1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance has arisen as one of the most significant health challenges of our time [

1]. International organizations, such as EFSA and WHO, have emphasized the importance of a "One Health" approach to tackle this issue, which involves a holistic perspective that considers the interconnectedness between human, environmental, and animal settings in the emergence and transmission of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) bacteria and genes. In this context, the food production chain plays a crucial role in the dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to consumers [

2]. Factors such as the increasing elderly population and certain medical procedures have led to a higher incidence of low-virulence bacteria acting as opportunistic emerging pathogens. The role of food as a vehicle for AMR opportunistic pathogens is often underestimated, as their impact on healthy individuals is not immediately perceptible, yet they can pose a significant public health risk [

3]. Among these bacteria,

Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC) is a group of opportunistic pathogenic species frequently implicated in respiratory tract, urinary tract and soft tissue infections. Besides the pathogenic traits ECC isolates possess a wide range of antibiotic resistance mechanisms, both intrinsic and acquired, against first-line molecules such as penicillins, cephalosporins or quinolones and last resource antimicrobials such as colistin and carbapenems [

4,

5]. Previous studies have observed that fresh vegetables may act as reservoirs of antimicrobial and pathogenic isolates of the ECC, detecting isolates that carry ESBL, carbapenemase and

mcr genes as well as pathogenic traits [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Vegetables are typically consumed raw, which facilitates the introduction of these bacteria into the consumer's intestinal and skin microbiota [

10], highlighting their role in potential health impacts and emphasizing the need for effective control measures to prevent contamination. Fresh produce decontamination typically involves surface washing with water or aqueous solutions containing disinfectants such as sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) or peracetic acid [

11]. However, the use of these biocides often presents disadvantages, including the risk of cross-contamination through water [

12], sensory quality alterations, chemical residues such as organochlorine compounds, a negative environmental impact, and especially, the emergence and transmission of cross resistance mechanisms between biocides and antibiotic compounds [

13]. The development of strategies that effectively eliminate AMR and pathogenic bacteria from fresh produce whilst avoiding such disadvantages is crucial. Regarding this matter, the application of bacteriophages is presented as an interesting alternative treatment to decontaminate vegetable surfaces.

Bacteriophages are safe biotechnological agents that specifically target bacterial cells not being able to infect eukaryotic cells. Their ubiquity makes them available for easy and straightforward laboratory isolation from diverse sources such as soil or wastewater. A defining characteristic of these viruses is their host range specificity; most phages can only infect a narrow range of strains that are phylogenetically related. This specificity allows for targeted applications against undesired bacterial strains without affecting the surrounding microbiota. However, their specificity can sometimes pose challenges in designing phage-based disinfectants, as several phages must be combined into a cocktail to broaden their effect against a significant number of strains within a genus/species [

14]. While phage resistance has been documented, the co-evolutionary dynamics between phages and bacteria can enable phages to adapt and overcome bacterial resistance, maintaining their efficacy over time [

14,

15].

Phage-based products designed for disinfection in the food industry are directed against classic foodborne pathogens such as

Listeria,

E. coli, and

Campylobacter. However, their use in the European Union is limited due to the lack of a clear regulatory framework [

16]. The development of phage-based products to control the spread of opportunistic pathogens and/or antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such as ECC, remains yet an underexplored field. Thus, the aim of this work is to isolate and to characterize bacteriophages targeting ECC isolates and to evaluate the efficacy of phage applications to control fresh produce contamination.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain Collection

The study was designed to evaluate the biocontrol potential of phages against a collection of 24 strains belonging to the

Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC), isolated from vegetable samples which included

E. hormaechei (n=8),

E. ludwigii (n=8),

E. mori (n=4),

E. kobei (n=2) and

E. asburiae (n=1), that exhibited pathogenic traits and/or relevant antibiotic resistance profiles.

E. kobei AG07E, which was isolated from vegetable irrigation water, was selected as the target strain for phage isolation due to its public health relevance. This strain belonged to sequence type ST56, a lineage associated with clinical settings and harbored the

mcr-9 gene [

6].

E. kobei AG07E was subsequently used as the host strain for routine laboratory propagation of the bacteriophages. Additional strains belonging to

Citrobacter (n=11),

E. coli (n=12),

Cronobacter (n=6),

K. pneumoniae (n=3),

K. aerogenes (n=9) were also included in the study to establish the host range of the bacteriophages.

2.2. Bacteriophage Isolation and Propagation

Bacteriophage isolation was performed from sewage samples following the method described by Schwarz & Mathieu [

17]. Briefly, raw effluents were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 minutes and subsequently filtered through 0.22 µm pore-size nitrocellulose membranes (GVS, Italy). Equal volumes of the filtrates were inoculated into 2X TSB (Scharlab, Spain) supplemented with 2 mM CaCl₂, along with a 10 µL loop of a fresh culture of the host bacterium,

Enterobacter kobei AG07E, to enrich for phages targeting this strain. The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours with 50 rpm agitation. After the enrichment step, the effluents were centrifuged and filtered under the conditions described above.

Enriched filtrates were appropriately diluted and 100 µl were inoculated into TSB + 0.5% agar, along with 100 µl of an exponential-phase culture of the host strain (E. kobei AG07E), to isolate and purify the phages. Lysis plaques were collected and resuspended in 1 ml saline-magnesium (SM) buffer (Tris-HCl 0.05 M, NaCl 0.1 M, MgSO4 0.008 M, gelatine 0.01%, pH 7.5). Phages were propagated by adding the entire volume of the suspension to TSB supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2 along with 100 µl of an exponential-phase culture of the host strain. This process was repeated twice to ensure the purity of the bacteriophage.

Phage titration was carried out using the soft agar overlay technique with E. kobei AG07E serving as host and the results were expressed in PFU/ml.

2.3. Assessment of Phage Morphology Through Transmission-Electron Microscopy

Bacteriophage morphology was assessed through transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Viral particles were adsorbed in a carbon-copper grid through contact with 20 µl of a suspension of the bacteriophage in buffer SM for 20 minutes. The bacteriophages were stained with a 5 % phosphotungstic acid solution for 5 minutes. Samples were examined under TEM (JEM-1200EX, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV.

