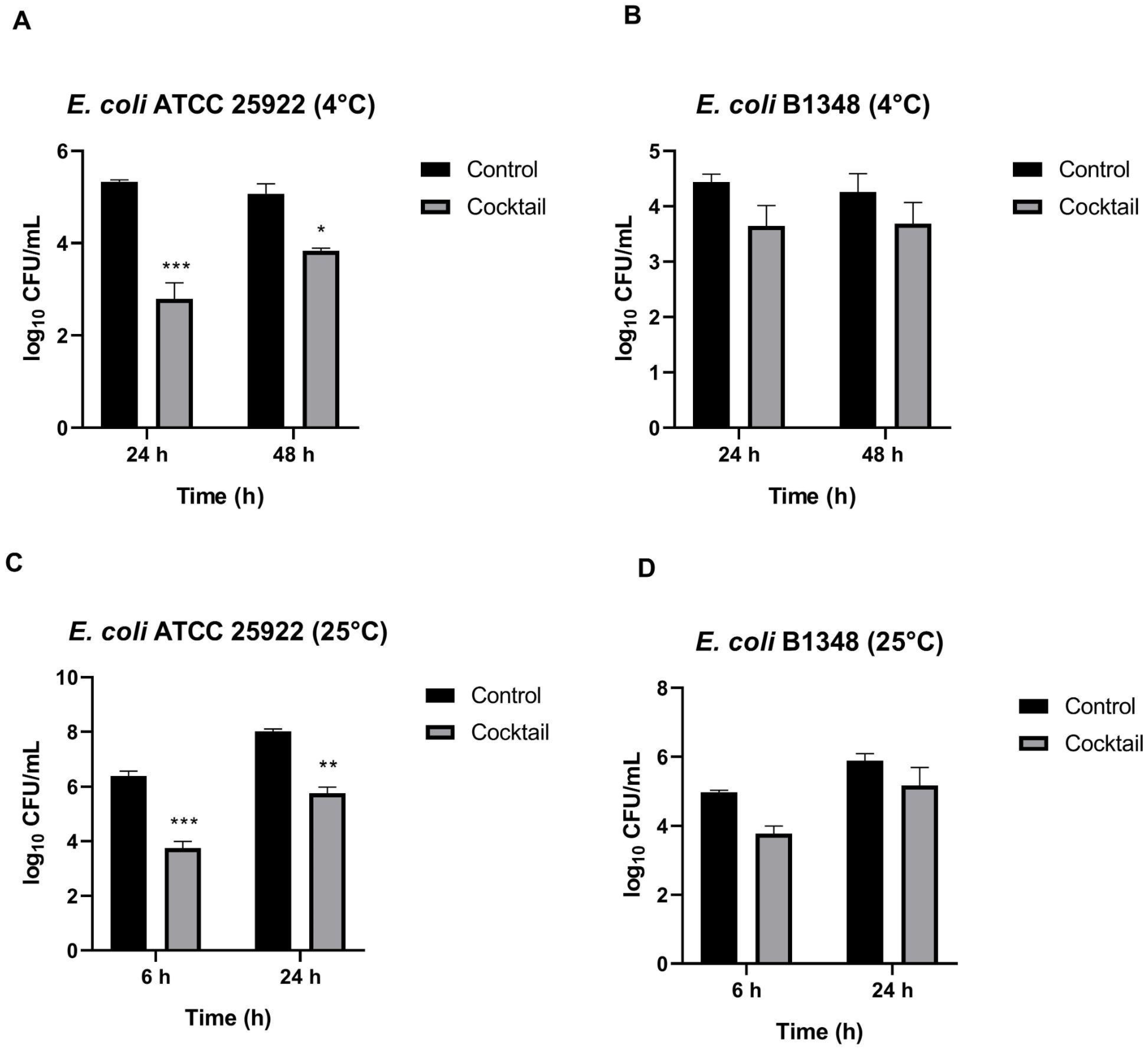

3.4.1. Inhibition Effect of the Phages Cocktail Against E. coli in Culture Medium

3.4.2. Inhibition Effect of Phages Against E. coli in Lettuce (Challenge)

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vila, J.; Sáez-López, E.; Johnson, J.R.; Römling, U.; Dobrindt, U.; Cantón, R.; Giske, C.G.; Naas, T.; Carattoli, A.; Martínez-Medina, M.; et al. Escherichia Coli: An Old Friend with New Tidings. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2016, 40, 437–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaper, J.B.; Nataro, J.P.; Mobley, H.L.T. Pathogenic Escherichia Coli. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004, 2, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, M.D.; Pires, S.M.; Black, R.E.; Caipo, M.; Crump, J.A.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Döpfer, D.; Fazil, A.; Fischer-Walker, C.L.; Hald, T.; et al. World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 22 Foodborne Bacterial, Protozoal, and Viral Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis. PLoS Med 2015, 12, e1001921. [Google Scholar]

- Mangieri, N.; Picozzi, C.; Cocuzzi, R.; Foschino, R. Evaluation of a Potential Bacteriophage Cocktail for the Control of Shiga-Toxin Producing Escherichia Coli in Food. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikram, A.; Tokman, J.I.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Phage Biocontrol Improves Food Safety by Significantly Reducing the Level and Prevalence of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 in Various Foods. J Food Prot 2020, 83, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puligundla, P.; Lim, S. Biocontrol Approaches against Escherichia Coli O157:H7 in Foods. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emencheta, S.; Attama, A.; Ezeibe, E.; Onuigbo, E. Isolation of Escherichia Coli Phages from Waste Waters. Hosts and Viruses 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajančkauskaitė, A.; Noreika, A.; Rutkienė, R.; Meškys, R.; Kaliniene, L. Low-Temperature Virus Vb_ecom_vr26 Shows Potential in Biocontrol of Stec O26:H11. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.B.; Perry, J.J.; Yousef, A.E. Developing and Optimizing Bacteriophage Treatment to Control Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia Coli on Fresh Produce. Int J Food Microbiol 2016, 236, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwarinde, B.O.; Ajose, D.J.; Abolarinwa, T.O.; Montso, P.K.; Du Preez, I.; Njom, H.A.; Ateba, C.N. Safety Properties of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Specific Bacteriophages: Recent Advances for Food Safety. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulakvelidze, A.; Alavidze, Z.; Morris, J. Bacteriophage Therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. The Future of Bacteriophage Biology. Nat Rev Genet 2003, 4, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, T.S.; Tessema, T.S. Isolation and Characterization of Lytic Bacteriophages from Various Sources in Addis Ababa against Antimicrobial-Resistant Diarrheagenic Escherichia Coli Strains and Evaluation of Their Therapeutic Potential. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruttin, A.; Brüssow, H. Human Volunteers Receiving Escherichia Coli Phage T4 Orally: A Safety Test of Phage Therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49, 2874–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, H.M.; Son, H.M.; Yi, H.P.S.; Sato, J.; Ngan, P.H.; Masuda, Y.; Honjoh, K. ichi; Miyamoto, T. Isolation, Characterization and Application of a Polyvalent Phage Capable of Controlling Salmonella and Escherichia Coli O157:H7 in Different Food Matrices. Food Research International 2020, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shebs-Maurine, E.L.; Giotto, F.M.; Laidler, S.T.; de Mello, A.S. Effects of Bacteriophages and Peroxyacetic Acid Applications on Beef Contaminated with Salmonella during Different Grinding Stages. Meat Sci 2021, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orquera, S.; Gölz, G.; Hertwig, S.; Hammerl, J.; Sparborth, D.; Joldic, A.; Alter, T. Control of Campylobacter Spp. and Yersinia Enterocolitica by Virulent Bacteriophages; 2012; Vol. 6;

- Lu, Y.T.; Ma, Y.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Wang, S. Characterization and Application of Bacteriophages for the Biocontrol of Shiga-Toxin Producing Escherichia Coli in Romaine Lettuce. Food Control 2022, 140, 109109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Patel, J.R.; Conway, W.S.; Ferguson, S.; Sulakvelidze, A. Effectiveness of Bacteriophages in Reducing Escherichia Coli O157:H7 on Fresh-Cut Cantaloupes and Lettuce †; 2009; Vol. 72;