2.4. Host Range Determination

The host range was determined by spot test on TSA (Scharlab, Spain) plates supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2. Crude phage filtrates (10⁹ PFU/ml) were diluted 1:10 to reduce the lytic effect associated with endolysins in suspension. Subsequently, a 10 μl drop of the resulting phage suspension (10⁶ PFU/spot) was applied to a confluent lawn of study isolates, prepared from a 0.5 McFarland solution. Lytic activity was tested against different ECC species (n=23) and other Enterobacteriaceae isolates of Citrobacter (n=11), E. coli (n=12), Cronobacter (n=6), K. pneumoniae (n=3), and K. aerogenes (n=9).

Lysis was classified as confluent (+++) when the spot was entirely clear, semi confluent (++ and +) when some colonies inside a clear spot were observed, turbid spots and absent when no clearing was detected.

2.5. Assessment of Bacterial Growth Inhibition and Phage Stability Against Foodborne Stress Conditions

The phage's ability to inhibit the growth of the host strain was evaluated under standard medium conditions (TSB; pH 7 and 0.5 % NaCl) and food stress related conditions (pH 4-6 and 1-4 % NaCl) using BioTrac 4500 (SY-LAB), which monitors bacterial growth through periodic measures of electrical impedance changes of the culture medium.

Phages were inoculated at a concentration of 105 PFU/ml in 10 ml of TSB medium supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2 adjusted to pH and % NaCl conditions, along with 100 µl of a 0.5 McFarland suspension of the host strain (Enterobacter kobei AG07E). The growth control consisted of 10 ml of adjusted medium inoculated only with host strain. Tubes were incubated at 37ºC for 24 hours.

Bacterial growth inhibition due to phage presence was evaluated using the detection time registered by the BioTrac system. This detection time refers to the period required to measure a significant change in the electric signal (impedance) exceeding a 3.5% threshold which indicates the presence of viable bacteria. Each condition was assayed in triplicate.

2.6. Measurement of the Bactericidal Effect on a Food Matrix

Bactericidal effect of bacteriophages was evaluated on lettuce surface (Lactuca sativa var iceberg). Internal leaves of the lettuce were cut in 2.5 x 2.5 cm portions that were decontaminated under UV light for 30 minutes. 150 µl of a suspension of the host bacteria were spread over the surface to a final inoculum of ≈104 UFC per portion. Inoculated leaves were treated by immersion on a phage suspension in buffer SM to a MOI 1:1 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Additionally, two control groups were included: one untreated control and another one immersed in SM buffer without phage to assess the washing effect of the liquid.

Treated leaves were left to dry under laminar flow for 15 min and then homogenized with 10 ml of saline solution (0.85% NaCl). Appropriate dilutions were spread on MacConkey Agar to perform bacterial survivor count. Each condition was assayed at least in quintuplicate.

2.7. Whole Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using Norgen´s Bacteriophage DNA extraction kit with pre-DNAse I treatment and quantified using Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US). Viral genomes were sequenced using Illumina technology. Assembling of reads was carried out using the PATRIC web platform.

Functional annotation of the genomes was carried out using PHAROKKA [

18]. Genetic characteristics of the bacteriophages were studied using ResFinder (genepi.food.dtu.dk/resfinder) and CARD platform (card.mcmaster.ca/) for the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes and VirulenceFinder (cge.food.dtu.dk/services/VirulenceFinder/) for the detection of virulence genes. Matplotlib v X.X. [

19] to visualize the distribution of genes within phage genomes.

Taxonomic classification of the phages was carried out using whole genome blast against the NCBI virus database. Phylogenetic relationships of the phages’ genomes with their closest relatives were analyzed using VICTOR web service (victor.dsmz.de), a genome-based approach to study the phylogeny and classification of prokaryotic viruses [

20]. The analysis included pairwise nucleotide sequence comparisons, carried out using the Genome-BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) method [

21], following specific guidelines for these viruses [

20]. Intergenomic distances obtained from the analysis were used to construct a balanced minimum evolution tree, with branch support calculated via FASTME and SPR postprocessing [

22] for the formula D0. Branch support was based on 100 pseudo-bootstrap replicates. Midpoint rooting was applied to the trees [

23], which were subsequently visualized using the ggtree package [

24]

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS V.29.0.2.0 package. The normality and homoscedasticity of the variables were checked out using the Saphiro-Wilk and Levene's test, respectively. T-test U or Mann-Whitney test were appropriately used to compare detection time data on the phage stability assay. Data obtained from the lettuce assay was analysed through ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. Differences were statistically considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Morphological Characterization of the Bacteriophages