- Soffer, N.; Woolston, J.; Li, M.; Das, C.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Preparation Lytic for Shigella Significantly Reduces Shigella Sonnei Contamination in Various Foods. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, S.; Huwyler, D.; Richard, S.; Loessner, M.J. Virulent Bacteriophage for Efficient Biocontrol of Listeria Monocytogenes in Ready-to-Eat Foods. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009, 75, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clokie, M.; Kropinski, A. Bacteriophages; Clokie, M.R.J. , Kropinski, A.M., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-58829-682-5. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Islam, M.S.; Yan, T.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, L.; Connerton, I.F.; Deng, K.; Li, J. Application of a Novel Phage VB_SalS-LPSTLL for the Biological Control of Salmonella in Foods. Food Research International 2021, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, C.; Chen, X.; Hu, L.; Wei, X.; Li, H.; Lin, W.; Jiang, A.; Feng, R.; et al. Characterizing the Biology of Lytic Bacteriophage VB_EaeM_φEap-3 Infecting Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacter Aerogenes. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Tao, Z.; Li, T.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, X. Isolation and Characterization of Novel Bacteriophage VB_KpP_HS106 for Klebsiella Pneumonia K2 and Applications in Foods. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viazis, S.; Akhtar, M.; Feirtag, J.; Diez-Gonzalez, F. Reduction of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Viability on Leafy Green Vegetables by Treatment with a Bacteriophage Mixture and Trans-Cinnamaldehyde. Food Microbiol 2011, 28, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti Maal, K.; Delfan, A.S.; Salmanizadeh, S. Isolation and Identification of Two Novel Escherichia Coli Bacteriophages and Their Application in Wastewater Treatment and Coliform’s Phage Therapy. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göller, P.C.; Elsener, T.; Lorgé, D.; Radulovic, N.; Bernardi, V.; Naumann, A.; Amri, N.; Khatchatourova, E.; Coutinho, F.H.; Loessner, M.J.; et al. Multi-Species Host Range of Staphylococcal Phages Isolated from Wastewater. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topka, G.; Bloch, S.; Nejman-Falenczyk, B.; Gasior, T.; Jurczak-Kurek, A.; Necel, A.; Dydecka, A.; Richert, M.; Wegrzyn, G.; Wegrzyn, A. Characterization of Bacteriophage VB-EcoS-95, Isolated from Urban Sewage and Revealing Extremely Rapid Lytic Development. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczak-Kurek, A.; Gasior, T.; Nejman-Faleńczyk, B.; Bloch, S.; Dydecka, A.; Topka, G.; Necel, A.; Jakubowska-Deredas, M.; Narajczyk, M.; Richert, M.; et al. Biodiversity of Bacteriophages: Morphological and Biological Properties of a Large Group of Phages Isolated from Urban Sewage. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomat, D.; Casabonne, C.; Aquili, V.; Balagué, C.; Quiberoni, A. Evaluation of a Novel Cocktail of Six Lytic Bacteriophages against Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli in Broth, Milk and Meat. Food Microbiol 2018, 76, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahdadi, M.; Safarirad, M.; Berizi, E.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Zare, M.; Derakhshan, Z.; Rajabi, S. A Systematic Review and Modeling of the Effect of Bacteriophages on Salmonella Spp. Reduction in Chicken Meat. Reduction in Chicken Meat. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, S.; Dunn, L.; Palombo, E. Phage Inhibition of Escherichia Coli in Ultrahigh-Temperature-Treated and Raw Milk. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2014, 10, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moye, Z.D.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Applications for Food Production and Processing. Viruses 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomat, D.; Casabonne, C.; Aquili, V.; Balagué, C.; Quiberoni, A. Evaluation of a Novel Cocktail of Six Lytic Bacteriophages against Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli in Broth, Milk and Meat. Food Microbiol 2018, 76, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameh, E.M.; Tyrrel, S.; Harris, J.A.; Pawlett, M.; Orlova, E. V.; Ignatiou, A.; Nocker, A. Lysis Performance of Bacteriophages with Different Plaque Sizes and Comparison of Lysis Kinetics After Simultaneous and Sequential Phage Addition. PHAGE: Therapy, Applications, and Research 2020, 1, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.D.; Parks, A.; Abuladze, T.; Li, M.; Woolston, J.; Magnone, J.; Senecal, A.; Kropinski, A.M.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Cocktail Significantly Reduces Escherichia Coli O157. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Nime, I.; Pan, F.; Wang, X. Isolation and Characterization of Phage ISTP3 for Bio-Control Application against Drug-Resistant Salmonella. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarirad, M.; Shahdadi, M.; Berizi, E.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Montaseri, M.; Derakhshan, Z. A Systematic Review and Modeling of the Effect of Bacteriophages on E. Coli O157:H7 Reduction in Vegetables. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.B.; Perry, J.J.; Yousef, A.E. Developing and Optimizing Bacteriophage Treatment to Control Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia Coli on Fresh Produce. Int J Food Microbiol 2016, 236, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudva, I.T.; Jelacic, S.; Tarr, P.I.; Youderian, P.; Hovde, C.J. Biocontrol of Escherichia Coli O157 with O157-Specific Bacteriophages; 1999; Vol. 65;

- Abuladze, T.; Li, M.; Menetrez, M.Y.; Dean, T.; Senecal, A.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophages Reduce Experimental Contamination of Hard Surfaces, Tomato, Spinach, Broccoli, and Ground Beef by Escherichia Coli O157:H7. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74, 6230–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moye, Z.D.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Applications for Food Production and Processing. Viruses 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phage | WWS (date) | Size (plaque/halo, cm) | Plaque turbidity | Regular border | Halo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E.3.1 | WWS 3 (29/06/2023) | 0,320 ± 0,02/NO | No | Yes | No |

| E.1 | WWS 4 (19/07/2023) | 0,333 ± 0,05/NO | No | Yes | No |

| E.2 | WWS 4 (19/07/2023) | 0,334 ± 0,07 / 0,892 ± 0,12 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| E.3 | WWS 4 (19/07/2023) | 0,337 ± 0,07 / 1,122 ± 0,19 | No | Yes | Yes |

| E.4 | WWS 4 (19/07/2023) | 0,353 ± 0,03 / 0,885 ± 0,09 | Yes | No | Yes |

| E.5.1 | WWS 5 (09/08/2023) | 0,165 ± 0,03 / 0,424 ± 0,08 | Yes | No | Yes |

| E.5.2 | WWS 5 (09/08/2023) | 0,574 ± 0,02 / 1,402 ± 0,09 | No | Yes | Yes |

| E.6 | WWS 6 (30/08/2023) | 0,193 ± 0,03/NO | Yes | Yes | No |

| E.7.1 | WWS 7 (22/09/2023) | 0,487 ± 0,06 / 1,223 ± 0,14 | No | Yes | Yes |

| E.9 | WWS 8: Pull de aguas | 0,155 ± 0,02/NO | No | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).