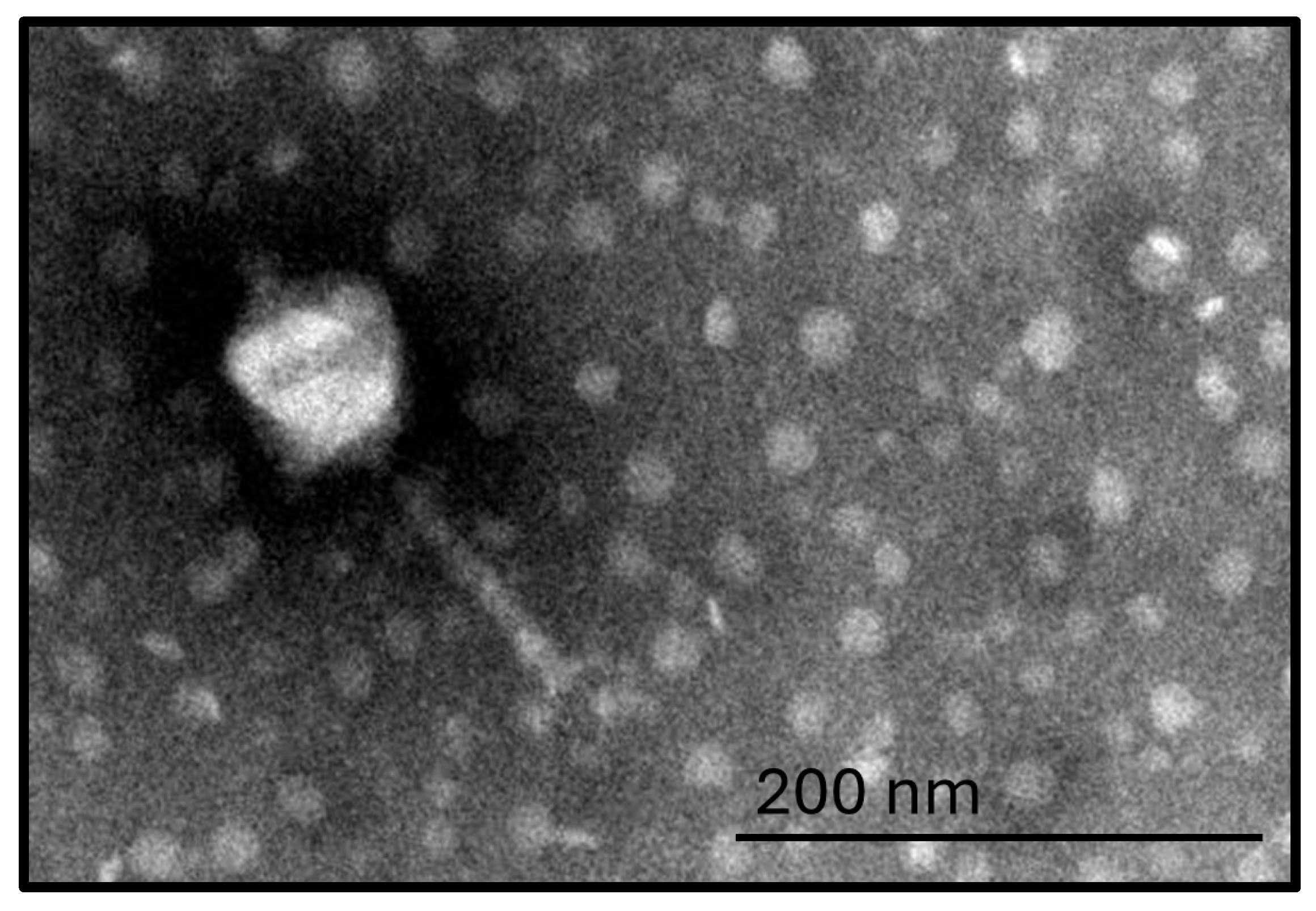

The processing of the sewage samples led to the isolation of bacteriophage FENT2 which exhibited lytic activity against the host strain E. kobei AG07E.

The FENT2 bacteriophage exhibited uniform morphology in TEM preparations, with icosahedral head (≈80 × 67 nm) and retractable tail (≈100 nm), consistent with the morphology of a Myovirus (

Figure 1).

3.2. Genetic Characteristics of FENT2

The genomic sequence of Seunavirus FENT2 is available in the NCBI Virus database under accession number PQ882504.

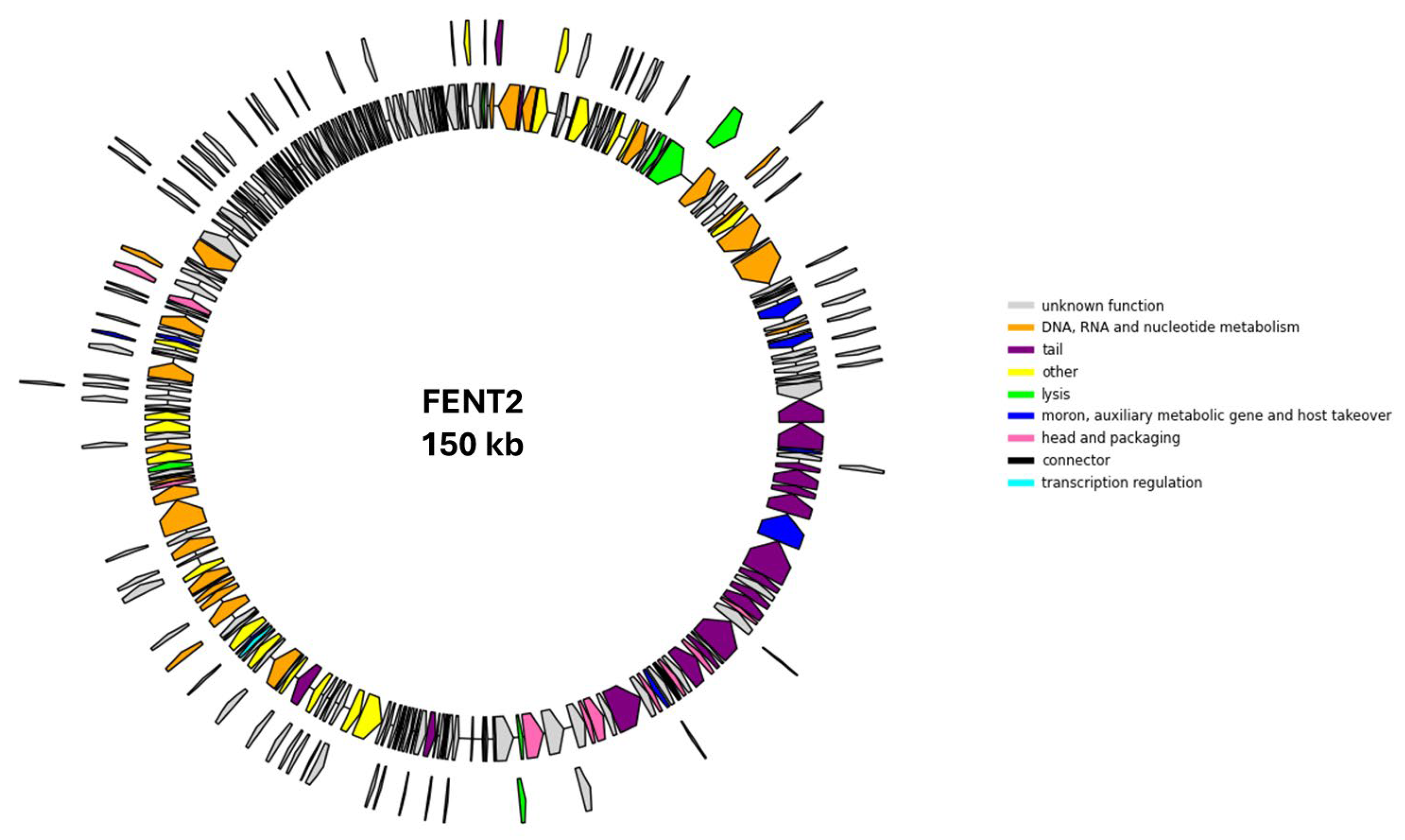

FENT2 was a DNA bacteriophage that carried a 150 kb genome with a 45% GC content which codified 306 CDS (90 with predicted function and 216 hypothetical proteins) and 24 tRNAs. No genes associated with the lysogenic life cycle, antimicrobial resistance, or virulence factors were detected in the FENT2 genome, as determined through analysis using the PHARokka, CARD, ResFinder, and VirulenceFinder databases.

Figure 2.

Functional categorization of the FENT2 genome. Functional categories include “DNA, RNA and nucleotide metabolism” (n=25), “head and packaging” (n=10), “tail” (n=19), “connector” (n=1), “moron auxiliary metabolic and host takeover” (n=9), “transcription regulation” (n=1), “other” (n=18) and “unknown proteins” (n=216).

Figure 2.

Functional categorization of the FENT2 genome. Functional categories include “DNA, RNA and nucleotide metabolism” (n=25), “head and packaging” (n=10), “tail” (n=19), “connector” (n=1), “moron auxiliary metabolic and host takeover” (n=9), “transcription regulation” (n=1), “other” (n=18) and “unknown proteins” (n=216).

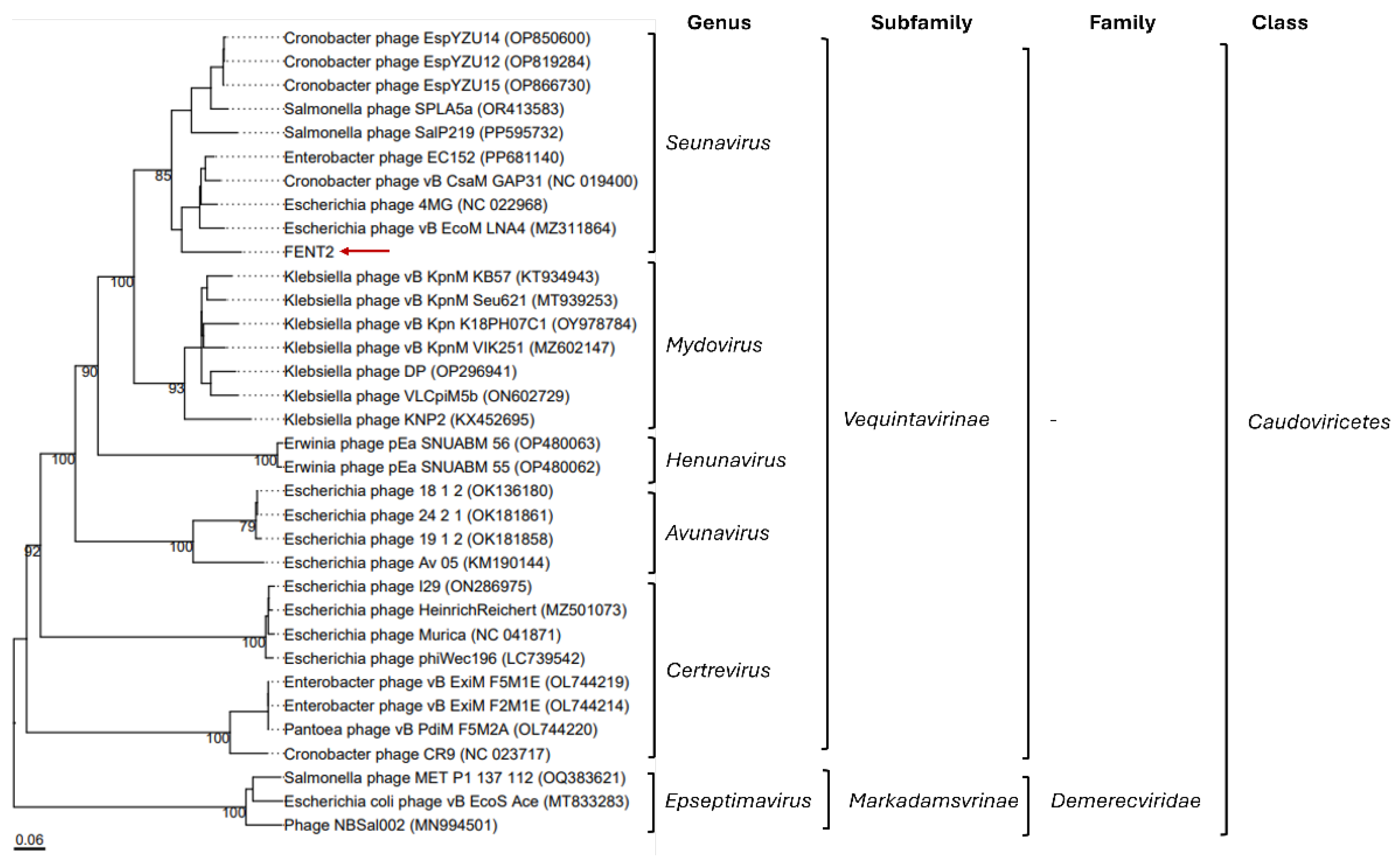

Genomic sequences of FENT2 were found to be closely related to phages of the Seunavirus genus, subfamily Vequintavirinae, class caudoviricetes, which was consistent with the morphology observed.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships of FENT2 with the closest hits from a whole genome BLAST search in NCBI Virus. The numbers above branches are GBDP pseudo-bootstrap support values from 100 replications. The branch lengths of the resulting VICTOR trees are scaled in terms of the respective distance formula used. GenBank accession numbers of reference genomes are provided in brackets.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships of FENT2 with the closest hits from a whole genome BLAST search in NCBI Virus. The numbers above branches are GBDP pseudo-bootstrap support values from 100 replications. The branch lengths of the resulting VICTOR trees are scaled in terms of the respective distance formula used. GenBank accession numbers of reference genomes are provided in brackets.

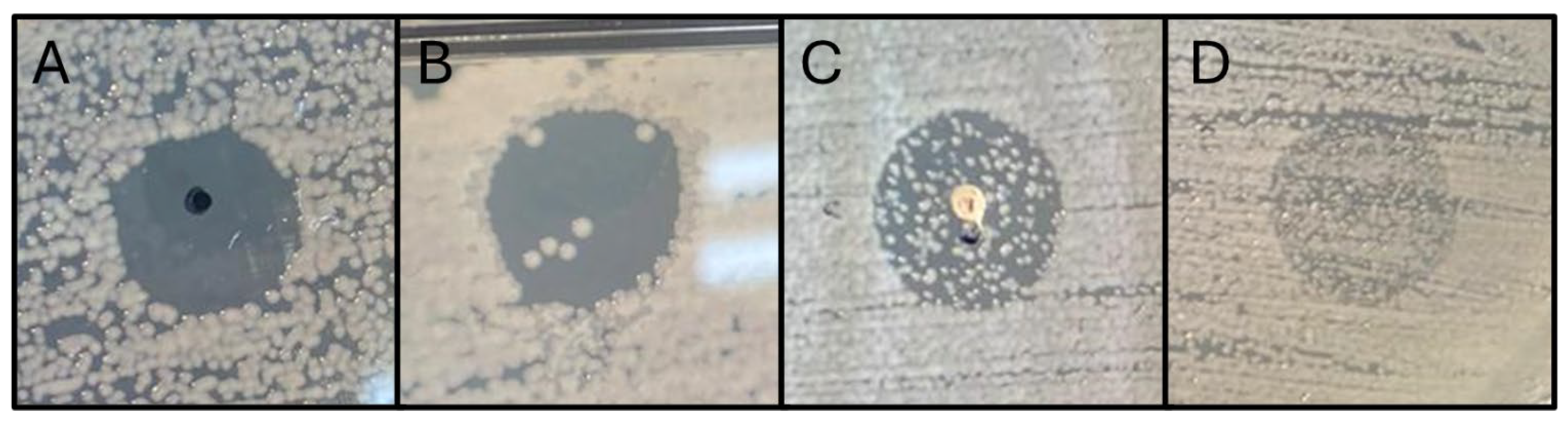

3.2. Host Range Determination

Figure 4 reflects the outcomes obtained from the host range determination through the spot test technique. Results represented in panels A-C were considered positive regarding the phage's infectivity against the tested strain. The detection of turbid spots (panel D) was interpreted as a lack of infective efficacy and specificity of the phage. The occurrence of turbid spots is usually associated with the presence of free endolysins in the phage suspensions, resulting in “

lysis from without” effect without the production of new phage particles, which may cause the partial inhibition observed [

25].

The phage FENT2 exhibited lytic activity against 82.6 % of the tested strains within the ECC. It demonstrated a complete lytic effect only against the host strain E. kobei AG07E, with full spot clearance, while non-host strains showed semi-confluent spots, suggesting lower specificity. Its efficacy varied across species, achieving 100% effectiveness against E. ludwigii and E. mori, but lower effectiveness against E. hormaechei (75%), E. kobei (50%), and E. asburiae (0%). The phage did not exhibit infective activity against any of the strains tested outside the ECC which included isolates of Citrobacter, E. coli, Cronobacter, K. pneumoniae, and K. aerogenes.

3.3. In Vitro Evaluation of FENT2's Potential Against E. kobei AG07E

To evaluate in vitro the bactericidal effect of FENT2 in different pH and NaCl conditions, host strain E. kobei AG07E was challenged with a phage concentration of 10⁵ PFU/mL. The bactericidal effect of the phage on the bacterial population was assessed using the detection time value, which is defined as the time required for the electrical signal to surpass a predefined threshold (3.5%). Increases in detection time in the presence of the phage compared to a growth control in its absence were taken as a measure of the phage's bactericidal effect and, consequently, its viability under the tested conditions.

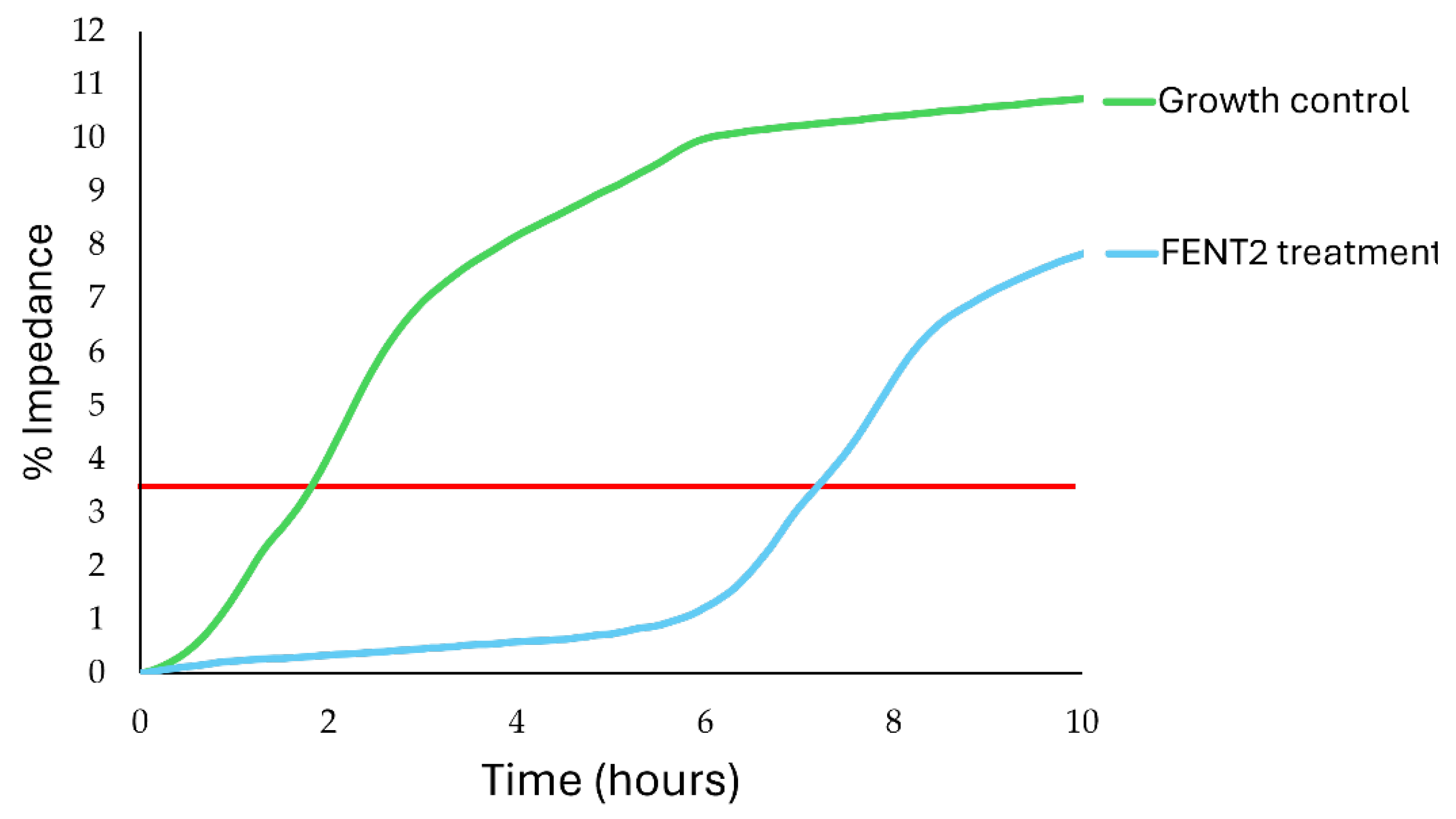

The

in vitro growth inhibition of host strain due to FENT2 at standard medium conditions is displayed in

Figure 5. Exposure of the host strain to the phage significantly extended the bacterial lag phase, increasing the detection time from 1.8 ± 0.04 hours (growth control) to 7.2 ± 0.04 hours (FENT2 treatment).

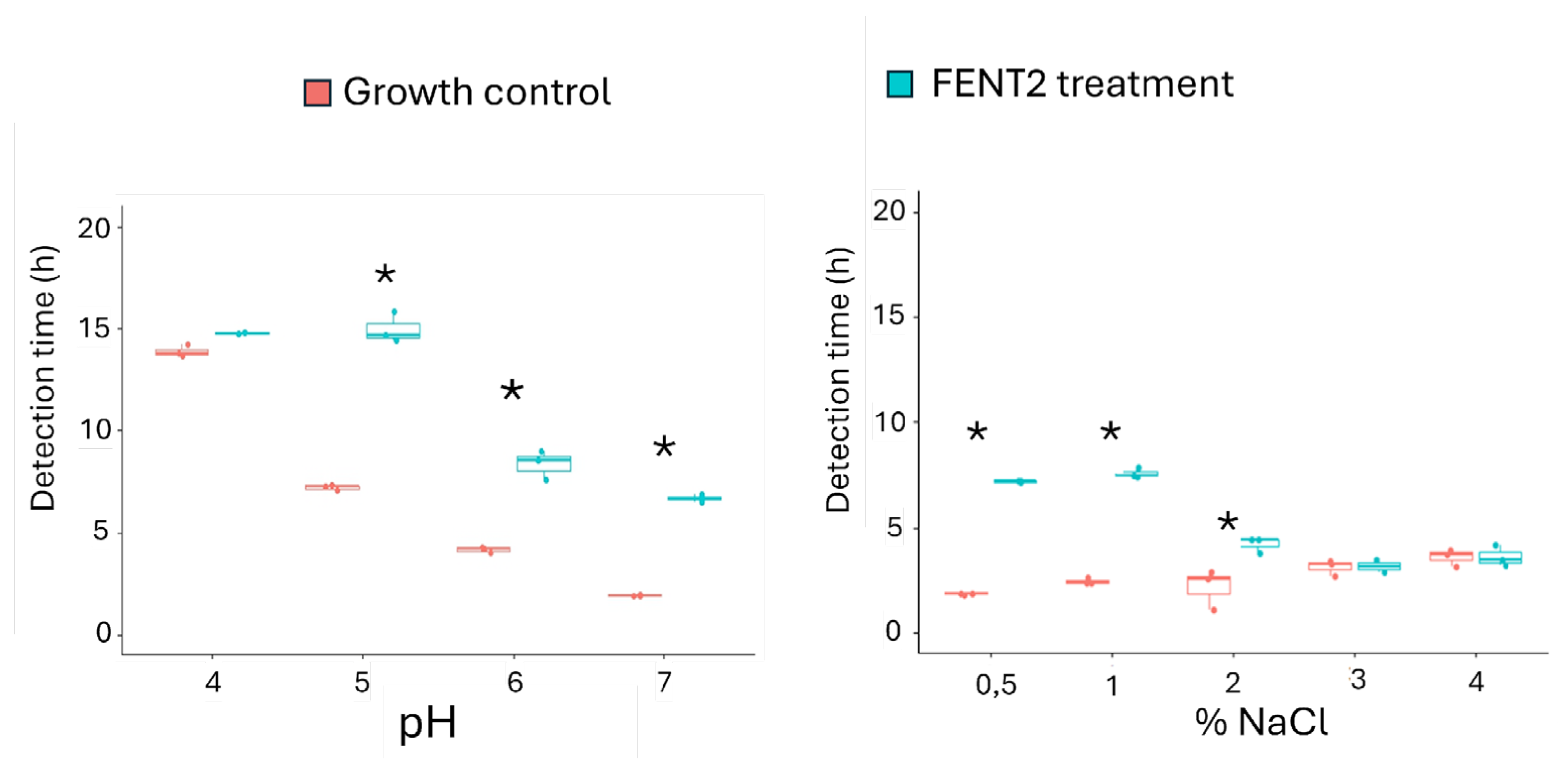

As shown in

Figure 6, FENT2 treatment induced statistically significant increases (

p < 0.05) in detection time compared to the growth control within the pH range of 5–7 and NaCl concentrations of 0.5–2.0%, suggesting a bactericidal effect on the host strain and confirming the viability of the phage under these conditions. Detection time increases were comparable to those observed under standard conditions (pH 7, 0.5% NaCl) at pH 6 and 1% NaCl, with values of 4.8 ± 0,5 hours. At pH 5, the increase was more pronounced, reaching 7.8 ± 0.1 hours. However, at 2% NaCl, the time delay was reduced to 2 ± 0.5 hours, although significant activity was still detected when compared to the growth control (

p < 0.05).

3.4. Measurement of the Bactericidal Effect on a Food Matrix

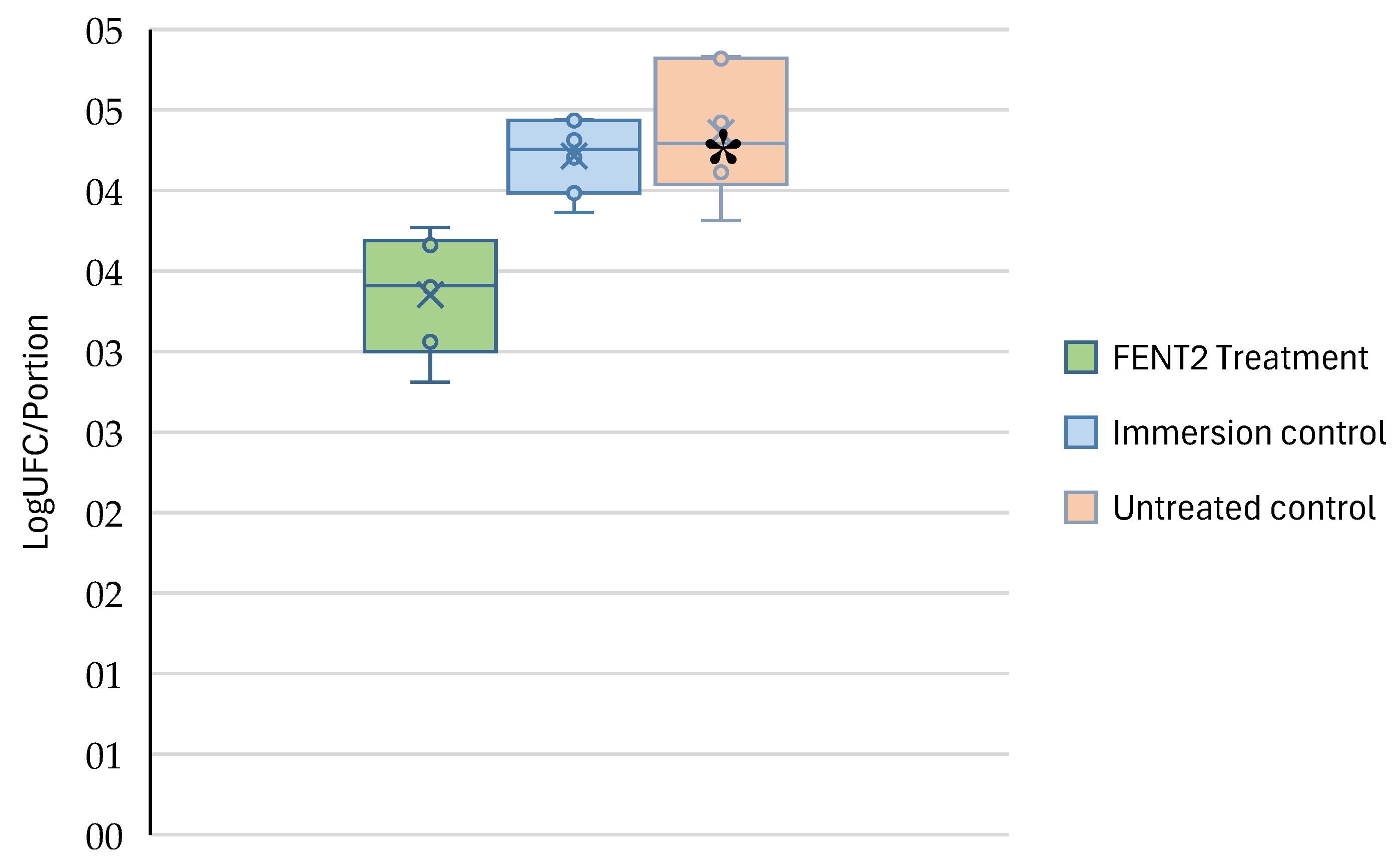

Figure 7 shows the concentration of the

E. kobei AG07E strain inoculated on lettuce leaves after an immersion treatment with FENT2, compared to an immersion treatment without the bacteriophage and a control without immersion treatment.

The immersion treatment of lettuce leaves in the phage suspension was effective in reducing the presence of Enterobacter kobei AG07E on their surface, achieving a significant reduction (p < 0.05) of approximately 1 log.

4. Discussion

The novel FENT2 bacteriophage was isolated from sewage and identified as a member of the

Seunavirus genus (

Vequintavirinae subfamily). Phages from this subfamily are common hosts of enterobacteria, with their specificity described against strains of

E. coli,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Cronobacter sakazakii, and

Enterobacter hormaechei (NCBI Virus). This taxon belongs to the Caudoviricetes order, commonly known as 'tailed phages,' which is characterized by double-stranded DNA genomes and icosahedral capsids [

26].

The characterization of FENT2 revealed significant genomic divergence from previously described phages, with only 70% coverage and 81% identity to the closest match in the NCBI Virus database (Cronobacter phage vB_CsaM_GAP31, NC_019400.1). These findings suggest that this bacteriophage may represent a novel entity within the

Seunavirus genus, based on the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) guidelines for bacteriophage classification [

27]. Therefore, according to ICTV, novel species typically exhibit less than 95% nucleotide identity to known phages, a criterion further supported by the limited 70% genomic coverage observed for FENT2.

E. kobei AG07E was selected as the target strain, with the enrichment and isolation steps including this isolate as the host for the bacteriophage. This strain was isolated from vegetable irrigation water, belonged to the ST56 sequence type, and carried the

mcr-9 gene, whose mobility was experimentally demonstrated [

6]. Strains of

E. kobei ST56 with colistin resistance patterns have also been identified in clinical settings, raising significant concerns about the potential role of this lineage in the dissemination of the

mcr-9 gene [

9]. Its presence in agricultural production environments is particularly alarming due to the potential role of vegetable products as vehicles for the spread of

mcr genes, which is especially worrisome, given the critical status of colistin as a last-resort antibiotic. Developing phage-based strategies specifically targeting this lineage, can therefore be valuable from a public health perspective.

The phage FENT2 exhibited a complete lytic effect against the host strain

E. kobei AG07E, which was used as a reference standard for full efficacy (+++). The phage also demonstrated a broad host range within the ECC, proving effective against 80.95% of the tested strains. Its efficacy varied across species, achieving 100% efficacy against the tested strains of

E. ludwigii and

E. mori. However, its effectiveness was lower against

E. hormaechei (71.4%) showing no infectivity against phylogenetically closely related strains TO40E and TO42E [

6]. The ideal approach in the development of biocontrol strategies based on bacteriophages is to isolate virulent phages with broad host ranges. However, the isolation of highly specific phages presents a significant challenge, as has been reported for other phages targeting the ECC, which often lack efficacy against all strains within the complex. Phages from taxa such as

Tevenvirinae [28] and

Seuratvirus [29] have been shown to exhibit narrow host ranges, affecting a single strain or a small subset of ECC strains. In contrast, other studies have described phages from the

Drexlerviridae family [

20] or

Teetrevirus genus [

30], which demonstrated a broader host range, even extending beyond the ECC, with lytic activity against isolates of

Citrobacter spp.,

Escherichia coli and

Shigella.

To maximize the potential of highly specific phages for biocontrol applications, strategies to broaden the target range could include implementing phage-host adaptation protocols, such as the Appelmans method [

31], or designing phage cocktails targeting multiple ECC strains commonly present in these products. Both phage training and the inclusion of multiple phages in cocktail combinations have additional advantages. It has been reported to increase bactericidal effects of the formulation and to reduce the emergence of phage-resistant bacteria, which is a crucial factor to consider for their long-term use [

32].

Comprehensive analysis of the FENT2 genome demonstrated a lack of lysogenic, virulence and antibiotic-resistance genes highlighting its potential as a biocontrol agent against ECC members. In addition, among the genes classified under the lysis category, the phage encoded two endolysins, the antiholin genes RIIA and RIIB and three Rz-like spanin proteins, but no described holin gene was detected. Based on these results, it can be assumed that the phage follows a lytic life cycle and poses no issues related to its possible role as a vector on transduction events.

To effectively translate biocontrol potential into practical applications, the bacteriophage interactions were studied under simulated food processing stress conditions. FENT2 caused significant increases in the detection time (

p<0.05) within the pH range of 5-7 and NaCl concentrations of 0.5-2.0% that could be associated with phage stability and ability to infect and inhibit host strain growth under these conditions. The maintenance of time delay values observed at pH 6 and 1% NaCl highlights not only the viability, but also the sustained efficacy of the phage under these conditions. Surprisingly, the most significant time delay compared to the growth control was observed at pH 5, which could suggest a synergistic effect between the phage and the acidic environment. This phenomenon is uncommon in literature, where most studies either report the preservation of phage effectiveness or, conversely, a progressive reduction in infectivity as pH decreases due to factors such as capsid destabilization [

33]. This synergistic effect could be associated with an optimized adsorption rate under this condition or even be attributed to the interaction of free endolysins and acids, which has been previously documented [

34]. Tolerance and stability against food-related stresses are particularly important attributes for applications in the food industry. The tolerance of other bacteriophages to food-related stress conditions within ranges similar to those shown by FENT2 has been previously observed for phages such as P100, which is part of the commercial formulation Listex™ [

35]. Moreover, other authors have even reported tolerance to even lower pH values in anti-ECC bacteriophages from the

Drexlerviridae family [

36]. The versatility demonstrated by bacteriophages, such as FENT2, indicates their potential use in products with diverse microbial ecologies and physicochemical characteristics.

The assessment of bacteriophage viability and infectivity under food processing conditions using impedance monitoring technology in the Biotrac (SY-LAB) system is proposed as a particularly useful tool for designing biocontrol strategies in the food industry. The assays can be conducted either using simulated stress conditions, as in our experiment, or by directly employing liquid food matrices such as juices or milk. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using Biotrac technology to evaluate the in vitro efficiency of bacteriophages intended for food biocontrol purposes.

The immersion treatment of the lettuce in the phage suspension was successful in reducing

Enterobacter kobei AG07E on its surface, achieving significant reductions (

p<0.05) of approximately 1 log. Although this reduction is insufficient to completely eliminate the risks associated with ECC contamination in fresh produce, it demonstrates the potential of FENT2 to infect and kill host strain in a real scenario for fresh produce. Direct contact between the phage and host bacteria is essential for infection to take place. Phage-bacteria interactions in food matrices are highly complex and are influenced by multiple factors, including the uniform distribution of the phages, the topography of the vegetable surface, the mobility of the phage, and especially the density of the host bacteria and the infecting phage [

37].

Opportunistic pathogens like ECC are often present in low abundances in foodstuffs.

Enterobacter is commonly found in leafy vegetables, although it is not a predominant genus within their microbiota, with abundance levels ranging from less of 0.1% to 2.6% of the microbial community [

38]. These bacterial loads can, however, still have important public health implications. In our study, lettuce leaves were inoculated with approximately 1300 host cells per cm² and immersed in an SM buffer solution containing a phage concentration of 10

5 PFU/mL. Low bacterial densities pose a significant challenge, potentially compromising both the efficacy and efficiency of phage treatment. This results from the difficulty in establishing contact between the phage and the bacteria, as well as obstacles

in situ auto-amplification of the phage. Therefore, it is essential to account for scenarios of low bacterial density when designing phage-based strategies targeting opportunistic pathogens. Delivery of phages via a fine mist spraying to ensure a uniform and effective distribution and increasing phage concentrations have been pointed out as effective alternatives to address these technical challenges. These strategies can ensure the effectiveness of phages across a broader range of scenarios and potentially achieve higher reductions than those observed in this study [

37].

The development of phages targeting opportunistic pathogens has limited commercial appeal since these pathogens do not frequently cause foodborne illnesses. However, their application could be highly valuable from a “One Health” perspective by limiting the spread of emerging pathogens. Translating these findings from the experimental field to practical application in the food industry could involve combining anti-ECC bacteriophages with other phages effective against traditional foodborne pathogens. Additionally, phages targeting other opportunistic pathogens frequently transmitted through vegetables, such as

Acinetobacter or

Stenotrophomonas [

39,

40]

, could be included in these formulations. The commercial interest of anti-ECC bacteriophages may also arise from the spoilage potential of this complex, as certain ECC species can spoil both fresh vegetables cut vegetables and, more notably, fermented products like pickled cucumbers where ECC has been identified as a major contributor to spoilage due to gas production [

41]. It is important to consider that, in potential applications within the fresh and ready-to-eat vegetable industry, a phage-based biocontrol method would act as an additional hurdle against targeted bacteria, complementing existing physical and chemical treatments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P-C., T.M.L.D., J.A.S and J.M.R-C.; methodology, A.P-C, A.C., and A.G. ; software, A.P-C., A.C. and A.A.; investigation, A.P-C., A.C.;; data curation, A.P-C., A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P-C., A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.P-C., AG., T.M.L.D., J.A.S., and J.M.R.C. .; supervision, A.A., J.A.S. and J.M.R.C.; project administration, J.M.R.C..; funding acquisition, J.A.S. and J.M.R-C All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.